Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

Puppetry and ventriloquism

“I thought they burned that.” Hellzapoppin (1941).

DB here:

Coming back from my five-week stay in Europe (known in the Midwest as Yurrrp), I watched two releases I’d missed in the spring. Neither one was of outstanding quality, to put it mildly, and both were limited by “having been formatted to fit” the 4 x 3 airplane screen. Still, I was struck by how much both were like the 1940s movies I’d just been talking about with eighty participants in the Antwerp Zomerfilmcollege.

Of course the films’ look and feel were quite different, with Bouncycam and fast cutting instead of the rock-steady compositions and more sedate pace of the 40s films. But since I’d been concentrating on narrative matters, both of the recent releases chimed with my concerns in the course.

For one thing, both relied on flashbacks. Battle: Los Angeles used the technique casually. After a brief prologue showing our squad in a helicopter heading into a firefight, we get a title, “Enemy contact minus 24 hours.” This takes us back to the previous day, when the aliens’ attack seemed merely a meteor shower. We get to meet the Marines’ team in the usual vignettes of guys buddying around, planning their futures (one grunt is getting married soon), and nursing their woes (ageing, or mourning a slain brother). Why couldn’t these twenty minutes of exposition be given at the outset? Do the makers think we’re too impatient to wait for the first alien onslaught? Do they think we don’t know that the whole premise of the movie is an interplanetary assault on LA? In any case, the flashback is over by the sacred 25-minute mark, and we’re plunged into the ongoing action, starting with the team’s effort to save some civilians trapped in the combat zone.

Limitless used a more extended flashback. It follows what I called in Antwerp the “crisis” architecture, whereby the plot begins at or near the action’s climax and then moves back to the point at which the main story action begins. A prototype of the structure is The Big Clock (1948). Accordingly, Limitless opens with the protagonist about to leap off a high-rise terrace while his enemies pound at the door of his apartment. Then we return to his origins as a grungy wannabe writer, and the bulk of the film moves toward the critical point shown in the opening.

Limitless also reminded me of the 1940s’ penchant for rendering character psychology through subjective film techniques. After Eddie Morra takes the mind-enhancing drug, his world becomes distorted and we get unusual angles on him.

But Eddie’s head trips have precedents in the frenzied dream sequence of an early film noir like The Stranger on the Third Floor (1940). A frantic rehearsal montage in Blues in the Night(1941), with its shots from the “viewpoint” of a piano keyboard, pushes the pictorial envelope further than the comparable shot in Limitless.

Today’s digital technologies make it easier to go for extreme effects, but wild imagery is nothing new, especially when it’s motivated as representing extreme subjective states.

Of course flashy storytelling, including time-juggling and subjective images and sounds, can be found in cinema before the 1940s. But in that era they became more prevalent, in effect a “new normal.” And very quickly filmmakers sought to push them further, with results that linger today. In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I try to argue that the flagrant artifice of 1940s films was revived in the 1990s and 2000s. Citizen Kane is in a way the ultimate “puzzle film,” with one clue to the meaning of Rosebud tucked away in a minor set. The narrative gymnastics of The Hudsucker Proxy, Pulp Fiction, Memento, The Matrix, Inception, Shutter Island, and many other movies hark back to the revisions of storytelling traditions that crystallized fifty years earlier.

Unelected affinities

It’s not just that the two airborne movies chimed with what I’d been screening. Anyone who teaches art or literature is familiar with what we might call the cluster-surprise effect. When you assemble a batch of books or plays or films to make up a semester course, you start to notice affinities you wouldn’t have spotted if the artworks hadn’t been set side by side.

To a greater degree than usual, cluster surprises arose within the movies I screened for the Belgian Zomerfilmcollege. I’ve participated in these summer movie camps before, but seldom have I had such a sense of interconnections among the films we watched. It’s as if the makers were talking to each other, or at least looking over their shoulders at what their compadres were up to.

To some extent, convergence was to be expected. The films were picked to illustrate storytelling innovations in 1940s Hollywood films, so that guaranteed some overlap. Moreover, I’ve elsewhere suggested that filmmakers are making movies as much for each other as they are for the general public. My most recent instance was in a peculiarly recurring ad for ale.

So I probably shouldn’t have been as surprised as I was. Still, I was initially ready to notice changes within individual directors’ outputs, such as Welles’ development from the quietly controlled pressure of The Magnificent Ambersons to the narrative fireworks of The Lady from Shanghai. What I didn’t expect was the crosstalk among Ford, Mankiewicz, and Siodmak in their handling of flashbacks, or the way that the elegant methods of characterization found in A Letter to Three Wives set off the opacity and contradictory behaviors of the love triangle in Daisy Kenyon.

I need to think more about how the films we screened, plus the hundred or so others I’ve been watching in the spring and summer, can illuminate our understanding of creative choices facing filmmakers then (and today). Some of this thinking will eventually surface in more extended writing, I hope. For now, here are three ideas about 1940s storytelling, sparked by the sheer juxtaposition of interesting movies.

Of course there are spoilers. The films most vulnerable to spoilage are Laura, The Killers, All About Eve, and Sunset Blvd. Maybe you can use your parafoveal abilities to skip the passages that deal with ones you haven’t seen.

Art as artifice

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942).

The 1940s highlight a basic feature of Hollywood cinema, and indeed most popular traditions I know. Artifice, often self-conscious artifice, usually rules. It’s most evident in crazy comedy (see way up top), but even dramas seldom yield what people usually think of as realism.

Imagine a continuum between surveillance-camera video at one extreme and ballet or commedia dell’arte at the other. Hollywood lies much closer to the stylized side than to the documentary-recording side. This tradition is heir to a host of conventions derived from painting, drama, vaudeville, opera and operetta, prose fiction, and, by the 1940s, radio. All of the resources of these arts are brought together for the sake of telling a compelling, moving story, and anything that works is fair game.

Take one technique that became robust in the 1940s, the voice-over narrator. Some theorists claim that every narrative must have not only a narrator but a “narratee,” somebody who is listening to the story being told. Yet in most situations we haven’t the foggiest idea who the narratee would be.

At the start of The Magnificent Ambersons, Welles’ ripe baritone tells us things about the town, the family, and long-gone fashions. At the start of All About Eve (1950), the urbane Addison DeWitt promises to give us the dirt on the young woman’s rise to stardom. The cases are significantly different. Welles creates what we might call an external narrator, one who isn’t participating in the events we witness. Addison is a character narrator, one who exists within the story and plays a role in the action. In either case, though, we can ask: To whom is the narrator speaking?

Addison isn’t addressing other characters, even in retrospect; we never see anyone listening to his tale. Welles’ voice-over narrator can’t be addressing the characters because he isn’t in the story world at all. So who’s listening? Before you say, “Well, they’re addressing us, the audience,” remember that both these narrators are fictional beings. They don’t exist in our world and we don’t exist in theirs. In daily life, if you said your nonexistent friend told you of his adventures, we’d tend to wonder about you, and we’d certainly place little credence in the events reported.

In art, though, no problem. It’s simply a convention—a piece of artifice—that lets us accept the voice-over as a mimicry of a conversational situation (a person speaking to another) and delete the part that assumes a tangible listener. So the commonsense answer is right. These narrators are speaking to us. In fact, everything in a fiction film is addressed to us. If you want an ontologically tidy answer: The actual filmmakers are the storytellers, the actual viewers are the audience, and everything else is smoke and mirrors, or puppetry and ventriloquism.

You can put it more generally. As often happens, the movie summons up a familiar schema from ordinary life, the conversation, but revises it for artistic purposes. The film draws on certain features of reality but deletes others, retaining just enough salient bits to prompt our understanding. Filmmakers can assemble, in the manner of collage, pieces of standard social interactions for particular effects. Our response depends on the patterns that are formed, not on the reality status of the bits or of what is left out. We concentrate on the effect, not the means used to trigger it.

The same thing goes for the narrator’s range of knowledge. In literature, the “I” narrator typically cannot report things she doesn’t know about. If something happens that she couldn’t witness at the time, she’s obliged to explain how she learned about it subsequently. But internal filmic narrators often lead us into moments, or entire sequences, that they weren’t present to witness. In The Killers (1946), Nick Adams tells the insurance investigator Riordan that Ole the Swede encountered a mysterious man from his past, but given Nick’s position at the rear of the car, paying no attention to the encounter, he couldn’t have observed the way Ole intently avoids meeting the driver’s eyes.

