Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

Twice-told tales: MILDRED PIERCE

Mildred Pierce (1945).

DB here:

At the climax of Now You See Me, a barrage of brief shots skips back in time to show how our quartet of magicians pulled off the complicated illusion we’ve just seen. (A very, very complicated illusion, in fact. You and I should be so lucky.) Soon our Four Horsemen come to realize that a puppetmaster behind the scenes has been steering them, and this awareness comes in another flurry of flashbacks.

Today’s movies are constantly using fragmentary flashbacks to fill in elements left out of earlier scenes. I recently considered how Safe Haven and Side Effects use the convention, but lots of other films will furnish examples. Crucial to this technique is an illusion created by cinematic narration. The first time through a scene, we think we’re seeing everything. But the replay shows us bits and pieces that were left out, or that we didn’t notice, or that we’ve forgotten about.

Back in 1992 I wrote an essay about this technique. “Cognition and Comprehension: Viewing and Forgetting in Mildred Pierce” focuses on the murder of Monte Beragon in the 1945 film. A revised version of the essay appears in Poetics of Cinema and is now available on this website. The piece tries to show that a cognitive approach to comprehension and recollection can explain how a film shapes viewers’ responses—in this case, creating mystery while making viewers forget certain things they’ve seen.

Today I’m going to consider Mildred again, but by doing something I couldn’t do in print. The wonders of the Internetz let me use video extracts to show concretely how clever this replay is. I frame my case here differently than in the earlier piece, although there are ideas and examples common to both. Perhaps what I do here will tease you into reading the more technical essay.

And of course there are spoilers—most thoroughly in reference to Mildred, more mildly in reference to Side Effects and The Unfaithful (1947).

Hiding murder

At the start of Mildred Pierce we see Monte shot down in a beach house, but we don’t see who did it. At the climax of the film, we’ll see a flashback replay the murder, filling in elements that were suppressed in the earlier version. In these sequences, director Michael Curtiz and the film’s screenwriters make choices about at least three narrative conventions.

How do you present the original scene? How do you handle the flashback? How do you present the replay?

These choices confront every screenwriter or director who wants the Aha! effect of dramatically revealing what was really happening in an earlier sequence.

The filmmakers’ decisions will be shaped by the urge to make the audience’s pickup fast and effortless. The filmmakers know that we tend to want to cut to the core of a story situation, to grab its gist and move on, and we trust that the film’s unfolding will help us do that. But this very speed can work against us. By counting on our knowledge of conventions, filmmmakers can encourage us to jump to conclusions that will turn out to be inaccurate.

Start with the handling of the original scene. Your choices are basically these: We can see the action fully, or we can see it only partially, with some aspects suppressed. Consider the opening of The Letter (1940). Leslie Crosbie strides out of a cottage, blasting away at a man who tries to crawl away from her.

We see the crime fully, so the mystery involves circumstances. What led up to this murder? The rest of the film’s plot will concentrate on that.

Alternatively, some element of the initial scene can be omitted. This is what we get in the shooting of Miles Archer near the start of The Maltese Falcon (1941).

It’s familiar territory. The film’s narration conceals the identity of the killer by framing him or her out of the shot. The question of who killed Archer will propel part of the action to come.

The crucial action can be suppressed even more thoroughly. In The Accused (1947), a woman is followed into her home. We already know her as a wealthy wife waiting for her husband to come home, but we aren’t shown the identity of the shadowy male figure who grabs her and forces his way into the house.

And the camera stays obstinately outside while someone is shot in the house.

Only later will we find out who the victim is, and the entire film will slowly reveal what really happened inside, and what led up to it.

I’ll have some things to say about Mildred’s initial murder scene shortly, but now let’s consider the second key convention: the flashback device itself. What is a flashback? Most basically, it involves presenting earlier story events in the midst of later ones. It’s often motivated as a memory, as when a woman recalls her childhood. But there doesn’t have to be a memory motivation; the film’s narration can directly show us bits of action that occurred in the past (as in the “objective” flashbacks in Kubrick’s The Killing).

Mildred Pierce is built on three flashbacks. Two long ones explain the course of her life with her family, and a final one dramatizes Mildred’s explanation of what happened during Monte’s murder.

What, then is a replay, the third convention I’m considering? I don’t think critics and filmmakers have a very stringent sense of this device. (See the codicil for further comments.) I’d suggest that basically a replay is a flashback that revisits scenes we’ve already seen. When our heroine recalls her childhood in scenes we didn’t see before, we have a flashback. But if later in the film we see those childhood scenes again, I’d call it a replay. Centrally, a replay revisits scenes we’ve already witnessed, or at least glimpsed.

So not all flashbacks are replays. Are all replays flashbacks? Some would say yes, but I’m more cautious. I’m inclined to say that a mechanical recording of a scene shown earlier could count as a replay without being a flashback. In Rebecca the newly-married couple watches home movies of their honeymoon. This scene fulfills the function of a flashback, but the action we see remains in the present: the couple are screening the film. The footage doesn’t show scenes we’ve already seen, but if it had, I’d call the screening of the movies a replay, but not a flashback—since, again, the action framing it is visible in the present.

This sort of mechanical recording/ replay is very common in modern films, reflecting the ubiquity of surveillance cameras, cellphones, and the like. In an earlier blog entry I talked about a purely auditory replay in Sudden Fear that’s made possible by an audio recording device. It would be odd to call the home movies or the SoundScriber playback flashbacks.

So some replays are flashbacks, and some aren’t. When they’re flashbacks, replays are often used subjectively, as when a character remembers an earlier action. Recall all those dream sequences that present, often with distorted imagery or sound, action we’ve seen previously in the film. But a replay may also supply new information about actions we already witnessed and thought we understood. We thought we grasped an earlier scene because nothing signaled to us that pieces of information were missing.

This possibility goes to another creative option. Sometimes the film tells us that something has been omitted. In my Maltese Falcon and Unfaithful examples, the narration is openly suppressive: It announces that it’s not telling us certain things. This of course adds mystery to the plot.

Alternatively, the presentation of the initial scene might be covertly suppressive; it hides things and doesn’t tell us it’s hiding them. In Side Effects, we see the heroine commit murder and then go to bed. Later the murder scene is replayed, but with extra shots showing actions we didn’t see or surmise before. The idea of replaying to fill in previously suppressed information is quite old; you can see it at work in Griffith’s Romance of Happy Valley and Ford’s Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. In modern cinema, we sometimes revisit an earlier scene several times, with each pass yielding new information (e.g., Go). You might want to call these “multiple-draft replays.”

Gunplay and replay

We start with two establishing views of the beach house, with a car outside. Over the second, gunshots are heard. Shot by an unknown assassin, Monte staggers forward and falls back onto the carpet. A close shot shows him saying, “Mildred” as he dies.

The camera tracks to the bullet-riddled mirror and we hear the sound of a a door. A new shot lingers on Monte’s corpse. We then see the car drive off.

The next scene shows Mildred pacing nervously on the pier.

