Archive for the '1910s cinema' Category

When John was Jack: Ford’s early westerns rescued

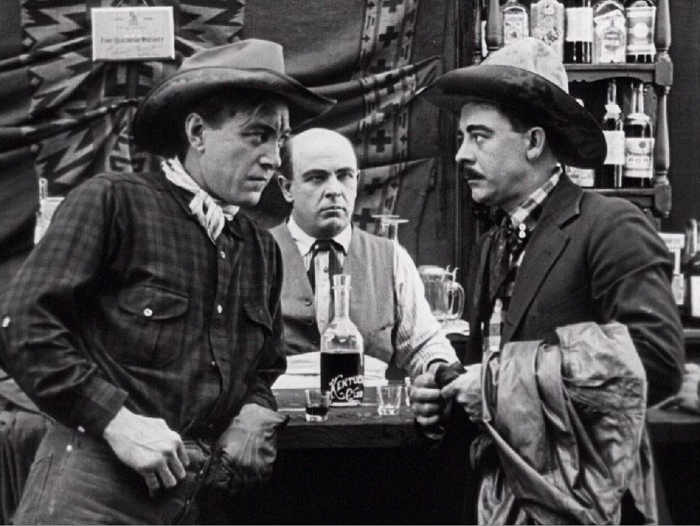

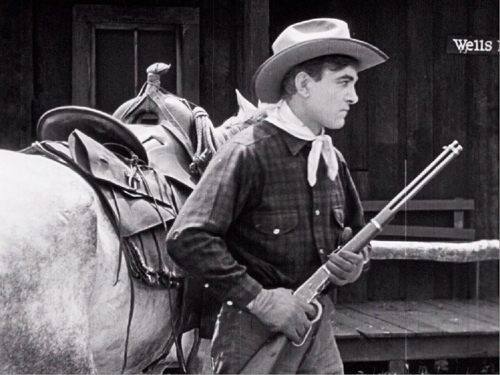

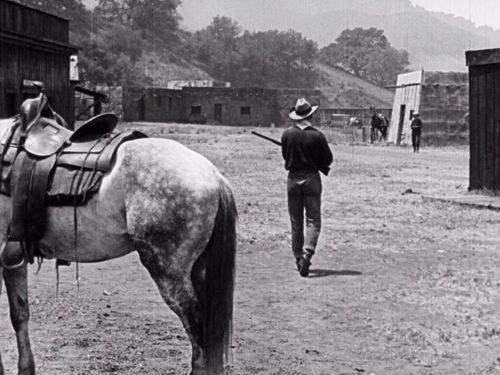

Straight Shooting (1917).

Kristin here–

Recently I received a most welcome message from cinephile extraordinaire Michael Campi, whom David first met at the 1995 Hong Kong Film Festival and with whom we have shared many a meal at subsequent festivals on three continents. His smiling face has shown up often across the history of this blog, most recently here. Michael was alerting me to the existence of a Blu-ray edition of John (aka Jack) Ford’s Hell Bent (1918). Kino Lorber released it on August 25, and as I discovered upon investigation, it had released a Blu-ray of Straight Shooting (1917) on July 14. A third feature, Bucking Broadway (1917) also survives, albeit in somewhat truncated form. (See below.)

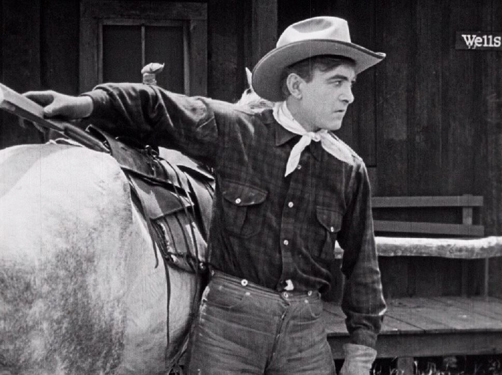

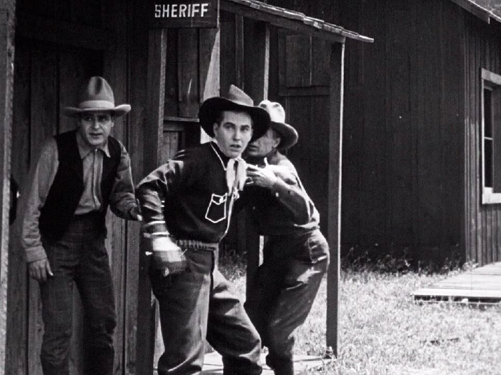

Jack Ford, as he signed his films up to 1923, had made five two-reel westerns in 1917 before his first feature, Straight Shooting, followed by three other features that year. Harry Carey’s character, Cheyenne Harry, was popular, and Universal was clearly happy to have Ford crank out five-reelers starring Carey. (Stories of how Ford supposedly tricked Universal into “letting” him make a feature strike me as having been concocted well after the fact.) Cheyenne Harry was Carey’s main persona, but these features were not a series or serial. Carey is a different Harry each time, winning and marrying different women. When he departed from his good-bad man character, he took a different name, as with upstanding cowboy Buck in Bucking Broadway.

Even across these three films, the plots seem fairly formulaic, but the execution already displays considerable stylistic and technical sophistication. Ford had already mastered the continuity guidelines that had gelled over the previous years. Most of his films were shot in direct or diffused daylight, but he knew how to create an effective chiaroscuro with artificial light when a scene called for it. He often staged in depth to a degree that was unusual in that period. Particularly in Hell Bent he creates flashy scenes to show off his mastery of the cinema.

Both films survived only at the Národní filmovy archiv in the Czech Republic. (Go here for a remarkable list of major international classic films which have survived only because there were unique prints of them in this archive.) That chance survival is very lucky for us. Ford is credited with making 32 films from 1917 to 1919 (fifteen in 1919 alone, though some were shorts). Only three survive in anything close to complete form, and a few brief scraps have come down to us as well. These new releases and an earlier one make all three available in the best prints out there.

Straight Shooting

Straight Shooting is the earliest and arguably the best of the three. Its story is tight and develops continually, without the padding noticeable in Hell Bent and Bucking Broadway. The plot of the ranchers trying to drive out the settlers runs through it consistently and holds it tightly together. Straight Shooting also sets the pattern of making a romance line of action prominent in the plot. In both Straight Shooting and Hell Bent Harry begins as a criminal and reforms when he falls for the virtuous heroine. In Bucking Broadway, another common pattern is used. As a cowhand on a ranch, Harry woos and wins the hand of the rancher’s daughter, only to lose her to a slick visitor from the city who persuades her to elope with him to New York. Naturally he turns out to be a scoundrel, and she needs rescuing to return to the little house Harry has built for his bride.

To some extent, these patterns are taking up conventions of William S. Hart’s films, though Harry is a more easygoing, comic character than the solemn, stalwart heroes Hart tended to play.

Already Ford displays his remarkable mastery of the medium. The famous shoot-out scene is handled with an unusual panache. After Harry comes out of a building and sees Fremont riding toward him, he unsheathes his rifle. A reverse shot shows Fremont dismounting and doing the same.

In the same shot, Fremont moves forward, leading to a tighter reverse shot of Harry, waiting.

A tighter reverse shot of Fremont follows, leading to a repetition of the original framing as Harry moves rightward.

