Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

Waldo Lydecker, James Schamus, and 1910s movie storytelling

Laura (1944).

DB here (in DC):

Over the next two weeks I’m involved with several events during my stay at the John W. Kluge Center of the Library of Congress. If you’re near Washington, do consider coming to one or all of these doings.

First up is a screening of a sparkling restored print of Otto Preminger’s Laura (1944), at the gorgeous Packard Campus Theater in Culpeper, Virginia on 8 March. The show, a new addition to the Theater’s spring schedule, starts at 7:00 pm, a half-hour earlier than the customary time. I’ll be giving a brief introduction.

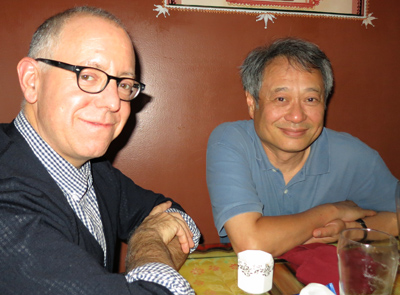

On the following Monday, 13 March, the Kluge Center will host “James Schamus on Philip Roth and the Art of Adaptation.” After a screening of James’s directorial debut Indignation, he will participate in a discussion with the audience. I’ll play moderator. The event will take place at 3:00 pm in the Pickford Theater, on the third floor of the Library’s Madison Building, 101 Independence Ave. S.E.

James, professor at Columbia and producer and writer of many important American and Chinese films, needs no introduction to this blog’s readership. (Above, he’s with frequent collaborator Ang Lee.) We’ve celebrated his work here, and I discussed the admirable Indignation just last summer. This upcoming session should be an exhilarating afternoon.

Lastly, I’m giving a talk, “Studying Early Hollywood: The Search for a Storytelling Style.” It develops some of the issues I’ve floated in my books, other lectures, this video lecture, and most recently this blog entry. The talk is set for 4 pm. on Thursday, 16 March. It takes place in room 119, a magnificent venue on the first floor of the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building, 10 First St. S.E.

All these events are free and open to the public, and you don’t need tickets.

Being at the Kluge Center has been very stimulating, and my research into 1910s visual style has benefited hugely from access to the LoC’s film collections. These three events are wonderful ways to wrap up a stay that has gone by all too fast. If you’re in the vicinity, come by and say hello.

Thanks to the many people who have made these events happen: At the Kluge Center Ted Widmer, Mary Lou Reker, Dan Turello, Travis Hensley, and Emily Coccia; at the Packard Campus Greg Lukow, Mike Mashon (initiator of many things), and David Pierce.

More information on the Packard Campus Theater is here. A summary of James’s vast career is here.

The Packard Campus Theatre. Photo by Glenn Fleishman.

My girl Friday, and his, and yours

DB here:

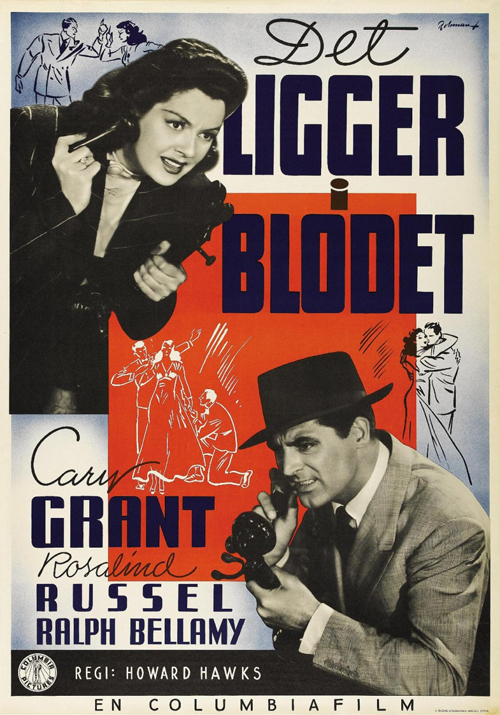

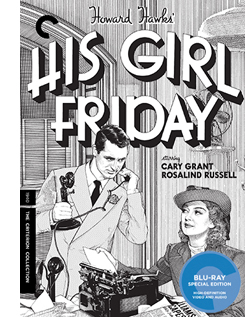

Criterion has just released a fine edition showcasing two classics of American cinema: The Front Page (1930) and His Girl Friday (1940). His Girl Friday is in a new HD restoration, and the earlier film, long crawling around in disgraceful public-domain bootlegs, now has a 4K glow–maybe looking better than it did at the time. The extra fillip is that it’s a version that director Lewis Milestone preferred to the familiar one.

Along with the films comes a host of features: interviews and shorts about Howard Hawks, Rosalind Russell, and the making of HGF, radio adaptations of both the Front Page play and the HGF film, a short about Ben Hecht, trailers, appreciative essays by Michael Sragow and Farran Smith Nehme, and a session with me about HGF.

Along with the films comes a host of features: interviews and shorts about Howard Hawks, Rosalind Russell, and the making of HGF, radio adaptations of both the Front Page play and the HGF film, a short about Ben Hecht, trailers, appreciative essays by Michael Sragow and Farran Smith Nehme, and a session with me about HGF.

Needless to say, I’d be plugging this release strenuously even if I weren’t involved. Long-time readers of this blog know that an early entry hereabouts talked about the diverse paths HGF took to becoming the classic it’s now recognized to be. I used the film in many courses I taught during my early days at Madison. Kristin and I have been writing about the film since then as well, first in Film Art (it still retains its place from the 1979 edition), then in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985) and On the History of Film Style (1998). Other references sneak into our entries here from time to time. The Criterion edition offered me another chance to rattle on about a movie I still, after nearly fifty years, love inordinately.

What can be left to say? Plenty, but today I’ll mention just two items. First, what is a Girl Friday? And second, how unobtrusively delicate can film style be?

More slop on the hanging

The phrase “girl Friday” comes, ultimately, from Robinson Crusoe, Defoe’s 1719 novel of how the castaway protagonist turned a cannibal prisoner into his servant: his man, Friday. The hapless convert to Christianity gained his name because Crusoe rescued him on a Friday. An 1867 children’s story, “Will Crusoe and His Girl Friday,” shows a little boy and girl planning to reenact Defoe’s tale, adding gender insult to racial and class injury.

“My Girl Friday” was a spicy 1929 play about flappers who drug tycoons at a party and then convince them that the worst has happened. Consisting largely of scenes with chorus girls in bathing suits, it was dubbed by Variety “out and out smut.” Unsurprisingly, it found success on Broadway. During some weeks its BO take rivaled that of The Front Page, on stage at the same time.

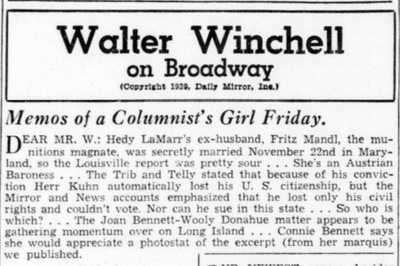

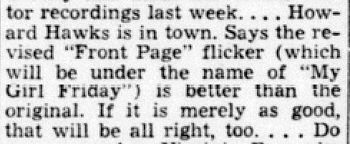

As far as I can tell, the phrase “girl Friday” became more prominent in American slang during the 1930s, thanks chiefly to columnist Walter Winchell (right, from Time 1938). At intervals from 1934 on, Winchell’s daily column carried the title “Memos of a Columnist’s Girl Friday.” The premise was that his secretary was an all-purpose newshound, gathering gossip and tidbits into a weekly memo to her boss. Evidently, Winchell’s secretary Ruth Cambridge (Mrs. Buddy Ebsen) didn’t write it. Under the “Memos” rubric Winchell could boast about his latest triumphs. His Girl Friday could ask innocently if “Mr. W.” saw the new Fortune poll of top columnists (in which he ranked high), or whether he noticed that several more newspapers had signed on to carry the column. Louella Parsons gave Winchell credit for publicizing the Girl Friday phrase.

As far as I can tell, the phrase “girl Friday” became more prominent in American slang during the 1930s, thanks chiefly to columnist Walter Winchell (right, from Time 1938). At intervals from 1934 on, Winchell’s daily column carried the title “Memos of a Columnist’s Girl Friday.” The premise was that his secretary was an all-purpose newshound, gathering gossip and tidbits into a weekly memo to her boss. Evidently, Winchell’s secretary Ruth Cambridge (Mrs. Buddy Ebsen) didn’t write it. Under the “Memos” rubric Winchell could boast about his latest triumphs. His Girl Friday could ask innocently if “Mr. W.” saw the new Fortune poll of top columnists (in which he ranked high), or whether he noticed that several more newspapers had signed on to carry the column. Louella Parsons gave Winchell credit for publicizing the Girl Friday phrase.

He started a brief feud when he smelled poaching. In 1937, two aspiring screenwriters sold MGM a story they called “My Girl Friday.” It involved, according to Daily Variety, “adventures of a newspaper circulation rustler.”

With Trumpian self-regard, Winchell asserted that he had popularized many catchphrases that Hollywood had bought as titles: “Blessed Event,” “Orchids to You,” “Is My Face Red?” “Okay, America,” and even “Whoopee.” In addition, he noted that MGM had spent a cool quarter of a million dollars to enhance a scene of The Great Ziegfeld. In the face of such largesse, Winchell felt justified in asking for compensation.

Therefore we think it would be ducky if MGM sent $10,000 to us for the use of “My Girl Friday,” which became better known via this dep’t.

Winchell hastened to add that he would give the money to charity. He pressed his case in several columns and in radio broadcasts. Paramount joined the fray, claiming that it acquired the title when it bought the old play, so MGM couldn’t use it anyway. At which point the Hays Office was consulted.

Using his Girl Friday voice, Winchell responded that he claimed only to have popularized the phrase, and in any case what was $10,000 to Hollywood, especially if the money went to charity? Muttering about how MGM’s song “Your Broadway and Mine” swiped the original title of his column, Winchell subsided, as did the dispute. MGM evidently never adapted the story in question.

Then, on 9 December 1939, Walter ran this.

No hard feelings from Winchell, apparently. He may have benefited from the association with the movie. During production and even after release, the film was sometimes called My Girl Friday. And the linkage of a Girl Friday to the newspaper game, be it gossip or circulation rustling, fitted the movie well, as it evoked Winchell’s rat-a-tat radio delivery and his near-prosthetic adhesion to phone receivers.

Yet Winchell mysteriously dropped the “Memos” rubric from his column in 1941. In the decades to come, many businessmen would claim to have a Girl Friday of their own. Maybe the film ultimately popularized the phrase more successfully than Winchell did.

For the waiter

Daily Variety (5 January 1940), 3.

As a theatrical adaptation, His Girl Friday offers a challenge that Hawks accepted with ease. He had worked on films limited to a few interiors before, as with the train scenes of Twentieth Century (1934) and much of the airport action of Only Angels Have Wings (1939). He knew how to enliven situations unfolding in tightly confined settings.

Apart from enjoying the fast-paced comedy, you can learn a lot about film technique from the way Hawks energizes his static, prosaic surroundings. Take his resolutely unflashy staging in depth. It’s most apparent in the pressroom of the Criminal Courts Building, as I suggest in the supplement, but there are plenty of felicities of staging elsewhere. The most apparently unpromising example involves the restaurant where Walter Burns takes his ex-wife Hildy Johnson and her fiancé Bruce Baldwin. What to do with this simple set?

At a late point in the scene Walter will seek the help of the waiter Gus, who’ll call Walter to the phone. It’s a basic problem: How should the director prepare for that phase of the action? Hawks does it by setting up a zone of depth at the start of the scene, priming it quietly throughout, and paying it off when it’s needed.

Bruce, Walter, and Hildy enter the restaurant from the background. (Novice directors please note: No need for a sign saying, “Restaurant.”) The group comes to a table in the foreground. After some comic byplay as Walter grabs the chair next to Hildy, the three get seated and chat with Gus.

This framing orients us to the table and the rear area by the bar. We’ll never leave this general orientation on the scene. This commitment, far from being simply “theatrical,” makes for economy as the action develops.

In the course of the scene, Hawks activates the rear zone by having Gus come and go from it. Of course that area isn’t emphasized. Who’s likely to notice Gus giving the sandwich order back there when there’s patter and funny business to watch right in front of us?

In the course of the scene, Gus will come back to the table, pouring water, delivering sandwiches, and getting kicked in the shin by Hildy, who’s aiming at Walter. Throughout, we’re quietly primed for that alley of space behind Walter to be occupied by Gus.

The priming pays off when Walter, realizing that he has to prevent Hildy’s taking the train today, deliberately spills water in his lap.

Walter pivots and heads to Gus, who’s back there in his domain, waiting to be pulled into the plot. He’ll summon Walter to the fake phone call.

No big deal–certainly not as eye-catching as the dazzling comedy around the table. But the care for such little things is the mark of a craftsmanship that uses space compactly, without fuss. No need for camera angles that show the fourth wall (or even walls two and three). No need to build more of the set on the side; this is Columbia, after all. Just let reliable Joe Walker light that background enough to keep us aware of it (out of focus for most of the scene) and then activate it when you need it.

Hawks was obeying the advice Alexander MacKendrick would later give:

Within the same frame, the director can organize the action so that preparation for what will happen next is seen in the background of what is happening now.

Or as Hawks put it in 1976:

You know which way the men are going to come in, and then you experiment and see where you’re going to have Wayne sitting at a table, and then you see where the girl sits, and then in a few minutes you’ve got it all worked out, and it’s perfectly simple, as far as I am concerned.

The unstated premise is indeed perfectly simple: You don’t need to show more space than the physical action requires. It’s a rare premise today.

How long is it?

This sort of priming fits neatly into a cinema based in continuity–dramatic, spatial, temporal. Hawks is a master of staging action so that it flows unobtrusively. At times, though, it’s fun to spot some discontinuities, and editing is a good place to look.

Ozu is, to my knowledge, the only director who invariably creates perfect match-cuts on action. Even Hawks has to cheat things a bit to make the editing flow. (Hildy’s pitching of her purse is an example I use in the commentary.) But consider how Hawks can get a spark out of a small, mismatched action.

We’re still in the restaurant, and Walter has persuaded Hildy to cover the Earl Williams story in exchange for buying an insurance policy from Bruce. Talking of his upcoming physical, Walter boasts, “Say, I’m as good as I ever was.” Hildy fires back, “That was never anything to brag about,” and Walter reacts and turns his head. As he turns, we get these two shots.

At first Walter is stunned, apparently readying a reply; but at the cut, he’s sporting a grin. It’s partly a grin of triumph, showing that he’s gotten Hildy to do his bidding, but it’s also an appreciation of her wit: a sort of “That’s my girl” pride in her fast comeback. Strictly speaking, the cut’s a mismatch, but the instantaneous switch in reaction gives the scene double value.

Finally, there’s framing. The rugged outdoor guy Hawks is as delicate as they come when it’s a matter of frame corners and edges, and his sense of pictorial balance is fastidious. Go back to the long opening scene in Walter’s office, when he and Hildy are going through the preliminaries. They size each other up before Walter sits down in his swivel chair.

A slight track forward has planted Walter in the lower corner of the frame. A cut in to Hildy’s reaction (not shown) enables a transition to a slightly different framing. That setup allows Walter to invite her onto his knee, which pokes up from the bottom edge.

Joe Walker has obligingly edge-lit that stretch of pant leg, and it’s about the only thing moving in the shot, so we can’t miss Walter’s come-on.

Now Hawks does something very pretty. Hildy moves to the table and perches on it. Hawks reframes with her, but keeps the shot oddly unbalanced, with Walter resolutely facing the area she’s not in.

A sort of spatial suspense develops. Hawks sustains this odd framing while Walter picks up a cigarette, tosses one to Hildy, lights up, and tosses her a match. Fairly deliberately too, in what’s supposed to be Hollywood’s fastest movie.

When both are smoking comfortably, Walter swivels his chair to snap his head into the lower left corner, which has been waiting for him all along. The simple movement provides the scene’s new beat, which starts with Walter’s line: “How long is it?” I haven’t yet mentioned that this is a fairly dirty movie, but you knew that.

The shot began with the actor’s head in the lower right, developed with that head poised midway in the frame, and now ends with the head cocked in the lower left. What looks like sterile geometry feels, on the screen, perfectly unforced. And lest we misread the “How long is it?” Walter innocently explains, in a medium shot, that he’s just wondering how long it’s been since they’ve seen each other. That in turn calls up an over-the-shoulder reverse angle, and the next phase of the scene is off and running.

At this point in film history, the cinematographer, while shooting, could not see exactly what the lens was taking in. The careful unbalancing and rebalancing of the shot had to be achieved through a mixture of expertise and intuition. The same thing with keeping Gus in reserve back there by the bar, and letting an incompatible take of Grant’s reaction stay in after a cut. It’s all perfectly simple, as far as I’m concerned.

