Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight

Idle Wives (1916), produced by Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley.

DB here:

This year I’ve been bouncing between two magnificently creative decades in US film, the 1910s and the 1940s. In autumn I’ve been caught up in things involving Reinventing Hollywood, but those were followed by some big doings on campus.

In spring I was lucky enough to be in residence at the John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress. That enabled me to watch nearly a hundred feature films from 1914-1918. I did a talk at the Library reporting on some of that work, and I’ve offered some preliminary observations on those in earlier entries.

Last week, Jim Healy of our UW Cinematheque brought some of the films that had impressed me during my DC stay. There was a Saturday marathon of The Iced Bullet (1917), Alias Jimmy Valentine (1915), The Bargain (1914), Will Power (1913), and The Man from Home (1914). For our Film Studies Colloquium across two Thursdays we screened False Colours (1914; incomplete), The Case of Becky (1915), Idle Wives (1916; incomplete), and Ben Blair (1916). Some of these I’ve written about in earlier entries, here flagged by links.

The Saturday screenings were accompanied by the lively, indefatigable playing of David Drazin. David worked for many hours and without having seen the films in advance. He’s a superb artist.

Seeing the films again, of course I found more to say.

Revival and revision

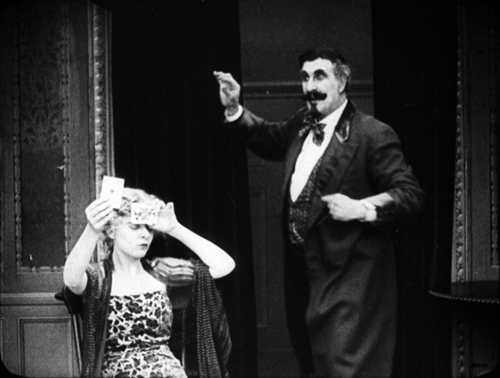

The Case of Becky (1915).

One of the secondary arguments in Reinventing Hollywood is that many storytelling techniques of silent film subsided during the 1930s but were revived during the 1940s. Silent films were full of dream sequences, subjective points of view, fantasy projections, and flashbacks. Those got elaborated and consolidated for the sound cinema by Forties filmmakers.

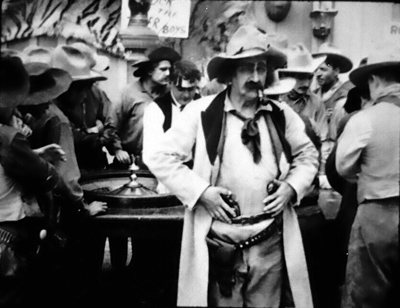

So it wasn’t surprising to find that The Bargain, a fine William S. Hart western, squeezed a lot of mental imagery into a single scene. The Sheriff has arrested Jim Stokes and retrieved the money he stole. Lashed to the bedpost, Jim remembers his wedding and the woman he’s betrayed, presented in a slow dissolve to the past.

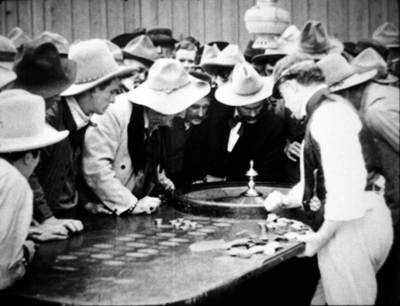

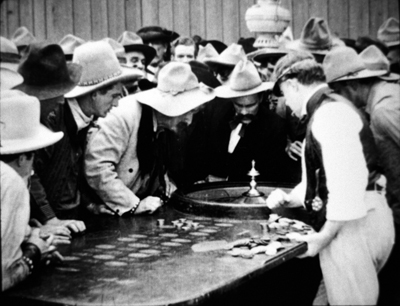

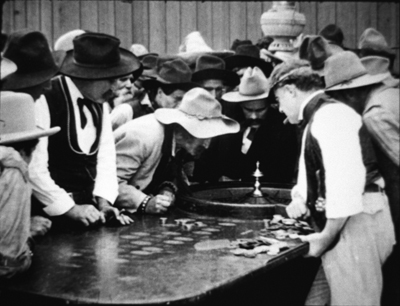

Meanwhile, downstairs in the saloon casino, the Sheriff succumbs to an impulse and loses all his money at roulette. Then he remembers, via another dissolved-in flashback, that he scooped up the stolen money too.

Back in the present, he digs that money out of his poke and bets it—and loses.

Later, in the hotel room, Stokes learns of the Sheriff’s folly and has a good laugh. But then he imagines Nell waiting for him, shown in a split-screen image.

At which point the Sheriff imagines his telegram arriving at his town, announcing Jim’s capture and the recovery of the money. That vision reminds him that he can’t return without the money he has squandered.

This makes him strike the central bargain with the thief he’s captured.

In a 1930s film, these visualized memories would most likely be presented verbally, as part of the stream of dialogue. (“When I think of marrying Nell….””I’ve promised to bring the money back…”). But 1910s American films tended to use dialogue titles sparingly; a lot of the films we saw asked the viewer to grasp the situation without benefit of words. The Bargain has only nineteen dialogue titles in 77 minutes (at 16 frames per second).

The Bargain is a good example of how purely pictorial storytelling was used to explicate a situation. Interestingly, today’s films are rather close to this tendency: fragmentary flashbacks and mental visions are common in mainstream movies.

Another echo struck me, this time in The Case of Becky. This is an early story of split personality, a narrative premise popularized after The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886). Here the young woman Dorothy (Blanche Sweet), under the sway of the sinister hypnotist Balzamo, develops a second identity, the surly and disruptive Becky. Becky isn’t really very dangerous, but when a young doctor, himself a master of hypnosis, falls in love with Dorothy, he determines to cast out Becky. He does so in a passage of intense mind control, visualized through a double exposure of Becky departing Dorothy’s body.

What interested me is that the same visual device was used by Arch Oboler in Bewitched (1945), one of the earliest psychoanalytical films of that era. The heroine’s two sides are summoned up by the shrink.

I suspect that Oboler got wind of the Selznick/Hitchcock Spellbound (1945) and rushed a B-film into production. (He could move fast because he adapted one of his radio plays.) Bewitched was released five months before the Selznick/Hitchcock film. It’s not great movie, but it has a sort of pre-Psycho pitilessness, and it’s always nifty to see a 40s film picking up on a silent-film device.

Cutting things up and filling the corners

My main research questions about the 1910s revolved around stylistics—matters of staging, lighting, shot scale, variety of camera setup, and editing choices. For about twenty years I’ve been exploring how, to put it broadly, the long-take, intricately staged tableau cinema was largely replaced by films dependent on continuity editing. By focusing on the years 1914-1918, I thought I could track the transition in finer grain.

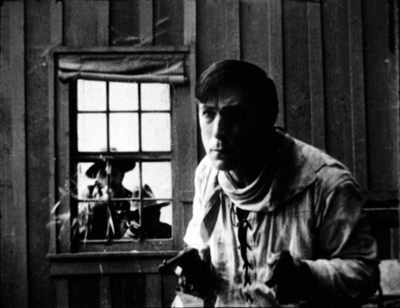

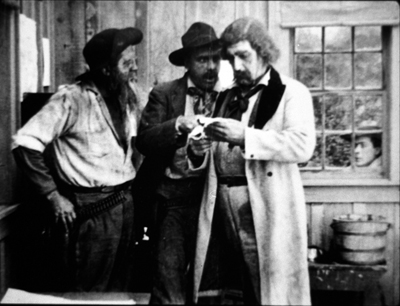

Many films were already building their scenes out of several shots. Go back to The Bargain, from 1914. A series of shots shows Stokes surrounded at the door and window, while also giving us a brief shot from a new angle incorporating tight depth, as the men at the window get the drop on him.

This freedom of camera placement within a single set is typical of the Hart films (see here and here), and of other films by Reginald Barker. It was sometimes visible in Alias Jimmy Valentine from the year before (1913), but it’s more pronounced in The Bargain. Several scenes in the hotel room where Stokes is tied up display a fairly wide array of camera setups.

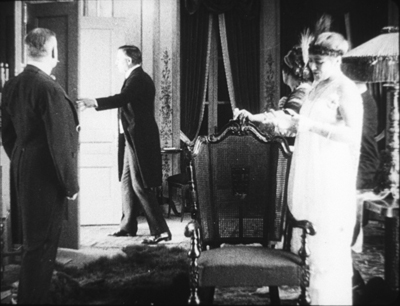

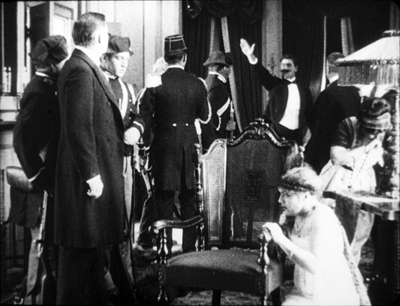

At the other extreme, The Man from Home (1914), credited to Cecil B. De Mille and Oscar Apfel, displays the tableau approach in full bloom. One long take at the climax shows a packed salon. To take just the high points of some pretty dense choreography: Ivanoff bursts in to confront his errant wife, who crumples in the lower right.

Pike holds off the Earl of Hawcastle, now partnered with Ivanoff’s wife. Hawcastle rushes to the right rear to open the curtains (stepping into a spotlight). Summoning the police, he returns to the middle ground to demand the arrest of the fugitive Ivanoff.

But a functionary arrives in the background, lifting his arm to signal the arrival of the bearded Grand Duke Vasili. Vasilii stalks in to take command of the middle ground and confront Hawcastle. Throughout. shrewd shifts of actors’ position open pockets of action, and the performers turn from the camera to drive our eye into depth.

Throughout most of this tableau, broken by occasional titles, Ivanoff’s treacherous wife is crouching in the lower right. This is an example of the “all-over staging” we find in 1910s cinema. Often corners and edges of the frame will be activated and demand to be noticed. For example, in The Bargain Stokes is observing a scene through a window. Cut inside the room, and Stokes can be seen way off to the right in a single pane.

Later directors would have placed the window nearer frame center so that Stokes’ face would be more quickly noticed.

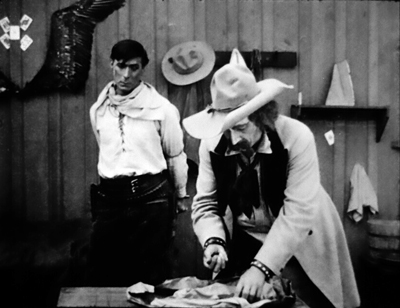

Sometimes we find the filmmaker trusting the audience—or at least a modern audience—too much. In Ben Blair (1916), Ben is lured into a brothel and pulls his pistol in order to escape. But in the master shot, off to the right, the astute viewer can see the louche Sidwell, who’s aiming to marry Flo, cozying up to a hooker before he rises to flee the room. He has already met Ben and fears being recognized.

Director William Desmond Taylor doesn’t supply what I expect Barker would provide: a separate shot of Sidwell seeing Ben and rushing out of the room. Nor does Taylor provide a gradually unfolding tableau that would, by means of figure movement, frontality, centering, and other cues build to a crescendo revealing Sidwell’s presence—the sort of thing we see in The Man from Home. As it is, many viewers may miss the main point of the scene, which is to divulge Sidwell’s sexual betrayal of Flo.

But maybe this was best. Cutting straight in to Sidwell might have suggested that Ben recognizes him immediately. But he doesn’t. As Ben turns, Sidwell is ducking away. Ben has revealed, and seems to be concentrating, on a new center of interest, the woman who’s impudently blowing out cigarette smoke at him. He, like us, is distracted from Sidwell’s departure.

Still, we’re supposed to spot Sidwell even if Ben doesn’t. Only much later, after Sidwell has nearly convinced Ben to give up on courting Flo, does Ben realize that it was Sidwell he saw in the brothel. That’s done through a split-screen flashback of Sidwell starting guiltily beside his floozy.

Again, the shot is a little clumsy in showing Sidwell looking toward the camera, as if Ben saw him directly; but it seems to be another mental image, representing Ben’s now-clear impression that Sidwell was in the brothel.

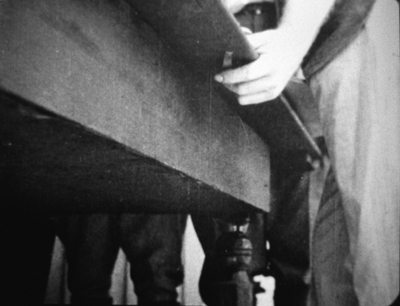

We don’t have to puzzle over such matters in The Bargain. Barker had mastered the precision necessary for off-center details. When the Sheriff is risking his money at the roulette wheel, a close-up reveals that the croupier is controlling it.

But here’s the neat part. At the turning point, when the Sheriff loses everything, Barker gives us close-ups of the Sheriff and the croupier, but not the hand pressing the button.

We’re sufficiently trained to spot the croupier pressing the button in the long shot (again, off-center). There’s no need to show the gesture again because the priming close-up has told us the game is fixed. Interestingly, that insert shot doesn’t come at the very start of the Sheriff’s gambling jag, so initially we might think the wheel is honest. We get the revelation just when the Sheriff is about to bet the money he can’t afford to lose. That boosts the dramatic tension.

Movies within movies

The Iced Bullet (1917).

While stylistics was my prime research focus, I couldn’t help but notice some bold narrative initiatives. A good example of a playful one was The Iced Bullet (1917), which has a Russian-doll structure (like many 40s films).

The inner tale recounts how a scientific detective solves an attempted murder, one using the method tipped in the title. But that’s swallowed up in a prologue and epilogue showing a foppish author crashing the Ince studio. He manages to interfere with filming, evade the guards, and take refuge in an executive’s office. He has brought along his screenplay, The Iced Bullet, which he hopes to direct and star in.

At the desk he falls asleep and dreams the detective story we see. At the film’s end he wakes up and flees the studio, pursued by watchmen. One trade paper of the time suggests that the comic frame story was devised in order to expand and elevate the murder story–which may explain why the film has been credited to both Reginald Barker and Charles Swickard. Maybe one directed the frame story and one the embedded one.

As the frame story stands, it offers us not only a comic pretext but precious views of the vast Ince studio.

There are also some nerdish in-jokes. C. Gardner Sullivan, author of the whole film we see, appears as the executive whose office is commandeered, while Barker shows up as a raging director trying to get the aspiring screenwriter off the set.

And when that invader takes over Sullivan’s office, he scoffs at a huge bust of William S. Hart, by now a major star.

The year before, Lois Weber and her husband Phillips Smalley had given us a more intricate film-within-a-film structure. The central story of Idle Wives centers on the plights of three women. Anne Wall is a wealthy but disillusioned wife who leaves her husband John to take up settlement work. She lives with Alberta, who has married John’s brother Richard. The couple has been disowned by John’s mother and sister. In her charity duties Anne meets Molly Shane, who has left her family to run off with the no-good Larry. Anne helps Molly through her pregnancy and reconciles her with her family. John, seeing how Anne has changed the lives of unfortunate women, welcomes her back and faces down the disapproval of his mother and sister.

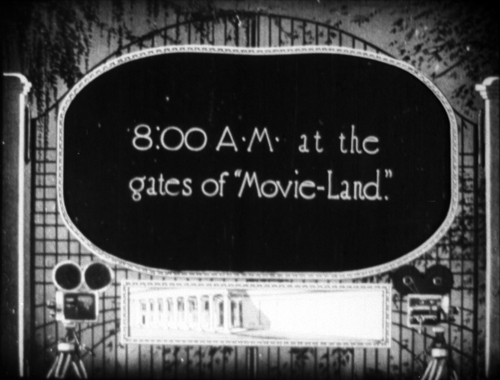

This story is enclosed within another one, involving three other women. The Jamiesons, though wealthy, have an empty marriage. When Jamison meets an old girlfriend, they decide to go see a movie. They’re trailed by Mrs. Jamieson. At the same time, Mary Wells disobeys her mother and goes out with the thug Tough Burns. They wind up going to the same movie theatre. And the poor, hard-working Smith family, whose daughter is longing to escape, decides to take a day off and go to the theatre as well. All of them join the audience for Life’s Mirror, a film by none other than….Lois Weber. It stars Weber and Philips Smalley, who’s given his own poster.

This frame story, not in the source novel, is pretty stunning. In the first reel the people assemble at the theatre, which, as you see up top, flaunts the Weber-Smalley brand. These scenes are fascinating representations of moviegoing culture of the time, showing the ticket booth and the auditorium.

Just as important is the way that seeing the movie affects the characters in the frame story. Shots show people in the audience reacting to the fictional world.

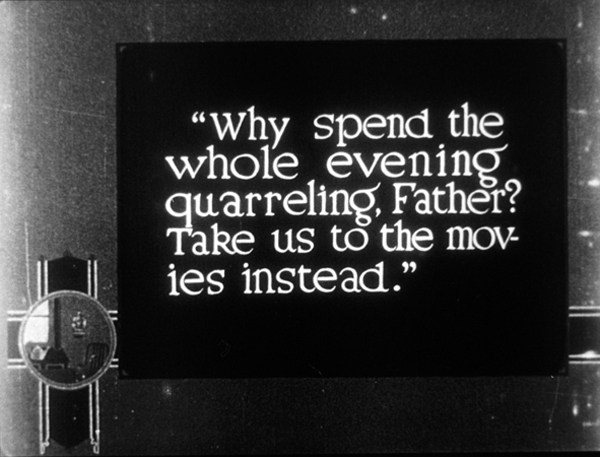

The point of the film is that the characters, recognizing their counterparts on the screen, improve their behavior. Cinema is granted the power to divine the problems of its audience, and to heal their lives.

Or so we’re told from contemporaneous synopses. Because, in one of the great losses of American silent cinema, we have only the first and second reels of Idle Wives. Fortunately, those constitute the prologue and the initial exposition of the inner story.

How does the frame story turn out? According to the fullest contemporary account I’ve seen, in the epilogue Jamieson sees his wife weeping in the aisle, sends her rival away, and reconciles with her. Mary is shocked into realizing the risk of dating Tough Burns, who seems ready to reform after seeing his fictional double behave so cruelly. The Smiths agree to be kinder to one another, and the daughter of the family realizes the danger of fleeing home.

Two network narratives, then, in a single movie. Idle Wives has over twenty individuated characters, linked by kinship or domestic circumstances. (For instance, in both stories some characters live in the same building.) It becomes didactic, as Weber’s films often are, with the theatre presenting a placard that underscores the lessons, and opening titles that address the audience directly. Idle Wives was fairly described by a review as “a preachment on the sacredness of the home, also on the power of the motion picture.”

For most film historians, the great experimental film of 1916 was Intolerance, another tale of parallel situations and fates. But the same month that Griffith’s ungainly masterpiece was released saw the appearance of Idle Wives—in its way, no less daring, and by today’s standards startlingly modern. How many other remarkable films have been lost or have gone unnoticed? Like archaeologists excavating a site, we have a lot more digging to do to understand the glories and unpredictable experimentation of the cinema of the 1910s.

Thanks to my hosts at the Kluge Center last spring: Ted Widmer, Emily Coccia, Travis Hensley, Callie Mosley, Mary Lou Reker, and Dan Turello, as well as the team in the Moving Image Research Center–Karen Fishman, Dorinda Hartmann, Josie Walters-Johnston, Zoran Sinobad, Rosemary Hanes, and Alan Gevinson–along with the Culpeper dynamic duo Mike Mashon and Greg Lukow. We in Madison are especially grateful to Lynanne Schweighofer and George Willemen for preparing a reconstructed version of Ben Blair. Thanks also to Jim Healy, Mike King, and Roch Gersbach for arranging the Madison screenings.

Some of David Drazin’s piano accompaniments are available on DVDs from Texas Guinan (that’s right, tguinan at aol.com).

Idle Wives has been posted online by the New Zealand Film Archive and the Library of Congress. An informative puff piece from the era is “The Smalleys Turn Out Masterpieces With Actors or With Types,” The Moving Picture Weekly 3, 14 (18 November 1916), 18-19, 26. The most comprehensive guide to Lois Weber’s career is Shelley Stamp’s Lois Weber in Early Hollywood (University of California Press, 2015). I discuss the Smalleys’ little masterpiece Suspense (1913) here. Reinventing Hollywood has a chapter on the psychoanalytic cycle of the 40s, including Bewitched.

On all-over staging, and bungling the tableau, see the entry “Looking different today?” We have some entries on decentered framing, one on Mad Max: Fury Road and another on Fritz Lang’s use of corner frame space.

Idle Wives (1916).

The Fabulous Forties once more: REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD spreads out on the Net

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

DB here:

A couple of weeks ago, when I was in New York for the Museum of the Moving Image series based on Reinventing Hollywood, I also met with Violet Lucca, who runs the admirable Film Comment podcast. She and Imogen Sara Smith talked with me about the book. Our conversation is here.

Our session helped me to develop, somewhat babblingly, points I only touched on in the book. For example, there’s the idea that 1940s films aimed at a certain “novelistic” density (or heaviness, if you’re not sympathetic to them). That’s opposed to the fast-paced “theatricality” of many 1930s films. Of course there are exceptions, and complete outliers like The Sin of Nora Moran, a favorite of mine that Imogen mentioned.

Likewise, I got to reemphasize how filmmakers transformed conventions from fiction, theatre, and radio. And Violet and Imogen were right to draw me out on the role of the screenwriter, which I emphasized more than in my previous research.

It was not only fun but illuminating. Violet and Imogen are very knowledgeable and offered me many good ideas that expanded or nuanced things I tried to say. For example, Violet asked whether the “competitive cooperation” of the 1940s has an echo today. That seems right. Imogen suggested that the emergence of voice-over allowed actors to develop an impassive, internalized acting style characteristic of the 1940s. I wish I’d thought of that. In fact, I wish I’d talked with this pair before I wrote the book.

And yes, Daisy Kenyon is involved.

Also a click away from you is an extract from the book put up on Lapham’s Quarterly. It pulls a section from the first chapter about how amnesia works in popular storytelling. Maybe you’ll find it interesting.

Finally, Daniel Hodges kindly spotlighted Reinventing Hollywood in his very serious, in-depth website devoted to problems of film noir. While my book doesn’t say much about noir, since that wasn’t an operative category for creators of the period, my discussion of the woman-in-peril plot chimes with his very detailed study of many films in this vein. In addition, Daniel offers subtle suggestions about less-discussed sources of noir visual style, and he makes a strong case for spy films as being as important to the trend as hardboiled detective stories.

Thanks to Violet and Imogen for a very enjoyable hour, to Daniel for the link, to Lapham’s Quarterly, and to Rodney Powell and Melinda Kennedy of the University of Chicago Press.

The Sin of Nora Moran (1933).

Biomechanics goes to the Big House: BRUTE FORCE on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

If there’s one film technique that probably everybody notices, it’s acting. Reviewers are obliged to judge performances, and viewers often comment that this or that actor was admirably controlled, or wooden, or over the top. Yet acting is surprisingly hard to describe; the critic who can do it engagingly, as Pauline Kael could, wins plaudits.

I think it’s fair to say that film analysts haven’t on the whole found good ways to analyze acting. There are books about historical acting styles, and there’s a very good theoretical overview by—no surprise—Jim Naremore. Our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs have produced a superb study of acting in the early feature film, with careful attention to the conventions of the period. But I think there’s still more to be done in terms of analyzing how performers achieve their expressive effects.

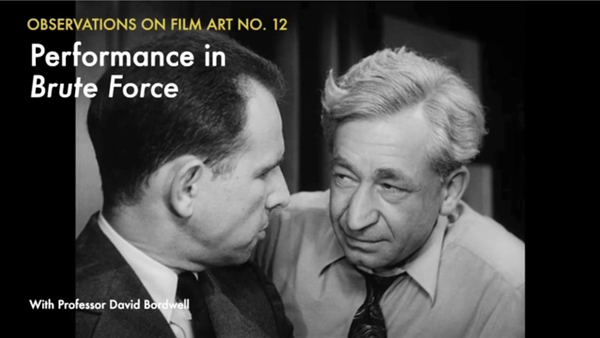

Or so I suggest in the newest installment of our series, “Observations on Film Art,” on the Criterion Channel of FilmStruck. Using Brute Force as an example, I try to lay out in brief compass some primary tools that actors wield. There’s an excerpt here. Today I’ll sketch out what I tried to do.

Bits selected and amplified

Talk about acting tends to set “realism” or “verisimilitude” against “artifice” or “stylization.” The Method, we sometimes say, is an example of realism, while Expressionist acting à la Caligari is at the opposite pole. Classic Hollywood acting, from the late 1910s into the 1940s, we might say ranges across the middle.

Accordingly, some theorists of acting are realists, favoring one zone and finding the other too artificial. Others are conventionalists; they argue that all acting, even the most apparently realistic, is actually stereotyped. It looks realistic because we accept the conventions of a time or tradition as the way people actually behave.

I think it’s worth suspending this polarity and simply looking at how performances are built up out of pieces. Like Meyerhold’s Biomechanics and Kuleshov’s engineering approach to acting, my perspective here is that of seeing performances as clusters of controlled choices about specific bodily behaviors.

As a first approximation, I propose that acting of any sort starts with some norms of human facial, vocal, and bodily expression.

Many of those norms might be universal. I’m risking disagreement here, since the US humanities are predicated on a fairly radical relativism. But I think that’s implausible. Is there any culture where smiling reliably indicates unhappiness? When frowning and shaking your fist in someone’s face indicates affection? Where pointedly turning your back on someone shows a willingness to engage socially? Where sloping your shoulders, tipping up your inner eyebrows, rearing back your head, turning down your mouth, and wailing indicates joy rather than misery? (The guitar-hugging rocker’s cry of anguished teen spirit draws on the ensemble of cues we see in the mother cradling her wounded child.) Nobody expresses pride by dropping to a crawl.

The context can qualify or negate these signals, of course. One may smile and smile and be a villain. But exactly because cordial smiling isn’t the default signal of villainous purpose, Shakespeare is able to make his point about deception. Any expression can be faked; that’s what acting is. At bottom, though, taken singly and reinforced by other inputs and circumstance, there are some reliable expressive cues in the typical case.

But even if you believe in the social construction of everything, my point still carries. Humans in any community emit a stream of behaviors in face, voice, hands, posture, stance, and so on. Maybe those bits are wholly constructed socially, or maybe universal proclivities play a role too. In any case, what the actor does, I posit, is survey the range of such behavioral possibilities for the role she is to play. She then does two other things.

First, she selects only a few. Any performance depends on picking a few behavioral bits to carry expressive impact.

Second, at any given moment, the selected features are emphasized, even exaggerated. The actor bears down on the selected behavioral bit, dwelling on it. The clumsy, sometimes contradictory flow of real-life behavior gets simplified and streamlined for easy uptake.

For example, certain body parts may dominate the impression. If we’re to watch the hands, the face can be fairly neutral.

Correspondingly, in cinema the shot can be scaled to stress the one gesture—in this case, a pat of comradeship.

If we’re to watch the face, keep the hands and body still. Film technique can help you by recruiting our old friend the facial view. I talk about several examples in Brute Force, of which this is one of my favorites—two frontal faces, blatantly unrealistic but riveting (as Eisenstein knew; see below).

Only the eyes move, and one mouth, barely.

Or, if we’re to watch an eye-flick, keep the face neutral.

Indeed, you can argue that the development of the intensified continuity style, which concentrates on facial close-ups, gave the actors less to do with their hands and bodies than did the greater range of shot scales available to studio cinema from the 1910s to the 1960s.

To smack us with a bigger impact, the filmmakers add up the channels. In this scene of Brute Force, the commissioner takes control of the prison from the warden, and the two men’s facial expressions—determination on one, fear on the other—are amplified by their paired gestures of wrestling for the loudspeaker.

The effort shows not only in their postures and fingers but their faces.

At high points, we can go for all-over acting, face and gesture and bearing and voice, as when the snitch faces his fate in the machine shop.

But note that even here, as an ensemble element, other factors are neutralized. The attackers are seen from the rear and poised or moving stiffly and inexorably. Similarly, the pure animal outburst of Lancaster’s performance at the climax depends on several factors of expressive movement swept together.

Wounded, he lets his boiling rage explode; even the frame can’t contain him. But even here there’s selection and emphasis. The head and voice and straining neck do all the work, while the arms remain taut.

The tools I survey are simple ones: eye areas (not so much the eyes as the lids and brows), mouth, tilt of the chin; bearing and stance; hand gestures; and rhythm of walking. In the Observations installment, I look at how the performances in Brute Force play off against one another, and I sum up the resources in Lancaster’s fierce performance, using all of the tools he had. That wedge of a back. Those mitts. Those slightly shifting eyes.

For preparing the Criterion Channel installment, thanks as usual to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Peter Becker, and all their colleagues.

The theatrical tradition is discussed by Alma Law and Mel Gordon in Meyerhold, Eisenstein, and Biomechanics (new ed., McFarland, 2012). On Kuleshov, see Kuleshov on Film, ed. Ron Levaco (University of California Press, 1974), pp. 99-115. I discuss Eisenstein’s approach to these problems, what he called mise en geste, in The Cinema of Eisenstein, pp. 144-160.

On actors’ use of eyes, go here; on hands, try this. I’ve discussed Lancaster’s skills before, here. More generally, when it comes to pictorial representation I defend a moderate constructivism against pure relativism here.

Ivan the Terrible Part II (1958).

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD comes to Astoria

DB here:

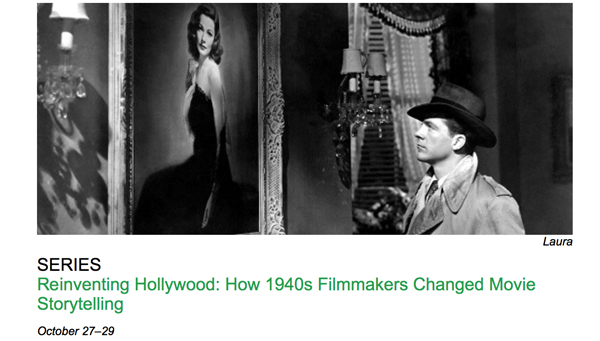

Next weekend Astoria’s wonderful Museum of the Moving Image is sponsoring a series of films keyed to my book Reinventing Hollywood. The program consists of Laura on Friday, A Letter to Three Wives and Unfaithfully Yours on Saturday, and Our Town and Portrait of Jennie on Sunday. Here’s the schedule.

