Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

Art, entertainment, and the hard-boiled mystique

The Maltese Falcon (1941).

DB here:

The traditional opposition between Art and Entertainment still holds some sway. Art, some believe, is the realm of higher significance and profound emotion, while entertainment yields mere diversion and superficial engagement. Art embodies wisdom and technical breakthroughs, while at best entertainment is home to talent and cleverness. Art harbors genius, entertainment offers ingenuity. Art expresses the creator’s personal vision, entertainment recycles collective fantasy (or the Zeitgeist). There’s usually an implied hierarchy of quality and of appeal: art is for a sensitive elite, entertainment is popular (read vulgar).

One problem, though, is that for long stretches of history much art has been thoroughly entertaining. Mozart, Shakespeare, Dickens, Hiroshige, Austen, and many other major artists have found wide popularity. They provide pleasure aplenty. But with urbanization and the rise of capitalism, mass production created a huge public, and tastemakers have tended to treat art as a realm apart. For a hundred years or more, entertainment has been equated with mass culture, and art with high culture, most notably with modernism and its successors.

Another problem is cultural endurance. In a recent column, Michael Dirda points out that genre fiction often outlasts prestigious literary fiction of its era.

Take fantasy and science fiction: In 1997, I praised William Gibson’s “Neuromancer,” John Crowley’s “Little, Big,” Gene Wolfe’s “Book of the New Sun” and the works of Ursula K. Le Guin — all remain vital to contemporary writers and readers.

Similarly, classics of mystery fiction by Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, and Patricia Highsmith still attract readers, while “mainstream” novels of their eras are forgotten. Dirda’s second point is no less valid.

More generally, American novelists have wholly embraced the energy and potential of fantasy in its various forms. We are all fabulists now. This century revels in comics, graphic novels, manga and superhero movies. Authors as varied as Colson Whitehead, Walter Mosley, Kelly Link, Jonathan Lethem, Elizabeth Hand and Michael Chabon, to name a few prominent figures, all grew up loving fantasy and science fiction.

Genre appeals have infiltrated prestige literature, as in the crime plots of Graham Greene, Joyce Carol Oates, and Richard Price. (I consider Colson Whitehead’s and Richard Wright’s contributions here.) Likewise, we have horror-infused tales like George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo and Lorrie Moore’s I Am Homeless if This Is Not My Home .

Creators of entertainment have felt the distinction keenly. “A wedge has been driven into the industry,” says Christopher MacQuarrie, director of the latest Mission: Impossible installment. “Are you an artist or an entertainer? Tom doesn’t see them as mutually exclusive.” But some creators have seen a forking path. Rex Stout, after several “serious” novels failed, came to two conclusions:

First—that I was a good storyteller, and second—that I would never be a great novelist. I’d never be a Tolstoy, or a Dickens, or a Balzac…. So since that wasn’t going to happen, to hell with sweating out another twenty novels when I’d have a lot of fun telling stories which I could do well and make some money on it.

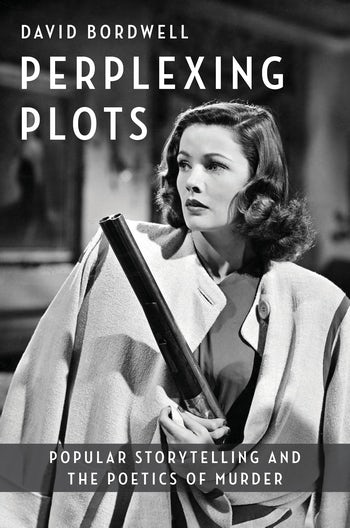

The Art/ Entertainment distinction runs through my recent book, Perplexing Plots, because many mystery writers have aimed at “elevating” their work to the level of prestige literature. This urge drives them to experiment with the norms of plotting and writing. Even when the genre limits remain in force, there’s a chance that skillful exponents can accept them and still yield “literary” pleasures. A good example is what happened to hard-boiled detective fiction in the hands of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler.

The Op

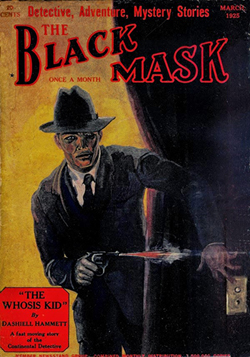

Hammett launched his fame with a series of crime stories mostly published in the pulp magazine Black Mask from 1923 to 1930. His protagonist is a nameless investigator for the Continental Detective Agency. The Continental Op, as he came to be called, is a pudgy but tough middle-aged detective who values camaraderie, crafty stratagems, and a good cheap steak. Women flirt with him, but he sees through their schemes. The Op’s drabness and humility give him a realism that is amplified by the milieu Hammett depicts. He had been a Pinkerton agent and larded the stories with underworld argot and tips on investigative technique.

Hammett launched his fame with a series of crime stories mostly published in the pulp magazine Black Mask from 1923 to 1930. His protagonist is a nameless investigator for the Continental Detective Agency. The Continental Op, as he came to be called, is a pudgy but tough middle-aged detective who values camaraderie, crafty stratagems, and a good cheap steak. Women flirt with him, but he sees through their schemes. The Op’s drabness and humility give him a realism that is amplified by the milieu Hammett depicts. He had been a Pinkerton agent and larded the stories with underworld argot and tips on investigative technique.

Black Mask stories put a premium on action, so the Op was often at the center of violence perpetrated by crooks, sociopaths, and corrupt cops. Unlike other hard-boiled detectives, the Op isn’t a swaggering sadist. Violence is his last resort; he favors obstinate everyday professionalism. Sometimes he’s fooled by the grifters and has to wriggle his way out. At other times, he can set crooks against one another and watch the mutual destruction.

Hammett wrote the stories in the first person, giving the Op a telegraphic, visceral style laced with sour humor. A 1923 story shows his American vernacular already in place.

Just at the wrong minute Henderson decided to look over his shoulder at us–an unevenness in the road twisted his wheels–his machine swayed–skidded–went over on its side. Almost immediately, from the heart of the tangle, came a flash and a bullet moaned past my ear. Another. And then, while I was still hunting for something to shoot at in the pile of junk we were drawing down upon, McClump’s ancient and battered revolver roared in my other ear.

Henderson was dead when we got to him–McClump’s bullet had taken him over one eye.

McClump spoke to me over the body.

“I ain’t an inquisitive sort of fellow, but I hope you don’t mind telling me why I shot this lad.” (“Arson Plus”)

In 1929, the publisher Knopf issued two Hammett novels, Red Harvest and The Dain Curse, based on Black Mask serials. The Op had not lost his wit or his gift for staccato narration. Here are three excerpts.

I didn’t think he was funny, though he may have been.

He stood at the foot of the bed and looked at me with solemn eyes. I sat on the bed and looked at him with whatever kind of eyes I had at the time. We did this for nearly three minutes.

The latch clicked. I plunged in with the door.

Across the street a dozen guns emptied themselves. Glass shot from door and windows tinkled around us.

Somebody tripped me. Fear gave me three brains and half a dozen eyes. I was in a tough spot. Noonan had slipped me a pretty dose. These birds couldn’t help thinking I was playing his game.

I tumbled down, twisting around to face the door. My gun was in my hand by the time I hit the floor.

Across the street, burly Nick had stepped out of a doorway to pump slugs at us with both hands. I steadied my gun-arm on the floor. Nick’s body showed over the front sight. I squeezed the gun. Nick stopped shooting. He crossed his guns on his chest and went down in a pile on the sidewalk.

Hands on my ankles dragged me back. The floor scraped pieces off my chin. The door slammed shut. Some comedian said:

“Uh-huh, people don’t like you.”

As he was finishing The Dain Curse, Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf confessing that in future work he wanted to go beyond Entertainment to Art.

I’m one of the few—if there are any more—people moderately literate who take the detective story seriously. I don’t mean that I necessarily take my own or anybody else’s seriously—but the detective story as a form. Some day somebody’s going to make “literature” of it (Ford’s Good Soldier wouldn’t have needed much altering to have been a detective story), and I’m selfish enough to have my hopes, however slight the evident justification may be.

The question is: How to do this?

Inside and outside

Hammett proposed an answer in his letter to Blanche Knopf. He wanted to try that he wanted to try out modernist technique in a third novel.

I want to try adapting the stream-of-consciousness method, conveniently modified, to the detective story, carrying the reader along with the detective, showing him everything as it is found, giving him the detective’s conclusions as they are reached, letting the solution break on both of them together. I don’t know whether I’ve made that very clear, but it’s something altogether different from the method employed in “Poisonville [Red Harvest],” for instance, where, though the reader goes along with the detective, he seldom sees deeper into the detective’s mind than dialogue and action let him.

His mention of stream of consciousness may mislead us about his intentions. In that technique the verbal narration seeks to mimic the flow of the mind as it flits across sensory impressions, memories, and fantasies. The process is often rendered as sentence fragments, often introduced by a sentence indicating the behavior of the character.

Here’s an example from Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), the most famous showcase of stream of consciousness. Mr. Bloom is in a Catholic church.

He saw the priest stow the communion cup away, well in, and kneel an instant before it, showing a large grey bootsole from under the lace affair he had on. Suppose he lost the pin of his. He wouldn’t know what to do to. Bald spot behind. Letters on his back I.N.R.I? No: I.H.S. Molly told me one time I asked her. I have sinned: or no: I have suffered, it is. And the other one? Iron nails ran in.

Sometimes the images and phrases are separated by commas and periods, but sometimes they simply pile up. In the book’s last chapter, Molly Bloom’s drowsy imaginings are given in an unpunctuated, sparsely paragraphed flow.

It’s likely that Hammett didn’t want his usage to be as fragmentary as what we encounter in Joyce and others. His invocation of Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier (1915) suggests something closer to what many now call inner monologue. (Ford called it “impressionism.”) Here the flow of thought is given as a sort of soliloquy, a flow of more or less cogent and coherent ideas and impressions. What makes it a modernist technique is that inner monologue may not respect story chronology and it’s likely to be biased, uncertain, equivocal, and subject to revision. Ford’s narrator, John Dowell, tells a rambling, out-of-order tale of marital infidelity and suicide, in which flashbacks are analyzed and re-analyzed.

Looking over what I have written, I see that I have unintentionally misled you when I said that Florence was never out of my sight. Yet that was the impression that I really had until just now. When I come to think of it she was out of my sight most of the time.

At the climax, Dowell makes a provisional sense of what the characters knew and why they acted as they did.

The problem in importing this to the detective story is evident. How can the detective’s ongoing reasoning, bristling with mistaken inferences and reconstructed impressions, be passed along to the reader without causing confusion? For this reason, detective story narration, whether first-person or third-person, suppresses most of the protagonist’s reasoning. The Watson figure and the dumb authorities exist to be baffled and play with misleading possibilities while the detective holds back even a partial solution.

By convention, the climax of the tale is the revelation of the truth–not when the detective discerns it, but at the moment when it can be announced with decisive impact (often in a gathering of suspects with the police present). Raymond Chandler noted that the delayed revelation was a serious constraint of the genre, even when the detective, like the Op, is telling the story. “The first person story is assumed to tell all but it doesn’t. There is always a point at which the hero stops taking the reader into his confidence.” The detective “stops thinking out loud and ever so gently closes the door of his mind in the reader’s face.” This prevents the public announcement of the solution from being anticlimactic.

Worse, Ford’s protagonist Dowell is an unreliable narrator, as the above passage suggests. To make the detective’s first-person account unreliable would be more than a “convenient modification” of the standard plot schema. It would push toward the experiments seen in Cameron McCabe’s The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor (1937) and later “anti-mysteries.”

Hammett admitted in a later letter that he would put the “stream-of-consciousness” experiment on hold while he wrote material for Hollywood in “more objective and filmable forms.” (That would include his script for City Streets of 1931, which does include a subjective auditory flashback rare in films of the time.) But in his next novels Hammett turned sharply away from the interiority he had considered. Instead, he went toward extreme objectivity, almost completely shutting us out from his protagonists’ inner lives.

The action of The Maltese Falcon (1930) and The Glass Key (1930) attach us closely to his protagonist, scene by scene. We’re confined to his activity and his range of knowledge. But this doesn’t get us into his mind. For these books Hammett switched to third-person narration and made it radically objective, sticking almost completely to reporting dialogue and character interaction.

In Perplexing Plots, I explore how this strategy works, but here’s an example from The Glass Key.

At Madison Avenue a green taxicab, turning against the light, ran full tilt into Ned Beaumont’s maroon one, driving it over against a car that was parked by the curb, hurling him into a corner in a shower of broken glass.

He pulled himself upright and climbed out into the gathering crowd. He was not hurt, he said. He answered a policeman’s question. He found the hat that did not quite fit him and put it on his head. He had his bags transferred to another taxicab, gave the hotel’s name to the second driver, and huddled back in a corner, white-faced and shivering, while the ride lasted.

The narration presents what a third-person observer would have seen and heard, and it won’t venture into Beaumont’s thinking. The cues are behavioral: he seems cool enough in slipping out of the crash, but his true reaction is given through his nervous reaction while riding back to the hotel.

As Hammett’s second letter to Blanche Knopf suggests, this flat objectivity would seem an ideal novelistic basis for a “filmable” treatment. John Huston’s screen adaptation of The Maltese Falcon confines us almost completely to Spade’s range of knowledge. (The big exception is that we see his partner Miles Archer shot by an unknown killer.) The film’s visual narration mostly follows Hammett’s impassive neutrality. But when Casper Gutman drugs Spade, we get Spade’s clouded optical viewpoint.

In the novel the narration reports that Spade’s eyes seemed to muddy over. When he says, “And the maximum?” we’re told that “An unmistakable sh followed the x in maximum as he said it.” This isn’t Spade’s experience but rather what an observer would register, an “unmistakable” impression confirmed when we’re told that “a sharp frightened gleam awoke in his eyes.” As Spade tries to walk, he’s tripped by Wilmer. He falls and Wilmer kicks him. “Once more he tried to get up, could not, and went to sleep.” The whole scene is rendered externally.

So instead of giving the detective story a modernist subjectivity, Hammett went to the other extreme. Did he intuitively recognize the problem of revealing the detective’s inferences too soon? Maybe, although his increasing involvement with Hollywood may have kept him on the objective, “filmable” path. The Thin Man (1934), his last novel, is a fascinating effort to return to first-person narration while incorporating the dry objectivity of the two previous books.

Perhaps inadvertently, Hammett’s radicalization of the objective method yielded what he had hoped for. The Maltese Falcon was greeted as a serious work of literature and was soon incorporated into the prestigious Modern Library series. His works have become part of the canon of American letters enshrined in the Library of America collection. The convention of delaying the detective’s solution didn’t prevent the genre from becoming accepted as a legitimate literary form–at least as practiced by Hammett, and his most prominent successor.

Overtones, echoes, images

That successor was, of course, Raymond Chandler. Ten years after Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf with his hopes of elevating the whodunit, Chandler wrote to Alfred Knopf about his plans for The Big Sleep (1939) and the novels that followed. It has an echo of Hammett: “I was more intrigued by a situation where the mystery is solved by the exposition and understanding of a single character, always well in evidence, rather than by the slow and sometimes long-winded concatenation of circumstances.”

That successor was, of course, Raymond Chandler. Ten years after Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf with his hopes of elevating the whodunit, Chandler wrote to Alfred Knopf about his plans for The Big Sleep (1939) and the novels that followed. It has an echo of Hammett: “I was more intrigued by a situation where the mystery is solved by the exposition and understanding of a single character, always well in evidence, rather than by the slow and sometimes long-winded concatenation of circumstances.”

But what Chandler means by “understanding” doesn’t include full-blown reasoning. First-person narration, he explains in a 1949 note, must “suppress the detective’s ratiocination while giving a clear account of his words and acts and many of his emotional reactions.” This seems a response to the detached reportage of late Hammett prose. Chandler also rejects the Op’s streetwise patter by explaining to Knopf that his method will use “a very vivid and pungent style, but not slangy or overtly vernacular.” He wants “to acquire delicacy without losing power.”

Hammett, while a voracious reader, learned a good deal of his craft from actually investigating crimes. Chandler, who began writing mysteries as Hammett’s productivity tailed off, owed his knowledge of the mystery genre to reading. He studied crime fiction of all sorts with almost academic passion and became one of the most nuanced commentators on the tradition. He claimed to have learned plotting from outlining pulp stories by Erle Stanley Gardner. His literary tastes didn’t run to modernism. He admired the Greek and Roman classics, Flaubert, James, and Conrad and thought highly of Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Hammett imagined elevating the genre by “conveniently modifying” modernist technique, but Chandler sought to make the hard-boiled detective story more like the ambitious mainstream novel.

He believed he could do that through style. In his crucial essay, “The Simple Art of Murder (1944/1946),” he praises Hammett’s prose but objects that “it had no overtones, left no echo, evoked no image beyond a distant hill.” Chandler sought to give style a greater novelistic richness not only through probing his protagonist’s mind but also through fairly dense descriptions colored by the protagonist’s emotions and judgments.

