Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

Local Boy Makes Very, Very Good: Welles comes home

DB here:

Nearly a hundred years ago George Orson Welles was born in Kenosha, Wisconsin. The story goes that when the UW—Madison asked him to come get an honorary degree long afterward, he refused. The reason? He claimed he was conceived in Rio de Janeiro, so he considered himself Brazilian.

About ninety years ago, little Orson went to Indianola summer camp outside Madison. (A memoir of his stay, criticizing Welles’ more lurid version, is here.) He attended fourth grade in Madison 1925-1926. At that time he was studied as a child prodigy by psychologist Dr. F. G. Mueller. A story about the little rascal, who was already staging plays, appeared in a local paper. Then he transferred to the Todd School for Boys in Woodstock, Illinois.

About ninety years ago, little Orson went to Indianola summer camp outside Madison. (A memoir of his stay, criticizing Welles’ more lurid version, is here.) He attended fourth grade in Madison 1925-1926. At that time he was studied as a child prodigy by psychologist Dr. F. G. Mueller. A story about the little rascal, who was already staging plays, appeared in a local paper. Then he transferred to the Todd School for Boys in Woodstock, Illinois.

Madison has done pretty neatly by him. Our Wisconsin State Historical Society collections include some Wellesiana: production material on Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, and unmade projects, along with a rich trove from Agnes Moorehead, who taught school in Soldiers Grove and got a Masters at our university. For decades, Welles’ films were staples of our bustling campus film-society scene, and out of that emerged Wisconsin-born Joseph McBride. Joe produced a fine critical monograph on Welles in 1972 and has been writing about him ever since. Another supremo Wellesian, James Naremore, did his doctorate here. Douglas Gomery, one of our Film Studies alumni, wrote a foundational study of Welles’ relation to the studio system, and Michael Wilmington, who collaborated with Joe on a book on John Ford, has also written eloquently on Welles over the years.

So I had good luck coming here in 1973. As a teenager getting interested in film, I focused most avidly on Welles. I watched Kane and Ambersons on late-night TV, and as a good omen, there was a 16mm screening of Kane during my first week as a college freshman. With pals I traveled to New York to see the newly released Chimes at Midnight (twice) and wrote a review for our student newspaper. A few years after that Film Comment published my first serious piece of film criticism, an essay on Kane. That movie has been a leitmotif of my life—a centerpiece of our textbook Film Art since its publication in 1979, important in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, and still stubbornly facing me down in my current struggles with 1940s Hollywood narrative.

So it’s in the nature of things that our Cinematheque is honoring Welles in a year-long retrospective that started in January. And it’s even niftier that our current Wisconsin Film Festival has included three items celebrating this prodigious and prodigal Cheesehead.

Never too much johnson

I like quick cutting very much. I didn’t do much of it at the start. But the more I work, the more I like it.

Orson Welles

Welles shot film material to fill in exposition for the three acts of a stage production he was mounting in 1938. Too Much Johnson was a revival of a turn-of-the-century farce, and how the smart-alecky boys must have snickered at the title. The film remained uncompleted and was never shown with the play (which failed out of town). Welles edited the first part of the footage to some extent, but what remains of the rest are rushes. The footage was discovered in Pordenone, Italy in 2008 and has recently become available for screenings. You can watch it on Fandor, though we discovered that it plays best on the big screen with an audience and live music. For us, piano accompaniment was supplied by the versatile David Drazin.

Movies have long been mixed with live performance. Early films were inserted between vaudeville acts. In Japan, films enhanced and extended the action of plays. Eisenstein famously insinuated comic footage into his 1923 Moscow production of The Wise Man, and the idea caught on in Europe as well. By 1938, the New York stage had its own tradition of mixed-media, notably in the “Living Newspapers” sponsored by the Works Progress Administration. Welles had played in another politically pointed production, Sidney Kingsley’s Ten Million Ghosts (1936), which incorporated both slides and film.

The Too Much Johnson footage is a tribute to silent movies, or at least silent movies as a young theatre director in 1938 thought of them. At that time, many intellectuals admired slapstick comedy; serious silent drama was largely considered old-fashioned and “theatrical.” Movie aficianados also appreciated the silent avant-garde, especially Clair’s Entr’acte (1924), which enjoyed a place in the crystallizing Museum of Modern Art canon. Entr’acte, another movie inserted in bits during a stage show (Rélâche), was itself a reworking of American chase-and-stunt extravaganzas. I think the Too Much Johnson material bears traces of both Hollywood and Paris, especially with certain cuts that are even bolder than what we’d find in Sennett or Lloyd.

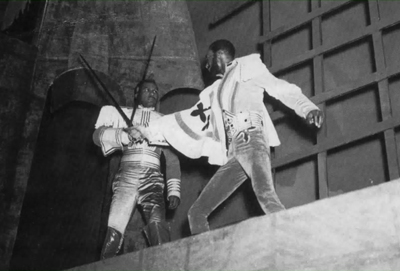

Welles scrambles several trends of silent cinema. To evoke the period of Gillette’s 1894 play, an early scene suggests filmed theatre before 1908 or so, but Welles immediately interrupts it with very brief, looming close-ups.

Elsewhere, Welles provides a flurry of Soviet-style axial cuts when the couple are interrupted in bed.

These “concertina” cuts, along with the mismatches of a twisting Joseph Cotten, create a jumpy effect reminiscent of Kuleshov’s By the Law (1925) and other films. (Though I doubt that Welles had seen that.)

There’s also a lot of Soviet-style Eccentrism in the opening footage, with Cotten scrambling over buildings and through a market in the Harold Lloyd manner. At both a pastiche and a potpourri, Too Much Johnson stands as something more than a curiosity. It’s a sketchbook, a finger-exercise in silent cinema technique, and a testament to buoyant youth from a twenty-three-year-old. It’s also evidently the first of Welles’ many unfinished films.

Noble artificiality

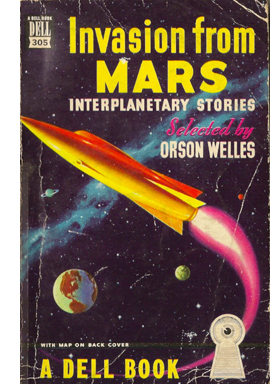

Chuck Workman’s Magician: The Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles has the good sense not to get in the way of Welles’ overwhelming presence. The documentary smoothly incorporates many interview clips with Himself and collaborators, kin, and admirers. There are also some splendid family photographs. The structure is chronological, and clips from the film are surrounded by contextualizing commentary from Welles and others. There’s a wonderful moment when Workman illustrates, with production photos, the dead silence following the Martians’ attack in Welles radio drama. The documentary even manages to throw doubt on Welles’ reminiscences by juxtaposing contradictory interview statements. I have a hunch that Jim Naremore, who was the major consultant on the project, encouraged this sort of historical frankness. Every Welles researcher knows that against his selective memory and penchant for fabulism, the documents must be checked.

Among the familiar but always compelling landmarks, Norman Lloyd makes a comment that set me thinking. “He brought, in one word, theatricality.” Welles was a sponge, blending many of the innovations in staging and conception that streamed into America from overseas, but I think he was particularly marked by what was then called “theatrical theatre.”

Among the familiar but always compelling landmarks, Norman Lloyd makes a comment that set me thinking. “He brought, in one word, theatricality.” Welles was a sponge, blending many of the innovations in staging and conception that streamed into America from overseas, but I think he was particularly marked by what was then called “theatrical theatre.”

The Europeans, notably Piscator, and the Russians, notably Meyerhold, had embraced frank artifice. They challenged all forms of realism, from the bland ignore-the-fourth-wall parlors of the well-made play, to the Naturalist notion that the play was a “slice of life” and that you could hang bleeding cuts of meat in your stage-set butcher shop. They also challenged the atmospheric Symbolism of Appia and others. Instead, theatrical theatre offered a stripped-down presentation that broke with the proscenium and hurled itself at the audience. The stage space was no longer a room or imaginary world cut off from the audience; it was of a piece with the auditorium. Performances were no longer representational, but “presentational,” in the manner of jugglers, acrobats, or…magicians.

For Americans, the idea of Theatrical Theatre was crystallized in Mordecai Gorelik’s book New Theatres for Old (1940). Gorelik traced the trend from Toller’s Masse Mensch (1921) directly to Welles’ 1937 “no-scenery” production of Julius Caesar. Other productions of that season, including The Cradle Will Rock (Welles and Houseman, using a bare stage perforce) and Our Town, with its scripted catcalls from the audience, were turning the blank stage into a space continuous the auditorium—not an imaginary locale but an area for acting and interacting.

