Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

INDIGNATION: Novel into film, novelistic film

Indignation (2016).

DB here:

As I finish my book on 1940s Hollywood storytelling, I see that period’s influence all over the place. (Actually, that’s part of the book’s point.) One thing that filmmakers did back then, I think, is make cinema more “novelistic.” It’s not just that they took stories from novels, though they certainly did. They also made much greater use of storytelling devices that had become common in literature both high and low.

Many of these techniques I’ve talked about in other entries. There were, of course, flashbacks—not new to the Forties, but now much more frequent than in the Thirties. There was also the rise of voice-over commentary, like the narrating voice of fiction. It might be the voice of an objective narrator, as in Naked City (1947). Or it might be the voice of a character, either telling the tale to another character, or recalling events purely in his or her mind.

Other types of subjectivity came forward too, such as dreams, daydreams, and hallucinations. Filmmakers of the 1930s were inclined to tell their stories objectively, through concrete behavior. But thanks to imported and revised literary strategies, many Forties films gain a greater density and interiority. Compare, for example, the 1931 Waterloo Bridge with the 1940 one.

One thesis of my book is that filmmakers of the Forties consolidated these strategies in a way that became central to modern movie storytelling. That seemed to me to be confirmed when I saw James Schamus’s directorial debut, Indignation, now or soon playing at a theatre near you. Because of his skill as a screenwriter, I expected an intelligent adaptation of Philip Roth’s novel, but I also hoped to learn more about the expressive resources of contemporary cinema. I wasn’t disappointed.

Indignation’s core story involves Marcus Messner, studious son of a New Jersey butcher who goes off to a Midwestern college. Stuffed with ideas and ambitions, Marcus is intellectually worldly but socially and sexually naïve. If he weren’t in college, he’d be drafted to fight in the Korean War. Instead of fitting smoothly into academic life, he finds himself confused by Olivia Hutton’s calculated sexuality. In addition he struggles with an overprotective father and the puritanical, hamfistedly Christian, regimen of 1951 campus life.

To talk about what I find exciting and instructive in the film, I have to presume you’ve seen it. So what follows is filled with spoilers.

Sticking to one causal line

Like the book, the film is an exercise in restricted point of view. That involves not simply the voice-over commentary that weaves in and out. (In a film, that technique doesn’t guarantee restriction the way first-person narration would in a novel. Movies can be more promiscuous in breaking with what one character thinks and knows.) And the restriction isn’t wholly a matter of a subjective plunge either, though we do get Marcus’s dreams and fantasies and some fragmentary flashbacks.

No, what makes Indignation intriguingly “novelistic” is a matter of attachment. We’re simply with Marcus through almost the entirety of the movie. We know only as much as he knows. This means that we learn about certain things when he does. His father’s breakdown back home is conveyed through phone calls. At the climax, his mother’s visit to him in the hospital reveals that she’s considering divorce. An alternative narrative strategy would be to shift from scenes with Marcus to scenes elsewhere, say back home in New Jersey or in Olivia’s dorm. This “omniscient” option is more common throughout American film history; we see it in the crosscutting between CIA malefactors and poor David Webb in Jason Bourne.

Restricted narration isn’t the only way to generate mystery, but it’s a reliable one. By attaching us to Marcus’ range of knowledge, Indignation creates mysteries, chiefly around Olivia. What has made her behave as she does? She never offers a full explanation, but in some scenes she tells more about her parents and in a crucial confession she confesses her alcoholism, a suicide attempt, and a period in treatment.

During this confession, Schamus finesses the showing/ telling problem in an intriguing way. There are good reasons, I’ve suggested before, to let such monologues play out in the space and time of the scene. Telling is sometimes more vivid than showing. But Schamus has chosen to show as well as tell, by providing quick flashback illustrations of what Olivia recounts to Marcus.

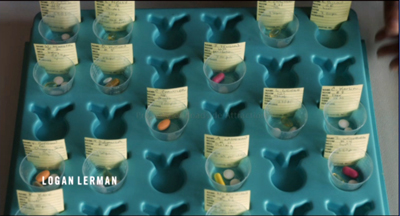

What interests me is that these images from the past have an in-between status. They’re neither straightforward and neutral, nor Olivia’s own viewpoint, nor exactly Marcus’s imagined version of what she’s telling him. For instance, the straight-down, somewhat diagrammatic and clinical framing of some of them calls to mind the film’s first shot, also associated with Olivia’s health: the pill case in the care facility.

Likewise, the shot of Olivia in a straitjacket, framed off-center in a way few other isolated long shots in the film are, has an abstract quality that suggests an image lying somewhere between her memory and Marcus’s imagining of her situation—without making it wholly subjective. (In the early 1950s, it’s plausible she was indeed treated this way.)

At the climax, we get even less information about Olivia’s situation. Before Marcus can break off with her, she simply vanishes. Marcus will never find out what became of her. For him, if not for us, the mystery is permanent.

Not that he doesn’t try to communicate. This is one role of the voice-over in which he muses on his past and, more ambitiously, on the role of cause and effect in life. As a follower of Bertrand Russell, he’s evidently pondering Russell’s idea of “causal lines.” Ironically, though, Russell’s inferential model of causality doesn’t help Marcus figure out what happened to Olivia.

But from where is Marcus speaking? Quite likely, from the Afterlife.

Dead narrators drift through 1940s cinema. Philip Roth was ten when The Human Comedy (1943) featured a deceased father returning to his small-town family, and eleven when The Seventh Cross (1944) gave us an executed prison-camp escapee who shadows one of his mates. So Indignation, set in the year after Sunset Boulevard (1950), seems perfectly in keeping with this trend. But these other films announce the voice-over’s posthumous status right away. Schamus does something a bit different.

In the source novel, Roth lets Marcus suggest that he’s dead about a quarter of the way through. Schamus’s screenplay drops hints that are, I think, fully noticeable only in retrospect. He creates a surprise that in turn motivates one of the two frames that surround the 1951 story action.

The front end of the inner frame is a brief combat skirmish in South Korea. A GI is pursued into a dark, nondescript building by a North Korean soldier. The action is difficult to discern, but we can see that the Korean is shot. Did the GI escape? The combat scene will be partially replayed near the film’s end, closing the frame the first one opened. The GI will be revealed as Marcus, who is dying from a bayonet thrust.

This isn’t merely a trick. In the 1940s filmmakers realized that some stories, if told chronologically, begin in rather slow and uninvolving fashion. But starting at a crisis late in the story’s causal chain, and then flashing back to what led up to it, can arrest our attention. Think of what The Big Clock (1948) would be like if we started not with the hero dodging around corridors trying to elude the police, but with his mundane office routine earlier that morning. So instead of starting with Greenberg’s funeral, Indignation grabs us with a brief and enigmatic piece of life-or-death action.

1940s frames are more explicit about the framing situation than the combat incident in Indignation. Yet Schamus evidently didn’t want to show Marcus lying there dying and reflecting on his life and leading into the film as a whole: too on-the-nose, and perhaps too obviously fatalistic. The shift to the Jonah Greenberg funeral frees the story action from what Henry James once called “weak specificity.”

There’s also the possibility that Marcus survives; we don’t see him die, even in the finale of the skirmish. The fact that the film can equivocate about whether our narrator is alive or dead emerges as a fresh treatment of the Afterlifer convention.

By raising the possibility of a dead narrator early on, Roth may make us view Marcus’s actions with more detachment, sub specie aeternitatis. The film version, I think, gets us more emotionally invested in Marcus, and this makes the eventual possibility (for me, the likelihood) that he has died more wrenching.

More than Marcus

Even in the enframed 1951 story action, our attachment to Marcus’s range of knowledge isn’t complete. For one thing, there are ellipses—most notably, the crucial scene in which he asks Olivia on their first date. There are also moments in which we run ahead of his awareness. When his mother meets Olivia, Schamus has controlled his actors’ eyelines so that even in a two-shot we’re not looking at the hero but rather at Mrs. Messner, who spots the girl’s wrist scar.

This is sharp visual storytelling. Marcus is unaware of his mother’s observation, but we’re prepared for her later admonition that he’s getting involved with a woman who will bring him misery. (Marcus: “She slit one wrist.” Mrs. M.: “One is enough. We have only two, and one is too much.”)

We’re also a beat ahead of Marcus in one neat shot that shows him stepping onto the quad as he’s facing expulsion. We see his future before he does; the marching ROTC students in the background catch our notice before a rack-focus brings him up to speed.

We’re also invited to see parallels that pry us a bit away from Marcus’s immediate experience. At two crucial moments, the adults trying to intimidate him—Dean Caudwell and his mother—come around behind him to keep wheedling.

The know-it-all debater has a chance when fighting face to face, but he crumbles when authority steers from behind.

Above all, our attachment to Marcus is qualified by a second frame, the one that wraps the whole fiction. This is wholly Schamus’s invention—a nested structure of the sort characteristic of 1940s films. At the very beginning and end of Indignation, we see an elderly Olivia in a care facility staring at the wallpaper dotted with a pattern of flowers in a water carafe. The image (also on a skirt she wears in the college portion) harks back to her impromptu bouquet for Marcus in the hospital.

But of course we’re inclined to ask: How likely is it that such a pattern would be used on wallpaper, and would it so neatly coincide with an item in Olivia’s past? We could then ask whether the pattern is in her imagination. (There is a sort of blurring and refocusing on the pattern, suggesting her optical viewpoint.) And since her scenes in the facility bookend the entire film—the Korean War frame, which in turn encloses the Winesburg College days—we might ask whether everything we’ve seen isn’t a product of her fantasy.

I’m not inclined to say that she has made up the whole movie. Indeed, if the wallpaper pattern is her projection, it would have to be so not just in her optical POV but also in the wider shot of her, the first image we get of her as an old woman.

Maybe this room, Caligari-like, is a total projection of her memory? More likely, it’s objectively there but triggers her recollection of Marcus. I’m still uncertain, but it does seem that giving Olivia the ultimate framing for the tale via their shared moment with the flowers suggests that Marcus, who at the end of his last monologue is calling out to her, has somehow finally made contact.

In any event, a purely formal cadence, completing the ABCBA structure and revisiting an ambivalent motif in the film, can balance, in aesthetic terms, the absence of answers to questions posed in the story world. This appeal to geometrical architecture and symmetrical construction is, since Henry James, another novelistic convention: art’s order can frame, if not completely account for, the disorder of life as it’s lived.

Goliath wins

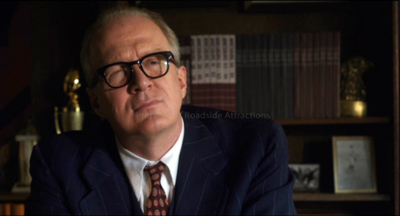

The sequence that has everybody talking is the sixteen-minute two-hander between Marcus and Dean Caudwell. It’s in the book, but Schamus and his players have brought to life the clash between idealism and suave, well-practiced bullying.

Straddling the film’s midpoint, this scene enacts the old proverb. “Old age and treachery trumps youth and skill.” It starts with a simple bureaucratic issue: Marcus’s transfer out of the dorm to a shabby, solitary room. This incident leads Dean Caudwell to charge him with stubbornness, lack of compromise, secrecy about his Jewish identity, friction with his family, intellectual arrogance, and cowardice. The whole cascade is punctuated by the Dean’s intermittent requests to stop calling him “sir.” It’s a verbal boxing match with Marcus gamely fighting on after quite a few low blows. Nobody who read Why I Am Not a Christian in their youth (as I did) can fail to be roused to self-righteous fury by Caudwell’s calm, close-minded innuendo.

Still, in such duels dialogue and performance need to be orchestrated with framing and cutting. Steve McQueen’s solution in Hunger (2008) is the use of a sixteen-minute profile long-shot, followed by a cut in to Bobby Sands’ hand picking up his cigarettes, and then a very tight close-up of his face as he continues speaking.

The interruption of the long take gives special prominence to a shift in the conversation, when Sands recalls his childhood. Later shots revert to shorter shot/ reverse-shot exchanges.

So framing and cutting can articulate phases of the drama. This Schamus does very carefully in the Indignation scene. To abbreviate:

Phase 1: More or less businesslike and polite: Why couldn’t Marcus compromise with his roommate? 180-degree cuts, with framing favoring Dean Caudwell–centered and dominating Marcus.

Phase 2: Caudwell gets personal. Why didn’t Marcus identify his father as a kosher butcher? Eventually he’ll accuse Marcus of intolerance. Here a fairly lengthy profile shot reminiscent of Hunger gives way to shot/ reverse-shot.

Phase 3: More personal probing: How does Marcus get along with his family? What about his sex life? And religion? After more shot/reverse shot, Marcus, sweating and feeling sick, rises to defend himself in close-up. That calls forth the closest shot yet of Caudwell.

Phase 5: Caudwell says Marcus’ sophistry will make him a fine lawyer. He comes to stand behind Marcus, putting his hands on his shoulders. Then he sits beside him, to drill in still more. Marcus, shaky, asks to leave.

Phase 6: At the door: Marcus is feeling sick. The dean asks if he’d like to play baseball. Finally Markus collapses and starts vomiting.

Schamus has saved shot/ reverse shot for when the scene heats up, and saved his close-ups for when things reach a pitch. This reminds us, as the Hunger scene does, that if you’re going to use a standard technique, hold off until it will do the most good. Ditto for the low angle on Marcus throwing up; that comes with more force if we haven’t already had low angles before. Schamus has let his cutting and shot scales amp up the drama without the crushing emphasis supplied by so many directors. Yes, I’m thinking of the barrage of close-ups in every dialogue scene of Jason Bourne. (Thanks to Paul Greengrass, Tommy Lee Jones’s facial contours qualify for Federal Drought Relief funds.)

I think that Indignation will be studied for years as an intelligent adaptation of Roth’s novel, but it ought also to be admired as a well-crafted work in its own right. It finds fresh ways of molding fiction techniques to the demands of cinema in general and Hollywood tradition in particular. And the film reminds us—or me, at least—how much contemporary filmmaking owes to the consolidation of “novelistic cinema” seventy years ago.

Thanks to James Schamus, Gustavo Rosa, and Lauren Hynnek for information and assistance, . For more on James’s career, see our entry.

Students of literature might find another novelistic analogy in Olivia’s explanation of her suicide attempt. It somewhat resembles the technique of free indirect discourse, when the third-person authorial voice adopts the language and syntax of the character’s thought. Roth employs this in the third-person tailpiece of his novel. Instead of “If only I hadn’t let Cottler hire Ziegler to proxy for me at chapel!” we get “If only he hadn’t let Cottler hire Ziegler to proxy for him at chapel!” Is it possible to have a cinematic equivalent: an objective vision that is pervaded by the character’s state of mind? Pasolini thought so, and suggested Red Desert, Before the Revolution, and Godard’s films as examples of it. Perhaps this flashback sequence counts as a case of Pasolini’s “free indirect subjective.”

In The Way Hollywood Tells It I briefly discuss the resurgence of 1940s storytelling strategies in recent studio cinema (pp. 72, 83). A general discussion of my interest in 1940s narrative is here. Elsewhere I make the case for Tarantino reviving 40s formats; for the importance of Afterlifers in the Forties; for nested narratives like that of Indignation; for replays that provide new information; and for the blurring of subjective and objective in Nightmare Alley.

For more on novelistic strategies in film, see “Watching a movie, page by page” and Kristin’s entries on the Hobbit films, all linked here.

Indignation.

Born on the 23rd of July

The Wisconsin State Journal, Wednesday 23 July 1947.

DB here:

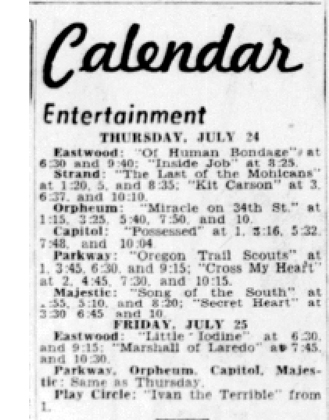

Today I turn 69. (Please keep the cheers discreet.) I was born in western New York State, but I’ve spent over forty years in Madison, Wisconsin. So for fun I thought I’d take a look at what you could have seen on 23 July 1947 in my current home town.

This isn’t (just) an exercise in baby-boomer self-regard. Looking at the movie ads in the Wisconsin State Journal for that fateful day can remind us of interesting stuff about American cinema of the postwar years. Or so I think, fueled by work on Hollywood in the 40s for a book I’m nearly done with.

Classics, just passing through

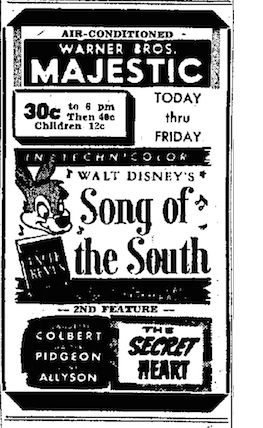

Song of the South (1946).

The first thing that strikes me the quality that’s on offer. On that Wednesday you could have seen four superb films (Rebecca, Stairway to Heaven, Song of the South, Possessed) and two worthwhile pictures (Of Human Bondage and Miracle on 34th Street). These movies are still remembered and admired.