I think that this opening lays out two options, one for the trusting viewer and one for a more skeptical one. The trusting viewer assumes that Mildred killed Monte. He seems to glance at her as he speaks her name, and the shot of the car pulling away leads smoothly to the sequence showing Mildred on the pier.

Not so fast, says the skeptical viewer. If Mildred did it, why doesn’t the film show her doing it, as the Letter scene does? The absence of a reverse shot of the killer resembles the missing reverse shot in the Maltese Falcon scene. So the scene leaves some doubt about whether Mildred is guilty.

The film rushes us along, so we aren’t obliged to decide one way or the other. Eventually we can reconcile the opening with either possibility. If Mildred turns out to be innocent, we can say the film played fair by not showing the killer. If she turns out to be guilty, the missing reverse shot will be seen as simply a device to postpone telling us.

She certainly acts guilty enough in what follows. On the pier, she seems to consider leaping into the surf, only to be put off by a cop on a beat. The lubricious Wally lures her into his tavern, where she stares coldly at him before suggesting they go to the beach house. There, she locks him in, and he discovers Monte’s corpse.

Passing policemen in a patrol car see Wally break out of the house and arrest him on the beach. Mildred’s daughter Veda is briefly introduced at their home, when two policemen come to take Mildred in for questioning. She seems to feign ignorance of Monte’s death, still trying to frame Wally.

At the headquarters, the police inspector announces that they have the killer—not Wally but Mildred’s first husband Bert. Distraught, she claims Bert is innocent and to exonerate him she tells her story, taking us through her two marriages and her successful career.

At the climax of Mildred’s second flashback, she realizes that Monte’s free-spending ways have enabled Wally to cheat her out of her restaurant chain. She fetches a pistol and drives to the beach house, in a framing that reminds the first-time viewer of the film’s opening shots.

We see her walk through the house, but then the flashback breaks off. We’re taken back to the present, with her talking to the chief detective. “Monte was alone, and I killed him.” The detective replies that she’s lying; someone else was in the house. Who? Not Bert but Veda, brought in by the cops who have grabbed her when she tried to leave town.

Before Mildred can hush her, Veda snaps out, “You promised not to tell! You promised! You said you’d help me get away!” Veda became increasingly important to the plot as the years went by in Mildred’s flashbacks, but her almost total absence from the opening minutes blocks our thinking of her as a candidate for the killer’s role. Soon we’ll see the pains the narration took to make sure we didn’t spot her at the crime scene.

Mildred breaks down and launches the final flashback.

She says that she found Veda with Monte, and they admitted to being lovers. Then Veda told her that she and Monte would be married. Mildred reached for the pistol but was halted by Monte and dropped the gun. She left, just before Monte told Veda he had no intention of marrying her. “You don’t really think I could be in love with a rotten little tramp like you, do you?”

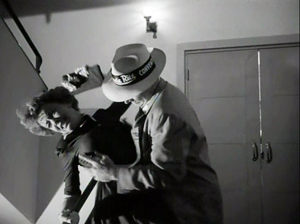

The flashback crosscuts between Mildred in the car and what’s happening inside, bringing us back to the opening situation. Now the skeptical viewer’s hunch is borne out. The replay starts as a faithful version of what we originally saw, providing the reverse shot of Veda that was missing in the opening.

This time we don’t see Monte hit (that action is covered by the shot of Veda), but he crumples and staggers forward as before. He dies, still murmuring Mildred’s name. Mildred hurries in, finds her daughter standing over Monte’s body, and succumbs to Veda’s demand that she cover for her.

The replay explains why Mildred contemplated drowning herself afterward: She was in despair at the couple’s treachery and the crime that Veda committed. When suicide was blocked, Mildred tried to frame Wally for the murder in order to protect Veda. And the replay suggests that it’s not Mildred but Veda who drives off from beach house, leaving Mildred to drift down to the pier.

All together now

At least, that’s what most viewers would remember as happening. My essay argues that it’s just this broad effect that the movie aims for: we recall the gist of the murder situation, and we assume that the only gap in it is the identity of the killer. However, when we look more closely at the two sequences, we see that Curtiz and his colleagues have covertly concealed a lot more.

To get a sense of it, you can run the two sequences separately, then the two of them jigsawed together side by side. In the following clip, the opening is labeled scene A, the flashback replay is scene B. The shots in each passage are numbered. (In the original essay, they’re laid out in a chart.)

There’s a lot of sleight-of-hand here. The extreme long shot of the beach house and driveway (A-1) seems to set the stage. The car appears empty. By the time of the gunshots (first heard in A-2), though, based on what we know from the second flashback, Mildred must be in the car already. So you could argue that the dissolve to the long-shot of the car (A-2) conceals Mildred’s departure from the house and her efforts to start the ignition (B-1). I’ve wedged that later shot into the synthesized version to show the possibility. Otherwise we must assume that the initial shot of the whole landscape (A-1) follows her going into the car (B-1). Yet in that shot or the one that follows (A-2), we don’t hear or see the driver trying to turn over the engine. In either possibility, these opening shots display the sort of subterfuges that the film will execute more significantly soon.

The presentation of the action inside the beach house misleads us from the start. After Monte is shot, over the image of the bullet-pocked mirror (A-4), we hear a door, apparently closing. Because we don’t see anyone, and we assume that a murderer flees the scene of the crime, we infer that it’s the sound of someone hurrying out. In the replay, the door’s sound is linked to Mildred coming in (B-5), not leaving.

A little extra touch: When Mildred is shown entering (B-5) we hear the door make two sounds—opening and closing. Scene A, of course, doesn’t include both, so we quickly take the one door sound we hear as signaling the killer’s departure. (To my ears, Scene A includes the sound of closing; if that’s right, A’s narration has simply omitted the sound of the door opening.)

Moreover, the filmmakers have played with the duration of the first scene to an almost criminal extreme. After the shot of the mirror and the sound of “departure,” a straight cut takes us to a peaceful but ominous long shot of Monte’s corpse in the parlor (A-5). But this shot doesn’t reflect what happened right after the murder (B-5 through B-10). When the door opened and shut, Mildred came in and immediately started talking with Veda.

The shot of Monte’s corpse, if it has any place in the chronology of the scene, belongs later, evidently after Veda and Mildred have left the parlor but before Veda has driven off (A-6). In other words, version A has presented a big ellipsis—unmarked—between the mirror shot (A-4) and the shot of the dead Monte (A-5). All the drama between mother and daughter played out in the B version has been skipped over, without any hint that it was suppressed.

The sequence proceeds by degrees of sneakiness: First, the misleading presentation of the car and the beach house, then the teasing offscreen sound of the door, then the more forcible skipping-over of the conversation. Now consider something even more flagrant. When Monte says, “Mildred,” he says it in two different ways in the two sequences, and thus creates two different effects.

In the opening scene, an abrupt medium shot (A-4) stresses the line as the dying man’s last word. We know (especially after Citizen Kane) that last words are important, and Zachary Scott dwells on it, lolling his head from side to side glancing leftward, as if he were naming his offscreen killer. But in the replay, when Monte falls (B-4), he simply slumps to one side, head down, and mutters, “Mildred,” before flopping over on his back. Nor does Curtiz provide a closer shot. Now the line is tossed off, as if Monte were simply remembering his wife in his final moments.