The original framing of Fremont is repeated as he responds by moving leftward. A long-shot in depth (emphasized by the placement of the horse in the foreground, shows the two men in the same space, establishing the distance between the two but also setting up the building on the far right that Fremont will duck behind, leading to a cat-and-mouse game that forms the last part of the shoot-out.

A tighter shot-reserve shot places the two men in irises. Harry moves toward the camera.

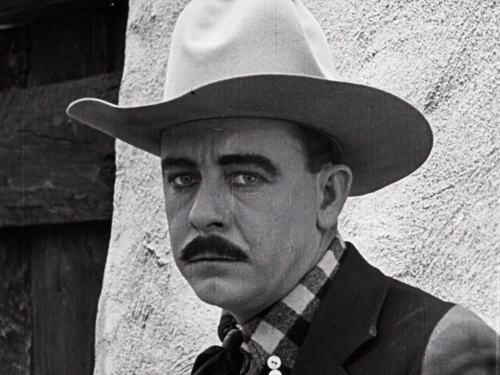

Fremont moves forward as well and comes even closer to the camera than Harry does; the camera also lingers on his face longer than on Harry’s. These close views of Fremont place considerable emphasis on his fearful expression in comparison with Harry’s determination. This fear sets up the moment when Fremont ducks behind the building.

A cutaway to some onlookers ducking into the alley at the rear builds suspense but also shows that the sheriff is too scared to interfere (as he had been in an earlier scene in the bar).

In the repeated depth framing, the two men walk slowly toward each other. More cutaways show frightened townspeople ducking into hiding. Harry and Fremont walk past each other without firing , which adds an unconventional little twist to the scene, and Fremont suddenly hides behind the building.

Although a high point, the shoot-out is not the only indication that Ford was born to make movies.

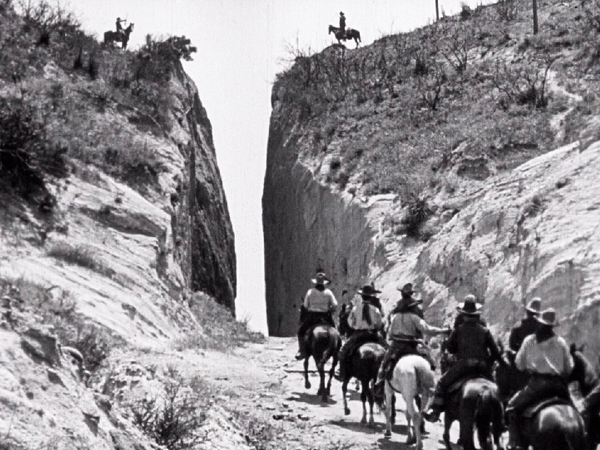

His use of natural locations was distinctive from the start. He may have already been using Beale’s Cut, the narrow passage in the frame at the top of this section, in his short films. (Other filmmakers, such as Keaton, shot there as well. Tag Gallagher’s video essay on the disc runs through a few of them.) This formation appears relatively briefly in Straight Shooting, but Ford used it more extensively in Hell Bent. It may have been the Monument Valley of Ford’s early career.

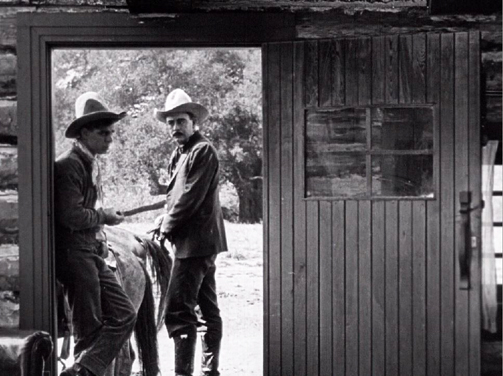

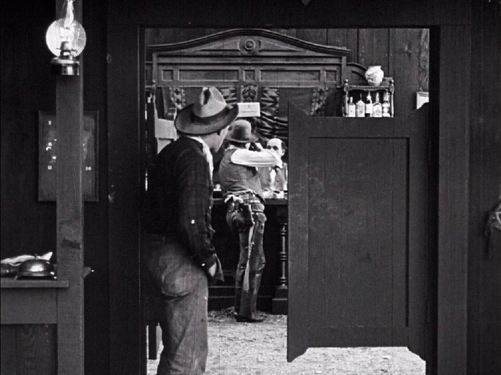

His penchant for doorways has appeared by this early point. On the left, the young cowboy Danny and Fremont pass in the door of the villainous rancher Flint’s house. On the right, the bar doorway is combined with considerable depth as Harry arrives to announce that he is quitting the gang.

Depth is used in natural settings as well. The ranchers’ attack on the farmhouse includes a dramatic composition with horsemen shown in near silhouette against the distant house, visible through a cloud of gunsmoke and dust. At the right, the staging of a meeting in which Flint discusses strategy with his henchmen has the furniture in the foreground, with the placement of the sofa forcing two of the men to face away from the viewer, creating a naturalistic touch. By the way, compare the diffused lighting and set design, with its ceiling beam, with a nighttime scene at the villain’s lair in Hell Bent, below.

Most Ford fans are probably familiar with Straight Shooting, albeit in inferior prints. Before I pass on to the lesser-known Hell Bent, some information about the Kino Lorber version.

According to Tag Gallagher’s essay in the accompanying booklet, the Nederlands Filmmuseum used a copy of the Czech print to create a tinted version. The Museum of Modern Art also made a version from the Czech print; its head title and credits copy the design of Universal intertitles of the period. That print, presumably the one I saw years ago, translated the Czech titles. The Kino Lorber print is a 2016 restoration by Universal, which adopts the MoMA credits but uses title text drawn from an early continuity script of the film. I must agree with Gallagher that the decisions to use those titles and not to tint the print were correct. As the image at the top of this entry shows, the result is a huge improvement on previously available versions.

Apart from this booklet, the supplements also include a brief video essay on Ford’s early career by Gallagher, an audio commentary by Ford scholar Joseph McBride, and a three-minute fragment of Hitchin’ Posts, which is all that is known to survive of Ford’s 1920 film.

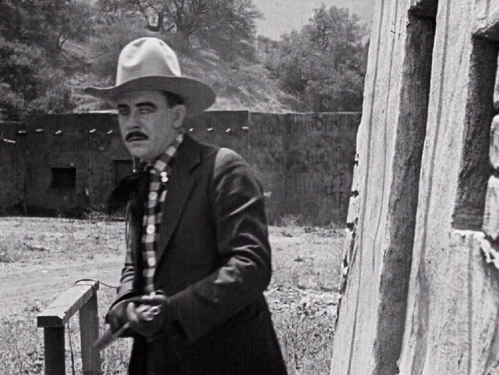

Hell Bent

We first saw Hell Bent when it was screened at “Le Giornate del Cinema Muto” festival in 1988. Although the surviving Czech print was missing over twenty minutes of footage (near the beginning and especially the ending as far as I could tell), it was another impressive revelation of Ford’s very early work. It was also quite worn, more than Straight Shooting, it would seem, since even a comparable restoration by Universal could not quite replicate the visual quality of the Straight Shooting Blu-ray. Still, it is again a big improvement.

