Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

Time for a quick one: A miscellany from friends

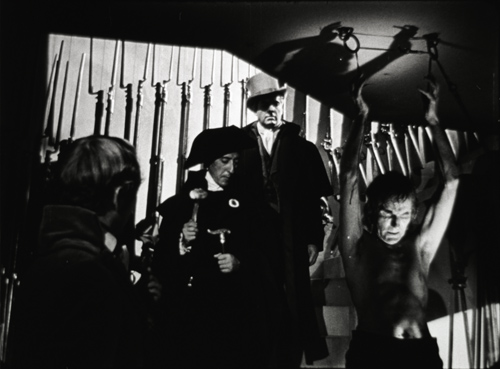

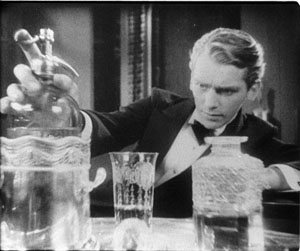

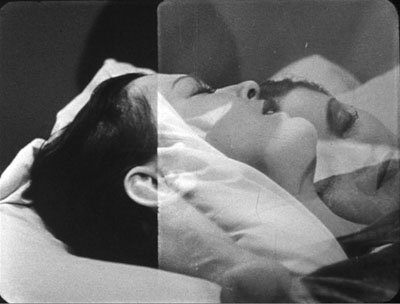

The Black Book (aka Reign of Terror).

DB here, catching up with books, videos, and events:

David Cairns has written a lively appreciation of William Cameron Menzies for the March/ April issue of The Believer. The essay bristles with rapid-fire aperçus, such as the suggestion that the great, demented Kings Row is something like the Twin Peaks of its day. David is particularly good at plotting the extent to which Menzies dominated the work of his directors. Directors without a visual style of their own, he points out, were easy for Menzies to overwhelm, but those with an already-developed signature could assimilate his contributions, as Hitchcock did in Foreign Correspondent.

David Cairns has written a lively appreciation of William Cameron Menzies for the March/ April issue of The Believer. The essay bristles with rapid-fire aperçus, such as the suggestion that the great, demented Kings Row is something like the Twin Peaks of its day. David is particularly good at plotting the extent to which Menzies dominated the work of his directors. Directors without a visual style of their own, he points out, were easy for Menzies to overwhelm, but those with an already-developed signature could assimilate his contributions, as Hitchcock did in Foreign Correspondent.

In The Black Book (aka Reign of Terror) Menzies found soul mates in two other aggressive pictorialists, Anthony Mann and John Alton, the team becoming “a crazy triangle,” eager to indulge in “thrusting gargoyle faces in fish-eye distortion, clutching shadows, and funky, teetering compositons.” Bob Cummings never looked so bizarre, before or since. I didn’t talk about this wild movie in my online Menzies material here and here because I had such poor illustrations from it. Now things have changed, and a decent, or perhaps rather indecent, sample of the film’s delirium (above) can serve to back David’s point.

David’s “Dreams of a Creative Begetter” is one of several film-related pieces in this issue of The Believer. The issue includes a DVD of the seminal People on Sunday (Menschen am Sonntag, 1930), which gathered the talents of Billy Wilder, Curt Siodmak, Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, Fred Zinnemann, and Rochus Gliese. A helpful introductory essay is at the Believer site.

Speaking of David’s writing, don’t miss his superb shot-by-shot analysis of a key scene in Gilda at his Shadowplay site, an obligatory stop for all cinephiles.

Seldom does a monograph on a single film probe so deeply as Mette Hjort’s new book on Lone Scherfig’s Italian for Beginners. It’s easy to take this movie as Dogme Lite, since compared to the earliest, rather harrowing Dogme efforts, it’s an ingratiating romantic comedy-drama. Mette does justice to this side of Scherfig’s film, but she also shows that it’s an exercise in moral seriousness. Reconstructing the production process, she conducts in-depth analysis of performance and technique. She is sensitive to actors’ moments, such as simply laying down a knife and fork; aware that these gestures are developed through improvisation, she is able to trace how each character is built up through details.

In her books and articles on the Dogme school Mette has shown that its innovations go beyond the vaunted technical “rules.” She always addresses them, of course; here she provides an illuminating typology of ways the rules have been followed or dodged. But she also stresses, as most writers don’t, that Dogme films engage with matters of political importance. For example, she has shown that The Idiots’ controversial display of “spazzing” triggered an important debate about Danish attitudes toward the disabled. In her new book Mette indicates that Scherfig’s efforts to endow her characters with the dignity to be found in everyday life offers viewers a chance “to re-connect with one of their culture’s most powerful moral commitments.” Mette talks about the project in this video.

David Gordon Green directs Your Highness; Justin Lin signs his third Fast & Furious movie. With indie filmmakers eagerly joining the tentpole and franchise business, the whole phenomenon seems due for a rethink. This makes Michael Z. Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture all the more necessary. Although I can’t be unbiased, because I served as Michael’s advisor on the dissertation that became the book, I think that any reader would find the result a fresh and vigorous exploration of the achievements of the Sundance/ Miramax generation.

David Gordon Green directs Your Highness; Justin Lin signs his third Fast & Furious movie. With indie filmmakers eagerly joining the tentpole and franchise business, the whole phenomenon seems due for a rethink. This makes Michael Z. Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture all the more necessary. Although I can’t be unbiased, because I served as Michael’s advisor on the dissertation that became the book, I think that any reader would find the result a fresh and vigorous exploration of the achievements of the Sundance/ Miramax generation.

Michael starts by looking closely at the audiences and marketing. He suggests that viewers engage with the films through particular viewing habits (e.g., “Characters are emblems”). He then shows how these habits were nourished and refined by distributors, promotion, and film festivals. The next two sections of the book consider what we might take to be the two poles of indie difference from Hollywood: greater realism, and more self-conscious artifice. The central chapters analyze realism in relation to “character-centered” filmmaking in the Indie trend. Michael turns a critical eye on characterization in films as different as Walking and Talking, Lost in Translation, and Welcome to the Dollhouse. The third batch of chapters considers the trend’s other major appeal, the sort of play with style and form we get in the Coens, Tarantino, Nolan, and others.

Michael shows how character-driven realism and gamelike artifice mesh well with the mandates of distribution and reception—how, in effect, “originality” becomes something that can be calculated and branded. The book concludes with thoughts on the evolution of the trend, comparing Happiness with Juno and raising the inevitable question: How artistically independent is independent film? Newman leaves us pondering: “Indie cinema has become Hollywood’s most prominent alternative to itself.”

One of the hallmarks of the Wisconsin program in film studies is its nuanced refusal of the art/ commerce duality that supposedly rules filmmaking. From many angles, researchers here have shown that creative impulses and business mandates mix in complicated ways, and the results are often fascinating. Indie is one example of this sort of research project, and so is another dissertation-become-book, Christopher Sieving’s Soul Searching: Black-Themed Cinema from the March on Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation. (Again, I was involved, serving on the committee chaired by Tino Balio.)

One of the hallmarks of the Wisconsin program in film studies is its nuanced refusal of the art/ commerce duality that supposedly rules filmmaking. From many angles, researchers here have shown that creative impulses and business mandates mix in complicated ways, and the results are often fascinating. Indie is one example of this sort of research project, and so is another dissertation-become-book, Christopher Sieving’s Soul Searching: Black-Themed Cinema from the March on Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation. (Again, I was involved, serving on the committee chaired by Tino Balio.)

Chris concentrates on 1960s black-themed films from A Raisin in the Sun onward, because he wants to trace how filmmakers tried out a variety of ways to represent and comment on black life. It was a transitional era, but as he puts it “because of the insights they reveal about the periods that bracket them, transitional periods are among the most fascinating and significant in all of film history.”

For Chris, Gone Are the Days (1963), The Cool World (1964), Uptight (1968), The Landlord (1970), and the unproduced Confessions of Nat Turner provide case studies of alternatives to what became the crime-and-comedy product of blaxploitation. Why did decision-makers believe that black-themed films would sell broadly enough to repay investment? What choices and compromises were necessary to “universalize” material (for white viewers) while also retaining “authentic” blackness? Or was it better simply aim the films at white liberals?

Chris tackles such questions through a painstaking study of the film industry’s efforts to find, or create, an audience for films that took great risks. Written with verve (on the screen handling of the Black Panthers, Chris talks about Hollywood’s “Black Power outage”), Soul Searching revives films that are all but forgotten and shows how their efforts to create one variety of independent cinema failed for particular social and industrial reasons.