In sum, the replay not only fills in missing information; it corrects the inferences we made during the first scene. Of course, the film’s narration had encouraged us—at moments, forced us—to make those inferences, all with the purpose of creating a false impression about who was in the house when Monte died.

You might object that these “rewritings” of the opening show less skill than we expect today. Films like Go (1999), One Night at McCool’s (2001), and Vantage Point (2008), let alone Now You See Me and Side Effects, strive to make the fragmented replays of an event dovetail neatly. But those films have been made in an era when people had the ability, on DVD, to rewatch films closely, and persnickety viewers can check for disparities. 1945 viewers couldn’t undertake the random-access probes into Mildred that we can. Moreover, as complex flashback storytelling became more widespread in the 1990s and 2000s, I suspect that there was a certain professional pride in making the sequence of events watertight.

More generally, Curtiz and company could be confident that very few members of their audience would recall the fine detail of a scene shown a hundred minutes earlier. I argue in the essay that as the film unrolls, the rapid pace of the action and our inability to stop and go back allows the filmmakers to juggle time, space, and the sequence of actions played out.

The filmmakers count on our inability to recall fine detail. How fine? If the replay had shown Monty falling face down rather than rolling on his back, I suspect that we would have noticed the disparity. But even trained critics, as I show in my essay, at the time and afterward, didn’t notice the smaller details that deviate from the initial scene, especially the point at which Monte says, “Mildred.” Curtiz and his screenwriters have worked comfortably in a zone of fuzzy recall.

The differences between the initial scene and the replay can’t be put down to clumsiness or accident. All the disparities in the opening nudge us to draw the wrong conclusions, whether we play the trusting viewer or the skeptical one. The omission of the reverse shot, the most obvious mark that Mildred might be innocent, is a convention, as we’ve seen; but the other tactics pursued by Curtiz and company are more innovative. The filmmakers have exploited our tendency to jump to conclusions and to ignore details, always in our search for the gist of the story.

In other words, filmic storytelling often takes advantage of mistakes we make in normal thinking. It even encourages us to make them.

Thanks to Erik Gunneson for preparing the extracts for this blog entry and to web tsarina Meg Hamel for posting the essay.

The misleading narration of Mildred Pierce has its parallel in crime fiction, particularly the thrillers of the 1940s. See this entry on the site for more background. A Ruth Rendell novel, Wolf to the Slaughter (1967), contains a boldly misleading opening that is somewhat similar to what happens in our film.

Some details in the presentation suggest that Curtiz has played fair. In A-6, the woman driving off seems to have a light-colored coat, not Mildred’s heavy fur one. A viewer seeing Mildred on the pier might doubt that she took the car. Still, I don’t think everything here is perfect. Close examination of a 35mm print seems to reveal a figure in the passenger seat of the car ducking down in A-2. And does Monte, falling to the floor in A-3, move his lips slightly? Did the scene as shot have him speak the line “Mildred” at that point, as he said it in the flashback? If so, did someone decide later on the insert (A-4) that underscores his last word?

For more on the planning of this scene and the overall production of the film, see the screenplay Mildred Pierce, ed. Albert J. LaValley (University of Wisconsin Press, 1980). You can sample some of LaValley’s enlightening introduction here. The opening scene of the screenplay is quite different from that of the film, but it does retain the false clue of Monte seeming to name Mildred in his death throes.

The narrational maneuvers on display here have counterparts throughout the 1940s, which is one reason I’m interested in that era. For more examples, see this synoptic entry. The critic Parker Tyler has some provocative observations on the film in Magic and Myth of the Movies (Secker & Warburg, orig. 1947), 193-205. His comments suggest how difficult it was for audiences of the time to recall exactly what had been shown: he speaks of “the sequence of camera shots in which we see the outside of the house, the woman’s figure (or was it two figures, separately?) leaving it, her ride in the auto, her walk on the bridge, her impulse to leap over…” (195). This is a good example of the constructive tendency of memory: We fill in and seem to remember things that didn’t happen.

A more theoretical point: Some people might say that it’s unhelpful to use the term “replay” to cover both one type of flashback and the mechanical capture of earlier action. Maybe we want to call these mechanical recordings “rerun” or “playback” scenes and reserve the term “replay” just for flashbacks, the dramatized renditions of the scene’s images and/or sounds. Perhaps a close look at The Conversation would allow us to sort these concepts more exactly.

In addition, I’ve used the term “replay” to refer to those do-over plots that we find in fantasy and science-fiction films like Groundhog Day, Déjà vu, and Source Code. Yet you could argue that given the parallel-universe premise of these films, each event is shown in its singularity, in a distinct time frame. The scenes we see aren’t revisitings of a single event, but rather different events. They merely seem like replays because they repeat certain features of events that have occurred in other dimensions. I guess we need some new terms!”Reset” or “reboot” plots?

Speaking of terms, narrative theorists will recognize in Mildred’s replayed flashback what Gérard Genette calls a paralipsis. Here the narration “sidesteps” an element during the initial presentation and later revisits the situation and fills in the information. See his Narrative Discourse (Cornell University Press, 1983), 51-52.

A last musing: Might viewers exposed to publicity come into the film expecting Mildred to be the culprit? (On Mildred‘s marketing, see Mary Beth Haralovich, “Selling Mildred Pierce: A Case Study in Movie Promotion,” in Thomas Schatz, Boom and Bust: American Cinema in the 1940s (Scribners, 1997), 196-202.) The French poster below seems to put her in a doorway with a smoking gun. Or is that Veda in the doorway? Perhaps the uncertainty of the narration is prefigured by this advertisement.

On the more or less plausible sneakiness of one Preston Sturges

The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944).

DB here:

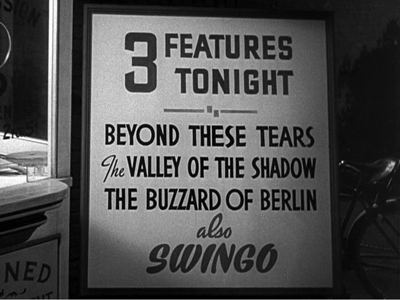

It’s no news that Preston Sturges occasionally mocked the film industry. Exhibit A is Sullivan’s Travels (1941), in which a director of escapist comedies decides to switch to serious social commentary. Sturges’ movie starts with a parody of a violent Hollywood climax that ends with two men plunging to their death. Next we’re told that Sullivan’s previous triumphs are Hey, Hey in the Hay Loft, Ants in Your Plants of 1939, and So Long, Sarong. At a later point we see a somewhat more somber triple feature:

“Swingo” is Sturges’ equivalent of Screeno and other 1930s Bingo-like games designed to lure audiences into theatres.

These gags are pretty straightforward. While working on my book on Hollywood in the 1940s, I found that The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) offers us something less obvious and more peculiar.

