Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS: A usable past

Hellzapopppin’ (1941).

DB here:

By now everybody is used to allusionism in our movies—moments that cite, more or less explicitly, other films. But we tend to forget that movies have been referencing other movies for a long while. One classic form is parody, as when Keaton’s The Three Ages (1923) makes fun of Intolerance (1916). Another example occurs in Me and My Gal (1932). Spencer Tracy tells Joan Bennett that he just saw a movie called “Strange Innertube,” and then Raoul Walsh gives us a comic version of the inner monologues used in Strange Interlude (1932).

Some allusions are in-jokes that sail by most viewers. Almost everybody notices when Walter Burns (Cary Grant) in His Girl Friday mentions that a character played by Ralph Bellamy looks like “that fella in the movies—you know, Ralph Bellamy.” Probably fewer people catch the later line, Walter’s threat to the authorities: “The last man who said that to me was Archie Leach just a week before he cut his throat.” Grant’s real name, of course, was Archibald Leach.

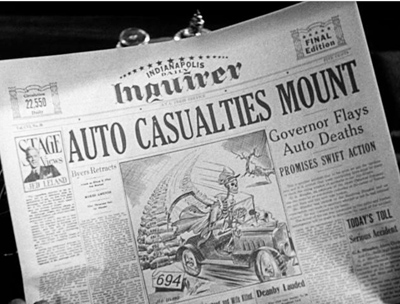

Week-End at the Waldorf (1945) is a sort of updating of Grand Hotel, so when one character remarks that a plot twist “is straight out of the picture Grand Hotel,” we probably catch the self-reference. But the other character piles on the allusions by replying: “That’s right. I’m the baron, you’re the ballerina, and we’re off to see the wizard.” Did people notice MGM congratulating itself twice? And you wonder how many viewers catch the spoiler in Hellzapoppin’ (1941), released only four months after Citizen Kane. Chic Johnson spots a Rosebud sled hanging outside an igloo and remarks, “I thought they burnt that.”

At the beginning of the 1940s, two novice directors seemed to be bringing fresh air to Hollywood cinema. Preston Sturges and Orson Welles were identified with innovative approaches to genre and storytelling. So we might expect them to inject something new into this practice of alluding to other movies. I think they did.

Consider a particular strategy that Sturges and Welles toyed with. Today, we enjoy it when a director treats characters in non-sequel films as sharing a fictional world. Tarantino imagines shifting his characters or brand names (e.g., Red Apple cigarettes) from movie to movie.

When I sell my movies, I retain the rights to characters so I can follow them. I can follow Pumpkin and Honey Bunny or anybody and it’s not Pulp Fiction II.

Jackie Brown (1997) features Michael Keaton as FBI agent Ray Nicolet, who also appears, played by Keaton, in Soderbergh’s Out of Sight (1998). The tactic fitted these directors’ adaptations of novels by Elmore Leonard, who tends to carry over characters from book to book.

It’s a bit surprising to see this impulse in Sturges and Welles too. The governor and the political boss in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) are McGinty and the Boss in The Great McGinty (1940), and they’re played (uncredited) by the same actors. A newspaper glimpsed in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) contains a column, “Stage Views,” by drama critic Jed Leland, a major character in Citizen Kane (1941).

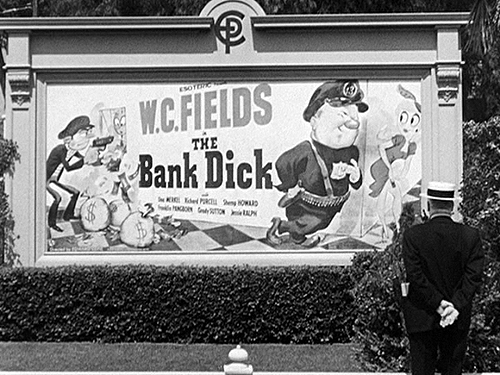

Today fans are used to spotting things that most viewers might not get, but in the early 1940s, it was rarer. I’ve proposed earlier that sometimes Hollywood’s creative community is addressing not the broad audience but its own members, perhaps letting dedicated outsiders “overhear” the conversation. One example would be the nearly-hidden jokes that can be wedged into the background or on the edges of the action. In an entry about a year ago, I considered how sequences around the small-town movie theatre in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek carry barely-noticeable jabs at current films, mostly those by Sturges’ home studio Paramount. And Luke Holmaas has pointed out to me that Hail the Conquering Hero contains a billboard advertising Morgan’s Creek—a sort of joking product-placement. Today, I want to suggest that Welles moved onto the same terrain but followed even more circuitous paths.

The past, not recaptured

Make pictures to make us forget, not remember.

Comment card from first preview of The Magnificent Ambersons, 1942.

The Magnificent Ambersons is, everybody knows, a film about the past. Its story action begins around 1885 and concludes just before World War I. Most of the plot concentrates on the decline of the Amberson family, due partly to financial mismanagement and the willful pride of Isabel Amberson’s son, George Minafer. Parallel to that decline is the development of the town into a city and the rise of the automobile company founded by Eugene Morgan, a failed suitor for Isabel’s hand. A major turning point comes when, after Wilbur Minafer’s death, Isabel is left a widow. She’d like to marry Eugene, but she declines because George is opposed. At the same time, George tries to win Eugene’s daughter Lucy. After the death of Isabel and her father Major Amberson, the family is destitute and George must find a way to support his aunt Fanny. Struck by a car, George is hospitalized, and only then does he reconcile with Eugene and Lucy.

After weak previews, the film was drastically recut, and some new scenes were shot. The original version has not yet been found, so we’re left with a ruined masterpiece. Still, there’s enough there to let us appreciate Welles’s effort to make sense of a crucial period of American history. Old money was giving way to modern, technology-driven fortunes; Eugene’s auto company is the Dell Computers of its day. The film also evokes changes in urban life, with shifting property values and rising pollution shown as consequences of progress. It’s the most downbeat of the “nostalgia” cycle of the 1940s, which includes Strawberry Blonde (1941), Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), and Centennial Summer (1946).

Many other films have sought to present the past, recreating the settings and costumes and props of an era. But Ambersons is about pastness. It conveys a melancholy recognition that things are always changing, that we struggle to make sense of events only after it’s too late to affect them. It’s a film centered on missed opportunities and what might have been. Eugene might have married Isabel when they were young, but his drunken serenade turns her against him. If George weren’t such a prig, he might have reconciled himself to Isabel’s remarriage; only at the end, kneeling in prayer, does he seem to realize how his stubbornness cheated many people of happiness. The original ending would have shown Eugene visiting Fanny in a boarding house, with her long and unspoken love for him counterpointing his suggestion that he’s been true to Isabel.

Ambersons carries its sense of an unrecoverable past into the very texture of its telling. At first, the aura of things gone by is given by Welles’ voice-over narration. In affectionate comedy he introduces us to habits and routines of an era of streetcars and changing men’s fashions. After Eugene’s botched serenade, the townsfolk add their voices to the chorus with comments on the scandal. More backstory is given when George is shown growing from a spoiled boy to an arrogant young man. Our narrator recalls “the last of the great Amberson balls.” Eugene arrives, a widower, bringing his daughter Lucy, and George begins to court her that night.

Now the narrator’s past-tense explanation withdraws for some time. Instead, characters take up the burden of narrating the past. “Eighteen years have passed,” says Isabel’s brother Jack at the ball. “Or have they?” Before Eugene dances with Isabel, he remarks that the past is dead. Unfortunately, it won’t stay buried. The old romance between Isabel and Eugene will be rekindled, and bad business decisions and George’s spendthrift ways catch up with the family.

Welles’s plot construction relies on ellipsis. The scenes skip over major story events—Wilbur’s death, the decline of the family fortune, Gene’s second courtship of Isabel, and Isabel’s death. So much occurs offscreen that we are left to play catch-up. We must listen to characters report on what has just happened, or reflect on the more distant past. The film is built on recollection and reaction. We don’t see Fanny at Isabel’s deathbed; she simply flies out of the room to embrace her nephew: “She loved you, George.” We don’t see George and Isabel on their European trip; we learn of it from the doleful Uncle Jack, who thinks that Isabel is falling sick. This refracted narration allows Jack to voice his concern—he’s probably the one Amberson whose judgments we trust—and Gene to display helpless, rigid sorrow at the news.

One of Ambersons’ most famous scenes, the long take of George and Fanny in the kitchen, is characteristic. Under her questioning, he explains that Gene and Isabel were starting to reunite at his college graduation. A peppy nostalgia movie would have shown us that cheerful moment on the campus, but Welles channels the information through George’s insensitive report and Fanny’s uneasy questions—and the scene climaxes with her breaking down in tears. As ever, melancholy wins out. As a result of George’s telling, Fanny will plant the suspicion that gossip about Isabel has been destroying the family’s good name.

Similarly, another film’s finale would show the reconciliation of the young lovers, George and Lucy, in the hospital. Instead Welles’ original script presents that moment through Eugene’s somber report of it to Fanny in her boarding house. (In the version we have, we get the report in the hospital corridor.)