Thanks to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and Peter Becker of Criterion for inviting me to spend more time with this splendid movie. Hawks’ quotation about keeping it simple comes from my On the History of Film Style (Harvard University Press, 1997), 149.

You can find background here on the restoration of The Front Page, supplied by Academy archivists Mike Pogorzelski and Heather Linville.

You can get a sampling of Winchell’s radio delivery from the period here, complete with nervous teletype clackings serving as transitions. For more background on HGF, go here. That entry observes the usefulness of the film’s lines in many situations. In this respect it resembles another Hawks film, that repository of worldly wisdom known as Rio Bravo.

Gus the waiter is played by the inimitable Irving Bacon, one of a dozen or so outstanding supporting players. This is another of the film’s triumphs: Regis Toomey, Porter Hall, Gene Lockhart, Abner Biberman, Roscoe Karns, and other memorable character actors all seem to be having fun. And Billy Gilbert as the wayward Pettibone is the friendliest deus ex machina in Hollywood cinema.

Finally, do audiences today know the meaning of Hildy’s flipped hand in response to one of Walter’s catty remarks? Has nose-thumbing gone out of popular culture? Apparently not.

P.S. 4 February 2017: On the Parallax View site, Sean Axmaker has the most in-depth appreciation of this edition of The Front Page I’ve seen online. And he has plenty to say about HGF too.

P.S. 2 February 2018: His Girl Friday is now streaming on FilmStruck, and among the bonus materials is the video essay I mention.

His Girl Friday (1940).

Fantasy, flashbacks, and what-ifs: 2016 pays off the past

La La Land.

DB here:

After I see a new movie, I like thinking about its ties to film history. This isn’t a matter of sneering, “They did it better in the old days,” though often that’s true. Rather, I like exploring how our films both rely on and swerve from the traditions they invoke.

I’m not talking only about movies that self-consciously point at Hollywood’s past, as La La Land does. Every new release participates in film history—and sometimes changes it. Most critics don’t have the space or inclination to point this up, but those of us who study film as an art can. Looking closely at form and style makes the past present to us in a vivid way.

Students are taught that in the 1910s Griffith took crosscutting to a new level, and true enough. But it’s not often mentioned that crosscutting has remained a permanent expressive option for filmmakers today. Very often they use it as Griffith did: to build tension, especially in a chase or a race against time; or to highlight narrative parallels, as he did in Intolerance. What excites young audiences in the work of Christopher Nolan, for example, are in large measure smart elaborations on principles that go back a hundred years.

This isn’t to complain that Nolan isn’t original—originality in the strong sense is very rare—but rather to point up an overarching dynamic of continuity and change across the history of the art. We understand what Nolan’s doing better when we see how he recasts inherited techniques, as when Inception takes parallel crosscutting to a kind of limit in its embedded dreams.

My upcoming book, Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, is an effort to refine an argument I made in The Way Hollywood Tells It: that major narrative techniques of contemporary cinema got consolidated in the 1940s. The techniques I have in mind include general principles like non-chronological plotting and subjective probing of character’s experience, as well as particular devices like flashbacks, voice-over, and fantasy scenes.

I say “consolidated” because many of those strategies can be found sporadically in the silent era and the 1930s. Forties writers and directors adapted them to the sound cinema, made them popular, and explored them in ways that go beyond most earlier instances. These filmmakers added a body of resources to the classical tradition: after the 1940s, later filmmakers could develop the techniques in fresh ways. There were new colors on their palettes.

I talk about several films, and among those I significantly spoil The Shallows, Manchester by the Sea, The Birth of a Nation, Nocturnal Animals, Moonlight, and La La Land. But you should be able to skip the films you fear I’ve overshared on.

Schemas and their sneaky ways

Reinventing Hollywood argues that we can understand the process as one of schema and revision. I borrow from E. H. Gombrich the idea that a schema is a pattern handed down by earlier artists that becomes a point of departure for those who follow.

For example, shot/reverse-shot cutting is a stylistic schema, going back to the 1910s. Every professional filmmaker knows how to execute it, though some will find fresh ways to use it. The Shallows, a summertime thriller from the talented director Jaume Collet-Serra, uses it in orthodox ways throughout.

Most filmmakers apply the shot/reverse-shot schema to phone conversations as well. But here Collet-Serra innovates (mildly) by using cellphone technology to give us a phone conversation with a redoubled shot/reverse-shot pattern. The editing schema is given within a single frame as Nancy talks with her father.

This isn’t, I think, a mere gimmick. For one thing, we’re primed for it by the scene of Nancy’s arrival, when she browses through photos of her dead mother. Those are delivered to us as paste-ups in the same frame, rather than as optical POV shots of Nancy’s phone. Soon after, still during her ride to the beach, we see an instant message from her friend.

So the pseudo-shot/reverse-shot has been prepared for by these other displays of her screen. We’re ready for this to be an intrinsic norm of this film. Later we’ll get the ticking-clock deadlines through inserts of of her watch.

More generally, the film as a whole tightly restricts us to Nancy’s experience. Nearly everything we see and hear is filtered through her consciousness. (The film’s momentary detours from her range of knowledge work to maximize suspense, in the manner of the bomb under the table.) During the phone conversation, cutting back to her father at home in Galveston would have made him a more important character. As it is, the narration keeps the emphasis on her situation and the beautiful but menacing landscape, the “perfect beach” that she needs to conquer as her mother did.

Shot/reverse-shot is a schema for handling stylistic options. I suggest that there are narrative schemas too, tried-and-true storytelling patterns that filmmakers can repeat, reject, or revise. Novelty builds on familiarity. As Damien Chazelle describes La La Land: “I’m trying to hark back to certain old traditions but hopefully show you something you haven’t seen before.”

For the viewer, schemas supply a certain predictability. We’re used to the back-and-forth of shot/reverse-shot cutting. Likewise, we expect a flashback to supply background information that clarifies the situation in the present. In the American studio tradition, a filmmaker who revises a schema needs to give us enough of the pattern to make us realize the alterations. The Shallows‘ revision of shot/reverse-shot is clear to us because, given our knowledge of FaceTime/Skype technology, we can grasp the images as diagrammatic presentations of a familiar editing pattern. Similarly, we can sense a flashback even when it’s quick or cryptic, and we anticipate that things will clarify later. The dynamic of familiarity and novelty will work only if the the new twist plays off something recognizable.

Back in September, I noted that almost every film I was seeing seemed indebted to 1940s storytelling, but I talked only about Sully. Today I go wider and look at several 2016 films, both pop and prestigious, that rely on methods of roundabout storytelling that coalesced back then. We’re so used to these methods that we tend to forget their debts. By analyzing how our writers and directors draw on this tradition, we better understand their roots in film history–and their genuine contributions to changing it.

In her, and his, shoes

One of the most taken-for-granted narrative strategies is that of subjectivity. Here filmmakers use images and sounds to reveal a character’s mind and senses. The main schemas have become very familiar.

Today we scarcely notice optical POV shots or fantasy imagery. They were common in silent film, became less common in Hollywood in the 1930s, and grew very common in the 1940s. The sustained optical POV of Lady in the Lake (1947) is one instance, and so are the protracted dream and delirium sequences in psychological films like Spellbound (1945) and The Lost Weekend (1945).

Go back to The Shallows and you’ll find plenty of POV shots. When Nancy regains consciousness after the climax, we get a mixture of optical viewpoint and imaginary shots, when she first sees Carlos and then “sees” her mother’s approval of her courage.

Dreams are another common device for rendering subjectivity. They became commonplace in the psychoanalytical films of the 1940s, and have been used ever since to probe the more or less unconscious impulses of our characters. We’re let in on characters’ dreams in A Quiet Passion, Hacksaw Ridge, and Kubo and the Two Strings.

Both visions and dreams become important motifs in The Birth of a Nation. Early in the film, the child Nat Turner, who has been called “a leader and a prophet” by an elder slave, dreams of himself in tribal paint running through a forest. Later, grown-up and developing a sense of himself as a rebel against oppression, he re-experiences the dream, only now the child encounters himself as an adult, who moves to protect him. The child becomes father to the man.

These plunges into subjectivity run along with images of Nat’s revelation: an angel he sees at moments of greatest torment, on the whipping block and on the gallows.

On the second occasion, the figure is more fully revealed as an angel, and she seems ready to embrace him. The nocturnal spirituality of the opening has been counterbalanced by something like Christianity, but it’s hardly the white folks’ version: Nat sees a dark angel.

Frames and breaking frames

Moana.