Three big fake features

Norval Jones (Eddie Bracken) has taken Trudy Kockenlocker (Betty Hutton) out on a date. They’ve told her highly combustible father (William Demarest) they’re going to the movies. Actually her plan is to sneak away and celebrate with soldiers about to be sent overseas. She convinces Norval to cover for her and to loan her his car. Trudy is gone all night. Drunk, pregnant, and now married to an elusive Ignatz Ratzkiwatzki, she drives up to find Norval sleeping curled up in the foyer of the movie house. In the two scenes around the Morgan’s Creek Regent theatre, Sturges wedges in some barely noticeable jabs and in-jokes.

Start with what’s playing. Four posters are in the foyer around the box office. One is sitting on an easel turned largely away from us. The other three are mostly blocked by actors, partially framed, or thrown out of focus. But by freezing the film we can make out the titles of these three fakes.

The most visible film is Chaos over Taos, clearly a Paramount release.

You can also make out The Private and the Public, which also bears the Paramount logo. Its poster is behind Norval. Much harder to discern is the title of the third feature on the program, Maggie of the Marines. It’s barely visible for a few frames, glimpsed over Trudy’s right shoulder.

Knowing Sturges’ penchant for playfulness, we can see two of these as parodies of Paramount releases. The Private and the Public seems clearly a reference to The Major and the Minor, directed by Billy Wilder and released in early fall of 1942. Sturges began shooting Morgan’s Creek in October of that year and finished in early 1943, so he would have been well aware of the Wilder film. As an extra fillip, the star of The Private and the Public is listed as Fred McMany, a reference to Paramount star Fred MacMurray.

Then there’s Chaos over Taos. The title is weird enough, relying on an eye-rhyme and being so tough to pronounce that no studio would ever choose it. The star names, Armando Torez and Maria Robles, don’t suggest any Paramount contract players to me, but this was the period when Hispanic and Latino stars began to headline Hollywood movies: Carmen Miranda, Lupé Velez, and Cesar Romero are the most famous. Emphasizing Latin American plots, players, and locations was part of Hollywood’s contribution to Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor policy. The effort was seen most famously in Disney’s wonderful Saludos Amigos cartoon (1942) but also in a series of Fox musicals with cities named in the titles (Down Argentine Way, That Night in Rio, Week-end in Havana). Chaos over Taos could be Sturges’ dig at a then-current trend in political correctness and at another studio’s production cycle. As for the genre, Chaos/Taos is a flyboy movie and Paramount made several of those—three B-films in 1941 alone (Flying Blind, Forced Landing, and Power Dive, all featuring Richard Arlen).

What then of Maggie of the Marines? It’s likely that Sturges grabbed the title from an October 1942 news story about a dog that wandered into a marine camp in the Panama Canal. Details are at the bottom of today’s entry. We can imagine the sort of heart-warming comedy it might have been, as long as Sturges wasn’t at the helm.

Etc., etc., and etc.

Finally, there’s a matter of exhibition. Just as in Sullivan, the theatre in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek proclaims a very long show: “3 Big Features Tonight, Short Subjects, Newsreel, and Boxo” (another mockery of Screeno). Norval tells Trudy that the whole shebang is scheduled to end at about 1:10.

Unlike the bill of fare in Sullivan’s Travels, the long show at Morgan’s Creek motivates plot action. Trudy uses the pretext of a long triple feature to get her father’s permission to stay out late. But it may not be too much to see in Sturges’ interest in triple features another contemporary reference.

Triple features emerged in the mid-1930s, partly because of high output from the studios and partly because of competition among exhibitors. Dan Goldberg wrote in Variety in 1938:

In a wild scramble for immediate returns without any thought to the outcome, the exhibitors have tried freaks and stunts rather than policy and operation. There have been double features, triple features, bank nite, screeno, keeno, bingo, and giveaways of all kinds, including dishes, flatware, linenware, framed pictures, wall plaques, etc., etc., and etc. There are many houses around here [Chicago] which are getting a 15c and 20c admission and giving away merchandise valued at 11c and more.

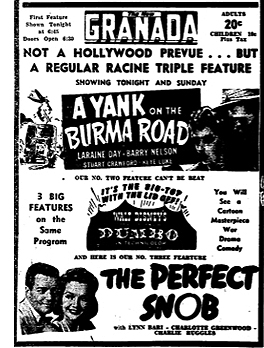

The studios hated double-feature programs but the public, voting its wallet, preferred them. Duals, as they were called, were largely a subsequent-run phenomenon, but because of the vast number of releases and block booking, they crept into first-run venues too. Triple bills were far less common and typically included two or even three B pictures. Most A-grade pictures aimed to come in under 100 minutes, and a B was typically sixty to seventy minutes long, so a triple feature of an A and two Bs wouldn’t be stupendously long. In the Racine triple feature on the right, two Bs flank Dumbo, a 62-minute movie, and the whole program, without shorts, trailers, and intermissions, would last only a little over three hours. Many triple bills seem to have consisted of three Bs. Sometimes the movies weren’t all features: a cartoon or a serial episode might be counted as one of the “Three Big Hits” advertised.

The studios hated double-feature programs but the public, voting its wallet, preferred them. Duals, as they were called, were largely a subsequent-run phenomenon, but because of the vast number of releases and block booking, they crept into first-run venues too. Triple bills were far less common and typically included two or even three B pictures. Most A-grade pictures aimed to come in under 100 minutes, and a B was typically sixty to seventy minutes long, so a triple feature of an A and two Bs wouldn’t be stupendously long. In the Racine triple feature on the right, two Bs flank Dumbo, a 62-minute movie, and the whole program, without shorts, trailers, and intermissions, would last only a little over three hours. Many triple bills seem to have consisted of three Bs. Sometimes the movies weren’t all features: a cartoon or a serial episode might be counted as one of the “Three Big Hits” advertised.

Triples were evidently less popular with audiences than duals. Perhaps people weren’t willing to spare such a big block of time, or they suspected that the lesser items on the bill weren’t worth watching. Jeff Smith suggests to me that adding a B to an A looks like a bonus, but two or three Bs look like a dumping ground. Interestingly, when Trudy tells Norval she plans to skip out on him, he protests: “I won’t do it! I won’t sit through three features all by myself.” Trudy asks plaintively: “Couldn’t you sleep through a couple of ’em?”

While Sturges was preparing Morgan’s Creek, he might well have noticed some Variety stories tracing a controversy about triple bills in the Midwest. A chain in St. Louis had shifted to this policy, and to retaliate a rival chain began four-hour shows consisting of two features and sixty minutes of shorts. In late 1940, a civic group, the Better Films Council of Greater St. Louis, put pressure on exhibitors to oppose long programs. The Council claimed that such bills were “a physical and mental strain on children and young people,” and that family-appropriate films were sometimes accompanied by “adult” ones. Getting no cooperation from the theatre circuits, the Better Film Council announced in early 1941 that it was going to introduce state legislation to ban triple features. This effort evidently came to nothing.

As if in response to bluenose worries about long programs, Sturges gives the lucky Morgan’s Creek patrons a movie banquet that ends in the wee hours. And ironically, Trudy would have suffered less “physical and mental strain” in the days and weeks thereafter if she’d gone to the movies and not kissed the boys goodbye. The Regent’s absurdly inflated program may be Sturges’ dig at both a contemporary trend and those who fretted about it.