Someone I’ve been meaning to spotlight for a while: Frédéric Ambroisine is a multitalented critic, filmmaker, stuntman, and collector based in Paris. One of his careers is making supplements for French DVD releases of Hong Kong films, both classic and current. If you have even a smattering of French, you can follow his supplements with ease. He gets precious interviews with screen legends like Kara Hui Ying-hung and Ku Feng (below), master villain of the great New One-Armed Swordsman.

The videos from Wild Side often include Fred’s featurettes. You can follow Fred’s activities at actionqueens.com and alivenotdead. Much of the material in both places is in English.

Finally, if you’re in Los Angeles this week, why not visit the celebration of Orphan Films playing at UCLA 13 and 14 May? While I was in New York in February, I met NYU’s Dan Streible, moving spirit of the Orphan Films movement. Dan and his colleagues work with archives, collectors, and filmmakers to save films that fall through the cracks, digging up everything from home movies to news clips and experimental cinema. Dan curated a program of orphans at our local festival earlier this spring. At UCLA he will be a guest for screenings and discussions of many orphan titles, including the mysterious Madison Newsreel (Madison, Maine alas, not Wisconsin). Go here for Sean Savage’s discussion of the orphan oddity that has become a cult movie, and here for background on Northeast Historic Film, which found the footage.

PS: Speaking of friends, I should thank the solicitous people who wrote me during my recent illness. I appreciate your get-well notes, and I’m happy to report that I’m on the mend.

“World’s Youngest Acrobat” (Hearst Metrotone/ Fox Movietone 1929). From Orphans 7: A Film Symposium.

Foreground, background, playground

The Devil and Miss Jones (1941); The Hudsucker Proxy (1994)

DB here:

I’ve been waiting for thirty years for Alice in Wonderland. No, not the theatrical release of Tim Burton’s version. That interests me only mildly. I’m referring to the DVD release of the 1933 Paramount picture. I saw it on TV as a kid, and remembered it only dimly. But it bobbed up on my horizon in the summer of 1981 when I was doing research on our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema.

I was in the old Academy library in Los Angeles studying the emergence of certain compositional schemas. I can’t recall what put me on the track, but I requested the shooting script of Alice. What came was Farciot Edouart’s copy, over six hundred pages teeming with sketches for each shot. And a lot of those shots had a startling similarity to good old Citizen Kane.

I was in the old Academy library in Los Angeles studying the emergence of certain compositional schemas. I can’t recall what put me on the track, but I requested the shooting script of Alice. What came was Farciot Edouart’s copy, over six hundred pages teeming with sketches for each shot. And a lot of those shots had a startling similarity to good old Citizen Kane.

I was reluctant to attribute pioneering spirit to director Norman Z. McLeod. Instead, I realized that these images’ somewhat freaky look owed more to one of the strangest talents in Hollywood history.

I tried to see Alice in Wonderland, but I couldn’t track down a print. So for years I’ve been waiting to find if it confirmed what I saw on those typescript pages. In the meantime, for the CHC book and thereafter, I’ve bided my time, sporadically looking in on the career of one of Hollywood’s most eccentric creators. He’s the subject of a new web essay I’ve just posted here (or click on the top item under “Essays” on the left sidebar). Today’s blog entry is a teaser trailer for that.

Deep thinkers

It’s commonplace now to say that Citizen Kane (1941) pioneered vigorous depth imagery, both through staging and cinematography. Many of the film’s shots set a big head or object in the foreground against a dramatically important element in the distance, both kept in fairly good focus. But where did this image schema come from?

The standard answer used to be: The genius of Gregg Toland and Orson Welles. In the 1980s, however, I wanted to explore the possibility that something like the deep-focus look had been a minor option on the Hollywood menu for some time. Once you look, it’s not hard to find Kane-ish images in 1920s studio films, from Greed (1924) to A Woman of Affairs (1929).

During the 1930s, William Wyler cultivated such imagery in some films shot with Toland, such as Dead End (1937), and some films shot by other DPs, such as Jezebel (1938). In turn, Toland had undertaken comparable depth experiments in films with other directors. Moreover, yet other directors, notably John Ford, had used this sort of imagery in films shot by Toland and others, such as George Barnes, Toland’s mentor. There are plenty of non-auteur instances too. (See my post on 1933 Columbia films.) We also find similar imagery in films from outside America. Here’s a stunner from Eisenstein’s Bezhin Meadow (banned 1937).

You see how complicated it gets.

What I concluded in Chapter 27 of CHC was that Toland and Welles didn’t invent the depth technique. They fine-tuned it and popularized it. Their predecessors, in the US and elsewhere, had staged the action in aggressive depth and used many of the same compositional layouts. But the wide-angle lenses then in use couldn’t always maintain crisp focus in both planes (below, American Madness, 1932).

Welles and Toland found ways to keep both close and far-off planes in sharp focus. They deployed arc lamps, coated lenses, and faster film stock. Although it wasn’t publicized at the time, we now know that some of the most famous “deep-focus” shots were also accomplished through back-projection, matte work, double exposure, and other special effects, not through straight photography. Again, though, this tactic was anticipated in earlier films. One of my favorite examples comes from a matte shot in Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1935).

Menzies seems to have planned for similar fakery. In the script for Alice in Wonderland we find: “CLOSE UP, leg of mutton. The room and characters in the background are on a transparency.”

The flashy depth compositions of the 1920s and 1930s were typically one-off effects, used to heighten a particular moment. Welles and Toland pushed further by making the depth look central to Kane’s overall design and by featuring such imagery in fixed long takes. The prominence of Kane may have encouraged several 1940s filmmakers, such as Anthony Mann, to make the depth schema part of their repertoire. But as the style was diffused across the industry, the hard-edged foregrounds became absorbed into dominant patterns of cutting and spatial breakdown. The static long takes of Kane remained a rare option, perhaps because they dwelt on their own virtuosity.

Digging up films made around the time of Kane, I found many filmmakers experimenting with the look that Toland and Welles highlighted. You can see touches of it in The Maltese Falcon (1941) and All That Money Can Buy (1941). Above all, there are two remarkable movies directed by, of all people, Sam Wood. Our Town (1940) turns Wilder’s play (itself surprisingly melancholy) into a Caligariesque exercise.

Several shots anticipate the low-slung depth, bulging foregrounds and all, that became the hallmark of Citizen Kane a year later.

Our Town also uses postproduction techniques that yield depth-of-field effects you couldn’t get in camera.

Perhaps even more startling is Wood’s Kings Row (1942), with deep-focus imagery that occasionally rivals Kane‘s.

From the evidence I was encountering, it seemed that Welles and Toland’s accomplishment was to synthesize and push further some deep-space schemas that were already circulating in ambitious Hollywood circles. Connecting some dots, I realized that one of the earliest champions of aggressive imagery in general, not just big foregrounds and deep backgrounds, was William Cameron Menzies.

Menzies frenzies

Menzies started out as an art director, most famously for United Artists. He designed sets for Mary Pickford’s Rosita (1923, directed by Lubitsch) and several Fairbanks films, notably The Thief of Bagdad (1924). He won the first Academy Award for set design and went on to a noteworthy career—most famously as production designer for Gone with the Wind (1939). He also directed films, such as Things to Come (1936) and Invaders from Mars (1953). Most significant for my purposes, he was production designer for Our Town, Kings Row, and three other films of the early 1940s directed by Sam Wood. And he designed the 1933 Alice in Wonderland. The drawings I saw in Edouart’s script were by Menzies or his assistants.

Menzies was one of the chief importers of German Expressionist visuals to the US. Although his early efforts leaned toward Art Nouveau effects, by the end of the 1920s he was cultivating a dark, contorted look keyed to the harsh geometry of city landscapes.

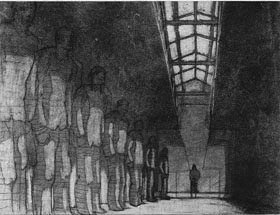

Since the late 1920s, Menzies had explored the possibility of steep depth compositions. He didn’t usually employ a big foreground, but he did favor overwhelming perspective–either abnormally centered or abnormally decentered. Here is his sketch for Roland West’s Alibi (1929) and the shot from the finished film.

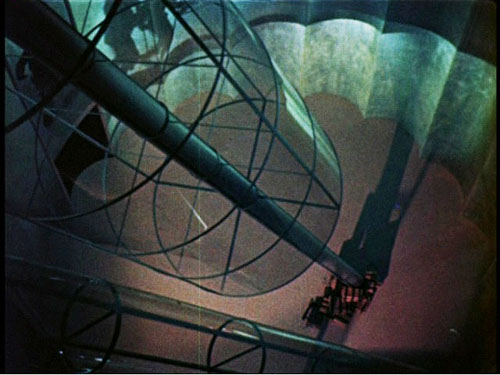

Menzies loved slashing diagonals created by architectural edges and worm’s-eye viewpoints. The harrowing opening of Things to Come is full of such flashy imagery.

