Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories

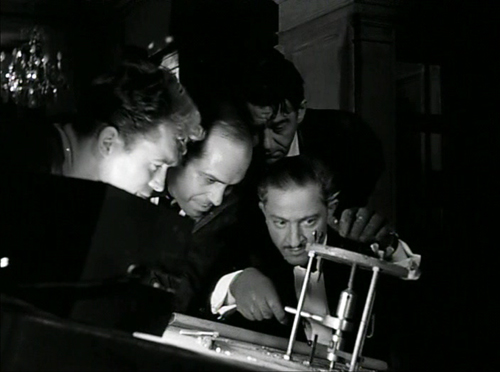

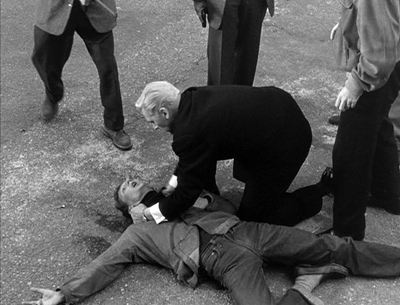

The Underneath (1995).

DB here:

The announcement of Ocean’s Eight (premiering, when else?, on 8 June next year) reminded me of the staying power of the heist genre, also known as the big-caper film. I discuss it a bit in Reinventing Hollywood, my book on 1940s storytelling, but it developed and spread out most vigorously from the 1950s on.

In its origins it relies on masculine roles; if women are present they’re likely to be at best helpers, at worst traitors. The big job is likely to be endangered by a man telling his wife or mistress too much, and then the police or rival gangs may interfere. So the news that Ocean’s Eight will center on a female gang constitutes an intriguing wrinkle. (Will a boyfriend try to spoil the caper?) Warners’ ambitions for another trilogy seem evident: presumably the entry is Eight because Warners hopes for a Nine and a Ten. Commenters are already worried that a “feminized” version runs the risk of flopping the way Ghostbusters did last year, but I’m more hopeful. The reason is that clever storytelling is encouraged in this genre. There’s a chance that the film, produced though not directed by Steven Soderbergh, will show us that this old dog has new tricks.

Because I’m interested in the storytelling strategies of popular cinema, the heist film is a natural thing for me to consider. Refreshing the genre may involve not just adjusting the story world—giving men’s roles to women—but also considering ways of handling two other dimensions of narrative: plot structure and cinematic narration. I argue in Reinventing that Hollywood filmmaking uses a sort of variorum principle, a pressure to explore as many narrative devices as possible within the constraints of tradition. For this reason, the prospect of Ocean’s Eight prodded me to think about how convention and innovation work in the caper movie. It’s also a good excuse to go back and watch some skilful cinema.

From the fringes to the core

The Asphalt Jungle (1950).

It’s useful to think of a genre as a category having a core and a periphery. At the core are prime, “pure” instances: prototypes. Stretching out from it are less central, fuzzier cases. Prototypical musicals are Footlight Parade, Shall We Dance?, Meet Me in St. Louis, and My Fair Lady. Somewhat less central are concert films and musical biopics like Lady Sings the Blues and Coal Miner’s Daughter. At the periphery are movies with a single song or dance number. Of course the category changes across history; a critic in 1960 might have picked North by Northwest as a prototypical spy thriller, but ten years later a Bond film would have probably held that place.

The prototypical heist film, critics seem to agree, doesn’t just include a robbery. There are robberies in films about Robin Hood and gentleman thieves like Raffles and the Saint. The outlaw or bandit film like They Live by Night and Bonnie and Clyde contains a string of robberies, but they wouldn’t be at the center of the heist category.

Donald Westlake proposed a concise characterization: “We follow the crooks before, during, and after a crime, usually a robbery.” This indicates two things. First, the plot is structured around the big caper, though there might be lesser crimes enabling it, such as stealing weapons. Second, the viewpoint is organized around the criminals, not the detectives who might pursue them, as in a police procedural. By these criteria, High Sierra (1941), although allied to the bandit tradition, fits because most of the film concerns a single robbery, its preparations and aftermath.

Westlake shrewdly goes on to note that the interest of a heist plot inverts that of the traditional locked-room detective story. Instead of wondering how something difficult was done, we wonder how something difficult will be done. “The puzzle exists before the crime is committed.” To fill in the how, crooks with specific skills (safecracking, demolition, getaway driving, and so on) are recruited. Because the process matters so much, Westlake adds that heist plots focus on details of time and physical circumstance, and they draw attention to impediments such as “dogs, locks, alarms, watchmen, and complicated traps.” Most of these features are missing from High Sierra; we’re not encouraged to speculate how the job will be pulled, there’s little meticulous planning and no division of labor by expertise, and the only dog is friendly. So it’s unlikely to be a core instance of the genre as we now consider it.

Most critics consider The Asphalt Jungle (novel, 1949; film, 1950) a solid prototype. In fiction and film it’s not the very earliest instance, but it displays what we might call the “completed arc” of a heist plot. A gang of varying talents is assembled and funded to pull off a jewel robbery, which succeeds partly at first and eventually fails.

A less famous example comes from 1934, Don Tracy’s novel Criss-Cross. Here an alienated loner finds that his long-ago girlfriend has married a local crook. To get her back, the hero agrees to be the inside man in a robbery of the armored truck he drives. The heist goes badly, with the hero shooting the gangster and getting shot himself. He’s acclaimed as a hero, but fate catches up with him when a blackmailer who knows the truth starts putting the squeeze on him. Where The Asphalt Jungle ranges across many characters’ knowledge in a fairly tight time span, Criss Cross restricts its point of view to the protagonist but traces his life over a long period. These storytelling options, ingredient to any narrative whatsoever, will shape how the heist plot is handled.

A less famous example comes from 1934, Don Tracy’s novel Criss-Cross. Here an alienated loner finds that his long-ago girlfriend has married a local crook. To get her back, the hero agrees to be the inside man in a robbery of the armored truck he drives. The heist goes badly, with the hero shooting the gangster and getting shot himself. He’s acclaimed as a hero, but fate catches up with him when a blackmailer who knows the truth starts putting the squeeze on him. Where The Asphalt Jungle ranges across many characters’ knowledge in a fairly tight time span, Criss Cross restricts its point of view to the protagonist but traces his life over a long period. These storytelling options, ingredient to any narrative whatsoever, will shape how the heist plot is handled.

Criss-Cross and The Asphalt Jungle show that we’re dealing with an exceptionally schematic plot pattern. For convenience we can distinguish five parts.

Circumstances lead one or more characters to decide to execute a heist (robbery, hijacking, kidnapping).

The initiators recruit participants.

As a group they are briefed and prepare their plan. They study their target, rehearse their scheme, or take steps to make it easier.

The heist itself begins and concludes.

The aftermath of the heist, failed or successful, shows the fates of the participants.

There are other conventions, nicely laid out by Stuart Kaminsky in 1974 and more recently by Daryl Lee. But I’ll just concentrate on this structure and how it governs narration, because these aspects show very clearly the constant dynamic of schema and revision in the filmmaking tradition.

Four capers, mostly unhappy

Criss Cross (1948).

Four films in the period covered in my book point toward the heist genre, though only one became a core instance. The presence of a “consolidating” film might be one way genres emerge.

The earliest candidate is an unlikely one. In 1941 Laura and S. J. Perelman mounted a notably unsuccessful play called The Night Before Christmas, a farce in which crooks buy a luggage store in order to tunnel from its basement into the bank vault next door. Although Paramount was a backer of the stage show, Warners bought the rights and revamped it for Edward G. Robinson, who had had success in gangster comedies like A Slight Case of Murder (1938). The adaptation, Larceny, Inc. (1942) maintained the premise but revised the plot, multiplying the complications that face the leader Pressure and his two minions. The twist is that thanks to Pressure’s daughter, who’s unaware of the scheme, business starts booming and the crooks find themselves prosperous businessmen. Woody Allen swiped the premise for his Small-Time Crooks (2000).

Just as we don’t expect a comedy to be the initial entry in a genre mostly associated with drama, we might expect that the early entries in the genre would be the tidiest, with complex variations building on them. Actually, two precursors of The Asphalt Jungle display remarkable complexity.

