Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

A dose of DOS: Trade secrets from Selznick

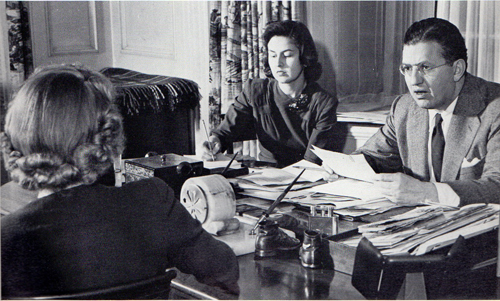

David O. Selznick dictating a memo in 1941. Secretaries are Virginia Olds (back to camera) and Frances Inglis.

DB here:

Tucked neatly within over 4500 archive boxes in Austin, Texas, are tens of thousands of items of information about how the Hollywood studio system worked. The trick is to find the ones you’re looking for…and the ones you didn’t know you should be looking for.

Those archive boxes are housed at the Harry Ransom Research Center at the University of Texas. This magnificent research library holds cultural records of inestimable value, from Whitman and Poe manuscripts to the papers of David Foster Wallace. Among the Center’s impressive film collections, the jewel in the crown is the David O. Selznick papers—a vast trove of material related to the career of the man who produced, some would say over-produced, Gone with the Wind, Rebecca, Spellbound, Duel in the Sun, and other classics of the Hollywood system.

Selznick has been studied from many angles, partly because his collection provides exceptionally full accounts of his activities. He kept, it seems, nearly everything, most famously memoranda. While chainsmoking cigarettes, swallowing amphetamines, writing amateur poetry, and revising scripts and visiting sets and critiquing rehearsals and watching rushes and retaking scenes and checking on rivals’ films, Selznick found time to dictate a blizzard of memos.

From his youth he loved to write memos–“I could sell an idea much better in written form than I could verbally”–and he became adept at dictating them. The results were precise, punchy, and often eloquent. Usually signed DOS (the O being a middle initial he bestowed upon himself), these communiqués could be lapidary (a one-liner asking if the cast is protected from sunburn) or epic. After getting Selznick’s dense, eight-page telegram explaining why Since You Went Away’s nearly three hours could not be reduced, a colleague replied: IF I WERE YOU I WOULD MAKE NO FURTHER CUTS IN SYWA. YOU MIGHT TAKE ABOUT TEN MINUTES OUT OF YOUR TELEGRAM.

In his later years Selznick contemplated publishing a collection called Memo Strikes Back. After he died in 1965, his son encouraged film historian Rudy Behlmer to make a compilation. The result, Memo from David O. Selznick (1972), is a superb collage portrait of the man’s personality and creative years. In the 1980s, the Ransom Center acquired the papers that Behlmer worked through, along with physical artifacts, including costumes from GWTW.

Me-mos, they were called by many, since they seemed to reflect the compulsive micromanaging of their creator. Directors and staff smarted under Selznick’s insistence that he control every creative decision. But for those of us coming afterward, Selznick’s criticisms, complaints, demands, reminiscences, agonies of frustration, and I-told-you-sos help us grasp the concrete problems of filmmaking.

Last week I went to Austin hoping to get some information about how Hollywood creators of the 1940s regarded the task of storytelling. DOS delivered as he did on the screen: splashily.

Paper traces

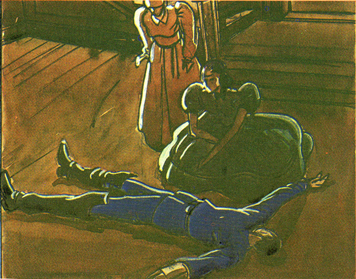

William Cameron Menzies production sketch for Gone with the Wind.

Most commentary on movies stops with the films as we find them. Critics who concentrate on producing interpretations are particularly inclined to play down primary-document research. “We already know,” a famous English critic once told me, “all we need to know.”

In my youth I mostly agreed. Criticism starts with watching and listening closely to what’s happening on the screen. But it doesn’t have to end there. That’s because doing systematic research into film depends on asking questions. And if we’re going beyond a single movie and asking questions about craft, norms, preferred practices, and regulative principles shaping a filmic tradition–in short, questions of film poetics–evidence from practitioners can help a lot.

Hollywood, for instance, has produced a rich array of published materials–interviews, trade coverage, promotion, technical papers–that offer evidence of what filmmakers thought they were doing. You have to read them with a jaundiced eye and be alert for rhetoric, but there’s still a lot to be found in Hollywood’s public presentation of its doings. There’s an even richer lode of unpublished script drafts, production memos, correspondence, transcripts of meetings, court cases, and the like. Mountains of such material remain locked up in studio files. This is what makes the paper collections at major universities, at the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy, at the Museum of Modern Art, and at other institutions precious to those of us studying film history.

Collections like these are grist for the perpetual flow of celebrity biographies and accounts of Hollywood as a business. What, though, can they tell us about the history of film form and style?

Like some published material, these items can suggest how aware filmmakers were of their creative choices. When I was teaching, and the class focused on details of framing or cutting, some students were skeptical. “This is reading too much in,” they’d say. “The director couldn’t have intended that!” And it’s true that sometimes things we think were carefully planned came about through accident or sudden inspiration. Still, in other cases a document shows that filmmakers were consciously aiming at fine-grained effects.

Moreover, archive documents can indicate the array of creative options available—the extent to which one artistic choice is preferred over alternatives that wouldn’t work as well. If filmmaking is problem-solving, we learn about the costs and benefits of competing solutions. We gain a better sense of what can and can’t be done within a tradition when we glimpse filmmakers struggling to decide between expressive possibilities.

Yet another benefit of paging through archival documents is the recognition that we can’t neatly separate filmmaking as business from filmaking as an art. We commonly imagine a studio producer ordering a director to take the cheapest option, to trim costs in every way. Surely this happened a lot. Surprisingly often, though, the suits did and still do invest a lot in artistic effects, even innovative ones. When writing our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, we were struck by the power of the idea of the “quality film,” that mixture of novelty, showmanship, and high production values that justifies time and resources. A flamboyant crane shot, a complicated lighting scheme, a gorgeous musical score, flashy special effects—in the Hollywood tradition and others, these are appeals worth paying for, even if not every viewer appreciates them.

Perhaps above all, studying records can call our attention to aspects of the film that your initial impression didn’t pick out. A critic can’t notice everything. Examining collections such as Selznick’s, or those housed in our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, have taught me that what appears effortless or perfunctory on the screen can be the product of intense thought, protracted debate, and hours of hard work. Once you re-tune your attention, even minor moments can be worth thinking about, if only because the filmmakers labored patiently over them.

Getting what you pay for

Since You Went Away (1944).

Selnick was a fussbudget on a scale that makes Schulz’s Lucy look laid-back. He sought control over every aspect of the film, from purchase of material through production, post-production, publicity, and distribution. Gone with the Wind’s volcanic success seemed to confirm the wisdom of his endless tracking of every detail. Because that tracking is made explicit, not to say vehement, in his memos and other correspondence, we get glimpses of Hollywood’s artistic strategies large and small.

Start small. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production, I wrote about the “rule of three”–the guideline that presses filmmakers to state important story information three times, preferably with variations (serious/ funny/ pathetic). I gleaned that precept from reading published work, and I could check it by studying the films. Still, further evidence is always welcome, so it’s nice to see a transcript of a story conference during the prolonged rewriting of Portrait of Jennie (1949). The hero, the painter Eben Adams, comes to a coastal town in search of his dream-girl, and DOS suggests:

In every scene he is to ask: “Do you remember a girl named Jennie Appleton?” Use rule of three–two [townfolk] do not remember her–the third one does. . . “Remember her well. . . pretty young thing with dark hair.”

More recently, I’ve been wondering whether studio screenwriters of the 1930s and 1940s were consciously adhering to something like today’s notion of a three-act structure. I’ve found scattered evidence from memos elsewhere that refer to a movie’s “first act” or “last act,” but nothing that indicates a commitment to an overarching three-part layout.

I haven’t found clear-cut evidence in DOS’s papers either, but in another story conference on Jennie, Broadway showman Jed Harris is reported as saying: “The second act–he must get the picture back because that’s all he’ll ever have of her.” In the finished film, Eben doesn’t search for the portrait, but Harris’s remark indicates that he had some sort of multiple-act structure in the back of his mind. He adds later: “The picture at this point is about 1/3 gone, and from here you have the machinery of trying to stop what is impossible to stop.” Far from definitive evidence, but teasing.

