Archive for the '1910s cinema' Category

Picturing performance: THEATRE TO CINEMA comes to the Net

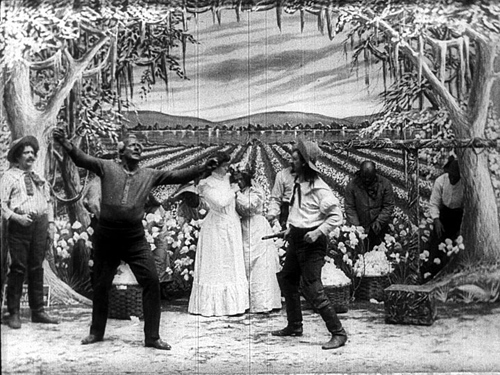

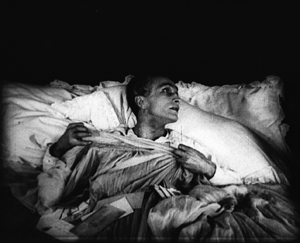

Ma l’amor mio non muore! (aka Love Everlasting, 1913). Lyda Borelli.

DB here:

The core of cinematic expression is editing. Since the 1920s, that view has been part of the lore of film aesthetics. Editing, people said, is what distinguishes film from other media. After all, the single shot is both a picture (like a painting) and a dramatization (like a scene in a stage play). But put one shot with another and you’ve got a technique impossible to parallel in other media.

But if we look closely, we find that the film image is as “uniquely cinematic” as editing. After all, a film is an image, but it’s a moving image, which is sharply different from a painting. And although a shot is a dramatization, it’s two-dimensional (unlike a stage scene) and the space it captures is quite different from that of the theatre. Anyhow, maybe editing isn’t uniquely cinematic. Comic strips juxtapose discrete images, and some forms of theatre (such as pageants, or turntable stages) can shift rapidly between scenes. Once we start to compare adjacent media, we find many overlaps in their expressive resources.

Why did early film theorists make editing so important? They were often defending the view that film was a new art, in the teeth of opponents who claimed that it was simply photographed theatre. Accordingly, film’s defenders looked for features of films that seemed to have no counterpart in theatre, such as the close-up and, more pervasively, editing.

Since then, we’ve come a long way in our understanding of film’s artistic capabilities. Filmmakers, particularly those in the early sound era (Renoir, Ophuls, Dreyer, Mizoguchi), showed the expressive power of the single shot. This tendency was amplified in the 1950s and 1960s with Antonioni, Jancso, Andy Warhol, and many other directors. Now nobody blinks if a filmmaker like Hou or Yang presents a lengthy, unedited sequence.

Informed by what’s possible in the single shot, we ought to find the earliest filmmakers using the resources of staging, composition, and performance in felicitous ways. So we do. Once we foreswear the cult of the cut, we can see that early cinema made extensive use of cinematography and mise-en-scene for powerful artistic effects. And conceding that, we suddenly find ourselves back in the lap of the other arts–painting and theatre.

Living pictures

No one has done more to clarify the debt of early cinema to theatre than our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs. In the spirit of Wisconsin Revisionism, they have embraced early film’s stagy side. They’ve taught us to appreciate the ways in which dramaturgy and performance of 1910s cinema derive, in unexpected ways, from the theatre. Their trailblazing book Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford, 1997) showed how to appreciate early films in a whole new way: by seeing them as borrowing and modifying conventions of the stage. What may look artificial or backward to us were actually tools of subtle, supple expression.

No one has done more to clarify the debt of early cinema to theatre than our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs. In the spirit of Wisconsin Revisionism, they have embraced early film’s stagy side. They’ve taught us to appreciate the ways in which dramaturgy and performance of 1910s cinema derive, in unexpected ways, from the theatre. Their trailblazing book Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford, 1997) showed how to appreciate early films in a whole new way: by seeing them as borrowing and modifying conventions of the stage. What may look artificial or backward to us were actually tools of subtle, supple expression.

Here’s the authors’ statement of the book’s argument:

While previous accounts of the relationship between cinema and theatre have tended to assume that early filmmakers had to break away from the stage in order to establish a specific aesthetic for the new medium, Theatre to Cinema argues that the cinema turned to the pictorial, spectacular tradition of the theatre in the 1910s to establish a model for feature filmmaking. The book traces this influence in the adaptation and transformation of the theatrical tableau, acting styles, and staging techniques, examining such films as Caserini’s Ma ľamor mio non muore!, Tourneur’s Alias Jimmy Valentine and The Whip, Sjöström’s Ingmarssönerna, and various adaptations of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

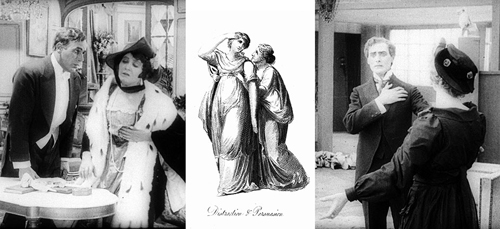

The twist here is that turn-of-the-century artistic culture had already blurred the boundaries between theatre and painting. Painters drew upon the stock gestures and poses of the stage, while plays presented vivid visual effects that were indebted to painting. The term “tableau,” referring at once to a picture and a poised stage image, captures this convergence between the media. That’s why Ben and Lea refer to “stage pictorialism” as the nexus of their inquiry.

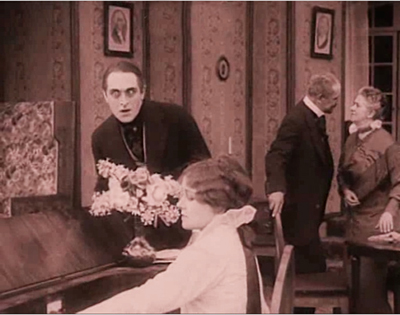

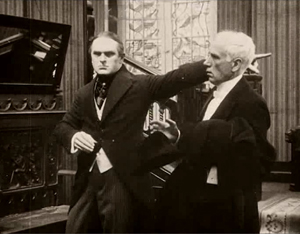

Thanks to their research, we can see the unbroken long- or medium-shot of early features as permitting a complex choreography of facial expressions and bodily attitudes, which were in turn indebted to both pictorial and dramatic traditions. Standard gestures were summoned up and reworked to suit dramatic situations–as, for example, clutching.