The plot of Hell Bent is considerably less well constructed than that of Straight Shooting. Early in the film there is an impressive stagecoach robbery sequence that sets up the criminal gang, led by Beau Ross, that Harry is initially linked to as a sometime hit-man. The robbery in fact fails, as the expected Wells Fargo cash-box has been secretly sent by by wagon taking a different route. Nothing comes of that immediately.

The opening of the robbery scene displays Ford’s expertise in both editing and dramatic cinematography. The scene begins with the gang high on a hill looking off expectantly. A POV long shot reveals a stagecoach passing below.

The group turn and begin to ride off left. There follows an extreme long shot of a winding road with the stage moving up the lower part of the road.

We see the bandits riding rapidly down a steep slope. Finally the stagecoach is seen in the same framing as before, now further along, and moments later the gang appear at the upper right around the bend, galloping to intercept the coach.

After the failure of the robbery, there is little plot development in the first half of the film. There’s a long comic scene as Harry arrives in town and finds all the beds in the local saloon/dance hall occupied. He rides his horse up to the room with a single occupant who has refused to share his bed. Harry demands that he do so, and the two take turns forcing each other to jump from the window until they end up drinking together and becoming chums. (The bar here may well be the same set as that in Straight Shooting redressed. Bars apparently played a large role in Ford’s films, not only in these scenes but also in the production still at the bottom of this entry.) Teaming up with another cowboy gains Harry an ally in later in the action, but their initial encounter is quite drawn out.

As in Straight Shooting, Harry falls in love and reforms. (We witness the process of him contemplating the benefits of a settled domestic life in the close-up at the top of this section.) The second half becomes more goal-driven, with Harry leading the effort to defeat Ross’s gang.

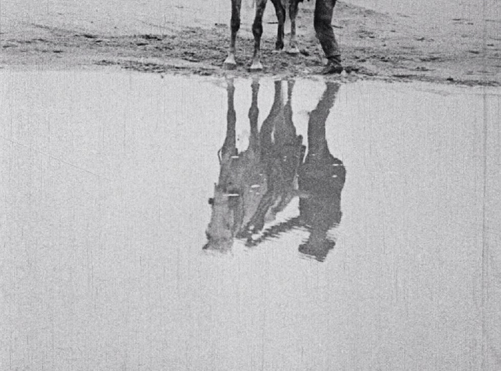

There is no sustained action that is as flashy as the gunfight in Straight Shooting. Still, Ford seems even more determined to flaunt his prowess as a director. He gives us our first view of our hero as a reflection in a pond. He shows horsemen as shadows in a shot that prefigures a similar device in the Indian attack in The Iron Horse (1924).

The beginning of the climactic attack on the stagecoach begins with Ross signaling to his men on distant hilltops to converge. This is handled with excellent graphic matches of Ross, his henchman, and back to Ross. A short time before, as the gang rides out of town, they are filmed so that the horses gallop toward and jump over the camera.

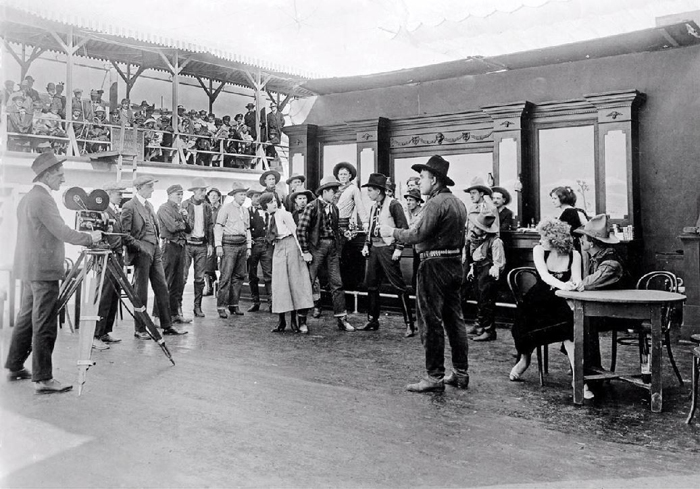

Most of the interiors were shot on stages at Universal with muslin diffusers draped overhead to create an even, overall light. The image at the bottom of today’s entry shows this setup for another Harry Carey film by Ford. Incidentally, it also shows an audience watching the filming. Ford again creates chiaroscuro, this time more elaborately, for Ross’s house. There is a ceiling of log beams with something over them to block out the light. The distant room is lit more brightly than the foreground one, which is lit only by a fire (presumably simulated with one or more arcs) in the left foreground. For some of the more static exteriors, Ford has the camera shooting obliquely toward the sun, creating considerable modeling on the characters.

Although, as I said, there is no big final scene, there is a jaw-dropping shot during the gang’s pursuit of the stagecoach in the climactic sequence that demonstrates how thoroughly Ford had already grasped the powers of mise-en-scene and the camera. Although the scenery looks quite different from that of the high-angle extreme-long shot of the winding road earlier, I’m fairly sure that this is the same road, shot from a different vantage point, more or less where the gang had been waiting in the earlier scene. If not, it is certainly somewhere similar nearby, with a hairpin road on the side of a mountain.

The stage initially comes forward from the distance at the upper left (the area where the gang had come from when they appeared in the final shot of the sequence reproduced above). As the horses round the curve and race down toward the right, the coach breaks lose and begins to fall over the edge.

The camera tilts to follow it, but after it falls out of sight at the bottom, the tilting movement pauses, not continuing with it until it crashes offscreen.

After this pause, the tilt resumes, revealing the crushed coach at the bottom of the cliff. The reason for the pause in the tilt becomes apparent: offscreen the horses have rounded a bend and now come unexpectedly racing through the shot, past the coach. The camera had paused, waiting for the timing to be just right to catch them. I believe that someone who could figure out the logistics of that action and that camera movement had a pretty good feeling for cinema from very early on.

In addition to this dramatic mountain road, Ford uses Beale’s Cut in multiple scenes, making it the location of the gang’s hide-out.

Hell Bent was also restored by Universal from the Czech print. There’s no booklet with this one, but Gallagher again provides a second, different brief video essay. The other supplements consist of another commentary by Joseph McBride, as well as a 1970 interview he did with Ford.

Bucking Broadway

Watching the two Kino Lorber releases, I was reminded that a third Ford feature of this era also survives–though, like Hell Bent, it is missing footage, probably about the same amount, given the running lengths. Bucking Broadway was one of eight features by Ford released in 1918. His ninth feature, it also stars Harry Carey, this time as Buck. The plot is thin, with Harry as a cowhand who falls for the rancher’s daughter and is given his blessing to marry her. She elopes with a man from the city, who does intend to marry her but turns out to be a drunkard and lout. Harry and his cowboy friends come to New York and rescue her.

Even more than Hell Bent, the film seems like a two-reeler stretched to five. Harry’s engagement party involves a comically maudlin scene the cowboys picking out “Home, Sweet Home” on a piano and bursting into tears as they sing along. The final rescue and fight are expanded to create some comedy about cowboys riding their horses through the city, and the final brawl seems barely staged and way too long.

Nevertheless, there are flashes of Ford’s skill at intervals, with his door motif recurring as a site for the rancher to mourn his daughter’s departure and a scene by a fireplace using the stark low-key lighting popularized by The Cheat three years before.