Subjectivity can also shape our sense of time, thanks to flashbacks. Very common nowadays is the brief flashback representing a sudden memory. In Allied, a shot of Max and Marianne on their rooftop bed-sit in Casablanca comes when Max is recalling their mission, after he’s learned she might be a German spy. A parallel device is the auditory flashback, as when a character recalls earlier lines of dialogue, which might not be accompanied by imagery from the past scene. Several of these films drop in sonic flashbacks, which serve as reminders to the audience as well as recollections for the characters.

A subjective push into the past can take over the whole structure of the film. This happens when big stretches of the plot are presented through flashbacks to events that characters tell or remember. A fairly pure case is Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. It intercuts three time periods: the present, as Billy and his comrades in arms visit a Thanksgiving football game; Billy’s return to his family two days before the game; and the more distant events of Billy’s tour of duty in Iraq, culminating in the death of his beloved sergeant Shroom.

Throughout the film we’re largely restricted to what Billy experienced in both present and past.

In most films, though, flashbacks don’t represent memories. Often a flashback is initiated as a character’s recollection or testimony, but it presents events that a character didn’t know about. In these cases, the film has it both ways–subjective when it wants us to feel with the character, but wider-ranging when the extra information can yield suspense or another perspective on what the character knows. This happens in Jackie, in which Jacqueline Kennedy tells a journalist about the JFK assassination and its aftermath. We mostly adhere to what she could have seen and heard, but some incidents occur outside her ken. The interview situation motivates the return to the past, and that’s usually what we find in these partly subjective flashbacks.

The flashback technique was fairly common in Hollywood’s silent era but rarer in the 1930s. It emerged as a major creative option in the Forties; there are more flashbacks in 1944 feature releases than in all of the Thirties. Nowadays most films, even Moana, resort to it. (Maui’s boasting song “You’re Welcome” reviews his gifts to humanity.) Virtually every film I mention today employs at least one flashback–a testimony to the enduring power of this storytelling norm.

Since even the most personal flashbacks tend to stray from what characters could have witnessed, it’s not surprising that today we commonly have completely “objective” flashbacks. The plot simply jumps to and fro through time without the alibi of character memory. Hollywood has occasional early instances (Beau Geste, 1927; A Man to Remember, 1938; Confidence Girl, 1952; The Killers, 1955), but the “external” flashback is rare before the 1960s. Over the decades, filmmakers and audiences became comfortable with the flashback that simply admits itself as such. The time shift may be signaled by a title (“Two Days Earlier” in Billy Lynn), but some films find other ways to announce the flashback.

A simple example is Ben-Hur. Steered by a voice-over narrator (who will turn out to be a character in the film), the opening shows the start of a chariot race in a Roman Circus. Two young bravos swap lines that arouse curiosity: “You should have stayed away.” “You should’ve killed me.” “I will.” Then the race starts, the camera pans left to follow it, and the shot dissolves (a graphic match) to an image of two horsemen racing around a rock.

They are youthful versions of the competitors we’ve just met, and we’ll learn that Messala is Judah Ben-Hur’s adopted brother. The rest of the plot follows the friends’ careers that lead them to the fateful chariot competition. And that opening stretch is replayed when the flashback catches up with the frame situation. We’re reintroduced to the Circus, and identical shots show them exchanging the same lines we heard at the start.

This sort of overlapping return to the frame is common when the flashback consumes a large chunk of the film. One traditional schema, used in Ben-Hur, presents the frame story as a situation in crisis. This serves to grab our attention, to raise questions, and to hold the outcome of present-time events in suspension while the backstory clicks in.

The crisis structure is seen in Hacksaw Ridge, when after glimpses of a ferocious battle we see the protagonist rushed along on a stretcher. Thanks to a title, “Seven Years Earlier,” we shift to the past in another “objective” flashback. Eventually we’ll loop back to the wounding and rescue of Doss at Hacksaw Ridge.

The earlier versions of Ben-Hur didn’t resort to flashback construction. Similarly, Sergeant York (1941), which has similarities to Hacksaw Ridge, relies on straightforward chronology. The crisis schema became popular in the 1940s (e.g., The Big Clock, 1947), but it’s even more common now than it was then.

So is a willingness to put flashbacks inside flashbacks. Hacksaw Ridge‘s main flashback breaks its own chronology to show scenes of domestic violence in Doss’s youth. The main flashback of Ben-Hur plays host to embedded flashbacks too. The large-scale Chinese-box construction of 1940s films like The Locket (1946) and Passage to Marseille (1944) is still uncommon, but brief flashbacks wedged inside a long-term one pose no problems for current audiences.

Ben-Hur and Hacksaw Ridge set up the Now situation straightforwardly and at some length. At the opposite extreme is the present-time opening of Don’t Breathe: a slow swoop down to a barren street along which a man drags a young woman’s body. A second shot isn’t very informative about him or her, and the two shots consume only 63 seconds.

Probably most viewers forget about this cryptic but intriguing crisis situation until it’s repeated at the climax–the shots in reverse order, the woman more clearly visible, and the two shots clipped to a mere nine seconds. This is compact storytelling.

The Shallows sets up its Now through attachment to a minor character. A little boy finds a video camera on a helmet floating in the surf. He plays the footage and, seeing a shark attack recorded there, runs to get help.

Later the boy’s discovery is shown again, and now we’re in a position to appreciate its importance. But like the opening sequence of Mildred Pierce, this prologue has omitted key information: the boy’s replay of Nancy’s recorded plea for help. At the climax that footage, which we’ve seen her make, is is now re-run for us as the boy watches it. Again the boy is shown running for help. This overlap brings us up to the original Now.

At the start there was an enigmatic rack-focus to the buoy in the distance. In the replay, while the boy studies the video, we see Nancy bobbing there, waiting for the shark to attack.

This scene, incidentally, shows how a flashback structure can take the sting out of a convenient coincidence. If something unlikely–the boy discovering the camera in time to help the heroine–is shown before the main action, then it doesn’t seem as out-of-nowhere as it would if presented in straight chronology. After seeing the somewhat cryptic opening, we might even be looking forward to the revelation, as presumably some viewers are when a scene in the flashback introduces the surfer with the camera helmet.

Interestingly, neither Don’t Breathe nor The Shallows resorts to a title announcing the transition from Now to the past. Can it be that our genre pictures can live with a little less redundancy than our Oscar bait?

Strands, mosaics

Jackie.

Filmmakers never tire of tweaking flashback conventions. A more subdued variant of the crisis setup is used in Manchester by the Sea. Joe Chandler dies and his brother Lee, working as a maintenance man in Boston, is summoned back home to Manchester. These scenes alternate with episodes from the past, out of order, showing the brothers’ relationship and Joe’s eventual death. The crisis comes about fifty minutes into the plot, when in a lawyer’s office Lee learns that Joe wanted him to take custody of his son Patrick and move back to Manchester.

Lee’s resistance to this plan is explained in another string of flashbacks that show the disintegration of Lee’s marriage, the death of his children, and his attempted suicide. He has left the town behind and lives in self-inflicted pain and isolation.

At this point, the film reverts to chronology in the Now. The drama pivots around Lee forging a relationship with Patrick and coming to terms with his past. Only two brief flashbacks break up the story line, and those relate to Joe’s disappointment at Lee’s retreat from the world into a menial job. If the first half had been presented chronologically, we would have lost the sharp contrast between Lee’s scowling reluctance to reach out to Patrick and the more vigorous, emotionally open man he once was. Hollywood films may not excel at portraying gradual character change, but flashbacks allow a sharp sense of Before and After that can suggest how humans remake themselves in response to events.

The mosaic quality of the flashbacks dotting Manchester by the Sea can be seen to a lesser extent in Jackie. Here there are four principal strands of time to be interwoven, with glimpses of others. One strand involves the Kennedy assassination and its aftermath–the public ceremony of the display of his body and his burial in Arlington. Another involves Jackie’s consultation with a priest some time after JFK’s death, discussing her plans to bury their first two children, who died as babies, alongside him. A third strand, temporally pre-assassination, presents her famous 1962 tour of the White House. Finally there’s her post-assassination interview with a reporter who asks her questions about her role as First Lady and her handling of the horrific Dallas tragedy. We also get glimpses of the 1960 inauguration ball and Pablo Casals’ 1961 concert at the White House.

The film opens with the reporter calling on Jackie and the two settling down for their talk. He’s a bit provocative and probing, she’s guarded and self-censoring. The somewhat odd angle of the shot/reverse-shot framings, with her eyeline only a little off-center and sometimes straight at the camera, conveys an eerie ceremonial stiffness.

