Archive for the '3D' Category

Reporting from the Wisconsin Film Festival 2019

Hotel by the River (2018).

Kristin here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival is all too rapidly approaching its end, so it’s time for a summary of some of the highlights so far.

New films from around the world

We have not quite managed to catch up with all the recent films by Korean director Hong Sang-soo, but we took a step closer with Hotel by the River. It’s an impressive film, in part by virtue of its setting. The Hotel Heimat stands beside a river which is covered in ice and snow. Even the further shore with its mountains, is reduced to shades of light gray in the misty, cold light. All of this is enhanced by the black-and-white cinematography that creates a background against which the characters and the small trees create simple, austere compositions.

The story involves an aging poet who somehow senses that he is going to die soon and settles in at the hotel to wait for death. His two sons, one a well-known art-film director with a creative block and the other secretly divorced, come to visit. A young woman who has recently broken up with her married lover is visited by a sympathetic character who may be her sister, cousin, or friend. They encounter the poet by the river, and he compliments them effusively for adding to the beauty of the scene. Conversations about life ensue. The women take naps, the men bicker. Sang-soo’s typical parallels and repetitions unfold. It’s a lovely film.

Yomeddine, an Egyptian film, created something of a stir last year when it was shown in competition at Cannes. It was a surprising choice, given that it is writer-director A. B. Shawky’s first feature.

It’s also a modest, low-budget film, and like so many such films made in countries with limited production, it’s a road movie. No need to build sets or use complex lighting. The two central characters are Beshay, dropped off as a small child at a leper colony by his father, and Obama, a young orphan who knows nothing of his birth parents. Coincidentally, they both come from Qena, a city north of Luxor on the great Qena Bend of the Nile. Longing for links to their origins, the two set out there. At first they ride in the donkey cart that Beshay uses in his work as a garbage-picker, but later, when the donkey dies, they travel on foot and occasionally by train, riding without benefit of tickets.

There’s no indication where the orphanage and leper colony are and thus how long a trek the two face. I’m pretty familiar with the Nile, but they follow the large canals and train tracks that run parallel to the river on both banks. The villages along their route look pretty much alike. Shortly into the trip, however, Shawky suddenly confronts us with the Meidum pyramid (above), which acts as a handy landmark to reveal that the pair have a long way to go. It’s Shawky’s only display of an ancient site. Beshay and Obama have no idea what it is, but they explore it and spend the night in its small chapel.

Yomeddine is a likeable film blending humor, pathos, and a little suspense as it follows the pair on their quest. It’s also a plea for tolerance. Beshay’s deformities scare off those who wrongly think that leprosy is contagious (with treatment it is not), and Obama is denigrated by his classmates as “the Nubian,” for his relatively dark skin. Their sometimes prickly odd-couple friendship is a demonstration of how people of various backgrounds, including those on the margins of society, can get along. That, I suspect, is what led Cannes programmers to include it in the competition.

Overall it’s a well-made, entertaining film, perhaps an indication that we shall see more from Beshay on the festival circuit in the future.

[April 19: Yomeddine won the Audience Favorite Narrative Feature at the Wisconsin Film Festival.]

Ralph and Venellope Back in 3D

Phil Johnston with Ben Reiser, Senior Programmer, Wisconsin Film Festival.

UW–Madison grad Phil Johnston was a key participant in the festival. Not only did he program one of his favorites, Ozu’s Good Morning (1959), but he also visited a class and ran a public event around Wreck-It Ralph 2: Ralph Breaks the Internet. Phil was a writer on both entries and co-director on the second, while also providing screenplays for Zootopia (2016) and Cedar Rapids (2011). We’re very proud of him, and we were happy to welcome him back home.

I love both the Wreck-It Ralph films, but I don’t like to go to hit movies early in their runs. We usually wait a few weeks till the crowds die down. As I recently pointed out, though, that means risking no longer having the option of seeing a 3D film in that format. So it happened with both Ralph Breaks the Internet and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

Fortunately for us, the UW Cinematheque added permanent 3D capacity to its projection options, so Ralph 2 was shown in that format. The 3D much enhances the sense of being surrounded by the myriad “websites” in the scenes showing general views of “the internet,” as well as by the vehicles and netizens that flash past in their travels.

Both Ralph films display a non-stop inventiveness, and I agree with Peter Debruge’s comment that Wreck-It-Ralph “ranks among the studio’s very best toons.” The sequel is, if anything, even better. The scene in which Venellope von Schweetz confronts the full panoply of Disney princesses and tries to prove herself one of them became a classic before the film was even released.

The notion of Venellope moving from the sickly sweet “Sugar Rush” arcade game to the wildly dangerous online “Slaughter Race” (see bottom) is a great concept to begin with, and her rendition of her “Disney princess” song, “A Place Called Slaughter Race” is hilarious. The film was robbed, in my opinion, when her song didn’t get nominated for a Oscar.

The film has jokes to burn, as in the clever puns on the signs that flash in the internet and game scenes. I look forward to being able to freeze-frame the images to catch the many I missed. Unfortunately the Blu-ray release will not be in 3D. Disney has been phasing out releasing its 3D films in that format ever since Frozen, but you could for a time order such discs from abroad. (Other studios are following suit, and our 3D copy of Into the Spider-Verse is wending its way from Italy as I type.) I am told that the only 3D Ralph will be the Japanese version, at something like $80. Fortunately, it looks great in 2D as well, but I’m glad to have seen it on the big screen in 3D once.

So old they’re new again

Jivaro (1954).

Recent restorations have become a increasingly important component of our festival’s wide variety of offerings. Selections from the previous year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna are now regularly programmed, and we had visiting curators presenting their new projects. (For a brief rundown of the Bologna offerings this year, see here.)

Another film taking advantage of the Cinematheque’s new 3D capacity was Jivaro, a jungle-adventure film of the type more popular in the 1950s and 1960s than it is now. Having seen a such films when growing up, I can say that Jivaro is better than many of its type.

It was made late in the brief early 1950s vogue for 3D, so late in fact that the studio decided to release it only in 2D. One attraction of its screening at the WFF was the fact that it was screening publicly for the first time ever in its intended format. Bob Furmanek, 3D devotee and expert, introduced the film and took questions afterward; he has been a driving force in the restoration of this and many other 3D films. (His immensely valuable site is here.) Below Bob shows one of the polarizing filters used in projection booths.

The film was highly enjoyable, partly for the 3D (shrunken heads thrust into the lens and spears coming at us!) and partly for the comfortable familiarity of its genre tropes. There’s the genial South American trader who has gained the respect of the locals, the seemingly deluded adventurer with a map to a lost treasure who turns out to be right, the gorgeous woman who shows up dressed in tight blouse, skirt, and high heels, the beautiful local girl in hopeless love with a white man, and so on. (The beautiful girl was an early role for Rita Moreno, who labored as an all-purpose-ethnic bit player for years before West Side Story made her a star.) Leads Fernando Lamas and Rhonda Fleming supply beefcake and cheesecake, respectively, at regular intervals. Lamas (as you can see above) barely buttoned his shirt across the whole film. It’s hot in jungles.

For those with 3D TVs, Jivaro is already out on Blu-ray.

The Museum of Modern Art has followed up its restoration of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) with one of Forbidden Paradise (1924). Both were shown at this year’s festival. We saw Rosita at the 2017 Venice International Film Festival and wrote about it then. In preparing my book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (2005; available free as a PDF here), I saw an incomplete copy of one preserved in the Czech film archive–a key element in constructing this new version. Naturally I was eager to see the new scenes and much-improved visual quality of the MOMA restoration. Archivist Katie Trainor was present to explain the process, which yielded a version that is about 90% the length of the original.

Of all Lubitsch’s Hollywood films, this is the one that most looks back to his German features of the late 1910s and early 1920s. For one thing, his frequent star of that period, Pola Negri, was by now in Hollywood and worked here with him again here, their sole Hollywood collaboration. She stars in a highly fanciful tale of Catherine the Great, and the quasi-Expressionistic sets present an appropriate version of historical style. The set in the frame above (taken from a 35mm print, not the restored version) is my favorite, with its lugubrious creatures crouched atop the wall. Grotesque sphinxes? (The designer might have been thinking of the the two beautiful granite sphinxes of Amenhotep III that sit to this day by the Neva River in front of the Academy of Arts, though they were brought to Russia decades after Catherine’s reign.) Or just elaborate gargoyles?

The plot centers around a brief affair between a young officer (Rod La Rocque) and the licentious Catherine. A brief attempt at revolution flares up. All this is deftly dealt with by the Lord Chamberlain, played by Adolf Menjou, hamming it up with eye-rolls and knowing chuckles.

It’s not first-rate Lubitsch, largely lacking the lightness that one associates with the director, and which he had already achieved in his second Hollywood film, The Marriage Circle (1924). But it’s a pleasant entertainment, and the set and costume designs are visually engaging–especially in this excellent new restoration.

David watched None Shall Escape (1944) for his book on 1940s Hollywood, but I was unfamiliar with it until its restored version was shown here as one of the Il Cinema Ritrovato contributions. The film was originally made by Columbia and was presented at our fest in a 4K restoration from Sony Pictures Entertainment, the parent company of Columbia. Rita Belda, SPE’s Vice President of asset management, was here to explain the complicated process. She summarizes it here as well.

The film had been carefully preserved, probably because of its historical importance as a unique fictional depiction of Nazi atrocities. The original negative and three preservation positives survived. These had the usual scratches and tears, as evidenced in the first comparison image above. A significant challenge, however, was that the prints had all been lacquered in a misguided attempt to preserve them. The result was staining throughout, evident in both comparison images. Digital removal allowed for a stunningly clear image throughout the finished version.

None Shall Escape is notable as the only Hollywood film made during the war to depict major aspects of the Holocaust. It begins with a frame story set in the future. This postwar trial of Nazi criminals remarkably prefigures the Nuremberg trials. Testimony is given against a single officer, who stands in for all the accused officers and collaborators. Wilhelm Grimm begins as a schoolteacher in a small Polish city but proves so devoted to the Nazi cause that he rapidly rises through the ranks. After the city is seized during the German invasion, Grimm comes to rule the city. At the trial, townsfolk who had resisted and suffered under his domination testify, and their stories unfold as a series of lengthy flashbacks.

The film is an effective and moving drama, not least because it demonstrates the explicitness with which it was possible to depict Naziism in this period. It shows, as Hitler’s Children (1943) did, the insidious indoctrination of young people by the Nazi party. But no other film depicted the rounding up of Jews and their dispatch to concentrations camps–named as such.

Director André De Toth, though not a top auteur, again proves the value of sheer skill and artistry in filmmaking, a value that David recently discussed in relation to Michael Curtiz. None Shall Escape is an impressive example of the power of the classical Hollywood system–and a beautiful film, as one might expect from cinematographer Lee Garmes. Marsha Hunt gives a moving performance as Marja, another schoolteacher who fearlessly persists in opposing Grimm and his oppression of the townspeople; it is a pity that she never achieved the stardom that she merited.

Perhaps most notably, De Toth stages a powerful scene in which Jews rebel against being packed into trains and are ruthlessly mowed down by their captors. It must have given many Americans a first glimpse of what would soon be revealed by newsreels and personal testimony.

Now, back to the movies. More festival coverage to come, when we get time to write!

For more on early 3D, see David’s entry on Dial M for Murder.

Ralph Breaks the Internet (2018).

The movie experience as format: A 3D state of the union

Kristin here:

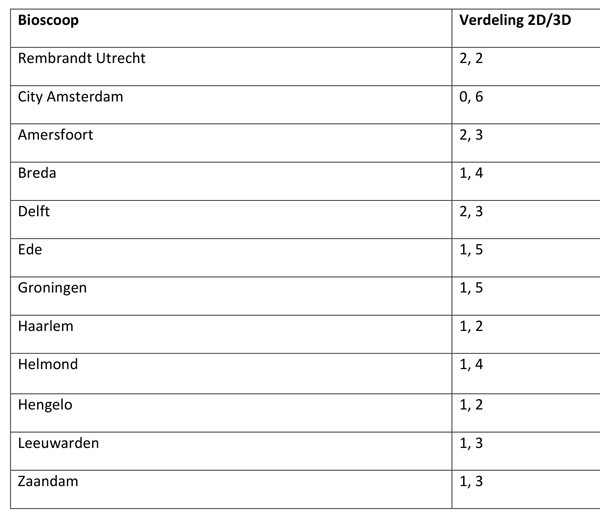

On February 13, the day after I posted my blog entry, “3D in 2019: Real Dvided?,” I received an email message from Belgian film critic David Vanden Bossche. He had been intrigued enough by my post to investigate the number of 3D screenings on offer in Belgian cinema chains in comparison with “standard” or “premium” 2D screenings. I had found 3D screenings the distinct minority in our local Madison theatres, even early in films’ runs. David found the opposite in Belgium

To extend his investigation, David enlisted his colleague Tim Bouwhuis to analyze the proportions of 3D screenings in the Netherlands.

David and Tim’s resulting online article, “Filmbeleving als Format: A 3D State of the Union,” was posted on March 13 on Enola.be, a film and music site in Flemish. David kindly offered to send me an English translation of the piece. It turned out to be quite intriguing, since 3D in Belgium and the Netherlands is considerably more robust than in the US. I mentioned in my post that areas of the world outside North America have a higher proportion of 3D-equipped screens than we do here. The attention usually focuses on the Chinese market’s enthusiasm for 3D. This enthusiasm is often credited with encouraging Hollywood studios to keep making 3D films despite their waning popularity in North America. But other countries favor 3D as well, and it’s valuable to have an examination of a pair of small European markets.

Our thanks to David and Tim for allowing us to present their article here as a guest post.

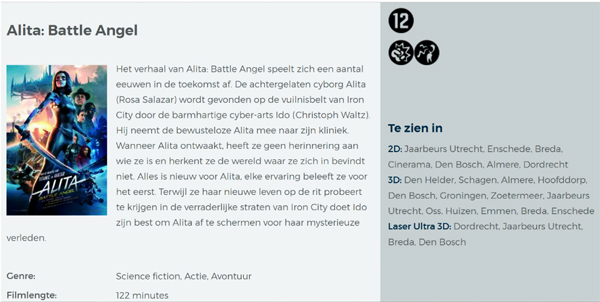

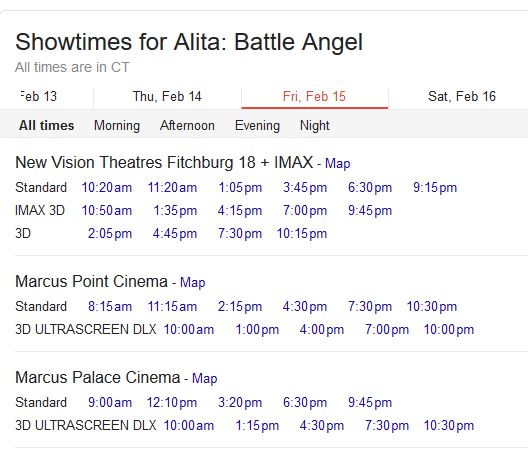

On 12 February, following the American premiere of Alita: Battle Angel, Kristin Thompson posted a new entry, 3D in 2019: Real Dvided? Thompson investigated the state of 3D within the contemporary theatrical environment in the United States. Her conclusion was crystal clear: 3D’s share within American movie screenings has steadily declined in the last decade, when Avatar urged most theatre chains to make the switch to 3D projection. The numbers Thompson presents abundantly show that American multiplexes are less and less inclined to include large numbers of 3D screenings in their programs, and that 3D is losing ground to another ‘premium’ format such as IMAX.

