Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

ARRIVAL: When is Now?

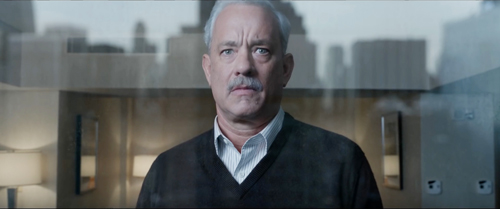

Arrival (2016).

DB here:

A lot of today’s movie storytelling is nonlinear. Filmmakers rely on flashbacks, replays, and voice-overs in order to shape our experience, sometimes in fairly daring ways. In Hollywood these strategies got consolidated in the 1940s. Or so I argue in my Reinventing Hollywood, now in copy-editing (or as the University of Chicago Press calls it, copy editing).

The question today is the same as back then: How do ambitious filmmakers handle these conventions? I think the ambitious writer or director faces at least three tasks.

How do I innovate—that is, how do I treat time shifts in a fresh way?

How do I motivate the shifts—that is, justify the scrambling of chronology?

How do I make the new version clear enough for audiences to follow?

Novelty, motivation, and clarity seem to me essential considerations for a filmmaker who wants to play with time and the viewpoint shifts that often come with it.

I’m not alone in thinking that Arrival succeeds in creating its particular engagement with the audience by tackling my three tasks. Director Denis Villeneuve and screenwriter Eric Heisserer innovate in handling time, and they in turn carefully motivate the device and find ways to make it clear to the audience. Today I want to consider how this all works. I have to assume you’ve seen the film, so of course there are spoilers.

Back to what future?

Cinema didn’t invent broken timelines; they’ve been used in literature for centuries. The Odyssey has blocks of flashbacks. Literature benefits from the fact that language has simple and direct ways to signal jumps in time.

For example, the writer working in English can make flashbacks clear though time tags and verb tense. Take this passage from John Le Carré’s novel Our Kind of Traitor. We’re told that on Sunday morning an anxious Perry Makepiece is climbing into a chauffeur-driven Mercedes. Then:

Last night, returning to the Deux Anges from their supper party, Perry had caught Madame Mère’s boot-button eyes peering at him from her den behind the reception desk.

“Last night” tells us we’re in an earlier period, and that information is reinforced by the past perfect tense of “had caught.” Page layout helps too: the entire flashback to the previous night is blocked out within extra spaces separated by a centered ★.

After recounting what happened when Perry returned to his hotel last night, Le Carré returns to the present time, the narrative Now, with a turn to the simple past tense:

The Mercedes stank of foul tobacco smoke.

Apart from the change of tense, the Mercedes mention reminds us of Perry’s morning trip. In addition, the shift back to the present opens a new section marked by ★.

On my three dimensions: There’s nothing innovative about this instance, though Le Carré will try some unusual things elsewhere in the book. The flashback is motivated by Perry’s remembering last night, and it’s made clear to the reader through repetition of several cues.

But what do we do with this passage?

I remember the scenario of your origin you’ll suggest when you’re twelve.

The tenses are out of whack, thanks to that “you’ll.” Then there’s the very meaning of the word “remember.” (Replacing the phrase with “I imagine.”) How can you remember something that has yet to happen? This isn’t just a casual slip. The speaker goes on to report an entire conversation that uses the future tense: “you’ll say bitterly,” “I’ll say,” “That will be in the house on Belmont Street,” and so on.

This passage comes near the start of Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life,” the source of Arrival. The story is what literary scholars call an apostrophe, a discourse addressed to an absent person. Louise Banks explains how her daughter came into existence. The story begins with Louise’s husband asking one evening, “”Do you want to make a baby?” It’s this point in time that’s marked as the present (and is rendered in present tense), but the bulk of the story shuttles between the past and the future. From the benchmark moment we get, in other words, flashbacks alternating with flashforwards.

On my three-dimensional scale, Chiang gets credit for innovation. Stories told in the future tense are pretty rare, especially when the events are presented as memories. And he makes the narrational premise clear. After a few pages, it’s established that Louise purports to know things yet to happen. The tenses cooperate: Present for the baby-making moment, past tense for the past events, future for the future ones.

We’re used to characters who know their past, but how can one know her future? For the story-maker that reduces to: How to motivate Louise’s knowing the future?

The answer is aliens. In the past, Louise met her husband when floating seven-legged creatures came to earth. As a linguist, she was assigned to learn the Heptapods’ language. Gradually she discovered that they had a mentality that refused causality and sequence in favor of a holistic view of time. Their language, to put it crudely, gave them access to past, present, and future.

By learning their language Louise absorbed, to some extent, their world-view. (Yes, the untenable Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is invoked.) Her precognition allows her to know, moments before she and her husband conceive the girl, what her daughter will do from her childhood right up to her early death. Louise also knows that she and her husband will divorce and find new partners. For us, these episodes are rendered as flashforwards from the Now, even though for Louise they are, paradoxically, memories (of things yet to happen).

Chiang’s story explores the emotional effects of knowing the future and deciding not to try to change it. For all I know, this may be another innovation in the realm of speculative fiction. Most time-travelers seek to alter the past or the future, but Louise is aware of the paradoxes of time travel. If you know the future, you can freely decide to alter it by choosing differently at crucial junctures. Marry somebody else, and you’ll change what happens afterward, so you didn’t really know the future. But Louise comes to believe that free will is a part of linear, causal thinking, the sort that the Heptapods have given up.

The existence of free will meant that we couldn’t know the future. And we knew free will still existed because we had direct experience of it. Volition was an intrinsic part of consciousness.

Or was it? What if the experience of knowing the future changed a person? What if it evoked a sense of urgency, a sense of obligation to act precisely as she knew she would?

The Heptapods know that they will need help from Earth in 3000 years, and they presumably know that they’ll get it, but to fulfill that future they need to ask. The story’s analogy is to the daughter’s wanting to re-hear a story she knows by heart. As a story reader replays a known tale, the aliens perform the incidents that make things inevitable.

So Louise accepts her role in playing out whatever future is predetermined. For this reason she can address her (future) daughter with foreknowledge of the pains and delights that are coming, accepting them as part of a seamless whole.

Image + sound + time

Lacking a tense system like language, cinema has devised other time signals. In the classic flashback we get a combination of them. We’re presented with a speaking or remembering character, a track-in to her, perhaps some music, a hint in the dialogue that we’re going into the past, a dissolve, perhaps a voice-over indication, and then a scene obviously situated in an earlier period. Filmmakers have discovered ways of altering some cues (cuts replace dissolves, tight close-ups replace track-ins) and deleting others (music and voice-over seem fairly optional now). Other cues are added for clarity, such as a different color palette for scenes in the past, or perhaps slow-motion imagery, or sound from the past that leaks in over imagery in the present.

Of course films use written and spoken language too, and so they can deploy tenses and time tags. Sometimes that can help us understand the time status of the scenes we’re seeing.

Voice-over is very helpful here. Take another Le Carré example, this time from Fred Schepisi and Tom Stoppard’s adaptation of The Russia House. Play the clip below and you’ll see what I mean.

Katya’s delivery of the covert manuscript, given on the image track, seems at first to be in the present. But the voice-over office conversation, only gradually shown through intercutting, is later than the Moscow incidents we see. So the present, the opening Now, is established on the soundtrack, while the image is in the past. As in fiction, the twin cues of verbal tense (“she visited”) and a time tag (“a week ago”) confirm the status of the Bookfair scene. The innovation comes when Stoppard and Schepisi don’t frame the Moscow scene by offering us the present-time office conversation before we see Katya–in effect, establishing the Now before showing us the Then. It’s an economical tactic of exposition, an elliptical revision of the phone conversations about the police investigations in M.

A voice-over can be in same time period as the images, of course, if it’s an inner monologue, a report on what a character is thinking at the moment. But voice-over commentary is often positioned as in the present with the images assumed to be in the past.

The voice-over present can be specified, usually through a lead-in scene showing the speaker recounting or recalling things at a particular time. Or the voice can be in a vague present, a zone we take as simply “after the events of the story.” It’s this no-man’s-land Now that leads us astray in Laura and other tricky films from the 1940s onward. Uncertainty about who’s speaking from when can be a source of interest in its own right. In Road Warrior, the revelation of the source of the opening voice-over provides the final surprise of the film.

So Heisserer and Villeneuve had an opportunity to follow Chiang in using the future tense in the voice-over for Arrival. It would surely have been an innovative move for a film. But they don’t do it. Why?

From premise to twist

Flashbacks are temperamental little buggers. Hard to know when and how to use them.

Eric Heisserer, 150 Screenwriting Challenges

Heisserer was a keen fan of Chiang’s story and spent years trying to get backing for a film version. He recounts various difficulties in online interviews (here and here, for example), but I want to focus on a couple of other problems he faced.

