Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

The AMBERSONS Poster Mystery: The clincher

DB here:

Bingo! Crowdsourcing pays off. Alert blogger Ivan Paio found the original poster that’s tucked into the Magnificent Ambersons frame! It confirms that Welles used not a film poster but one advertising a stage show…that could have played the Bijou in 1912.

If you’re not familiar with our quest, you can go here and here and here. Be sure to visit Ivan’s site for details, and give him a big hand.

Breaking AMBERSONS news: Did you say Buried?

DB here, again and still:

Still, until somebody comes along with a better account, I’m ready to believe that we’ve found the film.

That’s me, just two days ago. I suggested that the mystery poster tucked into the corner of one shot in The Magnificent Ambersons is the Pathé release of 1912, The Cow-Boy Girls. Readers with long memories and no life of their own will recall that this question has bugged me since my earlier post in May. Last week my colleague Eric Hoyt suggested what the title might be, and some rummaging in various sources, particularly the invaluable Lantern database, seemed to confirm it.

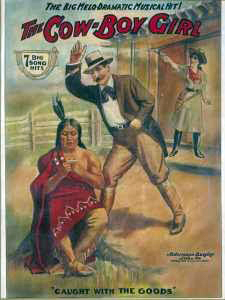

To recap: Here are two blow-ups from a 35mm print, showing the two angles from which Welles’ camera captures the poster. The text is clearer in the half-size one, but the more distant one yields a fuller view. The poster seems to depict a man thrashing an American Indian, with a young woman, arm outstretched, in the rear. Note also the shield-like triangular shape underneath the title on the first image.

Last night came word from two more vigilant correspondents, each with new evidence–again, unearthed by the light of Lantern.

My first correspondent was Luke McKernan, early film specialist and master builder of the vastly informative website The Bioscope. Luke has stopped posting there, but he continues to write keenly on cinema at lukemckernan.com. His message to me runs as follows:

Dear David,

I have struggled and struggled with this one til I’m at the point of worrying about my eyesight. I don’t think it can be The Cowboy Girls, but searching for the keyword Cowgirl might be productive. I found this in the Lantern site, searching for ‘cowgirl’ and 1912:

http://lantern.mediahist.org/catalog/movingpicturenew05unse_0122

It’s not the right film, but the still is quite close to that in the Ambersons poster, which at least gives encouragement.

Luke

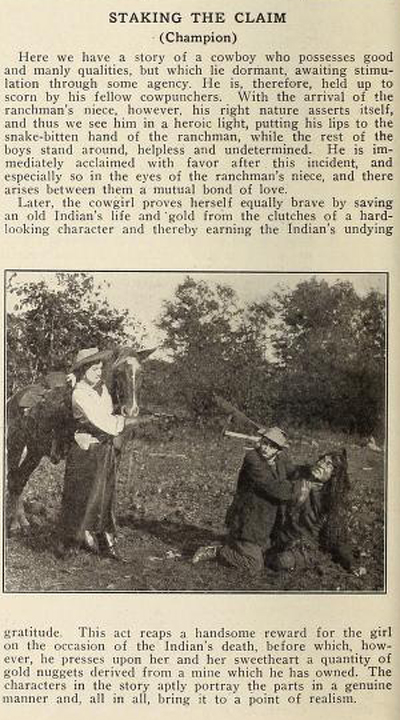

The entry Luke refers to is this one, from The Moving Picture News of 1912.

The picture shows the situation we find in the Ambersons poster. But as Luke says, our poster’s title clearly is not Staking the Claim. More research, as we academics say, is needed.

Just a few hours later came this from another colleague here at Madison, Ph.D. candidate Eric Dienstfrey.

Hi David,

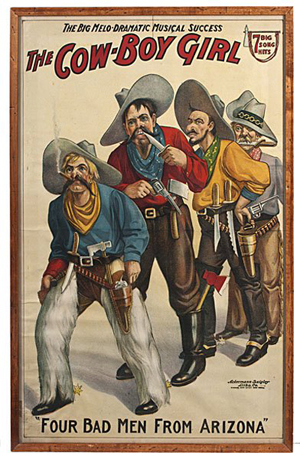

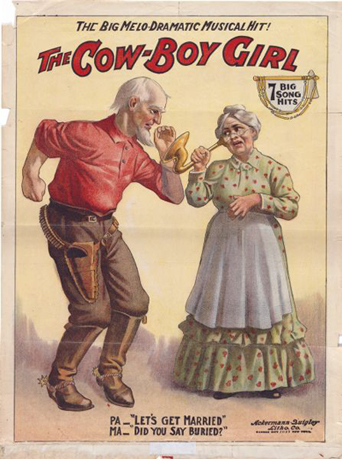

Reading your post on Ambersons now, I remember coming across the title The Cow-Boy Girl while researching stage musicals that were contemporary to Gottschalk’s The Tik-Tok Man From Oz and The Patchwork Girl of Oz. You are absolutely correct, the poster does say “The Cow-Boy Girl” but it was for a theatrical musical, not a film… at least I don’t think so. (But many films were probably called Cowboy Girl too.) I’ve attached two different posters from the musical that I found online. The triangle shield is not the Pathé rooster after all!