Watching me rake these apparently innocuous frames, you may be asking: Is David going all Room-237 on us? Actually, I see today’s entry as in the spirit of an earlier one, which also has an enigmatic Sturges connection. I’m interested in the moments when Hollywood is talking to itself.

We tend to think that the studios made movies to communicate with the public, and that’s surely true. But we tend to forget that filmmakers were sometimes talking to each other. In the Zanuck-produced Hollywood Cavalcade (1939), a romance of silent-era moviemaking, director Don Ameche turns down Rin-Tin-Tin for a project. The obvious joke is that the pooch became a big star, but how many viewers would appreciate the in-joke that Zanuck launched his career at Warners writing scripts for Rinty? Did the public know that Slim and Steve, the nicknames swapped between Bogart and Bacall in To Have and Have Not, were the ones used by Hawks and his wife? Would ordinary moviegoers catch the reference to Archie Leach in His Girl Friday or notice Jed Leland’s column in the newspaper in The Magnificent Ambersons?

Some would have. Moviegoers of the day were better-educated than the populace in general, and the biggest fans went several times every week. But even if the audience missed these bits, the filmmakers’ peers might not. These movies were made by youngish people who liked to have fun–sometimes at each other’s expense—and nothing is more fun than very esoteric in-jokes.

The problem is that these other examples are highlighted in dialogue, but some of Miracle‘s in-jokes are almost completely buried. They’re more akin to the current vogue for Easter Eggs in sets and props. Unlike the recent instances, though, Sturges’s hints are hard to catch during projection, and he couldn’t have counted on viewers mulling over them frame by frame, as our directors can.

Perhaps he intended to show those posters more fully but had to forego that option during filming or cutting. Or perhaps he included them just for his own amusement–that is, not for the general public, nor even for his peers, but merely for the pleasure of putting in things that only he and his team knew about. If that seems implausible, let me ask: If you could do it, wouldn’t you?

The fourth poster, after some fiddling with the Skew and Perspective tools in PhotoShop, reveals itself as another aerial adventure: Eagle something…. Eagle Blood, maybe? For an example of a drama using real film titles in its movie marquees, see this entry.

On duals and triples, see “Triple Features Seen as Nabes’ Salvation,” Variety (22 January 1935), 3; Dan Goldberg, “Chicago Merry-Go-Round,” Variety 24 October 1938, p. 21; “Now It’s Duals, with Vaudeville, At the Loop Oriental,” Variety (25 January 1939), 5; “Single-Billing Idea Up Again But Practically It’s Still NSG,” Variety (26 August 1942), 13. On the St. Louis controversy, see “Better Film Council Queries St. L. Exhibs on Duals and Triples” Variety (23 October 1940), 21, and “St. Louis Group Seeks to Outlaw Triple Features,” Variety (26 February 1941), 21.

The embedded ad for a triple feature comes from The Racine Journal-Times (11 July 1942), 8.

No need to write me about the most obvious in-joke in Morgan’s Creek: the fact that it incorporates two major characters from The Great McGinty (1940) and doesn’t even bother to credit the actors. Cheeky, this Sturges fellow.

From The Daily Gazette (Berkeley , California, 19 October 1942).

The 1940s, mon amour

The Dark Mirror (1944).

DB here:

With the indispensable assistance of our web tsarina Meg Hamel, I’ve just put up an essay on Hollywood film of the 1940s. It’s called “Murder Culture: Adventures in 1940s Suspense.” It’s long, I warn you. But if you’re interested in American film history, thrillers, Alfred Hitchcock, or all of the above, you could find it worth checking out.

Now for a flashback. Cue track-in, soft dissolve, ominous music.

I was born in 1947, so the Hollywood cinema of that day really belonged to my parents’ generation. Yet why do I feel that the 1940s-early 1950s cinema is “my Hollywood” in a way that the 1960s and 1970s aren’t?

I was born in 1947, so the Hollywood cinema of that day really belonged to my parents’ generation. Yet why do I feel that the 1940s-early 1950s cinema is “my Hollywood” in a way that the 1960s and 1970s aren’t?

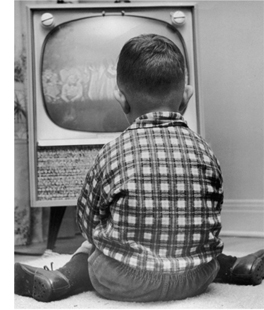

TV is a big part of the answer. Living on a farm, I saw far more movies on TV than in theatres. That’s why I don’t have as absolute a fetishism for 35mm as my baby-boom peers who grew up in cities. They could amble down to the local Bijou every day after school and soak up current movies and classics. I couldn’t, so I can sympathize with kids today who see most of their movies on monitors. That’s what I did, and—truth be told—what many urban cinephiles did too.

What I could see, thanks to Rochester and Syracuse television stations, were those films that had sold in packages of 16mm prints. Fattened out by with commercials, sometimes trimmed to fit schedules, old movies were treated as filler. And while some of the 1930s movies, chiefly the Bs featuring Mr. Moto and Charlie Chan, became lifelong favorites, it was mostly the 1940s and early 1950s films that stuck with me.

There were Citizen Kane and Magnificent Ambersons, of course, which movie books steered me toward. But there was also Ball of Fire, For Whom the Bell Tolls (in black and white), and Suspicion. Those I remember most vividly, but today, watching some obscure 40s item, I find dim memories of that sometimes flaring up too.

From college through graduate school, I made 1940s Hollywood a touchstone. My first published essay, back in 1969, was on Notorious. As a film collector, I favored 1940s things, from His Girl Friday and Fallen Angel to Ministry of Fear (below) and The Shop around the Corner. When I started teaching at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research enabled me catch up on Warners, RKO, and even the stray Monogram. In my courses we showed prizes like Meet Me in St. Louis and The Locket. I was happy when several of my students, such as Diane Waldman, Brian Rose, and Fina Bathrick, took up 1940s topics for their research.

The era pulled in my research too. In Narration in the Fiction Film my preferences were exposed; some friends noticed that most of my prime American examples (The Big Sleep, In This Our Life, Murder My Sweet, The Killers, Secret beyond the Door, Shadow of a Doubt, Rear Window, etc.) came from the 1940s and early 1950s. The conversation sort of went like this. Q: So I guess for you, David, every narrative is a mystery? A: Yes.

In The Classical Hollywood Cinema I could justify my 40s emphasis because that era saw significant changes in storytelling. I couldn’t avoid all those flashbacks, all that deep focus, all that noir and melodrama. Still, as my examples of ordinary Hollywood sound picture I picked Play Girl (1940) and The Black Hand (1949). Likewise, when I wrote an article about how we’re led to forget key story information, I fastened on Mildred Pierce. And one theme of The Way Hollywood Tells It, a book purportedly about contemporary moviemaking, is the debt that the Movie Brats and their successors owe to the 1940s.

