Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

Deadlier than the male (novelist)

DB here:

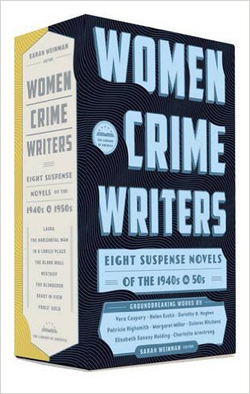

It’s about time! Sarah Weinman, editor of Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives (already praised in these precincts) has brought out a two-volume set devoted to women crime writers of the 1940s and 1950s.

It’s not that these authors are utterly unknown. Popular in their day, some retained a following for a few decades, and Patricia Highsmith has become an enduring figure. Yet the never-ending frenzy for male-oriented noir in books and movies has led us to neglect what these writers and their peers accomplished. In the online essay “Murder Culture” I argued that we’ve probably overemphasized the hardboiled detectives and brutalized losers, and we’ve not paid enough attention to the accomplishments of other writers. The rise of the psychological thriller was central to 1940s popular culture.

Granted, it wasn’t only gynocentric. The thriller assumed exciting shapes in the hands of talented men like Patrick Hamilton, Cornell Woolrich and John Franklin Bardin. But the 1940s saw the emergence of a powerful cadre of women writers, many of whom started writing “pure” stories of detection but decided that suspense would be their forte. Surely they were encouraged by the success of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, the best-selling mystery novel before Mickey Spillane came on the scene. But these suspense-mongers avoided mimicking Mignon Eberhart and other predecessors in the innocent-girl-in-a-spooky-house tradition. These new talents saw menace crouching behind the windows of drab houses and apartment blocks. Out of several tendencies I tried to sketch in that essay, they forged a tradition of what Weinman calls “domestic suspense.”

The Library of America volumes give us a fine occasion for appreciating what they accomplished.

Artisans of suspense

You might say that Double Indemnity and Out of the Past are quintessentially 1940s-1950s films, and I’d agree. But other important films were derived from works by women writers. The list of Highsmith adaptations, starting with Strangers on a Train (1951), is too long to recite here, but let’s remember that Charlotte Armstrong provided source novels for The Unsuspected (1947) and Don’t Bother to Knock (1952, from Mischief), as well as for Chabrol’s La Rupture (1970) and Merci pour le Chocolat (2000). Filmmakers produced now-classic versions of the Dorothy B. Hughes novels The Fallen Sparrow (1942), Ride the Pink Horse (1946), and In a Lonely Place (1950). The prolific but less famous Elizabeth Sanxay Holding gave us The Blank Wall (1947), adapted twice (The Reckless Moment, 1949, and The Deep End, 2001). Dolores Hitchens’ Fools’ Gold (1958) yielded the implausible basis for Godard’s Band à part (1964). Helen Eustis’s The Fool Killer (1954) became a 1965 film. And of course Vera Caspary’s Laura (1943) became a monument of studio moviemaking.

The thriller, you could argue, makes more engaging cinema than the straight detective story. Much as I admire cinematic sleuths like Sherlock Holmes, Nick Charles, Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, and particularly Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto, pure mystery plots need a lot of bells and whistles to keep from being simply a matter of following the detective as he moves from place to place asking questions and dodging blows on the head. The 1940s tales of espionage, women in peril, serial killings, household anxieties, warped husbands and crazy wives and guileless governesses and all the rest have left a stronger legacy today. We live in the Age of the Thriller, as a glance at any bestseller list will indicate. The recent death of Ruth Rendell, arguably Highsmith’s only top-flight competitor, can only remind us of how the genre has flourished for decades.

As for the Library of America collection: You couldn’t much improve on Weinman’s selection, I think. All eight novels were appreciated in their day, and some won awards. A reader coming fresh to them will be surprised, I think, by the variety of treatment and the vigor of the writing. It’s to be hoped that encountering these will encourage readers to go on to other works by the same authors. In particular, I’d recommend Sanxay Holding’s The Death Wish (1934), a prefiguration of Highsmith’s dissection of male vulnerability; Margaret Millar’s Do Evil in Return (1950), which centers on a female doctor regretting not helping a woman obtain an abortion; Millar’s chilling The Fiend (1964); and of course almost anything by Dorothy B. Hughes, not least The Expendable Man (1963).

As for the Library of America collection: You couldn’t much improve on Weinman’s selection, I think. All eight novels were appreciated in their day, and some won awards. A reader coming fresh to them will be surprised, I think, by the variety of treatment and the vigor of the writing. It’s to be hoped that encountering these will encourage readers to go on to other works by the same authors. In particular, I’d recommend Sanxay Holding’s The Death Wish (1934), a prefiguration of Highsmith’s dissection of male vulnerability; Margaret Millar’s Do Evil in Return (1950), which centers on a female doctor regretting not helping a woman obtain an abortion; Millar’s chilling The Fiend (1964); and of course almost anything by Dorothy B. Hughes, not least The Expendable Man (1963).

The Library of America collection has rounded up several contemporary purveyors of suspense to write brief online appreciations of the titles in the collection. These are well worth reading. On each page further links take you to fresh material. There’s also a succinct introduction by Weinman. The print editions include her judicious career summaries, as well as notes on allusions and citations in each novel.

For readers interested in how women’s cultural roles are represented in fiction, these books provide a field day. Several of the professional commentaries suggest that the authors injected social criticism into their works. These writers are far more willing to get inside men’s heads than the hard-boiled boys are to think like a woman, so you can see the macho attitude in a new light. Here’s how Dorothy B. Hughes in The Candy Kid (1950, not in this collection) describes her hero:

Just as he was thinking that he’d better go in and buy a pack, wait for Beach in the air-cooled coffee shop, the girl came around the corner. She was tall, almost as tall as he, but he took a quick look at the pavement and saw that she was propped on heels. That made him feel more male.

Very often these writers take certain stereotypes, both male and female, and submit them to pressure through their craft. Others seem to accept those stereotypes and employ them for their own storytelling ends. Those ends are very much worth our attention.

We know that several of these writers were self-conscious artisans. Hughes and Armstrong wrote articles reflecting on mystery and suspense, while Hughes also wrote a sharp biography of Erle Stanley Gardner. Hughes also conducted a course on mystery writing at UCLA in the 1960s; she invited Vera Caspary in for a guest lecture, and Caspary’s advice makes for fascinating reading. Highsmith’s notebooks, preserved at the Archives littéraires in Switzerland, are filled with meditations on story problems, and she wrote as well a book-length manual, Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction (1966, 1981). I don’t think that any hard-boiled writers of the era have left such systematic reflections on the nuts and bolts of their work.

Once we pay attention to technique, we can see how these writers rework topics and concerns of the day. For example, we could talk a long time about how social roles induce women to assume a split identity: one face for friends and family, another that resists the masquerade. But these, after all, are mysteries, so that divided identity has to be dramatized—or better yet, played with and teased out for the sake of suspense and surprise. It’s remarkable that two of the books in the collection exploit the syndrome of Multiple Personality Disorder, which becomes part of the final surprise. Another, Laura, makes an enigma of the woman’s inner life by virtue of dispersed viewpoints.

If we want to learn about storytelling, we can usefully look at how writers manage traditional demands of craft. These books “say what they say” in and through technique—narrative form, literary style. The experience that results can be an enduring achievement.

Pronoun trouble

No use asking if the crime writer has anything of the criminal in him. He perpetuates little hoaxes, lies and crimes every time he writes a book.

Patricia Highsmith

Start with style—important in all storytelling, but posing some fascinating issues in the domestic thriller.

One problem faced by all these writers was: How to avoid the sentimental style of romantic suspense writers? Here’s a typical passage from Mignon G. Eberhart’s Another Woman’s House (1946).

She said, blindly choosing trite and inadequate words, “You cannot change your own sense of loyalty, of your own creed and code. It’s bred in your bone; it’s part of your body.”

He understood all the argument below it. He understood too that it was a fundamental argument in his own heart. His eyes deepened, searching her own. He said suddenly, “Myra, you must see this sensibly; you must be realistic and . . .”

“Oh, Richard, Richard!” She cried despairing, and put her head against his shoulder.

There’s some of this novelettishness in Armstrong, as in this bit from Mischief:

When a fresh scream rose up, out there in the other room in another world, Ruth’s fingertips did not leave off stroking into shape the little mouth that the wicked gag had left so queer and crooked.

Hughes and Hitchens, I think, leaned toward the hardboiled laconicism of Hammett and Cain, though without the slanginess. In The Horizontal Man, Eustis tries for a brittle, satiric tenor and some Hollywoodish banter between a reporter and a college woman. Highsmith was adamant in refusing what she called a “pulp” style. Hence her flat, spare simplicity. (Funny, though, since she started out writing comic books for the company that would become Marvel.)

