Archive for the '1910s cinema' Category

Addio Bologna 2014

Okoto and Sasuke (1935).

DB here:

Some final notes on this year’s Cinema Ritrovato. Kristin has more when I’ve finished.

Poland, very wide

The First Day of Freedom (1964); production still.

Revisiting a couple of the Polish widescreen classics Kristin mentioned earlier, I’d just add that The First Day of Freedom struck me as merging that heaviness often ascribed to Polish cinema with casual shock effects, as much visual as dramatic. It’s not just the opening shot, with the camera descending implacably to reveal layers of activity in a POW camp before settling on barbed wire in the foreground, made as big as the chains on an ocean liner’s anchor. A symmetrical vertical lift ends the film, rising through floors of a nearly destroyed church tower, revealing a half-shattered Madonna and a looming bell, to float back up to the sky.

As in Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds, gunfire not only cuts you down but sets you on fire. A Nazi dead-ender, holed up in the steeple and dying from his wounds, orders his girlfriend (“Whore!”) to take over his machine-gun nest. Since she’s been raped by wandering refugees early in the film, she has every reason to fire on the Poles, which she does with animal abandon. A Polish bullet cuts short her shooting spree, and then the camera launches on its remorseless movement heavenward. The primal force of this movie, especially the climax, suggests that Alexander Ford and Samuel Fuller have more in common than I’d suspected.

Kristin pointed out the efforts of Lenin in Poland (1965) to humanize the Great Man, and indeed there are many charming scenes showing him sliding down a banister, taking innocent walks with a Polish maiden, and generally being avuncular. But Sergei Yutkevich also doesn’t spare us the enraged Lenin, ranting in his cell when he learns of mistakes in party strategy. We also get a bit of the puritanical leader. He goes to the cinema for reportage on the political-military situation but walks out when a stupid melodrama comes on. To be fair, though, he does stick around to enjoy a comic short, Le cochon danseur (1907), with a lady cavorting with a man-sized pig. But the ex- (or maybe not so ex-) formalist Yutkevich recycles this image in a return to 1920s montage, when the pig shot reappears in a newsreel sequence showing the march to war.

Kristin pointed out the efforts of Lenin in Poland (1965) to humanize the Great Man, and indeed there are many charming scenes showing him sliding down a banister, taking innocent walks with a Polish maiden, and generally being avuncular. But Sergei Yutkevich also doesn’t spare us the enraged Lenin, ranting in his cell when he learns of mistakes in party strategy. We also get a bit of the puritanical leader. He goes to the cinema for reportage on the political-military situation but walks out when a stupid melodrama comes on. To be fair, though, he does stick around to enjoy a comic short, Le cochon danseur (1907), with a lady cavorting with a man-sized pig. But the ex- (or maybe not so ex-) formalist Yutkevich recycles this image in a return to 1920s montage, when the pig shot reappears in a newsreel sequence showing the march to war.

Yutkevich seems to be keeping up with the Young Cinemas of his day. The film is plotted as a series of flashbacks, alternating the present (Lenin in prison) with pieces of the past, sometimes out of chronological order. He imagines himself striding across a battlefield, conveyed by him walking in place against a blatant back-projection. Late in the film, newsreel footage gets stretched and distorted to fill the ‘Scope format, as in Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1962). The experimentation with the soundtrack seems likewise rather modern. The noises are filtered nearly as strictly as in Miguel Gomes’ Tabu, so that sometimes we hear only Lenin’s footsteps in a city street.

Lenin not only narrates the film but “quotes” the whole dialogue of the scenes; we never hear any voice but his. Reminiscent of passages of The Power and the Glory (1933) and the entirety of Guitry’s Roman d’un Tricheur (1936), this device blankets the movie with Lenin’s thoughts, feelings, and political analyses. It’s scarily evocative of that booming voice-over narrator that Soviet cinema imposed on imported films. Denied subtitles and dubbing, audiences were obliged to listen to an impersonal voice drowning out the actors with its sovereign interpretation of the action. I wouldn’t put it past Yutkevich to be slyly alluding to this Orwellian voice of authority.

1914 fashionistas and 1940s fakers

Maison Fifi (1914).

For sheer dirty fun I have to recommend Maison Fifi by Viggo Larsen, a Danish director working in Germany. Here situation comedy meets notably horizontal sight gags. A young couturier cozies up to the officers stationed in her town, hoping that their wives will buy her wares. Her first encounter takes place outside the officers’ quarters, as each man, from private up to general, spots her and starts to flirt before being ordered aside by a higher-up. Part of the humor comes from the strict adherence to the table of ranks, part from the fact that each dislodged officer enjoys watching his superior get taken down.

Later, on a lark, some officers swipe one of Fifi’s dummies and take it to a tavern. When their wives surprise them there, they stow the mannequin in a distant phone booth. As they expostulate with their wives in the foreground, the dummy sits unmoving in the window of the booth far on frame right. Meanwhile, increasingly annoyed customers line up outside the booth. The dummy is more visible in projection than in my still, but Larsen also obliges with a cut-in.

In a very logical reversal, Fifi is at the climax caught in a boudoir and must pretend to be one of her own mannequins. This affords the officers an excellent pretext to undress her. Today the scene yields a vivid sense of the hooks, buttons, and stays that women, and men, of 1914 had to contend with.

Faked identity was a motif of the festival’s Hitler strand. The Strange Death of Adolf Hitler (1943) centers on a man with a knack for mimicking his Fuhrer and accidentally becomes his double. In a series of twists, both he and others try to kill the original, but confusion ensues and leads to a very downbeat ending.

The same premise gets a different workout in The Magic Face (1951), a film as puzzling as its title. Luther Adler delivers a performance at once peculiar and virtuoso. A stage impersonator’s wife is stolen away from him by Hitler. Escaping from prison, he decides to get his vengeance by posing as a servant and gaining access to the dictator. He kills Hitler and takes over his identity. Thereafter he cunningly fouls up the prosecution of the war by an ill-timed invasion of Russia, etc. His general staff are baffled and even try to kill him, but he represses all resistance.

The weirdness of this speaks for itself. In addition, the film doesn’t explain how Hitler’s new mistress fails to realize that her paramour has been replaced by her husband. Perhaps more striking, we wonder whether the impersonator might have taken a little trouble to alter other Nazi policies, e.g., the Final Solution. No less odd is the frame story, narrated by celebrated war correspondent William L. Shirer. There he maintains that this account was relayed to him by the wayward wife, who survived the fire in Hitler’s bunker. An independent production directed by Frank Tuttle (recently under HUAC pressure for his Communist affiliations), The Magic Face was judged by Variety to provide “a dramatic and suspenseful story which would have had far greater audience impact five or more years ago.”

Talking, in and out of sleep

The Bride Talks in Her Sleep (Hanayome no negoto, 1933); production still.