No surprise, then, that when I was asked in 2011 to prepare some lectures for Belgium’s summer film college, I decided to revisit 1940s Hollywood. I began preparing in the spring, and had plenty of time to watch films while I was hospitalized with pneumonia. The more I watched, the more I came to believe that we still don’t know this period in its full artistic richness–and peculiarities.

True, we have plenty of studies that see all sorts of 40s films as reflections of the war or postwar malaise. Certainly, as well, the literature on film noir and the female Gothic will continue to grow. (Indeed, these categories weren’t available to people of the time; they just called those movies “melodramas.”) But I wanted to explore broader trends in cinematic storytelling that were pioneered or consolidated after 1940 or so. That meant looking at family sagas like How Green Was My Valley (see Kristin’s post here), as well as dramas like Daisy Kenyon and All About Eve and other things that caught my interest.

During a July week in Antwerp, I delivered the lectures. It was exhilarating to re-see the films in 35 and discuss them with a lively bunch of participants. But my ideas kept developing. I couldn’t shake the films and the spell they cast on me. Over two years I’ve continued to watch and read and turn ideas over.

End of flashback. Cue soft dissolve, track out, music with warmer harmonies.

I’m now writing a book, one that’s relatively short (honest!) and that, I hope, creates an original perspective on American film of the 1940s. Although the new piece centers on the suspense thriller, the book will look at other genres too. You can get the flavor of the project from these entries on the 1940s and early 1950s:

“Intensified continuity revisited.” The Shop around the Corner vs. You’ve Got Mail.

“Creating a classic, with a little help from your pirate friends.” How His Girl Friday acquired its stature today.

“Foreground, background, playground.” This is a trailer for “William Cameron Menzies: One Forceful, Impressive Idea.”

“Chinese Boxes, Russian dolls, and Hollywood movies.” On embedded flashbacks.

“Julie, Julia, and the house that talked.” On narrational strategies and wild time schemes.

“Puppetry and ventriloquism.” Bits and pieces from the 2011 lectures, focusing on anti-realism and competition among directors.

“Despoiling the movies.” On 1940s attendance habits.

“Pike’s peek.” Imaginary product placement.

“Play it again, Joan.” Analyzes the technique of replaying scenes seen or heard earlier.

“Bette Davis eyelids.” Joan’s rival and her performance tactics.

“Hand jive.” General piece on performance and gesture, with discussion of All the King’s Men.

“I Love a Mystery: Extra-credit reading.” A sort of dry run for the web essay.

“Alignment, Allegiance, and Murder.” How Lang attaches us to characters in House by the River.

“DIAL M FOR MURDER: Hitchcock frets not at his narrow room.” Touches on Dial M‘s debt to 1940s experiments.

“A dose of DOS: Trade secrets from Selznick.” On Selznick’s films, including those directed by Hitchcock.

“SIDE EFFECTS and SAFE HAVEN: Out of the past.” On current thrillers’ debt to the 1940s; ties to today’s web essay.

Most of these and much of the new “Murder Culture” essay probably won’t surface in the final book. I wrote the pieces in order to clarify some research questions and to sketch out some answers. If you have any suggestions or corrections, feel free to correspond.

Meet Me in St. Louis (1944).

SIDE EFFECTS and SAFE HAVEN: Out of the past

Safe Haven; Side Effects.

DB here:

Occasionally someone will ask me how I watch a movie. Here’s a stab at an answer. If the film presents a story, fictional or nonfictional, I try to get engaged by it, as most viewers do. I also try to watch for how the filmmaker shapes sounds and images. Such things are hard to analyze on the fly, but we can at least be shot-conscious. I suppose as well there’s a small part of me asking whether what I’m watching is good or bad. Another part takes notice of what many viewers spot today: the sorts of story roles allotted to women and members of minorities.

At the same time, one module in my head seems to be looking for historical precedents and parallels to what I’m seeing. The purpose isn’t to dismiss current movies with “Aw, this has been done long ago.” Instead, I think I’m looking for ways in which earlier forms and styles are accepted, recast, or rejected by the creative choices being made today.

For instance, as I was watching Safe Haven and Side Effects, I was thinking of the 1940s.

Not that other periods haven’t left their traces. Both movies depend on crosscutting, something that goes back to the 1910s, as does the goal-oriented protagonist. Both rely as well on analytical editing, with Soderbergh in his usual spare way minimizing establishing shots in favor of compact constructive editing. The wobbly handheld shots cropping up in both films hark back to the 1960s and filmmakers’ periodic revival of them. Four-part structure: check. Rule of three: check. And so on.

But what popped out at me was something that I’ve noticed before. Films of the last twenty years or so borrow a lot of storytelling strategies that originated in the 1940s and carried through into the early 1950s.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I argued that 1990s Hollywood drew upon this heritage and in some ways pushed it farther. It isn’t just neo-noirs like Reservoir Dogs and Memento that owe a debt to the earlier period. Lots of films in many genres now casually use flashbacks, voice-overs, restricted points of view, multiple protagonists, network narratives, and replays of scenes from different perspectives—all strategies pioneered or consolidated in the 1940s. These techniques have become so accepted a part of mainstream moviemaking that we may forget that a comedy like The Hangover or a prestige drama like The Iron Lady presents fairly elaborate time schemes or tricks of character subjectivity.

We also tend to ignore the sheer eccentricity of the period. The 1940s introduced movies letting a house tell the story or embedding flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks. Characters dreamed things that came true, or realized that they were actually dead. Sometimes dead people narrated the story. All in all, things got pretty strange.

Part of that era’s legacy is the suspense thriller as we know it. I’ll be putting up a web essay on the development of the genre soon, but for now consider these two recent releases as heirs of that tradition. Of course there are big spoilers ahead.

Spooked

Like many 1940s thrillers, Safe Haven centers on a woman in peril. Most often the heroine is trapped in a house, and an unseen force or a ruthless husband is trying to kill or incapacitate her. The prototype is Gaslight (1944), where as often happens, the wife is rescued by a “helper male,” a romantic alternative to the husband. Variants of this plot include The Spiral Staircase (1946) and The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947). This sort of domestic thriller, sometimes called a Gothic, tends to fill household spaces and everyday routines with vague threats.

Instead of confining its protagonist, Safe Haven builds its plot around a woman who has left home behind. Fleeing an abusive marriage, Erin arrives in a North Carolina town and slowly enters a love affair with Alex, a widower who runs a convenience store. Meanwhile her husband Kevin tries to track her down. The fairly conventional budding romance, as Erin joins Alex and his kids in forming a new family, is threatened by the prospect of Kevin finding her and dragging her back home. As a policeman, Kevin has unusual forces at his disposal: a crucial turning point is his putting out an unauthorized wanted poster. Not only does this endanger Erin’s new identity, but when Alex sees the poster, he breaks off their affair.

On-the-run plots are usually the province of male-centered thrillers like The 39 Steps and North by Northwest. It isn’t unknown, though, to make the woman a moving target. One of my favorites is Double Jeopardy (1999), in which Ashley Judd plays a wife convicted of her husband’s murder. When she learns that he faked his death, she realizes that she can’t be tried again for killing him. Released on parole, she pursues him, while her tenacious parole officer pursues her. An older example is Woman in Hiding (1949), in which Ida Lupino plays a wife who is supposedly murdered by her husband. Actually, she eludes death and tries to flee him, but he, discovering she’s still alive, catches up with her on a hotel staircase.

In such thrillers, there are two common ways you can generate suspense. Both depend on range of knowledge, as Alfred Hitchcock pointed out in 1947.

The author may let both reader and character share the knowledge of the nature of the dangers which threaten. . . . Sometimes, however, the reader alone may realize that peril is in the offing, and watch the characters moving to meet it in blissful ignorance and disquieting unconcern.

That is, the narration can attach us to a character and limit our knowledge to what she knows. Examples of this are Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940) and Suspicion (1941), which quite strictly confine us to the heroine’s range of knowledge.

Safe Haven, like Woman in Hiding, takes the alternative option: omniscience, or what Hitchcock calls “sharing the knowledge of the dangers.” Crosscut scenes show Erin in Southport while Kevin follows her trail. Other crosscut scenes introduce us to Alex’s problems of raising his kids and grieving for his wife.

As Erin gradually settles into the community, we know that Kevin is closing in. He arrives during a town celebration, and the crosscutting becomes tighter. Thanks to Kevin, the store catches fire and endangers Alex’s daughter, while Kevin drunkenly wrestles with Erin at gunpoint.

Suspense and mystery go hand in hand, and suspense films have a habit of suppressing information about past events. Woman in Hiding begins with the wife’s car plunging into the river; later we get a flashback explaining what led up to the accident. Safe Haven begins with a black-haired woman hysterically running out of a house and taking refuge with a neighbor. What has led to this? The woman, now a blonde, then boards a bus, while we see a man with police credentials questioning witnesses and stopping other buses.

The plot is organized so that we don’t know for quite some time why Erin is being pursued by this exceptionally zealous detective. And some fragmentary flashbacks, mostly in the form of dreams (a favorite 40s device), hint that she has killed a man. Gradually, however, there are hints that this cop isn’t what he seems. Not until the end of the third part (circa 80:00) do we learn from a full flashback that the cop is her husband. Kevin is a crazed alcoholic who began to strangle Erin one evening; she stabbed him and fled her home. The teasing flashbacks, along with the suggestion that Kevin’s pursuit is an official inquiry rather than a private vendetta, misled us. What we saw at the start was Erin escaping from an abusive marriage.

A lower-key form of delayed and distributed exposition involves Alex and his kids. Instead of filling us in immediately on Alex’s life with his wife, we learn of their married life gradually. After Alex has fallen in love with Erin, he retreats to a room kept in memory of his dead wife. He riffles through letters she left behind, to be given to Josh and Lexie when they grow up. Later, Alex abandons Erin because of the wanted poster, and he retreats to his wife’s room, where he has a change of heart and goes to bring her into the home.

Why the change of heart? An unusual aspect of Safe House is the injection of, ah, otherworldly intervention. While living in her cabin, Erin meets a neighbor, Jo, who encourages her to get to know Alex. In the epilogue, Alex gives Erin one of the letters from his wife’s desk, labeled simply, “To Her.” It’s a sympathetic message expressing the wife’s support for the next woman to be wife and mother to her family. The picture inside is of Jo. Earlier, in the sacred space of Jo’s room, Alex seems to grasp that he has to reunite with Erin. At the climax, Erin, dreams that Jo is warning her that Kevin has caught up with her. As angel, ghost, or spirit—you choose—Jo has brought everyone together.

Reviewers, in this cynical age, scoffed at this device. I didn’t mind it because I liked its tie to tradition. Ghosts and angels have haunted American cinema from the start, but in the 1940s they played very prominent roles—not just in comedies like Topper Returns (1941) but in dramas. Beyond Tomorrow (1940), Our Town (1940), Happy Land (1943), A Guy Named Joe (1943), The Uninvited (1944), It’s a Wonderful Life (1947), and many other films unashamedly introduced supernatural beings as moral guides to the living. True, those films build their spooks into the premises of the plot early on, while Safe Haven saves its for a Big Reveal. But after The Sixth Sense (1999), this sort of twist shouldn’t seem too upsetting. (A second viewing reveals that Jo is unnaturally disturbed when it looks like Erin won’t bond with the family, and a few lines of dialogue take on new meanings when you know that Jo is dead.) Perhaps the gimmick seems wimpier when it’s invoked in a romantic thriller than in a masculine investigation plot.

Recommended dosage

Steven Soderbergh is one of our most exploratory directors, a filmmaker who tries different things without making a big deal about it. He’s also a cinephile who, like Cameron Crowe, admires and quietly adapts classic studio traditions. He turns out lots of movies, a habit reminiscent of the contract director of yore.

I was skeptical of his pastiche The Good German (2006), but I do admire his compact, unfussy direction, as I mentioned here. I’m a big fan of Out of Sight (1998), and I think his last batch of films, from Contagion (2011) through Haywire (2012) and Magic Mike (2012), shows him to be a director whose every project is solid and intriguing. It’s a pity he’s announced his retirement after the upcoming Liberace project.

I doubt that in Safe Haven Lasse Hallström was consciously channeling 1940s suspense thrillers, but it seems likely that Soderbergh was trying his hand at something deliberately Hitchcockian. (Reviewers needed no nudging to make the comparison.) Beyond comparisons with the Master of Suspense, Side Effects’s debt extends to two plot patterns of the 1940-early 1950s that Scott Z. Burns’s script ingeniously combines.

The first is what I call the Crazy Lady plot. The Snake Pit (1948) is probably the clearest example, but there are many others, including Bewitched (1945), Dark Mirror (1946), The Locket (1946), Shock (1946), Possessed (1947), and Whirlpool (1950). The plot pattern can be found in literary thrillers too, such as Margaret Millar’s The Iron Gates (1945) and John Franklin Bardin’s fine Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly (1948). Hitchcock didn’t tackle a Crazy Lady plot until Marnie (1964), but in the 1940s he tried a Crazy Gentleman variation in Spellbound (1945).

In such films, the woman is the mystery. What is wrong with her? Why do her problems have such horrible consequences for her and others? Often the woman displays an abnormal division in her mind: the prospect of a split personality is never far off. The key factor is that her behavior is inconsistent. A rich woman shoplifts (Whirlpool), a sweet girl fatally stabs her fiancé (Bewitched). Accordingly, only a psychoanalyst can probe the sick woman’s behavior and track down the founding trauma, typically something that happened in childhood. A crucial convention is the scene in which the woman breaks through and realizes what ails her, as in this moment from Whirlpool. It’s typical of this plot that therapeutic dialogue is often paralleled by police questioning.

Side Effects gives the Crazy Lady’s mental problems a modern spin. Emily is suffering from depression, and her husband Martin’s recent release from prison hasn’t helped her recover. After ramming her car into a parking-garage wall, she’s cared for by Jonathan, a hospital psychiatrist also in private practice. He starts her on antidepressants, eventually giving her one recommended by Emily’s previous psychiatrist, Victoria. This seems to help, although it induces Emily to sleepwalk. While she’s apparently sleepwalking, she stabs Martin to death.

