Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

Hand jive

The Magnificent Seven.

DB here:

In the long trailer for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Rooney Mara as Lisbeth Salander makes a gesture to show that her fabulous memory has recorded the documents Blomkvist wants her to read over. She raises her hand toward her head and flicks her spindly forefinger.

It reminded me of how important gestures are to film performances, and how comparatively rare they are today. One feature of what I’ve called the contemporary intensified continuity style is a reliance on tight facial shots, so that actors work more with their eyes, eyebrows, and mouths than with other body parts. This solves one perennial problem actors have: What do I do with my hands? But it does cut off a lot of expressive possibilities. When filmmakers used more medium and long shots, actors could use all their equipment—stance, bearing, knees (as in The Cary Grant Crouch), elbows (The Cagney Cocked Elbows), shoulders. And arms, and hands. Nowadays if actors want to activate their hands in a dialogue, they usually have to lift them to their faces because the director hasn’t provided a looser, more distant framing.

I’ve already shared some thoughts on eyes (and argued that they aren’t as expressive as we usually think), eyeblinks, and sleeves. I’ve written about hands before, and Tim Smith has tested some of the things I discussed. Now I’d like to write about two of the best hands in the business. Before I do, though, let’s look at some simpler cases.

Handiwork

Rooney/Salander’s finger flip is a one-off, a staccato gesture that communicates instantly. It reminds us that she is, for all her cybernetic genius, rather nonverbal. Her dialogue is laconic, her face impassive. The gesture comes and goes like a keystroke. If there are air-quotes, this is an air-period.

Something more emphatic happens in Wuthering Heights, as you’d expect from (a) the more extroverted emotion of the tale and (b) the fact that the owner of the hand is matinee idol and occasional ham Laurence Olivier. Early in the film, Lockwood is staying the night in Heathcliff’s dismal mansion. He tries to close a shutter, and finds the windowpane already broken. He’s startled by what he hears (“Heathcliff! It’s Cathy!”) in the stormy night. He also thinks he sees a phantom woman. Unnerved, he pulls his hand back through the pane and stares at his trembling fingers.

This occurs in the frame story. Later that evening Lockwood is told of the tragic romance of Heathcliff and Cathy, and we get an extended flashback. Cathy yearns to join the high-flown elite in the neighborhood and is about to go out with Edgar Linton. In her petulance Cathy calls Heathcliff a stable boy and a beggar with dirty hands. Heathcliff stares down at those hands (“That’s all I’ve become to you, a pair of dirty hands”), before he slaps Cathy with one, then the other, crying, “Well, have them, then—have them where they belong!”

He stumbles from the room in a mixture of anger, shame, and confusion. Coming down the stairs he confronts Linton, who has just arrived to pick up Cathy for the party. Heathcliff stands awkwardly on the stair, his hand held at an angle, as if it’s something he’d like to slough off.

Back in his stable loft, Heathcliff smashes his fists through a window, in the manner of the broken pane that Lockwood will discover in the frame story.

Later Heathcliff, now wealthy, returns to the neighborhood. When he visits Cathy, who’s now married to Linton, he initially hesitates to shake hands with his old rival. It’s a beat long enough to remind us of the class difference marked in a pair of hands.

For a more unstressed example, consider The Magnificent Seven. Throughout the movie Steve McQueen invents hand business with the apparent aim of stealing every shot he’s in. At the very start, poor Yul Brynner is trying to be the brooding main attraction, ominously lighting a cigar. But Steve is making us watch him by shaking shotgun shells against his ear and then holding his hat up against the sun.

Soon afterward Steve sets a whisky bottle precariously on a fence post while Yul is acting seriously serious. Then McQueen has the nerve to fiddle with his hat so that Yul can no longer ignore him.

Much later Steve faces down Calvera’s outlaw band and strides into the foreground, back to us.

In such a setup, the actor who turns away is traditionally ceding the audience’s attention to the frontal players in the distance. Not Steve. Once he gets into place, he swivels just a bit and swings his hand behind his gun belt. (That instant surmounts this entry.) Then he tucks one finger in his hip pocket in the lower right corner of the shot.

If Tim Smith ran an eye-scanning experiment on this shot, my hunch is that a fair number of his subjects would watch Steve’s digits.

Hands down

McQueen’s scene-grabbing reminds us that once a filmmaker has framed the performer from fairly far back, judicious use of the hands can activate areas of the frame we normally don’t watch. After all, in most shots the upper half carries the most information, especially with respect to the actors’ bodies. My favorite example of highlighting a lower corner remains a shot from Kriemhilde’s Revenge (above). The director, Fritz Lang, laid out his frames with the precision of an engineer.

Even in a less exactly composed shot, slight hand movements down the frame can add gradation of emphasis. Smash-Up: The Story of a Woman presents some hard-boiled poker players forced to listen to a radio song that interrupts their game. They sit still, but their fingers stir a little, suggesting their impatience to get on with playing.

Now we’re moving into the area I described earlier this fall as scenic density. Several of my examples there involve small gestures. To take another instance, here’s Mercedes McCambridge in her Oscar-winning performance in Robert Rossen’s All the King’s Men. As tough campaign strategist Sadie Burke, she’s trying to explain to Willie Stark (Broderick Crawford) that he’s running as a dummy candidate for the very men he opposed at the start of his political career. (The whole movie will remind any Wisconsiner of what our Governor and his pals have been up to lately.) The scene pivots around drinking, and the saliency of Sadie’s hands is heightened by the fact that the men’s hands aren’t used at all.

After she pours herself a drink, Sadie tells Willie he’s been framed, holding her glass at her waist.

She walks away to the right, then turns and says that Willie is “the goat.” She sets her glass down at the far right of the shot.

She steps toward him and leans on the chair, tipping forward.

Jack Burden (John Ireland) steps to center frame and says that’s enough. But she presses in on Willie, saying his egotism has made him blind. There’s a cut to a tighter framing as Sadie faces Willie in profile.

She turns away, mocking Willie, and yanks the speech out of Jack’s typewriter.

She steps left to the foreground and pauses, momentarily abashed by her attack on the man she loves. Her hands do something below the frame line.

Stepping back and turning away from us, she lets us concentrate on Willie. He quietly asks Jack, “Is it true?” As Sadie shifts her position, she raises her arm and we see she’s pouring another drink.

Jack replies after a pause: “That’s what they tell me.” As Willie hangs his head, Sadie’s hand emerges at the bottom of the shot to offer him the drink she’s poured. A more assertive director would have cut to a big close-up of Willie and the proffered glass, but here the information slides into a rarely used area of the frame. The Kriemhilde trick, we might call it.

Willie takes it, and Rossen cuts to a low angle on all three, with Jack and Sadie watching the key gesture: Willie, a teetotaler, downs the drink.

Now the only hand visible is his, and the narrative momentum has passed to him. He’ll change his tactics and crush his handlers.

I can’t resist a more recent example of a similar strategy. In Mysteries of Lisbon, Raúl Ruiz keeps fairly far back from his players, filming many scenes in a single distant shot. Even when he breaks the scene into shot/ reverse-shot, he can isolate gestures in the full frame in ways that echo the handwork in Kazan (and in the work of other directors, particularly in the 1910s). Elisa de Monfort, quietly mad with vengeance, calls on Eugénia, the wife of her hate/love object Alberto de Magalhães. In the opening setup, Elisa sweeps in to wait for Eugénia, setting a purse on a distant end table. (The action is quite marked on the big screen, but might be missed on video; this is the price the modern director pays for using long-shots, I guess.)

At the end of the conversation, Ruiz cuts back to the main set-up. Because of Eugénia’s position, the purse nestles in the sort of slot that we find at the bottom of the frame in All the King’s Men above. Elisa rises and goes to pick it up, her gesture highlighting it.

It contains the eighty thousand francs she is trying to return to Alberto, a love pledge he has been refusing. Elisa picks it up, then drops it back to the table, defiantly leaving it for him.

By now I’d again bet that Tim Smith would find our eyes fastened on this tiny bit of the screen. Hands point us to props, and close-ups may not be necessary.

All hands on deck

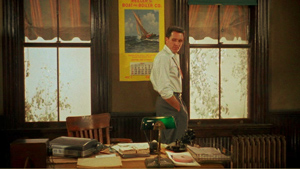

I’ve praised Henry Fonda’s handicraft earlier on this site (and in Film Art: An Introduction). Maureen O’Hara said of him: “All he had to do was wag his little finger and he could steal a scene from anybody.” But to see his long fingers and fluid wrists at full stretch, put him in a combo. There’s a remarkable six-minute scene in Mister Roberts that lets Fonda (playing Roberts), William Powell (as the ship’s doctor), and Jack Lemmon (as Ensign Pulver) make beautiful music. I can’t go through it all, but let me mention some high notes.