Now consider a medium-size example. Kristin and I have argued that many Hollywood films have a symmetrical opening-and-closing structure, often presented as an epilogue that mirrors the beginning. More recently I suggested that this bookend structure often displays an advance/ retreat pattern. At the start, the camera may move into a space or a character may come toward us; at the end, the camera may retreat and/or the characters may turn away or walk into the distance. On Since You Went Away (1944), Selznick sweated over ways to frame this panorama of the American home front. Early on he decided to start his film with an exterior view of the Hilton family home. This image dissolves to a closer view showing a star in the window, which indicates that a member of the family is in the armed forces.

Eventually Selznick decided to end the film by pulling back from a miniature of the house, with a single camera movement replacing the two unmoving shots that started things off. Anne is joyfully embracing her two daughters; they’re inserted as a matte into the upstairs window.

Selznick considered redoing the opening as a slow camera movement in to the window, but only if the miniature was good enough. Perhaps it wasn’t. And at one point he wanted the final shot to start with the star in the window, at least for purposes of the preview screening, “to parallel that at the beginning of the picture.” Again, that wasn’t accomplished, but his playing with possibilities reflects his tradition’s commitment to symmetrical openings and closings.

It would have been far cheaper simply to have ended the film on the three-shot of the women, shown at the top of this section. But Selznick wanted “a nice rounded feeling” in his epilogue, and he was prepared to pay for it. True, he was exceptionally finicky, but going to a lot of trouble and expense to get this formal rhyme was not unusual in studio practice. The hardheaded film business is willing to invest in vivid, emotionally gripping artistry identified with quality moviemaking.

Stylistic trends

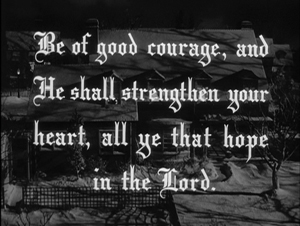

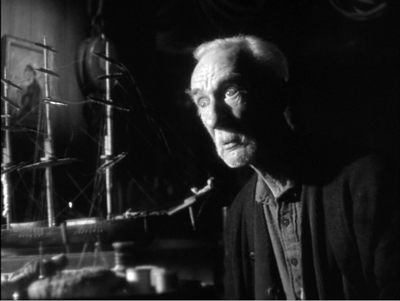

Portrait of Jennie (1949).

In broad terms, it’s fair to say that American studio films of the 1940s display a more self-conscious use of long takes, sustained camera movements, and deep-focus cinematography than we find in other eras. (Actually, it’s a trend we find throughout the world at the time, for reasons that aren’t well understood.) But these new techniques didn’t replace traditional analytical editing. They worked within it. Continuity cutting, established in America in the late 1910s, remained the dominant stylistic framework for filmmakers.

Citizen Kane‘s fixed single-shot scenes in depth were very unusual in cinema of the period. More commonly, deep-focus shots, like moving-camera shots, served as establishing framings or otherwise became part of conventionally edited sequences. This middling or compromise style can be found in dozens of films of the forties, and Selznick seems to have more or less consciously gone along with it.

He worried about what he called “cuttiness,” the tendency to break every scene into brief single shots of the players. Often, he suggested, a well-handled two-shot would work better. He told his editor on Since You Went Away to avoid “the conventional treatment of close-ups and reactions.”

It most definitely is not necessary always to treat every one of our scenes with dead center close-ups, and direct cuts or over-the-shoulder angles, when an intimate scene is played between two people.

He goes on to tell a second-unit director that a scene of a couple in a car could be played in one or two setups, perhaps in a single shot “if we could get an interesting composition on the two of them rather than a dead center two-shot on individuals.”

Selznick saw Hitchcock as an editing-biased director and so after signing him to make Rebecca (1940), he warned him and other members of the team to avoid over-cutting. Again, the preference was for a tight two-shot.

The new scene between the girl and Mrs. Danvers on the arrival at Manderley (Script Scenes 130A, 130N and 131) may be very cutty as described in the script, and perhaps ought to be protected in a close two-shot of ‘I’ [the heroine] and Mrs. Danvers, or some other angle that will keep us from playing it in too many short cuts.

In most cases, however, Selznick gave himself an out by treating faster cutting as an alternative. He consistently wanted coverage, as he indicates immediately for the Rebecca scene just mentioned.

However, I suggest we make the short cuts also, as this may be the best way of playing it after all. If we use the camera to move up to Mrs. Danvers for the finish, which is the way I think it should be used, then perhaps the first shot of her should be retaken also.

As the last sentence indicates, Selznick sometimes opts for camera movement to avoid cuttiness. Perhaps the American Hitchcock’s interest in tracking shots that follow characters, particularly glamorous women, through the set stemmed from Selznick’s belief in the power of occasional camera movements. He notes that a tracking shot introducing Alida Valli in The Paradine Case (1948) is too bumpy, asking why the staff couldn’t manage “something as simple as going up to a woman’s face, and then pulling back from it across a set, without the camera shaking in the manner of early silent pictures.”

Yet these longish takes aren’t to be the dominant stylistic approach. Sustained takes often block off choices in post-production. Producers, then and now, want coverage, and you didn’t have to be a micromanager like Selznick to want your directors to give you options for rebuilding scenes in the cutting room. We see this when Selznick objects to John Cromwell’s playing entire scenes in lengthy shots.

This is of course nonsense, since as often as not an incomplete take is better than the identical portion of a complete take. . . . It seems folly to spend hours getting a complete scene instead of just picking up those sections of the beginning or middle or end that have been fluffed.

Some directors resisted by shooting long takes without coverage. Hitchcock did this in one sequence of The Paradine Case and then promoted this “three and a half-minute take” to the Hollywood community, perhaps to make it harder for Selznick to change it. Nonetheless, Selznick cut the scene up. Once freed from Selznick, of course, Hitchcock was able to pursue the long-take option to extremes with Rope (1948) and Under Capricorn (1949).

Despite wanting flexibility in editing, producers can be seduced by the prospect of “pre-cutting” a film–planning the shots so exactly that the film can be “pre-visualized.” The director can thus avoid taking shots that won’t be used. Selznick was proud of William Cameron Menzies’ precise production planning on Gone with the Wind, and this made him believe in the power of the storyboard. When he rewrote a script, which was often, he was inclined to have artists immediately prepare fresh drawings of sets and shots.

Hitchcock had promoted himself as someone who drafted a film on paper so thoroughly that shooting became efficient and predictable. Selznick was therefore startled when Hitchcock proposed a long shooting schedule for Rebecca. “In view of the many speeches he has made to me about how he pre-cuts a script, so as to shoot only necessary angles, it is a mystery to me as to how he could spend even 42 days.”

During shooting, DOS became furious with the pace of production, declaring Hitchcock “the slowest director we have had.” Hitchcock, he believed, was spending more time getting his few angles than directors who shot in normal fashion. Yet Selznick remained susceptible to the dream of pre-cutting. Some years later, he predicted that Since You Went Away wouldn’t take much time in the editing room because the scenes “will be camera-cut to an extra-ordinary degree, and putting it together should take no time at all.” The film’s editing occupied several months.

Selznick, then, was attracted to current trends of longish takes and the fluid camera, but like nearly all his peers he saw these as subordinate to the overarching demands of analytical editing, whether through traditional protection coverage or through “pre-cutting.” Something similar seems to have governed his interest in depth staging and deep-focus cinematography. Peppered throughout the memos I examined are his concern for “foreground pieces,” props that can enliven a shot. A miniature sailing ship in Portrait of Jennie, he suggests, is too big for its placement in the shots as taken. “It would have been a far better foreground piece for another angle.” So it became such a piece, as the still surmounting this section indicates.

Of Since You Went Away DOS notes:

I think that lately we have been overlooking chances for good foreground and background planes in our set-ups. I don’t want to over-do this but of a lot of our shots could be much more interesting in this regard.

In particular he emphasizes the bronzed baby shoes introduced in the film’s opening, as the camera glides through the Hilton family parlor picking up traces of the departed father. A later scene, in which Anne writes a letter to her husband Tim, seemed the ideal chance to re-use that prop. “Photographically, I thought it would be much more interesting with the shadow of the shoes, or using the shoes as foreground pieces.” This composition, if it was shot, didn’t appear in the final film, but it shows once again that filmmakers can be aware of broader trends of their period, and that they’re willing to go to considerable trouble to join them.