Those findings were intriguing enough suggest a closer look into the Belgian situation. Because that is ultimately a small market, I contacted fellow film critic Tim Bouwhuis, who lives in the Netherlands and could thus provide some information on the particular situation in his home country. Our research allowed us to collect an acceptable amount of material and provide us with numbers that paint a rather different picture than the one to be found in Thompson’s piece. The data we collected show a different evolution for 3D in these two countries and possibly in the whole of Europe. Further research could shed some light on this. Even a limited study, however, offers some possible explanations for these differences. This entry will tackle some of them.

United States: RealDvided

Before dealing with the situation in Belgium and the Netherlands, it is probably a good idea to summarize what Thompson presents in her piece.

Starting with screenings in her hometown Madison, Wisconsin, she observes that 3D’s share in the number of screenings of recent blockbusters is surprisingly limited. Thompson broadens the scope with additional numbers from other cities, concluding that this is definitely not a local issue.

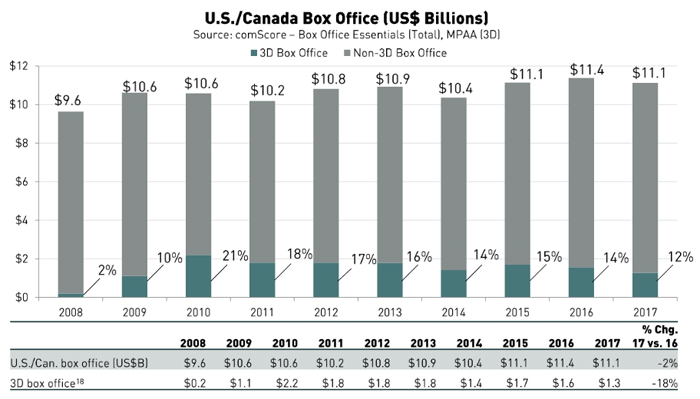

The growth in 3D emerges with the success of Avatar and the consequent peak in 3D earnings in 2010. Since then, 3D’s share of film grosses has been in decline. Production of 3D television sets – a prime feature in store windows just a few years ago – has all but halted. Even if one should exercise some prudence in declaring the death of 3D in a theatrical environment, it is safe to state that its intrusion into the living room has failed spectacularly.

It is remarkable that other ‘premium formats’ (Thompson refers to these as PLF – Premium Large Formats,’ a term we will stick with here) such as IMAX or various “ultra” and “grand” large-screen auditoriums (usually offering extra comfort and superior sound) are gaining in popularity, while 3D is on the decline. That means the public is willing to pay extra for a ‘premium’ – PLF upcharges are as high or higher than those of 3D – and apparently often prefers to pay for PLF rather than for 3D. This process obviously suits the theatres’ economic agenda: a large part of the extra income returns to the distributor and – as Thompson points out – there’s also the extra cost for 3D glasses. The upcharges may also make the visitor less inclined to spend money on food & beverages, a vital source of income for theatres. That means the final balance might be rather negative from the theatre’s point of view in the case of 3D revenues. The fact that PLF’s may net a larger profit thus adds another extra factor working against 3D.

One might expect that in case of Alita the figures would be rather different. The film is produced by James Cameron, one of 3D’s most prolific advocates and arguably one of the few directors – along with Ang Lee, Martin Scorsese, Werner Herzog, Gan Bi and (even) Jean Luc-Godard–who actually tried to explore the true potential of 3D’s formal cinematic language.

The numbers Thompson presents, however, show that even an “event” film such as Alita does not always encourage US theatre owners to schedule more 3D screenings. Thompson points out that there might also be a more practical issue at work here: the clarity of the image is one of the more troublesome issues 3D faces. To solve this, Cameron and Roberto Rodriguez (who took the directing honors when it turned out Cameron was too busy preparing the Avatar sequels) made sure the DCP’s (digital cinema package, used to send movies to theatres since the disappearance of film stock) came with a set of guidelines. These technical complexities, combined with pricey investments and low returns, make for a cocktail that encourages theatres to drastically cut back on the number of 3D screenings.

Belgium: The Kinepolis experience

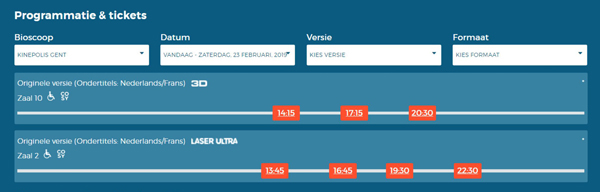

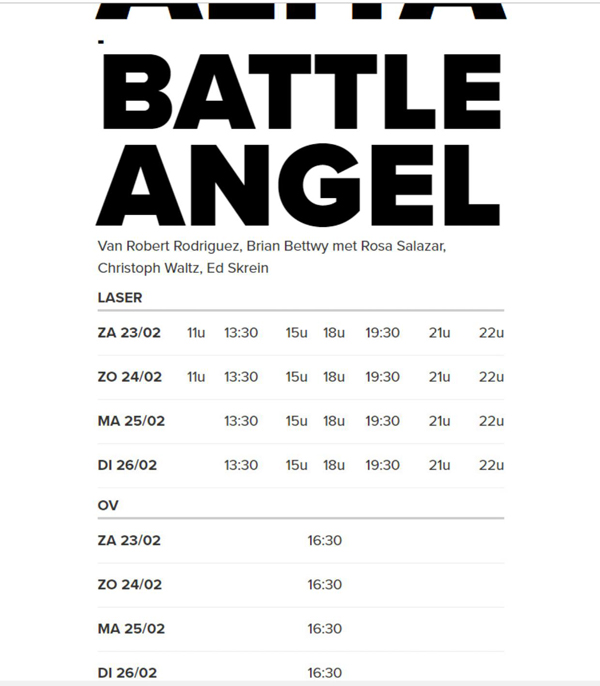

Intrigued by Kristin Thompson’s article, I gathered comparable statistics for Alita in Belgium. See the top image for an ad listing the formats available during the first week of release at Kinepolis Group theatres in Belgium.

That’s a lot of 3D ! No fewer than four of these six formats integrate 3D into the theatrical experience. Obviously, a film such as Alita is likely to receive such a treatment and definitely during its first week. It is also necessary to look – as Kristin Thompson did – at the relative percentage of 3D versus “standard” 2D screenings. A ten day interval seemed ideal to reassess the situation. Here are schedules for two Kinepolis theatres ten days after the film’s opening.

As it turns out – depending on the Kinepolis theatre one chooses to visit – 3D still makes up between 42 and 67 percent of Alita’s daily screenings. The highest number is reserved for Kinepolis Brussels, with the theatre being the only one equipped with a full-fledged IMAX screen. IMAX as a PLF in Belgium is used exclusively for 3D screenings, save for some very rare exceptions.