Stylistic options can lie very far down. For years I’ve been curious about what fiction writers call their characters on first entrance. It’s a fundamental creative choice, and it’s absolutely forced: you have to call them something. And what you call them matters.

Here’s the beginning of Armstrong’s Mischief:

A Mr. Peter O. Jones, the editor and publisher of the Brennerton Star-Gazette, was standing in a bathroom in a hotel in New York City, scrubbing his nails. Through the open door, his wife, Ruth, saw his naked neck stiffen….

Cozy, our relation to this Mr. and Mrs. Jones: Mischief gives their first and last names. So far, no reason to be apprehensive. But here’s the start of Hitchens’ Fools’ Gold:

The first time they drove by the house Eddie was so scared he ducked his head down. Skip laughed at him.

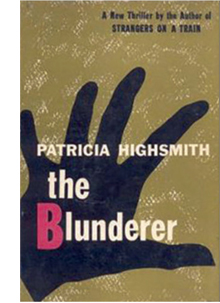

Here a relationship is defined through laconic action: we’re on a first-name basis with the pair. It’s as if we’re riding in the back seat.  Compare the opening of Highsmith’s The Blunderer.

Compare the opening of Highsmith’s The Blunderer.

The man in the dark blue slacks and a forest green sportshirt waited impatiently in the line.

The girl in the ticket booth was stupid, he thought, never had been able to make change fast.

Highsmith is more ominous: No names, just a man as if seen from across the sidewalk. Yet we can’t say the presentation is “objective” because we’re given his annoyed thoughts about the ticket girl. So we are forced to ask: If I’m in his head, why don’t I know who he is? And why is he in a hurry?

And finally, the opening lines of Eustis’ The Horizontal Man:

The firelight played over all the decent, familiar objects of his everyday life; he viewed them desperately, looking for some symbol of succor. The firelight played on his rolling eyeballs, the careless tendrils of his black hair. “Oh now,” he said, “Oh now, I say, look here…” trying to summon a tone of commonplace to breast the tide of nightmare that was rising in that room.

Eustis dispenses with everything but he in describing something terrible going on. Not only do we not know who’s suffering, but we won’t know for some time. This, like the Highsmith, might be called “pronominal mystery”: not knowing anything about who’s in danger, we sense the danger as a pure force swallowing up trivialities of identity.

Most manuals of fiction-writing start by reviewing the bigger choices, like first- or third-person narration, but note that even within third-person storytelling, these passages bristle with different implications. Each of these openings puts us in a different relation to the characters picked out.

The storyteller makes a choice about how to name the actors in the scene, and that choice leads to others: the scene is built out the premises of what have launched it. Ruth, who studies her husband Peter at the mirror, will become one conduit of information within Mischief. Skip, who laughs at Eddie as they size up the home they’ll invade, will bully his partner throughout Fools’ Gold. The man in the slacks and sportshirt will drop out of The Blunderer for several chapters. So no need to name him yet; magnify the mystery. And the opening scene of The Horizontal Man will continue with personal but untagged pronouns—a she will be picked out too—as the full awfulness of the action emerges.

I suspect that the development of the suspense thriller in the 1940s sensitized writers to fine-grained choices like this. The verbal fabric became part of the suspense: not just what will happen next? but why is the action being presented in this way? This second layer of intrigue seldom occurs in the hardboiled detective novels. While Hammett, Chandler, and Ross Macdonald (married to Margaret Millar) slipped easily into first person and easygoing openings, these women writers were willing to try more oblique, tantalizing, and formally adventurous options. (Though we find them in Goodis, Woolrich et al. as well.) Without this newly cultivated sensitivity to names and non-names, proper nouns and pronouns, I doubt we would have the tour de force of Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying (1953) and the shock of Hughes’ Expendable Man, or the brilliant opening of Ruth Rendell’s Wolf to the Slaughter (1967).

I suspect that the development of the suspense thriller in the 1940s sensitized writers to fine-grained choices like this. The verbal fabric became part of the suspense: not just what will happen next? but why is the action being presented in this way? This second layer of intrigue seldom occurs in the hardboiled detective novels. While Hammett, Chandler, and Ross Macdonald (married to Margaret Millar) slipped easily into first person and easygoing openings, these women writers were willing to try more oblique, tantalizing, and formally adventurous options. (Though we find them in Goodis, Woolrich et al. as well.) Without this newly cultivated sensitivity to names and non-names, proper nouns and pronouns, I doubt we would have the tour de force of Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying (1953) and the shock of Hughes’ Expendable Man, or the brilliant opening of Ruth Rendell’s Wolf to the Slaughter (1967).

Fussy as these details are, they’re what I mean by craft. The verbal texture of any piece of fiction depends on dozens of such minute judgments. Just as in film every cut, camera movement, and actor’s glance matters, so does every word in a prose narrative. These writers understood that what we learn, syllable by syllable, can be a potent source of uncertainty and suspense.

Who sees and who knows?

The whole intricate question of method, in the craft of fiction, I take to be governed by the question of the point of view—the question of the relation in which the narrator stands to the story.

Percy Lubbock, The Craft of Fiction

In mystery fiction, management of point of view is critical. Not only will it weave the moment-by-moment verbal tissue, but it provides the large-scale parts that present the overall action. Where the Had-I-But-Known romance tends to be restricted to a single character, often through first-person narration, domestic suspense employs other options. It’s significant that of these eight novels, only one, Laura, employs first-person narration, and that in a distinctive way I’ll consider further along.

Unrestricted narration is a good strategy for maximizing suspense, as we see in Armstrong’s Mischief. A husband and wife leave their little girl with a babysitter in their hotel while they go off to an awards dinner. But the babysitter is one of those Crazy Ladies that the 40s produce in great profusion and the child is endangered.

Unrestricted narration is a good strategy for maximizing suspense, as we see in Armstrong’s Mischief. A husband and wife leave their little girl with a babysitter in their hotel while they go off to an awards dinner. But the babysitter is one of those Crazy Ladies that the 40s produce in great profusion and the child is endangered.

How to complicate this basic situation? Armstrong recruits a device—call it a narrative meme if you want—that emerges at the period: the eyewitness, typically in an urban setting, who glimpses possibly criminal doings and gets involved. This device finds its supreme filmic expression in Rear Window (1954), but it’s established in earlier films like Lady on a Train (1945), Shock (1946), and The Window (1949), and in the radio drama The Thing in the Window (1945), by Lucille Fletcher (another thriller queen, but of the airwaves). In Mischief, people in a building across the street from the hotel intervene in the doings of the babysitter, and the plot “intercuts” all their trajectories in order to create tension.

Hitchens’ Fools’ Gold similarly jumps from character to character, even within a single scene. This tale of a heist that is way above the skill sets of the thieves—a sort of humorless anticipation of an Elmore Leonard or Donald Westlake situation—uses unrestricted narration to build sympathy for the characters who are gulled into participating.

Central among these is Karen, pathetically happy that Skip is paying attention to her. One chapter starts with her meeting him after class, snuggling warmly into his arms (“Here was someone to whom she could confide the disaster with the coat”), before the narration switches brusquely to him:

Central among these is Karen, pathetically happy that Skip is paying attention to her. One chapter starts with her meeting him after class, snuggling warmly into his arms (“Here was someone to whom she could confide the disaster with the coat”), before the narration switches brusquely to him:

Skip listened, at first with indifference. He’d heard already from Eddie of Karen’s reaction to the money, her frightened excitement about it. It took a moment to realize that this wasn’t more of the same, the reaction of an inexperienced girl, but that a bad break had really occurred.

Throughout the chapter, this rather nineteenth-century version of omniscience will toggle between Karen and Skip, heightening the disparity between her lack of awareness and his harshness. “He was just having fun though she didn’t know it.” Arguably, a heist plot needs a certain wide-ranging narration (see The Asphalt Jungle), but Hitchens uses it to take us into the minds of all the characters, major and minor, and suggest both vulnerability and menace.

In a classic detective story, the identity of the culprit is concealed until the end. One Golden Age “rule” is that in the course of the action we must never be given the viewpoint of the killer. The rule was broken on occasion, notably in a certain novel by Agatha Christie, but it remained rather firm. In the thriller, by contrast, we can be in the killer’s mind, knowing full well that he or she is indeed the killer. A prototype is Patrick Hamilton’s Hangover Square (1941). Two books in this collection walk a line between detective story and thriller in this respect.