There are plenty of depth shots like this one, as the cowboy in the foreground calls the others to gather and we see three of them in the distance. See the top of this section for an unusually flashy depth shot as two friends of Buck watch the villain getting drunk in the close foreground.

There are none of the virtuoso treatments of editing, landscape, and camera movement that characterize the other two films of this era, but any Ford completist will want it. After all, it comes as a supplement to The Criterion Collection’s DVD and Blu-ray releases of Stagecoach. It includes a charming musical accompaniment by Donald Sosin, whose piano and violin playing (often simultaneously!) has enlivened many an Il Cinema Ritrovato screening.

The photograph below was borrowed from Tag Gallagher’s video-essay supplement on the Hell Bent disc.

Beale’s Cut is not a natural formation. As the name suggests, it is a man-made passageway created in the 1850s and 1860s as a convenient route into and out of nearby Santa Clarita (just north of the San Fernando Valley). It still exists, though comments on Google Maps suggest that, being located on land belonging to an oil finery, it is fenced off, partially collapsed, and full of trash. For a brief account of its sad decline, see here. There are many historical photos of it online.

Shooting an unidentified Ford-Carey movie at Universal City’s stages.

Hollywood starts here, or hereabouts

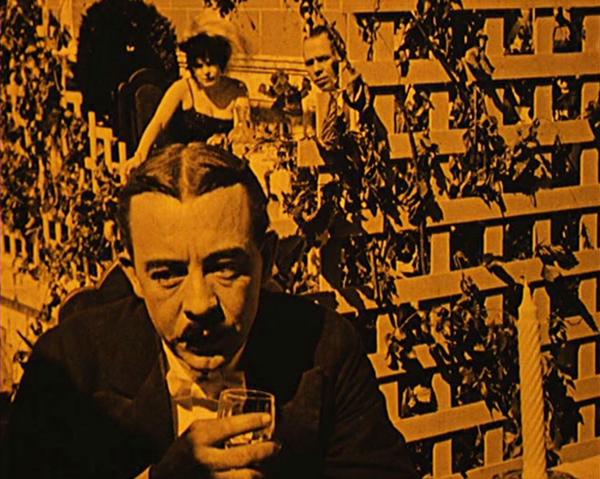

The Woman in White (1917). Toning by DB.

DB here:

Do you know Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White? I hope so.

The traps set by this novel of mystery and suspense–a prototype of what was called “sensation fiction”–are still ensnaring audiences. Serialized in 1859-1860, it became one of the best-selling books of the nineteenth century. Merchandisers pounced on it, offering Woman in White cloaks, bonnets, perfumes, and songs. Stage and film adaptations followed. The Brits, always eager to mine classics, have created no fewer than three TV versions (1982, 1997, and 2018). There’s a pretty good Warners “nervous A” picture from 1948, with Sydney Greenstreet as the deadly, jovial Count Fosco.

The 1917 version from the Thanhouser studio is, lucky us, currently streaming on Vimeo for free. It’s also available on DVD, as part of the excellent series of Thanhouser films. The print is a 1920 re-release, but nothing significant seems missing or altered.

Apart from its entertainment value, the Thanhouser Woman in White can teach us a lot about film history. Why? Because it sums up very forcefully what American narrative cinema could do in that crucial year 1917. Forget your Griffith, leave aside (regretfully, just a moment) your Webers and Harts and Fords and Fairbankses. The mostly unheralded team of screenwriter Lloyd Lonergan and director Ernest C. Warde have given us a concise demonstration of the power harbored by classical Hollywood from the start. The storytelling tools assembled in that era remain with us still.

Women in peril

The novel’s plot is a tale of–well, plots. Counterplots too.

Collins’ book is hugely complicated, swirling together secrets, hidden identities, abduction, impersonations, illegitimate birth, bigamy, insanity, forged records, fake tombstones, assorted hugger-mugger, and timetables that even the author had trouble keeping straight. The intricacy is magnified by Collins’ decision to adopt a “casebook” structure, in which participants and onlookers write up their accounts of what they witnessed. Each piece of testimony is restricted wholly to one character’s viewpoint, and the writers are forbidden to fill in material they learned later. “As the Judge might once have heard it, so the Reader shall hear it now.” This stricture isn’t fully observed, though, because at least one witness sneaks looks at what counterparts have written.

The book’s key image is, of course, the apparition that greets Walter Hartright on the road one sultry night.

There, in the middle of the broad, bright high-road–there, as if it had that moment sprung out of the earth or dropped from the heaven–stood the figure of a solitary Woman, dressed from head to foot in white garments; her face bent in grave inquiry on mine, her hand pointing to the dark cloud over London as I faced her.

Recovering his senses (“It was like a dream”), Hartright listens to her gap-filled story and helps her find a cab. But soon he sees two bravos halt their carriage and hail a policeman. They ask: Has he seen a woman in white? No. Why does it matter? What has she done?

“Done! She has escaped from my Asylum. Don’t forget: a woman in white. Drive on.”

The first installment ends here, and the adolescent window opens a little wider.

The main plot centers on Laura Fairlie and her half-sister Marian. Hartright is engaged as Laura’s drawing teacher and they fall in love. But Laura’s father has promised her to Sir Perceval Glyde, an apparently upright aristo. (Collins was opposed to marriage as an institution. His class hatred comes out as well, though perhaps not as scathingly as it does in his other masterpiece, The Moonstone.) Once the marriage takes place, Glyde introduces into the household Count Fosco, a suave “doctor” with the habit of letting his pet mice scamper around his waistcoat. It doesn’t take long for Marian to realize that Glyde has a Secret, and she must turn detective to protect Laura from him.

Without pressing into spoilers, you can already tell that this lays down a template for the sort of story Hollywood would later love to tell. The Woman in White is a prototype for the woman-in-peril plot that we’ll find in Suspicion (1941), Shadow of a Doubt (1943), The Spiral Staircase (1946), The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947), Sleep My Love (1948), and many 1940s classics. These in turn rely on literary works in Collins’ wake by Mary Roberts Rinehart, Mignon Eberhart, and other women authors who updated Gothic and sensation-fiction conventions for the twentieth century.

Lloyd Lonergan was said to have suggested reducing the eight-reel cut of The Woman in White to only six. It’s indeed a tightly coiled presentation of Collins’ sprawling plot. Swathes of backstory are dropped. Instead of Collins’ multiple narrators we get an omniscient narration that shifts freely across various intrigues. Fairly quickly we learn that Glyde and Dr. Cumeo (the Fosco of the novel) are scheming to switch Laura with her lookalike Anne, the woman in white. We also realize that Marian, as an obstacle to the plan, is in mortal danger. Thanks to crosscutting, we’re aware of several lines of action unfolding at once, and in a film full of spying and eavesdropping, compositions tell us who’s snooping on whom.

Still, some revelations are saved for the end, notably one that looks forward to the flashback-heavy 1940s. When Laura and Marian discover Glyde’s secret, their informant gives them the crucial information in a flashback, which precipitates a fiery climax. The flashback device was previewed when Marian, recovering from her collapse, recalled the plans she heard on the patio between Glyde and Cumeo; a nearly Surrealist dissolve superimposes that earlier scene.