In a general way, the film respects the thrust of the story. At the close, you realize that Louise has gained the ability to anticipate the future, thanks to learning Heptapod. But on a fine-grained basis, the film doesn’t spell out her ability as frankly or as early as the story does.

The first image, a view out onto the patio and the lake, shows no people, just a table with a wine bottle and a couple of glasses. Louise’s voice-over does address someone absent: “I used to think this was the beginning of your story.” But the point in time and the person addressed are far less specific than in the literary version. Then we get a quick burst of images of a baby, then a little girl playing with Louise, and soon a young woman lying dead in a hospital bed. This cascade of impressions ends with a shot of Louise walking mournfully down a hospital corridor, followed by a fade-out. Fade up on her striding into a campus building and attending her lecture. Over this we hear her voice-over.

But now I’m not so sure I believe in beginnings and endings. There are things that define your story beyond your life. Like the day they arrived.

And then we’re confronted by the Heptapods, as broadcast on worldwide TV, and Louise’s getting the assignment to talk with them.

The first shot, of the patio, is enigmatic, but fairly soon we get the sense that Louise is addressing her dead daughter. We seem to have a classic prologue. (Compare the opening death of Starlord’s mother in Guardians of the Galaxy.) Across three minutes, we see a mother loving and losing her daughter. Our default assumption is that after the daughter’s death, she has become solitary and emotionally numb. She doesn’t interact with people on her way to her classroom, and when she goes home alone she watches TV reports with a kind of blank anxiety.

The film sets up a schema: The grieving mother needs to get out of herself, and the assignment to communicate with the aliens would seem to do that. Eventually she finds love with the physicist Ian Donnelly as well. This redemption schema is probably reinforced for some viewers by memories of Gravity (2013), another movie about a withdrawn mother who channels her sorrow into heroic action.

As the alien encounters unfold, the film’s narration starts to sprinkle in more images of the lost daughter at different ages. But the images show up rather late. At about 48 minutes, there’s a brief, out-of-focus image of a baby; at about 51:00, a glimpse of the little girl wading. Not until about halfway through the film (57:00) is there a fairly sustained scene between mother and child, when the girl shows Louise a picture of her imaginary TV show. That’s when we learn that the father isn’t with them any more. Later shots of the daughter are salted through the scenes of the increasingly tense confrontation with the Heptapods.

Just as we’re encouraged to take the daughter’s birth, childhood, and death as a prologue that precedes the alien investigation, we’re inclined to take these interruptive shots of the girl as flashbacks. Louise seems to be remembering her daughter.

At about 82 minutes something happens that challenges our basic assumption. In another household scene, the daughter asks about the “science-y” term for a win/win situation, and Louise is stumped. The narration shifts us back to the tent at the site, Ian mentions the term “non-zero-sum game.” Then we’re whisked back to the scene with the daughter, and Louise repeats that.

I felt a bump there. If the scene with Ian’s use of the term comes after the death of the daughter, during the alien encounter, how can Louise “remember” it to relay it to the daughter? For many viewers (probably not all), this opens the possibility that the “prologue” tracing the daughter’s childhood takes place after the alien adventure, not before. The reinforcement for this, visible to me only on second viewing, is that the earlier glimpses of the girl’s growing up are always triggered by scenes showing Louise learning the Heptapod’s language.

The filmic narration creates a sort of duck/rabbit Gestalt switch. Things we thought were past are future, things we thought were present are past. If the patio shot is the benchmark Now, the growth and death of the girl are the future and the Heptapods’ visit becomes a sustained flashback.

Now we see why Louise’s introductory voice-over lacks the future-tense sentences that are so startling in the novella. Including those would have been too strong a hint about the status of the mother-daughter shots. Instead, the opening voice-over uses only the past tense (“I used to think”) and the present (“But now I’m not so sure”). Another moment in the voice-over tilts us toward thinking of the image bursts later as flashbacks: we hear Louise murmur over the dead girl. “Come back to me.” Her yearning to reconnect to her daughter inclines us even more to consider the visions of the girl later as flashbacks.

Redundancy is your friend

Okay, pretty innovative—and an interesting departure from Chiang’s story. Instead of telling us at the outset that Louise has precognition, the film holds that as a surprise, and makes us think that her anticipations are actually memories. And we have motivation: as in the story, it’s the alien encounter that endows Louise with precognition. But what about my third consideration, clarity?

I said that not everybody will probably catch the echo of Ian’s “non-zero-sum game.” The last half-hour of the film devotes itself partly to reiterating the news that Louise can discern the future.

Her impulsive visit to the Heptapods late in the film explains why they dropped by. They know they’ll need humans’ help in the future, so they come to make that future happen. At the ninety-minute mark, one speaks, and we get a big old subtitle: “Louise sees future.” If you doubt the Heptapod’s insight, another flashforward soon shows Louise explaining to her daughter why her dad left. Louise “made a mistake” by telling him about a rare disease—presumably the one that would kill their daughter. We’re left to understand that after she told him that she knew their child was fated to die young, he couldn’t take it. The delayed exposition, judiciously repeated, lets the pieces fall into place. We may even start to surmise that Ian is to be that husband, earlier identified as a scientist.

Like the aliens’ sentences, the film is circular. Heisserer told Vox:

When I completed the first draft and the bookends of the first three pages and the final three pages, it felt like I was drawing a narrative circle and I just closed the loop. That felt right.

The narration buckles the film shut by returning to the view of the patio, which is intercut with Louise and Ian embracing. Ian proposes that tonight they make a baby. The fact that Heisserer’s script displaces to the very end what was the opening of Chiang’s story is a fair index of the transformation he has wrought. What was a premise of the novella becomes a reveal in the film.

But the motivation is the same. Flashforwards aren’t exactly parallel to flashbacks, as far as viewer psychology is concerned. Flashbacks are assumed to be veridical unless there’s reason to doubt them (as in trial and investigation films, where people give differing versions of events). The default is that flashbacks really happened, unless there are contrary indications.

Flashforwards, on the other hand, can be of two types. They might proceed from the film’s external narration. In Easy Rider, Petulia, and They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? we get glimpses of future events that no character can know. In such cases, the images are usually enigmatic enough that we can’t be sure about the import of what we’re seeing. Flaming motorcycles, the protagonist tossing a bouquet into the water, a brief cutaway to a man in a police wagon (below, from They Shoot Horses): these are teases, not fully informative scenes, and they interrupt the main present-time action.

Alternatively, more identifiable flashforwards are usually motivated as a character’s precognition. They aren’t necessarily reliable. Flashbacks normally represent “actual” pasts, but flashforwards coming from mediums, psychics, or possessed children are only possible futures. Indeed, one task in such films is to prevent the apparent future from coming to pass, as in Minority Report and It Happened Tomorrow. The past is closed, but in subjective flashforwards, the future is usually open.

How, then, do we motivate trustworthy flashforwards? Here. by having infallible aliens certify them. Like “Story of Your Life,” Arrival assures us that Louise’s premonitions are accurate. It’s just that Chiang’s story proposes that early on and then shows how she achieved them. The film is trickier. It misleads us into thinking she has memories of the past when she is actually learning to see the future. She learns more quickly than we do, though eventually we catch up with her.

We’ve also learned that flashforwards can masquerade as flashbacks—if they’re deployed carefully enough.

Adding the ride

Explaining, very clearly, that Louise is knowing her future is only one task of the last stretch of the film. Another task is preventing a military attack on the aliens.

In Chiang’s story, the creatures simply leave. But Heisserer has explained that he felt the plot needed more conflict, so he added the prospect of brass hats eager to confront the visitors. The Heptapods, Louise suggests, have landed at various places around the world to induce nations to forget their differences in a common purpose. The Americans are suspicious, and General Shang of China breaks away from the alliance and takes steps to attack the ship near Shanghai.

Of the civil turmoil and military threat that fill out the plot, Heisserer noted in the same Vox interview:

The story doesn’t really have any conflict of that nature. It doesn’t need to. It’s a lovely literary conceit in its own right and works without that drama.

However, our early attempts a building this narrative without that conflict added felt very flat, and felt like there were no stakes. There was no ride. The more we played with it, the more Denis and I both realized that if aliens did land on earth and the public didn’t get immediate answers as to what their purpose was, the more everybody would freak out.

In building this climax, the film varies crucially from Chiang’s premise. Now Louise seems to alter the future. She apparently summons the will to induce General Shang, at a future celebration of the successful mission, to give her his private cellphone number and tell her his wife’s dying words. Back in the past, Louise uses this new knowledge to induce the General to hold his fire. All this is presented in a classical ticking-clock drama of suspense and pursuit.

The device is a bit awkward; instead of visiting an actual future, Louise seems present at one where the General, against all plausibility, tells her things she supposedly already knows. And how she induces him to spill all this is unclear, at least to me. The climax also breaks with the original story’s idea that Louise doesn’t exercise free will but accepts her role in the course of time.