Sometimes, the gaps in time and action are abetted by the studio’s reediting. In the present version, we learn about Aunt Fanny’s failed investments later than in the original version. But even then the information would have been presented after the fact. On the whole, the sense of the sadly unalterable past is built into Welles’ screenplay. As each scene unfolds, we get news about what has happened in the gap since the last scene, or what has happened years before. At the railroad station, Uncle Jack, about to depart, recalls a woman he left here long ago. “Don’t know where she lives now–or if she is living.” Here the pastness he evokes is familiar to us from earlier in the film: “She probably imagines I’m still dancing in the ballroom of the Amberson mansion.” At the limit, Major Amberson’s garbled fireside reverie takes us back to the origins of life: “The earth came out of the sun, and we came out of the earth . . . so–whatever we are must have been in the earth.” Now the past is primeval.

Retro as remembrance

Welles enhances the aura of pastness through specific film techniques. Critics have rightly been alert to creative choices that carry over from Citizen Kane: looming sets, drastic deep-focus cinematography, low angles, chiaroscuro, and long takes, often employing splendid camera movements. But the film displays some unique choices that are, historically, anachronistic.

The most noticeable old-time technique concludes the idyll in the snow. Jack, Fanny, Lucy, and George are riding in Eugene’s horseless carriage. This, one of the few scenes that doesn’t replay the past in its conversation, is given special treatment as a moment out of time. The iris out that concludes the scene is something of a visual equivalent to the old song the riders sing, “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo.”

Similar is the vignetting that softens the edges of the opening sequences, starting with the first shot showing the streetcar stopping for the lady of the house.

Welles’ visual techniques aren’t faithful to the period when the story action takes place. Assuming that the snow idyll occurs around 1904, the iris wouldn’t have appeared in films of that time. And the earlier period of the streetcar shot and changing men’s fashions probably predates the invention of cinema. But by 1942, these techniques were associated with silent film generally and give a cinematic tinge of “oldness” to the action.

I say “by 1942” because recent years had made intellectuals especially conscious of film history. Several books, notably the 1938 translation of Maurice Bardèche and Robert Brasillach’s Histoire du cinéma (translated as The History of the Motion Picture) and Lewis Jacobs’ sweeping The Rise of the American Film (1939) had concentrated on the stylistic innovations of Porter, Griffith, and other pioneers. With some theatres reviving silent classics like Caligari and The Birth of a Nation, cinephiles in urban centers had some opportunities to see silent movies. Most notably, the Museum of Modern Art Film Library was founded in 1935 and under the curatorship of Iris Barry, began building a permanent archive and screening retrospectives.

MoMA also assembled many films into traveling 16mm programs that could be rented by schools, museums, libraries, and other institutions. Silent films also circulated in 8mm and 16mm prints from private companies like Kodascope and Castle Films. Throughout the late 1930s and 1940s, silent comedies were the most popular; Chaplin reissued The Gold Rush in a sound version in 1942. Welles’s interest in silent slapstick is shown in the recently discovered pastiche, Too Much Johnson (1938), which evidently owes a good deal to Entr’acte (1924), a MoMA-canonized classic.

Ambersons offers other, less obvious allusions to old cinema. One cluster of them comes during George and Lucy’s stroll along the sidewalk. George, somewhat petulantly, is insisting that his trip abroad with his mother may last a long time. “It’s goodbye, Lucy.” Angling for a declaration of devotion from her, he gets brittle, agreeable indifference. When he has stalked off, we learn that she is actually quite shaken by the prospect of separation. Watching the dramatic interplay in this long traveling shot, we are probably not likely to pay attention to the posters the couple pass outside the Bijou theatre.

The advertisements announce movies that could have played the Bijou in 1912. The ones in the rear of the lobby are impossible to make out, and there’s one outside I can’t be sure of. (See the codicil.) Raking the frames on DVD and on a good 35mm print, I’ve been able to discern The Bugler of Battery B (1912), Her Husband’s Wife (aka, How She Became Her Husband’s Wife, 1912), Ten Days with a Fleet of U.S. Battleships (1912; in the foyer), and The Mis-Sent Letter (1912). There were several Jesse James films circulating in 1911-1912, but one two-reeler named for the bandit (at the bottom of the second frame here) seems a likely candidate.

These casual background details betray extraordinary fussiness on the part of Welles and his colleagues. Few viewers would pay attention to all the posters, and very few viewers would realize that they’re all from the same year. It’s one thing to include authentic automobiles from the era, as car fanciers would be sure to spot mistakes. But 1912 two-reelers? It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the filmmakers put the posters in to satisfy themselves. (If you’re skeptical, I’d ask: If you’d thought of it, wouldn’t you do it?)

There’s more. The most prominent hoarding advertises a Western, The Ghost at Circle X Camp (1912), from Gaston Méliès. Surely the name also evokes Gaston’s brother Georges, by then an established pioneer of film history and a figure doubtless known to Welles. Is this a sideswiping tribute from one magician-cineaste to another?

There’s also a deliberate anachronism. Tim Holt, who plays George, was the son of action star Jack Holt. A lobby card over the box office announces “Jack Holt in Explosion.”

I can find no trace that such a film existed. Moreover, films of that era seldom identified the main actors in advertising, and in any case Holt was not a featured player in 1912. In order to create an in-joke/homage, Welles seems to have prepared a poster for a fictitious film—as Sturges did with Chaos over Taos and Maggie of the Marines in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek.

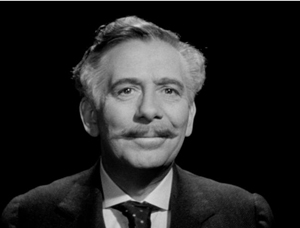

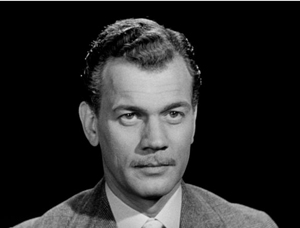

Perhaps the most sneaky allusion comes at the very end. After the florid voice-over credits for technical contributions, Welles intones: “Here’s the cast.” Medium-shots of the actors dissolve into one another as the voice-over identifies them. The images recall photographic portraits from the nineteenth century. They also seem to be a variant of those 1930s opening credits that catch the players in shots extracted from the movie to come. Still, there’s something peculiar about these.

Some of the actors look straightforwardly out at us, as we’d expect.

But others turn their heads slightly or shift their gaze, toward or away from us.

Sometimes the shift is tiny, as with the Joseph Cotten cameo. But the tactic is made into a joke when Tim Holt, staying in character, snaps his glance furtively to the camera.

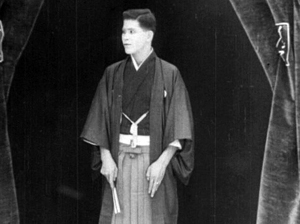

Why these fillips? Here’s my conjecture. Some 1910s films, from both America and Europe, introduced their casts with shots of the actors standing as if on a theatre stage. The actors then looked to left, then right, pretending to take in all sides of a live audience. Here’s an example from Reginald Barker’s The Wrath of the Gods (1914), featuring actor Thomas Kurihara.

None of the 1910s examples I know was framed as closely as Welles’s shots are. But I surmise that Welles offered a modernized variant of a minor silent-film convention. If this is right, it has to be an allusion more far-fetched than even the ones Sturges supplied.

Maybe I’ve gone too far. Once filmmakers start playing these games, overreach is a constant temptation. In any case, I think there’s enough evidence that Welles, like Sturges, was invoking early film history as a way of reinforcing the overall pastness-strategy of his film.

I’d go further and speculate that Welles’s obsessively pinpointed allusions may have stirred a competitive spirit in Sturges. Now we can see the Miracle of Morgan’s Creek tracking shot past the movie house posters as a variant, two years later, of the angle Welles chose for his long take.

And perhaps the audacious inclusion of footage from The Freshman (1925) at the start of The Sin of Harold Diddlebock (1947) was sparked by Welles’ virtuosically faked newsreel in Citizen Kane. As the two boy wonders from the East took advantage of the biggest train set a kid could play with, they may have egged each other on.

For more on the practice of allusionism and world-building see The Way Hollywood Tells It. Thanks to Ben Brewster for information on Jack Holt’s career. My quotation of the Ambersons preview card comes from Simon Callow’s Orson Welles vol. 2: Hello Americans (Viking, 2006), 87.

The Holt and Méliès posters are mentioned in the cutting continuity in Robert L. Carringer’s The Magnificent Ambersons: A Reconstruction (University of California Press, 1993), 214. Alas, the other posters aren’t specified.

The poster that I haven’t identified, and that drives me nuts, sits underneath The Bugler of Battery B. Here’s a blowup from 35mm.

The poster that I haven’t identified, and that drives me nuts, sits underneath The Bugler of Battery B. Here’s a blowup from 35mm.

The poster’s illustration, which we can glimpse more fully in a later phase of the shot, shows a man thrashing an American Indian while a woman stretches out her arms in the cabin in the background. At first I thought the first words are The Car, but I can find no film from the period that begins with that phrase. (It would fit more closely with Ambersons thematically than most of the other titles, but in fact “car” wasn’t then a common term for automobile.) Then I thought it was The Coin Box Girl, but again no such film seems to have existed, and that title is hardly in keeping with the illustration. Any ideas?

Yes, I know. Welles would have had a good big belly laugh at these efforts.

P.S. 10 June: I’ve been pursuing some readers’ leads about the still-mysterious poster. In the meantime, Joseph McBride has has corresponded with me with more ideas and information about Ambersons. Joe is the author of many books, including What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?: A Portrait of an Independent Career, Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless, and Into the Nightmare: My Search for the Killers of President John F. Kennedy and Officer J. D. Tippit, a meticulous study of those two murders. He is one of the world’s top Welles scholars, so naturally I’m happy to pass along his thoughts.

AMBERSONS is my favorite film, as you probably know, even in its partly ruined state. I think all your analysis is acute, and I like your focus on the self-conscious awareness of pastness that Welles conveys and dissects in the film. The film is redolent of Welles’s youth and even more so of the period before he was born (the period for which I find most of us are most nostalgic). Nostalgia was considered a neurosis in the pre-modern era, a sign of inability to adjust to reality rather than the warm-and-fuzzy state it’s thought of being today. There’s a deep melancholy throughout the film, even if Welles, good magician that he is, distracts us with misdirection via comedy in the beginning while simultaneously laying the seeds of destruction and foreshadowing George’s “comeuppance,” etc.

Last month I was at the Welles conference in Woodstock, Illinois, which has preserved much of its nineteenth-century flavor, including the Opera House where Welles put on TRILBY (but most of the Todd School for Boys he attended is gone). That town and its main square, with bandstand and Civil War monument, seems very Ambersonian as well. I have always seen AMBERSONS as Welles’s most deeply personal film, and his claim that Eugene Morgan is partly based on his father (and that Booth Tarkington knew his father) is noteworthy, as is George Amberson Minafer’s evil-twin resemblance to the young George Orson Welles.

I would only add to your insights that there was much more about the loss of the Amberson fortune in the full version of the film (you allude to that a bit), even though, as you intriguingly note, Welles employs an elliptical style throughout. Welles’s use of ellipsis is Lubitschean (he considered Lubitsch a “giant”), although used for somewhat different reasons, Welles doing so mostly to condense the story in witty ways (and, as you observed to me, focus on characters’ emotional reactions to offscreen events, in the manner of Henry James) and Lubitsch to evade censorship while providing subtle rather than blunt treatments of sex. And some of Lubitsch’s German films, as you know, start with specially posed head shots of him and his main actors, somewhat similar to what Welles does at the end (though he teasingly keeps himself out of frame, partly to stress the voice aspect and also to keep the identification of himself with George stronger). Tim Holt gazing accusingly at us in the end credits is startling — maybe it’s not only to keep him in character but also to say, “I’m you.”

Welles is terrible (archy, corny, and putting on a phony kid voice) as George in the radio version, which, however, is much like the film in some ways. During the night devoted to radio in the 1978-79 “Working with Welles” seminar I co-hosted for the AFI at the DGA Theater, Welles’s longtime associate Richard Wilson and I ran the first ten minutes of the radio show as the soundtrack for the film imagery, and it worked amazingly well. Welles’s use of ellipsis in the film recalls his radio work, in which he and his writers would condense a large novel into one hour, etc. The vignettes at the opening of AMBERSONS are very much drawn from radio. He sold the project to RKO’s George Schaefer by playing the radio show, though the fact that Schaefer fell asleep before the end might have given them pause.

Welles said he included the “Jack Holt in EXPLOSION” gag did to please Jack when he visited the set. Jack was an action star for Capra before AMBERSONS and turns up in THEY WERE EXPENDABLE, in the scene in which John Ford pays homage to his high school teacher Lucien P. Libby by naming a boat after him. Another of those in-jokes that permeate even classic Hollywood, as you say. Mr. Libby influenced Ford’s portraits of Lincoln and other folksy politicians as humorous storytellers.

Welles’s early films show a keen awareness of film history and culture, more than he would let on later he knew at that young age. He described THE HEARTS OF AGE to me as a spoof of THE BLOOD OF A POET and LA CHIEN ANDALOU. TOO MUCH JOHNSON is full of film influences and allusions (I think I sent you my essay on the film from Bright Lights. And KANE has its share of in-jokes, such as Gregg Toland interviewing Kane on board a ship and Kane responding with his first words in the film after “Rosebud” — “Don’t believe everything you hear on the radio.”

Thanks to Joe for corresponding.

Never Give a Sucker an Even Break (1941).

Nothing, if not critical

The Woman in the Window (1944).

O, gentle lady, do not put me to’t,/ For I am nothing, if not critical.

Iago, Othello

DB here:

Movie aficionados seem endlessly interested in film criticism—not just in what a writer says about a film, but in the very idea of criticism. I’ve suggested in a recent entry some of the historical reasons for this: the rise of the celebrity reviewer in the 1960s, the surge in interest in foreign and alternative cinemas, the emergence of filmic experiments, from Persona to Memento, that seemed to demand discussion.

With the internet, you can’t turn around without bumping into a film review. Aggregate sites like Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic get tens of millions of hits a month. Of course many people are just checking on the range of opinions of a specific release, but I get a sense that many readers are more or less addicted to critical buzz as such. Connoisseurs of sentiment and snark, they still follow favorite reviewers just as we did in the 1960s, and they enjoy reading a critic they don’t agree with because she or he is an enticing writer.

In one corner of my workroom a steadily growing pile of books is no less a tribute to the flourishing of film criticism. Yes, books. I’m a committed Netizen (I’d better be, after three e-books, several web essays and videos, and over 610 blog entries). And for certain purposes, such as word search, I prefer digital versions of texts. But nothing beats a book for reading anywhere you happen to be, thumbing back to check a point, marking up margins with invective, and throwing across a room when you’ve decided the author is a dunce.

Here, though, are some books that won’t become missiles.

Revaluation

One consequence of the 1960s cult of the movie critic was a new genre of book—the anthology of a writer’s reviews, think pieces, and long-form essays, perhaps spiced by an interview or two. Call it a predecessor of a website if you must, but such books were tempting packages to cinephiles who wanted their fix in big gulps, not weekly doses. Then we eagerly read through Agee on Film, Dwight Macdonald on Movies, Kael’s I Lost It at the Movies, and many other collections. Some of these are now classics, most are forgotten, but the format still has life in it. Roger Ebert, exceptional in all respects, kept it going for years and crowned it with his Great Movies series. The format passed to academic presses like Wesleyan with Kent Jones’ Physical Evidence (2007) and Chicago with Dave Kehr’s When Movies Mattered (2011).

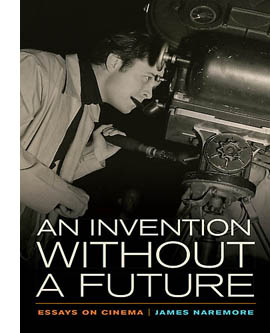

Like me, James Naremore is a creature of the 1960s, but with his typical discretion he has waited forty years to bring together a collection. Jim’s 1973 Filmguide to Psycho introduced me to his elegant thinking about movies. Since then he has written about a great many subjects, always with wit, steady vision, and deep and unostentatious learning. Now we have An Invention without a Future: Essays on Cinema (University of California Press).

Every essay here is a polished gift from a master of the literary essay. The book’s first section considers classic topics like adaptation, authorship, and acting. It includes a sharp discussion of the rhetorical dimension of both filmic creation and critical commentary. In the second section we see Naremore the close reader, turning to the classic Hollywood cinema he has done so much to illuminate. He considers Hawks, Hitchcock, Welles, Huston, Minnelli, and Kubrick—the subjects of earlier writing he’s done, but now refocused through new lenses. One recurring question is: Does cinema, either as a physical medium or a public spectacle or a humanistic art have a future? Although the book’s compass swings constantly to the 1940s through the 1960s, Jim is fully up to date, writing with sensitivity on Shirin, Uncle Boonmee, and Mysteries of Lisbon.

Every essay here is a polished gift from a master of the literary essay. The book’s first section considers classic topics like adaptation, authorship, and acting. It includes a sharp discussion of the rhetorical dimension of both filmic creation and critical commentary. In the second section we see Naremore the close reader, turning to the classic Hollywood cinema he has done so much to illuminate. He considers Hawks, Hitchcock, Welles, Huston, Minnelli, and Kubrick—the subjects of earlier writing he’s done, but now refocused through new lenses. One recurring question is: Does cinema, either as a physical medium or a public spectacle or a humanistic art have a future? Although the book’s compass swings constantly to the 1940s through the 1960s, Jim is fully up to date, writing with sensitivity on Shirin, Uncle Boonmee, and Mysteries of Lisbon.

The latter pieces were among Jim’s efforts at real-time film reviewing at Film Quarterly. Perhaps the sharpest edge of the book comes in the section housing them, called “In Defense of Criticism.” Jim, I think, considers criticism as, say, Lionel Trilling or Edmund Wilson considered it. Endowed with a tolerant, generous mind, the critic uses all the resources of culture—philosophical and moral ideas, social forces, artistic traditions—to illuminate the unique identity of the artwork.

More deeply, the critic expects the encounter with the artwork to challenge and change us. This to me is one difference between the reviewer and the critic. The reviewer expects the film to live up to his or her solidly entrenched point of view. The critic is open to being shaken, taught, and even transformed by the film. The reviewer projects confidence, the critic displays curiosity.

This ambitious conception of criticism is at risk today from two forces. There is the sheer blather of pop journalism and the Internet, which have pushed film culture from criticism to comments to chat to chatter. At the other end, some professors are allied against film as an art.

Today the humanities are in danger of losing their soul. Academic film studies has tended to focus on formal systems, industrial history, fandom, and identity politics—essential topics without which good criticism can’t be written, but topics that don’t engage directly with questions of art and artists.

Admitting that a certain detachment is valuable for research purposes, Naremore thinks that academics have become somewhat too clinical. Part of his book’s purpose is to draw their attention back to the intellectuals who flourished outside the academy, and for whom quality was worth arguing about.

I nevertheless think that evaluative criticism needs to be encouraged more, and I miss the days before the full-scale development of film studies, when film was made exciting and relevant by virtue of critical writing and debates over value.

So the last section consists of thoughtful essays on James Agee, Manny Farber, Andrew Sarris, and Jonathan Rosenbaum—those who “had the greatest influence on the development of my taste.”

For my $.02, I’d just add that appraisals of quality shape a lot of academic writing, even in the Cult Studs vein. Showing that a film is racist or classist is surely an exercise in evaluation, employing moral or political criteria. Showing that fans of Twilight aren’t dumb no-hopers often springs from the researcher’s own esteem for the franchise. (Remember one of The Blog’s mottos: We are all nerds now.)

In effect, I think, Jim is pointing out that in a lot of film studies evaluation isn’t framed in specifically artistic terms. On that I’d certainly agree. Jim opens a new conversation by asking academics to look beyond their specializations and learn how the best arts journalists argue about quality. Seriously thought-through yet accessible to all, An Invention without a Future is a bracing, quietly subversive book.

Auteurs: From the ridiculous to the sublime

Jim would find signs of hope in two books dedicated to major directors.

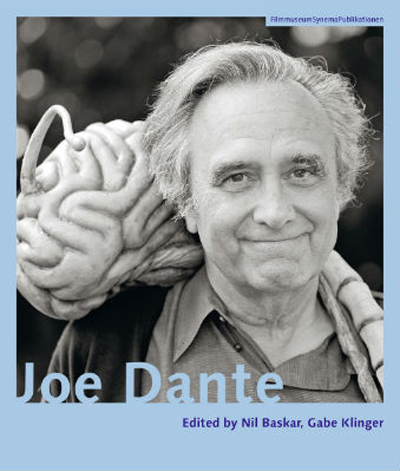

Nil Baskar and Gabe Klinger’s Joe Dante, a collection from the enterprising SYNEMA series at the Austrian Film Museum. Dante is just the sort of auteur that cinephiles prize. Working on the fringes of the system in despised genres, he’s a Movie Brat who loves B cinema, noir, and crazy comedy. This thick, square book contains virtually everything you’d ever want to know about the man who could be seen as Spielberg’s demented, funnier alter ego. Dante’s kiddie adventure stories and teen terror pix have celebrated and parodied Americans’ feverish love of war, big business, junk food, and lunatic media.

From The Movie Orgy through Looney Tunes: Back in Action to The Hole (still not released in 3D in the US, as far as I know), Dante has been a paradigmatic case of the termite artist praised by Manny Farber. In this collection John Sayles recalls that for The Howling he and Dante agreed they would center on characters who knew horror-movie conventions and wouldn’t make the typical fatal mistakes. Bill Krohn, J. Hoberman, Christoph Huber, and Michael Almereyda are among the admirers assembled here, and their spirit of amiable, film-geek homage is infectious. There’s also a long interview with Klinger, a detailed chronology, and a filmography zestfully annotated by Howard Prouty.

From The Movie Orgy through Looney Tunes: Back in Action to The Hole (still not released in 3D in the US, as far as I know), Dante has been a paradigmatic case of the termite artist praised by Manny Farber. In this collection John Sayles recalls that for The Howling he and Dante agreed they would center on characters who knew horror-movie conventions and wouldn’t make the typical fatal mistakes. Bill Krohn, J. Hoberman, Christoph Huber, and Michael Almereyda are among the admirers assembled here, and their spirit of amiable, film-geek homage is infectious. There’s also a long interview with Klinger, a detailed chronology, and a filmography zestfully annotated by Howard Prouty.

Dante’s opposite number is Béla Tarr, whose films run the gamut from glum to morose, but they’re no less exhilarating. They find their ideal explication in András Bálint Kovács’ The Cinema of Béla Tarr: The Circle Closes. Kovács scrutinizes all the films, some little-known outside Hungary, and produces careful analyses that balance thematic interpretation with precise examinations of style. As a friend of Tarr’s, András is in a unique position to take us into this filmmaker’s grimy, splendid world.

Tarr, Kovács suggests, asks his audience to accept the illusions shaping the narrative world. Yet his structure and technique in the end yield a clearer view of the underlying forces than the characters can achieve—often, forces driven by conspiracy or betrayal. Accordingly, Tarr’s narratives tend to be cyclical, even when the story situation is unchanging, and his camera movements often trace a circular path. Many readers will particularly welcome Andras’ exciting account of Sátántangó, Tarr’s most demanding film. Based on a novel with an intricately circular structure, the film finds its own means to suggest a story swallowing its own tail. Most film books nowadays have pretty good frame illustrations, but these are well-sized to illustrate some of Tarr’s fine points of staging. In all, this book is likely the definitive study of Tarr’s art.

Museum pieces

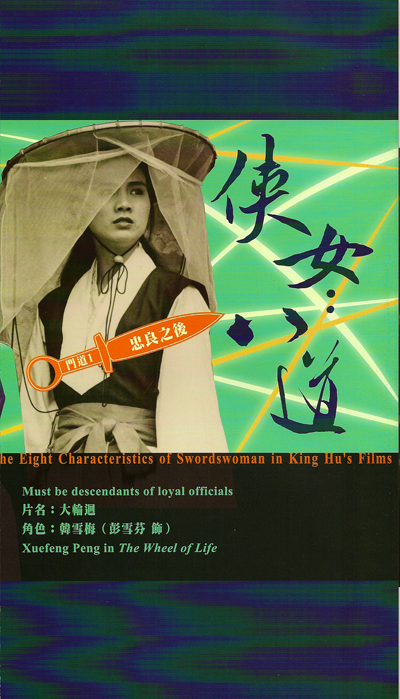

There’s another way to make the case for an auteur’s value: produce a dazzling book that pays tribute with gorgeous illustrations and informed critical commentary. This has been done by Taipei’s Museum of Contemporary Art in its catalogue King Hu: The Renaissance Man.

The 2012 exhibition it preserves in its pages went beyond the usual regimen of talks and panel discussions. There were children’s events and in-person painting of film billboards. In one display, you could watch Tsui Hark’s calligraphy form a tribute to his master (“The integrity of swordsmanship remains as the spirited rain….”). An installation tableau by Tim Yip presents a modern woman watching King Hu TV appearances while texting, her vacant mind suspended between two spaces.

The 2012 exhibition it preserves in its pages went beyond the usual regimen of talks and panel discussions. There were children’s events and in-person painting of film billboards. In one display, you could watch Tsui Hark’s calligraphy form a tribute to his master (“The integrity of swordsmanship remains as the spirited rain….”). An installation tableau by Tim Yip presents a modern woman watching King Hu TV appearances while texting, her vacant mind suspended between two spaces.

Open the catalogue and you’re greeted by a large gatefold that sums up King Hu’s career. Thereafter, articles like Edmond Wong’s study of King Hu’s archetypes (derived from legend and theatre) supply the academic ballast, while images of the gallery displays fill up page after page. There are photo essays devoted to each of the films, as well as more gatefolds, illustrating themes such as “The Eight Characteristics of Inns in King Hu’s Films.” Just the hundred pages of King Hu documents—stills, portraits and self-portraits, along with caricatures of Bill Clinton and Princess Di—would be worth our attention. In all, this is the sort of museum show every cinephile dreams of visiting.

Art historian Steven Jacobs, author of The Wrong House, has collaborated with Lisa Colpaert to produce a dream of another sort. Their book invites you into an imaginary exhibition.

Visualize a museum containing all the paintings you find in films of the 1940s and 1950s. Now assume that some diligent scholar has sniffed out the provenance of all of them and provided stylistic and thematic commentary. And now assume that the research is presented as a guide to this virtual museum, using all the paraphernalia of art-historical commentary.

Confused? Here’s the opening of one entry:

[III.9] Portrait of Lady Caroline de Winter

(Unknown Artist, late 18th Century)

This full-length portrait represents Lady Caroline de Winter (1760-1808). The carefully rendered white dress, the column and curtains, and the vista of the landscape are unmistakably reminiscent of the portraits by Thomas Gainsborough, for instance his often-reproduced The Honourable Mrs. Graham (1775-1777). The landscape with trees probably stands for Manderley, the de Winter family estate on the Cornwall coast. For more than a century, the portrait was hanging in a long corridor in Manderley’s east wing, which was decorated with ancestral de Winter portraits. In the 1930s, the portrait played an important part in the life of one of Lady Caroline’s descendants, Maxim de Winter (Laurence Olivier). Maxim’s first wife Rebecca died in mysterious circumstances and once had a copy made of the white dress on the occasion of a masquerade ball at Manderley. . . .

This straight-faced experiment in creative criticism is called The Dark Galleries: A Museum Guide to Painted Portraits in Film Noir, Gothic Melodramas, and Ghost Stories of the 1940s and 1950s. All the conventions are there: the scene-setting introduction, the iconographic interpretations (“crimes and clues,” “paintings concealing safes”), and an exhibition guide that takes you from room to room, from Dying Portraits to Ghosts to Modern Portraits and more. They track the ways in which paintings in movies have altered time, refashioned faces, and, if the painting is disturbingly “modern,” signified madness and criminality. As zealous researchers, Steven and Lisa have done what they could to trace the provenance of the actual artifacts too, and they’ve discovered a large number of commercial artists hired by the studios.

This straight-faced experiment in creative criticism is called The Dark Galleries: A Museum Guide to Painted Portraits in Film Noir, Gothic Melodramas, and Ghost Stories of the 1940s and 1950s. All the conventions are there: the scene-setting introduction, the iconographic interpretations (“crimes and clues,” “paintings concealing safes”), and an exhibition guide that takes you from room to room, from Dying Portraits to Ghosts to Modern Portraits and more. They track the ways in which paintings in movies have altered time, refashioned faces, and, if the painting is disturbingly “modern,” signified madness and criminality. As zealous researchers, Steven and Lisa have done what they could to trace the provenance of the actual artifacts too, and they’ve discovered a large number of commercial artists hired by the studios.

A few years back at our summer film school, Steven impressed me when he identified the famously puzzling cubist still life in Suspicion as Picasso’s Pitcher and Bowl of Fruit (1931). The ultimate result of his and Lisa’s efforts is at once charming and deeply serious, enlightening us about a major motif in Hollywood’s “dark cinema.” It’s an extraordinary accomplishment, and an ideal gift for the patriarch, matriarch, exotic woman, or mystery man in your life.

Thanks to Lin Wenchi for giving me the King Hu catalogue. I’m unable to find an online source for this book, but when I do I will note it here. In the meantime, the sponsoring museum produced several videos for the exhibition. YouTube supplies a playlist of them. Our entries on this great director are here. I discuss his work in more detail in the books Planet Hong Kong and Poetics of Cinema.

For more exercises in creative criticism, visit Hilde D’haeyere’s website on silent comedy.

For more thoughts on film criticism on this blog, go here and here and here. A series on major American film critics of the 1940s starts here.

I record Joe Dante’s visit to Madison here and wrote about Béla Tarr’s films in these entries.

F for Fake (1972).

Innovation by accident

DB here:

The old drama is being reenacted before our eyes, and as often happens, Harvey Weinstein plays the villain. The American release version of Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, which has cut and changed the original, is being decried as a travesty, the dilution of an artist’s original conception in the name of what somebody thinks will sell.

I take up The Grandmaster in another entry. For now, I just want to point out the archetype goes back long before Harvey came on the scene. A screenwriter or director comes up with a fresh approach to telling the story. But a producer rules it out as something the audience won’t buy, or even understand. Moral: In Hollywood, the creative force is stifled by a money person who insists on doing things as usual.

The 1940s in Hollywood was an era of narrative innovation. It gave us weird dream sequences and insane protagonists and subjective point of view and byzantine flashbacks and talking houses and complicated replays of action we thought we understood. While working on a book on this era, I’ve begun to wonder what the limits of innovation might be. What could make the boss tell the filmmaker that a particular narrative choice just went too far?

Fasten your seatbelts, it’s going to be a bumpy production

A Letter to Three Wives (1949).

One example I found was purely anecdotal, but nifty nonetheless. In preparing the screenplay for Out of the Past (1947; aka Build My Gallows High), screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring wanted to have the story told by a deaf-mute boy. Apart from the fact that the boy plays a minor role in the opening of the film as it was finished, the idea of someone who cannot hear or speak serving as narrator proved to be something of a stretch for the time. Mainwaring reports that the idea was rejected.

That’s the kind of thing I wanted to find. Yet my searches sometimes came up with cases where the producer’s notes actually resulted in improvements. Take A Letter to Three Wives (1949), justly praised as one of the best films of the 1940s.

John Klempner’s original novella (published in 1945) and novel (1946), both titled A Letter to Five Wives, obviously involved two more couples. After some other writers had drafted versions, Vera Caspary was assigned to prepare a treatment. Probably with the input of producer Sol Siegel, she eliminated one couple. Her adaptation already contains much of what is distinctive about the movie as we have it. Instead of the many distributed flashbacks in the originals, the treatment consolidated them into three lengthy ones. At Siegel’s suggestion, Caspary brought the three women together on the boat. To Fox studio chief Darryl F. Zanuck we apparently owe the idea that one woman, Deborah, would be the primary vehicle of our sympathy and would initiate and resolve the mystery of whose husband has defected. Above all, Caspary’s treatment includes the unforgettable voice-over of the never-seen Addie Ross.

When director Joseph L. Mankiewicz saw Caspary’s final adaptation, in effect “A Letter to Four Wives,” he declared he “looked upon the Promised Land” and quickly turned it into a screenplay. After reading Mankiewicz’s screenplay, Zanuck intervened again , demanding that another wife be lopped off. Mankieiwicz called this “an almost bloodless operation.”

It’s probably irrelevant that A Letter to Three Wives won that year’s Academy Awards for best screenplay and best direction. Even if it hadn’t been honored, after reading the original tales and Caspary’s adaptation, I have to conclude that the film is the best version of the lot. I suppose it partly goes to show the old rule that bad or so-so books can make very good movies. (Exibit A: The Birth of a Nation; Exhibit B: The Magnificent Ambersons; Exhibit C: The Godfather. Defense rests.) But clearly, the cuts and changes demanded by Siegel and Zanuck improved the property. The “creatives”–Klempner, Caspary, Mankiewicz–were by force majeure steered toward good results.

You can argue, though, that no written version of the film tried to be innovative, except perhaps for the device of Addie’s spectral presence. And Mankiewicz declared himself happy to make the adjustments. What about cases in which genuinely bold ideas were curtailed by the powers above? So I looked into two titles that, when released in the producers’ cuts, were denounced by their writer-directors.

Two years after Preston Sturges finished and cut his film about the discovery of ether anesthesia, Paramount producer B. G. “Buddy” DeSylva supervised and released a reedited version called The Great Moment (1944). Sturges noted of the film:

It is coming out in its present form over my dead body. The decision to cut this picture for comedy and leave out the bitter side was the beginning of my rupture with Paramount. . . The dignity, the mood, the important parts of the picture are in the ash can.

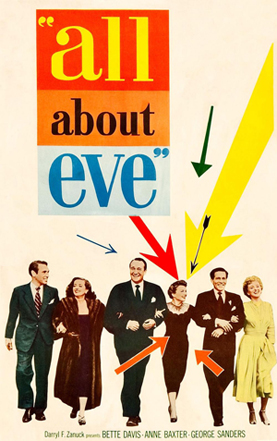

A second example is a more famous release, Twentieth Century-Fox’s All About Eve (1950). After the success of A Letter to Three Wives, Zanuck allowed Joseph L. Mankiewicz to film his three-hour screenplay as a “shooting draft.” When Zanuck saw the result, he insisted on cutting it to 138 minutes.

Throughout his life Mankiewicz was an angry man. His interviews and writings excoriate mothers, film festivals, doctors and nurses, Michelangelo Antonioni, television, the American male, theatre operators, Graham Greene, the AFI, PBS, Richard Nixon, Dennis Hopper, The Untouchables (film version), British craft unions, and other malefactors. High on the list was Darryl F. Zanuck. Long before the Cleopatra debacle, Mankiewicz was already carrying a grudge because Zanuck removed a replayed scene from All About Eve. He definitely didn’t consider that a bloodless operation.

Zanuck had final cut and he got bored with the same scene shot from different points of view.

Here, I thought, were sterling examples of creators bumping up against what was impermissible. Yet the more I looked, the more I found that the situation couldn’t be reduced to the daring director versus the philistine producer. I was forced to consider the possibility that the producers’ changes yielded not timid conformity but instead some unpredictable results–things that were themselves novel, in intriguing ways. The suits hadn’t intended to do something bold, yet in revising and patching up the films shot by two venturesome directors, they actually found themselves pulled in new directions.

Call it inadvertent innovation. Not surprisingly (this is the 1940s), it involved flashbacks.

Which great moment?

Kitty Foyle (1940).

By the early 1940s, movie flashbacks adhered to several conventions that we still recognize. Typically, we’re given a situation, the narrative Now, in which a character is recounting or simply remembering past events. We then move to those events, a shift often signaled by a track-in, a musical cue, a dissolve or other optical effect, and/or sounds from the next sequence mingling with the spoken transition. We may hear the voice-over remarks of the lead-in character at times during the action we see. Once the flashback action is complete, we return to the present, with the character who launched the flashback finishing the testimony or closing off the memory. And if the film includes several flashbacks, they are typically presented chronologically, so that the earliest events from the past are shown before later ones.

Kitty Foyle (1940) offers a clear example. In the present, Kitty recalls her romances. As they develop, we return to the present at key moments to gauge her reactions. For the sake of clarity, the romances themselves are shown to us in 1-2-3 order, tracing the events that lead up to the crisis that launched her memory journey.

Not all flashbacks respect chronology, though. Citizen Kane’s first flashback traces Kane’s career as the banker Thatcher knew it. His recollections show us Kane as a child, a young man, and then a much older man forced to sell his newspaper empire. The next flashback, as recounted by Kane’s business manager Bernstein, takes us back to show Kane as a young man assuming control of his first newspaper. Several years before Kane, Sturges had composed a script based on similarly shuffled chronology. The Power and the Glory (1933), directed by William K. Howard, presents an old man recalling episodes in the life of tycoon Thomas Garner, and those are presented out of 1-2-3 order. (I analyze that film here.)

Sturges was confronted by the problem of order in preparing Triumph over Pain. This project would tell the story of Dr. W. T. G. Morton, the popularizer of surgical anesthetic. Biographical films about scientists and inventors had become a successful cycle in the late 1930s, but Sturges wanted to stay fairly close to the facts. The problem was that Morton’s story couldn’t lead easily to a triumphant finale. Sturges noted dryly:

Dr. Morton’s life, as lived, was a very bad piece of dramatic construction. He had a few months of excitement ending in triumph and twenty years of disillusionment, boredom, and increasing bitterness. . . . To have a play you must have a climax and it is better not to have the climax right at the beginning.

Accordingly, Sturges had somehow to rearrange portions of Morton’s life.

Since [the writer] cannot change the chronology of events, he can only change the order of their presentation.

The title Sturges gave to his final version, Great without Glory, indicates its tone. A quasi-documentary prologue hails the modern benefits of anesthesia. We move to the late 1800s, when Morton’s friend Eben Frost finds a medal given to Morton now sitting in a pawnshop. He brings the medal to Morton’s widow Elizabeth, and as they sit in her parlor, the film’s first long flashback starts. It presents the public celebration of Morton’s triumph, as he and Eben are driven through the crowded streets.

The ensuing scenes trace the aftermath of his discovery—the fact that he could not patent it, his efforts to build a business on sale of ether bottles, a bout of illness, and then his receiving the medal while he is plowing on his farm.

Sturges’ version returns to the narrating frame, as Eben examines some more personal memoirs that Elizabeth has written. The second flashback initiates the play with chronology. It traces events leading up to the action we saw completed at the start of the first one. The plot takes us back to the couple’s courtship, the first years of Morton’s dentistry practice, and his arduous experiments with ether. He finds prosperity using it on his patients. Challenged to demonstrate his invention in a public surgical operation, he realizes that his demonstration will show his rivals his trade secret. He is about to leave the operating theatre when he sees the patient: a girl about to have her leg amputated. Unable to let her face agony, he turns back to reveal his discovery to his peers.

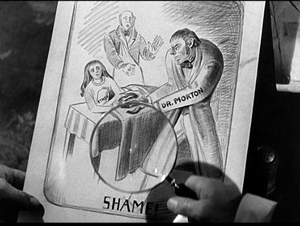

The plot’s true climax is Morton’s gesture of sacrifice. Sturges encourages us to see it as a contrast to the way the press and his profession vilified him. During the first flashback, a newspaper cartoon shows Morton preying on innocent patients, as typified by a girl on a gurney.

Sturges expected us, I think, to recall this image when Morton decides to help the girl. In his life, the cartoon came later, but showing it early in the film lets Morton’s gesture serve as a rebuke to those who are going to hound him.

After revealing Morton’s sacrifice, Great without Glory provides a bitter epilogue. The film ends with a return to the framing situation in Elizabeth’s parlor. Eben rises sadly, leaving Elizabeth alone.

Sturges could simply have built his film around Morton’s early life and his successful discovery, ending before the decades of poverty that followed. Instead, by focusing his biopic around our failure to appreciate and reward selfless research, he wanted to praise a man who achieved greatness but not the long-lived veneration accorded Edison or Pasteur. Yet showing Morton’s fall from grace after the crowd’s acclaim meant that the high point of a science biopic would be accomplished far too early in the plot. What we today call the “darkest moment”—Morton’s rejection by his public and his poverty—would come too soon. When Sturges showed his cut to his friend John Seitz, a great cinematographer, Seitz asked: “Why did you end the picture in the second act?”

According to Sturges, Buddy DeSylva said the same thing. He was already hostile to Sturges, and after some mixed preview results he set about reshaping the picture. The result is a good example, I think, of unintended innovation.

DeSylva did, as Sturges indicated, “leave out the bitter side” in certain respects. He lopped off the final scene showing the mourning of Eben and Elizabeth. The Great Moment doesn’t return to the narrating frame set up from the start of the picture. This is a little disconcerting structurally, but it wasn’t unknown at the period. Guest in the House (1944), Dillinger (1945), and other films “forget” the fact that they began with a character recalling the past.

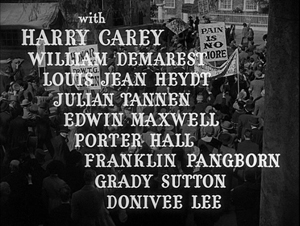

Nor did DeSylva start the plot with Sturges’ prologue and narrating frame. He offered something immediately upbeat: Morton and Eben descending to the cheering crowd and riding through the streets to acclaim. This action, surprisingly, takes place during the credit sequence.

By inserting the moment of Morton’s triumph at the very start of the movie, before we have even seen a flashback to it, or indeed even know who these people are, DeSylva seems to illustrate the film’s title. Our first impression is that Morton’s great moment is the public recognition of what the crowds’ placards announce is his conquest of pain.

Only after this “flashforward” does the release version settle down to something roughly like Sturges’ structure. Eben discovers the medal, brings it to Elizabeth, and elicits her recollections. Some of the scenes are rearranged from Sturges’ version; the placement of one, showing Morton sick in bed, seems calculated to lead in to his death (as it doesn’t in the Sturges cut). The newspaper cartoon is there, ready to form a parallel with the climax. As in the Sturges version, a return to the narrating frame shows Eben and Elizabeth in the present launching the second big flashback. With other alterations, we go through the couple’s romance and marriage, culminating in the discovery of ether and the prosperity of Morton’s practice.

DeSylva retains Sturges’ climax: the scene when Morton must choose whether or not to reveal his trade secret to his competitors in the public demonstration. Seeing the girl praying on the gurney, he decides to do it. The film ends with him striding into the operating theatre, about to share his discovery. It is here that DeSylva halts the film, without, as we’ve seen, returning to the frame featuring Eben and Elizabeth.

Both locally and more broadly, the effect is curious. Now Morton’s great moment is revealed, as Sturges wished, as the moment of his self-sacrifice, not the moment of his celebrity. But more strangely, without the final frame situation, the film ends just before the opening credits sequence. We could easily imagine the credits as an epilogue, with Morton’s entry to his colleagues dissolving to the parade in his honor before the final fade-out. Instead, the film halts and wraps back around itself like a Möbius strip: the last thing we see immediately precedes the first thing we saw.

I’m not trying to make this movie Memento or Primer, but there is something uncanny about the release cut’s looped structure. Sturges created a story that was depressing but tidy (prologue, carefully framed flashbacks, epilogue). DeSylva, unable to rewrite Morton’s history and apparently reluctant to junk the project, made the story more upbeat but also more untidy. Trapped by Sturges’ design, he re-carved it in a uniquely peculiar shape.

Sturges’ bold stroke was to switch the two chronological blocks of Morton’s life and to make us sense the injustice of Morton’s fleeting fame. DeSylva wanted to avoid the grim epilogue in the present and end on an upbeat note. But he did retain the split chronology, so that the contrast between obscurity and fame remains. He inadvertently innovated by making the opening credits preview a scene far ahead in the plot, and then letting the ending twist back to it. By playing the title over the parade, the release version shifts us across two moments, and meanings, of greatness: celebrity and self-sacrifice.

Did Buddy set out to be daring? I don’t think so. He faced constrained solutions whichever way he turned, just like us most of the time. More on this matter at the end.

As easy as C-A-C-B-C-B-C

As I mentioned, flashbacks usually sit comfortably in a frame, a well-established present situation that we depart from and return to. The shifts in and out of the past can be eased by various devices, one of which is a voice-over representing the character. The voice-over may be objective, as when a trial witness is testifying, or subjective, representing the “inner voice” of the person remembering what we have in the flashback.

Again, however, a film built out of flashbacks has many options. Coming to direction in the mid-1940s, Joseph L. Mankiewicz was in a position to try his own riffs on current experiments in storytelling.

So, for instance, in House of Strangers (1949), he frames a flashback without a voice-over. The camera coasts up a stairway to a window at night; dissolve to the window in daytime, and pull away to reveal the earlier scene. Our understanding of the time shift is aided by the comparison on the musical track: a phonograph record of a passage from the opera Martha fades out, and in the flashback, the Monetti family patriarch, now alive, is singing it.

Similarly, A Letter to Three Wives (1949) supplies the symmetrical structure in shifting from Deborah to her anxious memories and then back again.

But the voice-over varies from the usual. Instead of hearing her voice asking herself, “Is it Brad?” we hear the voice of Addie Joss, who also narrates the film. The suburban wives’ obsession with their rival, who may have run off with one husband, has allowed her to burrow into each woman’s consciousness. (In addition, her voice merges with the chugging of the ship to create distortions courtesy of Sonovox.)

House of Strangers is built around one long flashback; A Letter to Three Wives gives us three parallel ones. All About Eve yields yet another variant. Three characters at a banquet recall their experiences with Eve, the dazzling young actress to be given an award. There will be several flashbacks following Eve’s career chronologically and skipping from one remembering character to another. Given this plan, Mankiewicz’s long version planned for one moderate experiment and one fairly daring one.

The moderate experiment was to eventually eliminate the visual anchoring of the frames. He had planned to start with very clear bookends around the flashbacks and then gradually discard framing scenes. For instance, after Addison DeWitt’s voice-over introduces the other characters, including Margo and Karen sitting at his table, Karen’s voice-over intervenes. We leave the banquet to flash back to her meeting Eve.

In Mankiewicz’s “shooting draft” of the film, we then return to the banquet in the standard bookend fashion. Karen looks over at Margo much as Addison had looked at her. We hear Margo’s voice-over, and then her flashback is launched. Mankiewicz planned, in all, three of these base-touching intervals in the banquet. The later flashbacks are simply signaled by voice-overs only, interweaving the memories of Karen, Margo, and Addison as Eve rises in the theatre world. In short, Mankiewicz wanted to replace block flashbacks with “polyphonic” ones, but only after careful preparation.

The more daring experiment, and the one whose loss rankled for years, was the idea of replaying Eve’s famous “applause” monologue. We’re at Margo’s party, and several characters are perched informally on the staircase. Addison and Bill, Eve’s fiancé, have argued about the nature of the theatre. Then Eve launches on a brief but impassioned ode to the joys of acting. Applause amounts to “waves of love coming across the footlights and wrapping you up.” Mankiewicz wanted this to follow a scene between Karen and Eve in Margo’s bedroom. Introduced by Karen’s voice-over, this scene shows Eve pressing Karen to help her become Margo’s understudy. Following this, Eve’s monologue can be seen as a warm testimony to her dedication to the theatre—a confession that Karen watches dotingly from a higher step.

At this point, Margo enters from the kitchen and confronts Eve before insulting the other guests and flouncing off to bed.

Instead of showing this scene’s aftermath, Mankiewicz wanted to break chronology and skip back to the beginning of the party, with Margo’s voice-over now introducing things. After some scenes showing her efforts to get Eve out of her life, she was to stalk out of the kitchen and hear in the hallway the end of Eve’s monologue.

They [Margo and Lloyd] exit into the dining room. As they open the swinging door, the CAMERA REMAINS in the doorway. Margo and Lloyd walk toward the stairs. In the b.g., Eve is talking to the group.

How much she says is dependent on how long it takes Margo and Lloyd to reach her.

EVE (in the b.g.): Imagine,,, to know, every night, that different hundreds of people love you… They smile, their eyes shine—you’ve pleased them, they want you, you belong. Anything’s worth that.

Just as before, she becomes aware of Margo’s approach with Lloyd. She scrambles to her feet….

MARGO: Don’t get up. And please stop acting as if I were the queen mother.

And as Margo speaks—or before—we FADE OUT.

By following Margo’s efforts to cast Eve out, the effect of hearing part of the monologue is to confirm Margo’s suspicions that Eve’s demure obedience conceals her desire to compete on the stage.

What Mankiewicz wanted, it seems, was to use a replay for a new purpose. In Mildred Pierce and other 1940s films, the replaying of an action fills in missing material, usually with the purpose of dispelling a mystery or providing a surprise. Here the replay contrasts two characters’ reactions: Karen finds Eve’s speech touching, Margo finds it threatening. Most replays enhanced plot, whereas this emphasized characterization (which in turn advanced the plot).

Or might have. Zanuck, as we saw, cut it out. The incisions left some little scars, as you can see from the discontinuities in the final version. Eve, her trance broken, glances up and sets her expression into standard Alert-and-Deferential Eve mode, as if Margo were coming right at her. Then she gets to her feet. All this apparently happens well before Margo rounds the corner of the doorway.

So Zanuck eliminated Mankiewicz’s boldest step. But, in a reciprocal movement, he found Mankiewicz’s flashback anchorings over-cautious. Zanuck’s version simply cut out all the returns to the banquet except for the very last one.

One consequence is to give greater saliency to the final portion of the banquet ceremony, which has been halted, as if by magic, during Addison’s address to us. Other effects of Zanuck’s excisions waft through the whole film. The floating voice-overs that Mankiewicz had painstakingly prepared (according to the Rule of Three) now emerge at the very start. Voices slip in and out of scenes, more or less tied to what each speaker could have known at that point but never given the sharp boundaries of the standard blocked-and-framed flashbacks.

These floating voice-overs point ahead to the freedom our filmmakers have enjoyed since the 1990s. We no longer demand that explanatory voice-overs be anchored in any Now; they can braid together as ongoing commentaries on the action. From Hollywood to Wong Kar-wai, filmmakers take for granted that they can discard bookended narration in the way Zanuck did. Mankiewicz objected to Zanuck’s habit of cutting scenes “from peak to peak to peak.” But the boss, who always liked his movies fast-paced, explained: “I am way ahead of you and so will the audience be.”

The choice cascade

There’s a lot more to be said about these films and filmmakers, and I hope to develop some of those ideas in my book. For now, there are some interesting lessons.

First, in filmmaking, once you’ve made certain choices, others follow and some become forced on you. What historians of technology call “path dependence” comes into play. Just as computers use fundamentally the same QWERTY keyboard that came into being with early typewriters, initial choices about a project set limits to what you can do. A trajectory makes certain outcomes more likely than others, and it’s hard to reverse.

Once Paramount committed to releasing some version of Sturges’ Pain project, DeSylva had to work with the split chronology somehow. But Hollywood tradition demanded an uplifting ending, so one had to be salvaged, even if that meant snipping off the return to the frame story. Similarly, once Mankiewicz commits to presenting Eve’s ascent from the perspective of three outside observers, certain narrational processes didn’t need as much redundancy as he loaded in. Likewise, Mankiewicz’s prized replay didn’t create path dependency. It was a branch off the main line and could, as Zanuck saw, be lopped off.

Second, in a routinized film industry, we ought to expect that conflicting demands and changes of plan will yield not only well-wrought plots and narration, but also partial, fractured, even discordant narrative patterns. Snafus and compromises are part of the process.

Finally, film techniques seem innovative only in relation to the norms of a period. Most of the narrative strategies employed by Sturges, DeSylva, Mankiewicz, and Zanuck would have probably seemed startling in the 1930s. By the 1940s, such experiments seemed fresh but comfortable additions to a growing repertoire of storytelling techniques. The studios’ solutions were feasible because some flexibility had already emerged in handling frame stories and voice-over transitions.

The history of film forms springs from creative choices made by individuals within institutions. Those decisions have consequences, intended or not. Sometimes the producers don’t suffocate new things; sometimes they create them. If only by accident.

Don’t worry, though. I won’t be making such arguments about The Magnificent Ambersons.

Daniel Mainwaring mentions his plans for Out of the Past in Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s, ed. Patrick McGilligan (University of California Press, 1988), 199.

On A Letter to Three Wives, my comparison of Caspary’s adaptation with Mankiewicz’s shooting script was enabled by the Caspary collection at the Wisconsin State Historical Society. Thanks to Mary Huelsbeck and the staff of the SHS for helping me access Caspary’s papers. Mankiewicz’s remarks about the process and Zanuck’s request to delete one wife are quoted from Robert Coughlan, “15 Authors in Search of a Character Named Joseph L. Mankiewicz,” a 1951 Life magazine article available in Joseph Mankiewicz Interviews, ed. Brian Daugh (University Press, of Mississippi Press, 2003), 17. Caspary was inclined toward modular plotting, as is shown in detail in A. B. Emrys’ Wilkie Collins, Vera Caspary and the Evolution of the Casebook Novel (McFarland, 2011).