As pointed out already, Alita can be regarded as an exceptional production that integrates 3D as part of its raîson d’être and its promotion. Alita’s figures might be exceptional, so looking at a comparable title might be necessary. The Lego Movie 2 made its debut about three weeks later, is also shown in 3D and thus makes for a perfect comparison.

3D’s share is smaller here, but still 40 percent of the screenings are in the 3D format, a number well above the American averages.

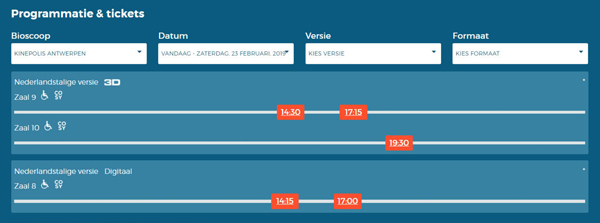

Because two titles might still represent a distorted sample, we contacted Kinepolis Group Belgium and asked them to provide us with some material that would allow to have a better general idea about the significance of 3D within their total number of screenings and their profits and the way this share has evolved (or is evolving).

These numbers are clear enough to allow some conclusions. Both in 2017 and 2018, 4 out of 5 of the most popular films for Kinepolis Belgium were 3D movies. 2018’s numbers even show that both the relative share and the absolute numbers (and thus the weight of the top 5 and 3D) are indeed increasing. Obviously that does not mean that every paying visitor opted for 3D (or one of the various combinations of 3D and PLF), but as the general share of 3D screenings for every movie released in this format at Kinepolis theatres in Belgium is situated anywhere between 40 and 60 percent of the total number of screenings. That means this percentage can be applied to these numbers.

The Kinepolis representative pointed out that the percentage of 3D screenings for a movie is determined on the basis of the quality of the 3D imagery and the way the 3D format enhances the viewing experience. Alita is perceived to be a prime candidate for these arguments and thus the number for 3D screenings is very high and at the lower end for The Lego Movie 2. Even if one sticks to the lower end of the scale, however, the importance of 3D screenings within the total number of screenings is still remarkable.

Beyond Kinepolis

All those results lead to a single clear picture: unlike the American situation, 3D is still positions itself as the preferred “premium format” in Belgium. Its impact on the total number of screenings (in Kinepolis theatres) is still very significant and shows no signs of diminishing.

I believe there are a few elements at play to create this situation. One of the first emerges when we take a look at the Alita screenings outside of Kinepolis theatres. Another large chain of theatres, UGC, provides a useful comparison. (Most independent movie houses have not screened Alita). The schedule immediately below is for a UGC cinema in Antwerp, and below that, one in Brussels.

In Antwerp there is not a single 3D screening to be found; in UGC Brussels, there’s just one, while the same day lists 8 standard screenings. The discrepancy between these numbers and the ones at Kinepolis are easily explained: UGC has a very limited number of 3D screens.

Slowly it becomes clear that the very specific situation of the Belgian movie theatre environment is an important factor in all of this.

Kinepolis Group was formed through the joining of two large family companies, the Claeys & Bert Groups. At the start of the 19080s, they began setting up a chain of theatres that no longer consisted of the smaller movie theatres Belgium had known up to that point. Their theatres introduced multiplex to the country. “Decascoop” in Ghent (first 10 screens, with two added later) and the other early Kinepolis theatres benefited from the rise in ticket sales in the early eighties and consolidated their position by being the only theatres around the country able to show box-office hits such as E.T., The Extra-Terrestrial and the “Indiana Jones” trilogy, on multiple screens. 1988 saw the inauguration of Kinepolis Brussels – at that time one of the largest theatres in Europe – along with the first IMAX screen in the country (and most neighbouring countries).

At that time though, IMAX was a used only to screen spectacular documentary films that offered the sensation of flying through the Grand Canyon, diving into the ocean or being in outer space. Production of these films was rather limited. When the audience started to lose interest, Kinepolis halted its programming in 2005, just when the US market was taking its first steps towards IMAX screenings of regular releases. Christopher Nolan’s films were instrumental in the process that eventually turned IMAX into a popular “premium format.”

More or less simultaneously 3D resurfaced. The format enjoyed some popularity during the fifties (Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder comes to mind) and returned in the early eighties, blessing film history with a few horrendous films as Jaws 3D and Friday The Thirteenth – Part III 3D. The more recent revival of 3D gained impetus with the releases of animated films, notably The Polar Express (2004) and Chicken Little (2005) and was given a boost by U23D (2008). Other animated and concert films followed, but it was Avatar, with its combination of 3D with the latest state-of-the-art special effects technology, that pushed theatre owners to convert their screens to digital projection, the necessary prerequisite for add-on 3D capability. Its huge success started an evolution that promised the full potential of the 3D cinematic language would finally be explored. When Scorsese, Lee, and Godard took up experiments, it even briefly seemed this would actually be true.

In the US, although Cameron’s smash hit dictated the rapid spread of 3D technology, the format still had to face competition from the already established IMAX format. That was not the case in Belgium or the Netherlands. Kinepolis Group – the dominant chain by now – solely promoted 3D, and this position dictated the whole theatrical environment. The IMAX screen reopened in 2016, when 3D was well established as the preferred premium format. IMAX was (and is) used almost entirely for 3D screenings.

It is necessary to include another element here: the exceptionally high projection standards at Kinepolis Group. When John McTiernan came to Brussels in 1988 to launch Die Hard, he claimed that there was probably no better projection of his film to be seen anywhere in the world. Those might have been the words of an overly enthusiastic director, but they illustrate the high technical standards within Kinepolis Group. Other theatre chains were more or less forced to follow suit.

Because quality projection became the standard, any other “premium” format faced a high hurdle when it came to distinguishing itself. “Laser Ultra” already offers an exceptional viewing experience on a very large screen, so further investment had to be justified by something beyond image quality or a larger screen. 3D offered such a distinctive element and extra added value and initially did not face any competition from PLF’s. When that changed, Kinepolis kept promoting 3D, with combinations: “Laser Ultra 3D” and “4DX,” which adds vibrations to the experience.

All of the above means that 3D’s position in the Belgian environment is very different from its position in the US. Obviously Kinepolis also needs to pay the distributors, but a new deal with RealD on the use of 3D glasses consolidates Kinepolis’ position and intensifies their efforts to promote 3D. All of this means that the format will remain popular in Belgium. In this way, Kinepolis Group’s market position also dictates 3D’s standing as the preferred “premium” format in Belgium.

The Netherlands: Experiences & attractions

The Kinepolis Group is also a dominant factor in the Netherlands, which makes comparing the situation in both countries an interesting endeavour. The Netherlands’ theatrical environment has two major chains, Pathé and Kinepolis, both of them part of larger European concerns. Pathé is part of the French group ‘Les Cinémas Gaumont Pathé’ – a company that has its roots in the early days of cinema. Pathé owns 28 theatres, spread out over 20 Dutch cities. Kinepolis is a branch of the Belgian company and owns 17 theatres in the Netherlands.

With 21 theatres, “Vue Nederland” also deserves to be mentioned, although their total seating capacity is rather limited and has its main focus on smaller provincial towns.

The rise of new technologies, PLFs and “extra” movie attractions such as 4DX, has lead to a situation in which standard screenings have become something of a curiosity in the multiplexes of most major cities. Almost every theatre in a major city boasts 3D, Dolby Atmos or another premium feature. Developments in sound and imagery are promoted: Pathé even distinguishes between Dolby Atmos and Dolby Cinema, with the first emphasizing immersive sound.