The Japanese cinema of the 1930s through the 1960s has been one of the very greatest national film traditions. I once characterized it as the Western cinephile’s dream cinema: a relentlessly commercial industry that has given us dozens of indisputable masterworks. Yet it seems that every few years it’s necessary to remind western publics of this nation’s titanic accomplishments. Packages circulated by the Japan Film Library Council in the 1970s have been followed by retrospectives and one-off touring programs at rather long intervals; the Mizoguchi series is a recent example.

Another effort to draw Japanese cinema to the spotlight, “Japan Speaks Out!” has become a high point of Cinema Ritrovato over the last three years. Curators Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström deserve credit for assembling new prints of early talkies, grouped by studio. As in previous years, some of the titles were familiar to specialists, and a few to generalists (Ozu’s The Only Son being this year’s example). But there have been several new discoveries, and the Ritrovato audience has responded enthusiastically. This year the films were screened twice, often to jam-packed halls. The sessions were introduced with brevity and point by Alexander, Johan, and Tochigi Akira of the National Film Center of Tokyo.

This year’s batch focused on the Shochiku studio, more or less the MGM of Japan. Shochiku enjoyed financial stability because of its theatre holdings (both cinemas and live-performance venues) and its address to a modernizing, western-leaning urban audience. Its policies, overseen by Kido Shiro, aimed to provide movies mixing tears and laughter. Kido urged that Shochiku comedy have a melancholy cast, and that Shochiku melodrama indulge in lighter moments. This blend is familiar to us in Ozu’s 1930s works; even as sad a film as The Only Son displays a comic side when the mother falls asleep during a German talkie.

Perhaps the purest example of Kido-ism in this year’s package was one of Shimazu Yasujiro’s best films, Our Neighbor Miss Yae (Tonari no Yae-chan, 1934). Two brothers are introduced practicing baseball, and soon we learn that one has considerable affection for the girl next door. The neighboring families are thrown into quiet turmoil when Yaeko’s sister returns home, having left her husband.

Stylistically, Shimazu is less rigorous than either Ozu or Shimizu Hiroshi, but he is very skilful. Our Neighbor Miss Yae has the real Kido flavor, mixing comedy and drama and throwing in cinephile references that the studio’s young directors enjoyed: one boy is compared to Fredric March, the young people watch a cartoon featuring Betty Boop and Koko the Clown. Just as important, Shimazu enjoys throwing in a stylistic flourish every now and again–a striking, even eccentric shot that arrests our attention. As the four young people are eating in a restaurant, a very straightforward shot of them gives way to a bold composition full of peekaboo apertures. The shot enlivens the fairly routine act of waitresses delivering food; at the end, one pair stands and switches positions.

Not all Shochiku films displayed a mixed tone; we saw some fairly pure comedies and melodramas. Three self-consciously modern films showed an amused, slightly sexy concern with young marriage. Happy Times (Ureshii koro, 1933) by Nomura Hiromasa, begins with a pair of teenage boys practicing pitching and catching to the strains of “There’s No Place Like Home.” Soon they’re spying on newlyweds who are so infatuated with one another that the husband skips work to stay at home and lounge around. He’s mocked by his fellow employees and upbraided by his boss, but his wife is relentless in her sweet-talking ways. The marital bliss is disrupted by an obstreperous visiting uncle, and the couple must turn to one of the man’s old girlfriends, a tough singing teacher, to dislodge him—without sacrificing the inheritance he may leave them. Awkwardly shot and rather too prolonged, the film exemplified how loose-limbed Shochiku comedy could get.

A brace of films by Shochiku stalwart Gosho Heinosuke, The Bride Talks in Her Sleep (1935) and The Groom Talks in His Sleep (Hanamuko no negoto, 1935), showed other newlyweds with comic problems. Again the motif of spying plays a role. (Naughty voyeurism was essential to that strain in popular culture called Ero-guru-nansensu, “erotic-grotesque nonsense.”) Salaryman Komura’s pals have learned that his wife talks in her sleep, and so they drop by to hear for themselves. Unfortunately they drink so much that they fall asleep and miss the big revelation. Plot complications include a burglar, the couple’s decision to sleep elsewhere, and the revelation of what keeps the bride “sleep-talking.”

Only a little less slight is The Groom Talks in His Sleep. Here the title probably gives away too much, because the initial puzzle is why the young wife naps during the day. This scandalous dereliction of housewifely duty leads eventually to a demand for divorce until the cause, the husband’s sleep-talking that keeps her awake all night, is revealed. The family brings in a self-styled hypnotist, played with relish by Ozu regular Saito Tatsuo, to cure the groom.

Gosho is said to be the fastest cutter among classic Japanese directors, but I’m not sure that he goes much beyond what was fairly standard at Shochiku. Most of the studio’s directors working in the contemporary-life genre (gendai-geki) employed what I called in my book on Ozu “piecemeal découpage,” a breakdown of action and dialogue akin to that seen in late US silent films. What Gosho does have in abundance is different camera positions. In The Bride, our introduction to Komura’s drinking buddies takes place at a bar, and I didn’t spot any repeated setups. Throughout the two films, each composition is calibrated to a specific item of information—a line of dialogue, a reaction shot, or a change in the staging. This makes for a tidy visual texture, which is an advantage in the rather loose plotting that’s characteristic of Shochiku comedy (Ozu, always, excepted).

At the other extreme were some very serious drama, such as Mizoguchi’s relatively well-known Poppies (Gubinjinso, 1935) and the more obscure Mizoguchi-supervised Ojo Okichi (1935). There was as well Okoto and Sasuke (Shunkinsho: Okoto to Sasuke, 1935), another Shimazu work. It’s based on a Tanizaki Junichiro tale of male devotion passing into love and masochism. Okoto is blind, but her family can afford to pamper her. She takes up the koto and the family’s young servant Sasuke faithfully escorts her to her music lessons. She often treats him disdainfully, but she insists on his company, and so gossip grows up around them. Sasuke’s loyalty is tested when Okoto is wooed by a vacuous but persistent suitor. Spurned, he arranges an attack on her, which triggers Sasuke’s ultimate sacrifice.

Shimazu treats this story with a calmness that builds up tension between the often wilful Okoto and the simple-hearted Sasuke. The discreet simplicity of the film’s technique, excepting the violent climax, can be seen in an almost throwaway moment. Sasuke as been assigned to tutor two of Okoto’s students, and they laugh at his efforts. As they rise, Shimazu cuts to a new angle, putting them the background and showing Okoto is shown growing anxious in the foreground.

Keeping Sasuke out of focus and far back allows Shimazu to stress a micro-movement in the foreground: Okoto’s shift from sympathy for Sasuke to her usual imperious annoyance. After unfolding her hands, she clenches her right hand and softly strikes it on the edge of the brazier.