Can this morning’s list of multiplex showtimes promise anything so enduring? Maybe Finding Dory and The BFG will be watched sixty-nine years from now, but our other current releases seem bound for oblivion. And of course the 1947 bill of fare was, with the important exception of Song of the South, designed for grownups.

Those who want to use this 1947 data-point as an example of the death of American cinema are welcome to do so.

Admittedly, today we don’t expect summer to generate the highest-quality films. (Though it often does; think of the last Mad Max installment. And James Schamus’s Indignation is coming up next week.) In 1947 the summer market was rather different from that today. Studios planned their major releases from late August onward, with big pictures playing through fall, winter, and early spring. June, July, and much of August were a slack stretch, when, Hollywood charmingly assumed, people wanted to be outside. So summer releases tended to be minor titles, and exhibitors turned to foreign fare, B pictures, and reissues.

Still, Possessed and Miracle were brand-new releases. At the end of the 40s, it seems clear, studios began releasing more of their important pictures in the summer. And as you can see, air conditioning–rare then, even in public buildings–lured some folks in.

In any case, for moviegoing purposes, I’d rather have been in Madison in July of 1947. In the two weeks sandwiching my birthday (16 July-30 July), I could have seen Brief Encounter, Her Sister’s Secret, Tomorrow Is Forever, Tender Comrade, The Sea Hawk, The Sea Wolf, Dead Reckoning, The Hucksters, The Unfaithful, The Lady in the Lake, Bohemian Girl, Boom Town, The Razor’s Edge, Love Laughs at Andy Hardy, Mr. District Attorney, Calcutta, I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now, Angel and the Badman, The Dark Mirror, Till the Clouds Roll By, Pursued, and Sister Kenny—along with a couple Lone Wolf and Falcon movies. Not a bad lineup. And I’m not counting La Grande Illusion and Ivan the Terrible on the UW campus.

Safety in numbers

Possessed (1947).

Then there’s quantity. Madison, Wisconsin had a population of about 65,000 in the year of my birth. It was dwarfed by Milwaukee, which had nearly ten times that. Yet by my count, over the two weeks around my birthday, a Madison moviegoer had 73 films to choose from. For the same 15-day stretch in town today, I come up with no more than 20. (For both time frames, I’m not counting campus or library screenings.)

My biggest choice today involves where, when, and how to watch. The Secret Life of Pets is playing on nine screens, and I can see it in 3D or flat versions. I can see it at 8 AM or 8:20 or 8:35, and so on to 11:30 PM. The showtimes are user-friendly. By contrast, Madison movies in 1947 were appointment viewing, and most titles played only two or three times a day. While you could just drop in at any point, the newspaper did publish show times, so you could plan to watch the movie straight through if you wanted.

My biggest choice today involves where, when, and how to watch. The Secret Life of Pets is playing on nine screens, and I can see it in 3D or flat versions. I can see it at 8 AM or 8:20 or 8:35, and so on to 11:30 PM. The showtimes are user-friendly. By contrast, Madison movies in 1947 were appointment viewing, and most titles played only two or three times a day. While you could just drop in at any point, the newspaper did publish show times, so you could plan to watch the movie straight through if you wanted.

Of course my 69-year-old self has a much bigger choice of movies than what’s in theatres. I can choose among thousands of titles on cable TV, disc, or streaming. TV wasn’t a significant part of the American landscape in 1947. Cinema existed in an economy of scarcity rather than overabundance.

This circumstance led people to go immediately to see the newest picture, as they couldn’t be sure it would return in second-run or a reissue. Today many of us skip a new release in theatres because we know we can catch it in a later video window. Does this all-you-can-eat plenitude make cinema seem less urgent and immediate—more a matter of “content” filling libraries and bookshelves and hard drives and Netflix queues? I think so. We’re all collectors now, in a way a 1947 moviegoer couldn’t be, but that means we lack the impulsion to see most films immediately. It takes effort to go out to see a film, but maybe that effort makes the experience more valuable (when the movie is satisfying, of course).

Dueling duals

Oregon Trail Scouts (1947).

The ads reveal more about quantity. You’ll have noticed that a great many of the films are playing on double bills (“duals”). From the 1930s on there was a perpetual debate about whether duals helped or hurt the industry. Most studio chiefs deplored them and confidently announced that a majority of audiences didn’t like them. The trade papers regularly ran stories predicting that the dual’s days were numbered.

They were wrong. Duals persisted into my college years; to see Help! (1965) twice in first release without buying another ticket, I had to sit through The Glory Guys (1965). Most exhibitors were independent of the studios, and they liked duals. So, obviously, did many viewers, who enjoyed getting two movies for the price of one.

Several industrial factors are connected here. The two Madison theatres running single features were the main picture palaces. The Capitol and the Orpheum each had about 2200 seats. They were the prime first-run houses, affiliated with two studios: the Warners chain controlled the Capitol, and Twentieth Century-Fox controlled the Orpheum. No surprise then that the former ran Possessed (a Warners picture) and the Orpheum ran Miracle on 34th Street (a Fox release). So these houses could run the premiere engagement of each film, counting on the freshness of the release to attract customers. These venues screened their first-run single features for a full week.

Several industrial factors are connected here. The two Madison theatres running single features were the main picture palaces. The Capitol and the Orpheum each had about 2200 seats. They were the prime first-run houses, affiliated with two studios: the Warners chain controlled the Capitol, and Twentieth Century-Fox controlled the Orpheum. No surprise then that the former ran Possessed (a Warners picture) and the Orpheum ran Miracle on 34th Street (a Fox release). So these houses could run the premiere engagement of each film, counting on the freshness of the release to attract customers. These venues screened their first-run single features for a full week.

The other theatres in the ad are running duals. Some of them ran recent releases, but late in the run. For instance, the Parkway (despite its name, another downtown theatre) was a big venue, with a 1200-seat capacity. On my birthday it screened Cross My Heart (a January ’47 release) and Oregon Trail Scouts (a May release). These were first-run, but with less must-see appeal than Miracle and Possessed. Also, Oregon Trail Scouts is a prototypical B picture, running 58 minutes. So the Parkway, another Fox-controlled screen, mated a mildly attractive Paramount programmer or “nervous A” with a Republic B. A third Fox venue, the Strand, a 1300-seater on the square, drew on second-run titles and reissues for its duals.

The town’s smaller theatres relied on duals. The Majestic, an old vaudeville house with some of the most skewed sightlines in Christendom, was at that point another Warners house. Yet it had no qualms about showing subsequent-run titles from Disney/RKO (Song of the South, in its third Madison run) and MGM (The Secret Heart, back for a second).

The Madison was yet another Fox house; on my birthday it was showing two Universal releases: Stairway to Heaven (the US title of A Matter of Life and Death), paired with the unlikely partner The Vigilante Returns, a B. Both were first-run in Madison.

The Madison was yet another Fox house; on my birthday it was showing two Universal releases: Stairway to Heaven (the US title of A Matter of Life and Death), paired with the unlikely partner The Vigilante Returns, a B. Both were first-run in Madison.

As a result, in my one-day snapshot every major Hollywood studio is represented; even RKO gets in with its “Passport to Nowhere” short. How can this be, in a town with four Fox screens, two Warners screens, and only one independent exhibitor? Research by our colleague Andrea Comiskey has shown a remarkable flexibility in studio screening policies. Often a subsequent-run house owned by a studio played few or none of the studio’s own releases. This way everybody could make money off everybody else’s movies. Such are the ways of oligopolies.

Why so many B’s, particularly Westerns? Given double bills, they were what the trade papers openly called fodder, and they saved money. B’s were rented on a flat-fee basis, while A’s were rented on a percentage basis. Some exhibitors ran the B more frequently than the A each day, so as to keep more of the box-office take. Such wasn’t the case with the Madison, though: Both Stairway and Vigilante played an equal number of times each day.

Was the B the chaser, clearing the house after the A? Maybe, but maybe someone coming to see a prestigious Powell and Pressburger would stick around for Jon Hall and Andy Devine. In any case, since the Big Five studios were making fewer pictures in the 1940s and were concentrating on A items (the big-ticket income), the ongoing demand for duals helped less important studios, which were heavy suppliers of B’s.

There was only one independent house in Madison proper. The Eastwood (still standing, now a live venue and called the Barrymore) was playing second-runs in its 950-seat auditorium.

Finally, runs were tied to ticket price. I haven’t got good information on ticket costs in these theatres, but the fact that the Majestic boasts of charging $.30 until 6 PM, and then bumps the cost to $.40, is typical of a second-run house of the time. First-run tickets, depending on time of day, could be $.50 or more.