Brian Henderson provides painstaking comparisons among various versions of Sturges’ scripts and the final version of The Great Moment in Four More Screenplays by Preston Sturges (University of California Press, 1995), 241-360. My quotations from Sturges come from James Curtis, Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982), pp. 171-172. Another robust biography is Diane Jacobs, Christmas in July: The Life and Art of Preston Sturges (University of California Press, 1994). Essential as well is the autobiography Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges, ed. Sandy Sturges (Simon & Schuster, 1990).

Mankiewicz’s “shooting draft” of All About Eve has never, to my knowledge, been published. It is available on the Internet, God knows how, here. My extract is from p. 74. A screenplay closer to the finished film was published in 1951 by Random House. It is reprinted in More About All About Eve: A Colloquy by Gary Carey with Joseph L. Mankiewicz (Random House, 1972). Mankiewicz’s regrets over Zanuck’s deleting the replay are expressed in Andrew Sarris, “Mankiewicz of the Movies [1970],” in Dauth’s Mankiewicz Interviews, 31. The characterization of Zanuck’s “peak to peak to peak” cutting can be found in Sam Stagg, All About “All About Eve” (St. Martin’s, 2001), 171. Zanuck’s remarks about being ahead of his director’s screenplay are quoted in Mel Gussow, “The Lasting Allure of ‘All About Eve,'” New York Times (1 October 2000), AR13.

Two lively and careful critical studies are Kenneth L. Geist, Pictures Will Talk: The Life and Films of Joseph L. Mankiewicz (Scribners, 1978) and Bernard F. Dick, Joseph L. Mankiewicz (Twayne, 1983). Charyl Bray Lower and R. Barton Palmer’s Joseph L. Mankiewicz (McFarland, 2001) is an indispensable guide to the director’s work and writings about it. Both Sturges and Mankiewicz are discussed with polemical relish in Richard Corliss, Talking Pictures:Screenwriters in the American Cinema (Penguin, 1995).

I’m grateful to Laura Russo and particularly John C. Johnson of the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center of Boston University. Mr. Johnson kindly supplied valuable information about the version of the All About Eve screenplay held in the Bette Davis collection there.

Another case of the suits’ laying down demands to which a director responds creatively involves the final shot in Bill Forsyth’s wonderful Local Hero. Details here.

Finally, this entry is one in a series of spinoffs of my ongoing work on narrative in 1940s and early 1950s Hollywood. A gathering point for related blog entries is here, and a relevant web essay is here. As a coda to these 1940s films, it’s worth noting that in The Barefoot Contessa (1954) Mankiewicz did get to mount a replayed flashback scene, and in the 1960s he prepared a screenplay of Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet that would have presented several characters’ perspectives on the central action.

All About Eve.

The enemy next door

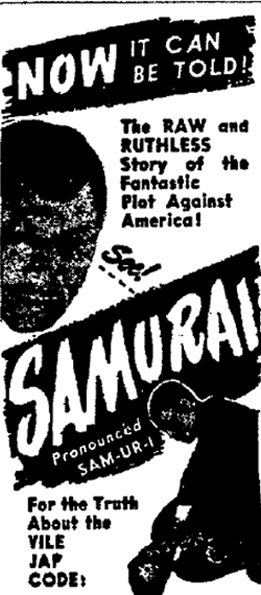

Left: Original caption: “Enforced farewell–These Japs wave farewell to relatives as they leave for Manzanar reception camp” (Los Angeles Times, 24 March 1942, p. B). Right: Advertisement for Samurai (Fitchburg [MA] Sentinel, 23 January 1946, p. 5).

DB here:

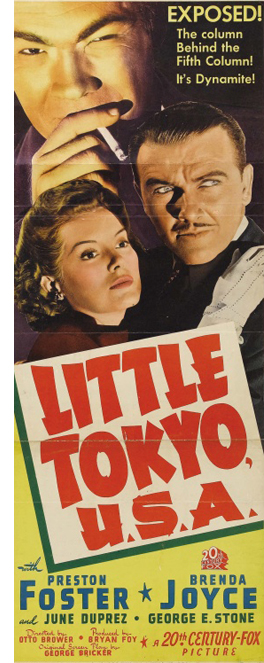

World War II never goes away, as the current attention given to Hollywood’s relation to Nazi Germany indicates. Thomas Doherty’s Hollywood and Hitler and Ben Urwand’s The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler trace how the American studios responded to the rise of Nazism and the launching of hostilities. While working on 1940s Hollywood, I ran across two films that deal with another member of the Axis. They remind us of some painful incidents in our history, and they show how inflamed patriotism can burst into racial panic and oppressive public policy.

Call it a mass migration

Soon after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, there arose a fear that saboteurs were at work in America. No solid evidence of this was demonstrated, but the most powerful decision-makers were not in a mood to be tentative. In February 1942, President Roosevelt signed an executive order that authorized the Secretary of War and military commanders to demarcate areas from which anyone could be excluded. The Pacific coast was declared such a zone.

In early 1942, the US Army rounded up 110,000 California residents of Japanese ancestry and sent them to what were called concentration camps. (At that point the term simply meant a camp in which enemy populations were “concentrated.”) The evacuees were dispersed to makeshift camps throughout California, as well as in Wyoming, Arizona, Oregon, and Washington state.

Some of the internees were first-generation immigrants, but about 90,000, were citizens. A 1942 government documentary film presents the “relocation” process as necessary for national security, and it shows the evacuees accepting, in a spirit of patriotic submission, the need for such measures. In the film the evacuees effortlessly re-create their communities in their new locations.

Bizarre as it sounds today, the film takes pride in showing that a democracy can create humane concentration camps. But a reading of Richard Lingeman’s Don’t You Know There’s a War On? points up some things the film doesn’t say. The film doesn’t mention that the people rounded up were forced to abandon their homes, businesses, and farms and were permitted to take only what they could carry. (Newspapers often described the relocation as “voluntary.”) The film doesn’t show that the relocation centers were jerry-built, some by the inmates themselves, and were often located in harsh climates. The camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, was subject to sandstorms, blizzards, and subzero temperatures. Nor does the documentary note that the camps were enclosed in barbed wire and watched over by armed guards in security towers. Nor does the documentary show that, because Japanese-American farms produced 40 percent of the California vegetable crop, rival growers pressed for the internment and then snapped up the displaced farmers’ lands at what Lingeman calls “eviction–sale prices.”

The Japanese weren’t unique in undergoing internment; other ethnic groups were subject to investigation, confinement, and relocation. But no other minority was subjected to such a comprehensive roundup. It’s estimated, for example, that about 11,000 German-Americans, innocent or suspected, were interned–a significant violation of their rights, but nothing on the scale of Japanese internment. White people of European extraction, German-Americans had become pillars of American society, and were very numerous. (They were and remain the largest U. S. minority self-identified by descent.) Japanese-Americans, a much tinier and more vulnerable minority, were more easily marked as potentially alien to American values.

Late in 1942, the government began resettling Japanese-American internees outside the camps, spreading them to several states. In December of 1944, partly as a result of a Supreme Court decision the government could not consign “concededly loyal” citizens to camps, authorities declared that the west coast was no longer a war zone. But fears of Japanese espionage didn’t subside, as we can see from a 1945 independent film called Samurai.

Pledged to the God of War

Samurai shows an adopted Japanese boy growing into a traitor and spy. In September 1923, Mr. and Mrs. Morrey rescue Kenkichi from the ruins of the Tokyo earthquake and bring him home to San Francisco. While attending school and assimilating into American society, Kenkichi secretly visits a Buddhist temple where the priest inculcates him in the martial tradition of Bushido, the way of the samurai. Studying to be a doctor, Kenkichi becomes a proficient painter. At the same time, he swears to live and die by the sword, repeating the priest’s pledge that “The God of War presents the key to eternal life!”

The unsuspecting Morreys send Kenkichi to Italy and Germany for his studies, and the priest exhorts him make contacts that will train him as a secret agent. Back in America he begins painting abstract landscapes that conceal military information in coded form–a strange version of that motif of paintings and portraits that winds through 1940s American cinema (The Two Mrs. Carrolls, Suspicion, The Ministry of Fear). When the painting is abstract and nonrepresentational, it usually suggests that the painter may be mad.

Telling his parents that he will be a curator of Asian art, Ken goes to Tokyo and there, at the Black Dragon Society, he decodes his paintings. The Dragon Society’s leader suspects that his visitor is an American spy, but the doubts are dispelled when Kenkichi alters photos from Shanghai to appear that the Japanese are aiding the Chinese. Ken further proves his loyalty by murdering a journalist. He is assigned to the unit of General Sujiyama as a full-fledged spy.