More often than one might expect, classically constructed films break some of their self-imposed rules in the rush to a climax. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) is one of my favorite examples, in which the climax violates the story’s method of pod-cloning. Sometimes an exciting denouement or a shocking twist tends to make us forget not only plausibility but also the premises that have operated over the previous ninety minutes.

An unsympathetic critic could object to the injection of a chase, a deadline, and a last-minute salvation of the mission, as well as the one-world moral of the movie. But to enjoy Hollywood, as with enjoying friends and other aspects of life, you have to accept, and even come to enjoy, the flaws too. The center of the film remains our transmutation of sympathy for a grieving mother into sympathy for a woman who knows she will be grieving for a child yet unborn, and yet embraces her destiny. The formal strategies serve to vividly convey this reversal of feeling, in the process ennobling a character reconciled to the transient joys of life.

Kenneth Burke once characterized literary form as “the psychology of the audience.” Filmmakers, like all artists, have recognized this from almost the beginning, but it may seem that today’s creative community is more self-conscious than ever before. If “form is the new content,” as I’ve suggested before, it’s a welcome development. Filmmakers are exploring lots of possibilities for engaging our minds and emotions, while still striving to keep their stories understandable to a large audience. Arrival could not have been made in my sacred 1940s, but its deft innovations build upon a foundation that was laid then.

Thanks to conversations with Jeff Smith and Kristin about Arrival. Thanks also to Merijoy Endrizzi-Ray and Jacob Rust at Madison’s Sundance Theater.

Jeff Goldsmith has an enlightening interview with Eric Hisserer at Screencraft. Ted Chiang’s novella is in the collection Stories of Your Life and Others. Burke’s discussion is in the essay, “Psychology and Form.”

The first quarter of Le Carré’s Our Kind of Traitor consists of an “intercut” sequence between past events and present interrogation that, in its free use of tenses, time tags, and other devices, seems to aim at a literary equivalent of the Russia House film opening. A pity that the recent film of Our Kind of Traitor didn’t try for a cinematic equivalent.

For more on modern treatments of narration and plot structure, try here. For further discussions of 1940s treatments of time-juggling, here are some blog entries.

P.S. 3 December 2016: The original entry didn’t use Minority Report or It Happened Tomorrow as examples of averting the future. They’re corrections to my original mention of Don’t Look Now, which was not an accurate example. David Cairns wrote to remind me of that, and to point out that the glimpse of the future we get in that film is in an interesting way akin to what we get in Arrival, and I hadn’t noticed that. For those who haven’t seen Don’t Look Now, I won’t add to an already spoiler-heavy entry. I’ll simply thank David, whose exemplary blogsite Shadowplay (currently hosting a blogathon under the rubric of The Late Show) is a must for every film lover. His new film, The Northleach Horror, is nearing completion; details here.

Arrival (2016).

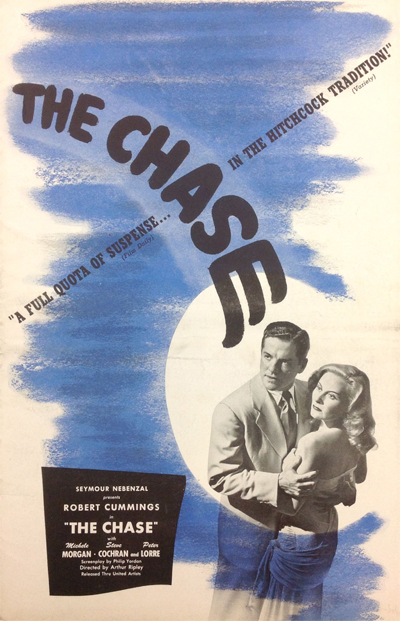

Back on the trail of THE CHASE

DB here:

How did The Chase (1946) come to be such a weird movie?

Exploring that question in an August entry, I complained: “I haven’t located any scripts, alas.” I was forced to use what evidence I could muster from trade papers and the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Now I’ve learned of one screenplay for the film, and it confirms my primary conjectures—while offering some other complications. (What else is new?) You may want to return to that earlier entry before moving on with this, but this can stand on its own. Of course there are many spoilers ahead.

The screenplay is signed by Philip Yordan and dated 17 April 1946, with some inserted pages dated 16 May. It is held in the collection of the producer, Seymour Nebenzal, housed at the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Droessler and Christoph Michel supplied information about this document, and Miriam Landwehr produced a detailed synopsis and a comparison to the finished film. I’m very grateful to them for their assistance.

When is a dream not a dream?

The problem of the film as we have it is its And-then-I-woke-up plot. Navy veteran Chuck Scott takes a job as a chauffeur to Eddie Roman, who runs a smuggling racket with his henchman Gino. Roman’s wife Lorna longs to escape the marriage and induces Chuck to buy her passage on a ship bound for Cuba. Chuck, infatuated, flees with her, but in Havana she is killed in a nightclub and Chuck is the prime suspect.

Escaping from the cops, Chuck is killed by Gino, who has trailed the couple to Cuba. And now Chuck wakes up. We realize that the escape to Havana has been a dream that he’s had on the night he and Lorna were to sail. This rupture in the story action has been a crux for the film’s many admirers—a sheer piece of noir bravado.

Unfortunately, the dream has triggered Chuck’s old war trauma and he has amnesia. He can’t recall anything of the Miami episode. He returns to his doctor, who helps him recover his memory, rescue Lorna, and actually set out for Cuba with her. The film ends with the two in a carriage outside the nightclub that they visited in Chuck’s dream. This too has aroused a lot of comment; how could they visit in reality what Chuck only imagined?

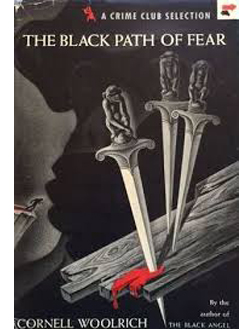

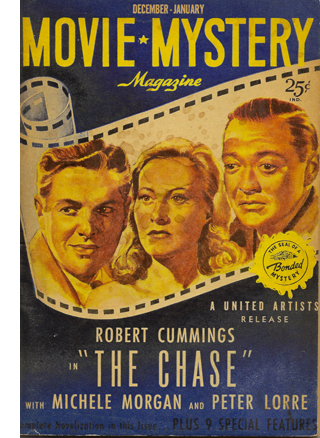

These and other anomalies in the film, along with a 1946 remark by Nebenzal about eliminating the screenplay’s “flashback,” led me to look into the production. Crucial as well were Cornell Woolrich’s original novel, The Black Path of Fear, and an anonymous novelization of the film published in Movie Mystery Magazine (December—January 1946). Since novelizations were often written on the basis of scripts, I inferred that aspects of the screenplay might have been preserved in that publication.

These and other anomalies in the film, along with a 1946 remark by Nebenzal about eliminating the screenplay’s “flashback,” led me to look into the production. Crucial as well were Cornell Woolrich’s original novel, The Black Path of Fear, and an anonymous novelization of the film published in Movie Mystery Magazine (December—January 1946). Since novelizations were often written on the basis of scripts, I inferred that aspects of the screenplay might have been preserved in that publication.

The original novel begins in Havana, where Lorna dies in the nightclub. Fleeing the police, Chuck tells Midnight, a woman who hides him, of how he met Lorna and Eddie Roman in Miami. At the end of this flashback, he sets out across Havana to find Lorna’s killer.

The central production decision, evidently taken by Nebenzal early on, was that in the film Lorna was to live and unite romantically with Chuck. How to keep Lorna alive and yet retain the dramatic murder and Chuck’s flight from the law?

Yordan’s screenplay, fairly closely followed by the novelization, adhered to Woolrich’s opening by starting with the Havana murder and letting Chuck recount the Miami backstory to Midnight. But then, on the trail of Lorna’s killer, the screenplay has Chuck killed by Gino. Then Chuck wakes up. We realize that the entire first part of the film—running an hour or so—has been his dream. So Lorna is kept alive for a genuine partnering and flight with Chuck.

The screenplay’s problem is that Chuck has dreamed not only the imaginary murder but everything leading up to it. What he tells Midnight in his dream includes all the veridical backstory of his becoming Roman’s chauffeur, learning of Lorna’s desire to escape, and fleeing with her. The dream, false in its Cuban sections, is faithful to actuality in most of its Miami stretch—the flashback that novel included and that Yordan retained.

That Miami backstory was the flashback that Nebenzal eliminated late in production, claiming that he felt there were too many flashback movies in release. He shifted the Miami scenes to the front of the movie, where they serve as conventional chronological action, and made the Midnight encounter in Chuck’s dream a straightforward scene in which she helps him evade the police.

Not quite rounded with a sleep

The screenplay and the novelization fool us by eliminating the dream’s “front frame.” There’s no scene showing Chuck going to sleep; we’re immediately in his imaginary Havana. By contrast, contemporaneous films using the dream device supplied at least a minimal setup. The Woman in the Window (1944), The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945), and Strange Impersonation (released April 1946) each include an innocuous piece of action that, in retrospect, indicates that the protagonist has fallen asleep and dreamed what we’ve just seen. The return to those setup situations tips us off that we’ve just seen a dream.