Gorelik quotes Gordon Craig: “Do not forget that there is such a thing as noble artificiality.” Not a bad summation of Welles’ productions, including the Harlem Macbeth (above) and the War of the Worlds broadcast, as well as the films. Theatrical theatre is confrontational, sometimes angrily and sometimes, as in Welles’ penchant for reviving vaudeville, good-naturedly. Even Gorelik couldn’t go along with Mercury’s 1937 Faustus, which he deprecated as a “sleight-of-hand performance.” But I think it’s plausible to take Welles as in the tradition Lloyd alludes to. Expecting realism blocks some people from appreciating the brazen stylization, the pranksterish poke in the eye we get from many of the movies.

Hearts of age

Over the last thirty years or so, I remembered Chimes at Midnight as a more cohesive movie than the admirably choppy Othello. Seeing Chimes again yesterday, I realized that they were mates. There was the same ransom-note assemblage of scenes, the abrupt cutaways covering changes in character position, the use of long shots showing characters not speaking the lines we hear them say. You hear a line and may find that nobody has opened his mouth. An empty tavern becomes suddenly full after we’ve hung around one area of it. The great battle scene starts out making sense spatially but then dissolves into chaos, as men grind and hammer one another, and the dust at their feet turns to bloody mud.

So what? One of the lessons Welles seems to have learned from Eisenstein is that continuity is overrated. Almost every shot-change forces you to readjust your attention, and a cut is less a link than a jolt. André Bazin was right to praise Welles’ long takes, but the Wonder Boy of the 1940s also loved disjunctive cuts, apparently from Too Much Johnson onward. Not all the harsh editing in The Lady from Shanghai and Macbeth can be attributed to studio interference. By the time we get to Othello, the same paste-up aesthetic governs almost every scene, with sound sometimes covering the gap and sometimes accentuating it.

Welles told Peter Bogdanovich that only the Greeks and the French classicists wrote true tragedies. Tragedy ought to be austere and pure, he seems to have thought. Shakespeare, he insisted, gives us high-level blood-and-thunder melodrama. So his Shakespeare films are rough and tumble, full of violent, strident effects, from the brimstone paganism of Macbeth to Othello’s Turkish-bath assassination. Here, it’s Falstaff and his followers providing earthy comedy, with Prince Hal enjoying the riotous living and the escalating slanging matches, where punning insults are swapped between gulps of sack. The glowing Boar’s Head versus the spare, chilly palace; fiery Fat Jack versus severe, monastic Henry IV; romps in the forest versus carnage on the battlefield—these are the options facing the young prince. Playing, as we now say, the long game, he warns Falstaff twice that when he assumes power, the old rogue will be cast off. When the new king follows his father’s advice “to busy giddy minds with foreign quarrels” (sound familiar?), you have to wonder if an occasional robbery of pious pilgrims is worse than Henry V’s cynical venture into patriotic gore: “No King of England if not King of France!” Falstaff, cold as any stone, is hauled off to his grave. Melodrama, again, and none the worse for it.

Thanks to Jared Case of George Eastman House who brought Too Much Johnson to us and provided lively commentary. Eastman House is the archive that restored the film, and is the site of The Nitrate Picture Show starting 30 April. (See you there?) Thanks as well to Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, and Mike King of our festival for many varieties of help. They do a swell job.

Frank Brady interviewed Welles extensively about the Too Much Johnson project, and the informative results are in Brady’s Citizen Welles: A Biography of Orson Welles, 145-151.

The Wisconsin Film Festival runs until 16 April, and there are many high points yet to come—not least, a 35mm screening of Where the Sidewalk Ends (15 April), which Kristin and I must miss (snif). The Cinematheque series continues this summer with a focus on Welles the actor, and in the fall with several rarities.

Of the many, many Welles celebrations this year, the Indiana University one later this month will surely be the lollapalooza.

Douglas Gomery’s trailblazing article, arguing that Welles was a prototype of the Hollywood independent, is “Orson Welles and the Hollywood Industry,” Persistence of Vision 7 (1989), 39-43. On Too Much Johnson, see Joe McBride’s in-depth piece at Bright Lights. There are too many excellent books on Welles to itemize here, but at the very least your shelf needs Peter Bogdanovich and Jonathan Rosenbaum’s This Is Orson Welles, Jim Naremore’s Magic World of Orson Welles, Joe McBride’s What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?, Jonathan Rosenbaum’s Discovering Orson Welles, and Simon Callow’s luxuriant two-volume biography. The most complete account of Welles’ stay in Madison that I know is in Peter Noble’s The Fabulous Orson Welles, pp. 26-33. The article about the Boy Wonder, age ten, appeared in The Capital Times (19 February 1926). Welles talks about Shakespearean plays as melodrama in the third audiocassette accompanying This Is Orson Welles, at 52:02.

Our analysis of Citizen Kane occupies chapters 3 and 8 of Film Art, and chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema. There are many references to Kane and Ambersons on this site; check the Welles category. My 1967 review of Chimes at Midnight is here, on p. 9. It’s all too obviously the work of a twenty-year-old, and it demonstrates how it’s not really that hard to write a passable movie review. But at least it’s enthusiastic about the right things.

P. S. 13 April 2015: Joe McBride writes:

And Madison Mafia made man Pat McGilligan’s upcoming biog Young Orson: The Years of Luck and Genius on the Path to Citizen Kane will have many illuminating things to say about OW’s Madison days, as well as correcting other myths.

Thanks to Joe and best wishes to Pat, whose book will appear in August. For background on the Madison Movie Mafia, go here.

P.P.S. 13 April 2015: Manfred Polak advises me that the copy of Too Much Johnson that I linked is blocked for some regions of the world. It’s available for all on National Film Preservation Foundation pages. The complete 66-min. work print we saw in Madison is here and can be downloaded here. There’s also a 34-min. edited version, downloadable here.

Thanks very much to Manfred!

Problems, problems: Wyler’s workaround

The Little Foxes (1941).

DB here:

For me, shooting is a struggle where you only get to be happy for five minutes before you start thinking about the next problem to solve.

Ruben Ostlund, on Force Majeure

One of the most famous shots in American cinema occurs at a climactic moment in The Little Foxes (1941). Regina Giddens has just learned that her sickly husband Horace has let her brothers get away with a business deal that double-crosses her. They will reap all the rewards of bringing a factory to town, while she, who engineered the deal and expected Horace to fall in line, will get nothing. Horace is already not far from death, and their quarrel in the parlor precipitates a heart attack. He spills his bottle of medicine and needs some from his upstairs supply.

Regina refuses to go fetch it, and instead Horace must stagger up and out. While she sits, fiercely waiting, on the sofa, he tries to pull himself upstairs, but he collapses on the steps. Once he has fallen, and perhaps died, she stirs to action and rouses the household.

Lillian Hellman’s original play had been a Broadway success, and this was one of the most notable scenes. How did Wyler stage it? Very oddly, as the frame up top suggests. We can’t really see Horace’s struggle on the stair. Not only does the camera put Regina in the foreground, but Horace is out of focus in the rear, at least until she rises whirling and runs to the background, the damage done.

Why did Wyler stage it this way? It depends, as Bill Clinton might say, on what your definition of why is.

Deeper, closer

1941 was the breakout year of deep-focus filmmaking in Hollywood. Citizen Kane, The Maltese Falcon, Kings Row, Ball of Fire, I Wake Up Screaming, How Green Was My Valley, and several other films set the pace for a new stylistic option. In this style, the action is staged in depth rather than perpendicular to the camera, as most scenes in Hollywood cinema were. And the camera lens creates depth of field, in which even fairly close foreground planes are just as sharp as the action in the rear. Such images weren’t unknown before; we can find them in silent cinema. But from 1941 on, depth staging accompanied by depth of focus would be increasingly common in Hollywood dramas, from thrillers and melodramas to film-noir exercises. Not all shots would be designed for maximal depth; continuity editing and closer views would still be used. But we do find such imagery becoming more common, particularly at moments of tension.

Cinematographer Gregg Toland is usually cited as a main source of this trend, and his work on Kane and Ball of Fire, as well as Ford’s Grapes of Wrath (1940) and The Long Voyage Home (1940), became models of the new look. Toland also worked with Wyler on several films, including The Little Foxes. But even without Toland, Wyler had in some films cultivated a deep-focus look (as had Ford). Coming when it did, The Little Foxes proved a powerful demonstration of the deep-focus style.

Three aspects stand out. First, there’s a certain economy of presentation. As Wyler and others pointed out, depth imagery permits directors to minimize editing. Instead of cutting from action to reaction, we see both at the same time.

Wyler suggested in publicity of the period that this gave the viewer more freedom of where to look, and André Bazin seized upon this rationale as part of his aesthetic of realism. Just as in the real world, in some films we must choose what to pay attention to.

But The Little Foxes went beyond the moderate deep focus of Stagecoach and other films to create very aggressive images. This is the film’s second novelty. Several shots place the foreground very close to the camera. As a result, we get looming faces or objects in the front plane, and we still see well-focused dramatic elements behind.

A third source of power is less noted. In The Little Foxes, Wyler found ways to make deep shots comment upon the plot. For instance, the action offers Regina’s daughter Alexandra, usually called Zan, a choice of being more like her mother (tough and vicious) or her father (tolerant and gentle). At other points Zan is paralleled to her ineffectual, alcoholic aunt Birdie. At one point, Birdie has predicted that Zan may wind up like her.

In a theatre production, there would be many staging strategies that would create these parallels, but Wyler uses a particularly striking one. One evening, while Regina and her brothers plot their scheme, Birdie has been relegated to a chair far from the discussion.

The composition diagrams Birdie’s situation in the scene and her place in the family. Then Wyler cuts in to her.

This might be seen as a bit of heavy-handed emphasis, but actually he’s doing two things. He’s making manifest her reaction, a numb resignation to being excluded. He’s also setting up, thanks to another depth composition, the chair in the hallway by the staircase. At the climax, it’s Zan, as beaten down as Birdie, who slumps in that chair.

Thanks to depth staging and deep-focus cinematography, the second image emphasizes Birdie’s solitude and prophesies Zan’s.

Which only makes my first question more pressing. Some shots of the quarrel leading up to Horace’s collapse on the stair exhibit flagrant deep focus.

We know from other shots in the film, like the Birdie/Zan comparison, that Wyler could have simply shown us Regina on the sofa in the foreground, in long shot or medium shot, while keeping Horace in focus in the background. In fact, Wyler tells us that Toland said, “I can have him sharp, or both of them sharp.” Why opt for shallow focus that makes Horace’s staircase seizure blurry and hard to see?

Fun with functions

Asking why? about something in an artwork actually veils two different questions.

The first is: How did it get there? The answer is a causal story about how the element came to be included.

The second sense of why is: What’s it doing there? That’s not a question of causes but of functions. How does the element contribute to the other parts and the artwork as a whole?

Take the second question first. You can imagine many functional reasons for Wyler’s choice. Exactly because the rest of the film keeps image planes sharp, this moment gains a unique emphasis. Horace’s collapse is marked as a major turning point in the plot. In an ordinary film, we wouldn’t notice an out-of-focus background. Here, by reverting to the more traditional choice, Wyler makes shallow focus stylistically prominent. For once in a film, a dramatic high point isn’t given to us with maximum visibility.

Another function is character revelation. In the film as a whole, we haven’t been consistently restricted to any one character. Here, Wyler could have concentrated on either Horace or Regina, or he could have given them equal treatment. An obvious choice would have been intercutting shots of Horace crawling up the steps with shots of Regina, impassively turned from him. Probably most directors would have done it that way.

Alternatively, we might have been attached to Horace, letting us see Regina in the distance. That would have diminished her reaction and played up Horace’s suffering.

Wyler’s choice puts the emphasis not on the action—thanks to the distant framing, Horace’s collapse can almost be taken for granted—but Regina’s reactions, or rather non-reactions, moment by moment. We’re made to see her turning slightly to listen to his struggles, while her staring eyes suggest that she’s visualizing the action with a horrified fascination. It’s as if her denying him the medicine was an experiment in seeing how far she could go. Now she knows. Her straining face is virtually willing her husband to die.

Keeping both this monstrous woman and her victim in focus would have divided our attention, then, and Wyler wants it squarely on Regina. He seems to have said as much in interviews.

We said we’ve got to stay on Bette all the time and just see this thing in the background, see him going in the background, but never lose her.

I wanted audiences to feel they were seeing something they were not supposed to see. Seeing the husband in the background made you squint, but what you were seeing was her face.

The second remark suggests another functional result of Wyler’s choice. By making the collapse almost indiscernible, we become very aware of what we can’t see. Thanks to selective focus, Bazin remarked, “The viewer feels an extra anxiety and almost wants to push the immobile Bette Davis aside to get a better look.” The dramatic tension of the scene finds its counterpart in our frustration to see what any other film would show us.

Finally, we should note that the staircase is an essential element in the film’s drama. Horace’s collapse is only one major incident taking place around and on it. Significantly, when Zan finally breaks free of Regina and the rest of the family, the matriarch learns of it standing on the stairs. Having all but murdered her husband there, now she sees her daughter abandon her.

Shoot my good side

The Bishop’s Wife (1948).

There are other functions we, as good critics, might seek out. For all of them, there is probably a loose causal story we’re relying on: Wyler and his colleagues made some choices that bore fruit. Some of those choices may have aimed at fulfilling the functions we notice. Other functions we notice may come along as bonuses—unintended but still benefiting the scene. Unintended consequences, good or bad, come up in art as elsewhere.

There remains the other implication of why-did-they-do-it questions: the one that seeks out quite specific causes that govern the scene. How do we tackle that?

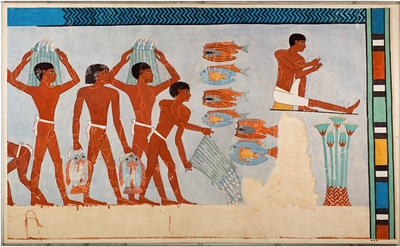

In my book On the History of Film Style, from which some of these Little Foxes observations are drawn, I argued that we can make stretches of stylistic history intelligible by thinking in terms of problems and solutions. Art historians have done this for a long while. Assuming that you want to suggest that something in the picture is farther away than something else, how do you do it? One way is through overlap, as in Egyptian art. Here the fishermen overlap the background, their legs overlap each other’s, and the strings of fish that one is carrying overlap some legs.

Later image-makers suggest variable distances through size variations, placement in the format (a little bit of that here, with the river above/behind the men), tonal contrast, atmospheric perspective, linear perspective, and other techniques. These can be considered solutions, available to artists of different times and places, to the problem of suggesting three dimensions on a flat surface.

A problem/solution way of thinking can clarify some developments in the history of filmmaking too. If you have to represent two actions taking place simultaneously, how can you do it? Crosscutting, as Griffith and others showed in the 1910s, solves that problem. It offers spillover benefits too, such as controlling pace. Similarly, there’s the problem of representing spoken dialogue. Silent films solved this in various ways—through a commenter in the theatre (the benshi in Japan), through actors voicing the roles behind the screen, and most commonly through intertitles. Later, synchronized sound solved the problem in a more thoroughgoing way.

These are very general answers to the how-did-it-get-there question. Occasionally we get more concrete information about problems and solution. For example, some Hollywood stars believed that one side of their faces was more appealing than the other. The stars with the most power could insist on being filmed on their good side, which led directors to make particular staging choices. (Claudette Colbert insisted her left side was her good side, so she’s usually positioned on screen right, with her face turned toward screen left.) David Butler knew that Edward G. Robinson likewise favored his left side, so Butler needed to stage Robinson’s one appearance in It’s a Great Feeling (1949) with him entering a scene from right to left and playing in that position.

One vain star is problem enough, but what happens when you have two who prefer being shot from the same side? According to Henry Koster, the demands of Cary Grant and Loretta Young led to the staging of the scene shown at the top of this section. (For my reservations, see the codicil to this entry.)

The Little Foxes production provides evidence of another very specific problem. In staging the staircase collapse, Wyler faced an unusual difficulty. The actor playing Horace, Herbert Marshall, had a prosthetic leg.

Marshall lost his right leg, from the hip down, in World War I. Through practice he managed to stroll quite smoothly nonetheless, and he became a significant star and featured player in theatre and films. He doesn’t need to walk much in The Little Foxes because his character is rolled around in a wheelchair. But the parlor-and-staircase scene was very demanding. As Wyler explains:

Now there was another problem involved with that, and that was the fact that Herbert Marshall has a wooden leg and couldn’t make the stairs, you see. This is a trade secret. I had him stagger in the background, get behind her and just for a moment when he gets to the stairs he had to go to a landing over there, and just for a moment went out of the picture. And a double came in and went up the stairs, staggered way behind out of focus.

Here you can see Marshall leave the foreground.

An axial cut in to Regina shows him stumbling behind her and going out of shot in the distance. This much Marshall could manage.

At that point the double stumbles into the frame and starts to crawl up the staircase.

Regina leaps up and runs to the rear, and the camera racks focus to the stair, but by now the double’s face is out of frame.

So the director solved the problem of the actor’s disability by a combination of deep staging, the use of a double, and shallow focus. This “trade secret” yielded a range of effects that, I think most viewers would agree, were vivid and exciting.

But there’s always more than one way to do anything. Given the constraint of Marshall’s artificial leg, or a player’s insistence on being shot from one side, or the leading lady’s overnight pimple, a director can work around it in several ways. One of the few critics to notice the implications of Wyler’s choice was Raymond Durgnat, a critic very sensitive to style.

Given a “pimple” or a “wooden leg,” different stylists will find different solutions. One changes the camera-angle; another introduces a last-minute panning shot; another will retain the original set-up, but throw heavy shadows to conceal the offending detail; another will interpose a pot of flowers or a table-cloth to conceal the trouble spot from the camera. The director has ample opportunity to maintain his style in the face of “accident.” And it’s no exaggeration to say that such stylists as Dreyer and Bresson would imperturbably maintain their characteristic style even if the entire cast suddenly turned up with pimples and wooden legs.

I’d add only that the director’s choices are further constrained. Beyond the immediate problem, the broader pressure of norms will kick in. The norms of classical studio lighting, cutting, and performance limit the ways Toland and Wyler can cover up Marshall’s infirmity. The norms of quality A-picture American filmmaking of the period militate against, say, editing the scene so that a dummy is substituted for Marshall on the stair. (We might get that in a serial, though.)

There are also the intrinsic norms set up in The Little Foxes as a formal whole. These favor handling the scene in depth in some way. Wyler reports the decision: “We said we’ve got to stay on Bette all the time and just see this thing in the background, see him going in the background, but never lose her.” Wyler’s earlier choices in the film created a kind of path-dependence for this critical moment. Deep-space staging could stay in tune with the rest of the film; but because of his actor’s infirmity, he could give up deep-focus cinematography. This solution created a vivid variant on the film’s intrinsic norm.

You can also argue that by deciding to call our attention to a distant plane in soft focus, Wyler fell back on something he had tried before. In the extraordinary late silent The Shakedown (1929), he showed a pie being stolen in a diner. First, there’s a close-up, then a shot of the main couple looking to the background. In the center, out of focus underneath the coffee urn, the pie is slipping away.

The action isn’t very discernible in my image, which is from a 35mm print; but the scene is shot quite soft anyway. I think audiences notice the gesture, slight as it is, because it’s centered and nothing else is moving in the frame. More visible is the background action in a shot Wyler and Toland used in Dead End (1937). Two gangsters are sitting in a bar debating kidnapping a child. In the out-of-focus background,we can discern a woman wheeling a baby carriage along the sidewalk. She isn’t the target, just a sort of reminder of children’s vulnerability. As in The Little Foxes, a centered background action attracts our attention and makes us strain to identify it.

Faced with a similar problem in The Little Foxes, Wyler had the chance to dramatize a soft-focus background to a much greater extent than in these films.

One more causal factor might have shaped Wyler’s decision. Lillian Hellman’s original play takes place wholly in the Giddens’ parlor and the hallway behind. The play text indicates that the staircase is in the rear of the set, with a landing offstage. The furniture sits downstage, closer to the audience. The foreground/background interaction in Wyler’s staging is already there, in a rougher form, in the play’s set arrangement.

And how does the play handle the moment of Horace’s collapse? When Horace’s medicine bottle breaks, Regina doesn’t move. Calling for Addie the maid, Horace leaves and staggers to the rear playing area.

He makes a sudden, furious spring from the chair to the stairs, taking the first few steps as if he were a desperate runner. Then he slips, gasps, grasps the rail, makes a great effort to reach the landing. When he reaches the landing, he is on his knees. His knees give way, he falls on the landing, out of view. Regina has not turned during his climb up the stairs. Now she waits a second. Then she goes below the landing, speaks up.

REGINA: Horace, Horace.

The foreground/background dynamic, as well as the frozen indifference in Regina’s performance, are written into the scene’s stage directions. Hellman’s instructions yield a further hint: Horace “falls on the landing, out of view.” Within the norms of the deep-focus aesthetic, Wyler and Toland found a cinematic equivalent for this barely-offstage action–one appropriate for their film’s particular style. They make Horace present, but he’s “out of view.”

Somebody may say: “See? You don’t need all this fancy analysis. At bottom, Wyler was forced to shoot the scene this way because of Marshall’s bum leg.” This retort assumes that causal factors always trump functional ones. Instead, I think that by considering causal factors, insofar as we can know them, alongside functional ones, we can better understand filmic creativity in history.

Durgnat’s point shows us how. Even when contingent circumstances “force” a filmmaker to change course, there are always several ways to do that. Picking any option brings in a cascade of other constraints and opportunities. Once Wyler has decided to double Marshall and sustain the take on Davis, soft focus is more or less necessary so we don’t spot the stand-in. But the soft-focus provides a nifty opportunity to create the sorts of functions and effects we’ve already noticed.

Like everybody else, filmmakers choose within constraints—some apparent, some less visible, many just taken for granted. Those constraints limit what can be done, but they also enable other things to happen, perhaps things that the filmmaker couldn’t have planned in advance. Once other filmmakers realize the results, they can plan in advance. A moviemaker today can try out Wyler’s solution, free of the pressures that drove him to it. A significant part of filmmaking’s traditions may consist of workarounds.

The Ostlund epigraph, apparently not available online, is taken from Hollywood Reporter’s December awards issue, p. 13. My Egyptian picture comes from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s called Fish Preparation and Net Making, from the Tomb of Amenhotep (1479-1458 BCE), as rendered by Nina de Garis Davies. I draw the stage directions in The Little Foxes from Lillian Hellman, The Collected Plays (Little, Brown, 1971), 195.

My quotations about It’s a Great Feeling and The Bishop’s Wife come, respectively from two books by Irene Kahn Atkins, David Butler (Scarecrow, 1993), 227; and Henry Koster (Scarecrow, 1987), 87. Koster’s memory fails him in his account of the Bishop’s Wife window scene. It seems likely that Loretta Young favored her left side, which is her dominant orientation throughout the film. But there’s no evidence in the film that Cary Grant favored that side of his face too. The scene at the window is too brief to count as an instance of much of anything.

When I wrote On the History of Film Style in the mid-1990s, I had the nagging memory that Marshall’s artificial leg played a role in Wyler’s staging, but I put it down as legend. (It’s a pity I didn’t pursue it, because the information would have fitted snugly into my sixth chapter.) Only when I discovered a 1972 interview with Wyler, with the “trade secret” mentioned above, did I realize there was something to the story. That interview was once online, but seems to have vanished. It’s available at Columbia University. Durgnat’s discussion is in Films and Feelings (MIT Press, 1967), 41. My other quotations from Wyler come from Axel Madsen, William Wyler (Crowell, 1973), 209.

Otis Ferguson reported on the filming of a different scene in The Little Foxes; I discuss that here. More generally, on the Bazin-Wyler connection, see this entry. Other Wyler-related entries can be canvassed here. For more on Hollywood’s development of deep staging and deep focus, see not only On the History of Film Style but also Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. As for Bette Davis’s eyelids, much in evidence here, there’s this entry.

Little things mean a lot: Micro-stylistics

DB here:

In The Sound of Fury (aka Try and Get Me!, 1951), Howard Tyler has drifted into crime under the guidance of a breezy sociopath. They commit a string of holdups, culminating in a kidnapping. Howard’s partner bashes in the skull of their young captive. Wandering drunk and despairing, Howard ends up in the apartment of Hazel, a lonely manicurist. As Howard lolls on the sofa, she turns away to switch off the radio.

The next move is up to us.

If we’re alert, we can spot, on the end table in the corner of the frame, a newspaper with a headline that may be announcing the police investigation.

At first Hazel takes no notice. Will she? She does. She lifts the paper and is appalled.

Hazel turns toward Howard. Now we can see the entire headline as she reads aloud: Police are intensifying the search. She hasn’t made the connection between her guest and the boy’s disappearance.

Panicked, Howard lunges at her and crumples the newspaper.

Will this display of shattered nerves tip Hazel off?

As in the bomb-under-the-table model of suspense, at the start we know more than both characters know. She’s unaware of the kidnapping, and he’s unaware that the cops have found the victim’s car. In addition, the arc of suspense around the headline is quite small, though it leads on to something larger: Will Howard give himself away to the unsuspecting Hazel?

I’m impressed by the economy of presentation. Hitchcock might well have treated this moment in point-of-view shots, and a fairly protracted series of them. Or imagine how several filmmakers today would have handled this scene. There’d be a slow a track-in to the headline, then a circling camera movement that first concentrates on the woman picking up the paper, then racks focus to Howard on the sofa in the background.

Instead, director Cy Endfield makes very small changes of framing and staging matter a lot. The camera simply swivels, the actress simply comes to the foreground and pivots. The entire action, crucial as it will prove in what follows, consumes only twenty-five seconds.

Some stretches of a movie tend to be simply, barely functional: connective tissue or filler. Shots show cars driving up to places where the real action will take place, or characters striding down a corridor before going into a doorway. Other images want to engage us more deeply, but they do it through immensity. They try to awe us with majestic swoops over the sea or into the sky. (Recent example: Interstellar.) But other films engage us through detailing. They train us to notice niceties.

The Sound of Fury moment creates its detailing through visual space. What about time? And what about auditory factors? Our old friend, the telephone call, can furnish some examples.

Number, please

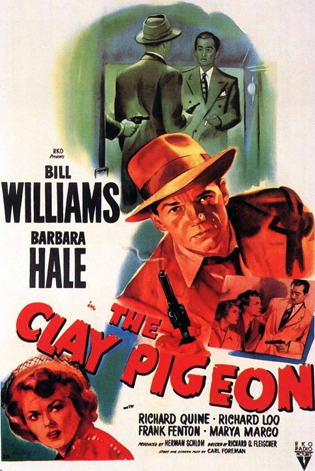

Clay Pigeon (1949).

Filmmakers must always decide how much of any action to show. Sometimes that allows the director, the cinematographer, and the editor to create fine-grained delays. These might not build up a lot of suspense but they can make us uneasy, and prepare us for a surprise later down the line.

As we mention in Film Art, and discuss in a related blog entry, a telephone scene forces the filmmakers to choose among clear-cut alternatives. Do we see both parties? Do we see only one and simply hear the other? (And is the voice of the one we don’t see futzed?) Do we see one and not hear the other at all? Most films don’t ask more than simple functionality, but even a B man-on-the-run feature like The Clay Pigeon (1949) shows what can be done with details of timing in setting up a phone call.

Jim Fletcher has war-related amnesia. He doesn’t know why he’s about to be court-martialed for treason. After escaping from the hospital, he learns that he is accused of betraying his best friend during their time in a Japanese POW camp. After convincing Martha Gregory, the friend’s widow, that he’s innocent, he searches for proof. The Clay Pigeon sticks mostly with Jim, but like most suspense films it slips in bits of unrestricted narration as well. Jim’s quest is tracked by mysterious men, and brief scenes give us glimpses of the forces pursuing him: agents of Naval Intelligence, and a gang of counterfeiters protecting the Japanese soldier who tortured Jim in the Philippines.

It’s the familiar structure of the double chase, dosed with minor mysteries. For example, when Jim gets a lead from a management firm, he leaves the office but the narration stays with the secretary who notifies her boss that Jim has been asking questions.

Cut to the executive’s office, where the camera reveals many stacks of wrapped bills on his meeting-room table. Something sinister is going on here, but what?

The decision to insert information addressed to us alone has more subtle consequences in two telephone scenes. Jim calls Ted Niles, another veteran of the POW camp. During these scenes, the filmmakers had the option of showing only Jim and never revealing Ted at the other end of the line. That tactic would have enhanced mystery, but it would have thrown suspicion on Ted. If he’s Jim’s friend and ally, why not show him?

So the filmmakers show Ted replying in his apartment. But later it will be revealed that Ted is working with the gang. The task is to introduce this important character in a way leaving open the possibility of his treachery. The solution the filmmakers hit upon is to show Ted just before he picks up the line. Here is the first instance, when Jim cold-calls him.

The camera shows Ted innocuously answering the phone and learning, to his surprise, that Jim has tracked him down.

At first Ted seems annoyed, but then he smiles and agrees to help.

The scene ends on Jim hanging up. If we wanted to plant more suspicion of Ted, we’d show him hanging up too and reacting to the call.

A later scene starts much the same way, with Ted coming in to answer a ringing phone and getting a message from Jim.

Both scenes show Ted answering the phone in a completely innocuous way. Yet the very fact of dwelling on his action of coming to the phone can be seen as planting uncertainty. In the second scene, for instance, where is he coming from? And in both scenes, Ted frowns at certain points. Perhaps he is pondering ways of helping Jim, but the expressions leave open the possibility that he is plotting against him. Ted’s duplicity is fully revealed only at the climax. (See image surmounting this section.)

In a mystery situation, a few seconds showing Ted alone gain a force they wouldn’t have in another genre. Some viewers will be surprised, some will say they knew it all along, but either way the detailing of a moment here and there has opened the possibility.

Party line

The Clay Pigeon telephone scenes show the speakers in alternation. The give-and-take of the conversation is presented by cutting back and forth. Another option is simply to show one speaker and let us hear the other without seeing him or her. As we’ve noticed, though, that would tend to make Ted a more mysterious figure.

Yet another possibility is the silent treatment: One speaker is shown talking, and we don’t hear the other at all. This option forces our attention wholly onto the reaction of the person we do see, and keeps us in the dark about the words and tone of voice of the person at the other end of the line. If the Clay Pigeon telephone calls presented Ted this way, that would be another tipoff.

Still, suppressing one half of the conversation can pay dividends when we already know the characters. At the climax of Humoresque (1947), detailing involves not a prop or a passing moment. Instead, a simple cut accentuates the shift from one sound space, that of violinist Paul Boray’s dressing room, to another, the luxurious living room of his lover Helen Wright. When he gets her call, he can’t understand why Helen isn’t at his big concert. But she is distraught because her own worries about keeping Paul’s love have been reinforced by Paul’s mother, who insists that she’s no good for him. And Helen is drinking again.

The scene’s tension is ratcheted up by first presenting only Paul’s angry questioning. We don’t hear Helen’s replies. When the dramatic momentum shifts to Helen’s desperate excuses for missing the concert, we concentrate on her meltdown more intently because now we don’t hear Paul’s replies. Her emotional response is magnified by the yearning climax of Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Overture on the radio broadcast–another reason to suppress Paul’s voice.

The scene has been split between Paul’s end and Helen’s. By not seeing Helen’s reaction to his urgent questions, we wonder what is keeping her away. Like Paul, we’re unaware of her torment. But then we see and hear her, and our inability to know what he’s saying makes his pleas seem ineffectual. Whatever he’s saying doesn’t seem to matter. A simple speaker/listener cut raises the scene to a new pitch, which will build still further when we follow Helen out onto the terrace. One more detail, brutal: We don’t hear Paul’s voice, but we do hear the click when he hangs up.

One thing that links all these Little Things: What the filmmakers did not do. Cy Endfield did not indulge in camera arabesques or POV cutting. Richard Fleischer and his colleagues did not suggest Ted’s duplicity with music or a noirish shadow. Jean Negulesco and company didn’t yield to the temptation to crosscut furiously between a panicked Paul and an anguished Helen. These directors did something rare today. They presented the situation with stylistic simplicity. That way the big moments–the revelation of Ted’s treachery in the train, the frenzied mob in The Sound of Fury, the all-enveloping climax of Helen on the beach–become more vivid. Big things need little things to seem bigger.

Thanks to Jim Healy, who introduced me to The Sound of Fury and The Clay Pigeon.

For more on the bomb under the table, see the followup entry here.

Lest someone think I’m dumping on Nolan, let’s just note that he can, when he wants, summon up niceties. (By the way, thanks to readers for hustling to our Nolan vs. Nolan entry, but they should read the one on The Prestige and our Inception series here and here to get a fuller sense of our estimation of him. All of these are put into reader-friendly order in an insanely inexpensive ebook…..)

Several other blog entries consider detailing in performance: Henry Fonda’s hands, Bette Davis’s eyelids, and the facial expressions in The Social Network. I’m still mulling an entry on eyebrows, which are terribly underrated. For another Joan Crawford tour de force, there’s this.

Humoresque (1947).

Gone Grrrl

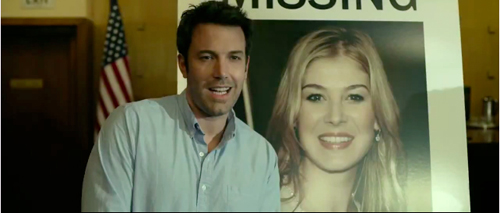

Gone Girl.

DB here:

How are contemporary movies, even this weekend’s releases, indebted to earlier traditions? Sometimes Kristin and I tackle this question. We’re not (I hope) trying to impress you as connoisseurs of esoteric knowledge. We’re definitely not trying to play down a movie’s originality by yawning and shrugging and murmuring “We’ve seen it all before.” Instead, as historians of film forms and styles, we’re interested in the ways that current movies reconfigure techniques that have been circulating across cinema history.

A lot of those techniques involve storytelling. So we’re obliged to study narrative conventions and innovations across the decades. And since cinema isn’t sealed off from other media, we’re curious about how films borrow narrative devices from other arts. The borrowing isn’t only one-way, of course; cinema has influenced storytelling in other media too.

Mystery and suspense stories have long attracted people who study narrative (“narratologists”) because such fictions depend almost completely on storytelling subterfuge. True, other genres can include false leads, or misleading ellipses, or questionable flashbacks, or strange point-of-view switches. But mystery-based plots require them in a way that science-fiction or romance plots don’t. In mystery stories, characters keep secrets from each other and the author must keep secrets from the audience as well.

Which brings us to Gone Girl.

Detective stories and thrillers are one-off demos of narrative trickery, so studying them can teach us something about how we understand stories. We’ve made a stab at showing this elsewhere on this site (see our codicil). But now comes a flagrant instance of narrative manipulation that has set people talking ever since Gillian Flynn’s novel was published.

That novel and the film she wrote and David Fincher directed throw into relief how popular narratives revise devices from earlier traditions. As narratologists in training, we’re keen as well to understand how the film creates its particular effects. I can’t answer all such questions here, but I offer some thoughts on the film’s storytelling strategies, with notes on how those adapt earlier ones.

Of course beyond this point there are spoilers for Gone Girl. I also heedlessly spoil Leave Her to Heaven, both book and film.

Two plots for the price of one

The domestic thriller usually involves a couple living together—a husband and wife, or in modern times a pair of lovers. The conflict might center on them or on a third threatening figure. A very common option focuses the plot on either a murderous husband or a murderous wife.

Gone Girl, both novel and film, starts with a classic murderous husband situation. Amy disappears. She has made her husband Nick discontented and angry, and he has started an affair with one of his students, Andie. Thanks to a crucial ellipsis in showing the first day, what Nick has been doing during Amy’s disappearance is skipped over. When Amy vanishes, apparently leaving a pool of blood behind, Nick is the prime suspect.

If your plot centers on a murderous husband, you have a choice. You can let the audience in on his plans, as in Rage in Heaven (1941), Conflict (1945), The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947), and, much more recently, Safe Haven (2013). But Gone Girl doesn’t unequivocally show that Nick has killed Amy, or even plotted to kill her.

The second alternative for handling a murderous-husband situation is to keep it mysterious, chiefly by confining us to the wife’s range of knowledge. This ploy was made famous in Francis Iles’ novel Before the Fact (1932) and in Hitchcock’s adaptation Suspicion (1941). The premise is: I think my husband is trying to kill me. The 1940s crystallized this plot format in films like Secret Beyond the Door (1948) and Sleep, My Love (1948), and it survived for decades, in films from Sleeping with the Enemy (1991) to Side Effects (2013).

The first half of Gone Girl uses Amy’s diary entries to present the familiar arc of suspicion. The Dunnes’ marriage frays and she becomes increasingly frightened. Just before their fifth anniversary she buys a gun for self-defense. In her last entry she records her fear that he will kill her.

Nick looks pretty guilty at first, but with the whiff of doubt, another convention kicks in. That’s the one that film scholar Diane Waldman has called the “helper male.” If there’s another man nearby able to rescue the wife and play the role of a future romantic partner, then the husband is likely to be exposed as villainous. Examples are the Hollywood version of Gaslight (1944) and Sleep, My Love. If no helper is visible, then we’re likely to have a plot based on the wife’s misperception of the husband, as in Suspicion and Secret Beyond the Door. In Gone Girl’s first half, Amy seems to have no recourse to a helper male. This fact might dissolve some suspicion attached to Nick. Maybe, some viewers might ask, Amy was indeed abducted by a third party?

So much for the convention of the killer husband. A second type of domestic thriller, rarer than the first, centers on a homicidal woman. She shows up in the great Vera Caspary’s novel Bedelia (1945; made into a British feature in 1946) and in such films as Ivy (1947), A Woman’s Vengeance (1948), and Too Late for Tears (1949).

An especially shocking 1940s specimen of the killer wife is the cool, irresistible Ellen Berent in Leave Her to Heaven (novel 1944, film 1945). At first, Ellen wishes no harm to her husband Dick; she just wants to eliminate anybody with whom she’d have to share him. She lets his little brother drown, and, fearing that her unborn child will come between them, she flings herself downstairs and induces a miscarriage. Eventually, though, she turns her wrath on Dick. (Ellen’s most extreme tactic I’ll save for later, as it looks forward to Gone Girl.)

An especially shocking 1940s specimen of the killer wife is the cool, irresistible Ellen Berent in Leave Her to Heaven (novel 1944, film 1945). At first, Ellen wishes no harm to her husband Dick; she just wants to eliminate anybody with whom she’d have to share him. She lets his little brother drown, and, fearing that her unborn child will come between them, she flings herself downstairs and induces a miscarriage. Eventually, though, she turns her wrath on Dick. (Ellen’s most extreme tactic I’ll save for later, as it looks forward to Gone Girl.)

What is exceptionally clever about Gone Girl, again both novel and film, is that its second half replaces the murderous-husband schema with a revelation of Amy as a spider woman. Angry with Nick’s failure to sustain the role of the man she wants him to be, she has elaborately prepared an apparent murder that will lead police to suspect him. Here Flynn revives an old reliable of mystery plots, the faked death.

Amy has dovetailed three sets of clues for the police. There are clues she leaves in the treasure hunt, a little-girl game she obliges Nick to play every anniversary. This time, though, the hints point to uncomfortable aspects of their relationship. A second array of clues—imperfectly cleaned bloodstains, obviously faked signs of abduction, big credit-card purchases in his name—make Nick seem a lying killer. Then there is Amy’s faked diary, which she arranges to appear at just the moment that would harm him most. The diary entries initially coax us toward the Suspicion situation, seeming to provide a record of a wife’s growing apprehension of danger.

Knowing that a dead body will clinch the uxoricide case against Nick, Amy initially considers doing away with herself and letting the corpse be found in the river. Interestingly, this vindictive-suicide motif is the extreme tactic Ellen Berent pursues in Leave Her to Heaven. She poisons herself and sets up her sister Ruth, who’s in love with Dick, as her murderer. Like Amy, she has left a damning testament behind: a letter that will lead the police to arrest Ruth. Like Amy, Ellen has dropped a judicious trail of clues prepared well in advance.

So Flynn’s novel and screenplay shrewdly couple two thriller plot schemes, the murderous husband and the lethal wife. As an extra fillip, once Amy has been robbed by the desperate Jeff and Greta, she calls rich Desi Collings and convinces him of the threat Nick supposedly represents. In effect, Amy re-launches the lethal-husband scenario and recruits Desi as her helper male. Of course in most such plots, the helper male rescues the woman from peril. Here she is the peril.

Thank you, Mr. Griffith

So far I’ve talked mostly about what I called, in an earlier entry and in an online essay, the story world. But I couldn’t keep clear of two other dimensions of film narrative: plot structure and narration. I’ll talk about these more now.

I’ve indicated that Flynn’s novel breaks fairly neatly into two halves, splitting when Amy reveals that she hasn’t been kidnapped or killed. (“I’m so much happier now that I’m dead.”) The film, though, is a little less tidy.

As recidivist readers of this site know, Kristin has proposed that for decades Hollywood feature films have tended to break into several distinct parts that don’t fully correspond to the three acts of screenwriting manuals. The core structure for a normal feature involves four parts. Kristin labels these the Setup, the Complicating Action, the Development, and the Climax, with a brief epilogue tacked on. They’re determined by turning points that alter the goals that the characters pursue, and they tend to run twenty-five to thirty minutes or so.

Kristin argues in Storytelling in the New Hollywood that short films can delete a middle chunk, and long films can iterate one. For instance, she finds that Amadeus has two Development sections. Picking up on this, I proposed in The Way Hollywood Tells It that The Godfather (a very long movie) has not only two Developments but two Complicating Actions.

The film version of Gone Girl offers an interesting extension of the basic pattern. The film runs 144 minutes without credits. I divide up the first 126 minutes according to major turning points.

Setup. After the prologue close-up of Amy, she goes missing and Nick begins to conceal things from the police (roughly the first half hour).

Complicating action, in which the main character conceives a new goal. Now that public opinion casts Nick as the killer and Andie becomes another secret he must conceal, he must try to convince all he’s innocent. He fails. Boney summarizes the case against him at about 60 minutes in. Then he discovers the luxury goods stuffed into his sister Margo’s shed and he realizes that he’s been set up.

Development, in which backstory is provided, the protagonist confronts more problems, and many delays are set up. As Amy drives away from town and assumes a new identity, her Cool Girl monologue confirms for us that she has framed Nick. She hides in the motor court and strikes up an uneasy friendship with Greta and Jeff. While Nick engages Tanner Bolt as attorney and learns of Amy’s earlier framing of O’Hara, Amy calls Desi Collings for help. Nick has agreed to go on Sharon Schieber’s show.

Once we learn that Amy has faked her diary and loaded it with lies, we follow her stratagems after the first day. Gradually her life on the road syncs up with the progress of Nick’s situation, so that via crosscutting they eventually watch the TV coverage simultaneously.

Development sections tend to run a little long, and this one needs a chunk of backing-and-filling to explain Amy’s scheme. This part ends, I think, around the 104-minute mark, when Andie at a press conference confesses her affair with Nick while Amy accepts sanctuary at Desi’s lake house. Now Nick must take the initiative and fight back, while Amy must concoct a new plan for her new circumstances.

Climax: Here a plot culminates in success or failure, goals definitely achieved or not. Nick does well in his Sharon Schieber interview, but almost immediately the police discover the loot in Margo’s shed and confront him with the diary. He’s arrested. It’s his darkest moment so far. Meanwhile, Amy has become Desi’s prisoner. But Nick’s TV performance has convinced her that he’s ready to resume playing her ideal man. Accordingly, with typically surgical preparation, she kills Desi and returns home, announcing her escape from sex slavery. She comes back at about the 126-minute mark.

Were this a normal film, things would end here, with the couple restored; we’d need only a gloating tag showing humiliated police. Amy’s revelation of her scheme at 65:00 would then become a neat midpoint. But the film has almost twenty more minutes to run.

Is this section a protracted epilogue? Some viewers seem to take it as such, and to find it draggy, but it’s structurally necessary. I think it’s fruitful to see Gone Girl as having two climaxes.

Two climaxes for the price of one

The double climax in Gone Girl, I think, occurs because the film has a tandem structure from the start. The first hour alternates scenes involving Nick’s search for Amy with brief flashbacks triggered by shots of Amy writing in her diary. The diary supplies what we initially take to be exposition about their meeting, falling in love, getting married, losing their jobs, and moving to Missouri. These past scenes are sandwiched in between present-time scenes of the inquiry into Amy’s disappearance. The Griffith of Intolerance, not to mention the Christopher Nolan of The Prestige, would enjoy the extent to which book and film rely on large-scale crosscutting between protagonist and antagonist.

The duplex story lines lead to two turning points, one assigned to each major character. At 65 minutes, Nick’s discovery of the fancy purchases in Go’s shed changes his goal: He now must prove that Amy has set him up. At the same juncture, the revelation that Amy is on the road sets up her new goal of escape—at first, she thinks, to suicide but then to a life free of Nick, who seems safely en route to the death house.

Given the dual line of action, we have a first climax that puts Nick in jail and shows Amy killing Desi, which ends her flight. Her return provides a first phase of resolution for the overall action: Back home, she spins a new narrative for the media, one in which she “fought her way back” to her husband.

But we don’t have full resolution. Nick still has the goal of proving that Amy faked her disappearance, and now he must also show that she murdered Desi in cold blood. In addition, his rage against his wife’s frame-up threatens to make him the homicidal husband she painted in her diary. Will he be driven to kill her, as he sometimes indicates he’d like to? Meanwhile, Amy’s goal of reunion isn’t fully achieved. She still must evade punishment (Boney the cop is suspicious) and she must also persuade Nick to back up her rigged story of his abusive and spendthrift ways.

So a second climax shows Amy thwarting Nick’s goals. She blocks his efforts to reveal the truth and won’t allow a divorce. She retained Nick’s stored semen when they were trying to conceive a child, and she has impregnated herself. She will keep his son from him if he tries to make trouble. Nick accepts her frame-up and the couple become, as he says in their final TV interview, “partners in crime.” If you assume that Nick is the film’s protagonist and Amy the antagonist, we have that rare mainstream movie in which the antagonist wins.

Some critics have called the book and the film Hitchcockian, and film geeks will notice the midpoint giveaway as similar to that in Vertigo. More generally, the complicit couple exemplifies the transfer-of-guilt dynamic we find in Shadow of a Doubt, Strangers on a Train, and other of the Master’s films.

But this last quality isn’t unique to Hitchcock, or Flynn-Fincher. In Leave Her to Heaven, Dick becomes an accomplice to Ellen’s act of drowning his brother. He keeps quiet for the sake of the child he thinks she is carrying. As a result, the novel gives us a passage that could come straight from Gone Girl, on the page or on the screen.

And she said in serene and level tones: “But you lied to protect me, so—we share the guilt. That binds us together. We can never escape that now.” After a moment she added: “So we must go on together, wearing a mask for the world, being honest only with ourselves.”

Look who’s talking, or not

In both film and novel, Gone Girl’s large-scale plot patterns—the wedged-in diary entries, the ABAB attachment to characters, the cross-stitched timelines—are enhanced by choices about narration. I take narration to be not only voice-over sound but the moment-by-moment flow of story information. That flow is regulated by cinematic techniques, orchestration of point of view, and kindred strategies.

Now we encounter some differences between film and literature as storytelling media. For instance, in the novel the parallel plotlines are rendered in first-person narration, alternating accounts from Nick and Amy. Amy’s fourteen diary entries are motivated as the sort of things one enters in a private journal, whereas Nick’s aren’t presented as him telling anyone his tale. When Amy’s diary is revealed as a hoax, she continues to recount events, and still in present tense, as if she couldn’t shake the habit. Nick, however, continues to tell us what happened in the past tense. This sort of difference is rather hard to achieve in film, unless you have two continual voice-over narrators. This option Flynn and Fincher decline, probably in the interests of clarity.

Both the alternation and the variation in tense have a long novelistic past. Dickens’ Bleak House (1853) switches between chapters in third-person narration in the present tense and chapters in first-person past. The device of alternating viewpoints was picked up in twentieth-century modernism (notably Faulkner’s books) and popular genres as well. A simple example is Philip MacDonald’s 1933 mystery, X v. Rex, which switches between first-person letters written by a serial killer to the police and third-person accounts of the efforts to track him/her down. Somewhat fancier is Anita Boutell’s Death Has a Past (1939), which takes a series of scenes transpiring across one week and sandwiches among them bits of a confession written by the killer afterward—“flashforwards,” in effect.

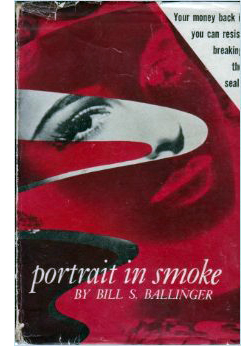

To go back to Leave Her to Heaven, Ben Ames Williams’ original novel alternates chapters filtered through the consciousness of husband, wife, brother, and sister, although all are treated in the third person. At about the same time, mystery writer Bill S. Ballinger gained notoriety for alternating chapters told from two characters’ viewpoints in two different time frames. Examples are Portrait in Smoke (1950) and The Tooth and the Nail (1955), the latter of which also toggles between first- and third-person discourse. More recently, in novels like Rebel Island (2007), Rick Riordan has intercut first- and third-person chapters.

To go back to Leave Her to Heaven, Ben Ames Williams’ original novel alternates chapters filtered through the consciousness of husband, wife, brother, and sister, although all are treated in the third person. At about the same time, mystery writer Bill S. Ballinger gained notoriety for alternating chapters told from two characters’ viewpoints in two different time frames. Examples are Portrait in Smoke (1950) and The Tooth and the Nail (1955), the latter of which also toggles between first- and third-person discourse. More recently, in novels like Rebel Island (2007), Rick Riordan has intercut first- and third-person chapters.

