Archive for the '1910s cinema' Category

More Bologna bounty

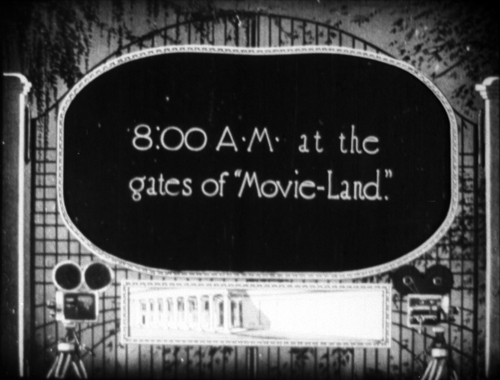

I think this has become my favorite Ritrovato key image.

DB here:

Cinema Ritrovato rolls on, leaving your obedient servant little time to blog. Herewith some quick impressions on a thin slice of all that’s going on. For a full schedule of this incredible event, go here.

IB or not IB

“Not all IB Tech prints are created equal,” explained Academy Film Archivist (and UW–Madison grad) Mike Pogorzelski. In his last of his annual Technicolor Reference Print shows, he pointed out that Technicolor sent its best-balanced prints to big-city venues and circulated them widely. As a result, they got worn out. The prints most likely to survive were less-than-perfect ones sent to the hinterlands or just kept as backups. Hence the need to preserve the Reference Prints selected by the filmmakers as defining the Technicolor timbre of each film.

With clips ranging from The Godfather and Let It Be to Sssss and Billy Jack, the sample gave a good sense of what Tech looked like a few years before the imbibition (IB) process was abandoned in 1974. Mike and Emily Carman introduced the extracts with informative commentary. I had always thought that Gordon Willis’s cinematography on the Godfather films and The Parallax View increased graininess, and this show seemed to confirm that sense.

Those naughty pre-Code pictures, again

The John Stahl and William Fox retrospectives brought some spicy material. Women of All Nations (1931), Raoul Walsh’s episodic sequel to What Price Glory?, had Quirt and Flagg on the verge of all-out cussing in nearly every scene. A monkey wriggling inside El Brendel’s trousers created moments of good dirty fun. Bachelor’s Affairs (tee-hee, 1932) had Adolph Menjou peering down a golddigger’s front and praising her virtues: “What a charming combination.” She asks if it’s showing. Likewise this repartee: “Were you out last night?” “Not completely.”

William Dieterle’s Germanic Six Hours to Live (1932) begins as a political thriller and devolves into a Twilight Zone fantasy. A representative of a small country passionately protests worldwide tariff legislation. To keep his vote from vetoing the action, spies target him for elimination. Soon enough, he’s throttled to death. But an enterprising scientist takes the opportunity to try out his resuscitation ray, which gives the hero a few more hours to make his mark.

John Seitz photographed the whole farrago in glowing imagery shot through with shafts of blackness, alternately soft-focus and crisply edged. Here’s the magic machine.

The film’s look is an example, I suppose, of what Andrew Sarris once called “Foxphorescence”–the signature of a studio that, from Murnau and Borzage to Ford and 1940s noirs, played host to dazzling pictorial effects.

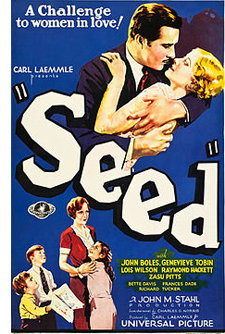

Not completely naughty, but certainly a film about sexual jealousy, was Seed (1931), one of the most anticipated films of the Stahl cycle. It lived up to its reputation as a masterly orchestration of sympathies. At the center is a love triangle based on two women’s roles: the mother and the businesswoman.

Aspiring author Bart Carter has given up his novel, and he lives–he thinks–happily with his wife Peggy and five rambunctious kids. When his old flame Mildred returns to the publishing firm Bart works for, she encourages him to keep writing and to stray from the household Peggy has made for him.

Aspiring author Bart Carter has given up his novel, and he lives–he thinks–happily with his wife Peggy and five rambunctious kids. When his old flame Mildred returns to the publishing firm Bart works for, she encourages him to keep writing and to stray from the household Peggy has made for him.

As often happens in Hollywood, the plot works only if the man is a jerk, and the action will set up things to make the woman take the blame. Mildred may not have schemed to pull Bart away from the start, but the shift in our sympathy to Peggy is pretty decisive. The film’s patient pace and stringently objective presentation lets contrasting feelings get developed gradually. The kids, particularly the whining runt of the litter, are annoying and troublesome. Mildred is no obvious predator, Peggy is trying valiantly to accommodate Bart’s ambition, and he’s enjoying his vacation from fatherhood while still struggling, albeit weakly, to stay loyal to his family.

Stahl was one of the major long-take directors of 1930s Hollywood, and Seed is exemplary in this respect. (The average shot lasts about twenty seconds.) His back-to-basics two shots, facing off characters in profile, become the default setting; there are scarcely any reverse angles or eyeline matches. This apparently simple creative choice, anticipating Preminger’s method of the 1940s and 1950s, puts all characters on an equal footing. The framings force us to concentrate on their conversation, avoiding the customary cuts that punch up particular lines or reactions. A similar steady observation is at work in Stahl’s fine Imitation of Life (1934) and Magnificent Obsession (1936).

1918 and all that

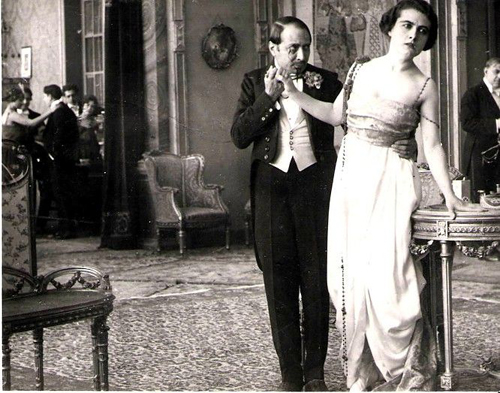

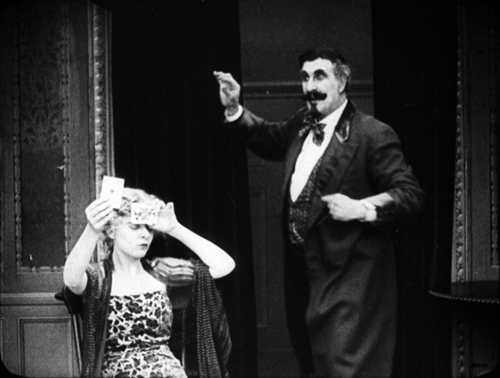

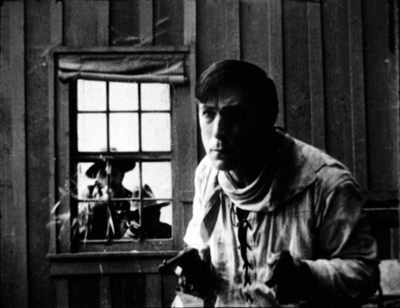

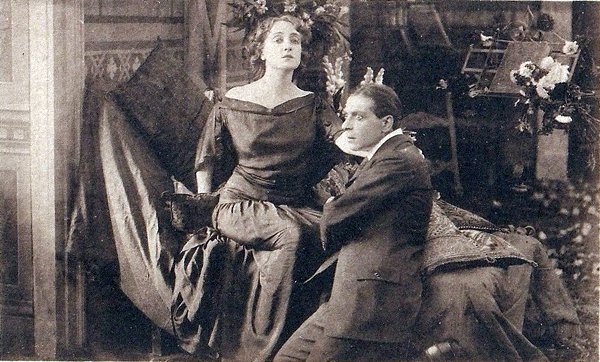

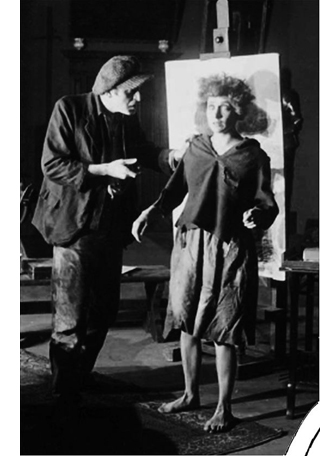

L’avarizia (1918). Production still.

Regular readers of this blog know that one area of my research is the stylistics of 1910s cinema in various countries. (Check the category tableau staging for a sample.) Naturally I dropped obsessively in on the 100-years-ago strands at this year’s Bologna. While there are more films to come, I found plenty to enjoy and think about in the first few days.

There was, for instance, Der Fall Rosentopf, a fragment of a farcical Lubitsch feature. Ernst plays his Sally character, now a detective investigating a flower-pot mystery. Lively enough, the surviving nineteen minutes from early scenes didn’t give me much sense of the whole.

Alongside it were two other comedies. Gräfin Küchenfee featured Henny Porten in a dual role, both countess and kitchenmaid. When the countess goes off to have fun, the maid assumes her identity. Eventually, the two women switch roles when the countess tries to evade police charges by pretending to be the maid. No less predictable in its comic situation was Puppchen, in which a young woman working in a fashion salon breaks a lifelike mannequin and must take its place. It may have been a model for Lubitsch’s Die Puppe (1919).

Stylistically, all these films were fairly staid, with little intricate staging, and they lacked analytical editing apart from axial cuts in and out. Their reliance on longish takes probably reflected the fact that US films, with their bold continuity editing, weren’t available in Germany until somewhat later.

One American film also rejected the emerging Hollywood style, in the name of naivete and fancy. That was Prunella by Maurice Tourneur. It doesn’t survive complete, and it’s been known for many years as a failed venture into artiness. The flat sets resemble children’s book illustrations, and the performance style is wilfully arch. I’ve never found Prunella very interesting, but it does offer further evidence that the 1910s harbored some eccentric and ambitious experiments.

Gustavo Serena’s L’Avarizia impressed me more. It too relies on frontal acting and axial cutting, but as a vehicle for the great diva Francesca Bertini it seemed to me completely engrossing.

As part of a series illustrating the Seven Deadly Sins, it offers a starkly symmetrical plot. Maria and Luigi love each other, but each is dominated by an old miser. Her aunt and his father each amass a fortune in secret while manipulating the young people. Through a series of conspiracies and misunderstandings, the lovers are flung apart. Maria, friendless and illiterate, sinks down, down into the bottom of society.

Each step of the way is given powerful expression by Bertini’s face, gestures, and bearing. She grabs her hair to yank her head back; she blows cigarette smoke in Luigi’s face to show her contempt for his abandonment of her. At one high point, when Luigi falsely accuses her of infidelity, she wrestles with him on a tabletop, giving no quarter. In a tavern fight she pulls a knife before falling to the floor, writhing feverishly in what appears to be her last moments on earth. This is silent opera, with the soaring melody carried by the body.

Up against the fourth wall

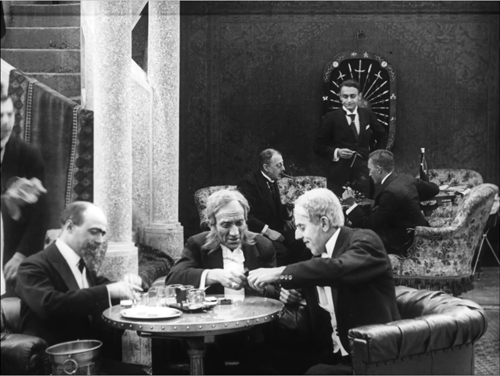

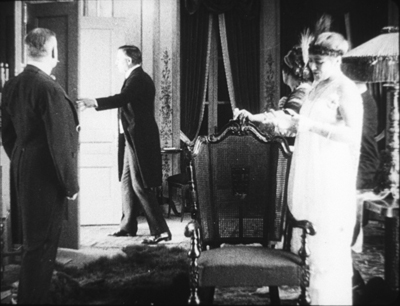

A meeting of the Antifeminist Club (The Oriental Language Teacher).

I wasn’t surprised to find a diva film full of sensuous appeals, but the big revelation of the 1918 cycle so far was the Czech comedy The Oriental Language Teacher (Učitel Orientálních Jazykû). It showed what you could do with a small cast, a few sets, and a cut-and-dried situation.

Sylva secretly falls in love with Algeri, who’s tutoring her in Turkish. After her father is being considered for a diplomatic post in Turkey, he decides to learn the language. He arrives during one of Sylva’s lessons, so she quickly disguises herself as an odalisque. Needless to say, Father is smitten with this exotic beauty. Add in his membership in the Antifeminist Club, led by a comic geezer who enjoys snapping clandestine photos of passing women, and insert deceptions involving a pianola roll, and you have some substantial complications.

Most striking from a pictorial standpoint were the very deep sets–modeled, stylistic historian Radomir Kokes tells me, on the Danish cinema of the period. The co-directors Olga Rautenkransovå and Jan S. Kolár present Sylva’s parlor in an unusual way. Most films of the period put foreground desks and tables at a diagonal bias. But here the father’s desk is thrust very close to us, perpendicular to the camera, and it runs the entire length of the frame.

Moreover, the father is centered at his desk, when the more normal placement would set him to left or right and clear a space in the other half of the frame for other characters. The depth, that is, is typically horizontal. Here, though, it’s also vertical. A character must descend the stair directly above the other, in a maniacally centered composition that’s mildly beguiling in itself.

The set depicting Algeri’s studio is a little more typical of the period, since his desk is placed off to one side, but every shot of this setup makes the foreground area curiously out of focus.

Given that the control of focus is precise in the parlor shots, the slightly fuzzy foreground of the studio set remains anomalous–an error, or a decision to differentiate the two spaces more sharply. In any case, here’s another example of how 1910s movies, from all corners of the world, can set you thinking about the possibilities of pictorial design.

More to come in the next entry, with a special focus on trial films.

Special thanks to Radomir Kokes for help with this entry. More generally, thanks to the Bologna leaders and staff for a tightly-run and ever-exciting event, along with the archivists who made these films available. In particular we owe a lot to Marianne Lewinsky, who curates the Cento Anni Fa series, and to Dave Kehr who, grinning, shares what he called on the first day MoMA’s “mildly obscure” treats. And Imogen Sara Smith gave an exceptionally lucid introduction to Seed.

For more on diva acting, see Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema, a book available here, and this entry by Lea on Bertini. Kristin wrote about Prunella and other mildly experimental Hollywood films in Jan-Christopher Horak’s Lovers of Cinema collection.

For more on-the-spot pictures, check our new Instagram page.

John Bailey, President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and Michael Pogorzelski.

ON THE HISTORY OF FILM STYLE goes digital

Dust in the Wind (1986).

DB here:

I was born to write this book.

So I rashly claim in the Preface to the new edition of On the History of Film Style. That’s not to say somebody else couldn’t have done it better. It’s just that the book’s central questions tallied so neatly with my enthusiasms and personal history that I felt an exceptional intimacy with the project.

So I rashly claim in the Preface to the new edition of On the History of Film Style. That’s not to say somebody else couldn’t have done it better. It’s just that the book’s central questions tallied so neatly with my enthusiasms and personal history that I felt an exceptional intimacy with the project.

Baby-boomer narcissism aside, there are more objective reasons for me to tell you about the book’s revival. It came out in late 1997 from Harvard University Press, and it went out of print last fall. Thanks to our web tsarina Meg Hamel, it has become an e-book, like Planet Hong Kong, Pandora’s Digital Box, and Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages.

The new edition is substantially the original book; the pdf format we used didn’t permit a top-to-bottom rewrite. Errors and some diction are corrected, though, and the color films I discuss are illustrated with pretty color frames, not the black-and-white ones in the first edition. The new Preface and a more expansive Afterword explain the origins of the book and develop ideas that I pursued in later research.

The book analyzes three perspectives on film style as they emerged historically. One, what I call the Basic Version, was developed in the silent era and saw the discovery of editing as the natural development of film technique.

The second version, associated with critic André Bazin, modified that conception by stressing the importance of other stylistic choices, notably long takes and staging in depth. I call this the Dialectical Version because Bazin claimed that these techniques were in “dialectical” tension with the pressures toward editing.

A third research program, spearheaded by filmmaker and theorist Noël Burch, argued that the development of film style was best understood as the ongoing interplay between two tendencies. There’s a dominant style Burch called the Institutional Mode. Responses to that mode are crystallized in alternative practices–the cinema of Japan, for instance, or the “crest-line” of major works associated with modernist trends.

The book goes on to show how a revisionist research program launched in the 1970s built upon these earlier perspectives. Younger scholars sought to answer more precise questions about certain periods and trends. The revisionist impulse is best seen in debates on early cinema, which I survey.

The book so far is historiographic, tracing out other writers’ arguments about continuity and change in film style. In my last chapter I try to do some stylistic history myself. I analyze particular patterns of continuity and change in one technique, depth staging. Certain conceptual tools, like the problem/solution couplet and the idea of stylistic schemas, can shed light on how certain staging options became normalized in various times and places. In turn, directors like Marguerite Duras, in India Song (1975), can revise those norms for specific purposes.

On the History of Film Style was generally well-received. John Belton, while voicing reservations, called it “a very good book. Anyone seriously interested in Film Studies should read it.” Michael Wood wrote in a review that “Bordwell is always sharp and often funny” (I try, anyhow) and called the last section “a brilliant account of the history of staging in depth.” The book has been used in some courses, and I’m happy to learn that there are filmmakers who find it useful. It’s been translated into Korean, Croation, and Japanese.

The book is available for purchase on this page. It’s priced at $7.99, a middling point between our other e-pubs. It’s a bigger book than Pandora ($3.99) and the Nolan one ($1.99), but it’s not an elaborate overhaul like Planet Hong Kong 2.0 ($15). Selling the book helps me defray the costs of paying Meg and digging up color frames. In any event, the new version is much cheaper than the old copies available at Amazon. It’s almost exactly the price of two Starbucks Caffe Lattes (one Grande, one Venti).

The archives and festivals that made the book possible are thanked inside, and they’ve continued to be hospitable and encouraging over the last two decades. Equally supportive are the students, colleagues, and cinephile friends with whom I’ve discussed these issues. So I reiterate my thanks to them all. And I hope this new edition, if nothing else, stimulates both viewers and researchers to explore the endlessly interesting pathways of visual style in cinema.

La Mort du Duc de Guise (1908).

Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight

Idle Wives (1916), produced by Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley.

DB here:

This year I’ve been bouncing between two magnificently creative decades in US film, the 1910s and the 1940s. In autumn I’ve been caught up in things involving Reinventing Hollywood, but those were followed by some big doings on campus.

In spring I was lucky enough to be in residence at the John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress. That enabled me to watch nearly a hundred feature films from 1914-1918. I did a talk at the Library reporting on some of that work, and I’ve offered some preliminary observations on those in earlier entries.

Last week, Jim Healy of our UW Cinematheque brought some of the films that had impressed me during my DC stay. There was a Saturday marathon of The Iced Bullet (1917), Alias Jimmy Valentine (1915), The Bargain (1914), Will Power (1913), and The Man from Home (1914). For our Film Studies Colloquium across two Thursdays we screened False Colours (1914; incomplete), The Case of Becky (1915), Idle Wives (1916; incomplete), and Ben Blair (1916). Some of these I’ve written about in earlier entries, here flagged by links.

The Saturday screenings were accompanied by the lively, indefatigable playing of David Drazin. David worked for many hours and without having seen the films in advance. He’s a superb artist.

Seeing the films again, of course I found more to say.

Revival and revision

The Case of Becky (1915).

One of the secondary arguments in Reinventing Hollywood is that many storytelling techniques of silent film subsided during the 1930s but were revived during the 1940s. Silent films were full of dream sequences, subjective points of view, fantasy projections, and flashbacks. Those got elaborated and consolidated for the sound cinema by Forties filmmakers.

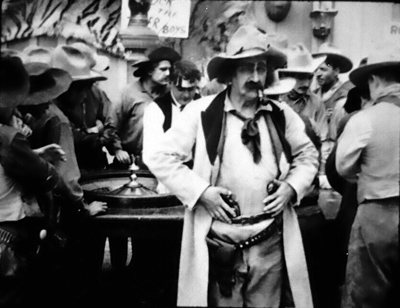

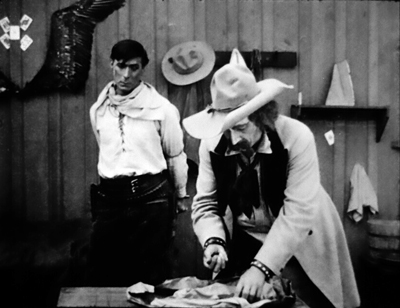

So it wasn’t surprising to find that The Bargain, a fine William S. Hart western, squeezed a lot of mental imagery into a single scene. The Sheriff has arrested Jim Stokes and retrieved the money he stole. Lashed to the bedpost, Jim remembers his wedding and the woman he’s betrayed, presented in a slow dissolve to the past.

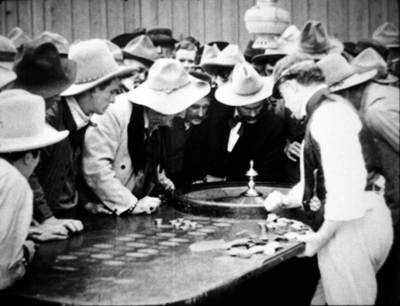

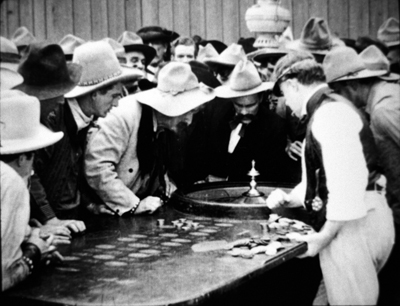

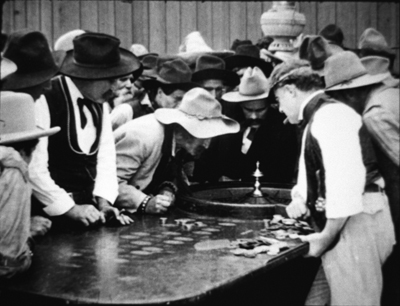

Meanwhile, downstairs in the saloon casino, the Sheriff succumbs to an impulse and loses all his money at roulette. Then he remembers, via another dissolved-in flashback, that he scooped up the stolen money too.

Back in the present, he digs that money out of his poke and bets it—and loses.

Later, in the hotel room, Stokes learns of the Sheriff’s folly and has a good laugh. But then he imagines Nell waiting for him, shown in a split-screen image.

At which point the Sheriff imagines his telegram arriving at his town, announcing Jim’s capture and the recovery of the money. That vision reminds him that he can’t return without the money he has squandered.

This makes him strike the central bargain with the thief he’s captured.

In a 1930s film, these visualized memories would most likely be presented verbally, as part of the stream of dialogue. (“When I think of marrying Nell….””I’ve promised to bring the money back…”). But 1910s American films tended to use dialogue titles sparingly; a lot of the films we saw asked the viewer to grasp the situation without benefit of words. The Bargain has only nineteen dialogue titles in 77 minutes (at 16 frames per second).

The Bargain is a good example of how purely pictorial storytelling was used to explicate a situation. Interestingly, today’s films are rather close to this tendency: fragmentary flashbacks and mental visions are common in mainstream movies.

Another echo struck me, this time in The Case of Becky. This is an early story of split personality, a narrative premise popularized after The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886). Here the young woman Dorothy (Blanche Sweet), under the sway of the sinister hypnotist Balzamo, develops a second identity, the surly and disruptive Becky. Becky isn’t really very dangerous, but when a young doctor, himself a master of hypnosis, falls in love with Dorothy, he determines to cast out Becky. He does so in a passage of intense mind control, visualized through a double exposure of Becky departing Dorothy’s body.

What interested me is that the same visual device was used by Arch Oboler in Bewitched (1945), one of the earliest psychoanalytical films of that era. The heroine’s two sides are summoned up by the shrink.

I suspect that Oboler got wind of the Selznick/Hitchcock Spellbound (1945) and rushed a B-film into production. (He could move fast because he adapted one of his radio plays.) Bewitched was released five months before the Selznick/Hitchcock film. It’s not great movie, but it has a sort of pre-Psycho pitilessness, and it’s always nifty to see a 40s film picking up on a silent-film device.

Cutting things up and filling the corners

My main research questions about the 1910s revolved around stylistics—matters of staging, lighting, shot scale, variety of camera setup, and editing choices. For about twenty years I’ve been exploring how, to put it broadly, the long-take, intricately staged tableau cinema was largely replaced by films dependent on continuity editing. By focusing on the years 1914-1918, I thought I could track the transition in finer grain.

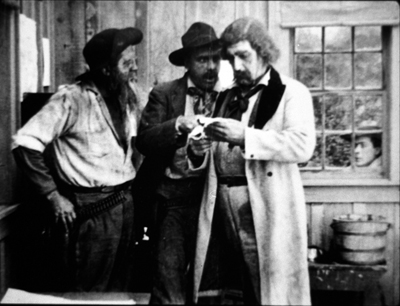

Many films were already building their scenes out of several shots. Go back to The Bargain, from 1914. A series of shots shows Stokes surrounded at the door and window, while also giving us a brief shot from a new angle incorporating tight depth, as the men at the window get the drop on him.

This freedom of camera placement within a single set is typical of the Hart films (see here and here), and of other films by Reginald Barker. It was sometimes visible in Alias Jimmy Valentine from the year before (1913), but it’s more pronounced in The Bargain. Several scenes in the hotel room where Stokes is tied up display a fairly wide array of camera setups.

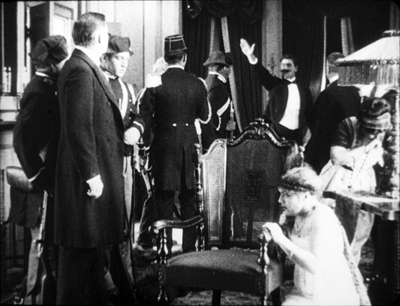

At the other extreme, The Man from Home (1914), credited to Cecil B. De Mille and Oscar Apfel, displays the tableau approach in full bloom. One long take at the climax shows a packed salon. To take just the high points of some pretty dense choreography: Ivanoff bursts in to confront his errant wife, who crumples in the lower right.

Pike holds off the Earl of Hawcastle, now partnered with Ivanoff’s wife. Hawcastle rushes to the right rear to open the curtains (stepping into a spotlight). Summoning the police, he returns to the middle ground to demand the arrest of the fugitive Ivanoff.

But a functionary arrives in the background, lifting his arm to signal the arrival of the bearded Grand Duke Vasili. Vasilii stalks in to take command of the middle ground and confront Hawcastle. Throughout. shrewd shifts of actors’ position open pockets of action, and the performers turn from the camera to drive our eye into depth.

Throughout most of this tableau, broken by occasional titles, Ivanoff’s treacherous wife is crouching in the lower right. This is an example of the “all-over staging” we find in 1910s cinema. Often corners and edges of the frame will be activated and demand to be noticed. For example, in The Bargain Stokes is observing a scene through a window. Cut inside the room, and Stokes can be seen way off to the right in a single pane.

Later directors would have placed the window nearer frame center so that Stokes’ face would be more quickly noticed.

Sometimes we find the filmmaker trusting the audience—or at least a modern audience—too much. In Ben Blair (1916), Ben is lured into a brothel and pulls his pistol in order to escape. But in the master shot, off to the right, the astute viewer can see the louche Sidwell, who’s aiming to marry Flo, cozying up to a hooker before he rises to flee the room. He has already met Ben and fears being recognized.

Director William Desmond Taylor doesn’t supply what I expect Barker would provide: a separate shot of Sidwell seeing Ben and rushing out of the room. Nor does Taylor provide a gradually unfolding tableau that would, by means of figure movement, frontality, centering, and other cues build to a crescendo revealing Sidwell’s presence—the sort of thing we see in The Man from Home. As it is, many viewers may miss the main point of the scene, which is to divulge Sidwell’s sexual betrayal of Flo.

But maybe this was best. Cutting straight in to Sidwell might have suggested that Ben recognizes him immediately. But he doesn’t. As Ben turns, Sidwell is ducking away. Ben has revealed, and seems to be concentrating, on a new center of interest, the woman who’s impudently blowing out cigarette smoke at him. He, like us, is distracted from Sidwell’s departure.

Still, we’re supposed to spot Sidwell even if Ben doesn’t. Only much later, after Sidwell has nearly convinced Ben to give up on courting Flo, does Ben realize that it was Sidwell he saw in the brothel. That’s done through a split-screen flashback of Sidwell starting guiltily beside his floozy.

Again, the shot is a little clumsy in showing Sidwell looking toward the camera, as if Ben saw him directly; but it seems to be another mental image, representing Ben’s now-clear impression that Sidwell was in the brothel.

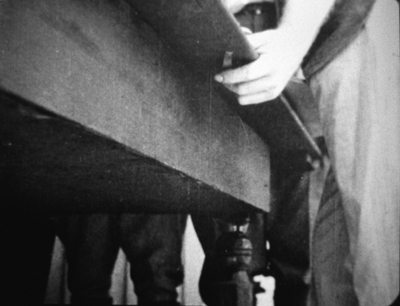

We don’t have to puzzle over such matters in The Bargain. Barker had mastered the precision necessary for off-center details. When the Sheriff is risking his money at the roulette wheel, a close-up reveals that the croupier is controlling it.

But here’s the neat part. At the turning point, when the Sheriff loses everything, Barker gives us close-ups of the Sheriff and the croupier, but not the hand pressing the button.

We’re sufficiently trained to spot the croupier pressing the button in the long shot (again, off-center). There’s no need to show the gesture again because the priming close-up has told us the game is fixed. Interestingly, that insert shot doesn’t come at the very start of the Sheriff’s gambling jag, so initially we might think the wheel is honest. We get the revelation just when the Sheriff is about to bet the money he can’t afford to lose. That boosts the dramatic tension.

Movies within movies

The Iced Bullet (1917).

While stylistics was my prime research focus, I couldn’t help but notice some bold narrative initiatives. A good example of a playful one was The Iced Bullet (1917), which has a Russian-doll structure (like many 40s films).

The inner tale recounts how a scientific detective solves an attempted murder, one using the method tipped in the title. But that’s swallowed up in a prologue and epilogue showing a foppish author crashing the Ince studio. He manages to interfere with filming, evade the guards, and take refuge in an executive’s office. He has brought along his screenplay, The Iced Bullet, which he hopes to direct and star in.

At the desk he falls asleep and dreams the detective story we see. At the film’s end he wakes up and flees the studio, pursued by watchmen. One trade paper of the time suggests that the comic frame story was devised in order to expand and elevate the murder story–which may explain why the film has been credited to both Reginald Barker and Charles Swickard. Maybe one directed the frame story and one the embedded one.

As the frame story stands, it offers us not only a comic pretext but precious views of the vast Ince studio.

There are also some nerdish in-jokes. C. Gardner Sullivan, author of the whole film we see, appears as the executive whose office is commandeered, while Barker shows up as a raging director trying to get the aspiring screenwriter off the set.

And when that invader takes over Sullivan’s office, he scoffs at a huge bust of William S. Hart, by now a major star.

The year before, Lois Weber and her husband Phillips Smalley had given us a more intricate film-within-a-film structure. The central story of Idle Wives centers on the plights of three women. Anne Wall is a wealthy but disillusioned wife who leaves her husband John to take up settlement work. She lives with Alberta, who has married John’s brother Richard. The couple has been disowned by John’s mother and sister. In her charity duties Anne meets Molly Shane, who has left her family to run off with the no-good Larry. Anne helps Molly through her pregnancy and reconciles her with her family. John, seeing how Anne has changed the lives of unfortunate women, welcomes her back and faces down the disapproval of his mother and sister.

This story is enclosed within another one, involving three other women. The Jamiesons, though wealthy, have an empty marriage. When Jamison meets an old girlfriend, they decide to go see a movie. They’re trailed by Mrs. Jamieson. At the same time, Mary Wells disobeys her mother and goes out with the thug Tough Burns. They wind up going to the same movie theatre. And the poor, hard-working Smith family, whose daughter is longing to escape, decides to take a day off and go to the theatre as well. All of them join the audience for Life’s Mirror, a film by none other than….Lois Weber. It stars Weber and Philips Smalley, who’s given his own poster.

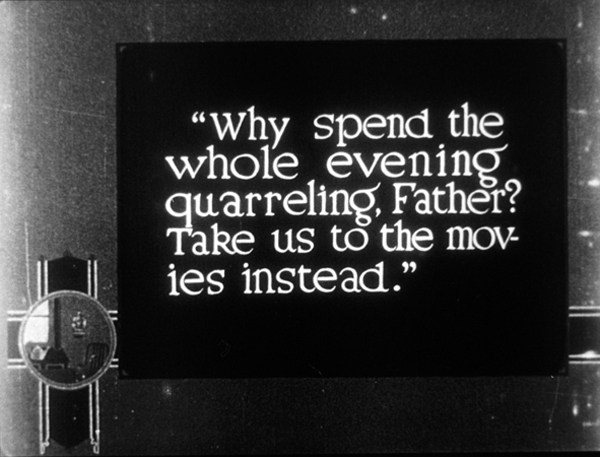

This frame story, not in the source novel, is pretty stunning. In the first reel the people assemble at the theatre, which, as you see up top, flaunts the Weber-Smalley brand. These scenes are fascinating representations of moviegoing culture of the time, showing the ticket booth and the auditorium.

Just as important is the way that seeing the movie affects the characters in the frame story. Shots show people in the audience reacting to the fictional world.

The point of the film is that the characters, recognizing their counterparts on the screen, improve their behavior. Cinema is granted the power to divine the problems of its audience, and to heal their lives.

Or so we’re told from contemporaneous synopses. Because, in one of the great losses of American silent cinema, we have only the first and second reels of Idle Wives. Fortunately, those constitute the prologue and the initial exposition of the inner story.

How does the frame story turn out? According to the fullest contemporary account I’ve seen, in the epilogue Jamieson sees his wife weeping in the aisle, sends her rival away, and reconciles with her. Mary is shocked into realizing the risk of dating Tough Burns, who seems ready to reform after seeing his fictional double behave so cruelly. The Smiths agree to be kinder to one another, and the daughter of the family realizes the danger of fleeing home.

Two network narratives, then, in a single movie. Idle Wives has over twenty individuated characters, linked by kinship or domestic circumstances. (For instance, in both stories some characters live in the same building.) It becomes didactic, as Weber’s films often are, with the theatre presenting a placard that underscores the lessons, and opening titles that address the audience directly. Idle Wives was fairly described by a review as “a preachment on the sacredness of the home, also on the power of the motion picture.”

For most film historians, the great experimental film of 1916 was Intolerance, another tale of parallel situations and fates. But the same month that Griffith’s ungainly masterpiece was released saw the appearance of Idle Wives—in its way, no less daring, and by today’s standards startlingly modern. How many other remarkable films have been lost or have gone unnoticed? Like archaeologists excavating a site, we have a lot more digging to do to understand the glories and unpredictable experimentation of the cinema of the 1910s.

Thanks to my hosts at the Kluge Center last spring: Ted Widmer, Emily Coccia, Travis Hensley, Callie Mosley, Mary Lou Reker, and Dan Turello, as well as the team in the Moving Image Research Center–Karen Fishman, Dorinda Hartmann, Josie Walters-Johnston, Zoran Sinobad, Rosemary Hanes, and Alan Gevinson–along with the Culpeper dynamic duo Mike Mashon and Greg Lukow. We in Madison are especially grateful to Lynanne Schweighofer and George Willemen for preparing a reconstructed version of Ben Blair. Thanks also to Jim Healy, Mike King, and Roch Gersbach for arranging the Madison screenings.