Huw, the narrator of How Green Was My Valley (1941), didn’t see, and may not have known about, his sister Angharad’s visit to Reverend Gruffyd.

Yet the scene, played out between the two near-lovers, is given to us within the narration established as Huw’s.

By convention, then, filmic narration allows a lot of leeway to a character narrator. Again, a realistic situation, someone reporting on what they know, is treated in a partial, stylized fashion for the sake of sharpening the effect. We’re more curious after noticing the driver’s frowning look at Ole, whether or not Nick could have strictly seen it. We’re more intensely involved with the emotion of the Angharad/ Gruffyd romance than if we simply saw Huw learning about her visit later.

Proteus in Hollywood

Once a convention is put in place, somebody is bound to play with it. A one-off example occurs in Ambersons, when we get this exchange on the soundtrack:

Gossip: They’ll have the worst spoiled lot of children this town will ever see.

. . . .

Narrator: The prophetess proved to be mistaken in a single detail merely. Wilbur and Isabel did not have children. They had only one.

Gossip: Only one! But I’d like to know if he isn’t spoiled enough for a whole carload.

(Interestingly, Welles doesn’t present this exchange in his 1938 radio version of the novel.) Likewise, the opening of Eve is trickier than I indicated, partly because Addison’s narration is accompanied by a freeze-frame at the moment the award is presented.

Since a few years before this, It’s a Wonderful Life (1947) showed angels freezing time and commenting on George Bailey’s dreams, you have to wonder if Mankiewicz isn’t endowing Addison with a supernatural power.

Addison will, by the end of the film, be utterly in control of Eve.

The 1940s and early 1950s see an immense amount of experimentation with narrators. Narrators can lie about what they report. They can be dead (Scared to Death, 1947; Sunset Blvd, 1950), otherworldly (the angels in It’s a Wonderful Life), non-human (the house in Enchantment, 1948), or of uncertain status (Woman in Hiding, 1950).

A good example of the high artifice of the period comes in Laura (1944). The film is introduced by Waldo Lydecker’s voice-over, remembering “the weekend Laura died,” and remarking on the detective Mark McPherson, wandering through Waldo’s art collection. Waldo’s voice-over, describing events in the past, might seem to assure us that he survives the ensuing story.

Fairly soon Waldo’s voice-over reappears, but it doesn’t frame the overall fiction. As he explains his relationship with Laura to McPherson, we get episodic flashbacks showing Laura’s rise (and, true to form, including events Waldo couldn’t have known about). At the end of their evening together, the film’s narrational weight shifts visibly to Mark, showing him in an uncharacteristically tight close-up watching Waldo depart.

The absorption of Waldo’s voice into the overall texture of Mark’s investigation invites us to forget that Waldo initiated the film, and that he in fact fed us false information. (Laura didn’t die that weekend.) So the ending, in which Waldo falls before policemen’s pistol blasts, comes as a new surprise. The camera tracks away from him murmuring, “Goodbye, Laura”, past Laura and Mark, to the shattered clock face that recalls what Waldo’s shotgun did to Laura’s surrogate.

Over this image we hear Waldo’s voice: “Good night, my love.” From one angle, the line could be considered Waldo’s offscreen dying words, continuing his murmured farewell to Laura. Yet the last line is closely miked in the manner of the opening voice-over, suggesting a voice from beyond the grave. Was Waldo narrating the first scene from the same place? Is this a tale told by a corpse? The ending is equivocal, hovering between the two possibilities.

Again and again, the films we saw fractured tidy patterning. Addison’s voice-over narration in All About Eve gives way to that of another character, Karen Richards. After he glances at her, a cut presents her voice-over taking up the burden of introducing us to the young Eve in a flashback.

How to explain this tag-teaming, except as pure artifice, a new wrinkle in a convention that by 1950 had become second nature to filmmakers and viewers?

In The Killers, the dying crook Blinky is questioned by two investigators. No problem about narratees here; he speaks to them. But the film makes a new problem for itself. Blinky is too far gone to respond to questions. All he can do is mutter phrases from the past. Yet the film’s narration dramatizes his ravings, presenting the scene he invokes as fully as any other.

Is this what his listeners are imagining? No; it’s just a stretching of the conventions surrounding the character narrator. After several orthodox voice-overs earlier in the movie, we can assume that Blinky’s babble will be translated into solid scenes, as more articulate talk has been earlier. Again, plausibility is flagrantly violated; who could construct a coherent set of actions, let alone a legal case, out of fragmentary phrases? But who cares? Blinky is a device to get us into the past, and the filmmakers assume that we’ll follow the most slender lead they offer.

Meir Sternberg has articulated a powerful case that there are no “package deals” in verbal art. Any narrative or stylistic device can fulfill a wide range of functions, and any functions can (with sufficient motivation) find expression in many different techniques. To take a filmic example, a dissolve can indicate a passage of time, but sometimes a dissolve (say from a long-shot to a closer view of a character) suggests continuous duration. And a cut may indicate continuous time, but it can also indicate that a stretch of time has been skipped over, as throughout Resnais’ Muriel. Sternberg calls this the Proteus Principle, “the endless interplay between form and function.”

Along these lines, conventions within a tradition can be seen as the most probable fit between form and function, the ones we expect because we’ve seen them in other films. In studio-era Hollywood film, dissolves usually signal a passage of time, and cuts within scenes usually indicate continuity. But those functions are local and subject to revision. Likewise, a voice-over narrator is unlikely to talk with the characters, except in the case of comedy. For Welles to try it in a drama was a bit daring, but it simply shows that there is room, if the filmmaker proceeds carefully, to stretch the convention. (It had already been stretched in both the play and film versions of Our Town.)

Collaborative competition

How to explain these fractures of form? Invoking a Zeitgeist explanation—wartime trauma, postwar dislocation—seems to me a desperate measure, for reasons I’ve outlined elsewhere. In the Antwerp sessions, I suggested some other explanations, which I hope to justify at greater length another time. For now, let me propose just one factor that seems to me to have contributed to the wilder side of 1940s storytelling.

The famous opening of E. H. Gombrich’s Story of Art—“There really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists”—is open to many interpretations. One is that art history is driven by the human dispositions of the image-makers. Those dispositions include rivalry. In his 1974 essay “The Logic of Vanity Fair,” Gombrich further explores the role of competition among artists. In many traditions, they may try to raise the stakes, seeking to outdo others in virtuosity. I’d add that such artists either try to beat their predecessors and contemporaries at their own game, or to invent a game in which a newcomer can excel. Later in his career Gombrich suggested an analogy to ecology: some artists fight for the same niches, others adapt themselves to unexploited ones.

From this standpoint, I’d suggest that a close-knit world like Hollywood encouraged competition among its creators. In the period I’m concerned with, some ambitious Hollywood filmmakers (not only screenwriters but also directors, cinematographers, and their colleagues) saw voice-over narration as an opportunity to innovate. The technique may have arisen partly because people were used to it from radio, and it offered advantages in efficiency and low cost. Detour (1945) shows that a fairly static, cheaply shot scene can be energized by extensive voice-over. Ambitious filmmakers could make this still-emerging technique more forceful, more mysterious, more evocative. The cost of this effort was some violation of realism and an occasional violation of tidy form.

In just a few years, we go from Welles’ external narrator being sassed by a gossip to Mankiewicz’s character narrator passing the expository ball to another character. We see a community of creators pushing each other to revise a schema they inherited, to test its limits and find new effects it could create. I think that this “collaborative competition” operates in other innovations of the period, such as the long take, the flashback, deep-focus cinematography, and sound manipulations.

Something like this creative community still exists. Urges to compete through innovation (or to revive older conventions) seem to drive some of our filmmakers. The impulses assume a feeble form in Limitless and Battle: Los Angeles, but at least these program pictures remind us that competition isn’t only financial; it’s also artistic. The pressure to come up with a fresh revision of a familiar schema is, if anything, keener today than in the 1940s. Insidious has to top Paranormal Activity, which itself revised a traditional formula in fresh ways.

The snag is to do something that we haven’t seen before. That’s tough when you come at the end of the line that includes filmmakers like Ford, Hitchcock, and so many others. This is the problem of belatedness, and some day it will get a whole entry of its own.