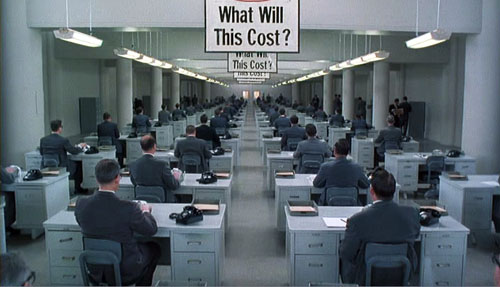

Menzies calmed his style down for GWTW, although the sequences he directed bear traces of his inclinations. And in his work for other directors he managed to slip in a few odd shots. Here, for instance, is a typically maniacal central perspective view from H. C. Potter’s Mr. Lucky (1943). Squint at this image and you’ll see that it’s weirdly symmetrical across both horizontal and vertical axes.

When he met Sam Wood, it seems, Menzies found a director ready to let his imagination roam further. In these collaborations, we get depth shots à la Welles and Toland, but also skewed perspectives. Pride of the Yankees (1943/44) searches for ways to make a baseball stadium look like a Lissitzky abstraction.

Menzies subjects the partisans of For Whom the Bell Tolls (1944) to his sharp diagonals as well.

Alice, we hardly knew ye

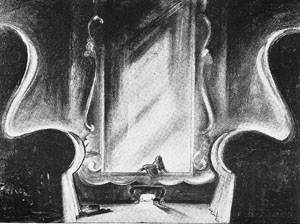

What then of Alice in Wonderland? Back in the early 1980s, I wasn’t permitted to photocopy or photograph script pages. Here is one of the few sketches I later found for the film. Alice crawls into the mirror with looming armchairs in the foreground.

Surely, I thought, the film would be an early example of the depth aesthetic that would be developed by Welles, Wyler, and Wood/ Menzies. Alas, the film has nothing like those imperious armchairs.

In fact, Alice proves a huge disappointment on the pictorial front. Menzies expended all his ingenuity on the special effects, coordinated by Paramount master Farciot Edouart. Although the spfx are not in the league of that other big 1933 effects-film King Kong, they are pretty solid for the time. It’s just that this remains a painfully arch, flatly filmed exercise.

But I look on the bright side. Menzies created some memorable movies, both on his own and with other directors. (Of his directed films, not only Things to Come but Address Unknown, 1944, remain of interest today.) Perhaps most important, his stylistic boldness may have encouraged other filmmakers to try something fresh. Most immediately there is Since You Went Away (1944), a big Selznick production that bears traces of the Menzies touch.

More broadly, Menzies represents a strand in American cinema that never really disappeared. His frantic Piranesian perspectives, canting the camera and filling the frame with grids, whorls, and cylinders, are still in use. And his head-on, wide-angle grotesquerie looks ahead to the Coen brothers. This shot of a department-store manager in The Devil and Miss Jones (1941) could come from any of their films.

Menzies’ films, though mostly not celebrated as classics, gave American cinema the permission to be peculiar. Meet me in the sidebar for a closer look at one of Hollywood’s most eccentric creators. Special thanks to Meg Hamel for going beyond the call of duty in posting that essay.

Invaders from Mars (1953); Shutter Island (2010).

Grandmaster flashback

DB here:

Elsewhere I’ve sung the glories of Turner Classic Movies. Would that the other basic-cable staple, the Fox Movie Channel, were as committed to classic cinema. It’s curious that a studio with a magnificent DVD publishing program (the Ford boxed set, the Murnau/ Borzage one) is so lackluster in its broadcast offerings. Fox was one of the greatest and most distinctive studios, and its vaults harbor many treasures, including glossy program pictures that would still be of interest to historians and fans. Where, for instance, is Caravan (1934), by the émigré director Erik Charell who made The Congress Dances (1931)? Caravan‘s elaborate long takes would be eye candy for Ophuls-besotted cinephiles.

Occasionally, though, the Fox schedulers bring out an unexpected treat, such as the sci-fi musical comedy Just Imagine (1930). Last month, the main attraction for me was The Power and the Glory (1933), directed by William K. Howard from a script by Preston Sturges.

This was an elusive rarity in my salad days. As a teenager I read that it prefigured Citizen Kane, presenting the life of a tycoon in a series of daring flashbacks. I think I first saw it in the late 1960s at a William K. Everson screening at the New School for Social Research. I caught up with it again in 1979, at the Thalia in New York City, on a double bill with The Great McGinty (1940). In my files, along with my scrawls on ring-binder paper, is James Harvey’s brisk program note, which includes lines like this: “One of Sturges’ achievements was to make movies about ordinary people that never ever make us think of the word ‘ordinary.’” I was finally able to look closely at The Power and the Glory while doing research for The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985). The UCLA archive kindly let me see a 16mm print on a flatbed viewer.

So after a lapse of twenty-eight years I revisited P & G on the Fox channel last month. It does indeed prefigure Kane, but I now realize that for all its innovations it belongs to a rich tradition of flashback movies, and it can be correlated with a shorter-term cycle of them. Rewatching it also teased me to think about flashbacks in general, and to research them a little. You see, I am very fond of what contemporary practitioners like to call broken timelines.

A trick, an old story

On our subject for today, the indispensible book, which ought to be brought back into print or archived online, is Maureen Turim’s Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History (Routledge, 1989). We may think of the flashback as a modern technique, but Turim shows that flashbacks have been a mainstay of filmic storytelling since the 1910s.

On our subject for today, the indispensible book, which ought to be brought back into print or archived online, is Maureen Turim’s Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History (Routledge, 1989). We may think of the flashback as a modern technique, but Turim shows that flashbacks have been a mainstay of filmic storytelling since the 1910s.

Although the term flashback can be found as early as 1916, for some years it had multiple meanings. Some 1920s writers used it to refer to any interruption of one strand of action by another. At a horse race, after a shot of the horses, the film might “flash back” to the crowd watching. (See “Jargon of the Studio,” New York Times for 21 October 1923, X5.) In this sense, the term took on the same meaning as then-current terms like “cut-back” and “switch-back.” There was also the connotation of speed, as “flash” was commonly used to denote any short shot.

But around 1920 we also find the term being used in our modern sense. You can find it in popular fiction; one short story has its female protagonist remembering something “in a confused flashback.” F. Scott Fitzgerald writes in The Beautiful and Damned of 1922:

Anthony had a start of memory, so vivid that before his closed eyes there formed a picture, distinct as a flashback on a screen.

At about the same time writers on theatre start to adopt the term and credit it to film. A historian of drama writes in 1921 of a play that rearranges story order:

The movies had not yet invented the flashback, whereby a thing past may be repeated as a story or a dream in the present.

Within film circles, there were signs of an exasperation with the device. One 1921 writer calls the flashback a “murderous assault on the imagination.” Turim quotes a New York Times review of His Children’s Children (1923):

For once a flash-back, as it is made in this photoplay, is interesting. It was put on to show how the older Kayne came to say his prayers.

In the same year, a critic discusses Elmer Rice’s On Trial, an influential 1911 stage play. Rice employs

a dramatic technique which up to its time was probably unique, though since then the ever recurrent “flash back” of the movies has made the trick an old story.

During the 1930s, although some critics and filmmakers employed older terms like “switch back” and “retrospect,” flashback seems to have become the standard label. It denoted any shot or scene that breaks into present-time action to show us something that happened in the past. It probably speaks to the intuitive and informal nature of filmmaking that writers and directors didn’t feel a need to name a technique that they were using confidently for two decades.

The early flashback films pretty much set the pattern for what would come later. Turim shows that all the sorts we find today have their precedents in the 1910s and 1920s. Adapting her typology a little bit, we can distinguish between character-based flashbacks and “external” ones.

A character-based flashback may be presented as purely subjective, a person’s private memory, as in Letter to Three Wives or The Pawnbroker or Across the Universe. There’s also the flashback that represents one character’s recounting of past events to another character, a sort of visual illustration of what is told. This flashback is often based on testimony in a trial or investigation (Mortal Thoughts, The Usual Suspects), but it may simply involve a conversation, as in Leave Her to Heaven, Titanic, or Slumdog Millionaire. It can also be triggered by a letter or diary, as happens with the doubly-embedded journals in The Prestige.