The simpler one, Criss Cross (1948), starts late in the preparation phase: the night before the caper, when the gang is holding a party to distract a local cop who has his eye on them. We learn that Steve is working with Slim’s wife Anna to double-cross the gang. The next day, Steve is driving the armored car and recalling how he got into this situation. A flashback provides the circumstances for the robbery—Steve’s pursuit of Anna, her marrying Slim, and Steve’s impulsive proposal of a robbery to protect Anna from Slim’s punishment.

Next comes the planning phase. The robbers assemble and the task is reviewed by a mastermind they hire. This second flashback ends and, back in the present, we see the heist itself. The aftermath of the bloody robbery shows Steve in the hospital, honored by the community. A thug kidnaps him and takes him to Anna. Slim has survived the gun battle and finds the couple; he kills them before he is mowed down by the police.

Early as Criss Cross is in the history of the film genre, the plot components are already being scrambled. Thanks to 1940s Hollywood’s commitment to flashbacks and character subjectivity, the novel’s linear action gets fractured, compressed, and stretched. Moreover, in most films, the decision to pull the heist is made fairly early. Here and in the novel, circumstances slowly force Steve to rescue Anna from the man who mistreats her. The buildup to this decision consumes nearly fifty minutes of an 87-minute movie. Similarly, the aftermath of the heist is quite protracted, running about twenty minutes. And whereas other films (and novels) dwell on the recruitment of thieving talent, here this is elided. That’s because the other members of the gang are less significant than the central triangle of Steve, Anna, and Slim.

The Killers (1946) is even more complex because it clamps the block construction of Citizen Kane onto the heist schema. We start with one bit of the heist aftermath: the death of the gas-station attendant Ole. Like Kane, who also dies in his bed at the start of his film, Ole is the protagonist of the past-tense story. We next meet the protagonist of the present-time story, the insurance investigator Riordan, who functions like the reporter Thompson in Kane, and sometimes even gets the same silhouette treatment.

The rest of the film splits up the basic parts of the heist schema, rearranges their order, and presents them through a series of several flashback blocks, anchored in six characters’ testimony.

The heist itself is very brief, running only about two minutes, and the planning phase is only a little longer. As in Criss Cross, the leadup and the aftermath constitute the bulk of the film, but these phases are broken up into many bits, and these are often shuffled out of chronological order. We see Ole’s discovery by Big Jim years after the heist and then we see Ole, days after the heist, distressed that his lover Kitty has betrayed him. Similarly, a crucial event after the heist—Ole’s stealing the loot from the gang—precedes a scene before the heist in which he learns the gang is planning to double-cross him. We have to reconstruct the canonical sequence, from circumstance to aftermath, out of fragments revealed in testimony taken by Riordan.

Critics haven’t taken Criss Cross and The Killers as the first core instances of the heist film, perhaps because these movies complicate the classic plot template. In addition, they downplay the planning and execution phases. The heist scenes are relatively minor compared to the time devoted to other phases, particularly the circumstantial buildup. Moreover, the robber teams aren’t vividly characterized and don’t display a range of expertise. The emphasis falls on Steve and Ole, both played by Burt Lancaster, as the beautiful losers who become suckers for treacherous women and their brutal men.

By contrast, the linearity of The Asphalt Jungle throws the plot template into crisp relief. Both novel and film offer a full-blown enactment of central features picked out by Stuart Kaminsky. The gang, despite low social standing, has many skills. They’re held together by a leader who may also be a brainy planner. The robbers’ plan requires “skill, practice, training, and above all, perfect timing.” The gang’s resourcefulness is tested by accidents. The caper is partly successful but largely a failure, often through sexual weakness on the part of some players.

W.R. Burnett’s book opens up the wide narrative possibilities of the genre, thanks to an expanded group of characters. Where Don Tracy’s novel Criss Cross confined itself to relatively few figures, Burnett innovates by developing no fewer than eighteen distinct individuals, all somehow connected to the jewel robbery. New roles are assigned that will be staples of the genre—financier, go-between, bent cop, owner of a safe house. We see policemen of all ranks, a news reporter, the master mind Dr. Riedenschneider, the fixer Cobby, the bankroller Emmerich (who has a wife, a mistress, and a hired detective), and the four men on the team, two of whom have women attached.

W.R. Burnett’s book opens up the wide narrative possibilities of the genre, thanks to an expanded group of characters. Where Don Tracy’s novel Criss Cross confined itself to relatively few figures, Burnett innovates by developing no fewer than eighteen distinct individuals, all somehow connected to the jewel robbery. New roles are assigned that will be staples of the genre—financier, go-between, bent cop, owner of a safe house. We see policemen of all ranks, a news reporter, the master mind Dr. Riedenschneider, the fixer Cobby, the bankroller Emmerich (who has a wife, a mistress, and a hired detective), and the four men on the team, two of whom have women attached.

The novel lays out the canonical action phases with surgical efficiency. But as in the films I’ve just mentioned, the planning and the heist itself take relatively little space. Given so many characters’ contribution to the action, their gradual convergence and their dispersed fates dominate the book. Over a hundred pages are devoted to setting up the circumstances and recruiting the gang. The aftermath, tracing the outcome for all involved, runs another 140 pages.

The film adaptation retains the novel’s scope, trimming only a couple of minor characters. It moves briskly among the ensemble, attaching us to several in turn, so we know more than any one character does. The narration creates parallels among the team members and their affiliates (such as four women of different classes, with varying commitments to their men).

The result is something of a network narrative, a cross-section of several people whose lives change because of the robbery. There’s no clear-cut protagonist like Steve in Criss Cross. Dr. Riedenschneider has the most screen time, but the film begins and ends with the hooligan Dix, and the fate of both men dominates the climax. I point out in Reinventing Hollywood that a multiple-protagonist film often gives extra weight to one or two characters.

50s and 60s stylings

Violent Saturday (1955).

With The Asphalt Jungle as a robust prototype, writers and filmmakers developed the heist plot throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Despite his clumsy style (”He nodded with his head”), Lionel White became known as “the king of the caper novel” for his tireless variants on robberies, hijackings, and kidnappings. The other major figure was the far superior Donald Westlake, who wrote brutal heist tales as “Richard Stark” and comic ones under his own name.

In the comic register, Westlake was beaten to the post by heist films from England. The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) showed a timid clerk engineering the theft of gold bullion, which he disguises as kitschy miniature Eiffel Towers. The Lady Killers (1955) centered on a gang fooling their landlady into thinking that their planning meetings are actually string-quartet sessions. In Italy, the classic Big Deal on Madonna Street (I soliti ignoti, 1958) showed five incompetents trying to break into a pawnshop safe.

Big Deal was considered a parody of a much more serious film, one that was by then a landmark: Rififi (Du rififi chez les hommes, 1955). It did a great deal to consolidate the genre in France, along with Touchez pas au grisbi (1954) and Bob le flambeur (1956). (Both The Killers and Criss Cross had been imported in the Forties.) In England, the heist drama was seen in The Good Die Young (1954), while in the US there were 5 Against the House (1955), Violent Saturday (1955), Plunder Road (1957), The Big Caper (1957, from a White novel), and Odds Against Tomorrow (1959). The year 1960 saw a remarkable number of releases, with The League of Gentlemen (U.K.), The Day They Robbed the Bank of England, Seven Thieves, and most famously Ocean’s 11 (all U.S.).

Through the 1960s the genre proliferated, including a remake of The Asphalt Jungle (Cairo, 1963), Jules Dassin’s near-self-parody of Rififi (Topkapi, 1964), and a string of heist films that mixed in romantic comedy (e.g., Gambit, 1966; How to Steal a Million, 1966). The Italian Job (1964) became a cult movie, with tourists visiting the sites of shooting in Turin. The genre has remained robust throughout world cinema ever since.

The very rigidity of its format and the constraints it lays down, have allowed for ingenious innovations. I’ll sample some of those from the genre’s first dozen or so years, concentrating on three areas: the differing emphasis given to the plot phases; variants of point-of-view; and manipulations of time.

Where’s the action?

Rififi (1955).