Roberts wants to give the crew a day’s liberty, and to that end he’s bribed a port officer with a bottle of whisky he’s been saving. But Pulver, a lecherous layabout, has convinced a nurse to come to the cabin he shares with Roberts, and he’d planned to seduce her with the Scotch. So to help Pulver out, Roberts and Doc will concoct fake Scotch with ingredients they have at hand.

As I work it out, Powell supplies gravitas, a steady ground bass of minimal, exact gestures. Lemmon, playing Pulver as wound much too tight, punctuates his passive role with nervous head movements and stabbing arms. He supplies percussive accents. Fonda’s relaxed but severe playing, neither stolid nor spiky, is the melody that floats through it all.

At the start, after the older men have entered, Pulver is slouching, Doc is wiping off sweat, and Roberts is looking for his monthly letter requesting transfer.

As Doc replaces his hat, Roberts stresses his explanation about the whisky with a quietly tapping forefinger, a gesture you can hear on the soundtrack.

When Pulver realizes that the sacred bottle is gone, he jolts into activity, frantically pointing, as if in amplified imitation of Roberts.

Throughout the scene, Pulver will echo Roberts’ gestures, as when the senior officer lays his arm across his belly.

This mirror-effect is tied to the larger dramatic dynamic: Pulver looks up to Roberts, but his selfishness keeps him from being anything like his model. In the film’s last scene, however, he will become the new Roberts.

As Roberts and Doc decide to help Pulver, they give virtually silent-film renditions of the concept, “planning and preparing.” Powell roles up his sleeves, and Roberts claps his hands and then rubs them together as if hatching a plot. Hand-rubbing will be his refrain through the rest of the scene.

No actors under age fifty today, I think, would dare this sort of straightforward stylization. Here’s something to do with your hands, cast members.

When Doc requests a Coke to add to their ethyl alcohol, Pulver yanks a bottle out from his mattress and thrusts it across the CinemaScope frame.

Doc adds the Coke with surgical precision. All eyes are on his hands, while Roberts’ hands are out of frame.

Pulver is still skeptical and sits back down on his bunk. The dramatic impetus passes to Fonda, whose long forefinger rests meditatively under his nose: Thinking personified.

Fonda has to shift his hand in order to remark that Scotch has always reminded him of iodine. But what other actor would rotate his wrist and stick his thumb under his eye as he says that line? Try it yourself, and I bet you find it awkward. He executes it smoothly.

Without having to get up, Roberts reaches back into the medicine chest and pulls down a bottle of iodine. He passes it to Doc and signals the handoff with a little flourish.

Earlier we’ve seen Doc do the mixing as a solo performer, in the over-the-shoulder shot shown above. As Doc blended the stuff in other framings, Fonda kept his hands below the desk top, giving Powell the stage. But now we get two for the price of one: Powell’s meticulous adding of a drop of iodine to the brew, Fonda’s revisiting his calculating hand-rubs.

Fonda’s slightly out-thrust tongue is a grace note.

Pulver tries to sample the blend, but Doc beats him to it. “We’re on the right track!” he declares. Doc asks Roberts what else he’s got and Fonda, in a beautiful medium-shot with eye-catching colored medications arrayed before him, mimes the act of mulling over the next ingredient. His hand flits gracefully over the bottles and jars.

They settle on hair tonic for a touch of ageing. Again Doc adds the ingredient with precise pouring, and now he prepares for Roberts to test it. Into the frame come Fonda’s hands.

To accentuate the climax of the scene, Roberts rises to take the drink, forestalling Pulver.

Roberts clears his palate, then drinks it, pinky extended, as daintily as a lady at a party.

He stares at the glass, swallowing. Then Fonda’s hand lowers out of the frame so as to let us concentrate on his expression. His strangled line tops the whole comic arc: “You know, it does taste a little like Scotch.” Now his face does the work.

All three players are reintegrated into a master shot: patient Doc, frantic Pulver, and stalwart Roberts as they realize they’ve succeeded. Pulver, after lunging with his characteristic abruptness, finishes the glass in a hunched-over gulp.

“Smooth!” he yelps.

You might argue that such hand jive is rather “theatrical,” and perhaps some of the business came from Fonda’s three years in the Doug Roberts role on Broadway. Even so, it has clearly been recalibrated for the cinema. Theatre taught actors how to use their hands, but cinema gave them further lessons, and film directors learned to choreograph hands in relation to framing and shot scale.

My discussion doesn’t exhaust the scene, but I hope it suggestst how choices about staging and performance can make hands carry story information and express character. They can add nuance to a moment; they can surprise us by slipping into and out of visibility; and they can inflect a facial expression or line reading. If filmmakers today lock their framing on facial close-ups and moving lips, they’re depriving us of some beautiful music.

P. S. 18 January 2012 (from Midway, Utah and the Art House Convergence): Thanks to three alert readers. First, Adrian Martin spotted an orthographic error, now corrected. Second, David Cairns of the indispensable Shadowplay) writes of scene-stealing in The Magnificent Seven:

You do know what Yul said to Steve? “If you don’t stop playing with your hat, I’ll take off my hat, and then we’ll see who they’ll look at.”

And from James Benning, with the laconic message: “Here’s another.”

I wrote about Jim’s related project here.

P.P.S, 20 January 2012: This entry’s title, as many readers noted, referenced the great Johnny Otis song “Willie and the Hand Jive.” Today Ethan de Seife writes to tell me that Johnny died the day before my blog was posted. So take it as not only an homage but a valedictory.

Mr. Roberts.

You are my density

DB here:

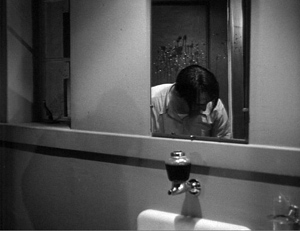

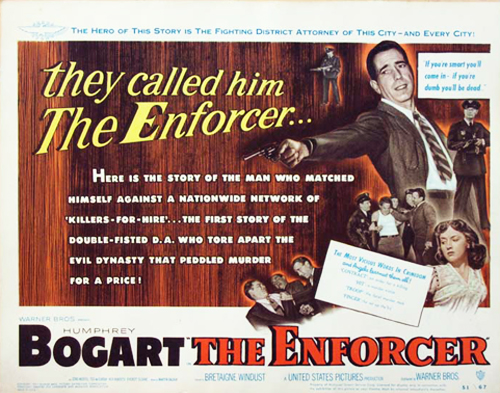

The mobster Joseph Rico is in protective custody; tomorrow he testifies against the big boss. But Rico fears reprisals, so he decides to escape. While a sleepy cop guards him in the washroom, he bends over the sink and rinses his face.

Turning so suddenly that water spatters on the mirror, he grabs the cop in an armlock and slams his head against the sink, just below the frameline.

Rico turns to the window to make his escape.

What interests me in this passage from The Enforcer (1951) is not just what happens in the mirror but also what happens on it. While Rico belabors the cop’s head, we’re given a chance to notice the splash of water that hit the mirror when Rico whirled to the attack. While the action is moving forward, we’re reminded of what had triggered it.

We get a sort of parallel reminder in the next scene, when we see the wounded cop again. He’s sporting a big bruise on his left temple, a souvenir of Rico’s assault.

Pfui. Details, you might say. Or you might (correctly) instance this as another case of Charles Barr’s enlightening notion of gradation of emphasis. But it’s worth getting a little more specific, because even this simple scene (by non-auteur director Bretaigne Windust) offers us something to think about, and something for today’s filmmakers to try.

Most films today don’t fully exploit the visual dimension of cinema. True, we have dazzling CGI and fancy camera moves. But when it comes to less flamboyant scenes, directors have limited their options by relying too much on stand-and-deliver and walk-and-talk. There are other aspects of visual storytelling that today’s filmmakers neglect. One aspect is the possibility of gracefully moving actors around the set in a sustained fixed shot. A specific tactic I’ve mentioned before is the Cross, and another involves ways to get people into a room. The option I’m going to sermonize about today is what I’ll call scenic density.