Those costs, by the way, translate to ticket prices between $3.30 and $5.50 in today’s currency. Another data point favoring the good old days.

Heavy rotation

The Middleton Theatre, Middleton Wisconsin, in the 1970s. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society.

Duals multiplied the number of pictures on offer. So did the length, or rather the brevity, of runs.

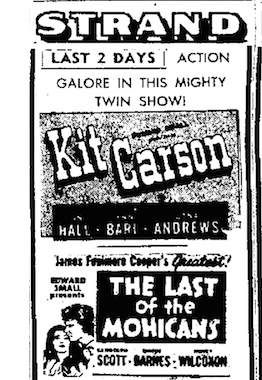

The first-run A’s, Possessed and Miracle on 34th Street, ran a week; Miracle, in fact, was moved over to the Madison at the end of July for a longer stay. But most duals changed more frequently. The Madison’s dual of Tomorrow Is Forever and Tender Comrade ran five days, as did the Strand’s Last of the Mohicans and Kit Carson. But the Parkway typically changed bills every three days, while other theatres split up the week even more. Some programs ran only two days.

We’re so used to pictures hanging on for weeks or months that these rapid playoffs are surprising. But here my birthday snapshot is a bit misleading. Many of the films brought in for two or three days were second-run titles, and a surprising number were reissues.

Eric Hoyt, another Madison colleague, points out in his splendid book Hollywood Vault that the Forties was a great era of reissues. Re-releasing 1930s classics like King Kong and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs proved that an older picture might make as much or more than a new one. In any case, reissues could be cheaper for theatres to rent, especially in the slower summer months, and they could be turned over quickly.

Eric Hoyt, another Madison colleague, points out in his splendid book Hollywood Vault that the Forties was a great era of reissues. Re-releasing 1930s classics like King Kong and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs proved that an older picture might make as much or more than a new one. In any case, reissues could be cheaper for theatres to rent, especially in the slower summer months, and they could be turned over quickly.

The number of reissues increased powerfully just before my birthday. In late May, the Hollywood Reporter claimed that of 224 pictures playing in metropolitan New York, 105 were “oldies.” Just after said birthday, HR reported that “the highly satisfactory boxoffice results from reissues in recent months, plus the necessity of averaging down the cost of new productions which continue to call for multi-million dollar budgets, will result in nearly twice as many reissues in 1947-48 as in the past year.” That number was said to be 75 from the Majors, along with another 100 or so titles already sold or leased by non-Majors.

The oldest reissue on offer in Mad City on my birthday was The Last of the Mohicans (1936), paired with Kit Carson (1940). This package had already had great success in New York and had helped sustain the reissue boom. So strong was this Mighty Twin Show that producer Edward S. Small could demand not the usual flat-rate terms but rather a 35% of the box office. In Madison during the weeks around 23 July, you could have seen a great many other films from the 1930s and 1940s, on brief-stay duals.

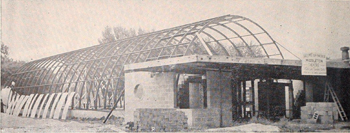

Speaking of reissues, the Middleton, the venue announcing Rebecca in the ad, is interesting in its own right. Middleton is a pretty bedroom community west of Madison, then with about 2000 souls. Now, thanks to infill, it’s more or less a continuation of our town. Its theatre, an independent house built in 1946 and with a capacity of 500, ran both second-run and reissues, including, during the DB magic weeks, Sun Valley Serenade (1941), The Westerner (1940), and, for one day, Once Upon a Honeymoon (1942).

Maybe more interesting is that the Middleton was a Quonset hut, with a wraparound roof.

More about the Middleton here. Kristin and I saw E. T. there, and I wish we’d gone more often. It was demolished in 1992.

Foreign accents

A Matter of Life and Death (aka Stairway to Heaven, 1946).

The presence of Stairway to Heaven (in first run) points up another trend. During the 1940s, foreign films gained a new prominence on American screens. While reissues were flooding New York City screens as noted, the number of imports among them was sharply up: fourteen British titles, five French, four Spanish, three Italian, two Russian, and one Swedish.

Those proportions reflect the growing popularity of British cinema. At year’s end, Variety noted that the number of British releases in 1947 doubled from the previous year, from ten to twenty. In the two weeks surrounding my birthday, Madisonians could have seen Brief Encounter, also at the Madison. The Madison seems to have sometimes operated as an art house. It screened Open City a month earlier, promoted in a memorable ad that somehow plays up sexytime without showing Anna Magnani.

Note what’s playing with it. The Madison stayed classy.

1946 was the high-water mark of American movie attendance and Hollywood studio profits. 4.7 billion US tickets were sold, and profits came to nearly $120 million. Attendance remained strong in 1947, but profits started to fall steeply, to about $87 million. The soaring costs of production, including millions spent on rights to projects that were never filmed, came due. And soon enough attendance dropped calamitously as well. Ticket sales in 1952 were only a bit more than half of 1946’s total. A great many Americans stopped going to the movies.

There were rumblings, though, before I showed up. “Boxoffice of Nation on Skids,” announced the headline of Hollywood Reporter for 20 May 1947. Was this just a “spring slump,” such as those before World War II, when good weather drove people outside? “If there is no general rise in grosses by the middle of July,” said one executive, “then our fears will have been realized, as it will reflect an economic crisis.” Studio employment was off 20%; the Majors’ building plans were put on hold; and reissues from non-Major sources were gaining a bigger share of the receipts. Ultimately, 1947 fell off only a little, but film folk were nervous. The big dip would come soon.

Another crisis: In less than a year after my birthday the Supreme Court would declare that the studios’ ownership of theatres was monopolistic, and the companies would begin gradually splitting off their theatre chains.

I was born, then, on a sort of cusp. By the time I was 5, people were declaring the studio system dead. Knowing nothing of this, I continued watching new releases (Peter Pan, Francis the Talking Mule movies) and old films that were starting to show up on TV. I didn’t suspect that, decades along, I would spend my more-or-less adult life studying those movies that played the Capitol, the Parkway, and the Middleton. Just looking at this page from the State Journal has me hoping that Kristin gets me a time machine for my next birthday.

For help in preparing this entry, thanks to Lea Jacobs, Jeff Smith, Mary Huelsbeck, Amy Sloper, Lisa Marine, and Rob Thomas.

Some sources: “Double-Bill Reissue Packages Prove Surprising B.O. on B’way,” Variety (9 April 1947), 7, 18; “Re-Issues Flood New York Screens,” Hollywood Reporter (22 May 1947), 1, 3; “Reissues Doubled for 1947-48,” HR (26 August 1947), 1, 11;”Industry Schedules 130 Re-Releases for This Year,” HR (5 February 1948), 1, 13; “Boxoffice of Nation on Skids,” HR (20 May 1947), 1, 12; “Industry in Crucial Period before Upturn, Say Toppers,” HR (26 May 1947), 1, 12; “July Will Disclose Actual Extent of Boxoffice Downturn,” HR (9 June 1947), 10; “8 Majors and 4 Lesser Distribs Released 428 in ’47 vs. 405 in ’46,” Variety (31 December 1947), 6. Chapter 6 of Susan Ohmer’s book George Gallup in Hollywood (Columbia University Press, 2006) provides an excellent overview of the disputes about double bills.

There was another crisis in my late prenatal phase. In response to shopkeepers, the ever-watchful Wisconsin state legislature had drafted a bill banning candy, food, and drink from being sold in movie houses. Exhibitors mobilized and lobbied for tasty snack treats. “With boxoffice grosses rapidly slipping from their wartime peaks to pre-war levels, the candy, popcorn, sandwich and soft drink sales now are especially essential to keep the houses on the profit side of the ledger.” “Wisconsin Candy Sale Ban Doomed,” HR (7 May 1947), 5. Fortunately for all Cheeseheads, this bill was defeated.

Browsing the wonderful site Cinema Treasures can make you aware of all those lost movie houses. The Wisconsin Historical Society presents many photos of Madison’s old theatres. My photo of the Middleton in the 70s comes from this collection, Reference no. 5572.

The saga of Madison’s Orpheum is told in part here, though an update on all the intrigue is probably in order. At least the magnificent sign has been redone and has gone up. The Capital Times covers the process here and here. The refurbished sign got lit up last night. For more on local theatres, including the ones I actually frequented back East, go here and here. Also relevant is this visit to Rochester’s Cinema Theatre, with information from Andrea Comiskey. Also a cat.

On the importing of movies from overseas at this period, the definitive source is Tino Balio’s book The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2010).

P.S. 30 July 2016: The Middleton Theatre stirs fond memories. See Nadine Goff’s Facebook page on historic Wisconsin photographs for reminiscences of sticky floors and rain on the roof.