A striking example of the insistence on participating in the deep-focus trend appears in the files around Spellbound. After arriving in America, Hitchcock occasionally produced some big-foreground depth images, as below in Shadow of a Doubt (1943), and in Notorious (1946).

Such compositions were rare in most films Hitchcock did under Selznick, but in Spellbound Selznick realized the value of keeping up-to-date. The most famous big foreground in the film (and in all Hitch’s work) is seen at the climax, when Dr. Murchison trains his revolver on Constance as she edges out of his office.

This bizarre shot is somewhat anticipated by a less aggressive setup. Constance hears over the radio that the police have tracked J. B. to Manhattan, and she goes into the next room to pack to follow him. The action is handled in a canonical post-Kane composition.

The production records make me wonder whether this shot (presumably using a larger-than-life clock and radio) was filmed under Hitchcock’s supervision. It may have replaced an even more complex shot that cinematographer George Barnes objected to. (I’m still gathering information on this.) In any event, Selznick realized that a minor transitional scene could be dynamized by a flamboyant, difficult-to-achieve image: a throwaway mark of quality.

Pendulum swings of innovation

Since You Went Away.

I’ll save other things I found for future work. Let me finish by talking about how Selznick’s “directing at a distance” shows a craftsman’s concern for novelty and pictorial storytelling.

Hitchcock famously shot the Old Bailey scenes of The Paradine Case with several cameras in an immense set. Selznick may have okayed this tactic on this occasion because it would speed up Hitchcock’s schedule. (Selznick had hoped it would take only one day; it took three for principal photography and several more for pick-up inserts.) But both before and after Paradine, Selznick was interested in extending multiple-camera shooting beyond its normal uses.

Multiple-camera coverage of ordinary scenes had a heyday in the early years of sound, but afterward it was usually reserved for unrepeatable action (fires, stunts, cars going off cliffs) or very big scenes. Selznick had deployed several cameras, including the lightweight Eyemos, during the dance at the airplane hangar in Since You Went Away. Like Welles, he also considered using the tactic for ordinary dramatic scenes. He writes in 1947:

I have long felt that sooner or later, probably when economic necessity dictates, this method of shooting will come into vogue, with far more time spent on rehearsal, far less time on shooting, enormous savings and better quality. I know that for years I have been discussing with Hitchcock my feeling that we could take a film of a particular type, thoroughly rehearse it, and shoot it in a week–and this is just what Hitch is planning to do on The Rope [sic].

Selznick anticipated the practice of multiple-camera television production. It’s intriguing to think of Hitchcock taking this idea and simply substituting one camera for many, creating another technical stunt that could be publicized.

DOS was sensitive to conventions and often sought to refresh them. For one back-projected scene of Portrait of Jennie, he advises Dieterle “to avoid the awful-looking, head-on, two-shot process setups and angle camera in different ways: perhaps with lower cameras, one shooting across Adams at Spinney and the other shooting across Spinney at Adams.” This echoes his concern for finding unusual angles on the process arrangement in Since You Went Away‘s driving scene. He likewise encouraged unusual staging, recalling

the love scene between Freddie March and Janet Gaynor in A Star Is Born, the one in which he takes her home the first night, after the kitchen scene, where the entire scene is played on Freddie’s back; and the love scene in Nothing Sacred in the crate after Carole Lombard has fished Freddie March out of the river. Both of these treatments enormously enhanced the value of these scenes, which shot conventionally would not have been necessarily so effective.

In the first instance, the conversation is handled by an unusually prolonged over-the-shoulder shot that doesn’t show March replying to Gaynor. In the second, the romantic dialogue is emphasized by the darkness of the crate and our inability to see either actor clearly.

Yet Selznick worried about becoming too “arty” as well. During the filming of Since You Went Away he confessed:

I feel that I am at least partially responsible for our increasing tendency to play scenes on people’s backs. . . . In Jane’s attack upon the colonel after the breakfast scene, we are on neither one principal nor the other, but on the colonel’s back and Jane’s back . . . In the church scene there has been talk of playing it on the three backs, but I have tried in the script to indicate that we should not do this.

Stark lighting is of course common in 1940s cinema generally, but Selznick favored it in the 1930s as well, in the shots above and more famously in Gone with the Wind. By the 1940s, Since You Went Away and Portrait of Jennie include scenes steeped in rich shadow areas, cast shadows, and silhouettes.

But here, as elsewhere, DOS’s urge for innovation was curbed by anxiety about going too far. In a memo to Cromwell on Since You Went Away, he wrote that “all of us (mostly myself) are overdoing the silhouette business. . . . Let’s from now on all use this silhouette effect very sparingly, and only when it’s absolutely indispensable to our mood.”

Perhaps what I’ve called his middle-of-the road approach was less a balance and more of a pendulum swing between extremes. He could sometimes foreswear the grand, almost monumental look of many scenes and demand something quieter. At the end of the day when Anne’s husband has left for war, she looks at his unmade bed.

She leaps up and wriggles into it, covering her face with the blankets, and starts to cry.

Commentators often fasten on the twin-beds convention as an example of the naive timidity of studio-era Hollywood. Yet every convention offers opportunities for expression. When Anne rises, the sight of one rumpled bed and one pristine one brings home the husband’s absence in a simple, powerful image, and her plunging into it directly conveys her longing to be in his arms.

I’m absolutely positive that this gag will not get over unless we see the two beds in the clear, one made up and one not made up, before she hops into the other bed. I think these two beds constitute good storytelling.

When the hard-bitten Ben Hecht saw Since You Went Away, he cabled Selznick: “It made me cry like a fool.”

You can certainly argue that Selznick the fussbudget was his own worst enemy. His micromanagement raised his budgets and drove away his collaborators. As the production values grew more inflated, it was hard to recoup costs, let alone turn big profits. Ten years after Gone with the Wind premiered, Selznick’s fiefdom lay in ruins. He withdrew from production, millions of dollars in debt. He wrote in a confidential 1948 memo:

In the final analysis it is my fault for two reasons: (1) my production methods; (2) my tolerance through the years of the wastefulness. . . . The most successful series of pictures ever made in the history of the business has produced profits which are perhaps not more than twenty per cent of what they should be.

Ideas matter in any domain, even in studying Hollywood. And not just the ideas of critics, historians, and theorists. The practicing artisans of the studio system had rich ideas about preferred ways to build plots, to shoot and cut scenes, to mix sound and add music. These norms were seldom stated outright. Were Selznick less interfering, less prone to hesitate between alternatives, less obsessed with minute details, we would not know as much about the workings of the system he sought to rule. He distilled into typescript and double carbons many notions that ordinarily went unstated. His plump files teem with ideas about how films were made, and how their creator thought they should affect audiences. Thanks to institutions like the Ransom Center, his work is preserved to enlighten us about filmmakers’ secrets, even the secrets they don’t know they know.

I’m very grateful to Emilio Banda and the rest of the staff at the Harry Ransom Center, who helped me during my visit. Thanks also to Steve Wilson, Curator of Film there, for advice. And of course thanks to my family–Diane, Darlene, Kewal, Kamini, Megan, and Sanjeev–who made our trip to Austin so enjoyable.

My quotations come from the memos I examined, as well as from other items in Rudy Behlmer’s Memo from David O. Selznick. I also drew on Ronald Haver’s David O. Selznick’s Hollywood (Knopf, 1980), the initial edition of which is surely the most gorgeous book ever published about the American film industry. Haver’s study is not only spectacularly illustrated but deeply researched, and it, like Behlmer’s, is indispensable for the study of the studio system. The Menzies production sketch is taken from the Haver volume.

No less indispensable is Leonard J. Leff’s Hitchcock & Selznick (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987). After sifting through both the Selznick collection in Austin and the Hitchcock collection at the Academy’s Margaret Herrick Library, Leff produced a detailed account of the two men’s creative work. Hitchcock’s long take in The Paradine Case is promoted in Bart Sheridan, “Three and a Half Minute Take…,” American Cinematographer 27, 9 (September 1948), 304-305, 314.

Paul Ramaeker offers a subtle account of Portrait of Jennie as a “supernatural romantic melodrama” at The Third Meaning.