By scenic density I mean an approach to staging, shooting, and cutting in which selected details or areas change their status in the course of the action. I don’t count the bustle of background business, all that street traffic that is so much pictorial excelsior in our movies. Nor do I refer to stuffing the setting with desk and kitchen flotsam, allusive pop-culture posters, and the other distinctive “assets” that will be exploited when the film’s world gets transposed to a videogame. I mean something more expressive and intriguing.

Using it up

Go back to the Enforcer scene. The shot’s composition creates a delimited zone of action. The guard cop is framed tightly in the mirror. When the fight breaks out, it’s initially framed in that mirror–a narrowing of visual importance. Moreover, the shot is designed to highlight the spatter on the mirror. It’s fairly prominent, stuck near the center and, providentially, in the spot that the cop’s head initially occupied. The lighting picks out the drips, and in a shot where the figures move in and out of frame, there isn’t an equally constant center of interest. We’re probably concentrating on Rico’s punishing of the cop, but the dribbles of water remain prominent enough to claim our interest, especially when Rico passes out of frame.

So here’s my first condition for scenic density: the shot keeps several items of dramatic significance salient in the composition.

This technical choice asks the filmmaker to think of the frame as a field of dynamic masses and forces. Such an idea was part of the aesthetic of “advanced” European and Japanese silent cinema of the 1920s. Many directors explored this dynamism, often aided by low angles and wide-angle lenses. Here are examples from Eisenstein’s Old and New and Murnau’s Tartuffe.

This pictorial density became especially prominent in American cinema during the 1940s, when low angles, wide-angle lenses, and locations and smaller sets encouraged cinematographers to pack their compositions snugly, as in this shot from Panic in the Streets.

Boris Kaufman, cinematographer for Jean Vigo and Elia Kazan, summed up the principle:

The space within the frame should be entirely used in the composition.

Since cinema is a time-bound art, however, the salient elements in the shot could and should change. But if the frame space is wholly “used,” what room is there for change? The only options are to have the using-up elements shift position, or to reveal that the frame isn’t used up.

Vivid instances, also from the 1940s, can be seen in Anthony Mann’s work, both with and without John Alton. Generally, Mann used the new fashion for depth composition, especially big foreground elements, to heighten scenes of violence. Physical action becomes more aggressive if people rush the camera and halt in tight close-up, especially because wide-angle lenses tend to accelerate movement to the foreground. Mann thrusts violence abruptly to the camera with an almost comic-book effect, as when the club owner is shot in Railroaded, or a man is flung to the floor in Raw Deal.

Even when this in-your-face tactic isn’t employed, the Mann films find ingenious ways to develop what seem to be completely locked depth compositions. In Border Incident, Ulrich confronts the Mexican government agent Pablo, disguised as a Bracero. A looming depth shot is followed by a reverse shot displaying a compact composition.

Is the frame space fully used? The second shot above is opened up when Ulrich leans forward to sock Pablo, creating a vacant spot on the far right for Pablo to fall into. The shot is emptied and re-filled, dense once more.

Memories, memories

Aha, you may be saying. Density just refers to squinchy, fussy shots from an era that favored cheap flash. No. The Enforcer shot isn’t all that cramped. Of course the blank, unchanging walls serve to highlight the mirror-reflected fight and the water dribbling down the glass, but you can imagine how much more jammed and skewed Mann’s treatment of Rico’s escape would be. As for the flashier depth, I just needed some clear-cut cases of density, examples in which details and spatial zones become starkly salient. Now I want to suggest that scenic density can be achieved in something more spacious, even monumental. That has to do with time and memory.

Part of what gives the Enforcer shot its interest is the superimposition of two moments of action in a single space: Rico’s diversionary turn from the washstand, recorded in the splash he made on the mirror, and the struggle taking place a few seconds later. A further trace of that struggle and that splash is visible in the bruise on the cop’s head in the next scene.

That dripping spatter can stand in for the second quality of spatial density I want to highlight: Its capacity to coax us to recall earlier action in the locale. Characters leave their marks and spoors in the space, and those get activated as memories. Unlike the slick surfaces of today’s settings, in classic films the settings can bear the impress of human transit, leading us to recall bits of behavior and emotional states. Let me illustrate from Lang’s Hangmen Also Die (1943).

It’s Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, and Gestapo Inspector Ritter is questioning Mrs. Dvorak, the vegetable seller who could identify the woman who misled the officers pursuing an assassin. Torture, or at least what we think of as torture, hasn’t started. She is simply standing in front of his desk as he brandishes his riding crop in the manner of a good movie Nazi.

When Mrs. Dvorak denies knowing the woman, Ritter taps the back-rest of the chair. It simply falls off, and we realize it’s not fastened to the chair.

Ritter says, “Pick it up again.” Now we realize that intimidation has been applied for some while; Ritter has made the woman stoop to replace the back-rest many times. She does so again as the camera tracks back. This is nicely detailed too. She starts to pick it up by bending over, finds the effort too painful, and then goes to her knees to pick it up–just as Ritter taps his riding crop against her hand, a teacher gently chiding a slow pupil.

As Mrs. Dvorak rises to put the piece back in place, the camera pans slightly right to pick up the woman bringing in a tray. Happily Ritter sniffs the coffee jug and resumes questioning the old woman.

Cut to a shot of her by the chair. “Let’s start from the beginning,” says Ritter, offscreen. Unthinkingly Mrs Dvorak starts to rest her hand on the loose slat, forgetting that the top slat is unattached. It’s a natural response. She’s been standing there for a long time and would like something to rest on, and the chair is temptingly close. (Presumably, that’s its purpose, to taunt the unwary prisoner forced to stand a long time.) Remembering just in time, she yanks her hand away. If she knocks the back-rest off, she’ll just have to pick it up again.

Cut to Ritter. “Don’t be nervous, Mrs. Dvorak. I’m prepared to—”

Cut to Mrs. Dvorak. As he continues, “–devote to you all of tonight,” she forgets herself again and relaxes her hand, this time on the back-rest. It falls off, making her start.

She looks up as Ritter says, offscreen: “Even longer if necessary.” Cut to Ritter, gesturing with a piece of sausage and saying, coaxingly, “Well?”

Slowly she goes to her knees again as the camera tracks in on her.

Back to Ritter: “That’s the girl.” Back to her, rising in pain to replace the back-rest.

The scene concludes with Ritter reminding Mrs. Dvorak that she’s in Gestapo headquarters. She acknowledges that she doesn’t expect to leave without giving information. He starts his questioning all over again as the scene fades out.

This quietly suspenseful scene establishes a bit of furniture as a key prop. Once the faulty back-rest is marked for our notice, we’re expected to remember that it’s a means of intimidation–something that Mrs. Dvorak, in her anxiety about refusing to aid the Nazis, twice forgets. Lang’s shots, simple and uncrowded, makes the chair, like the spattered mirror in The Enforcer, preserve the trace of human activity. Yet it’s more acutely integrated into the scene’s drama than the mirror, and remembering how it was used earlier makes us wait tensely to see how it will be used again.

Long-term density

Several scenes later, the Nazis threaten to kill four hundred Czech hostages if the assassin isn’t turned over to them. Mascha Novotny has set out for Gestapo headquarters to denounce the man she helped, but she changes her mind and decides not to betray her country. She will only plead for her father’s life. Once more we’re in Ritter’s office.

Centered in the frame, standing out as a pale oblong against the grayer background, the fateful chair is made salient during Mascha’s conversation with Gruber. I suspect there’s a sort of spatial suspense here–will she move to the chair and dislodge the precarious piece of wood?–but more important, I think, is the fact that the chair ineluctably reminds us of Mrs. Dvorak and her quiet resistance to pressure.

Ritter leaves to consult his superiors. When he comes back, a new composition keeps the chair prominent and lends a new centrality to the clock on Ritter’s desk, surmounted by a snarling cat or something like it. (It’s visible in shadow in the earlier scene with Mrs. Dvorak.) But now the camera arcs to minimize the Dvorak chair and show the beast and Ritter targeting Mascha.

Soon enough, as if to make sure we remember, Mrs. Dvorak is brought back in, having undergone serious torture. The camera positions reactivate our memories of the earlier scene.

As she continues to lie to protect Mascha, Mrs. Dvorak never touches the chair. Although she has been tortured, she seems wearily defiant, as if her refusal to aid the Nazis has given her some strength: no need to lean on the chair now. As a final cue to our memories, Lang has Ritter play once more with his riding crop, letting its shadow fall on her heart.

The threat is clear: For lying, the old woman will pay with her life.