Evidently Yordan wanted to take this trend further by lopping off the setup altogether and plunging us straight into a dreamscape for a very long stretch. By killing the protagonist, Yordan supplied a shock that, given Hollywood conventions, would have to be recouped somehow. The dream device does that, bringing both hero and heroine back to life.

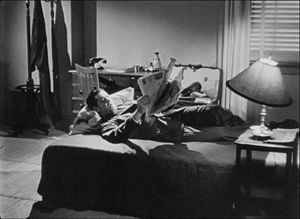

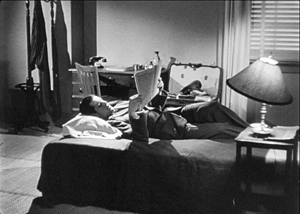

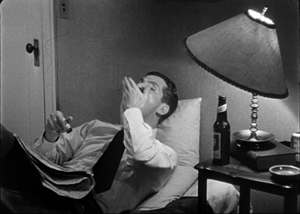

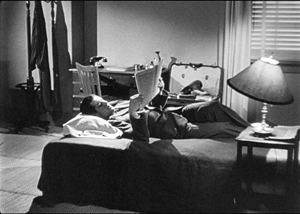

Once the flashback was shifted to the front of the film, however, Nebenzal needed a more conventional front frame to bracket off the dreamed escape to Cuba. Therefore he supplied a scene showing Chuck lying down just before he and Lorna are to flee. This scene is not in the screenplay or the novelization.

As in other films of the time, the setup is equivocal. Chuck lies down and reads a newspaper and just barely starts to yawn as the film fades out. Cunningly, as I pointed out in the earlier entry, there’s a bridge of diegetic music—the piano concerto that Roman is listening to on the phonograph—and we then see Roman and Gino in the living room. A more typical dream film would remain attached to the dreamer; we might see Chuck get up from the bed, close his suitcase, and sneak out with Lorna. Instead, we’re with Gino when he goes to Chuck’s room, finds him gone, and reports his departure to a curiously listless Roman. So Chuck dreams Gino’s discovery of his departure. The shift to Roman and Gino seems to corroborate the objectivity of what’s happening, especially because the film’s non-dream stretches have freely intercut Chuck’s actions with those of his boss.

In the earlier entry I pointed out some visual anomalies among the framing scene, the scene of Gino visiting Chuck’s room, and the waking-up scene. Changes in props suggest that the retakes to which Nebenzal alluded in a memo in August may have included shooting the setup frame. By mid-September he was announcing that he had abandoned the flashback, and the film was completed by 7 October.

For those of a fussbudget inclination, like me, you can find hints that the original waking-up scene was modified to fit the front frame that was added later. Here’s the waking-up framing shot, which tracks back from the ringing telephone.

The lighting, setting, and camera angle closely match what we realize in retrospect was the setup of Chuck falling asleep.

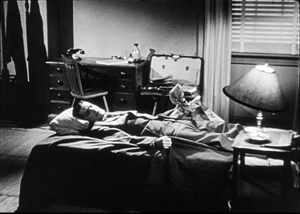

But the closer views of Chuck woozily coming out of his dream vary from neighboring shots in tonality and in the position of the chair behind him. (In the master shot it’s angled to our right, but in this and other shots it’s angled to the left.)

Later shots in the waking-up scene show different positions of other props. While the chair remains angled to the left, the lampshade (tipped in the earlier establishing shots) is upright now; there’s no longer a magazine behind the lamp; and the water carafe and pills on the desk are in a slightly different array.

In addition, the lighting scheme is somewhat different; the interior of Chuck’s suitcase is blown to pale gray in the framing shots but in the ones above it’s far darker. And the coat and coatrack visible on frame left of the dream frame aren’t visible in the widest shot we get later in the scene, the second one above.

I know: Picky, picky. We could put these disparities down to routine continuity errors. But their patterned differences are consistent with their being part of a patchwork. It seems plausible that most of the waking-up scene was shot during principal photography, but the opening shot of that scene, along with the falling-asleep frame that was added, was filmed during the retakes that Nebenzal oversaw in August and September.

Cabin fever

One of the weirdest aspects of the film we have is the ending. Eddie Roman and Gino, racing to stop Chuck and Lorna from escaping, smash into a locomotive. This chase is intercut with Chuck and Lorna in a ship’s cabin waiting to sail off. The problem is that, for censorship reasons, this unmarried couple can’t easily be shown running off together, and sharing the same quarters at that.

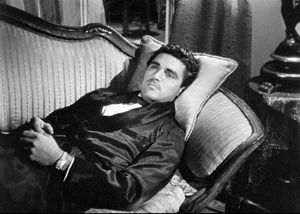

Several commentators have noted that the set recalls the one that Chuck dreams (below, left).

The cabins aren’t all that much alike, though the clock on the back wall probably pops out as a reminder. Yordan’s script asks that the second cabin suggest the first one.

This set should be basically the same as the set used before yet there must be distinct differences.

It seems that Yordan wanted to hint that Chuck’s dream was a sort of premonition of the trip they’d wind up taking. The dialogue flirts with the possibility. As Lorna says, “For once in my life I wish I could want something that was good for me,” the screenplay goes on:

At this point, something happens to Chuck. He becomes aware that he has heard this line before. Suddenly he knows everything that she is going to say, everything that’s in her heart.

When he suggests she tries to recover her lost innocence, she asks: “You haven’t been drinking, have you?” he replies: “No–just dreaming.”

He adds that he’s dreaming “what a chauffeur’s not supposed to dream about.” Wanting to give her freedom, he decides not to go to Cuba with her and vows to reenlist in the service. They don’t embrace. Quick dissolve to Chuck marching in a military parade down Fifth Avenue. His decision not to have a runaway romance is rewarded by the sight of Lorna, now his wife, cheering him from the sidewalk. It’s on this burst of patriotism that the screenplay ends.

Was this preposterous epilogue ever shot? Had it been jettisoned by the start of production on 16 May, presumably the 14 April script wouldn’t have included it (since it includes some revisions dated 16 May). But the parade isn’t in the novelization, which is otherwise very faithful to the April script. The novelization was based on a script sent to the magazine in late June or early July, so perhaps the parade was dropped after principal photography began. We do know that in September Nebenzal was shooting alternative endings.

The novelization’s cabin scene follows the screenplay’s tack, indicating that Chuck’s “dream” of union with Lorna should end with the couple splitting up. But she resists his suggestion, and things take a familiar turn.

And in the next instant, Chuck’s mouth found her warm lips, shutting off her words, his arms pressing her to him crushingly.

This burst of passion is interrupted by a telegram from Dr. Davidson telling Chuck of Eddie’s death. The message asks the couple to return, in a wry phrasing: “Before you get into any real trouble in Havana.” This version concludes with them agreeing to get off the ship and get married, so they never sail for Havana. No parade finale here.

The film’s last moments, as any aficionado knows, are something else again. The scene in the cabin is played eerily, with Chuck striding in and glancing at a newspaper he’s carrying. When she asks when the boat will get started, he says, “It doesn’t matter now.” Did the newspaper carry news of Roman’s crash? (Unlikely, so soon.) And why doesn’t he take Lorna in his arms, for the clinch and fade-out? Did the production team not have the footage, after shooting the lead-in to the parade?

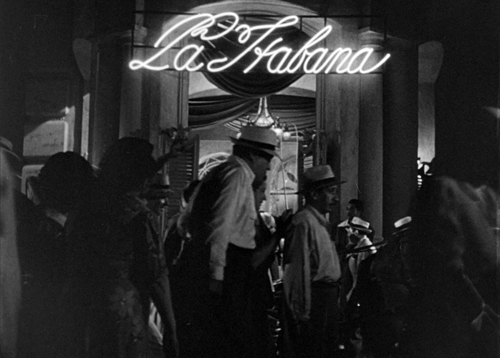

The film’s epilogue, absent from both the script and the novelization, casts aside any concern about whether this furtive couple has married or not. We’re back in front of the La Habana club, with Chuck and Lorna in the carriage declaring their love for one another.

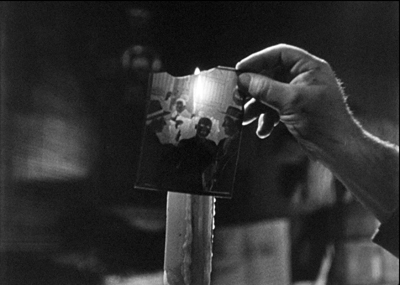

This scene (below left), as I suggested in the August entry, is quarried out of footage shot for Chuck’s dream (below right), right down to the grumpy driver.