Hammett sketches characters in quick strokes and he merely indicates settings. But Chandler dwells on his characters and their surroundings. The opening of The Big Sleep devotes a page and a half to Philip Marlowe’s impressions of the Sternwood mansion (stained-glass window of a knight rescuing a lady, plush chairs, a mysterious portrait) and another page and a half to his meeting with the coy Carmen. These are filtered through Marlowe’s running commentary. The knight doesn’t really seem to be trying. The chairs appear to never have been sat in. The portrait looks threatening. Carmen’s infantile flirtation reveals that “thinking was always going to be a bother to her.” Here are the overtones and echoes that Chandler finds lacking in Hammett. This is an ominous household–as Marlowe will later say, this will be “no game for knights.”

Chandler would pursue this method in the following novels. Yet at times the narration plunged deeper into subjectivity. In Farewell, My Lovely (1940) Marlowe is repeatedly knocked out in tussles, and in the second passage Chandler writes:

The man in the back seat made a sudden flashing movement that I sensed rather than saw. A pool of darkness opened at my feet and was far, far deeper than the blackest night.

I dived into it. It had no bottom.

The film adaptation, titled Murder, My Sweet (1944), uses this subjective device in every knockdown. Marlowe’s voice-over narration runs through the film, and after the first assault we hear:

I caught the blackjack right behind my ear. A black pool opened up at my feet. I dived in. It had no bottom.

Onscreen we see Marlowe’s crumpled body blotted out by a miasma that leads to a black frame.

In a later sequence, a knockout of Marlowe is rendered as wild optical exaggerations before following the novel’s report of Marlowe seeing a room full of smoke. That’s translated as wispy superimpositions over the shots, with explanatory voice-over.

The film tries a bit too hard, but its use of voice-over and delirious visual subjectivity would become common in film noirs of the period.

In Farewell, My Lovely, Marlowe’s recovery from his first knockout is rendered with vigorous subjectivity across two pages, as Marlowe realizes that the voice he hears reviewing what happened is his own. “I was talking to myself, coming out of it. I was trying to figure the thing out subconsciously.”

Marlowe is able to reconstruct bits of the crime through this process, but it’s a provisional solution, not the decisive one. That one he keeps from the reader until the climax. By then, as per convention, the door to his mind has shut in the reader’s face.

Hammett’s novels were published when most crime fiction consisted of genteel whodunits and gangster sagas, so he had the advantage of novelty. By the time Chandler published The Big Sleep, he was competing with many book-length stories of hard-boiled investigators. Aware of the need to establish a distinctive presence, he presented work that stood apart by its social criticism and the romanticized realism of a righteous avenger alone on the mean streets of a corrupt city–sure-fire attractions to intellectuals then and since. Just as important was his self-consciously literary style. “In the long run, however little you talk or even think about it, the most durable thing in writing is style, and style is the most valuable investment a writer can make with his time.”

Through concern with language’s echoes and overtones, he established himself as Hammett’s successor. The literati followed his lead and declared him a significant novelist. His books, along with “The Simple Art of Murder,” provided an enduring rationale for the tough detective story. While adhering to the conventions of the classic puzzle (clues, faked deaths, false identities, least-likely culprit), he acquired lasting prominence. Like Hammett he has found a home in the Library of America.

Arguably Hammett and Chandler also elevated their genre. Their achievements encouraged other ambitious writers and stimulated critics and readers to look more closely at the possibilities of the murder novel. No wonder that prestigious writers have turned to mystery plots. Fans still labor to make a case for Golden Age puzzles as art rather than entertainment, but most critics and readers assume the hard-boiled mystery to be at least potentially serious literature–especially when it goes under the alias “noir.”

Nowadays the Art/ Entertainment duality has weakened its hold. If, as Dirda suggests, we are all fabulists now, we’re also probably mystery fans to some degree. It’s likely that film played a role in dissolving the duality. Intellectuals began to understand that films by Ozu, Hitchcock, and other popular directors were of high quality. More and more, I think, people aren’t as eager to see the split as absolute. Instead of a hierarchy, we have more of a spectrum.

In harmony with this, Perplexing Plots argues that culture offers us a plenitude of individual works with varied appeals, all of which can be realized with, to use Chandler’s terms, delicacy and power. Some works rely on subtlety, others on immediate impact. We have the refinements of Baroque music and the direct force of The Rite of Spring. If Treasure Island is a masterpiece as well as a rousing yarn, so is Die Hard. There is heavy art and light art, brooding art and and diverting art, intellectual density and emotional charm. None of these qualities is simple or easy to achieve; all can repay analysis. The slogan might be: “There’s valuable work at all levels. And there are no levels.”

One source of value, not always acknowledged, is the role of entertainment in revealing fresh expressive possibilities in the medium. For example, the martial arts cinemas of Japan and Hong Kong opened up new vistas of cinema. And yes, as Hammett and Chandler indicated, a lot of the freshness lies in style. This is why Perplexing Plots spends time looking closely at how mystery fiction and film work, word by word or shot by shot. Even Agatha Christie’s supposedly bland verbal texture points up ways in which language can mislead us.

So Hammett and Chandler didn’t “elevate” the hard-boiled story so much as blur the line between genre fiction and the “legitimate” novel. Ambler and Le Carré did the same for the spy story, as did Highsmith for the psychological thriller. For such reasons, Perplexing Plots discusses hard-boiled detection extensively. I explore the Art/ Entertainment distinction because it has obsessed critics and creators. But I try not to buy into the split, opting instead for the looser idea of “crossover.” It’s a swap meet, with storytellers ransacking works “high” and “low” for subjects, forms, techniques, whatever.

I wanted to put up this entry on 23 July, Raymond Chandler’s birthday. It happens to be mine too. No cheerleading here, though. I prefer Hammett, as maybe you can tell.

My quotations from Hammett’s letters come from Selected Letters of Dashiell Hammett, 1921-1960, ed. Richard Layman and Julie Rivett (2002). I take Chandler’s remarks on mystery fiction from Selected Letters of Raymond Chandler, ed. Frank MacShane (1981) and Raymond Chandler Speaking, ed. Dorothy Gardiner and Katherine Sorley Walker (1962).

Michael Dirda, as my mentions of him should lead you to expect, has written an admirable example of taking popular storytelling seriously but not solemnly: On Conan Doyle, or the Whole Art of Storytelling (2014). Kristin does something similar in her Wooster Proposes, Jeeves Disposes, or Le Mot Juste (1992), available here and here. Her immensely popular subject, P. G. Wodehouse, was regarded as a master of English prose by Martin Amis, Evelyn Waugh, and many other literary celebrities.

What about the third celebrated hard-boiled pioneer, Ross Macdonald? Read Perplexing Plots to find out!

Murder My Sweet (1944).

P.S. 11 October 2023: In a Slate essay, Dan Sinykin shows that the merging of “genre fiction” and “literary fiction” has causes in the economics of the publishing industry. A fine analysis I wish I’d had available for Perplexing Plots.

Ellery who?

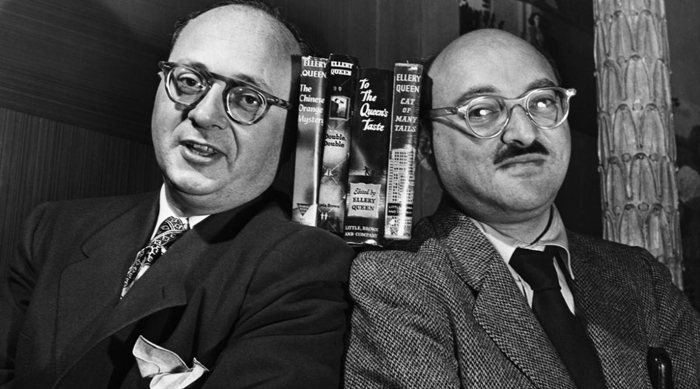

Manfred Lee and Frederic Dannay.

DB here:

My new book, Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder, offers many critical discussions of classic mystery writers. But I couldn’t include every writer or work that interested me. So occasionally I’ll post blog entries that will fill in areas I skipped over. Some portions of the book analyzed work by Ellery Queen, but here I want to fill in some gaps–and remind contemporary readers of two writers who deserve more attention than they currently attract.

Many best-selling novels of the 1930s and 1940s in America remain familiar to us, if only because movies were made from them: Gone with the Wind, The Good Earth, Lost Horizon, The Grapes of Wrath, Mrs. Miniver, The Robe, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Forever Amber, The Razor’s Edge, The Naked and the Dead, and others. Maybe you’ve even read some of the books. But many best-sellers don’t endure. What about Singing Guns (Max Brand), Fast Company (Marco Page), Earth and High Heaven (Gwethalyn Graham), and The Forest and the Fort (Hervey Allen)?