In Eustis’ The Horizontal Man, a popular professor has been murdered. The effects of his death ripple out across the campus, and the narration shifts among his colleagues, some students, and a reporter investigating the crime. In the midst of a corrosive satire of the academic life, we suspect that someone whose mind we have entered will turn out to be the culprit. So we have to probe the inner lives of the characters we encounter for psychological clues, not physical ones. The author must conceal the killer’s identity and “play fair,” in that what we learn at the end unexpectedly fits the characters’ stream-of-consciousness musings.

A similar problem confronts Margaret Millar in Beast in View. At the start the viewpoints aren’t quite so dispersed: initially, we shift between a woman plagued by threatening phone calls and an amateur investigator looking into the matter. As the mystery deepens, however, the range of knowledge spreads and we get “lateral” viewpoints on the central situation. This is partly to deflect us from the grim revelation that we have been quite thoroughly misled.

A similar problem confronts Margaret Millar in Beast in View. At the start the viewpoints aren’t quite so dispersed: initially, we shift between a woman plagued by threatening phone calls and an amateur investigator looking into the matter. As the mystery deepens, however, the range of knowledge spreads and we get “lateral” viewpoints on the central situation. This is partly to deflect us from the grim revelation that we have been quite thoroughly misled.

It is a pity that this edition didn’t include Millar’s 1983 Introduction and Afterward. The latter explains the origin of the book’s device, while the Introduction reports the effects the book had:

I was threatened with a libel suit, informed by a patient in a mental institution that at last she had found someone who really understood her, invited to join a coven of witches, asked to address a meeting of psychiatric social workers, and presented with the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Allan Poe award for best mystery of the year.

At the other extreme, two of these novels focus on extremely restricted viewpoints. Hughes’ In a Lonely Place is wholly locked within the mind of a hypermasculine ex-Air Force pilot who trails and murders women. Hughes gives us the pronominal tease: it’s he for the first five pages until, when he places a phone call, we learn he’s called Dix Steele. In a cat-and-mouse game reminiscent of films like Woman in the Window and Where the Sidewalk Ends, the killer gets close to the murder investigation. Dix’s army buddy is the chief cop on the case, so Dix can monitor things and even drop in on crime scenes. Strikingly, Hughes puts the killings “off-page.” This admirably eliminates any Spillane-ish sensationalism while keeping the focus wholly on the way Dix loses control of his masquerade. He’s worn away in a series of confrontations with two women who see, as no man can, something deeply wrong in him.

Closest to the traditional woman-in-peril plot is Sanxay Holding’s The Blank Wall. While her husband is away in the service, a middle-class housewife learns that her daughter has been seduced by a sleazy opportunist. The wife soon becomes the target of two blackmailers, one of whom grows to love her. Gifted with a pair of obnoxious and ungrateful children and an amiably oblivious father, the heroine is doubly trapped—within a confining household and a crime cover-up. We’re limited to her range of knowledge, so every encounter is charged with uncertainty about the motives of others. She can’t confide in her husband and so must write bland letters to him reporting that everything is just fine.

Closest to the traditional woman-in-peril plot is Sanxay Holding’s The Blank Wall. While her husband is away in the service, a middle-class housewife learns that her daughter has been seduced by a sleazy opportunist. The wife soon becomes the target of two blackmailers, one of whom grows to love her. Gifted with a pair of obnoxious and ungrateful children and an amiably oblivious father, the heroine is doubly trapped—within a confining household and a crime cover-up. We’re limited to her range of knowledge, so every encounter is charged with uncertainty about the motives of others. She can’t confide in her husband and so must write bland letters to him reporting that everything is just fine.

As you’d expect, Highsmith tries something more intricate in The Blunderer. Here we have two protagonists, each man given his own viewpoint. But after an opening introducing us to one man’s crime (in a scene that spares no violent detail), he drops out of the action for a hundred pages. We concentrate instead on the polished professional lawyer whose life unravels when his domestic skirmishes—nearly all petty and drab—come to a head. As with most Highsmith men, he is tempted to do something very trivial and very stupid, almost out of intellectual curiosity. Highsmith policemen take a dim view of such enacted thought experiments.

As the two protagonists’ worlds converge, we get the characteristic Highsmith themes of self-possessed men losing their nerve, the traps of respectable life, the risk of impulsive action, the ways in which friends turn away from you when they suspect you of lying. The lawyer is called by his first name, Walter, while his counterpart is known to us by his last name, Kimmel. In such subtle ways does an author align us a little more closely with one character than another. Both, though, are blunderers.

I should add that all the markers of 1940s fiction and film—dreams, hallucinations, false fronts, unstable families, untrustworthy lovers, socially adroit psychopaths—are woven into these novels with great skill. What more could you ask?

A frenzy of recapitulation

Vera Caspary, 1946.

The earliest novel in Weinman’s collection is also one of the most remarkable of the period. Vera Caspary was a woman to be reckoned with—Greenwich Village free-love practitioner, Communist party member, occasional screenwriter, boundlessly energetic purveyor of suspense fiction, passionate paramour of a married man, and advocate for women in prison. Our State Historical Society holds her personal collection, which includes fascinating notes on projects both realized and unrealized. Turning the pages of her files, you meet a crisp, professional artisan.

So let’s look at Laura the novel. If you know the film, as you probably do, nothing I say will spoil the book for you.

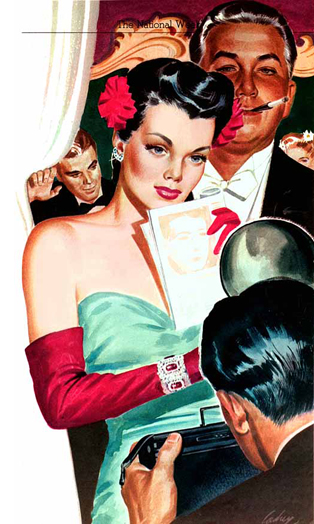

In 1942 Collier’s (“The National Weekly”) offered Caspary $10,000 for the serial rights to Ring Twice for Laura. That sum, equal to $150,000 today, didn’t include book publishing rights, movie rights, and any other ancillaries. The price tag tells us quite a bit about the robust slick-magazine market of the period and about Vera Caspary’s standing. After writing novels, plays, short stories, and screenplays, she was no novice, but her new manuscript set her on a path toward fame. Published as Laura in 1943, it found acclaim as “something quite different from the run-of-the-mill detective story.” The publisher called it a “psychothriller.”

Laura is both a mystery story and a romance. A woman is found murdered in her apartment. Although a shotgun blast has disfigured her face, she’s initially identified as ad executive Laura Hunt. After the funeral, while detective Lieutenant Mark McPherson is poking around her apartment, Laura returns from a trip and it’s revealed that the victim was actually Diane Redfern, a model to whom Laura had loaned the apartment.

The misidentified-victim convention triggers an investigation into the usual sort of suppressed backstory: How did Diane wind up in Laura’s place? Was she alone? Was she the target all along, or was she mistaken by the killer for Laura? Along the way, the cop—already half in love with Laura dead—begins to both woo and browbeat her.

At the same time, a cluster of suspects needs questioning: Laura’s flighty Aunt Susie, her fiancé Shelby Carpenter, and her lordly patron, the columnist Waldo Lydecker. Laura isn’t exonerated either, because she has reason to hate Diane. The usual array of clues—the murder weapon, a bottle of cheap bourbon, and a cigarette case—tugs McPherson this way and that, although his final discovery of the killer depends as much on intuition about personality as about physical traces. The plot hole in the film (why isn’t the artist Jacoby, who painted Laura’s portrait, an obvious suspect?) is there in the original novel as well, but few readers or viewers seem to notice it.

At the same time, a cluster of suspects needs questioning: Laura’s flighty Aunt Susie, her fiancé Shelby Carpenter, and her lordly patron, the columnist Waldo Lydecker. Laura isn’t exonerated either, because she has reason to hate Diane. The usual array of clues—the murder weapon, a bottle of cheap bourbon, and a cigarette case—tugs McPherson this way and that, although his final discovery of the killer depends as much on intuition about personality as about physical traces. The plot hole in the film (why isn’t the artist Jacoby, who painted Laura’s portrait, an obvious suspect?) is there in the original novel as well, but few readers or viewers seem to notice it.

What was striking about the book was its point-of-view structure. “Four persons tell this story and play the leading parts in it,” noted the New York Times reviewer. “McPherson questions all three, and all three tell him lies.” In presentation Caspary revived what has been called the casebook method of composition: a series of testimonies, written or transcribed from speech, that recount the mystery. Sometimes those are accompanied by police reports, newspaper coverage, and other documents.