The Asphalt Jungle offers a fairly pure geometry: the heist, lasting about eleven minutes, ends just before the film’s midpoint. On the other side of that is another big scene: a gunfight initiated by Emmerich’s henchman Brannom when Dr. Riedenschneider and Dix bring in the loot. That confrontation takes another seven minutes, so the heist and its immediate wrapup sit at the center of the running time. What led up to the heist, the circumstances, recruitment, and planning phases, consume the first forty-five minutes of the film, and the aftermath of the heist, affecting the surviving characters, will take just about as long. This balanced geometry, putting the heist snugly at the center of the plot but devoting most time to showing many lives leading up to and away from the crime, suits the extensive characterization of all involved.

This is a neat structure, but not the only possibility. Any phase of the action can be given great weight. The first half hour of Bob le flambeur is an episodic introduction to Bob’s routines and associates. It’s the circumstantial phase—he’s running out of money—presented at low pressure, emphasizing instead the fascinating milieu Bob coolly drifts through. Only when Roger points out a croupier at the Nantes casino does Bob formulate “the job of a lifetime.” Then crew assembly and planning can begin. As the plot develops, characters and relationships presented casually in the exposition become crucial to the heist and its unraveling.

Other phases can be stretched out. Ocean’s 11 dwells on the phase of gathering the talent. Before the start, Danny Ocean has already conceived the heist, but we aren’t told the plan. Instead we watch his team members converge on Las Vegas. Not until the film’s midpoint, at 53:00, is the plan revealed in a briefing. The dawdling exposition suits a film about cool guys hanging out.

The formation of the crew is exceptionally protracted in Odds Against Tomorrow, because here two members hesitate about participating. The racist Earl Slater, wracked by the shame of not providing for his wife, finally gets her to agree to let him join. Not until twenty-three minutes from the end does the African-American musician Johnny Ingram finally accept a role in the heist, which immediately becomes the film’s climax.

The source for Odds Against Tomorrow (one of the better heist novels) handles the basic pattern very differently, putting the heist just before the midpoint and devoting the second half of the book to the increasingly hopeless getaway, where the interracial tensions play out at length.

The planning phase sometimes includes a rehearsal for the heist, and that may require a subsidiary crime, such as stealing keys or a vehicle. The League of Gentlemen has an unusually long planning phase, in which the gang masquerades as soldiers in order to seize weapons from a military post. This robbery, running nearly twenty minutes, takes longer than the film’s main heist but serves to demonstrate the team’s resourcefulness and esprit de corps. The men’s precision and resourcefulness (based on their wartime experience) lead us to expect a successful main event.

Kaminsky suggests that the big-caper genre resembles the soldiers-on-a-mission movie, which centers on the details of a process executed by skillful specialists. That display of process comes to the fore in The Asphalt Jungle’s central robbery, which initiated the convention of detailing the mechanics of the heist. Other films expanded the heist sequence to larger proportions than was evident in The Killers or Criss Cross. Rififi became the model; its heist runs twenty-five minutes without any words being spoken. (That sequence is part of an even longer wordless stretch that runs over thirty minutes.) Dassin’s film meticulously breaks down the steps of a complicated robbery, allowing us to appreciate the men’s clever planning while, as usual, ratcheting up moments of suspense when it appears they might fail.

After Rififi, heist scenes got longer and more intricate. The one in Big Deal on Madonna Street runs twenty minutes, those in Seven Thieves and The Day They Robbed the Bank of England run thirty minutes, and those in Topkapi and The Italian Job approach forty minutes. To motivate these long, virtuosic passages, there need to be many obstacles, many ingenious ways around them, and many characters concentrating on their assigned duties.

Long or short, the heist can be shifted off-center. The heist can be the climax, as in The Big Caper, or it can be virtually the film’s entire second half, as in The Italian Job (which arguably doesn’t complete the heist and so never provides a proper aftermath). Topkapi’s flamboyant robbery, involving elaborate subterfuges, dominates the film’s latter stretches, leading to a quick reversal in its epilogue. The heist is finished early on in The Lady Killers, since the crucial action is the long aftermath in which, contradicting the title, the crooks dispose of one another. By contrast, the heist dominates nearly all of Larceny, Inc. Most of the film is devoted to the crooks’ slowly deepening tunnel, as the process is interrupted by breaks in the water main, a geyser of furnace oil, and their decision to abandon their plan in favor of going straight—before another crook comes along to continue the caper.

Or the heist can launch the film. In Plunder Road, after the train robbery is completed, the rest of the film is the aftermath, consisting of chases and suspense sequences. The circumstances, recruitment, and planning phases are alluded to in dialogue, as suits a low-budget production. The plot of Touchez pas au grisbi starts the morning after the caper and shows thieves trying to protect their loot from a treacherous drug dealer. It was probably inevitable that somebody would make a heist movie that keeps the heist offscreen and makes the action one long aftermath.

Steering the moving spotlight

Topkapi (1964).

Many films based on mystery rely on restricting a character’s range of knowledge, as in detective novels told in the first person. But suspense, Hitchcock and others recognized, relies on greater access to story information. If there’s a bomb under the table, Hitch advised, tell the viewer but don’t tell the characters. The heist film, as an account of how a crime is committed, depends more on suspense than mystery. So we’d expect a constant shuttling from character to character, filling us in on how the scheme is going and letting us worry about impending dangers.

This is generally what we find. Criss Cross is unusual in confining us to what Steve knows about Anna’s and Slim’s real agendas, and this confinement is what yields the surprises that pop up in the film’s final stretches. Mostly, though, heist movies and novels use omniscient narration. Employing what I call in Reinventing Hollywood the “moving spotlight” approach, the film shifts us from attachment to one character to another.

The moving spotlight permits us to understand the choreography of the crime, in which many characters play a part, and to feel suspense when matters of timing or accident intrude. Indeed, the convention of the unforeseen accident that spoils the heist relies on our breaking attachment to the crooks and getting privileged access to the off-schedule night watchman, the passing witness, or the failed piece of machinery. In Topkapi we and not the thieves learn how a stray bird will upset their getaway.

This omniscient narration (which need not tell us absolutely everything) can be deployed in a range of ways. One option is chapter titles, as in Big Deal on Madonna Street (and revived by Tarantino in Reservoir Dogs). A more common resource is the non-character narrator, present as an authoritative voice-over. In Bob le flambeur, a worldly male voice introduces us to Bob’s daily routine and comments somewhat cynically on his place in his milieu.

A similar all-knowing voice introduces us one by one to the heisters in The Good Die Young; there it eases the transition into expository flashbacks. Topkapi treats this convention, as others, with self-conscious playfulness. At the beginning the beguiling woman in the gang addresses the camera and explains that the heist aims to get the emerald she covets. She doesn’t take this narrating role again until the very end, in a brief epilogue that replays the gathering of the gang in stylized form.

Heist films must often choose whether to widen the field of view to include either the cops or civilians. Armored Car Robbery (1950), for me a peripheral instance of a heist film, alternates the gang’s activities—which do pass through the phases I’ve outlined—with the detectives’ investigation. The result is balanced between heist film and police procedural. Something similar happens in Violent Saturday (1955), which devotes most of its plot to a gang’s scheme to rob a mining town’s bank. Crosscut with the gang’s gathering and planning are scenes showing several members of the community, each with domestic problems. These scenes, typical of small-town melodrama (dissolute rich people, sexy nurse, repressed librarian, lovelorn bank manager), not only pad out the film but show us characters who will be affected by the heist. Some become witnesses and bystanders during the robbery, one is killed, and one, a local mining manager, will be forced to fight the gang at the climax.

The timing and selection of the shifts among characters can build up specific effects. For instance, in Big Deal on Madonna Street, the heist is conceived by Cosimo, a hardheaded crook doing time. A handful of would-be crooks decides to execute the robbery without him. We know, as the gang does not, that he has been released and is conspiring to interfere. The filmmakers could have made Cosimo’s return a surprise revelation, but instead our expectation that he’ll start meddling intensifies our interest.

Similarly, we know, as the Topkapi gang does not, that Arthur is a police spy. But then he confesses to them, so we know, as the Turkish police do not, that he is to be a double agent. The film milks suspense during the scenes in which Arthur relays information to the authorities, and then it makes us wonder how the gang will use their new knowledge of police surveillance. This is the sort of fine-tuned choice about “who knows what when” that heist films must make at every turn.