The reporter’s interview seems to be the frame for the flashbacks. Not only does their meeting occupy the normal position of a framing situation, but we’re aware that another schema triggering flashbacks is a testimony situation. In court, in a police station, at home quizzed by a reporter: These often set up a flashback narrative. The probing-reporter schema was crystallized in the 1940s with, of course, Citizen Kane (1941) but also with earlier films like The Escape (1939), Edison the Man (1940), and The Great Man’s Lady (1941).

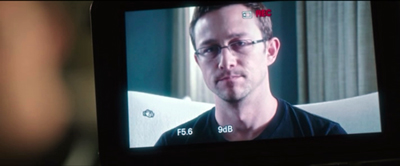

Snowden is a good contemporary example of the reporter-interview frame. Long blocks of flashbacks are enclosed within a ticking-clock situation in the present. Snowden retells his life, in chronological order, for Laura Poitras and Glenn Greenwald.

The film’s narration is largely tied to his range of knowledge during those periods, especially when suspense is at stake. We get plunges into subjectivity when he’s struck by epilepsy, and much optical POV cutting, notably when he downloads the NSA files as officials mill around outside his cubicle. As often happens in classical filmmaking, the narration widens its perspective to provide montages of news reports and reactions to Snowden’s revelations by his associates around the world.

Snowden tidily frames its past episodes by the present-time action before and after the big interview. The final scenes, and the credits, show the consequences of his whistle-blowing in the days and years afterward. But Jackie revises the testimony schema in an unusual way.

As the film goes on, it’s revealed that the reporter’s interview with Jackie isn’t the ultimate Now. The last events in the story chronology are Jackie’s consultation with the priest and the burial of her children. But from about 45 minutes onward, the priest’s attempts to console her are intercut with the interview. They are, in other words, flash-forwards.

They’re initially concealed as such because they follow Bobby Kennedy’s suggestion, in the assassination’s aftermath, that Jackie talk to a priest. That cue inclines us to assume that the priest’s advice is given during her final days in the White House. Only when the reporter phones his editor and says Jackie intends to bury the children beside Jack, and when Jackie tells the priest that the reporter’s story went around the world, are we aware of the burial scene’s place at the very end of story chronology.

This is a cogent example of schema revision: a frame that doesn’t enclose everything that, by convention, it should. One effect is to make the burial of the children an unexpected climax–a revelation of how much death this woman has seen, and a counterpoint to the glittering image of “Camelot” on which the film closes.

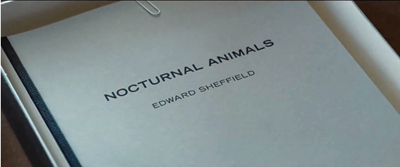

So where you put your flashbacks turns out to be crucial. Had the flashbacks to Lee’s tragic mistakes in Manchester come earlier, we’d probably be less sympathetic to him than we are; by the time of their arrival, we’ve seen his long-term suffering and are prepared to have a complex judgment of him. The timing of flashbacks also shows to good effect in Nocturnal Animals.

Most of Nocturnal Animals is dominated by another device for braking chronology: the embedded story. Here a plot involving new characters is wedged within the main story. Novels have done this for some time, as when a character discovers a manuscript that opens a story world containing a completely new cast. In the comic book Watchmen, the story Marooned is read by a minor character in the main plot.

In films of any period, such discrete embedded tales are rare. In the 1940s, the chief variant involves dream plots: the protagonist falls asleep and the dream consumes the bulk of the film, as a long flashback might. The main character might retain her identity, as Dorothy does in The Wizard of Oz (1939), or the dream character might be a new persona, as in Du Barry Was a Lady (1943), where Red Skelton becomes King Louis XV. Either way, an alien story world is opened up.

Nocturnal Animals contains an elaborate embedded story. Art-gallery owner Susan Morrow is in the dumps; her chi-chi friends are cold and her husband is having an affair. She receives the manuscript of a novel from her first husband Edward. Over some days Susan reads this harrowing pulp exercise set in west Texas, and it’s dramatized for us in chunks. interspersed with her daily routines.

At first we might think that the novelistic sections are “objective” presentations of the scenes, a parallel fictional world. But about 45 minutes into the film, we get a flashback to Susan meeting Edward at the start of their romance. (Actually, it’s a re-meeting; they had crushes on each other years before.) Thereafter flashbacks to their courtship and their marriage are interspersed with more stretches of the novel. Tony, the hapless, somewhat spineless protagonist of the novel, is played by Jake Gyllenhaal, who also plays Edward.

The flashbacks invite us to find a dose of subjectivity here. Is Susan reading the novel as a portrayal, deliberate or unwitting, of Edward’s feelings of inadequacy in their marriage? She cheated on Edward with the man who became her second husband, so she may also be projecting her own guilt onto the terrifying fate of Tony’s wife–interestingly, not played by Amy Adams, the actress portraying Susan.

In Nocturnal Animals, the frame is neater than in Jackie; at the film’s end we return to Susan’s present life. But an ambiguous ending asks us to consider how fully we have entered into her imagination.

There’s a more drastic revision of the flashback schema, or rather the audience’s presuppositions about it, in Arrival, which I’ve talked about here. But interesting flashbacks with a 40s flavor are also at work in James Schamus’s Indignation, analyzed here.

Strands or blocks?

I think these examples show that it can be useful to think about film narrative from the standpoint of craft. Since the filmmakers made choices, what rationale justifies them choosing what we have rather than what we might have had?

For example, it would have been perfectly possible to arrange the time-layers of Jackie or Manchester by the Sea as blocks, separate chapters (perhaps given titles or dates) rather than as interwoven strands. Similarly, Nocturnal Animals could have shown us Susan’s marriage to Edward as one block, then her life with her second husband, and then the embedded novel as one long stretch. Thinking about how these alternatives would alter our experience can give us insight into the benefits and costs of the choices the filmmakers went with.

Block construction became a somewhat popular storytelling option in the 1940s. Long flashbacks balanced against one another can create blocks, as in Citizen Kane and A Letter to Three Wives (1948). Similar were “chaptered” films like Holiday Inn (1942) and Meet Me in St. Louis (1944) and the episode-based films Fantasia (1942), Tales of Manhattan (1942), Flesh and Fantasy (1943), and others. Welles, always alert to trends, planned such a structure for It’s All True.

2016 has given us two pure examples of block construction, both of considerable interest. The most visible one is Moonlight, which tells its character-centered story in three phases of the life of Chiron: his boyhood, his teenaged years, and his early adulthood.

The sections are announced by titles: Little, Chiron, and Black. The first two stretch over several weeks and show Chiron bullied by other kids and neglected by his crack-addicted mother. He also encounters helpers, at first the easygoing drug dealer Juan and his girlfriend, and later his schoolmate Kevin, who in the second episode is forced by the other boys to beat Chiron. The final episode unfolds in a single night. Chiron, now called Black and grown to be a powerful man, has become a drug dealer and is filmed somewhat parallel to Juan.

Black visits a diner where Kevin works. Tentatively their affection and sexual yearning for one another are rekindled.

As with any creative choice, there are trade-offs. Moonlight‘s sharply-edged episodes refuse a smooth arc of action; they sample his life and deny us a clear “coming of age” process. There are gaps between the stories, and the one between the second and the third episodes is crucial. We’re left to imagine what happened to Chiron that turned him into the muscled, tough Black. Perhaps the fight that got him sent out of school–the moment when he fought back at the main bully–marks his turning point. Surely too his prison experiences shaped his transformation, but we neither see those nor hear him tell about them. Director-screenwriter Barry Jenkins has left us to note the vivid change in character without supplying what Henry James called the “weak specification” of all the events that shaped him. Block construction has left empty spaces for our imagination to fill.

Another fairly pure case of block construction is Paterson. (I discuss it briefly here.) The plot consists of a week’s worth of events, broken into days starting on Monday. We follow Paterson the bus driver on his daily rounds of going to work, doing his driving, coming home to his wife, walking their dog, and sometimes paying a night visit to a local tavern. Some incidents are variants of others, such as the morning conversations with Donny, Paterson’s supervisor, or the glimpses of different sets of twins around town.

The daily blocks are marked, at least initially, by a title stating the day of the week, but this pattern is varied: No titles for the weekend. Another marker is the opening shot of each segment showing Paterson and his wife in bed from straight above them.