I hope you find this interesting/useful… or better yet, I hope this brings you a little closure.

Cheers,

Eric

I had mentioned on Saturday that there was a stage show called The Cow-Boy Girl, and I wondered whether the poster was promoting not a film but the theatre piece. In the end, I went with a film title. But Eric D’s visual evidence of the title font and the triangular motif (not a shield but a swag curtain, I think) strongly suggests that we’re dealing with a play. It would be characteristic of a theatre in 1912 to include vaudeville, stage shows, and other live entertainment alongside movies.

The Cow Boy Girl (no hyphen), a thirty-minute playlet including songs, was reviewed, unfavorably, by Variety (29 October 1910). The review doesn’t mention a scene like that depicted on the poster.

Other sources lists touring shows of The Cow-Boy Girl (with and without hyphen) from 1910 onward, so it might well have been playing the Bijou in the Ambersons’ town in 1912. Actually, Eric D. has found that it did play another Bijou. The Billboard of 18 February 1911 lists the following:

How can you argue with something that played the home of thrillers?

Are we there yet? Until we find a copy of the poster itself, I’m inclined to think so. But as Luke’s discovery indicates, we’re dealing with a period in which imagery, titles, and situations were copied and circulated in great profusion. In 1912 plenty of cowgirls and cowboys and cowboy girls and cow-boy girls were swarming over American entertainment. More or less like superheroes today.

No research project is finished, only abandoned. Thanks to the Fussbudget Team for playing!

The Fussbudget Report: An AMBERSONS solution

DB here:

Some readers may recall my post on The Magnificent Ambersons back in May. I argued that Welles built a sense of the irretrievable past into many aspects of the film’s narration. He used the voice-over commentary to evoke times gone by, but also ellipsis, offscreen action, constant recitation of memories, and other strategies. In addition, there were moments of cinephile nostalgia, including the iris shot at the end of the snow scene and the concluding credits of the actors slowly turning to face the audience, as in the manner of films of the 1910s.

Then there were the movie posters. George and Lucy are walking through the town. He’s about to leave for Europe, and she feigns a polite lack of concern. They pass the Bijou movie house, which flaunts several posters. I managed to identify all but one, the one tucked in the lower right of the frame above. I just couldn’t properly read the title, even on a good 35mm print.

Blown up from 35, the clearest view we get of it looks like this.

I thought it might be The Coin-Box Girl, but no such film title existed. Some readers– Jacopo Pes, Ivo Blom, and Paolo Cherchi Usai (thanks to all)–proposed some possibilities. Alas, none of their suggestions seemed to fit. Even running through the Library of Congress copyright listings for films didn’t yield a plausible candidate.

Over a lunch with colleague Eric Hoyt last week (Eric is one of the geniuses behind Lantern), we talked about this. Eric had access to a bigger list of titles than that of the LoC, and he suggested that the first words might be cow-boy. Checking his list, we find that there was indeed a May 1912 Pathé release called The Cowboy Girls. It’s also listed in Lauritzen and Lundquist’s American Film-Index 1908-1915 under that name. It might well have been postered as The Cow-Boy Girls. (We now assume that the squiggly line after “Cow” is a hyphen. It might be just a really curly w.) An April 1913 ad from the Carbondale Daily Free Press lists a film called The Cow Boy Girls, so if it’s the same movie, there was some freedom of punctuation around it.

I left the second ad underneath so you can appreciate having electricity.

It would be very nice to check a poster of the film, but I haven’t found one. Here, though, is a synopsis from Moving Picture World of 1912. (Again, thanks to Lantern.)

This doesn’t quite match the image on the poster, which shows a man apparently about to strike a Native American kneeling before him. But in the background, more visible in the half-framed poster, there seems to be a young woman coming out of a cabin protesting, and perhaps brandishing a pistol. (Open Carry applies here.)