In preferring to give us a lot of information, favoring suspense over surprise, this Woman in White is typical of Hollywood scriptwriting of the classical years. In particular, the film employs strategies later elaborated by Hitchcock (discussed here and here and here). One scene in particular displays the Hitchcock touch, years before Sir Alfred took up filmmaking. Even more specifically, let’s note that the basic situation looks forward to Notorious: a woman imprisoned by her husband and a confederate is slowly softened up for disposal.

Choreography, cutting, and showing us the door

Anyone who has viewed films with critical attention must be aware that in a film we are constantly, and without knowing it, being directed what to look at. In a stage play you may be looking at one moment at the actor who is speaking; at another moment watching the face of the person addressed, or observing the behaviour of other characters on the stage. If you go repeatedly to the same play, you may choose to look at different actors in a different order, for you certainly cannot observe everybody and everything simultaneously. But in a film, the lens of the camera is constantly telling you wha to look at–it may be a close-up of the actor’s hand, by the movement of which he betrays the emotion not visible in his face.

T. S. Eliot, 1951

The 1910s were an exciting era in cinema because, as I try to show in this video lecture, the foundations of “our cinema” were laid then. The film business, movie culture, and mass audiences settled into patterns that would hold for over a hundred years.

Just as important, the forms and styles of film craft were put in place. Among those changes was a transition from a style that relied on performance and staging to an approach more reliant on editing, on breaking scenes into many shots. The dominance of editing as a principle of guiding attention is evident from the Eliot quotation; he can’t conceive that staging, lighting, and other “theatrical” techniques could steer us to the important parts of the action.

The earlier, “tableau” approach to scenes was perfectly capable of funneling attention too, but editing had many advantages, both economic and aesthetic. By 1917, as Kristin and Janet Staiger and I argued in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, the editing-based approach had coalesced into the dominant style. The Woman in White is a nifty illustration of what an ordinary film from that year could accomplish with cutting–while still retaining vestiges of the tableau style.

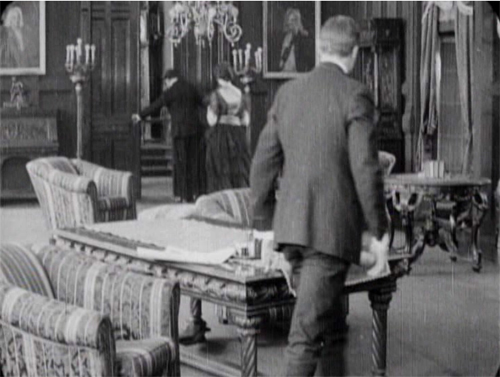

A simple example of the tableau technique comes when Sir Perceval Glyde calls on Laura and Marian. He has just kissed Laura’s unwilling hand, and Marian comes up from the rear of the shot to him. As she moves forward, Laura shifts aside slightly to clear our view of the others. This choreography doesn’t seem stilted because it expresses Laura’s withdrawal from her fiancé.

This is an example of the Cross, the staging technique that coordinates actors’ switching positions in the frame. Marian moves from frame left to frame right as Laura shifts to the left.

The tableau approach often plays between a lateral arrangement of characters in the foreground and a more diagonal array of figures packed into depth. As the shot unfolds, Marian is given a beat to take notice of Laura’s reaction as Glyde retreats to the background. She conveniently blocks his departure as she looks warily back at him.

But Glyde steps back into visibility in the distance as he says goodbye, with the women turning away from us so that we’re sure to concentrate on him. Then as the women turn back to react, he can be glimpsed leaving on the far right.

Doorways in the distance, characters advancing to and retreating from the camera, figures spreading themselves out horizontally but also blocking our view of things behind them, only to reveal them at the right moment–these tactics of the tableau became supple and subtle during the late 1900s and throughout the 1910s.

Eliot need not have worried that our attention would stray. Centering, frontality, movement vs. stasis, lighting, gesture, and other creative choices push us to notice the important elements of the scene. And these factors aren’t equivalent to what we see on the theatre stage; the optical properties of the camera lens create a very different playing space. (See here and here.)

Tableau staging hung on in editing-driven cinema, but it tended to be relegated to the role of an establishing shot. The first part of this scene consists of another tableau setup broken by a cut when the slimy Glyde kisses Laura’s hand.

Here the closer view underscores his gesture while isolating Laura’s concern.

The coordination of staging and cutting is nicely shown when Walter Hartright, having resigned from his post as Laura’s teacher, accidentallly encounters Glyde at the train station. Glyde is coming to arrange his marriage to Laura, so the plot needs to establish the friction between the two men early on. As they confront each other, Glyde’s assistant loads his luggage into the cab in the background.

The first phase of the scene choreographs the men’s encounter through the Cross.

Then close views underscore the significance of the encounter.

Cut back to a two-shot that reorients us.

The fact that it’s not the same framing as we saw at the start indicates the reliance of the style on editing; even the full view is re-calibrated in light of changing shot scales. And during the shot of Walter, Glyde’s position has changed from his orientation in his medium shot. That’s the sort of flexibility editing gives you. The new arrangement heightens the clash of the two men. (Typical of the 1910s emphasis on depth, Glyde’s assistant and the driver continue to load the cab in the background.)

Glyde’s enlarged hand kiss and the inserts of the two men in the station scene exemplify the axial cut. This is a cut made along the lens axis of the camera–a straightforward enlargement of a chunk of space. It’s very common in 1910s cinema, and it’s still around, though it’s not as common as it was. Editors came to prefer analytical cuts that were more angular, yielding less the sense of a sudden enlargement. Sometimes you’ll see claims that cut-ins or cut-backs should shift the angle by 30 degrees. Yet Kurosawa and Eisenstein made powerful use of the axial cut, and it’s sometimes used as a self-conscious device. During the 1910s, some directors began using the over-the-shoulder (OTS) framing as a way to assure distinct angle changes.

The cut to Glyde’s creepy kiss is also a match on action, smoothly linking Glyde’s gesture across the shot change. This too emerged in the 1910s and became a mainstay of classic editing technique, to this day. (See my earlier post on Watchmen for contemporary examples.)

The Woman in White has several adroit matches on action, which shows that the learning curve among directors was more or less complete by 1917. When Walter first encounters the mysterious woman on the road, his striking a match is carried across a cut, with the second shot introducing her coming toward in him n the distance.

One of the most common editing devices of classical continuity is the eyeline match, and filmmakers were mastering this from quite early on. By 1917, it was part of every director’s tool kit. We can see how it works together with the other techniques in a fine, smooth scene that leads up to a crucial turning point in the action. Glyde and Dr. Cuneo are in the library, where Marian is uneasily reading a novel. Cuneo moseys over behind her, softly threatening, and an axial cut matching his movement lets us know she notices.

Another match on action brings her off the sofa. Love those delicately splayed fingers.

As she starts to leave, we get the Cross, as Glyde rises from his armchair and goes frame right. We now get the start of a major piece of business: Cuneo’s byplay with the sliding doors.

Securing their privacy, Cuneo prepares to consult with Glyde about their skulduggery. But a match on action, carried by a powerful axial cut–a huge enlargement from the extreme long shot setup–alerts us. He’s listening.

Another match on action as he busies himself with the door. A new diagonal composition prepares us for a shot of Glyde to come shortly. And yet again Cuneo is matched as he opens the door.

The payoff: Cuneo has detected Marian outside listening. She bluffs, saying she left her novel behind.