The result is pretty Buñuelian. You can call it a reenactment of the dream in real life. Or you can say that it plunges us back into Chuck’s dream–leaving the shipboard resolution suspended. In their haste to wrap things up, Nebenzal and his director Arthur Ripley give us the conventional clinch, all right, but with a screwball spin.

So my conjecture about the original ordering of the film’s plot is borne out by the discovery of the screenplay. But we still don’t know why the film, once the parade epilogue was jettisoned, doesn’t include the clinch in the cabin and the resolution to marry. Both were in the novelization. Why go back to the Habana club and the recycled footage? Only further research into other production documents can tell us for sure. In the meantime, we’re left with another Forties film that flaunts the unexpected virtues of accidental innovation.

The Chase was restored by UCLA and is available on a handsome Blu-ray edition from Kino Lorber. My references to production materials and press releases for the film come from the sources listed in the earlier entry. One of my illustrations above comes from a French novelization that I haven’t yet found; I assume that it’s a translation of the English one, but maybe not.

This isn’t the first time I’ve returned to fuss over an earlier entry. I did it with The Ambersons Poster Mystery (here and here and here and here) and twice with Hitchcock’s ideas of suspense (here and here). If I keep trying, maybe I’ll get it right.

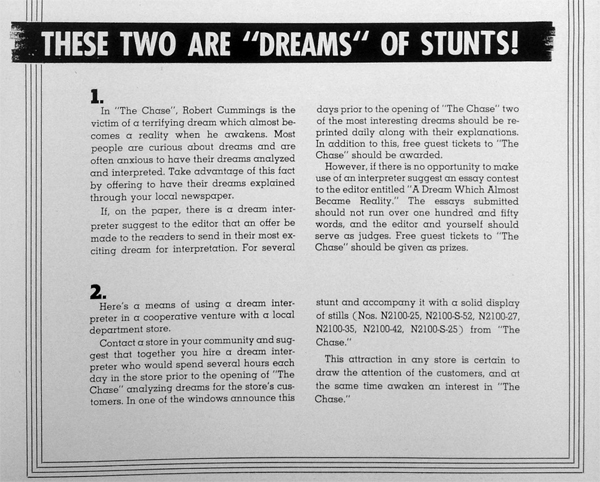

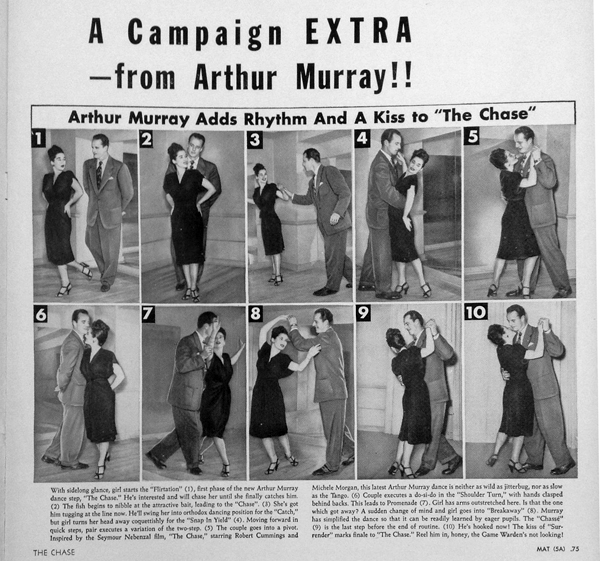

Surprisingly, the dream device was built into the studio’s publicity to a small extent. (See images below.)

P.S. 2 November 2016: David Koepp, film noir aficionado, adroit screenwriter and director, and one of the People We Like, writes:

I love your blog post on The Chase. Just read it, and, coincidentally, I just watched The Chase yesterday and had been meaning to e-mail you about it. You’ve said pretty much all there is to say about that movie already (and with your customary thoughtfulness), but just two things I wanted to add.

First, this film stretches the kind phrase “bold use of coincidence” to new extremes. There is seemingly NO situation that they weren’t comfortable having resolved, furthered, or complicated by coincidence, and in a strange way I kind of came to appreciate that. I mean, it’s economical, if nothing else.

But my second thing is more interesting. It’s funny that you focus today on the falling-asleep framing device for the dream sequence, because I had an observation in that very spot, a curious bit of staging which I didn’t fully understand, but now I think I do thanks to your post. After the master shot pulls back from the phone, Robert Cummings goes to the bed and does the strangest thing. He picks up the pillow, tosses it to the foot of the bed, and lays down on the bed for his fateful nap, WITH HIS SHOES ON. Think about that — he picks up the pillow from the socially agreed-upon head of the bed, tosses it to the foot of the bed, and then lies down with his dirty shoes on the now-unprotected sheet at the head of the bed. Who in God’s name would do that?

Only one person I can think of — an actor who’s been asked by the director to do it to protect the composition. In its widest position, the lamp in the right foreground blocks the head of the bed and the remainder of the set to the right, and the master shot plays beautifully as one long pullback. So, at first I figured the director just liked his master and asked the actor to toss the pillow to the foot of the bed, i.e., “I know it’s weird, Bob, but would you mind?, it’s a lovely shot and I don’t want to have to break it up and turn around to shoot you at the head of the bed.”

But there’s another possible reason, if your reshoot theory is correct. Which is that they were rushing to squeeze in a clarifying reshoot, struggling to recreate the set and props as they were in the original footage, and they didn’t want/didn’t have time to/couldn’t afford to rebuild the other walls of the set to accommodate. Plus there’s a door in the wall to camera right, and a hallway outside it with a return. More stuff to build–way too expensive and time-consuming for the hurry-up-and-grab-this approach they’d need for a reshoot with the studio and the release date breathing down their necks.

Maybe? Who knows! But it’s fun to speculate.

It’s interesting that in the April screenplay, Yordan doesn’t specify that Chuck is sleeping at the foot of his bed. We simply have: “Chuck lying on his cot, fully dressed in his chauffeur’s uniform.” David’s point is persuasive to me. It would be harder to compose a pull-back from the phone (a gradual revelation that Yordan’s screenplay insists on) if Chuck were lying at the head of the bed. The awakened shots not made during the reshoots also have Chuck sleeping at the foot of the bed, but David’s point about the composition makes sense for those too.

David’s mention of Chuck’s position makes me think about something else. Lying at the foot of the bed also suggests, to me at least, an intention of not going to sleep but rather just relaxing. Had Chuck stretched out on the bed normally, might we be more inclined to suspect a dream was coming on?

Thanks to David for sharing the practical filmmaker’s perspective! Now more than ever I’d like to see the daily set reports for this movie.

P.P.P. 13 November 2016: For hardcore fans only: At the suggestion of Soren Schoff, a local friend, I obtained a copy of the UK novelization of The Chase, published by Hollywood Publications of London in 1947. It’s signed by Kit Porlock, a name one sees on many novelizations published in London in the Forties. This text is quite different from the Movie Mystery Magazine edition, and it adheres closely to the finished film. But there are interesting aspects to it.

Like the movie, it starts with Chuck in Miami and follows him through the romance with Lorna. The front end of the dream frame, just before he’s about to run off with Lorna, is given more explicitly than in the film:

Like the movie, it starts with Chuck in Miami and follows him through the romance with Lorna. The front end of the dream frame, just before he’s about to run off with Lorna, is given more explicitly than in the film:

He stretched out on the divan for a while. He had nothing to do for the next four or five hours. A nap would be sensible if only he could get to sleep.

He took a couple of his pills and tried to relax. It was no good. Too many images and fancies revolved in his brain. He readjusted the pillow under his head and sprawled out luxuriously Just to have an hour or so would do him the world of good. . . . .

This ends a chapter. The next chapter begins with Gino entering and finding Chuck gone, more or less as in the film.

When Chuck comes out of the Havana dream, the novelization likewise makes sure we know it wasn’t real (“All that was so vivid to him had only been a dream!”). But the amnesia has kicked in and so Chuck has to seek help from Dr. Davidson, as in the film.

There are two only other major differences from the finished film. For one thing, like the US adaptation, the UK one ends with Lorna and Chuck in the ship’s cabin. Here it’s clear that the ship has delayed departure long enough for a newspaper edition to arrive and announce the deaths of Roman and Gino in the car crash. In the film, Chuck simply comes in with a folded newspaper, and we aren’t explicitly told why he now thinks the two of them are safe. Maybe the final release just dropped his act of showing her the news item.

The second difference from the film is that, like the MMM version, the story ends in the cabin with the couple united in love. There’s no epilogue in the carriage outside the La Habana club. This novelization, said to be “from the original film script,” isn’t, but perhaps it’s based on a rewrite that was closer to the final release–that is, after Nebenzal had shifted the flashback to the front of the plot and had jettisoned the military-parade finale. But we still have to wonder why the final cabin clinch in both novelizations isn’t there in the film, and why the carriage scene isn’t in either novelization. The Chase remains elusive.

The Chase (1946) United Artists pressbook.

