Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt

Looking is as important in movies as talking is in in plays. Thanks to optical point-of-view shots (POV) and reaction-shot cutting, you can create a powerful drama without words.

Everybody knows this, but sometimes it’s good to be reminded. (I did that here long ago.) Now I have another occasion to explore this terrain. But first: How I spent my summer vacation.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

Because I was fussing with my own lectures, I missed the Rohmer events, unfortunately. I did catch all the De Palma lectures and some of the films. Cristina and Adrian offered powerful analyses of De Palma’s characteristic vision and style. I especially appreciated the chance to watch Carlito’s Way again (script by friend of the blog David Koepp) and to see on the big screen BDP’s last film Passion, which looked fine. I confess to preferring some of his contract movies (Mission: Impossible, The Untouchables, Snake Eyes) to some of his more personal projects, but he takes chances, which is a good thing.

Two of my lectures had ties to my book Reinventing Hollywood. “The Archaeology of Citizen Kane” (should probably have been called “An Archaeology…) pulled together things touched on in blogs, topics discussed at greater length in books, and things I’ve stumbled on more recently. Maybe I can float the newer bits and pieces here some time.

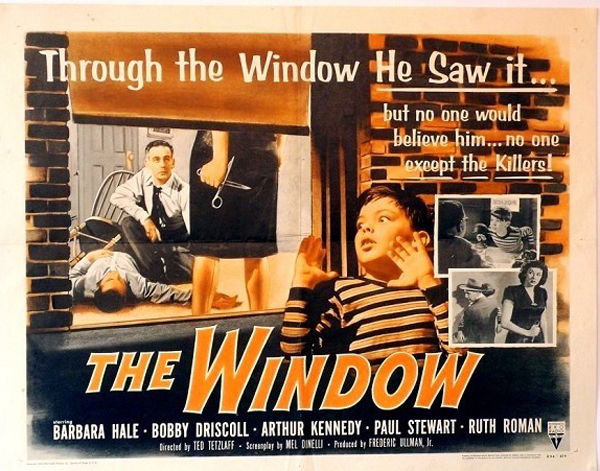

The other lecture took off from my book’s discussion of the emergence of the domestic thriller in the 1940s. We screened The Window (1949), a film that I hadn’t studied closely before. If you can see or resee it before reading on, you might want to do that. But the spoilers don’t come up for a while, and I’ll warn you when they’re impending.

Exploring the how

It is to the thriller that the American cinema owes the best of its inspirations.

Eric Rohmer

One strand of argument in Reinventing Hollywood goes like this.

During the 1930s Hollywood filmmakers mostly concentrated on adapting their storytelling traditions to sync sound and to new genres (the musical, the gangster film). By 1939 or so, those problems were largely solved. As a result, some ambitious filmmakers returned to narrative techniques that were fairly common in the silent era but had become rare in talkies. Those techniques–nonlinear plots, subjectivity, plays with viewpoint and overarching narration–were refined and expanded, thanks to sound technology and quite self-conscious efforts to create more complex viewing experiences.

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

It is not enough just to tell an interesting story. Half the battle depends on how you tell the story. As a matter of fact, the most important half depends on how you tell the story.

Put it another way. Very approximately, we might say that most 1930s pictures are “theatrical”–not just in being derived from plays (though many were) but in telling their stories through objective, external behavior. We infer characters’ inner lives from the way they talk and move, the way they respond to each other in situ. And the plot thrusts itself ever forward, chronologically, toward the big scenes that will tie together the strands of developing action. In this respect, even the stories derived from novels depend on this external, linear presentation.

In contrast, a lot of 1940s films are “novelistic” in shaping their plots through layers of time, in summoning a character or an omniscient voice to narrate the action, and in plunging us into the mental life of the characters through dreams, hallucinations, and bits of memory, both visual and auditory. We get to know characters a bit more subjectively, as they report their feelings in voice-over, or we grasp action through what they see and hear.

The distinction isn’t absolute. Some of these “novelistic” techniques were being applied on the stage as well, as a minor tradition from the 1910s on. I just want to signal, in a sketchy way, Hollywood’s 1940s turn toward more complex forms of subjectivity, time, and perspective–the sort of thing that became central for novelists in the wake of Henry James and Joseph Conrad.

In tandem with this greater formal ambition comes what we might call “thickening” of the film’s texture. Partly it’s seen in a fresh opennness to chiaroscuro lighting for a greater range of genres, to a willingness to pick unusual angles (high or low) and accentuate cuts. The thickening comes in characterization too, when we get tangled motives and enigmatic protagonists (not just Kane and Lydia but the triangles of Daisy Kenyon or The Woman on the Beach). There’s also a new sensitivity to audiovisual motifs that seem to decorate the core action–the stripey blinds of film noir but also symbolic objects (the snowstorm paperweights in Kane and Kitty Foyle, the locket in The Locket, the looming portraits and mirrors that seem to be everywhere). Add in greater weight put on density and details of staging, enhanced by recurring compositions, as I discuss in an earlier entry.

One genre that comes into its own at the period relies heavily on the new awareness of Zanuck’s how. That’s the psychological thriller.

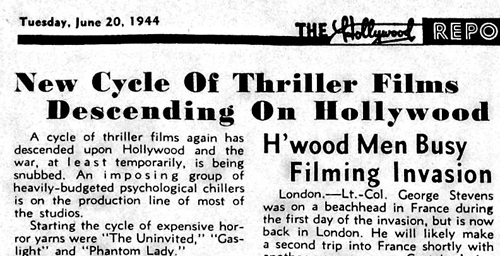

I’ve written at length about this characteristic 1940s genre (see the codicil below), so I’ll just recap. The 1930s and 1940s saw big changes in mystery literature generally. The white-gloved sleuth in the Holmes/Poirot/Wimsey vein met a rival in the hard-boiled detective. Just as important was the growing popularity of psychological thrillers set in familiar surroundings. The sources were many, going back to Wilkie Collins’ “sensation fiction” and leading to the influential works by Patrick Hamilton (Rope, Hangover Square, Gaslight). In the same years, the domestic thriller came to concentrate on women in peril, a format popularized by Mary Roberts Rinehart and brought to a pitch by Daphne du Maurier. The impulse was continued by many ingenious women novelists, notably Elizabeth Sanxay Holding and Margaret Millar. The domestic thriller was a mainstay of popular fiction, radio, and the theatre of the period, so naturally it made its way into cinema.

Literary thrillers play ingenious games with the conventions of the post-Jamesian novel. We get geometrically arrayed viewpoints (Vera Caspary’s Laura, Chris Massie’s The Green Circle) and fluid time shifts (John Franklin Bardin’s Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly). There are jolting switches of first-person narration (Kenneth Fearing’s The Big Clock), sometimes accessing dead characters (Fearing’s Dagger of the Mind). There are swirling plunges into what might be purely imaginary realms (Joel Townsley Rogers’ The Red Right Hand).

Ben Hecht remarked that mystery novels “are ingenious because they have to be.” Formal play, even trickery, is central to the genre, and misleading the reader is as important in a thriller as in a more orthodox detective story. No wonder that the genre suited filmmakers’ new eagerness to experiment with storytelling strategies.

Vision, danger, and the unreliable eyewitness

What does a thriller need in order to be thrilling? For one thing, central characters must be in mortal jeopardy. The protagonist is likely to be a target of impending violence. One variant is to build a plot around an attack on one victim, but to continue by centering on an investigator or witness to the first crime who becomes the new target. In Ministry of Fear, our hero brushes up against an espionage ring. While he pursues clues, the spies try to eliminate him.

Accordingly, the cinematic narration intensifies the situation of the character in peril. A tight restriction of knowledge to one character, as in Suspicion, builds curiosity and suspense as we wait for the unseen forces’ next move. Alternatively, a “moving-spotlight” narration can build the same qualities. In Notorious, we’re aware before Alicia is that Sebastian and his mother are poisoning her. Even “neutral” passages can mask story information through judiciously skipping over key events, as happens in the opening of Mildred Pierce.

Using point-of-view techniques to present the threats to the protagonist brought forth a distinctive 1940s cycle of eyewitness plots. Here the initial crime is seen, more or less, by a third party, and this act is displayed through optical POV devices. There typically follows a drama of doubt, as the eyewitness tries to convince people in authority that the crime has been committed. Part of the doubt arises from an interesting convention: the eyewitness is usually characterized as unreliable in some way. Sooner or later the perpetrator of the crime learns of the eyewitness and targets him or her for elimination. The cat-and-mouse game that ensues is usually resolved by the rescue of the witness.

The earliest 1940s plot of this type I’ve found isn’t a film, but rather Cornell Woolrich’s story “It Had to Be Murder,” published in Dime Detective in 1942. (It later became Hitchcock’s Rear Window. But see the codicil for earlier Woolrich examples.) The earliest film example from the period may be Universal’s Lady on a Train (1945), from an unpublished story by Leslie Charteris.

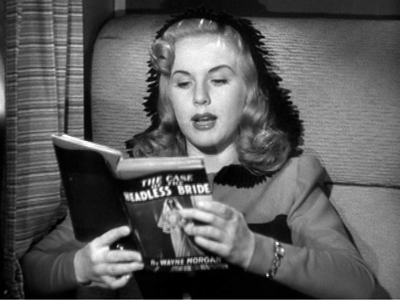

The opening signals that this will be a murder-she-said comedy. Nicki Collins is traveling from San Francisco to New York and reading aloud, in a state of tension, The Case of the Headless Bride (a dig at the Perry Mason series?). As the train pauses in its approach to Grand Central she comes to a climactic passage: “Somehow she forced her eyes to turn to the window. What horror she expected to see…” Nicki looks up from her book to see a quarrel in an apartment. One man lowers the curtain and bludgeons the other, and as Nicki reacts in surprise, the train moves on.

The over-the-shoulder framings don’t exactly mimic Nicki’s optical viewpoint, but they do attach us to her act of looking. Reverse-angle cuts show us her reactions. Her recital of the novel’s prose establishes her suggestibility and an overactive imagination. These qualities fulfill, in a screwball-comedy register, the convention of the witness’s potential unreliability. We know her perception is accurate, but her scatterbrained chatter justifies the skepticism of everybody she approaches. As the plot unrolls, her efforts to solve the mystery make her the killer’s new target.

More serious in tone was Lucille Fletcher’s radio drama, “The Thing in the Window” from 1946. In the same year, Cornell Woolrich rang a new change on the “Rear Window” theme with the short story “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” and Twentieth Century–Fox released Shock. In this thriller an anxious wife waits in a hotel room for her husband, who has been away at war for years. Elaine Jordan’s instability is indicated by a dream in which she stumbles down a long corridor toward an enormous door that she struggles to open.

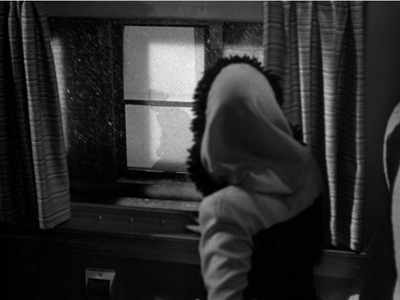

Awakening, Elaine nervously goes to the window in time to see a quarrel in an adjacent room. She watches as a man kills his wife.

Now she’s pushed over the edge. As bad luck would have it, the killer is a psychiatrist. When he learns that Elaine saw him, he takes charge of her case. He spirits her away to his private sanitarium, where he’ll keep her imprisoned with the help of his nurse-paramour.

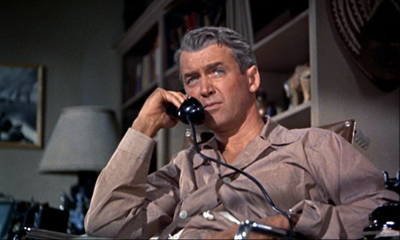

I was surprised to learn of this eyewitness-thriller cycle because the prototype of this plot was for me, and maybe you too, was a later film, Rear Window (1954). Again, the protagonist believes he’s seen a crime, though here it’s the circumstances around it rather than the act itself. Accordingly a great deal of the plot is taken up with the drama of doubt, as the chairbound Jeff investigates as best he can. He spies on his neighbor and recruits the help of his girlfriend Lisa and his police detective pal.

Hitchcock, coming from the spatial-confinement dramas Rope and Dial M for Murder, followed the Woolrich story in making his protagonist unable to leave his apartment. Following Woolrich’s astonishingly abstract descriptions of the protagonist’s views, Hitchcock made optical POV the basis of Jeff”s inquiry. By turning Woolrich’s protagonist into a photojournalist, he enhanced the premise through use of Jeff’s telephoto lenses.

Woolrich and Hitchcock’s reliance on spatial confinement worked to the advantage of the unreliable-witness convention. How much could you really see from that window? Jeff can’t check on the background information his cop friend reports. Besides, Jeff is bored and susceptible to conclusion-jumping. “Right now I’d welcome trouble.”

Hitchcock, who kept an eye on his competitors, doubtless was aware of The Window (1949), an earlier entry in the cycle. Derived from Woolrich’s “Boy Who Cried Wolf,” this RKO film has some intriguing things to teach us about the mechanics of thrillers and about the 1940s look and feel.

Spoilers follow.

At the window, and outside it

On a hot summer night, the boy Tommy Woodry is sleeping on a tenement fire escape one floor above his family’s apartment. He awakes to see Mr. and Mrs. Kellerson murder a sailor they have robbbed. Next morning Tommy tries to report the crime to his parents and then the police, but no one will believe him because he’s long been telling fantastic tales. A family emergency leaves him alone in the apartment, and the Kellersons lure him out. After nearly being killed by them, he flees to a tumbledown building nearby. There he evades Mr. Kellerson, who falls to his death. With Tommy’s parents and the police now believing him, he’s rescued from his perch on a precarious rafter.

Woolrich’s original story confines us strictly to Tommy’s range of knowledge, but in the interest of suspense screenwriter Mel Dinelli uses moving-spotlight narration. When Tommy flees the fire escape, for instance, we follow the efforts of the Kellersons to rid themselves of the body. This becomes important to show how difficult it will be for Tommy to prove his story. There’s also a moment during their coverup when the camera lingers on Mrs. Kellerson, both in profile and from the back, as if she were hesitating about going along with the plan.

This shot prepares for the climax, when as her husband is about to shove Tommy off the fire escape, she blocks his gesture and allows Tommy to escape across the rooftops.

Likewise, Woolrich’s story simply reports that the young hero waited at the police station for the result of Detective Ross’s visit to the Kellersons. The film’s narration attaches us to Ross and creates a scene of considerable suspense when we wonder if Ross will discover any clues to the murder. And whereas in the story Tommy must worry about how Kellerson will get to him, through crosscutting between Kellerson in the kitchen and Tommy locked in his room we know everything that’s happening. This permits a wry passage of suspense in which Kellerson toys with Tommy by letting him think he’s retrieving the door’s key.

In contrast to the moving-spotlight approach, though, crucial passages are rendered with a limited range of knowledge. Optically subjective shots come to the fore here, as when Tommy witnesses the murder.

It seems likely that Hitchcock’s early American films heightened filmmakers’ awareness of subjective optical techniques, and here director Ted Tetzlaff puts them to good use. The script I’ve seen for The Window doesn’t indicate such pure POV shots, instead opting for something like what we get in Lady on a Train. “CAMERA is ON the pillow back of Tommy, so that we see his head in the f.g and the window in the b.g.” There is a shot matching these directions, but it’s surrounded by the straight POV imagery framed by Tommy’s frightened stare.

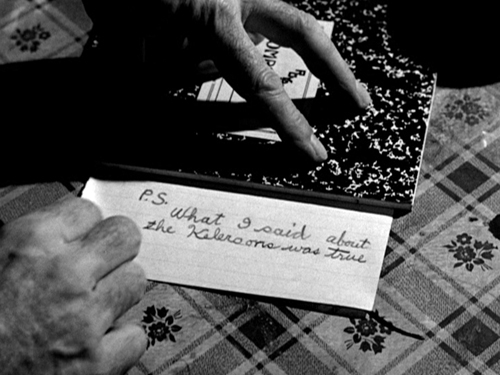

The decision by Tetzlaff and his colleagues to rely on optical POV is confirmed when, during Ross’s visit, he spots a stain on the floor.

Is this a bloodstain that will put Ross on the scent? Crucially, we haven’t seen the lethal scissors leave a trace. Kellerson explains the stain as coming from a leak in the ceiling. Obediently Ross looks up and, to prolong the suspense, so does Mrs. Kellerson, apparently as apprehensive as we are. That extra shot of her nicely delays the reveal: there is a leak above them.

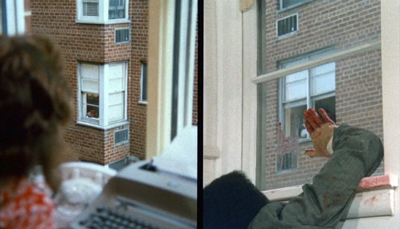

In tune with the tendency to thicken the narrative texture, this POV dynamic reappears at other moments. Tommy sees his parents leave, and the reverse angle reveals that the Kellersons see them too, and so they know that Tommy is now unguarded.

At the climax in the abandoned tenement, Tommy spots his father and the policeman outside. He shouts to get their attention, but they can’t hear.

But Kellerman does hear Tommy and uses the sound to stalk him.

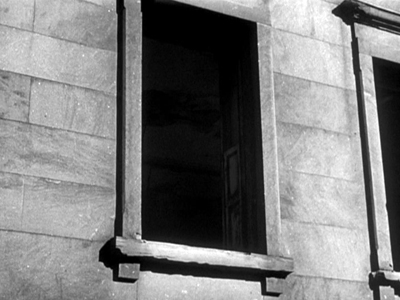

1940s stylistic thickening includes the use of audiovisual motifs that impose a distinctive look on the film. So a movie called The Window begins, after a couple of establishing shots of Manhattan street life, with a shot of a window.

This one has no special importance in the plot, but it announces the image that will recur throughout the movie. By shooting ordinary scenes through window frames, Tetzlaff reminds us that the locals live partly through those windows and the fire escapes outside.

Naturally enough, Kellerson plans to kill Tommy by having him tumble from the fire escape outside the window.

The film’s key image reappears at the end, when after Kellerson’s fall a new crop of witnesses take to their windows.

Another motif is the vertical link between the two apartments, given in looming shots of the staircase (a common piece of iconography in 1940s cinema) and in cutting that links Tommy’s bedroom to the Kellersons above him. He listens to their footsteps through his ceiling.

The next layer up, the rooftop, serves as a route from the families’ building to the abandoned one, and eventually the chase will play out there.

Vertical space more generally is important at the very start of the film. During Tommy’s mock ambush of his playmates, we look down over his shoulder. At the very end, Kellerson has trapped Tommy on the broken rafter.

The rooftop and rafter become part of another pattern, the circular one that rules the plot. Woolrich’s original story doesn’t feature the opening we have, showing Tommy in the abandoned tenement pretending to snipe at the other boys. Nor does the shooting script I’ve seen. Starting the film there establishes the locale of the climactic chase, while creating parallel scenes of Tommy hiding. We even get to see the broken rafter early on, when Tommy is prowling around his playmates.

The result is a pleasing, somewhat shocking symmetry of action: Tommy pretends to kill somebody at the start, and he succeeds in killing someone at the end.

The film offers a cluster of images that are recycled with variations, amplifying the basic story action through patterns of space and visual design.

The thickening of texture isn’t only pictorial. The drama of doubt involves a questioning of parental wisdom. Tommy’s mother actually endangers her boy by asking him to apologize to Mrs. Kellerson. More central is a testing of the father’s faith in his son. Tommy’s dilemma is to tell the truth even though he’ll be disbelieved by all the figures of social authority. The father’s increasingly desperate efforts to change Tommy’s story are revealed in Arthur Kennedy’s delicate portrayal of exasperation–at first gentle, then severe and nearly abusive.

Ed Woodry fails in his duty. The adults aren’t capable of protecting the child. A conventional plot would’ve had Ed redeem himself by rescuing his son, but the film we have leaves the killing to Tommy. It’s a grim condemnation of the people supposed to protect him.

Another convention, it seems, of the eyewitness film involves punishing the peeper. In Lady on a Train, Nicki has to brave a spooky house and risk death. Elaine of Shock suffers in the mental institution, and in Rear Window Jeff eventually falls from the very window that was his interface with the courtyard. Tommy, who acknowledges his inclination to tell whoppers, is subjected to a final burst of peril. After Kellerson has plunged to his death, Tommy is left in mid-air and he must jump to the firemen’s waiting net. In the epilogue, he announces that he’s learned his lesson, not least because of several brushes with death.

Revising the rules

The 1940s eyewitness cycle laid out some options for future thrillers. Rear Window, as we’ve seen, crystallizes the plot premise in rather pure form, and interestingly that was copied almost immediately in the Hong Kong film Rear Window (Hou chuang, 1955). Some passages are straight mimicry, albeit on a much smaller budget.

Thereafter, the eyewitness premise resurfaced, notably in Sisters (1973, with split screen) and with another child protagonist in The Client (1994).

In recent decades filmmakers have revised the premise in ways typical of post-Pulp-Fiction Hollywood. Vantage Point (2008) multiplies the eyewitnesses and uses replays to conceal and eventually reveal information. The Girl on the Train (2016), streamlining the multiple-viewpoint structure of the novel, alternates plotlines centered on three women. The novel and the film recast the eyewitness schema by making the eyewitness unable to recall exactly what she saw, thanks to an alcoholic blackout. (It’s a cousin to our old 1940s friend amnesia). This uncertainty raises the possibility that the eyewitness is actually the killer.

With its goal-directed protagonist and trim four-part plot structure, The Window is a completely classical film. As often happens, a forgivably flawed character gains our sympathy by being treated unfairly but triumphs in the end. And in the film’s integration of dramatic and pictorial elements, its alternation of subjectivity and wide-ranging narration for the sake of suspense, it nicely illustrates some ways in which 1940s filmmakers recast classical traditions for the thriller format and opened up new storytelling options.

Woolrich’s “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” is available under the title “Fire Escape” in Dead Man Blues (Lippincott, 1948), published under the pseudonym William Irish. Woolrich, ever the formalist, initially gave “It Had to Be Murder”/”Rear Window” my dream title: “Murder from a Fixed Viewpoint.” An earlier Woolrich story, “Wake Up with Death” from 1937, flips the viewpoint: A man emerges from drunken sleep to discover a murdered woman at his bedside and gets a call from someone who claims to have watched him commit the crime. Then there’s “Silhouette” from 1939, in which a couple witness a strangling projected on a window shade. See Francis M. Nevins, Jr.’s exhaustive Cornell Woolrich: First You Dream, Then You Die (Mysterious Press, 1988), 158, 186, 245. There are doubtless many earlier eyewitness thrillers, which the indefatigable Mike Grost could tabulate.

The screenplay by Mel Dinelli that I consulted, with help from Kristin, is a rather detailed shooting script dated 23 October 1947. It is housed in the Dore Schary collection at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Dinelli benefited from the thriller boom in his screenplays for The Spiral Staircase, The Reckless Moment, House by the River, Cause for Alarm!, and Beware, My Lovely.

There are plenty of discussions of thrillers on this site; try here and here. Apart from the chapter in Reinventing Hollywood, you can find overviews here and here. See also the category 1940s Hollywood. I discuss the sort of plot fragmentation characteristic of some current Hollywood cinema, built on 1940s premises, in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

For more images from my summer movie vacation, visit our Instagram page.

P.S. 24 July: Thanks very much to Bart Verbank for correcting my embarrassing name error in Rear Window! Also, if you’re wondering why I didn’t mention the very latest instantiation of the the eyewitness plot, A. J. Finn’s Woman in the Window, it’s because (a) I haven’t read it; and (b) I resist reading a book with a title swiped from a Fritz Lang movie.

DB accepts a fine Kriek from the Antwerp Summer Film College team: David Vanden Bossche, Tom Paulus, Lisa Colpaert, and Bart Versteirt.

FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL: A guest post by Jeff Smith

The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941).

Jeff here:

Last week, the latest in our series of “Observations on Film Art” videos dropped on FilmStruck. The topic this time was continuity editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.

Many of our faithful blog readers are surely familiar with the techniques and devices that make up the continuity system. The video is really intended to be a primer for the uninitiated. It illustrates some of the basic formal elements of classical continuity, such as the eyeline match, shot/reverse shot, and the 180° rule.

In the video, I tried to highlight some of the reasons why the continuity system became common among popular cinemas around the globe. The tacit principles of the continuity system help ensure that:

- the story’s dimensions of space and time are clearly communicated to the audience

- characters’ and objects’ positions remain relatively constant from shot to shot

- that eyelines and screen direction stay consistent

- the spectator’s attention is guided to the most salient details in a scene.

The last may be the most important, if least understood. Several perceptual psychologists argue that one of the things that makes cinema a unique art form is its ability to produce attentional synchrony among viewers.

Editing is not the only means of guiding attention, to be sure. Filmmakers use lighting, composition, figure movement, camera movement, and blocking to nudge us to look at particular areas of the frame. The continuity system, though, further harnesses these shifts of attention by yoking them to the timing of cuts. Cuts are often coordinated with natural attention cues in a scene, such as conversational turns, changes in where the characters look, and pointing gestures. As Tim J. Smith, Daniel Levin, and James E. Cutting put it, “By piggy-backing on natural visual cognition, Hollywood style presents a highly artificial sequence of viewpoints in a way that is easy to comprehend, does not require specific cognitive skills, and may even be perceived by viewers who have never watched film before.”

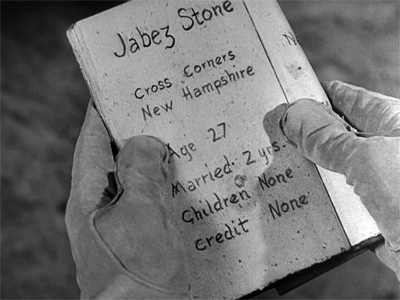

In its deployment of classical Hollywood editing techniques, The Devil and Daniel Webster doesn’t do anything particularly special. Rather, in telling the story of how a New Hampshire farmer, Jabez Stone, sold his soul to the devil, it beautifully illustrates the clarity and efficiency of Hollywood craft at the height of the studio era. Indeed, the editing epitomizes the style of director William Dieterle as a whole: simple, direct, no fuss, no muss.

That being said, The Devil and Daniel Webster does add a few wrinkles to the usual Hollywood style. For example, it uses “trick film” techniques dating back to the era of George Melies to highlight the magical powers of the diabolical Mr. Scratch.

When Jabez throws an axe, it is initially seen as a blur heading straight for Scratch’s head.

A combination of stop-motion substitution and rear projection shows the axe freeze in midair.

A traveling matte is then used as the axe bursts into flames.

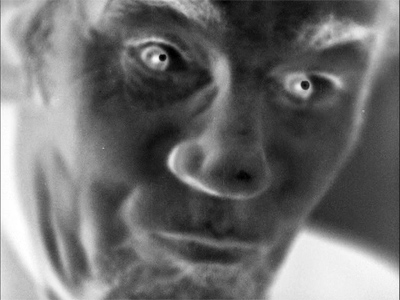

Moreover, the Criterion DVD contains deleted scenes from an earlier preview version of the film titled Here is a Man. This alternate version was, in fact, more formally adventurous than the one commonly seen by contemporary audiences. Each time something bad befalls Jabez during the first 20 minutes of the film, Here is a Man cuts to a few frames of photographic negative of Scratch. For instance, when Mary accidentally falls off a wagon, Dieterle cuts to Walter Huston smugly pursing his lips.

Dieterle and his collaborators wisely removed these shots from the final version of the film. The opening scene shows Scratch with Jabez’s name in a small book he carries with him.

When ruinous things start happening to Jabez, viewers naturally infer that Scratch caused them. The oddball moments in Here is a Man, unlike the other effects shots, don’t really add any new information and are heavy-handed in their symbolism.

The Long and the Short of It: Adapting Stephen Vincent Benét to the Silver Screen

Beyond offering good examples of editing craft, The Devil and Daniel Webster is of interest today for other reasons. One involves some of the creative choices made by Stephen Vincent Benét and Dan Totheroh in adapting the former’s short story, first published by The Saturday Evening Post in 1936. The second issue I’ll explore has to do with the way the film speaks to political issues of its moment. It seems endorse a collectivist vision of society as a counter to the excesses of unrestrained capitalism.

Most film adaptations use books for their source material, and most screenwriters face the challenge of condensing the book’s narrative to fit the running time of a typical feature film (roughly about two hours). In the case of The Devil and Daniel Webster, Benét and Totheroh faced the opposite problem.“The Devil and Daniel Webster” runs less than twenty pages in a Hythloday Press collection of Benét’s short stories. So how do you stretch Benét’s relatively slim tale to fit a 107 minute running time? Benét and Totheroh did what most screenwriters do when they confront the same dilemma. They add incidents, invent new characters, and develop new subplots, adding this material to the existing story spine.

Some print editions of Benét’s story break it into five parts with each new segment introduced with a Roman numeral. Part I introduces Daniel Webster via the tall tales told about him in the New England area. It also provides exposition to Jabez’s blighted existence, and the deal he makes with the devil. After breaking his plow on a stone, Jabez angrily proclaims, “I vow it’s enough to make a man want to sell his soul to the devil. And I would, too, for two cents!”

Part II covers the seven-year period of prosperity Jabez enjoys as well as his interest in contesting the mortgage held by the mysterious stranger. This section also establishes the stranger’s mystical powers as Jabez hears the voice of his neighbor, Miser Stevens, coming from a moth-like creature that the stranger captures in a bandanna.

Part III describes Jabez’s recruitment of Daniel Webster for his defense and the preparations for trial. Parts IV and V depict the trial itself. The former introduces the judge and jury, and portrays Daniel’s passionate defense of Jabez. The latter tells of the jury’s verdict and Daniel’s banishment of Mr. Scratch from New Hampshire.

One of the most striking things about Benét’s original story is how much of it focuses on the trial itself. Approximately half of the story covers Webster’s initial deliberations with Mr. Scratch, his demand for a trial, and the legal proceedings. In contrast, these story events account for less twenty percent of the film’s running time.

In expanding the story to feature length, Benét and Totheroh add new incidents, characters, and subplots to the early and middle sections of the screenplay. Consider, for example, Benét’s economy in his prose description of Jabez’s misfortunes:

If he planted corn, he got borers; if he planted potatoes, he got blight. He had good-enough land, but it didn’t prosper him; he had a decent wife and children, but the more children he had, the less there was to feed them. If stones cropped up in his neighbor’s field, boulders boiled up in his; if he had a horse with the spavins, he’d trade it for one with the staggers and give something extra.

Years of toil and trouble for Jabez are compressed into three sentences. When Jabez breaks his plowshare, it becomes simply the proverbial straw on the camel’s back, coming at a time when his wife and children are sick and even his horse has a rheumy cough.

In their script, Benét and Totheroh create a handful of new vignettes to illustrate Jabez’s rotten luck. In the film’s first scene, Jabez’s pig breaks its leg after being chased by the family dog. Later, Jabez’s wife, Mary, takes a tumble off their wagon when trying to stop her husband from selling the family’s calf. Still later, a fox gets into Jabez’s henhouse. In the film, Jabez’s breaking point comes not with the plow, but after he spills precious seed in a puddle just outside his barn. Unlike the story’s description of blight and corn borers, these brief episodes not only visualize Jabez’s tribulations, but also contain their own short dramatic arcs.

Another way Benét and Totheroh expand the original story is to add depth and specificity to its secondary characters. In the original, Miser Stevens never appears as anything more than an insect that’s escaped from Scratch’s collecting box. In the film, he is much more fully fleshed-out character, especially as embodied by the wonderful character actor, John Qualen.

Benét and Totheroh’s screenplay uses Stevens to create important story parallels. Like Scratch, who possesses a mortgage on Jabez’s soul, Stevens holds the mortgage to the Stone farm. Yet, Stevens also has made a Faustian bargain with Mr. Scratch. His death at Jabez’s party lingers over the rest of the film, a vivid reminder of what’s at stake during the trial.

Benét’s story also treats Jabez’s wife and children quite impersonally. The characters are never named. The references to them mostly add narrative weight to Jabez’s sense of burden. In contrast, the film version not only give these characters names and individual traits, but also uses them to highlight changes Jabez undergoes once he becomes a wealthy landowner. Jabez and his wife, Mary, frequently argue about disciplining their son, Daniel. Jabez indulges Daniel, spoiling him but offering little in the way of love. Similarly, after becoming successful, Jabez also falls short of what we’d expect of a caring husband.

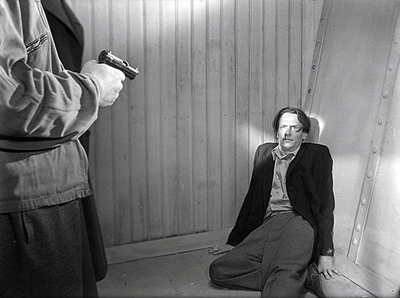

In the middle parts of the film, Jabez becomes crueler and harder. He starts treating trespassers on his land more harshly. He even fires a weapon at one in an effort to scare him away. His anti-social attitudes make him an outcast among the citizenry of Cross Corners.

As was the case with Jabez’s family, the film gives the townspeople more life and personality. Early on, they serve to motivate Daniel Webster’s presence in the story, welcoming him to Cross Corners and serving as a receptive audience for the Senator’s political views. Later, the townspeople act as a foil for Jabez, establishing an important thematic contrast between his laissez faire mindset and their more communitarian values.

Lastly, Benét and Totheroh also invent several new characters for the film adaptation. Of these, the most important is Belle. Loosely allied with Mr. Scratch, Belle is ostensibly Daniel’s nanny, but is implied to be Jabez’s mistress. Belle supplies a sexual temptation not present in the original story, and this complements the temptations of wealth and power. In this respect, the character anticipates the femme fatales found in the cycle of films noir that appear later in the forties, especially as played by Simone Simon at her most fetching.

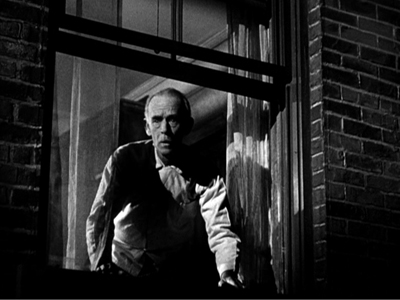

Although Dieterle was best known for costume pictures rather than film noir, the photographic style of The Devil and Daniel Webster sometimes displays the kind of dark, moody look we associate with noir’s Germanic influence. Consider, for example, the shot of Scratch’s entrance into Jabez’s barn. The mists, the backllight, and the gnarled tree in the background all foreshadow the darkness that will soon take hold of Jabez’s soul.

In the case of The Devil and Daniel Webster, tracing the film’s lineage back to German expressionism is fairly easy. Prior to becoming a director, Dieterle was an actor in dozens of German silent films, including F.W. Murnau’s Faust (1926). Murnau’s adaptation of Goethe’s play not only shares its narrative conceit with Dieterle’s film, but is also one of the most strikingly photographed of his twenties masterpieces.

Looking both backward and forward, The Devil and Daniel Webster might seem like a link between German Expressionism and American film noir. Like German films of the 1910s and 1920s, Dieterle’s film contains some of the fantasy elements found in canonical titles like The Student of Prague (1913), Der Golem (1915), or The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). Dieterle’s curious afterlife fantasy Six Hours to Live (1932), discussed in an earlier entry, has a strong affinity with Gothic and Expressionist imagery. Like films noir of the forties, the cinematographic style of The Devil and Daniel Webster captures the story’s dark, fatalistic tone.

Indeed, the look of the final trial scene displays the same sort of stylization seen in the dream sequence of The Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), a film often seen as a key noir progenitor.

Still, Dieterle also retains the folksy Americana that was an appealing part of Benét’s original story. Some of the characters, like Ma Stone or Squire Slossum, seem like they’ve wandered into the story from one of Frank Capra’s small towns or John Ford’s rural comedies. This combination makes The Devil and Daniel Webster a true original. Indeed, it might count as an almost singular example of “cracker barrel noir” if the term itself didn’t seem like a complete oxymoron.

Things That Make a Country a Country, and a Man a Man: Benét’s Tale as Allegory

One of the other things that interests me about The Devil and Daniel Webster is the degree to which both the story and the film can be read as allegory. Benét’s original narrative certainly makes American identity a central theme. The opening paragraph proposes that, if you go to Daniel Webster’s gravesite and call his name, you’ll hear his deep, rolling voice ask, “Neighbor, how stands the Union?” Benét adds, “Then you better answer the Union stands as she stood, rock-bottomed and coppersheathed, one and indivisible, or he’s liable to rear right out of the ground.” This description not only foreshadows the oratorical power that Webster will display when Jabez goes on trial, but also the sacrifices Scratch prophesies. These include Webster’s loss of two sons in combat and a missed opportunity to become president.

Later, Webster will challenge Scratch on the grounds of his nationality, saying “no American citizen may be forced into the service of a foreign prince.” Scratch responds that he is an American, and further that he was present for “the first wrong done to the first Indian” and when the first American slave ship set sail for the Congo. Moreover, when Scratch assembles his jury, he selects a group of black-hearted souls whose dark deeds affected the course of the nation’s history. Among them is the pirate Edward Teach, otherwise known as Blackbeard. There’s also Walter Butler, the architect of the Cherry Valley massacre; Simon Girty, who burnt men at the stake; and Governor Thomas Dale, who Benét claims “broke men on the wheel.” Overseeing the proceedings is Judge John Hathorne, a magistrate in Salem who supervised some of the witch trials.

The larger significance of these passages is hard to ignore. Jabez may be on trial within the narrative, but Benét seems to put America itself on trial. The plaintiff and defendant, thus, come to symbolize the yin and yang of America’s soul. Webster represents the virtues that define the American ethos: grit, pluck, ingenuity, and liberty. Scratch, on the other hand, associates himself with the nation’s original sins: genocide, slavery, cruelty, torture, and theocratic inquisition. Webster emerges victorious in the legal battle, but as he says in his summation, our citizens’ hard-won freedom came at a cost of suffering and tribulation. Successes and failures are all part of the great journey of humanity. Says Webster, “And everybody had played a part in it, even the traitors.”

Dieterle’s film preserves all of these elements of Benét’s short story, but adds a couple of wrinkles of its own. First, General Benedict Arnold is added to the film’s panel of jurors, even though he is pointedly absent from the original. In the story, Webster observes that he misses Arnold’s company and is told that the General is engaged in other business. Benedict Arnold is not only fully present in the film version, but is even featured prominently during the trial scene in several medium close-ups.

Webster even singles out Arnold in his impassioned defense of Jabez’s character. Using Arnold’s betrayal of his country as a cautionary tale, the orator asks the jury to give Jabez the second chance that the devil denied to them.

The other, even more important, change made by Benét and Totheroh is the subplot concerned with the formation of the Grange. Officially known as the Order of the Patrons of Husbandry, the Grange was founded in 1867 to promote the interests of farmers and rural communities. But Webster died in 1852. As an addition to the screenplay of The Devil and Daniel Webster, the Grange seems to be a historical anomaly.

So why this anachronistic subplot? The simple answer is that it sharpens the conflict between Jabez and the other townspeople. Not only is he differentiated in class, but he’s set apart by his personal values. The less obvious answer involves the film’s historical context. Released in 1941, the story of a lone holdout resisting the pressure of others in his community likely would evoke broader geopolitical issues. The plea for unity in the face of existential evil would seem to suggest The Devil and Daniel Webster works as an allegorical critique of American isolationism on the threshold of World War II.

Like other allegories, this type of reading follows a pattern of metaphorical substitution. The Grange becomes a stand-in for the Allied Powers. Scratch represents Hitler, Mussolini, Tojo, and other Axis leaders. And, as discussed above, Stone and Webster symbolize America itself.

Dieterle’s earlier career in Hollywood also offers some additional warrant for this interpretation. He was a German Jew who emigrated to the U.S. in 1930. His relocation was less about fleeing the Nazis than it was the opportunity to work for Warner Bros. Still, Dieterle bore witness to the corrosive effects of Nazi ideology, and his directorial assignments show a loose affiliation with anti-Fascist politics. He helmed The Life of Emile Zola, a Warners biopic that depicts the French author’s involvement in the Dreyfus affair. The film won the Oscar for Best Picture in 1938. Thanks to its timely exploration of anti-Semitism, Zola burnished Warner Bros. reputation as Hollywood’s most socially conscious studio.

That same year, Dieterle directed Blockade (1938) for producer Walter Wanger. Although it is mostly a routine espionage thriller, the film is now remembered as one of the few films Hollywood made about the Spanish civil war. As scripted by John Howard Lawson, who later was blacklisted as one of the Hollywood Ten, Blockade is now seen as an emblem of the Popular Front. Most film historians associate it with anti-Fascist politics, even though the film pointedly avoids identifying the Loyalist and Nationalist sides of the conflict.

Unlike these previous projects, The Devil and Daniel Webster positioned Dieterle as both producer and director. The creative decisions involved in the addition of the Grange subplot would seem more directly under his control. The film’s thematic emphasis on collective interests seems to suggest this political subtext in much the same way that Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat (1944) is sometimes viewed as a parable of democracy’s failure in the face of dictatorship.

In highlighting this allegorical dimension of The Devil and Daniel Webster, I don’t wish to suggest that it makes the film inherently more interesting. Indeed, like other allegorical interpretations, it seems a bit reductive and simplistic. More importantly, if taken too far, these types of interpretive strategies quickly become wrongheaded and even silly (i.e. Belle as a stand-in for Vichy collaboration).

Yet, I also can’t help but feel that The Devil and Daniel Webster’s invocation of American identity offers something important to a contemporary audience. If, like me, you bristle every time you hear “American interests” referenced as the reason to abandon the Paris Accords or to potentially withdraw from NATO, then you have a sense of the film’s relevance to our moment.

The whole arc of the Grange subplot seems to invert much contemporary political rhetoric insofar as it dramatizes the social benefits of the Commons and the individual tragedy of self-interest. In the parlance of our times, Jabez is a risk-taker, mortgaging his immortal soul for the promise of earthly riches. Yet, when we see the resulting inequality in Dieterle’s film, we recognize the situation for what it is. For Jabez, Miser Stevens, and other capitalist mountebanks, it is, quite literally, a deal with the devil. And that, consarn it, is a lesson that all modern viewers can take to heart.

A handy introduction to the continuity system can be found in Chapter 6 of Film Art.

To learn more about the role of editing in guiding viewers’ attention, see Tim J. Smith, Daniel Levin, and James E. Cutting, “A Window on Reality: Perceiving Edited Moving Images,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 21, no. 2 (2012): 107-113. A PDF of this essay can be found here.

Stephen Vincent Benét can be found in many places around the web, including here. Lotte Eisner’s The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt (1974, University of California Press) remains a useful introduction to the movement’s lighting and visual motifs. For more on the interpretation of films as political allegories, see my book Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds (2014, University of California Press).

The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941).

Bye bye Bologna

Lucky to Be a Woman (1955).

DB here:

How to sum up nine days of Cinema Ritrovato? I logged thirty-two features and half as many shorts and fragments, along with a few panels and workshops. Fate cursed me with the need to blog and to sleep, so I missed many prime items. And that’s including my (sad) decision not to revisit films I’d already seen, so I sacrificed new exposure to masterpieces from Ozu, Mizoguchi, Feuillade, Leone, de Sica, etc.

In this last Bologna roundup, all I can do is wave at some of the surprises and discoveries that captivated me.

Many of my pals praised the Mexican noir Western Rosauro Castro (1950), which I had to miss, but I did get compensated by Prisioneros de la Tierra (1939), an Argentine classic of romantic realism. The plot concerns the exploitation of peasant migrants forced to work in dire conditions. One scene, of a drunken doctor in the throes of the DTs, got a rise out of Jorge Luis Borges.

Even more shocking was the red-light melodrama Víctimas del Pecado (1951, above) by the great Emilio Fernández. A newborn baby dumped into a garbage can; a preening, sadistic pimp who can smoke, chew gum, and dance frantically at the same time; a nightclub dancer who tries to live righteously but winds up in prison for her pains; and several splashy music numbers–who could resist this? Not the Bologna audience, who burst into applause when, after slapping a child silly, said pimp got a quick and violent comeuppance. Of course the gorgeous cinematography of Gabriel Figueroa contributed a lot: One shot of a train blasting black smoke into the night would be enough to exalt a far less delirious movie.

Thanks to Dave Kehr of MoMA, who brought a sampler from his recent Fox retrospective, and to UCLA and other sources, aficionados of American studio cinema had no shortage of delights. Monta Bell’s Lights of Old Broadway (1925) gave Marion Davies a dual role as twins separated at birth and she made the most of half of it, playing a no-nonsense colleen who makes it big at Tony Pastor’s. Part of the fun was the film’s historical references: Teddy Roosevelt as an undisciplined schoolboy, Weber & Fields as a kiddie act, and a solicitous Thomas Edison urging the heroine to invest in electricity.

Ten years later, One More Spring (1935, above) from Henry King offered a gentle seriocomic Depression tale. Two homeless men squatting in a garage take in a woman who sleeps on the subway, and they try to make ends meet with the help of a kindly old couple. At first engagingly episodic in the McCarey manner, the plot gets more tightly bound when the old couple faces the loss of their savings. Janet Gaynor is endearing, as usual, and Warner Baxter brings his clipped energy to the role of a hopelessly optimistic failure. There are no villains. The banker struggles to save his depositors, though he’s frank enough to admit, “It’s all the fault of the Republicans. Still, I’ll vote for them in the next election. With the Democrats you never know what to expect.” Another big laugh from the crowd around me.

That Brennan Girl (1946) exemplified the opportunities that the boom in 1940s moviegoing offered downmarket studios. Apart from the second-tier cast and the warning “Not Suitable for Children,” the production’s B-plus aspirations were clear, yielding a surprisingly polished Republic picture (buffed up by a beautiful Paramount restoration). A woman raised by a predatory mother takes up petty theft and con games. She reforms, but after becoming a war widow she falls back into her old ways–endangering her baby in the process. That Brennan Girl could have served as an example in my Reinventing Hollywood book, since it flaunts a long flashback punctuated by dreams and bits of imaginary sound. Those narrative stratagems pervaded films at all budget levels.

That Brennan Girl (1946) exemplified the opportunities that the boom in 1940s moviegoing offered downmarket studios. Apart from the second-tier cast and the warning “Not Suitable for Children,” the production’s B-plus aspirations were clear, yielding a surprisingly polished Republic picture (buffed up by a beautiful Paramount restoration). A woman raised by a predatory mother takes up petty theft and con games. She reforms, but after becoming a war widow she falls back into her old ways–endangering her baby in the process. That Brennan Girl could have served as an example in my Reinventing Hollywood book, since it flaunts a long flashback punctuated by dreams and bits of imaginary sound. Those narrative stratagems pervaded films at all budget levels.

Another 1940s technique was the chaptered or block-constructed film, Holy Matrimony (1943), a genial comedy about switched identities, contains sections with titles like “But in 1907” and “And so in 1908.” The film, about a painter brought back to London from his tropical hideaway, reworks the Gauguin motif made famous by Maugham’s Moon and Sixpence (1919). Was this release an effort to build on Albert Lewin’s 1942 version of the novel? Monty Woolley plays himself, but Gracie Fields brought real warmth to the clever, ever practical woman who marries him.

Holy Matrimony was a welcome, if minor entry in the John Stahl retrospective. I had to miss the much-praised When Tomorrow Comes (1939) but was happy to break my rule of avoiding things I’d seen before when I had a chance to revisit Imitation of Life (1934). I persist in thinking this better than the Sirk version, not least because of its harder edge. Beatrice Pullman’s exploitation of her servant Delilah’s pancake recipe carries a sharp economic bite, and the brutal classroom scene yanks our emotions in many directions. (While Peola writhes in her seat, her mother asks innocently, “Has she been passin’?”) As in Stahl’s other 1930s efforts, his studiously neutral style is built out of profiled two shots in exceptionally long takes.

Ritrovato has always done well by its diva films, under the curatorship of Marianne Lewinsky. (They’ve just released a hot-pink box set of four classics.) In tribute to 1918 there were several star vehicles. I’ve already mentioned L’Avarazia (1918), an installment in a Francesca Bertini series devoted to the seven deadly sins.

Another high point was La Moglie di Claudio (1918), an exemplary tale of excess. When a movie starts by comparing its heroine to a spider, you know she means trouble. Cesarina (Pina Minichelli) two-times her husband, has an illegitimate child, flirts relentlessly with her husband’s protégé, collaborates with spies, and steals the plans to the cannon the husband has designed. She does it all in high style. As she dies, she falls clutching a window curtain.

In a fragment from Tosca (1918), we got a quick lesson in the illogical powers of cinematic composition. Tosca (Bertini again) visits her lover Mario in prison. Their furtive conversation is played out while the shadows of the guards come and go in the background. That’s a source of some suspense for us.

And for the couple as well. Instead of looking left at the offscreen window itself, which they could easily see, they–like us–turn to monitor the silhouettes.

It’s a nice variant on the background door or window so common in 1910s film.

Of all the surprises, the biggest for me was This Can’t Happen Here (aka High Tension, 1950), an Ingmar Bergman thriller. You read that right.

This Cold War intrigue shows spies from Liquidatsia (you read that right too) infiltrating a circle of refugees living in Sweden. The first half hour is soaked in noir aesthetics, with men in trenchcoats glimpsed in bursts of single-source lighting. The preposterous plot gives us a briefcase full of secret papers, attempted murder by hypodermic, torture scenes, and enemy agents acting impossibly suave at gunpoint. A cadre meets in a movie theatre playing a Disney cartoon, with Goofy’s offscreen gurgles punctuating an informer’s confession.

Bergman forbade screenings of the film, but Bologna was given the rare chance to reveal another side of his obsessions with brooding solitude and the pitfalls of love. Peter von Bagh’s illuminating essay included in the catalogue rightly emphasizes how in This Can’t Happen Here murder becomes the natural outcome of an unhappy marriage.

My visit was topped off by the charming Lucky to Be a Woman (1955) in the Mastroianni strand. Sophia Loren, looking like a million and a half bucks, plays a working girl accidentally turned into tabloid cheescake. Mastroianni is a louche photographer who can make her career. Bantering at breakneck speed, they thrust and parry for ninety-five minutes, all the while satirizing modeling, moviemaking, and the itchy palms of philandering middle-aged men. Mastroianni spins minutes of byplay out of an unlit cigarette, while La Loren plants herself like a statue in the foreground, facing us; if Marcello’s lucky, she may address him with a smoldering sidelong glance.

What’s not to like? After thirty-two years, Ritrovato’s magnificence is unflagging.

As usual, thanks must go to the core Ritrovato team: Festival Coordinator Guy Borlée (with appreciation for help with this entry) and the Directors (below). They and their corps of workers make this vastly complex celebration of cinema look easy. It’s actually a kind of miracle.

Ehsan Khoshbakht, Cecilia Cenciarelli, Mariann Lewinsky, and Gian Luca Farinelli.

Geoffrey O’Brien reviews REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in NYRB

Backfire (1950).

DB here:

The New York Review of Books has just published a review by Geoffrey O’Brien of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. This is a big deal for me.

I never thought my work would be reviewed in a publication I’ve subscribed to since my college days. And to be reviewed by O’Brien is a special honor. He’s one of those wide-ranging intellectuals who are rare today. He writes fiction and poetry, and offers criticism of film, literature, music, painting, and theatre. He’s ideally equipped to appraise my arguments about how 40s cinema drew on narrative conventions in adjacent arts. He’s also a connoisseur of the obscure and marginal in classic studio cinema.

I especially admire his writings on noir film and literature, on popular music, and his study of American cinema as a sort of popular hallucination. The Phantom Empire makes this case memorably, but the opening of his review catches the flavor too.

One night not long ago I found myself once again drawn into a movie from the tail end of the 1940s. This one, with the thoroughly generic title Backfire (not to be confused with Crossfire or Criss Cross or Backlash ), did not come with a high pedigree. It had sat on the shelf for two years after it was filmed in 1948, and afterward seems to have faded quickly from recollection. But movies of that time, when they emerge decades later, have devious ways of holding the attention: beguiling hooks and feints lead deeper into a maze whose inner reaches remain tantalizing no matter how many times those well-worn pathways have been explored, and no matter how many times the interior of the maze has led only to an empty space.

One night not long ago I found myself once again drawn into a movie from the tail end of the 1940s. This one, with the thoroughly generic title Backfire (not to be confused with Crossfire or Criss Cross or Backlash ), did not come with a high pedigree. It had sat on the shelf for two years after it was filmed in 1948, and afterward seems to have faded quickly from recollection. But movies of that time, when they emerge decades later, have devious ways of holding the attention: beguiling hooks and feints lead deeper into a maze whose inner reaches remain tantalizing no matter how many times those well-worn pathways have been explored, and no matter how many times the interior of the maze has led only to an empty space.

In a state of suspended fascination only just distinguishable from the preliminary stages of dreaming, I remained absorbed as documentary-style scenes of wounded war veterans recuperating at a hospital in Van Nuys, California, gave way to progressively more disjointed and often barely comprehensible episodes: an unidentified woman creeping in the dark into a patient’s room with a message about a missing war buddy, a murder investigation, a cleaning woman peering through a keyhole in a fleabag Los Angeles hotel, a winding path from mortuary to boxing arena to gambling den to the office of a particularly corrupt doctor, a plaintive piano theme playing over and over accompanied by reminiscences of its origin in a far-off Austrian village. The story splintered into flashbacks, spiraling into deepening confusions of identity and chronology, punctuated, as if to keep the spectator awake, by a series of point-blank shootings.

All the while, the dialogue was evoking the trauma of wartime injury, questioning the difference between memory and hallucination, talking about nightclub rackets, tax evasion, gambling debts, obsessive love, as the narrative coiled in its final swerve toward a strangling, silhouetted on a bedroom wall while Christmas carols were sung in the background. And then, abruptly, the nightmare was over, we were back in the veterans’ hospital after a second and successful round of rehabilitation, and the three surviving principal characters were even managing to laugh as they took off in their jeep for Happy Valley Ranch. By then I could hardly have said what the movie was about or even if it was especially good—few viewers have ever thought so—yet could not deny that something had caught me in its grip and stirred up troubling associations, like partially retrieved memories of a parallel life.

Apart from wishing I could write like this, I find myself agreeing. Popular culture does offer us a phantasmagoric alternative world that we can drift through in an almost somnambulistic way. I don’t see this argument as the sort of Zeitgeisty criticism I’ve complained about elsewhere. Rather, I think it’s in the spirit of Parker Tyler, who saw Hollywood not as reflecting a collective psyche but as building occasionally rickety story worlds out of cultural flotsam scavenged from wherever. Not a mirror but a mirage.

That hallucination demands that conventions and schemas, norms and forms, bring order to an occasionally demotic array of materials. Given this orientation, the sort of analysis I float in Reinventing Hollywood might seem to be overthought and flat-footed. But O’Brien gets into both the book’s research assumptions and its ambitions. He sees that I was trying to figure out how the dépaysment of Forties cinema stems from the frantic pressures of the industry, ambitious filmmakers itching to explore unusual narrative strategies, and the jolts that occur when time schemes collide, motives get muddled, and story premises wriggle out of control. To savor eccentricities, you need the sense of a center, and that’s where my inquiry starts.

It’s a generous review. O’Brien makes my arguments crisp and cogent, and he adds ideas of his own. It’s a review that both fans and nonspecialists can learn from, as I did. It’s also good to know that some of my jokes didn’t fall flat. (I can hear readers asking: Wait, there were jokes?)

For more on Reinventing Hollywood, go to the tag 1940s Hollywood. The book is available from the University of Chicago Press website and the mighty Amazon. As ever, I owe thanks to the University of Chicago Press staff, particularly Rodney Powell, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Levi Stahl, and Melinda Kennedy.

I discuss Parker Tyler’s conception of the Hollywood Hallucination in The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture.