Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

Captain Cinephilia: Scorsese strikes back

Brian McFadden, No One Is Safe: Martin Scorsese Roasts Your Fandom.”

DB here:

It started with a brief, almost offhand remark.

“I don’t see them,” [Scorsese] says of the MCU [Marvel Cinematic Universe]. “I tried, you know? But that’s not cinema. Honestly, the closest I can think of them, as well-made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances, is theme parks. It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.”

When I learned about this interview (Empire, November issue), I took it as simply a roundabout statement of personal taste. Scorsese doesn’t find Marvel movies, and perhaps other comic-book sagas of superheroes, to his taste. He gave them a fair shot, but he now no longer sees them. He considers them visceral stimulation, like carnivals or theme parks. They’re not cinema, if you consider cinema as emotional expression of psychological conflicts.

In the massive responses to Scorsese, people pointed out that viewers often respond emotionally to superhero films. They root for certain characters, they’re amused or thrilled by certain situations, and many claim to be deeply moved by the heroes and villains (Loki, even Thanos). In fact, it’s exactly the “emotional, psychological experiences” embedded in the Marvel and DC plots that some fans say distinguish them from crude comic-book movies that went before. Much the same could be said of the Bond films, which became more humanized with Quantum of Solace, though intermittently before.

As for the claim that the superhero films “aren’t cinema,” I wasn’t really upset. Over the decades we’ve heard that 1910s films “aren’t cinema” (too theatrical), or that adaptations of novels or plays “aren’t cinema” (too literary or stagebound), or that narrative films “aren’t cinema” (usually proposed by avant-gardists). When the claim relies on a notion of some cinematic essence (editing, or pure visual form) that’s missing from this or that movie, you might be able to have a productive conversation. But if “This isn’t cinema” comes down to “I don’t like films like this,” we’re back to personal taste.

On other occasions Scorsese went on to say a lot more. The ultimate result was a 7 November article in the New York Times. I think we should take this as his most thoroughgoing effort to explain his thinking. We can supplement that with some remarks he made in interviews and Q & A sessions.

Herewith my attempts to figure out Scorsese’s argument. Trying to sort this out might teach us some important things about film now.

Scorsese in defense of Cinema

Scorsese’s Times article, “I Said Marvel Movies Aren’t Cinema. Let Me Explain,” begins by disclaiming any hatred for Marvel movies as such. “The fact that the films themselves don’t interest me is a matter of personal taste and temperament.”

But everyone’s taste gets shaped by their moviegoing experience, and in his youth Scorsese was attracted to films from America and Europe. These yielded “revelation—aesthetic, emotional, and spiritual revelation.” The films were, he felt, about characters who were complex, sometimes contradictory in their minds and behavior.

Moreover, these films showed that cinema was an art form, one existing in both commercial and more experimental spheres. Hollywood studio output (Ford Westerns, Hitchcock thrillers), European imports (Bergman, Godard), and avant-garde work (Scorpio Rising)—all these showed that cinema had powers equal to those of music, dance, and literature. These films were technically accomplished, sometimes virtuoso, but at their hearts were intense, complex emotional appeals that assured that they would be watched for decades later.

Today the Marvel pictures, often skillfully made, lack “revelation, mystery, or genuine emotional danger.” They are repetitive, adhering to a basic formula, “defined as variations on a finite number of themes.” By contrast, the films of Paul Thomas Anderson, Claire Denis, Wes Anderson, and other directors offer new and unpredictable experiences, and they expand the possibilities of the art form. “The unifying vision of an individual artist” is essential to cinema.

It’s exactly the exploratory filmmakers who are being stifled by the Marvel releases, and indeed all the franchises. These more personal films aren’t just constrained by lower budgets; they can’t get much exposure on theatre screens either. “Around the world, franchise films are now your primary choice if you want to see something on the big screen.” Most filmmakers design their films for that scale and that communal experience, but the blockbuster films are pushing smaller pictures into streaming outlets.

The franchise mentality is a corporate one. The products are “market-researched, audience-tested, vetted, modified, revetted and remodified until they’re ready for consumption.” As often happens, the business constrains the art. But you might say, what about the old studio system? Wasn’t that as mercenary as today’s franchise juggernaut? No, because the studios set up a creative tension between the business end and the artistic end that yielded outstanding works, even masterpieces. Today’s franchise producers are indifferent to art and hold a view of film history that is both “dismissive and proprietary.”

As a result we have two domains: worldwide audiovisual entertainment vs. cinema. They overlap less and less, and it seems likely that the financial power of one will dominate and belittle the other.

I think that some of these arguments are plausible, while others deserve more probing.

Film art: Who’s the artist?

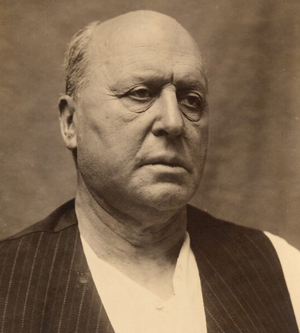

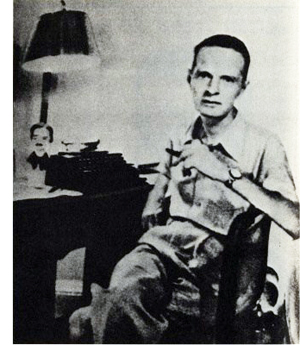

Andrew Sarris.

During the 1950s and 1960s, this general argument was promulgated by the so-called auteur critics around Cahiers du cinéma and was developed and promoted by Andrew Sarris in the US and Movie magazine in the UK. Scorsese was deeply influenced by these ideas. He was one of many cinephile directors-in-training who assumed that the best films bore the “unifying vision of the individual artist,” who was the auteur (author) of the film.

What was considered the “auteur theory” is too complicated to explore fully here. Minimally, it’s the idea that, all other things being equal, in many movies (often the best ones) the director can be considered the source of the film’s distinctive artistic qualities. The director may achieve this by exercising near-total control (e.g., Chaplin), or working with close collaborators (Powell and Pressburger, Donen and Kelly) or serving as a “filter” for the offerings of various contributors (probably most filmmakers).

This is the minimal case. The maximal one rests on the idea that once we make the director the central power, we then discover a “unifying vision.” At this level the distinctive features of form, style, and theme coalesce into a personal conception of human life. For Ford, that might include the value of traditions and the costs they demand of those subscribing to them. Hitchcock’s recurring concern, Robin Wood famously argued, is the realization that complacency, a trust in social order, is vulnerable to disruption.

The difference between the two versions I’m sketching isn’t hard and fast. Still, it often holds good. A friend, for instance, grants that Tony Scott is a distinctive filmmaker. “He just has nothing to say.” The idea that an auteur has something consistent and personal to “say,” deliberately or unconsciously, from film to film, is a hallmark of auteur criticism at its most ambitious. And the greatest auteurs, perhaps, show development in what they say across their careers. John Ford’s attitude toward the frontier can be said to change from The Iron Horse (1924) to Cheyenne Autumn (1964).

The minimalist auteur concept isn’t new. From the 1920s on, historians and critics often attributed creative authority to Griffith, Chaplin, De Mille, Hitchcock, and European and Soviet directors. And in most film industries, executives recognized that the director had the most responsibility for the film’s look and feel.

One revolutionary edge of auteur criticism was to discover auteurs nobody had noticed before–largely unknown filmmakers working alongside humbler folk. And the critics went further, suggesting that some of these filmmakers could be considered auteurs to the max.

Typically auteur critics didn’t examine the concrete context of production to determine who did what in particular cases. They inferred directorial expression by watching lots of films and tracing recurring strategies of style and theme. Sometimes they backed their conclusions up by interviews with–who else?–the director.

Minimal versions of the auteur idea are central to film culture now. Festivals promote directors, as do studio marketers. Movie lists in reference books and search sites give directors the pride of place. Variety and Hollywood Reporter reviews usually don’t name producers, cinematographers, and other contributors, but the director is always mentioned (and blamed or praised for the film). Academics and cinephile critics ascribe more maximalist “personal visions” to directors around the world, from David Lynch and Spike Lee to Wes Anderson to Wong Kar-wai and Jane Campion.

Auteur +genre = ?

Black Panther: Danai Gurira (Okoye), Ryan Coogler on the set.

Despite the prominence of some directors, they’re usually not what draws audiences. In most countries, the mass-market cinema is dominated by genres that are populated by well-known stars.

Sarris and others assumed that auteurs built upon the foundations provided by genre conventions and star images. Ford gave the Western a new force not only through his images and use of music but also by redefining the star personas of John Wayne and Henry Fonda. Hitchcock and Lang worked with and against the conventions of the thriller, while Ophuls gave the melodrama a melancholic elegance. Or so goes auteur gospel.

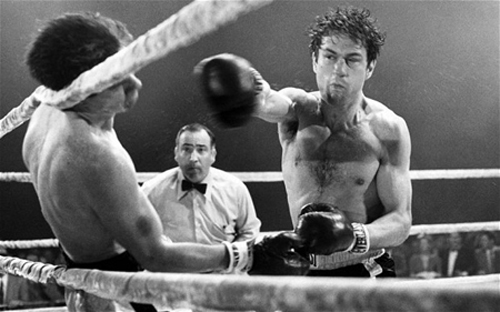

The 1970s New Hollywood auteurs embraced genre filmmaking as well. Bogdanovich, Coppola, Altman, Woody Allen, and others tested themselves in a variety of genres. Even Scorsese tried a “woman’s picture” (Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore), a musical (New York, New York), and a biopic (Raging Bull). They are only roughly parallel to today’s indie filmmaker who, after a breakthrough project at Sundance or SxSW, signs on to make a franchise picture.