Many best-selling novels of the 1930s and 1940s in America remain familiar to us, if only because movies were made from them: Gone with the Wind, The Good Earth, Lost Horizon, The Grapes of Wrath, Mrs. Miniver, The Robe, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Forever Amber, The Razor’s Edge, The Naked and the Dead, and others. Maybe you’ve even read some of the books. But many best-sellers don’t endure. What about Singing Guns (Max Brand), Fast Company (Marco Page), Earth and High Heaven (Gwethalyn Graham), and The Forest and the Fort (Hervey Allen)?

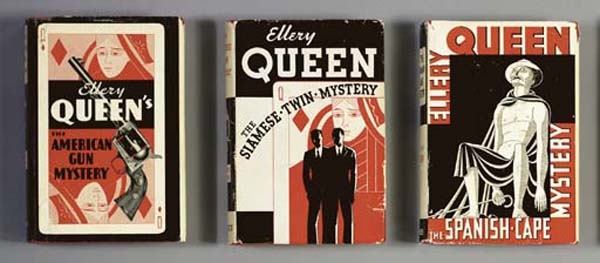

In particular, what about The Dutch Shoe Mystery, The Egyptian Cross Mystery, The Chinese Orange Mystery, and The New Adventures of Ellery Queen? Each of these had sold over 1.2 million copies by 1945. Scarcely anyone today remembers them, or recognizes their author’s name.

Yet eighty years ago they were part of a multimedia franchise. The books bearing the “Ellery Queen” byline were said to have sold over ten million copies by the end of World War II. There was a spinoff juvenile series by “Ellery Queen, Jr.” and some comic books. There were nine Ellery Queen films and a weekly radio series that ran sporadically from 1939 to 1948, along with “Ellery Queen’s Minute Mysteries.” The Queen name adorned countless anthologies of mystery short stories, and Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, still the most prestigious venue for short mystery fiction, was founded in 1941. You couldn’t visit a newsstand or bookstore without seeing the Queen name.

“Ellery Queen” was the pseudonym of two Brooklyn cousins, Frederic Dannay (né Daniel Nathan) and Manfred B. Lee (né Emanuel Benjamin Lepofsky), both born in 1905. While working in advertising, they collaborated on a mystery novel they submitted for a magazine prize. It won, but the magazine went out of business, so The Roman Hat Mystery was brought out as a book in 1929. Dannay and Lee took up detective fiction in earnest, turning out at least one book a year during the 1930s.

Sensitive to the power of PR, they built up the enigma of the author’s identity, with one or the other sometimes giving a lecture in a mask. When they started another series as by “Barnaby Ross,” the two would appear masked and debate one another. (Shamelessly, Queen wrote a newspaper article praising a Ross novel.) By 1939, they embraced radio and films as major vehicles for their brand, and so their pace of book publishing slackened while they churned out screenplays and radio scripts.

Sensitive to the power of PR, they built up the enigma of the author’s identity, with one or the other sometimes giving a lecture in a mask. When they started another series as by “Barnaby Ross,” the two would appear masked and debate one another. (Shamelessly, Queen wrote a newspaper article praising a Ross novel.) By 1939, they embraced radio and films as major vehicles for their brand, and so their pace of book publishing slackened while they churned out screenplays and radio scripts.

Construed most narrowly, the Queen reign lasted from 1929 to 1958, with The Finishing Stroke taking us back to the days of the first novel. The cousins’ biggest bestsellers were 1930s titles reissued during the 1940s boom in paperbacks. Thereafter they were beset by money troubles and poor health, and so were forced to keep turning out product.

After 1958 the result was a bewildering array of books of varying authorship. Lee had a spell of writer’s block, while publishers pressed them for less detection and more straight crime. Ghost writers produced non-Ellery mysteries under the Queen name and historical novels under the Ross pseudonym. Dannay plotted one novel written by a ghost, while Lee was able to rejoin him for other novels such as Face to Face (1967) and their last joint effort A Fine and Private Place (1971). After Lee died in 1971 and Dannay’s wife died a year later, Dannay brought the series to a close.

For many years the books were out of print, but Otto Penzler, always vigilant for ways to keep the great traditions alive, began bringing out uniform editions (including the ghost-written books) in 2018. Before that, probably the most vivid reminder of the saga was the NBC television series of 1975-1976, starring Jim Hutton and David Wayne. I’ve been surprised by the number of people who remember it fondly. But the books? Not so much. Which is a pity.

From cold logic to social comment

In his definitive Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection, Francis M. Nevins has argued that the saga develops in four phases. First, there are the pure puzzles–complex crimes demanding elaborate solutions. (Hence the titles flaunting the “mystery” of this or that.) The stories abide strictly by the fair-play principles articulated in Golden Age precept: a careful reader should have all the information necessary to solve the case. The novels flaunted this premise with the famous “Challenge to the Reader” inserted before each climax.

As befits puzzle plots, Phase 1 presents Ellery as a drawling, bloodless intellectual, flaunting his erudition in the manner of the then-popular and more insufferable Philo Vance of S. S. Van Dine. At the same time Lee and Dannay establish some of the devices they’ll use again and again. We encounter cryptic dying messages, missing clues (the dog that doesn’t bark in the nighttime), tempting false solutions, and murderers with a penchant for elaborate crimes. Dannay’s plotting is intricate, but the clarity of Lee’s prose (and his willingness to repeat information) helps the whole contraption work.

As the early books go along, Ellery becomes somewhat less priggish, but he gets quite down to earth in Phase 2, at the end of the 1930s. The plots loosen up, Ellery gains a (mild) sex life, and the romantic escapades of secondary couples occupy more space. Why? Mystery writers were discovering that serializing or condensing their novels in slick-paper magazines could yield big financial rewards. This market, aimed chiefly at women and families, discouraged the pure puzzle and urged more emphasis on characterization. The cousins managed to sell The Devil to Pay (1938) and The Four of Hearts (1938), intrigues set in Hollywood, as condensations to Cosmopolitan.

As the early books go along, Ellery becomes somewhat less priggish, but he gets quite down to earth in Phase 2, at the end of the 1930s. The plots loosen up, Ellery gains a (mild) sex life, and the romantic escapades of secondary couples occupy more space. Why? Mystery writers were discovering that serializing or condensing their novels in slick-paper magazines could yield big financial rewards. This market, aimed chiefly at women and families, discouraged the pure puzzle and urged more emphasis on characterization. The cousins managed to sell The Devil to Pay (1938) and The Four of Hearts (1938), intrigues set in Hollywood, as condensations to Cosmopolitan.

Phase 3 Queen, throughout the 1940s and early 1950s, is generally considered the pinnacle of the series. Endowed with literary ambitions and a range of cultural references, the books showed a new depth of psychological, political, and social sensitivity. In the space I have today, I pick out my favorites, each of which has been considered by one critic or another as Queen’s best. Among their distinctions, they show Dannay experimenting with what we would call “worldmaking” and Lee exploring new stylistic resources. All make invigorating reading today.

“Mr. Queen Discovers America” is the title of the opening chapter of Calamity Town (1942). Ellery gets off the train in Wrightsville, a small New England town. He has come to find a quiet place to write his next novel, and Wrightsville’s apple-pie ordinariness makes it the ideal sanctuary. It’s apparently as pure as the Grover’s Corners of Wilder’s play Our Town (1938) and the idealized Carville of the Andy Hardy movies; the same folksy milieu would figure in William Saroyan’s Human Comedy (book and film, 1943). Ellery manages to rent a house next to the town’s first family, the Wrights, and he’s taken into their social circle.

Quickly the novel activates another motif of American popular culture: the sinister forces that seethe underneath a small town’s cheery surface. This runs back to Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology (1915) and Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (1919) right up to Blue Velvet (1986) and TV shows like Twin Peaks and Fargo. In Calamity Town, the Wrights’ household is disrupted by the return of one daughter’s runaway fiancé and the couple’s sudden marriage. But soon murder intervenes and vicious gossip swallows up the family in scandal. At the end of the book, Ellery reflects, “There are no secrets or delicacies, and there is much cruelty, in the Wrightsvilles of this world.” The Wright family is shattered, and the shocking solution forces Ellery to realize he could have prevented a murder consummated before his eyes.

the novel activates another motif of American popular culture: the sinister forces that seethe underneath a small town’s cheery surface. This runs back to Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology (1915) and Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (1919) right up to Blue Velvet (1986) and TV shows like Twin Peaks and Fargo. In Calamity Town, the Wrights’ household is disrupted by the return of one daughter’s runaway fiancé and the couple’s sudden marriage. But soon murder intervenes and vicious gossip swallows up the family in scandal. At the end of the book, Ellery reflects, “There are no secrets or delicacies, and there is much cruelty, in the Wrightsvilles of this world.” The Wright family is shattered, and the shocking solution forces Ellery to realize he could have prevented a murder consummated before his eyes.