As Okoto turns to summon him for a mild dressing-down, still keeping her little fist extended, Sasuke has shifted his position slightly so that he is a more active responder to her.

This sort of directorial discretion, so characteristic of classic Japanese cinema, seems today to come from another world.

Probably the greatest revelation of the Shochiku show was another masterwork by the ever-more-impressive Shimizu Hiroshi. A Woman Crying in Spring (Nakinureta haru no onna yo, 1933), Shimizu’s first sound film, was given its western premier. It was chosen to exemplify his experiments with sound–experiments that induced Ozu to try his own hand at talkies.

Mining work in Hokkaido brings day laborers by ship, along with women who wind up serving them drinks and perhaps something more. Most of the action takes place in a tavern with a bar downstairs, women’s rooms on the next story, and a small upstairs where the mysterious, somewhat cynical Chuko keeps her daughter. Kenji and his boss become rivals for Chuko, and a young woman drawn into prostitution further complicates the situation.

After only a single viewing, I’m pressed to say much more than noting that Shimizu sacrifices some of his geometrical precision (discussed here) to a more naturalistic treatment of the bar’s space and more experiments with chiaroscuro lighting. A somewhat flamboyant scene, in which our view of a fistfight is mostly blocked by a high wall, shows how Shimazu was trying to let sound do duty for the image. The title has multiple implications: the woman we see crying at the outset is Fuji, the girl initiated into the trade; but at the end, Chuko is weeping. Moreover, as Alexander Jacoby pointed out, the scenes we see are all set in winter, although the ending suggests that the couple that is created will find spring elsewhere. Long unavailable in its Japanese VHS edition, A Woman Crying in Spring is ripe for Western distribution.

Last notes from Kristin

Despite my commitment to the Polish, Indian, and Japanese threads, I was able to fit in a film or selection of shorts now and then.

On the afternoon of the opening day, the first “Cento Anni Fa” program for 1914 included a couple of interesting items. One was La guerre du feu, a French film directed by George Deonola. It dealt with a tribe of fur-clad cavemen who have captured fire but lack the knowledge to create it themselves. Thus they must tend their fire constantly and protect it from a rival tribe. In the course of the action the hero learns the secret to using tinder and flint to generate a blaze. This, it has to be said, was more interesting as an historical curiosity than as entertainment.

Not so the final film of this group, Amor di Regina (Guido Volante, 1913). Its unusual story dealt with a queen of an unnamed country who is having a secret affair with a young soldier. When the latter gets wind of a rebellious group’s plans to assassinate the king, the hero and the queen manage to spirit him out of the palace and away to exile. It struck me that in a more conventional film, the lovers would use the assassination of the king to allow them to marry. Instead they take care of the king in exile and watch for a chance to reinstate him.

Stylistically there were some impressive shots. In one, we see a close-up of the back of the hero’s head, looking out from a terrace at a group of conspirators in the distance sneaking toward the palace, and the camera racks focus from him to them–for 1913, a highly unusual way to handle a very deep composition. If anyone is contemplating a DVD/BD release of some Italian short features of this era, Amor di Regina would be a good choice.

Another 1914 program included the lovely La fille de Delft, which, along with Maudite soit la guerre (which was shown at one of the Piazza Maggiore screenings), is one of Alfred Machin’s best-known films. Its plot concerns a little country boy and girl who are dear friends; a variety-theater owner sees them dancing at a country celebration and takes the girl off to the city to become a star. Seeing it again, I was struck at how marvelously natural the performances of the two child actors (above) was, something that goes a long way to making this film so very affecting.

Despite the fact that all of Tati’s early short films are on the new French boxed Blu-ray set, I decided to see the Tati program on the big screen. Seen again, Gai dimanche (1935) seemed a bit labored in its humor, dealing with two layabouts who hire an old car and persuade several people to purchase day trips to the country. The situation seems more the sort of thing that René Clair could have made work, but director Jacques Berr makes it somewhat leaden.

Soigne ton gauche centers on a gawky farmhand who is mistaken for a boxer by a promoter and ends up in a practice ring with a tough opponent. Tati creates a very Keatonesque situation as the naive young man finds a book on boxing on his stool and proceeds to consult it at intervals (below). As he assumes classic boxing poses, the experienced boxer uses brute force to knock him silly.

The opening and closing of Soigne ton gauche contains a comic, bicycle-riding postman, and clearly Tati recognized the comic potential of the character. In his first directorial effort, L’école des facteurs (School for Postmen, 1946), Tati himself played the postman François, who tries to please his teacher by finding ways to deliver the mail more swiftly. The idea proved so fruitful that the film was remade as Tati’s first feature, Jour de fête. The bouncy music and many of the gags were retained, and the longer film’s success established Tati as a major director and star.

To all our friends and the coordinators of Cinema Ritrovato: Thanks for another wonderful year!

You can watch The Eye’s tinted copy of Maison Fifi here.

Miriam Silverberg’s Erotic Grotesque Nonsense offers a thorough discussion of Japanese popular culture of the 1930s. For more on Kido Shiro’s influence on Kamata cinema, see Mark Schilling’s Kindle book Shiro Kido: Cinema Shogun. I discuss trends in 1930s Japanese film style in Chapters 12 and 13 of Poetics of Cinema. For more on the restoration of Machin’s films, see our entry here.

Soigne ton gauche (1936).

Il Cinema Ritrovato, number 9 and counting

Kristin here:

For a second year running I unexpectedly ended up attending Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna alone. (For the 2012 report, see here.) Last year David’s back went out shortly before we were due to leave. This year an exceptionally long stretch of days with heavy thunderstorms resulted in flooding in our basement (where many of our books reside). I had already been in London for nearly three weeks and was planning to meet David in Bologna. Instead, he valiantly stayed home to deal with the unwanted water, and I went on to the expanding smorgasbord of films presented by the festival.

The programmers are limited to their existing venues: the relatively small Mastroianni and Scorsese auditoriums in the Cineteca’s building, the larger Arlecchino and Jolly commercial cinemas, and the vast space of the Piazza Maggiore for the nightly open-air screenings starting at 10 pm. This year for the first time, to accommodate the many films, post-dinner screenings, starting at 9:30, 9:45, or 10 pm, were scheduled in the Scorsese and Mastroianni.

Faced with so many options, one could only focus on a few of the bounteous threads of programming. I opted to see as many of the early Japanese sound films as possible, the early (pre-mid-1960s) Chris Marker works, and the annual Cento Anni Fa series, this year presenting a sampling of films from 1913, the year when worldwide the cinema seemed to take an extraordinary leap forward in complexity and inventiveness. Whenever there was a gap, I could fit in items from the other threads: European widescreen movies; cinema of the 1930s that presaged the coming war; a retrospective of the work of Soviet director Olga Preobrezhenskaja, another devoted to Vittorio de Sica, primarily as an actor, more Chaplin restorations from the Cineteca’s ongoing project, the newly restored Hitchcock silents, and of course various other newly restored films. A tradition of highlighting the work of a Hollywood director has become a centerpiece of Il Cinema Ritrovato, with the subject this year being Allan Dwan.