For more on 1940s stylistic norms, see The Classical Hollywood Cinema, chapter 27, and On the History of Film Style, chapter 6. The first essay in my Poetics of Cinema discusses Hitchcock in relation to trends of the period, concentrating on Rope and long-take options. On Citizen Kane and rationales for deep-focus cinematography, you can go here. I mention a bit about the fashion for the “fluid camera” in 1940s Hollywood in this entry.

William Cameron Menzies served as art director and more for Gone with the Wind, and he and was pressed into service ad hoc for later DOS projects. I think he may have influenced the shadow-drenched style of Since You Went Away and Portrait of Jennie. I wrote about Menzies’ work, and again about deep-space work in 1940s Hollywood, here and here. See also David Cairns’ enlightening essay in The Believer.

Since You Went Away: “I think that Miss Keon had better start preparing a script of retakes and additional scenes. I think we missed a wonderful opportunity in the Christmas scene in not having a shot from the angle of the family, or from the bottom of the stairs, of the Colonel going up the stars with Soda behind him.”

You the filmmaker: Control, choice, and constraint

DB here:

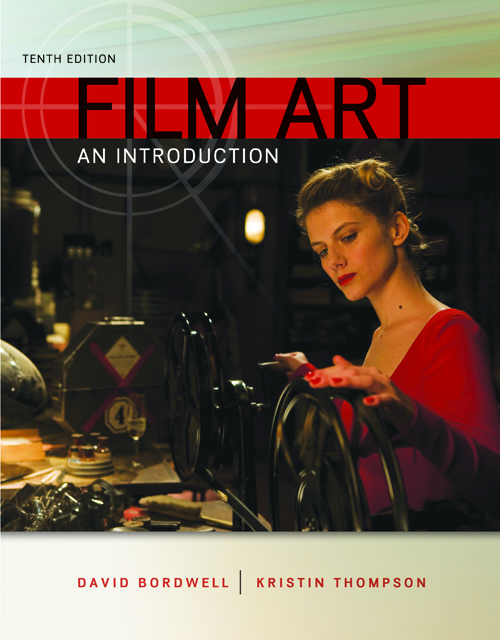

The tenth edition of our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction will be available in early July. It has so many new features that it’s our most extensive revision in at least a decade.

Kristin has already written about one of our major additions: supplemental film extracts from the Criterion Collection, with voice-over commentary and other sorts of analysis. (Go here for a sample.) These will be accessible to professors for incorporation into their syllabi. More of them may also become generally available on the Criterion website.

The text has been extensively rewritten, aiming at maximal clarity and freshness. There are many local changes too, with updated examples from a variety of films both old and new. Regular readers will notice that we have made two replacements: Koyaanisqatsi is now our example of associational form, and Švankmajer’s Dimensions of Dialogue is our example of experimental animation. Regretfully, we had to drop our earlier examples, Bruce Conner’s A Movie and Robert Breer’s Fuji, because they are available only in 16mm, and most teachers and readers don’t have access to them. On the other hand, we enjoyed analyzing the new items and think that they serve their purpose very well.

Today I’m going to point out some of the broader changes, while also considering the book’s overall approach.

Parts and wholes

When Film Art appeared in 1979, it was the first textbook in English written by people who had received Ph.D.s in film studies. Specifically, FA emerged from my teaching a lecture-and-discussion course called “Introduction to Film” to several hundred students each semester for many years.

In the mid-seventies, there were almost no film studies textbooks, and none of them seemed to us to reflect the directions of current research. As a result, the first edition of FA included topics that were emerging in the field, such as narrative theory and conceptions of ideology. It also suggested a coherent, comprehensive view of cinematic art, from avant-garde and documentary cinema to mainstream film and “art cinema.”

The book has changed since then, but its approach has remained consistent in two primary respects. For one thing, it tries to survey the basic techniques of the medium in a systematic fashion. Here the key word is “systematic.” It seemed to us that we might go beyond simple mentioning this or that technique—editing, or acting, or sound—and instead treat each technique in a more logical and thorough way. But film aesthetics wasn’t yet conceived in this way, so to a considerable extent the textbook had to offer some original ideas.

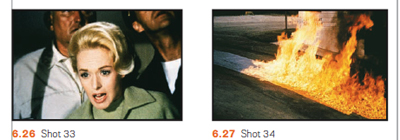

For example, most people thought of editing primarily as a means of advancing the film’s story. That’s certainly accurate up to a point, but we tried to go up a level of abstraction. We suggested that the change from shot to shot had implications for what was represented (the space shown in the shots, the time of the action presented), as well as for the sheer graphic and rhythmic qualities onscreen, independent of what was shown. That created four dimensions that the filmmaker could control, and we illustrated how Hitchcock shaped all of them in a sequence from The Birds.

Nobody before had surveyed editing’s possibilities in this multidimensional way. The result was that we were able to trace out several expressive options. We analyzed the 180-degree system for presenting story space, and Film Art became the first film appreciation textbook to explain this. We also laid out ways in which shots could manipulate the order, duration, and frequency of story action. We also considered sheerly graphic and rhythmic possibilities of editing, not all of which are tied to narrative purposes. Similarly, we tried to show that sound, another familiar technique, could be understood as a bundle of systematic options relating to sound quality, locations in space, relation to time, and other factors.

In sum, very often the array technical options had an inner logic. This urge to cover all bases helped us notice options that usually escaped critics. So by concentrating on the graphic dimension of editing, we noticed that some filmmakers tried to create pictorial carryovers from shot to shot, a device we called the “graphic match.”

A second core principle of the book was the idea that we ought to think about films as wholes. There’s a strong tendency in film criticism, in both print and the net, to fasten on memorable single sequences for study. There’s nothing wrong with this, of course, but we think it needs to be balanced by considering how all the sequences in a film fit together. That led us to consider various types of large-scale form, both narrative and non-narrative.

Again, this was new to the field. We showed students how to divide films into parts and then trace patterns of progression and coherence across them. This is a valuable skill for both intelligent viewers and people who might want to work in filmmaking. We showed how the distinction between story and plot could help explain large-scale narrative construction. We suggested that issues of point-of-view and range of character knowledge exemplified broader principles of narration, the ways films pass information along on a moment-by-moment basis. And although most film courses show narrative films (mine did too), we wanted students to think about other large-scale organizational principles too, such as rhetorical argument and associational form. Again, thinking about these more general possibilities led us to consider creative options that hadn’t been the province of introductory texts, such as rhetorical documentary and poetic experimental cinema.

These two efforts—comprehensive study of techniques and a holistic emphasis on total form—weren’t FA’s only salient points. We tried to incorporate more familiar elements from genre studies and historical research. But they did set the book apart, and do still. I believe that we made contributions to our understanding of film aesthetics. One measure of these contributions is the extent to which FA has been regarded as not only a textbook but an original contribution to film aesthetics. Another sign is the fact that other textbooks have relied, sometimes to a startling degree, upon FA for concepts, organization, and examples.

Categories, categories

Associational form: Koyaanisqatsi.

Still, we did encounter objections.

Some readers worried that FA’s layout of logical categories took away some of the magic and mystery: Art dies under dissection. Some also protested that filmmakers didn’t use the categories and terms we invoked. These concerns have, I think, waned a bit over the years, but I’ll address them anyhow.

First, as to the need for categories. As a genre, the textbook in art theory has a very old ancestry. Aristotle’s Poetics, a survey of what we’d now call literary art, bristles with categories—drama vs. epic, comedy vs. tragedy, types of plots, etc. In the visual and musical arts, from the Middle Ages into the Renaissance, writers tried to systematically understand the principles of artists’ practice. Leon Battista Alberti’s treatise on painting tried to show that as an activity, painting had many “parts,” such as drawing, color, and light.

This classificatory urge continued through the centuries, and it continues today. Pick up a book on the visual arts today and you’ll see chapters on composition, color, texture, and the like. The same goes for music; an introductory book will survey rhythm, harmony, melody, musical forms, and so on. There’s no escaping some sort of categorizing if we want to understand any subject, and this goes as well for art traditions.

The categories governing centuries-old arts are largely taken for granted. But film is a newish medium, and film studies a still-young academic discipline, so there remains a lot of exploratory thinking to be done. In the late 1970s, Film Art undertook some of that exploration.

A lot of thinking about film employs categories that are very abstract and general (say, “realism” versus “non-realism”). Our frame of reference tries to be more concrete, more fitted to the particularity of what films actually look and sound like. Whenever we could, we incorporated filmmakers’ explicit concepts into our analyses. FA, for instance, was the first appreciation textbook to introduce the principles of continuity editing that were craft routines among directors and cinematographers.

At other times, we tried to synthesize ideas that were circulating in the filmmaking community. For example, for several decades filmmakers and critics have been saying that editing is getting faster, close-ups are getting more prominent, and camera movements are becoming more salient, even aggressive. From studying hundreds of films, we came to the conclusion that these trends are part of a new approach to film style, and we dubbed that “intensified continuity.” That term aims to capture the idea that for the most part these techniques are in accord with traditional continuity editing, but they sharpen and heighten its effect.

Occasionally we tried to clarify concepts. Most notoriously, we borrowed from French film theory the distinction between “diegetic” and “nondiegetic” sound because all the other terms (“source music,” “narrative music,” etc.) seemed to us ambiguous or inexact. As with most categories, individual films can play with or override this distinction, but it’s a plausible point of departure because traditionally the distinction is respected.

Contrary to some objections, then, we often worked with ideas used by practicing filmmakers. Where traditional terminology seemed inadequate to those ideas, we created our own. And some effects we may notice in movies may have no currently accepted names. In some cases, as in the graphic match, the phenomenon may not even have been identified. We haven’t tried to conjure up fancy labels; we’ve just tried to point to the ways some films work. Anyhow, the term doesn’t matter much, but the concept does.

So one way to think about the categories of form and style in FA is to see them as bringing out principles underlying filmmakers’ practical decisions. A director may choose to do something on the basis of intuition, but we can backtrack and reconstruct the choice situation she faced. If we want to survey the possibilities of the medium, one way to do it is to build categories that show the expressive options available, even if filmmakers don’t sit down and brood on each one.

Thinking like a filmmaker

Walt Disney’s Taxi Driver (Bryan Boyce).

Categories are inevitable, and they allow us to consider creative choices systematically. Making this second point explicit is the most important overall revision in the new version of Film Art.

Previous editions took the perspective of the film viewer. This is reasonable: Teachers want to enhance their students’ skills in noticing and appreciating things in the movies. But from the start FA also indicated that the things we discussed also mattered to filmmakers. As the years went by, we incorporated more comments and ideas from screenwriters, cinematographers, sound designers, directors, and other artisans—often as marginal quotes that, we hoped, would reinforce or counter something in the main text.

Now, though, we’ve shifted the perspective more strongly toward the filmmaker—or rather, toward getting the viewer to think like a filmmaker.

Until recently, most of our readers hadn’t tried their hand at making movies. But with the rise of digital media, a great many young people have begun making their own films. Some of these are variants of home movies, records of concerts or parties or a night out. But many of these DIY films are more thoroughly worked over. They’re planned, shot, and cut with considerable care. Posted on YouTube or Vimeo, they exist as creative efforts in cinema no less than the films that get released to theatres or TV. If you doubt it, look at lipdubs, or meticulous mashups like Bryan Boyce’s.

So, we thought, many students are now able to consider film art as practicing filmmakers. For one thing, that means they’re more aware of the techniques we explain. (Probably nothing in Film Art is as tough as mastering Final Cut Pro.) Moreover, the very act of making films has made students sensitive to alternative ways of doing anything. Accordingly, this edition emphasizes that the resources of the film medium that we survey constitute potential creative choices which yield different effects.

Take an example. We can explain the idea of restricted versus unrestricted narration abstractly. Restricted narration ties you to a limited range of knowledge about the story action; unrestricted narration expands that range, often presenting action that no single character could know about. Filmmakers intuitively make choices along this spectrum even if they don’t use the terminology. Then again, sometimes they do. A while back we quoted the director of Cloverfield:

The point of view was so restricted, it felt really fresh. It was one of the things that attracted me [to this project]. You are with this group of people and then this event happens and they do their best to understand it and survive it, and that’s all they know.

In Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus, the hero and three other captives are chosen to fight in the arena. They sit sealed in the holding pen while we hear Crassus and his elite colleagues chatting pleasantly about their trivial affairs.

When the combat starts, we’re still confined to the shed. Crixus and Galeno are summoned out, and the door slides shut, leaving Spartacus and Draba alone.

The director has already made several important choices, notably contrasting the carefree chatter of the rulers with the grim prospects of the gladiators (the latter underscored by relentless music). But now there’s a big fork in the road: To show the first combat, or not?

Kubrick chooses not to. We hear the call, “Those who are about to die salute you!” We hear swords clashing, and Spartacus peers outside through the slats. We see only what he sees.

Draba studies Spartacus, who closes his eyes to shut out the spectacle outside.

The two men share a look, but Spartacus turns his gaze away, as if unwilling to confront the cost of killing this man who has done him no harm.

This stretch of the scene is too detailed and varied for me to replay in full, but it’s all confined to the two men in the shed—their reactions to what they hear and what Spartacus sees, and the development of a mix of wary appraisal and desperation. No words are spoken.

The fight outside concludes, and at the climactic moment Kubrick cuts to a new angle that puts Draba and Spartacus in the same frame, realizing that their time has come. The door slides open again, and the men step out.

The exchange of glances has been just ambiguous enough to make us wonder whether the two will really try to kill one another. Restricting us to the holding pen gives us a moment to watch them pondering their fates and enhances the suspense about the outcome of their fight.

Every instant presents the director with a choice that can shape the viewer’s experience. When the men go out, Kubrick must decide on what to show us next. Most daringly, he could keep us in the shed and let us glimpse the fight from there. But that would be a very unusual option in American commercial cinema. Instead, the next shots expand our range of knowledge by shifting us to a different character’s reaction. Before showing us the arena, we get a shot of Virinia, the slave just bought by Crassus. As a result, she is marked as important before we get a general shot of the arena.

Eventally, a master shot ties together all the characters before we move to the next phase of the scene.

As Darba and Spartacus start their fight, you can argue that the effect of it is even stronger because we haven’t seen the earlier match. Restricted presentation of the first combat, seen only through Spartacus’s eyes, throws the emphasis on this one.

By shifting our attention to filmmakers’ areas of choice, we haven’t really abandoned thinking from the standpoint of the spectator. The two views complement each other. In effect, we’re reverse-engineering: thinking like a filmmaker sharpens our sense of how the spectator’s experience can be shaped. From either perspective, we need concepts, categories, and terminology.

To futz or not to futz?

Undercover Man (1949).

Once we notice the concrete results of creative choices by director, cinematographer, editor, and others, we’re inclined to compare how filmmakers have pursued different options, and how these decisions yield different effects. So you might contrast Kubrick’s treatment of the combat with the free-for-all in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator. There the period of waiting is short, and all the emphasis is put on the bloody combat.

Film Art uses the comparative method often, again to illustrate the range of choice available to the filmmaker. Let’s take some instances that have implications for both narration and sound. Telephone conversations are a staple of filmic storytelling. In such a scene, you as a director face a decision tree. Whatever you choose leads to other choices.

Should you show both characters in the conversation, or only one? A passage from The Big Clock presents both options, one after the other.

This illustration suggests that if the character on the other line plays a significant role in the story, you may want to show him or her. Max isn’t as important as Stroud’s wife and son. Once you’ve decided to cut back and forth, you’ll still have to decide when to cut—at what points to show us characters’ reactions. You might want to replay this clip to see how the cutting pattern highlights certain responses.

Alternatively, you can stick with one character and conceal the other party, even if that character is important. Here’s an example from Joseph H. Lewis’s Undercover Man.

Unlike Max in the Big Clock scene, this caller is an important character, a prospective snitch. By not showing him on the other end of the line, Lewis concentrates our attention on the federal agents and builds a little suspense. He goes even further: By not cutting in to Warren as he talks, the direction emphasizes the reactions of Judy, Warren’s wife. Her response is highlighted when she turns slightly into profile, registering her realization that her husband has to leave her on a dangerous mission sooner than she expected.

Sticking with one character triggers another choice about telephone talk: Do you let us hear the other party or not? So far, all our examples have suppressed the voice of the person on the other end of the line. But of course you could let the viewer hear that.

There’s a new problem coming up, though. You need to make it clear that the voice is coming through the receiver, not from someone outside the frame. So a convention has arisen: Words coming through the phone line are distorted, in a process called “futzing.” Here’s an example of subdued futzing from I Walk Alone.

And here’s a case from The Blue Dahlia illustrating the difference between the two sorts of sound even more sharply. Here it’s especially important to let the audience know that what’s being heard is a recording.

This isn’t to say that every choice is absolutely fixed. You can experiment. This is what King Vidor did in H. M. Pulham, Esq. Pulham gets a call, and though we stay with him, the voice isn’t futzed; the effect is a bit unnerving.

Vidor explains:

We were breaking with tradition. When the sound men took over, it became the cliché to put all telephone voices through some sort of filtering device. This made it sound distorted and weird. It occurred to me, why should the audience strain to listen? The person with the receiver up there on the screen doesn’t strain to hear the voice. There isn’t any kind of mechanical distortion. I thought we should just direct it to sound the way it sounded to the person.

The film’s plot concerns Pulham’s regrets about the missed opportunities of his youth. When he gets calls from old friends, their voices seem unusually immediate, more vital and “present” for him than the people in the life he’s leading now.

These creative options show how even small stylistic decisions affect narration and the viewer’s response. Presenting both characters on the phone creates more unrestricted narration, and this allows us to gauge reactions to the action. By showing only one character, you concentrate on that person and the people around them.

If you suppress the words spoken on the other end of the line, you maintain some uncertainty about what’s happening, and you don’t share with us what the listener knows. In contrast, if you let us hear what the listener hears, you tie us to their range of knowledge and perhaps create a bond with them. And as Vidor suggests, you can try to create a deeper subjectivity by letting us hear the speaker as the listener does.

Although Vidor’s experiment wasn’t taken up, directors have continued to try different ways of rendering phone conversations. It would be fun to compare Larry Cohen’s two “phone” scripts, Cellular and Phone Booth, in these terms—not least because of the eerie sound design applied to the mysterious caller harassing the hero of Phone Booth.

Choice and change in history

Un Chien andalou (1928); Blue Velvet (1986).

In such ways, the categories we survey can be thought of as a range of possible options facing filmmakers. But all of them aren’t available to every filmmaker. As every filmmaker knows, you choose within constraints, and some of those constraints are the result of history.

As in earlier editions, Film Art concludes with a chapter surveying artistic trends across film history. But now we’ve tried to integrate the idea of thinking like a filmmaker into that section, emphasizing the interplay of choice and constraint. Most obviously, budgets limit choices. Other constraints might be technological; not all filmmakers have been able to film in color, or to use advanced special effects. Some constraints involve matters of fashion: some acting styles and staging methods aren’t widely acceptable today. In our final chapter we show how certain traditions and schools of filmmaking confronted the constraints of their period and place. Sometimes filmmakers worked within those constraints, and sometimes they overcame them by trying something different.

At the same time, we break with our previous editions by weaving recent films into the history chapter. We try to show that the expressive choices made by filmmakers long ago have returned in our time. The earliest short films, based on novelty and surprise events, have successors in YouTube videos. Contemporary filmmakers draw on techniques favored by German Expressionism and French Impressionism. (Recent examples on the blog are here and here.) Current Iranian films owe a good deal to Italian Neorealism, while the Dogme filmmakers tried to revive some of the insolent force of the French New Wave. It isn’t just a matter of influence, either. Contemporary filmmakers face problems of storytelling and style that others have faced before. The choices our filmmakers make often recall those made in the past.

We’re very proud of this edition of Film Art. We hope that the changes will whet the interests of teachers, students, film lovers, and that generic “curious general reader”—who, we persist in believing, isn’t mythical.

Just to be clear: Our Spartacus example doesn’t appear in the book. Our layout of choices about handling phone conversations does, but with different examples. Thanks to Kevin Lee and Jim Emerson for advice on video embedding.

King Vidor’s remarks about H. M. Pulham, Esq. are taken from Nancy Dowd and David Shepard, King Vidor: A Directors Guild of America Oral History (Scarecrow, 1988), 188. A library of futzed sound clips is here. For a more detailed study of how phone conversations may be presented through both sound and image, see Michel Chion’s Film, A Sound Art, trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 365-371. (An outline of his typology is here, in French.) Chion’s research is a good example of showing how a systematic set of principles can underlie the practical decisions facing filmmakers.

Alert reader Chris Freitag has steered me to a recent and fine lipdub here. It exemplifies how competition within a genre can spur innovation. More specifically, how to create a new sort of lipdub? Well, how about proposing marriage?

Instructors interested in obtaining a desk copy of Film Art: An Introduction can visit this website.

Dimensions of Dialogue (1982).

P.S. 27 June: Some correspondence I’ve just gotten reminds me of two things I neglected to mention in the entry. First, this edition of Film Art contains a great deal more material on digital cinema, from production and postproduction through to distribution and exhibition. We’ve woven digital technology into sections on various techniques, particularly cinematography, and we’ve added material on 3D cinema.

Second, our decision to replace our sections on A Movie and Fuji doesn’t mean that those discussions will vanish forever. For some years we’ve been putting up older Film Art material as pdf files on this wing of the site. Later this summer we’ll be doing the same with the Movie and Fuji sections of the book. Instructors who want their students to read that material are welcome to send them there, where the essays can be downloaded.

I Love a Mystery: Extra-credit reading

Thornton Utz illustration for Rex Stout novella from American Magazine, 1951. Obtained from the excellent site Today’s Inspiration.

DB here:

Over the next few months, I’ll be traveling with a talk on Hollywood cinema of the 1940s. The ideas I’ll propose are destined for a book about narrative norms during that period. Mystery fiction is important to that lecture, but I don’t have room there to supply much background about the relevant conventions. So I’m sketching in this background here, for people who might hear the talk somewhere or who might just be curious. Consider this as another experiment on the blog, using the web to supplement a lecture.

Although the lecture is mostly about cinema, this entry is mostly about novels and plays. But I’ll mention film here and there, and you’ll notice that some of the books and plays I mention were adapted for the screen.

A mega-genre

The first half of the twentieth century saw an explosive expansion in genres built around mystery and suspense. The most obvious genre is the detective story. In the wake of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes tales, a great many writers developed and elaborated on the idea of the master sleuth, the genius of observation and reason. Central to this tradition was the puzzle that could be solved by careful noting of clues and meticulous reasoning about them, supplemented by a good knowledge of human nature or local customs. The author needs to keep us in the dark about both the crime and the detective’s chain of reasoning; hence point-of-view figures like Watson, who can be appropriately confounded, relay the detective’s cryptic hints, and marvel at the final revelations.

Readers quickly learned the conventions, so writers had to innovate constantly. Sometimes a writer was original on more than one front. For example, R. Austin Freeman created a revamped Holmes surrogate in a scientific criminologist, Dr. Thorndyke, while also creating a new narrative structure: that of the “inverted” tale. The first section of the story follows the criminal who commits the crime; the second part details how Thorndyke, using evidence and inference, solves it.

Historians of the detective story have a standard account that goes like this. The puzzle-centered plot developed to its apogee in the 1920s and 1930s, chiefly in Britain, and was picked up in the United States. In books like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (Agatha Christie, 1926), The Canary Murder Case (S. S. Van Dine, 1927), The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (Dorothy L. Sayers, 1928), The Poisoned Chocolates Case (Anthony Berkeley, 1929), The Egyptian Cross Mystery (Ellery Queen, 1932), and The Crooked Hinge (John Dickson Carr, 1938), the crimes are deeply puzzling, even fantastical, and the solutions ever more recherché.

Historians of the detective story have a standard account that goes like this. The puzzle-centered plot developed to its apogee in the 1920s and 1930s, chiefly in Britain, and was picked up in the United States. In books like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (Agatha Christie, 1926), The Canary Murder Case (S. S. Van Dine, 1927), The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (Dorothy L. Sayers, 1928), The Poisoned Chocolates Case (Anthony Berkeley, 1929), The Egyptian Cross Mystery (Ellery Queen, 1932), and The Crooked Hinge (John Dickson Carr, 1938), the crimes are deeply puzzling, even fantastical, and the solutions ever more recherché.