At a more granular level, when the spotlight is on one character, the filmmakers must choose whether to make those moments, shot by shot, highly restricted or not. In The Killers, Nick Adams’ account of Ole’s reaction to the stranger stopping for gas is more or less plausibly limited to Nick’s ken. But the precise exchange of glances between the driver and the Swede signal to us that Ole has been recognized. Nick doesn’t register this, since he’s standing at the rear of the car (barely visible in my first still, over Ole’s right shoulder).

In effect, this is a narrational aside to the audience. Nick can’t see this significant exchange of glances, and his voice-over doesn’t specify it, so we can’t assume Riordan learns of it. But this privileged moment primes us to see Big Jim as a major menace in scenes to come. This sort of deviation from what a character could plausibly know or notice is common in cinematic narration and differentiates it from literary narration, which is more tightly restricted in handling “point of view.” Classical Hollywood is biased toward unrestricted narration; radical restriction is rare. The heist genre can exploit many fine gradations between attachment to a character and more wide-ranging knowledge.

What’s our clock?

The Killing (1956).

As we’ve seen, two early instances of heist films break with a linear layout of the story. Criss Cross presents what Reinventing Hollywood calls a crisis structure, beginning just before the turning point and flashing back to show what led up to it. The Killers has a refracted narration, with all of the past events passed to the investigator Riordan and us through witnesses’ testimony. The flashbacks in Criss Cross are chronological, but those in The Killers are drastically out of order.

Time-scrambling, then, seems to be especially welcome in the heist film (as not, say, in the Western). The basic plot pattern is such a simple one that shuffling phases or parts of phases doesn’t create confusion. Yet few films of the 1950s I’ve found display the complexity of the Forties examples. Indeed, a time-juggling heist novel, The Lions at the Kill (Simon Kent, 1959) was ironed into straightforward linearity in the film version, Seven Thieves.

The Good Die Young displays a more complicated structure. It begins at a point of crisis, with four men driving in a car to the site of the caper.

The voice-over narrator introduces each man in turn, and then a long flashback explains his backstory. Deprived of information about the heist, we have to wonder how the narration will bring the men together and create their plan.

After the long section explaining each man’s circumstances, all involving women and money, the flashbacks meld. The men gradually come to know each other through frequenting the same pub. Their desperation pushes them toward accepting one man’s proposal that they rob a post office. With so much time spent on preparation and assembly, the actual planning is necessarily brief. Eventually the final flashback flows seamlessly into the present-time situation, initiating a brief replay of the dialogue in the car that opened the film. The heist (devolving into a disastrous gun battle) initiates the climax, and an airport aftermath concludes the film.

The most ambitious 1950s recasting of the nonlinear efforts of the 1940s films is The Killing (1956). The source novel, Lionel White’s Clean Break (1955) consists of interwoven threads. A crook, his pal, a cashier, a bartender, and a crooked cop conspire to rob a racetrack. They will employ helpers to start a fistfight and shoot a racehorse. The early chapters devote short stretches to following each one, already recruited, through the circumstances phase of the heist template. The men assemble at their planning meeting, which is invaded by the snoopy wife of the weak cashier. She then tells her boyfriend about the heist, so another strand involving other characters is introduced.

The most ambitious 1950s recasting of the nonlinear efforts of the 1940s films is The Killing (1956). The source novel, Lionel White’s Clean Break (1955) consists of interwoven threads. A crook, his pal, a cashier, a bartender, and a crooked cop conspire to rob a racetrack. They will employ helpers to start a fistfight and shoot a racehorse. The early chapters devote short stretches to following each one, already recruited, through the circumstances phase of the heist template. The men assemble at their planning meeting, which is invaded by the snoopy wife of the weak cashier. She then tells her boyfriend about the heist, so another strand involving other characters is introduced.

On the day of the robbery, White’s narration again attaches itself seriatim to each man as he executes his role in the scheme. While the early part of the book had a few mild jumps back in time to follow each heister, the day of the job creates extreme back-and-forth shifts. We follow the bartender, for instance, going to the track on the fateful day, before the next subchapter skips back to the cashier waking up and then going to the same train. In a later section, we skip back to the previous day and attach ourselves to the sniper who will shoot the racehorse. Because of the overlapping lines of action, the shooting of the horse and the starting of the bar fight are presented twice. Everything eventually converges on Johnny Clay, the mastermind, who breaks into the money room and steals the day’s revenue.

These temporal overlaps emerge partly from the description of the action, but they’re also marked by either characters looking at clocks or watches, or by explicit mention in the prose, such as “It was exactly six forty-five when…”

The film version makes these overlapping schedules much more explicit. A detached voice-over describing police routine or criminal behavior had become a commonplace in the 1940s, in both “semidocumentary” films and in radio drama, notably Dragnet. In The Killing, apart from lending an aura of authenticity, the voice-over exaggerates the time markers of the novel by introducing scenes crisply. The first five scenes are introduced with these tags:

“At exactly 3:45…”

“About an hour earlier…”

“At seven PM that same day…”

“A half an hour earlier…”

“At 7:15 that same night…”

These lead-ins remind us of the ticking clock, set up parallels among the characters, and get us acclimated to the film’s method of tracking one character, then jumping back in time to track another. This is moving-spotlight narration on markedly parallel tracks. The same method will be applied during the heist, when ten consecutive scenes and several others will be tagged in the same way. (“Mike O’Reilly was ready at 11:15.”)

It’s not just the repetitions that exaggerate White’s jagged time scheme. When the sniper Nikki is shot after plugging the racehorse, the narrator reports drily: “Nikki was dead at 4:24.” Cut to Johnny leaving a luggage store, and the voice-over announces: “At 2:15 that afternoon Johnny Clay was still in the city.”

The time jumps more or less buried in White’s prose are made dissonant in the film. Here the juxtaposition heightens the likelihood that Johnny’s robbery won’t go according to plan.

The replays are no less sharply profiled. As the scenic blocks move from character to character and skip back in time, they include actions we’ve already seen. The most persistent is the repetition of the track announcer’s calling the start of the crucial seventh race, but we also get replays of the wrestler Maurice starting a fight, the downing of the horse, and glimpses of Johnny waiting to slip into the cash room.

Instead of shuffling flashbacks in the manner of The Killers, The Killing offers brief time chunks stacked in slightly overlapping array until they all square up in a single moment, the consummation of the robbery. This structure allows for the sort of character delineation we find in The Asphalt Jungle while also offering the audience a formal game to enjoy. Kubrick’s film can be seen as pointing in two directions—revising the flashback format of the 1940s entries, but becoming a point of reference for later filmmakers eager to innovate games with time and viewpoint that would remain comprehensible to the audience.

The Killing helped make Clean Break White’s most famous novel. It was often republished under the film’s title. Perhaps in a grateful spirit White’s 1960 novel Steal Big (1960) included this scene.

Donovan didn’t look at the half-dozen worn, barely legible signs in the dingy lobby of the building. He went at once to the elevator and asked for the fifth floor. Getting out of the elevator, he turned left, took a dozen steps and knocked on a pebbled-glass door. The door bore the legend, KUBRIC NOVELTY COMPANY.

Mr. Kubric, it turns out, supplies illegal guns and explosives.

Art for artifice’s sake

Inside Man (2006).

White’s in-joke, along with The Killing’s gamelike approach to structure, reminds us that whatever its claim to realism, this is a highly artificial genre. The strict template and the ritualistic steps in it—recruiting the crew, casing the target, checking watches—invite filmmakers to tinker with self-conscious narration that lets the viewer in on the joke.

One convention, that of the rehearsal for the big job, is flaunted in Bob le flambeur, when the narrator simply breaks into the film with the line, “Here’s how Bob pictured the heist,” and we get a stylized, hypothetical enactment of the job carried off perfectly. In these films, when the rehearsal goes well, you know the real thing will face problems.

Something similar, though suited to light comedy, takes place in Gambit. Here we think we’re seeing the heist as executed (across twenty-three minutes), but it proves to be no more than the fantasy of the crook hatching it. Again, everything that succeeds in the fantasy goes wrong in reality.

As it gained a profile, the genre got reflexive. In the novel that was the source for The League of Gentlemen, the heisters explicitly model their plan on the one in Clean Break. The film version likewise sets its heisters mimicking a pulp novel, though it didn’t specify the title. And in The Wrong Arm of the Law (1963), Peter Sellers’ cockney mastermind promises to show his henchmen “educational films and training films” like Rififi, The Day They Robbed the Bank of England, and The League of Gentlemen.