Two especially strong books on Hollywood cinema of the 1940s are Thomas Schatz’s Boom and Bust: American Cinema in the 1940s (University of California Press, 1997) and Dana Polan’s Power and Paranoia: History, Narrative, and the American Cinema, 1940-1950 (Columbia University Press, 1986). By presenting a detailed overview of industrial developments, Schatz supplies a vivid context for studying artistic trends. Polan, focusing on an immense range of films, aims to explain their formal and thematic qualities from a broadly Foucauldian perspective. Here “discourse” assumes an immense power over the way the films look and sound, and the motive force behind the discourse is largely, though sometimes obliquely, World War II.

In addition, I should pay tribute to Sarah Kozloff’s fine Invisible Storytellers: Voice-Over Narration in American Fiction Film (University of California Press, 1988). Kozloff includes concise, sensitive analyses of How Green Was My Valley and the opening of All About Eve. For the latter film, she traces Addison’s narrational power in some detail. Needless to say, my thinking has also been influenced by Kristin’s essays on Laura and Stage Fright, to be found in her collection Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis (Princeton University Press, 1988).

For more information about Mankiewicz’s plans for All About Eve, including a scene replaying earlier action with different significance, see Gary Carey, More about All About Eve (Random House, 1972), 56-58. According to Carey, Mankiewicz shot this and other material that was excised in the editing stage. The version of the screenplay printed in Carey’s book clearly isn’t the shooting script (it seems to be close to a transcript of the finished film), and it does contain the passages I’ve considered: the freeze-frame (p. 127) and the moment in which the narrational voice slips from Addison to Karen (p. 128). This published version is widely available online in various formats; the typescript copy available here carries the tag “Shooting Draft” and doesn’t contain the scenes that Carey claims were dropped in postproduction.

My quotation from Meir Sternberg comes from “Narrativity: From Objectivist to Functional Paradigm,” Poetics Today 31, 2 (Fall 2010), 594. Gombrich’s essay, “The Logic of Vanity Fair: Alternatives to Historicism in the Study of Fashions, Style and Taste,” appears in his collection Ideals and Idols: Essays on Values in History and in Art (Phaidon, 1979), 60-92.

In my Antwerp talks I approached questions of form and style in the 1940s by trying to reconstruct the creative problems and solutions arising within the filmmaking community. For me, filmmakers working within institutions are the most proximate agents of stability and change. For examples of this approach, see my chapters of The Classical Hollywood Cinema, The Way Hollywood Tells It (which considers the problem of belatedness), and my analysis of Mildred Pierce in Poetics of Cinema. My critique of Zeitgeist or mood-of-the-moment explanations can be found in Poetics of Cinema, 30-32.

You can sample how I’ve tried this approach out in pieces on this site. For instance, this entry examines artistic competition through the example of high-school lipdubs, this one talks about our appetite for artifice, and this one discusses how Cloverfield solves the problem of point of view in a monster movie. This essay on actors’ eye behavior develops the idea that filmic conventions often remake, in streamlined form, familiar aspects of social interaction. I hope to develop my case for the 1940s more thoroughly at some future point.

Zomerfilmcollege, Antwerp (July 2011). For more on this event, see earlier entries here and here.

Pike’s peek

The Lady Eve.

DB here:

Hollywood is supposedly making movies for mass audiences, and up to a point that’s true. But there’s an in-group aspect of Hollywood as well. There are moments in the movies when the writers and directors and actors seem to be talking more among themselves than to outsiders. We’re probably more familiar with this nowadays, as when Tarantino and Soderbergh cast Michael Keaton as the same character in both Jackie Brown and Out of Sight. Not only does the gesture suggest solidarity between two directors of roughly the same generation. I think it’s also a sign that the directors respect Elmore Leonard’s concern to let a character from one novel pop up in another.

You see the same attitude in those in-jokes we occasionally find in Hollywood movies. The most famous, I suppose, is Cary Grant’s warning, in His Girl Friday, that the last man who thought he’d beaten him was Archie Leach, “just a week before he cut his throat.” Archie Leach was of course Grant’s real name. In the same film, Grant as Walter Burns tells the platinum blonde Angie to seduce Bruce Baldwin. How will she know him? He looks like that fella in the movies, he says, “You know, Ralph Bellamy.” Angie replies with simple lack of interest, “Oh, him?” Since Bruce is played by Bellamy, this is a little cruel; both character and actor are treated as losers.

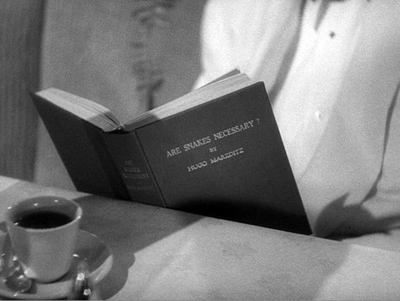

Preston Sturges liked such playfulness, as when in The Lady Eve (1941) he used his birthday as the date on a check. In the same movie, the protagonist reads a book called Are Snakes Necessary?

No such book exists, more’s the pity. The title pays comic reference to James Thurber’s 1929 best-selling satire on marriage manuals, Is Sex Necessary? and confirms the snake-as-phallus imagery that isn’t exactly underplayed in the rest of the film. Sturges revisited the gag phrase when he proposed Is Marriage Necessary? as the title for a later picture. Unsurprisingly, it didn’t pass the censor, and instead we got a more anodyne title, The Palm Beach Story (1942).

These are comedies, though. On Saturday night, I saw an instance of in-group crosstalk where I hadn’t expected it. The Long Night (1947) is Anatol Litvak’s somber remake of Le Jour se lève. Unlike Hawks and Sturges, Litvak wasn’t exactly known for cockeyed humor, nor was screenwriter John Wexley (The Roaring Twenties, City for Conquest, Hangmen Also Die!). Yet in one shot, there it was, a citation as plain as a pikestaff.

Over several years I’ve been gathering material for a blog or web essay on product placement. (I’m mostly in favor of it.) So I tend to scrounge around among hand props and other bits of flotsam in the frame, hoping to catch a brand name. Usually this task-driven visual search comes to naught, but The Long Night paid me back.

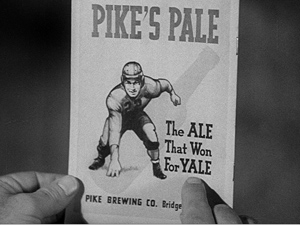

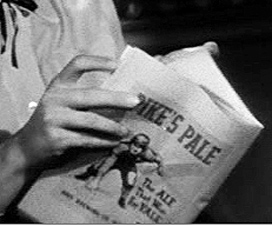

In Sturges’ The Lady Eve, you’ll remember, Henry Fonda plays Charles Poncefort Pike, heir to the vast fortune of the Pike brewery. The firm’s success rests upon Pike’s Pale Ale. A flyer for the product convinces Jean and her father that Charles should be the target of their next con job.

Pike’s Pale and its tagline run through the movie as a comic motif. But no such product then existed. It features on a list of fake movie products in a 2006 New York Times story.

All the more surprising, then, is a scene in The Long Night six years later. The rapacious magician Maximilian (Vincent Price) takes Joanne (Barbara Bel Geddes) to a symphony concert. She reads the program avidly, and on the back we can glimpse a familiar brand.

The advertisement even features the same text and layout as the flyer in Sturges’ film.

If it’s an in-joke à la His Girl Friday, what’s the punchline? And how did it even get there? We have two different studios (Paramount, RKO) and different genres (satiric romantic comedy, gloomy romantic drama). Was the ad just lying around a props warehouse? Did Fonda, who plays the hero of The Long Night, keep the flyer as a souvenir of The Lady Eve and ask the producers to include it as a shout-out to Sturges? Was there a company specializing in making printed props for the studios and here it just recycled something it had done for Paramount? Or is it just a case of Hollywood gratuitously referencing itself?

I’d be eager to hear from anybody who knows or has an educated guess. In the meantime, I’ll keep scanning frames, and being diverted by the ways that the Hollywood In-Crowd creates a world of off-center echoes and cross-references. It’s as if movies fertilized each other, but promiscuously, creating an eccentric world behind the screen, where stray images and lines of dialogue jostle against one another. Of one thing we can be sure: It will be unpredictable.

Today there is a real Pike’s Pale Ale. The proprietors of Seattle’s Pike Brewing company didn’t know about The Lady Eve when they conjured up their brew. I’ve never tasted it, but you might count this a case of blog product placement. Mmmmm, pale ale….

Ian Patrick displays an imaginative gouache called “Are Snakes Necessary?” here.