Now Jonathan is in a bind. If the drug Ablixa has been misprescribed, Jonathan is responsible for Martin’s death and Emily’s fate. Jonathan defends Emily and his testimony helps win a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity. He continues to supervise her recovery while his career collapses. His patients abandon him, his partners cast him out of their business, and he’s dropped from a lucrative experiment. He’s also being investigated by his professional association.

In other words, Jonathan is now fulfilling a second 1940s plot pattern: The innocent man trapped by circumstance. He might be a murder suspect (Stranger on the Third Floor, 1940; Phantom Lady, 1944; The Big Clock, 1948) or an ordinary guy dropped into international intrigue (Journey into Fear, 1943; The Ministry of Fear, 1944). Side Effects combines this noirish convention with the Crazy Lady plot. It turns out that Emily and Victoria have conspired to set up Martin’s death. Emily actually hates her husband, and she’s learned enough from his insider-trading schemes to understand that a scandal could drive down Ablixa’s stock price. She and Victoria, who have become lovers, can make millions as a result of the murder.

Yet suspecting all this doesn’t help Jonathan. Emily can’t be tried again, and as Jonathan begins to grasp their scheme, Victoria draws the net tighter around him. She sends his wife faked photos suggesting that he and Emily have had an affair.

In 1947, novelist Mitchell Wilson pointed out an important convention of the thriller. He claimed that the defining feature of the genre was a fear felt by the protagonist that is communicated to the reader: the protagonist is in continual danger. But when the threat reaches its peak, the worm must turn.

The framework of the suspense story is the continual struggle of the frightened protagonist to fight back and save himself in spite of his pervading anxiety, and in this respect he is truly heroic. The action of the story does not consist in mere activity, but in the hero’s change of mood in response to changing circumstances.

Jonathan’s desperation leads him to concoct a scam of his own. Since Emily is in prison and can’t communicate with Victoria, he is able to play them off against one another. Holding a physician’s control over Emily, he can convince her to double-cross Victoria and unmask her. Then he double-crosses Emily and consigns her to the asylum while returning to his family.

Again, I’ve ironed out the ups and downs of the film in order to lay out the plot’s design. In the actual telling, we’re attached first to Emily and then more closely to Jonathan. The overall pattern resembles that of Whirlpool, which concentrates first on the way the wife’s kleptomania draws her to the sinister therapist Korvo, and then shifts to the investigation undertaken by the police and her husband, a psychoanalyst. (Whirlpool, like Side Effects, centers on dueling shrinks.)

Here the Crazy Lady premise is a masquerade, and Soderbergh “plays fair” with us about it. The 1940s films rely on mental subjectivity—voice-over inner monologues, exaggerated sound effects, hallucinations, dream imagery—in order to show that the protagonist is truly wacko. Side Effects presents Emily objectively, relying on somber color schemes, top lighting, and Rooney Mara’s morose demeanor to suggest a young woman struggling against depression.

From the outside we watch Emily’s glum visits to Martin in prison, their frustrated sex when he gets out, her impassive crashing of her car, her confiding in her boss, and her breakdown at a cocktail party. There are a few optical POV shots, but those are justified as Emily’s numb stare–although Soderbergh does sneak past us a POV shot that, because of distorting glass, might seem to be projecting Emily’s state of mind expressionistically. (See above.) Virtually everything we see suggests a woman losing control, so that when Emily perks up after going on Ablixa, we, like Jonathan and Martin, think she’s recovering.

Safe Haven leads us to jump to a conclusion—that the cop pursuing Erin is doing so legitimately—only to rescind that by filling out the teasing fragmentary flashbacks. Side Effects does something similar, but through simple ellipsis. The plot lets us think that Emily is genuinely depressed by skipping over things it could have shown, such as her fake vomiting or her dumping the prescription pills down the toilet. Only at the climax, when Jonathan wrings the truth from Emily, do we get subjective imagery. There are artificially sun-sprayed flashbacks of her days with Martin just before his arrest, as well as glimpses of her therapy with Victoria, followed by replays of the suicide attempts, now revealed as faked.

The 1940s popularized this sort of filling-in flashback, in which a replay shows items that were left out of an earlier presentation. The most famous example is the return to the opening of Mildred Pierce (1945). Now as then, we can’t completely trust a thriller’s narration. There are mysteries in the story, but there are also mysteries in the storytelling. No matter how much a thriller seems to tell us, key information is usually held back, and the suppression won’t always be signaled. To get Rumsfeldian: there are always known unknowns, but thrillers trade in unknown unknowns, data we didn’t realize were there.

There’s a lot more to say about these movies. For example, both trade on a premise common to the 1940s and American movies thereafter. Call it the Margaritaville Rule: There’s a woman to blame. Erin brings calamity to Southport and trauma to her would-be family, and Jonathan’s travails are the result of two scheming women, seconded by a hard-edged wife who won’t hear out his explanations.

Moreover, I hope it’s clear that I don’t think these two recent releases are merely cloning 1940s conventions. They incorporate subjects and themes of our time, like spousal abuse and the insidious power of Big Pharma. They exhibit some innovative plotting, such as the revelation of a guiding spirit in Safe Haven and the combination of Crazy Lady premises with the Cornered Innocent in Side Effects. And Soderbergh’s offers an exercise in crisp direction, from its conventional opening shot to its grimly symmetrical closing one.

My point is simple: However new our films may seem, whether they’re accomplished (Side Effects) or banal (Safe Haven), in important respects they’re continuing traditions that go back decades.

Why then, you may ask, do so many academics and journalists insist that classical cinematic storytelling is dead? Why do they so resolutely ignore the evidence of continuity between today’s films and those that went before? That’s a mystery I can’t solve.

Hitchcock’s remark about the range of knowledge and suspense comes from “Introduction: The Quality of Suspense,” Alfred Hitchcock’s Fireside Book of Suspense (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1947), viii. Mitchell Wilson’s remarks on fighting back are in “The Suspense Story,” The Writer 60, 1(January 1947), 16. His novel None So Blind (1945) became the Renoir film Woman on the Beach (1947).

The idea of the “helper male” in the Gothic is developed by Diane Waldman in “’At last I can tell it to someone!’: Feminine Point of View and Subjectivity in the Gothic Romance Film of the 1940s,” Cinema Journal 23,2 (Winter 1984), 29-40.

For more background on the 1940s thriller, see the web essay, “Murder Culture: Adventures in 1940s Suspense” and this blog entry. Another blog entry discusses replays in 1940s and 1950s American film. For more arguments about the debts of today’s films to studio Hollywood, see The Way Hollywood Tells It and other entries on this site. I analyze the duplicitous opening of Mildred Pierce, along with its revelatory replay, in this entry and its accompanying video.

Today’s entry neglects another important component of Side Effects: the music. For that, see Roger Ebert’s acute review. Expressive scores are, needless to say, central to 40s thrillers too.

Mike Grost’s encyclopedic website supplies a great deal of information about the mystery genre.

Side Effects.

P. S. 24 March 2013: Thanks to Gabe Klinger for correcting a dumb date mistake!