The opportunities the genre provides for experimenting with story stratagems, sometimes in very self-conscious ways, seem to have been part of the reason later filmmakers tried their hand at it. In the 1990s and 2000s, writers and directors drawn to neo-noir and narrative experiment took up thriller conventions generally, and the heist film was one option.

In Reservoir Dogs (1992), Tarantino revived the shuffling of time and viewpoint that was ingredient to the genre. Although the film pays homage to Clean Break, its form is no less indebted to Criss Cross. Like that film, it flashes back from the day of the heist in order to run through the canonical phases of action. And as in The Killers, those phases are scrambled out of order. Brian Singer’s The Usual Suspects (1995) brings the (very ‘40s) device of the lying flashback to the genre, within the template of police questioning after the heist. Inside Man (2006) mixed to-camera narration, flashbacks, and flashforwards to interrogations after the crime.

Among Americans it’s Steven Soderbergh who has returned to the caper film most frequently. The Underneath (1995) is a remake of Criss Cross, with an extra layer of flashbacks. Logan Lucky (2017), with its deadpan redneck losers, joins the tradition of comic heist movies. Most strikingly, the Ocean’s series makes a virtual fetish of the male camaraderie and playful plot tricks typical of the genre. The films pepper the action with voice-overs, cunning ellipses, and flashbacks within flashbacks. The plots hide key information about the plan. They fill the action with in-jokes, such as a star cameo by Bruce Willis commenting on box-office grosses. Like 1960s films, they incorporate romantic comedy. In Ocean’s Eleven ((2001) Danny and Tess arrange a post-divorce reconciliation, and in Ocean’s Twelve (2004) Danny’s pal Rusty gets involved with police agent Isabel.

Piling up obstacles, reversals, bluffs, and double-bluffs, the films form a kind of anthology of the genre’s tricks. By the time we get to Ocean’s Thirteen (2007), the early phases of the standard plot schema can be given short shrift. We know the gang and its modus operandi, so the bulk of the film becomes a mind-bogglingly intricate heist including everything from planting bedbugs in a hotel room to manufacturing loaded dice in a Mexican factory under threat of strike. The network of rules and roles laid out in the 1950s—master mind, aged expert, financier, crooked helpers, allies and rivals and go-betweens and stooges—are given baroque elaboration and treated with an almost self-congratulatory panache.

So am I looking forward to Ocean’s Eight? It’s directed by Gary Ross, so I don’t expect Soderbergh’s casual sheen. And the target of the heist, a fashion show at the Met, may be a bit too on the nose; why can’t the ladies tackle a payroll or a munitions factory? Still, like a butterfly collector looking for new specimens, I’m quite curious. When it comes to narrative strategies, I’m a sucker for a fresh con.

Thanks to Jim Healy and Geoff Gardner for discussion of the genre.

Stuart Kaminsky’s American Film Genres: Approaches to a Critical Theory of Popular Film (Plaum, 1974) is a trailblazing study, and the chapter on the “big-caper” film is an indispensible starting point for studying this kind of movie. Later editions of the book eliminated this chapter. A wide-ranging recent survey is Daryl Lee’s The Heist Film: Stealing with Style (Wallflower, 2014). Alastair Phillips offers an in-depth analysis of a classic in Rififi (Tauris, 2009).

My quotations from Donald Westlake come from Murderous Schemes: An Anthology of Classic Detective Stories (Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 1 and 126. I also found the entry on Lionel White in Brian Ritt’s Paperback Confidential: Crime Writers of the Paperback Era (Stark House, 2013) helpful. The “KUBRIC” passage in White’s Steal Big (Fawcett, 1960) is on p. 47. White much influenced Westlake, as I hope to show in a future entry, but Westlake was a far superior stylist, as I discuss a little in this entry. See also this note on Levi Stahl’s anthology of Westlake nonfiction.

For more on analyzing narrative see “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative” and “Understanding Film Narrative: The Trailer.” Tarantino’s debts to the 1940s are reviewed in this entry. See as well my recent entry on thrillers. I analyze the convoluted narrative of The Killers in Chapter 9 of Narration in the Fiction Film. The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies discusses 1990s filmmakers’ relation to the Forties. Multiple-protagonist plotting is considered in Chapter 3 of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

The concept of schema and revision is considered here as applied to style; this entry, like Reinventing, applies it to narrative principles. My Dunkirk entry points out affinities between the overlapped time frames in The Killing and the three-track scheme Nolan gives us. Unlike Kubrick, Dunkirk applies the principle to the entire film and assigns each timeline a different duration, but it generates a back-and-fill organization and clusters of replays reminiscent of The Killing.

Burt Lancaster is considered here, and why not?

P. S. 26 March 2020: Thanks to Adrian Martin for correcting two slips in my account of Criss Cross!

Ocean’s Eight (2018).

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Post-partum downs and ups

The Human Comedy (1943).

DB here:

Some authors think that once their book is published they can lean back and wait to hear what people think. On the contrary. Sometimes the care and maintenance of your book continues well after the publication date.

For one book I did, the university press had promised to run an ad in Film Quarterly. When no ad appeared, I was told that since the press itself published Film Quarterly, it had to yield space to publishers who actually paid for their ads. On a more memorable occasion, a catalog listing the season’s titles from Harvard ran a picture of me that showed a different guy. Someone had chosen a shot of the distinguished literary critic and political commentator David Bromwich, who’s regrettably better-looking than me.

Most recently, I just learned that Harvard has put my On the History of Film Style out of print. (Snif.) It was a favorite of mine, and over its twenty years it sold decently, over 10,000 copies. But with all those stills it’s an expensive book to reprint, and so the rights have reverted to me. I hope to revive it somehow, perhaps in print as I did with the Harvard orphan The Cinema of Eisenstein, kindly picked up by Bill Germano, then of Routledge. Or I might go the digital route, creating a straight-up pdf of the old version (as happened with Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment), or something fancier, as with the 2.0 edition of Planet Hong Kong (another book Harvard discharged). Today we Dr. Frankenstein authors have a lot of ways to jolt our creatures back to life.

Most recently, I just learned that Harvard has put my On the History of Film Style out of print. (Snif.) It was a favorite of mine, and over its twenty years it sold decently, over 10,000 copies. But with all those stills it’s an expensive book to reprint, and so the rights have reverted to me. I hope to revive it somehow, perhaps in print as I did with the Harvard orphan The Cinema of Eisenstein, kindly picked up by Bill Germano, then of Routledge. Or I might go the digital route, creating a straight-up pdf of the old version (as happened with Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment), or something fancier, as with the 2.0 edition of Planet Hong Kong (another book Harvard discharged). Today we Dr. Frankenstein authors have a lot of ways to jolt our creatures back to life.

There are still used copies of On the History…. on Amazon. This is a Good Thing. Still, the Age of Amazon creates other post-partum problems.

In conversation and email, I’ve been hearing from people about the Big Cahuna’s treatment of my 40s book. At first Amazon promised to ship copies on the publication date, 2 October (although the University of Chicago Press was shipping copies a week or so before). Nothing happened. Then Amazon third-party sellers offered copies pronto at $30, $10 less than cover price. Then Amazon joined the fray by offering copies at $32 with Prime membership, thereby undercutting those outlets charging for shipping. This is dynamic pricing in fast motion. Such fluctuating pricing by Leviathan’s algorithms must drive publishers crazy.

Still with me? Those other outlets sold their copies, leaving Amazon the sole vendor. The price went back up to list, $40. For the last ten days Amazon has claimed that the book is out of stock, with no shipping date yet determined. This morning, the algorithm declared that one copy was available, but more were coming soon. Sure enough, as I sat down to write this entry, Amazon was offering copies, with Prime, at $40.

But I just checked again and–Amazon has just reverted to competing with third-party vendors offering it between $26 $31.71 and $41 $45.79. Who’s the nervy profiteer who charges a dollar $5.79 above list? (Prices revised as of 13 October.)

So hurry! These prices won’t last long! (Of that you can be sure.) If you want stability and fast delivery at the original price, you can go to the University of Chicago site.

I know, I know: First-world problems. So let me end by thanking two critics for their generous reviews, newly hatched. Both understood that I was aiming for a broad scope, trying to stress the breadth of storytelling innovation of the period. Given that emphasis, in Film Comment, Nick Pinkerton understood why I inserted interludes on particular films and filmmakers:

Tony Rayns in Sight & Sound rightly saw the book as trying to do something different from auteur studies, but he too got that the Interludes tried to right the balance by going deep on particular classics and directors.

Tony is right about the book’s giving Menzies short shrift, but I’ve devoted some attention to him elsewhere (here and here). Blogging has been a good way to offload material that I decided to keep out of the book. Likewise, maintaining this site allows me to post clips of 40s films I talk about. Feel free to check them out.

I thank these reviewers, and any of this blog’s readers who have bought the book.

Next up, and for free: One last big job.

Neither Nick’s nor Tony’s review is online, as far as I know.

As usual, I owe massive thanks to Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, and Kelly Finefrock-Creed. They and their colleagues have made the production, and post-production, of this book exceptionally un-traumatic.

For more background on my Forties research, see the category 1940s Hollywood. I commemorate the day I shipped out the damn thing here. No, I don’t blog in my pajamas, but I do sleep in my clothes.

P.S. 12 October 2017: Alert reader Geoff Gardner points out that today the not-so-failing New York Times published Douglas Preston’s explanation of how Amazon’s new algorithm pushes gray-market “new” books. Thanks to Geoff! Check out his Film Alert 101 blog.

The Curse of the Cat People (1944).

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past

Cover Girl (1944).

DB here:

I just got my first copy of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. I’m always scared to look at a published piece because I expect my eye to light on (a) a misprint; or (b) a sentence of unusual clumsiness or simplemindedness. Other writers have told me they have similar qualms. But I did look, and on this fat volume: so far, so good. It even has black, slightly corrugated endpapers, like the paper inside a box of chocolates.

This was a personal project for me, for reasons I’ve sketched elsewhere on this site. I grew up watching 1940s films on TV and have always had a fondness for what James Naremore has called “the beating heart of Hollywood.” In my teen years, watching Welles and Hitchcock movies along with B films and minor musicals fed my interest in studio cinema.

When I started teaching in the 1970s, I was keen to catch up with all those nifty movies sitting comfortably in our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. My classes screened His Girl Friday (in a pirate copy) and Meet Me in St. Louis and Possessed and The Locket and White Heat and The Ministry of Fear and many more. Students working with me studied Gothics, war films, and I Remember Mama. It was then I started to realize just how creative this period was.

One piece of boilerplate for the book puts it more melodramatically.

In the 1940s American movies changed. Flashbacks began to be used in outrageous, unpredictable ways. Viewers were plunged into characters’ memories, dreams, and hallucinations. Some films didn’t have protagonists. Others centered on anti-heroes or psychopaths. Women might be on the verge of madness, and neurotic heroes were lurching into violent confrontations.

Films were exploring parallel universes and supernatural dimensions. Characters switched bodies or intuited the future. Combining many of these ingredients, there emerged a new genre—the psychological thriller, populated by murderous spouses and witnesses who became targets of violence.

If this sounds like our cinema of today, that’s because it is. In Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, David Bordwell examines for the first time the range and depth of the 1940s trends. Those trends crystallized into traditions. The Christopher Nolans and Quentin Tarantinos of today owe an immense debt to the dynamic, occasionally delirious narrative experiments of the 1940s.

Bordwell shows that the booming movie market at the start of the Forties allowed ambitious writers and directors to push narrative boundaries. He traces how Orson Welles, Preston Sturges, Alfred Hitchcock, Otto Preminger, and dozens of lesser-known creators built models of intricate plotting and psychological complexity.

Those experiments are usually credited to the influence of Citizen Kane, but Bordwell shows that the experimental impulse had begun in the late 1930s, in radio, fiction, and theatre before migrating to cinema. And even with the late 1940s recession in the industry, the momentum for innovation could not be stopped. Some of the boldest films of the era came in the late forties and early fifties, when filmmakers sought to outdo their peers.

Through in-depth analysis of films both famous and virtually unknown, from Our Town and All About Eve to Swell Guy and The Guilt of Janet Ames, Bordwell analyzes the era’s unique ambitious and its legacy for future filmmakers.

Today I’d like to give you some background on the book and flag a new page on this site you might find of interest. (If you can’t wait, you have permission to go there now.)

Questions, questions

Kitty Foyle (1940).

Reinventing Hollywood turned my enthusiasm for the 1940s into a set of questions.

The enthusiasm was based on a hunch that Hollywood cinema between 1939 and 1952 saw a burst of innovative storytelling. The innovations weren’t utterly new, but they differed from what was seen in the 1930s by virtue of their range, number, and complexity. The more I looked, the more I realized that the Forties recaptured the narrative range and fluidity of silent cinema, extending and nuancing it with sound. In essence, a new set of norms emerged, forged by many filmmakers.

Several questions followed. How to describe those innovations? How to chart their range and variations? How to analyze their effects—on the sort of stories told, on how viewers understood them? How did the innovations alter genres, or create new ones? How might we explain the rise and expansion of these new norms? And finally, what sort of legacy did this process of changing conventions leave to the filmmakers that followed? In all, how did various trends coalesce into a tradition?

This plan, ridiculously ambitious, at least has the virtue of originality. Most books about the 1940s concentrate on major figures—stars, producers, directors, the Hollywood Ten. Other books explain how studios or censorship or labor disputes worked. Others focus on genres such as the musical or the melodrama or the combat film. A popular option is devoted to that not-quite-a-genre film noir. These are all worthy subjects. And there’s no shortage of books seeing 40s film as a reflection of wartime or postwar America, or the geopolitics of the Cold War.

Studying narrative norms cuts across many of these common perspectives. Individuals matter, particularly ambitious screenwriters, producers, and directors striving to tell stories in unusual ways. But institutions matter too, as studio culture and writers’ associations prized a degree of originality in plotting or point of view. And narrative devices cut across genres to a considerable degree. Although flashbacks have come to be associated with film noir, they actually appear in all genres, and take on different roles accordingly.

So, 621 films later, my project has become an effort to contribute to a history of film form—the various storytelling methods that filmmakers have developed in different times and places. (In other words, a poetics of cinema.) In effect, I’m asking that the kind of appreciation people show for genres, actors, and auteurs be stretched to narrative strategies as well.

Darryl F. Zanuck, with his shrewd narrative instinct, gave me my epigraph.

It is not enough just to tell an interesting story. Half the battle depends on how you tell the story. As a matter of fact, the most important half depends on how you tell the story.

The book in between

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

The project blended in with earlier work I’d done, particularly in The Classical Hollywood Cinema and The Way Hollywood Tells It. In a sense, Reinventing Hollywood is a bridge between those two books.

CHC, written with Kristin and Janet Staiger, traced continuity and change in the studio storytelling tradition from its inception to 1960. It analyzed how conventions of story, style, and work practices were established and maintained over the decades. The Way Hollywood Tells It suggested that after 1960, the broad conventions remained in place but were modified in particular ways.

In passing, I suggested that innovations of “contemporary Hollywood” owed a lot to experiments launched in the 1940s. The new book tries to pay off that IOU. Reinventing Hollywood asks how, within the broad conventions of classical Hollywood, particular innovations could emerge in the boom-and-bust 1940s. Many standard devices of our films today, from voice-over and fragmentary flashbacks to block construction and tricks with point of view, can be traced back to the Forties, when they were consolidated and refined.

The two earlier books also considered film technique—staging, shooting, editing, and the like. Reinventing Hollywood doesn’t tackle visual style, for two reasons. It would have doubled the book’s length, and I’ve said my say on 40s style in other work. Style shapes story, of course, and I’ve tried to take this factor into account. But I concentrate on the principles of story world, plot construction, and narration—the three dimensions of narrative I’ve outlined elsewhere.

None of these books is auteurist in basic orientation, but they aren’t anti-auteurist either. Surveying techniques in a systematic way helps call attention to adepts, middling talents, and innovators. In Reinventing, I think the interludes on Mankiewicz, Sturges, Welles, and Hitchcock show how skillful filmmakers mobilized emerging conventions in powerful ways. In effect, we reconstruct a menu of options to sense the values in picking and mixing them. For example, Citizen Kane‘s investigation plot, adorned with a dying message and a bevy of flashbacks, was a vigorous synthesis of devices that were circulating through film and other media in the late 1930s. The boldness of the effort made it influential on what followed. We get a better sense of directors’ (and writers’ and producers’) idiosyncratic strengths when we know the norms they’re working with, and sometimes against.