In plotting the book, Dannay provided Lee a panorama wider than they had used before. Calamity Town has dozens of named characters, mostly serving as local color but many playing important roles. The mystery itself is less complex than those in Phase 1, but the book is filled out with a cross-section of life in Wrightsville. Low Village is populated by:

people named variously O’Halleran, Zimbruski, Johnson, Dowling, Goldberer, Venuti, Jacquard, Wladislaus, and Broadbeck–journeyman machinists, toolers, assembly-line men, farmers, retailers, hired hands, white and black and brown, with children of unduplicated sizes and degrees of cleanliness. . . . Mr. Queen’s notebook was rich with funny lingos, dinner-pail details, Saturday-night brawls down on Route 16, square dances and hep-cat contests, noon whistles whistling, lots of smoke and laughing and pushing, and the color of America, Wrightsville edition.

This Capraesque vision of vibrant Americana, coming early in the book, is questioned immediately by Lola, the renegade Wright daughter, who calls her town “wormy and damp, a breeding place of nastiness.” Lee’s task is to show both sides of Wrightsville through incidents tracing the town’s reaction to the murder. Ellery is always captivated by the calendar-image look of the place, as when in winter it resembles a Grant Wood painting.

But in town there were people, and sloppy slush, and a meanness in the air; the shops looked pinched and stale, everybody was hurrying through the cold; no one smiled. In the Square they had to stop for traffic; a shopgirl recognized Pat and pointed her out with a lacquered fingernail to a pimpled youth in a leather storm-breaker.

Lee rose to the challenge of portraying the fragility of a social network that can’t respond to a shock to placid lives.

The result is the most wide-ranging and emotionally complex book in the Queen franchise so far. The cousins were unable to sell it for serialization, and from then on, no slick magazines bought a Queen novel for many years.

Class relations and inner turmoil

The Murderer is a Fox (1945) takes Ellery back to Wrightsville, but under very different circumstances. Pilot Davy Fox is welcomed back home for his outstanding record in killing the enemy and rescuing his comrades. But like many a returning vet he has PTSD, which emerges as an urge to strangle his wife Linda. The couple consult Ellery, who speculates that Davy is haunted not just by his combat experiences but by the fact that his father Bayard was imprisoned for poisoning his mother.

In order to investigate the case, Ellery persuades the authorities to release Bayard under supervision. He must answer the question: Who poisoned the grape juice that Jessica Fox drank–and shared with others–on the fateful day? Suspects include Bayard’s brother Talbot, his wife Emily, a duplicitous pharmacist, an overbearing cop, and a few others. Dannay’s plotting is intensely focused on a middle-class family quite different from the patrician Wrights, and Lee’s problem is to fill out a fairly minimal situation to novel length.

In order to investigate the case, Ellery persuades the authorities to release Bayard under supervision. He must answer the question: Who poisoned the grape juice that Jessica Fox drank–and shared with others–on the fateful day? Suspects include Bayard’s brother Talbot, his wife Emily, a duplicitous pharmacist, an overbearing cop, and a few others. Dannay’s plotting is intensely focused on a middle-class family quite different from the patrician Wrights, and Lee’s problem is to fill out a fairly minimal situation to novel length.

Lee’s solution is to recast his narrational approach, turning the book’s first section into a suspense thriller. For once our viewpoint isn’t initially attached to Ellery. The opening chapters alternate the Fox family awaiting Davy’s train with scenes of Davy on board. All the scenes are deeply subjective, with flashbacks plunging us into the family background and, more harrowingly, Davy’s war experiences. The seamy side of Wrightsville is exposed again and again. Against the bunting and chattering crowd of the train-station homecoming welcome, with the American Legion band “tossing the sun from their silver helmets,” Lee replays Davy’s memories of his father’s shame.

How Davy loathed them, the jeering kids. Because they had known, the whole town knew. The kids and the shopkeepers in High Village and the Country Club crowd and the scrubskinned farmers who drove in on Saturdays to load up–even the hunks and canucks who worked in the Low Village mills. Especially the shop hands of Bayard & Talbot Fox Company, Machinists’ Tools, who merely jeered the more after the Bayard & one day vanished from the side of the factory, leaving a whitewashed gap, like a bandage over a fresh wound.

Asked on the train about the thrills of battle, Davy conjures up:

Being caught on the ground with Zeros twisting and tumbling all over the sky and falling flat on your face in the stinky guck of a Chinese rice field, or pulling Myers out of his cockpit with his stomach lying on his knees after he brought his old P-40 down only God knows how. . . . Having your coffee grinder conk in the middle of a swarm of bandits and belly-landing in scrub on the knife-edged hills–seeing Lew Binks’s coffin drop like lead aflame, and Binks hitting the silk, trustful guy, and then the hornet Japs zapping around him with their spiteful traces hemstitching the sky.

Obliged to evoke the war, Lee summons up a muscular, sometimes lyrical prose unknown in the books of Phases 1 and 2.

Davy’s trauma turns the early chapters into an account of a man driven to murder. Like other novels and films of the 1940s, The Murderer is a Fox shares his nightmares and dissects his compulsion. While a loving, confused Linda tries to lure Davy into an embrace, he struggles to keep away from her.”The game was to stay in his bed. To stay in his bed so that he would not go over to the other bed and obey the prickling of his thumbs. . . . “

The viewpoint shifts to Ellery once he starts to reconstruct how Jessica might have died. In the course of this, family indiscretions are exposed and characterization deepens. In particular, Bayard is revealed as a man of severe principle, who stoically accepts a life sentence of murder. Revealing the true cause of Jessica’s death leads Ellery to a conclusion that could become another Wrightsville scandal. The book ends with Ellery smiling grimly at the prospect of one secret that the town gossip will never exhume.

In Phase 3, Dannay indulged his penchant for elaborate “pattern mysteries,” crimes based on cultural givens like the alphabet, dates of the year, nursery rhymes, and the like. But this ploy demands either a madman (driven by obsession with the pattern) or a super-schemer. Knowing that the pattern would attract the hyperintellectual Ellery, the schemer could then frame someone else as being enslaved to it. Ellery will then confidently call out the wrong suspect, with sometimes dire consequences.

This tendency toward a master-mind, an omniscient “player on the other side,” is at the center of Ten Days’ Wonder (1948). Now a new layer of Wrightsville society is peeled back. Plutocrat Diedrich Van Horn is an industrialist who has indulged his son Howard in every way. But Howard is plagued by bouts of amnesia and tendencies toward suicide. Worse, he has fallen in love with Diedrich’s young wife Sally, and they have committed adultery. A blackmailer has discovered their affair and they are terrified that their love letters will be exposed. Into this Oedipal scenario steps Ellery, whom the couple beg to help them. Against his better judgment, he agrees.

Now the social landscape of Wrightsville matters less than the labyrinth of psychosexual tensions that Ellery confronts. He has to play double agent. For Diedrich, he is an innocent guest writing his new novel in lavish seclusion. For others, he becomes a go-between to save the couple. Inevitably, the blackmail plot deepens and Ellery is obliged to lie to the police and the townsfolk. The whole situation spirals into an orgy of betrayal and murder that leads Ellery to a false solution based on a monstrously blasphemous pattern of crimes. He eventually realizes that his ingenuity makes him profoundly predictable, and manipulable. Ellery confesses to the player on the other side:

Now the social landscape of Wrightsville matters less than the labyrinth of psychosexual tensions that Ellery confronts. He has to play double agent. For Diedrich, he is an innocent guest writing his new novel in lavish seclusion. For others, he becomes a go-between to save the couple. Inevitably, the blackmail plot deepens and Ellery is obliged to lie to the police and the townsfolk. The whole situation spirals into an orgy of betrayal and murder that leads Ellery to a false solution based on a monstrously blasphemous pattern of crimes. He eventually realizes that his ingenuity makes him profoundly predictable, and manipulable. Ellery confesses to the player on the other side:

“You’ve destroyed me. . . . You’ve destroyed my belief in myself. How can I ever again play little tin god? . . . It’s not in me . . . to gamble with the lives of human beings.”

Dannay planned this bleak book as the last in the Queen saga.

Appropriately, Lee’s prose texture matches the introspective bent of the plot. The subjective narration applied to Davy Fox is now given to Ellery, in a moment-by-moment italicized inner monologue that heightens his reaction to Howard’s and Sally’s situation. Howard says he was the seducer:

“I was the one who made the love, who kissed her eyes, stopped her mouth, carried her into the bedroom.”

Now we show the wound, now we pour salt on it.

Lee’s technique builds up the suspense when Ellery responds mentally to new plot twists.

“Last night there was another robbery.”

Last night there was another robbery.

“There was? But this morning no one said–“

“I didn’t mention it to anyone, Mr. Queen.”

Refocus, but slowly. . . .

“The cash is missing.”