When we do find editing or camera movements in these films, they’re often at the service of the performance style. Ben and Lea powerfully make the case that the expressive human body was at the center of storytelling in the first years of silent cinema. (If nothing else, the book is an in-depth analysis of diva acting from the likes of Lyda Borelli and Asta Nielsen.) By studying the history of theatre, we can learn to appreciate aspects of acting that might otherwise escape our notice.

Theatre to cinema to pixels

Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Slavery Days (Edison, 1903).

How, you’re asking, can you gain access to the ideas and information and images in this fine book? It’s now criminally easy.

When Theatre to Cinema was published, all the illustrations came from 35mm film prints. Those originals were gorgeous. But in some printings of the book the stills came out badly, and when the book moved to print-on-demand status, the images suffered even more. A couple years ago, Ben and Lea rescued their book and took the opportunity to make a digital version. It’s unrevised, largely because updating a twenty-year-old volume would be a major overhaul, but errors have been corrected and–very important–the stills have been much improved.

Start here, with the introduction to the project. You can download the new edition of the whole book, section by section, here.

Naturally, Kristin and I are sympathetic to this effort. Since we started our website back in 2000, we have explored ways to amplify and extend our ideas by means of the web. In the beginning, and inspired by Philip Steadman’s Net-based supplements to his excellent Vermeer’s Camera, I added material that would enhance arguments I made in Figures Traced in Light. Then we set up our blog, now in its tenth year. Over the same period, we posted web essays, as you can see in serried ranks page left. We also used the site to preserve older material, such as film analyses dropped from editions of Film Art: An Introduction and even entire books, as in Kristin’s 1985 monograph Exporting Entertainment. We’ve mounted video lectures. And we’ve produced a new edition of an older book, Planet Hong Kong 2.0, and original e-books such as Pandora’s Digital Box and Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages.

Ben and Lea have found another way to expand a book’s Web life. They have put Theatre to Cinema at the heart of a digital collection sponsored by the University of Wisconsin–Madison Libraries. Here’s what they offer:

In this collection, we try to supplement the description and illustration that accompanied the book in a way that makes it easier for readers to appropriate our work—both to understand it, and to make use of it in research and teaching. What were illustrations in the pages of the book are also presented here as better-quality downloadable images.

For example, you can pick a still, find its mates in a single display, and blow it up for scrutiny. If you want import it into your own files, you may choose among four different file sizes.

The provenance of each still is provided, so scholars can compare prints from different sources. In addition, there’s a master index of the visual documentation, in sequential groupings across the book.

Finally, Ben and Lea plan to add video extracts from some of the films they discuss. When those go up, we’ll announce it here.

Every admirer of silent film, and everyone who studies the interrelationship of the arts, should read this book. Hard copies are still being sold online, but they’re apt to be versions with weakly reproduced stills. Get one if you want, because a book is a good object to have in hand. In addition, for free, you can own a beautiful, searchable edition with superb stills. I think you need both.

The digital collections set up by UW Libraries are breathtaking. Check them out here.

Some entries on our site intersect with Ben and Lea’s research. See the category Tableau staging.

Weisse Rosen (White Roses, 1915). Asta Nielsen.

The return of Homunculus

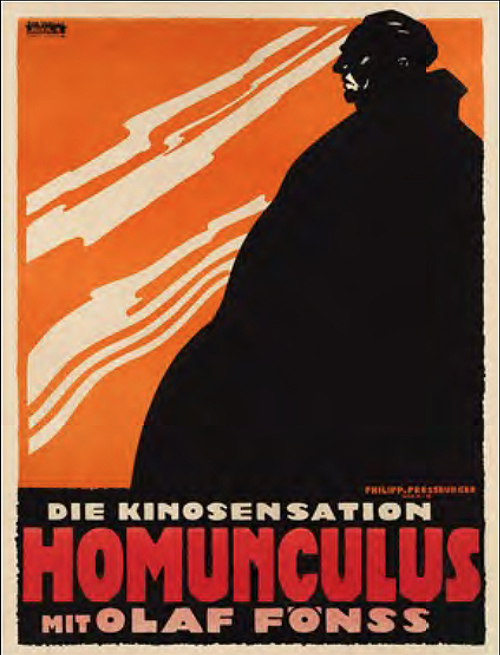

On 21 November, the Museum of Modern Art in New York will be screening a version of Otto Rippert’s long-lost German serial Homunculus (1916). It was reconstructed by Stefan Drössler and his colleagues at the Munich Film Museum on the basis of material from the Moscow Film Archives and other collections. Here’s the background offered by the opening titles on this version.

Homunculus was shown as a six-part series in movie theaters in Germany and its occupied territories in 1916, in the midst of World War I. Each episode was about an hour long. In 1920 the opus was reissued as a three-part version. Scenes were shifted around and new intertitles added.

The following reconstruction adapts the structure of the reissue edition, but it also contains some scenes that had been shortened for the later version and often only survived as photographs.

Fewer than 20% of the original German intertitles have been preserved or are known in their exact wording. Newly worded texts for this reconstruction were based, when possible, on information from contemporary program notes and reviews; also, some were translated back from foreign-language versions of the film and others were created from keywords scratched into the film as montage cues.

For the first time, the current work print makes it possible to recognize the original concept of the entire series.

Today, as a preparation for this very important event, each of us offers you something. First Kristin sketches the trend of fantasy filmmaking in German cinema of the 1910s. After providing this context for the film, David offers some thoughts on this new version of Homunculus and its value for us today.

Kristin here:

The seeds of Expressionism

Many viewers who come to Homunculus for the first time may be expecting traits of the most famous German silent film trend, Expressionism. And indeed historians have mentioned Rippert’s serial, along with Der Student von Prag (The Student of Prague, 1913), Hoffmanns Erzählungen (Tales of Hoffman, Richard Oswald, 1916), and others, as forerunners of the Expressionist movement.

But we don’t have a very concrete account of how these earlier films led up to the more famous trend that began with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari’s release in early 1920. Moreover, at first glance there aren’t many visual qualities in these earlier films that remind you of Expressionism. They display few or none of those Expressionist distortions of mise-en-scene influenced by contemporary trends in painting and theatre. Similarly, the acting, while exaggerated in a fashion common during the 1910s, seldom reaches the extreme stylization of the performances in Expressionist films.