Incidentally, The Long Night is another of those 1940s movies with a flashback within a flashback, of the sort I considered in an earlier post.

I top and tail the entry with pictures of Slim because he looks swell when he’s thinking.

The Long Night.

PS 19 June: Rapid Response Dept: Alert reader Sean Weitner points out the reappearance of the same newspaper page in a bevy of TV shows. The evidence is here. Thanks to Sean!

PPS 21 June: More bulletins from alert readers. Leo Rubinkowski points out the source of the recurring newspage on Slate here. This wouldn’t, I think, explain the reappearance of Pike’s Pale, but maybe…. Andrea Comiskey has found that Douglas Sirk was apparently fond of certain foil-etched items. The films are All That Heaven Allows and Written on the Wind, and the pix are here and here and here and here. Leo and Andrea are UW grad students, so I’m especially happy to thank them.

Julie, Julia, & the house that talked

Enchantment.

DB here:

For the last couple of decades, American filmmakers have been exploring storytelling options that break up timelines. Flashbacks are the most obvious examples, but so too are time-travel and parallel-universe stories; Source Code was a recent example, which I talked about here. Elsewhere I’ve mentioned that these new formats revive narrative innovations that we find in 1940s Hollywood movies—the topic of my course at the Zomerfilmcollege in Antwerp in July. While planning that course, I’ve come up with an intriguing pair of movies that can tell us something about how the romance film, drama or comedy, handles a couple of features of storytelling we probably don’t think enough about.

When parallel lines meet

Julie & Julia.

What is a story made of? Minimally, characters and their doings. Some theorists of narrative offer a more abstract description. Stories, they say, consist of agents (characters) who exist in states of affairs (John was married to Mary) and who perform actions (John tried to divorce Mary). Still talking abstractly, a narrative organizes the agents’ states of affairs and actions according to certain principles.

Principles of time, indicating sequence and duration. John married Mary, then after a while he tried to divorce her. Some theorists think that ordering events and states of affairs in time is the essential feature of narrative.

Principles of causality. John is tried to divorce Mary because he fell in love with Audrey. Perhaps not all narratives exhibit causality, but most surely do.

Principles of space, a place in which the story unfolds. John met Mary at the supermarket and they fell in love at the beach, but at work one day John was introduced to Audrey, the new head of his department and they had coffee at Starbucks…. Some stories rely on a very specific sense of locale (e.g., a tale of a man buried alive), while others evoke the environment rather vaguely (as in jokes beginning with a priest, a rabbi, and a minister walking into a bar).

These core ingredients look very general, but they can be good guides in starting to analyze a story. We can ask how time is organized, what causes what to happen, and how space is patterned, and the answers can reveal intriguing things about the way the narrative works.

There’s one more principle worth remembering. Most narratives involve parallelism. That occurs when characters, situations, actions, or other factors are likened to or contrasted with one another. (I don’t say “compared or contrasted” because “comparison” means pointing out both likenesses and differences. Call me fussy.) So our hypothetical tale might include another man, John’s friend Jack, who lives a happy married life with Jill. In fact, romantic comedies often include subplots, as when we get a secondary love affair between friends of the main couple. Serendipity, discussed in another blog entry, is a straightforward instance.

Sometimes a filmmaker can create an entire plot out of parallels. Griffith did it in Intolerance, drawing comparisons among different historical epochs. More common is the film that gives two or three protagonists equal weight and likens or contrasts their situations. In Wedding Crashers, John’s romantic pursuit of a woman is counterpointed with the raunchier efforts of Jeremy to escape a woman pursuing him. Kristin has proposed that some plots create “parallel protagonists” who pursue separate goals but converge because one of them tries to meet the other, as in Desperately Seeking Susan and The Hunt for Red October. And in what Variety calls “criss-crossers,” or what I call “network narratives,” many characters become fairly salient as they intersect, and each can be compared to another. Examples would be Grand Hotel, Tales of Manhattan, and Love, Actually, which depend largely on contrasts.

Kitchen stories

Julie & Julia.

So parallelism can operate at greater or lesser strength, as a minor accessory to the flow of time, causality, and space; or it can become a firmer principle shaping the story.

This sort of firming up is visible in Nora Ephron’s Julie & Julia. We have two sets of characters in two time frames: Julia and her husband Paul in the late 1940s and 1950s, and Julie and her husband Eric in the early 2000s. The two stories are crosscut, so that we alternate between them as each one develops.

What links them? Most explicitly, some causal factors. Julie is dissatisfied with her thankless job. Since she loves to cook, she decides to devote a year to trying all the recipes in Julia Child’s famous Mastering the Art of French Cooking. At Eric’s suggestion she writes a blog chronicling her daily efforts, and gradually she finds an audience, eventually making her a celebrity. So Julia’s cookbook becomes a central cause in changing Julie’s life.

What about Julia? In her postwar plotline, she is also unfulfilled in her career, but she loves to eat. She learns French cuisine and revels in creating elaborate dishes. At the urging of Paul, she collaborates with two friends in writing, and eventually publishing, a cookbook for “servantless” American housewives. So Julia’s efforts are presented as another chain of cause and effect.

The parallels are obvious. Both women turn to cooking in search of personal fulfillment. Both take up writing, to share their knowledge and experiences with others, and both become published authors. Both have supportive husbands who inspire them. The film is about love, but each couple’s bond isn’t threatened by an outside figure, as in other romance films. Their bond is strengthened by the love of food, not to mention good-hearted sex.

Some more detailed parallels emerge as well. There are spatial contrasts: Julia is exhilarated by Paris and their lush apartment, while Julie’s depression is deepened by their cramped Queens walkup, perched above a pizza joint. Both Julie and Julia encounter initial disappointment in their efforts to reach an audience. Julie’s blog initially finds only her mother as a reader, while Julia’s manuscript is at first turned down by publishers.

Both couples enjoy sharing their food with friends, although Julie’s college pals, now self-centered businesswomen, aren’t as supportive as Julia’s writing partners. Both couples undergo a strain, with Paul being interrogated by McCarthyite politicians and Eric made annoyed by Julie’s growing obsession with Julia and the blog’s readership. Even specific motifs, like butter, lobsters, and boning a duck, draw out parallels between the two heroines. Montage sequences highlight the linkages, as when pairs of shots show both women cooking and tasting the same dishes.

Julie in fact becomes what Kristin in Storytelling in the New Hollywood calls a parallel protagonist. Often in such plots, one protagonist becomes fascinated with the other, as Salieri gets obsessed by Mozart in Amadeus. Julie is captivated by Julia’s charisma, to the point of wearing her signature pearl necklace.

Julie and Julia never meet; it’s hinted that in her old age Julia is miffed by Julie’s blog. Yet the plotlines meet in a spatial parallel. Julie and Eric visit the Smithsonian reconstruction of Julia’s kitchen. He takes a picture of it.

After they’ve left, the display shifts into an image of the original kitchen, where Julia and Paul get the news that her book has been printed. The scene finally conjoins the couples and reaffirms each woman’s success and each man’s pleasure in it.

Two times in one space

Two times blend within a single domestic space in another movie built out of parallels, Irving Reis’s Enchantment (1948). Again the action plays out in different eras: a turn-of-the century story of love and jealousy within the Dane family, and tale of awkward courtship set during the blitz.

In the first story, the widower John Dane adopts an orphan girl, Lark. After his death, the eldest daughter Selina rules the house, coddling her brothers Pelham and Rollo but treating Lark like a servant. Once they have grown, both men come to love Lark (Teresa Wright), and she reciprocates with love for Rollo (David Niven). Selina blocks their union through several stratagems, relying partly on Rollo’s reluctance to challenge her, and Lark leaves to marry an Italian count. She becomes the great lost love of Rollo’s life.

An old bachelor, Rollo lives in the family home until his grandniece Grizel (Evelyn Keyes) arrives from America, posted to help the British war effort. Grumbling at first, Rollo eventually comes to enjoy having her in the house, especially when Grizel attracts the attentions of a Canadian flyer, Pax (Farley Grainger). She fends him off, on the grounds that she’s already been hurt in love once and doesn’t want to risk it again. At the climax, as a bombardment begins, Rollo urges Grizel to go to Pax. He says, acknowledging his wasted life, that if she loves him, she can’t wait a moment; things can change in an instant.