It’s hard for us to conceive today how massively popular these puzzle books were. Van Dine’s first novels were bestsellers comparable to Jonathan Kellerman’s books today. Just as important, the detective story was granted quasi-literary status. Magazines and newspapers that wouldn’t dream of reviewing romance or adventure fiction devoted space to detective stories, sometimes even setting up separate columns or sections for reviews. It was believed, rightly or wrongly, that whodunits had a more intellectual readership than Westerns or science fiction.

At about the same time, according to the standard account, a counter-current was swelling. In the pulp magazines of the 1920s, the “hard-boiled” detective emerged as an alternative to the master sleuth. The prototype is Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op in stories through the late 1920s, to be followed by Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1930). Strikingly, Hammett and other hard-boiled writers don’t wholly abandon the basic idea of solving a mystery through some sort of reasoning. The differences have to do with realism. The crimes, however, aren’t usually fantastical ones like the Locked-Room problem; the killings tend to be mundane. If the white-glove detective’s only real opponent is a master criminal like Professor Moriarty, the hard-boiled detective faces off against organized crime, or at least people who commit murder outside upper-crust parlors and remote country houses. Clues are less likely to be physical, and more psychological, depending on bits of behavior or flashes of temperament. Raymond Chandler and others took the hard-boiled initiative into the 1940s, and the brute detective, who solves crimes with boldness, insolence, and a pair of fists, occasionally supplemented by torture, found bestseller status in Mickey Spillane’s I, the Jury (1947) and subsequent novels.

I’d argue that some writers could blend the master-mind detective and the tough guy. Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason was one such hybrid, though leaning closer to the hard-boiled model. Rex Stout solved the problem neatly by creating two detectives: the insolent legman Archie Goodwin serves as a hard-boiled Watson to sedentary Nero Wolfe. But on the whole, historians tend to assume that the Holmesian superman and the puzzle-dominated plot were swept aside by the rise of the tough-guy detective solving mysteries that were grittier and more “realistic” than what had preoccupied Golden Age writers.

Two other major developments are typically highlighted by historians. There was the police procedural, perhaps initiated by Lawrence Treat’s V as in Victim (1945), and explored with great ingenuity in the novels of Ed McBain. There was also what Julian Symons has called the “crime novel,” the story of psychological suspense, with Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers on a Train (1950) serving as a good example. Both of these genres have proven popular to this day (CSI as a procedural, the films of De Palma as psychological thrillers).

A tree and its branches

Like most histories hovering fairly far above the ground, the standard account traces some main contours of the landscape but misses some interesting byways. By taking Doyle as the prototype, this account tends to identify mystery fiction with detective plots in the Holmes mold. But mysteries come up in other forms.

The standard account has trouble accommodating the development of the spy genre, which often involves solving a crime, but less through abstract reasoning than by putting the hero through hairbreadth adventures. Think for instance of The 39 Steps, both the 1915 novel and the 1935 film.

More seriously, by identifying solving mysteries with the activities of professional, overwhelmingly male, detectives historians have neglected the powerful and popular tradition of the revived Gothic or “sensation” novel of the mid-nineteenth century. This is typified by Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White (1859-1860) as much as by The Moonstone (1868), often considered the first detective novel (largely because a detective figures as one of the characters, even though he doesn’t solve the mystery). Collins’ novels, along with those of Mary E. Braddock, updated the Gothic format through more complex plotting and multiple points of view. In the next century, Mary Roberts Rinehart, with The Circular Staircase (1908), has to be considered as important as Freeman. Rinehart’s plot introduces the crucial conventions of the mysterious house, the curious and brave woman who explores it, and the threats lurking behind placid domesticity. While the classic white-glove sleuth isn’t usually in much danger, The Circular Staircase and other updated sensation novels make the investigating figure a woman in peril. The sensation novel replaces cool rationality with fear and desperation.

More seriously, by identifying solving mysteries with the activities of professional, overwhelmingly male, detectives historians have neglected the powerful and popular tradition of the revived Gothic or “sensation” novel of the mid-nineteenth century. This is typified by Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White (1859-1860) as much as by The Moonstone (1868), often considered the first detective novel (largely because a detective figures as one of the characters, even though he doesn’t solve the mystery). Collins’ novels, along with those of Mary E. Braddock, updated the Gothic format through more complex plotting and multiple points of view. In the next century, Mary Roberts Rinehart, with The Circular Staircase (1908), has to be considered as important as Freeman. Rinehart’s plot introduces the crucial conventions of the mysterious house, the curious and brave woman who explores it, and the threats lurking behind placid domesticity. While the classic white-glove sleuth isn’t usually in much danger, The Circular Staircase and other updated sensation novels make the investigating figure a woman in peril. The sensation novel replaces cool rationality with fear and desperation.

Jane Eyre is an obvious source for Rinehart and her successors, and perhaps the association with women’s writing in general made historians and practitioners of the Golden Age mock the revived Gothic as too feminine, too far removed from the bluff masculine camaraderie of 221 B Baker Street. The Gothicists had their revenge: Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938) outsold every other mystery novel of its time and sustained a cycle of new sensation novels by Mabel Seeley (The Chuckling Fingers, 1941), Charlotte Armstrong (The Chocolate Cobweb, 1948), and Hilda Lawrence (The Pavilion, 1946). The genre is maintained today by Mary Higgins Clark, Nicci French, and many other writers.

So mystery and detection formed a broader tradition than literary historians sometimes acknowledge. Another marginal form was the suspense thriller. Again, we can point to a woman: Marie Belloc Lowndes, author of The Lodger (1913). An early instance of the serial-killer plot, it’s also a tour de force of point-of-view; unlike the film versions, it restricts itself quite rigorously to what certain secondary characters know. Choices about narration and viewpoint are no less crucial to the thriller than to the Great Detective tradition.

The psychological thriller was revived during the Golden Age, sometimes by practitioners of the puzzle-story. Anthony Berkeley Cox, writing as Anthony Berkeley, noted in The Second Shot (1930):

The psychological thriller was revived during the Golden Age, sometimes by practitioners of the puzzle-story. Anthony Berkeley Cox, writing as Anthony Berkeley, noted in The Second Shot (1930):

I personally am convinced that the days of the old crime puzzle pure and simple, relying entirely upon plot, and without any added attractions of character, style, or even humour, are, if not numbered, at any rate in the hands of the auditors. . . The puzzle element will no doubt remain, but it will become a puzzle of character rather than apuzzle of time, place, motive, and opportunity. The question will be not “Who killed the old man in the bathroom?” but “What on earth induced X, of all people, to kill the old man in the bathroom?”

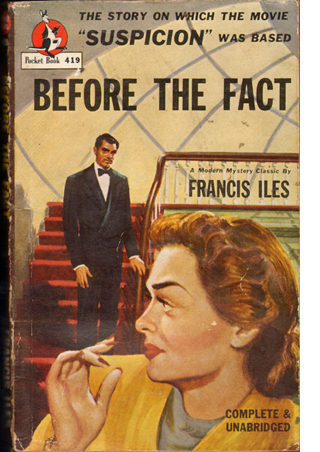

Cox went on to test his premises in Malice Aforethought (1931) and Before the Fact (1932). Both trace the schemes of wife-killers, but the first novel is told from the husband’s standpoint and the second from the wife’s. The latter book opens:

Some women give birth to murderers, some go to bed with them, and some marry them. Lina Aysgarth had lived with her husband for nearly eight years before she realized that she was married to a murderer.

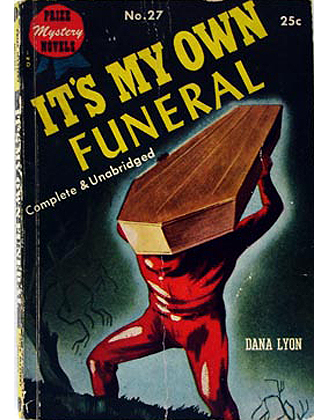

There followed other domestic-crime psychological novels, notably Richard Hull’s The Murder of My Aunt (1934).

Sometimes suspense thrillers have a solid mystery at their center; this is common when the protagonist is a potential victim. Other thriller plots in effect present the first half of a Freeman “inverted” story, concentrating on the criminal’s execution of a crime and the resulting efforts to escape punishment. Both possibilities were on display in British stage plays of the 1920s and 1930s. In a sense Cox was beaten to the punch by Rope (1929), Blackmail (1929), and Payment Deferred (1931). Later examples are Night Must Fall (1935) and the woman-in-peril dramas Kind Lady (1935) and Gaslight (1938). Many of these plays were made into films.