Six IMAX screens are spread throughout the country, although most of them would not stand up to a purist’s scrutiny: the largest one – Pathé Arnhem – measures 21×12 metres, whereas a standard IMAX screen is supposed to be at least 22x16m. The Dutch IMAX venues pale in comparison to Brussels’ enormous 27.6 x 19.3 screen.

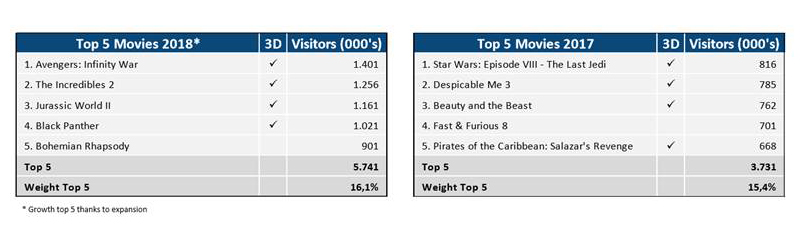

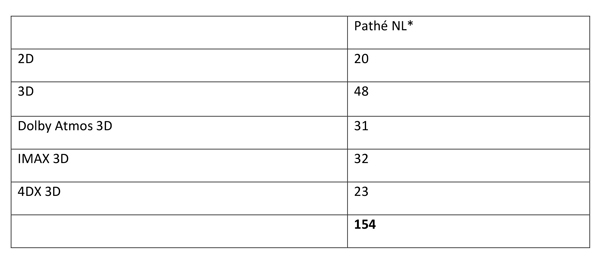

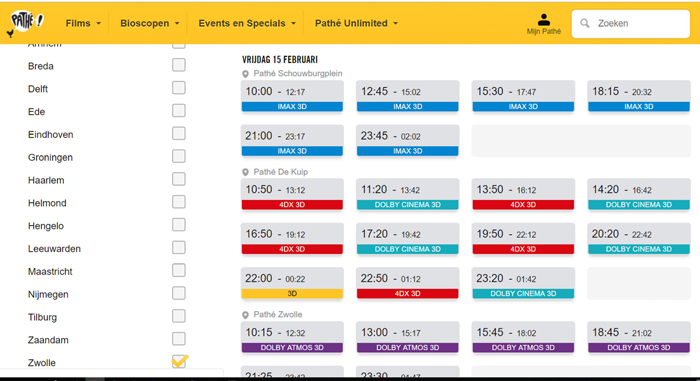

This variety of screens, systems, and venues makes it difficult to get a good grip on the partition of different formats, so once again we turned to specific Alita screenings available on February 2, 2019 :

At first glance, standard 2D and 3D screenings are balanced by premium screenings. That perception changes, when we take into account that only 5 out of 25 theatres feature 4DX, 5 offer Dolby Atmos 3D and 6 offer IMAX. That means that in some theatres it has become all but impossible to see a standard 2D screening.

The most important factor here is the fact that theatres that offer 4DX/Dolby Atmos 3D/IMAX, focus almost entirely on these formats. Those theatres are usually situated in larger cities, thus rendering it almost impossible to see a standard screening there. Amsterdam/Rotterdam (see above and below) are prime examples: out of 44 combined screenings only three of them are standard screenings. In Scheveningen, Maatsricht or Eindhoven there are no standard screenings to be found at all on the same day.

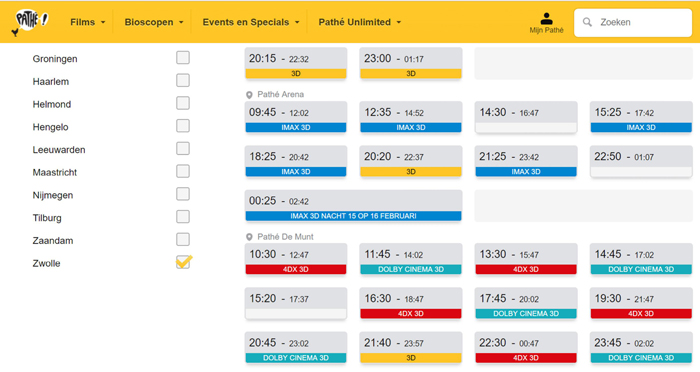

Most theatres are still located in smaller cities, and a general overview would thus suggest a rather balanced field of standard and 3D screenings. But even in those smaller venues – that do not offer the extra attractions 4DX, Dolby Atmos 3D or IMAX, the 3D screenings still outnumber standard screenings (see below)

3D vs 2D in theatres without 4DX, Dolby Atmos and/orIMAX as of February 15, 2019:

With 1 out of 3/3/4 , it is clear that 3D screenings are dominant in Pathé theatres. Even daytime screenings on weekdays are 3D, which relegates standard 2D screenings to the position of a rarity.

Kinepolis’ available number of formats in the Netherlands is more limited than in Belgium. Neither IMAX nor 4DX is an option here. For Alita that results in:

The Vue chain competes with Kinepolis and Pathé in offering DX theatres that combine Dolby Atmos with superior projection technology. As in Belgium, the dominant chain sets the technical standard. A select number of theatres offers D-Box chairs that move with the action on screen. The American film critic Jeffrey Wells describes D-Box chairs as “4 DX’s less dynamic cousin.” (D-Box is Canadian in origin, while 4DX is South Korean).

Pathé, Vue and Kinepolis promote their different PLFs in exactly the same way, using “experience” and “immersion” as unique selling propositions. With 4DX the movements and effects start competing with the images for the viewer’s attention, returning the cinematic experience in a ironic way to its attraction-based origins when it was something to be experienced at fairgrounds and other shows.

In sum, the Dutch theatrical environment resembles the Belgian. A high technical standard has become the zero-line for movie screenings and 3D has penetrated the market to such an extent that it is no longer perceived as being a “premium” format, which leads to a set of various attraction-based formats that try to justify the extra cost.

At this point Dolby Atmos, Imax, and 4DX are still perceived as novelties, but it is likely that exhibitors will need additional attractions in years to come. Rising admissions for PLFs and anything “premium” suggest that visitors are constantly looking for more immersive experiences (according to the “Dutch Foundation for Film Research” in their 2018 yearly review). The number of available PLFs has significantly risen in the last few years and as long as the dominant chains continue to invest in these formats, others will follow suit. Kinepolis and Pathé set the standard, competing chains adapt.

Whether or not the public is actually asking for these technologies remains a topic open to discussion. One could claim the public merely adapts to the industries’ innovations. Still, there is no denying that PLFs turn a large profit. In Pathé Rotterdam the regular ticket price for PLF is 18 euros, while a standard screening will cost you 11 euros. Despite the cut that needs to return to the distributors, the cost for 3D glasses, and the “hardware” investments, 3D in all its forms is dominant when it comes to movie screenings in the Netherlands. The late entry of IMAX into this environment (as in Belgium and contrary to the US) meant 3D had little or no competition and consolidated its position as the preferred “premium” format.

These conclusions to come with some nuances. The Dutch part of this piece limits itself to one title and three dominant chains. Independent movie theatres were not addressed and obviously Alita: Battle Angel has some standard screenings outside of the major theatre chains. There is enough conclusive evidence, however, to support the claim that standard screenings have all but vanished in the larger cities.

A publicity image for Kinepolis, Brussels.

3D in 2019: RealDvided?