Another fateful birthday headline.

Rethinking the character arc: A guest post by Rory Kelly

The Apartment (1960).

DB here:

Rory Kelly, whom I met some years ago at a conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, has been a pioneer in linking the practices of film production to larger issues of narrative, performance, and artistic form. What follows is a version of a superb paper he gave at the Society’s annual meeting in Ithaca in June. Since Kristin and I are always eager to know how practitioners think of their craft, we jumped at the chance to pass along his thoughts in one of our guest blog entries.

Rory comes fully prepared to the task. Currently an Assistant Professor in the Production/Directing Program at UCLA, he has been a bright light in filmmaking for many years. His first feature, Sleep with Me (1994) premiered as an Official Selection at Cannes and was released by MGM/UA. His second feature, Some Girl (1998), garnered him the DGA-sponsored Best Director Award at the Los Angeles Film Festival, and his 2006 short, The Women, premiered at the Long Island Film Festival. He was also co-executive producer of mtvU’s Sucks Less with Kevin Smith. Rory has been a Film Independent Screenwriting Fellow and is currently working on several research projects, including studies of discourse analysis and emotional expression in film. At the same time, thanks to a 2016-2017 Heillman Fellowship, he is preparing a feature documentary about racism in America, To Someday Understand.

Here’s Rory on a perennial problem of the screenwriter: the character arc.

Since the 1960s, the character arc has become all but obligatory in Hollywood movies. Genres like sci-fi and horror, once largely unconcerned with character change, now often include it. Compare, for example, the 1953 version of War of the Worlds with Steven Spielberg’s 2005 remake. In the latter the alien invaders are not only defeated, but in the process Tom Cruise’s character, Ray Ferrier, becomes a better father.

Why has character change become so prominent? In The Way Hollywood Tells It (2006), David offered some suggestions. The psychological probing in plays by Arthur Miller, Paddy Chayefsky, and Tennessee Williams became popular models of serious drama. Teachers and writers were persuaded by Lajos Egri’s book, The Art of Dramatic Writing (1946), in which the author advises that characters should grow over the course of a play. There was also the impact of self-actualization movements of the 1960s and 1970s that held out the promise of personal growth and transformation.

It’s also likely that star power has had considerable influence. When trying to raise financing for a low-budget indie script a few years back, my collaborator and I were advised by three different seasoned producers to give our protagonist a more pronounced arc or we would never be able to attract a name actress to the role. Whether they were right or not, I do not know, but their shared assumption about attracting talent is telling.

Given how common the character arc has become, we need to better understand how it is typically handled. I think we can identify and analyze six narrative strategies that create a particular character type: the protagonist who is flawed but is capable of positive psychological change. My primary example will be The Apartment (1960).

I’ll also consider aspects of character change in Casablanca (1942), Jaws (1975), and About a Boy (2002). This list will allow me to consider the character arc over six decades, from the studio era to contemporary Hollywood, and across several genres. Limited as it is, this set of films suggests that certain techniques of character change recur again and again. In tracing them, I’ll occasionally make reference to the four-part plot pattern Kristin has set out in Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999) and several entries on this site: the Setup, the Complicating Action, the Development, and the Climax.

A six-step program

Casablanca (1942).

First, a filmmaker seeking to construct a character arc will almost inevitably begin by establishing that his or her protagonist is of (1) Two Minds. I mean by this that the character has competing impulses. Think of Rick in Casablanca. On the one hand he is inclined towards communal action; on the other hand he sticks his neck out for no one. This latter behavior is solidified during the Setup portion when he assists in Ugarte’s arrest.

It can be termed Rick’s (2) Negative Behavior Pattern. It is a pattern because it is a type of behavior Rick enacts again and again, as when he repeatedly refuses to give the letters of transit to Victor and Ilsa. The film even turns Rick’s selfishness into a motif.

Still, Rick retains an impulse towards virtuous behavior, his (3) Positive Behavior Pattern. During the Setup, for example, he does not allow a notorious Nazi to gamble in his café. Later he helps a destitute young couple earn passage to America by allowing them to win at roulette.

The film as well makes a motif of Rick’s virtuous side.

The ongoing interaction of these two behavior patterns allows the filmmakers to maintain audience sympathy for Rick, to motivate his final change of heart—if Rick were not of two minds, his final transformation would come out of nowhere—and to delay that change of heart long enough to create expectations and suspense.

What often postpones a protagonist’s change of heart is a (4) False Belief. In many films a misunderstanding is introduced that motivates the protagonist’s negative behavior pattern. Because of this the character need only discover the truth in order to be reborn. Think again of Rick. It is because he falsely believes that Ilsa once jilted him, leaving him alone in the rain at a train station in Paris, that he has become a sullen saloonkeeper who sticks his neck out for no one.

But once Rick learns the truth—that Ilsa left him because she discovered her husband was alive—Rick forgives her. He then devises a scheme to help her and Victor escape, and he makes plans to join the Resistance. The truth, in short, sets Rick free and quickly and efficiently allows for his change of heart.

Another way to look at Rick’s transformation is that his false belief about Ilsa has made him essentially a nihilist who believes that there is nothing worth living for. When Victor says, “If we stop fighting our enemies, the world will die,” Rick replies, “What of it? Then it’ll be out of its misery.” Seen from this angle, when Ilsa finally convinces Rick of the truth, we are meant to infer that his change of heart is the result of a realization that love and loyalty still exist in the world.

The final two strategies I want to discuss concern the story world. In the case of flawed protagonists the rules and values of the fictional world may be established as conflicted in a way that matches the protagonist’s competing impulses. On the one hand there is what I term the (5) Normal World. This constitutes the dominant rules and values in play as the movie begins. Against this there is what I term the (6) Possible World. This constitutes what the normal world should be.

Think once more of Casablanca. That city is established as a place where a great many people have abandoned their better impulses and are out only for themselves. The primary representative of this worldview is the charming but corrupt Captain Renault. However, the story world also includes Victor and other members of the Resistance, and they are believers in a new world; one based upon a common cause. So the story world is, like Rick, flawed but of two minds.

Rick occupies a psychological space between Renault and Victor. In the end, by siding with Victor, Rick not only abandons his negative behavior pattern, he also begins the process of overturning the rules of the normal world. The change is suggested by Renault’s becoming, as it were, Rick’s first convert. They leave together to join up with a mysterious free French garrison at Brazzaville.

Rick’s character arc is not an isolated device but a central organizing principle of the plot. The same process is at work in The Apartment.

The Apartment: A normal world?

The Apartment tells the story of an ordinary accountant, C. C. Baxter, played by Jack Lemmon. In a calculated attempt to gain a promotion, Baxter allows his bosses to use his apartment for their extramarital affairs. Baxter is also smitten with an “elevator girl,” Fran Kubelik, played by Shirley MacLaine. But unbeknownst to Baxter, at least during the first half of the film, Fran is having an affair with the big boss, Mr. Sheldrake, played by Fred McMurray. Sheldrake is only stringing Fran along, though, and because of his treatment of her she eventually attempts suicide. Baxter finds her just in time and with the help of his neighbor, Dr. Dreyfuss, saves Fran’s life.

Baxter becomes Fran’s caregiver, but also Mr. Sheldrake’s protector, ensuring that news of Fran’s suicide attempt does not leak out. In the end, however, Baxter learns the error of his ways and finally follows the advice he is given by Dr. Dreyfuss.

When Baxter does become a mensch, he succeeds in winning Fran’s heart.

The six-step strategy displayed in Casablanca is launched in the opening few minutes of The Apartment.

We learn a great deal from this opening sequence. We learn that Baxter has a problem with his apartment and we learn that Mr. Kirkeby, the boss using his apartment, doesn’t respect him. The boss’s disdain helps garner sympathy for Baxter. Yes, Baxter is ill-advisedly allowing his bosses to use his apartment, but his bosses take advantage of the situation and mistreat him.

So why does Baxter let his bosses push him around? He wants a promotion, but why must he be so obsequious to get it? Is he unworthy? No. As we see right away, he is a hard worker.

In the opening voiceover we learn that Baxter is smart, or at least good with numbers, that he is enthusiastic about his work as an accountant, and that he respects and is impressed with the company he works for. He is a diligent company man, both capable and earnest. So why is he such a pushover?

To answer that question we need to look at the normal world. The film almost immediately introduces us to Consolidated Life, the insurance company Baxter works for. It is a beehive, an impersonal and monotonous corporate colony. And Baxter is depicted as an anonymous drone: he works on the 19th floor, Section W, at desk #861.

Baxter is not just a cog in a machine; he also behaves like a machine when we see his head bob up and down in unison with his calculator. If at the end of the film Baxter becomes a mensch, a human being, then at the beginning of the film he is an automaton. He does what he is told. That is part of being a company man.