Journals and assembled documents have been one standard way that classic novels have been organized, and shrewd writers have exploited many possibilities. I think of the moment in The Woman in White (1860) in which a long and engrossing account written by a character in peril is revealed, only at the end, as being read by her adversary. More specifically, a major Flynn trick—the discovery that the diary mixes reliable accounts of events with false ones—has one major precedent. It occurs in a famous 1938 mystery novel that, for once, I will not spoil by naming. Here the diary in the first section is intended to be found by investigators and to cover up the identity of a killer.

This isn’t to call Flynn unoriginal; she has come up with a new variant of these narrational conventions. The point is simply that once you work in the realm of the mystery thriller, you will probably be seeking out ways to mislead the reader, and some of those stratagems will have a kinship with your predecessors. More generally, all narrative traditions exfoliate. Storytellers are constantly experimenting with new ways to engage us, and it would be surprising if two authors, both bent on achieving similar effects, didn’t occasionally hit on similar devices. Just as Flynn welded together two domestic-murder plot premises, she recast traditions of shifting, unreliable narration.

In the novel, the two first-person accounts, Nick’s and Amy’s, restrict our knowledge to each one’s perspective. Which isn’t to say that each is transparent. Nick will sometimes report his dialogue with the speech tag, “I lied.” This teases us to wonder what he’s holding back from the cops. Interestingly, confessing lies makes him a more reliable narrator, because he’s confiding in us. This has the effect of making us trust his claims about wanting children, not beating up Amy, and so on. By contrast, Amy’s chipper narration seems completely open about her feelings, but many of those entries are revealed as part of her murder masquerade. Her unreliability, though, seems chiefly confined to the diary entries; once she’s on her own, she seems to be reporting her sociopathic reactions sincerely.

Because the novel restricts us to the two main characters, we can’t know what’s happening outside their ken. Something similar happens to the attached viewpoints in Leave Her to Heaven, in which Dick and Ruth only gradually learn how his wife Ellen plotted to make her death seem to be murder. In adapting the novel to film, screenwriter Jo Swerling respected the novel’s systematic attachment to characters to a surprising extent.. First we are mostly with Dick, but at crucial points we’re given blocks of scenes organized around Ellen. Unlike the book, the film version shows us her executing her plan to implicate Dick and Ruth in her death. Here, for instance, Ellen puts arsenic in the sugar bowl that Ruth will use to sweeten Ellen’s coffee.

The film Gone Girl doesn’t give Nick a pervasive narrating voice as the book does, and we aren’t wholly restricted to his range of knowledge. On several occasions we watch the police making discoveries that he’s not aware of. Crucially, we see them find the diary some days before they tell him about it. As so often happens, mainstream film introduces some unrestricted narration, which yields suspense rather than surprise. Amy narrates the eight diary entries which introduce flashbacks, some of which turn out to be false ones. But once she finishes her Cool Girl monologue after the big turning point, we don’t, I think, hear her voice-over again.

Nick’s voice-over enters only twice, with carefully symmetrical effect. The film’s first shot is a close-up of Amy turning toward us as a hand strokes her head. Nick’s voice talks of wanting to split open her skull, unspool her brain, and find the answer to married folks’ perennial questions. “What are you thinking? What are you feeling? What have we done to each other?”

Most broadly the shot has the effect of rendering this beautiful woman mysterious. It also suggests a violent impulse in an uncaring, obtuse male—the sort of scenario that would lead to the murderous-husband plot that hovers over the film’s first hour. The final shot of Gone Girl repeats the close-up, and Nick asks his questions again but adds, “What will we do?” Now we know how devious that brain is, and how much justified anger the man speaking may be feeling toward her. Perhaps, after the movie ends, he will be ready to kill her. The two shots, unanchored in story time, bracket the movie with the central duality that the plot and the narration will enact: a potentially murderous man and an innocent-appearing but lethally dangerous woman.

There’s much more to be said about the film and the novel. I haven’t touched upon Flynn’s subject matter—what we might call Yuppies 2.0, the brain-entitled Net-enabled cool kids—and her theme of marriage as a struggle to play the role your partner cast you in. Issues like these have ingeniously set readers talking about marriage’s putative dark side and how men can feel “picked apart” by dazzling, demanding women. For my money, the presence of this brilliant, beautiful Crazy Lady, another legacy of the 1940s, favors Nick’s side of things. He’s a weasel but not as dangerously nuts as his wife. Your mileage may vary, for reasons I attribute to Hollywood’s perennial urge to cover every bet on the board.

We’d also want to consider the novel’s style, which offers caffeinated versions of Product Placement Realism and Vivid Writing, in both male and female registers. The screen version loses this aspect of the novel, and we get instead Fincher’s calm, polished direction. Too many shots of vehicles pulling up to buildings, I suppose; but if everybody laid out scenes as slickly as Fincher does we wouldn’t complain so much about our movies. I admired in particular the virtuoso sequence accompanying Amy’s Cool Girl monologue. Her eloquent rant runs underneath a crisp replay of her scheme and then supplies a montage of her trip and her change of identity, with glimpses of female types illustrating her diatribe. This passage is a good example of the crackling pace of the movie, which, thanks to smooth hooks and concise exposition, rushes along at just the speed of our comprehension.

Consider as well the economy of a single moment, when Greta and Jeff steal Amy’s money. At one level, the couple serves purely a plot function, one typical of a Development section: new problems, often overcome, serve to delay the climax. (Another plot construction would have had Amy simply lose her money and call Desi right off, shortening the movie by quite a bit.) The confrontation in the motel also serves a thematic function, contrasting Amy’s sheltered life with another social level she both detests and fears, as well as giving us another couple to compare with Amy and Nick. (Interestingly, in the Greta-Jeff pairing, it’s the woman controlling the man.) The moment I have in mind, the instant when Greta slams Amy’s face against the wall and says, “I don’t think you’ve really been hit before,” fulfills even more purposes. The whack (a) shows that Amy’s new identity is easier to see through than she thinks; (b) reminds us that her diary reports of being beaten by Nick are false; and (c) engenders a certain sympathy for her, invoking the classic woman-in-peril situation. This tight packing of implication and emotion into an instant is characteristic of classical studio storytelling. It exemplifies the unfussy efficiency celebrated by Otis Ferguson and Monroe Stahr.

My purpose here has simply been to indicate that we can usefully understand any plot as a composite of possibilities that surface in other plots. In a way, I’m revisiting ideas floated in my Shklovsky/Sondheim entry months ago. Again, this isn’t to put down Gone Girl as formulaic. Instead, it’s to suggest that any narrative we encounter in the mass-market cinema (and probably in other forms of filmmaking) is part of an ecosystem, a realm offering niches for many varieties—including hybrids.

Thanks to Kristin, David Koepp, and Jeff Smith for conversations about Gone Girl.

For comprehensive accounts of mystery and detective fiction, visit Mike Grost’s encyclopedic website. Relevant to today’s entry is my web essay, “Murder Culture,” and my entry comparing Safe Haven and Side Effects. Film Art: An Introduction includes a section on various forms of the thriller in Chapter 9. And don’t get me started on the relation between Gone Girl and one of my favorite domestic thrillers, Double Jeopardy.

The distinctions among story world, plot structure, and narration that I use here are explained in two other items: the chapter, “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative” in Poetics of Cinema, available on this site; and the analysis of The Wolf of Wall Street illustrating that argument.

Diane Waldman outlines the role of the helper male in her article “‘At last I can tell it to someone!’ Female Point of View and Subjectivity in the Gothic Romance Film of the 1940s,” Cinema Journal 23, 2 (Winter 1984), 29-40.

For more on four-part plots, go to Kristin’s entry here and the essay “Anatomy of the Action Picture.” I’ve argued in another entry that popular novels can be built upon the four-part structure Kristin outlines, and it’s interesting to compare them with film versions that follow the same template. My examples were The Ghost Writer and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Fincher version). I think that Flynn’s novel is built on a five-part armature roughly comparable to that of the film. As for double-climax plots, I argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It that In Cold Blood is another instance of this structure.

A more intricate use of diary narration in film is Nolan’s The Prestige, which derives from the even more intricate deployment of it in Christopher Priest’s original novel. We discuss the film in Chapter 7 of Film Art: An Introduction, and there’s a bit about the novel here.