Cash. . .

The inner monologue also passes bitter judgment.

“I could tell him and say I wanted him to divorce Sally and that I’d marry her, and if he hit me I could pick myself up from the floor and say it again.”

I believe you could, Howard. And even get a sort of pleasure from it.

Italicized inner monologues and streams of consciousness became common in popular fiction from the 1920s on, as Perplexing Plots explains. Lee came late to this technique, but he fitted it perfectly to a story that, more deeply than any other, traces the agonizing tensions that confront Ellery as someone meddling in human affairs he doesn’t fully grasp. Dannay said that he designed Ten Days’ Wonder as “an exposure of detective novels and of fictional detectives.”

Cat on the prowl

Between The Murderer is a Fox and Ten Days’ Wonder came a smaller-scale exercise in worldmaking, There Was an Old Woman (1943). Shoe magnate Cornelia Potts rules as eccentric matriarch over a family of ill-assorted children and others. Their estate consists of a gigantic bronze shoe on a pedestal, a tower in which daughter Louella concocts her mad experiments, and a cottage enclosing Horatio, a man who has decided to live in perpetual boyhood. The eldest son Thurlow occupies his time fruitlessly suing outsiders who appear to disrespect him. More normal are the three youngest children Bob, Mac, and Sheila, all despised by old Cornelia.

With its pattern based on the nursery rhyme, the novel offers another version of the devious master-mind trapping Ellery. But it remains somewhat awkward in its uneasy mix of zany comedy and serious murder. (Nevins plausibly suggests that Dannay was trying something akin to the screwball mysteries of Craig Rice.) A tacked-on ending shows Ellery gaining his secretary-girlfriend Nikki Porter, already a mainstay of the films and radio plays. But the effort to create an enclosed milieu of domestic fantasy, which Dannay sometimes called “Ellery in Wonderland,” fits Dannay’s urge, seen more earnestly in the Wrightsville tales, to expose the vulnerability of the supersleuth who must confront the occasional illogicality of the world.

With its pattern based on the nursery rhyme, the novel offers another version of the devious master-mind trapping Ellery. But it remains somewhat awkward in its uneasy mix of zany comedy and serious murder. (Nevins plausibly suggests that Dannay was trying something akin to the screwball mysteries of Craig Rice.) A tacked-on ending shows Ellery gaining his secretary-girlfriend Nikki Porter, already a mainstay of the films and radio plays. But the effort to create an enclosed milieu of domestic fantasy, which Dannay sometimes called “Ellery in Wonderland,” fits Dannay’s urge, seen more earnestly in the Wrightsville tales, to expose the vulnerability of the supersleuth who must confront the occasional illogicality of the world.

That urge finds its fullest expression in Cat of Many Tails (1949). Bearing the traces of police procedural films like Naked City (1948), this presents a serial killer stalking apparently random victims through Manhattan. Men and women, white and Black, are found strangled with cords of tussah silk. Although he withdrew from criminal affairs after his failure in Ten Days’ Wonder, Ellery is pressed to serve as the public face of the investigation. Facing several million suspects, he is baffled, forced to wander the streets, revisiting the crime scenes obsessively, imagining the victims meeting their fate.

Ellery eventually discloses the pattern behind the killings, but the novel’s development is dominated by a vision of a city under siege and citizens responding in panic. Lee responds with a narrative panorama far exceeding what we saw in his treatment of Wrightsville. He surveys Manhattan neighborhoods high and low. The victims are given detailed lives and routines and backstories; their friends and family are characterized as well. Here is a potential victim’s father:

Frank Pellman Soames was a skinny, squeezed-dry-looking man with the softest, burriest voice. He was a senior clerk at the main post office on Eighth Avenue at 33rd Street and he took his postal responsibilities as solemnly as if he had been called to office by the President himself. Otherwise he was inclined to make little jokes. He invariably brought something home with him after work–a candy bar, a bag of salted peanuts, a few sticks of bubble gum–to be divided among the three younger children with Rhadamanthine exactitude. Sometimes he brought Marilyn a single rosebud done up in green tissue paper. One night he showed up with a giant charlotte russe, enshrined in a cardboard box, for his wife.

The shifts in public response are charted through vivid, often frightening incidents. People stay home or avoid dark streets. Vigilante groups form. The press goes wild, keeping readers in tension with cartoons of a cat stalking the city and brandishing tails like nooses. All of this comes to smash in a virtuoso chapter describing a town meeting at which, when a woman screams, and the crowd becomes a stampeding mob.

The shifts in public response are charted through vivid, often frightening incidents. People stay home or avoid dark streets. Vigilante groups form. The press goes wild, keeping readers in tension with cartoons of a cat stalking the city and brandishing tails like nooses. All of this comes to smash in a virtuoso chapter describing a town meeting at which, when a woman screams, and the crowd becomes a stampeding mob.

“HE’S HERE!”

Like a stone, it smashed against the great mirror of the audience and the audience shivered and broke. Little cracks widened magically. Where masses had sat or stood, gaps appeared, grew rapidly, splintered in crazy directions. Men began climbing over seats, using their fists. People went down. The police vanished. Trickles of shrieks ran together. Metropol Hall became a great cataract obliterating human sound.

On the platform the Mayor, Frankburner, the Commissioner, were shouting into the public address microphones, jostling one another. Their voices mingled, a faint blend, lost in the uproar.

The aisles were logjammed, people punching, twisting, falling toward the exits. Overhead a balcony rail snapped; a man fell into the orchestra. People were carried down balcony staircases. Some slipped, disappeared. At the upstairs fire exits hordes struggled over a living, shrieking carpet.

Suddenly the whole contained mass found vents and shot out into the streets, into the frozen thousands, in a moment boiling them to frenzy. . . .

Dannay gave Lee the chance to compose scenes of cinematic excitement. No wonder the cousins thought that this novel might sell to the movies.

This extroverted narration is counterweighted by Ellery’s deepest plunge into self-analysis. Once more his proposed solution fails and leads to more deaths, and he is left feeling only a sense of waste. He consults an old psychoanalyst to confirm his conclusion and confess his inadequacy. “I’m too late again. . . . All right, I’m really through this time. I’ll turn my bitchery into less lethal channels. I’m finished, Herr Seligmann.” After consoling him that his efforts were not in vain, Seligmann says: “You have failed before, you will fail again. This is the nature and the role of man.” And he reminds Ellery of humility and mortality: “There is one God; and there is none other but he.” After this, as subsequent novels show, Ellery is able to go on–fallible but still holding to an ideal of truth.

For many critics, Cat of Many Tails is the cousins’ supreme accomplishment, a tour de force of mystery, suspense, and social and psychological observation. Their correspondence shows them at the absolute nadir of their relationship, exchanging long, hurtful letters about their disagreements. Yet their rancorous disputes yielded a novel that holds up better than much crime fiction of the 1940s. It’s a remarkable instance of how the “pure puzzle” story could, over the years, mutate into something rivaling the best of “prestige fiction”–an entertainment that is also an ambitious, moving literary achievement. Many mysteries are forgettable. This one is not.

Other Queen novels of Phase 3 are well worth reading. I’m a particular fan of The Scarlet Letters (1953), where Ellery intuits the solution watching a workman paint the G of “logical” in the sign for the New York Zoological Garden. Nevins considers Phase 4, which includes the more strained and fantastic puzzles of the late years, as of interest but not on a par with 3, and I’d agree. Still, the overall career of two Brooklyn cousins across four decades remains a major achievement of the American detective story, and a powerful lesson in how flexible and engaging popular storytelling can be.

Thanks to members of the UW Filmies for answering questions about their familiarity with Ellery Queen.

My figures on American bestsellers are derived from Alice Payne Hackett, Fifty Years of Best Sellers (Bowker, 1945) and subsequent editions of this book, as well as Frank Luther Mott, Golden Multitudes: The Story of Best Sellers in the United States (Bowker, 1947).

My photo of a masked Lee (or is it Dannay?) comes from the very curious article by Ellery Queen, “To the Queen’s Taste; or, Judge by Formula,” New York Herald Tribune (16 July 1933), F3. Here Queen proposes a 10-point chart for deciding on how good a mystery is. Barnaby Ross beats Agatha Christie.

To Nevins’ definitive Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection should be added the excellent resource Ellery Queen: A Website on Deduction. Another valiant defender of the Queen canon is Jon L. Breen, who wrote a spirited inquiry into why the books have been neglected by contemporary readers. See “The Ellery Queen Mystery” in the Weekly Standard, reprinted in Breen’s lively collection A Shot Rang Out: Selected Mystery Criticism.

Illuminating correspondence between Dannay and Lee is available in Blood Relations: The Selected Letters of Ellery Queen, 1947-1950 (Perfect Crime, 2012). The informative Wikipedia article lists all the Queen novels, noting the ghosted ones.

A note on names: Dannay and Lee admitted that in their youthful ignorance they didn’t know the slang term queen could refer to a gay man. Ellery, the name of a childhood friend of Dannay’s, evokes New England blue blood. Through the early books, Ellery comes off as a straight WASP. But during Phase 3, Dannay wrote to Lee: “After all, even though we would be subtle about it, the authors of the books are Jews, and in all the deepest senses, so is Ellery Queen the character” (Blood Relations, 93).

A recent example of a film using “Golden Age” principles of fair play is Knives Out, discussed here. I think Lee and Dannay would have approved.

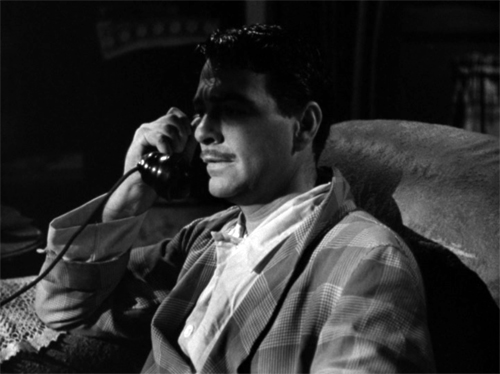

Ellery (Jim Huttton) breaks the fourth wall to extend his “Challenge to the Viewer” in the last episode of the NBC series Ellery Queen Mysteries, “The Adventure of the Disappearing Dagger” (29 February 1976), directed by Jack Arnold.

Noir x 3

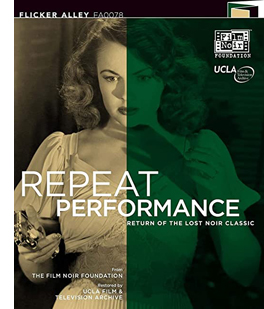

Repeat Performance (1947).

DB here:

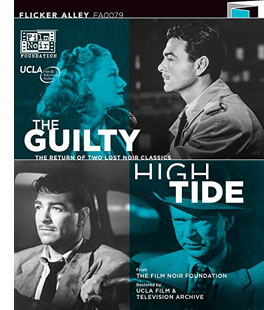

For several years, the Film Noir Foundation has initiated recovery and restoration of a great many neglected films, mostly from Hollywood. Thanks to Flicker Alley, several of those have made their way to DVD and Blu-Ray. (Earlier blog entries have considered the editions of Trapped and The Man Who Cheated Himself.) Now come two more discs, with beautifully restored copies and informative supplements.

The Monogram Touch

The Guilty (1947).

A generous double-feature disc displays what smooth B-filmmaking can look like. High Tide (1947) tells of Tim Slade, a rogue reporter brought back to work under his tough editor, Hugh Fresney. Fresney wants Tim’s help in taking on the city’s crime syndicate. Tim’s position is complicated by his past affair with the wife of the paper’s publisher, who’s hesitant to challenge the mob. A secret file on the gang becomes the target of Tim’s investigation, leading to an amiable former reporter Pop Garrow. The reversals pile up and lead to a surprise revelation at the climax.

A generous double-feature disc displays what smooth B-filmmaking can look like. High Tide (1947) tells of Tim Slade, a rogue reporter brought back to work under his tough editor, Hugh Fresney. Fresney wants Tim’s help in taking on the city’s crime syndicate. Tim’s position is complicated by his past affair with the wife of the paper’s publisher, who’s hesitant to challenge the mob. A secret file on the gang becomes the target of Tim’s investigation, leading to an amiable former reporter Pop Garrow. The reversals pile up and lead to a surprise revelation at the climax.

A noteworthy feature is a significant gap in a key scene. I can’t say more here, but the audio commentary by Alan K. Rode explains that although the complete scene is in the script, every print he has seen contains this omission. He speculates it might have been cut to shorten running time. I also wondered whether, since the print is a British one, the portion might have been snipped for censorship reasons. Interestingly, the AFI plot synopsis includes the scene. But 1947 sources give the original running time as 70 minutes, the same as the version we have, so the mystery remains.

Like other 1940s films, High Tide has a crisis structure. It starts with Tim and Fresney trapped in a car about to be swamped by the incoming tide. We then flash back to the events leading up to that. Director John Reinhardt and cinematographer Henry Sharp give us crisp, no-nonsense scenes making flexible use of depth staging (often to set Tim off as observer) and offering the occasional eye candy.

The main attraction on this double bill is The Guilty. It’s based on a Cornell Woolrich story, first titled “He Looked Like Murder” and republished as “Two Fellows in a Furnished Room.” As with most Woolrich adaptations, the film changes the original considerably. Mike Carr’s roommate Johnny Dixon is accused of murdering Linda Mitchell, twin sister to Estelle (Bonita Granville in a dual role). Dixon goes on the run while Carr investigates and maintains his rough-edged affair with Estelle.

Woolrich’s story doesn’t give us twin sisters or a romantic plot; the emphasis falls on Carr’s disintegrating relation with his roommate. The clues are much the same, but the film adds a flashback structure, with Carr narrating past events to a bartender (and us) as he waits for Estelle. The short story’s solution is predictable, while the film offers a twist ending, heightened by a nifty slippage of that voice-over.

The film’s plot sacrifices coherence for its surprise finale, but the overall result is pretty impressive for a two-week shooting schedule. Out of a few cheap sets, Reinhardt and Sharp create a varied range of angles and modulated lighting.

The film is exceptionally free of gunplay and other violence, but that lack is made up by a remarkable scene in a morgue. The police detective is describing to Carr how Linda was killed. As he stands by the mortuary drawer, his dry account of the grisly murder is chilling. (Once more, sometimes telling beats showing.) It’s close to the same scene in the original story. As Eddie Muller indicates in his introduction, it’s the most shocking scene in the film.

The Guilty also spares time for images that foreshadow the outcome, as in ominous high angles of a street. There’s also the sort of evocative superimpositions that Hollywood occasionally supplies. A purely functional shot of the morgue drawer sliding shut dissolves to a shot of Estelle in bed, at once substituting for her sister and looking ahead to her as a possible victim.

The Guilty typifies the sort of film that deserves to be recognized as a part of a fine Hollywood tradition—the well-made B. I had never seen it or High Tide before, and they reminded me of what could be done at the studio that also gave us the Bowery Boys, Dillinger (1945), and King of the Zombies (1941).

The future’s gonna change

Calling Repeat Performance (1947) a film noir illustrates how elastic the label has become. Yes, it begins with a murder in the manner of Mildred Pierce (1945). There’s a flashy use of chiaroscuro at its climax (surmounting this entry). It’s directed by the elusive Alfred Werker, who signed the woman-in-peril thriller Shock! (1946) and was involved with He Walked by Night (1948). But as Daily Variety’s review pointed out, it’s less a crime story than a “suspense melodrama.” And it traffics in supernatural explanations.

Eddie Muller’s introduction points out that a noir like Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948) also invokes otherworldly forces. But like the Guilty adaptation, the source has been heavily altered. William O’Farrell’s novel Repeat Performance is told from the viewpoint of a man being hunted for strangling his wife. It’s a thriller more closely tied to the conventions of what we think of as noir. By switching the action to the viewpoint of the wife, and eliminating the police pursuit, the film gives us something closer to another cycle of the 1940s.

Eddie Muller’s introduction points out that a noir like Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948) also invokes otherworldly forces. But like the Guilty adaptation, the source has been heavily altered. William O’Farrell’s novel Repeat Performance is told from the viewpoint of a man being hunted for strangling his wife. It’s a thriller more closely tied to the conventions of what we think of as noir. By switching the action to the viewpoint of the wife, and eliminating the police pursuit, the film gives us something closer to another cycle of the 1940s.

During that decade, filmmakers continued a Hollywood vein of fantasy—most obvious in the ghost films that proliferated, but also in tales of divine intervention by angels and other forces. Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941) and It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) visualize alternative futures for their protagonists. Portrait of Jennie (1949) suggests a time stream operating alongside that of normal life, and some films with prophetic dreams suggest that the characters’ fates are determined.

Other media dabbled in the alternative-universes premise. Most famously, J. B. Priestley experimented with forking-path plots in the play Dangerous Corner (1932). (I talk about the film version here.) His later dramas, such as Time and the Conways (1937) and I Have Been Here Before (1937), pursue parallel timelines, but the closest to Repeat Performance, I think, is his remarkable “mystery” An Inspector Calls (1945).

It’s no spoiler to say that the plot of Repeat Performance restarts the time scheme of the action. On New Year’s Eve, as 1947 starts, the actress Sheila Page shoots her husband Barney. But as she leaves the murder scene, she enters the world a year earlier, on the first day of 1946. As the voice-over narration explains, she will relive that year.