Yet there are clearly some other similarities between the two groups of films. Most obviously, the early films brought to prominence two related genres to which many of the Expressionist films would belong: the phantastischen film and the Märchenfilm, or fairy-tale film.The main examples of the latter all starred Paul Wegener: Rattenfänger von Hameln (The Pied Piper of Hameln, 1918), Hans Trutz im Schlaraffenland (Hans Trutz in the Land of Cockaigne, 1917), and Rübezahls Hochzeit (Rübezahl’s Wedding, 1916).

For Expressionist filmmakers, elements of the supernatural or the legendary could motivate highly stylized mise-en-scene. In contrast, these 1910s films often used relatively realistic mise-en-scene. Location shooting, straightforward period costumes, and skillfully executed trick photography introduced the fantastic elements into the milieu of a concrete, seemingly everyday world.

A changing view of cinema

Despite such differences, the two genres provide a specific link between some of the most prominent German films of the 1910s and those of the Expressionist movement. Moreover, fantasy films seem to have provided a basis for at least a tentative exploration of theoretical issues surrounding the relationship of cinema to the other arts. In Germany, cinema had previously been compared primarily to literary and theatrical arts, but Wegener’s Der Student von Prag and other films led to a wider consideration of cinema in relation to visual arts such as painting.

In a 1916 lecture, Wegener expressed dissatisfaction with most of what had previously been done with the cinema. He sought to establish the cinema as an independent visual art, separated from theatre and literature:

When a new technology is developed, it is initially cultivated in relation to existing ones, and a new idea does not immediately find its own unique form. The first steamboats looked like big sailing schooners, except that instead of masts they had high funnels. The first railway cars copied mail coaches, the first automobiles kept the large bodies of landaus, and the cinema was like pantomime, drama, or the illustrated novel.

A more broadly based view of the cinema as combining theatrical and graphic arts created a newtradition which carried over from the 1910s to the Expressionist movement of the 1920s. These early films may have become models for the development of an “art cinema” movement in the next decade.

The painterly approach to film promulgated by Wegener lingered in German cinema for about a decade. Starting around 1924, a new approach, based on the moving camera and a more realistic three-dimensional space, would largely replace the older one.

Frames and books

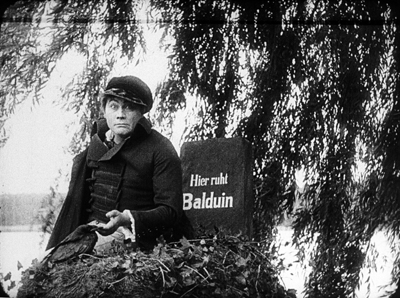

Der Student von Prag.

Aside from this specific link created by Wegener’s emphasis on the pictorial powers of the camera, several conventions of the fantasy films of the 1910s look forward to Expressionism. Perhaps most notable among these devices is the use of the frame story.

Expressionist films frequently employ this device: Francis’ tale to the fellow asylum inmate in Caligari, the record of the Bremen town historian in Nosferatu (as well as the imbedded narratives of the Book of the Vampyres and the ship’s log), the young poet hired to write publicity anecdotes for a sideshow in Wachsfigurenkabinett, and so on.

Yet this pattern was already well established during the 1910s. Der Student von Prag begins and ends with a poetic scroll (“Ich bin kein Gott/bin kein Dämon …”), with the final return leading to a shot of Balduin’s gravestone—upon which sit the Doppelgänger and a crow. (The 1926 remake, which has some distinct Expressionist touches, begins and ends with a gravestone that summarizes Balduin’s life.) Wegener’s other major surviving film from the mid-1910s, Rübezahls Hochzeit, begins with a scene of Wegener, as himself rather than in character as the titular hero, reading to a group of children from a book entitled Rübezahls Hochzeit.

In some cases the frame story introduces multiple embedded narratives. Richard Oswald’s two main fantasy films of the pre-1920 era, Hoffmanns Erzählungen (1916) and Unheimliche Geschichten (Uncanny Stories, 1919), both use this technique. The first begins with a prologue showing Hoffmann surrounded by strange characters like Count Dapertutto and Coppelius. Three dream sequences show him incorporating these figures into bizarre stories; the transition from the prologue to the the main portion of the story begins with Hoffmann in bed as the three sinister figures stand over him.

Unheimlische Geschichten begins, as an intertitle announces, with “A fantastic Prologue at an antiquarian book dealer’s.” On the wall are three large pictures depicting a whore, death, and the devil. After the proprietor chases away his customers and departs, the three images come to life and amuse each other by reading tales out of a book. The series of embedded tales, adapted from Poe, Hoffmann, and other authors of the uncanny, form the bulk of the film.

Not all fantasy films of the 1910s contain frame stories or embedded narratives. Characters do, however, often read or write books that contribute major premises or motifs. In Homunculus, Richard Ortmann keeps a large diary, which records his shifting and somewhat contradictory thoughts, feelings and goals—and thus conveys them to us. Joe May’s Hilde Warren und der Tod (Hilde Warren and Death, 1917) also has no frame story. Its opening, however, involves the heroine reading in a book that death is an escape from sadness. This notion becomes a motif, as the figure of Death appears to her at intervals, foreshadowing her eventual surrender. Books would become an important motivating device in Expressionist films, introducing embedded narratives or crucial motifs.

Hilde Warren und der Tod also carries through the pictorial tradition of Der Student von Prag. Here the special effects are not used to allow one actor to play two roles through split exposure. Rather, superimpositions introduce the figure of Death into the everyday scenes of Hilde’s life.

Some early hints of Expressionism

Although the fantasy films of the 1910s don’t contain strongly Expressionist elements, a few stylistic touches foreshadow the distortions of the later movement. Some of these relate to performances by actors who were to become central to the Expressionist movement. In Hoffmanns Erzählungen, for example, Werner Krauss’s stylized acting in the role of Count Dapertutto suggests why he was later cast as Dr. Caligari. Conrad Veidt’s acting and especially his makeup as Death in Unheimliche Geschichten mark him as the ideal candidate to show up in Caligari’s cabinet.

The stylized hand gestures in these two shots are particularly striking, and the same device is carried through in a séance sequence in Unheimliche Geschichten. The lighting of the séance looks forward to more famous scenes in Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1922), Feu Mathias Pascal (1926), and The Ministry of Fear (1944)—yet here Oswald introduces a twist by including one more hand than there should be for the number of bodies present.