Now comes the shot that was prepared for by the over-the-shoulder long shot above. It’s not an axial cut, but a genuine reverse angle on Glyde, who’s suspicious about Marian’s return.

This is a killer shot because the camera can assume a drastically new position. It has put us in between the characters in a way we weren’t in the station scene. In effect, there’s an axis of action running from Glyde to the doctor and Marian at the door. The reverse angle is a one-off technique at this moment, but the possibility of penetrating the dramatic space in this way will be central to continuity cutting.

Now tableau principles can kick in. Marian comes forward and gets the book while Cuneo watches warily in the background.

In the course of the shot, Marian leaves, and this time, thanks to deep staging, we and the plotters can see she’s not eavesdropping. As she goes upstairs, Cuneo closes the door and the men can settle down to scheming.

Five matches on action, a striking eyeline match, restrained but pointed performances, and a cogent staging of the action have yielded a vigorous, engaging scene. By 1917, classical screen storytelling is well established in even a run-of-the-mill production. But there’s nothing run-of-the-mill about the suspense that follows this trim tension-builder.

1910s noir rides again

The Woman in White illustrates a lot of other 1910s innovations in pictorial storytelling. There are, for instance, some concise special effects, as when on Laura’s wedding day she sees herself and Walter in her vanity mirror.

There are also dramatic lighting effects, motivated by firelight, single lamps, and eventually lightning flashes.

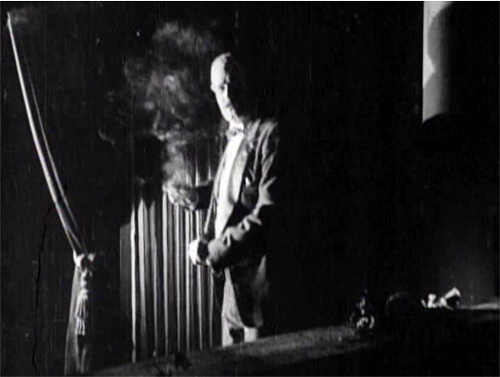

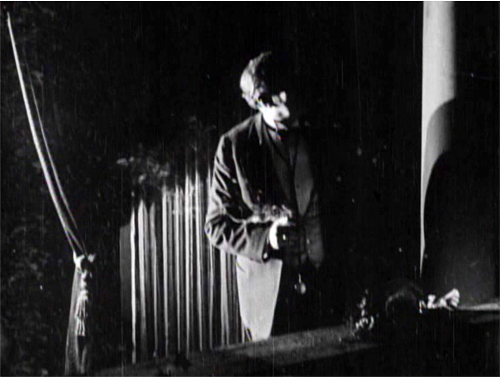

But more audacious is a sustained experiment in “1910s noir.” At that period filmmakers began associating crime and mystery with shadows and stark lighting. (See this entry.) When Glyde and Dr. Cuneo adjourn to the terrace to discuss their scheme, we get a remarkable instance. I won’t indulge my impulse to shower you with images, but I’ll try to suggest why you should try to see the sequence for yourself.

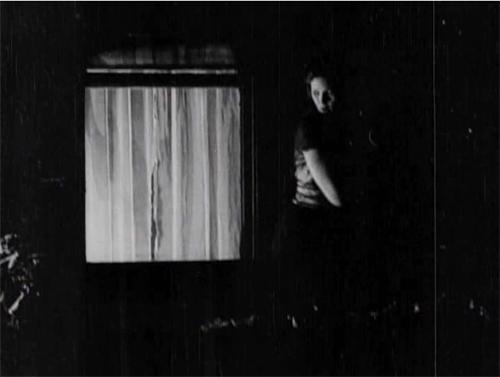

While the men smoke and talk outside, Marian has seen to the sleeping Laura before going to her own bedroom. (A sign of the film’s tidiness is the way it establishes the main characters’ rooms in the upstairs hallway. This geography becomes important when Glyde and Cuneo exchange Anne for Laura.) Opening her window, Marian hears the men outside and ventures onto the balcony above them. This yields a remarkable extreme long shot: She eavesdrops from above.

It’s a difficult shot by later standards. The main action is wildly decentered, set off on the right. But at least this framing has the virtue of preparing us for the later development of the scene, which will involve Marian sneaking along the balcony back to her room, where the light comes from.

The vertical layout of the action is immediately clarified by two closer shots, a lovely chiaroscuro image of the men and the other of Marian listening.

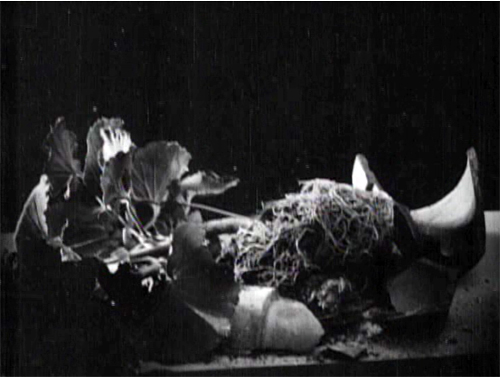

She hears just enough to suggest the men’s scheme before complications ensue. Glyde goes inside and upstairs, where he might discover her. Meanwhile, a rainstorm starts, and Marian dislodges a potted plant. Cuneo turns, in a new setup that emphasizes the railing in the right foreground, so that we can see the fallen plant. The shattered pot is given a close-up more or less from Cuneo’s viewpoint. His reaction supplies a moment of suspicion.

Marian, now drenched by rain, seems trapped between her two adversaries. Will one or both discover her?

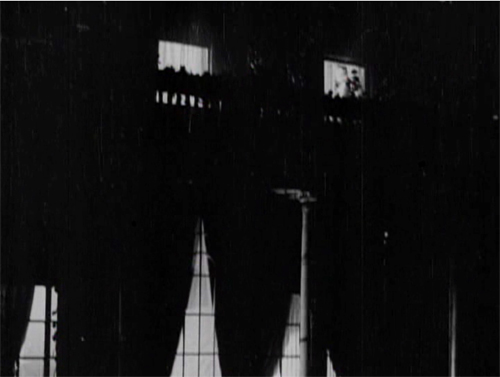

Glyde who has gone to Laura’s window and is looking around outside. We’re reoriented through a new master shot of the house, a framing that varies from the original setup. The shot shows both Laura’s and Marian’s windows lit. There follows a dark passage in which Marian creeps up to Laura’s window. That action takes place in the shot I’ve put up above.

An extra twist: Glyde looks out, but then pulls the shade. Little things mean a lot. A soaked Marian manages to crawl back through her window.

Apart from its virtuosity in handling cutting and lighting, the sequence is crucial for the plot. Marian collapses from her exposure to the storm, and her illness provides a pretext for Cuneo to isolate her while he and Glyde proceed with their plan.

I invoke Hitchcock because this long passage of suspense depends on our knowing all the relevant factors in the situation, and the possibility of a giveaway–the smashed plant–drives up the tension. What I’m really saying, I guess, is that Hitchcock expanded and deepened story mechanics that were already in place in the silent era. Apart from refining them, he managed to brand them as his own.