After Sheila understands that she has a reprieve, she sets out to change the events that led up to her crime. She tries to keep Barney sober and focused on writing his next play, and above all she struggles to keep her rival Paula Costello away from him. She wants, she says, to “rewrite the third act.” Yet even when she changes the circumstances, accidents intervene to block her efforts. She fears that the onset of 1947 will drive her to kill again. Can she thwart destiny?

The result yields a satiric portrait of Broadway backstabbing, while cleverly suggesting that the changes in Sheila’s future are like revisions of a play in production. During a rehearsal, she suggests improving Act II by “playing it backwards”—that is, putting the scenes in reverse order. Yet they yield the same consequences, just as she will learn that her fate doesn’t care about the particular patterning as long as “the result is the same.”

Like Back to the Future (1985), the film is a time-travel adventure that aims to reset the past. It reminds us that a lot of modern movie storytelling consists of shrewd revisions and updatings of premises that had their sources in earlier Hollywood periods—particularly the 1940s. Fans of The Twilight Zone will have fun with Repeat Performance.

The Film Noir Foundation’s releases abound in no-nonsense supplements. They’re full of historical background to the films, the companies, and the personnel. On these two discs we get a detailed study of producer Jack Wrather, a rich account of the Eagle-Lion company, career summaries of Cornell Woolrich, John Reinhardt, Lee Tracy, and Joan Leslie, a pressbook for Repeat Performance, and informative liner notes. These put us in the debt to filmmaker Steven C. Smith and film historians Alan K. Rode, Eddie Muller, Imogen Sara Smith, Farran Smith Nehme, Brian Light, and many interviewees. Not only the films but the bonus materials are excellent additions to a cinephile’s collection.

The Daily Variety review of Repeat Performance is in the issue of 23 May 1947, p. 3. For my take on Cornell Woolrich and cinema, go here. I discuss Repeat Performance along with other fantasy-laden films of the period in Reinventing Hollywood: How Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, chapter 9.

Repeat Performance (1947).

PERPLEXING PLOTS: On the horizon

DB here:

In the Before Times, I didn’t watch much fictional TV. Our modest monitor was chiefly a delivery device for news, DVDs, and Turner Classic Movies. We followed The Simpsons, and I came to like Deadwood and Justified, but usually the time commitment demanded by long-form series put me off. I gave my curmudgeonly reasons long ago on a blog entry.

But over the last nine months, forced to stay home, I dipped my toe in the water. Streaming made it easy to catch up with shows I’d never seen and offered a plethora, or rather a glut, of original series. This still-limited experience of long-form shows confirms the presence, if not the dominance, of what Jason Mittell in his excellent book calls Complex TV.

Many shows mix timelines with abandon. Both the documentary WeWork; or, The Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn (2021) and the docudrama WeCrashed (2022) open near the end of the story action and then flash back to show what led up to it. (This crisis structure became especially common in 1940s Hollywood.) Billions, an older series I’d never followed, contains an episode (Season 2, 2016) that jumps to and fro among a funeral, scenes taking place before it, and scenes afterward, several attached to different characters. In the Hulu series Dopesick (2021) a sliding timeline graphic shifts among many periods and character viewpoints; to keep track of it all you’d need to make a spreadsheet. (It would amount to something like the whiteboard used in writers’ conference rooms to map out the unfolding series.) I can’t recall all the shows that friends have recommended as examples of daring play with narrative.

Of course all this isn’t news. For years both indie films and Hollywood blockbusters have offered complicated segmentations, broken timelines, and splintered viewpoints, with contradictory replays and unreliable narration. Still, it was good to be reminded that the problem I’m tackling in my latest book is still current—indeed, dominant. We may have to wait for the new Justified series to see a return to straightforward linear storytelling.

When and how did viewers develop the skills that lets them appreciate the New Narrative Complexity? This is at the center of Perplexing Plots: Popular Narrative and the Poetics of Murder.

Maybe we were always smart

Intolerance (1916).

There’s a view, most eloquently posed by Steven Johnson in Everything Bad Is Good for You, that these comprehension skills are a fairly recent development. They stem from rising IQ levels, growing facility with video games, and other cultural phenomena after the 1970s. People are now smarter consumers of narrative than they were in the days of I Love Lucy.

I argue instead that popular narrative has been cultivating these skills across a much longer period, and they firmly took hold in mass culture at the start of the twentieth century. You can get a summary of my argument here on the Columbia University Press site.

Most broadly, a lot of (now-forgotten) mainstream plays and novels were as experimental in shifting point-of-view and juggling time frames as any we find today. For example, we celebrate backwards stories as typical of the demands of modern storytelling. The play and film Betrayal and the films Memento and Shimmer Lake are among many recent media products presenting the scenes in 3-2-1 order. But this possibility was discussed by a prominent critic in 1914, and soon a major woman actor wrote a play that used reverse chronology. There followed other examples, not least W. R. Burnett’s novel Goodbye to the Past (1934) and the Kaufman and Hart play Merrily We Roll Along (1934).

Some will argue that innovations of popular narrative are dumbed-down borrowings from modernist or avant-garde trends. I try to show this process as a two-way dynamic: modernism borrowing from popular forms, mainstream storytellers making modernist techniques more accessible. But we also find that popular storytelling has its own intrinsic sources of innovation, as with the reverse-chronology tale and Griffith’s application of crosscutting to different time frames in Intolerance (1916).

So it seems to me that audiences have long been capable of tracking the sort of fancy narrative devices we find now. They encountered them in many types of stories, and I devote the first part of Perplexing Plots to a quick survey of developments in novels and plays. (Yes, Stephen Sondheim is involved.) Audiences have learned to enjoy self-conscious artistry, an awareness of form and technique–what one disapproving reviewer of Wilkie Collins called “the taste of the construction.”

Such a taste was cultivated in depth in one mega-genre. That was a major training ground for giving us the skills to follow complex, sometimes deceptive storytelling.

Mystery on my mind

Pulp Fiction (1994).

Ever since my teenage years I’ve been a fan of mysteries on the page and on the screen. I’ve smuggled discussions of detective stories and crime thrillers into many of my books, and my last one, on 1940s Hollywood, did a lot with this form of storytelling–largely because it was so central to the films of that era.

Perplexing Plots in a way turns Reinventing Hollywood inside out. The earlier book put movies at the center while showing how filmmakers borrowed from mysteries in other media. The new one puts fiction, theatre, radio, and even comic books at the center, discussing how mystery conventions developed–and showed up in films as well. The two books complement each other, I guess, although the historical sweep of the new one runs from the 1910s to the present.

Mystery was essential to many classic novels, from Wuthering Heights to the tales of Henry James and Joseph Conrad. Dickens and Wilkie Collins made mystery a major attraction of “sensation fiction.” In the twentieth century, the Anglo-American whodunit, the suspense thriller, and the hardboiled detective tale–to take the three most well-known genres–trained audiences in appreciation of nonlinear plotting, misleading narration, and subterfuges of concealment.

A Western or a science-fiction tale may include a mystery, but it doesn’t have to. In mystery fiction, the suppression and misinterpretation of information is foundational to the genre itself. A mystery depends on a “hidden story,” which will often be revealed out of chronological order and refracted through the minds of several characters. At a meta-level, the genre cultivates a gamelike approach, where we expect the author to give with one hand and take away with the other. Across history, a mass audience became sophisticated consumers of complex narratives.

I trace how this happened with Agatha Christie, John Dickson Carr, Marie Belloc Lowndes, E. C. Bentley, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Daphne du Maurier, Cornell Woolrich, and many other authors. I spend a lot of time analyzing both plot structure and the texture of the writing. If nothing else, I hope to show that this genre encourages not only great ingenuity in plotting but also subterfuges of style.

I trace this process into the 1940s, when in my view the basics of contemporary techniques crystallized and become widespread. The book then looks at some case studies of how crime novels and films have explored the various possibilities of broken timelines, disparate viewpoints, and misleading narration. I devote chapters to Erle Stanley Gardner, Rex Stout, Patricia Highsmith, Ed McBain, Donald Westlake, Quentin Tarantino, and Gillian Flynn.

I could have gone much farther. Every reader will have a long list of authors I’ve omitted. But I had to stop somewhere! And I decided to concentrate on some of my favorites. The result is, if nothing else, appreciations of the verbal artistry of some underestimated storytellers.

This isn’t to say that audiences of 1920 could have easily followed Inception (2010) or Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022). Storytellers have pushed forward, revising schemas that are widely known and teaching us to recognize the tweaks they’ve introduced. Audiences have accumulated a repertory of skills, built upon their experiences of other formal experiments. Those experiences, I want to show, have been crucially shaped by the conventions of mystery narratives.