An alternative is to break with character altogether and present a purely objective or “external” flashback. Here an impersonal narrating authority simply takes us back in time, without justifying the new scene as character memory or as illustration of dialogue. The external flashback is uncommon in classic studio cinema (although see A Man to Remember, 1938) but was common in the 1900s and 1910s and has returned in contemporary cinema. Typically the film begins at a point of crisis before a title appears signaling the shift to an earlier period. Recent examples are Michael Clayton (“Three days earlier”), Iron Man (“36 Hours Before”), and Vantage Point (“23 Minutes Earlier”).

In current movies, flashbacks can fall between these two possibilities. Are the flashbacks in The Good Shepherd the hero’s recollections (cued by him staring blankly into space) or more objective and external, simply juxtaposing his numb, colorless life with the past disintegration of his family? The point would be relevant if we are trying to assess how much self-knowledge he gains across the present-time action of the film.

Rationales for the flashback

What purposes does a flashback fulfill? Why would any storyteller want to arrange events out of chronological order? Structurally, the answers come down to our old friends causality and parallelism.

Most obviously, a flashback can explain why one character acts as she or he does. Classic instances would be Hitchcock’s trauma films like Spellbound and Marnie. A flashback can also provide information about events that were suppressed or obscured; this is the usual function of the climactic flashback in a detective story, filling in the gaps in our knowledge of a crime.

By juxtaposing two incidents or characters, flashbacks can enhance parallels as well. The flashbacks in The Godfather Part II are positioned to highlight the contrasts between Michael Corleone’s plotting and his father’s rise to power in the community. Citizen Kane’s flashbacks are famous for juxtaposing events in the hero’s life to bring out ironies or dramatic contrasts.

Of course, flashbacks need not explain or clarify things; they can make things more complicated too. We tend to think of the “lying flashback” as a modern invention (a certain Hitchcock film has become the prototype), but Turim shows that The Goose Woman (1925) and Footloose Widows (1926) did the same thing, although not with the same surprise effect. Kristin points out to me that an even earlier example is The Confession (1920), in which a witness at a trial supplies two different versions of a killing we have already (sort of) seen.

At the limit, flashbacks can block our ability to understand characters and plot actions. This is perhaps best illustrated by Last Year at Marienbad, but the dynamic is already there in Jean Epstein’s La Glace à trois faces (“The Three-Sided Mirror,” 1927).

I argue in Poetics of Cinema that, at bottom, flashbacks are tactics fulfilling a broader strategy: breaking up the story’s chronological order. You can begin the film at a climactic moment; once the viewers are hooked, they will wait for you to move back to set things up. You can create mystery about an event that the plot has skipped over, then answer the question through a flashback. You can establish parallels between past and present that might not emerge so clearly if the events were presented in 1-2-3 order. Consequently, you can justify the switch in time by setting up characters as recalling the past, or as recounting it to others.

Having a character remember or recount the past might seem to make the flashback more “realistic,” but flashbacks usually violate plausibility. Even “subjective” flashbacks usually present objective (and reliable) information. More oddly, both memory-flashbacks and telling-flashbacks usually show things that the character didn’t, and couldn’t, witness.

I don’t suggest that recollections and recountings are merely alibis for time-juggling. They bring other appeals into the storytelling mix, such as allegiance with characters, pretexts for point-of-view experimentation, and so on. Still, the basic purpose of nonchronological plotting, I think, is to pattern information across the film’s unfolding so as to shape our state of knowledge and our emotional response in particular ways. Scene by scene and moment by moment, flashbacks play a role in pricking our curiosity about what came before, promoting suspense about what will happen next, and enhancing surprise at any moment.

A trend becomes a tradition

When The Power and the Glory was released in August 1933, it was part of a cycle of flashback films. The Trial of Mary Dugan (1929), The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932), and other courtroom films rendered testimony in flashbacks. A film might also wedge a brief or extended flashback into an ongoing plot. The most influential instance was probably Smilin’ Through (1931), which is notable for using a crane shot through a garden to link present and past.

When The Power and the Glory was released in August 1933, it was part of a cycle of flashback films. The Trial of Mary Dugan (1929), The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932), and other courtroom films rendered testimony in flashbacks. A film might also wedge a brief or extended flashback into an ongoing plot. The most influential instance was probably Smilin’ Through (1931), which is notable for using a crane shot through a garden to link present and past.

Also well-established was the extended insert model. Here we start with a critical situation that triggers a flashback (either subjective or external), and this occupies most of the movie. Digging around, I found these instances, but I haven’t seen all of them; some don’t apparently survive.

- Behind the Door (1919): An old sea salt recalls life in World War I and, back in the present, punishes the man responsible for his wife’s death. A ripoff of Victor Sjöström’s Terje Vigen (1917)?

- An Old Sweetheart of Mine (1923): A husband goes through a trunk in an attic and finds a memento that reminds him of childhood sweetheart. The pair grow up and marry, facing tribulations. At the end, back in the present, she comes to the attic with their kids.

- His Master’s Voice (1925): Rex the dog is welcomed home from the war. An extended flashback shows his heroic service for the cause, and back in the present he is rewarded with a parade.

- Silence (1926): A condemned man explains the events that led up to the crime. Back in the present, on his way to be executed, he is saved.

- Forever After (1926): On a World War I battlefield, a soldier recalls what brought him there.

- The Woman on Trial (1927): A defendant recalls her past.

- The Last Command (1928): One of the most famous flashback films of the period. An old movie extra recalls his life in service of the tsar.

- Mammy (1930): A bum reflects on the circumstances leading him to a life on the road.

- Such is Life (1931): A ghoulish item. A fiendish scientist confronts a young man with the corpse of the woman he loves. A flashback to their romance ensues.

- The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931; often cablecast on TCM): A young wife bored with her husband is told the story of a neighbor woman who couldn’t settle down.

- Two Seconds (1932): A man about to be executed remembers, in the two seconds before death, what led him here. A more mainstream reworking of a premise of Paul Fejos’s experimental Last Moment (1928), which is evidently lost.

An interesting variant of this format is Beyond Victory, a 1931 RKO release. The plot presents four soldiers on the battlefield, each one recalling his courtship of the woman he loves back home. The principle of assembling flashbacks from several characters was at this point prised free of the courtroom setting, and multiple-viewpoint flashbacks became important for investigation plots like Affairs of a Gentleman (1934), Through Different Eyes (1942), The Grand Central Murder (1942), and of course Citizen Kane, itself a sort of mystery tale.

Why this burst of flashback movies? It’s a good question for research. One place to look would be literary culture. The technique of flashback goes back to Homer, and it recurs throughout the history of both oral and written narrative. Literary modernism, however, made writers highly conscious of the possibility of scrambling the order of events. From middlebrow items like The Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927) to high-cultural works by Dos Passos and Faulkner, elaborate flashbacks became organizing principles for entire novels. It’s likely that Sturges, a Manhattanite of wide literary culture, was keenly aware of this trend.

It’s just as likely that he noticed similar developments in another medium. By 1931, when Katharine Seymour and J. T. W. Martin published How to Write for Radio (New York: Longmans, Green), they could devote considerable discussion to frame stories and flashbacks in radio drama (pp. 115-137). Especially interesting for Sturges’ film, radio programs were letting the voice of the announcer or the storyteller drift in and out of the action that was taking place in the past.

For whatever reasons, the technique became more common. The year 1933 saw several flashback films besides The Power and the Glory. In the didactic exploitation item Suspicious Mothers, a woman recounts her wayward path to redemption. Mr. Broadway offers an extensive embedded story using footage from another film (a common practice in the earliest days). Terror Aboard begins with the discovery of corpses on a foundering yacht, followed by an extensive flashback tracing what led up the calamity. A borderline case is the what-if movie Turn Back the Clock (1933). Ever-annoying Lee Tracy plays a small businessman run down by a car. Under anesthesia, he reimagines his life as it might have been had he married the girl he once courted. Call it a rough draft for the “hypothetical flashbacks” that Resnais was to exploit in his great La Guerre est finie.

The point of this cascade of titles is that in writing The Power and the Glory, Sturges was working with a set of conventions already in wide circulation. His inventiveness stands out in two respects: the handling of voice-over and the ordering of the flashbacks.

Now I’m about to divulge details of The Power and the Glory.

Narratage, anyone?

The film begins with what became a commonplace opening gesture of film, fiction, and nonfiction biography: the death of the protagonist. We are at the funeral of Thomas Garner, railroad tycoon. His best friend and assistant Henry slips out of the service. After visiting the company office, Henry returns home. Sitting in the parlor with him, his wife castigates Garner as a wicked man. “It’s a good thing he killed himself.” So we have the classic setup of retrospective suspense: We know the outcome but become curious about what led up to it.