This image varies too, with different compositions and shot scales each morning, and in one case, Paterson alone. Cinematographer Frederick Elmes explains that each day changes:

So there’s a routine. He’s going to leave and return to the house at the same time every day, so it’s going to look the same. I said to Jim [Jarmusch, the director], “It might be nice to have some gentle differences between them, to define one day from the next.” That became our task, finding ways of keeping things visually interesting without going too far.

Today block construction often calls forth the sort of stylistic tagging pointed out by Elmes. The same differentiation of visual textures is found in flashbacks. A funny example occurs in Sausage Party, when Firewater explains how the Non-Perishables created the myth of humans as kindly gods. The framing situation in the present is given in chiaroscuro imagery with thick volumes and plausible (for a cartoon) depth. The flashback to humans’ slaughter of the groceries is rendered in a screeching, retro/headcomix style and an abstract space.

This style is maintained for the fantasy version that Firewater and his cronies concocted to keep the groceries from panicking. Then we return to the narrating frame.

Not gentle differences here: glaring ones, suitable to comic exaggeration.

Something in-between operates in several of the films I’m considering. In Café Society, two cinematographic styles differentiate between the major locales, Hollywood and New York. Jackie‘s post-asssassination flashbacks are filmed in a free-camera style distinctly different from the locked-down, planimetric shots of the interview and the more studio-bound images of the TV filming of the White House Tour.

Likewise, Nocturnal Animals assigns three different “looks” to its three levels. DP Seamus McGarvey explains that Susan’s present had to be “colorless, [with a] low-contrast anemic aspect to it.” The story within the story is “colorful, more primaries.” The flashbacks to Susan’s and Edward’s marriage have a softer, glowing texture.

Visually tagging blocks, fantasies, and flashbacks wasn’t uncommon in the silent era, when filmmakers marked them with vignettes and soft focus. These optical devices, along with distorting lenses, were occasionally used in the sound era too, along with occasional shifts between color and black-and-white (The Wizard of Oz; Portrait of Jennie, 1949). On the whole, differentiating strands or blocks became a firm craft convention somewhat later, from the 1980s on. I talk about how that happened in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

Ooh-La-La Land

Believe it or not, I haven’t exhausted the debts of 2016 movies to Hollywood in the Forties. There is, for instance, the device of voice-over, so common in that decade, which reappears in various guises, most notably that of the gossipy narrator of Café Society. There’s also the strategy of confining the bulk of the film’s action to a single location, which became notable in Angels over Broadway (1940), Lifeboat (1944), Rope (1948), and The Time of Your Life (1948). That method, common to low-budget thrillers, was ingeniously exercised in 10 Cloverfield Lane, The Shallows, and Don’t Breathe. In another entry I’ve discussed how Sully uses the device of replay that became common in the 1940s.

La La Land sums up several of the tendencies I’ve mentioned. It displays block construction, with sections labeled Winter, Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter… Five Years Later. The film’s first section uses the flashback technique too. After we follow Mia out of the traffic jam and to the party and the piano bar, the narration jumps back to the traffic jam and tracks Sebastian through his day up to the moment he pounds out jazz at the piano. This brings them together. As she’s about to compliment him on his playing, he brushes past her and leaves. At about 25 minutes in, this is the turning point ending the film’s first part.

The rest of the film traces their other coincidental meetings until they fall in love, try to maintain their relationship, and ultimately break up. They re-meet at Sebastian’s club, with Mia now married to a courteous side of beef. As the two look at each other and Sebastian takes over the piano to play their love theme, the film skips back to the first piano-bar encounter. Instead of passing Mia, though, Sebastian grabs her and they kiss.

Now the narration posits an alternative story line in which they marry, become parents, and still have success. This what-if scenario is rendered in stylized settings, accompanied by moments of dance.

Like the visual tagging of blocks and flashbacks, this sequence needs to abstract its settings, theatricalizing them so they’re set off from the real-world locales in which our characters have also been singing and dancing.

La La Land revisits a schema that was explored a little in 1930s and 1940s Hollywood: the alternative-universe story line created by forking paths. I’ve talked about the clearest early example, the 1934 film adaptation of the play Dangerous Corner. It’s a Wonderful Life (1947) did it negatively: Imagine a universe without you (or George Bailey). A little-known instance from that period is Repeat Performance (1947), which offers its actress-heroine a narrative reset like that to come in Groundhog Day (1993), Run Lola Run (1998), Source Code (2011, talked about here), Edge of Tomorrow (2014), and many other media texts, including comics.

Again,the schema is creatively reworked. The past the couple might have had is played out with parallels to the real-world life that Mia found. The result is an epilogue balancing the traffic-jam prologue–these people, unlike the gridlocked drivers, have found their success in Show Biz–but at the cost of love. By showing us what might have been, the final sequence provides something both wistful and satisfying.

I regret missing certain films this year, particularly Kelly Reichardt’s Certain Women, which seems to constitute an intriguing instance of block construction merged with a minimal network narrative. I look forward to catching up with it. And I’ve confined myself to Hollywood and off-Hollywood films, but I could easily have stretched the boundaries to include Elle (flashbacks), I Am Not Madame Bovary (block construction), Sieranevada (confined-space shooting, discussed by Kristin), Julieta (flashbacks, voice-over, etc.. etc., discussed in another entry), and many other imported films. These narrative strategies now belong to contemporary movie storytelling as a whole.

I don’t want to leave the impression that as I’m watching new release a little homunculus historian in my skull is busily plotting schema and revision, norm and variation. I get as soaked up in a movie as anybody, I think. But at moments during the screening, I do try to notice the film’s narrative strategies. Later, when I’m thinking about the movie and going over my notes (yes, I take notes), affinities strike me. By studying film history, most recently Hollywood in the 40s, I try to see continuities and changes in storytelling strategies. These make me appreciate how our filmmakers creatively rework conventions that have rich, surprising histories.

Thinking along these lines has made my 2016 moviegoing all the more fun. And a happy 2017 to you too.

E. H. Gombrich explains the concept of the schema throughout Art and Illusion, particularly in Chapter V and on pp. 313-314.

My quotation from Damien Chazelle comes from Mark Dillon, “City of Stars,” American Cinematographer 98, 1 (January 2017), 57. The same issue’s story “Quotidian Vision,” by Iain Marks, includes the remark from Frederick Elmes (p. 22). Seamus Garvey’s comments on the visual styles of Nocturnal Animals comes from Carolyn Giardina, “Beginning First in the Darkness, Then Moving toward the Light,” Hollywood Reporter, Awards no. 1 (December 2016), 48; apparently not available online. In the same article Vittorio Storaro talks about differentiating New York and Hollywood pictorially in Café Society.

The cellphone conversation in The Shallows is an interesting turn back to a much older schema for representing phone conversations, using split screen. The first one below is is from College Chums (1907). We’ve seen similar phone-call diagrams since then in Pillow Talk (1959), Bye Bye Birdie (1963), and Down with Love (2003, also below). Everything comes back eventually.

Other discussions of stylistic schemas hereabouts are in entries on lipdubs, shot/reverse-shot cutting, and Wes Anderson’s narrative worlds.

There’s another flashforward in these films: La La Land embeds a montage of the couple’s creative work in their “City of Stars” duet at the piano. Another, smallish block, it anticipates the looped construction of the final fantasy epilogue.

Snowden: Yet another revision of the shot-reverse shot schema, adapted for what John Dean called “telephonic communication.”

Spies face the music: Jeff Smith on FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT

DB here: Here’s another guest contribution from colleague, Film Art collaborator, and pal Jeff Smith. He inaugurates a series of entries tied to our monthly Observations on Film Art videos on FilmStruck.

About a month ago, a new streaming service for film lovers debuted. Its name is FilmStruck and it’s a joint venture of Turner Classic Movies and the Criterion Collection.

As regular readers of the blog already know, David, Kristin, and I have launched a series for FilmStruck. Every month, we’ll be featured in short videos that offer appreciations of particular films and filmmakers. In baseball lingo, I got the leadoff spot. As the first up, I offered an overview of the principal musical motifs in Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent. Below is a supplement to the video that goes into a little more depth regarding the way Alfred Newman’s score for Foreign Correspondent fits into the film’s larger narrative strategies.

Fair warning: there are some spoilers in what follows. Some of you who are FilmStruck subscribers or owners of the Criterion disc may want to watch this Hitchcock classic before proceeding.

Founding a Hollywood dynasty

Alfred Newman.

If you were looking for someone whose work epitomized the qualities of the classical Hollywood score, Alfred Newman would be a pretty good candidate for the job.