There are other major films made in 1919 which contain stylistic and generic elements soon to become far more prominent. Lang’s Die Spinnen (The Spiders, 1919-1920) draws upon conventions of the thriller serial which would soon by transmogrified in his Expressionist film, Dr. Mabuse, Der Spieler. Lubitsch’s Die Puppe (The Puppet) and Die Austernprinzessin (The Oyster Princess), both 1919, could be counted as comic Expressionist films that introduced the style into the cinema months before the appearance of Caligari. The exact cut-off date between pre-Expressionism and Expressionism proper is not vitally important. Some 1910s developments in genre and style prepared the way for Expressionism. Caligari, however great its stylistic challenges were, did not appear in a vacuum.

DB here:

Wanted: Love. #Homunculus

The 1920 reissue of the Homunculus serial compresses its original story considerably, but the outlines are clear. Some omissions in the Munich reconstruction may reflect gaps in the 1920 version. Still, the basic outline of the tale is clear.

Very likely the first test-tube baby, the Homunculus arrives on the scene as the result of a pseudoscientific effort to create life. Out of a bubble, properly zapped, comes an infant.

The baby is brought up in an ordinary human family, thanks to the classic switched-in-the-cradle device. Known as Richard Ortmann, the creature grows up into something of a superman, with extraordinary strength and explosive energy. But his core is hollow. Richard discovers that he lacks fellow-feeling and finds himself alienated from his carousing peers.

When Richard discovers his technological origin, he sets himself a drastic choice: either discover human love or destroy this worthless world.

Each episode replays the same dynamic. Somewhere Richard discovers a possibility of uncorrupted love. But that prospect shatters, either because of prejudice (would you want your daughter to marry a homunculus?) or his sadistic urge to plunge the world into chaos. Only his friendship with Edgar Rodin, one of the scientists who attended his birth, forms an enduring bond across the episodes.

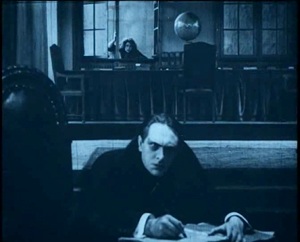

Richard Ortmann plays many roles in his saga. He’s a scientific tinkerer who invents an explosive, a wanderer who ventures into Africa, and a capitalist who enjoys masquerading as a rabble-rouser bent on fomenting rebellion. No sooner has he provoked a war than he tries his own social experiment, that of isolating a young couple in hope of breeding a new society. All these exploits he records in a mighty book

This tome becomes a handy narrative device when the plot demands that other characters learn of his inhuman origins.

Like those films that clone a Stallone or a Van Damme, the series realizes that one monster can be defeated only by another one. The long tale comes to a climax when Rodin creates a second Homunculus and raises him up to conquer Ortmann–already somewhat weakened from age and fear of death. The titanic confrontation is played out on mountain craigs.

Who will win? Or will both perish?

Annihilation, courtesy Homunculus

The rocking-horse rhythm of the episodes, with hope for Ortmann’s redemption rising and inevitably falling, takes some getting used to. To the filmmakers’ credit, they vary the prospects for love: an array of women, a dog, and in the fourth episode a woman who wholeheartedly embraces Ortmann’s wicked side.

Today’s viewers will also need to accustom themselves to the seething extremes of Olaf Fønss’s performance. Fønss was a major Danish actor who became famous in Atlantis (1913) and who migrated to Germany to star in this series. Fønss conceives his performance as a matter of ferocious glares, raised fists, and heroically villainous postures. It looks overdone to us today.

His box cape, reminiscent of bat wings, helps the brooding effect.

But this isn’t merely a matter of old-fashioned hamming. Fønss’s performance is calibrated to be ragingly different from the other portrayals. Most of the actors exaggerate less, and the pacifist preacher actually underplays. Fønss goes over the top because Homunculus does.

What makes the series compelling? For one thing, it offers a fairly original reworking of the Frankenstein premise. For another, its central conceit of a mad, misunderstood supervillain in search of love can evoke some empathy. There’s also the effort to convey a world in flames, to suggest a cosmic catastrophe with minimal means. While the Great War devastates Europe offscreen, one can hardly avoid thinking of trenches and bombardment in blasted shots like these–which also look forward to the jagged decor of Expressionism.

The student of film technique will, I think, be struck by the filmmakers’ pictorial ambitions. It’s now clear that by focusing just on The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) we have limited our sense of the wide-ranging visual discoveries of German cinema. Homunculus belongs with the splendid string of films that includes Der Tunnel (1915), Algol (1920), I.N.R.I. (1920), and the outstanding pair of 1919 films by Robert Reinert, Opium and Nerven. Reinert, unsurprisingly, wrote the screenplay for Homunculus.

The fourth episode, which I commented on back in the summer (based on a much inferior copy), remains a treat for your eyes, with unexpected camera angles and daring use of depth. In the one on the left, we see touches of Expressionist performance in the orchestration of hands.

Elsewhere Kristin has remarked that during the 1910s filmmakers began to go beyond basic storytelling and explore the expressive dimensions of cinema—not only in acting but also in composition, lighting, and set design. The Jugendstil curves of the incubator gleam inside a cavernous chamber you might not expect to find in a lab.

Other episodes provide both grand images—landscapes, sumptuous sets, crowd scenes—and an arresting, small-scale play of light and shade. A purely expository shot of Ortmann approaching Steffens’ study becomes a little suite of shadow patterns, stressed when Ortmann pauses and swivels to the camera and creates a pictorial climax.

Seeing the three-dimensional lighting effects of German cinema of the mid-1910s onward, I wonder whether Caligari‘s jutting, broken-up planes and painted shadows are not only a borrowing from Expressionist painting but also a reaction against the rich volumes created by directors like Rippert.

In all, Stefan Drössler and all the archives and individuals working with him have done world film culture a great service. As with Gance’s Napoleon and Lang’s Metropolis, more footage may appear and need to be integrated into this version. Perhaps some day we’ll have something approaching the full scope of the original series. For now, we should be thankful that another silent classic steps out of the shadows and forces us to rethink what we thought we knew about the history of cinema.

Many thanks to Stefan Drössler for his assistance in preparing this entry.

At Nitrateville Arndt has posted helpful synopses of all six parts of the restoration. Leonardo Querisima offers a wide-ranging discussion in “Homunculus: A Project for a Modern Cinema,” in A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decades, ed. Thomas Elsaesser and Michael Weidel (Amsterdam University Press, 1996), pp. 160-167. Excerpts can be found here.