The chair reappears in a later scene, but I’d argue that then it serves more as a pointer to another prop. The resistance movement fights back by framing Czaka, a beer baron sympathetic to the Nazis, as the assassin. Lang could have explicitly recalled the questioning of Mrs. Dvorak by having Czaka lean on the slat and knock it off. Instead, the composition makes Ritter’s clock more important than it was in earlier shots. As Czaka tries to defend himself, the framing blocks our view of the chair but emphasizes the snarling catlike creature on top of the clock. And the chair has shifted a little off and become a bit darker; it’s no longer as salient.

This cluster of scenes from Hangmen Also Die illustrates how scenic density can add layers to a film. One scene recalls another not only by similarity of situation and locale but by tangible marks left on it by earlier action. Having seen Mrs. Dvorak subjected to Ritter’s oily intimidation, we generally expect something like it to be applied to Anna. This conventional situation is given a rich, concrete presentation by the repeated camera positions and the simple chair that, unmoving, enters into the drama.

Of course as a Hollywood director, Lang was pressured to reuse sets and camera setups. That saved money and time. But he turned such repetitions to his advantage by letting certain objects come forward at crucial moments. They not only become part of the drama but prime us to remember them, and what they revealed, in ensuing scenes. And even though Lang never pursued the aggressive, packed deep-focus of other directors working in the 1940s, he shows how roomier, less pressurized compositions could still be charged with echoes of earlier bits of behavior.

Is this sort of visual-dramatic economy, calling on precise memories of concrete actions, lost in today’s American cinema? I suspect it is.

In studying Hangmen Also Die, I was curious about a perennial problem. Was the byplay with the chair a Lang invention on the set, or was it some version of the script, or in the original story by Lang and Bertolt Brecht?

The film didn’t have a secret script, as the poster says, but the sources do remain a bit obscure. A draft of the original story signed by Lang and Brecht, in that order, exists. It indicates only that the greengrocer, called Frau Blaschke, is subjected to eight hours of “the usual Gestapo brutality” and refuses to identify the girl. There were other drafts of the screenplay, but I don’t have access to them, if they exist, and standard sources on Brecht in Hollywood don’t mention this scene’s details.

Somewhere along the line, though, the chair-back business was concocted. I found the shooting script signed only by John Wexley (Brecht claimed that he was robbed of credit) and annotated in pencil, perhaps by Lang. That script indicates that Ritter’s room contains “a vacant chair with its seat close against desk.” and Mrs. Dvorak is standing beside it as the scene begins. Much of the dialogue is the same , with some slight changes notated in pencil, possibly by Lang. But the camera movements indicated are different from those in the final film, and more importantly so are the actions. After Mrs. Dvorak claims that she doesn’t know the woman who helped the assassin, we read the following. I indicate pencil notations with {}.

In her fatigue, she places hand on back-rest of chair. But its dowels are loose and back-rest clatters to the floor.

RITTER (saccharine): Pick it up, Mrs. Dvorak.

CAMERA MOVES IN CLOSE as she obeys, stooping with painful fatigue–she has done this many times tonight.

RITTER: Now put it back in place, Mrs. Dvorak.

(She does so)

As Ritter questions her:

MED. SHOT – MRS. DVORAK. Without thinking, she is about to place hand again on loose back-rest–when she remembers and jerks back.

RITTER’S VOICE: Now don’t be nervous, Mrs. Dvorak…I’m prepared to devote to you all of tonight–and even longer, if necessary.

Mrs. Dvorak, unconsciously reacting to this, once more rests hand on chair. {She jerks back but} The piece of wood clatters to the floor.

MED. SHOT – RITTER. Ritter waits patiently; when she doesn’t move, inquires:

RITTER: Well…?

CAMERA PULLS BACK to INCLUDE Mrs. Dvorak, who stoops to repeat painful routine. Ritter smiles approvingly.

RITTER: That’s the girl.

Nothing here is indicated about Ritter’s riding crop, nor does he initially knock the back-rest off the chair. Mrs. Dvorak does it herself, accidentally. And the scripted line is “Pick it up, Mrs. Dvorak,” not, as in the finished film, “Pick it up again, Mrs. Dvorak.” The film version makes it clear that the byplay with the backrest is part of Ritter’s softening-up technique, something indicated in the script but not spelled out.

The later scenes in the film show other differences, mostly additions of things not mentioned in the shooting script. For instance, the script doesn’t mention the shadow of Ritter’s riding-crop. But the excerpt shows that the shooting script points toward some of the detailing we find in the finished film. It provides the sort of nudges that a director, especially one as oriented to gesture as Lang was, could elaborate on the set.

The Lang/ Brecht story has been published as “437!! Ein Seiselfilm,” in The Brecht Yearbook vol. 28: Friends, Colleagues, Collaborators, ed. Stephen Brockmann (2003), 9-30. The passage I mention, kindly translated for me by Ben Brewster, is on p. 16. Broader background on Brecht’s adventures in Hollywood can be found in James K. Lyon, Bertolt Brecht in America (Princeton University Press, 1980). Chapter 14 of Patrick McGilligan’s Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast (St. Martin’s, 1997) offers an account, mostly relying on Brecht’s viewpoint, of the making of Hangmen Also Die. The shooting script is in the John Wexley collection of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research and the State Historical Society here in Madison. Thanks also to Marc Silberman, renowned Brecht expert, for advice.

Play it again, Joan

“The happy heart loves the cliché.”

–Myra Hudson (Joan Crawford) in Sudden Fear.

Sometimes your audience gets what you’re saying faster than you do. Years ago, after I gave a lecture in a class at Columbia University, a grad student came up and said: “What you’re doing is looking for the conventional side of unconventional films and the unconventional side of conventional films.” I’d say it’s not all I try to do, but the student’s chiasmus does capture a lot of what interests me.

It’s especially on target for Hollywood cinema. I don’t understand criticisms of Hollywood for not being realistic. It’s a highly stylized, artificial cinema, only a few notches above ballet or commedia dell’arte. Some of our best critics, like Parker Tyler and Manny Farber and Geoffrey O’Brien, have understood this. All the artifice will demand plenty of conventions, yes, but there are always filmmakers ready to treat them in fresh ways. And the churn is swift. American studio cinema is constantly finding new variations on its traditional forms, formats, and formulas.

Do-overs are allowed

Sleep, My Love

Take replays. The repeated sequence has become so common in our movies that nobody much notices it any more. We’re quite used to seeing an earlier action revisited. Often the replay simply serves to remind you of what happened, as when clues to a mystery are given in fragmentary flashbacks. The replay may also aim to get you absorbed in a character’s mental life. John, the hitman in John Woo’s The Killer, is traumatized by the fact that he blinded an innocent woman during a contract hit, and the moment of her wounding haunts him.

Sometimes, however, we get multiple-draft replays, in which the second version significantly alters the first. A common gambit is to have the second version show more of what happened, as in the money drop in Jackie Brown. Other cases show contradictions, as when conflicting testimony is dramatized in flashbacks. The most recent version I’ve seen occurs in The Debt, when the central 1966 section of the film concludes by showing what really happened when Dr. Vogel slashed Rachel and fled. In such cases the replay becomes less a true repetition and more of a revision, a new version questioning or canceling what we’ve seen before.

The idea isn’t new. You can find the replay in various forms in trial films of the 1930s, as I’ve discussed here. But the replay really came into its own during the 1940s. Directors and screenwriters experimented with the device as part of a broader initiative, burrowing into new niches in the ecosystem of classical narrative.

In those films, it’s common for replayed scenes to show an incident haunting the protagonist, as when the tormented bride of The Locket is assailed by memories as she walks down the aisle. Sometimes a flashback fills in information that was cunningly omitted from the earlier version, as in Mildred Pierce. And we also have competing accounts of what happened, as variant replays furnish multiple drafts. The most famous example is probably Crossfire.

By 1950, Joseph Mankiewicz could dream up one of the most daring experiments of the period, one that anticipated the repeated scene in Persona. For All about Eve, Mankiewicz planned to present Eve’s memorable monologue about the power of theatre twice: first through the sympathetic eyes of Karen (Celeste Holm), then from the perspective of the bitter Margo Channing (Bette Davis). What would viewers and other filmmakers have made of it? But Fox studio head Darryl F. Zanuck ordered the replay dropped, for reasons I speculate about in this entry’s codicil.