Henry’s defense of Garner launches a series of flashbacks. As a boyhood friend, Henry can take us to three stages of the great man’s life: adolescence, young manhood, and late middle age. Scenes from these time periods are linked by returns to the narrating situation, when Henry’s wife will break in with further criticisms of Garner.

Sturges boasted in a letter to his father: “I have invented an entirely new method of telling stories,” explaining that it combines silent film, sound film, and “the storytelling economy and the richness of characterization of a novel.” At the time, the Paramount publicists trumpeted that the film employed a new storytelling technique labeled narratage, a wedding of “narrating” and “montage.” One publicity item called it “the greatest advance in film entertainment since talking pictures were introduced.” Hyperbole aside, what did Sturges have in mind?

There is evidence that some screenwriters were rethinking their craft after the arrival of sound filming. Exhibit A is Tamar Lane’s book, The New Technique of Screen Writing (McGraw-Hill, 1936). Lane suggests that the talking picture’s promise will be fulfilled best by a “composite” construction blending various media. From the stage comes dialogue technique and sharp compression of action building to a strong climax. From the novel comes a sense of spaciousness, the proliferation of characters, a wider time frame, and multiple lines of action. Cinema contributes its own unique qualities as well, such as the control of tempo and a “pictorial charm” (p. 28) unattainable on the stage or page.

Vague as Lane’s proposal is, it suggests a way to think about the development of Hollywood screenwriting at the time. Many critics and theorists believed that the solution to the problem of talkies was to minimize speech; this is still a common conception of how creative directors dealt with sound. But Lane acknowledged that most films would probably rely on dialogue. The task was to find engaging ways to present it. Several films had already explored some possibilities, the most notorious probably being Strange Interlude (1932). In this MGM prestige product, the soliloquys spoken by characters in O’Neill’s play are rendered as subjective voice-over. The result, unfortunately, creates a broken tempo and overstressed acting. A conversation will halt, and through changes of facial expression the performer signals that what we’re now hearing is purely mental.

The Power and the Glory responds to the challenge of making talk interesting in a more innovative way. For one thing, there is the sheer pervasiveness of the voice-over narration. We’re so used to seeing films in which the voice-over commentary weaves in and out of a scene’s dialogue that we forget that this was once a rarity. Most flashback films in the early sound era had used the voice-over to lead into a past scene, but in The Power and the Glory, Henry describes what we see as we see it.

Most daringly, in one scene Henry’s voice-over substitutes for the dialogue entirely. Young Tom and Sally are striding up a mountainside, and he’s summoning up the nerve to propose marriage. What we hear, however, is Henry at once commenting on the action and speaking the lines spoken by the couple, whose voices are never heard.

This scene, often commented upon by critics then and now, seems have exemplified what Sturges late in life recalled “narratage” to be. Describing that technique in his autobiography, he wrote: “The narrator’s, or author’s, voice spoke the dialogue while the actors only moved their lips” (p. 272).

So one of Sturges’ innovations was to use the voice-over not only to link scenes but to comment on the action as it played out. In her pioneering book Invisible Storytellers: Voice-Over Narration in American Fiction Film (Univesity of California Press, 1988), Sarah Kozloff has argued that the pervasiveness of Henry’s narration has no real precedent in Hollywood, and few successors until 1939 (pp. 31-33). (There’s one successor in Sacha Guitry’s Roman d’un tricheur.) The novelty of the device may have led Sturges and Howard toward redundancies that we find a little labored today. The transitions into the past from the frame story are given rather emphatically, with Henry’s voice-over aided by camera movements that drift away from the couple. (Compare the crisp shifts in Midnight Mary, below.) Henry’s comments during the action are sometimes accentuated by diagonal veils that drift briefly over the shot, as if assuring us that this speech isn’t coming from the scene we see.

The “montage” bit of “narratage” also invokes the idea of a series of sequences guided by the voice-over narrator. The concept might also have encompassed the most famous innovation of The Power and the Glory: Sturges’ decision to make Henry’s flashbacks non-chronological.

Even today, most flashback films adhere to 1-2-3 order in presenting their embedded, past-tense action. But Sturges noticed that in real life people often recount events out of order, backing and filling or free-associating. So he organized The Power and the Glory as a series of blocks. Each block contains several scenes from either boyhood, youth, or middle age. Within each block, the scenes proceed chronologically, but the narration skips around among the blocks.

For example, a block of boyhood scenes gives way to a set showing Garner, now in middle age, ordering around his board of directors. The next cluster of flashbacks returns to Garner’s youth and his courtship of his first wife, Sally. Then we are carried back to his middle age, with scenes showing Garner alienated from Sally and his son Tommy but also attracted to the young woman Eve. And from there we return to Garner’s early married life with Eve.

To keep things straight, Sturges respects chronology along another dimension. Not only do the scenes within each block follow normal order, but the plotlines developing across the three phases of Garner’s life are given 1-2-3 treatment. In one block of flashbacks, we see Tom and Sally courting. When we return to that stage of their lives in another block, they are happily married. The next time we see Garner as a young man, he is improving himself by attending college. The later romance with Eve develops in a similar step-by-step fashion across the blocks devoted to middle age.

A major effect of the shuffling of periods is ironic contrast. Maureen Turim points out that seeing different phases of Garner’s life side by side points up changes and disparities. In his youth, Tom watches the birth of his son with awe; in the next scene, we are reminded what a wastrel young Tommy turned out to be.

The juxtaposition of time frames also nuances character development. As Sally ages, she turns into something of a nag, quarreling with her husband and pampering Tommy. But in the next sequence we see her young, ambitiously pushing Tom to succeed and willing to undergo sacrifice by taking up his job as a railroad track-walker. The next scenes show Tom in class and in a bar while Sally walks the desolate tracks in a blizzard. She has given up a lot for her husband. In the next scene, set in middle age, Garner confesses his love to Eve but says he could never leave Sally, and the juxtaposition with Sally’s solitary track-walking suggests that he recognizes her sacrifice. And in the following scene, when Sally comes to Garner’s office, she admits that she has become disagreeable and asks if they couldn’t take a trip to reignite their love. The juxtaposition of scenes has turned a caricatural shrew into a woman who is a more complex mixture of devotion, disenchantment, and self-awareness.

Other characters aren’t given this degree of shading—Tommy is pretty much a wastrel, Eve a vamp—but another married couple deepens the central parallel. Meek Henry is dominated by his wife, but by the end she is chastened by what she learns of Garner’s real motives. Critic Andy Horton, in his helpful introduction to Sturges’ published screenplay, indicates that this couple adds a note of contentment to what is otherwise a pretty sordid melodrama of adultery and quasi-incest.

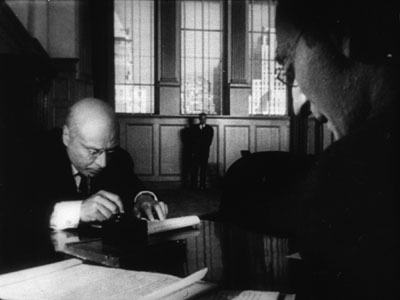

The innovative flashbacks and voice-overs are an important part of the film’s appeal, but director William K. Howard supplied some craftsmanship of his own. Particularly striking are some silhouette effects, low angles, and deep-focus compositions that underscore the parallels between Sally’s suicide and Garner’s impending death.

The original screenplay suggests that Sturges intended to push his innovations further. About halfway through, he starts to break down the time-blocks. In the script, Sally visits Garner while he’s working on a bridge. The next scene shows their son Tommy already grown and spoiled, being taken back into his father’s good graces. Then the script returns to the bridge, where Sally tells Tom she’s pregnant. The interruption of the bridge scene reminds us of how badly their child turned out.

The script jumps back to the birth of the baby. In the film the birth scene plays out in its entirety, but in the screenplay Sturges cuts it off by the scene (retained in the film) showing Garner’s marriage to Eve. The final moments of the birth scene, when Garner prays (“Thou art the power and the glory”), become in the script the very end of the film. Coming after Tom’s death at the hand of his son, this epilogue is a bitter pill, rendered all the harder to take by providing no return to Henry and his wife.

The greater fragmentation of the second part of the script, along with Garner’s death as a sort of murder-suicide and the failure to return to the narrating frame, is striking. It’s as if Sturges felt he could take more chances, counting on his viewers’ familiarity with current flashback conventions and on his film’s firmly established time-shuttling method. But if, as sources report, Sturges’ script was initially filmed exactly as written, then it seems likely that the film’s June 1933 preview provoked the changes we find in the finished product. “The first half of the picture,” he remarked in a letter, “went magnificently, but the storytelling method was a little too wild for the average audience to grasp and the latter half of the picture went wrong in several spots. We have been busy correcting this and the arguments and conferences have been endless.”