Kristin here:

From August of 2009 to April of 2012, David and I (mostly I) posted a series of entries on the spread of 3D film production and exhibition. The series kicked off with my provocatively titled, “Has 3-D already failed?”. It had a lot of background facts and figures, but the main point was to express skepticism about the extravagant claims that were being made by some in the industry who predicted that eventually most or even all films would be released in 3D. I opined that 3D would probably remain confined to certain genres, mainly animated films and big action pictures. At the time, Julie & Julia was my example of the type of film that would never be made in 3D. Today it could be Can You Ever Forgive Me?

I followed up four times during 2011, as 3D continued to spread. In January I posted “Has 3D already failed? The sequel: RealDlighted.” Hollywood was just coming off the year that 3D admissions as a percentage of total box-office peaked at 21%, to a considerable extent thanks to Toy Story 3. Of the top eleven grossers, seven were in 3D. 3D TVs had become a significant force in the electronics market that year as well, though sales were lower than predicted.

Conversion of screens overseas was also proceeding apace. That surge would eventually fuel the continued production of 3D films in the US, despite their decline in the domestic market.

Already, though, industry commentators were predicting that decline. I cite some of them and their arguments in this entry.

Our entry was followed later in January by the second part: “Has 3D already failed? The sequel: RealDsgusted.” I dealt with the backlash among audiences and critics, especially in the face of conversions of past films to 3D. Not being a fan of 3D, I pointed to the one film in that format that I looked forward to seeing: Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010). It did not disappoint, and its tour of the Chauvet cave, not open to the public, struck me at the time as an ideal use for 3D. I still think so.

In July, in “Do not forget to return your 3D glasses,” I examined the fact that 3D films’ shares of total box-office takings were falling. It wasn’t by much, only from 21% in 2010 to 18% in 2011–but there were more 3D films released that year, and a lot more theaters were equipped by that time to show them.

On August 30, I ended my series with “As the summer winds down, is 3D doing the same?”

In April, 2012, David weight in on the roles played by James Cameron and other powerful directors in pushing digital projection and 3D, in his “It’s good to be King of the World.” That entry, extended and updated, became a chapter in his e-book, Pandora’s Digital Box.

Our series got quite a bit of attention because Roger Ebert, a foe of 3D, cheerfully linked all of our entries.

As it turned out, our series appeared just after the technique had begun its slow drop in the percentage of total box-office receipts provided by 3D screenings.

Assuming the decline has continued, by 2018 that percentage might have been as low as half the high of 21% in 2010 (fueled primarily by Avatar, which was released on December 18, 2009). Will Cameron’s current big 3D project turn the tide? I’ll have a little to say on that at the end.

It has its moments

Ironically, at about the same time that our series closed, we became increasingly interested in the format. Not that we had completely rejected it to begin with. There had been some excellent animated films made by Pixar, Laika, and Disney. The occasional auteur dabbled in the format, as when Scorsese made Hugo (2011). This is a far cry, though, from believing or hoping that 3D would become universally used. Again, who would want to see If Beale Street Could Talk or Vice in 3D?

But the technology improved, and the films got better-looking. More auteurs utilized 3D. There was Cuarón’s Gravity (2013), perhaps the first film in which the 3D effects were utterly convincing. That was partly because so many shots were largely or entirely digitally created and partly because of innovative lighting technology. I still think it’s the only film I’ve seen that is dramatically better in 3D than flat. In 2016, Spielberg made the underappreciated The BFG. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Jean-Luc Godard proved that 3D technology could be simple indeed and still create a masterpiece like Adieu au langage (2014; see here and here). That and Gravity are the only films that I think really must be seen in 3D.

Older 3D films also got a new lease on life through home video. It was the 2012 release of Dial M for Murder on 3D Blu-ray that spurred us to invest in a 3D television. (David saw the screening at the Toronto International Film Festival and wrote about it.)

Interestingly, 3D televisions provide the first method which allows someone analyzing a 3D film to watch it on a personal viewer rather than needing it professionally projected on a screen. You can freeze the frame, and the 3D image hovers before you.

Unfortunately 3D lasted on television for a very short time. By 2012, DirectTV dropped it, and sports, the great hope for 3D television, failed to sustain the format as ESPN stopped showing 3D in 2013. From 2014 to 2017, the major manufacturers of 3D TVs ceased production of them. We shall simply have to nurse ours along or somehow buy a backup machine before it’s too late. Fortunately most 3D Blu-ray discs have been sold as a set with standard Blu-ray copies of the same film, so we can go on watching Moana and Kubo and the Two Strings and others once the set ceases to function. (Robert Silva offers a good rundown on the history of 3D TV, including the reasons for its failure. As he points out, home-theater video projectors with 3D capacity are still available.)

Blink and it’s gone

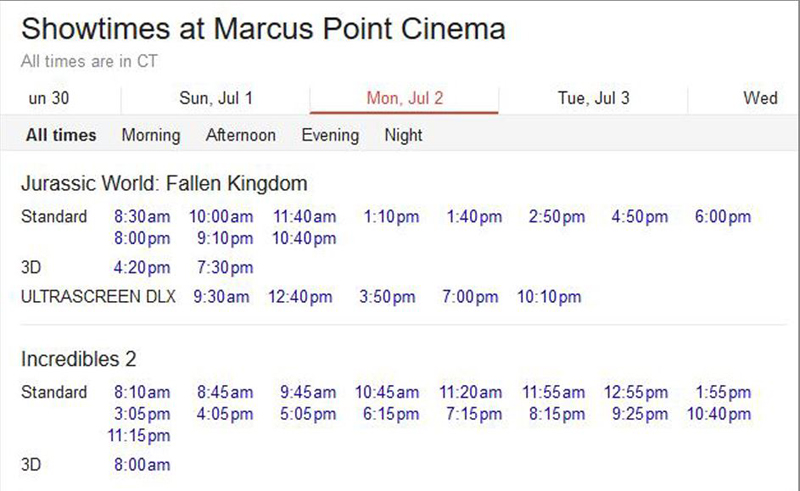

These days, it seems that unless you live in a large city, if you don’t catch a 3D screening early a film’s run, it will later only be showing flat.

I first noticed this diminution in the number of 3D screenings last summer. Incredibles 2 was showing at our local multiplex, Marcus Point Cinema, part of the Marcus chain of nearly 700 Midwestern theatres, and I wanted to see it in 3D. Checking the theater’s schedule, I was startled to discover that the 3D version was playing only once a day, at 8am. There were 17 showings in 2D. The film had opened on June 15 and thus had been out a little over two weeks.

David and I usually wait for a few weeks to see a popular film so that the crowds will die down. I expected that there would be few people at an 8 am show, so I set my alarm and set out early the next morning for Point Cinema. I purchased my ticket, and as I was moving away from the ticket desk, I heard the woman behind me purchase tickets to Incredibles 2 for herself and her two children. She bought them for the 8:10 am screening in 2D. The children were not too young to cope with 3D glasses, and the family was there early enough to attend the 8 am screening with me. Whether through a wish to save money or simply by preference, they had chosen to see the film in 2D. Indeed, I had the pleasure of a completely private screening.

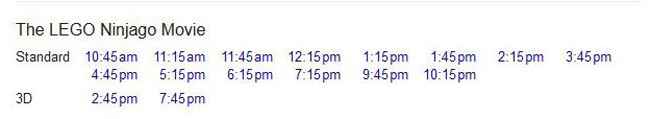

Another of 2018’s big 3D films was also playing, as the schedule above shows. Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (which I didn’t see) had two 3D screenings per day, against sixteen flat ones. It is notable that five of those were on the “Ultrascreen.” This may suggest that large-screen showings with elaborate sound systems, including IMAX, are more attractive to audiences than 3D, even when these large-screen showing also involve an upcharge. More about that later.