Replay it again, Clint: Sully and the simulations

Sully (2016).

What happens in the Forties doesn’t stay in the Forties. That’s one motto of the book I’ve just finished on Hollywood storytelling in the period 1939-1952. The argument is that several narrative conventions that crystallized in that era became part of the Hollywood tradition and continue to shape the films of today.

I say “crystallized,” not “suddenly appeared,” because in general terms every significant technique I pick out has precedents in earlier years of American filmmaking. Forties filmmakers didn’t invent flashbacks, voice-over narration, dream sequences, and the like. What Forties writers and directors did was consolidate those techniques into major norms. They went on to explore, sometimes with startling delicacy, the techniques’ range and power.

This pattern of scattered invention, followed by consolidation and refinement, isn’t uncommon in the history of technology. The computer mouse was devised by several companies and individuals, but it became ubiquitous in the 1980s thanks to Microsoft and Apple. What historians call the diffusion phase of change created a foundation for future development.

The same sort of diffusion sometimes takes place in cinematic form and style. For example, flashbacks in the 1930s were fairly rare and, except for The Power and the Glory (1933) and a few other films, fairly perfunctory. They simply filled in information that had been suppressed earlier, usually providing the solution of a mystery. During the 1940s, when flashbacks became more widely used, filmmakers were obliged by the pressures of competition to explore the technique’s finer-grained possibilities, as in Kitty Foyle (1940), Citizen Kane (1941), Lydia (1941), and many other films.

Once a technique becomes common, and refined in its usage, later filmmakers can treat it as a taken-for-granted option. It seems likely that the development of flashbacks in the 1940s, in both American and other cinemas, laid the groundwork for efforts like Hiroshima mon amour (1959). American filmmakers reworked flashbacks in creative ways in Petulia (1968), They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969), and other films influenced not only by 1940s Hollywood but also by 1950s and 1960s European cinema.

Call me biased, but now nearly every mainstream movie I see seems indebted to storytelling strategies consolidated in the 1940s. Take Sully. In less than ninety minutes, it runs through a wide range of narrative techniques. The fact that we take them so completely for granted, and understand them so swiftly, indicates the stability of what we call a Hollywood movie. It’s kind of miraculous that filmmakers continue to find ingenious ways to fulfill norms that were locked into place seventy years ago.

Clint the classicist

American Sniper (2014).

Before I get to Sully, let’s pause on other recent films directed by Clint Eastwood. (Yes, spoilers will be involved.) They illustrate just how fully narrative techniques associated with the 1990s-2000s have become mainstream resources. Although those techniques are largely revisions of possibilities crystallized in the 1940s, most people know them in their modern guise. Today’s audiences are more familiar with the intricately out-of-order flashbacks of The Prestige (2006) than those found in The Killers (1946) or Backfire (1950).

Hereafter (2010), written by Peter Morgan, lays out three story lines. A French TV journalist, after nearly drowning during a tsunami, is convinced she has had a vision of the afterlife. A London boy yearns to contact his dead twin. An American construction worker, as a result of perilous childhood surgery, has acquired the gift—or, as he says, the curse—of being able to communicate with the dead. Each protagonist’s experiences are treated as separate blocks, crosscut ever more swiftly, until the three converge at a London book fair. The American helps the boy contact his brother, and by meeting the journalist, who has written a book about her research into the hereafter, begins to feel he can rejoin the world.

Hereafter is what I’ve called a network narrative: a plot centered on several more or less equally weighted characters with independent goals. Their fates intertwine by chance (or fate). In the 1930s and 1940s, network plotting tended to be confined to a locale or vehicle, typically in a Grand Hotel situation. More dispersed and numerous story lines emerged with Altman’s Nashville (1975), though even that has a circumscribed time limit. During the 1990s and 2000s, both spatially confined versions and more free-ranging ones became quite common in filmmaking across the world. Hereafter revives the strategy, tying the parallel plotlines to a conception of a realm after death.

Hereafter’s second primary expressive option involves flash-cut visions of the afterlife—blurry, distorted images that give only a glimpse of what Marie the journalist and George the medium “see.” These aren’t sustained, so that, for instance, when George relays to someone what the departed is saying, the film stays objective, simply presenting George’s report on what he’s being told.

This reticence about showing us the Beyond allows us to reflect that at one crucial moment, perhaps George is improvising the advice that he claims to be passing along to the dead boy’s twin.

In a final twist, George’s curse changes to something more like a gift. When he manages to arrange a rendezvous with Marie, his vision of the afterlife is replaced by precognition in this world. Now his vision, clear and sustained, shows him kissing her. Or maybe he’s gained access to normal wish fulfillment.

In either case, the Hollywood clinch gets re-motivated.

Jersey Boys (2014) presents the rise of the Four Seasons, with emphasis on the lead singer, high-pitched and high-strung Frankie Valli. Although the bulk of the film takes place in the 1950s and 1960s, it climaxes with the group’s reunion at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990.

A common option would be to start at the reunion and then flash back to trace the group’s rise. Instead, the film roughly follows the layout of Marshall Brickman’s and Rick Elice’s book for the Broadway show. That presents the ups and downs of the group’s career chronologically, with each member narrating a block of scenes. In the stage version each block is labeled, cutely enough, with a season, from ebullient spring to doleful winter, with an extra-seasonal epilogue at the Hall of Fame.

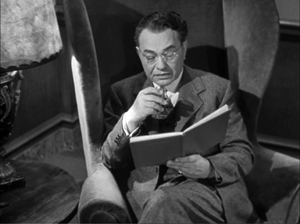

The film version, also scripted by Brickman and Elice, doesn’t flag the seasons but does incorporate round-robin narrators. In the film’s opening Tony DeVito introduces us to the neighborhood and the formation of the group.

Later, singer-composer Bob Gaudio (above) and bass guitarist Nick Massi comment on stretches of the group’s rise and fall. They feel free to criticize each other, as when Nick says the trouble began well before Bob thought. These narrating moments are handled through to-camera address: each Season looks straight at us, explaining what’s happening, or just happened, or is about to happen.

Again, to-camera address can be found throughout film history, but the Forties made it salient by letting it bracket the entire film, often as the present-time frame for a flashback (Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, 1948; Edward, My Son, 1949; Young Man with a Horn, 1950; below). It’s rarer to have the narrator interrupt an ongoing scene, turn toward us, and break the fourth wall, but we do find it in My Life with Caroline (1941, below).

The Caroline device was revived in other films, notably Alfie (1966) and much more recently The Wolf of Wall Street (2013). The tweak that Jersey Boys introduces is the fact that the narrator uses the past tense to describe the scene he’s in–an occasional option in The Big Short (2015) too.

The tag-team narration in Jersey Boys doesn’t create sharply distinct blocks, in the Rashomon manner. Each singer’s segment roams pretty freely among other characters’ doings, so there’s no strong attachment to a single viewpoint. But some variations crop up. Frankie is the most minimal narrator. He never turns to the camera to address us, and we hear his voice-over comments only once in “his” stretch of the film. Perhaps that’s because he’s the character whose personal life is most crucial to the plot, and we see everything he’s up to. (Hollywood group protagonists often adopt a “first among equals” principle.) And at the final reunion, each of the quartet turns from the microphone to address us in quick succession, summing up their view of what’s happened. In Jersey Boys, as in Hereafter, some long-standing conventions are given moderately original handling.

American Sniper (2014) is the most linear and traditional of this batch, except for one tactic that becomes more important in Sully. The opening sequence shows sniper Chris Kyle perched atop a building scanning the Falluja neighborhood for enemy action. He sees a woman and child walking toward the Marine convoy, and she passes the boy what becomes visible as a grenade.

Chris must decide whether to fire. We then flash back to Chris as a boy shooting a deer and being told by his dad: “You got a gift.” There follow scenes tracing his childhood and young manhood, and his response to militant bombings of U. S. embassies: joining the Navy SEALS. At his wedding, he’s called to the invasion of Iraq.

This flashback, which consumes most of the film’s first “act” (ending about 25 minutes in), is followed by a return to the moment of decision on the rooftop. To prolong the suspense, the film replays Chris’s spotting of the woman and child with the grenade. He fires and kills both.

This tactic, of coming out of a flashback with a repetition of what initiated it, is yet another storytelling choice we find emerging in the Forties. One clear example is the framing of the long central flashback of Body and Soul (1947). The opening scene shows an eerily empty training camp before boxer Charley Davis wakes up from a bad dream and cries, “Ben!”

A fairly lengthy setup in the present follows before we get a long flashback tracing Charley’s career. At the conclusion of the flashback, again we see the shot of the camp, and again we see Charley awakening. A match-on-action cut takes us from that to the point where the frame story stopped: him lying on the table in his dressing room, just before the big bout.

The return to the camp has buckled the flashback shut in a way similar to the return to the Falluja roof in American Sniper.