In effect, Rollo acknowledges the parallels between the two generations, seeing Grizel on the verge of making his mistake. “Don’t stop to bargain for happiness.” Grizel races out and finds Pax as the bombs fall. She achieves the happiness that Rollo foolishly lost. Back at the house, Rollo is killed when a bomb strikes the house.

I’ve presented the two plotlines sequentially, but like Julie & Julia, the film alternates them, treating the distant past as flashbacks from the wartime drama. Like Ephron’s film, Enchantment puts the climaxes side by side. The big scene of Rollo’s losing Lark to the count is followed immediately by the climax in the present, when Pax declares his love, Rollo advises Grizel to follow him, and the house is damaged, though not destroyed, by the bombardment. Again, there is a basic causal link between the eras, this time based on kinship: because Grizel is a relation she bivouacs with old Rollo. The parallels are likewise highlighted by motifs, not least the necklace that Rollo gave Lark as a pledge of love. She returned it as she departed, but after he has come to love his great-niece, he gives it to her as a token of her happiness. “She wore it one night. You’ll wear it a lifetime.”

Enchantment is based on a novel by Rumer Godden, probably best known to cinephiles as the author of Black Narcissus and The River, both turned into extraordinary films. The novel, Take Three Tenses: A Fugue in Time (1945), has a more complicated parallel structure than Reis’s film. It creates several time zones: the marriage of Dane senior and his frail wife Griselda; the growth of their children; their young adulthood; and the blitzkrieg period we see in the film. In addition, as perhaps a redundancy device, the central male is given a different name at different stages: Rolly as a child, Rollo as a young man, and Rolls as an old man.

Enchantment is more conventionally focused. Griselda is a central character in the book, but the film drops her and picks up the family saga after her death. Even then, it devotes only four short scenes to the childhood of the siblings. The result is to concentrate on the youthful Rollo-Lark romance, but it loses a string of parallels involving courtship and marriage, particularly the contrast between Grizelda and her modern namesake.

In a mildly experimental gesture characteristic of much popular fiction of the forties, Godden’s novel treats time in an unusual way. The World War II scenes are given in the past tense, but all the earlier periods are rendered in the present tense. So you get passages that mix different eras.

Proutie took it up to Rolls in his dressing room, where Rolls was sitting.

“The post, Mr. Rolls.”

“Go away,” said Rolls. “Leave me alone.”

Proutie put the letter on the table at Rolls’ elbow and went away.

Years before there is another letter, a letter written by Rolls in answer to many letters of Selina’s.

She reads it in her room sitting in the blue-and-white armchair on which this afternoon, dressing to have tea with Pax, after she had been asleep, Grizel tossed down her pyjamas and left, standing by it on the rug, a pair or swansdown slippers that she called her “scuffs.”

Selina as a girl has a swansdown muff, dyed violet with a rose in it, but she keeps it tidily in tissue paper in the cupboard; she does not throw her things about nor leave them on the floor. As she reads Rolls’s letter, Selina is not a girl; she is an elderly woman and that day she feels old. You ask me, Lena, why I don’t come home. That is a question that is rather difficult to answer. I seem to have a distaste for the house.

Call it dumbed-down Proust or Faulkner if you want. In any case, the fluid shifts from past to present are given not only through adjustments of tense but also by emblematic objects, like the letters and the swansdown accessories, that lead us, stepwise, through time. It’s almost as if Godden were mimicking cinematic technique, dissolving from one image to another (letter to letter, slippers to muff).

The film picks up the hint and does sometimes dissolve from the present to the past. More original, and perhaps closer to the seamless uniting of periods, is the way the narration revives a rare device. In Caravan (1934), the returning Countess Wilma turns to her old governess, asking if she remembers the last day she was in her bedroom. The camera pans left to the governess, who gets a faraway look in her eyes.

Then she scrunches up her face and commands Wilma to come to her. Pan right to Wilma, now a child, in a tantrum.

Interestingly, the whole flashback is played in this one shot, ending on the governess recalling the scene and tracking back to a full shot of the grown-up Wilma.

Similarly, several Enchantment transitions are handled in a single shot, but here the panning movements typically highlight enduring parts of the house. Old Rollo has grudgingly let Grizel stay in Selina’s bedroom. As Rollo says, in an auditory flashback, “There’s no such thing as an empty room,” we see Grizel at the dressing table. The clock stops and as she puts it up to her ear, she looks screen right.

The camera pans to the door, with a maid calling, “Miss Selina,” and then pans back to show Selina as an adolescent at the dressing table.

Nearly all of these single-shot transitions pivot around items that have remained in the house over the years, like a clock or a chandelier or the central staircase. These reflect passages in Godden’s novel that itemize household furnishings across the years or use them to tie together two scenes in different years.

No such thing as an empty room

While speaking of those years, I’ve oversimplified a bit. In Take Three Tenses, even the World War II era, the most recent setting of the action, is enclosed in a frame given in what we might call the persisting present. The book begins:

The house, it seems is more important than the characters. “In me you exist,” says the house.

There follows a past-tense account of the elderly Rollo’s learning that his family’s lease on 99 Wilshire Court is up. Then we have a several-page tour, in the present tense, of the house from top to bottom. It’s launched by this sentence:

In the house the past is present.

Moreover, Godden takes literally the house’s claim that “In me you exist.” She confines all the novel’s directly presented action to the building. What happens outside, we learn through reports. At the book’s end the opening tour is echoed in miniature. There various lines of dialogue from all periods mingle, and the narration insists that the house will endure “in its tickings, its rustlings, its creakings” and ends “In me you exist.” So the house, past, present, and future, enfolds all the dramas played out in it.

The sovereignty of domestic structure is provided by the novel’s chapter structure, which, after an initial “Inventory,” presents “Morning,” “Noon,” “Four o’Clock,” “Evening,” and “Night.” The headings gather only scenes taking place at the named time of day, though the scenes are gathered freely from across many years. (Take that, Alan Ayckbourn.) The fugal voices come together at these nodal points. Once again, the house sets the rules, the household routines being more important than a chronological or causally-driven time scheme.

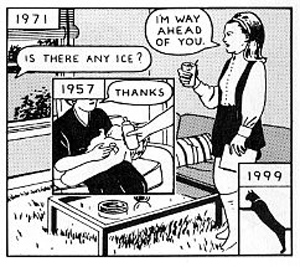

Godden’s effort to suggest layers of the past in any room or time of day is difficult to capture on film. Perhaps Richard McGuire, working in the medium of comics, comes closer with his famous 1989 piece “Here.” A room’s corner is invaded by events from many periods.

An approximate cinematic equivalent is Ivan Ladislav Galeta’s Two Times in One Space (1976/1985), with a time delay that creates ghostly figures from moments 219 frames apart.

Only the room remains stable in this out-of-phase presentation of a meal prepared and eaten. (Perplexingly, the action on the distant balcony unfolds in standard duration.)

Galeta’s version isn’t an option for a classical Hollywood film like Enchantment. The closest analogy comes during a parallel between Rollo as a young officer out to meet Lark, and Pax as he hurries to meet Grizel. A graphically matched dissolve puts Pax in Rollo’s place.

This device, however, doesn’t convey the persistent presence of the house. Enchantment finds another way to shelter its interchange between past and present. It lets the house talk.

As the film opens, the camera approaches 99 Wilshire Court and the house introduces itself to us in voice-over commmentary. “You almost passed me.” The house invites us to “see what the mirrors have seen.” It turns mournful. “I miss my people. In me they live.” The camera coasts through empty rooms, as we hear voices welling up from different parts of the past.

We don’t know the speakers yet, but the device prefigures the dramas to come, as well as suggesting Godden’s idea that the house endures as a repository of fugitive, phantom life. As the camera reveals Rollo talking with his solicitor, the voice-over explains, “The house is his story.”

Although we might not recognize it on first viewing, this is another single-shot flashback, since in the initial present, that of the deserted house, Rollo is already dead. The narration is taking us back to the opening phase of the wartime plotline.

Trimming back Godden’s ensemble plot, the narration gives us a protagonist and identifies what happens to the house with what has happened to him. Yet the house takes precedence, in that the flashbacks aren’t triggered by his or anyone else’s memory. This is rare in classical cinema of the period, which usually motivated returns to the past by someone recounting or recalling earlier events. It would be too glib to say that these flashbacks are “the house remembering,” but the fact that transitions are more objectively anchored than usual does yield a sense that time has a shape that we sense more acutely than the characters can.