Fran, who functions as co-protagonist, works inside a machine. Her gray uniform blends into her surroundings.

Fran and Baxter are insignificant, powerless and anonymous people lost among the 8,042,783 New Yorkers. In The Apartment status, power, money and the freedom to do what you want, other people be damned, are the highest values people can aspire to. And those without status, power and money are nobodies. That is how the normal world works in The Apartment.

The only way to escape anonymity and insignificance is to climb the ladder of corporate and/or social success, and presumably become one of the exploiters. This is exactly what Baxter and Fran try to do. Baxter, after all, wants to be a big boss like the men he lets use his apartment. His gamesmanship eventually allows him to jump the promotion line. His co-worker has been at Consolidated Life twice as long as Baxter, but because he does not play the game, he is not promoted.

Fran wants a promotion too: from mistress to wife of a very powerful man. She becomes to some degree complicit with Sheldrake in disregarding the needs of his wife.

Both Baxter and Fran, then, are willing to climb over other people to get what they want. Still, they aren’t vicious. In most ways, Fran is a kind and encouraging person. When Baxter comes up for his first promotion she tells him, “It couldn’t happen to a nicer guy.” And Fran actually loves Sheldrake. Fran is not Sylvia, a woman we meet in the opening sequence, who seems mostly interested in having a good time.

Just as Fran is not like Sylvia, Baxter is not like his bosses. For one thing, he apologizes to his neighbors for all the noise his bosses make during their trysts. He even tries to correct the situation. And unlike Sheldrake and Kirkeby, Baxter does not want to simply seduce Fran.

Baxter is naïve, a romantic, a rank sentimentalist. And his chances for success in this world, like Fran’s, are limited.

In sum, Baxter and Fran are of two minds. They exhibit both a positive behavior pattern and a negative behavior pattern. This is very important. Because they both basically have good intentions—or aren’t cynical enough for the world they inhabit—they can grow as characters.

But given their good intentions, why do Fran and Baxter have negative behavior patterns? The answer is that each harbors a false belief (related to the normal world) that motivates their negative behavior pattern. Fran’s false belief is that Sheldrake loves her. And because of this she continually trusts him. Here she is going off in a cab to sleep with him, even though we know that Sheldrake hardly cares about her.

In parallel fashion, Baxter believes that corporate success will bring him happiness, but in the end it doesn’t. He gets his big fat promotion with his own office, and he’s miserable.

Still, as long as Baxter harbors the illusion that climbing the corporate ladder will make him happy, he is willing to kiss up to his bosses and allow them to push him around as a way to get ahead. That is Baxter’s negative behavior pattern: he is a toady.

The Apartment: Delay and the darkest moment

Sustaining a character’s positive and negative behavior patterns often becomes of central importance in a film’s second half, when what Kristin calls the Development is launched. In some films the protagonist actually has enough information by this point to reconsider the false belief, but that doesn’t happen. The protagonist clings to error.

The midpoint of The Apartment is the moment roughly an hour into the film when Baxter discovers Fran comatose in his bed. As Kristin points out, a midpoint typically recasts character goals, and Baxter gains a new purpose: saving Fran.

Baxter is worried that Fran will try again to kill herself, so a lot of the Development focuses on his attempts to keep her safe. But Baxter is also protecting Sheldrake during this section of the film. He induces the doctor not to report Fran’s suicide attempt to the police, and he hides Fran in his apartment until she’s better. Baxter’s competing motives, in other words, remain in play. Helping to save Fran’s life, and learning that there is a terrible cost to Sheldrake’s callous behavior should be enough to motivate Baxter to turn against Sheldrake. But he remains on the job.

We see something similar happen about twenty minutes into the Development, when Baxter phones Sheldrake to tell him about the suicide attempt. Sheldrake won’t even come to visit Fran. Baxter is confused and disappointed by this response, but he nonetheless promises his continued support.

This is a common strategy during a Development section. The flawed protagonist is one or more times brought to the brink of character change, but he or she pulls back, clinging to the negative behavior pattern. We see exactly this withdrawal in Casablanca. At the midpoint in that film Ilsa visits Rick and tries to tell him about her relationship with Victor. Rick has an opportunity here to accept the truth, which would set him free, but he rejects it. He clings to his false belief that Ilsa betrayed him and Paris.

Rick is given a second chance roughly halfway through the development when he allows the young couple to win at roulette. Rick’s employee, Karl, is watching from the sidelines, and he is thrilled. He believes that Rick is turning over a new leaf, and so do we. But immediately following this event Victor directly asks Rick for the letters of transit, and Rick bitterly says no.

These are of course delaying tactics, and ones we should expect. Kristin points out that the Development section usually contains numerous delays that create rising tension and suspense, while forestalling resolution.

In The Apartment‘s Development section, certainly Fran’s change of heart is delayed. Despite being driven to attempt suicide by Sheldrake’s treatment of her, she nonetheless announces the next day that she’s still in love with him. She even reaffirms her false belief.

Fran’s near-death experience should be enough to convince her that she needs to end her relationship with Sheldrake, but she too clings to her false belief and negative behavior pattern. Still, in spite of all this, it would be a mistake to say that no progress is being made. Baxter after all is horrified by what Fran has done to herself and Fran is beginning to entertain doubts. She says that “maybe” Sheldrake loves her. And all of this culminates in a moment of self-knowledge:

They are, in short, changing. Also, the possibility of a romantic relationship is finally introduced when Baxter and Fran prepare to sit down to a candlelit dinner together.

With these new story premises in place, the stage is set for Baxter and Fran’s final changes of heart in the climax. But not before a few more delaying tactics are deployed.

First, Fran’s brother-in-law Karl arrives and breaks up Fran and Baxter’s dinner plans. Then Baxter visits Sheldrake to tell him that he is in love with Fran and intends to marry her. But Sheldrake beats him to the punch. His wife has found out about his philandering and kicked him out of the house. Now Sheldrake plans to marry Fran. But to thank Baxter for taking care of business, Sheldrake gives him his big promotion.

As we’ve seen, corporate success is no longer what Baxter wants. In current screenwriter parlance, this is his darkest moment. It’s immediately followed by this exchange:

Fran is clearly ambivalent about her impending marriage to Sheldrake, and Baxter is clearly acting out, trying to hurt Fran. Also, Fran is deeply disturbed to see the cynical side of Baxter out in full force. And this brings me finally to the possible world. As we also saw in Casablanca, the story world in The Apartment is divided, and again the question is who will the protagonist become. Will Baxter grow up to be Dr. Dreyfuss, who represents a communal worldview, or will he grow up to be Mr. Sheldrake, who represents a selfish worldview?

Now it seems that Baxter has become Sheldrake–except we don’t, or aren’t supposed to, believe him. The real point of the exchange between Baxter and Fran is that Baxter no longer holds his false belief. He is using it now only as a defense mechanism, as a cudgel to punish the woman he sees as having betrayed him. He is, in short, pretending. And since he is no longer committed to his false belief he can change.

As has become typical in Hollywood films, the protagonist’s darkest moment leads to enlightenment. In the very next scene Sheldrake asks Baxter for the key to his apartment so that he can bring Fran there for New Year’s Eve, and Baxter says no. When Sheldrake threatens to fire him, Baxter angrily throws a key onto Sheldrake’s desk, and the quiet confrontation ensues.

Baxter thought that the way the stand out was to play along, but in the end he discovers that the way to stand out is to stand alone and cease to be a collaborator. Also, Baxter’s transformation, like Rick’s in Casablanca, inspires a conversion in another character, Fran, and in this way it suggests an overturning of the rules of the normal world. As we’ve already seen, Fran is ambivalent about her new relationship with Sheldrake. And when Sheldrake at a New Year’s Eve party tells Fran that Baxter quit and wouldn’t give him the key, she smiles mysteriously as if finally seeing the light.

She realizes it is Baxter who loves her and not Sheldrake. So she abandons her false belief and the negative behavior pattern it engenders. She leaves Sheldrake and rushes to meet Baxter. And that’s the end of the story.

Two men of two minds

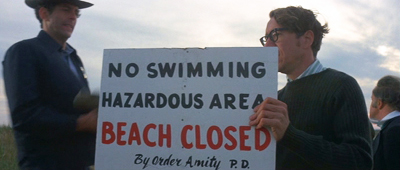

Finally, how enduring are these character-arc patterns? Consider, briefly, Jaws and About a Boy.

Chief Brody is a former New York City police office who has become sheriff of a small island community, Amity. Why did he leave the city? Because, as he explains, crime in New York is out of control and he couldn’t do anything to change that. So he has come to Amity, a world in which, he thinks, one person can make a difference.