The novel of suspense really came into its own in the 1940s, when it started to incorporate abnormal psychology. Patrick Hamilton, author of Rope and Gaslight, provided an influential novel as well, Hangover Square (1941). Cornell Woolrich and David Goodis, who mined this nightmarish vein, achieved posthumous cult status because, again, of the spell of film noir. Other suspenseful students of mania were Dorothy B. Hughes (In a Lonely Place, 1947), Charlotte Armstrong (The Unsuspected, 1945; Mischief, 1951, filmed as Don’t Bother to Knock), and Elizabeth Sanxay Holding (The Blank Wall, 1947, source of The Reckless Moment). Chandler called Sanxay Holding “the top suspense writer of them all.” We shouldn’t ignore the influence of Simenon’s romans durs, which were being translated and respectfully reviewed throughout the war years.

Yet another new wrinkle on the mystery thriller was the genre of courtroom novels. The Bellamy Trial (1927), which begins when the trial does and restricts itself almost completely to what transpires in the courtroom, popularized the pattern. Stage plays of the 1920s adopted the pattern too. The format proved irresistible for early talkies, as in adaptations of The Bellamy Trial (1929) and Thru Different Eyes (1929) and the radio-inspired Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932). Cox, who seemed to try his hand at every current trend, gave his own twist to the juridical mystery in Trial and Error (1937).

Most of these novels focused on the trial proceedings from the perspective of the defendant, but a few concentrated on those sitting in judgment. The Jury (1935), by Gerald William Bullett, characterizes the jurors singly before they gather and then shows the trial from their standpoints before taking us into the jury room to hear the arguments. Bullett’s novel finds an equally engrossing complement in Raymond Postgate’s Verdict of Twelve (1940). There were also Eden Philpotts’ The Jury (1927) and George Goodchild and C. E. Bechhofer Roberts’ The Jury Disagree (1934). We can immediately recognize the teleplay and film Twelve Angry Men as an updating of this minor line.

Merging and markets

The family tree of mystery, then, grew many branches in the 1920s and 1930s—the pure puzzle, the hard-boiled investigation, the spy story, the revised Gothic or sensation novel, and the suspense thriller, often of a psychological cast. Unsurprisingly, the genres began to mingle. Cox was perhaps the writer most interested in hybrids, but John Dickson Carr tried his hand at the thriller as well (The Burning Court, 1937), as did Agatha Christie in And Then There Were None (aka Ten Little Indians, 1940).

The process sped up during the 1940s, when writers began blending crime-solving with psychological suspense. We can get a sense of how the protagonist-in-peril side of the thriller melded smoothly with the enigma-based investigation by looking at the jacket copy of a fairly ordinary entry, Alarum and Excursion (1944):

Bit by bit, a gesture here, a sound there, Nick Matheny pieced together the awesome puzzle of the accident that had sent him to a sanitarium with traumatic amnesia. One by one he reconstructs, he probes the cirumstances of the explosion in his factory, the disappearance of his weak but beloved son, his wife’s strange attitude toward the new management of the business, and the status of the new synthetic fuel formula, which was so urgently needed.

As the dreadful picture unfolds itself, Nick escapes from the sanitarium to ferret out the sinister changes that have disrupted his business and brought his active life to an abrupt close.

Virginia Perdue, author of He Fell Down Dead, skillfully handles the difficult flash backs in this unusual psychological drama. There are many scenes where the tricks of thought, the tenseness of apprehension, the visions through the deserted streets of blacked-out memory poignantly work their stealth upon the mind of the reader.

Alarum and Excursion wasn’t adapted into a film, but reading this spoiler-filled jacket copy you can easily imagine the movie.

One more factor needs to be mentioned: the publication venues. Everybody knows that the hard-boiled tradition has its roots in Black Mask and other pulp magazines of the 1920s. What’s less often emphasized is the “slick-paper” market of the 1930s and 1940s. The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan (rather different from what it is now), The American Magazine, and many other weekly magazines ran a great deal of fiction, both short stories and serialized novels. The high-paying slick market showcased soft-boiled mysteries involving Perry Mason and Nero Wolfe and welcomed suspense fiction too. Major suspense authors of the 1940s, such as Charlotte Armstrong and Vera Caspary, would garner tens of thousands of dollars in serialization rights. On the right is the cover of Collier’s for 17 October 1942, announcing the first installment of Ring Twice for Laura, later known simply as Laura.

One more factor needs to be mentioned: the publication venues. Everybody knows that the hard-boiled tradition has its roots in Black Mask and other pulp magazines of the 1920s. What’s less often emphasized is the “slick-paper” market of the 1930s and 1940s. The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan (rather different from what it is now), The American Magazine, and many other weekly magazines ran a great deal of fiction, both short stories and serialized novels. The high-paying slick market showcased soft-boiled mysteries involving Perry Mason and Nero Wolfe and welcomed suspense fiction too. Major suspense authors of the 1940s, such as Charlotte Armstrong and Vera Caspary, would garner tens of thousands of dollars in serialization rights. On the right is the cover of Collier’s for 17 October 1942, announcing the first installment of Ring Twice for Laura, later known simply as Laura.

As mystery genres proliferated, their popularity soared. Contrary to what historians imply, the puzzle novel with a brilliant sleuth was far from defunct. Christie’s Poirot and Sayers’ Wimsey retained their fame into the 1940s, significantly outselling Hammett and Chandler. Ellery Queen’s novels are not read much today, so it’s hard to imagine a time when over a million copies of them were in print. More generally, the public’s appetite for mystery novels and radio plays was intense. In 1940, 40 % of all titles published were mysteries, and in 1945, an average four radio shows devoted to mystery were broadcast every day, each drawing about ten million listeners.

Small wonder, then, that Hollywood came calling. Curiously, the master detectives popular with the reading public wound up in B-film series (Charlie Chan, Ellery Queen) or remained unexploited in the 40s (Nero Wolfe, Perry Mason). What came to the fore, as being more suitable for the dynamic medium of film, were the hard-boiled heroes of Hammett and Chandler. Because the rise of hard-boiled adaptations fed clearly into film noir, they have attracted the most attention. But mutating alongside them, and becoming at least as lucrative, were the films shaped by the updated Gothic and the psychological thriller. Variety noticed the trend in fall of 1944.

Plain murder as a film frightener is passé. Been done too long in the same old way. Theatregoers actually can yawn in the face of manslaughter as it’s been perpetrated for the whodunits during the past year or more. . . . The newer type of horror pictures, invested with psychological implications, deal with mental states rather than melodramatic events. . . . The typical tale in the new genre crawls with living horror, is eerie with something impending, and socks its suspense thrill well along toward the middle of the story instead of doing the crime victim in at the beginning and then building a whodunit and a detective quiz as the element of suspense.

The piece doesn’t respect today’s genre distinctions. Apart from using the term “horror” in a way we wouldn’t, the author lumps together suspense thrillers like The Lodger, Hangover Square, The Uninvited, and The Suspect; the Gothic Gaslight (“a perfect example of the new approach”); and spy thrillers The Mask of Dimitrios and The Ministry of Fear. Even Jane Eyre is included, without irony. (Surprisingly, Double Indemnity from spring 1944 isn’t mentioned.) Still, the article acknowledges that mystery had strong audience appeal and that while the classic whodunit had had its day on the movie screen, films could be given new energy by other literary trends.

Mystery as artifice

Mystery is the only genre I know that makes narrative strategies as such central to its identity. A musical, a Western, or a science-fiction saga can be presented in linear fashion, telling us everything step by step, and still retain a genre identity. But a mystery plot can’t be presented straightforwardly. The writer must manipulate plot structure and narration to some degree.

A mysterious situation or plot action is one whose causes are to some degree unknown. In the detective formula, both refined and hard-boiled: A person has been murdered; what led up to it? In the Gothic: There are sinister goings-on in the house; what’s causing them? In the suspense thriller: Someone wants to harm me; who and why? (And will I escape?) To generate mysteries, the plot-maker must suppress key information. That can be done by opening late in the story (say, after the crime has been committed), by employing flashbacks (often launched from a climactic moment), or by restricting the range of knowledge (via a Watson or a string of eyewitnesses). More subtle options involve ellipses, such as those in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and the diary portion of The Beast Must Die (1938).