The device of the reiterated flashback is developed more unusually in Eastwood’s J. Edgar (2011). The film follows a classic norm for the biopic: In old age, the central character recalls his or her life. Those flashbacks could be motivated as private memory, or as episodes recounted to someone. And in the Forties, that someone was often a reporter or transcriber, as in Edison the Man (1940) and The Great Man’s Lady (1942). If you count Citizen Kane (1941) as a fictional biography, then Thompson fulfills the role of listener.

In J. Edgar, the self-important Hoover has assigned FBI agents to take down his memoirs. Flashbacks inevitably follow. As the film goes on, the narration wedges in “unofficial” flashbacks, mostly scenes with Hoover’s life partner Clyde Tolson, and these are justified as purely private musings.

What’s interesting is that some material Hoover dictates proves unreliable. At the climax Tolson, who has read the manuscript, denounces it as a tissue of lies. We then get repetitions of key scenes from the dictation, all of which show that Hoover wasn’t involved in cracking the big cases he took credit for. The film decisively debunks Hoover’s myth that he was not only a superb administrator but also a heroic, hands-on field commander.

The lying flashback is yet one more minor convention of 1940s cinema. For those who haven’t seen the most important example, I’ll refrain from mentioning the title, but let Thru Different Eyes (1942) and Crossfire (1947) stand as examples. (At one phase of production, Laura, 1944, was planned to have a lying flashback too.) The replay emerges as a way to correct the first impressions.

In tracing precedents for these storytelling choices, I don’t mean to criticize them as unoriginal. The screenwriters of Jersey Boys and Hereafter, along with Jason Hall (American Sniper) and Dustin Lance Black (J. Edgar), are drawing upon models that have been circulating in Hollywood filmmaking for decades, and that became particularly salient in the 1990s and 2000s. These scripts are also revising the techniques in ways that seem to me original to some degree.

As for Eastwood, he’s said to “shoot the script,” so perhaps these more or less up-to-date narrative techniques are brought into his work through the screenwriters. But he’s also often called one of the last “classical” directors. Partly, I think, that’s a reference to his style: his fondness for establishing shots of buildings, shots of people arriving in cars or driving away, shot/reverse-shot dialogue exchanges, and unobtrusive Steadicam. In Jersey Boys, the musical numbers seem rather haphazardly put together, but Eastwood is cogent in developing action sequences, as the firefights in American Sniper show.

It’s not just a matter of style, though. To some extent the narrative strategies I’ve mentioned here have become part of today’s “classical Hollywood filmmaking.” Flashbacks, block construction, replays, to-camera address, network narratives, and bursts of subjectivity are so ingrained in contemporary filmmaking that we might want to think of Hollywood storytelling as a constantly expanding menu that discovers new flavors in traditional ingredients. The basic premises of classical narrative permit an indefinitely large range of variation, both large-scale and fine-grained.

Not a crash, a water landing

Most flashbacks present new information, either in a large block, as in Body and Soul, or in bits, as in J. Edgar. Other flashbacks present old information, mostly to remind us of something we’ve already seen or heard that’s relevant to the moment. Occasionally, a flashback is both a reminder, because it shows us something we’ve seen before, and a source of new information. It’s very common for mystery films and TV shows to use a flashback to an earlier scene in order to fill in whodunit, and how it was done.

Let’s call this reminder involving new information a replay. A replay goes beyond a simple repetition by showing the action in a new light—from a different character’s perspective, or including information that was omitted on the first pass. The latter happens in J. Edgar, when we see earlier scenes corrected to give credit to the actual agents involved.

Replays and other techniques of repetition are given a remarkably central role in Todd Komarnicki’s screenplay for Sully. It’s not surprising because the core incident, Chesley Sullenberger’s landing of a damaged airliner on the Hudson River, is said to have consumed only 208 seconds. There would have been many ways to tell this story; a straight linear account, as in United 93 (2006), must have been a tempting option. Instead, Sully concentrates on the heroic pilot, whose action was supported by comradeship with his co-pilot, and the collective spirit of the passengers, crew, and first responders. In order to add conflict, Komarnicki and Eastwood build up the drama of the National Transportation Safety Board’s inquiry into the landing. The members of the board are initially presented as skeptical antagonists, although by the end, they gracefully acknowledge that the plane could not have returned to the nearest airfields.

The emergency landing is presented in flashbacks, framed by the ongoing investigation. But the film opens with the plane crashing into Manhattan skyscrapers.

It’s revealed as Sully’s nightmare, which haunts him after the rescue. The sequence anchors us firmly in his consciousness; we’ll be more attached to him than to any other character. As an anxiety dream, it presents a sort of what-if version that retrospectively justifies his decision to land on the Hudson. But its emotional tenor reveals his consistent worry throughout the plot that the authorities will judge that he put the passengers’ lives at risk unnecessarily.

Later another version of this Manhattan crash plays out not as a dream but as a waking fantasy, as Sully looks out of a skyscraper window. The scene suggests that he’ll never be able to see this cityscape without imagining the catastrophic alternative scenario. The same fraught feelings crop up in another fantasy passage, when he imagines a TV commentator asking: “Sully: Hero or fraud?” It isn’t just the accusation from outsiders that worries him. He questions what he’s done too. It’s important that the film give Sully enough self-doubt to build our sympathy and to make his final vindication all the more deserved.

Having given us dream and daydream, the filmic narration also gives us memory, in the form of flashbacks to Sully’s younger days, when he fell in love with flying and graduated to testing aircraft in dangerous situations. These affirm his expertise while also showing the quiet determination that can seem a little dour. (He’s told by his flight instructor to smile more.) This serious older man was also a serious young one.

From the start, the Board’s inquiry sets up the need for simulations to check Sully’s decisions. The first set are computer-based, and Sully requests that pilots also execute simulations. The human simulations will become crucial points of conflict at the climax.

One of Sully’s phone calls to his wife back home triggers the first flashback to the fateful day of 15 January 2009. This is launched about 27 minutes in, marking the shift to what Kristin calls the Complicating Action section of the plot. We’re shown Sullly’s arrival at the airport, the assembling of the passengers, and the takeoff. Soon enough, a flight of birds hits and the plane is damaged. Sully and copilot Jeff Skiles radio the air control center.

At this point, our attachment shifts to the controllers, and we hear the pilots trying alternative options. Other aircraft in the area see the plane go down, and the controller is relieved to learn that the landing was successful.

Crucially, we aren’t in the cockpit throughout this first run-through of the landing. Although the film celebrates Sully, the narration initially shifts our attachment to others trying to help him. This tactic also allows the filmmakers to save the most dramatic version of the landing for later replay.

The second major flashback, triggered by Sully brooding in a pub, shows the rescue operation. There’s a replay of the plane’s descent, again refracted through observers. Some are eyewitnesses, but mostly we see coast guard people who leap into recovery mode.

We alternate those views with vignettes of the passengers evacuating, overseen by Sully’s apprehensive effort to make sure all survive. Even after the passengers have been taken aboard the rescue boats, Sully can’t calm down until he’s told that the tally shows that everyone is safe.

The end of the flashback, which I’d say constitutes the Development section in Kristin’s model, introduces the crucial motif of timing, which will be Sully’s defense at the last hearing.

We’ve registered the water landing from the perspectives of the air-traffic controller, of eyewitnesses on the ground, of the first responders, and of the passengers. But what were the 208 seconds like inside the cockpit? This will be the business of the film’s climax, and several versions of it will be presented.

At the final hearing of the NTSB, a public one, the Board members report on the computer simulations. Those indicate that the plane could have flown back to La Guardia or on to Teterboro for a safe landing. Then the Board, through video contact, shows pilots simulating the alternatives, instant by instant starting from the bird strike. These reenactments are a bit like Sully’s nightmare and daytime fantasy, in that they present grim alternative scenarios—hypothetical replays, we might say. Both confirm the computer’s conclusion that the water landing wasn’t necessary.

A fair amount of suspense has been built up by these reenactments. The audience hasn’t seen everything that happened in the cockpit during the crisis. How can these simulations be challenged?

Sully raises the crucial point that the pilots in the simulation had foreknowledge of what they were to do. (In cognitive-science jargon, they were primed.) In fact, the Board admits, the pilots were permitted to practice the maneuver several times. Sully requests that time be added to the simulation, as a way to reflect the real conditions of unexpected decision-making.

So the pilots run the simulations again with a 35-second lag. Both the La Guardia and Teterboro options now lead to crashes. Sully and Skiles are vindicated. Finally, we get a full-blown replay of the critical action in the cockpit, thanks to the Board’s playing of the flight-box recorder. We hear the pilots’ conversation while the film flashes back to show Sully and Skiles facing the crisis.

Thanks to editing, the 208 seconds from “Birds!” to safe landing gets expanded a little in this replay. (By my count, it runs about 330 seconds.) And we aren’t wholly confined to the cockpit visually, as we can trace the plane’s progress from outside. Basically, though, we’re attached to the two men, sometimes through optical POV shots. Although we saw the early phase of the pilots’ routine safety responses in the first long flashback, now we see the whole process, culminating in Sully’s decision to land on the Hudson.