Reinventing Hollywood, running nearly 600 pages, makes The Rhapsodes look scrawny. But it isn’t the behemoth that CHC is. CHC could give this book noogies.

The big and the small

The Bishop’s Wife (1947).

It was hard to discuss broad trends and still probe particular cases in detail. So the chapters move from generalities to specifics in steps. Some films are merely mentioned, others described briefly, others considered at greater length, and some analyzed in depth. After a conceptual introduction and a historical panorama of Hollywood as a creative community (Chapter 1), there are chapters on flashbacks, plot construction, woven versus chaptered plots, manipulation of viewpoint, voice-over, character subjectivity, psychoanalytic plots, realism and fantasy, mystery plots, and self-conscious artifice. The conclusion looks at the impact of the period on later filmmakers.

I try to go beyond obvious observations to study the mechanics of familiar devices. So I come up with terms and concepts to pick out finer-grained tactics: the breadcrumb trail that sets up many flashbacks, block construction, hooks, switcheroos, and the like.

The chapters on particular techniques are broken by “interludes” devoted to particular movies or moviemakers. Some of these interludes involve well-known films and figures, but others look at obscure items. (Yes, The Chase is involved.) Even the treatment of Big Names tries to offer something original, as when I argue that Hitchcock and Welles pushed 40s innovations very far and sustained them throughout their later careers.

Here’s the table of contents, with small annotations

Introduction: The Way Hollywood Told It

Chapter 1: The Frenzy of Five Fat Years (Hollywood as an ecosystem)

Interlude: Spring 1940: Lessons from Our Town

Chapter 2: Time and Time Again (flashbacks)

Interlude: Kitty and Lydia, Julia and Nancy

Chapter 3: Plots: The Menu (conventions of plot structure)

Interlude: Schema and Revision, between Rounds

Chapter 4: Slices, Strands, and Chunks (alternative structural options)

Interlude: Mankiewicz: Modularity and Polyphony

Chapter 5: What They Didn’t Know Was (managing narrative information)

Interlude: Identity Thieves and Tangled Networks

Chapter 6: Voices out of the Dark (voice-over)

Interlude: Remaking Middlebrow Modernism

Chapter 7: Into the Depths (subjectivity)

Chapter 8: Call It Psychology (psychoanalytic films)

Interlude: Innovation by Misadventure

Chapter 9: From the Naked City to Bedford Falls (realism, fantasy, and in-between)

Chapter 10: I Love a Mystery (thrillers and mystery-based plotting)

Interlude: Sturges, or Showing the Puppet Strings

Chapter 11: Artifice in Excelsis (self-conscious display of conventions)

Interlude: Hitchcock and Welles: The Lessons of the Masters

Conclusion: The Way Hollywood Keeps Telling It (legacy of the 1940s)

To keep things specific, I’ve prepared eleven film clips keyed to particular analyses. Just playing the clips might give you a sense of the book’s range. They’re also fun in their own right.

No zeitgeists, please

Blues in the Night (1941).

Two last points. One bears on preferred explanations. How do we explain why cinematic innovation burst out at this particular time? Again, the book tries to pursue an uncommon path.

Many writers look to a zeitgeist—the anxieties of war, the anxieties of postwar adjustment, the anxieties of the anti-Communist crusade, any anxiety you can imagine. Instead I try to look for institutional factors shaping the films’ norms. Centrally, there are the conditions of the film industry, with its rich interplay of personnel and story materials shuttling all over the place. There are also the cinematic traditions themselves, such as plots depending on amnesia. Particularly important are the adjacent arts, including theatre, radio, and popular fiction. All these sources get modified by a process of schema and revision—borrowing something already out there but warping it to new ends. In short, instead of looking for remote causes in the broader society, I try to locate more proximate ones within the filmmaking community and the turmoil of popular culture.

Someone might argue that this just pushes the problem back a step. Don’t social anxieties surface in all these media? To this I’d argue, as I did here and here, that those anxieties are very hard to identify. Not all anxieties or concerns will be shared by a populace (viz. our current political situation). And we can’t establish a strong causal connection between them and the products of popular media—especially since media are indeed mediated, by tastemakers, gatekeepers, and the institutions that produce popular culture.

For the period I’m concerned with, James Agee noted the role of mediators in his complaints aimed at the film-as-dream sociologists of the period:

It seems a grave mistake to take [movies] as evidence as definitive, as from-the-public, as if 40 million people had actually dreamed them. Take the far simpler case of advertising art. The American family, as shown therein, is not only not The Family; it isn’t even what the American people imagines as The family. It is A’s guess at that, subject to the guesswork of his boss, which is subject in turn to the guesswork of the client. At best, a queer, interesting, possible approximation, but certainly never definitive. In movies many more people take part in the guesswork, but not enough to represent a population: and many more accidents and irrelevant rules and laws deflect and distort the image.

A movie does not grow out of The People; it is imposed on the people— as careful as possible a guess as to what they want. Moreover, the relative popularity or failure of a picture, though it means something, does not at all necessarily mean it has made a dream come true. It means, usually, just that something has been successfully imposed.

Instead of social reflection, we should expect refraction. Decision-makers opportunistically grab memes and commonplaces (the unhappy housewife, the juvenile delinquent, the returning vet) in hopes they can make something appealing out of them. They absorb those into familiar (narrative) forms. We get, then, not a “vertical” or top-down flow of social anxieties into artworks, but a “horizontal” ecosystem, a dynamic of exchange and transformation. The creators copy one another, obeying local norms while also resetting boundaries. This process includes selective assimilation of ideas thrown up by the culture, and it gets amplified by network effects, as sticky ideas themselves get copied. In other words, ideology doesn’t turn on the camera. The final film is always mediated by humans working in institutions, and both the people and the institution have many agendas.

A second point follows. Working on this book brought home to me how much film owes to other media. In a way, Forties cinema became more “novelistic” because it sought to assimilate techniques of split viewpoints, replays, inner monologue, and subjective response characteristic not so much of modernism (those were old hat by the 1940s) but of popular fiction and what we might call “middlebrow modernism.” A Letter to Three Wives (1948) attaches itself in turn to three women, each with memories of the past, with that trio interrupted by a never-seen fourth woman mockingly narrating the tale. It’s a cinematic treatment of the shifting viewpoints and personified narrative voices to be found in the nineteenth-century novel (Dickens, Collins, James) and later in genre fiction, not least in mystery tales. (It’s also a modification of the source novel.)

But you could also argue, as André Bazin did, that the 1940s saw a new “theatricalization” of cinema, with self-conscious adaptations that stressed stage conventions like the single-setting action. And of course radio supplied important prototypes for acoustic texture and first-person voice-over. Each of these devices wasn’t simply ported over to film; moving images and recorded sound gave literary, theatrical, and radio-based techniques new expressive possibilities. And all depended on the churn of people working side by side to innovate within familiar norms.

Every author discovers or remembers too late those things that should have been mentioned. Doug Holm reminded me of the dream narrative of Sh! The Octopus (1937). Jim Naremore pointed out that Rex Stout had already done my work for me in Too Many Women (1947, year of my birth), when Archie reports, “It was a wonderful movie . . . Only two people in it have amnesia.” On a different pathway, I’d love to do more research on moguls’ screening rooms as a condition of influence. (They could borrow films from rival studios without charge.) Julien Duvivier is a minor hero of my book, but only after the book was submitted did I see his L’Affaire Maurizius (1954), a perfect extension of 1940s storytelling to a French milieu.

And just recently I found a nice confirmation of the unexpected byways of the ecosystem. According to the author, the figure of the “psycho-neurotic” returning soldier was at first mandated by government policy but then twisted by ambitious screenwriters into tales of civilian madmen. The article has the enviable title: “That Psycho Story Swing Is No Cycle; It’s Now an Obsession.” If you buy the book, please write that into the endnotes.

And for the third time, feel free to visit the clips page!