Some of David Drazin’s piano accompaniments are available on DVDs from Texas Guinan (that’s right, tguinan at aol.com).

Idle Wives has been posted online by the New Zealand Film Archive and the Library of Congress. An informative puff piece from the era is “The Smalleys Turn Out Masterpieces With Actors or With Types,” The Moving Picture Weekly 3, 14 (18 November 1916), 18-19, 26. The most comprehensive guide to Lois Weber’s career is Shelley Stamp’s Lois Weber in Early Hollywood (University of California Press, 2015). I discuss the Smalleys’ little masterpiece Suspense (1913) here. Reinventing Hollywood has a chapter on the psychoanalytic cycle of the 40s, including Bewitched.

On all-over staging, and bungling the tableau, see the entry “Looking different today?” We have some entries on decentered framing, one on Mad Max: Fury Road and another on Fritz Lang’s use of corner frame space.

Idle Wives (1916).

Ritrovato 2017: Drinking from the firehose

DB here:

Immense scale and teeming activity are nothing new to Il Cinema Ritrovato, the Cineteca di Bologna’s annual jamboree of restored and rediscovered films from all over the world. The scorching heat–90 degrees and more for the first few days–only makes it seem more intense than usual.

Kristin and I had to miss the last Ritrovato session, but we’re convinced that this nine days’ wonder is still the film-history equivalent of Cannes.

In one way, your choice is simple. You can follow one or two threads–say, the Robert Mitchum retrospective or the Collette and cinema one or the classic Mexican one, or whatever–and dig deep into that. Or you can skip among many, sampling several, smorgasbord-style.

In practice, I think most Ritrovatoians pursue a mixed strategy. Settle down one day for a string of, say, early Universal talkies and another day check out the restored color items. On off-days roam freely. The problem is you will always, always miss something you would otherwise kill to see.

At the start, I plumped for 1910s films, particularly Mariann Lewinsky’s reliable 100 Years Ago cycle. My other must was the Japanese films from the 1930s; half of the titles brought by Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström, were new to me. As of this writing, I haven’t seen those, but I have dug into the 1917 items. And I indulged myself with, no surprise, some gorgeous Hollywood things.

1917 and all that

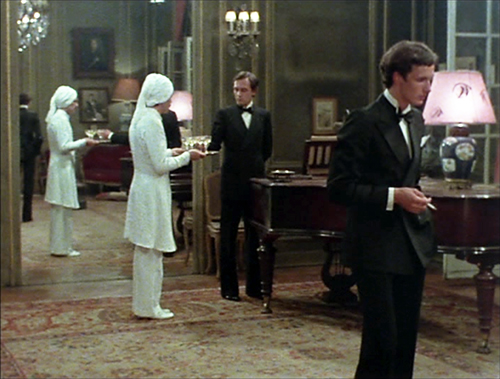

Malombra (1917).

If you caught any of my dispatches from Washington DC earlier this year (starting here) you know I was burrowing deep into American features of the 1910s That complemented several years of archival work on European films of the same period. So of course the chance to sample 1917 features from Hungary, Poland, Russia, and elsewhere was not to be passed up.

Some superb ‘teens films I just skipped through familiarity. Gance’s Mater Dolorosa (1917), possibly the most patriarchal film in the thread, remains tremendously inventive at the level of silhouette lighting and continuity cutting (a huge variety of camera setups during the fatal love tryst). And one of the very greatest directors of the period, Yegenii Bauer, was represented by two of his last films, The Revolutionary and Towards Happiness. I’ve studied both elsewhere, in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and online. Even so, I found plenty to keep me busy.

One of the main threads was devoted to Augusto Genina, a director with an astonishingly long and prolific career. Probably best known for Prix de Beauté (Miss Europe, 1930), he started in 1913 and made his last film in 1955. His 1910s films confirm that Italy was producing many films of striking beauty and audacity in those years.

Take Lucciola (1917, right), the story of a waif who befriends a harbor layabout but leaves him to become a society princess admired by a debonair painter and three bulbous plutocrats. Pivoting from social satire to low-life melodrama, the film makes use of bold lighting and meticulous cutting, usually along the lens axis. (Like many European films of the ‘teens, Lucciola lies sort of between tableau cinema and the faster-cut American style.) All in all, a strong, tight movie.

Take Lucciola (1917, right), the story of a waif who befriends a harbor layabout but leaves him to become a society princess admired by a debonair painter and three bulbous plutocrats. Pivoting from social satire to low-life melodrama, the film makes use of bold lighting and meticulous cutting, usually along the lens axis. (Like many European films of the ‘teens, Lucciola lies sort of between tableau cinema and the faster-cut American style.) All in all, a strong, tight movie.

In a similar vein is Addio, Giovenezza! (1918), adapted from a popular song. This one, screened in an open-air venue thanks to an arc-lamp projector, is another sad Genina tale. A careerist law student abandons his rooming-house maid for a social butterfly with a wardrobe to die for. Apart from one startling scene in a milliner’s shop, illuminated mostly by spill from the street, the lighting isn’t as daring as in Lucciola. Still, the poignant plot is again inflected by comic touches, proceeding largely from the hero’s nerdish fellow student. Genina redid the story again in 1927, and I’m hoping to catch that screening.

Malombra (1917), starring the diva Lyda Borelli, was by the great Carmine Gallone. (I’ve discussed La Donna nuda and Maman poupée hereabouts.) After moving into a castle, Marina becomes possessed by the spirit of the woman who died there. Our heroine’s job is to take revenge on the faithless husband. Flirtatious and iron-willed, Borelli dominates her scenes with shifts of stance, sudden freezes, rapid changes of expression, languorous arm movements, and, at one climax, a swift undoing of her hair that lets it all tumble wildly around her face. The print, needless to say, was superb.

In a lighter vein, if you wanted proof of the inventiveness of ‘teens Italian film, you couldn’t do better than Wives and Oranges (Le Mogli e le arance; 1917). This agreeably silly movie sends a bored young man to a spa populated by incredibly aged parents and a bevy of scampering daughters. With an avuncular friend, Marcello capers with the girls before settling on the most modest one as his wife. But her friends aren’t disappointed because our hero’s pals come for a visit and get roped into matrimony too.

Wives and Oranges has a remarkable freedom of narration. The film uses montage sequences with a fluidity that is rare at the time. To convey the boredom of Marcello’s daily routine, a string of quick shots is punctuated by changing clock faces. Later, the idea of finding one’s ideal love mate by matching halves of oranges is presented via an absurd montage of old folks, youngsters, babies, and just abstract hands, all wielding oranges.

Marcello’s paralyzing dilemma of choice is given as a nondiegetic insert of a donkey unable to decide between a hay bale and a bucket of water. These flashy devices keep us interested in a situation that, in script terms, is probably stretched too thin–although when things slow down you can count on the daughters forming a chorus line and zigzagging down the road or popping out from under the dinner table one by one.

Almost as lightweight was The War and Momi’s Dream (La Guerra e il sogno di Momi, 1917), by the great Segundo de Chomón, who moved among France, Spain, and Italy making fantasy films of many types. This one is largely meticulous puppet animation, in which a boy’s toys come to life and enact–at the height of the World War–their own combat.

Trick and Track marshall other toys to play out some seriocomic clashes, including a burning farmhouse and one astonishing shot of an entire town landscape, covered in a long camera movement. Again, there’s no underestimating the sheer technical audacity of Italian cinema of these days.

There’s always an exception, of course. The late David Shepard left us, among much else, Shepard’s Law of Film Survival: The better the print, the worse the movie. A good example is La Tragica fine di Caligula Imperator (1917), signed by Ugo Falena. It’s surprisingly retrograde for an Italian film of the period. Neither the staging (flat, distant) nor the cutting (minimal) nor the lighting (little modeling) is much in tune with contemporary norms. The problem may be the immense sets, which are indeed impressive but which seem to encourage the actors to a hard-sell technique.

The most amped-up is Caligula himself. Playing a mad Roman emperor often tempts any actor to gnaw table legs. But as an example of what a silent film really could look like, Caligula should be required viewing for anybody who sneers at Those Old Movies. If Christopher Nolan saw it, he’d demand to shoot on orthochrome nitrate.

Other 1917 features included The Soldier on Leave, from Hungary, and Stop Shedding Blood!, by the great Russian director Jakov Protazanov. The former was restored from a 17.5mm copy, the latter was missing the two central reels. The Protazanov in particular had some sharp staging in depth and rich sets.

In the same batch was Pola Negri’s screen debut in Bestia (1917, imported to the US as The Polish Dancer). In a fine copy, you could appreciate the bouncy but sultry screen presence that made her a star. And as often happens with films from anywhere in this period, the sets sometimes play peekaboo with the action. Pola, after a night out with her thuggish lover, sneaks back to her bed while her father snores in the background, caught in a slice of space.

Back in the USA

Kid Boots (1917).

The 1917 American entry was a strong, unpretentious Western by Frank Borzage, Until They Get Me. It’s missing some scenes in the middle, but it remains a forcefully quiet movie. The only gunplay takes place at the start, when a man racing to get to his wife in childbirth is forced into a gunfight. He kills the drunkard who provoked it, but by the time he reaches his home, his wife is dead. Now he must flee Selwyn, a mountie. Stealing a horse, he picks up an orphan girl fleeing an oppressive household. The rest of the film will intertwine the fates of the three, leading to a surprisingly civilized resolution.

Borzage is one of the many great directors–De Mille, Dwan, Walsh, Ford, Brown, King, Barker–who started doing features in the mid-teens. Most had long careers. They mastered the emerging norms of Hollywood continuity cinema and learned to deploy them with tact and precision. Just the timing of the reaction shots in Until They Get Me is worth study.

Frank Tuttle started in features a bit later, in 1922, but Kid Boots (1926), my first movie of the Ritrovato, showed complete mastery of comic storytelling. Eddie Cantor, a fired tailor, becomes amanuensis to Tom Sterling, a man-about-town in the throes of a divorce. The twist is that his wife, learning of Tom’s new inheritance, wants to halt the divorce by sharing his bed again. Eddie’s job is to keep the wife and the lawyers at bay until the divorce becomes final. Into this tangle plops perky Clara Bow in her first film after her breakout role in Mantrap (also 1926). You could watch her cock her chin and roll her eyes for hours. She steals the picture from Billie Dove.

The gag situations come thick and fast, with one high point being Eddie’s efforts to get Clara jealous by recruiting a strategically open door to help him pretend that his left arm actually belongs to Tom’s seductive wife. The whole thing culminates in a breathless chase on horses along a treacherous mountain pass. Eddie and all the others keep things lively, and Tuttle’s direction is exacting.

I strayed from the ‘teens again at Dave Kehr’s urging. Of Dave’s magnificent MoMA restorations, I caught William K. Howard’s Sherlock Holmes (1932). Apart from a wild-eyed Ernest Thesiger and an imperturbable Clive Brook, it boasts an abstract opening of silhouettes and confrontational close-ups and a conclusion of percussive flashes as Moriarty’s gang torches its way into a bank.

Ace cinematographer George Barnes had a field day with this one.

That was followed by Tay Garnett’s Destination Unknown (1933), a tense drama of a crisis on a bootlegging ship immobile on a windless sea. Hard, fast playing by Pat O’Brien and Alan Hale was offset by the leisurely presence of none other than Ralph Bellamy, aka Jesus of Nazareth. Don’t ask; just see it.

More from me, and Kristin, later in the week.

Thanks to Guy Borlée for a great deal of assistance on this entry. Thanks as well to the programmers and staff of the festival, especially Gian Luca Farinelli and Mariann Lewinsky.

The Ritrovato site is constantly updated. For our earlier Ritrovato communiqués, go here.

Malombra (1917; production still).