As a generous and enthusiastic cinephile, Scorsese has long subscribed to a version of auteurism. Perhaps one source of his misgivings about Marvel and its counterparts is that he can’t detect auteurs in these movies. Does that mean they aren’t there? Is today’s studio cinema largely a genre cinema, minus the classic bonus of high-end auteur expression?

One of his comments has attracted little notice. Scorsese remarks of the theme-park picture:

The technique is very well done but there is only one Spielberg, there is only one Lucas, James Cameron. It’s a different thing now.

This implies that even the franchise genres could sustain some degree of what Sarris called “directorial personality.” Admirers of Taika Waititi’s Thor: Ragnarock, James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy, Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther, or Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman might agree. This has been one line of defense in the pushback to Scorsese’s comments.

Or maybe we should attribute whiffs of personal expression today to the producers (Bruckheimer, Kathleen Kennedy, Kevin Feige). Even in Hollywood’s heyday, we sense Gone with the Wind and Duel in the Sun as Selznick productions. Then there’s Walt Disney, surely a producer as auteur. I suspect that Scorsese finds these old films more inspiring than today’s behemoths.

Closing the drawbridge on Fort Multiplex

Avengers: Endgame (2019).

A genre can rise and fall in popularity. As the Western and the musical declined in the 1970s, horror and science-fiction gained traction as both programmers and A-list blockbusters. Add in the rise of fantasy, crystallized in the prestige accorded the Lord of the Rings installments. Oddly, as comic book sales declined, comic-book movies came to be a central contemporary genre. The superhero film proved a powerful blend of all these trends.

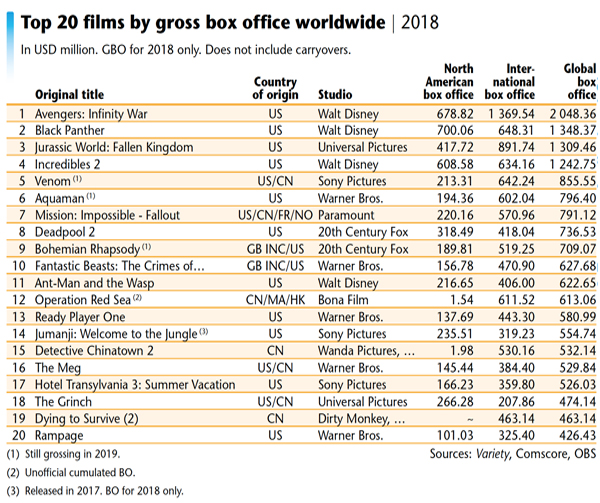

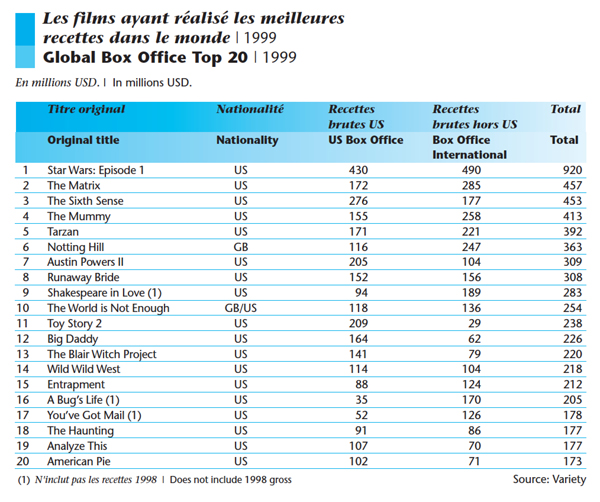

Today, the stifling presence of the fantasy/SF/comic-book franchises seems obvious. Look at two snapshots.

In 1999, the world’s top-grossing film was Star Wars: Episode 1. Among the twenty top hits were fantasy/SF blockbusters The Matrix and The Mummy, as well as a Bond entry. But there were also lower-budget horror films (The Sixth Sense, The Blair Witch Project). Most surprisingly, the top twenty include many comedies, mostly star-driven.

Now consider the 2018 situation.

Five of the global top ten were superhero films. The big winner was Avengers: Infinity War, which earned over two billion dollars globally–nearly twice as much as second-place Black Panther. Among the top ten are Venom, Aquaman, and Deadpool 2. Add The Incredibles as a sixth superhero film if you want. At 11 is Ant-Man and the Wasp. Most of the remaining titles are also franchise entries. There’s also the fantasy/SF blend Ready Player One, the monster movie Rampage, and the action thriller The Meg. Only China is offering live-action comedy (Detective Chinatown 2) and drama (Dying to Survive).

Of course nobody knows better than Scorsese that the big-budget fantasy/SF film has long been with us. His New York, New York (1977) came out the same year as Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, while 1980 saw the release of both Raging Bull and The Empire Strikes Back. But in those years straight-up genre films had a fighting chance. Smokey and the Bandit, The Goodbye Girl, 9 to 5, Airplane!, and others won big box-office.

Scorsese films have landed in the top twenty occasionally (e.g., The Color of Money and The Wolf of Wall Street). On the whole, though, I’m not suggesting that Scorsese now sees himself as competing with the biggest grossers. He’s surely right that today’s superhero films dominate the landscape. But do they squeeze out other films to the degree he suggests?

In some venues, probably yes. Small towns with one or two multiplexes may not have space for the minor-key movie. But bigger towns and midsize cities can be quite hospitable to them. In one week, alongside the big releases, multiplexes in my town of Madison, Wisconsin (pop. about 250,000) played Motherless Brooklyn, Jojo Rabbit, Parasite, The Lighthouse, The Current War, Brittany Runs a Marathon, and documentaries on Molly Ivins and Miles Davis. At least some of these qualify as original vehicles. At its widest release, The Lighthouse played on nearly 1000 US screens, and Jojo Rabbit arrived at over 800.

These are merely data points, not systematic samplings. And you might argue that we’re in the middle of Oscar qualifying season, so more offbeat films are numerous now. Okay, go back to July, the most competitive month for domestic releases. Nationally, the big pictures didn’t prevent the release of Yesterday, Midsommar, Late Night, The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Booksmart, The Dead Don’t Die, The Biggest Little Farm, The Farewell, The Art of Self-Defense, Amazing Grace, and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood.

Again, not all of these count as auteur vehicles, and several failed domestically, but they still squeezed into multiplexes. The Tarantino film obviously commanded a wide release, but many of the titles I mentioned played on between 1000 and 2000 screens. Booksmart opened on over 2500, Midsommar on 2700.

The industry doesn’t depend on the smaller or more personal titles, but then it seldom has. The biggest box-office successes in the heyday of the studio system were almost never auteur classics. Variety reported that the top domestic hits of 1943 were For Whom the Bell Tolls, Song of Bernadette, This Is the Army, Stage Door Canteen, Random Harvest, Hitler’s Children, Casablanca, Madame Curie, Star Spangled Rhythm, and Coney Island. True, Frank Borzage struck gold with Stage Door Canteen, but it’s not typical of his work. Lubitsch (Heaven Can Wait) and Hitchcock ( Shadow of a Doubt) were far down the list, bested by the likes of Sam Wood, Clarence Brown, and Henry King.

Or take 1952, ruled by The Greatest Show on Earth (De Mille), Quo Vadis, Ivanhoe, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Sailor Beware, The African Queen (Huston), Jumping Jacks, High Noon (Zinneman), and Singin’ in the Rain (Donen/Kelly). True, The Quiet Man hit number 12, and Mann’s Bend in the River number 13. But of the top hundred the only other auteur pictures seem to be Pat and Mike (no. 39), Monkey Business (no, 47), Carrie (no. 54), The Lusty Men (no. 76), and Five Fingers (no. 85).

It seems plausible, then, that in Hollywood “audiovisual entertainment” has overwhelmingly dominated the market for decades. Auteurs seldom win the biggest grosses. But again Scorsese’s career history may have influenced his judgment.

There was a moment, the Holy 1970s, when genre cinema with a personal-vision inflection was occasionally lucrative. The Godfather, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, American Graffiti, Blazing Saddles, Alien, Apocalypse Now, The Shining, and other notably original productions did earn money and awards. Yet in retrospect that seems an interregnum. The top rentals of the following decade, the 1980s, were dominated by Spielberg and Zemeckis. Then there were the usual array of star-driven comedies and action pictures. Genres came back strong, and auteurs had to work within them, or around the edges.

Such is pretty much the case right now. At the top end, perhaps the superhero films are roughly equivalent to the biblical sagas, historical pageants, and theatrical adaptations that roadshowed throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Now as then, a number of auteur films are still getting theatrical releases. The blockbusters keep the lights on and the popcorn moving so that theatres can afford to wedge straight-up genre pictures and offbeat indies into their week. It seems that you can’t run Avengers: Endgame on all 22 screens.

Art vs. craft?

Anthony and Joe Russo directing Avengers: Endgame.