What might have been a strenuous exercise in padding, replaying the crucial moment just to stretch the action out, becomes a strategic way to balance individual and collective effort. The first two long flashbacks stress the roles of the air-traffic controller, the crew, the passengers, and the first responders. In this respect the heroism is spread out, showing a collective effort to save the situation. Only at the climax does the film confirm what many witnesses have said from the start—that Sully deserves to be called a hero. The NTSB officials pay tribute to him as the x-factor, the crucial figure in the equation. But he demurs: “It was all of us.” The theme of group accomplishment is made tangible by the film’s play with plot structure and narration.

The replay flashback wasn’t unknown in silent film, and sound examples include The Canary Murder Case (1929) and The Witness Chair (1936). Nevertheless the replay becomes quite elaborate in the 1940s, with Mildred Pierce (1945) being a particularly intricate example. It’s clearly an idea circulating through the filmmaking community: Cukor wanted a replay for A Woman’s Face (1941) and Mankiewicz wanted one for All About Eve (1950). (He got one in the self-produced Barefoot Contessa, 1954.) An almost fussy example can be found in the British flashback film, The Woman in Question (1950). Since then, the replay has been a rich secondary resource for Hollywood. Its widespread revival, and repurposing, in modern cinema reminds me of a remark made by André Bazin.

Sometimes Bazin’s reference to “the genius of the system” is taken as praise for the Hollywood studio system as an economic enterprise. I don’t read it that way. I think he was referring to the fecundity of a particular storytelling tradition.

The American cinema is a classical art, but why not then admire in it what is most admirable, i.e. not only the talent of this or that filmmaker, but the genius of the system, the richness of its ever-vigorous tradition, and its fertility when it comes into contact with new elements.

Bazin gives as examples of such “new elements” the commentary on American society to be found in films like Bus Stop and The Seven Year Itch. In such films, “the social truth . . . is not offered as a goal that suffices in itself but is integrated into a style of cinematic narration.” Sully does much the same thing. Seizing on the bare incident of Captain Sullenberger’s landing and its reception by the public, the filmmakers have integrated it into a narrative pattern that is at once traditional and novel.

It’s this interplay of narrative convention and innovation I try to trace across a single period in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

The citation of Bazin comes from “On the politique des auteurs,” in Cahiers du cinéma: The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave, ed. Jim Hillier (Harvard University Press, 1985), 258.

I discuss network narratives in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 9-103, and more extensively, drawing examples from world cinema, in “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance,” in Poetics of Cinema, pp. 189-250. On this site, see this entry on Grand Hotel (1932), this one on Life without Principle (2011), this one on some examples from the 2000s, and another about Babel (2006). One from last winter compares network narratives to films with one or two protagonists. See also Peter Parshall’s book Altman and After (Scarecrow, 2012). Want to see a combination of network narrative and maniacal replays? That would be Vantage Point (2008), which I once intended to write about here before a trip to Asia deflected me. . . .

To-camera address in The Wolf of Wall Street is considered here. In another entry I discuss traces of the would-be replay in All About Eve. “Play It Again, Joan” considers purely auditory replays. To compare a replay with a film’s first iteration, you can check my analysis of Mildred Pierce and the video therein. I discuss a pseudo-replay in The Chase (1946); it’s weird, but that’s the Forties for you.

Other examples of modern assimilations of 1940s techniques are discussed in this entry on fragmentary flashbacks and this entry on Tarantino. And of course there’s the labyrinth of linkages we find in The Prestige. For other relevant entries, check the category 1940s Hollywood.

Jersey Boys.

In pursuit of THE CHASE

The Chase (1946).

DB here:

While writing my book on Forties Hollywood, I often felt that every movie I talked about was based on a bestseller, a Broadway play, or something by Cornell Woolrich. Many of the best, or at least strangest, films of the era come from his haunted imagination.

T he Chase (1946), long a cult film maudit, is for some aficionados the ultimate noir. It manages to be even more peculiar than its source novel, Woolrich’s The Black Path of Fear (1944). Although I began reading Woolrich as a teenager, I didn’t catch up with the film until the 2000s, in a so-so DVD. It has come to occupy a minor place of honor in the book (due out next fall, thanks for asking).

he Chase (1946), long a cult film maudit, is for some aficionados the ultimate noir. It manages to be even more peculiar than its source novel, Woolrich’s The Black Path of Fear (1944). Although I began reading Woolrich as a teenager, I didn’t catch up with the film until the 2000s, in a so-so DVD. It has come to occupy a minor place of honor in the book (due out next fall, thanks for asking).

Kino Lorber has recently released The Chase in a nicely cleaned-up DVD/Blu-ray edition. So all hail UCLA’s efforts restoring this neglected item, as well as its rescue of other worthy titles: Renoir’s The Southerner (1945, also from Kino Lorber), Too Late for Tears (1949), and Woman on the Run (1950), the last two from the estimable Flicker Alley. Kino Lorber has decorated the Chase release with commentary by Guy Maddin and recordings of two radio shows based on the Woolrich novel. (A pity we don’t have the Hedda Hopper radio show promoting the film, but maybe that’s lost.)

My book features The Chase because it poses with extreme prejudice the question of how far narrative innovation could go in the 1940s. Sometimes, as I’ve argued with The Great Moment and All about Eve, filmmakers go too far and get pulled back. But then readjustments necessary in postproduction may create twitches of novelty too. The Chase is another example of innovation by accident.

In the book, I mostly analyze the film. But I’ve also done a little digging into its production and promotion, as a way of explaining some of its captivating oddities. I came up with some information I haven’t seen discussed anywhere, so I thought I’d pass it along in a blog entry.

I haven’t located any scripts, alas, but our archive at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research holds other intriguing documents, including correspondence, a typescript synopsis, and a gorgeous presskit. Elsewhere I came across a document that gives clues about what the script and, at one stage, the film were like. There are reasons to think that an early version of the film was even stranger than the finished movie.

There must be spoilers, for both The Chase and The Woman in the Window (1944). Oddly enough, as we’ll see, contemporary reviewers of these movies didn’t worry about spoilers, so maybe I shouldn’t either.

Die in Havana, wake up in Miami

The Black Path of Fear begins in a fraught situation. Bill Scott enters a Havana club with an American woman. As they kiss, she is suddenly stabbed to death, and he’s the prime suspect. He escapes from police questioning and takes refuge in the tenement apartment of another woman, nicknamed Midnight. Scott recounts his backstory in a brief flashback, and then he sets out to find the people who have killed his woman and framed him. His effort takes him into the opium racket run by Eddie Roman from Miami. The bulk of the action takes place in Havana, with the flashback and a penultimate episode set in Miami.

The Chase shifts the book’s flashback material to its chronological place. The film begins with navy veteran Chuck Scott down on his luck. He finds a wallet belonging to crooked businessman Eddie Roman, returns it, and for his honesty is rewarded with the job of a chauffeur. He meets Eddie’s wife Lorna, and soon they are plotting to run away to Havana.

That’s when things get strange. On the night of the couple’s planned escape, Scott stretches out to read a newspaper. Fade out and up to Eddie, also stretched out, listening to a phonograph record–first in extreme long shot, then in mid-shot.

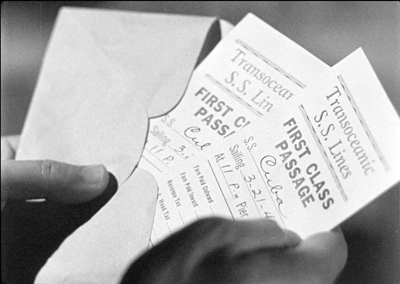

Eddie’s assistant Gino comes to Scott’s room and finds him gone. He reports to Eddie, showing the telltale travel folder.

As the recorded music continues, we are taken to a ship, where in a stateroom Scott is playing the same tune on a piano. Lorna is with him and they are evidently on their way to freedom.

Once the lovers are in Havana, The Chase follows the original novel, up to a point. Lorna is stabbed to death in the bar, Scott becomes the main suspect, and he flees the police by hiding in Midnight’s apartment. Soon Scott discovers that Gino is in Havana. He has arranged Lorna’s murder and the frame-up of Scott.

But now comes an astonishing twist, not in the novel. Gino finds Chuck hiding behind a curtain, shoots him, and dumps his body down a trap door. The body lies lifeless on the stair.

This is plotting in extremis. An hour into the film, both heroine and hero have evidently been killed and the unsavory characters have won. How to get out of this impasse? A telephone in the cellar rings. Cut to a ringing telephone on a desk, and track back. Chuck Scott is waking up, still on his bed with his newspaper.

He has dreamed the entire thirty-minute escape to Cuba, and we weren’t told he had fallen asleep.