The method is identified with Wilkie Collins’ two great novels The Woman in White (1860) and The Moonstone (1868), and was taken up occasionally by others, particularly within a trial situation (e.g., The Bellamy Trial, 1929). Before Laura, probably the most famous instance of a mystery collation is Dorothy Sayers and Robert Eustace’s Documents in the Case (1930). The technique also has affinities with multiple-viewpoint assembly in “straight” fiction influenced by Dos Passos; Kenneth Fearing had tried it in his experimental novels The Hospital (1939) and Clark Gifford’s Body (1942) as well as in his crime stories Dagger of the Mind (1941) and The Big Clock (1946).

To take us through the eight days of the investigation, Caspary’s casebook assigns each character a block of narration. Each block, told in first person, has its own distinctive tenor, representing a particular subgenre of mystery fiction.

If you didn’t know the Laura mystique already, you might suspect that the opening chunk, told from Waldo’s perspective, would announce him as the brilliant amateur detective who will solve the case and surpass the plodding McPherson. Waldo is a celebrity columnist, a connoisseur of murder and lethal banter. Like 1920s detective Philo Vance, he collects art and lords it over others through aggressive erudition. Waldo writes in periodic sentences of eloquent self-congratulation:

My grief in her sudden and violent death found consolation in the thought that my friend, had she lived to a ripe old age, would have passed into oblivion, whereas the violence of her passing and the genius of her admirer gave her a fair chance at immortality.

There are even the sort of fake footnotes that we find in S. S. Van Dine and Ellery Queen novels of the 1930s, attesting to the scholarly bona fides of this dilettante sleuth.

Waldo’s power over Laura, as her patron and guru, gets expanded to a remarkable authority over the narrative in this first part. He tells us things he did not witness, chiefly the early “offstage” phases of McPherson’s investigation, and his explanation is that of the artist as god.

Waldo’s power over Laura, as her patron and guru, gets expanded to a remarkable authority over the narrative in this first part. He tells us things he did not witness, chiefly the early “offstage” phases of McPherson’s investigation, and his explanation is that of the artist as god.

That is my omniscient role. As narrator and interpreter, I shall describe scenes which I never saw and record dialogues which I did not hear. For this impudence I offer no excuse. I am an artist, and it is my business to re-create movement precisely as I create mood. I know these people, their voices ring in my ears, and I need only close my eyes and see characteristic gestures. My written dialogue will have more clarity, compactness, and essence of character than their spoken lines, for I am able to edit while I write, whereas they carried on their conversation in a loose and pointless fashion with no sense of form or crisis in the building of their scenes.

This is an extraordinary passage. It opens the very-‘40s possibility that what follows may be Waldo’s fantasy. Only near the end of his text does Waldo assert that his knowledge of McPherson’s investigation is derived from what Mark later told him one night at dinner. We will soon learn that Waldo’s opening section was written directly after that dinner, but he actually didn’t know one key fact. His omniscience is an illusion.

McPherson takes up the tale in the second part. He has read Waldo’s account and treats it as a separate piece of evidence. As we follow McPherson’s investigation, we’re in the realm of the police procedural. The register shifts too. If Waldo’s style is showoffish, McPherson’s is laconic. Whereas Waldo celebrates how his prose will immortalize Laura, McPherson admits that his version of things “won’t have the smooth professional touch.”

Actually, though, it does. It reads hard-boiled.

As we stepped out of the restaurant, the heat hit us like a blast from a furnace. The air was dead. Not a shirt-tail moved on the washlines of McDougal Street. The town smelled like rotten eggs. A thunderstorm was rolling in.

Caspary gives us the voice of the tough but vulnerable cop, the voice we would later learn to call noir. There’s an echo of James M. Cain when McPherson signals that in retrospect he was wrong to trust this femme fatale: he sourly describes himself in the third person.

She offered her hand.

The sucker took it and believed her.

McPherson’s eventual victory over Waldo is prefigured in the cop’s reflections on writing up crime. When Waldo learned Laura was still alive, McPherson says, “The prose style was knocked right out of him.” So much for Wimseyish fops set down in a Manhattan murder.

Shelby gets his voice in as well. A brief third section consists of a police transcript of McPherson’s questioning. Aided by his attorney, Shelby withdraws some lies, dodges uncomfortable areas, and generally remains the most obvious suspect—as well as Mark’s rival for Laura. At this point in the book Caspary begins to play an intricate game of knowledge, in which we get, piecemeal, information that tests the string of deceptions and evasions confronting McPherson.

In the fourth section, Laura writes her testimony. Once more the circumstance of composition is explained to us. Laura confesses that she can’t understand what she thinks and feels unless she sets it down. She has burned her old diaries, but now she has to start over.

In the fourth section, Laura writes her testimony. Once more the circumstance of composition is explained to us. Laura confesses that she can’t understand what she thinks and feels unless she sets it down. She has burned her old diaries, but now she has to start over.

It’s always when I start on a long journey or meet an exciting man or take a new job that I must sit for hours in a frenzy of recapitulation.

Now the action is that of the woman in peril, the figure familiar from Eberhart and Rinehart and Sanxay Holding. And so the stylistic register is “feminine,” tracking fluctuations of feeling and noting costume details and shades of color. Laura’s narration is also suspenseful and contemplative, dwelling on moments that seem to radiate danger—McPherson’s trick questions, Waldo’s sinister manipulations, and Shelby’s pretense that he’s protecting her rather than himself.

The emphasis is less on external behavior than Laura’s growing realization of why she has clung to two failed men. She will gradually realize that McPherson, despite his coldness, is the best match for her. Waldo is “an old lady” and Shelby is an overgrown baby. Caspary the left-winger gives these portraits the taint of class corruption. Waldo and Shelby are ghoulish creatures of the high life, while Aunt Susie is the faded, self-indulgent beauty Laura might become.

Laura’s recognition of her entrapment is rendered in a choppy, spasmodic fashion. Waldo’s, McPherson’s, and Shelby’s accounts have all been linear. Laura’s is not. It skips around in time, replays scenes we’ve seen from other viewpoints, and incorporates dreams that seem as well to be flashbacks.

This is no way to write the story. I should be simple and coherent, fact after fact, giving order to the chaos of my mind. . . . But tonight writing thickens the dust. Now that Shelby has turned against me and Mark shown the nature of his trickery, I am afraid of facts in orderly sequence.

In a narrative dynamic we find throughout 1940s fiction and film, the strong career woman is thrown off balance and succumbs to confusion. The most notorious example is of course Lady in the Dark, the 1941 play that appeared on film in 1944, the same year as the film version of Laura.

The lady returned from the dead will need a real man to rescue her. That rescue is enacted, again, in prose when McPherson reassumes control of the narrative. The book’s fifth part consists of two sections: the classic summing up and denunciation of the culprit (Waldo) and the rescue of Laura from Waldo’s second attempt to kill her. McPherson’s hard-boiled diction has won out. As Waldo is taken away in the ambulance, however, he earns a degree of purely verbal revenge. McPherson’s narration quotes Waldo’s mumbled phrases as, dying, he fills in plot points. In the process, his style gets inserted, like an alien bacterium, into McPherson’s curt passages.

McPherson, who can afford to be gallant, gives Waldo the last convoluted word. It comes in a quotation from the manuscript found by McPherson at the climax, a passage that confirmed Waldo’s guilt. In Waldo’s unfinished account, Laura is an essence of womanhood, a modern Eve; but one who continually reminded him that he could never be Adam.

During production of the film version of Laura, the makers considered mimicking the novel’s block construction. Citizen Kane had made multiple-viewpoint narration more thinkable in the 1940s. In the end, though, only Waldo’s voice-over was retained, with results that have provoked several critical comments.

The film made many other changes, large and small, but during this reading of the novel two improvements stood out for me. Making Waldo a radio commentator as well as a columnist allows a rich play of sound that comes to a climax at the film’s dénouement. Secondly, Waldo drops out of the book for many stretches, largely because Caspary is concerned to throw suspicion on Shelby and Laura. But the film keeps Waldo onscreen a lot, even permitting him (against all plausibility) to tag along with McPherson on the investigation. His waspish interjections, delivered by a suave Clifton Webb, add a nice tang, while sustaining Caspary’s theme of class snobbery. The film adds several kinks, such as introducing Waldo writing in his bathtub. The situation includes one of those how-did-they-get-away-with-it? moments when, as Waldo climbs out of the water, Mark glances scornfully offscreen at Waldo’s privates.

Caspary would go on to other successes, notably the screenplays for A Letter to Three Wives (1948) and Les Girls (1957) and several other novels that play with block construction and shifting viewpoints. But Laura would remain her prime achievement. It’s a striking novel that became a landmark film and an enduring example of how female crime novelists could stretch and deepen the conventions of popular literature.

A useful and spoiler-free biographical survey of many of these writers is Jeffrey Marks’ Atomic Renaissance: Women Mystery Writers of the 1940s and 1950s (Delphi, 2003). See Mike Grost’s inevitably encyclopedic coverage as well.

Highsmith’s disdain for pulpish style is discussed in Andrew Wilson, Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith (Bloomsbury, 2003), p. 124; my quotation above comes from p. 256. I’m grateful to Ms. Stéphanie Cudré-Mauroux of the Archives littéraires suisses for other information about Highsmith.

Some craft advice from these authors can be found in Dorothy B. Hughes, “The Challenge of Mystery Fiction,” The Writer 60, 5 (May 1947), 177-179; Charlotte Armstrong, “Razzle Dazzle,” The Writer 66, 1 (January 1953), 3-5; and Patricia Highsmith, “Suspense in Fiction,” The Writer 67, 12 (December 1954), 403-406. Millar’s discussion of Beast in View is in the International Polygonics edition of the novel, 1983, pp. 1-2, 249.

Vera Caspary’s autobiography, The Secrets of Grown-Ups (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979), is a captivating read that introduces us to a fascinating personality. (“Under the ready smiles were witches’ grimaces, beneath the padded bra a calcified heart.”) In Wilkie Collins, Vera Caspary and the Evolution of the Casebook Novel (McFarland, 2011) A. B. Emrys offers an excellent study of Caspary’s work in relation to mystery traditions. Caspary’s “official” response to Preminger’s film comes in “My Laura and Otto’s,” Saturday Review (26 June 1971), 36-37.

Hammett was no slouch at juggling proper names and pronouns either. I marvel that he could call Ned Beaumont “Ned Beaumont” all the way through The Glass Key. All the other characters are tagged with their first or last name, but this option maintains an unsettling middle distance on his psychologically opaque protagonist.

I discuss Waldo’s narration in the film version of Laura in more detail in this entry.

NIGHTMARE ALLEY: Do we hear what he hears?

DB here:

In the 1940s, American cinema turned wildly subjective. Visions, daydreams, nightmares, optical and auditory POV, inner monologues, flashbacks, and stream-of-consciousness montages were popping up everywhere. Sometimes these techniques rendered what it felt like to be the character at that moment. At other times, they were occasions for gags, or padding, or spikes of emotion, or flamboyant spectacle.

Sometimes they were just weird.

Siren song

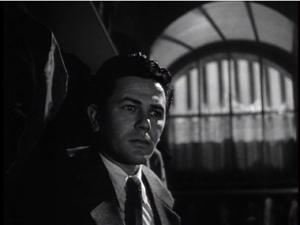

One of the most intriguing passages in Forties films comes at a climactic moment in Nightmare Alley (1947, the year I was born). Spoilers ahead.

Stan Carlisle has been involved in a complicated swindle with the help of psychologist Lilith Ritter. He has entrusted her with $150,000 in cash extracted from their mark. When the plan goes wrong, he reclaims the money and heads for the railroad station to meet his girlfriend Molly.

In the cab en route to the station, Stan discovers that the wad of cash Lilith has given him consists of 150 singles. He returns to her apartment to confront her. There Lilith suddenly goes coldly clinical, declaring that Stan is deluded. Just as he thinks he killed a man in Texas, and he has imagined that she’s involved in his swindle. She denies any collusion with him, but does hint that she could get him indicted for the killing.

Since he has been growing more anxious, her calm stream of lies unnerves him. And since she records all her sessions with her patients, she has his first visit as a confession to the Texas killing. She has been careful to never record their swindle plot.

As Stan gets more panicky, we hear a police siren. He reacts, but Lilith does not. She claims not to hear it; she says he’s just imagining it, like everything else. When she offers to take him to a hospital, he pulls away and flees, without his money.

Here’s the scene.

Is the siren objectively in the scene, or is it in Stan’s head?

Lilith says she doesn’t hear the siren, so it might be subjective, manifesting Stan’s guilty conscience. And all the psychologist’s talk about hallucinations may have induced one in him. But the siren isn’t distorted in the way most auditory imaginings are; it seems plausibly part of the story world. And many viewers (including me, on my first viewing) assume that Lilith or her servant Jane has called the police, and the cops are now arriving. Lilith could be pretending not to hear the siren in order to convince Stan he’s loco. She does tell him to stay for a sedative.

There are several oddities here besides the siren. For one thing, Jane has made her entrance keeping Stan covered with her pistol. When Stan and Jane leave the bedroom, we see Jane hovering in the background.

As Lilith comes out she cocks her head screen left, signaling to Jane, and swivels the pistol firmly toward Stan.

Once Stan and Lilith get into their argument, though, Jane is no longer seen or heard. She’s last glimpsed as a sleeve on its way offscreen.

We never see Jane definitely exit the room. Is she there or not? Did Lilith’s head gesture mean “Stand over there to keep him covered” or “Go off and call the police”? The film’s continuity script (typically a transcript of the editor’s version with dialogue and effects but without music) says only “Jane crosses and exits scene.” That could mean she leaves the room or merely leaves the frame.

Moreover, we learn from cinematographer Lee Garmes, who shot Nightmare Alley, that Goulding preferred clearly signaled entrances and exits.

He had no idea of camera; he concentrated on the actors. He had the camera follow the action all the time. He was the only director I’ve known whose actors never came in and out of the sideline of a frame. They either came in a door or down a flight of stairs or from behind a piece of furniture. He liked their entrances and exits to be photographed. I like that; they didn’t just disappear somewhere out of the frame-line as they so often do.

“Disappear somewhere out of the frame-line” is just what Jane does.

Jane’s presence or absence matters because of the quarrel that ensues. When Lilith announces her betrayal of Sam, we might expect the muscular Stan to attack her, slapping her around like the good noir sucker he is. But he meekly takes her assault. True, he’s coming apart, but maybe he’s holding back partly because Jane still has him covered from offscreen. That assumption seems validated at one point, when Stan’s nervous glance sharply off right suggests that she’s still there with her pistol. It’s after that glance that he warns Lilith not to call the cops.

Of course he could be imagining Jane in another room calling the police. On the other hand, if we assume that Jane remains offscreen, Lilith’s cool story about Stan’s breakdown becomes motivated as a performance in front of a witness who can back her up.

Maybe the handling of Jane is just clumsy direction on Goulding’s part? Or just conciseness? Still, there’s that siren. If Jane is in the room all the while, and we don’t hear her telephone the cops offscreen, the siren can’t be the result of a call for help. And it’s not clear that Lilith had the time to phone the police after Stan left the bedroom.

So maybe the siren is indeed in Stan’s head. Or if it’s objectively in the story world, then maybe it’s just a coincidence. (Chicago has plenty of sirens.) In this case, Lilith takes advantage of the siren to weaken Stan’s grip even more. A further complication: The siren cuts off as Stan flees, but there’s no indication that the cops have arrived outside. And in another oddity, we see Lilith turn slightly toward the camera when she denies hearing the sound. Is this a mark of evasion, like blinking?

In sum: The siren is either subjective or it’s objective. If it’s subjective, it’s at variance with most subjective sound of the period in not being signaled clearly as such. If it’s objective, it’s either the result of somebody calling the cops from offscreen, or it’s just coincidental.

Which is it? Usually a Forties film is pretty explicit when we’re in a character’s head, if only in retrospect (e.g., the staircase “death” in Possessed, 1947). Nightmare Alley seems to fudge things here.

When being a geek isn’t chic

Am I over-thinking this? The commentators on the Eureka! DVD, noir experts Alain Silver and James Ursini, puzzle over the siren too. I think that when Lilith denies hearing it, most viewers feel a bump: after all, we hear it too. But soon, I think, most of us take it as a real siren and assume that Lilith seizes on it as another way to convince Stan he’s breaking down. As for Jane, we just forget about her.

Look at the overall film, though, and the subjectivity possibility gains a curious strength. The siren can be taken as part of a peculiar pattern running through the film. To show you what I mean, I need to rehash a fairly complicated plot. Bear with me.

Stan Carlisle, an ambitious carnival worker, is conducting an affair with Zeena, the fortune-teller, while her partner Pete sinks into alcoholism. Stan accidentally kills Pete by giving him a bottle of wood alcohol instead of moonshine. Partnering with Zeena, Stan masters a code system for a mind-reading act. Soon he has left Zeena behind and married the carnival entertainer Molly, who becomes his confederate in a ritzier nightclub mentalist act. But Stan is plagued by memories of Pete’s death. He visits a psychologist, Lilith, to whom he tells his guilt feelings.

Stan conceives a grand scheme to turn faith healer, using his skills at illusion and fake spiritualism. (“The spook racket: I was made for it.”) He manages to deceive the rich Ezra Grindle, who asks to see his deceased lover. The scheme, in which Molly impersonates a spirit, fails and Stan has to flee, hoping to take with him the money he’s already wormed out of Grindle. Lilith blocks that in the scene I’ve excerpted.

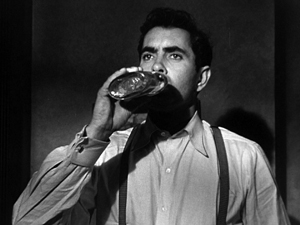

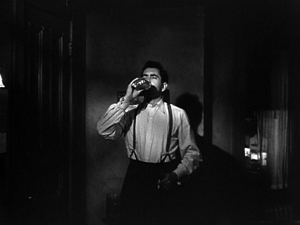

Stan leaves Molly and begins to spiral downward into drunkenness. By the film’s end he’s ready to take on the job of the geek, the subhuman carnival freak who bites heads off chickens. Originally Stan had despised the geek, but now, in order to be guaranteed a bottle a day, he declares: “I was made for it.” Only Molly’s tender concern holds out hope Stan might claw his way back.

I said the plot was complicated, but it rests on a set of fairly simple substitutions. The opening situation gives us two couples, Zeena and Pete, Molly and the strong man Bruno. Initially Stan was odd man out, paralleled by the geek (also on the fringes of the action). Stan replaces Pete as first Zeena’s lover and then her stage partner. But once Stan knows the mentalist codes, he can replace Zeena with Molly, whom Bruno surrenders. Later Zeena and Bruno will form a couple. In Stan’s rise, Molly gets replaced by Lilith, his partner in crime, if not in romance. When Stan’s swindle fails, he goes on the run, alone again. Pete was established as one step up from geekdom; without Molly, he said, he’d be a geek. Now Stan becomes the new Pete. Drinking around a campfire with bums, he even repeats Pete’s cold-reading spiel word for word and gesture for gesture, with a bottle of booze as the crystal ball.

Stan finally sinks to the bottom, willing to serve as a carnival geek for the standard bottle a day. Molly now plays Zeena to the new Pete.

The pattern of sound leading up to the siren scene centers on the geek. In the crucial scene in which Stan gives Pete the rubbing alcohol, the geek’s cries punctuate the action as he dashes around in the distance; like Pete, he needs his daily bottle. But we hear those cries three more times later, when the action has left the carnival. The cries are displaced from their original source, and more insistent on each appearance.

The first time, they’re very faint. Zeena and Bruno have called on Stan and Molly in their nightclub dressing room. Zeena has brought out her Tarot deck and seeing Stan’s future she warns him not to try the big thing he’s contemplating. (It’s the fleecing of the grieving Grindle.) Worse, her cards bring up the Hanged Man, the same card that Zeena turned up for Pete. Once the association with Pete has returned, it’s hard to exorcise.

Angry, Stan forces Zeena and Bruno out, and as he stands at the door, with the music rising, we can hear the distant cries of the geek. In the next scene, the association with Pete is strengthened. Stan is getting a massage and the smell of the rubbing alcohol reminds him of the night of Pete’s death. Now, more strongly, we hear the geek.

The motif-cluster is Pete’s death/Hanged Man/rubbing alcohol/the geek. This is brought back again, most obviously, when on his downward path Stan is holed up in a hotel room and instead of eating starts to guzzle a bottle of gin.

The compulsive drinking, along with Stan’s disheveled life, marks another stage in his conversion into Pete, and the geek’s cries are heard most plaintively now.

So what do we make of the geek’s cries in these scenes? If we take them as subjective, as Stan’s auditory flashbacks or imaginings, then the siren moment gathers a new force. If we’ve had access to Stan’s mental soundscape earlier, maybe we have it again when he “hears” the police coming. After several instances of subjective sound, we’re more prepared to take the siren as subjective too—and to wonder a bit about it even after we’ve concluded that it’s probably objectively in the scene.

That feint would be an interesting storytelling maneuver in itself. Yet other factors complicate things.

The geek goes Greek

In 1940s movies, there’s plenty of subjective sound. Often we understand that a sound is subjective by virtue of its acoustic quality; it may be given extra reverb or distorted in other ways. We also take it as subjective because the sound clearly isn’t coming from the scene. We often remember it from prior scenes and so treat it as an auditory flashback. But there are visual cues for subjective sound too. The two primary ones are a close view of the character whose mind we’re in, and an expression on the character’s face that indicates some intense feeling.

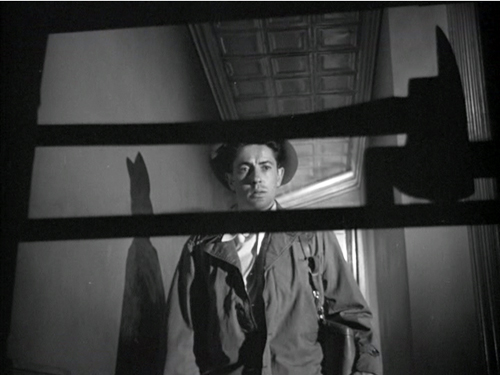

In The Fallen Sparrow (1943), Kit recalls his months in a Spanish prison chiefly through the scraping limp of one of his captors passing in the hall. When we’re given access to that acoustic memory, we get fairly close shots of Kit’s agitation.

In an interesting parallel to Nightmare Alley, when Kit is with Whitney, he thinks he hears the scraping footbeat again.

It might be a genuine offscreen sound, since we have reason to believe that his torturer has followed him to New York. (In the climax, the sound will be actual, not imaginary.) But at this point Whitney says she doesn’t hear the noise, and neither do we. This indicates that Kit is imagining it. The filmmakers faced a problem comparable to that in the Nightmare Alley scene. If the sound had played for us as well as for Kit, and Whitney said she didn’t hear it, the options are three: we’re in Kit’s head, though she isn’t; it’s real and she truly didn’t hear it; or it’s real and she’s lying (as Lilith may be). We couldn’t be absolutely sure we were in Kit’s head if the sound had been included, but when it’s not on the track, we know he’s hallucinating.

There are several norms to consider here. First, typically the close shot is timed to coincide with the subjective sound, indicating that the character registers the sound when we do. That happens in The Fallen Sparrow, but not in Nightmare Alley. We notice the siren before Stan does, which suggests that it’s objective.

Second, the shot isolating the character favors our taking a sound as subjective. But when another character is in the shot, it’s harder to construe as subjective. Accordingly, in The Fallen Sparrow, the shot that includes both Kit and Whitney inclines the filmmakers to treat the shot as objective and the sound as purely private, as inaudible to us as it is to her. In Nightmare Alley, the siren does indeed start over a close-up of Stan, but it continues over a reverse-shot of Lilith and soon enough, over a shot of the two of them.

Finally, our sense of subjectivity depends partly on the intrinsic norm each movie sets up. In The Fallen Sparrow the scraping footstep takes its place in long stretches of inner monologue which vocalize Kit’s thoughts. Because we’ve had intimate access to his mind, we’re likely to accept the footstep we hear as subjective as well. But Nightmare Alley doesn’t include inner monologues. We never access Stan’s stream of thought, so the geek cries are the only moments we might be plunging into his mind–at least, until (perhaps) the siren scene.

The siren scene hangs uncertainly between subjectivity and objectivity, tilting toward objectivity but also casting some doubts on it. What about the geek sounds? They’re even more complicated. They seem to hang between subjectivity and–well, something else.

Take the first instance. Stan is at the doorway and the camera tracks in to him as the musical score emerges. The geek noises slip in, and Stan pauses, as if reflecting.

That seems like a fairly standard cue for subjectivity: Stan has associated the Tarot cards and Pete’s death with the geek’s cries. Because of the faintness of the noise (some people seem not to notice it, as if the score nearly drowns it out), the narration might even be hinting that Stan’s memory of the night of Pete’s death is barely conscious.

In the light of the later occurrences, I’d propose another possibility. Given that we’ve never been in Stan’s head before, the sound might be more addressed to us than to him, reminding us of an association he doesn’t sense at all. This moment might almost be the film’s way of taking us aside and flagging a motif that will develop later–and in ambiguous ways.

In the rubdown scene, we see Stan, anxiously reacting to the smell of alcohol, in a fairly close view as the geek’s cries are heard.

In great anxiety, he leaps off the rubbing table. But perhaps he’s reacting just to the smell of alcohol, not to his memory of the geek. Again, the geek sounds are smoothly merged with a burst in the musical score.

Most characters who hear imaginary sounds report them to the people around them. But Stan hasn’t said anything, as far as we know, to Molly about twice hearing the geek. When Stan tells Lilith of the two earlier scenes during his therapy session, he mentions only being disturbed by Zeena and the cards, and the way the alcohol reminded him of Pete.

He doesn’t mention hearing the geek’s cries. So again we might ask if these cries aren’t subjective but rather something like a nondiegetic score–the soundtrack reminding us of something Stan isn’t remembering.

The last recall of the geek’s cries is presented while Stan is gulping gin. The noise starts in a medium shot before the camera retreats to a distant view.

If the cries make him feel tormented, he doesn’t give much sign of it. And if we were supposed to penetrate his mind, where the geek noises might reside, the camera would typically track in more tightly (as it does in The Fallen Sparrow). Instead, it withdraws, again raising the possibility that the geek’s shrieks are a commentary, not a recollection. Perhaps the cries are more like the Greek chorus warning us of an outcome to which the protagonist is oblivious.

What are we left with? Mixed signals, I think. The geek’s cries and the police siren hover in a space that many films worked within but seldom treated so freely. The cries can be taken as subjective, but they lack robust cues for that function. In other respects, they suggest expressive commentary. As the alcohol reminds Stan of Pete’s death, the cries do the same for us, while prophesying Stan’s fate. And the siren, while probably objective, makes us hesitate partly because we’re not sure the police have been called and partly because we’ve had ambivalent sound cues earlier. For a moment it might seem to be, as Lilith says, Stan’s first full-blown hallucination.

The continuity script for Nightmare Alley duly notes the siren’s sound, and the geek’s cries are noted in the scene of Pete’s death. But there’s no mention of geek cries in any of the three scenes I’ve considered. Perhaps director Edmund Goulding shot the film without planning to include the geek sounds at all. Perhaps they were added in postproduction. Someone late in the production process may have decided to anticipate Stan’s final degradation through ever more vivid echoes of the poisoning scene. Nightmare Alley would become an example of innovation by last-minute intervention.

Usually a 1940s film respects the distinctions, the either/or options, that are offered by the era’s stylistic menu. Accordingly, a sound is clearly objective or clearly subjective. But sometimes a film oscillates between the choices, or blurs the distinctions among them. We’re most familiar with this slipperiness when music shifts between being diegetic (sourced in the story space) and being nondiegetic (added to the story world “from outside”). This sort of looseness can be found elsewhere in 1940s storytelling. A film may start with one narrator and end with another, or none, or an uncertainly identified one. A flashback may never close, or loop back to its beginning without returning to the frame story. The outliers coax us to study how the ordinary cases work and note how much we take their conventions for granted.

We can learn as much about storytelling strategies from the ambivalent films as from the trim and polished ones. And in a movie called Nightmare Alley, we can’t regret that the haunting wail of the geek wafts through it as both a reminder of death and an anticipation of destiny. Its shape-shifting sound fits a movie that wants to unsettle us.

Fussbudget film analysis: I was made for it.

The continuity script for Nightmare Alley is available as a pdf file on the Eureka! DVD of the film.

Lee Garmes’ remark about explicit entrances and exits is quoted in Charles Higham, Hollywood Cameramen (Thames & Hudson, 70), 49-50. For background on the making of the film see Matthew Kennedy, Edmund Goulding’s Dark Victory: Hollywood’s Genius Bad Boy (University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), 241-252. There’s a detailed and intriguing psychoanalytic interpretation of the film at Randomaniac.

Actually, the scene in The Fallen Sparrow is a little more complicated than I indicate here, but I didn’t want to get into the weeds. The essential point holds, though: when one character thinks that a sound is veridical, and another character is present but doesn’t hear it, the filmic narration can confirm or disconfirm or ambiguate the source of the sound.

Thanks to conversations with Kristin, Jeff Smith, and Jim Healy about the film. Woody Haut’s lengthy discussion of the film for the Eureka! disc is reprinted on his website.

I discuss extrinsic and intrinsic norms of narration in Chapters 4 and 8 of Narration in the Fiction Film.

For other example of fruitful anomalies in the period, see “Innovation by accident,” “Twice-Told Tales: Mildred Pierce,” and the Laura discussion in “Dead Man Talking.”

Sometimes a reframing…

Side Street (1949).

DB here:

…just knocks you out.

“It can only be fully recommended to those who have a deep and morbid interest in crime.” Snooty judgments like this made Bosley Crowther the critical joke of generations. Today film lovers wear their deep and morbid interest in crime as a badge of honor. Especially when the crime is covered by Anthony Mann.

In Side Street (1949), Joe Norson has lost his business and works part-time as a postman while he and his wife await their first child. Having come back from war and wanting to give Ellen a good life, Joe is tempted to steal money he’s seen lying around the office of a crooked attorney. He grabs a folder containing what he thinks is a couple of hundred dollars; instead, it holds $30,000 of blackmail money. The woman who chiseled the money out of a businessman turns up dead, and the police are investigating. When Joe naively loses the money and sets out to recover it, he’s drawn into the murder, tracked by the gang, and targeted as a prime suspect by the police.

Variety and Crowther chided the screenwriters for a sketchy plot, and the complaint is somewhat fair. Joe is an unusually weak protagonist. He botches both his theft and his cover-up, leaving a trail that’s easy for the killer and the cops to trace. Because Joe is fairly passive and on the run, and he has to follow his clues in a fairly linear manner, and his schemes to fight back come to almost nothing, the action is filled out by scenes of the gang and the police tracking him.

What partly compensates for the plot’s problems is the bold location shooting. As part of the semi-documentary trend of the period (the film opens and closes with worldly-wise voice-over narration from the Homicide Captain), Side Street presents itself as a story rooted in urban reality. And indeed it is a triumph of location shooting. The characters visit a bank, Greenwich Village, Bellevue Hospital, and many neighborhoods. The final chase, with Joe trapped in a taxi with the killer and pursued by three cop cars, is a tour de force of geometrical shot designs that make city canyons part of the drama.

Mann has long been praised for integrating the forces of nature into the action of his Westerns, but this film shows his flair for cityscapes too.

Given the constraints of location filming, the freedom of Mann’s camera is all the more arresting. This time he’s not working with John Alton, the cinematographer most in tune with his baroque sense of light and framing. But Mann still gets punchy results from ace DP Joseph Ruttenberg. There is nothing quite so staggering as Alton’s framing of Claire Trevor and the cabin clock in Raw Deal, let alone the Grand Guignol imagery of Reign of Terror, but Ruttenberg does give us plenty of nicely dense compositions, exploiting the verticals and apertures available on location. There’s also a neatly discreet shot of a revolver peeking out from behind a door in distant long-shot; the shadow supplies the telltale shape.

Mann is a post-Kane filmmaker. Like nearly every Forties director of dramas, he learned from Toland and Welles that it’s fun to shove the action into the viewer’s face. The high angles of the city are counterbalanced by steep, low setups both inside and outside. Mann never met a “Russian angle,” or a ceiling, he didn’t like.

When the lens is more or less straight on, the frame can be tight and actors’ heads are packed into the frame like cantaloupes in a supermarket display.

In motion, the camera isn’t safe. Actors rush past the lens or thrust themselves straight at it.

When Joe flings himself out of a car, prepare to find yourself in the middle of traffic, with a truck rushing at you (a stunt done in real space, not against a back-projection).

Yet even studio-shot back-projections retain vigorous, immersive depth.

Mann’s visual dynamism, complete with aggressive foreground and distant depth, hits a high point in the dialogue-free scene that’s the topic of today’s sermonette. Joe hasn’t planned to steal the money, but circumstances lure him on. The lawyer’s out of his office, and the door has been left ajar. Joe earlier saw the money put into a file drawer, and as Joe prepares to slide the mail under the door, the cabinet stands temptingly in the foreground.

He impulsively heads for the cabinet, pauses before it, and then—thanks to an abrasive cut—grabs the handle violently. The drawer is locked. He recovers himself, almost grateful that he’s blocked, and he lurches out the door. No theft today, apparently.

Outside, Joe seems to be going on his way, but the long shot shows a barrier, like a railing in the foreground. It seems about as innocuous as the car hood we saw when Joe went in the building.

As Joe approaches, the camera tilts up to follow him and he stops, staring. He’s framed before what’s now revealed as a fire axe.

Another director—Hitchcock, perhaps—would have handled this with a medium-shot of Joe leaving and looking off, followed by an optical POV shot of the axe. Or you could show him leaving in the foreground, with the axe mounted in the distance; he glances back, sees it, and decides to go fetch it.

By contrast, Mann’s approach yields a sharp one-two snap: Joe approaches/ he stops. We see the axe, but almost by accident; the reframing is just following Joe’s movement. And we don’t need to see any more of the thing but its distinctive shape—its pure axe-ness given in silhouette. Rudolf Arnheim, who always advocated pictorial simplicity, would be pleased.

After a beat, in an abrupt cut, Joe grabs the thing.

He lunges down the corridor back to the office and starts to break into the cabinet. Now his violent adventure begins.

Crime I’m not so sure of, but with bodacious filmmaking like this, who wouldn’t acquire a deep and morbid interest in cinema?

It’s been too long since our last “Sometimes…” entry. For the others see: “Sometimes a shot . . .” and “Sometimes two shots . . .” and “Sometimes a jump cut…”

Bosley Crowther’s review of Side Street is “The Screen: New Crime Story,” New York Times (24 March 1950), p. 29.The Variety reviews, more or less identical, are in Daily Variety (22 December 1949), p. 3, and Variety (28 December 1949), p. 6. The Times covers the shooting of the climactic chase in “Taxi Acrobatics in Wall Street” (8 May 1949), X5.

For more on the postwar cinema’s love affair with vigorous depth staging and depth of field, see this entry on Bergman and Antonioni, this entry on Toland and depth of field, this entry on Manny Farber’s objections to Huston, this entry on dense staging, and this entry on Wyler’s staging in The Little Foxes. For much more see Parts Three and Four of our Film History: An Introduction, Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema, and Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style.

Side Street.

Dead man talking

Confidence (2003).

DB here:

“So I’m dead.”

At the start of Confidence we hear Jake Vig’s voice as we see him lying bloodied on a pavement. As the protagonist of a neo-noir, Jake recalls the classic start of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950). There Joe Gillis (an echo of gigolo?), floating face-down in a swimming pool, begins to recount his stay as a kept man of faded film star Norma Desmond. That opening has become a touchstone for the grim fatalism of film noir, as well as a mark of daring screenwriting. The guy telling the story is dead! How cool is that?

Anybody interested in how films tell stories has to be interested in narrators, those figures—either mere voices or tangible characters—who recount, recall, or replay the story action. And anybody interested in Hollywood film knows that such narrators are hallmarks of a giddy period of cinematic innovation, as recognizably “1940s” as flashbacks, moody subjective sequences, and twisty plots. In that era we find narrators well outside that terrain known as noir. Romantic dramas, family sagas, comedies, Gothics, musicals, and other genres made ample use of voice-over commentary, and it didn’t always suggest a doom-laden atmosphere.

Still, dead narrators seem to be pushing things. They flout realism (How can a dead person tell anything?) and they raise problems of logic (To whom is this person speaking?). Is it a chatty corpse (Wilder originally wanted a morgue opening introducing Gillis) or an ethereal spirit divorced from the dead body?

Dead narrators turn up surprisingly often in the 1940s. During this period, as I’ve argued on this site and in the book I’m working on, many storytelling techniques we take for granted coalesced. There emerged a rough menu for handling them, and ambitious filmmakers played with several possibilities. That play didn’t stop in the Forties; we still have new versions of flashbacks, subjectivity, and the like. So let’s look at posthumous narrators in the Forties, with some glances at a trio of more recent efforts.

As a non-dead and highly reliable narrator, I must warn you of spoilers ahead.

Guiding spirits

The Human Comedy (1943).

Most simply, posthumous narration can be motivated as letters (Letter from an Unknown Woman) or diary entries (Thatcher’s journal in Citizen Kane). Similarly, Heaven Can Wait (1943) gives us a dead man explaining episodes from his life to an inquisitive official in the afterlife. The more flagrant cases, however, involve dead narrators who recount the entire film we see in voice-over, as in our prototype Sunset Boulevard. Knowing that the protagonist is dead at the start shifts our attention to how he or she will die.

Posthumous narrators go back a fair bit. In literature, Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology (1915) presents the ruminations of the town dead, in the manner of the cemetery climax of Our Town (1938 play, 1940 film). Wilfred Owen’s poetic monologue “Strange Meeting” (1918) presents soldiers reuniting in Hell, ending with the poignant line, “Let us sleep now….” Addie Bundren, the dead mother of Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying (1930), narrates portions of the novel from her coffin. In a pulpish pastiche of Faulkner, Kenneth Fearing’s mystery novel Dagger of the Mind (1941) includes a chapter narrated by a man who’s been murdered. Radio drama also included voices from the beyond. Examples include “Ghost Ship” (1940), with a victim recounting his own murder, and Norman Corwin’s “Untitled” (1944), which reveals the narrator to be a dead soldier.

In film, World War II brings forth the prospect of dead servicemen returning to tell their tales. “I am Matthew Macauley,” says a face superimposed over imagery of radiant clouds. “I have been dead for two years. But so much of me is still living that I know now that the end is only the beginning.” This is indeed a beginning, of The Human Comedy (1943). Having died in the war, Matthew will guide us back to his hometown and his household’s daily routines.

Matthew’s voice-over goes on to introduce his family members, including son Marcus on duty in the army. After a scene in which a spectral Matthew joins his wife at her work, his voice discreetly retires. It recurs only twice before he and his now-dead soldier son faintly enter to watch the family welcome their new member, Marcus’s pal Toby.

“You see, Marcus, the ending is only the beginning.” Matthew’s address to us has become piece of fatherly advice.

The dead narrator of The Human Comedy never intervenes in the action on earth, but an all-seeing intelligence exercises more authority in The Seventh Cross (1944). Seven prisoners escape from a concentration camp, and Ernst Wallau’s narration launches the film. During the escape sequence he rapidly introduces each of his comrades.

Fairly soon all but one are captured and executed on crosses planted in the prison yard. The first man to be crucified is Wallau, our narrator. After he is killed, his voice-over continues: “I was dead. I could see.”

Wallau’s commentary chiefly follows his friend George Heisler, who manages to elude the Gestapo while the other escapees are found and killed. Wallau’s narration continues through the film, chronicling not only the fates of the other men but probing Heisler’s state of mind. Wallau tells us what Heisler is thinking, guides us into his memory, notes things that Heisler has forgotten, and even informs us what other characters will do in the future. Confronted with this numb, almost mute character, we need the continual commentary of Wallau to give access to his inner life.

Wallau is that rare voice-over narrator who flaunts his omniscience. Being dead, he has total access to our world and can witness anything happening there. Despite Wallau’s godlike power, in good Hollywood tradition his narration attaches itself chiefly to Heisler. But here that restriction reflects simply Wallau’s foreknowledge, signaled at the start, that only Heisler will survive. The question becomes: How?

The answer comes through Wallau’s goading Heisler to find faith in others. At the start, Heisler is close to despair, and his flight stems from sheer instinctual survival. At the film’s midpoint, all his comrades have been killed, and Wallau’s long-term escape plan has failed. Heisler can’t any longer mechanically follow his mentor’s instructions. He must forge a new goal, seize the initiative, and learn to trust people. He must learn what Wallau told him from the start: there remain traces of humanity in Germany.

As Heisler’s hopes grow and his network of allies expands, Wallau’s prodding voice-over subsides. It reappears near the end, at the moment Heisler realizes how much he owes others. Heisler speaks of his debts, and Wallau murmurs in antiphony the names of those who have helped him, including some Heisler has never met.

Now that Heisler has joined the struggle with full commitment, Wallau can vanish. “Goodbye, George Heisler. I can leave you now.”

Ghostly narrators like Wallau and Matthew Macauley call to mind the nosy angels and spooks of so many 40s films. Those have their counterparts in radio dramas like “Good Ghost” (1948) and the parodic mystery novel Dead to the World (1947), with a dead detective narrating his efforts to solve a case.

As usual, a lot depends on timing of information. If we learn that the narrator is dead at the start, as in the films just mentioned and in Scared to Death (1947), a certain amount of the action can seem foreordained. Alternatively, there can be a surprise. Radio plays, it seems, tended to reveal their dead narrators as a twist ending. With less fanfare, a film can simply seem to forget the opening commentary. The Gangster (1947) is initially narrated, without a frame situation, by the crooked protagonist. As a result, we expect him to survive. Yet he dies in the course of the action. The filmmakers faced a problem: To return to the narration at the end or not? To revive his voice-over might suggest that he endures in some supernatural realm. Instead, an impersonal external voice takes over to balance the opening.