But maybe we shouldn’t think of the big pictures as “audiovisual entertainment.” What’s opposed to that? “Cinema,” Scorsese said. I’d propose that this formulation means “artistic cinema.” Which is to say that we’re in the realm of the classic distinction between art and entertainment.

This has given an opening to the people riled up by Scorsese’s remarks. Admirers of Marvel, DC, and comparable pictures can say that they find them as emotional, revelatory, inspiring, etc. as anything he finds in Bergman or Sam Fuller. They feel it in their bones. And who’s to gainsay that? Scorsese doesn’t have their bones, and neither do you or I.

On more objective grounds, I suggest that Scorsese has floated another distinction. Forget calling some things “cinema” and some things not. I think that he’s distinguishing craft from art.

Let’s say provisionally that craft is the skillful manipulation of the medium to produce the desired effects. Art, on this understanding, can be considered something more. It’s usually grounded in craft, but not always. It’s also formally and emotionally complex, original in its relation to what came before, and offering new experiences on repeated exposure (rather than replays of the original response). Many, like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, would add that art induces reflection on ourselves and the world, making us wiser and deepening our humanity.

From this angle, Scorsese’s recognition of the “talent and artistry” of franchise films can be seen as a nod to craft competence. “The technique,” he says, “is very well done.” Our blockbusters are comparable to many of those anonymous hits of the studio era, turned out by skillful but impersonal artisans.

In response, the MCU advocates would need to show that the films go beyond craft. For example, some advocates find in these films the kind of character complexity Scorsese attributes to Hitchcock. He finds that Roger Thornhill in North by Northwest suffers “painful emotions” and an “absolute lostness.” Marvel fans will say something like this about moments in the stories of Tony Stark, Captain Marvel, Captain America, and the Winter Soldier.

Scorsese might reply that these are not complex characters. Yet for many years people said the same about the work of Hitchcock and other Hollywood auteurs. When people started to study them, we saw things differently. Only closer analysis of the comic-book films can give us better grounds to argue about whether their characters exhibit the “contradictory and sometimes paradoxical natures” Scorsese champions.

Realism and its rivals

Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014); Raging Bull (1980).

A few scattered speculations and I’m done.

I don’t know that we’ve fully recognized that these SF and fantasy franchises descend from earlier forms. Silent crime serials and installment films featuring Dr. Gar el-Hama and Judex had the same reliance on secret identities and world-threatening master villains. Chinese wuxia films gave their knight-errants the power to soar into the air (the “weightless leap”) and emit blasts of energy (“palm power”). The bullet ballets of Hong Kong films have obviously influenced Hollywood action pictures, but we haven’t acknowledged how our comic-book movies incorporate fantasy martial arts techniques. Hollywood owes Asian action cinema more than we usually admit.

But the silent policiers and the fantasy wuxia are flagrantly unrealistic. And Scorsese, more than many of his colleagues, is committed to realism. He couldn’t, I think, make Big Trouble in Little China or Kill Bill. I’d suggest he’s intrinsically out of sympathy with quasi-supernatural action. (Hugo is a historical film, and it’s about a sacred era of Cinema past.) Superhero dramaturgy, I hazard, rubs him the wrong way, and not just because it lacks psychological depth.

I’ve argued elsewhere on this blog that Scorsese makes forays into expressionist and impressionist technique, but they usually issue from a base of harsh realism. His commitment to realism may make it hard for him to engage with the more outrageous narrative conventions of the superhero film.

Here another classic dichotomy suggests itself. If you have to choose between basing your story on plot or character, Scorsese will choose character. In fantasy films, though, character motive and reaction are based on elaborate plot machinations. These films depend a lot on elaborate fake identities, as well as recognitions of hidden kinship. She’s my sister! He’s my father! Such devices serve to provide intricate genealogies and networks of relationships for fan homework.

Likewise, theatrical melodrama and adventure fiction from the nineteenth century supply superhero sagas with orphans of mysterious parentage, duels, hairbreadth escapes, family secrets, coded documents, precious but mysterious objects, and other franchise conventions. These are woven into complex schemes and counter-schemes of the sort found in the silent crime serials. But all these features run counter to the psychological conflicts that animate Scorsese’s plots.

Recognitions of kinship rely in turn on a plot strategy that’s worth discussing a little more; I suspect it yields much of the emotional resonance that fans enjoy. These films rely on courtship and romantic rivalries throughout, of course, as well as friendships forged and broken. These are standard for most American genres. But I’ve been surprised at how often family relations are developed in complicated ways.

It’s not just Star Wars. The Marvel Universe relies heavily on kinship to sustain its plots, as well as its pathos. Tony Stark and Pepper Potts have a daughter, as does Scott Lang. Hawkeye has a family, as does T’Challa, whose cousin N’Jadaka becomes a prime adversary. Nebula and Gamora are pressured to be dutiful daughters to Thanos. Thor and Loki share a mother, Frigga. You can argue that Tony Stark becomes a father-figure for Peter Parker. Other characters are more isolated, but for some of them, notably Natasha and Bucky, the Avengers team constitutes a surrogate family.

Marvel’s focus on the family asks us to exercise the skills we must bring to classic mythology, nineteenth-century novels, and TV soap operas. We need to keep track of who’s related to whom, and what in their past encounters can arouse obligations and conflicts. I don’t think that plots resting on such dense kinship relations are of great appeal to Scorsese; his families, when they’re present at all, are pretty small-scale (Raging Bull, Cape Fear, Shutter Island, The Age of Innocence).

Most of all, when Scorsese speaks of these films shying away from risk, I suspect he’d include their avoidance of narrative risk. In fantasy and SF, nobody need really die. Hero, villain, love interest, and sidekick can return in a parallel world, or they can be resuscitated through a new gadget. The worst outcome need not be the worst, as when Avengers: Endgame uses nanotech and time travel to rewrite the past. Plot mechanics again. Despite all the assurances that Tony Stark is really, really gone, we could find a way to bring him back if Downey wanted to sign on again. (Black Widow is being resurrected for a prequel adventure.) But there’s no bringing back Sport from Taxi Driver or Rodrigues from Silence—except in a prequel, another convention that Scorsese would likely disdain.

I’m just spitballing here, but for Scorsese and other stylized realists like Michael Mann, the comic-book convention of eternal return might seem merely juvenile wish fulfillment. Something really has to be at stake, and ultimates must be faced’ Danger and death are real. This is grown-up drama.

I’m not intrinsically opposed to the conventions ruling comic-book movies myself. In general, I think that plot is as underrated as character is overrated. (I’d rather give up the distinction altogether, but that’s another story.) Superhero films are mostly not to my taste, but I think they’re worth studying as intriguing contributions to trends in modern cinema. My point is just that the personal aesthetic of Scorsese, as both cinephile and cineaste, doesn’t fit very well with the elaborate, ever-changing rules of the magical MCU. He finds enough magic in a sinuous tracking shot, or a carefully synced doo-wop song, or an unexpected angle, or a wiseguy shouting match. That is Cinema.

There are other questions we might ask about Scorsese’s remarks. For instance, when he celebrates the thrill of communal moviegoing as a central feature of Cinema, he seems to ignore the fact that the franchise pictures are our prime multiplex attractions. Many viewers slot the more “personal films” into a future Netflix queue, but they commit themselves to seeing the big films on the big screen. That choice can yield contemporary viewers some of the electricity that Scorsese found at a screening of Rear Window. And when they’re not checking their text messages or chatting loudly with their pals, they might even give themselves up to laughs, screams, and applause, just as in the old days.

Since I wrote this, though, something much more draconian than superhero pictures may threaten non-franchise pictures. On Monday, Assistant Attorney General Makan Delrahim said that the Department of Justice is moving to end the consent decrees that have governed Hollywood studio conduct since 1948. (See here and here.)

The implications of this are staggering. We may see the return of block and blind booking, the prospect that a studio could own a theatre chain (and give favored place to its own pictures), and the decline of independent producers and art houses that favor smaller films. Nonsensically, Delrahim quoted an earlier Scorsese remark about his craft: “Cinema is a matter of what’s in the frame and what’s out.” Delrahim went on: “Antitrust enforcers, however, were not cast to decide in perpetuity what’s in and what’s out with respect to innovation in an industry.” Thus the ideology of predatory “disrupters” goes on, and even auteurs are unwillingly recruited to the enterprise.

Thanks to Jim Danky for calling my attention to the McFadden comic, and to Jeff Smith for discussions of Scorsese’s arguments. Thanks as well to Colin Burnett for discussion of the Bond saga.

My lists of top-twenty films come from the European Audiovisual Observatory’s publications Focus 1999 and Focus 2019.

I’ve left aside other writers’ analyses of Scorsese’s views. I benefited from reading Ben Child and Helen O’Hara in The Guardian, Christopher Orr’s older review in The Atlantic, and Zachary Zahos at Playback. Also pretty forceful is Kevin Feige’s defense of the MCU, which I discovered only after writing this entry. He argues for Marvel films’ value on several grounds, including their display of positive social values. And just before I posted this, the Russo brothers weighed in.

Here are other Scorsese comments made before the New York Times piece appeared. After his BAFTA David Lean lecture on 12 October, he reiterated his view.