I wondered if this imbalance between 3D and 2D screenings was part of a larger pattern, so I have occasionally checked schedules for other 3D films. Also, might Marcus be limiting the number of 3D screenings so severely, or were other theaters doing the same? On August 1 I looked up the schedule for Mission Impossible: Fallout, showing at two local multiplexes:

Point Cinema was showing the film twice in 3D, four times flat on its Ultrascreen, and nine times “standard,” as 2D on an ordinary screen is now known. Its rival theater, New Vision Fitchburg 18 + Imax, had no 3D screenings at all; as the possessor of our only IMAX screen, it had four flat screenings and seven standard ones.

On September 17, I found this schedule for another popular animated film:

Again we see the considerable imbalance, with two 3D screenings versus fourteen in 2D.

Might this imbalance result from the fact that I was waiting a while into the run to check? I looked at Ralph Breaks the Internet for November 26, 2018, the Monday after its opening on Wednesday, November 21:

The same pattern holds even during the first week of the film’s run, in both theaters. In this case, however, the 3D screenings seem to have ended sooner than we expected. We went to Ralph on December 7, and there was no 3D showing available, so we saw it in 2D. The same ended up being the case with Spiderman: Into the Spider-Verse, which apparently had no 3D screenings after its first or second week. That’s a film we have been told would distinctly benefit from being seen in 3D, but we missed our chance. So far it’s not even clear whether the film will be released in 3D for home video.

I decided to try a similar exercise with a much larger city: Chicago. Of the theaters selling tickets on Fandango for Saturday, January 26, 375 screenings were of 2D versions, and eight of 3D films, all of the latter at AMC theaters. One of the latter is of A Beautiful Planet, an Imax documentary. Five of the 3D screenings were of Aquaman and two of Spiderman: Into the Spider-Verse.

I realize that awards season is not the ideal time of year to be looking at statistics of 3D films. Many of the films currently playing in cinemas have Oscar and other nominations, and have been held over to play only a few times a day to take advantage of that fact. On the other hand, there are some films, including Oscar nominees, that could plausibly have been made in 3D a few years ago and were not. These notably include Mary Poppins Returns, Glass, Bumblebee, and First Man. (M. Night Shyamalan has said he would never make a film in 3D, but Glass is the sort of film that another director might have made in that format.) I’ll try the same exercise during the summer movie season and see what the balance is. I’m sure there will be more 3D screenings proportionately than there are now–but probably not as many as in 3D’s heyday of 2010 to 2013.

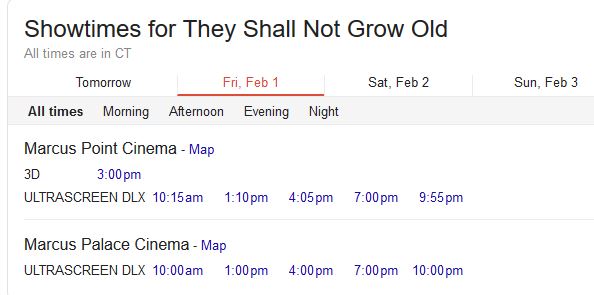

Even an event film that depends heavily on its flashy technical aspects, Peter Jackson’s restored, colorized, 3D-ized, sonorized documentary, They Shall Not Grow Old (2018), was shown here in Madison more often in 2D. It played on two days in late December. On the first day, 3D was available, but we saw it on the second and had to settle for 2D. It was brought back again recently for a short run, and we saw it again, this time at the single daily 3D matinee screening available. There were five 2D shows on the Ultrascreen.

This time Marcus’ other local multiplex didn’t show it in 3D at all.

We thought that seeing They Shall Not Grow Old in 3D was interesting and worthwhile. Still, we had thought it very effective without the 3D. The restoration, color, and sound were the most remarkable parts of Jackson’s transformation of the old footage.

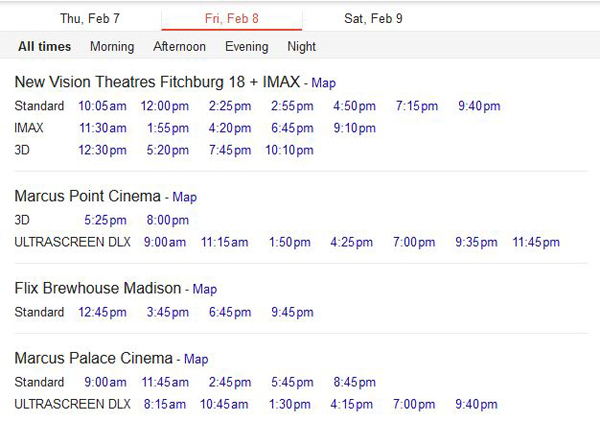

All of these schedules are for 3D films that had been running for a while. I also, however, checked the opening Friday, February 8, for The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part. (It opened Thursday, February 7, but Friday was the first day with a full schedule.)

Four theaters, including three multiplexes, were playing the film that day. There were a total of 40 screenings, 16 of them standard, 18 in IMAX or Ultrascreen DLX auditoriums, and six in 3D. None of the latter were on large-format screens. As in earlier cases, the Marcus Palace Cinema had no 3D screenings, even for the opening weekend; it does have 3D capacity. It has two Ultrascreen DLX auditoriums, which the managers seem to favor over 3D. Flix Brewhouse Madison does not have 3D facilities, but as its name implies, one can consume sandwiches, beer, and so on while viewing films.

PLF vs 3D

This reluctance on the part of theaters to devote their screens and time-slots to 3D reflects the general decline in the format. According to Variety, ever since Avatar (2009) pushed cinema owners to invest in 3D equipment (and in the case of those who hadn’t converted yet, to switch to digital projection), 3D has declined. From $2.2 billion in grosses in 2010, fueled largely by Cameron’s film, the figure had shrunk to $1.3 billion in 2017. That year only 44 films were released in 3D, dropping from 52 in 2016.

We’re all familiar with the reasons for this, which we discussed in our series linked above and which continue to be chewed over in the press. People don’t feel the upcharge is worth it. Small children can’t keep the glasses on. Some moviegoers get headaches from the glasses. The projection system and the glasses often create a dimmer image. Virtually all 3D live-action films have some shots converted to 3D in post-production. The post-production conversion process has improved, but some early shoddy post-production conversions gave people the idea that only native 3D films are worth watching.

Theater owners and managers have their own set of reasons for not wanting to show 3D. We haven’t been able to find out the range of terms distributors set for theaters renting a film. Are 3D screenings required for any film offering that option? Are there minimum numbers of screening? Must the screenings be in auditoriums of a minimum size? How long does the 3D run have to be? Still, I have gleaned a bit of information from people involved in exhibition.

One employee of a multiplex told us that a film released in a 3D format had to be given some 3D screenings at the opening week of the run. The exhibitor could then continue the 3D shows if the box-office receipts warranted it. This makes sense, as the distributor is getting a cut of the takings. Given 3D’s decline in popularity, this pretty much explains the pattern of the small numbers of screenings reflected in the schedules illustrated above.