Even the compromised film proved difficult for audiences. Tamar Lane, proponent of the “composite” form suitable for the sound cinema, felt that the “retrospects” in The Power and the Glory were too numerous and protracted. Nonetheless, he praised it for its “radical and original cinema handling” (p.34). That handling rested upon tradition—a tradition that in turn encouraged innovations. Once flashbacks had become solid conventions, Sturges could risk pushing them in fresh directions.

Mary remembers

Finally, two more flashy flashback movies from 1933. Some spoilers.

Midnight Mary (MGM, William Wellman) works a twist on the courtroom template. The defendant Mary Martin is introduced jauntily reading a magazine while the prosecutor demands that the jury find her guilty of murder. This also sets up a nice little motif of shots highlighting Loretta Young’s lustrous eyes. The motif pays off with a soft-focus shot of her in jail just before the climax.

As the opening scene ends, Mary is led to a clerk’s office to wait for the verdict. There’s an automatic dose of suspense (Will she be found guilty?) but there’s also considerable curiosity: Whom has she killed? How was she caught?

These questions won’t be answered for some time. Lounging in the clerk’s office, Mary runs her eye runs across the annual reports filling his shelves. The flashbacks, which comprise most of the film, are introduced as close-ups of the volumes’ spines—1919, 1923, 1926, 1927, and so on up to the present. They serve as neatly motivated equivalents of those clichéd calendar pages that ripple through montage sequences of the 1930s.

The flashbacks are motivated as subjective; Mary doesn’t recount her life to the clerk but simply reviews it in her mind. Unlike the flashbacks in The Power and the Glory, they are chronological and without gaps. Nothing is skipped over to be revealed later. As usual, though, once Mary’s recollections have triggered the rearrangement of story order, the flashbacks are filmed as any ordinary scenes would be, including bits of action that she isn’t present to witness. The film is a good example of using the extended-flashback convention chiefly to delay the resolution of the climactic action. Told in chronological order, Mary’s tale of woe would have had much less suspense.

Transitions between present and past are areas open to innovation, and early sound filmmakers took advantage of them. In Midnight Mary, the long flashback closes with gangsters pounding on the door of Mary’s boudoir; this sound continues across the dissolve to the present, with Mary roused from her reverie by a knock on the clerk’s office door. Earlier, one transition into the past begins with Mary blowing cigarette smoke toward the bound volumes on the shelf.

Dissolve to a close-up of one book as smoke wafts over it, and then to a shot of Mary’s gangster boyfriend blowing cigarette smoke out before he sets up a robbery..

At one point the narration supplies a surprise by abruptly shifting into the present. Once Mary has become a prostitute, she is slumped over a barroom table in sorrow, while her pal Bunny consoles her. In a tight shot, Bunny (Una Merkel, always welcome), leans over and says: “Oh, what’s the diff, Mary? A girl’s gotta live, ain’t she?”

Cut directly to the present, with Mary murmuring: “Not necessarily, Bunny. The jury’s still out on that.”

Mary’s reply casts Bunny’s question about needing to live in a new light, since Mary is facing execution, and the use of the stereotyped phrase, “The jury’s still out,” now with a double meaning, reminds us of the present-tense crisis. It is a more crisp and concise link than the transitions we get in The Power and the Glory. But then, Wellman has no need for continuous voice-over, which gives the Sturges/ Howard film its more measured pace.

Filmmakers were concerned with finding storytelling techniques appropriate to the sound film, and these unpredictable links between sequences became characteristic of the new medium. Similar links had appeared in silent films, but they gained smoothness and extra dimensions of meaning when the images were blended with dialogue or music. For more on transitional hooks, go here.

Nora and narratage

The hooks between scenes are perhaps the least outrageous stretches of The Sin of Nora Moran, a Majestic release that, thanks to a gorgeous restoration and a DVD release, has rightly earned a reputation as the nuttiest B-film of the 1930s.

It is a flashback frenzy, boxes within boxes. A District Attorney tells the governor’s wife to burn the apparently incriminating love letters she’s found. In explaining why, the D. A. introduces a flashback (or is it a cutaway?) to Nora in prison. We then move into Nora’s mind and see her hard life, the low point occurring when she’s raped by a lion tamer.

Now we start shuttling between the D. A. telling us about Nora and Nora remembering, or dreaming up, traumatic events. At some points, characters in her flashbacks tell her that what she’s experiencing is not real. In one hazy sequence, her circus pal Sadie materializes in her cell to remind Nora that she killed a man. (Actually, she didn’t.) At other moments Nora’s flashbacks include moments in which she says that if she does something differently, it will change—it being the outcome of the story. At this point another character will point out that they can’t change the outcome because it has already happened . . . of course, since this is a flashback.

By the end, after the governor has had his own flashback to the end of his affair with Nora and after she appears as a floating head, things have gotten out of hand. The rules, if there are any, keep changing. And the whole farrago is propelled by furious montage sequences built out of footage scavenged from other films.

Publicity and critical response around The Sin of Nora Moran implied that the movie followed the “narratage” method. There was surely some influence. Scenes contain fairly continuous voice-over commentary, and director Phil Goldstone occasionally drops in the diagonal veil used in The Power and the Glory. But on the whole this delirious Poverty Row item falls outside the strict contours of Sturges’ experiment. Nora Moran blurs the line separating flashbacks and fantasy scenes, and it illustrates how easily we can lose track of what time zone we’re in. Watching it, I had a flashback of my own—to Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart, another compilation revealing that Hollywood conventions are only a few steps from phantasmagorias.

Unwittingly, Nora Moran’s peculiarities point forward to the flashback’s golden age, the 1940s and early 1950s. Then we got contradictory flashbacks, flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks, flashbacks from the point of view of a corpse (Sunset Boulevard) or an Oscar statuette (Susan Slept Here). Filmmakers knew they had found a good thing, and they weren’t going to let it go.

The original screenplay of The Power and the Glory is included in Andrew Horton, ed., Three More Screenplays by Preston Sturges (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998). Sturges’ reflections from the late 1950s are to be found in Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges: His Life in His Words, ed. Sandy Sturges (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990). The quotations from Sturges’ letters and from publicity about “narratage” can be found in Diane Jacobs, Christmas in July: The Life and Art of Preston Sturges (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 123-129 and James Curtis, Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982), 87.

My citatations of literary uses of the term come from Elliott Field, “A Philistine in Arcady,” The Black Cat 24, 10 (July 1919), 33; Fitzgerald’s The Beautiful and Damned (1922), available here, 433; Samuel A. Eliot, Jr., ed., Little Theater Classics vol. 3 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1921), 120; The Outlook (11 May 1921), 49, available here; review of His Children’s Children, quoted in Turim p. 29; commentary on On Trial, in The New York Times (25 March, 1923), X2.

For more on the history of flashback construction, apart from Maureen Turim’s Flashbacks in Film, see Barry Salt’s Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis, 2nd ed. (London: Starword, 1992), especially 101-102, 139-141. There are discussions of the technique throughout David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), especially 42-44.

P.S. 15 November 2015: 1940s flashback technique is surveyed in my Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

Gradation of emphasis, starring Glenn Ford

DB here:

Charles Barr’s 1963 essay “CinemaScope: Before and After” has become a classic of English-language film criticism. (1) It proffers a lot of intriguing ideas about widescreen film, but one idea that Barr floated has more general relevance. I’ve found it a useful critical tool, and maybe you will too.

Grading on a curve

Barr called the idea gradation of emphasis. Here’s what he says:

The advantage of Scope [the 2.35:1 ratio] over even the wide screen of Hatari! [shot in 1.85:1] is that it enables complex scenes to be covered even more naturally: detail can be integrated, and therefore perceived, in a still more realistic way. If I had to sum up its implications I would say that it gives a greater range for gradation of emphasis. . . The 1:1.33 screen is too much of an abstraction, compared with the way we normally see things, to admit easily the detail which can only be really effective if it is perceived qua casual detail.

The locus classicus exemplifying this idea comes in River of No Return (1954). When Kay is lifted off the raft, she loses her grip on her wickerwork bag and it’s carried off by the current. (See the frame surmounting this entry.) Kay and her boyfriend Harry are rescued by the farmer Matt. As all three talk in the foreground, the camera catches the bundle drifting off to the right.

Even when the men turn to walk to the cabin, Preminger gives us a chance to see the bundle still drifting downstream, centered in the frame.