I owe a lot to several people who saw this book through publication. Foremost are my editor at the University of Chicago Press, Rodney Powell, and his colleagues Melinda Kennedy and Kelly Finefrock-Creed. Then too there is Bob Davis, who supplied the book’s jacket photograph; Kait Fyfe, who prepared the clips for posting; and web tsarina Meg Hamel who set up the clips page. My other debts are recorded in the acknowledgments, but of course I must mention Kristin who had the hardest job of all. She had to put up with the author.

My Agee quotation comes from “Notes on Movies and Reviewing to Jean Kintner for Museum of Modern Art Round Table (1949),” in James Agee, Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, and Manuscripts, ed. Charles Maland (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2017), 975. I’m indebted to Chuck for sharing this with me. Chuck’s discussion of Agee on our site is well worth a read.

Many entries on this site are dedicated to 1940s Hollywood. See the relevant category. “Murder Culture” has been revised as a chapter in the book. On 1940s visual style, see Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema, Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style, and entries under 1940s Hollywood. There’s also the web essay on William Cameron Menzies. My most detailed arguments against social reflection and zeitgeists in historical explanations comes in the title essay in Poetics of Cinema, pp. 30-32.

Although the Amazon page offering Reinventing Hollywood says copies aren’t available until October, it seems that copies are shipping now from Chicago’s webpage. Amazon offers no discount on the title. (See P.S.) It’s currently available only in hardcover, with a paperback planned for the distant future.

P.S. 27 Sept 2017: Actually, Amazon is now discounting Reinventing Hollywood; it’s $30.77, as opposed to the $40 list price.

P.P.S. 13 October: Amazon’s prices on the thing have been fluctuating wildly. See this entry. Those wild and crazy algorithms!

Our Town (1940).

MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario

DB here:

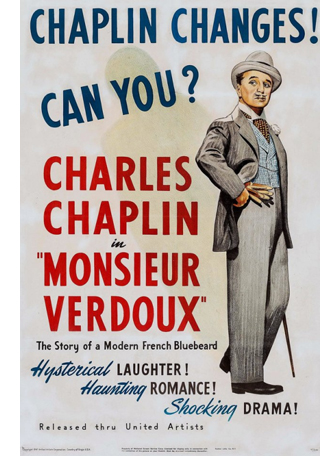

The newest installment of our Criterion Channel series on FilmStruck is now up. There I try to look at Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux (1947) from a fresh perspective: as a perverse contribution to the serial-killer cycle of the 1940s. You can sample it on the Criterion blog.

The killers inside them

When we say that we take up a new perspective on a film, or any artwork, what are we doing? I think the process involves at least two things. First, you need categories, some fresh conceptual groupings that allow for a perspective shift. Second, you relate the film in question to other particular films—that is, you pick prototypes of the categories. People don’t realize, I believe, the extent to which picking prototypes shapes our reasoning about nearly everything. (Is your prototype of a horror film Cat People, Halloween, or Saw? You’ll think of the genre differently.)

Take film noir. The category didn’t exist in 1940s Hollywood; no producer or director or writer set out to make a noir. A film might be a thriller, crime melodrama, even a horror movie. I discuss the elasticity of these categories here. When French, then American critics started talking about film noir, they were creating a perspective shift. The new category “film noir” pulled together several aspects of films that hadn’t seemed so salient in their day: skepticism about orthodox authority, for example, or suspicion of women’s sexuality. Similarly, the critics elevated certain films, like Double Indemnity and The Big Sleep and Possessed, to the status of prototypes, and less vivid examples were situated in relation to them.

Something like this perspective shift occurred to me when I was writing my book, Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. I tried to come up with some categories that could show continuity and change in film narrative of the period. I looked for strategies of plotting and narration that cut across received categories like genre. Among the categories I explored are block construction, multiple-protagonist plots, subjective viewpoint, non-chronological story sequence, voice-over narration, and others. Some had come to be associated with certain genres (thanks again to prototypes), but I found that they were quite pervasive. Several of these I’ve tried out on the blog.

Once I was peering through the lenses of these categories, my prototypes changed too. Now little-discussed films like Our Town (1940) and Tales of Manhattan (1942) and The Human Comedy (1943) and The Chase (1946) became surprisingly central. I couldn’t ignore the classics, but they were now lit by a crosslight that brought out fresh aspects. And with these categories of narrative technique in mind, we can discover some new sides of well-known auteurs, like Welles, Hitchcock, Sturges, and Mankiewicz.

One broader category I tried out was that of “murder culture.” Mystery and suspense are perennial narrative appeals, but they took on new power in in fiction, film, and theatre of the Forties. (An early version of the chapter’s case is made here.) Part of murder culture was the rise of the serial-killer tale—not new in the 1940s, of course, but more common than in earlier Hollywood eras. Films like Shadow of a Doubt (1943), The Lodger (1944), Bluebeard (1944), Hangover Square (1945), Lured (1947), Follow Me Quietly (1949), and others became prototypes for my purposes.

Then Monsieur Verdoux appeared in a new light. What better evidence of the pervasiveness of murder culture than the effort by the most-loved film star in history to play a serial killer?

Landru in LA

Orson Welles and Charles Chaplin, Brown Derby restaurant, March 1947.

It was Orson Welles who prompted Chaplin to make Monsieur Verdoux. Welles was a thriller fan. He carried a trunkload of crime novels around on his travels. One of his early RKO projects was an adaptation of Nicholas Blake’s Smiler with a Knife, and after the debacle of It’s All True, his work as a freelance director consisted of thrillers (The Stranger, The Lady from Shanghai, Mr. Arkadin) and Shakespeare adaptations (Macbeth, Othello). Indeed, he treated Shakespeare’s plots as thrillers, in accord with his belief that the Bard wrote not classical tragedies but blood-and-thunder melodramas.

According to biographers, Welles wrote a screenplay based on the wife-murderer Landru and offered the role to Chaplin. Chaplin at first accepted, then decided to direct the film himself and bought the idea from Welles. There was apparently some dispute about giving Welles credit; early prints are said to have lacked acknowledgment of Welles’ idea as the source.

By late 1941, the trade press reported that Chaplin was preparing the film, then called “Lady Killer.” A year later, it was still discussed as a “plan.” Chaplin didn’t finish the screenplay until 1946, and the film was shot between May and September. By then it was entitled “A Comedy of Murders,” although Chaplin toyed with “Bluebeard” and “Bluebeard Rhapsody.” It wasn’t released until spring of 1947.

This long gestation period is significant because when Chaplin started, the idea of a comedy about killing would have been fairly fresh. By the time Verdoux was released, however, Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) and Murder, He Says (1945) had already shown that audiences would accept humor mixed with homicide. The original stage production of Arsenic and Old Lace had opened to great success in January of 1941, and it’s interesting to speculate that it might have encouraged Chaplin to buy Welles’ Landru idea.

Both Arsenic and Murder, He Says treat murder with a consistently farcical tone. I suggest in my FilmStruck Observations episode that Chaplin risks something more complex. For one thing, he takes the conventions of the serial-killer film more seriously than the other films do. He goes on to amplify and exaggerate those conventions in fascinating ways. For instance, he makes the policemen more or less stick figures, so we don’t care if they’re in jeopardy. In turn, Verdoux tries to win our allegiance through clumsy efforts to be debonair. (Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt is far more poised.) Chaplin’s use of the cycle’s conventions gets pretty specific. There were dead narrators in 40s films before Sunset Blvd. (1950), but we tend to forget that Chaplin uses the same device in Verdoux.

Going further, I discuss how Chaplin’s treatment of serial killing mixes different sorts of comedy—social satire and slapstick, the traditional comedy of manners and the comedy of ideas associated with George Bernard Shaw. This mix is rather discordant, and it’s responsible, I think, for much of the criticism the film attracted, then and now.

The Tramp as provocateur

Verdoux failed in the US for several reasons. Reviews were mostly unsympathetic, even harsh. Chaplin had been back in the headlines thanks to a messy paternity suit filed by Joan Barry. His reputation as a seducer of young women had unpleasant associations with Verdoux’s conquests. He was also known for his support for liberal causes and his strong stance against fascism. After the war, he was more and more reviled by right-wing politicians and activists. Chaplin’s defense of civil liberties made him seem too much a Communist dupe, or an active sympathizer. Charles Maland has suggested that the film’s promotion completely mishandled Chaplin’s star image.

The disgraceful New York press conference on the film was chronicled in the New Republic:

The disgraceful New York press conference on the film was chronicled in the New Republic: