Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

How he (mostly) got away with it: Matthew H. Bernstein on Preston Sturges

DB here:

Matthew H. Bernstein is a long-time friend and a superb scholar. His biography of Walter Wanger has become a classic of Hollywood business history, and his many books and articles have refined our sense of American cinema. When we learned of his research into Sturges (a favorite of this blog), we were happy to propose that he do a guest entry. Here’s the lively, trailblazing result.

How should films portray sex and marriage? Hollywood’s Production Code, established in 1930, set forth some definite ideas.

Sex

The sanctity of the institution of marriage and the home shall be upheld. Pictures shall not infer that low forms of sex relationship are the accepted or common thing. . . .

Scenes of Passion

They should not be introduced when not essential to the plot.

Excessive and lustful kissing, lustful embraces, suggestive postures and gestures, are not to be shown . . .

Seduction or Rape

They should never be more than suggested, and only when essential for the plot, and even then never shown by explicit method.

They are never the proper subject for comedy.

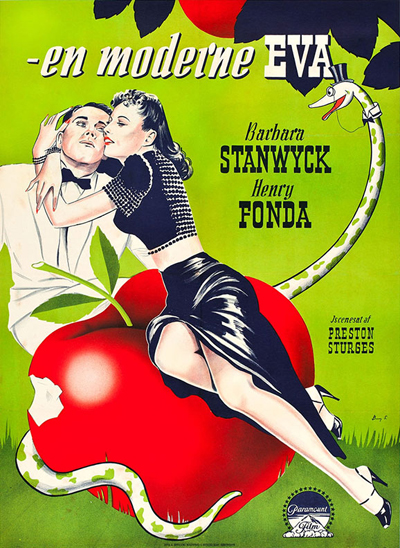

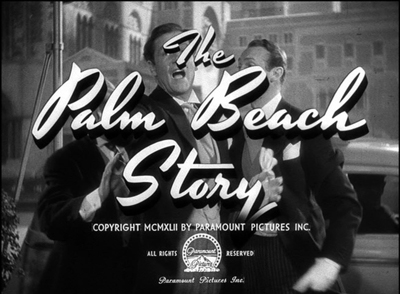

Those of us who savor Preston Sturges’s great romantic comedies of the 1940s—The Lady Eve (1940), The Palm Beach Story (1942) and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944)—admire them in part for their violation of just about all these tenets. They are full of “suggestive postures” like the lengthy chaise longue scene in The Lady Eve. Their central topic is often the seduction of men by women (The Lady Eve, The Palm Beach Story and arguably Miracle). References to extra-marital sex, contemplated or accomplished, abound. And all three films ridicule “the sanctity of the institution of marriage” into the ground. Film critic Elliot Rubinstein once observed, “If Sturges’s scenarios don’t quite invade the province of the flatly censorable, they surely assault the border outposts, and some of the lines escalate the assault into bombardment.”

The Production Code Administration, on paper and in practice, was particularly obsessed with regulating the depiction of female sexuality on screen. Yet Sturges’ attacks on conventional morality are launched by heroines: con artist/card sharp Jean/Eve (Barbara Stanwyck) in The Lady Eve, the hard-headed Gerry Jeffers (Claudette Colbert) in The Palm Beach Story and the naïve man-bait Trudy Kockenlocker (Betty Hutton) in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek. They are all variants of what Kathleen Rowe has called the “unruly woman,” characters who create “disorder by dominating, or trying to dominate, men,” and being “unable or unwilling” to stay in a woman’s traditional place. Mary Astor’s much-married Princess Centimilia/Maude in The Palm Beach Story deserves an honorable mention here too.

True, by each film’s conclusion, the Sturges heroine agrees to get or stay married. She fulfills the conventions of romantic comedy and the stipulations of the PCA. Yet in each film the path to a proper end looks so much like a roller-coaster ride that the significance and sanctity of marriage come to seem ridiculous.

How did Sturges get away with so much? A look behind the scenes at the negotiations around The Lady Eve can help us understand his strategies. It also shows that the Code was more flexible and fallible than we often realize.

Convolutions in the Code

Sturges had one advantage at the outset. He worked in a genre that was already testing the limits of the Code. Granted, the PCA in 1934 aimed to regulate film content in every genre. None, however, flaunted, even parodied, the strictures of the Code more thoroughly than screwball comedy did. Rubinstein puts it well: “The very style of screwball, the complexity and inventiveness and wit of its detours around certain facts of certain lives, the force of its attack on the very pieties it is pledged to sustain, cannot be explained without recognition of the censors. Screwball comedy is censored comedy.“

By the end of the 1930s, filmmakers were pushing hard against censorship. Romantic comedies were growing more risqué by the month, as shown by 1940 releases like My Little Chickadee, The Philadelphia Story, The Road to Singapore, Too Many Husbands, The Primrose Path, Strange Cargo, and most especially, This Thing Called Love. A sort of arms race took place, and Sturges, emerging as a writer-director in 1940, benefited from this escalation.

Just as important is a fact that many fans of Hollywood still don’t realize. We like to think that daring filmmakers were charging boldly against an iron wall, with chief censor Joseph Breen and his associates setting forth implacable demands. But the administration of the Code was not a mechanical, totalitarian affair. It was most often a matter of negotiation.

Releasing Hollywood’s product, even risqué films, benefited all parties involved. If the Code were enforced with absolute rigidity, the industry would suffer. Some films would have to be abandoned. Then urban audiences would have found the safely released product pallid, and critics would have complained about bland output. Then as now, edginess sold, and at least some audiences were eager for it.

Accordingly, Breen and co. recognized that the Code could not be applied ruthlessly. Indeed, historians Lea Jacobs, Richard Maltby and Ruth Vasey have shown that the PCA, like its forerunner the Studio Relations Committee, often helped filmmakers find ways around the most stringent policy demands. Through a give-and-take, censors and filmmakers could settle on scenes and lines of dialogue that could avoid public outcry. No one flaunted and taunted the PCA as well as Sturges, yet Breen and co. often helped him find ways of rendering suggestive situations without baldly transgressing the Code.

One typical filmmaker/PCA tactic that favored Sturges was an appeal to ambiguity. Far from being inflexible, the staff recognized that not every viewer picked up on a lewd line or suggestive situation. Some viewers would find no innuendo in a sexually-charged scene. (The 1940s critic Parker Tyler referred to this as “the Morality of the Single Instance.”) For example, in The Lady Eve, there’s a fade-out from Charles’s and Jean’s passionate embrace in the bow of the ship at night to the fade in of the ship’s prow slicing through the ocean the next morning.

That passage would suggest to the naïve viewer that they kissed for a while and went to their cabins separately. After all, in the morning we find Jean getting dressed in her stateroom and talking with her father. Then we see Charles on deck alone, waiting for Jean.

But the sophisticated viewer would understand that the earlier fade-out indicated what Joseph Breen routinely called “a sex affair.” (The ocean spray on the fade-in could be seen as a very subtle extra touch.) Crucially, Jean’s later statement to Hopsy after she is unmasked as a cardsharp sustains both readings. “I’m glad you got the picture this morning instead of last night, if that means anything to you . . . it should.” When self-regulation was well-calibrated—and this was a moment-to- moment, scene-by-sceene, film-by-film achievement—there was wiggle-room that would let innocent viewers remain innocent while letting sophisticated viewers feel sophisticated.

Apart from the increasing eroticism in screwball comedy and the willingness of the PCA to work with filmmakers to allow double layers of meaning, Sturges benefited from good timing. During this period, Breen grew more permissive in his application of the Code. He never explained why, but the late-1930s bombardment of questionable material was probably one cause. Breen was pretty exhausted after seven years of trying to accommodate the filmmakers’ increasingly outré ideas. He was so tired that he temporarily resigned in Spring 1941.

Sturges’ circumvention of the Code also depended on his personal qualities. Clearly he was a persuasive negotiator. The PCA correspondence shows Breen and his successor, Geoffrey Shurlock, rescinding countless directives they initially gave him to eliminate dialogue lines or bits of action. It’s likely that the PCA admired Sturges’ comic gifts and thus gave him greater room to maneuver than other directors enjoyed. (Much the same thing happened when the Studio Relations Committee had given leeway to Ernst Lubitsch prior to 1934.) Sturges also employed a tactic of overkill. In his scripts and in the scenes as finally staged and shot, he created so many potential infractions of the Code that to challenge each one would reduce the film to rubble, or reduce Breen and co. to stress-induced madness.

Still, Sturges played the PCA game. His convoluted plots stuck to the letter of the Code, always finally coming down on the side of pure romance and happy marriage. But they wreaked havoc with its spirit—often with the PCA’s sanction. By the premiere of The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, Sturges was relentlessly mocking the PCA’s regulations. It’s likely, I think, that the PCA was for the most part in on the joke.

After negotiations, which grew more elaborate with each title, each Sturges romantic comedy received a seal. The films made it through partly because of the PCA’s quixotic mandate, partly because the Code’s requirements had been loosened, and partly because of Sturges’ extraordinary skill in exploiting the Code. These are the crucial reasons Sturges got away with it. Along with his prolific comedic imagination, he was often aided by the very body that was supposed to be censoring him.

Once the Sturges film was released, the PCA staffers could wearily pat themselves on the back for a job well done. Yet critics’ reviews, complaints from state censor boards, and letters of protest from ordinary viewers indicate that the agency often badly misjudged how the films’ moral tone would be received. The PCA’s dual mandate—to try to give filmmakers the maximum freedom to create risqué situations but at the same time to uphold the Code–was a tightrope walk. With Sturges and other filmmakers, the agency lost its balance. Sometimes the PCA didn’t diminish the sexual dimensions enough, and sometimes the agency did not even notice elements that could give offense.

There were signs already, in the reaction to the 1940 burst of sexier films like The Primrose Path and This Thing Called Love. Local informants had asked MPPDA attorney Charles C. Pettijohn, “Doesn’t Mr. Hays have any influence with the producers any more, and has that fellow Breen out there killed himself or has he just been compelled to walk the gangplank?” Unlike the PCA staff, who had worked day by day to tone down an audacious script and had faced the charms of a persuasive filmmaker, local censorship boards reacted solely to a finished Sturges film. They merely saw what was on the screen. Many did not like what they saw.

Up the Amazon for a year

The PCA correspondence concerning The Lady Eve is surprisingly brief. Before the film was completed and a seal was granted, Breen sent only two letters to Luigi Luraschi, Paramount’s liaison on censorship. They strikingly illustrate how cooperative Breen could be when it came to scenes regarding illicit sex.

When he read Sturges’s first complete script of 7 October 1940, Breen had objections to many “questionable lines of dialogue.” Breen warned Sturges and Luraschi against anything “suggestive” in the scene between Muggsy and Lulu as they say their farewells before departing the expedition. In this brief exchange, Mugsy stiffly tells her “So long, Lulu…I’ll send you a post card” as she demurely (looking down) places a lei over his neck. This brief exchange directly undercuts Hopsy’s just-spoken, high-minded farewell to the Professor: “This is the way I’d like to spend all my time…in the company of men like yourselves…in the pursuit of knowledge.”

While it’s difficult to imagine Muggsy as a sexual partner to anyone, the woman’s downcast face and her gift of a lei could be seen to suggest her heartbreak.

Jean’s later, rapid-fire description of Hopsy’s many female admirers in the Main Dining Room of the S.S. Southern Queen originally contained comments about women who were “a little flat in the front” or “a little flat behind. ” These were cut because they were too physiologically specific about the female form. We hardly miss them, as Jean was permitted to deliver plenty of color commentary, as she detailed the women’s futile attempts to attract Hopsy’s attention.

However, Breen wrote the word “in” alongside certain demands he had made for eliminations in his 9 October letter, indicating that Sturges and Luraschi had persuaded him to relent. For example, Breen eventually accepted this exchange from Jean and Charles’s first evening together. Charles has suggested they go dancing:

Jean: Don’t you think we ought to go to bed?

Charles (after a pause): You’re certainly a funny girl for anyone to meet who’s just been up the Amazon for a year.

Jean: (after a pause): Good thing you weren’t up there two years.

Breen’s next letter (21 October) on Sturges’s revised script expressed satisfaction with all the changes made, noting that Jean’s line about heading to bed “will be delivered without any suggestive inference, or reaction.”

In the finished film, there is nothing arch about Stanwyck’s thoughtful, almost parental delivery of the first line, spoken as she looks straight ahead and then looks down to stub out her cigarette before she turns to face Charles. Likewise, her delivery of the second line is wry and mildly mocking yet almost compassionate. Still, the connotation remains that Jean is suggesting they sleep together. Instead, the couple proceeds to Charles’s cabin to meet his snake Emma.

Breen was particularly concerned about other allusive dialogue. At the Pikes’ party, Sir Alfred (Eric Blore) explains to Charles a fictionalized version of Jean’s family history which resulted in the existence of two sisters, one a lady, one a cardsharp. (Sir Alfred will later describe this as “Cecilia or the Coachman’s daughter, a gaslight melodrama.”) Breen insisted that Sir Alfred’s tale include a line indicating that Jean’s mother divorced her elderly earl before taking up with the groom “Handsome Harry” and giving birth to Jean. That way Jean’s birth would not seem illegitimate. Sturges obliged. Yet he somehow persuaded Breen to retain this later portion of the Alfred-Charles exchange, also alluding to an adulterous affair.

Charles: They [Jean and Eve] look exactly alike!

Sir Alfred: We must close our minds to that fact…as it brings up the dreadful and thoroughly unfounded suspicion that we must carry to our tombs, you understand…as it is absolutely untenable…that the coachman, in both instances…need I say more?

Why did Breen let Sturges keep in this suggestion that Handsome Harry was the biological father of both sisters, perhaps as the result of adulterous affairs? It is hard to say. True, the offending line concerns a “suspicion” voiced by Sir Alfred, rather than a fact. But Charles immediately affirms its likelihood: “But he did, I mean, he was, I mean…” before being shushed for the nth time by Sir Alfred. Here again, Breen consented to Sturges’s use of questionable material.

Breen’s greatest objection in his initial letter concerned pp. 70-74 of the first submitted script, which suggested “a sex affair.” “Inasmuch as this is treated without the proper compensating moral values, it is in violation of the Production Code, and will have to be eliminated entirely from your finished picture.”

The offending pages outlined a scene between Charles and Jean set on the deck of Jean’s cabin at the end of their first evening together. Just previously, Jean has caught Charles and her father the Colonel (Charles Coburn) playing double or nothing. Charles would then be called away to receive from the ship’s purser the incriminating photo of Jean, the Colonel and Gerald. Charles would then return to the gaming room table and the dialogue exchange with Jean about all women being adventuresses. Then Charles would ask Jean if they can go down to her cabin. There, Charles lights Jean’s cigarette; he “struggles to say something” but Jean tells him, “Kiss me,” and he obeys. (“He crushes her in his arms” as she “sinks back against the chaise longue.”) The film would then cut to a shot of the rail of Jean’s deck and of “the moonlit water beyond. A lighted cigarette arcs over the rail and down into the water. FADE OUT.”

This version presents Charles sleeping with Jean even though he knows from the purser’s photograph that she’s a cardsharp. As Brian Henderson notes, this arrangement of events would make Charles a cad, far worse than the hypocritical prig that he is in the finished film. Sturges eventually solved the problem by having Charles learn of Jean’s duplicity on the morning of their third day together at sea. But before Sturges made this change, Breen’s October 9 letter directed that Charles could not speak the line about going down to her cabin; that the scene could not play out on Jean’s private deck; and that “it would be better to have the embrace with the couple standing up.” The shot of the cigarette thrown over the railing also “should be omitted, on account of its connotations.”

In response, Sturges watered down the offending scene of passion and relocated it to the bow of the ship, where (in a reworking of a scene he had always envisioned) Charles recites his “I’ve always loved you” speech and they eventually embrace as the scene fades out. This created the PCA-approved ambiguity about what transpired sexually between them.

Here, Sturges’s solution to a problem of plot and characterization went hand in hand with the double-meaning practices of the Production Code. Sturges must have written the passionate private deck scene knowing full well that Breen would demand its elimination or transposition. His immediate agreement to revise it was likely a bargaining ploy to earn Breen’s goodwill to bank against other PCA objections.

When Sturges cut the cabin deck setting and the prone postures of pp. 70-74 from the first submitted script, he also saved a crucial part of Jean and Charles’s penultimate exchange as they enter Jean’s cabin.

Charles: Will you forgive me?

Jean: For what? Oh, you mean…on the boat…the question is, will you forgive me?

Although Breen accurately predicted that this bit of dialogue would “probably be acceptable” if the earlier scene “is cleaned up,” for now, Breen stated that their exchange had to be cut “by reason of its reference to the aforementioned sex affair.” In other words, Breen, not unreasonably, read Jean and Charles’s dialogue as referring only to their sleeping together, rather than to everything that transpired between them on the S.S. Southern Queen, including Jean’s duplicity and Charles’s narrow-mindedness. Forgiveness is of course a key issue in the drama of The Lady Eve.

Hix Nix Sexy Pix

The MPPDA issued its seal on 26 December 1940. Released in mid-March 1941, The Lady Eve passed the censors without cuts in Chicago and the states of Massachusetts, New York and Virginia. However, Kansas, Maryland, Ohio and Pennsylvania were a completely different story.

Some local censors demanded deletions of elements Breen had highlighted. Ohio and other localities objected to Sir Alfred’s dialogue about the fantasy fatherhood of Jean and Eve (“as it is utterly untenable that the coachman in both instances. . . .”). But most of the eliminations concerned elements Breen and his team had not commented upon. Among these were (again for Ohio, initially) Sir Alfred’s summary recap of the tale to Jean the next morning: “So I filled him full of handsome coachmen, elderly Earls, — young wives, and the two little girls who looked exactly alike.”

Other targets were Jean’s wisecracks. When Jean and Charles return from her stateroom after changing her shoes, the Colonel archly comments, “Well, you certainly took long enough to come back in the same outfit.” Jean’s reply–“I’m lucky to have this on. Mr. Pike has been up a river for a year”—offended Pennsylvania. Ohio objected to Jean’s comment, “That’s a new one, isn’t it?”, when Charles invites her into his cabin to see Emma.

Yet another instance concerned Charles’s exchange with Eve during their wedding night train ride. He is asking about her previous marriage to Angus.

Charles: When they brought you back, it was before nightfall, I trust.

Jean: Oh, no.

Charles: You were out all night?

Jean: Oh, my dear, it took them weeks to find us. You see, we’d make up different names at the different inns we stayed at.

Though Jean and Angus were married, the implication of using false names at a hotel (which Sturges would recycle for Trudy and her unknown husband in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek) was the deal-breaker for Ohio. Of course, one possible connotation of Eve’s many pre-Charles couplings is that not all of them were marriages. (If they were, this imaginary Eve is an early version of the Princess in The Palm Beach Story, another figure who satirizes conventional marriage.) Yet Breen’s only comments on this scene concerned Eve’s nightgown and particularly the scene’s blocking—that Eve’s revelations of her previous marriages occur away from the bed and that the bed be deemphasized throughout the scene.

Sturges must have made the case that there was no room to have the actors sit elsewhere. Meanwhile, Breen was distracted from what Jean was saying by where she was when she said it.

Local censors were most keenly opposed to two other scenes that Breen had ignored. Both take place in Jean’s stateroom.

In the first, Charles replaces Jean’s broken shoe. In one twenty-second two-shot, he kneels down to slip the shoe on her foot; looks over her foot and slowly looks up her leg all the way to her face; expresses his hope that he didn’t hurt her when she tripped him in the dining room; and then on his way to looking down at her leg and foot again, pauses momentarily but very definitely, on her décolletage. Then he looks back up at her again. There is no dialogue to distract the viewer from what Charles is looking at.

Oddly, no censors objected to this very suggestive shot; instead they focused on what ensued. Ohio, Kansas, and Maryland joined Pennsylvania in demanding the elimination of what the last described as the “semi close-up view where [Charles] allows his eyes to pass up and down over her.” This was a quick POV series of shots in which (1) Charles struggles to look at Jean; (2) Jean appears blurry and asks Charles if he’s all right; and (3) Charles, after swallowing, struggles to reply in the affirmative.

Charles is so “cockeyed” from Jean’s perfume that when they eventually stand up, he can make only the weakest attempt to kiss her, which Jean easily repulses. To the censors, however, the combination of close shot scale, physical intimacy, and intoxication (even from perfume) was intolerable–too expressive of Charles’ rising desire. I suspect they actually conflated the lengthy take and the medium close-ups (no “looking over” occurs in the point of view sequence). In any case, censors had seldom seen such “looking over” shots since the early 1930s.

In addition, all four offended states were roused by the famous chaise longue scene. As Charles tries to apologize for scaring Jean with his snake Emma, she holds him close, runs her hands through his hair, tickles his ear, and breathes heavily in his face. Taking the key elements of the shoe-replacement business to another level, the erotic hilarity of this scene arises from the complete power of Jean’s spell over Charles and their sheer proximity, in two long takes (one lasting 36 seconds, and then a closer, three-minute and fourteen-second shot). During all this time, Jean won’t let Charles kiss her, but their faces are close together and their lips are never far apart. For some censors, the most provocative elements of the scene resided in the dialogue that begins with Charles’s fall to the ground ands run through his “accompanying indecent action” (Pennsylvania again) of pulling down Jean’s skirt.

Pennsylvania also cut Jean’s sigh of anticipatory orgasmic release after describing her first encounter with her future husband: “And the night will be heavy with perfume and I’ll hear a step behind me and somebody breathing heavily and then – Ohhhhh!”

Ohio originally wanted the entire scene deleted, starting with Jean’s command “Oh, come over here and sit down beside me” through their final exchange:

Jean: Oh, you’d better go to bed, Hopsy. I think I can sleep peacefully now.

Charles (adjusting his bow tie): Well, I wish I could say the same.

Jean: Why, Hopsy!

Industry representatives negotiated with the Ohio and Pennsylvania boards to try to reduce their demands; Pennsylvania was unmoved, but Ohio was persuaded to let all but their final exchange remain in the film. An outraged San Antonio Amusement Inspector articulated the boards’ thinking when she cut what she called the film’s two “prolonged scenes of passion” in Jean’s stateroom. These, she pointed out to Breen, violated Section 2 of the Code, about “suggestive postures and gestures” and seduction being used for comedy. So in San Antonio, as in Pennsylvania and Kansas, viewers missed the bulk of two of the most celebrated comic scenes in American film history.

With The Lady Eve, Breen’s instincts were generally astute. He had advised against Sir Alfred’s sketch of the Handsome Harry plot. He had eliminated the overt sex affair scene in Jean’s cabin. Yet he missed many elements as well. Besides those stateroom scenes cut by state and city censors, there were ostensibly innocent lines. As Charles searched for a new pair of shoes, Jean says, “See anything you like?” and leans back with a bare midriff.

The constantly repeated phrase “been up the Amazon for a year” references Charles’s extended sexual privation and naivete, which make him susceptible to Jean’s wiles. But the phrase can also be taken as evoking female anatomy itself. The neglect of these details resulted from Breen’s increasing tolerance and his equally increasing tiredness. We’re lucky he left them in.

Upping the ante

The negotiations over The Palm Beach Story and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek followed the pattern set by The Lady Eve. The writer-director proposed increasingly outlandish scenarios; Geoffrey Shurlock and Breen again demanded an increasinglyu longer list of changes across a longer series of letters. Sturges alternately made cuts or assured them he could handle the material.

Once more, certain moments wound up offending local censors. For The Palm Beach Story, released in late 1942, only New York and Kansas passed the film without eliminations. Elsewhere, many of the suggestive elements that Shurlock had criticized were cut. One was Gerry’s line—describing how Tom sees her after many years of marriage–as “just something to snuggle up to and keep you warm at night, like a blanket” (Pennsylvania). Another was the first vertebrae-kissing scene in which a very drunk Tom breaks down a very drunk Gerry’s resistance to having sex.

Other deletions concerned details that had escaped Shurlock’s notice: Pennsylvania removed the underlined portion of Gerry’s explanation to Tom, after the Wienie King’s visit and munificence, of “the look” women get from men: “From the time you’re about so big, and wondering why your girl friends’ fathers are getting so arch all of a sudden – nothing wrong – just an overture to the opera that’s coming.” Even after many changes to her dialogue, scenes with Princess Centimilia could have provoked bans or major cuts. After all, she is followed around by her gigolo Toto (Sig Arno) and (in an ironic adherence to the Code’s demands) marries purely to legitimize her sexual impulses. Yet in part because of Mary Astor’s frantic line delivery, her scenes were retained. Overall, relative to its many potential offenses, The Palm Beach Story faced surprisingly minimal objections.

The entire premise of Miracle and the ensuing action mock the notion of marriage’s sanctity from multiple angles. Breen, the American military, and the Legion of Decency examined the film minutely before it was issued a seal, and many changes were made. For this reason, only one state board (Kansas) cut one line of dialogue: Trudy’s comment that “Some sort of fun lasts longer than others.”

Still, there was much to offend audiences and censors in the completed film. For example, the MPPDA and Sturges received numerous letters of complaint linking the film to the growing problem of juvenile delinquency. One viewer in Minneapolis wrote that the film showed it to be “a subject for slapstick and high comedy, especially if the delinquent is unusually fruitful. . . . My boy thought she must have passed the night with 6 soldiers or sailors. . . . In Hollywood I understand you can get away with despoiling young girls and morals don’t exist except for yokels. Do you have to spread that poison?” Given the growing panic over what was seen as a national JD epidemic, Paramount’s delay in distributing Miracle—it was completed in Spring 1943 but released in January 1944—exacerbated the controversy.

Upon reviewing The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, James Agee famously stated that “the Hays office has been either hypnotized …or raped in its sleep.” The same might seem to be true of The Lady Eve and The Palm Beach Story, but this was manifestly not the case. There were elements that the PCA didn’t catch–suggestive postures and dialogue, scenes of seduction–because Sturges created so many and whisked them by so swiftly. But he got away with it for other reasons as well. The PCA helped steer Sturges to finding ways of modifying the most brazenly unacceptable material. The standards of acceptability were expanding, controversially, and they would continue to do so. Meanwhile, the response of local censor boards and individual audience members provides crucial evidence of how at times the PCA succeeded and at other times it failed to suppress material that might offend. Knowing this history can only deepen our appreciation of what the Sturges comedies achieved.

This entry is a revised version of a portion of an article that appears as “The edge of unacceptability: Preston Sturges and the PCA” in Refocus: The Films of Preston Sturges, editors Jeff Jaeckle and Sarah Kozloff, forthcoming from Edinburgh University Press. Primary sources include Sturges’ correspondence and the PCA files housed at the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Beverly Hills. The Lady Eve and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek files are available on microfilm in MLA, History of Cinema: Selected Files from the Motion Picture Association of America Production Code Administration Collection (Woodbridge, CT: Primary Source Microfilm, 2006).

I’ve also drawn on these published sources: David Bordwell, “Parker Tyler: A suave and wary guest”; Brian Henderson, Five Screenplays by Preston Sturges (1986); Diane Jacobs, Christmas in July: The Life and Work of Preston Sturges (1994); Lea Jacobs, The Wages of Sin: Censorship and the Fallen Woman Film (1997); Kathleen Rowe, The Unruly Woman: Gender and the Genres of Laughter (1995); and Elliot Rubenstein, “The End of Screwball Comedy: The Lady Eve and The Palm Beach Story,” Post Script 1, no. 3 (Spring-Summer 1982), 33-47.

Watch those hands; or, Burt, Jean-Luc, and Bill come to Cinephile Summer Camp

Nouvelle Vague (1990).

DB here:

At this year’s Summer Film College in Antwerp, Peter Bosma pointed out that the event seems to be a unique mixture.

Films are screened from morn to midnight: this time, 38 films across 6 days and two half-days. But it’s not exactly a film festival, as there are no new releases.

So is it like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato? Not exactly. While the shows included some restored titles (notably the Belgian Cinematek’s pretty makeover of Pollyanna, 1920), the films were mostly original prints with an occasional DCP.

So is it like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato? Not exactly. While the shows included some restored titles (notably the Belgian Cinematek’s pretty makeover of Pollyanna, 1920), the films were mostly original prints with an occasional DCP.

Moreover, the films cluster around two or three major themes. This year we had Late Godard (fourteen titles, counting episodes of Histoire(s) du cinema) and the career of Burt Lancaster (eleven). In addition, there were nightly showcases called “Masterworks in Context,” which included one surprise film, title undisclosed. But unike most movie marathons, the Summer Film College introduces screenings with lectures and discussions. This year there were fourteen sessions, each running about ninety minutes. These are serious, intensely informative talks—very far from the usual brief introductions one gets at festivals or in art house warm-ups.

So is it an educational enterprise? Definitely, but without assignments, tests, or grades. It’s designed to serve Flemish-speaking professors and students, but also civilians who are just interested in a weeklong package of film and film talk. The event helps forge a community of film appreciation.

Finally, there’s often a guest filmmaker on hand, usually related to the main threads. This time it was Bill Forsyth, who directed Burt in Local Hero. That film was screened, along with Bill’s wonderful Housekeeping.

So what would you call the College? I once called it Cinephile Summer Camp, and that still seems accurate in evoking the sense of fun and camaraderie that pervade the place. We don’t all get mosquito bites, but after a week you come to enjoy seeing familiar faces and talking with them about what they’re seeing. Just as when you go to summer camp, you get to stay up late. But at no summer camp I ever attended did we drink so much beer.

JLG/SJ/DB

The principal speakers were Tom Paulus and Anke Brouwers, who covered Burt, and Steven Jacobs on Late Godard. The Masterworks in Context shows were introduced by several guest speakers, including Lisa Colpaert (excellent on I Walked with a Zombie) and Vito Adriaensens (covering both Murder! and Vampyr). For Pollyanna, Bruno Mestdagh of the Cinematek staff explained the process of restoration. I played utility infielder, offering one talk on Burt and three on JLG.

How often do you get to see 35mm prints of Une femme mariée, Passion, Je vous salue Marie, Détective, JLG/JLG, Eloge de l’amour, and Nouvelle Vague? The Godard series, which ended with a 3D show of Adieu au langage, was a high point of my summer viewing. Back home I had prepared by rewatching all Godard’s features from Sauve qui peut (la vie) onward, but my video homework didn’t prepare me for the way the big screen amps up their prickly, seductive power.

I don’t speak or read Dutch, so I missed many subtleties in Steven Jacobs’ talks, but thanks to Power Point I could figure out the main points. Few lecturers can pack so much information and ideas into ninety minutes.

We had no way of knowing how familiar the audience was with Godard, early or middle or late, so Steven started with an orienting talk on JLG’s pre-1980 work (above). He swiftly reviewed key aspects of Godard’s New Wave period, traced his shift toward “a critical cinema” between 1967-1969, and explored the move into his Marxist phase. Along the way, he stressed the way cultural developments like auteur theory, Pop Art, Maoism, Brechtian theatre, and semiotics shaped Godard’s films. Particularly acute was his discussion of the “one image after another” sequence in Ici et ailleurs (1975). In all, the talk was an ideal prelude to Une femme mariée, which pointed up so many motifs of the later work: the focus on the couple, the emphasis on media-based images, and the persisting shadow of the Holocaust.

Steven is an art historian at University of Ghent; he earlier appeared on this blog as co-author of the imaginative book The Dark Galleries. After tracing Godard’s return to mainstream cinema and his move to Rolle, Switzerland, Steven focused on that splendid example of JLG the painter, Passion. Steven has written eloquently on the film in his Framing Pictures, and here he widened his focus to discuss its relation to other films centered on the tableau vivant, like Pasolini’s La Ricotta and Ruiz’s Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting.

You’d expect that Steven would have a field day with Histoire(s) du cinema, and he did. Unlike most Godardophiles, I’m not wild about this series of video essays. I can’t take them as serious studies in film history, and too often I sense he’s just playing around. (Enough with the stroboscopic flashes, okay?) But Steven obliged me to rethink them by showing how they fit into the Postmodern art scene, especially the video art movement after the 1970s. He pointed out the central importance of the Hitchcock episode and the series’ constant concern with the Holocaust, often in dialogue with Shoah. Citing Godard’s claim that video taught him to see cinema in a new way, Steven suggests that the format also created a tenor of paradoxical melancholy. It’s as if JLG’s experiments with this new technology drove him to celebrate the death of the cinema he knew.

My three talks on Late Godard tried to ask something that I didn’t find many traces of in the literature. What are these films doing with (or against) narrative? I think that the focus on JLG as “film essayist” has sometimes obscured the fact that he has long insisted that he needs stories. Yet he seems to have no interest in the craft of storytelling as we understand it. He avoids dense exposition, careful foreshadowing, well-timed revelations, and cumulative climaxes. He tends to spoil the narrative expectations he sets up.

As a result, his plots—for his films have them—are distressingly opaque. Exactly what happens in a Late JLG film is often difficult to determine. I’m always surprised when discussions of these late films provide capsule plot summaries, for the very difficulty of arriving at these should claim our attention. As just one instance, many critics seeing Adieu au langage for the first time thought the film centered on one couple. It centers on two. But the fact of that mistake ought to interest us enormously: What in the film’s presentation made it difficult to follow the basic situation? Are there strategies Godard follows in creating his apparently willful obscurity?

Godard’s unique strategies of storytelling are carried down into felicities of visual and verbal style. Again, I think that critics haven’t sufficiently acknowledged just how strange and opaque the surfaces of these movies are. For one thing, characters are unidentifiable from scene to scene, thanks to camera setups that cut off their faces, wrap them in shadow, or leave them offscreen altogether.

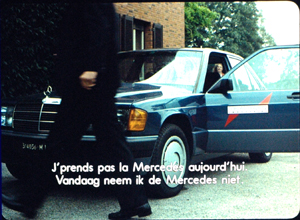

I’ve touched on these matters earlier (here and here), but just as a quick example, consider this shot from the opening of Nouvelle Vague. It has to be one of the most oblique introductions to a protagonist we can find in cinema.

Corporate owner Elena Torlato Favrini strides out of her mansion past her chauffeur while taking a transatlantic call. Any other director would favor us with a close view of her, perhaps tracking as she cuts a swath through her entourage. Instead we get a shot framing her chauffeur climbing out of their Mercedes.

As he crosses in front of the car, we hear her on her cellphone. She can be glimpsed fleetingly in the background, through the car window.

She approaches us, becoming briefly visible as she passes the car, but when she stops, she’s decapitated. We don’t get anything like a good look at her, and the locked-down camera refuses to reframe her. Instead, the framing emphasizes her slipping on her gloves.

The gesture ties into other imagery in the film. A little before this shot, there’s an isolated shot that establishes hands as a major motif in the film. But we should also notice that this fairly abstract shot also presents the gesture of Elena slipping on a glove. Or rather, it almost presents it, as the shot is abruptly chopped off just as the gesture begins.

So slipping on the glove, started in an earlier shot, is finished at the Mercedes. But just as important, the visual idea of a hand gesture broken by a cut resurfaces at the climax. When Richard Lennox helps Elena out of the water, the action is also incomplete. Only five frames show him grabbing her arm before a cut interrupts the action.

Another filmmaker would have held the image on that triumphant grip, but Godard denies us this little burst of satisfaction. Of the five frames in this bit of the shot, there is just one frame showing Richard’s hand seizing her. Godard again spoils a solid narrative effect. But he does narrative in his own way, with the broken-off gestures counterpointed by the hands that do meet at other points in the film.

Every scene in Nouvelle Vague, and most scenes in Late JLG, seem to me to be built on one or more fine-grained pictorial and auditory ideas like these. Those ideas can seem perverse, as in the chauffeur scene: why let us see his face but play down Elena’s? He’s not a major character; we don’t even learn his name until the film’s final moments. Unhappily, this peculiar instant of comparison is lessened in the 1.66 version of the film available on DVD. That image suppresses the driver’s face no less than Elena’s, losing Godard’s peculiar version of “gradation of emphasis.”

All the more reason to try to see these films in their full-frame glory, as I’ve argued before.

BL (Beautiful Loser)/AB/TP

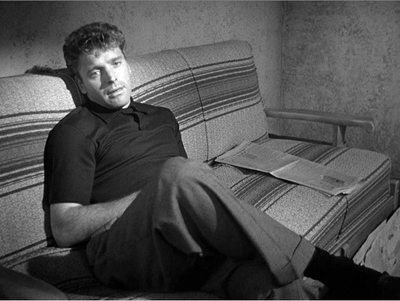

Criss Cross (1949).

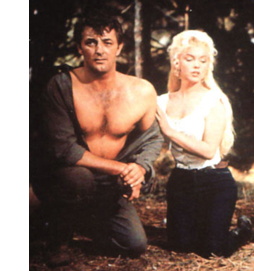

With big tousled hair, unadulterated sinew, and teeth gleaming like a Pontiac grille, Burt Lancaster came to fame in the late 1940s. He belonged to a new cohort of actors quite different from the 1930s Debonairs (William Powell, Melvyn Douglas, Cary Grant) and the Bashful Boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart). Yet the new lads were also at variance with the rugged Ordinary Joes (Cagney, Bogart, Tracy, Gable).

For one thing, Lancaster, Victor Mature, Robert Ryan, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, and Charlton Heston were brawny—monsters, in a way. They often took off their shirts. One publicity still for River of No Return shows Mitchum more unclothed than Monroe. Three of them played prizefighters, and Mitchum, himself a boxer, had the broken nose of a brawler.

For one thing, Lancaster, Victor Mature, Robert Ryan, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, and Charlton Heston were brawny—monsters, in a way. They often took off their shirts. One publicity still for River of No Return shows Mitchum more unclothed than Monroe. Three of them played prizefighters, and Mitchum, himself a boxer, had the broken nose of a brawler.

Of the group, Burt had probably the strongest A-list career overall. He fostered a great variety of projects. Who else of his generation appeared in films by Visconti and Malle? What other unflinching liberal was prepared to play a US general bent on a coup (Seven Days in May) or a conspirator behind the Kennedy assassination (Executive Action) or an obstinate officer fighting in Vietnam (Go Tell the Spartans)? He portrayed a renegade officer demanding the revelation of the brutal policy behind the Vietnam War (Twilight’s Last Gleaming). His closest rival and frequent costar Kirk Douglas didn’t enjoy such a vigorous and prestigious twilight. Only Brando kept beating him to the prize: Burt wanted to play the lead in Streetcar Named Desire and The Godfather. Unpredictably, he wanted as well to play the gay prisoner in Kiss of the Spider Woman.

I had had only slight interest in Burt as a star before this edition of the Summer School. But listening to the talks, seeing the films, and preparing my contribution made me realize how extraordinary an actor he was, and how important in Hollywood postwar history. Burt was well-served by the fine lectures offered by Tom Paulus and Anke Brouwers.

Anke provided an in-depth survey of how Burt and the Brawny Gang brought to a new level the culture of male athleticism—on display in Fairbanks and Valentino, developed further in the body-building craze of the 1930s, and culminating in what one 1954 magazine article called Hollywood’s “Age of the Chest.” She brought in forgotten pin-up boys like Guy Madison and pointed out how Burt and his peers paved the way for Rock Hudson and Tony Curtis. Anke went on to specify Burt’s beefcake persona, established in The Flame and the Arrow (1950) and locked into place in The Crimson Pirate (1952), which we saw. In her followup talk next day, she surveyed Burt’s place in the industry. He was one of the few stars to supervise a successful independent production company, Hecht Hill Lancaster (earlier, Norma Productions and Hecht Lancaster).

Tom moved on to consider Burt’s star charisma. He traced how Burt adjusted his authoritative image to different roles—the con man, the confident leader, the embittered idealist. Tom was especially good at analyzing Burt’s acting technique, tying it to particular trends in theatre and film of the time and pointing up the physicality of his performance of specific, precise tasks. Given the standard situation of rigging a bomb, he contrasted Burt’s meticulous finger work in The Train (1964) with that of Kirk going through the motions in The Heroes of Telemark. Tom even spared some time for Burt’s diction—a quality that really popped out when we watched Elmer Gantry (1960).

In a later lecture, Tom surveyed “Late Burt,” and his relation to political cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. He followed that with a revealing account of Burt’s relation to the trend of “Mexican Westerns” launched in the 1950s. Another arc in Burt’s career: from Vera Cruz (1954) to Ulzana’s Raid (1972), with The Professionals (1966) in between. That we saw in another gorgeous print.

I could go on a lot more about Tom and Anke’s lectures, but I don’t want to give away too much. The talks contained so much original research and discerning analysis of both the films and trends within film history that I’m hoping Tom and Anke will lay these ideas out at book length. Part “star study,” part film criticism, part industry history, their lectures were exhilarating.

My own contribution was minimal, a talk on First-Phase Burt. The Brawny guys were well-suited to the trend toward hard-boiled movies, those crime pictures we later decided to call “noirs.” Those weren’t usually suitable for older players (though there were some makeovers, such as Dick Powell and Fred MacMurray). To fill these roles came Alan Ladd, Glenn Ford, Dana Andrews, and Richard Widmark, along with the beefcakes. At the same time, “independent” producers within the studios began contracting their own new talent and loaning it out. Burt was signed by Hal Wallis at Paramount, who also had Kirk Douglas, Wendell Corey, and Lizabeth Scott in his stable. Films like Desert Fury (1947) and Sorry, Wrong Number (1948) were Wallis package projects.

Hired straight from the stage with no film experience, Burt debuted as the Swede in The Killers (1946), on loanout to Mark Hellinger at Universal International. Burt benefited from a galvanizing entrance. Lying on a bed in the dark, refusing to flee the hitmen on his trail, Burt is a shadowed, curiously languid torso in a tight undershirt.

Only after a beat do we see something else: massive hands rubbing a weary head. Soon that head is revealed.

As the killers burst in, the whole image comes together.

Has a Hollywood beginner ever been given such a gift as this opening?

With this onscreen wattage, it’s all the more striking that this young discovery is curiously absent from his early films. He’s onscreen for only a third of The Killers’ running time, and not even half of Brute Force (1947) and Sorry, Wrong Number. The film Wallis wanted to be his debut, Desert Fury (1947), gives him only twenty-three minutes out of ninety, and in the second male lead at that. All My Sons (1948) puts him in an ensemble drama. I Walk Alone (1948), the Norma production Kiss the Blood Off My Hands (1948), and another Universal project, Criss Cross (1949) start to make him a proper, central protagonist. By then, he is ready to become the star attraction of the swashbuckling films.

Moreover, in his early phase, he mostly plays losers. Not the brightest guy in the room, he’s easily suckered by a femme fatale in The Killers and Criss Cross. He makes amateurish mistakes at crime (Sorry, Wrong Number) and, coming out of prison, he is the last to realize the rackets have gone corporate (I Walk Alone). At the start of Kiss the Blood he punches a man too hard and kills him. He’s caught and whipped and imprisoned, and when he comes out he stumbles back into crime again. He’s shrewd enough to set up a prison break in Brute Force, but so doggedly determined is he to reunite with his girl on the outside that he launches a suicidal bloodbath.

When he finally catches on to his fate, we get expressions ranging from stupefaction to anguish (The Killers, Criss Cross).

He even cries (All My Sons, Kiss the Blood).

Loser or winner, when he is onscreen, he has the outlandish physical presence of the born star. Most obvious is a physique (Kiss the Blood, Brute Force).

Even his back, featured with a prominence we get with few other actors, is straining against a drenched prison uniform (Brute Force) or a tailored suit (Criss Cross).

The face was a cameraman’s dream; it could be craggy or somber, thoughtful or tormented (The Killers, Brute Force x2, Criss Cross).

He can be stiff-armed and zombielike coming out of prison in Kiss the Blood, but he can also gamely cock his elbows, ready to spring, like Cagney and Cary Grant (I Walk Alone).

The enormous hands, which look likely to crush a skull (Criss Cross) or rip apart a phone cord (Sorry, Wrong Number), could be surprisingly delicate, tentatively touching his girlfriend’s wheelchair or laying down plans like playing cards (Brute Force).

In The Killers he makes skillful use of those hands, pocketing his busted one or spreading out the scarf given him by the treacherous Kitty.

Easily taken in by Kitty’s plan, he seems to have a qualm when his gripping embrace relaxes and the fingers splay in hesitation.

This sort of handwork would become crucial, as Tom pointed out, to Burt’s performance style, particularly in The Birdman of Alcatraz.

“I’d never looked in eyes as chilling as Lancaster’s,” Norman Mailer once said. You can see what he meant.

Again, though, the actor is in control. Some years back I wrote that eyes by themselves aren’t very expressive: the eyelids, eyebrows, and mouth tell us more. I still think that’s right, but Burt manages to convey the sense of the beast at bay with remarkable control of just the eyeballs. He seems to be looking for an escape hatch without moving his head an inch.

While Burt was playing losers, his counterpart Kirk Douglas was often playing heels—cynical manipulators who stomp on everybody else, as in I Walk Alone. Sometimes Kirk learns his errors (Young Man with a Horn, 1950) but several roles of the period, in Out of the Past, Champion, and Ace in the Hole, make him a glib villain or tawdry antihero. Somewhat later Burt explored this characterization too, notably in Vera Cruz, Elmer Gantry, and The Rainmaker (1956). How did he shift from the beautiful loser to the fast-talking con artist?

I think there are hints from the start. In The Killers, after he’s washed up as a fighter, the Swede goes in for street crime. When he confronts his old friend the cop, Lancaster brings those arms and hands into play. In his enormous unstructured topcoat, he lifts his fists up to his waist. It’s both the businessman’s getting-down-to-brass-tacks sweep, but also a kind of puffing up, exposing that massive frontal expanse. Little Sam Levene can grasp his lapels, but he doesn’t stand a chance against this.

Burt uses the same imperious gesture when, in Sorry, Wrong Number, he’s trying to bully a company employee into joining a crooked deal.

In these noir movies, his intimidation of others won’t put him ahead of the game. But perhaps these arm movements begin to sketch a more flamboyant loser like Gantry. By striking what actors used to call an “attitude,” Burt could start to build an entire character: a hell-for-leather charlatan.

Seeing the films, listening to Tom and Anke, and studying Lancaster’s work on my own brought home to me again the importance of the details of performance and the presence of a star. These movies would be utterly different if Mitchum or William Holden played the Burt parts. Our actors don’t wear masks or Hazmat suits. We’re powerfully affected by what they bring to the character in voice, body, face, and gesture—the expressive dimensions of cinematic presence.

BL/JLG/BF

College coordinators Lisa Colpaert and Bart Versteirt, flanking Bill Forsyth.

What do Burt and JLG have in common? For one thing, some images from Criss Cross in Histoire(s) du cinema 1a (see above). For another, Bill Forsyth.

With the success of Gregory’s Girl (1981), Bill was invited by David Puttnam, then at Columbia, to make a Scottish movie with a couple of American actors. The result, Bill says, now looks to be a “soft-core environmental movie.” Local Hero (1983) remains much loved, and for good reason. It makes nearly all of today’s multiplex raunch look adolescent. It has a tone of civility, an embrace of eccentricity, and a genuine interest in people reminiscent of Ealing comedies. For me it’s a masterpiece of sweet, light-hearted art.

Local Hero feels loose and leisurely, but it’s actually a very economical movie. The first few minutes should be studied by screenwriters interested in tight exposition and fast attachment to a protagonist. It’s peppered with sidelights on its central drama, such as the Russian’s song about how “even the Lone Star State gets lonesome.” That neatly sums up the situation of the yuppie sad sack MacIntyre (“I’m more of a Telex man”) learning about village life. As usual, I was moved by Mark Knopfler’s plangent score, the electronic overtones meshing with the pulsations of the Northern Lights.

Burt’s role is that of CEO deus ex machina. Having assigned Mac to buy a Scottish seacoast town for an oil refinery, Mr. Happer eventually descends in his chopper and decides to establish a laboratory there instead. Burt’s crisp delivery and tight fingerwork are still on display at age seventy. The other actors don’t use their hands as much as he does–partly so they’re not distracting us from him, I suspect, but also because newer-style Hollywood acting doesn’t encourage it. In any case, as usual Burt uses his acrobat’s sense of physicality to intensify his performance. Even clasping his hands behind his back tells about the character’s authoritative dignity.

Bill learned that Burt regretted not doing more comedy, so he wrote the mogul’s part with him in mind. Burt signed on eagerly. He showed up on the set with a full beard, hoping Bill would let him keep it; they compromised on a mustache.

Bill had worked mainly with teenage actors on That Sinking Feeling (1979) and Gregory’s Girl, so Burt was really the first adult performer he ever directed. Across their three weeks together, Burt demanded nothing, except that he wanted to loop his dialogue. Bill preferred not to loop, and as it turned out only one scene needed to be rerecorded.

Burt and Bill skipped lunch in order to prepare the next scene, becoming “lunch bums.” Bill remembers Burt hanging out with the other actors and chatting with extras. He freely made fun of Bill’s accent: “”He speaks no known language.” He told Bill: “I don’t know what you’re saying, but I know what you mean.”

Bill talked as well about his own career. Starting out in the days before home video, he learned dialogue and pacing by audio taping classic films. (Sounds like a good idea to me.) He became a performer’s director. “The only thing I’ve ever said to a cameraman is: ‘Accommodate the actors.” He quoted Burt approvingly: “The space in front of the camera is the actor’s space.”

What’s the connection to JLG? It turns out that Godard was the director Bill most admired in his salad days. During the 60s he sated himself on art cinema, especially New Wave imports. When he saw Pierrot le fou, he left the theatre stunned. Godard became “the master. He still is, for me.”

Accordingly, Bill’s earliest cinema efforts were in an avant-garde vein. One piece, puckishly called Film Language, started with ten minutes of black leader while a text by Beckett was read out. Another, Waterloo, included a vast ten-minute shot in which the camera left one household, climbed into a car, rode a great distance, and ended up in another home. The film played at the Edinburgh film festival to an audience of 200. By the end three viewers were left. “I’d moved my first audience.”

Bill remarked that he sometimes regrets not sticking with experimental media. Today, he says, he might be a video-installation artist. A teasing idea. But we should be grateful that we got his features. I don’t know if Jean-Luc would agree, but I bet Burt would.

Thanks to Bart Versteirt, Lisa Colpaert, and their colleagues for a great week. Thanks as well to the participants, whose willingness to take on anything we threw at them was very encouraging. And a farewell to two friends who have projected films at every Summer Film College I’ve attended over the last sixteen years: Esther Dijkstra and Joost De Keijser. They have helped make the event the splendid enterprise it is.

Peter Bosma’s informative book Film Programming: Curating for Cinemas, Festivals, Archives is available here.

A detailed “index of references” for Histoire(s) du cinema is provided by Céline Scemama.

Our first encounter with Bill Forsyth was at Ebertfest. For more on actors’ handiwork, try this entry.

An eager crowd of campers awaits Adieu au langage.

Nitrate days and nights

Paolo Cherchi Usai introducing a session of The Nitrate Picture Show.

DB here:

Our entries have been laggardly lately because of various factors: a trip to a family wedding in DC, work on a new edition of Film Art, a stubborn cold, and not least, a bustling trip to Rochester’s George Eastman House for The Nitrate Picture Show. This last event is the topic for today, and hoo boy was it something.

Handle with care, respect, and admiration

Light Is Calling (2004).

For the first fifty years or so of cinema, commercial feature films were shot and shown on nitrate-based film stock. The film emulsion, consisting of silver halide crystals (for black and white) or dyes (for color), was supported by the base, a clear, flexible strip. That strip was made of nitrocellulose.

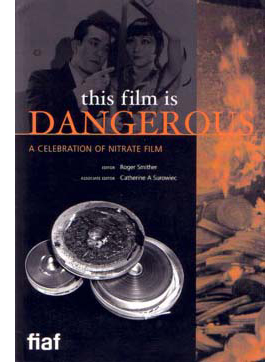

In a talk at the Picture Show, Roger Smither, editor with Catherine Surowiec of the definitive compendium This Film Is Dangerous, reviewed some essential features of nitrate. As most people know, it catches fire easily. Quentin Tarantino built the climax of Inglourious Basterds around a theatre fire deliberately set by touching off heaps of nitrate. Robert Flaherty famously barbecued his initial footage of Nanook of the North by smoking while he worked on editing it. No surprise that nitrocellulose was used in munitions, where it was often called “gun-cotton.”

In a talk at the Picture Show, Roger Smither, editor with Catherine Surowiec of the definitive compendium This Film Is Dangerous, reviewed some essential features of nitrate. As most people know, it catches fire easily. Quentin Tarantino built the climax of Inglourious Basterds around a theatre fire deliberately set by touching off heaps of nitrate. Robert Flaherty famously barbecued his initial footage of Nanook of the North by smoking while he worked on editing it. No surprise that nitrocellulose was used in munitions, where it was often called “gun-cotton.”

Once ignited, nitrate is hard to control. It will burn under water, and it can feed on its own flames. A dramatic 1948 documentary screened at the Picture Show presented almost comically horrifying ways in which a nitrate fire resists extinction. Nitrate also produces highly toxic gases. For such reasons, nitrate projection booths are designed to slam shut tight and let the fire eventually exhaust itself. God help you if nitrate goes up in an open warehouse or theatre space.

It was this volatility that forced most national film industries to convert from nitrate-based stock to acetate, or “safety,” stock. In America, the process began soon after World War II and, among other advantages, allowed exhibitors to lower their fire-insurance costs. Other countries were slower to convert; at the Picture Show, some people mentioned that the Soviet Union was still using nitrate stock in the early 1960s. As for archives and laboratories storing nitrate films, conflagrations were distressingly common. Roger and Catherine’s book list dozens of major nitrate fires from 1896 to 1993.

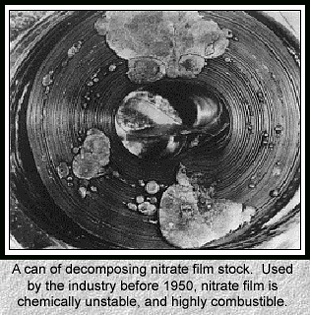

Apart from its tendency to blow up, nitrate is chemically unstable and can decompose. Heat, moisture, and exposure to chemicals can wreck nitrate in a host of ways. It can become infiltrated with a blotchy growth that some find piquant (viz. Bill Morrison’s Light Is Calling, above). The base can flake off from the emulsion. A nitrate print can shrink, warp, blister, or become brittle. The film can start to smell, or turn to brown powder. Some of these problems are present with acetate as well, but combined with the possibility of nitrate combustion, acetate had an advantage.

A string of well-publicized explosions in the 1970s at the Library of Congress, Eastman House, and the Cinémathèque Française resulted in millions of feet of film being lost. National governments became aware of the threat to their film heritage. Archivists seized upon the slogan, “Nitrate won’t wait,” and circulated scary images like the one on the left. Money was given, and thousands of feet of film were transferred to safety stock. In the process, however, a fair amount of nitrate was discarded. In 2000, Roger noted, archivists were surprised to learn that a great deal of nitrate around the world remained in good shape. The late Susan Dalton, our archivist here at Madison for many years, argued that all of today’s films should be transferred to nitrate, the most proven and reliable long-term format.

A string of well-publicized explosions in the 1970s at the Library of Congress, Eastman House, and the Cinémathèque Française resulted in millions of feet of film being lost. National governments became aware of the threat to their film heritage. Archivists seized upon the slogan, “Nitrate won’t wait,” and circulated scary images like the one on the left. Money was given, and thousands of feet of film were transferred to safety stock. In the process, however, a fair amount of nitrate was discarded. In 2000, Roger noted, archivists were surprised to learn that a great deal of nitrate around the world remained in good shape. The late Susan Dalton, our archivist here at Madison for many years, argued that all of today’s films should be transferred to nitrate, the most proven and reliable long-term format.

There was also an argument for keeping nitrate around on artistic grounds. As Roger put it: “It’s pretty.” Everyone I know agrees. In the late 1970s Kristin and I saw at MoMA a double bill of two nitrate prints, Gance’s La Roue and Ford’s How Green Was My Valley. They glistened. Later, attending the Pordenone Giornate del Cinema Muto and Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, we saw lots of nitrate prints and were always overwhelmed. The images, especially from very early films, seemed at once sharp in contour and soft in textures.

So nitrate images look great. But why? Some say that nitrate prints have more silver in the emulsion than acetate ones. In This Film Is Dangerous, John Reed suggests that the increased “silver load” yields solidity in shadow areas and vitality in white ones. He also speculates that nitrate-based copies may benefit from projector lenses, screen surfaces, and carbon-arc projection (this last a topic I’ve touched on briefly with respect to Technicolor). If all these factors are in play, the beauty of the copy may be only contingently related to nitrate as such.

Moreover, can we specify the Nitrate Look, in the way we can tell oil paint from water colors? Conducting an informal survey of archivists at the Picture Show, I could find no one who would claim that he or she could confidently spot a nitrate print simply from seeing it projected. Perhaps we are not yet at the stage of connoisseurship of a traditional art historian. Or it may be that foreknowledge that a print is a nitrate one biases us toward ascribing more beauty to the images. To get a precise sense of the Nitrate Look, Reed suggests we’d need an A/B test, running a nitrate print side by side with a fine-grain acetate positive from the same negative.

Richard Koszarski pointed out in conversation that watching a nitrate print we know we’re getting something old–if not an original (it could be a re-release print), at least a copy that audiences did see back in the day. Paolo Cherchi Usai, in introducing the Show, pointed out that the goal was not simply to screen a lot of classic films but to present an experience of cinema from another time. In addition, you have to admire the sheer robustness of these survivors: the prints have been shown a lot and still look lustrous.

To put the emphasis on the “nitrate experience,” nearly all the titles of the films were kept under wraps until we arrived. The goal was not to enhance or deflate the mystique of nitrate, but to call attention to the unique beauties of specific copies and to ask us to reflect on the purposes and consequences of film preservation. To the same end, in a lecture Kevin Brownlow surveyed his efforts to rescue rare footage by Chaplin, Gance, and others.

A panel discussion of archivists considered whether 35mm, in any form, was still viable for public showing. Answer: Most definitely. If a venue meets archival screening conditions, libraries are willing to loan copies. Just don’t count on nitrate ones. Paolo estimates that there are fewer than half a dozen nitrate-secure projection booths functioning in Europe and the US.

No pixels, please, we’re purists

Leave Her to Heaven (1945).

Whatever the cause, the films looked undeniably spectacular. I was least taken with the 1930s Selznick items, A Star Is Born (1937, in a 1946 reissue print) and Nothing Sacred (1937). They have never seemed to me first-rate movies: I think the Cukor Star Is Born is far superior, and Nothing Sacred, after a lively opening, seems to me to run out of comic steam. Not enough characters, maybe; not enough twists, possibly; too much Walter Connolly, I’m sure. Twentieth Century beats it hands down. But of course the prints were very good, and the genial William Wellman, Jr., came by with informative background information keyed to his new biography of his dad. (Lest I seem to be opposed to Wild Bill, let me record my admiration for G. I. Joe, Battleground, The Ox-Bow Incident, and Track of the Cat.)

The Selznick prints suggested progress in 1930s Technicolor. I was struck by the problems of matching brightness and hues from shot to shot, or sometimes right after a cut, as early in A Star Is Born.

By the end of the decade, of course, with Snow White, The Wizard of Oz, and Gone with the Wind, Technicolor had created a more consistent palette.

The 1940s, the great era of Tech, was on rich display in other titles. I had to miss Black Narcissus, but this may have been the British Film Institute copy I’ve seen. I remember the color as being as both gloomy and ripely unrealistic. [Nope! It was the Academy copy, and everybody told me it was gorgeous.]

The copy of Leave Her to Heaven (from UCLA) made Gene Tierney’s ruby lips all but float off the screen at you. Even wilder was a demonically gorgeous print of Samson and Delilah from the Library of Congress. The movie is typically silly DeMille, but it’s fun to watch how a story you already know gets padded out with a fierce lion, bevies of dancing girls, and a somnolent George Sanders, the man who died of boredom.

The spectacle is what the audience was paying for, and the color design gave them their money’s worth. No movie I’ve seen lately galvanizes the spectrum the way this one does. The almost shadowless lighting makes every color pop. I don’t think I’ve ever seen as many shades of pink and purple in a movie, and the pastels admirably set off the burnished beefcake of Victor Mature.

Richard Koszarski, still on a roll, pointed out that Sunset Blvd., the film in which the Gloria Swanson character visits DeMille on the Samson set, features an odd homage. The phone table at the apartment of Artie Green (Jack Webb) boasts a statuette of the god Dagon, whose temple Samson pulls down.

Did Artie pilfer a model? Is it an in-joke like Pike’s Pale? Or a piece of remote cross-promotion? There’s always more to see.

Monochrome as multichrome

The Fallen Idol.

The black-and-white nitrate titles were just as astonishing. Casablanca had a subtle gray scale I had never noticed before; it would be worth comparing this print with the digital copy piped to theatres as part of the recent classics revival series. Can the latter be anything like this? The first Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) is no stranger to this blog; the 1943 print looked crisp and sounded exceptionally good.

Rene Clément’s Les Maudits (1947, “The Damned”) was previously unknown to me. It’s a remarkable wartime thriller, with long, tight tracking shots through a submarine and cramped, noirish deep-space compositions.

Clément employs a flashback narration that stems from the protagonist writing his memoir of the incident. It looks forward to Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest, but in a way it’s a bit more daring, because it mixes the character’s voice-over but with the commentary of an impersonal objective narrator.

Somewhere between color and black-and-white was the delirious fantasy romance Portrait of Jennie. It has its problems, chiefly a subplot showing the painter Eben Adams working on a barroom portrait of Michael Collins, but there is a goofy grandeur to the whole enterprise. The magnificent corps of Eastman projectionists managed to re-create the splashy climax of original 1948 screenings. Not only does the image go green, but it gets bigger. Bosley Crowther reports it an apotheosis of kitsch.

Then, when a green flash of lightning electrifies the screen, which expands to larger proportions, and sound vents around the theatre roar with the ultimate and savage fury of a green-tinted hurricane, the final vulgarization of Mr. Nathan’s little fable is achieved.

The effect is indeed overblown, but I didn’t hear anybody in Rochester complain.

The final title, kept secret until the moment of projection, was The Fallen Idol, one of the great staircase movies in an era of great staircase movies. An exercise in Jamesian restricted viewpoint–What Maisie Knew, for the cinema–it confines us almost wholly to a little boy who worships the family butler but can’t quite fathom the currents of grownup unhappiness and betrayal swirling around him. Carol Reed’s love of low angles and looming foreground planes is kept under precise control, and the moments of suspense, notably the famous swooping circuit of the paper airplane, remain just as strong as ever.

I have to believe that James Card, legendary master of Eastman House, would have approved of the whole shebang. This is his centenary, and along with the Picture Show there was an informative display surveying the career of the man who, with saintly George Pratt at his side, gave Eastman House its unique cachet.

The Nitrate show drew about 300 passholders and as many as 100-150 locals for some shows. It’s planned as the first in a series. Next year’s session is slated for 29 April-1 May. See you there?

Thanks to Paolo Cherchi Usai and Jared Case for their hospitality during my visit. Thanks as well to the Eastman House staff, especially Deborah Stoiber, Jurij Meden, and Ben Tucker, who made the weekend memorable. In all, excellent programming and presentation!

An entertaining account of the preservation movement is Anthony Slide’s Nitrate Won’t Wait: Film Preservation in the United States (McFarland, 1992). It’s there I learned that Kemp Niver once pulled a gun on Raymond Rohauer. Archivists were tough in those days.

The stupendous volume edited by Roger and Catherine, This Film Is Dangerous: A Celebration of Nitrate Film (Brussels: FIAF, 2002) is full of information, anecdotes, and whimsy (poems, caricatures). On the history of the technology, the best starting points in this collection seem to me Deac Rossell’s “Exploding Teeth, Unbreakable Sheets and Continuous Casting: Nitrocellulose from Gun-Cotton to Early Cinema” and Leo Enticknap’s “The Film Industry’s Conversion from Nitrate to Safety Film in the Late 1940s: A Discussion of the Reasons and Consequences.” John Reed’s skepticism is recorded in “Nitrate? Bah! Humbug! A Personal View from an Archive Heretic.”

All of the films screened are available on DVD, but I want to signal Les Maudits, on the Cohen label, as a real find. My Star Is Born frames comes from the Kino Blu-ray release, itself drawn from the Eastman House print we saw.

A sunny spring day in Rochester: the perfect time to head into the Dryden Theatre for a movie.

P.S. 13 May 2015: During the fest I hung around with Richard Leskosky, retired prof and Ebertfest buddy, and he’s written a fine column about the event.

P.S. 15 May 2015: Thanks to André Habib for correcting my attribution to the Bill Morrison film; I’d originally identified it as Decasia. And thanks to Mike Pogorzelski of the Academy for correcting me on the source of Black Narcissus. I sure wish I hadn’t been too logy to stay for it.

They had time for everything then

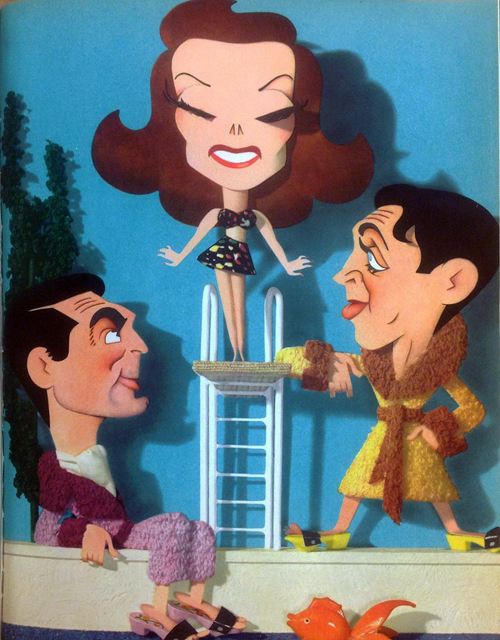

Advertisement for Woman of the Year. From Hollywood Reporter (23 April 1942), 5.

During the 1940s, MGM promoted some of its top pictures with unique illustrations. The artist would make cutout caricatures of the stars, dress them in fabrics, and then prepare little shallow-relief scenes, with props made of wood, carpets, and other stuff. Above, the microphones seem made of metal and plastic, and Tracy’s coat has real buttons attached. Below, the men’s slippers are three-dimensional, as is the toy goldfish and, I suppose, the diving board.

The little tableau would then be photographed, in luscious color. Some were printed with elaborately embossed borders.

I say “the artist” because he or she goes unidentified on these advertisements. The only signature is an enigmatic “K”; in the image above, it’s on the tiny baseball at the bottom. If anyone knows who K is, or can supply further background, please correspond.

Interestingly, these charming images continued to be published from time to time through the early years of the war. I’m afraid my reproductions don’t do them justice, but you get the idea.

Damn, but film research is fun.

P.S. 24 April 2015: Ask and ye shall receive. Alert reader Mark Schoenecker writes:

I’m sure you’ve already received correspondence naming the identity of the mysterious MGM illustrator responsible for those distinctive 3D paper sculpture pieces from the 30s and 40s — but in case you haven’t, his name is Jacques Kapralik. I’m an illustrator myself and have always been vaguely aware of the existence of these cut-out posters. What I didn’t know was that one man was behind them. I’d assumed it was a style prevalent during that era. It wasn’t until I found myself drawing my own series of caricatures in a similar vein that I decided to track down the originals online to see if I was remembering them accurately.

Here is a link to the most interesting article I came across: https://mubi.com/notebook/posts/movie-poster-of-the-week-the-jacques-kapralik-archive

I should’ve known that the indispensable MUBI would have something on this. It’s a fine piece of work by Adrian Curry, showing that Kapralik did movie title sequences as well. Be sure to check the links in that entry and the comments. The University of Wyoming holds Kapralik’s collection, and an online finding aid gives access to many of his beauties.

Many thanks to Mark for clueing me to this. You should immediately check Mark’s own lively, dry, and sometimes scathing, caricatures here. Who else thinks of drawing Dorothy Kilgallen and Korla Pandit?

Advertisement for the The Philadelphia Story. From The Hollywood Reporter (31 December 1940), 7.