No film from 1917 or thereabouts is faultless in executing the new editing-based style. The Woman in White has its share of mismatches. Then again, so do movies from the 1920s to the present. (Don’t get me started on the mismatched cuts in The Irishman, 2019.) The crucial point is that the system of Hollywood storytelling and style is in place, and not in a crude form. Talk all you want about post-classical cinema, chaos cinema, post-cinema–whatever. The variations we detect today arise against a background of stable norms that remain a lingua franca of world filmmaking, and they’re headed well into their next century.

Thanks to Ned Thanhouser for years of faithful service to the studio’s legacy. Now is an ideal time to visit his site for background on this remarkable company and the efforts to preserve its output. A staggering 132 Thanouser films are available for streaming on Ned’s Vimeo channel.

To find out more about what preceded this crystallization of techniques, see Charlie Keil’s Early American Cinema in Transition: Story, Style, and Filmmaking 1907-1913 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2002).

An excellent survey of Collins’ place in the history of dossier novels is A. B. Emrys, Wilkie Collins, Vera Caspary and the Evolution of the Casebook Novel (McFarland, 2011). Her treatment of Caspary and Laura, both favorites of this blog, is just as valuable. My quotation from T. S. Eliot comes from “Poetry and Film: Mr. T. S. Eliot’s Views,” in The Complete Prose of T. S. Eliot: The Critical Edition, vol. 4: A European Society, 1947-1953, ed. Iman Javadi and Ronald Schuchard (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018), 581.

For lots more on 1910s storytelling, see the categories 1910s Cinema and Tableau Staging. Flashbacks, the woman-in-peril plot, and other conventions that coalesce in the 1940s are discussed in my Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

The Woman in White (1917). Toning by DB.

TRAPPED: Low-budget flash is good for you

Trapped (1949).

DB here:

Films of the 1940s sported many vivid titles, from Double Indemnity to The Best Years of Our Lives. But a lot of them really didn’t try too hard. We have Dangerous Lady, Shock!, Men on Her Mind, Bad Sister, Lust for Gold, and Criminal Lawyer. Even worse are Crack-Up, Manhandled, Temptation, Nightmare, Impact, Homicide, and even, the purest of all, Conflict.

Fortunately the lack of imagination didn’t always extend to story and style. In the Forties, even minor genre films could get flashy, displaying weird plot turns and wild visuals. Nowhere was this truer than in films centered on crime and mystery.

Granted, this material always encouraged some unorthodox techniques. (We can find examples going back to the 1910s.) Still, whatever you think “noir” was, it encouraged filmmakers to push even further. A 1930s B would have been unlikely to be as bodacious as a moment in Detour (1945), when a single forward tracking shot lets the lights lower and makes a coffee mug as big as a bucket.

For such reasons we should be grateful to the Film Noir Foundation, to the UCLA Film and Television Archive, and to Flicker Alley for bringing us Trapped (1949). The generic title had been used by four earlier films, and it could refer to several of the characters, but the results onscreen are far less banal. I hadn’t known the film, but if I had I might have wormed it into Reinventing Hollywood for the wrinkles it adds to the government-agent semidocumentary.

Crime high and low

Product placement for studio Hollywood’s favorite brand.

Trapped was produced by Brian Foy and distributed by Eagle-Lion, the same company that gave us the bizarre Repeat Performance (1947) and some of Anthony Mann’s best Forties items. According to the disc’s informative, pleasantly sensationalistic booklet, the project was hitching a ride on the success of Mann’s T-Men (1947). The Treasury Department approved of the project, and the film includes lots of fascinating shot-on-the-street scenes of LA. Although director Richard Fleischer doesn’t mention the film in his autobiography Just Tell Me When to Cry, he should have been proud of it. (He does mention Clay Pigeon, though, a film I talk about in another entry.)

A stern voice-over launches a quasi-documentary montage of the rise of counterfeiting after the war. Tris Stewart is serving time, but bills with his signature have resurfaced. Agreeing to act as a mole, he’s allowed to bust out of prison, but soon he eludes his federal handlers. He hooks up with his old girlfriend Meg and discovers that his precious plates are in the hands of an old adversary, Jack Sylvester. The bulk of the plot follows Tris’s effort to fund a last big job before fleeing to Mexico with Meg. In the course of it, he joins up with John Downey, a down-at-heel gambler.

The viewpoint shifts freely among the characters, so we always know more than any one of them. We know that the Feds have wired Meg’s apartment for sound. We learn that Downey is actually a government agent working to trap both Tris and Sylvester. And we see Tris eventually learn Downey’s identity decide to double-cross him.

Meg has a pivotal role in precipitating the climax. She’s naturally punished for hanging out with the wrong guy. I could apply my quatrain on Hollywood Stories:

The plot only works

If the men are all jerks;

But at the end of the game,

It’s the woman to blame.

Lloyd Bridges plays the sort of natty, grinning sociopath whom he would make memorable in The Sound of Fury (1951, aka Come and Get Me!). The dry John Hoyt is needed to carry the last stretch of the film, which he does with sangfroid, but Tris exits the plot a little sooner than we’d probably like. Eddie Muller suggests that Tris was intended to be in the climax but production contingencies put Sylvester into it.

To compensate, the wrapup becomes one of those dazzling Forties climaxes played out on an overwhelming location. Like the gasworks in This Gun for Hire (1942), the field of storage tanks in White Heat (1948), and the Fort Point Compound of The Man Who Cheated Himself (1950), here a vast trolley-car barn provides spectacular compositions and lighting effects.

Noir really did bring out the best in creative personnel. Guy Roe, a camera operator and assistant since the 1930s, had moved up to Director of Photography for Sirk (A Scandal in Paris, 1946), Mann (Railroaded!, 1947), another punchy Eagle-Lion effort, and Boetticher (Behind Locked Doors, 1948), so he was ready to give this effort flamboyant touches, some overt and some more subtle.

We tend to think of crane shots as aiming for surveying vistas outdoors. By the 1940s, many interiors were shot with smaller cranes or vertically mobile dollies that permitted alternation between tight high- and low-angle setups.

Roe would go on to shoot more films now considered strong noir entries: Armored Car Robbery (1950, another flat title) and The Sound of Fury. This last, as I suggest here, promotes the same tight high angles we find in Trapped, with perhaps more fine-grained results.

Fleischer didn’t have the blasting visual force of Mann, and Roe didn’t have the baroque imagination of Mann’s DP John Alton. Still, Trapped does deliver a handsome array of long-take deep-focus shots. These attest to the influence of Citizen Kane (1941) as a prototype for dynamic compositions, often exploiting ceilings on sets.

Such angles led directors to think more about using the vertical stretch of the screen, again aided by a camera pitched slightly high or low.

One turning point, Tris’s discovery of the Feds’ bug in Meg’s lamp, is designed to exploit a slightly tipped-down framing, with the splash of light accentuating the moment of revelation.

American crime films weren’t unique in their pictorial bravado. Watching Trapped drove me back to Noose, a 1948 British film by Edmund T. Gréville. A semi-comic tale of London gangsters, it abounds in florid depth compositions. (See below.) Just more proof that the 1940s saw a new exploration of bold narrative and stylistic initiatives in sound cinema around the world. And those weren’t confined to the big productions. Once new image schemas were available, artisans at all levels could make piquant uses of them.