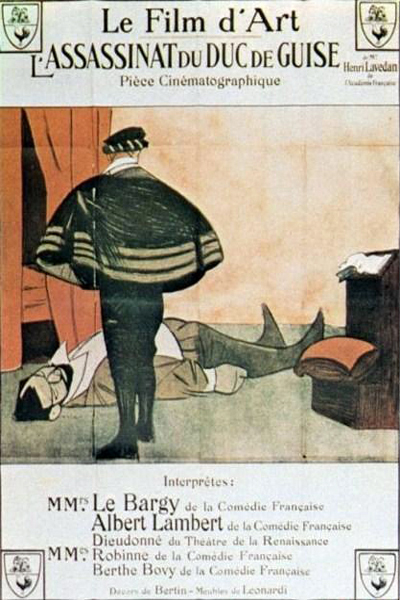

There are other anomalies. If this is indeed The Cowboy Girls from Pathé, does the triangular shield logo in the northwest corner boast a rooster? Some Pathé titles did, as for this 1908 French release (one of the most important films ever made). On the four shields, the rooster (also to be seen as decor in Pathé interiors) is joined by the eternal symbol of the theatre, the comic and tragic masks.

And if The Cowboy Girls is a Pathé title, did the Carbondale ad list it as “Essany” (Essanay) by mistake? Or is that a different cowgirls movie? It may be relevant that there was a vaudeville play called The Cow Boy Girl, which was touring at the same period. Filmmakers may have tried to cash in on that. Or maybe the Ambersons Bijou was presenting that stage show rather than a film?

Still, until somebody comes along with a better account, I’m ready to believe that we’ve found the film. The clincher for me is the Cowboy Girls’ date: 1912. Except for the fake lobby card promoting a nonexistent Jack Holt movie, all the discernible film posters in the Ambersons scene are from 1912 releases.

This obsessive synchronization is surely the work of a film nerd, either Welles or a staff member. Geek calls out to geek, from 1912 to 1942 to 2014. See? I’m not the only fussbudget here.

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942).

The 1940s are over, and Tarantino’s still playing with blocks

Pulp Fiction (1994).

Trigger warning: This blog is about Quentin Tarantino, Walt Disney, and Henry James. Those who find violent analogies disturbing should avoid what follows.

DB here:

Every narrative film is made out of parts. Normally they just whisk by us, but sometimes our attention is called to them as parts. Occasionally, we sense that the whole movie is made out of large-scale chunks.

Take Pulp Fiction (1994). It consists of scenes grouped into larger blocks, some marked by fade-ins and outs and others with titles, like chapters in a book. The diner opening is set off as a unit before the credits. The ensuing visit of Jules and Vincent to the apartment of the welshing punks is ended in a fade-out. We then get a section tagged “Vincent Vega and Marsellus Wallace’s Wife.” After that portion fades out, there follows a sequence introducing the young Butch as a boy, presented with his father’s gold watch. Then Butch, now grown up, heads out to the boxing match. Another fade, and we get a title, “The Gold Watch.”

That could be seen as simply a belated chapter head for the entire Butch section, boyhood and prizefighting career. Or it could mark the start of another, much longer block: the aftermath of the fight and Butch’s flight from Marcellus Wallace. Either way, the sense of a film composed of large-scale parts is very strong. As the film goes along, we realize that each block tends to concentrate on certain characters and provide distinct, sometimes overlapping, stretches of time.

For many viewers, I suspect, Pulp Fiction was their introduction to strategies of block construction in movies. Those of us studying film history had seen it in various guises before, but seldom so cleverly and explicitly worked out as in Tarantino’s film. And I’m not sure even film historians realized how much Tarantino owed to earlier traditions.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I suggested that some of the experimental trends in 1990s-2000s cinema were indebted to Hollywood in the 1940s. This is especially evident in the neo-noir films of those years, like The Underneath (1995), The Usual Suspects (1995), and Memento (2001). Now that I’m writing a book on that earlier period, I realize that studying the 1990s films, has led me to think about something that I hadn’t noticed—how interested 1940s filmmakers were in building movies out of blocks.

Turns out that the 1940s was a kind of golden age of block construction. And Tarantino serves especially well to illustrate how that strategy can be put to use in modern times. In fact, his work is a fairly comprehensive layout of the creative possibilities of the format.

Building blocks

Some basic options for block construction were laid out fairly early in the silent era. The most famous instance was Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), which sampled four historical periods, each harboring its own distinct story. He then crosscut the four epochs, building to four “simultaneous” climaxes at the end of the film. Griffith managed to secure an unprecedented level of suspense by alternating portions of his blocks.

Griffith also wanted to prove a conceptual point, that intolerance reappeared at different times in different guises. He understood one of the major attractions of block construction: It asks us to compare and contrast.

Griffith also wanted to prove a conceptual point, that intolerance reappeared at different times in different guises. He understood one of the major attractions of block construction: It asks us to compare and contrast.

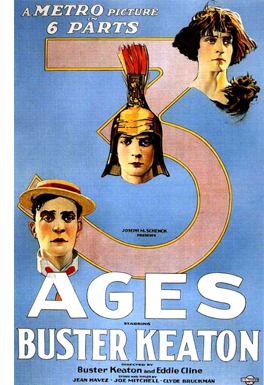

Directors who wanted to achieve the same comparison among different historical periods took the more obvious option and laid each separate story out, one after the other. We see the result in Dreyer’s Leaves from Satan’s Book (1920), Lang’s Der müde Tod (Destiny, 1921), and The Three Ages (1923), Buster Keaton’s parody of Intolerance. So this construction by integral blocks of time, laid end to end, was useful for comparing several self-contained stories.

Can you get the same sort of effect when sections of the same story are separated out in blocks? Yes, you can. The classic example would be parallel flashbacks. In Citizen Kane, an ongoing present, the reporter Thompson’s investigation, brackets long flashbacks that serve as parallel architectural parts—trips to the past, showing Kane as seen by others. We’re coaxed to compare Kane’s actions at different points in his life, as well as the various sides of him seen by his associates.

Here, as sometimes happens, the blocks are marked off not only by time period but by varying viewpoints. The alternation between the present and long stretches of the past, focused around one character and then another, characterizes many 1940s flashback films, such as The Killers (1947) and A Letter to Three Wives (1949).

Tarantino made alternating block construction the basic principle behind Reservoir Dogs (1992), which shuttles between the aftermath of a botched robbery and the planning that led up to it. One model he has acknowledged is Kubrick’s The Killing (1955), which itself transposed into cinema the overlapping point-of-view blocks that were present in Lionel White’s source novel Clean Break.

Elsewhere on the blog I’ve talked about how flashbacks can be nested inside one another, like Russian dolls. Examples from the 1940s include Passage to Marseille (1944) and The Locket (1946), and these lengthy sections surely count as blocks. Here the blocks serve less to compare dramatic situations than to fill in backstory. The blocks are lumps of exposition. In addition, blocks also can usefully delay events, creating suspense and padding the plot to its proper length. (Form often follows format.)

Tarantino embedded flashbacks within flashbacks in Kill Bill Vol. 1 (2003) for just these purposes. Let’s assume that the early sequence (Chapter One) showing the Bride attacking and killing Vernita, her second victim, is a benchmark for the narrative present. That ends with her reading her list of targets. Chapter Two, which follows, initiates a flashback going back several years. In the course of that, the Bride escapes from the hospital and sets out to kill O-Ren, who’s her first victim. And in the course of that long flashback, framed by the Bride lying in the Pussy Mobile, we get a nested one, dubbed “Chapter Three: The Origin of O-Ren.” That eight-minute anime fills in the life story of the queen of the Tokyo underworld before we return to the Bride’s quest for her.

The anime sequence is closed off by a return to the Bride recovering in the Pussy Mobile.

The flashback-within-a-flashback supplies exposition, creates a parallel to what we’ve seen at the film’s start (Vernita’s little daughter discovering the Bride’s murder of her mother), and sharpens our curiosity about the Bride’s trip to Japan. We stay in that Japan-related flashback for the rest of Vol. 1. The plot won’t take us back to the present, after the Bride’s killing of Vernita, until the black-and-white beginning of Vol. 2.

A trickier Chinese-boxes structure appears in Reservoir Dogs. The present-time situation is the gathering of the surviving hoods in the warehouse. There are flashbacks to the planning stages of the holdup, each attached to one man’s viewpoint and tagged with his alias.

In the flashback attributed to Mr. Orange, the police mole, we start with him identifying himself to the tortured cop in the warehouse. We move to the past, when Mr. Orange meets a contact in a diner and explains that the gang took him in. That leads to a nested flashback showing him at his audition.

To gain the gang’s trust, Mr. Orange tells a heavily rehearsed fake anecdote about evading the cops during a drug swap. And even that gets an embedding: the false anecdote is presented visually, as a scene in a men’s toilet.

Then we come out of the nested flashbacks in proper order: back to the meeting with the gang, then to the diner, and several scenes later, back to the present situation in the warehouse.

A lying flashback is embedded in a flashback that’s itself embedded within a flashback. The whole shebang becomes a complex block labeled “Mr. Orange.”

Most flashback films use the trips to the past to revisit characters known to us in the present. But some films use the flashback option to tell independent stories. Forever and a Day (1943) is a biography of a house, supplying a history of the house from its origins to its sufferings during the Nazi bombing of London. An even clearer example is Tales of Manhattan (1943). It traces how a coat of tails is passed down the social pecking order, from an elegant actor to a sharecropping community. No characters tie the episodes together, only the coat and some thematic motifs. Again, the blocks encourage us to contrast how different social classes use the tailcoat.

I don’t find Tarantino picking up this circulating-object idea, but it has been reused in Twenty Bucks (1993), American Gun (2006), and other films. Somewhat in the same spirit, though, is Tarantino’s Death Proof, the second feature in Grindhouse (2007). The first half of the original theatrical release concerns four young women who are targeted by Stuntman Mike, a free-range master of vehicular homicide. All the women are killed, but in the second half Mike meets his match in a quartet of car-crazy film staffers, one of whom is a stuntwoman while another is an expert driver. Mike is like the coat of tails in Tales of Manhattan: the only link between the film’s episodes.

Flashbacks can, of course, be much briefer, and when they are they don’t usually have the heft of blocks. But when a scene is replayed as a flashback, both the replay and the original scene can stand out. The flashback replay of the murder of Monty in Mildred Pierce (1945) gains a certain solidity, since it reveals things that were suppressed (and fudged) in the first go-round. (Go here for the entry and the analytical video discussing these scenes.) Another example is the conflicting testimony that includes a lying flashback in Crossfire (1947).

Pushing beyond his predecessors, Tarantino tries a more elaborate replay in Jackie Brown (1997). He presents the shopping-mall money exchange three times, from different characters’ attached viewpoints. The side-by-side replays make the whole money drop stand out as a block, as does the chapter title (“Money Exchange: For Real This Time”) and the length (over twenty minutes). A practice session for the exchange forms a parallel block, with its own introductory title (“Money Exchange: Trial Run”).

Episodic memories

Meet Me in St. Louis (1944).

If flashbacks, played once or many times, provide the most common sorts of blocks, big or small, there are other possibilities. You can, for instance, build your plot out of chronological but independent blocks within the same locale and time frame. Three Strangers (1946) is a straightforward example.

A woman invites two men into her apartment and suggests they share the price of a sweepstakes ticket. They will then reunite on the day the ticket falls due to see if they’ve won. After the men agree, the plot follows all three separately, with long blocks devoted to each. Their stories don’t intersect. There is a little bit of crosscutting among them, but the characters don’t reunite until the climax.

The advantage of this diverging-reconverging construction is that you can tell several stories, each with its own dramatic arc, within a larger frame that brings them all to a decisive conclusion. If you pull it off, it can deepen characterization (we spend more time with the protagonists) and perhaps mark you as a virtuoso. A flashy example is Mystery Train (1989), which provides the moment of the story lines’ convergence as a sound rather than a face-to-face encounter.

The risk of this format is that some separate stories may seem less interesting than the others. An ordinary film moves along quickly enough that we can wait out tiresome characters or situations, but in this construction we’re stuck for a while. This cost-benefit analysis may be one reason that most Hollywood plots try to integrate their story lines fairly tightly. That way you can keep the audience aware that each scene has consequences for everything that follows.

Tarantino uses the parallel block device in Inglourious Basterds (2009). Here two main story strands—Shosanna’s efforts to elude Colonel Landa and the mission of Aldo Raine’s combat team—develop independently in lengthy scenes. There’s some alternation, but the plot lines don’t converge until the movie theatre conflagration. Interestingly, both Three Strangers and Inglourious Basterds fill out their dimensions by including minor subplots (the adventure of Archie Hicox developing its own interest in Basterds).

The simplest version of block construction lets one distinct story episode follow another. The most common case is the Hollywood musical, which contains numbers, either as stage performances or as sung-and-danced scenes. Each number tends to have an internal coherence and sharp boundaries that make it a detachable unit. (So detachable that it can stand on its own in documentaries like That’s Entertainment! of 1974 and its sequels.)

One musical that includes larger-scale segments—quite big blocks,, actually–is Meet Me in St. Louis (1944). The plot consumes about a year in the life of a family, and it opens with a candy-box title card specifying “Summer 1903.” It’s followed by two more seasonal chapters, identifying autumn and winter of the year, before we get “Spring”—a title with no date, suggesting a kind of eternal renewal that will solve the characters’ problems. Within each of these blocks, events typical of each season, including Halloween and Christmas, reinforce the sense of these as varied sections.

This sort of explicit chaptering in the 1930s-1940s is usually reserved for films framed by opening pages of a book, as in Salome, Where She Danced (1945).

Often, as in Salome, the book frame is dropped from the rest of the movie, although it might reappear to provide closure.

New forms of self-conscious chaptering became prominent in later years, as with the quotations announcing sections in Hannah and Her Sisters (1985). Most of Tarantino’s films use chapter titles to some extent, with the Kill Bill movies providing the most elaborate examples. Those films are presented as two “volumes” containing ten distinct “chapters.” Some are bulked out by flashbacks, some aren’t, but all these chapters become prominent through sheer length. Chapter Nine, which settles the fates of both Budd and Elle Driver, runs almost half an hour, and the final chapter lasts over forty minutes.

Moreover, the chapters, as in Pulp Fiction, aren’t arranged in 1-2-3 order, so we’re invited not only to compare parts but figure out their chronology. The very first chapter teases us with this problem.

The circled 2 is explained when we understand that Vernita is the second target on the Bride’s list.

Still other forms of big-chunk construction came into prominence in the 1940s. Think for instance of what were called “episodic” films, movies that inserted separate stories, often thematically connected, into a general framing structure. For example, the team that gave us Tales of Manhattan also produced Flesh and Fantasy (1943). The situation is of two men discussing superstition in a library. One takes down a book of stories and we see, enacted, three tales of the fantastic. At the end we return to the library.

This cinematic anthology was sometimes called an omnibus film, and it proved very popular around the world; examples are Dead of Night (UK, 1945) and the many Italian and French collections (e.g., The Seven Deadly Sins, 1952; Spirits of the Dead, 1968). It persisted for decades in the US (New York Stories, 1989; Night on Earth, 1992) and internationally (Paris, je t’aime, 2006). Tarantino’s contribution to the genre was Four Rooms (1995). The framing situation is that of a hotel, and three other directors contributed episodes showing what happens to various guests.

Walt Disney exploited block construction in all these ways during the 1940s. He filled out a live-action film with embedded stories (Song of the South, 1946) and interspersed cartoons with travelogue footage (Saludos Amigos, 1942). The all-animated Three Caballeros (1944; above) assembled several South American tales by means of a frame story showing Donald Duck getting gifts from below the border and dancing with his amigos. (This is a brilliant movie, as I suggest in this ancient but ageless post.)

By contrast, Make Mine Music (1946) and Melody Time (1948) give their animated musical numbers only minimal framing.

Most famous of the Disney anthologies, of course, is Fantasia (1941). Here a program of classical pieces is illustrated in cartoon sequences. The frame is provided by Leopold Stokowski at the podium and Deems Taylor, a famous music popularizer, supplying radio-style commentary in the breaks. Strange though it sounds, Tarantino (along with Robert Rodriguez) does something similar when he gives us two exploitation features, Planet Terror and Death Proof, surrounded by trailers and ads. Just as Disney posits a mock trip to the concert hall, Tarantino reimagines a night at a drive-in or an inner-city movie house.

What about Django Unchained (2012)? I think Tarantino has done something clever here. At what seems to be the climax, Dr. Schultz is killed and Django, after a fierce gunfight, is recaptured and sold to slave traders. The drama seems to be finished. But then the movie starts over, and a twenty-five-minute stretch of new action shows Django escaping the traders and returning to Candyland to wreak his revenge. Tarantino has tacked on a second, lengthy ending; block structure yields a calculated anticlimax.

Modern, middlebrow, mysterious

I guess what I’m always trying to do is use the structures that I see in novels and apply them to cinema.

Quentin Tarantino, 1993

Where did the 1940s impulse toward block construction come from? In classical Hollywood cinema, I see two primary literary sources: modernism and its offshoots in “mild modernism” (what Dwight Macdonald called “midcult”); and mystery fiction.

Fictional tales had long been broken into segments, and chapter divisions are of course very old. Assembling tales out of blocks likewise has antecedents as far back as ancient Egypt, Homer, and the Bible. Epistolary and found-manuscript fiction gravitated naturally to block arrangement. Dickens gave Little Dorrit (1855-1857) a balanced two-part layout, and he built Bleak House (1852-1853) on alternating segments in two narrative voices.

By the end of the nineteenth century, writers reflected on such problems of carpentry. Here is Henry James on carefully dividing The Wings of the Dove into discrete sections. (The italics are his.)

By the end of the nineteenth century, writers reflected on such problems of carpentry. Here is Henry James on carefully dividing The Wings of the Dove into discrete sections. (The italics are his.)

There was the ‘fun’ . . . [of treating the actions as] sufficiently solid blocks of wrought material, squared to the sharp edge, as to have weight and mass and carrying power; to make for construction, that is, to conduce to effect and to provide for beauty.

Likewise, The Awkward Age (1899) was conceived as a situation to be illuminated by different characters, or “lamps,” each participating in a single social occasion. Consequently the contents as a series of chapters (or “books”) with character titles (not unlike what Tarantino did in Reservoir Dogs): “Lady Julia,” “Little Aggie,” “Mr. Longdon,” and so on.

This sort of explicit geometry was sometimes taken up by modernist writers. Faulkner breaks The Sound and the Fury (1929) into large parts determined by place, time, and character narrators. John Dos Passos intercuts chunks of different sorts of texts (news stories, “camera-eye” views) to create the trilogy USA (1930-1036). Other modernists avoided tagging sections but made sure to give each one a blocklike singularity, as Joyce famously does with the chapters of Ulysses. Each one is keyed to a section of Homer’s Odyssey, a time of day, a symbol, and so on, and treated in a different literary technique.

Middlebrow writers, who tried to make modernism more user-friendly, seized on block construction. A prime example is Thornton Wilder’s Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927), which traces three parallel stories of people who died on the bridge when it collapsed. Less famous is Rex Stout’s fascinating How Like a God (1929), which alternates two sorts of blocks: one in italics, past tense, third-person narration, and labeled with letters of the alphabet; a second in roman type, present tense, second person (“You…”), and given a numerical order. The labels and fonts help us figure out the chronology of the story (and grasp the thoughts of the main character). Kenneth Fearing’s mildly modernist novel The Hospital (1938) borrowed from Dos Passos in shifting viewpoints among many characters, even objects, and his Clark Gifford’s Body (1942) anticipates Pulp Fiction in drastically shuffling discrete blocks out of story order.

At a more popular level, mystery fiction developed its own strategies for block construction. As a genre, mystery and detective stories are dedicated to formal play with narrative options. (Hence their interest for us narratologists.) Mysteries are frankly artificial, even gamelike, and so seek out ways to trick us.

The love of artifice often yields embedded stories, as in A Study in Scarlet (1887), and plays with point of view (famously, Christie’s Murder of Roger Ackroyd, 1926). While Dickens and James were testing block construction in the “serious” novel, Wilkie Collins was developing the “casebook” format: a collection of documents—letters, testimony, discovered manuscripts—that served as a series of blocks. Dracula (1897) also helped popularize the format. It was revived in Dorothy L. Sayers and Robert Eustace’s The Documents in the Case (1930) and Perceval Wilde’s Design for Murder (1941). And just as Stout had made typography and chapter headings formal devices, so did mystery writers use them to build suspense and their readers (e.g., Anita Boutell, Death Has a Past, 1939).

We tend to take such trickery as typical of the sleuth-and-puzzle detective tradition, but not of the hard-boiled detective tales and suspense thrillers we associate with the 1930s and 1940s. Yet writers in those traditions sometimes shift a story forward and backward in big blocks, as with Don Tracy’s Criss Cross (1934, source of the 1949 film). Vera Caspary’s Laura (1943) exploited the casebook format, which was partly transposed into the film version. Kenneth Fearing, trying his hand at mystery fiction, shifted first-person narration among several characters (including a dead one) in Dagger of the Mind (1941) and The Big Clock (1946). Bill S. Ballinger’s Portrait in Smoke (1950) paralleled a first-person account of an investigation with third-person chapters that trace what happened in the past.

We tend to take such trickery as typical of the sleuth-and-puzzle detective tradition, but not of the hard-boiled detective tales and suspense thrillers we associate with the 1930s and 1940s. Yet writers in those traditions sometimes shift a story forward and backward in big blocks, as with Don Tracy’s Criss Cross (1934, source of the 1949 film). Vera Caspary’s Laura (1943) exploited the casebook format, which was partly transposed into the film version. Kenneth Fearing, trying his hand at mystery fiction, shifted first-person narration among several characters (including a dead one) in Dagger of the Mind (1941) and The Big Clock (1946). Bill S. Ballinger’s Portrait in Smoke (1950) paralleled a first-person account of an investigation with third-person chapters that trace what happened in the past.

Trends in high, middlebrow, and “low” literature like crime stories had a large impact on 1940s cinema. Just as important, this formal play with narrative conventions, including block construction, continued for decades, right up to the present. Most pertinent to Tarantino is the trend toward rigorous construction we find in crime fiction from the 1960s onward.

My own favorite example is Richard Stark (aka Donald Westlake), who conceives nearly all his novels in a rigid four-part format. Tarantino seems to prefer Elmore Leonard and Charles Willeford. He isn’t given as much credit for his bibliophilia as his cinephilia, but it’s evident that he has thought a fair amount about how to bring literary techniques into cinema.

Novels go back and forth all the time. You read a story about a guy who’s doing something or in some situation and, all of a sudden, chapter five comes and it takes Henry, one of the guys, and it shows you seven years ago, where he was seven years ago and how he came to be and then like, boom, the next chapter, boom, you’re back in the flow of the action.

For example, in Rum Punch, the source novel for Jackie Brown, Leonard’s chapter-breaks usually shift our attachment from one character to another, and the new chapter may insert backstory at the start. Leaving Jackie Brown’s deal with the Feds hanging, Chapter 14 starts with Melanie sunbathing and thinking about her past. A chunk of exposition, like a film flashback, explains how she became “the tan blond California girl.” Tarantino was unusually sensitive to fiction writers’ switches in time and viewpoint, and he clearly admired the opportunities opened up by solid chapter-length blocks.

I’m not suggesting that Tarantino spends his weekends perusing Henry James or Thornton Wilder. It’s just that techniques similar to theirs have pervaded popular literature. Indeed, they were already at play in one popular genre that has always used literary artifice to shape our experience. To this day, as in King’s 11/22/63, mysteries and thrillers use block construction to promote suspense, play with alternative possibilities, make us reevaluate story situations, and engage us in a game of self-conscious form.

Sometimes current developments put the past in a new perspective. The emergence of “minimal music” (Glass, Reich, La Monte Young) suddenly showed Satie’s ideas about repetition to be more fertile than most of us had thought. Similarly, Tarantino’s work forced me to think about contemporary storytelling strategies, but it also asked me to consider more distant sources of those trends.

Studying film history is valuable for its own sake; it’s just damn interesting. Needing further justification, sometimes historians go on to say, especially to students: We study history to better understand the present. That’s surely true, but so is this: We study the present to better understand history.

Henry James’ discussion of block construction is in “Preface to The Wings of the Dove” in The Art of the Novel: Critical Prefaces (New York: Scribners, 1934), 296. Tarantino’s comments about novels and films come from Graham Fuller, “Answers First, Questions Later,” in Quentin Tarantino Interviews, ed. Gerald Peary (University Press of Mississippi, 1998), 53; Jeff Dawson, Quentin Tarantino: The Cinema of Cool (Applause, 1995), 69.

A useful discussion of how chapter divisions relate to plot is Philip Stevick, “The Theory of Fictional Chapters,” in The Theory of the Novel, ed. Stevick (The Free Press, 1967), 171-184. You can sample it here.

Neo-noir encouraged many filmmakers to explore block construction. Three quick examples: Soderbergh in Out of Sight (1998; from a Leonard book), Christopher Nolan in Following (1998), and Shane Black in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005, which split up into chapters corresponding to one popular screenplay formula). Nolan proved keenly interested in this compositional approach; see our ebook, Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages. More recently, Wes Anderson’s films deploy some tricky versions of block construction.

Block construction is also apparent in comic books, and Tarantino is clearly an aficionado of those traditions too. That influence should be taken into account for a fuller analysis of his narrative techniques. Also, too: The influence of Godard, especially in the “tardy” title insertions coming after the segment has started (e.g., one way to take “The Gold Watch”).

The expanded, stand-alone feature version of Death Proof displays block construction in filling out the “missing reel” portion of the first story and creating a new block, a ten-minute scene of the second “girl posse” at a convenience store. The scene starts with Stuntman Mike before shifting to the young women. It makes Mike even more a connecting link between the film’s two episodes, while Mike’s stalking and spying fulfills Tarantino’s claim that Death Proof is a slasher movie.

Embedded stories or flashbacks exemplify what researchers call “ring construction.” Bill Benzon has explored this in many critical analyses, as here with the 1954 Godzilla/Gojira.

For more on Inglourious Basterds, see our entry here and as revised in Minding Movies. We analyze the money-drop sequence in Jackie Brown in Chapter 7 of Film Art: An Introduction. Kristin discusses the titles and segmentation of Hannah and Her Sisters in Chapter 11 of Storytelling in the New Hollywood.

Thanks to participants in the 2014 conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image for their comments on some of the ideas presented here. Thanks also to Matthew Bernstein, biographer of Walter Wanger, for in-depth discussion of Salome, Where She Danced.

Grindhouse (2007).