Theatres have become amusement parks. That is all fine and good but don’t invade everything else in that sense. That is fine and good for those who enjoy that type of film and, by the way, knowing what goes into them now, I admire what they do. It’s not my kind of thing, it simply is not. It’s creating another kind of audience that thinks cinema is that. If you have a child and the child wants to see the picture, what are you going to do? It’s up to you. The audience that sees them now, the fans that see those pictures now, they were raised on pictures like that.

The technique is very well done, but there is only one Spielberg, only one Lucas, James Cameron, it’s a different thing now. It’s an invasion, so to speak, in the theatre. . . .

We are in a moment not only of evolution but of revolution, in pretty much the whole world, everything we know, the old political systems, it’s almost as if the 21st century is beginning now and technology has gone with it and that means cinema goes with it.

Yes, see a movie in a theatre, it’s the best with an audience, but the actual concept of cinema has become something that is not definable. Something can play as a hologram, something can play as virtual reality, maybe there is going to be an extraordinary epic in virtual reality at some point. We have to start expanding what we think of as narrative, music, literature, art and particularly the visual image.

Granted, this whole passage is a bit baffling. It’s not completely clarified in a press conference the next day at the BFI London Film Festival. The relevant section starts at 16:26.

It’s also interesting that Benedict Cumberbatch (aka Dr. Strange) defends the need for auteurs.

Some comments on Sarris’s career and the vagaries of auteur theory are here. I discuss Black Panther and its debt to classical Hollywood storytelling here.

Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas (2007).

Cornell Woolrich: The overstrained imagination goes to the movies

DB here:

Can a storyteller be maladroit in using his or her medium and still be worth reading? Can a novelist with a clumsy style be a “good writer”? I’ve posed this question before on this site, and developed an argument about it at length in our book on Christopher Nolan.

Here’s a test case. These are real sentences from books by a novelist many consider one of the great crime/mystery writers of all time.

The knob felt cold and glibly elusive under his touch.

His face was an unbaked cruller of rage.

La Bruja lidded her eyes acquiescently.

I began treacherously touching up my hair via the mirror.

I crawled up onto the seat by means of my hands.

She could feel her chest beginning to constrict with infuriation.

This time the man got up off the bench, taking Quinn’s hand on his shoulder along with him.

Smoke suddenly speared from her nostrils in two malevolent columns. She looked like Satan. She looked like someone it was good to stay away from.

I was probably just a blurred bottle-green offside to her retinas.

“Made it,” Joan Bristol exhaled relievedly.

Seconds went by in packages of sixty.

The foaming laces that cascaded down her were transparent as haze against the light bearing directly on her from the room at her back. Her silhouette was that of a biped.

These passages, and many more like them, were published in books issued by major houses and still in print today. Can anything redeem them?

I’m currently trying to write a book on principles of popular narrative, with a focus on genres of crime and mystery. The project stems from arguments in Reinventing Hollywood and The Way Hollywood Tells It, but I wanted to broaden my inquiry to include theatre and literature as well. One section is about crime writers of the 1940s and 1950s. So naturally I had to include the widely renowned Cornell Woolrich.

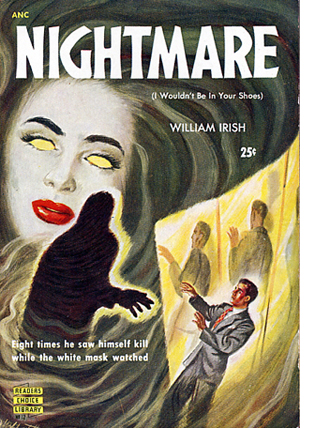

Despite his struggles with syntax and word choice, Woolrich has been a perennial source of popular storytelling. Nearly all the novels were brought to the screen soon after publication, and radio versions of the books and short stories were plentiful. By the 2010s his work had inspired over a hundred movies and television shows (directed by, among others, Hitchcock, Truffaut, Fassbinder, and Jacques Tourneur).

That research has led me two further questions. Are there aspects of his work that counterbalance howlers like those above? And what might have led to those stylistic problems? Readers looking for more direct and detailed studies of film versions of his work can go to Francis M. Nevins’ exhaustive biography and Thomas C. Renzi’s careful consideration of adaptations. (And my studies of The Chase, if you want.) Meanwhile, tackling the questions that interest me, I’ll touch on aspects of cinema a little bit. File this blog under Questions of Narrative Across Media.

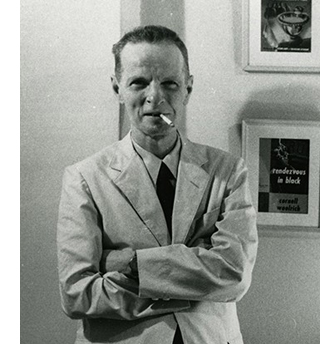

Breathless reading

Cornell Woolrich is usually treated as an author with a uniquely haunting voice. Alcoholic and homosexual, he lived for decades in a hotel with his mother. After she died, he lost a leg to untreated gangrene. He dedicated one book to the typewriter on which he pounded out pulp stories and thriller novels, the most famous of them published in the years 1940-1948. His tales of suspense cultivated a hothouse morbidity. At his limit, Woolrich projects a paranoid vision of life without hope and death without dignity.

Cornell Woolrich is usually treated as an author with a uniquely haunting voice. Alcoholic and homosexual, he lived for decades in a hotel with his mother. After she died, he lost a leg to untreated gangrene. He dedicated one book to the typewriter on which he pounded out pulp stories and thriller novels, the most famous of them published in the years 1940-1948. His tales of suspense cultivated a hothouse morbidity. At his limit, Woolrich projects a paranoid vision of life without hope and death without dignity.

Despite his distinctive sensibility, Woolrich epitomizes some broader narrative strategies of his time. Like all popular writers, he inherited situations, techniques, and themes. To present a bleak, aching world of precarious love and doomed lives, he twisted those conventions into eccentric shapes that added to the Variorum of 1940s mystery storytelling.

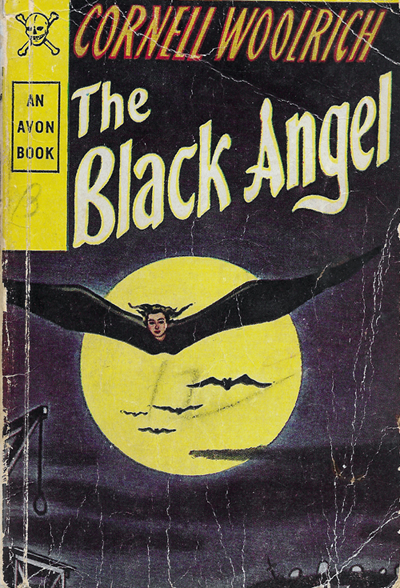

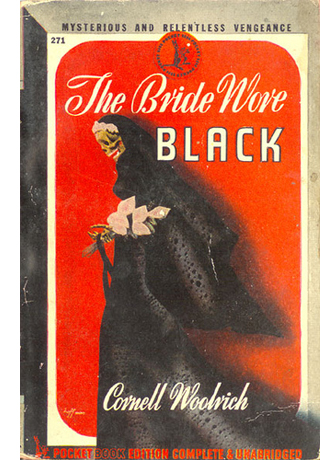

For him, one bout of amnesia isn’t enough, so The Black Curtain (1941) doubles it: the hero, already having forgotten his previous identity, is clobbered by some falling bricks and now can’t remember who he just was. The prototypical serial killer of the 1940s is a man, but The Bride Wore Black (1940) lets a woman stalk her victims. Most thriller novelists are content to put one woman in jeopardy per book, but Black Alibi (1942) lines up six. Alternatively, when a woman tries to save her husband from the chair by investigating four suspects, she’s plunged into danger every time she meets one (The Black Angel, 1943).

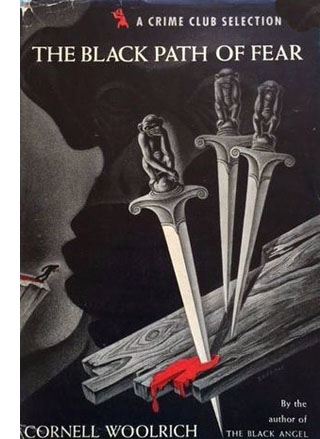

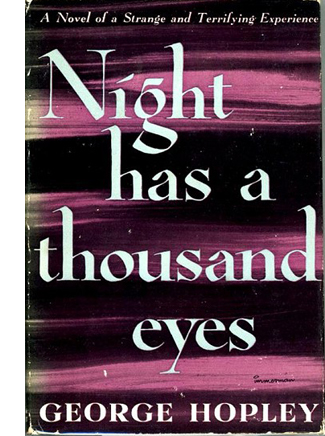

Woolrich’s plots flout police procedure (his cops are exceptionally willing to help suspects), and the authorities often flounder. Suspense thrillers usually invoke the supernatural only to dispel it, but in Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1945) the authorities fail to save a life because one old man really can predict the future. Not that amateur sleuths fare much better. The unheroic hero of The Black Path of Fear (1945) could hardly be more ineffective; he has to be rescued by the Havana police.

Sometimes the straining for originality snaps. Critics have long pointed out improbabilities and contradictions in the plots. Woolrich’s most devoted chronicler, Francis M. Nevins, warns of “chaotic ambiguities.” The chronology of Rendezvous in Black (1948) is impossible, while the climactic revelation of I Married a Dead Man (1948) is arguably incoherent. Convenient coincidences abound. Add to this a hypertrophied style that in every book slips into unabashed weirdness. (See above.)