I’ll be giving a talk before Three Wives and will hang around for conversation and book-signing afterward. If you’re in the vicinity, why not come by? Note: Four of the five screenings command 35mm prints! If you’ve only seen Our Town in the horrendous public-domain video versions, you’re in for a treat, because it looks (and sounds) superb in 35. Then again, there’s that tidal-wave ending to Portrait of Jennie, a force of nature on the big screen.

Looking better than when he made it?

Beyond Glory (1948). Production still.

Actually, this entire clutch of classics is pretty fair sampling of the audacity of the period, an age when narrative delirium was welcomed. Of course a lot of A pictures were stodgy, but there were an unusual number of both popular hits and less-successful items that are engagingly experimental.

The book, as Tony Rayns remarked in his Sight & Sound review, ventures beyond the classics. I cover all the films in the MoMI program, but a lot of space is devoted to minor movies too, a fair number of B films and plenty of “nervous A’s.” Those nervous A’s–films trying to get by on less-known stars, unfamiliar source material, or just a strange premise–provided me with lots of examples.

A friend who likes Reinventing Hollywood said that it was too bad I had to spend so much time on obscure and second-rate movies. It’s true that in viewing I slogged through quite a few dogs. Most weren’t illuminating, but some were, and I slid them into the manuscript, even if the reader was unlikely to have heard of them.

But two factors pop up here. First, I wanted to show just how pervasive the newly popular storytelling techniques were. That meant considering items outside the canon. When you think of complicated flashback films, you don’t think of Beyond Glory (1948) and Backfire (1949), though they may be the most intricate time-shuffling movies of the period. If you arrange the past-time events in the order we see them, Beyond Glory gives us 10-9-8-1-4-3-5-6-7-2. In Backfire, the order of presentation is 3-5-2-4-1-6-7.

These show a very 40s development: By then, such time schemes were becoming commonplace. Moreover, the fact that these two films come at the end of the decade is itself of interest. Was there a kind of arms race to tell stories in ever more elaborate ways?

Looking at the less-known items can also yield a sense of the limits of innovation. Sometimes these movies went too far. One critic noted of Beyond Glory that it “moved slowly and confusingly through a great many flashbacks.” As for Backfire, even the director Vincent Sherman had qualms:

That picture had an involved story, with flashback-within-flashback, and I hated it. The interesting thing is that not long ago I saw the film, and it looked better than when I made it.

Sherman’s last remark is indeed interesting. Today, after the really fragmentary flashback constructions we find in films from the 1990s onward, films like these (and The Locket and Passage to Marseille) don’t look as ornery. Any day now you may hear from a Tarantino fan that Backfire is a masterpiece.

More broadly there’s an issue of method, and it’s controversial. I suspended matters of quality to an unusual degree. Of course the book talks a lot about bona fide classics. I praise films by Preminger, Ford, Hitchcock, Welles, Mankiewicz, Sturges, et al. But I stubbornly persist in believing that we can best understand their accomplishments in the context of the broader burst of storytelling strategies that swept through the 1940s.

True, great writers and directors provided some of the energy for that burst, but they didn’t work alone. I think, for instance, we appreciate It’s a Wonderful Life better if we know about conventions of voice-over narration, angelic intervention, and flashback construction that had already crystallized when Capra and his screenwriters gave them a new spin.

A lot of researchers suspend questions of value in order to bring to light other factors. Scholars studying gender, race, and ethnicity consider films of all levels of quality representing women or African Americans or Jewish culture. Students of genre often find that lesser-known Westerns or musicals shed light on certain conventions. Even failures can be instructive.

Reinventing Hollywood pursues a similar method but on an area of creativity less commonly considered: narrative. The book tries to trace both common and offbeat strategies of plot construction and narration–at a period when innovation in those domains was rewarded. In some instances, we get striking innovations more or less by accident.

In sum, I was more interested in reconstructing the major and minor storytelling options of the period than in picking out masterpieces. Going into the kitchen to watch the menu being devised, you might say, rather than savoring a few consummate meals. That meant bulk viewing, which yielded a bulky book (but a good bargain at the price).

Some day it would be fun to mount a series of intriguing second-tier items I ran into. They’ll never be classics, but they do shed light on my research questions. Apart from completists, there are fans who would enjoy seeing things that are elusive on video and never make it to repertory screens or archive retrospectives. The problem then, as for me, was finding prints….

Thanks to David Schwartz and his colleagues for arranging this event at MoMI.

Backfire (1949).