Mankiewicz’s unseen experiment with Eve’s “Audience Aria” reminds us that replays affect the soundtrack too. The most common use of replays is probably auditory, that line of dialogue that flits through a character’s consciousness—an auditory flashback, in effect. “Who knows what you may do the next time?” asks the sinister voice of the psychiatrist as Alison (Claudette Colbert) totters up the stairs in Sleep, My Love (1949). Several snatches of dialogue can flow together to recall a host of earlier scenes. In The Hard Way (1943), on another staircase, Katie (Joan Leslie) becomes distraught as bits of dialogue spoken by several characters flash through her mind.

More unusual is the audio replay in Duvivier’s wonderfully stylized Lydia (1941). A flashback to a ball is introduced by Lydia’s voice-over, recalling the splendid ballroom with its mirrorlike floors and the “divine aggregation of musicians, hundred of them, I think.”

But then her old lover corrects her memory and we get a flashback showing a more modest ballroom with a small ensemble.

Over these later shots, however, we hear bits of Lydia’s earlier description of the big ballroom and troops of musicians, in contrast to what we see. The sound flashback functions as a wry narrational commentary on Lydia’s stubborn romanticism.

Purely auditory replays tend to be subjective, but could we have an objective one? And can it promote surprise and suspense? As we say in Wisconsin, you bet. (Not you betcha.)

The replay machine

A lighthearted instance appears in The Pajama Game (1957). Sid Sorokin (John Raitt) , the new superintendant at the Sleeptite Pajama Factory, is falling in love with Babe Williams (Doris Day), the no-nonsense head of the labor union’s Grievance Committee. He sings into his Dictaphone about her in the song, “Hey, There (You with the Stars in Your Eyes).”

At the end of the song’s first section, he plays it back and then comments sourly on the lines he’s just sung. By the end, he’s joining himself in a duet, harmonizing nicely.

This instant playback wasn’t a cinematic invention, though. The same number, including the Dictaphone gimmick, was employed in the original Broadway production.

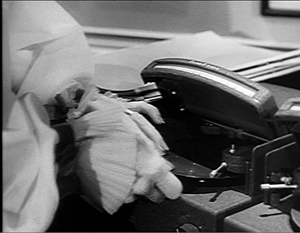

The Dictaphone, which used both wax cylinders and plastic belts for recording, was a popular device for businesses. Erle Stanley Gardner employed it for dictating many of his novels. A competitor to the Dictaphone was the SoundScriber, a late 1940s device using vinyl phonographic discs. The SoundScriber figures in a more sustained and suspenseful replay scene a few years before The Pajama Game.

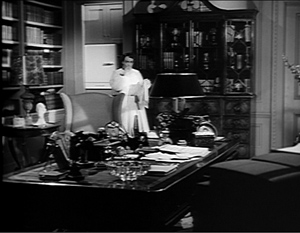

In Sudden Fear (1952), Myra Hudson (Joan Crawford) is a prosperous playwright who has outfitted her office with a SoundScriber. She uses it for dictating plays and correspondence. One evening before a party, euphoric after her new marriage to the handsome actor Lester Blaine, she meets with her attorney to prepare a new will. He proffers a draft that assigns a modest sum to Lester, but she considers it insulting. She switches on the SoundScriber and dictates a new will, one leaving all her estate to Lester.

But we’ve had our suspicions about Lester, since he’s played by Jack Palance, an actor with more juts to his facial planes than a Giacometti bust. Our fears are confirmed after Lester hooks up with his old girlfriend Irene (Gloria Grahame). When they learn that Myra is making a new will, they believe she’s going to give the bulk of her estate to a foundation.

On the evening of the party, as she starts dictating her new will, the guests arrive and she descends to meet them. Irene and Lester slip away and meet in Myra’s study. Fade out on Lester closing the door.

Next morning, Myra return to her study and discovers she left her SoundScriber on all night. She hits replay and listens to herself bequeathing all her money to Lester. This is the replay that launches the big action. As she’s about to switch off the machine, she hears the conversation starting between Lester and Irene. The microphone, left on accidentally, has picked up their plotting.

The couple is still under the false impression that the new will leaves Lester penniless. We hear him declare his contempt for Myra while caressing and embracing Irene. They start planning to kill her before she can sign the new will.

The SoundScriber scene gives us two plot developments, past and present, simultaneously. The recording fills in the gap left by the fade-out: Now we know what happened behind those closed doors. On the visual track, we can watch Myra’s developing anxiety about the couple’s murder plot but, more piercingly, we register her realization that Lester has never loved her.

Across seven minutes, Joan Crawford executes a carefully modulated solo performance, for the most part with no accompanying score. Meanwhile, Palance and Grahame get to act viva voce. And David Miller’s direction scales and times things nicely. I won’t try to analyze the very end of the scene, let alone its frenzied aftermath. I just want to trace the dynamics of the double-layered time scheme the replay machine gives us.

Joanie, more than shoulders

The recorded scene develops from the lovers’ frustration with keeping up a false front, then to their suspicion that Irene will cut Lester out of her will, then to the mistaken belief that she’s just done so, and finally to their decision to kill her. Myra’s playback scene proceeds, I think, in four stages as well. Myra starts out placid and almost giddy in her love for Lester. She’s abruptly shocked and disenchanted when she learns he doesn’t love her; her stomach churns. A third phase consists of her discovery that Lester and Irene intend to kill her, and she devolves into sheer panic. The last phase, of which I’ll show only a bit, initiates a search for a way to defend herself.

Myra comes in euphoric. As she replays her dictation of the night before, she strolls around her study, going far back to the distant refrigerator for a glass of milk and then coming forward. She seems to savor hearing again her own declaration of her devotion to Lester.

Myra’s circuit around her study isn’t just filler: it etablishes the rear area for use later. But now, as she’s about to turn off the recording, she hears Lester’s voice: “What’s up?” She backs up a little, bumping the desk as she realizes that there’s more on the disc. This recoil, as a performance decision, will get magnified in the course of the scene. Then Miller cuts to a reaction shot.

The first of several optical point-of-view shots gives us a close view of the twin SoundScriber units (good for product placement too). Myra has set the milk down on the console.

As we hear Lester venting his contempt for her, Myra’s eyes fill with tears. Worse, he adds that he’d like to tell her he never loved her for a moment. “I’d like to see her face.” He can’t, but we can; in the closest shot yet, she looks right at us. Hollywood can be brutal.

She turns away and, seen from a new angle by the desk, she advances toward us. On the track, Lester is pitching woo to Irene. Myra realizes that he lusts for this other woman. She sighs. Listen closely and you can hear her emit a soft whimper as well.

Another cut to the SoundScriber as Lester says he dreams of holding Irene: “I don’t know how I stand it, not being with you.” On these last few words, cut to Irene, turning away in shame.

She rushes back, having heard enough. A low angle shows her about to switch off the horrible recording when Irene is heard noticing the attorney’s draft of the will on the desk. “It’s the will!” Myra freezes, accentuating the line, and then starts to turn when Lester begins to read the draft.

Having hidden her face from us for a little while, Miller’s direction makes the next close view all the more powerful. (Note the eyebrow work.) Lester’s reaction to the will proves it’s been about the money all along. As he curses Myra, she doubles over grabbing her stomach. This, I take it, is the high point of the scene’s second phase–a sheerly physical reaction to Lester’s cynical betrayal of her love.

Phase three starts, I think, when Irene is heard purring, “Suppose she isn’t able to sign it on Monday.” The line is heard over a shot of the machine, and not a POV at that. The visual narration cunningly delays, by just a few seconds, Myra’s reaction to Irene’s hint. The cut shows her listening, stunned. Lester agrees with Irene. “I’d get it all! Why not?”

Myra turns, as if in disbelief, and a closer view of SoundScriber underscores Irene’s response: “Lester, I have a gun.”

This triggers the scene’s big movement: Myra’s retreat from the recording. Back to the extreme long shot, low angle, as she hurls herself toward the rear wall and sidles along toward the refrigerator, taking refuge behind the chair. The lovers discuss how to arrange an apparent accident, all the while kissing and declaring their love. Lester exclaims, “I’m crazy about you! I could break your bones!” as only Jack Palance could say it.

Again we get an optical POV shot, but now from Myra’s position across the room as Lester muses on “a nice little accident.” And in the cut back to Myra, we hear Irene say, “We’ll work something out. I know a way.” The recording needle is stuck in a groove, and we hear her say it again: “I know a way.” Music comes up for the first time, shifting the action to a new pitch.

I know a way. This mechanical glitch, I think, pushes fear into panic. The tightest close-up yet of the spinning disc is a sort of mental subjectivity: It’s not what Myra sees exactly, but an expression of her being riveted by insistent, maniacal repetition of Irene’s assurance: I know a way. Myra rushes out of the shot and hurls herself into the bathroom to vomit. All the while we hear, again and again: I know a way.

The couple’s plotting has driven Myra out of the room, as the music rises and nearly suppresses Irene’s “I know a way.” In a closer view of the bathroom, Myra staggers to the sink and splashes water on her face, while the record still spins and Irene’s voice taunts her.

But now we get the start of a new phase, with Myra trying to seize the initiative. In a burst of anger she rushes back to the machine, switches it off, and fumblingly takes out the disc. By the time she does so, we’ve heard Irene’s “I know a way” thirty-one times. Talk about hammering the audience.

Myra grips the disc, proof of the criminal conversation, and….

…But my analysis has gone on too long. It’s reasonable, although mean, to stop with the end of the replay. The rest of the sequence builds on what we’ve heard and seen, developing Myra’s efforts to defend herself.

I should note, though, that there follows a hallucinatory sequence in which we get not only perceptual subjectivity, like the POV shots, but also mental imagery and sounds as well. That sequence also includes auditory flashbacks of the usual sort, Myra’s anxious memories of things that Lester and Irene said on the SoundScriber recording. They’re replays of a replay, if you want to get fancy about it.

Conventioneering

In a way this scene is just a variant of a common storytelling convention: Someone accidentally overhears a key piece of information, in an adjacent room or over the phone. But the sequence shrewdly recasts this convention in ways that pay off on many dimensions. We get the suspense attached to the lovers’ mistaken belief that Myra will cut Lester out, and we get Myra’s reaction to it. That reaction is compounded of her sense of betrayal, her disillusion, and her realization that she’s in danger. Had she been eavesdropping on their conversation, she could have burst in on them and denounced their misreading of her will. As it is, she must helplessly listen to them unfold their plans.

After more than a decade of female Gothics–aka”woman in peril” movies, aka I-think-my-husband’s-trying-to-kill-me movies–from Suspicion and Gaslight to Woman in Hiding, Miller and his colleagues found a fresh way to put a lady in a cage. Schema and revision, a key process in the history of any art form, allows ingenious artists to remake what tradition hands them. Twenty years later, Francis Ford Coppola and Walter Murch would build an entire movie, The Conversation, around the audio replay and its possibilities for objectivity and subjectivity. Over and over, the unconventional burrows inside the conventional.

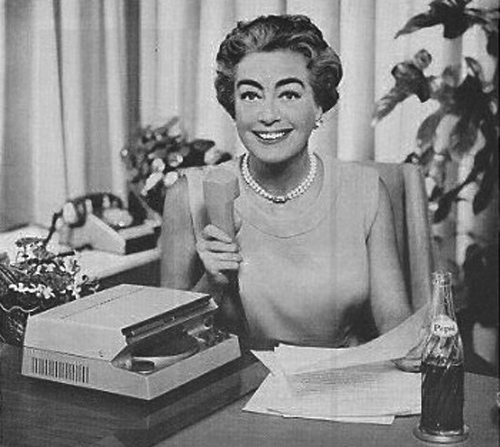

After this film, Joan Crawford became a spokesperson for SoundScriber. (See below.) Who would know better than she the advantages of the gadget? Perhaps Joan even had a stake in the firm. Such fruitful synergy wouldn’t be unknown in Hollywood. Jack Webb found the Teleprompter so useful in shooting Dragnet episodes that he invested in the company.

On All About Eve and Zanuck’s purging of the replay of Eve’s monologue: I suspect that it was a forced byproduct of another decision Zanuck had taken. The film consists largely of flashbacks, and Mankiewicz had intended to move through them by shifting from one character to another. At the awards dinner the flashbacks begin with Karen, and then another block of them, grounded in Margo’s memories, was to take up later episodes in Eve’s ascent to stardom.

But the film ran very long, so Zanuck cut the framing portion at the dinner that would have introduced Margo’s flashbacks. The result is that in Karen’s flashback, we occasionally hear Margo’s narration of certain episodes Karen didn’t witness. But once we’ve lost Margo’s narrating frame, then it becomes quite difficult to justify re-hearing Eve’s ruminations on theatre from anything approximating her point of view. I suspect that consistency of this sort played a role in Zanuck’s cutting Eve’s monologue. Plus it was a pretty daring move on Mankiewicz’s part. And the film is already pretty long. The fullest account of the changes, though still not as specific as I’d like, is in Sam Staggs’ All About All About Eve (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2001), 170-172. As Staggs points out, Mankiewicz did work differential-viewpoint flashbacks into The Barefoot Contessa (1954).

Sudden Fear is available on a so-so DVD transfer from Kino Lorber.

The interplay between film and fiction in the 1940s is fascinating, and we can sometimes find rough equivalents between techniques. Here is a stream of auditory flashbacks in Steve Fisher’s novel I Wake Up Screaming (1941), ending with the protagonist’s inner monologue.

I’d remember Lanny Craig saying: “They crucified me . . . it was because of Vicky Lynn!” And the night Robin Ray said: “She’d laugh, see, and it was like Guy Lombardo’s band playing.” And Hurd Evans: “I only get two hundred and fifty a week.” Tick-tock, the faceless clock on Sunset. “It’s possible to build a case out of nothing,” the assistant district attorney said. Where was Harry Williams? If he’d been murdered, where was his body?

By the end of the thirties, of course, such montages were already heard in radio programs as well.

Joan Crawford was also a spokeswoman for Pepsi-Cola, having married the man who became the company’s CEO. This image comes from a nifty survey of her endorsements available here.

Despoiling the movies

The Denton Record-Chronicle (28 December 1947).

DB here:

The last line of Otto Preminger’s Daisy Kenyon is “When it comes to modern combat tactics, you’re both babies compared to me.” If you haven’t seen the film, does knowing that ruin it for you? Suppose I went further and identified the character who spoke the line, or the immediate circumstances, or the action leading up to it? Would knowing these things ruin your pleasure? Or would it give you a different sort of pleasure?

Who doesn’t come to Casablanca knowing about “Here’s looking at you, kid,” or “Play it, Sam,” or “Round up the usual suspects”? You likely saw the ending of King Kong in compilation films before you saw the whole movie, yet you probably still watch it with enjoyment. I saw Potemkin’s Odessa Steps sequence many times, on an 8mm reel I bought as a kid, before I saw the whole movie. I still enjoy Potemkin, possibly more than many who see it for the first time. Yet people complain about trailers that tell too much, and critics who give plot twists away. Accordingly, it’s been a convention of fan and Net writing that if you’re going to give away major story information, you alert readers with the word “spoiler.”

Surely people want to know something about a film’s story. Viewers clamored for the most basic information about Super 8. And evidently many moviegoers would feel less disgruntled about The Tree of Life if they had known in advance a little bit more about what they would encounter. It seems we want to know about the story’s basic situation, but not too much about how things develop. Say: bits from the first half-hour or so, up to the beginning of the Second Act (or what Kristin calls the Complicating Action). Beyond that, we want things kept quiet. Above all: Don’t tell the how things turn out in the end.

I’ve been driven to think again about spoilers after Jonah Lehrer reported on an experiment with literary texts. On the whole, readers in the study reported enjoying a short story somewhat more if they knew the ending in advance. Jim Emerson has provided his characteristically stimulating commentary on this finding, and his readers, surely among the most reflective in the online film community, have supplemented his thoughts.

This discussion overlaps with a question I raised a while back on this site. How can we feel suspense if we know a story’s outcome? One standard answer, which would apply to spoilers too, is that even with foreknowledge, we’re interested in how that turn of events comes about. This possibility is invoked by some of Jim’s readers, and it seems plausible, especially if one is a connoisseur of storytelling. How, we ask, does the narrative engineer this or that twist?

My further proposal in the blog entry was that our mind’s intake of narratives is modular in some respects. Part of us reacts as if we were encountering the events fresh, without knowledge of what is coming up. The analogy was to standing on a balcony overhanging a precipice. You know that you cannot fall, but when you imagine yourself falling, you feel a twinge of fear all the same.

The same might be true of consuming a narrative. One of our mental systems, fast but fairly dumb, reacts to things as they come, while secure knowledge hovers more distantly in the background. I suggested as well that the way that something is presented–say, with fast cutting or sweeping music–can override our knowledge and kindle a basic, more visceral response.

Today’s entry tackles the matter of foreknowledge from a different angle. It’s worth remembering that many people who went to the movies in the 1920s through the 1950s willingly subjected themselves to spoilers.

This is where we came in?

Chicago Daily Tribune (4 January 1948).

While the American studios developed their storytelling strategies in the 1920s and 1930s, movie exhibition became a big business. In 1935, eighty million Americans went to the movies every week. The historical high point was 1946-1948, when annual attendance hit 4.7 billion. But how did all those people see the movies? More specifically, did they watch them from start to finish?

We’re so used to showing up at a definite time for a screening that it’s hard to imagine a period when many viewers would simply drop in to what were called “continuous admissions” or “continuous performances.” In major cities, the film programs, complete with newsreels, cartoons, trailers, other shorts, and even a second feature, would run steadily with only brief intermissions. You could drop in any time.

When the houses filled up, prospective viewers would have to wait in line outside or in the lobby until someone left. Then an usher would show the next patron to the empty seat. Meyer Levin’s novel The Old Bunch describes a group of friends waiting forty-five minutes before just getting into the lobby of a Chicago theatre in the 1920s.

Some of the viewers would depart during the main or second feature. Naturally, the patrons admitted in medias res would see the end of a movie before they caught up with the beginning, perhaps some hours later. Hence the phrase, “This is where we came in,” meaning, “Now we’ve seen the whole picture and can leave.”

After Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema, a few readers asked why we hadn’t talked about continuous admissions. The practice would seem to explain a lot about the redundancy of Hollywood storytelling. Hyperexplicit exposition, the Rule of Three (say everything important thrice), and the habit characters have of reminding us of their relations to each other (“Gee! You’re the swellest sister a guy ever had!”)—all this would seem to be aimed at a viewer who might well have come in halfway through and need orienting to basic plot premises.

We knew about continuous performances, of course, but we didn’t discuss them because we could find no evidence that filmmakers took these conditions into account when designing their stories. In reading Hollywood screenplay manuals, technical journals, and the like, I didn’t find anyone commenting on the exhibition practice. My colleague Lea Jacobs, who has scanned Variety very comprehensively for the 1920s and 1930s, can recall no mentions of it affecting production policies.

When you think about it, screenwriters and directors couldn’t really do much to bring a latecomer up to date. You can’t keep reiterating story premises and recapitulating all that went before, and still move the plot forward. Better to tell the story straightforwardly and assume, as a default, that under ideal circumstances people would see the whole film from scene one onward. The same assumption governs TV writing, despite viewers’ channel surfing and foreplay with the remote.

Still, during the Golden Age of Hollywood a significant population consumed movies knowing how the story turned out before they saw the beginning. Ask people of my generation or older, and you’ll usually hear: “Oh, we went whenever we wanted. We never tried to find the showtimes.” My childhood moviegoing memories are dim, but I recall being dropped off at the Elmwood Theatre by my parents when they went to town. I’d go in during the movie (I do recall The Sad Sack, 1957) and watch until my mother or father fetched me out. It’s very likely that adults drifted in at odd times as well.

There’s harder evidence that some people preferred convenience to coherence. In 1950 Twentieth Century-Fox announced that All About Eve (1950) would be screened only in “scheduled performances.” No one would be seated after the film began. Premiering at Manhattan’s Roxy Theatre, Eve ran for a week under the new policy. It failed. People hadn’t heard about the new rules, showed up late, and weren’t admitted. The results were angry lines outside and empty seats within. The practice was halted and Eve screened in continuous performance. The Hollywood Reporter attributed the failure to “the public’s deeply ingrained habit of going to a movie show at any desired hour, when most convenient or on impulse.”

In other words, many people were encountering what we call spoilers all the time, and it didn’t seem to bother them. So you wonder: Is watching a movie straight through, as we mostly do today, a newer, more “disciplined” mode of consumption?

It’s showtime

Daisy Kenyon.

It’s obvious that the custom of just dropping in didn’t guarantee a nonlinear movie experience. With a double-bill house, even if you dropped in arbitrarily, you would see one feature or the other in a single gulp. And assuming a three-hour program and a 90- or 95-minute A picture, your odds of walking in during the shorts or the B film were about fifty-fifty.

But were people obliged to drop in willy-nilly? Could they have seen the movie straight through if they wanted to?

There’s considerable evidence that parts of the audience did want to see the movies in linear fashion.Consider the early attenders. And many cinemas filled up quickly just before the show started. Coming in when the theatre opened seems a fairly clear indication of wanting a linear experience. True, early attenders would probably have to sit through a newsreel, trailers, and other shorts, but many people enjoyed those too. Further, since double-bill houses screened the A picture first, knowing that custom could guide your decision about when to come in.

Could patrons have gained specific information about when the movies were screening? There’s a widespread belief that theatres didn’t publicize showtimes. But that’s not the case.

First, the box office almost always posted a schedule breaking down the program. Sometimes cardboard clocks with movable hands indicated showtimes. Patrons might see the schedule when they arrived, or while passing the theatre during the day. Knowing the schedule, you didn’t have to go straight in. If you bought your ticket while the feature was running, you could linger in the lobby. Probably some viewers were reluctant to enter if the feature they wanted to see was just ending.

Second, there were newspaper advertisements. This evidence is varied and intriguing, full of unexpected quirks. First, I took a look at late 1940s ads for the Elmwood, my hometown venue. These ads are mostly bare-bones. They list the movies, all double features, with three changes a week (films played Friday-Saturday, Sunday-Monday, and Tuesday-Thursday). The theatre doesn’t supply its phone number, probably because many families in our area didn’t have phones until the late 1950s. Showtimes are seldom mentioned. Doubtless townfolks knew by local custom what the showtimes were, and there was no need to advertise it in newspapers or handbills (which were still around in the 1950s). One September 1949 item specifies opening and closing hours:

Matinees Daily 2:00

Evenings 7:00 to 11:30

Sundays and Holidays Continuous 2:00 to 11:30

Knowing these hours of operation, people who wanted to see the movies straight through could show up at 2:00 or 7:00.

Knowing these hours of operation, people who wanted to see the movies straight through could show up at 2:00 or 7:00.

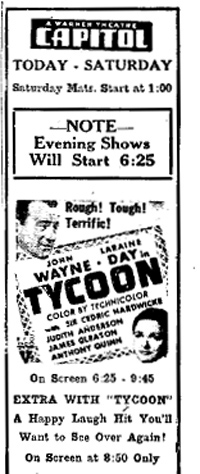

But some ads in other towns get a little more specific. “2 COMPLETE SHOWS 9:30 & 12 MIDNITE,” blares the Colonia of Norwich, New York in 1947. This indicates the starting times for the newsreel, cartoon, and ads, which all preceded the main feature. But since many theatres began their screening at 6:00, the accompanying ad from the Capitol, of Dunkirk, New York in 1948 seems to be saying that after all the shorts and ads, Tycoon hits the screen at 6:25. That movie ran a little over two hours, so there was time for filler leading up to the Happy Laugh Hit (presumably a revival). More unequivocal is the ad for Daisy Kenyon at the very top of this entry, which specifies when the feature starts. Again, the theatre probably opened at 1:00 and brought in the evening crowd at 7:00. That left fifteen minutes or so for pre-show material, including the color cartoon and “Global News”.

In short, some newspaper ads tell us only the theatre’s operating hours, while others specify showtimes. This sort of variation goes far back. The Olean (New York) Evening Herald advertised the Strand Theatre as “showing continuously 1 to 11 daily,” with no showtimes mentioned. On the same page we find specific starting times listed for a rival theatre’s showings of Fairbanks’Mark of Zorro (1921).

For special occasions, the scheduling could be quite exact. If you happened to be in Middletown, New York, on New Year’s Eve of 1947, you could welcome in “Kid 1948” at a gala show starting at 7:00 and ending “some time in 1948.” But not just “some time”: The State’s plan has a military precision.

Daisy Kenyon at 7:00 – 9:29 – 12:01

Comedy “Skooper Dooper” at 8:38 – 11:08

Terrytoon Cartoon “Silver Streak” at 9:12 – 11:42

Community Sing at 9:19 – 11:49

Latest Pathe News at 8:56 – 11:26

The ad goes on:

No seats reserved – No waiting in line. Come any time from 6:30 until 11:20 and see a complete show—Stay as long as you like! Come in one year—Leave the next!

The rival Goshen Theatre likewise provided a detailed schedule of its New Year’s Eve attractions, an astonishing four features plus cartoons. The show, broken into 9 “units,” started at 7:00 and ended at 1:00 in the morning, concluding with an “Exit March.” Why don’t movie theatres have exit marches any more?

Apart from ads specifying showtimes, we can glean other hints that at least some viewers preferred to know when to arrive to catch a film from the beginning. Some newspapers published lists of starting times. The New York Evening Post printed an extensive “Movie Clock” covering over eighty theatres. A Schenectady paper did the same thing under the rubric “Showing Today. What the Theatres Are Advertising.” You can find a similar feature in papers from Portland and Council Bluffs. Movie houses were often a small-town newspaper’s biggest and most reliable advertising source, so many editors were ready to oblige theatre managers.

Movie ads also sometimes included the theatre’s phone number, so people could call to check showtimes. Access to telephones was still spotty then; recall that the infamous Gallup Poll of 1948 misjudged Dewey’s chance for victory, partly by relying on phone surveys. But by 1945 there were about 16 million residential phones for a population of 140 million, so the middle-class people sought by exhibitors, then as now, might well be able to call up the movie house.

That is, in fact, what Daisy Kenyon does at one point in her movie. Having decided to go out with her girlfriend, she checks the phone number of the theatre she wants to visit and starts to call to check on showtimes. (She’s interrupted by a call from the mysterious Peter Lapham.) The scene seems to model one set of urban filmgoing habits.

Historian Douglas Gomery reminds us that there were many different sorts of theatres–first-run and subsequent-run, big downtown houses and neighborhood venues, rural ones, art houses, and so on. I’ve tried to capture some of this variety in my exploratory sample, but there are many fine-grained differences. Moreover, roadshow pictures often played to strict schedules, selling tickets for specific performances, and people adjusted their schedules to that regime for Gone with the Wind and other blockbusters. Perhaps the All About Eve fiasco came from people thinking this new film, in black-and-white and offered at regular admission prices, was not an event film like the usual roadshow attraction.

In all, it’s hard to generalize about viewing patterns. But it seems fair to say that in many circumstances viewers could, if they wanted, avoid seeing a movie’s ending before the beginning.

Which means that, then as now, we find different viewing styles. Today we have the Planners, who Tivo their cable television offerings, and the Grazers, who hop from channel to channel and watch in medias res. (We also have the Gleaners, who sample items at their leisure via the net. But there doesn’t seem to be an equivalent option in classic theatrical film viewing.) Several of Jim Emerson’s cinephile readers point out that they appreciate spoiler alerts in a web review because they want the choice between knowing and not knowing. It seems that in many circumstances movie houses offered 1940s viewers that same option.

Exhibition history is far from my specialty, so I’d welcome information from researchers who’ve studied this question more systematically. In the meantime, I’m grateful to Kristin, Ben Brewster, Lea Jacobs, Vance Kepley, Betty Kepley, John Huntington, and Virginia Wright Wexman for discussion with me. A special thanks to Douglas Gomery, who shared detailed information in emails and phone conversations.

For a comprehensive history, see Douglas Gomery, Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States (University of Wisconsin Press, 1992). See also Gregory A. Waller, Moviegoing in America: A Sourcebook in the History of Film Exhibition (Wiley-Blackwell, 2001) and Going to the Movies: Hollywood and the Social Experience of Cinema (University of Exeter Press, 2007), ed. Richard Maltby, Melvyn Stokes, and Robert C. Allen. Allen has mounted a beautiful online archive devoted to moviegoing in North Carolina.

A useful older source, though not focused on the 1940s, is Frank H. Ricketson, Jr., The Management of Motion Picture Theatres (McGraw-Hill, 1938). Ricketson advocates three hours as a maximum program time.

The motion picture theatre has a constant drop-in trade, and the patron who catches the feature after it has started does not want to sit through a seemingly endless program to see the part that he has missed. The tendency today is to present shows that are too long (p. 121).

It’s possible that as an employee of Fox Theatres, Ricketson was pushing the then-common industry view that double features were undesirable. Fewer films on the bill allowed more turnover during the day and favored the higher-profit A pictures.

Information about All About Eve‘s “scheduled performance” policy comes from the American Film Institute Catalog. See also “Business on ‘Eve’ at Roxy Jumps After Scheduled Showings Cut,” Boxoffice (28 October 1950), 50, available here. Linda Williams argues that Psycho‘s exhibition policy helped create the custom of consuming a movie straight through. See her “Discipline and Distraction: Psycho, Visual Culture, and Postmodern Cinema,” in “Culture” and the Problem of Disciplines, ed. John Carlos Rowe (Columbia University Press, 1998).

My analogy to standing on a precipice comes from Noël Carroll’s The Philosophy of Horror.

Two final points I couldn’t squeeze in elsewhere. First, to a large extent, spoilers are a function of different sorts of movie talk. In daily conversation, we’re reluctant to tell too much to friends who haven’t yet seen the film. Journalistic film reviewers seek not to reveal the ending, of course, but they’re also obliged to write about many scenes in an oblique way. (“After a string of preposterous coincidences…”) Net writers seem to model their comments on conversation and professional reviews, although some rascals delight in telling innocent readers everything that happens. We might call them spoilersports.

By contrast, academic writing assumes that the reader has seen the film, or is willing to let details be divulged for the sake of some larger point. Occasionally bloggers adhere to this standard. Readers of J. J. Murphy’s blog know that he doesn’t refrain from synposizing a plot to give depth to an analysis. I’ve done the same thing here on many occasions, but sometimes I feel the need to signal spoilers, particularly for current releases or films that depend on big twists. For some reason, I think that older films are fair game for full-blown discussion, even though many of our readers are less likely to have seen Enchantment than Source Code.

Second point, pure digression: In 1947, Richard Hull published Last First, a mystery novel dedicated “to those who habitually read the last chapter first.” The opening chapter does provide the story’s ending, but as you’d expect there’s a trick. The chapter is written so obliquely that you can’t really tell who is doing what to whom. At least I can’t.

P. S. 18 May 2012: Two more items that I’ve run across relevant to the this-is-where-we-came-in problem. First, this dialogue exchange from Ellery Queen’s serial-killer novel of 1949, Cat of Many Tails. The murder victim, one investigator says, “left for a neighborhood movie. Around nine o’clock.” The other asks, “Pretty late?” The reply: “She went just for the main feature.” This suggests that in Manhattan, it wouldn’t be impossible to know when the main feature played for the last time–either from the newspaper, from a phone call, or just from custom.

It seems that indeed late shows of the A picture were common. A 1939 Variety article, “‘Bad’ Scheduling Squawk” (27 December 1939, 5, 47) indicates that often the “No. 1 film” was put on at awkward hours, and viewers objected. “Too often, it is declared, a customer will call the theatre, only to learn the film he or she wants to see goes on at a time that interferes with dinner, or it’s on the last show, so late that getting out would be around midnight or thereabouts. Result, under theory, is that the customer doesn’t go at all.” Again, we find some evidence that the public could find out when a movie played by phoning, and that at least some patrons cared enough to see the picture through from the start. This piece from 1939 suggests that these options were available at least in some towns throughout the 1940s. Presumably, this practice was prominent in theatres not controlled by the studios, since the B picture was a flat-rate rental but the No. 1 feature was a percentage booking. The more tickets you could sell for the B, the bigger the exhibitor’s share of receipts.

P.S. 21 May 2012: The Wisconsin Project never sleeps. Alert Ph. D. researcher Andrea Comiskey sends me 1939 ads from the Olympia in Portsmouth, New Hampshire and the Fox in Billings, Montana. Both lists start times for both features, A and B, with the Fox including the start times for cartoons and newsreels too. The heading is, bluntly, “When to Come Today.” As per the above addendum, the Fox runs the A picture last, and quite late (around 10 PM).

P.P.S. 1 February 2021: Ran across this in John O’Hara’s novel Butterfield 8 (1935):

“What are we up to this afternoon?”

“Oh, whatever you like,” she said.

“I want to see ‘The Public Enemy.'”

“Oh, divine. James Cagney.”

“Oh, you like James Cagney?”

“Adore him.”

“Why?” he said.

“Oh, he’s so attractive. So tough. Why–I just thought of something.”

“What?”

“He’s–I hope you don’t mind this–but he’s a little like you.”

“Uh. Well, I’ll phone and see what time the main picture goes on.”

“Why?”

“Well, I’ve seen it and you haven’t, and I don’t want you to see the ending first.”

“Oh, I don’t mind.”

“I’ll remind you of that after you’ve seen the picture.”

Daisy Kenyon. Daisy and her friend, tracked by Peter and watched by a waiter, have apparently gone to a revival house–and one not playing pictures from Fox, the studio behind Daisy.