Both the plot problems and the vagaries of language can partly be attributed to the rush of Woolrich’s production, his transport while hammering at his Remington Portable. Pulp author Steve Fisher recalled: “Sitting in that hotel room he wrote at night—continuing through until morning, or whenever the story was finally completed. He did not revise, polish, and I suspect did not even read the story over once it was committed to paper.” Although Woolrich was grateful to editors who corrected his hundreds of errors in spelling and punctuation, he apparently resisted efforts to touch up his prose. When an editor suggested a change to a single paragraph, he replied, “I knew you wouldn’t like it,” and left the publisher forever.

Both the plot problems and the vagaries of language can partly be attributed to the rush of Woolrich’s production, his transport while hammering at his Remington Portable. Pulp author Steve Fisher recalled: “Sitting in that hotel room he wrote at night—continuing through until morning, or whenever the story was finally completed. He did not revise, polish, and I suspect did not even read the story over once it was committed to paper.” Although Woolrich was grateful to editors who corrected his hundreds of errors in spelling and punctuation, he apparently resisted efforts to touch up his prose. When an editor suggested a change to a single paragraph, he replied, “I knew you wouldn’t like it,” and left the publisher forever.

Admiring readers excuse the faults by testifying that Woolrich’s evocation of tension keeps the pages turning. “Headlong suspense created by total, unrelieved anxiety,” noted Jacques Barzun. “Breathless reading is the sole pleasure.” Raymond Chandler called him the “best idea man” among his peers, but admitted, “You have to read him fast and not analyze too much; he’s too feverish.”

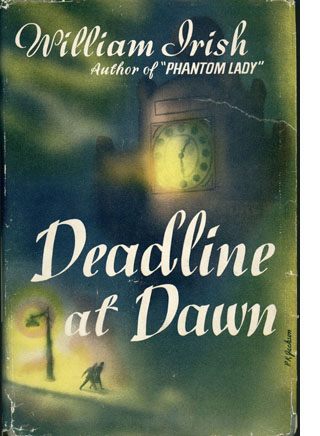

What keeps us reading? For one thing, the outré story situations. A couple hurrying to leave New York must clear the man of murder before the bus leaves (Deadline at Dawn, 1945). A killer stalks a city, but it’s not a human: it’s (apparently) a black jaguar escaped from a sideshow (Black Alibi). A mail-order bride seems unacquainted with things she wrote in her letters (Waltz into Darkness, 1947). Most famously, a man laid up in his apartment thinks he sees traces of a killing through a window across the courtyard (“Rear Window,” 1942).

Outrages to plausibility carry their own allure. What, we ask, might come of these wild mishaps? A train crash kills a husband and his pregnant wife. In the melée an abandoned woman, also pregnant, is mistaken for her and welcomed by the husband’s family. Conveniently, the in-laws have never seen the wife (I Married a Dead Man, 1948) A man accused of murder has an alibi, to be provided by a woman he met in a bar and took to a show. Trouble is, she’s vanished. All the witnesses deny she existed (Phantom Lady, 1942).

The development of the action also presents intriguing reversals. The man gulled by the fake mail-order bride falls in love with her. People who claim not to have seen the phantom lady wind up dead. The woman trying to exonerate her husband falls in love with the real killer and dreams about him even after he has killed himself.

The game is afoot

Woolrich’s novels tend to rely on two basic plot patterns, both based on the hunt. In one, amateurs try to solve a crime and move from suspect to suspect. Our viewpoint is mostly tied to the investigators. In the other pattern, a serial killer stalks a string of victims, and here Woolrich is more innovative. Normally, the serial-killer plot either concentrates on the killer’s viewpoint, as in the novels Hangover Square (1941) and In a Lonely Place (1947), or concentrates on the investigators, as in Ellery Queen’s Cat of Many Tails (1949). A few constantly bounce the spotlight among all the parties—killer, victims, and investigators—as in Fritz Lang’s film M (1931) and Philip MacDonald’s novel X v. Rex (1933).

Woolrich by contrast emphasizes the victims’ viewpoints. The killer might appear only at the beginning and end (Rendezvous in Black) or get introduced at intervals in brief, objective scenes (The Bride Wore Black). Less space is devoted to the investigators, although they gain prominence as the crimes pile up. Woolrich puts his energies into building waves of suspense as one target after the other confronts death.

The shooting-gallery structure enables Woolrich to fulfill Mitchell Wilson’s demand that the thriller devotes its energies to showing what fear feels like. The 1940s interest in intense subjectivity of narration helps out here, and Woolrich sustains it in detailed description of victims’ reactions. In Black Alibi, Teresa is being stalked by an unseen figure.

The shooting-gallery structure enables Woolrich to fulfill Mitchell Wilson’s demand that the thriller devotes its energies to showing what fear feels like. The 1940s interest in intense subjectivity of narration helps out here, and Woolrich sustains it in detailed description of victims’ reactions. In Black Alibi, Teresa is being stalked by an unseen figure.

Something else now assailed her, again from without herself, but of a different sensory plane than hearing this time. A prickly sensation of being watched steadily from behind, of something coming stealthily but continuously after her, spread slowly like a contraction of the pores, first over the back of her neck, then up and down the entire length of her spine. She couldn’t shake it off, quell it. She knew eyes were upon her, something was treading with measured intent in her wake.

This passage is part of a ten-page account of the woman’s wary progress through a night street, rendered wholly from her viewpoint.

Woolrich’s other basic plot pattern, the investigation of a murder, plays up the role of fear as well. His amateur detectives, lacking official firepower, are constantly facing danger from the suspects they track.

Fright was like an icy gush of water flooding over them, as from burst pipe or water-main; like a numbing tide rapidly welling up over them from below. [Deadline at Dawn]

In both of his favored plot schemes, the plunges into characters’ minds and bodies help fill out a full-length novel. If you play down other lines of action (professional police investigation, killer’s mental life), you need to dwell on the reactions of the victims or amateur detectives.

Yet this very emphasis is one source of the stylistic howlers. In expanding his suspense scenes, Woolrich’s prose sometimes fails him. Needing to spin out lots of words evoking an ominous atmosphere, he’s tempted to pileups like this:

And the path that had led me to it through the night had been so black and so full of fear, and downgrade all the way, lower and lower, until at last it had arrived at this bottomless abyss, than which there was nothing lower. [The Black Path of Fear]

Such rodomontade carries the 1940s emphasis on subjectivity to paroxysmic limits.

He recruits other techniques of popular storytelling. They keep his action moving forward through time and plunging inward into the unfolding scenes. And some can help mask story problems.

By hinging his story around a search for a killer or a victim, Woolrich’s plots tend create a string of one-on-one encounters. Rather than disguising the episodic quality of these, he sharpens them by breaking the action into distinct blocks. Those blocks are presented as a checklist agenda, Woolrich’s equivalent to the closed circle of suspects we find in the classic weekend-house-party detective story.

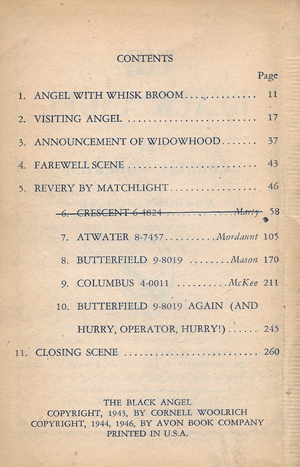

The Black Angel is a simple instance.

After an initial cluster of five chapters presenting Kirk Murray sentenced to death, we follow Kirk’s wife Alberta as she seeks the true killer. Her efforts are given in five parallel chapters, each indented and tagged with a telephone number. One that Alberta finds scratched out in an address book is presented just that way in the chapter title: “Crescent 6-4824.” Because at the climax she returns to one of the four suspects, another title gets recycled: “Butterfield 9-8019 Again (And Hurry, Operator, Hurry!).”

A more complicated example of modularity is The Bride Wore Black. It’s broken into five parts, each titled with the name of a victim. Each part contains three sections.

“The Woman” shows the vengeful bride launching a new false identity. The part’s second section, titled with the victim’s name, shows how the murder is accomplished. A third section offering “Post-Mortem” on the victim consists of documents and conversations among the police. Viewpoints are rigidly channeled as well. Each “Woman” section is handled in objective description, while each victim section presents the targeted man as the center of consciousness. The book could be mapped out on a spreadsheet.

The modular layout and rigorous moving-spotlight narration risk choppiness, yielding something like a set of short stories. But the tidy exoskeleton can make the plot seem rigorously organized, even while it masks problems of time and causality. And the very arbitrariness of the pattern creates a sort of meta-curiosity. Like the teasing tables of contents in 1920s and 1930s detective fiction, a Wooolrich checklist of suspects or victims makes us aware of a larger rhythm. How will this pattern be filled out?

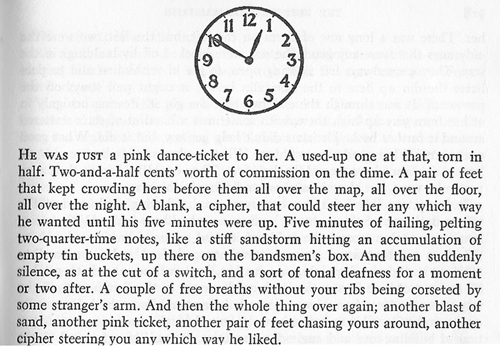

An overarching unity is provided as well by the demands of a deadline (another Hollywood-friendly feature). Thanks to this classic device, Woolrich can use time tags to trigger anticipation and yield a sense of shape. Long before the husband in Phantom Lady gets accused of the crime, the first chapter bears the title, “The Hundred and Fiftieth Day before the Execution,” effectively dooming him from the start. Deadline at Dawn replaces chapter titles with illustrated clock faces to impose a strict structure.

An overarching unity is provided as well by the demands of a deadline (another Hollywood-friendly feature). Thanks to this classic device, Woolrich can use time tags to trigger anticipation and yield a sense of shape. Long before the husband in Phantom Lady gets accused of the crime, the first chapter bears the title, “The Hundred and Fiftieth Day before the Execution,” effectively dooming him from the start. Deadline at Dawn replaces chapter titles with illustrated clock faces to impose a strict structure.

Facing a ticking clock wedded to a clear-cut pattern, we become sensitive to variations among the modules. The victim-centered chapters of The Bride contrast the personalities and private lives of the male victims, along with Julie’s resourceful methods of murder, and the last chapter breaks the three-part format by inserting a flashback dramatizing the fatal wedding. Rendezvous in Black revives the shooting-gallery structure of Black Angel and The Bride, adding a schedule that sets each murder on May 31st of different years. Within this regularity (“The First Rendezvous,” etc.), viewpoints multiply gradually so that the interplay of characters’ range of knowledge becomes richer.

The modular structure shows up in milder ways. Black Alibi tags its chapters with victims’ names and concentrates on one woman’s terror at a time, with each chapter concluding with an exchange among investigators. Deadline at Dawn and Phantom Lady alternate scenes between two characters embarked on parallel investigations. Night Has a Thousand Eyes, in some ways the most ambitious of the books, embeds the checklist within the police investigation. As teams of cops trace parallel leads, their efforts are crosscut with the target under threat, waiting with his daughter and a cop.

A simpler, more poignant, rhyme-and-variations effect is supplied by a prologue and epilogue in I Married a Dead Man. The prologue’s first-person narration, set off from the central chapters’ third-person narration, finishes: “We’ve lost. That’s all I know. We’ve lost, we’ve lost.” An epilogue rewrites the prologue and yields closure: “We’ve lost. That’s all I know. And now the game is through.” In such ways, Woolrich brings the overt compositional symmetry of both “serious literature” and the puzzle-driven detective story into the thriller.

Sweating the small stuff

Henry James, 1913; Cornell Woolrich, ca. 1927.

By the 1920s, ambitious Anglo-American writers in both popular genres and “advanced” literature had fallen under the sway of a new model of the novel. Henry James had argued that if the novel was to be a true art form, it needed more compositional rigor, a patterned architectural solidity. He also advocated for a self-conscious control of viewpoint and a greater commitment to concrete presentation of action. (“Dramatize, dramatize!”) A little later, Joseph Conrad’s books had demonstrated the power of shifting viewpoints and multiple narrators, as well as an emphasis on the power of sight.

Popular writers of the nineteenth century, notably Dickens and Wilkie Collins, had already made use of some of these techniques, as did more highbrow efforts, like Robert Browning’s verse novel The Ring and the Book (1868-1869). But in the wake of James and Conrad, tastemakers erected these principles into strict norms for well-made novels. These precepts were set out explicitly in Percy Lubbock’s The Craft of Fiction (1922), and they were picked up in popular writing manuals as well.

Many mainstream fiction writers (and dramatists) took up the techniques promoted by the James-Conrad-Lubbock tradition. Middlebrow novels employed block construction, played with multiple viewpoints, and included an explicit “exoskeleton” of labeled parts pointing up a self-conscious architecture. Joseph Hergesheimer’s Java Head (1919) spreads nine characters’ viewpoints across ten parallel chapters. Detective fiction wasn’t immune to the new methods. Conrad’s exploration of optical viewpoint has a contemporary counterpart in the Chestertonian grandeur of the mystery story “The Hammer of God” (1910). Father Brown is standing at the top of a church.

Immediately beneath and about them the lines of the Gothic building lunged outwards into the void with a sickening swiftness akin to suicide. . . . When they saw [the church] from below, it sprang like a fountain at the stars; and when they saw it, as now, from above, it poured like a cataract into a voiceless pit.

The writers of High Modernism revised the James-Conrad-Lubbock norms, pushing toward more difficult manipulations of time, viewpoint, and subjective states. Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury assigns different narrational voices to its four-block layout, but these make the story world and the time scheme opaque. (Even if you master the stream-of-consciousness technique, you still have to figure out that one character is called by two names and two characters have the same name.)

Like many other writers, Woolrich pulls several post-James techniques into genre literature. His block construction, marked by strict times and viewpoints, along with his labeling of plot phases, owes something to this tradition, as well as to the clever construction of detective stories of the 1920s and 1930s (Ellery Queen, Anthony Berkeley, et al.). He borrows another narrative strategy as well: granular scene description keyed to a character’s sensations and feelings. We get a kind of hypertrophy of Lubbock’s “Show, don’t tell.” In reply to James, Woolrich in effect declares, “Overdramatize, overdramatize!”

In his uncompleted autobiography, Woolrich reflected on his early efforts to compose scenes. A man takes a hotel elevator, and instead of writing, “He got in, the car started; the car stopped at the third and he got out again,” the young Woolrich would pad the trip out to a page or more. This was amateurish, he thought at the end of his life. Yet this sort of expansion of action moment by moment is a hallmark of his 1940s novels. Perhaps it’s what Chandler had in mind when referred to Woolrich “getting deep into every scene.”

As we’ve seen, moments of terror and suspense are rendered in detail. So are the necessary touches of atmosphere. In The Black Path of Fear, the man on the run has told his story to Midnight.

As we’ve seen, moments of terror and suspense are rendered in detail. So are the necessary touches of atmosphere. In The Black Path of Fear, the man on the run has told his story to Midnight.

When I’d finished telling it to her the candle flame had wormed its way down inside the neck of the beer bottle, was feeding cannibalistically on its own drippings that had clogged the bottle neck. The bottle glass, rimming it now, gave a funny blue-green light, made the whole room seem like an undersea grotto.

We’d hardly changed position. I was still on the edge of her dead love’s cot, inertly clasped hands down low between my legs. She was sitting on the edge of the wooden chest now, legs dangling free. . . .

The behavior of light, the insistence on color, the description of the characters’ postures and gestures—these are typical of Woolrich’s scenes.

Even the simplest action employs Lubbock’s “scenic method” to a disconcerting degree. To quote adequately would take pages, but some samples can suggest just how distended and detailed even minimally functional scenes are.

I reached out for a little lamp he had there close beside the bed and clicked it on. Twin halos of light sprang out, one at each end of the shade, and showed up our faces and a little of the margin around them. The shade itself was opaque, to rest the eyes.

Then I just sat back and waited for the shine to percolate through to him, sitting on the bias to him. It took some time. He was sleeping like a log. [The Black Path of Fear]

Any other writer would have retained just the first sentence and the last (but maybe not with the clichéd phrasing). Who cares about the design of a light fixture, or whether the shade rests the eyes? Yet Woolrich feels the need to show and tell as much as he has room for.

A woman comes to a Bowery bar looking for a murder suspect. After a page and a half of banter with the bartender, she finds her quarry hunched over a tabletop. Another page is devoted to rousing him.

He moved slightly, and I saw him looking downward at the floor around his feet. Looking around for something on that filthy place where people stepped and spat all day long. In a moment more I had guessed what he was looking for and I opened my handbag and took out the cigarettes I had provided myself with and held the package ready, with one protruding, as my first silent overture.

His eyes stopped roaming suddenly, and they had found the small arched shape of my shoe, planted there unexpectedly on that floor beside him, and the tan silk ankle rising from it. [The Black Angel]

It takes another page for the drunk to accept the cigarette, and three more for the woman to question him. But he’s too incoherent, so she parks him in a hotel and resumes questioning him the next day—a process that takes fifteen pages and includes detailed descriptions of the hotel room, the light filtering in, and the two characters’ shifting positions in space.

This writer has Roderick Usher’s “morbid acuteness of the senses.” Scenes are thick with smells and sounds. One virtuoso section of Rendezvous in Black is all noises and speech because our center of consciousness is a blind woman. Above all, Woolrich’s scenes revel in optical point of view.

Movies on the page

Sometimes the observer is imaginary, looking at things alongside the character. Detective Wanger enters a murder scene.

They seemed to be playing craps there in the room, the way they were all down on their haunches hovering over something in the middle of the floor. You couldn’t see what it was, their broad backs blotted it out completely. It was awfully small, whatever it was. Occasionally one of their hands went up and scratched the back of its owner’s rubber-tired neck in perplexity. The illusion was perfect. All that was missing was the click of bone, the lingo of the dicegame. [The Bride Wore Black]

Actually, the policemen are interrogating a boy whose father has been murdered. Presumably Wanger doesn’t take the huddle for a craps game. We’re given the mistaken impression of a novice observer who’s watching from a particular angle.