The point of this shot, Barr and V. F. Perkins argued, is thematic. As Kay moves from the mining camp to the wilderness, she will lose more and more of her dance-hall trappings and be ready to accept a new life with Matt and Mark. The last shot of the film shows her final traces of her old life cast away.

Cutting in to Kay’s floating bag would have been heavy-handed; if you stress a secondary element too much, it becomes primary. Barr reminds us that any film shot can include the most important information, as well as information of lesser significance. A film can achieve subtle effects by incorporating details in ways that make them subordinate as details and yet noticeable to the viewer. Or at least the alert viewer.

In Poetics of Cinema, I wrote an essay on staging options in early CinemaScope, and Barr’s idea helped me illuminate some of the strategies I discuss. (For earlier comments on Barr on Scope and River of No Return, see my article elsewhere on this site.) Today I want to consider how the notion of gradation of emphasis has a more general usefulness.

Barr contrasts the open, fluid possibilities of CinemaScope with two other stylistic approaches, both found in the squarer 1.33 format. The first approach is the editing-driven one he finds in silent film. This tends to make each shot into a single “word,” and meaning arises only when shots are assembled. Barr associates this approach with Griffith and Eisenstein. The second approach, only alluded to, is that of depth staging and deep-focus shooting, typically associated with sound cinema of the late 1930s and into the 1950s.

Both of these approaches, montage and single-take depth, lack the subtle simplicity of Scope’s gradation of emphasis.

There are innumerable applications of this [technique] (the whole question of significant imagery is affected by it): one quite common one is the scene where two people talk, and a third watches, or just appears in the background unobtrusively—he might be a person who is relevant to the others in some way, or who is affected by what they say, and it is useful for us to be “reminded” of his presence. The simple cutaway shot coarsens the effect by being too obvious a directorial aside (Look who’s watching) and on the smaller [1.33] screen it’s difficult to play off foreground and background within the frame: the detail tends to look too obviously planted. The frame is so closed-in that any detail which is placed there must be deliberate—at some level we both feel this and know it intellectually.

To see Barr’s point, consider a shot like this one from Framed (1947).

The shot, rather typical of 1940s depth staging, displays an almost fussy precision about fitting foreground and background together. That bartender, for instance, stands squeezed into just the right spot. (2) Barr claims that we sense a certain contrivance when primary and secondary centers of interest are jammed into the 1.33 frame like this.

We don’t sense the same contrivance in the widescreen format, he suggests. Barr assumes, I think, that the sheer breadth of any Scope frame will include areas of little consequence, whereas that’s comparatively rare in a 1.33 composition. This is an intriguing hunch, but uninformative patches of the frame may not be intrinsic to the Scope technology. Perhaps the fairly neutral and inexpressive uses of Scope that dominate the early 1950s, the sense of empty and insignificant acreage stretching out on all sides, make us expect that little of importance will be found there. Accordingly, directors can create a sense of discovery when we spot a significant detail in this stretch of real estate.

Anyhow, Barr indicates that if static deep-space staging made the frame too constrained, 1930s and 1940s directors who combined depth with camera movement created more spacious and fluid framings. He suggests that Mizoguchi, Renoir, and others anticipated the possibilities of Scope.

Greater flexibility was achieved long before Scope by certain directors using depth of focus and the moving camera (one of whose main advantages, as Dai Vaughan pointed out in Definition 1, is that it allows points to be made literally “in passing”). Scope as always does not create a new method, it encourages, and refines, an old one (pp. 18-19).

Barr believes that Scope positively encouraged gradation of emphasis, and that widescreen directors of the 1950s and 1960s have made the most fruitful use of the strategy. But he allows directors of all periods utilized gradation of emphasis, even in the standard 1.33 format. This is, I believe, a powerful idea.

Before Scope: Making the grade

Barr’s discussion of silent cinema, relying on notions of editing associated with Griffith and Soviet directors like Eisenstein, is done with a broad brush, but it’s typical of the period in which he was writing. We didn’t know much about silent filmmaking until archivists started to exhume important work in the 1970s. It’s no exaggeration to say that we haven’t really begun to understand the first twenty-five years of cinema until fairly recently.

In a way, the staging-driven tradition of the 1910s, which I’ve often mentioned on this site (here and here and here), exemplifies some things that Barr would approve of. Directors of that period made extraordinary use of the frame and compositional patterning. They staged action laterally, in depth, or both. They let shots ripen slowly or burst with new information. This approach to using the full frame (with only occasionally cut-in elements) has come to be called the tableau style, emphasizing its similarity to composition of a painting—although we shouldn’t forget that these films are moving paintings, and the compositions are constantly changing. The result is that emphasis tends to be modulated and distributed among several points of interest.

Central to this strategy, I think, was camera distance. American directors tended to set the camera moderately close, cutting figures off at the knees or hips, and by taking up more frame space, the foreground actors tended to limit the area available for depth arrangement or for significant detail.

This shot from Thanhouser’s The Cry of the Children (1912) is a rough 1910s equivalent of the crammed shot from Framed above. (See also the tightly composed shots from DeMille’s Kindling (1915) here.)

The European directors, by contrast, tended to let the scene play out in more distant shots, creating spacious framings of a sort that would be reinstituted in early CinemaScope. Consider this shot from Holger-Madsen’s Towards the Light (Mod Lyset, 1919) and another from Island in the Sun (1957).

Both, it seems to me, have the type of open composition and the foreground/ background interplay that Barr praises in his article.

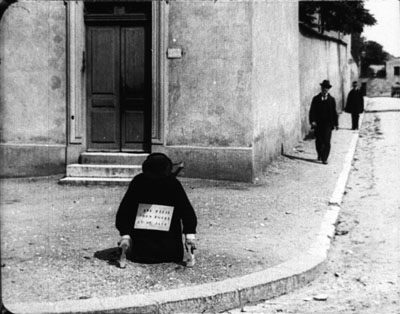

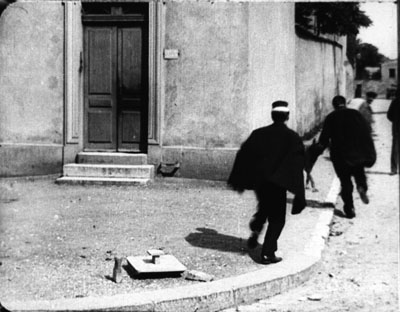

We can go back further. The Lumière brothers’ cameramen made fiction films as well as documentaries, and we occasionally find moments that suggest early efforts at gradation of emphasis. In Le Faux cul-de-jatte (1897), an apparent amputee is begging in the foreground while in the distance a man is walking down the street.

A cop crosses the street from off right and follows the pedestrian.

As the foreground fills up, the man we’ve seen in the distance gives the beggar some money.

As he goes out left, the cop is still approaching, and a vagrant dog appears.

The cop comes to the beggar, partially blocking the dog, who takes care of other business. (Not everything in this movie is staged.)

The cop checks the beggar’s papers and finds them to be suspect. The fake amputee jumps up and races off in the distance, with the cop pursuing.

As with many staged Lumière shorts, several figures converge in the foreground in order to create a culminating piece of action. Here the distant man and the cop, both secondary centers of interest, serve as a kind of timer, assuring us that something will happen when they meet at the beggar.

These are just some quick examples. We should continue to study the ways in which, with minimal use of editing, early filmmakers found ingenious ways to create gradation of emphasis. (2)

Some uses of grading

Barr, like most critics writing for the British journal Movie, was sensitive to the ways in which technique has implications for character psychology and broader thematic meanings. Kay’s bundle is one point along a series of changes in her character and her situation. But gradation of emphasis can serve more straightforward narrative purposes as well.

Consider our old friends, surprise and suspense. In the original 3:10 to Yuma (1957) Dan Evans is confronting the ruthless outlaw Ben Wade.

We get a string of reverse shots.

Then in one shot of Wade, without warning, a shadowy figure emerges out of focus in the left background.

Now we realize that Evans has been diverting Wade from the fact that the sheriff’s posse is surrounding him. Now we wait for Wade to discover it; how will he react?

While we’re on Glenn Ford, another nice example occurs in Framed. Mike Lambert has been romancing a woman named Paula, but we know that she and her lover Steve are plotting to fake Steve’s death and substitute Mike’s body.

She brings Mike to Steve’s elegant country house, having presented Steve as someone she knows only slightly. When Mike goes into the bathroom to wash up, we notice something important behind him.

With Mike at the sink, we have plenty of time to recognize Paula’s robe. Director Richard Wallace prolongs the suspense by giving us a new shot of Mike in the mirror, with the robe no longer visible.