Newman’s career in Hollywood began when Tin Pan Alley stalwart, Irving Berlin, recommended him for the 1930 musical, Reaching for the Moon. Having worked for years as a music director on Broadway, Newman planned to stay for only three months. But the lure of the Silver Screen was too strong. Newman spent the next forty years working in Hollywood.

In 1931, Newman became the musical director at United Artists, working mostly for producer Samuel Goldwyn. He also established himself as one of the industry’s leading composers, contributing to nearly ninety films over the course of the 1930s and earning nine Oscar nominations in the process. Newman’s most memorable early scores included such titles as The Prisoner of Zenda, The Hurricane, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Wuthering Heights. Eventually, he would leave Goldwyn to take over the music department at 20th Century-Fox, a position he held for more than twenty years.

Alfred, however, would be just one of several Newmans who would make the name synonymous with the Hollywood sound. Alfred would establish a film composing dynasty that would come to include his brothers Lionel and Emil; his sons, Thomas and David; and his nephew, Randy.

Overture, hit the lights….

If you asked most film music aficionados for their favorite Alfred Newman scores, I suspect Foreign Correspondent would be pretty low on the list. Most fans of the composer’s work would likely opt for one of the later Fox classics he scored, such as How Green Was My Valley (1941), A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), The Captain from Castile (1947), or The Robe (1953). Yet, if you want to get a handle on the basic features of the classical paradigm, Foreign Correspondent’s typicality makes it more useful as an exemplar. Newman’s music neatly illustrates several of the traits commonly associated with the classical Hollywood score’s dramatic functions.

One of these characteristic traits is Newman’s use of leitmotif as an organizational principle. Foreign Correspondent’s score is organized around five in all. The first is a theme for the film’s protagonist, Johnny Jones. The second is a theme for Carol, Johnny’s love interest in the film. As is typical of studio-era scores, both themes are introduced in the film’s Main Title.

Like an overture, the Main Title previews the two most important musical themes in the film. The A theme is upbeat, sprightly, and lightly comic. It captures some of Johnny’s ebullience and masculine charm, and it helps establish the tone of the early scenes, which draw upon the conventions of the newspaper film. The B theme is slower and more lyrical. It features the kind of lush orchestrations for strings that became a hallmark of Newman’s style.

Each theme roughly correlates with the dual plot structure common to classical Hollywood narratives. The A theme previews the main plotline focused on Johnny’s efforts as an investigative reporter. The B theme previews the story’s secondary plotline: the budding romance between Johnny and Carol.

Both themes recur throughout the remainder of the movie. In fact, Johnny’s theme returns even before the opening credits have ended, appearing underneath a title card valorizing the power of the press. In contrast to the lively, spunky version heard earlier, Newman gives it a maestoso treatment, slowing the tempo and orchestrating it for brass. In this instance, Newman’s arrangement of Johnny’s theme is attuned less to the brashness of his character and more to the social role that newspaper reporters play as a source of information to the world.

Up until this point, the music simply primes us for what is to come. Johnny’s theme returns about two minutes later when he is first introduced.

The reprise of his theme makes explicit the Main Title’s tacit association between music and character. Here, though, it plays in a jazz arrangement as a slow foxtrot. Newman’s arrangement nicely captures the tone of these early scenes, which display the lightness and pacing of other newspaper comedies.

It returns 22 more times in the film. In all, Johnny’s theme accounts for more than a quarter of the film’s 94 music cues. Usually, the theme functions to underline Johnny’s heroism and resourcefulness as in the scene where he gives chase to Van Meer’s assassin. At one point, Johnny even whistles his theme. This occurs in the scene where he eludes a pair of suspicious men posing as police by pretending to draw a bath and crawling out the window.

In contrast, Carol’s theme is used less frequently, appearing in about thirteen cues in all. After its introduction in the main title, it returns when Johnny and Carol first meet at the luncheon sponsored by the Universal Peace Party. Johnny unknowingly insults Carol, first by mistaking her for a publicist, and then by expressing skepticism about the organization’s mission, griping about well-meaning amateurs interfering in international affairs. Newman’s theme hints at Carol’s attraction to Johnny despite his obvious boorishness. The music says what the characters can’t or won’t say. As Johnny and Carol trade insults, Carol’s theme captures the romantic spark that lurks beneath their badinage.

The theme’s other uses often work along similar lines, providing an emotional resonance to the couple’s expression of feelings for one another. A good example is found in the scene where Carol and Johnny huddle together on the deck of a steamship. Here, as a pair of refugees, each member of the couple declare their love for one another and their desire to marry.

Music for the hope of the world

In addition to these two principal themes, the score also utilizes three other themes and motifs to represent important secondary characters. A theme for Professor Van Meer is introduced when Johnny spots him getting into a taxicab.

It returns nine more times in the film in scenes that feature the character or make reference to him.

The theme itself is simple, slow, stately, and quite frankly, a little bit boring. Indeed, if it wasn’t for the multiple references to a “Van Meer Theme” on the cue sheet for Foreign Correspondent, the music would simply blend into the other material that surrounds it.

The orchestration of the theme for solo wind instruments, usually an oboe, gives it a kind of pastoral feeling. The image of peaceful shepherds is likely an appropriate one for Van Meer, who functions as a stand-in for a global desire to avoid armed conflict. Yet, both the character and Newman’s musical theme for him seem nondescript, making Van Meer seem like little more than the walking embodiment of an abstract ideal of world harmony.

Truth be told, Van Meer mostly operates in Foreign Correspondent as the classic Hitchcock MacGuffin–that is, the thing the characters all want, but with which the audience need not concern itself. When Van Meer appears to be assassinated, it sets in motion a chain of events that uncovers a conspiracy organized through Steven Fisher’s World Peace Party. Van Meer is the object that all the characters want to find, and the search for him drives the narrative forward. Yet the character himself has about as much personality as the microfilm in North by Northwest. Newman’s nondescript melody seems to fit the “blank slate” quality of Van Meer himself.

Like the classic MacGuffin, Van Meer’s function as something of an empty vessel allows his theme to be used several times late in the film in scenes where the character isn’t physically present. Although the norm is to use characters’ themes or leitmotifs when they are onscreen, Newman’s treatment of Van Meer shows they can evoke absent characters. This occurs, for example, in a scene where Scott ffolliot explains to Stephen Fisher that he’s arranged for the kidnapping of Carol. Fisher asks ffolliot why he would do such a thing, and ffolliot replies that he wants to know where Stephen has stashed Van Meer.

As we’ll see, Fisher has a theme of his own that itself appears several times in this same scene. But the use of Van Meer’s theme in this context becomes a way of signifying both the character and the peaceful values that he represents – that is, values that Fisher seeks to destroy.

And though Van Meer’s music is a bit dull, the theme proves a bit more interesting when one considers the way it works within Hitchcock’s larger strategies of narration. At a key point, Hitchcock and Newman use the Van Meer theme to mislead the audience about what has just transpired onscreen. I’m referring here to the moment when Van Meer appears on the steps just as the Peace conference in Amsterdam is about to commence.

The theme is cued by Johnny’s glance offscreen after briefly chatting with Fisher, his publicist, and a diplomat. Hitchcock cuts to a shot from Johnny’s optical POV that shows Van Meer climbing up the staircase. We return to Johnny, who smiles and walks out of the frame. Johnny and Van Meer meet in a two-shot where the former offers a warm greeting. A cut to Van Meer’s reaction, though, reveals a blank stare, even as Johnny tries to remind the elderly professor of their previous encounter in the taxi.

The moment is an important one, but before the viewer can even grasp its significance, the two men are interrupted by a request for a photograph. Hitchcock then tracks in on the newsman, who surreptitiously sneaks a gun next to the camera he is holding. He pulls the trigger, and Hitchcock cuts to a brief insert of Van Meer, who has been shot in the face.

As I noted earlier, the assassination we witness is a key turning point in the story, and Hitchcock handles the scene with considerable finesse. Almost unnoticed, though, is the fact that Hitchcock and Newman cleverly use Van Meer’s musical theme as a form of narrative deceit. At first blush, the musical theme helps to reinforce Van Meer’s identity, serving the kind of signposting function that some film music critics believed was a hackneyed device. As we later learn, though, the murder victim is not Van Meer, but rather a double killed in his place to foment international tensions. This information ultimately recasts the old man’s seeming failure to recognize Johnny. As Van Meer’s double, these two men have never actually met.