More often, it’s the character who occupies a definite station point, determined by foreshortening and perspectival distortion. The supreme example is of course the short story “Rear Window” (1942) whose original title was “Murder from a Fixed Viewpoint.” One of his clumsy passages in another story tries for the same kind of positioning: “He turned and looked up, startled, ready to jump until he’d located the segment of her face far up the canal of opening between them.”

Woolrich’s interest in the geometry of looking, what can and can’t be seen, finds a natural home in eyewitness plots, of which there were several in 1940s film and fiction (and even radio). In “Rear Window,” the protagonist Jeff tracks his neighbor’s progress from window to window as if studying an Advent calendar. Woolrich strives to capture the exact geometry of Jeff’s field of view.

Woolrich’s interest in the geometry of looking, what can and can’t be seen, finds a natural home in eyewitness plots, of which there were several in 1940s film and fiction (and even radio). In “Rear Window,” the protagonist Jeff tracks his neighbor’s progress from window to window as if studying an Advent calendar. Woolrich strives to capture the exact geometry of Jeff’s field of view.

There was some sort of a widespread black V railing him off from the window. Whatever it was, there was just a sliver of it showing above the upward inclination to which the window sill deflected my line of vision. All it did was strike off the bottom of his undershirt, to the extent of a sixteenth of an inch maybe. But I hadn’t seen it there at other times, and I couldn’t tell what it was.

Jeff’s tightly focused attention contrasts with his neighbor Thorwald’s casual sweeping looks toward the courtyard. The climax will come when Thorwald realizes he’s been Jeff’s target, and Jeff sees in the murderer’s look “a bright spark of fixity” that “hit dead-center at my bay window.”

A similar effect occurs at the climax of “The Boy Cried Murder” (aka “Fire Escape”) of 1947, the source of the film The Window (1949). Buddy has been sleeping on a fire escape and is awakened by a murder he watches through a slit in the window shade. The woman comes toward him.

She started to come over to where Buddy’s eyes were staring in, and she got bigger and bigger every minute, the closer she got. Her head went way up high out of sight, and her waist blotted out the whole room. He couldn’t move, he was like paralyzed. The little gap under the shade must have been awfully skinny for her not to see it, but he knew in another minute she was going to look right out on top of him, from higher up.

Again, there’s a stylistic slip (of course she’ll be higher up if she looks out on top of him), but it’s a byproduct of an effort to capture a character’s optical viewpoint.

Sometimes that effort seems pure gimmickry.

I hurried down the street, and the intermittent sign back there behind me kept getting smaller each time it flashed on. Like this:

MIMI CLUB

Mimi Club

mimi club

I could tell because I kept looking back repeatedly, almost in synchronization with it each time it flashed on. . . . [The Black Angel]

Yet even the gimmick seems an effort toward a peculiar kind of vividness—that of a film. The passage imitates alternating shots of the woman looking and the withdrawing club sign. If Woolrich’s modular structure is indebted to strains in modernism and popular fiction, the dense, over-visualized scenes inevitably suggest cinema.

Woolrich worked as a Hollywood screenwriter for a few years and had a lifelong affinity for movies. The books often use cinematic analogies and metaphors, and the characters are frequent moviegoers. (In a 1936 story, “Double Feature,” a gangster takes a woman hostage in a projection booth.) Supposedly Woolrich spent his last years holed up drinking and watching old films on TV. No surprise, then, that some passages echo the look and feel of Hollywood scenes.

Granted, many writers, highbrow and lowbrow, were imitating cinema in Woolrich’s day. Some incorporated filmlike montage sequences to suggest dreams and stream of consciousness. But Woolrich goes farther than most. In Fright (1950), two paragraphs headed “Still Life” survey an empty room that shows signs of interrupted activity—a crumpled newspaper, a note, a burning cigarette, a swaying lamp chain. The passage mimics the sort of tracking shot over details we find in 1940s cinema, continuing for a page until it climaxes in a close-up panning over a body jammed against the door.

When a man realizes his beloved woman lies dead on the bed, a dash can imitate a cut:

But her eyes were still blurry with slee—

His hand stabbed suddenly downward toward the hairbrush, there before her. [Rendezvous in Black]

In Night Has a Thousand Eyes, a woman waits in her car while her father visits the telepath over a period of weeks. Each brief scene starts with the same imagery and phrasing, creating a string of rhyming “shots” across three pages.

In Night Has a Thousand Eyes, a woman waits in her car while her father visits the telepath over a period of weeks. Each brief scene starts with the same imagery and phrasing, creating a string of rhyming “shots” across three pages.

I sat there waiting for him, cigarette in my hand, light-blue swagger coat loose over my shoulders. . . .

I sat there waiting for him, rust-colored swagger coat loose over my shoulders. . . .

I sat their waiting for him, plum swagger coat over my shoulders. . . .

I sat there waiting for him, fawn swagger coat over my shoulders. . . .

I sat there waiting for him, green swagger coat over my shoulders. . . .

I sat there waiting for him, black swagger coat over my shoulders, as I’d already sat waiting so many times before.

The modular approach ruling the books’ overall architecture gets carried down into the texture of scenes, creating parallel mini-blocks that convey the daughter’s anxious acquiescence to her father’s obsession.

Woolrich’s literary optics have strong affinities with cinema. We get an effort to mimic a subjective tracking shot as one heroine circles a garden.

The little rock-pool in the center was polka-dotted with silver disks, and the wafers coalesced and separated again as if in motion, though they weren’t, as her point of perspective continually shifted with her rotary stroll. [I Married a Dead Man]

Likewise, a woman approaching a man slowly tapers into focus.

She was up to him eye to eye before he could even take her in in any kind of decent perspective. His visualization of her had to spread outward in concentric, radiating circles for those eyes, staring into his at such close-range.

Brown eyes.

Bright brown eyes.

Tearfully bright brown eyes.

Overflowingly tearful bright brown eyes.

Suddenly a handkerchief had come up to shut them off from his for a moment, and he was able to steal a full-length snapshot of her. Not much more. [The Black Curtain]

This is just showboating, but it’s uniquely Woolrich showboating.

The same goes for a passage struggling to describe people at a bar as if they were framed in the flattening view of a telephoto shot.

There were eight people paid out along it. They broke into about three groups, each self-contained, oblivious of the others, but he had to look close to tell where the divisions came in. Physical distance had nothing to do with it; they all stretched away from him in an unbroken line. It was the turn of the shoulders that told him. The limits of each group were marked by a shoulder turned obliquely to those next in line beyond. They were like enclosing parentheses, those shoulders. In other words, the end men in each group were not postured straight forward, they turned inward toward their own clique. The groupings broke thus: first three, then a turned shoulder, then three again, then another turned shoulder, then finally two, standing vis-à-vis. [Deadline at Dawn]

Few writers would strive so hard to capture the exact look of figures in space. It will take another page for the viewpoint character to realize that a left-handed drinker has stepped out, because one beer mug isn’t empty and the handle is pointing in a different direction than the others.

It’s not hard to imagine such scenes as Hitchcockian POV shots. In Waltz into Darkness, Durand notices a colonel and his lady in the reflection of the “thick, soapy greenish” window of a café. At first the view yields a blob sporting “three detached excrescences”: a feather in a hat, a bustle, and “a small triangular wedge of skirt.” Eventually this monstrosity draws away “into perspective sufficient to separate into two persons.” Conrad’s “impressionism,” aiming to capture the limits of physical point of view, reaches a new height with Woolrich’s account of exact but imperfect vision.

Some provisional answers to my Woolrich questions run like this. The ingenuity of structure and the inherent fascination of the situations somewhat offset the problems of style. Most of his novels tap our primal interest in the hunt, and if things don’t always pay off neatly, the pursuit has enough detours, hurdles, and pitfalls to sustain interest.

And the writing isn’t totally disastrous. There are well-written passages in every Woolrich novel. Many of the howlers arise from the keyed-up emotion he tries to squeeze out of every scene. Others stem from sheer overwriting and padding, and probably the habit Fisher notes of seldom revising. But other errors are a byproduct of his effort to put every bit of action starkly before us. Straining for sensory vividness lures him into clumsiness (“triangular wedge,” as if all wedges weren’t triangular).

More generally, in both virtues and faults, he displays a dogged, frenzied obedience to the narrative traditions he inherited, and an urge to innovate within them, however eccentrically. Henry James asserted that “a psychological reason is, to my imagination, an object adorably pictorial.” A Woolrich character puts it in a typically convoluted way: “Every time you think of anything, there’s a picture comes before you of what you’re thinking about.”

Beyond the books of Nevins and Renzi, valuable appreciations of Woolrich include Nevins’ essay in his collection Cornucopia of Crime: Memories and Summations (Ramble House, 2010), 53-71; Geoffrey O’Brien’s comments in Hardboiled America: Lurid Paperbacks and the Masters of Noir, second ed. (Da Capo, 1997), 97-100; and James Naremore’s essay on his site, “An Aftertaste of Dread: Cornell Woolrich in Noir Fiction and Film.” For a topical overview of Woolrich’s output, see Mike Grost’s entry on him.