Kristin’s discussion of fantasy films is excerpted from her essay “Im Anfang War…: Some Links between German Fantasy Films of the Teens and the Twenties,” in Before Caligari: German Cinema, 1895-1920, ed. Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli (Pordenone: Bibliotexa dell’Immagine, 1990), 138-161. The Wegener quotation is from Paul Wegener, “Die künsterlischen Möglichkeiten des Films,” in Kai Möller, ed., Paul Wegener: Sein Leben und seine Rollen (Hamburg: Rowohlt Verlag, 1954), p. 102. Translation by KT.

Elsewhere on this site we discuss other neglected German films of the period: Der Stoltz der Firma (The Pride of the Firm, 1914); Der Tunnel (1915); Asta Nielsen features of the teens; Doktor Satansohn (1916); Hilde Warren und der Tod (1917); Die Pest in Florenz (The Plague in Florence, 1919, directed by Rippert after Homunculus); late-1910s Lubitsch; Algol and I. N.R.I. (both 1920); and Der Golem (1920). I have an essay on Robert Reinert’s remarkable films in Poetics of Cinema. Some day I hope to write more about Paul Leni’s war drama Das Tagebuch des Dr. Hart (Dr. Hart’s Diary, 1917) and Joe May’s energetic and entertaining serial Die Herrin der Welt (Mistress of the World, 1919).

Silent frame rates and DCP: A guest essay by Nicola Mazzanti

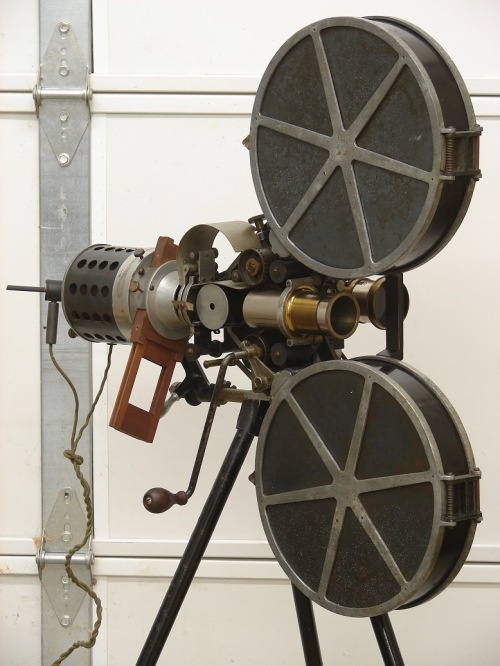

1914 Kinetoscope Victor Model I Silent Film Projector by the Victor Animatograph Co. From Pinterest, identified by Robert Van Dusen.

DB here:

The first thing you learn about silent movies is that they weren’t shown silent. The second thing is that they weren’t shown as fast as we often see them. Screened at 24 frames per second (“sound speed”), many films look rushed and silly. Those were shot at slower frame rates, like 16 fps or 18 fps. By the end of the 1920s, though, some were shot faster than sound, up to 30 fps.

Most archives and some cinémathèques and repertory theatres owned adjustable-rate film projectors, so they could provide a smooth flow of motion for most silent films. But what happened when film projectors were junked and replaced by digital projectors? How could the Digital Cinema Package (DCP), that set of files containing the movie and a host of encryption devices, offer the various “silent speeds”?

I wrote a little about this problem in Pandora’s Digital Box: Films, Files, and the Future of Movies, but afterwards I continued to wonder how archives were coping with the matter once digital conversion was universal. The main problem is that digital projectors don’t currently provide options slower than 24 fps. Both the Hollywood studios that established the digital standard and the manufacturers that implement it simply ignored the history of cinema. Where does that leave archives, which restore, circulate, and show silent films on digital equipment?

So I asked our friend Nicola Mazzanti, Curator of the Cinematek in Brussels, about this problem. Nicola is one of the founders of the Bologna Cinema Ritrovato festival and a major consultant about digital cinema and the preservation of films in the new age. Here’s his typical provocative, pro-active answer.

Why can’t we ever make it simple?

Nicola Mazzanti, Brussels summer 2011. The plaque reads: “Mr. Bill Clinton, President of the United States of America sat at this table on 9 January 1994. He drank coffee and chatted an hour with all present.”

When they try to sell you some new product there is always the sweet thrill that now, finally, all the unpleasantness and the drawbacks, the little things that bothered you in the past, will be gone forever. Then, you realize that the car you bought was a Volkswagen diesel.

With Digital Cinema we were all told that life would be happier once we jumped onto the bandwagon. Distribution of independent films would be easier. All sorts of catalogue titles would flow joyously from the archives to the multiplex. “Alternative content,” including slightly unsharp TV programs and opera with awful close-ups and great sound, would make theatre owners rich.

Many believed the PR. Some of this became true—the usual 10% of it.

Granted, it is easier and cheaper to produce and manage a DCP than a 35mm print. And some classics did find their way to independent or repertoire theatres (the few who survived the digital switch, that is). Several archives, ours included, are enjoying these benefits of the digital switchover. And advertising an 8K or 20K or whatever-K restoration can bring in audiences. But many of us also have tons of perfectly fine 35mm of classics, and they cannot be shown any more. Why not?

*35mm projectors are basically gone.

*Some catalogue owners permit screening only their “restored DCP” (and strictly with English or French subtitles – so much for cultural diversity!).

At the end of the day the number of available classic titles went down, not up.

We could talk about this situation a long time, but let’s home in on one effect of the digital transition. The story I want to tell today is one about those “technical details” that we seem never able to get right. Only the Gods of Cinema know why.

We could talk about screen ratios in this connection, but not today. Today we talk about frame rates.

Toward a standard

Unlike video files but like a strip of film, a DCP consists of a bunch of individual frames that play nicely one after the other. The number of frames that are played back per second is defined by a simple line of code in an XML file. From the point of view of the technology in the server and the DCP format, there is no reason why we cannot play a film at any rate we like, say, 17fps. (Granted, we can’t really run it at 100fps, because of bandwidth, but you see my point.)

This is not the whole story. First of all, there is a need for a highly standardized system, or we would have the problem of a DCP playing well in one theater and at the wrong speed in the next. Then there are other issues, like the frequency of the projector or the link between the server and the projector. I will not bore you with the details. In sum, technical problems make it impossible to build what I had proposed in the first place: a hand-cranked digital projector. (I was serious.)

Yet all these technical problems could be solved, if we took a rather pragmatic approach. (Here, “pragmatic” is the PC term for “compromise.”) That’s what we archivists did, a few years ago.

At the time of publication, the Digital Cinema Initiative specs described something that did not really exist yet. The technology was only almost there. In the hurry to produce a standard that could work, it was perfectly sensible to start with only two frame rates: 24 and 48 (for 3D).

Some time later though, the issue of expanding the frame rates options came back with a vengeance. The strongest push was coming from European broadcasters who wanted to sneak their boring stuff to the cinema screens and thus called loudly for a 25fps frame rate. Then some filmmakers like Peter Jackson and James Cameron fell in love with the idea of higher rates, like 30fps and 60 for 3D (regardless of how this would balloon production budgets).

Soon the issue became geopolitical, with the Europeans pushing hard for 25fps, mostly because they considered it a victory to impose another standard on the Americans—even though they had lost the digital war as a whole. At the end, the Pandora’s box of frame rates had to be reopened, enthusiastically by some, reluctantly by others.

The Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE) set up a workgroup where all strong views in favor or against were represented. For the historians among you, it was first called “DC28-10 Ad-hoc Group on Additional Frame Rates” and later “21DC.10 AHG Additional Frame Rates.” We archivists, following our typical model of guerrilla resistance, sneaked onto the panel.

Technically, the archival force was the Technical Commission of the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF). Actually, it was Torkell Sætervadet and I who were volunteered for this “mission impossible.” Torkell is the world’s greatest expert on projection. He wrote the indispensable handbook for film projection, The Advanced Projection Manual (2006). His FIAF Digital Projection Guide, another must-read, was published in December 2012, the year film projection disappeared.

Torkell and I worked on the frame-rate problem for a couple of years. We mostly revised documents and conducted conference calls late at night (thanks to European time zones). We received some support from the more corporate members of the Workgroup. Many had never heard of lower frame rates, and the concept actually fascinated them. We also benefited from the support of Kommer Kleijn from IMAGO (the European version of the ASC), Paul Collard (then Ascent Media, now Deluxe, a profoundly competent person in the business), and Peter Wilson of High Definition and Digital Cinema Ltd.

The result: We succeeded to a great extent. We convinced the workgroup that silent rates had to be part of digital projection. True, the new standard allows only four other rates: 16, 18, 20, or 22. (To be extra-precise, due to technical issues, 18fps is in fact 18.18181818 and 22 is really 21.8181818.) But four options are quite a lot, and we decided that four were better than none.

So what we called the Archive Frame Rates standard (technically ST 428-21:2011) became part of the SMPTE standards for Digital Cinema. It can be found here. More or less in parallel, other frame rates were allowed: 25, 30, and 60fps. An announcement of this development, with commentary, can be found here.

Hurray! But don’t celebrate yet.

The Archival Frame Rates standard is not a mandatory one. The manufacturers of Digital Cinema projectors never implemented this particular standard in their machines. And archives all over the world never requested it before purchasing a projector. That, today, is the roadblock to proper screening of silent films on adjustable digital projection.

Home-made silent speed

Well, what are the alternatives?

One can produce, for example, a normal DCP at 24fps, and then use a simple piece of software (such as EasyDCP) that allows for different speeds if the DCP is played back from a computer. That feeds directly into the projector, bypassing the projector’s server. It works fine, although you have to try out several frame rates until you find the one that does sit well with the refresh rate of your projector. Otherwise, you might have some artifacts onscreen.

Alternatively, if your film’s chosen silent speed is 16fps you can easily triplicate each frame and create a 48fps DCP which would play in most theatres. 20fps would fit into 60fps, when available. For 18 and 22, however, this is no solution; they are tough frame rates anyway.

The problem with these as hoc solutions is that they are not universal. If an archive ships a DCP to another archive, someone acquainted with that file must be in the booth with a computer. Or you can just send the DCP and hope it works. Either of the two digital solutions can be used safely only in your own theatre, basically.

Hence my interest in pushing for a standardized solution. This is, I’m convinced, the best one for bringing silent films to broader public.

So I haven’t given up hope that one of the manufacturers might realize that the Archival Frame Rates standard would be a nice addition to their option package. Particularly if archives and other potential buyers start asking for it.

Does one speed fit all?

The silent frame rates are more complicated than what I’ve just outlined. Let’s go a little deeper, because it’s interesting.

When we refer to frame rates, we tend to use discrete numbers (16, 18…). But like all things analog, frame rates lay along a continuum. That ranged from 16 (sometimes lower) to 24 (sometimes higher). Anybody who worked as a projectionist knows that even with a modern projector equipped with speed variators, the actual speed can change according to the day of the week and the time of the day, depending on fluctuations on the grid.

The same variations occurred, naturally, with hand-cranked projectors and cameras. And early motor-driven machines used in the silent era also suffered unpredictable variations from moment to moment.

As a result, silent films were shot and screened at different speeds. Even the same film would have fluctuations in frame rates from scene to scene or shot to shot.

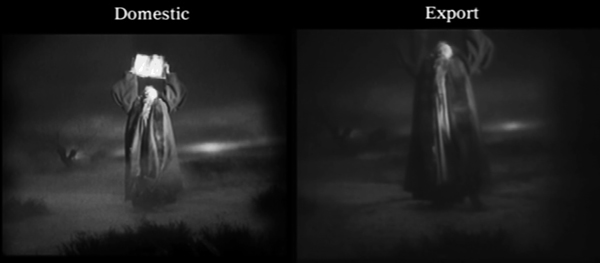

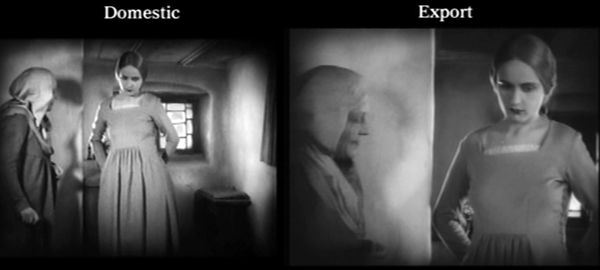

The best example I know personally is Murnau’s Faust (1926). When Luciano Berriatua and I were analyzing the existing negatives of the film, we were puzzled when we compared the two negatives from the original production. Each negative was shot with a different camera. As was common in silent film, the filmmakers provided one negative for domestic circulation and one for international distribution. In production the cameras yielded different angles on the scene–sometimes quite similar, sometimes different.