The Flicker Alley release is nicely filled out with informative supplements contributed by Alan K. Rode, Eddie Muller, Donna Lethal, and Julie Kirgo. Mark Fleischer offers some touching reminiscences of his father’s life and creative ambitions. Thanks as well to Jeffrey Masino and Josh Fu of Flicker Alley. And we owe a debt to the collector who deposited a 35mm acetate print at Harvard, whence it comes to us.

For more on 1940s cinematography, see our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 and entries in the 1940s Hollywood categories here. Patrick Keating’s central chapters in The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood supply a lot of information about the growing use of cranes and maneuverable dollies for intimate dramatic scenes.

Noose (1948). A Brit noir ripe for Blu-ray release.

Sometimes an actor’s back…

Il Maschera e il Volto (1919).

…can crisply punctuate a scene.

DB here:

One of the 1919 films on display at Cinema Ritrovato this year was Augusto Genina’s Il Maschera e il Volto (The Mask and the Face, 1919). It’s drawn from a popular play that satirized the erotic stratagems of the elite. The movie begins by introducing a gaggle of couples at a Lake Como house party, so I expected that it would create interlocking intrigues in the manner of silent-era Lubitsch films like The Marriage Circle (1924). Not so: the plot concentrates on one romantic triangle. The version we have, at 1799 meters, might be a little shorter than the original (said to be around 1900 meters), but it seems likely that the plot we have dominated the initial release too.

Savina is betraying her husband Paolo with the family lawyer Luciano. During the house party Paolo declares that a cuckolded husband has every right to murder the unfaithful wife. When he learns of Savina’s affair (but not Luciano’s complicity), he orders her to leave the household immediately. Paolo declares that she will become dead to him and their friends.

Paolo tells Luciano that he killed Savina. We get a lying flashback (yep, already and again) that shows him strangling her and dumping her body in the lake. Savina overhears his false confession. When she hears Luciano asserts that she got what she deserved, she realizes he’s worthless. Disillusioned about both of the men in her life, she follows Paolo’s order and leaves their estate.

Of course a woman’s corpse, face mutilated, is soon found in the lake. Now Paolo must stand trial for Savina’s murder, and Luciano must defend him.

Not the funniest comedy I ever saw, but it has a grim charm. One particular scene made me happy.

Piano ensemble

Readers of this blog know that I like to study staging in 1910s films, and Genina provided nifty examples in the 2017 Ritrovato season. Like the Lupu Pick film I reviewed at this year’s jamboree, Il Maschera lies stylistically midway between pure tableau cinema and editing-driven construction. Interior scenes are often broken up by many cuts, but they’re typically axial, straight-in and straight-back, without reverse angles. (The exception is the trial scene. As in many 1910s films, it creates a more immersive space through “all-over” cutting.) In most scenes, the shots enlarge actors to follow their responses, but we don’t get setups that penetrate the space, putting us inside the flow of action.

Still, axial cuts, as Eisenstein and Kurosawa and John McTiernan knew, have a peculiar power. They can be abrupt and punchy, or more subtle in readjusting the framings. The latter option is on display in the film’s first big scene, when all the guests gather in the salon around the piano.

The scene runs about two and half minutes and consists of twelve shots and six dialogue titles. What’s worth noticing is the slight variations in setups, coordinated with what Charles Barr has felicitously called “gradation of emphasis.” Often the changing setups are masked by an inserted dialogue title, so there are no bumps in continuity.

The orienting view is a bustling shot that piles up faces and shoulders along the horizontal axis.

In an axial cut-in, the guests debate the righteousness of Othello’s murder of Desdemona. A further cut-in shows Luciano and Savina on the far right sharing glances. (The curly-haired woman will prove an innocent witness.) It’s a Hitchcockian situation, but without the POV singles.

Soon an older husband rises from his chair in the rear (another cut-in, “through” the group) and comes forward to join them. He draws alongside the husband to calm him down.

I’ve talked about crowded tableaus like this before. The Americans I survey were somewhat bolder than Genina in jamming the heads even closer together, creating partial faces that float out of the background. Genina has, however, other goals in view.

The woman in white

During the cut-ins, Genina takes the opportunity to rearrange the actors around the piano and re-scale his shots. There are five distinct variants of the piano grouping; even setups that might seem the same aren’t quite. There are two setups of the adulterous couple. All these are calibrated to suit the action presented.

For instance, when Paolo launches his rant about unfaithful women, the framing is tighter to favor him, and the foreground woman in white is primed for her big moment.

Similarly, the second cut to the adulterous couple is framed somewhat differently from the earlier one (on left), with Luciano pushing aside the cute curlyhead. He and Savina are listening more intently to Paolo’s denunciation of faithless wives.

So what seem to be fairly straightforward repetitions of setups are in fact minutely adjusted to favor certain actions. This strategy allows Genina to return to the whole ensemble.

In a closer view, the woman in white suggests that they stop arguing about infidelity and go in to play cards. She rises, blotting out Paolo in mid-rant.

The effect would be less pointed if she were in black like the other women.

Everyone but the older husband turns away, and people retire to the next room in the distance. They drain the space like water emptying out of a tub. That leaves what filmmakers today would call the scene’s button: the old man noticing that Luciano and Savina don’t join the group. Throughout the scene they’ve been literally marginalized on the far right.

It’s through this older man we just barely see the couple leave. He seems to understand the game they’re playing. and now he watches them disappear, perhaps to a private rendezvous.

The scene ends with another turning from the camera, another actor’s back letting us know the action is done.

Very often, turning from the camera signals the end of scenes, and of films.

It would have been fairly easy for any director to simply let the actors clustered around Paolo drag him off to play cards. But by having the woman in the foreground pop up, cut off our view of Paolo, and trigger a general exit Genina makes the action taper off briskly. Staging in the silent cinema is full of such little felicities, and it’s one job of criticism to appreciate them. It’s especially important since such techniques seem no longer part of filmmakers’ skill sets.

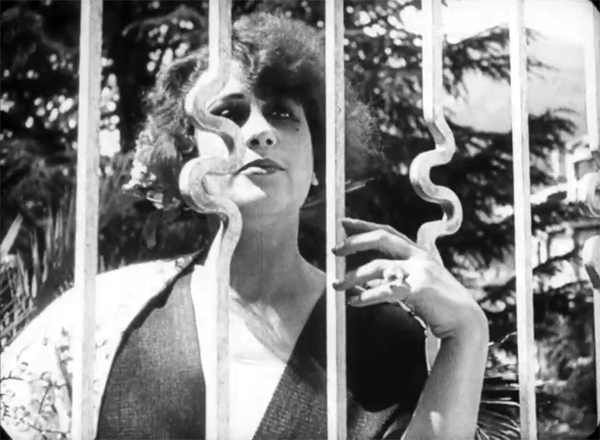

Then again, some Maschera images just whack you in the eye. Who doesn’t sense passion, elaborately caged, in the image below?

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky, and their colleagues. We particularly owe Mariann for her curating of the Hundred Years Ago series every year. Special thanks as well to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator.

Information about La maschera e il volto can be found in Vittorio Martinelli’s Il Cinema Muto Italiano: I film del dopogerra/1919 (Rome: Bianco et nero, 1960), 170-172.

Other Sometimes... entries consider a single axial cut, a shot in depth, a jump cut, a reframing, and a production still.

Il Maschera e il Volto (1919).