I took Steve Fisher’s account of Woolrich’s writing process from “I Had Nobody,” The Armchair Detective 3, 3 (1970), 164. The quotation from Jacques Barzun comes from Barzun and Wendell Hertig Taylor, A Catalogue of Crime, rev. ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1989), 561. The Raymond Chandler remarks appear in a 1949 letter to Alex Barris in Raymond Chandler Speaking, ed. Dorothy Gardner and Kathrine Sorley Walker (Plainview, New York: Books for Libraries, 1971), 55. I’ve discussed Mitchell Wilson’s essay, “The Suspense Story,” The Writer 60, 1 (January 1947) at greater length in the online essay “Murder Culture.” More generally, Woolrich’s narrative strategies accord with several I chart in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, including the notion of the Variorum.

Woolrich’s early, Fitzgerald-influenced novels reveal seeds of the style to come. A random page from Manhattan Love Song (1932) yields a scene of the hero talking to two women: “Instantly I saw a gleam of admiration light each of their four eyes.”

Astonishingly, Woolrich’s prose glitches don’t rate a mention in Bill Pronzini’s hilarious compilations of bad writing, Gun in Cheek: A Study of “Alternative” Crime Fiction (Coward McCann, 1982) and Son of Gun in Cheek (Mysterious Press, 1987). Pronzini tactfully limits his citations of the classics, only mentioning one Raymond Chandler line: “In spite of his weathered appearance, he looked like a drinker.” Pronzini can find no faults in my personal Style canon: Rex Stout, Donald Westlake (here and here), and Patricia Highsmith.

There’s more on these issues in the entry “The 1940s are over, and Tarantino’s still playing with blocks.” I discuss The Window in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

Cine-Vienna

The Third Man (1949).

DB here:

En route to Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, Kristin and I paid a visit to this wonderful city. We wandered around, stomped through museums, ate tasty food, and saw a bit of the city’s film culture.

Visiting venues

Our first stop was the Austrian Film Museum. Founded in 1964 by the avant-garde filmmaker Peter Kubelka, the Museum has built up a collection of over 30,000 films. It contains a fine film theatre with features of the “Invisible Cinema” (above) that Kubelka and Jonas Mekas set up in Anthology Film Archive many years ago.

The Museum has been a pioneer in producing outstanding books and DVD editions devoted to an eclectic array of filmmakers (James Benning, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Straub/Huillet, Joe Dante). Exceptional as well are the Museum’s online offerings of films, clips, images, and paper documents.

Our host was our old friend, the ebullient curator Christoph Huber. Here he is with his colleagues Alexandra Thiele and Jurij Meden.

We didn’t have a chance to visit the classic Stadtkino in the same neighborhood, nor did we check out the highly esteemed Austrian Film Archive. But I did mosey down to the Gartenbaukino, a big, beautiful modernistic venue.

Built as a ballroom that occasionally screened films, the Gartenbau was made a permanent cinema in 1919. In 1960, after being redesigned by Robert Kotas, it opened as a showcase for widescreen motion pictures.

It’s now said to be the biggest theatre in Austria, with over 700 seats. Note the rising curtain, said to be a rarity these days.

The Gartenbaukino is equipped to project not only digital and 35mm but also 70mm. Managing Director Norman Shetler notes that it was the first Austrian theatre to boast large-format projection (for Spartacus) and was adapted for Cinerama as well.

More recently, the Gartenbau reactivated its 70mm equipment to show The Hateful Eight. The Phillips DP70 projectors now screen wide-gauge classics like Lawrence of Arabia and The Sound of Music. Picture and sound were excellent for The Dead Don’t Die, so I bet 70mm shows here are fantastic. Like the Stadtkino, the Austrian Film Archive, and the Film Museum, the Gartenbau is a venue for the city’s annual film festival, the Viennale.

Prater, not so violet

Plenty of movies have been set in Vienna, most notably The Joyless Street, Merry-Go-Round, Letter from an Unknown Women, and Amadeus. But for movie nerds the most flagrant example is The Third Man (1949). And Vienna hasn’t forgotten what this movie did for its local landscape, not least the amusement park set within the vast and beautiful park known as the Prater.

Said to be the oldest amusement park in the world, the Prater ‘s entertainment sector contains attractions that are shiny and enjoyable old-school rides: roller coaster, loop-the-loop, tilt-a-whirl, haunted house. There are shooting galleries, ice-cream stands, and even a Madame Tussaud’s.

But of course the looming attraction is the great Ferris wheel that Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) and Harry Lime (Orson Welles) share during their ominous reunion. I’m sure I’m not the only viewer who always expects Harry to try to throw his old friend out of the cabin.

The big wheel has been declared a site of European film culture and decorated with a more or less accurate image of the coy Lime.

My ride in the wagon was gentle and elating. I tried to replicate Harry’s POV on the “ants” below, whose lives, he says, can’t matter much.

A studio-based version of the Prater featured in the now mostly lost Josef von Sternberg film, The Case of Lena Smith (1929).

Oh, yeah–we also paid a visit to a street named for one of my favorite auteurs. See below.

Next up: Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato!

For information about Viennese film culture, thanks to Christoph Huber, his colleagues, and the indefatigable Ted Fendt. Thanks as well to Norman Shetler and two staff members at the Gartenbau cinema. Christoph, by the way, is an exceptional critic. You’ll learn from reading his essays in Cinema Scope.

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Much ado about noir things

From “The Killer,” Spirit Comics (8 December 1946), by Will Eisner and studio.

DB here:

This is my final effort to cram my latest book down the resisting gullet of the reading public. Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling has just come out in paperback and I’ve been using our blog to trace out some relevant ideas that surfaced in recent books and DVD releases. The first entry dealt with some general issues, the second with popular culture’s drive toward variation, the third with craft and auteurism. This one has murder on its mind.

Noir as mystery and mystique

Sorry, Wrong Number (1948).

Crime looms large in Reinventing Hollywood. But I forsake the usual category of film noir. It didn’t exist as a concept for the filmmakers or audiences of the day. It’s the creation of critics, first overseas and then, much later, here at home. That doesn’t make the category invalid, though. Many art-historical categories (Baroque, Gothic) are later inventions, and those can be illuminating. Still, I think we gain some understanding if we situate our inquiry, for a time at least, at the level of what people seemed to be trying to do at the time.

Put it another way. By focusing on noir as the model of Forties narrative, we miss the ways in which the films we pick out under that rubric participate in wider trends. We miss, for instance, the new importance of mystery in all plotting of the period.

In the 1930s, mystery was mostly confined to detective stories. Think of your prototypical 1930s movie; it’s unlikely to have a mystery at its center. (Okay, maybe we’re curious about the identity of Oz the Great and Powerful.) In the 1940s, though, filmmakers began to scatter mystery devices into other genres. Mystery became a central storytelling strategy for personal dramas (Citizen Kane, 1941; Keeper of the Flame, 1943), romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan, 1945), war films (Five Graves to Cairo, 1943), social comment films (Intruder in the Dust, 1949), and domestic melodrama (Mildred Pierce, 1945; The Locket, 1946; A Letter to Three Wives, 1948). Some of what we call noir is part of this trend.

Over the same period, a fairly minor genre got promoted. Psychological thrillers can be traced back to Gothic novels and sensation fiction, but they became a distinct part of crime literature in the 1930s. They became an important genre for cinema in the 1940s, and so Reinventing Hollywood devoted a chapter to films like The Spiral Staircase (1945) and Sorry, Wrong Number (1948).

These aren’t canonical “noir” films, at least if your notion of noir stems from hard-boiled fiction. Some rely on the guilty-party plot exemplified in C. S. Forester’s novel Payment Deferred (1926), Patrick Hamilton’s play Rope (1929), and Anthony Berkeley Cox’s novel Malice Aforethought (1931). Less famous but just as interesting is the “woman-in-peril” thriller.

This was an upmarket version of romantic suspense novels associated in earlier decades with Mary Roberts Rinehart and Mignon Eberhart. Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938), one of the top-selling books of the 1940s, lifted the genre to respectability. Revisiting traces the wide-ranging variations that followed in film, fiction, and theatre. (An early draft of that chapter is elsewhere on this site.) Mystery is central to this subgenre. Who is endangering the protagonist? What are the real motives of the people around her, especially her lover or husband? Are her friends complicit? How will she escape?

The gynocentric thriller remains powerful in popular literature today. We’re currently in a rapid-fire cycle of it, typified by the work of Laura Lippman and Gillian Flynn. Some of the books have come to the screen: Gone Girl (2014), The Girl on the Train (2016), and A Simple Favor (2018). The HBO series Big Little Lies (2017-on), turns a fairly satiric domestic-suspense novel into a heavier exploration of spousal abuse. I’ll be writing more about this cycle later (and giving a paper on it this summer), but let me note two recent examples. One takes its Forties sources for granted, the other flaunts them. Both are coming to a screen near you.

In Alex Michaelides’ new novel The Silent Patient Alicia Berenson, an emerging painter, is found guilty of shooting her husband. Because she seems in permanent shock and refuses to speak a word, she’s confined to a mental institution. There the ambitious young psychotherapist Theo Faber tries to ferret out why she remains silent. The narration alternates, Gone Girl fashion, between Theo’s first-person investigation and Alicia’s diary of events leading up to the killing.

It’s a spare tale narrated in a clumsy style that doesn’t distinguish the two voices. And it reminds us that if you become a character in a novel or movie, don’t get into a car. But it does show the persistence of Forties strategies.