Japanese Talkies, Part 2

Last year I caught only a few of the films in the retrospective of early Japanese sound films. I regretted not being able to see more, but the Ivan Pyriev and Jean Grémillon threads lured me away. This year the rival was Chris Marker, but I determined that by careful planning, I could fit almost everything in both retrospectives into my schedule. These became my top priorities.

The Japanese series is ongoing and organized not by auteurs but by film companies. The programmers were again Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström, whose encyclopedic knowledge of the history of Japanese studios of the 1930s made  for fascinating introductions. This year it was PCL and the very obscure company JO, both of which made American-style musicals in the early and mid-1930s. These were not the best films in the season, but they were highly entertaining. This series also had the advantage of being presented entirely in 35mm and with English subtitles devised years ago for traveling retrospectives.

for fascinating introductions. This year it was PCL and the very obscure company JO, both of which made American-style musicals in the early and mid-1930s. These were not the best films in the season, but they were highly entertaining. This series also had the advantage of being presented entirely in 35mm and with English subtitles devised years ago for traveling retrospectives.

I had seen only one of the films in the series, Mikio Naruse’s 1935 masterpiece, Wife, Be like a Rose. I didn’t remember much about it, except that it was marvelous, and it proved so on second viewing. Naruse often has been compared with Ozu, both during his active career and since. Overall, he seems to me not as great a filmmaker, but Wife, Be like a Rose must be among his best films and would undoubtedly rank alongside some of Ozu’s work of this period. A moga (modern girl) is upset that her father has deserted his family in Tokyo and established another family in the countryside. Determined to drag him back to his familial responsibilities, the daughter confronts the possibility that he was right in leaving her mother. The film is shot in a somewhat Ozu-like style, with low camera heights and across-the-line shot/reverse shots. Still, there is no slavish imitation (the climax is filled with camera movements), and Naruse’s film is both moving and stylistically engaging.

Naruse was the only director with two films in the retrospective. His Five Men in the Circus, also released in 1935, was a less ambitious work than Wife, Be like a Rose, but it was an entertaining story of musicians on the road earning a living during the Depression, encountering disappointments in work and love.

Naruse has already gained a modern reputation in the West, but for some the discovery of the season was Sotoji Kimura, whose Ino and Mon was well received. As with so many of this thread’s films, its subject was a modern girl struggling with tradition. Mon, who has become pregnant and doesn’t want to marry her child’s father, returns to her country home and faces sullen opposition from her much beloved but fiercely traditional brother Ino. Aside from its realistic depiction of the countryside, the film is notable for its Soviet-style scenes of work on a nearby construction project supervised by the siblings’ father (left).

Naruse has already gained a modern reputation in the West, but for some the discovery of the season was Sotoji Kimura, whose Ino and Mon was well received. As with so many of this thread’s films, its subject was a modern girl struggling with tradition. Mon, who has become pregnant and doesn’t want to marry her child’s father, returns to her country home and faces sullen opposition from her much beloved but fiercely traditional brother Ino. Aside from its realistic depiction of the countryside, the film is notable for its Soviet-style scenes of work on a nearby construction project supervised by the siblings’ father (left).

The Japanese musicals were all charming films. Romantic and Crazy (1934) starred the popular comic performer Kenichi Enomoto, better known as Enoken. (In the West, he is most familiar from his comic role in Akira Kurosawa’s third feature, The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail [1945].) Romantic and Crazy is basically a college musical imitating the early 1930s films of Eddie Cantor–and at  moments I wished I were watching an Eddie Cantor musical. The other two musicals–Tipsy Life (Sotoji Kimura, 1933) and Chorus of One Million Voices (Atsuo Tomioka, 1935)–were quite entertaining. Clearly the filmmakers felt no compunction about stealing recent American songs and setting the tunes to new Japanese lyrics. The most popular seemed to be “Yes, Yes, My Honey said Yes, Yes!” as sung by Cantor in the 1931 musical Palmy Days; the tune was heard in at least two of the films.

moments I wished I were watching an Eddie Cantor musical. The other two musicals–Tipsy Life (Sotoji Kimura, 1933) and Chorus of One Million Voices (Atsuo Tomioka, 1935)–were quite entertaining. Clearly the filmmakers felt no compunction about stealing recent American songs and setting the tunes to new Japanese lyrics. The most popular seemed to be “Yes, Yes, My Honey said Yes, Yes!” as sung by Cantor in the 1931 musical Palmy Days; the tune was heard in at least two of the films.

Another notable film was Sadao Yamanaka’s Kôchiyama Sôshun (1936), one of his three surviving feature films. (These and fragments of others are available on a new set from Eureka! in its “Masters of Cinema” series.) It’s a strange film, partly comic but mostly a crime story. An attractive woman, played by a very young Setsuko Hara, keeps a shop owned by a local gangster, and tries to prevent her thuggish younger brother from becoming a criminal. The title character, Kôchiyama Sôshun, appears to be an idler getting by on the income from his wife’s gambling house, but he apparently has unlimited sources of money. Despite his shady background, Kôchiyama tries to help save the heroine when, after her brother has gambled away the house and shop, she is forced to sell herself into prostitution.

The seasons of early Japanese sound films will continue during the 2014 Il Cinema Ritrovato, with a focus on Shochiku.

Chris Marker’s youth returns

It has been difficult to see any of Chris Marker’s early films lately. By early I don’t mean early 1950s, but essentially anything made before La jetée (1962). As Florence Dauman of Argos Films explained in an introduction to one of the programs, Marker thought of the films made during his first decade as a director as mere trials and didn’t want them seen again. Fortunately Dauman and others made the decision not to honor his wishes. Perhaps Marker thought that his later films, more complex and philosophical (Sans soleil comes to mind), were how he wanted to be remembered. But the playful, emotional, politically committed film essays of the 1950s and early 1960s are precious and not to be abandoned. We were treated to excellent restored prints of them during the festival.

The only film that made me understand Marker’s reluctance to show his early work was Olympia 52 (1952), a documentary on the Olympic Games in Helsinki. It was Marker’s first professional feature, and it is barely competent. The coverage sticks almost entirely to the track and field events, with endless 100-meter dashes, shot-puts, hurdles, high jumps, pole-vaults, and so on. The several cameras filming the events rendered very different footage, ranging from excellent to dark gray. Cut together, these shifting images look amateurish. A brief series of shots of yacht-racing, equine-jumping, and other sports leads back to more shot-puts, hurdles, pole-vaults, and so on. Valuable practice for Marker, no doubt, but a film which bears no hint of the talent soon to burst forth.

It was wonderful to see Letter from Siberia (1958) again after so many years. David and I had taught it in an introductory class in the mid-1970s. Its repeated series of shots of a bus on a street and some men doing construction work has been an example of the powers of the sound track from the very first edition of Film Art in 1979 to the present one.

There were no subtitles on the prints, and the headphone translation could never keep up with the rapid, contemplative voice that accompanied these images, so I missed much of the point of Dimanche à Pékin (1956) and Description d’un Combat (1960). Marker’s written contribution to Joris Ivens’ documentary …À Valparaiso (1963) presaged much of his later work. His 16mm documentation of American hippies’ gently protesting assault on the Pentagon in La sixiéme face du Pentagone (1968) made me proud to be an American (something not too easy in the light of recent events).

Dwan at his peak? The 1920s

I missed most of the Dwan films, but I managed to fit in three of the four from the 1920s. These did not include the 1923 Gloria Swanson vehicle Zaza, alas, though I heard good things about it from friends who saw it. The three I caught seemed to represent Dwan at the height of his career.

I had seen the other Swanson film, Manhandled (1924) before, but it was a treat to see it again. It’s a strange mixture of realism–most notably in the famous early scene of the working-class heroine’s commute home on a crowded subway–and an absurdly melodramatic plot in which she manages to attain the pampered stature of a kept woman while maintaining her virtue. Swanson is a delight, and the fact that the film is incomplete, missing a scene in which she demonstrates her talent for mimicry by imitating various characters, including Charlie Chaplin, is a true pity. We can only hope that a complete version will someday surface.

Dwan’s 1927 melodrama, East Side, West Side, was a considerable surprise. For a director who has a reputation for making B picture in the sound era, this high-budget production seemed remarkable. The production design and cinematography were excellent, and a ship accident scene done with models was unusually convincing. The print was a fine restoration by the Museum of Modern Art. The Iron Mask (1929, above) was introduced by Kevin Brownlow (right), who had helped supervise the restoration.

Dwan’s 1927 melodrama, East Side, West Side, was a considerable surprise. For a director who has a reputation for making B picture in the sound era, this high-budget production seemed remarkable. The production design and cinematography were excellent, and a ship accident scene done with models was unusually convincing. The print was a fine restoration by the Museum of Modern Art. The Iron Mask (1929, above) was introduced by Kevin Brownlow (right), who had helped supervise the restoration.

As always it was a treat to hear anecdotes from the man who had the inspired idea of interviewing stars and filmmakers from the silent era before it was too late. The Iron Mask was another impressive print, dated 1999 and bearing a Carl Davis score. I much prefer Douglas Fairbanks in his early comedies to his more famous swashbuckler films, and the story and staging in this one seemed very by-the-numbers, especially in comparison to the more imaginative East Side, West Side. Its main interest, and that was considerable, lay in the impressive sets designed by Ben Carré and William Cameron Menzies and its glowing cinematography by Henry Sharp.

By the end of the week, I was happy to have caught these particular Dwan films. From conversations with people who followed his thread more closely, I gathered that they thought the 1920s titles were the best of those shown in Bologna.

Glimpses of 1913

There was a time when the Cento Anni Fa series, programmed by Mariann Lewinsky, was a must-see for me. With the proliferation of screenings, however, seeing all of the sessions has become difficult, and I found myself ducking in and out to catch a few items now and then. I wanted to see the new restoration of Mario Caserini’s remarkable feature, Ma l’amor mio non muore!, but there was something else I wanted to see playing opposite both screenings. Luckily the Cineteca has put the film out on DVD. The catalog claims that it’s the first diva film. It stars Lyda Borelli in a spectacular performance, plus it has many complex examples of what David calls tableau staging (see here), especially in the amazing set in the frame above. One of the must-see films of 1913.

I am not a great fan of Italian (or any other) spectacles set in ancient times, and there were quite a few included in the series. They also tend to be rather long, which makes it more difficult to fit them into a packed schedule. Still, I did like Spartaco ovvero il gladiatore della Tracia (Giovani Enrico Vidali). Its minor actors and extras avoided giving the usual impression of people milling around in sets; they actually behaved as if they were living in real places in antiquity. The actress playing Emilia (not listed in the catalog) gave an engaging performance, quite the opposite of the diva approach, though Mario Guaita as Spartaco depended largely on rolling his eyes upward at frequent intervals to convey suffering. As Ivo Blom points out in his program notes, however, Guaita turns out to be the the first strongman figure, bending iron bars with his hands a year before Bartolomeo Pagano supposedly innovated this iconic gesture as Maciste in Cabiria.

More than that film, though, I was impressed by Luigi Maggi’s La lampada della nonna. It begins with an old woman knitting beside an oil lamp. When her grandchildren try to present her with a new electric one, she objects. The bulk of the film is an extended flashback set in the era of the Risorgimento, with the heroine in her youth helping to shelter a wounded officer and falling in love with them. The lamp, seen unobtrusively in the background of several shots, comes to play a key role as a signal in the climactic scene. Again there is an unusual degree of naturalness in the acting, with the extras in the military campground scene, for example, all given bits of plausible action to collectively present the impression of an actual campground. The flashback structure, framing, staging, and acting all reminded me strongly of Griffith at the same period.

There were slight but charming films like Léonce et Toto, a very funny Léonce Perret comedy (director unknown, but probably Perret). Léonce’s wife receives a tiny chihuahua as a gift and immediately dotes on it, to the point of putting it on the table at meals. The hero is disgusted and tries increasingly devious and extreme ways of getting rid of the little pest. Another was an American documentary with the irresistible title Aquatic Elephants. Who would not delight in five minutes of elephants rolling cheerfully in a pond while silly men try to stand on them and invariably fall into the water?

DVDs and Blu-ray

Just about every film scholar and buff in the world probably knows the Criterion Collection. As a brand, it’s sort of the Pixar of high-end home-video. We all have at least some of its releases on our shelves, whether lined up alphabetically or by director or by number. This year a session was devoted to the background of the company, with guests Jonathan Turell and Peter Becker (left and right, above). The history of Criterion is a bit complicated. Briefly, it was founded in 1984 to release laserdiscs and eventually, after the introduction of DVDs in 1997, switched to that format, eventually adding Blu-ray discs. Becker joined the company in 1993.

Criterion is closely linked to the historically important Janus Films, founded in 1956 and responsible for distributing many of the most famous art films of subsequent decades. In 1966 it was acquired by Saul J. Turell and William Becker, the fathers of the two speakers. Their sons are now co-owners of the Criterion Collection, of which Peter is the president; Jonathan is director of Janus.

To David’s and my generation of film students, Janus was a key player in our discovery of art cinema. How many of us, I wonder, first watched many of the classics that now grace Criterion DVDs through the landmark PBS series, “Film Odyssey,” in 1972? I first saw and was bowled over by Ivan the Terrible in that series. Three years later, when I was working on my dissertation on the film, I called Janus and got through to Saul Turell. Could I possibly borrow 35mm prints of the two parts of the film, I asked, explaining that I needed and to take frames from good copies. He gave me the name and phone number of a person in the company’s storage facility to call, and she arranged to ship the prints to me. I was able to spend weeks in front of a Steenbeck in the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, wallowing in strange, beautiful images and sounds. Nearly all the illustrations in my book, Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, were taken from those prints.

That same spirit of cooperation with academic film studies has lived on. David and I are grateful for our friendly relationship with the Criterion team, who have cooperated in our creation of video-based online examples tied to Film Art: An Introduction. (The examples all come from Janus films; a sample analysis of a clip from Vagabond is available on YouTube.)

The pair’s presentation included a video, The Criterion Collection in 2.5 Minutes. It features over 600 clips from the collection as of September 1, 2012, chosen and edited by Jonathan Keogh, clearly one of the company’s most devoted fans. Although cut too fast too allow the viewer to identify every title (and I must admit, I don’t think I could recognize every single one, even with longer excerpts), it’s an exhilarating paean to great cinema.

The plaudits in the festival’s annual DVD contest were spread, deliberately or not, among many DVD/Blu-ray companies, with none winning more than one award. A number of items that we’ve covered here took home awards: Flicker Alley’s collection of films by the Russian firm in Paris, Albatros, was deemed the best boxed-set of silent films; and Edition Filmmuseum’s set of four Asta Nielsen films shared the award for best rediscovery. Our friends at the Belgian Cinematek won best Blu-ray boxed set for the “Henri Storck Collection.” Criterion took home best Blu-ray for its edition of Paul Fejos’s Lonesome. For these and the other winners of this year’s DVD awards, see Jonathan Rosenbaum’s website. (As one of the jurors, he explains the changes in the award categories this year.)

The Return of Carbon Arcs

I’m old enough to remember when carbon-arc projectors were the norm. Gradually xenon lamps replaced them, starting in 1956. This year, the festival put on two outdoor screenings in the courtyard of the Cineteca’s building. These started at 10 pm, so they competed with the bigger shows in the Piazza Maggiore. I usually don’t go to the Piazza screenings, since they tend to end late, and I don’t want to fall asleep during the 9 am screenings the next day. But the two programs, billed as “Il Cinema ambulante Ritrovato. Tesori dal Fondo Morieux,” were considerably shorter, so I attended the first one. As the name suggests, the idea was to simulate a traveling cinema of the early era. The first screenings included one Pathé film from 1904 and five others from 1906, some with hand-stenciled color. All six were rediscovered titles.

I’m old enough to remember when carbon-arc projectors were the norm. Gradually xenon lamps replaced them, starting in 1956. This year, the festival put on two outdoor screenings in the courtyard of the Cineteca’s building. These started at 10 pm, so they competed with the bigger shows in the Piazza Maggiore. I usually don’t go to the Piazza screenings, since they tend to end late, and I don’t want to fall asleep during the 9 am screenings the next day. But the two programs, billed as “Il Cinema ambulante Ritrovato. Tesori dal Fondo Morieux,” were considerably shorter, so I attended the first one. As the name suggests, the idea was to simulate a traveling cinema of the early era. The first screenings included one Pathé film from 1904 and five others from 1906, some with hand-stenciled color. All six were rediscovered titles.

They came from the remarkable 2006 find of a wealth of films, equipment, posters, and even sets and puppets, in a warehouse in Belgium. The collection all originated from the stock of the traveling Théâtre Morieux, which had started with puppet and magic-lantern programs, adding films in 1906. All this material had been in the warehouse for a century and was in good condition.

The projector used for the program was not from 1906, but it was old, and very heavy. I happened to be between films when a truck with a crane delivered the projector and a generator and a team set up the equipment facing a small screen on one side of the courtyard. (At the very top of today’s entry, the crane lowers the projector body onto its platform. Above, festival coordinator Guy Borlée watches as the lamp housing is attached. Bottom, all ready to go and waiting for the sun to set.) The projector was a Prevost, of French manufacture, I would guess from the 1940s.

When 10 pm arrived, it became apparent that the light from buildings near the Cineteca could not be entirely controlled. Shadows of the trees in the courtyard were cast on the screen, with light patches between them. But traveling cinemas no doubt frequently set up in venues where nearby sounds and other distractions abounded, so we all accepted the light pollution as part of the experience.

Perhaps the most memorable of the films was Cambrioleurs modernes (“Modern Burglars,” director unknown, 1904). In some ways it was rather crude, with the set consisting of two large painted house façades facing each other, angled from the front, and a wall beyond them. The acrobatic burglars arrived over the wall to rob one house, propping a long board against an upper window to use as a chute for sliding furniture and other large objects down.

The action becomes faster and more impressively choreographed as police arrive, also over the wall, and give chase. Soon burglars and comic cops are diving through windows and doors in the two buildings, as well as performing comic acrobatics on the chute. The whole thing, as far as I could tell, was done in a single take, though there might have been some invisible cuts. If it was indeed one shot, it was a most impressive piece of staging and performance.

This ‘n’ that

Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1963 crime/road movie L’Aîné des Ferchaux (based on a minor Georges Simenon novel) is almost impossible to see on the big screen, apparently due to some sort of rights problem that keeps the French distributor from circulating it. (It is available on a region 2 French DVD without subtitles.) The festival managed to show it in the European widescreen thread by borrowing a print from Svenska Filminstitutet, complete with Swedish subtitles. Translations in Italian and English were projected on small screens below the image. I quickly got accustomed to skipping down to the read the third set of subtitles. It’s certainly not one of Melville’s masterpieces, but it’s definitely worth seeing.

The basic premise is that an unscrupulous banker, Dieudonné Ferchaux (veteran French star Charles Vanel), flees arrest by flying from Paris to New York and then setting out toward the South via car. Michel Maudet, an unsuccessful young boxer (Jean-Paul Belmondo), also unscrupulous but so far with no apparent serious crimes to his name, goes along as his secretary. Although the two seem to like each other, Michel becomes increasingly tempted to steal the suitcase stuffed with cash that Ferchaux has picked up in New York, while Ferchaux seems to lose interest in visiting various other places where he has stashed away large sums. The gradual switch in their power relationship furnishes one main line of interest.

The film is also remarkable in that the two stars did not go to the U.S.A. to appear in the considerable amount of landscape footage shot there by a second unit. Instead, they worked in interior sets in France, as well as exteriors that pass for America. Melville managed to stitch these two kinds of footage into a reasonably convincing depiction of an American road trip.

Another film that has long been hard to see outside Italy, at least in its original form, is Rossellini’s L’Amore (1948), two contrasting short tales displaying the acting talent of Anna Magnani. The first, Une voca umana, is based on Jean Cocteau’s  much-adapted short play, La voix humaine. Confined to an apartment, it concentrates on a woman talking on the phone with the lover who has recently left her, trying to convince him that she has adjusted to the break-up while demonstrating through her behavior that she is devastated. Rossellini never places the camera much further back than a plan-américain position, and most of the time the framing displays Magnani’s face in close-up. Short though it is, it becomes repetitive, and it is too evidently a display of virtuoso acting.

much-adapted short play, La voix humaine. Confined to an apartment, it concentrates on a woman talking on the phone with the lover who has recently left her, trying to convince him that she has adjusted to the break-up while demonstrating through her behavior that she is devastated. Rossellini never places the camera much further back than a plan-américain position, and most of the time the framing displays Magnani’s face in close-up. Short though it is, it becomes repetitive, and it is too evidently a display of virtuoso acting.

The longer second part, Il Miracolo, is more engaging and original. It is based on an idea by Fellini and a script by Tullio Pinelli and Rossellini. A feeble-minded homeless woman, Nannina, who is tending a herd of goats near a small Italian village, meets a traveler (played by Fellini, left) whom she, being very pious, assumes to be St. Joseph. He offers her wine and, when she falls asleep, rapes her. Learning that she is pregnant, and not realizing what the traveler did, Nannina becomes convinced that she is carrying the baby Jesus. She is teased and hounded by the townspeople. This part of the film led to censorship problems, not because of the sexual content (the rape is simply skipped over and merely implied) but because of the apparent parody of the Immaculate Conception. (This, too, has been available in a mediocre copy without subtitles on an Italian DVD.)

Apart from its innate interest, L’Amore is historically important for the “Miracle Decision” in the U.S., where it was banned for sacrilege. The Supreme Court decision in the case led to the extension of first-amendment protection to cinema.

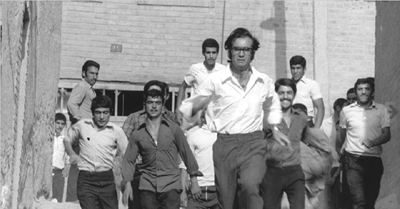

Il Cinema Ritrovato has become a venue for the exhibition of the latest restorations by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation. This organization restores films from countries whose archives do not have the means to do such work. Since 2007, the foundation has preserved on average three films a year. This year the items on show at Bologna included Filipino director Lino Brocka’s Manila in the Claws of Light (1975, also known as Manila in the Claws of Neon). I had never seen a Brocka film (it’s discussed in a passage of Film History: An Introduction, for which David was responsible), but I was impressed by this one, widely considered to be his best.

It follows a naive young man from the countryside whose girlfriend has become the victim of sex-trafficking; he seeks her in Manila and experiences unfair wage practices and other forms of corruption. Brocka managed to blend seamlessly an absorbing narrative with sympathetic characters and an undercurrent of bitter social critique. Remarkably, Brocka also shot a 22-minute making-of documentary, quite similar to modern DVD supplements, that explains how he created realistic scenes of construction work with a small budget and shooting on location with non-professionals.

Another World Cinema Foundation restoration shown this year is the 1971 classic, Ragbar (Downfall, directed by Bahram Bayzaie). Given the extraordinary burst of creativity that has occurred in Iranian filmmaking since the 1980s, I had high hopes for this. In some ways it resembles more recent classics, most notably in its setting in a school.

The hero is a misfit who has come to teach at the school and becomes the victim of pranks and taunts by his unruly students. A rumor gets started that he is in love with the older sister of one of the students, and in attempting to scotch the rumor, he falls in love with her. Gradually he comes to understand his students and gain their respect. The film is entertaining, though the slim plot seems dragged out too long. The approach is more like commercial mainstream art cinema than like more recent Iranian films. Culturally it is quite interesting, showing some of the customs of the era shortly before the overthrow of the Shah. Most notably the women wear western-style clothes, and some are unveiled.

Unfortunately I had to miss a third Foundation restoration, Ousmene Sembène’s early short Borom Sarret (1969).

The World Cinema Foundation screenings are among the high points of Ritrovato, and I look forward to seeing more of them in years to come. Among all the festival’s restorations of well-known classics (this year Hiroshima mon amour, Richard III, and so on), it was a pleasure to see as well some well-known but hitherto difficult to see films. I hope all three, plus Brocka’s making-of, are included in a future WCF DVD set. (The first set was issued last year and is available from amazon.fr.)

Finally, I managed to see a few of the films in the “War Is Near: 1938-1939” thread. One was a program of three of Humphrey Jennings’ less familiar documentaries, all from 1939: Spare Time, about how working-class people spend their leisure time; The First Days, on the preparations for war in England after its declaration; and S. S. Ionian, on a cargo ship paying visits to ports of call in the Mediterranean. The first two had the true Jennings touch, looking at everyday events with a fresh, unpretentiously poetic viewpoint. The third was more conventional, aimed at presenting information about the importance of non-military shipping for the war effort. All three films, along with a dozen others, are available on the first volume in the BFI’s region-free DVD edition of Jennings’ complete films.

I also saw Edmond T. Gréville’s Menaces (1940). Its story of impending war is what David would call a network narrative, set among the residents of a cheap Parisian hotel–a sort of low-rent version of Grand Hotel. Although most of the stories are not directly about the war, its threat hovers over them all. Perhaps the stand-out is Prof. Hoffman, a disfigured emigré German war veteran (Erich von Stroheim) who gradually realizes that once war breaks out, he will be an enemy alien in the country he considers home. (The film is available on a region 2, unsubtitled French DVD.)

Menaces was the last film I saw at this year’s festival, and now I look forward to being able to report in tandem with David at next year’s!

Once more we thank the Ritrovato team (especially Marcella Natale), led by Peter von Bagh, Guy Borlée,and Gian Luca Farinelli, for their visionary achievements. They have changed our conception of what a film festival can be, and they have led us to a deeper and wider appreciation of the glories of cinema.

[July 19: Thanks to Antti Alanen for pointing out that Saul and Jonathan Turell’s name has only one r. It’s spelled indiscriminately all over the internet with one r or two, so thanks also to Brian Carmody of Criterion for confirming that Turell is correct.]

[July 29: Guy Borlée has kindly sent me links for some of the festival events that have gone online at Vimeo since I posted this entry. There’s a set of all the lectures given during the week, including the Peter Becker and Jonathan Turell presentation on the Criterion Collection that I describe above (direct link to the Criterion session here). I mentioned Kevin Brownlow’s introduction to The Iron Mask, but he did a whole presentation on Allan Dwan as well. You can also watch the DVD awards ceremony.]

What next? A video lecture, I suppose. Well, actually, yeah….

DB here:

We’ve said several times that this website is an ongoing experiment. We started just by posting my CV and essays supplementing my books. Then came blogs. We quickly added illustrations to our entries, mostly frame enlargements and grabs. Eventually, video crept in. In 2011 we ran Tim Smith’s dissection of eye-scanning in There Will Be Blood. Last year, in coordination with our new edition of Film Art: An Introduction, we added online clips-plus-commentary (an example is on Criterion’s YouTube channel), and near the end of the year Erik Gunneson and I mounted a video essay on techniques of constructive editing.

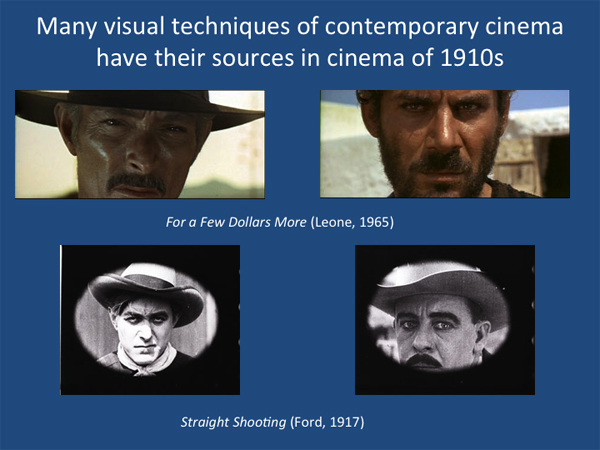

Today something new has been added. I’ve decided to retire some of the lectures I take on the road, and I’ll put them up as video lectures. They’re sort of Net substitutes for my show-and-tells about aspects of film that interest me. The first is called “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies,” and it’s devoted to what is for me the crucial period 1908-1920. It quickly surveys what was going on in cinema over those years before zeroing in on the key stylistic developments we’ve often written about here: the emergence of continuity editing and the brief but brilliant exploration of tableau staging.

The lecture isn’t a record of me pacing around talking. Rather, it’s a PowerPoint presentation that runs as a video, with my scratchy voice-over. I didn’t write a text, but rather talked it through as if I were presenting it live. It nakedly exposes my mannerisms and bad habits, but I hope they don’t get in the way of your enjoyment.

“How Motion Pictures Became the Movies” is designed for general audiences. I’ve built in comments for specialists too, in particular, some indications of different research approaches to understanding this period of change.

The talk runs just under 70 minutes, and it’s suitable for use in classes if people are inclined. I think it might be helpful in surveys of film history, courses on silent cinema, and courses on film analysis. If a teacher wants to break it into two parts, there’s a natural stopping point around the 35-minute mark.

Some slides have several images laid out comic-strip fashion, so the presentation plays best on a midsize display, like a desktop or biggish laptop. A couple of tests suggest that it looks okay projected for a group, but the instructor planning to screen it for a class should experiment first.

I plan to put up other lectures in a similar format, with HD capabilities. Next up is probably a talk about the aesthetics of early CinemaScope. I’d then like to spin off this current one and offer three 30-minute ones that go into more depth on developments in the 1910s.

The video is available at the bottom of this entry, but it’s also available on this page. There I provide a bibliography of the sources I mention in the course of the talk, as well as links to relevant blogs and essays elsewhere on the site.

If you find this interesting or worthwhile, please let your friends know about it. I don’t do Twitter or Facebook, but Kristin participates in the latter, and we can monitor tweets. Thanks to Erik for his dedication to this most recent task, and to all our readers for their support over the years.

Sometimes a shot . . .

I Topi Grigi, Chapter 6: Aristocrazia Canaglia.

DB here:

… just knocks you out.

In wrapping up my stay at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, where I concentrated mostly on German films of the late 1910s and early 1920s, I watched a copy of I Topi Grigi (“The Gray Rats”), a 1918 Italian serial. It’s part of an immense series devoted to the adventures of the cadaverous rogue Za La Mort. Directed by and starring the fascinating Emilio Ghione, it’s in the vein of Fantômas and Les Vampires, though I don’t find it as ingenious or funny or as skillfully directed as Feuillade’s masterpieces.

But then you get those moments. Za La Mort and his young charge Leo are aboard an ocean liner when it’s struck by a torpedo. The passengers panic and make for the lifeboats. It ought to be a spectacular scene reminiscent of Atlantis (1913), but there aren’t many shots devoted to this climax. We see only a few images of people rushing up to the deck from their cabins. The central shot showing the crisis is an image slung along the side of the ship, down the row of lifeboats as people scramble into them. The shot is interrupted by glimpses of men climbing the masts and survivors in the water, but this camera setup is the only one concentrating on the process of getting people offboard.

At first we’re looking down the row of boats, but, as you can tell from my top image, we can’t see much of anything–mostly a man in a nightshirt grabbing the hull of a lifeboat. Then, as the boat is lowered and he has to pull back, we get to see a lot more. Into the slot formed by the lifeboat supports, crisscrossed by ropes and rigging, slip faces and bits of bodies. A woman stoops, a man in silhouette shouts. Meanwhile, a dark-haired woman leans over the railing.

While our young man in the nightshirt sways precariously, the boat continues to descend and we can see even further down the row of lifeboats. A woman in the middle distance calls out. The woman at the railing has started to crawl down the side of the ship.

Now, in the depth of the shot, people are seen trying in vain to pile into the boats. Abruptly, a man on a rope swings into the shot.

The boats are edging away from the ship’s hull–a slight gap emerges in the distance–but we can see passengers still shoving to try to board them.

It’s over for these people. The lifeboats descend, the boy in the nightshirt is still stranded on the side, and the woman who has climbed down beside him vainly stretches out her arm. (See below.)

A new video essay from Flavorpill offers you “135 shots that restore your faith in cinema.” It’s mostly a collection of purty pitchers laced with emblematic moments from classics. But probably you, like me the day before yesterday, haven’t seen Topi Grigi, so my images offer no cosy film-nerd nostalgia. And compared to the Hallmark-Cards aesthetic on display in most of the video essay’s clips, this shot is pretty messy.

But it engages your vision in a dynamic way. It coaxes you to watch a process, in all its scrambling disorder, along a line of sight that emerges, gradually, as uncannily precise. Desperate faces and gestures cascade through a rigid geometry–frames within frames, receding arches like ribbing in a vault, taut diagonals slicing across the frame. Would I trade this concise, rousing, remorseless stream of images for the last forty minutes of Titanic? Yes.

Joseph North offers an admirably detailed chronology and contextualization of the series in his 2011 Masters Thesis, Emilio Ghione and the Mask of Za La Mort. It’s available as a pdf here. Thanks as well to Edward Branigan for alerting me to the Flavorpill video.