Nevertheless, the action each one captured was identical. The problem is that the two negatives were different in length!

Why? The cameras were operated by two different cameramen, each hand-cranking at a different speed. The assistant cameraman, undoubtedly younger and more enthusiastic, was cranking faster!

Such a disparity was not uncommon. On the contrary, any archivist confronted with the decision about “suggested frame rate” for a given film is confronted with a choice among many different frame rates. What one writes on the cans is always a speed that fits better on average, not necessarily on each individual shot or scene.

And the reality in archives, cinemathques and everywhere else, is this. Most silent film screenings, if not virtually all, are today executed at one speed throughout the whole picture,

There is strong, albeit anecdotal, evidence that projectionists in the silent era were encouraged to crank different sections of a movie at different speeds. Cues in some musical scores suggest that sequences may have been slowed or speeded up. Projectionists may also have chosen to accelerate chases and battles or slow down love scenes. But there’s no way to know to what extent this manipulation was a common practice.

Personally, I think that we are inevitably looking at a silent film with modern eyes. For one thing, we have a completely different approach to continuity. We ask that a restored silent film be perfectly graded, that its tinting and toning be consistent from shot to shot and scene to scene. But when we examine an original print, particularly from the ‘teens, we realize that our modern concept of pictorial continuity did not apply. It seems to have come into play in the late Twenties or later. Our assumptions about continuity make us consider narrative or visual discontinuity a technical error, or at least a trace of a more cavalier attitude towards continuity. I think that discontinuity of technique was often voluntary and sometimes deliberate.

Fun with frame rates

This point applies to frame rates as well. I am convinced that audiences in the silent era were much more relaxed towards something that we now consider so important. Otherwise, it’s difficult to understand why there so many variations in speed within one picture, and between different versions of the same film.

We should remember as well that we cannot really discuss anything “silent” without taking into consideration that it was a long and complex period of fast evolution and change. A film from the early ‘teens and one made ten years later are two different beasts, and different considerations should apply.

So, to return to our main theme: Are frame rates impossible to vary with a DCP? No—in theory.

If you decide to create your DCP at 24 fps, you can easily slow down each scene at a different rate, if you so choose. Alternatively, if the Archive Frame Rates standard were in use, you could apply your four fixed speeds (16. 18. 20. 22) to different sections of the DCP by simply creating separate “reels” and a correct playlist. This would be a bit like a DCP in which certain parts, such as the restoration credits, are actually a separate file to be played before or after the main body of the film.

Have I tried this? No. Could it work? Yes. Is it worth trying? I am not sure. Again, I am afraid we are looking for a precision that was not really part of a film screening in the silent era.

I remain strongly convinced that “old stuff,” including silent film, has an appeal for the public, and not just for few cinephiles. I also strongly believe that an archive like ours in Brussels should offer a wide range of films on DCP for screenings around the world.

In order to show a silent film in the present environment I have to do some nasty things to the images. I have to slow them down by means of software, even if some solutions work well enough to fool some archivists and historians.

If the alternative is never to show Maudite soit la guerre (Alfred Machin, 1910) to anybody, I’d rather use some tricks to make the screening possible in a modern DCP environment. That’s better than making the film invisible. I am also old enough to remember how horrible it was in the 35mm days when there was really no way to show silent films outside a cinematheque. While we wait for archives and manufacturers to implement the fuller range of options, we must keep our films alive.

So when today a nice audience shows up to see Maudite with a pianist in a multiplex in the middle of Flanders (or Ohio or Nebraska), I admit that I’d be unhappy that I had to trick the speed to 18 fps. Yet I still consider it a victory.

For discussion of silent-film frame rates the standard point of departure is Kevin Brownlow’s 1980 article, “Silent Films: What Was the Right Speed?” Brownlow suggests that many American silent films were intended to be screened at a higher rate than the cameraman had used during filming. See also James Card, Seductive Cinema: The Art of Silent Film (Knopf, 1994), 52-56, and Jon Marquis, “The Speed of Silence” (2011). On the revival of interest in high frame rates, see this 2011 article and Pandora’s Digital Box.

Nicola has written about other aspects of film preservation in the digital age. See his recent contribution to“The Last Picture Show,” a symposium in Artforum (October 2015), 288-291.Tacita Dean and Amy Taubin contribute to this as well.

The magnificent Masters of Cinema DVD set of Faust includes both the domestic German version and the export version, along with a lengthy comparison of them, from which I’ve drawn my illustrations.

Maudite soit la guerre (Alfred Machin, 1910).

Homunculus and his friends

Sappho (1921).

DB here:

Of the big-ass explosion movies, only two items in this summer’s spate of them have intrigued me. I liked Mad Max: Fury Road well enough, but not as much as MM2 and 3. I look forward to Mission: Impossible—Rogue Nation, in a series for which I have much affection. As for the arthouse releases, the ones I’ve already seen are A Pigeon Sat… (good but not as sardonically bizarre as earlier Andersson, methinks) and About Elly. That one is a masterpiece.

I have stronger reasons than indifference for missing so much, and for tardy blogging besides. I’ve been on my annual trip to Belgium for research and lecturing in the Summer Film College. As a result, your recent movie experiences and mine have been divergent, perhaps even insurgent.

Apart from two screenings in the Brussels Cinematek’s Hou series (their restoration of Green, Green Grass of Home, gorgeous vintage print of City of Sadness), I spent the last four weeks watching 35mm prints of movies by Godard, movies starring Burt Lancaster, and assorted silent films from the 1910s and 1920s. I also re-met one of the most charming directors I know of, and in general had a hell of a time.

Today’s entry focuses on my archive work. Next up, a report on the Summer Film College.

Conrad’s many moods, mostly unhappy

Landstrasse und Grosstadt.

The archive stuff was recherché. I’ve been trying to see as many 1910s and early 1920s features as I could, but this time around I didn’t catch anything as mind-bending as Jasset’s Au pays de ténébres (1911) or Doktor Satansohn (1916) or Fabiola (1919) or I.N.R.I (1920), encountered on earlier visits to the Cinematek. I did get further confirmation that in Germany the “tableau style” exploited so vigorously in Europe and somewhat in America in the 1910s, was pretty much replaced by Hollywood-style editing by 1920. And I got some welcome doses of Conrad Veidt, another favorite in this vicinity.