But when Mike turns to leave, a pan following him brings him face to face with what we saw, accentuated by a track forward.

We get Mike’s reaction shot, followed by a cut to Steve and Paula downstairs, suspecting nothing. “So far, so good,” says Steve, looking upward at the bathroom.

The rest of the scene will play out with Mike aware that they’re deceiving him. As often happens with suspense, we know more than any one character: We know the couple’s scheme and Mike doesn’t, but they don’t (yet) know that Mike is now on his guard.

This isn’t as subtle a case as River of No Return, but I suspect that it’s more typical of the way Hollywood filmmakers use gradation of emphasis. Paula’s bathrobe is a good example of what I called in The Classical Hollywood Cinema the strategy of priming: planting a subsidiary element in the frame that will take on a major role, even if initially its presence isn’t registered strongly. My example in CHC was a coat rack in the Dean Martin/ Jerry Lewis comedy The Caddy (1953). In effect, the distant pedestrian in the Lumière film is an early example of priming.

Howard Hawks adopts the Lumière technique in order to sustain a flow of dialogue in Twentieth Century (1934). Here the foreground conversation is accompanied by a procession of people emerging in the distance and stepping up to take part.

The shot concludes, as does the shot of Faux cul-de-jattes, with a retreat from the camera.

The priming of secondary elements here, the summoning of the train attendant and the conductor, obeys Alexander Mackendrick’s dictum that the director ought to construct each shot so as to prepare for what will come next.

As Barr indicates, the idea of gradation shades insensibly off into general matters of cinematic expression. In The Devil Thumbs a Ride (1947), the bank robber has hitched a ride with an unassuming civilian, and they stop for gas. When the attendant shows a picture of his little girl, the robber gratuitously insults her. (“With those ears she’ll probably fly before she can walk.”)

Later, the station attendant hears a radio broadcast describing the fugitive. First he has his head cocked as he listens attentively, but then his gaze drifts to the picture of his little girl.

The attendant is the center of dramatic interest, but when he looks at the picture, so do we (primed by the view of it earlier). Instantly we understand that the attendant’s resolve to call the police springs partly from an urge to get even with the man who insulted his daughter. A minor instance, surely, but it illustrates Barr’s point that the notion of gradation of emphasis leads us to consider “the whole question of significant imagery.”

The more the merrier

Barr seems to favor a plain style; he prefers Preminger’s quiet framings to the rococo imagery of Aldrich’s Vera Cruz (1954). Presumably the famous shot above from Wyler’s Best Years of Our Lives (1946) would be too obviously composed for Barr’s taste.

But there is merit in considering how a secondary center of interest can vie for supremacy. André Bazin declared Wyler’s shot a bold stroke exactly because its self-conscious precision created a tension between what was primary and what was subordinate. (3) The action in the foreground is of dramatic interest because Homer has learned to play the piano, and this represents a phase of his coming to terms with his wartime disability. Yet the most consequential action is taking place in the distant phone booth, where Fred breaks up with Al’s daughter Peggy. The gradation of emphasis is inverted, and we wait in suspense to find out what happens. Bazin taught us to recognize that what appears to be primary may actually be creatively distracting us from the scene’s principal action. (4)

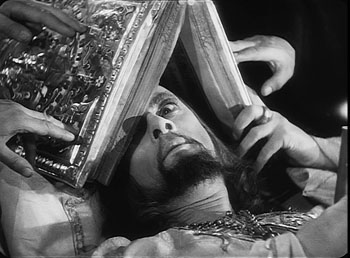

A director can also turn a primary center of interest into something secondary, but powerful. In one sequence of Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible I (1944), the apparently dying tsar is being prayed over by churchmen. Ever suspicious, he peers out from under the book, using only one eye.

As the scene develops, Prince Kurbsky meets Ivan’s wife and tries to seduce her. In the background an icon’s eye glares out, as if Ivan is watching them.

The single eye, which is a motif we find in other Eisenstein films, becomes a significant one throughout both parts of Ivan. More generally, this device manifests Eisenstein’s conception of polyphonic montage, which explored how the filmmaker can control all the various aspects of his images and make them weave throughout the film—promoting one at one moment, demoting it at another. (5)

Barr’s essay assumes that Eisenstein’s montage stripped each image down to a single meaning. In fact, though, Eisenstein wanted to multiply the sensuous and intellectual implications of each shot by weaving objects, gestures, body parts, musical motifs, and the like into an ongoing stylistic fabric. Each shot’s gradation of emphasis can suggest thematic parallels, deepen the drama, or heighten emotional expression, just as a complex score enhances an operatic scene.

Tati as well likes to create an interplay between primary and subsidiary centers of interest. Or rather, he sometimes abolishes our sense of what is primary and what isn’t. The crowded compositions of Play Time (1967) often bury their gags in a welter of inessential details. During the lengthy scene in the Royal Garden restaurant, a minor running gag involves the dyspeptic manager. He has just mixed some headache medicine with mineral water, but the action is easily lost within the tumultuous image. Even the soundtrack cues us only slightly, with a bit of fizz among the music and crowd noise.

As the manager lowers the glass, Hulot thinks it’s pink champagne being offered to him.

Rolling the stuff in his mouth, Hulot realizes his mistake as he earns a stare from the manager.

There is so much competing sound and activity in the shot that some viewers simply don’t notice this bit at all. In Play Time, gradation of emphasis is often flattened out, leaving us to rummage around the composition for the gag.

Some final notes

Barr was not particularly interested in the mechanics of how we come to notice something in the shot, be it primary or secondary in value. In On the History of Film Style, I suggested that many aspects of technique work to call attention to any element in the field. The filmmaker can put a something in motion, turn it to face us, light it more brightly, make it a vivid color, center it in the frame, have it advance to the foreground, have other characters look at it, and so on. These tactics can work together in a complex choreography. In Figures Traced in Light, I argued that they depend on the fact that we scan the frame actively; the techniques guide our visual exploration. (6)

You can see this guidance at work in most of the examples I’ve mentioned. In River of No Return, we are coaxed into noticing Kay’s bundle because we’re cued by movement (the bundle falls and drifts off), performance (she shouts, “My Things!” and stretches out her arm), music (we hear a chord as the bundle splashes), and framing (Preminger’s camera pans slightly as the trunk drifts away). The critic can refine our sense of the effects that a film arouses, but it’s one task of a poetics of cinema, as I conceive it, to examine the principles and processes that filmmakers activate in achieving those effects.

Finally, we might ask: To what extent do we find gradation of emphasis in current filmmaking? Today’s American cinema relies heavily on editing, using a style I’ve called intensified continuity. Each shot tends to mean just one thing, and once we get it we’re rushed on to the next. The unforced openness of the wide frame that Barr celebrated has been largely banned, in favor of tight singles—even in the 2.40 anamorphic format. It seems that most filmmakers are no longer concerned with gradation of emphasis within their shots.

To find this strategy surviving at its richest, I think we have to look overseas. If you want names: Angelopoulos, Tarr, Kore-eda, Jia, Hou. (7)

(1) It was published in Film Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 4 (Summer, 1963), 4-24. Unfortunately, it’s not available free online, nor is a complete version available in anthologies, so far as I know. If you have access to online journal databases, you can find it. Otherwise, off to the library w’ye!

(2) In the Poetics of Cinema piece (pp. 303-307), I argue that some early uses of Scope tried to approximate such tightly organized composition, despite technological barriers to focusing several planes of action.

(3) See André Bazin, “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work: Major Essays and Reviews from the Forties and Fifties, ed. Bert Cardullo, trans. Cardullo and Alain Piette (New York: Routledge, 1997), 14-16.

(4) Actually the phone booth is primed for our notice by earlier shots in Butch’s tavern. See On the History of Film Style, 225-228.

(5) For more on Eisenstein’s idea of polyphonic montage, see my Cinema of Eisenstein (New York: Routledge, 2005) and Kristin’s Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible: A Neoformalist Analysis (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981).

(6) For some empirical evidence of this guided scanning, see the work of Tim Smith at his website and in this entry on this site.

(7) I discuss some of these alternatives in On the History of Film Style and the last chapter of Figures Traced in Light.

Eternity and a Day.

PS 15 Nov. Two more items. First, if the ideas floated here intrigue you, you might want to take a look at an earlier entry on this site, called “Sleeves.”

Second, I had planned to include one more example, but forgot it. In Lumet’s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, Andy Hanson’s life is unraveling. We follow him back to his apartment, and as he enters on the extreme left, his wife Gina is visible sitting on the extreme right, her back to us.