Subjectivity does enter, at least apparently, in Rollo’s imaginary dialogues with Lark. At various points she speaks to him in imagination, or in some realm the lovers share. Again, though, we can’t ascribe those voices to his mind. After he has been killed, the camera tracks back from his body.

As in the beginning, voices haunt the parlor. During the camera movement the young Lark asks, “We shall always be in love, won’t we?” “Yes,” Rollo replies. “Even when we’re old?” “Even when we’re old.”

The film doesn’t confine its action as strictly to the house as Godden’s novel does. We follow Grizel to her job at the military post, and the young Rollo to a shop to buy Lark a necklace. Nevertheless, the sense of enclosure, not to mention closure, is provided after we’ve seen Rollo felled by the German bombardment. The camera continues backward, through a window as the house’s voice-over narration assures us that no story really ends. The house seems to have cheered up in the course of the narrative; no longer missing its people, it looks forward to a new generation. Echoing the future-oriented ending of Take Three Tenses, the house concludes: “In me, the young will live again, with the heart’s lease on life.”

Sometimes we expect that recent films will be more complex than older ones, and that’s often true. But an older film often turns out to have more angles than we get nowadays. Julie & Julia is an amusing and touching entry in the American Cinema of Quality. (Is Scott Rudin today’s Samuel Goldwyn?) And it’s true that Enchantment doesn’t multiply its parallels as ingeniously as Julie & Julia does. Yet Ephron entertains us with clever reiterations of the basic comparison of the two women, given in the title anyway. Enchantment avoids such detailing in search of a wider emotional range.

Julia is admirable, and Julie grows by imitating her, but their stories don’t carry the bittersweet resonance of the stories of Rollo and his descendants. You can argue that Enchantment softens some of the novel’s harsher side; there Rollo loses Lark by prevaricating, while in the film he is partly the victim of bad luck. (The trains stopped running.) Even so, the film preserves the severe self-denial we find in Grizel, who sees her fear of passion as “the Dane vice,” and the bitter self-reproach of the lonely Rollo. Then there’s the house as a wise reliquary of human lives, humming with voices from the past. Julie & Julia makes its locales simply part of many tidy parallels. Enchantment lives by comparisons too, but it also lets space come forward as a factor that can, at least momentarily, become as engaging as other dimensions of storytelling.

The approach to narrative theorizing I started out with is, roughly speaking, action-oriented. The ideas of time, causality, and space emerge logically out of a concern with how the plot lays out its arcs of action. An alternative approach, no less fruitful, is agent-oriented. It treats action as secondary to the portrayal of character traits and psychological activity. The agent-centered perspective is especially useful for studying narratives in which the characters seem larger than life and their vividness exceeds their role in the narrative patterning (in Dickens, for instance), or when there is very little external action (as in Beckett). The classical narrative tradition of Hollywood, despite its powers of characterization (helped out by the star system), seems to me to to concentrate most on organizing action. There plot is usually primary. And there’s nothing wrong with that!

For more on flashbacks and their degrees of subjectivity, see “Grandmaster Flashback” on this site.

My quotation from Take Three Tenses: A Fugue in Time (Boston: Little Brown, 1945) comes from p. 174. John R. Frey argues that the tense shifts in the novel are actually more subtly discriminated than I’ve indicated. Godden uses, he claims, the present and the imperfect for the main action and the perfect and the past perfect for the flashbacks. See “Past or Present Tense? A Note on the Technique of Narration,” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 46, 2 (April 1947), 205-208.

Promoting space as a narrative factor, rivaling time and causality, is something Kristin and I have written about in various places. See in particular Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, Chapters 6 and 7.

A short film inspired by McGuire’s “Here” is, well, here. Chris Ware, who wrote an essay, “Richard Mcguire and ‘Here’–A Grateful Appreciation,” Comic Art no. 8 (2008), 4-7, seems to have been inspired by it in certain installments of his Building Stories; also try here, searching under “Building Stories.”

Galeta’s Two Times in One Space is available on this DVD collection of his works.

Julie & Julia.

Chinese boxes, Russian dolls, and Hollywood movies

The Locket.

DB here:

In the 1990s and 2000s, American cinema was hit by a rash of fancy storytelling. Filmmakers experimented with flashbacks, replays, shifting points of view, multiple universes, network narratives, and a host of other unusual devices. (Some prototypes: Pulp Fiction, The Usual Suspects, Memento, and Short Cuts.) These developments nudged me into analyzing the trend in The Way Hollywood Tells It, but my interest in such tricky narration goes back to my adolescent love of detective fiction and the stories of Henry James, Faulkner, and James Joyce. For me, mysteries and modernism went together.

That was especially true of 1940s movies, which I now realize loom large in my film consciousness. Many of the fractured, densely plotted movies I wrote about at length in Narration in the Fiction Film, such as Murder My Sweet, The Big Sleep, In This Our Life, and The Killers, come from the same era as Citizen Kane and How Green Was My Valley. So do subjects I wrote about later, such as Mildred Pierce and Rope and network pictures like Weekend at the Waldorf and Tales of Manhattan.

This summer I face up to my proclivities and give a batch of lectures under the rubric “Dark Passages: Storytelling Strategies in 1940s Hollywood.” The series, accompanied with ten screenings, is part of a “Film College” to be held in Antwerp under the auspices of the Flemish Service for Film Culture and the Belgian Cinematek. I first wrote about this “summer movie camp” here. I probably shouldn’t have called it that; I still get emails from services that sell canoeing gear and organize outings to the Poconos.

Starting to think about this course has given me more ideas than I can pursue in seven lectures, so in the weeks to come don’t be surprised if some chips from the workbench get swept up here. Even if you merely like the 1940s for those gleaming cigarette cases and those fashion shoulders that seem to have been designed with a carpenter’s level, we can enjoy some rather tricky pieces of movie storytelling.

The inner circle

During the early 1930s American studio filmmakers experimented considerably with flashbacks. (I write about that trend here.) Several associated conventions, such as the dissolve-plus-music, as well as the track-in to a narrating or remembering character, seem to have been installed then. But in the 1940s, the flashback became a more wondrous thing.

Relatively rare in the later 1930s, after a few years the technique seemed to be everywhere. You’d expect that Citizen Kane might have set the fashion, but at least eleven other pictures from 1941 boasted flashbacks. A year earlier, Sturges’ The Great McGinty had built its plot around the device and John Farrow’s Married and In Love crammed six flashbacks into less than sixty minutes. Soon critics, those chronic malcontents, protested. In 1944, the Los Angeles Times reviewer Philip K. Scheuer wrote of Double Indemnity, “I am sick of flash-back narration and I can’t forgive it here.” One producer claimed that “the market is glutted with flashback pictures,” and had alternative scripts of The Chase (1946) written to allow the editor to omit the original novel’s flashback. Since the late 1920s, flashbacks had been staples of courtroom dramas, but by late 1948 a reviewer expressed relief that in The Paradine Case (1948) “There are no flashback devices to clutter the trial.”

As flashbacks proliferated, they got weirder. Films gave us flashbacks retelling events from different characters’ perspectives, flashbacks that proved deceptively incomplete or downright false, even flashbacks narrated by corpses. Then there was the embedding option: setting a flashback within an already-established flashback.

Here’s an example. In Shoot to Kill (1947), Marian Dale is brought into the hospital from a car crash and is pumped by a reporter anxious to get her story. The narration flashes back to happier times, when the reporter introduced Marian to Larry, the new district attorney. When Larry takes her to dinner, Marian explains how she came to find him attractive. Now a further flashback shows her listening raptly to Larry’s aggressive prosecution of the case against mobster Dixie Logan. Coming out of this flashback, we’re back in the restaurant, and flirtation continues between Marian and Larry. At later points we’ll come out of that earlier time frame back to the present, with Marian and the reporter in the hospital.

This sort of embedding is an obvious option, but let’s go to the next level. What about a flashback within a flashback that’s already nested inside another flashback? Or even, gulp, flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks? Do the math. The result is like the famous Chinese boxes or Russian dolls, with one story held within another, which is held within another, and so on.

Many of the strangest narrative experiments of the 1940s are to be found in B films. Perhaps in that domain the demand for novelty and rapid turnover is greater and the constraints on plausibility, or even just good sense, are fewer. Shoot to Kill, an independently produced B-item, would seem to be an example, though it’s not as wild as The Sin of Nora Moran (1933), my candidate for America’s most peculiar flashback movie. Surprisingly, though, the multiply-embedded flashback is most prominent in two high-profile films of the 1940s.

How could I talk about them without spoilers?

Marseille or bust

Flashbacks are often presented as solutions to a mystery: we go back to the past to learn how or why something took place in the present.

Passage to Marseille (1944) opens with Manning, a war correspondent, visiting a camouflaged air base in the English countryside. From here Free French pilots launch bombing raids on Germany and occupied France. Struck by the intensity he sees on one gunner’s face, Manning asks his host Freycinet about the man’s past. Freycinet answers with “the story of a little group of whom Matrac was one.” That is the first layer, or the surrounding box.

Aboard the Ville de Nancy: We go back a few years to a French cargo ship carrying nickel ore to Marseille. Freycinet, traveling on orders, runs into conflict with the right-wing Major Duval and his coterie. The ship rescues five men from a drifting boat. Are they prospectors, as they claim? Soon Freycinet realizes that they are convicts, escaped from Devil’s Island. They start to explain how and why they got away.

Devil’s Island: We see the men plan to escape, but these convicts don’t simply want freedom. They are patriots who yearn to fight the Germans. But one, Matrac (Humphrey Bogart), sits apart from the others and won’t explain himself. Why? Another member of the team, Renault, explains.

France, 1938: Daladier returns from Munich with news of an accommodation with Hitler. Matrac, a crusading reporter, is disgusted and writes scathingly of this sellout to Nazidom. His newspaper office is smashed by right-wingers while police and citizens look on. Disabused of his faith in France, Matrac seizes the chance to flee with his lover Paula. But he is arrested, tried on trumped-up charges, and sent to Devil’s Island.

Devil’s Island: After Matrac has been let out of solitary confinement (where he shouted, “I hate France!”), the five men escape from the prison camp. The old man who helps them asks only that they promise to serve French freedom. But Matrac refuses to recite the pledge (above). The new mystery becomes: What has turned him into the loyalist gunner that Manning sees in the opening scene?

Aboard the Ville de Nancy: On the ship, word comes that Marshall Pétain has signed an armistice with the Germans. The captain secretly swerves the ship from Marseille, a Pétain-controlled city, and sets sights on England. But his ruse is discovered by Duval, whose men seize the ship. A fight ensues, with the crew and the Devil’s Island brigade pitted against the pro-German officers. Soon a German bomber arrives to sink the ship, but only after Matrac assures the dying cabin boy that they will drive the enemy out of France.

Back in the frame story, all mysteries from the past have been cleared up. Now Manning appreciates what the pilots have sacrificed, and he understands what has turned Matrac back into a patriot. The film could close quickly, but the plot sets up a new future-oriented suspense. Manning and Freycinet wait for the planes to return from the night’s bombing run. Renault’s plane, though, is delayed, and it brings back a fatally wounded Matrac. This time he has not been able to drop a message to Paula as his plane passes over their farm, but at Matrac’s funeral, Freycinet assures everyone “That letter will be delivered.”

In Passage to Marseille, Matrac’s 1938 adventure forms the core, wrapped in three layers. We have a flashback within a flashback within a flashback, itself surrounded by a frame story set in the present. The whole action takes place across about six years. Why tell the story in this complicated way?

Because, I think, it enhances mystery. The initially formulated mystery is vague, revolving around Manning’s inquiry about the charismatic Matrac, but other questions get more specific. What led these five men to near-death on the open sea? Are they really gold prospectors? Why does Matrac sit sullen while his comrades explain their patriotism to Freycinet? What has made him so bitter? And since we know from the start that he has become a committed patriot, what led him away from his solitude? These aren’t the sorts of questions you get in a classic detective story; they focus on personal psychology and character change. A more linear story tends to give us motives straightforwardly, and it explicitly traces the process of people changing their minds and hearts. The broken timeline creates more curiosity as we are led to ask why people do what they do. These are puzzles of personality.

The film thus gains a double propulsion. We have the usual forward movement, the rhythm of anticipation hinging on the question: What will happen next? But the mystery element adds curiosity about the past, asking: What led up to the situation of crisis that we see now? This double movement is seen in many 1940s films, which in retrospect (my own flashback here) may be one reason I turned to that era in exploring storytelling options in my narration book.

Hopelessly twisted

When we encounter embedded flashbacks, the plot often treats the core, or innermost layer, as the ultimate secret, the source of what teases us in other layers. Like Passage to Marseille, The Locket (1946) turns on a puzzle of character: Is the beautiful and charming Nancy exactly as she seems? We find out when we witness a childhood trauma located in the center of the plot’s geometry.

It’s the wedding day of John Willis. While his dazzling bride-to-be Nancy beguiles the guests, John is called away to meet Dr. Blair in his study. Dr. Blair has come to warn him: Nancy is “hopelessly twisted.” He explains….

Some years earlier: Nancy and Blair meet, fall in love, and marry. With a lovely wife and a flourishing psychiatric practice, Blair couldn’t be happier, but one day a young artist, Norman Clyde, visits his office. Norman tells him that Nancy could be charged with murder, and she must act to save the life of a man about to be executed (image above). He explains….

Earlier: Nancy is visiting Norman’s studio for an art class, and soon they’re involved in a romance. Her boss Andrew Bonner is a patron of the arts, and she calls his attention to Norman’s work. After a party celebrating Norman’s recent success, Norman finds that Nancy has stolen another guest’s expensive bracelet. He asks her why she did it, and she explains….

Childhood trauma: Nancy is ten, and her mother works as a servant for a wealthy family. The daughter of the house, Karen, is Nancy’s best friend. Karen gets a diamond locket for her birthday, but she gives it to Nancy. When her mother finds out, she takes it back and upbraids the girl. Later Karen’s locket is missing. Although it simply went astray, Karen’s mother brutally forces Nancy to confess that she stole it. Nancy and her mother are dismissed from the household.

Back in Norman’s studio, he points out that Nancy’s stealing the bracelet at the Bonners’ party was her effort to get even with Karen’s mother. Nancy swears to never steal again, and he anonymously mails the bracelet back to its owner. Later, at another art-crowd party at the Bonners, Norman is looking for Nancy when he hears a gunshot. Upstairs, he finds Nancy running down the corridor while a maid discovers Bonner’s body. Later, Nancy denies killing her boss, and Norman agrees to conceal what he saw. But he’s tormented by the fact that a manservant is now the chief suspect. Claiming that he’s too suspicious of her, Nancy breaks off their affair.

Back in Blair’s office, Norman begs Blair to induce Nancy to confess and save the servant, who’s to be executed tonight. Norman visits Blair and Nancy, who admits their old affair but denies killing Bonner. The next day, with the servant now executed, Norman flings himself through Blair’s office window and falls to his death. Shaken, Blair returns to England, where he and Nancy take up the war effort. When a bomb is dropped on their own street, Blair searches the rubble of their apartment and finds jewels that have gone missing from the collection of an acquaintance. Nancy turns up unharmed, but Blair has a breakdown and Nancy leaves England.

Back at the wedding: John remains skeptical, especially after Nancy comes in. She smilingly admits knowing Blair, but says he was only her psychoanalyst. She points out that he cracked up in London and was recently released from an asylum. Having renewed John’s trust, she goes to meet his mother, revealed as well to be the mother of Karen, her playmate of long ago.

We now understand that Nancy is marrying into the family that had cast her out as a child. Karen has died, and her mother fastens Karen’s treasured locket around Nancy’s neck. Trying to brazen through the ceremony, Nancy is assailed by memories of her childhood and her crimes. She becomes dizzy, screams, and faints. As she’s taken to a sanitarium, John decides to go with her, adhering to Blair’s last bit of advice: “Lockets are only symbols. It’s love she needed–and love she needs now.” Maybe she isn’t as hopelessly twisted as he had initially said, or as the plot itself seems to be.

Hitchcock’s films Spellbound and Marnie saved the revelation of childhood trauma for the climax, but The Locket doesn’t do that. Nor does the scene come at the exact center of the running time, as the plot geometry might suggest. The childhood scene arrives at the sacred twenty-five-minute mark, after Nancy’s confession to Norman that she stole the bracelet at the Bonners’ party. The plot thus emphasizes the aftershocks of Nancy’s childhood, creating suspense about whether she can continue to hide her trauma.

Someone versed in modern literature might ask: But can we be sure that we now know her trauma? Her confession to Norman is embedded in the tale Norman tells Dr. Blair. He is a somewhat unbalanced fellow, rude, proud, and inclined to do rash things. “Why,” he asks in his voice-over, “was I always throwing away the very things I wanted?” And of course his tale is embedded within the story Blair tells John Willis, the prospective bridegroom. By the end of his time with Nancy, Blair is a nervous wreck; he could be delusional. In literature, we might well suspect a trauma that has made its way through three filters (adult Nancy-Norman-Blair).

This possibility is accentuated by the film’s unusual adherence to each character’s range of knowledge during each flashback. We know pretty much only as much, in turn, as the child Nancy, Norman, and Blair know. Most classical flashbacks roam more freely outside the recounting or recalling character knew, or could have known. The Locket‘s restriction to each man successively optimizes the mystery of grown-up Nancy. But the strategy also offers no outside validation that what each man tells us actually happened. With no external or objective scenes of Nancy doing vicious things, the film locks us within what could be wholly hallucinatory tales.

Classical Hollywood film doesn’t try to undermine us so thoroughly, though. However modernist the multiple-narrator format of the film looks, the implications for reliability aren’t as unsettling as in literary works like The Sound and the Fury. The conventionally realistic style of most of the film makes it difficult for us to imagine layers of lying. We’re most likely to take what see and hear as veridical, unless there are explicit clues (as in, say, the landscapes and plot twists of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari) to ask us to ask whether what we’re seeing is unreal in the fiction. What actually ensues is a drama of crafty concealment. As the evidence piles up against her, the question becomes: How will Nancy outwit her man this time?

This maneuver is especially significant in the film’s last third, when Blair suspects that she has stolen jewelry from Lord Windham’s collection. He tries to peek into her purse, but when she finally shakes out its contents, the missing locket isn’t there. He is relieved, though his suspicions continue to prey on his mind. We have to wait too, but when Blair finds the necklace in the apartment wreckage, we’re hardly surprised. Everything we see has been actual; we must doubt Nancy, not the narrators.

A ghastly melodrama

Even in the men’s stories, the film drops a few hints that Nancy isn’t what she seems. At one point, the camera lingers on her after Blair has left her in their London apartment. As she closes the curtains for the blackout, she crouches and looks askance in the classic posture of the guilty one. (On re-viewing, we might take this as suggesting she was looking off at the real hiding-place of Lord Windham’s locket.) Earlier, when she starts to tell Norman of Mrs. Willis’ abuse of her, she turns from him and looks at the camera, as if asking us to believe her.

Above all, there is the linkage of Nancy with Cassandra, the suffering madwoman of Greek mythology who was notoriously ignored by those she tried to warn. She had the gift of prophecy, but that quality seems denied Nancy. The prophetess we meet in the movie is a horoscope reader at the wedding, and she supplies banal and contradictory predictions. More telling, and spooky, is the fact that the Cassandra of the film is seen in Norman’s painting, and her eyes are filmed over, blank and presumably blind. This image is counterposed to the portrait Norman later paints of Bonner’s wife. She is confined to a wheelchair but on the canvas, she is presented as majestically erect and possessed of a penetrating glance.

The blind Cassandra seems scarily oblivious to her madness, while this painted mother-figure seems all-seeing. It’s no great reach to consider her a variant of Karen’s mother, who tormented the young Nancy and who comes back at the end as another, less serene incarnation of Norman’s second painting.

In sum, the prophetic quality of the heroine’s namesake is taken over by the film’s overall narration, which makes sure that everything that is planted early (the locket, the painting, a music box, the mean Mom) comes back with a relentless logic at the end.

But we shouldn’t forget that the Cassandra of legend was repeatedly raped. If she’s mad, men helped make her that way. The film is as much a study in male neurosis as in female frailties. Behind the swagger and insults, Norman is insecure, and he ends his life spectacularly. Earlier he had told Nancy: “If I had to relive these past few weeks, I’d kill myself.” As for Dr. Blair, on the strength of a single encounter, he smugly diagnoses Norman as “a paranoiac with guilt fantasies.” Yet he forgets that Norman told him about the partygoer’s missing bracelet, as if his wife’s childhood loss of the locket erased his awareness of what led her to tell it. After a few years with Nancy and the blitz, he’s the one who ends up in an asylum.

Unlike the stalwart heroes of Passage to Marseille, Nancy’s men trace no smooth character arc. The fragments given us in Passage can be swiftly reassembled. We understand that characters can change, and we expect that the film will trace out the men’s survival, especially after the opening establishes their successful bombing missions. We also note that Matrac is played by Bogart, and anyone who caught Casablanca (released fifteen months earlier) could see his change of heart coming from far off.

In The Locket, the failure of the men to understand, let alone heal, Nancy is made explicit when she tells Blair about a film she’s just seen. “I’m all goosepimples.” “A melodrama?” he asks. (We need to recall that in the 1940s that term was often applied to crime films and thrillers.)

Nancy: Yes, it was ghastly. You ought to see it, Harry. It’s about a schizophrenic who kills his wife and doesn’t know it.

Blair, laughing: I’m afraid that wouldn’t be much of a treat for me.

Nancy: That’s where you’re wrong. You’d never guess how it turns out. Now it may not be sound psychologically, but the wife’s father is the–

Blair: Darling, do you mind? You can tell me later.

Nancy’s father, she told Norman, was a painter like him, but he failed, and he is already dead when we see her as a child. In the popularized Freudianism of the 1940s, perhaps Nancy lacks the firm guidance of a strong male; certainly her kindly but ineffectual mother isn’t much help to her. But then neither are these supposedly grown-up men.

Risks and rewards

During Nancy’s hallucinatory march to the altar, music and dialogue and visual moments from earlier in the film collide and overwhelm her. But this is merely the climax of the inward bent of The Locket as a whole, which contains almost no exterior scenes. We might be tempted to attribute this interiority to the old standbys, wartime trauma and postwar malaise. The subjective sequences could be put down to the resurgence of Expressionist style, purportedly under the influence of German directors and technicians who fled to Hollywood. So far, so familiar.

I’m inclined to see a different dynamic at work. What if the stereotypes of situation and imagery sprang not from a Zeitgeist or localized influences? What if current themes and trends were exploited by filmmakers aiming for a more complicated sort of storytelling that still adhered to the models given by tradition? For reasons I hope to explore in my lectures and in some blog jottings, I think that many American filmmakers aimed more or less deliberately to revise Hollywood narrative norms in fresh, sometimes startling ways. In their urge to shake up their audiences, writers, directors, and others competed in pushing the envelope, straining the premises further as the decade went on. Why not a blind Cassandra or a mixup of mother-figures? Why not tell a story from a corpse’s point of view?

This enterprise gave us many fresh, even shocking films, but they risked incoherence. You see it in the resort to amnesiac heroes, to savage dreams, to perfunctory or downright inconsistent endings, to angels who might rescue us, to moments that repeat or condense or contort other images scattered across the movie, like the queenly mothers and blind prophetess of The Locket. When a producer is ready to leave decisions about flashbacks to the editing stage, you shouldn’t be surprised by gaps and disparities.

Still, even if a movie gets hopelessly twisted, it can provide a creative play with storytelling options. Or so I’ll try to show from time to time in the next few months.

An earlier entry discusses the cycle of early-1930s flashback films. The quote from Philip Scheuer comes from James Naremore’s subtle and informative More Than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts, 2d ed., 2008, 17. The quotation from Seymour Nebenzal, producer of The Chase, appears in “Hollywood Inside,” Variety (16 September 1946), 2. The finished film did drop the novel’s flashback, but something more peculiar was put in its place. (That’s a whole other blog.) The Paradine Case review is quoted in an advertisement for the film in Variety (15 January 1948), 3.

My outline of Passage to Marseille simplifies the plot architecture just a little. The first Devil’s Island block is actually two chunks, a brief one introducing a few of the team, followed by a return to the narrating situation on the ship, and then followed by much lengthier set of scenes on Devil’s Island. The logic of the “sandwich-structure” flashbacks remains intact, though.

Barbara Deming’sRunning Away from Myself: A Dream Portrait of America Drawn from the Films of the 40’s, pp. 23-25, fits the iconography and narrative reversals of Passage to Marseille into a wider trend of wartime patriots who, apparently having cast off their cynicism, make commitment to the cause seem a new form of their earlier despair.