Yet for this cop, living in Amity is a cop-out. There hasn’t been a murder there for thirty years. It is a town where one person doesn’t have to make a difference. Yet when the shark arrives, Brody discovers that Amity is the same as New York City. He wants to close the beaches, but the city officials won’t let him. He crumbles under their pressure. Brody is as powerless to make a difference in Amity as he was in New York.

That is how the normal world works in Jaws, and Brody, like Baxter, initially conforms to it. At the beginning of his story he’s defeatist. He always backs down in the face of conflict. He is not confident. Later, on Quint’s boat he wants to turn back. He’s always feeling overwhelmed, a state expressed in his fear of drowning. So Brody goes along to get along.

Accepting his powerlessness is Brody’s negative behavior pattern. But like Baxter and Rick, he can’t help caring. He works to close the beaches, if only for a day, and after a young boy gets killed, he accepts the blame.

Brody exhibits the typical split between positive and negative behavior. Yet because he’s of two minds, he can change. In a crucial turning point, he vows to join Quint and Hooper in hunting the shark. At the climax, he doesn’t back down. He is fearless and he does make a difference. He helps save the town, and in the process he gets over his fear of drowning.

About a Boy, a British-American-French coproduction, released domestically by Universal Pictures, suggests that the techniques I’ve been considering have some cross-border appeal. A 38-year old man-boy, Will Freeman, played by Hugh Grant, lives in luxurious isolation off the royalties from a popular Christmas song his father composed decades before.

Neatly reversing John Donne’s dictum, Will asserts in the opening moments that “all men are islands.” In accordance with this philosophy he has built for himself “a little island paradise,” a swanky apartment filled with cool consumer goods like a chrome-plated espresso maker, a sleek TV, and a vast CD collection. But then Will meets and ultimately befriends Marcus (Nicholas Hoult), a 12-year old misfit with a suicidal mother, who lives his own willed exile because of not being accepted at school.

The story deals with how Will and Marcus and Marcus’s mother Fiona (Toni Collette) become integrated into the world.

Will and Marcus are co-protagonists, but Will’s character arc is more pronounced. Will’s false belief, of course, is that he can make it alone. The problem, though, is that solitude leaves his life devoid of meaning. He has no job and he sleeps with many women but doesn’t date any of them, at least not for very long. As he several times states, “I don’t do anything,” or more to the point, “I do nothing.” Will, however, sees this lack of meaning as a positive: “Me? I didn’t mean anything, about anything, to anyone, and I knew that that guaranteed me a long, depression-free life.”

Will’s false belief is not simply that he thinks he can make it on his own; he believes he can avoid misery by avoiding commitments. This is most apparent when Marcus’s mother attempts suicide.

While Will helps out by driving Marcus to the hospital, the sequence ends with a grim bit of voiceover as we see Will drive off alone into the night.

The thing is, a person’s life is like a TV show. I was the star of the Will show, and the Will show wasn’t an ensemble drama. Guests came and went, but I was the regular. It came down to me and me alone. If Marcus’s mom couldn’t manage her own show, if her ratings were falling, it was sad, but that was her problem.

Will, however, is of two minds, a state the film expresses in a number ways. First, despite being a committed loner, he very early in the plot begins dating a single mother. As we see him gleefully playing with this woman’s young son, he says in voiceover: “And for the next few weeks I was suddenly Will the good guy.”

When Will decides to break up with this woman, in part because she made him late to an IMAX movie, he adds, “I was going to have to end it, but having been Will the good guy I did not relish going back to my usual role of Will the unreliable, emotionally stunted asshole.” He is, apparently, self-aware, and his use of the word “role” seems intentional, suggesting as it does that Will the Asshole is a persona he adopts to avoid complications. We also learn that in the past Will volunteered at a soup kitchen, though he admits he never made it there to help out. And we discover that for a time he worked the phones at Amnesty International, but seems to have mostly used this as an opportunity to pick up women on his call lists.

The point the filmmakers are comically making is that Will has good impulses, but is unable to sustain them in the long term. He has both a positive behavior pattern and a negative behavior pattern, the latter very clearly motivated by his false belief.

The normal world is established as one in which people are abandoned. The film is full of single moms, including Marcus’s mother, and Will tries to abandon everyone he meets. In the opening scene he throws away the phone number of a woman he has slept with, even as she is leaving an inviting message on his answering machine.

Most significantly, Fiona almost abandons Marcus when she attempts suicide. In the wake of this, Marcus is worried that his mother will try again, and that she may succeed when he’s not there. He gets an idea: “Suddenly I realized that two weren’t enough. You needed backup.” With this realization Marcus defines the possible world for us. It is one that is comprised of teamwork and mutual support. In search of this new world, Marcus attempts to fix up Will with his mother. His goal is to get Will to marry her so that they can both look after her.

The dreamed-of marriage never occurs, but Marcus and Will slowly become friends, spending most afternoons together watching TV and sometimes talking. Will helps Marcus become more cool, which allows him to begin making friends at school.

Because of his growing friendship with Marcus, Will comes to realize that misery stems from loneliness, not commitment. He abandons his false belief and the negative behavior pattern it motivates. Not only does he fall in love, but for Marcus’s sake he also offers his friendship and emotional support to Fiona to help prevent her from attempting suicide again. In this way he demonstrates that he has learned the necessity of real, meaningful relationships. The film ends with all the main characters together in Will’s apartment–once his desert island paradise–sharing Christmas lunch. There is even a hint that Fiona too will find love. This ending marks a clear overturning of the rules of the normal world.

Two Minds, Positive and Negative Behaviors, False Belief, Normal vs. Possible Worlds: Maybe all character arcs don’t follow these principles. We’ll have to test them against many more movies. At least, though, they seem to offer widespread, enduring strategies for constructing character change.

In every case I’ve considered, the protagonist discovers his or her “true” self, the good or well-adjusted person that has been lurking within all along. Which suggests that radical, 180-degreee character change is rare–most likely because it is difficult to motivate. Arguably, though, Breaking Bad pulled off a version of it. And speaking of Walter White, it remains to be studied how character change is typically handled in long-form television, which is becoming an ever more significant mode of Hollywood storytelling.

For more on principles of Hollywood plotting, see the entry “Open Secrets of Classical Storytelling,” “Understanding Film Narrative: The Trailer,” and “Time Goes by Turns.” Some ideas about character change are set out in “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.” There’s a bit on The Apartment as a 1960 film here.

About a Boy (2002).

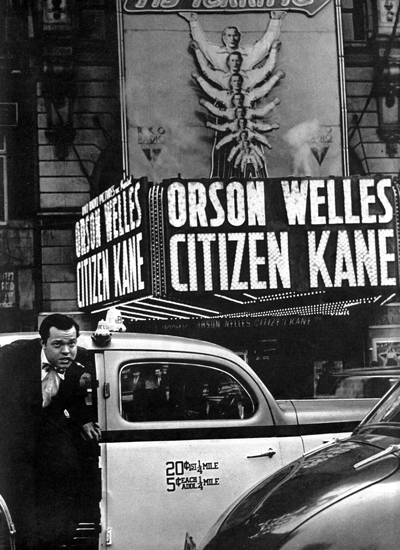

Welles at 101, KANE at 75 or thereabouts

DB here:

Kristin and I are one-third through our New York stay, and blogging has suffered. There have been talks to give, old friends to visit, new friends to meet, and movies and exhibitions to see. And there’ll be more activities of these sorts to come. But I can’t let 6 May pass without some acknowledgment of Orson Welles.

That’s partly because I just finished a draft of the Welles section of my 40s Hollywood manuscript. (Yeah, that beast was another distraction from blogging. All 158,000 rough-hewn words of it are now dispatched to some unwary readers.) So Welles was on my mind already when the anniversary of the “official” Citizen Kane release came up on 1 May.

Actually, by the time Kane had that roadshow release, it had been widely seen by the Hollywood community. In the face of the Hearst press’s attacks, RKO head George Schaefer held invitational screenings in early 1941 to build up support for the film. Variety estimated that by late March 1,200 producers, directors, writers, actors, and agents had seen the picture. The number was so big that RKO dispensed with a splashy Hollywood opening. (The article title is pure Varietyese: “So Many Cuffo Gloms at ‘Kane’ It Kayoes Idea of a $5.50 Preem,” Variety, 2 April 1941, 2, 20.) As a result, I think, Kane‘s influence began to be registered some months before its New York premiere, as the look of The Maltese Falcon (shot June and July of 1941) might suggest.

What I offer today, on the Boy Wonder’s birthday, is a consideration of that movie from an unusual angle looking not just at its originality but also at its shrewd consolidation of a variety of techniques.