Has Hitchcock played fair in using Van Meer’s theme for a character that is not Van Meer but only looks like him? Perhaps, but the creation of this red herring is justified if one considers the fact that composers frequently write cues meant to reflect or convey a character’s point of view. Every composer must make a choice about whether to write a cue from the particular perspective of the character or the more global perspective of the film’s narration. Newman might have opted for conventional musical devices that connote suspense (ostinato figures, string tremolos, low sustained minor chords), and these would have signaled to the viewer that Van Meer is in peril, thereby creating a heightened anticipation of the violence that erupts in the scene. Instead, though, following the visual cues provided by Hitchcock’s cinematography and editing of the scene, Newman plays Johnny’s perspective and his recognition of Van Meer as he approaches the building’s entrance. By combining two common tactics–leitmotif and character perspective – Newman and Hitchcock briefly mislead the audience in order to create two surprises: the first when it appears that Van Meer is killed and the second when Van Meer is discovered inside the windmill and proves to be very much alive.

Menace (without the Dennis)

There is also a brief six-note motif used to signify the conspirators as a group. Labeled the “menace” motif, it is introduced just after Van Meer’s apparent assassination. In the chase that follows, Newman alternates between the “menace” motif and Johnny’s theme in order to sharpen the conflict and to capture the ebbs and flows of our hero’s dogged pursuit of the bad guys.

The motif returns, though, at just about any point where one of the group’s henchmen gets up to no good. In the scene inside the windmill, the menace motif appears several times to underscore the kidnappers’ nefarious scheme. Johnny sneaks inside the windmill, and after locating Van Meer, he tries to rescue him only to find out that the elderly professor has been drugged. As Johnny tries to figure out his next move, muted trumpets play the “menace” motif, signaling the kidnappers’ approach and thereby heightening the scene’s suspenseful tone.

Here again, Newman’s thematic organization reinforces a larger narrative tactic in Hitchcock’s film. Herbert Marshall serves as the typical suave villain commonly found in the Master’s oeuvre and Edmund Gwenn steals the show as Johnny’s would-be assassin, Rowley. But the rest of the conspirators are a largely undistinguished lot, and the use of a single motif for the group in toto reflects their relative impersonality. Unlike North by Northwest, where Martin Landau makes a vivid impression as Van Damm’s reptilian assistant Leonard, this spy ring seems to be filled out by thugs from Central Casting.

Father, leader, traitor, spy

Besides motifs for Johnny, Carol, Van Meer and the conspirators, there is also a short motif for Carol’s father, Stephen Fisher. It is harmonically and melodically ambiguous, structured around the rapid, downward movement of a chromatic figure.

In classical Hollywood practice, a leitmotif is usually introduced when the character first appears onscreen. But in an unusual gesture, Newman and Hitchcock resist this convention. The motif does not appear until more than eighty minutes into the film in the aforementioned scene just before ffolliot tries to blackmail Fisher into divulging Van Meer’s location.

By withholding Fisher’s motif, Hitchcock and Newman avoid tipping their hand too early. Since Fisher is later revealed to be the leader of the spy ring, the score circumspectly avoids comment on him in order to preserve the plot twist.

Several cues featuring Fisher’s motif return in the scene where Johnny, Carol, ffolliot, and the other survivors of the plane crash cling to wreckage waiting to be rescued. Carol spots the plane’s pilot stranded on its tail.

He swims over to the group and clambers about the wing. The pilot’s added weight threatens to upend the wing, thereby endangering everyone sitting atop it.

Recognizing this, the pilot asks the others to let him go so that he can simply “slip away.” Fisher overhears this exchange and decides to remove his life jacket and dive into the waters himself, leaving room on the plane’s wing for the rest of crash’s survivors.

The harmonic and melodic ambiguity of Fisher’s motif is most pronounced here, a moment where the character’s duality is also most clearly revealed. Is this a heroic act of self-sacrifice, an act of atonement for the damage Fisher has done to both his daughter’s reputation and his organization’s peaceful cause? Or has Fisher taken the coward’s way out, committing suicide in order to avoid facing the consequences of his actions?

Newman’s rather opaque musical motif doesn’t seem to take sides on this question, leaving Fisher’s motivation more or less uncertain. But this, too, is in keeping with the basic split between the character’s public and private personae. Introduced earlier as Carol’s father, Fisher appears to be cultured and debonair. Yet, when he seeks to extract information from a reluctant captive, Stephen resorts to the physical torments used by two-bit gangsters to make mugs talk. Like those gangsters in the 1930s, Fisher refuses to be taken alive and is swallowed up in briny sea. Still, his action does help to save other lives, and in this way, Fisher enables Carol to find a small measure of grace in the final memory she will have of him.

Putting earworms inside actual ears

As the principal composer of music for Foreign Correspondent, Newman had a major impact on the film’s ultimate success. Yet Newman was not responsible for the music that has engendered the most attention in critical work on the film. I’m referring here to two source cues written by Fox staff arranger, Gene Rose, that are featured in the scene where Van Meer is psychologically tortured. His captors use sleep deprivation techniques to elicit van Meer’s cooperation, including bright lights and the repeated playing of a jazz record. The two cues received rather cheeky descriptions on the cue sheet for Foreign Correspondent: “More Torture in C” and “Torture in A Flat.”

The use of jazz for these cues is likely a little bit of wicked humor on Hitchcock’s part. Despite its popularity as dance music in the 1930s, some listeners undoubtedly believed that jazz was little more than noise with a swinging rhythm. From a modern perspective, though, the scene eerily anticipates the “enhanced interrogation” techniques that would become notorious at Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib. As The Guardian reported in 2008, US military played Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” at ear-splitting volume for hours on end, both at Guantanamo and at a detention center located on the Iraqi-Syrian border. At the other end of the musical spectrum, one of the other pieces played repeatedly was “I Love You” sung by Barney the purple dinosaur. Presumably the first was selected because of its aggressiveness, the latter because of its insipidness. But the Barney song has the distinction of being characterized by military officials as “futility” music – that is, its use is designed to convince the prisoner of the futility of their resistance.

Although, in 1940, Hitchcock could not have envisioned the use of heavy metal and kidvid music as elements of enhanced interrogation, the scene from Foreign Correspondent is eerily prescient. Viewed today, the scene also carries with it a strong element of political critique insofar as it associates such psychological torture techniques with a bunch of “fifth columnists” who are willing to commit murder and even engineer a plane crash in order to achieve their political ends. Touches like these make Foreign Correspondent seem timely today, more than seventy-five years after its initial release.

Alfred Newman the Elder

After Foreign Correspondent, Alfred Newman would go on to score more than a hundred and thirty feature films, and earn several dozen more Academy Award nominations. His nine Oscar wins remain an achievement unmatched by any other film composer. Newman died in Hollywood in 1970 at the age of 69, just before the release of his last picture, the seminal disaster movie, Airport. His work on Airport received an Oscar nomination for Best Original Score, the 43rd such nomination of his long and distinguished career.

For some film music scholars, Newman’s death marked the end of an era, as his career was more or less contemporaneous with the history of recorded synchronized sound cinema in Hollywood. As fellow composer Fred Steiner wrote in his pioneering dissertation on the development of Newman’s style:

As things are, we can be grateful for the dozen or so acknowledged monuments of this twentieth-century form of musical art— absolute models of their kind— that Newman did bestow on the world of cinema. Fashions in movies and in movie music may come and go, but scores such as The Prisoner of Zenda, Wuthering Heights, The Song of Bernadette, Captain From Castile, and The Robe are musical treasures for all time, and as long as people continue to be drawn to the magic of the silver screen, Alfred Newman*s music will continue to move their emotions, just as he always wished.

Because of its typicality, Foreign Correspondent may well seem like a speed bump on Newman’s road to Hollywood immortality. Yet it remains a useful introduction to the composer himself, who along with Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold, is part of a triumvirate that would come to define the sound of American film music.

For more on music in Alfred Hitchcock’s films, see Jack Sullivan’s encyclopedic Hitchcock’s Music. For more on the production of Foreign Correspondent, see Matthew Bernstein’s Walter Wanger: Hollywood Independent. Readers interested in learning about Alfred Newman’s career should consult Fred Steiner’s 1981 doctoral dissertation, “The Making of an American Film Composer: A Study of Alfred Newman’s Music in the First Decade of the Sound Era,” and Christopher Palmer’s The Composer in Hollywood.

Tony Thomas’s Film Score: The Art & Craft of Movie Music includes Newman’s own account of his work for the Broadway stage before coming to Hollywood. Readers interested in an overview of the classical Hollywood score’s development should consult James Wierzbicki’s excellent Film Music: A History.

Alfred Newman conducts his most famous film theme, Street Scene, in the prologue to How to Marry a Millionaire (1953).