Archive for the '1910s cinema' Category

Solo in Bologna

Kristin here:

Two days before David and I were to set out for Bologna and its annual Il Cinema Ritrovato festival, back pain struck him. He decided not to go, and so our coverage this year will be briefer. I struggled to see as much as possible, but if anything, the program was even more packed than last year.

The auteurs

The main threads included four directors who are of historical interest. Raoul Walsh was the main attraction, with emphasis less on familiar classics like Roaring Twenties and White Heat and more on hard-to-see items like Me and My Gal and other early 1930s films. Lois Weber, the first important female director in American cinema, was represented with as complete a retrospective as possible, including fragments from features not otherwise extant. Jean Grémillon, one of the less famous French prestige directors during the 1930s and 1940s, was extensively represented. And there was Ivan Pyriev (or Pyr’ev, going by the program notes’ spelling), most famous as one of the main proponents of the “kholkoz [collective farm] musicals” of the last 1930s and 1940s.

I had seen a couple of Pyriev’s films and decided to see as many as possible of the series on offer, programmed by our long-time front-row neighbor in the Cineteca venues, Olaf Möller. Pyriev is an interesting case historically. He came to filmmaking just as the Soviet Montage movement of the 1920s was coming under official pressure for its formal complexity.

I had seen a couple of Pyriev’s films and decided to see as many as possible of the series on offer, programmed by our long-time front-row neighbor in the Cineteca venues, Olaf Möller. Pyriev is an interesting case historically. He came to filmmaking just as the Soviet Montage movement of the 1920s was coming under official pressure for its formal complexity.

The Civil Servant (or The State Functionary, 1931) was a full-blown, skillful leap into Montage, with an prologue of trains coming into Moscow, shot with canted framings, low angles, and quick cuts with trains moving left, then right. The rest is a satire on bureaucracy within the national railroad system—ostensibly set during the Civil War but clearly a contemporary story. It’s broad in its humor, and it has the obvious typage in the choice of actors, the wide-angle lenses that the Montage filmmakers explored in the late 1920s, and other scenes of quick cutting with jarring reversals of directions.

Official dislike of The Civil Servant kept Pyriev from directing again for three years. Turning his back on Montage, he went to the other extreme, helping to develop the kholkoz (collective-farm) musical and making some of its liveliest, most entertaining, and most enthusiastic examples of that genre. His Traktoristi of 1939 was not shown during the festival, but one that I hadn’t seen, Swineherd and Shepherd (1941), is fully its equal. From the moment the film begins, with the camera madly tracking backward through a birch forest as the heroine runs full tilt after it, singing joyously to the masses of pigs that emerge from corrals and gallop along with her, the spectator realizes that this film will be exactly what one wants and expects from Pyriev.

A later entry in the genre, The Cossacks of the Kuban (1950), was even better, and I can see why it is Olaf’s favorite. The opening vistas of immense wheat fields, gradually moving to scenes with tiny figures and finally to ranks of harvesting machines and trucks achieves a genuine grandeur, aided considerably by the fact that by this point Pyriev is working in color. The story goes beyond the simple stock figures of some of the earlier musicals, with a stubborn Cossack who heads one collective farm nearly missing his chance at romance with a widow who heads a rival farm.

Overall, I like these films a little better than those of his more famous colleague in the creation of buoyant musicals, Grigori Alexandrov. Yet it has to be mentioned that there is a certain underlying unease in being entertained by films that created hugely idealized images of life on collective farms. In reality many peasants were starving, and few were working with such cheerful enthusiasm to increase production for the sake of the great Soviet state. One might rationalize this dissonance by thinking that Pyriev was perhaps making fun of his subject with over-the-top dialogue and musical numbers. Yet surely to many audiences at the time, this was escapist entertainment, and urban audiences may have had little sense of the blatant inaccuracy of the portrayals of the countryside.

Two more straightforward dramas, The Party Card (1936, below) and The District Secretary (1942), a war story, were more conventional Socialist Realist works, skillfully done but lacking the appeal of Pyriev’s lighter films.

It was sad to see the one post-Stalinist film from Pyriev’s late career, his adaptation of The Idiot (1958). A sumptuous production, again in color, it consisted almost entirely of overblown confrontations among characters. The actors shout all their lines at each other with almost no variation in the dramatic tone, with everything underlined by an amazingly intrusive musical score.

I saw only a few of the Walsh films, since they frequently conflicted with the Pyrievs and Grémillons and just about everything else on offer. To me, the director was a bit oversold. Peter von Bagh’s introduction to the catalog says, “Unjustly, Raoul Walsh, although blessed with so much cinephilic worship, is usually placed a few notches below his more revered colleagues Ford and Hawks. Now he will have a chance to be upgraded, in our continuing series featuring extensive screenings from Walsh’s silent period through his very rare early sound films.” Perhaps Walsh will go up a notch in people’s estimations—the screenings of his films were certainly very popular—but not, I think, the few notches it would take to place him alongside these two other masters. I enjoyed Me and My Gal, a rare 1932 comedy in which Spencer Tracy and a very young Joan Bennett adeptly exchange snappy patter, yet it occurred to me more than once during the screening that Twentieth Century (1934) is a much funnier film.

The Big Trail, shone in its original wide-screen Grandeur format on the giant Arlecchino screen, was better than I expected. Walsh was given enormous resources to tell the story of a large wagon train making its way to Oregon from the Mississippi. He showed off the crowds of wagons, cattle, and people by the simple expedient of raising the camera height so that most of the screen’s height became a tapestry of people stretching into the distance, all going about their business while the main dramatic action in the foreground occurred. This often involved a very young John Wayne, whose occasional awkward delivery of lines managed somehow to fit with his character.

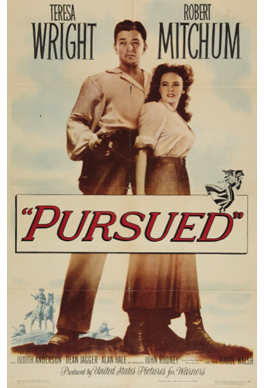

Pursued (1947), shown in an excellent 35mm print, was one of the few certified Walsh masterpieces in the series. Of course I enjoyed it. It struck me how crucial the casting of Teresa Wright as heroine Thor Callum was. So often Westerns have minor actresses as the love interest, women that one can seldom recall seeing in any other film—starlets rather than stars. Thor’s dramatic arc is pretty extreme and somewhat implausible, but Wright manages to make the character convincing and sympathetic, as well as an effective counterpoint to Robert Mitchum’s stolid Jeb Rand. James Wong Howe’s cinematography was also a big plus.

Pursued (1947), shown in an excellent 35mm print, was one of the few certified Walsh masterpieces in the series. Of course I enjoyed it. It struck me how crucial the casting of Teresa Wright as heroine Thor Callum was. So often Westerns have minor actresses as the love interest, women that one can seldom recall seeing in any other film—starlets rather than stars. Thor’s dramatic arc is pretty extreme and somewhat implausible, but Wright manages to make the character convincing and sympathetic, as well as an effective counterpoint to Robert Mitchum’s stolid Jeb Rand. James Wong Howe’s cinematography was also a big plus.

Few of Walsh’s pre-1920s films survive, but those few were shown. I skipped the wonderful Regeneration, having seen it multiple times, but I caught The Mystery of the Hindu Image, notable mainly for Walsh’s own performance as the detective, and Pillars of Society, a somewhat stodgy adaptation of the Ibsen play.

I can’t say much about the Weber films, since they were consistently in conflict with screenings of films by the other main auteurs. I regret having skipped one Pyriev film, Six O’clock in the Evening after the War (1944) to see Shoes (1916), which had been touted as one of the director’s best. It proved a considerable disappointment, stuffed with expository intertitles that often simply described what we could already see from the action in the images. This may have been because Weber’s “discovery,” Mary McLaren, was so inexpressive. She almost constantly wore the same expression of resigned sadness at her family’s grinding poverty, varying it occasionally with a look of annoyance at her father’s shiftless behavior. I tried to steer people to The Blot, which is probably Weber’s masterpiece among the surviving films.

It was fairly easy to see most of the Grémillon titles, because a number of them were repeated in the course of the week. I enjoyed Maldone, which I had seen once long ago. Its story involves a runaway heir to a large estate who has run away as a young man and now, in late middle age, works on a canal barge. Infatuated with a beautiful gypsy and spurned by her, he returns to claim his inheritance, only to be disgusted by gentrified life. Like Pyriev, Grémillon came late to one of the commercial avant-garde movements of the 1920s, French Impressionism. He uses the subjective camera effects and the rhythmic editing in a straightforward way, with little of the flashiness of a L’Herbier or a Gance. Maldone and his subsequent film, Gardiens des phare (1929), shown at the festival in a tinted Japanese print, remind me of perhaps the best filmmaker of the Impressionist movement, Jean Epstein.

This legacy might logically have led Grémillon into the Poetic Realism of France in the 1930s. Unfortunately his first sound film, La petite Lise (1930), which might be said to fit into that tradition, was not shown. After seeing several of the films on offer this year, I still think it may be his masterpiece. (We talk about it briefly in the section on early sound cinema in Film History: An Introduction.) Though some might argue that he has at least one foot in that tradition, his work is perhaps closer to what the Cahiers du cinéma critics later dubbed the Cinema of Quality.

As for the others I caught: L’étrange Monsieur Victor (1938, dominated by Raimu as a successful merchant who is not all he seems), Remorques(1939-41, perhaps Grémillon’s best-known film, re-teaming the favorite French couple of the 1930s, Jean Gabin and Michele Morgan), and Pattes blanches (literally, “White putties,” 1948). I enjoyed them all, and yet there was no sense of discovering an overlooked genius. Best of the sound features for me was Pattes blanches, which tempered Grémillon’s taste for melodrama with a hint of surrealism. The obsessive young wastrel Maurice (played by a very young Michel Bouquet), the gamine hunchback maid who falls in love with the reclusive and menacing local nobleman, and the nobleman himself, invariably bizarrely clad in his white puttees, help give the film a fascination that the others, for me at least, lack.

The themes

There were other threads oriented by genre or topic or period. These I sampled when it was possible to insert them into my schedule. One of these was “After the Crash: Cinema and the 1929 Crisis,” which included an intriguing potpourri of documentaries and fiction films from several countries and political stances, from Borzage’s A Man’s Castle to two short films by Communist-leaning Slatan Dudow, director of Kuhle Wampe. Because of my interest in international cinema styles of the late 1920s and early 1930s, I went to Pál Fejös’s Sonnenstrahl (“Sun Rays,” 1933) was shown in the festival’s first time slot, 2:30 on Saturday afternoon. It thus competed with the first showing of the Grandeur version of The Big Trail and the first program of the “Cento anni fa” set of 96 films from 1912, but such is Bologna’s lavish scheduling.

Fejös, a Hungarian, made films in Hollywood, France, Denmark, Sweden, and a number of other countries. Sonnenstrahl, with its romance between German actor Gustav Fröhlich and French leading lady Annabella, is basically a reworking of the director’s best-known film, Lonesome (1928), with touches of 7th Heaven (Borzage, 1927), redone for the Depression era. It’s a pleasant enough piece, though not up to Fejös’s best work of the 1920s. Again, the program claims to too much for the filmmaker by saying that some historians consider him “as one of the cinema’s great poets, along with Murnau and Borzage.”

The Depression program also included a surprisingly good early sound film by Julien Duvivier, David Golder (1931, above). It’s the story of a wealthy businessman, played by Harry Baur, who discovers that his wife and daughter love him only for his money. How he could have lived this long with them without realizing this is perhaps a weakness in the plot, but from the start Duvivier showed a remarkable assurance in framing, cutting, and camera movement that was continually in evidence. Sets by the great Lazare Meerson also enhanced the style.

Baur also starred as Jean Valjean in Raymond Bernard’s 1934 three-part Les Misérables. I skipped the screenings, since the film is available in a Criterion boxed set (along with Bernard’s remarkable 1932 anti-war film Wooden Crosses). The Bernard film was part of the “Ritrovati and Restaurati” thread. The presence of Baur in both David Golder and Les Misérables led to the Depression and Ritorvati threads to weave together to produce a third: “Homage to Harry Baur.”

The only other entry in this brief thematic collection was Duvivier’s La tête d’un homme (1933), the third film based on a novel by Georges Simenon. Baur stars as Commissioner Maigret, and Valery Inkijinoff (known largely as the hero of Pudovkin’s Storm over Asia/The Heir of Ghengis Khan, though he acted in numerous other films as well) plays the doomed, obsessive villain, Radek. The film is not as accomplished as David Golder, but it’s an entertaining little thriller with some novel twists. Early in the film the murder is revealed, and we know from the start the Radek committed it. The duel between him and Maigret becomes the focus of the action. Moreover, the very first scene introduces a thoroughly unlikeable fellow who initially seems to be the villain, a womanizing cad who lives by gambling and other unsavory activities, yet who himself eventually comes to be tormented and threatened by Radek.

Another intriguing thread was “Japan Speaks Out! The First Talkies from the Land of the Rising Sun.” Ordinarily I would have tried to see most of these, but again they conflicted with the auteur threads I was trying to follow. I did make it a point to see Mizoguchi’s first sound film, Hometown (1930, above), since it’s one of the hardest to see. A part talkie built around a famous Japanese tenor and opera singer, it was more an historical curiosity than a satisfying film. I reluctantly skipped Heinosuke Gosho’s delightful Madame and Wife (aka The Neighbor’s Wife and Mine), the first really successful Japanese talkie, having seen it a number of times. On David’s and Tony Raynes’ advice, I caught Yasujiro Shimazu’s First Steps Ashore, a romantic tale inspired by Von Sternberg’s The Docks of New York. It didn’t quite match the original (as what could?) but was an entertaining tale well acted by the two leads. The first frame below reflects something of the style of Docks of New York, but the second, more typical of the film, is pure Shochiku.

The organizers of Il Cinema Ritrovato have declared that they will continue to show films on 35mm as long as possible. Most of the screenings that I attended were indeed on film. There’s no doubt that the move to digital restoration became dramatically more apparent this year. Nearly all of the 10 pm screenings on the Piazza Maggiore were digital copies, including Lawrence of Arabia, Lola, La grande illusion, and Prix de beauté. David and I don’t usually go to these screenings, since we invariably want to see films in the 9 or 9:30 AM time slots and don’t want to fall asleep during them. But I did catch two digital restorations shown earlier in the evening in the Arlecchino.

The first, Voyage to Italy, was flawless and sharp—perhaps a little too sharp. I liked the film much better than the first time I saw it, maybe because I understood better the claims that are made for it as a forerunner of the art cinema of the 1960s, with the aimless, confused couple presaging the characters of directors like Antonioni.

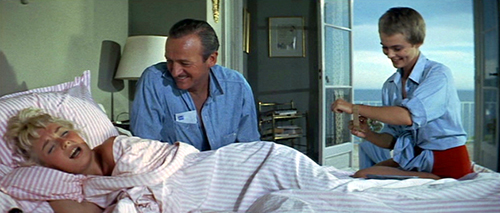

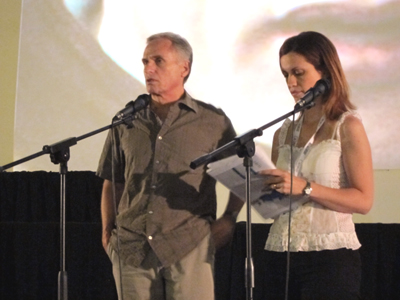

Perhaps the high point of my week, though, was an entry in an ongoing thread at the festival, “Searching for Colour in Films.” There were many films in this category, which was broken down into the silent and sound eras. Bonjour Tristesse may well be my favorite Otto Preminger film. Our old friend Grover Crisp (above, with interpreter) returned to Bologna to introduce it in a digital restoration, but one which, he assured us, retained the grain of the original film. It was certainly a beautiful copy and looked great on the Arlecchino screen. (The frames at the top and bottom of this entry were taken from a 35mm copy, not a DVD or the new restoration.)

Il Cinema Ritrovato grows more popular each year. A number of our friends from other festivals and alumni of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s film studies program attended for the first time and vowed to return. Perhaps a sign that the event is gaining real prominence internationally was the fact that Indiewire columnist Meredith Brody also made her first visit. She conveys the impressions of a newbie in a series of posts: Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, Day 4, and Day 5. For many images of the festival guests and screenings, see the official website.

David analyzes one Hitchcock-like scene in The Party Card in his On the History of Film Style.

July 9: Thanks to Ivo Blom for correcting my spelling of Harry Baur’s name.

A variation on a sunbeam: Exploring a Griffith Biograph film

Kristin here:

On April 21 a young Spanish film student uploaded his remarkable little film, Variation: The Sunbeam, David W. Griffith, 1912 onto Vimeo. There it languished, like so many contributions to the internet, good and bad. In the first four months of its presence on the site, it attracted 17 views.

Then, on August 17, Variation was viewed twice and earned its first “Like.” (One has to be a member of Vimeo to Like a film, so one cannot assume that none of its viewers to that point had enjoyed it.) That first Like, and perhaps both views were by Kevin B. Lee, best known for his many video essays on classic films. (See here for an index; I contributed the commentary for the La roue entry.) Over the next week and a half there were five additional views, four on August 28. I suspect some or all of these last ones were repeat visits by Kevin, since on August 31 he was the first to post an essay on Variation: The Sunbeam, David W. Griffith, 1912 (hereafter Variation), along with some information on its maker, Aitor Gametxo.

The immediate result was a flurry though not a stampede of views: 33 on August 31, along with a second Like; and 15 on September 1, with a third Like. One of those views and the third Like were mine. On September 2, there were 12 views, dwindling to 2 on September 3 and 1 on September 4.

(Among the viewers after the Fandor entry was Evan Davis, University of Wisconsin-Madison film-studies alumnus, who read Lee’s blog, watched the film, and passed the links along to us. Thanks, Evan!)

It’s a pity that more attention has not been paid to this charming, clever, and informative film. Not only would people enjoy it, but it could easily be used as a tool for those teaching, or indeed researching silent cinema. So here’s my bid to help it go viral.

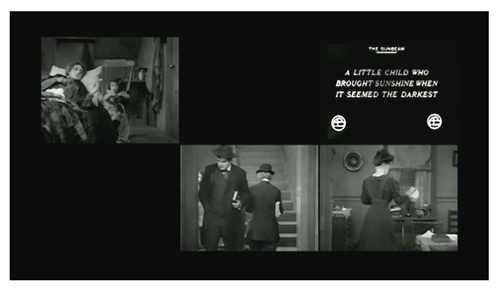

Variation is a found-footage film based on Griffith’s American Biograph one-reeler The Sunbeam, made in December, 1911, and released on March 18, 1912. It is not among the most famous of the nearly 500 one- and two-reelers Griffith directed at AB between 1908 and 1913, but it’s better known than most. In the opening, a sick mother dies, and her little girl, thinking her mother is asleep, goes out into the hallways of their working-class apartment building. She tries to find someone to play with, but everyone rebuffs her until she manages to charm two lonely people, a bachelor and spinster, who live opposite each other on the floor below the child’s home.

Aitor noticed three key things about the film. First, the action takes place in a very limited space, with the three apartments and hallway all close to each other. Second, the doorways through which the characters pass between these rooms are on the edges of the screen, so that when they exit through the doorway in one shot and after the cut enter the space on the other side of the doorway, there is often a sort of elusive match on action formed (what I termed a “frame cut” in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, p. 205 and figures 16.36 and 37). Third, and perhaps most importantly, Griffith was intercutting actions that were happening simultaneously, so that at many of the cuts, he jumped from the end of an action in one space back in time to catch up with what had been happening in another space. At times he would jump back twice if simultaneous actions were happening in three spaces.

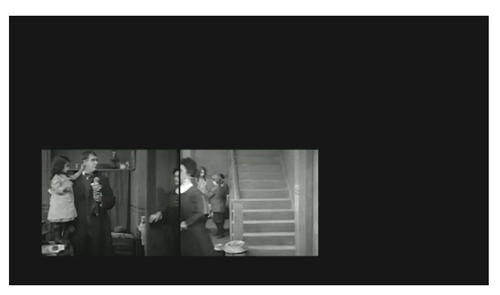

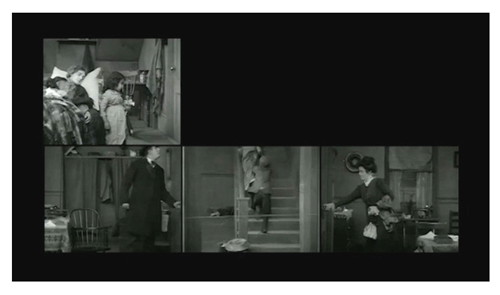

Aitor has taken the individual shots and redone them, putting them into a grid of six small frames, three on the bottom and three at the top. Scenes in the child’s upstairs apartment are shown only in the upper left, the top of the stairway in the upper center, and the two apartments on the ground floor at the sides, with the hallway and bottom of the stairs between them. (See above.) These are roughly the actual positions these spaces occupy in relation to each other in the building represented in the film. The shots run in their true temporal relations, so that there is no jumping back.

I suggest that before reading further, you watch The Sunbeam, especially if you have never seen it before. It would be impossible, I think, to entirely follow the story just from seeing Variation. The shots are so reduced in size to fit into the grid that small but important gestures and details get lost. Here is the original film, from YouTube.

With Aitor’s kind permission, we present his take on Griffith’s one-reeler. (The Sunbeam runs about 15 minutes, but due to the simultaneous presentation of many shots, Variation is only about 10 minutes.) Click on the “Vimeo” logo in the lower right corner for a larger image:

A fascinating film, isn’t it? I think many viewers would reach the end of Variation and wish that the same sort of presentation could be created for other films–at least, early ones that are short enough to make such rearrangement viable. Kevin Lee is enthusiastic about the idea: “Imagine this multi-dimensional, real-time approach being applied to footage from other films, as a way of not just mapping out scenes in a movie, but also gaining insight into filmmaking technique.” It might be possible, but the six-rectangle grid used here would not work for very many films. Aitor has chosen the ideal film for such an approach. Not only are there a limited number of significant characters, but they also live in the same building, with three rooms and a hallway, all viewed from the same direction, making them fit perfectly into a “doll-house” style scene.

Had Griffith not routinely shot directly toward the back wall in all his sets, placing the shots directly side by side across the grid would not work, at least not so neatly. Many other directors of this era were exploring shooting into corners and having doorways for entrances and exits centered at the rear. Perhaps filmmakers like Aitor could still place different shots side by side, but the actors’ movements from one space to another would not be so smooth. One of the attractions of Variation is that those movements are smooth, and as a result the action plays as if it were part of a continuous, “real” film.

Even other Griffith films shot in the style of The Sunbeam would be far more difficult to lay out on a similar grid. Longer rows of more rectangles would need to be added, or the upper row would have to represent actions taking place at a distance and the lower one actions taking place within a building. (I’m thinking here of something like The Lonely Villa, where action in a series of contiguous rooms is intercut with the husband’s race from a distant locale back to his house.) The placement of the bachelor’s room opposite the spinster’s, on either side of the hallway through which all of the minor characters pass, is crucial to Aitor’s project. A complex film with many characters and locales might create a grid with rectangles too small to be grasped by the viewers. Ways of indicating techniques like flashbacks would have to be devised. And of course, not all films contain simultaneous action.

Variation has some technical disadvantages. The titles appear in the upper right corner of the screen, since no locale opposite the child’s apartment is ever shown. The titles are small and difficult to read, and since they pop up simultaneously with the action, it’s almost impossible to read them anyway. One cannot tell where the titles originally came in the flow of shots, though one can always check the original film. Another problem is the cropping of the images on all four sides. The DVD copies are somewhat cropped, and more of the image is eliminated in the Variation frames; the action of the little heroine hiding a hairpiece in the spinster’s home, an important motivation for later action, can barely be grasped because it is so small a detail and happens at the very bottom of the frame; in the DVDs it can be clearly seen.

The Griffith Project and our knowledge of his techniques

I do not intend by any means to diminish what Aitor has accomplished when I say that the three main techniques he works from have been known to Griffith scholars for years. Variation offers a new way of examining and explaining those techniques.

Griffith has, of course, been one of the most closely studied filmmakers in history. A vast summary of and contribution to the research on Griffith was recently compiled by “Il Giornate del Cinema Muto” film festival in Pordenone, Italy. From 1997 to 2008, the festival mounted a nearly complete retrospective of Griffith’s work, hampered only by those films which still exist only as negatives or in other forms that could not be projected. A team of experts divided up the work and wrote extensive program notes for every single film Griffith made, whether it was shown at the festival or not. The notes, some more general essays, and Griffith’s writings were edited into twelve volumes jointly published by the festival and the British Film Institute (1999-2008). I had the privilege of contributing notes to most of the volumes, and although I cannot claim to know Griffith’s entire œuvre intimately, I got to know the films assigned to me quite well and learned a great deal about his methods.

The program notes for The Sunbeam were written by Griffith specialist Russell Merritt (Volume 5, 2001). As these excerpts from his description of the film’s setting indicate, the doll-house arrangement of the sets in The Sunbeam were distinctive, but not atypical of Griffith’s approach:

This was the second of Griffith’s three December tenement films (falling between The Transformation of Mike and The String of Pearls); spatially it is his simplest. Griffith uses only five setups (fewer than half what he works with in The Transformation of Mike and The String of Pearls.), but far from feeling cramped or monotonous, the three rooms and two hallways spaces seem perfectly designed for the playful romps, the practical jokes, and the unfolding of the gentle love story.

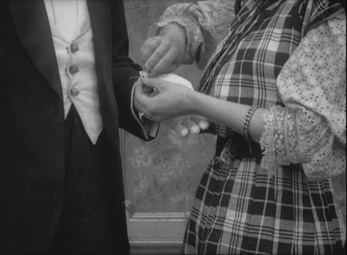

By 1911, the Griffith apartment set had developed a personality of its own, or more precisely, had become both distinctive and flexible enough to accommodate a broad range of narratives. Griffith’s planimetric style, with the camera always aimed straight on into the back wall with at least one side of the room aligned to the margin of the frame, had become as much a Biograph signature as the last-minute rescue, the fade-out, parallel editing, and the stock company of actors [….] In The Sunbeam, the familiar hallway and one-room apartments turn into something resembling a row of a child’s wooden blocks or the rooms in a child’s dollhouse, albeit with a dead mother in the garret. In each space, whether the hallway, the spinster’s apartment or the bachelor’s one-room across the hall, there is something to play with or play upon. The prank with the string stretched across the hallway literally links the two apartments and provides the perfect center of a the film–a gag that depends upon the mirror symmetries of the rooms and the tug-of-war actions of the two incipient sweethearts. (p. 196)

For the prank with the stretched string made symmetrical spatially as well as temporally, see below.

Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ book Theatre to Film (1997) points out that cutting among multiple adjacent interior rooms was typical of Griffith’s work in this period: “By early [1911] a film like Three Sisters has a climactic sequence of 28 shots alternating between three set-ups–long-shot views of three rooms, a kitchen, a hall, and a bedroom, which movements from room to room that coincide with cuts establish as side by side.” (p. 189) My own notes for The Griffith Project volumes discuss adjacent sets and room-to-room movements using frame cuts. (See the end of this entry for a list.)

Griffith’s use of editing to convey simultaneous events, as well as to portray thoughts and flashbacks has been extensively discussed in the literature on the director.

What is remarkable is that a 22-year-old film student has noticed these devices and found a simple, elegant method to demonstrate what we already knew, but with greater precision and vividness than could be done with prose analysis. To experts, that is what should make Aitor’s film so appealing.

For example, the precision of Griffith’s matches on action at the frame cuts is illustrated time and again in Variation:

Were it not for the fact that Griffith’s camera is closer to the action in the smaller hallway set than it is in the two outer rooms, the spinster’s move through the door would almost appear to be a single smooth glide. Unless one freezes the frame, as I have done here, some of these movements look uncannily continuous.

For those teaching or reading Film Art: An Introduction, Variation also provides a clear example of story time versus plot time. Griffith’s The Sunbeam presents us plot time, with its jumps backward to cover all the action in multiple locales. Aitor’s film presents story action as we ordinarily would reconstruct it only in our minds. Usually we describe story action with synopses or outlines. To see it played out in real time is a rare treat.

The filmmaker

Aitor has a blog, which contains primarily many lovely still photographs taken in Spain, Ireland, and the United Kingdom. It offers, however, minimal information about him. Kevin Lee wrote to ask him for information, which is included in the Fandor entry linked above. I also emailed Aitor with some questions to further contextualize Variation, and he provided a short summary of his background and his interest in Griffith.

My name is Aitor Gametxo. I was born in Bilbao in 1989 and have been living in Lekeitio. I started the Communication and Film degree in the University of the Basque Country, but I moved to the University of Barcelona to finish it this year. I’m currently living and working in Barcelona, and I’m going to do a “Creative Documentary” masters degree this upcoming year. I really enjoy taking pictures of everyday things and places, as a way of reporting reality. I also love film, specially documentaries, found footage films and cinema-essay pieces. I honestly believe in the power films have to make us think about things. Not only because of the topic the film is about, but also about the way in which the film is made (a kind of dialectics between Bill Nichols’ expository and reflexive modes). I love watching old (and odd) films and thinking about things that are different from the purpose they were created for. (As I told Kevin) we are able to take some footage which is temporally and geographically unconnected to us and remodel, or refix, or remix… it, giving birth to another work. This is the way I see the found-footage praxis.

About this particular film, The Sunbeam, I watched it for the first time just before doing the variation. I knew other works made by Griffith, such as “Intolerance” (quoted in several film history books). But this was unknown for me, so that the first watching was crucial. While I was enjoying it, I was wondering what the place where it was shot looked like. I suddenly imagined it as a two-floor house, where the characters cross in some moments. Also the doors were essential to fix one part with another. This was the main idea where I worked on. It was great fun doing it.

The result is this variation in real-time action of the classic work where we can see how Griffith worked on. It’s like returning back to Griffith’s mind, to the first idea, as he imagined one hundred years ago (!) how The Sunbeam would look like. This is the magic of cinema.

My contributions to The Griffith Project‘s program notes for the Biograph years are these. In Volume 2, January-June 1909: Those Boys; The Fascinating Mrs. Francis; Those Awful Hats; The Cord of Life; The Brahma Diamond; Politician’s Love Story; Jones and the Lady Book Agent; His Wife’s Mother; The Golden Louis; and His Ward’s Love. In Volume 3, July-December 1909: Lines of White on a Sullen Sea; In the Watches of the Night; What’s Your Hurry?; Nursing a Viper; The Light That Came; The Restoration. In Volume 4, 1910: A Child’s Faith; The Italian Barber; His Trust; His Trust Fulfilled; The Two Paths; and Three Sisters. In Volume 5, 1911: The Lonedale Operator; The Spanish Gypsy; The Broken Cross; The Chief’s Daughter; A Knight of the Road; and Madame Rex. In Volume 6, 1912: The Unwelcome Guest; The New York Hat; My Hero; and The Burglar’s Dilemma. In Volume 7, 1913: The Hero of Little Italy; The Perfidy of Mary; and A Misunderstood Boy.

Like the other contributors, I found myself dealing with a few famous films (e.g., the wonderful Lines of White on a Sullen Sea) and others that were largely unknown. Each little cluster of titles assigned to us consisted of films that had been made sequentially, so that each of us could get an intensive look into Griffith’s work over the course of a few weeks. It proved to be a rewarding way of approaching the study of the director. The general editor for the series was Paulo Cherchi Usai, assisted by Cindi Rowell.

The Sunbeam is also available in the U.S. in two DVD sets: Image’s “D. W. Griffith: Years of Discovery: 1909-1913” and Kino’s “D. W. Griffith’s Biograph Shorts Special Edition.” (The discs can also be bought separately.)

Capellani trionfante

Quatre-vingt-treize (1914)

Kristin here:

The early films of Albert Capellani are probably the most significant of all the discoveries of the Hundred Years Ago series.

Mariann Lewinsky

During the recent Il Cinema Ritrovato, I was somewhat surprised at the relatively small audiences for the programs that included films by Albert Capellani. Those films formed the second half of a large Capellani retrospective that began during the 2010 festival. Last year’s program was a revelation to me, and this year’s only confirmed my sense that here is a truly major discovery from the period before World War I. No doubt the addition of a fourth venue and the appeal of the Boris Barnet and early Howard Hawks retrospectives drew some attendees away.

As I wrote in my first Capellani entry, his significance has only slowly become apparent over several of the festivals. Initially his films were few and scattered through the annual “Cento Anni Fa” seasons of movies made one hundred years earlier. (The first “Cento Anni Fa” program in 2003 was curated by Tom Gunning; those since have been curated by Mariann Lewinsky.)

My first entry was handicapped by the fact that almost none of the films was available on DVD, and few of them had ever been accessible for researchers to view in archives–Germinal being the main exception. For illustrations, I mostly resorted to online versions of a few of the films, mediocre in visual quality and covered with bugs and time read-outs. The situation has changed enormously in the intervening year. Many more films have been restored; many of the archival notes at the beginning of this year’s prints were dated 2011. Moreover, in May Pathé brought out the Coffret Albert Capellani, a four-disc set with seven of the best-preserved films of 1906, as well as L’Assomoir and three major features from 1913 and 1914. Filling in the gaps to a considerable extent is the Albert Capellani: Un Cinema di Grandeur disc, from the Cineteca di Bologna, released just in time for the festival; it contains twelve films from 1905 to 1911. Between them these releases contain 23 films, plus some fragments. (The contents are more extensive than it might appear, since the three features alone add up to about seven hours.) Booklets accompanying the DVDs provide much up-to-date information on Capellani. It’s hard to think of an early filmmaker whose work has gone from such scarcity to such abundance in a single year. Once again, a driving force behind this dramatic improvement has been Mariann, working with La Fondation Jerôme-Seydoux-Pathé and the archives that provided print material.

I have taken advantage of this new availability to return to my earlier entry and add illustrations to descriptions of such important films as L’Arlésienne and L’Épouvante, which I could only summarize verbally when I first wrote it. This entry takes up where that one left off, with comments on several of the newly revealed films, or in one case, a new version.

For a list of all the Capellani films so far shown at Bologna and their availability on DVD, see the end of this entry.

An artist of the 19th Century meets a new art form

Those festival guests who missed the Capellani films missed, in my opinion, the rewriting of early film history. He is not simply another important silent filmmaker to be placed in the pantheon. Film by film, this year and last, I kept comparing what I was watching with what D. W. Griffith had made that same year. In each case, Capellani’s film seemed more sophisticated, more engaging, and more polished. Overall Capellani may not have been a better director than Griffith, but for the period of the French films, I believe it would not be exaggerating to say that he was: L’Arlésienne (1908) compared with anything Griffith did that year or L’Assomoir (1909) versus The Lonely Villa or even The Country Doctor. Capellani’s L’Épouvante (1911) was shown again this year; I had to shake my head in amazement that it was made the same year as another woman-in-danger film, The Lonedale Operator. Nothing in Griffith’s pre-war career comes close to Les Misérables or Germinal.

Both Griffith and Capellani came from the theatre, though the French director had already had a much more successful career there than had the American. Both had a strong bent toward melodrama and historical epics. But their styles developed along different lines. Undoubtedly Griffith’s pioneering work in editing sets him apart; Capellani never ventured far in that area. Capellani’s strengths were in the tableau style, with lengthy takes and intricately staged action. (For David’s thoughts on the tableau style, see here and here.) Rather, his strengths were in his elaborate staging of scenes, whether with one actor or a crowd. Perhaps because of his theatrical success, from early on Pathé must have given him generous budgets, for his settings are more opulent than Griffith’s, and he frequently went on location to the spectacular and picturesque landscapes and buildings of France. For example, he could simply take his team into old streets in Paris and create a more realistic impression of the city in the French Revolutionary era than Griffith could manage with the sets of Orphans of the Storm eight years later. (See left, Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge, 1914; note how close Capellani places the camera to the wall at the left, exaggerating at once the sense of depth and of narrowness.)

There is no doubt that in the long run, Griffith’s editing-based approach won out and helped establish the norms that remain with us to this day. It has been all too easy to trace the history of cinema as, at least implicitly, a history of innovations in editing. The great directors were those who fit into that specific history. Although Griffith never entirely mastered the classical Hollywood style the way Allan Dwan or Rex Ingram or Maurice Tourneur did, the continuity editing system undoubtedly grew in part out of techniques he popularized. In an historiographic approach based on editing, those who did not contribute to its development are likely to be passed over. Capellani uses every technique but editing with great artistry, and hence his films may be easy to dismiss as theatrical or old-fashioned. Moreover, many of them are based on 19th-Century classics, especially by Zola and Dumas, even when they deal with an older period, notably the French Revolution in his last two surviving French features, Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge and Quatre-Vingt-Treize.

Yes, as Mariann wrote in last year’s catalogue, “Capellani’s profile made him the target of a film historical trend–now long discredited–which criticised ‘the theatrical’ and promoted ‘the filmic.’ This is perhaps why he was so underestimated.” I am not sure that the contrast between theatrical and filmic cinema has entirely disappeared even today, but if we assume that all film techniques are equal, we can better appreciate Capellani in the context of his era.

I admit that, to a film historian or buff who learned early cinema from seeing Griffith and Chaplin and perhaps Hart and Feuillade, Capellani’s films may at first take some getting used to before their virtues become apparent. A feeling for Victorian narrative art, both written and visual, would help. At first, the acting might seem histrionic, and there are probably few, if any other directors’ films that so well preserve the stage conventions of the previous century. But for the most part, the acting in Capellani’s films is quite brilliant. The lack of editing might be a hurdle for some. Capellani also entirely avoided dialogue titles, and the expository titles are few. Characters are constantly writing and reading letters, which substitute for intertitles. It’s a convention one must simply accept, and it forces the viewer to concentrate fiercely on the actors’ faces and gestures, which carry the narrative information. For me, all this simply adds up to gripping filmmaking.

Take L’Assomoir, the earliest undeniable masterpiece from among the films so far shown at Bologna (though L’Homme aux gants blancs and L’Arlésienne come close). It is full of lengthy takes with intricate choreography. In all his films, Capellani clearly gave precise movements and business to each actor present, no matter how insignificant, and their faces, stances, and gestures, often fairly broad, make up for the almost entire lack of cut-ins. Take the scene where Gervaise and her new fiancé Copeau celebrate their engagement in an open-air café, with the proceedings interrupted at intervals by Gervaise’s former lover Lantier and the vengeful Virginie, with whom Lantier has taken up. The scene is done in a single two-minute shot, with the fluid action moving forward and back, in and out.

The ten frames below show phases of the action:

(1) Lantier in the foreground and Virginie in the middle ground watch the engagement party guests arrive. (2) Virginie speaks to Gervaise as Copeau comes forward.

(3) The guests begin to dance, with an organ-grinder coming in from the right. (4) The dancers move out left, and Copeau and Virginie begin to dance.

(5) They move out left with the organ-grinder, leaving Gervaise alone. (6) A comic friend who is continually eating comes back in to speak to Gervaise and then leaves.

(7) Lantier comes in from the right and starts bullying Gervaise. (8) Another friend comes in and drives him away out right.

(9) The dancers and organ-grinder return, with Virginie still dancing with Copeau. (10) The scene ends as Gervaise sits disconsolately while Virginie moves to Lantier and the pair watch Gervaise menacingly from the extreme right edge of the frame.

Similarly complex scenes, notably a celebration of Gervaise’s birthday, follow, culminating in a final shot that runs 6:45 minutes, out of a 35:46 minute film! (There is a pair of titles in Flemish and French that interrupt the shot early on, but the take was clearly continuous, and the titles seem likely to have been added by the exhibitor in whose collection the sole known surviving print was discovered.)

As Mariann also points out, one can find “filmic” elements in Capellani, including “the sheer photographic beauty of exterior shots, which is not to be found in the work of any of his contemporaries.” The frame at the top of this entry, made in 1914, is striking enough. (Mont St. Michel appears only in this fashion, as a tiny shape in the backgrounds of a few shots to establish that the characters have landed on the Normandy coast, but otherwise does not figure in the film.) But I suspect few would guess that the shot illustrated at the bottom was made as early as 1906.

The temptation is to go on and on about Germinal and make a long entry even longer. But Germinal has been the most familiar of Capellani’s films, and I mentioned some writings on it in my first entry. I’ll just make a few remarks about it here.

First, Capellani does a remarkably good job of capturing the naturalism of the Zola novel, as the first frame below suggests. Second, the scenes in the mine convincingly convey a sense of cramped working spaces, despite the need to shoot on sets (second frame below).

The film also makes highly effective use of the giant slag heaps behind the coal fields, placing them in the backgrounds of shots in various locales:

Clearly the resemblance of these neatly squared-off heaps to pyramids did not escape Capellani. (Compare the Red Pyramid at Dashur, above.) I think he intended this to be noticed and to be part of a motif linked to the decor of the mine owner’s study:

Like many rich men in the movies of this era, the owner is characterized as a collector of antiquities and of modern statuary with ancient motifs. (One film shown this year, I forget which, showed a rich man buying such pieces.) A case in the hallway beyond the study presumably houses his real ancient pieces, while his desk sports a small modern statue of a samurai, and the mantelpiece holds a modern Egyptianizing bust of a woman. Capellani was probably intentionally comparing the mine owner to a pharaoh and his workers to the “slaves” who built the pyramids. (This was the view of the time, though the pyramids were in fact built with paid labor.) Such a conceptual use of motifs again marks the sophistication Capellani’s films had reached by the “anna mirabilis” of 1913.

A major step forward since last year is the fact that we now have a reasonably complete print of L’Homme aux gants blancs. As it demonstrates, Capellani can cut in on those rare occasions when it’s necessary (first frame below). Here we need to see the detail of the seamstress fixing a loose button on the new gloves, not just for its own sake but because those gloves will later be lost, found by a thief, and deliberately dropped beside the body of a woman whom the thief kills. The seamstress’ identification of the repaired glove leads to the arrest of the wrong man. In the final shot (second below), the devil-may-care thief, witnessing the arrest, enjoys the irony by holding the door open for a police inspector and handing him his dropped cane. The ending is grim, since the paddy-wagon departs, leaving us to assume that the wrong man will be punished.

I can’t mention all the films shown this year, but two I particularly enjoyed were La Bohème (1911) and Le Signalement (1912), neither of which I can illustrate.

Firstly, this year Capellani’s brother Paul, whom we have seen in smaller roles in previous years, emerged as a fine actor, with perhaps his best work being as Rodolphe in La Bohème. (He played the same role opposite Alice Brady in Capellani’s American feature based on the same story, La Vie de Bohème, in 1916; there the more restrained acting style favored in the U.S. by that point makes his performance less dynamic and affecting.) The familiar tale is compressed but movingly told.

Le Signalement (“The Description”) in some ways echoes the remarkable dramatic twist of the previous year’s L’Épouvante. There a burglar ends by gaining our sympathy, and the suspense during the later part of the film centers not around the frightened heroine but around whether the terrified man will fall to his death. The heroine’s compassion makes for a moving resolution. In Le Signalement, Capellani raises the stakes. A shoemaker and his daughter (granddaughter?) Jeanette, played by the excellent child actor Maria Fromet, live in a French village. The police circulate a flyer describing a child murderer who has escaped from a nearby insane asylum. While delivering some boots, the cobbler is lured to linger in a tavern, and the murderer comes to the house. In characteristic fashion, Capellani lets most of the length of the killer’s time in the house play out in a single take into depth; the camera faces diagonally across the room toward the open door, the only place where help might appear.

When the escapee arrives, Jeannette innocently invites him in and offers him some food, including a dangerous-looking knife to cut a piece of pie. Tempted to kill and yet overwhelmed by the child’s kindness, the man sits and eats. Capellani ups the ante when Jeannette lifts a crying baby, whose presence we had not previously noticed, out of a basket to comfort it, even handing it to the man to rock. During all this we are left in suspense as to whether he will give in to his murderous obsession or resist it. At last the pair hear the police outside, and Jeannette realizes that her visitor is the killer–yet she helps him to escape out the window. Again we are torn, not wanting the child’s generous gesture to be thwarted and yet not wanting a child murderer to run loose! The plot solves the dilemma in a neat and dramatic fashion. Overall, like L’Homme aux gants blanc and L’Épouvante, Le Signalement packs conflicting emotions into a single reel.

Such density of narration is one characteristic of Capellani’s work. As Mariann wrote in the program last year: “Capellani’s speciality as a director is the broad scope of his narratives, connecting different locations and characters, which invests even short films with grandeur and space, to such an extent that the film lengths, given in either metres or minutes, often seem unbelievable. What? Can L’Épouvante really only be 11 minutes long? And Pauvre mère and Mortelle Idylle only 6 minutes each?”

Two final French features

Apparently Capellani made eight films in 1914, but as far as I know, only two survive. Both happen to deal with the French Revolution, and both are based on 19th-Century novels: Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (Dumas) and Quatre-Vingt-Treize (Hugo).

Last year I suggested that Le Chevalier might be a bit of a let-down after the heights of Les Misérables and Germinal. But it would be hard to match Germinal, and I have to admit that upon seeing Le Chevalier again on DVD, it kind of grew on me. The main problem, I think, is that Capellani doesn’t take much trouble to give the characters traits and make them sympathetic. They seem more like game pieces in service to the plot. But as always the staging and acting are marvelous, and both locations and sets, as I suggested above, give a vivid sense of revolutionary Paris.

Oddly, though, for the first time there are signs that Capellani is being influenced by cinematic trends of the day and is trying to expand his style in a somewhat tentative way. Clearly, like so many filmmakers, he has seen Cabiria and been impressed by its lumbering tracking shots. The tribunal near the end where the young lovers, Maurice and Geneviève, are condemned uses such a tracking movement well, pulling out from the lovers and the court to include the crowd that welcomes the death sentences:

In a few scenes Capellani also explores offscreen space in a way that I haven’t seen in his other films. Most dramatically, when Maurice sneaks up to the house where he hopes to see Geneviève, he appears small in the distance, disappears out the bottom of the high-angle framing, and suddenly reappears very close in the foreground, having somehow climbed up to a window:

In one scene Capellani even cuts in for a closer view and a different angle during a letter-writing scene. It’s a bit clumsy, with a mismatch on the man’s position–though not one that is worse than many attempted matches in European cinema of the 1910s:

The cut-in isn’t really necessary, though, and one would expect Capellani not to use it. This is one of the few moments in all the films shown where briefly Capellani seems truly old-fashioned, catching up with a technique that had already been in use for a few years. Here I wish he had stuck to his accustomed long shots, for it’s a sign of things to come. The next year Capellani would be working in the U.S. and making a smooth transition into continuity editing.

Capellani’s last film in France was Quatre-Vingt-Treize. With the outbreak of World War I, the subject matter, French fighting against French during the Revolution, was considered too provocative in a fervently patriotic context, and the film was banned. Capellani did not finish it but went immediately to the U.S. After the war, it was completed by his fellow theatre/film director André Antoine and finally released in 1921. There is no sign of any of the footage being by a different hand or done at a later time. It appears that Antoine simply edited the footage, perhaps to a script or shot list from the director, since the result on the screen is pure Capellani. It eschews the mild experiments of Le Chevalier and returns to a concentration on acting and a wonderful use of locations. At one point, in a single take, a troupe of Revolutionary soldiers marches past in a woodland setting. After they exit, there is a brief pause, and a man rises up from behind the foreground rocks in the path, signaling. Suddenly counter-revolutionary soldiers pop up all over the frame from the undergrowth and follow their foes stealthily in a seemingly unending stream:

In this film the characters are assigned more traits than in Le Chevalier, and the result, even at 165 minutes, is a rattling good tale.

(I mentioned that Capellani avoided dialogue intertitles. This films has some, but it may be that Antoine added those on his own.)

Despite dealing with the same historical period, the two films say nothing about Capellani’s politics, since in Quatre-Vingt-Treize the sympathies are clearly with the Revolutionaries, and in Le Chevalier, they lie with the group, including the title character, who are plotting to rescue Marie Antoinette from prison.

The American period

Given Capellani’s expertise in and long use of the tableau style of filmmaking, it is remarkable how easily he adapted to Hollywood. Only a few of his films from the early years in Hollywood survive, and His La Vie de Bohème (1916), a pleasant, well-made film, is not nearly as lively and absorbing as the French version, La Bohème (1912). I enjoyed the other features shown, Camille (1915, starring Clara Kimball Young) and The Virtuous Model (1919, starring Dolores Cassinelli), but I couldn’t help missing the French Capellani. It is hard to imagine how his career would have developed had he stayed in France. Perhaps, like Victor Sjöström and Ernst Lubitsch, he could have waited until after the war to move smoothly from the tableau style to adopt continuity editing. Perhaps, like them, he could have remained one of the top filmmakers of the silent period. (He returned from Hollywood to France after directing the 1922 Marion Davies vehicle The Young Diana. He did not direct again and died in 1931.) Good though the Hollywood features are, however, for me they inspire none of the sense of discovery and excitement that the films of the 1908 to 1914 period do.

Wishful thinking

By the 2011 festival, most of the known Capellani films have been restored. Some have improved before our eyes. In 2008 and again in 2010, the older restoration of L’homme aux gants blancs (1908) was shown. The newer, more complete restoration combines images derived from a 35mm print and a 28 mm one. A new restoration of Germinal with toning based on original color indications was shown this year.

There were also some fragments, which were saved for the seventh and final program in the series, “Borders and Blind Dates (A Workshop).” There is a version of Le Belle et la bête, for example, that is badly deteriorated, even within most of the footage retained by the restorers. What little remains suggests that the film must have been quite charming; the fragment is included among the extras on the Cineteca di Bologna DVD. There were also some films that were considered as possible Capellanis. According to the booklet accompanying the same DVD, Capellani is thought to have made anywhere from 70 to 80 films from 1905 to 1912. The number is uncertain, due to problems of attribution. Of these, about half survive, less than a third of them from the 1910-1912 period.

La loi du pardon, a 1906 melodrama of the type Capellani frequently made, is listed in the festival catalogue as “Ferdinand Zecca? Albert Capellani?” It could be Capellani, but to me most of his films of the 1906-07 years, though excellent, are not distinctive enough to be attributed to him without any documentation. Manon Lescaut (1912 or 1914; it is listed as both in the program on pages 128 and 129) was more tantalizing. An adaptation from a classic French novel, made by Pathe’s prestigious S.C.A.G.L. unit, would seem exactly Capellani’s sort of project. The first scene, set in an open-air café, seemed plausible as his work, but the rest of the film has little or nothing of his style about it. Instead there is a lack of long-held, intricately staged shots, one completely unnecessary cut-in, and too many old-fashioned painted sets. Compared to the location work in Germinal or just about any of the big films from the immediate pre-war years, these looked crude. Plus, as Caspar Tyberg pointed out to me, the action was staged more quickly than one would expect from Capellani, who often lets situations develop gradually, with many details in the gestures and facial expressions. There are some of his films in archives but apparently as yet unrestored. (According to the booklet accompanying the Coffret Albert Capellani, the Cinémathèque Française has a negative of a 1909 version of Manon Lescaut.) Otherwise I fear we must count on future discoveries in the archives for more Capellani films. Surely some will be forthcoming, now that archivists are aware of the importance of this newly revealed master. “Cento Anni Fa” will move on into 1912, 1913, and 1914, and perhaps the Capellani retrospective will resurface occasionally.

With the end of the main retrospective, however, it is safe to say that from now on anyone who claims to know early film history will need to be familiar with Capellani’s work. If you live outside Europe and don’t already have a multi-region DVD player, this might be the time to invest in one. It would be worth it just to see these new DVDs.

Capellani films shown at Bologna and their availability on DVD

Symbols used in the list:

* A film on the Coffret Albert Capellani, (La Cinémathèque Française, La Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé), Pathé, two four discs with booklet, Region 2 Pal. 36-page booklet in French. There is a bare-bones filmography, with titles and dates, on page 35, but this no doubt will be revised as research continues.

** A film on Albert Capellani: Un Cinema di Grandeur 1905-1911 (La Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé, the Cineteca Bologna) Il Cinema Ritrovato, 1 disc with booklet, Region 2 Pal. Intertitles in various languages; optional subtitles in Italian, French, and English. 55-page booklet in Italian, French, and English.

+ The titles I would most like to see on a future DVD!

In last year’s entry, I expressed the hope that some films from previous years could be repeated. Whether or not that hope influenced the programming, some were.

[Added July 19: Mariann tells me that she is now convinced that La Loi du pardon is genuinely a Capellani film. I find that quite plausible.]

2005

*Le Chemineau (1905)

2006

**La Fille du sonneur (1906)

2007

*Les Deux soeurs (1907)

*Le Pied de mouton (1907)

**Amour d’esclave (1907)

2008

Don Juan (1908)

La Vestale (1908)

*Mortelle idylle (1908)

Corso tragique (1908)

Samson (1908)

**L’Homme aux gants blancs (1908)

Marie Stuart (1908)

2009

*L’Assomoir (1909)

**La Mort du Duc d’Enghien (1909)

2010

Dans l’Hellade (1909)

**Le Pain des petits oiseaux (1911)

*La Fille du sonneur (1906) (Repeated from 2006)

Notre-Dame de Paris (1911)

+Les Miserables (1912)

**Le Chemineau (1905) (Repeated from 2005)

*La Femme du lutteur (1906)

**L’Arlésienne (1908)

Eternal amour (1914)

**L’homme au gants blancs (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

**L’Épouvante (1911)

*Pauvre mère (1906)

**L’Intrigante (1910-11)

La Mariée du château maudit (1910)

**Cendrillon ou la pantoufle merveilleuse (1907)

Samson (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

*Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (1914)

*Drame passionel (1906)

**Le Pied de mouton (1907) (Repeated from 2007)

**La Mort du Duc d’Enghien (1909) (Repeated from 2009)

La Fin de Robespierre (1912)

+La Glu (1913)

The Red Lantern (USA, 1919)

*Mortelle idylle (1906)

+L’Évade des Tuileries (1910)

2011

La Belle au bois dormant (1908)

Le Courrier de Lyon ou l’attaque de la malle poste (1911)

+La Bohème (1912)

La Vie de Bohème (USA, 1916)

*Quatre-vingt-treize (1914, released 1921)

**[Amour d’esclave (1907) Not shown for lack of time]

+Le Signalement (1912)

*L’Âge du Coeur (1906)

**Les Deux soeur (1907) (Repeated from 2007)

Camille (USA, 1915)

*Germinal (1913)

**L’Homme aux gants blancs (1908, more complete restoration)

Le Visiteur (1911)

Marie Stuart (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

Le Luthier de Crémone (1909)

The Feast of Life (USA, 1916)

**La Belle et la bête (1908, fragment) In “Extras” on DVD

Foulard magique (1908, fragment)

Béatrix Cenci (1909, incomplete)

**La Loi du pardon (1909) By Capellani or Ferdinand Zecca

La Legend de Polichinelle (1907)

[August 13, 2012: Roland-François Lack has recently added a post on Capellani on his website, The Cine-Tourist. He gives an extraordinarily detailed run-down of the Parisian (and Vincennes) locales used by Capellani (such as the one below), with many frames from the films and both current and vintage photos of the places, as well as a few maps and some engravings and other graphics. Well worth a look!]

La Fille du sonneur (1906)

Back to the vaults, and over the edge

Unstoppable? Not really. The Juggernaut (1915).

DB here:

A few weeks ago, I praised Variety for making its back issues available digitally. The result is a magnificent vault of information. I also expressed frustration that the recent makeover of The Hollywood Reporter neglected to offer access to its original online archive, which indexed issues across the last twenty years. On the last point, some news.

First, my inquiry to the address listed on the HR website eventually yielded this blue note.

Good Morning,

We apologize for the delayed response.

I do not think there is a way to go back to prior to the changeover.

You would need to contact the publisher about that, as we do not handle the website directly.

Here is a phone number for you 323-525-2150.

Thank you.

I called the number, which handles only subscriptions, and the person answering had no idea what I was asking about.

But all is not lost. My first efforts to access the archive turned up very little for 2010, but shortly afterward I was able to access items from most of this year. Now, if you type a search term into the Search box of the HR site, it brings up items from as far back as 2008. This is an improvement over earlier attempts I made. It seems that THR is gradually adding old material to their archive, in reverse order.

Unfortunately, the search mechanism is quite indiscriminate. Searching “Johnnie To,” with and without quotation marks, yielded 290 hits, but I could find no articles about Johnnie To. Instead, the items with highest relevancy concerned Johnny Depp, Johnny English, John McCain, and the new Narnia movie.

The best news of all came from alert reader David Fristrom of Boston University. He advises me that the old HR archives are still available through LexisNexis. So I tried there with Johnnie To, and I got 338 references, stretching back to 1992. The ones at the top of the relevancy scale were indeed about Mr. To, including a Cannes piece called “Fest’s Red Carpet Flows with Blood.”

Accessing the archive isn’t straightforward, but you don’t need a subscription to HR if your library has purchased access to LexisNexis. I append David’s instructions at the end of this entry. Thanks to him for sorting this out for me.

Now, back into the Variety vaults.

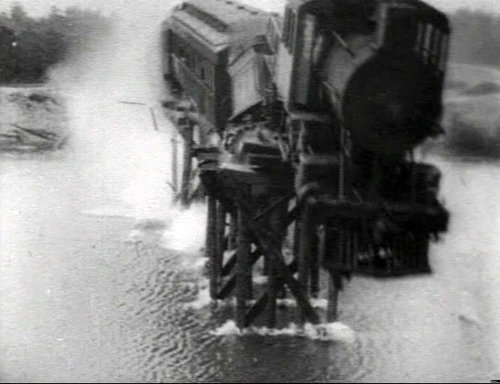

This one’s a real train wreck

On 12 March 1915, Variety reviewed The Birth of a Nation. Alongside that review sits one of The Juggernaut, a Vitagraph feature directed by Ralph Ince. The reviewer, “Simc.,” dwells almost entirely on what he calls “the train-through-the-bridge thing.” The producers bought an old locomotive and some passenger cars, built a flimsy bridge, and ran their train off into what appeared to be a river.

The review exhibits some Variety touches that are still with us. Take the (quite reasonable) idea that nearly every movie is too long. “If this five-reeler were cut down to three reels, which could easily be done, the Vitagraph would have a real thriller.” There’s also the notion that people who come to the see the movie should be aware of its main attraction. “If the audience knows a train will go through a bridge at the finish, it won’t mind the fiddling about in the first four reels before that scene is reached. But if the audience doesn’t know what is to come, there may be many walk-outs.” At the beginning of Unstoppable we’ll sit through all the union and non-union wrangling and alpha-male preening if we’re sure we’re going to see a train that is certifiably unstoppable, except that it’s likely to be stopped by our heroes.

The Juggernaut does give us a pretty spectacular train wreck, as you see above. The entire film may not survive, but we have a version of the last reel (perhaps because a collector thought it worth saving). Train or no train, the film is of interest in showing what Griffith’s rivals were up to.

The plot centers on a crooked railroad magnate, Philip Hardin, and his college friend John Ballard. In the reel we have, Hardin’s daughter Louise, who loves John, sets out on an errand. When her car stalls she boards an express train. A track-walker finds worn ties on a bridge and warns the company, but too late. As Hardin races to stop Louise’s train, it arrives at the bridge and he watches it topple into the water. The sight kills him on the spot. John arrives and swims out to rescue Louise.

That’s when things get dicey. According to the Variety review and other sources, Louise dies in the wreck. Simc again:

The leading woman of the film, Anita Stewart, is discovered dead, lying against one of the windows, with particular pains taken that her features shall be clearly visible. . . . Anita is carried to shore and lain alongside of her father, who had died of heart failure (on land) a few moments before.

In the version available on DVD, John does bring her body ashore, but she revives, lifts herself up, and embraces him. The print ends there. Why the varying ending? Perhaps this is a version made at the time for a different market or in response to censorship, or it might be a rerelease using alternative footage. Or perhaps the press reviews were based on a synopsis supplied by Vitagraph, and the studio made modifications in the print before release.

The Juggernaut is also intriguing stylistically. By this point, crosscutting and scene analysis were common techniques in U. S. films. To set up the perilous situation, the cutting alternates shots of the track-walker, of Hardin, and of Louise. Once Hardin discovers that Louise is on the train headed for the dilapidated trestle, we are set up for a last-minute rescue–which fails. A particularly interesting series of shots shows Hardin’s trajectory converging with the train’s path. Riding in a power boat, Hardin looks back and we get a shot of the train in the distance, suggesting that he can see it.

From this we cut to a shot of Louise, confirming that she’s on board and showing her innocent lack of awareness. Then we get a repeated framing of the train rushing toward the bridge.

After another long shot of the train, we get a shot of Hardin in his powerboat with the train whizzing by in the background. This confirms that he was indeed watching it approach off screen left in the earlier shot, and it shows that he isn’t likely to catch up.

Once the train has toppled into the stream, there are some striking shots of people trapped inside or scrambling to escape. We see Louise raise one hand and then freeze, as if dying.

Earlier, there’s some emphatic “classical” cutting when Hardin learns that Louise is in danger. An enlarged framing (via an axial cut) underscores his reaction to the telegram.

Most striking is a series of shots of the dead-or-not Louise; the abrupt enlargement of her face has something of the force that Kurosawa would channel in his axial cuts.

Soon Ralph Ince cuts back along the same camera axis, and inward again as the couple embrace.

I can’t recall a comparable stretch of “concertina” cutting in the intimate scenes of Birth, and no such tight views of faces either. Griffith sometimes gives us “close-ups within medium-shots” by means of irising and vignetting.

Other directors (e.g., Dreyer) liked to use the serrated surround to highlight faces, but the American norm eventually became the unadorned closer view, as in the shot of Louise in The Juggernaut. Such shots probably saved production time as well. We’re confronted with the familiar situation that sometimes non-Griffith films from 1915 (e.g., The Cheat, Regeneration) look somewhat more “modern” than does Birth.

Going back to the train-through-the-bridge thing, the staging of the scene in late September 1914 elicited a lot of publicity. For one thing, the cost was played up; I’ve seen stories claiming $20,000, $30,000, and $50,000. The New York Times wrote up the shoot twice; the second of these could well be a publicity release from Vitagraph. According to the Times, the “river” was actually a flooded quarry. Before the shoot, buzz leaked out and crowds reported as numbering thousands showed up to watch. The crew spent hours herding them out of camera range. Actors were freezing in the water by the time cameramen got to take their shots. The Times also claims that the crash was filmed by fifteen (or twenty-five) cameras, a stupendously implausible number, especially in light of the footage we have. Worse, according to the second NYT story, Ince decided that the first pass didn’t work and they would have to start all over with a new train! A retake is not mentioned in Variety’s coverage, which does report some studio rivalry:

The ink on the New York dailies telling of the Vita’s big wreck stunt in the cameraing of “The Juggernaut” had hardly dried when the Universal sent over camera men posthaste Sunday to take views of what was left of the wreck. [Vitagraph studio manager Victor Smith], getting a hunch, got on the ground ahead of them and with a sturdy band of Vita “protectors” nipped the U’s little scheme in the bud.

One can only imagine how the “protectors” dealt with the Universal boys. Once more, the Variety Vault gives us the flavor, and perhaps sometimes the facts, of heroic times.

How to access the Hollywood Reporter archive, courtesy David Fristrom:

Once you are in LexisNexis, it can be a little tricky to search in The Hollywood Reporter (for some reason it doesn’t show up if you type “Hollywood Reporter” into the “Source Title” box), but you can follow these steps:

1. Click on “Power Search” in the upper-left corner.

2. On the “Power Search” page, find the “Select Source” box (near the bottom) and click on the “Find Sources” link.

3. On the “Find Sources” page, type “Hollywood Reporter” into the “Keyword” box and press enter.

4. At the top of the results should be “The Hollywood Reporter.”

Check the box next to it, then click on the “Ok-Continue” button that appears in the upper right corner.

5. You are now ready to search in the Hollywood Reporter archives –just type your search terms into the search box.

Thanks again to David!

The Variety review of The Juggernaut appears in the issue of 12 March 1915, p. 23. The story about Universal staff trying to shoot the wreckage is “Vita Putting It Over,” Variety, 10 October 1914, p. 23. The New York Times articles are “Film Train Wreck Almost a Tragedy,” NYT, 28 September 1914, p. 13, and “Tossing Dollars Around As If They Were Pennies,” NYT, 18 October 1914, p. X7. For more on Vitagraph, see Anthony Slide, The Big V: A History of the Vitagraph Company, rev. ed. (Metuchen: Scarecrow, 1987); Tony provides some production background on The Juggernaut on pp. 64-65.

The Juggernaut excerpt is available on Nickelodia 2, a DVD collection from Unknown Video. Oddly, the snapcase doesn’t list the reel as included on the disc, nor does the product information on the Unknown Video site or Amazon. I’d welcome more information about The Juggernaut‘s plot resolution if anybody out there has any.

The Juggernaut (1915).