In Die Liebschaften des Hektor Dalmore (“The Liaisons of Hektor Dalmore,” 1921), Veidt plays a callous playboy who keeps on retainer a man who looks very much like him. It’s a lifestyle choice. When a compromised woman’s father demands that Hektor do the right thing, he sends out his double to marry her. Surprisingly, the double isn’t rendered through trick photography. Richard Oswald, always a fast man with a gimmick, found a pretty good Veidt lookalike, which can’t be easy to do.

The hero’s Casanova complex carries him from dalliance to dalliance, and as you’d expect in a twins situation, there are confusions between the real and the fake Hektor. Fights and abductions liven things up. The climax is a duel in which the real Hektor, overconfident, learns to his grief that an outraged husband is a better marksman. The scene is handled through brisk shot and reverse-shot, garnished with an over-the-shoulder shot as Hektor aims his pistol. And there are dashes of mildly Expressionist set design (furnished by Hans Dreier). Veidt in a phone booth does the décor proud. But he doesn’t need fancy sets to project a feeling: on his deathbed, his expression and his clutching fingers show a man bereft of erotic illusions.

The other Veidt vehicle lacked doubles but not ambition. Landstrasse und Grosstadt (“Village and City,” 1921) casts him as Raphael, a wandering violinist who teams up with Migal, an organ grinder. They become a popular act in the big city, and as Raphael’s playing improves, Migal becomes his manager. Nadia, a woman who joins them, falls for Raphael and shares his success. But in an accident he suffers a hand wound and his career slumps. Migal sees his chance to move in on Nadia. Perhaps this shot gives you a hint of his designs.

Actually, most of Landstrasse and Grosstadt isn’t as hammy as this. A very nice shot shows Raphael in silhouette approaching a mansion to hear his rival Cerlutti give a salon concert. And of course Conrad gives the blind violinist a delicate, spectral pathos, as shown above.

Artificial man lurks in the shadows, destroys humanity

Sappho.

All the films I saw broke down scenes into many close shots, reminding us that Caligari (released 1920) probably wasn’t typical of German staging or cutting of that moment. It now seems to me almost consciously anachronistic, rejecting the reverse angles and precise scene breakdown that were becoming common. In Die Ehe der Fürstin Demidoff (“The Marriage of Fürstin Demidoff,” 1921), when a governess drags a recalcitrant girl back to her bedroom, the action is split up into four shots, all of different scales from close-up to long-shot.

Although I saw a fragmentary print of Sappho (1921), it’s clear that in parts it has the audacious monumentality of a Joe May production. The most staggering shot is that of the Opera surmounting today’s entry, but there’s no shortage of striking images. Above I include a shot of a madman that, thanks to window reflections, suggests his split-up psyche.

Sappho also doesn’t shirk editing effects either. During a frantic automobile ride, there are glimpses of hands on a steering wheel, a foot on brakes, panicked passengers, and POV shots through the windshield. Forty-nine shots rush by in a flurry, anticipating similar sequences in French Impressionist films like L’Inhumaine (1924). Feuillade was experimenting with rapid cutting of action at about the same time.

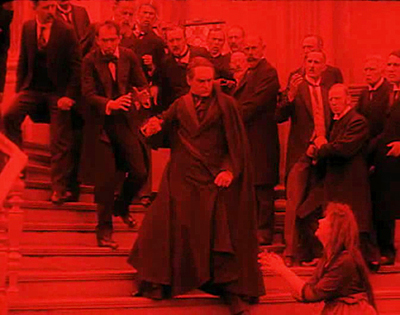

The most impressive, and nutty, film in this batch came from Homunculus, the largely lost German serial released through 1916 and into early 1917. The script was written by one of the blog’s favorite peculiar directors, Robert Reinert. The plot involves an artifical man created in the lab, à la Frankenstein’s monster. He’s a superman, in both strength and ambitions. The only surviving episode of the serial is Die Rache des Homunculus (“The Revenge of Homunculus,” 1916). (But see the codicil.) In this installment, posing as Professor Ortmann, Homunculus decides to drive humanity to destroy itself. He assumes a disguise to rouse the rabble, even inducing them to turn against himself in his Ortmann guise.

As in Expressionist drama, this overachiever is pitted against a crowd that, in the end, pursues him maniacally.

Director Otto Rippert gives us splendid mass effects in a quarry and along a beach, but there are also deep tableau images and sustained chiaroscuro, particularly in a showing the heroine Margot shrinking from Homunculus as he locks his rival in a dungeon.

Fans of Metropolis will notice that Rippert anticipates Lang’s unison choreography of crowds, as well suggesting that mob frenzy can create a sort of ecstasy in the woman who’s swept along.

In her book The Haunted Screen Lotte Eisner traces the films’ mass spectacle back to the stage work of Max Reinhardt and other theatre directors of the era. On the basis of this episode alone, Homunculus ranks with Algol and May’s Herrin der Welt as an example of big-scale fantasy in German silent cinema. Who needs Ant-Man when we have Homunculus?

Next time: Burt and Jean-Luc, together again for almost the first time.

Thanks to Nicola Mazzanti, Francis Malfliet, Bruno Mestdagh, and Vico de Vocht for their assistance during my visit to the Cinematek.

Kristin analyzes stylistic conventions of German cinema of this period in her Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (available for download here). She’s written on Caligari here and here.

A so-so copy of Sappho is on YouTube.

On Homunculus, Leonardo Querisima offers a wide-ranging discussion in “Homunculus: A Project for a Modern Cinema,” in A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decades, ed. Thomas Elsaesser and Michael Weidel, pp. 160-167. Substantial excerpts can be found here.

Munich archivist Stefan Drössler has recovered a mass of Homunculus footage and has assembled a version of the serial, which premiered last year in Bonn. Nitrateville has the story.

The Brussels Cinematek will release its Hou restorations on DVD early next year: Cute Girl, The Boys from Fengkui, and Green, Green Grass of Home. As a reminder, my video lecture on Hou is here.

The still below, taken as the prints were readied for the Summer Film College, points ahead to our next entry–number 701, as it turns out.