Wellesapoppin’

We’re so used to considering Kane powerfully original that it’s worth remembering that it synthesizes a lot of traditions. I’m not thinking of Pauline Kael’s claim that it’s a culmination of the 1930s newspaper genre; as so often, she fails to persuade me. I’m thinking instead of the look and sound of the movie, as well as its storytelling strategies.

Depth staging and deep-focus cinematography are two techniques not always kept distinct in critical discussion. 1930s Jean Renoir films have plenty of depth staging but usually not so much deep focus. Citizen Kane won attention partly because it has plenty of both, and in exaggerated form. The figures often stretch very far back, someone or something is often rather close to the camera, and often all of them are sharply focused.

Without taking anything away from the boldness of Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland, we should recognize that they reworked visual patterns—what I’ll call schemas—that were already circulating in filmmaking. Framings with big foregrounds, distant planes, and low angles weren’t unknown in silent films (Opium, 1919; Greed, 1925; A Woman of Affairs, 1928) and some early talkies (No Other Woman, 1933).

There was a sort of fad for such deep staging, especially with wide-angle lenses, during the late 1930s, though all the planes weren’t usually kept in focus. Some directors, such as John Ford (here and here) and William Wyler, favored deep images, while art director William Cameron Menzies (see here and here) made them part of his artistic signature. Below: Ford’s Long Voyage Home (1940), shot by Toland, and Menzies’ Our Town (1940), directed by Sam Wood.

It’s now acknowledged that many of Kane’s deepest shots weren’t actually made in the camera, but by means of special effects, particularly matte shots. Interestingly, this too wasn’t utterly original; compare the composite shot from Kane with the one from Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1935), which has an even more aggressive foreground.

Welles and Toland called attention to these techniques by a radical gesture: many of these deep shots are long takes from a fixed camera position. Most filmmakers who used these depth schemas inserted them into passages of orthodox scene dissection. The depth shots might establish a locale, or they might be inserted into a series of analytical cuts, or they might be part of a shot/ reverse shot pattern. But in Kane you’re forced to notice the Baroque plunge of space because the lengthy take rubs your nose in the flashy composition.

It’s clear that Kane crystallized a certain look that was picked up by John Huston, Anthony Mann with or without his DP John Alton, and many other directors. The Welles/Toland version of depth consolidated a visual style that dominated American black-and-white filmmaking into the 1960s. Typically, though, filmmakers didn’t rely on the fixed long take as much as Welles did in Kane. Even Welles gave up that option in favor of dynamic editing of deep-focus shots, as in The Lady from Shanghai (1948) and Othello (1952/1955).

Not everything is long takes and depth. The pictorial variety of the film is, I think, unprecedented. The “News on the March” sequence becomes a virtuoso exercise in all the techniques that the rest of the film won’t be using. For perhaps the first time in history, Welles artificially distresses his staged scenes to make them match archival footage. He adds scratches and light flares.

This newsreel is so film-savvy that it can build in jump cuts and fast-motion as guarantors of fake authenticity. One passage mimics two-camera reportage, allowing us to imagine paparazzi crouched and perched at a fence to grab clandestine shots of an elderly Kane.

Here the schemas that are borrowed come from archival and documentary traditions, repurposed to add realism to this fictional biography. Welles, as we’ve seen in the Great Ambersons Poster Mystery (here and here and here), was a smart-alec cinephile: your disobedient servant.

What about sound? Back in 1994, Rick Altman wrote a pioneering article showing how Kane manipulates our sense of auditory space, and he connected that to Welles’ use of radio conventions. Contrary to what we might expect, Welles’s soundtrack doesn’t create much “deep-focus sound”; Altman shows that our impression of that is created chiefly by an overall reverberation rather than precise placement of sonic events. Altman also stresses Welles’ use of sudden, loud sound events to start or end a scene–another radio technique.

Today we’re lucky to have a great many of Welles’ radio programs available on the Web, and we can appreciate how his rich soundscapes mingle noises, dialogue, and voice-over narration. These shows remain very gripping. Listening to Kane in the same spirit, I’ve been impressed with how talky it is, how sounds crash in on you, and how even bursts of silence can be startling. Welles told one biographer that he aimed to create spiky transitions, both visual and sonic, because he thought most films of the period were dull.

He had already made his stage reputation on “shock effects,” those stunning high points in particular productions: the death of Macbeth in the Harlem production (1936), an actor’s headfirst tumble into the orchestra pit in Horse Eats Hat (1936), the mob’s murder of Cinna the Poet in Caesar (1937), the guillotine scenes in Danton’s Death (1938), and police agents firing from the audience in Native Son (1941). He became known as a director of thrilling moments, ever willing to sacrifice steady buildup to anything that would astonish. Forties theatre critics had a name for it: “Wellesapoppin’.” That quality dominates Kane’s images and sounds.

Remembering, recounting, replays

Otto Hullet, Barbara O’Neill, and Orson Welles in Sidney Kingsley’s Ten Million Ghosts (1936).

Just as Kane amplifies visual and auditory schemas already in circulation, the film does somewhat the same thing to narrative strategies. The key innovation here involves flashbacks and point of view.

Flashbacks were rare in the 1930s, but the early 1940s began a flashback craze that continued throughout the decade. Between August 1940 and December 1941, every top studio tried out flashbacks in a major release: The Great McGinty (Paramount), Kitty Foyle (RKO), I Wake Up Screaming (Fox), H. M. Pulham, Esq. (MGM), and Strawberry Blonde (Warners). A reviewer claimed that the “retrospective viewpoint” technique in A Woman’s Face, released the same month as Kane, “had of late become commonplace.” By September 1941 the Los Angeles Times critic considered the technique overused.

Even though the trend was already launched, Kane probably strengthened Hollywood’s inclination toward time-shifting. Again, it crystallizes in an influential way possibilities opened up in film, radio, theatre, and other media.

Kane’s central premise—a dead man recalled by one or more survivors—had been rehearsed in earlier films. The Power and the Glory (1933), scripted by Preston Sturges, was probably the most noted experiment in that vein. (For more, see this long-ago entry.) Another example was The Life of Vergie Winters (1934), which begins with a funeral procession and flashes back to the start of a backstreet love affair. (See this entry.) The Escape (1939) centers on a doctor who tells a crime reporter about a recently deceased neighborhood gangster, and flashbacks enact his tale.

These earlier examples stick to a single teller, while Kane offers reports on its dead man from five characters. Here again, however, there are precedents. In fiction and drama, trials have long served as motivation for flashbacks from multiple viewpoints. A major example, perhaps the first, is Robert Browning’s verse novel The Ring and the Book (1868-1869). Multiple tellers recounting events in flashback were staples of Hollywood courtroom dramas too. Beyond the trial-based format, Welles’ radio programs had welcomed multiple storytellers, sometimes embedding them within one another’s tales, sometimes letting them banter with each other.

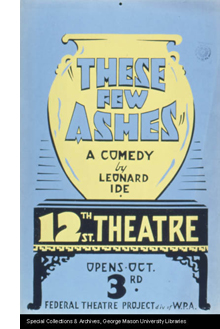

Kane assembles views on a person rather than evidence of a crime, but even this is not completely unknown. Some playwrights had tried out what Kane screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz had called the “prismatic” approach to an absent central character. Sophie Treadwell’s play Eye of the Beholder (1919) portrays an offstage woman as seen through the eyes of her former husband, her lover, her lover’s mother, and her own mother. The play These Few Ashes (1928) presents the life of a (supposedly) dead roué through the recollections of three women, each of whom sees him quite differently.

Then there’s reporter Thompson’s investigation. The Power and the Glory’s exhumation of the tycoon’s past is presented simply as his old friend’s recounting; it’s not the investigation of a mystery. Kane innovated in the biographical film genre by creating curiosity based on the dying man’s last word, “Rosebud.” That device shifts us to the terrain of the detective story. The dying message had become a mystery-tale convention from Conan Doyle onward, and Welles and Mankiewicz shrewdly recruited it for their purposes (although it’s not clear exactly who hears Kane say the crucial word).

In blending conventions of several genres, Kane motivates the flashbacks on diverse grounds. The film’s detective-story side is anticipated by The Phantom of Crestwood and Affairs of a Gentleman (1934); in both, flashbacks represent the suspects’ answers under questioning. Like The Escape, Kane uses a reporter’s search for a story to justify its flashbacks, and the reporter isn’t the protagonist (as he’d be in a typical newsman movie). And being something of a biopic, Welles’s film can trace the rise of a great man from the vantage point of old age, as in Edison, the Man (1940). By the way, that’s another film of the era using a journalist’s questioning to launch flashbacks to a person’s life.