The owner of one Midwestern small-town theater pointed out to us that the 3D upcharge in itself hurts the theaters. He declined to convert to 3D back when distributors were pushing theaters to do so. At the time, he recalls that about fifty cents of the proposed $2 upcharge went to the 3D firm and the distributor got a percentage of the remainder. Moreover, as he put it, “For a family of four that’s $8 less for vending – that’s my reasoning.” As we know, movie theaters typically depend on their customers buying expensive treats at the concession stand (and increasingly on meals, whether consumed in their theater seats or at a restaurant positioned in the lobby) to make a profit.

3D also is losing out to an attraction that moviegoers are proving more willing to pay extra for: PLF or Premium Large Format auditoriums. The most high-profile of these is IMAX, which starting out in the 1970s as a largely museum-based attraction showing its own short documentaries. It branched out into occasionally showing studio feature films, starting with Disney’s Fantasia 2000 (2000) and continuing with such event films as the last five Harry Potter installments. It was when IMAX films went from being shown on 70mm film to a digital format (introduced in 2008) that it really took off, since existing multiplexes could convert an auditorium to an IMAX venue. From 299 screens worldwide in 2007, IMAX expanded to 1302 by September, 2017. Of those, 1203 were in multiplexes.

For much of this time IMAX screenings were often in 3D. With the waning popularity of that format, however, in July, 2018, IMAX announced that it was cutting back on 3D. The success of Dunkirk in 2D IMAX was cited as proof that people would accept even a period war film not involving Americans if shown in the large format and flat. The announcement specified that IMAX screenings of the forthcoming Blade Runner 2049 would be only in 2D. The fact that Christopher Nolan had shot much of Dunkirk using an IMAX film camera became a publicity point for the film. Similarly, the fact that Cuarón shot Roma in digital large-format featured in popular coverage (the camera was an Alexa65). The irony that the film would mainly be seen on TV screens was not lost on commentators, but at least it received a limited theatrical release, including 70mm screenings. Large, sharp, flat images were winning out over 3D.

The Ultrascreen DLX mentioned above in some of the Marcus schedules is a somewhat smaller version of IMAX combined with luxurious surroundings. The chain’s website provides details.

The UltraScreen DLX® concept features three important S’s – screen, seating and sound. A massive screen size coupled with HEATED DreamLounger℠ leather recliners provide maximum comfort, including a spacious seven feet of legroom between the rows of seats. Add immersive, multidimensional sound for a lifelike experience that makes guests feel part of the action. Speakers are located in the front, back, sides and ceiling to bring even more dimension to the audio of a film.

The system of speakers described is an Atmos installation.

Theater chains typically brand their own PLF installations. Ultrascreen DLX is Marcus’ version, while the B&B chain (the country’s seventh largest, operating mainly in the plains states) has its B&B Grand Screens (see bottom). The first was introduced in 2010 in St. Louis. Some chains mix IMAX with their own brand, depending on the local market. Regal, for example, has 87 IMAX houses and 89 with its proprietary RPX screens. (For a detailed history of the spread of PLF installations to 2016, see Daniel Loria’s “Large Screens, Premium Experience.”)

In many cases, these large-screen auditoriums include other “premium” aspects, such as the big reclining seats, wide gaps between rows, and elaborate sound systems. As with 3D, the ticket price involves an upcharge, but since no fee goes to the 3D company for the glasses and other expenses, the theater owner keeps more of that extra money.

Blame China

It’s common to point out that China, now the world’s second largest movie-exhibition market and soon to become the first, loves 3D. The Chinese are building new theaters at a fast clip, and a high proportion of the new screens have digital 3D capacity. In fact, in 2016, fully 78% of screens in the Asia-Pacific region could show 3D, an astonishingly high proportion considering that in the US the figure was half that, at 39% (according to IHS Markit). And that 78% was a share of far more theaters, 46,949 3D-capable theaters in the region versus 16,745 in the US. Undoubtedly China’s share was larger than its neighbors in Eastern Asia and the Pacific Rim. Other areas of the world also had higher proportions of 3D screens than the US, though not by nearly as much. Europe, the Middle East, and Africa together had 45% 3D screens, and Latin America 43%.

Thus the common wisdom is that Hollywood continues to make 3D films to a large extent to cater to Chinese enthusiasm for the format. Indeed, some films that are released only in 2D in the States are shown in 3D in China, including 2012 (2009), Looper (2012), Iron Man 3 (2013), Lucy (2014), Transcendence (2014), and Jason Bourne (2016). The latter ended up nauseating quite a few Chinese viewers, given its “run-and-gun” style compounded by the 3D.

Naturally Hollywood wants to cater to this giant market, even though the percentages of the ticket receipts returned to the American studios by Chinese distributors are considerably lower than in the US and other markets.

So why show 3D films in the US at all? Presumably there remains enough of a market for them that studios don’t want to risk leaving money on the table. Since they’ve laid out the extra money to make a film in 3D, they might as well show it. There are presumably some people, especially teenagers, who are much more likely to see a film if it’s in 3D.

The question is, will the slow decline of 3D, with fewer films made each year and a lower share of the box-office contributed by them, eventually lead to the complete demise of 3D? Will the failure of 3D TV mean that fewer and fewer 3D films will be released for home-video in 3D? Already this has happened to some extent.

In 2014 for the first time Disney released one of its successful 3D animated films, Frozen, only on standard DVD and Blu-ray. It has continued this policy. In England, though, some Disney films are still released in 3D Blu-ray. Remarkably, amazon.com offers the imported region-free Irish 3D Blu-ray, Blu-ray, and DVD combo of Moana at a bargain price, and it’s not from a third-party seller. We may be out of luck with Ralph Breaks the Internet, since Amazon UK has announced a Blu-ray-DVD set, with no 3D option.

I for one would regret the total demise of 3D. There are relatively few films that I strongly prefer to see in their 3D versions, but it would be a pity if filmmakers did not have the option of making a film like Gravity or Cave of Forgotten Ancestors or Moana in 3D.

It may happen, though. In mid-January an online post in Chinese speculated that people there were becoming less obsessed with 3D. (The original Chinese piece is here, with a brief summary in English here.) How long might take for Chinese moviegoers’ enthusiasm to cool to the extent it has in the USA? Perhaps within a few years China and other overseas markets will no longer provide an adequate support for 3D.

The return of James Cameron

While the world awaits the four threatened sequels to Avatar (currently announced for 2020, 2021, 2024, 2025), we have another another Cameron project to re-excite us about 3D. Originally Cameron had planned to direct Alita: Battle Angel himself, but given the burden of responsibility for all those sequels, he turned those duties over to another advocate of 3D, Robert Rodriguez, with Cameron producing and co-writing. (Sin City is much admired by 3D fans.)

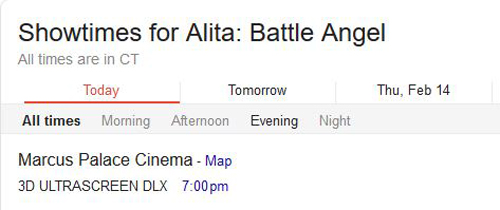

I post this on the second of two days featuring special evening screenings of Alita only in 3D, even as it shows. This has literally been publicized as an event movie, an “Early 3D Fan Event.” (See top.) Only one of our local multiplexes is showing this early screening. Interestingly, it’s the Marcus Palace, which seemed to avoid 3D for the earlier films for which I checked. This being a special fan event, modest swag is involved.

Cameron must be disappointed that 3D has not spread to the point where all screenings of Alita could be in 3D. The existence of this “3D fan event” basically acknowledges that there is a core audience for 3D and another audience, probably much larger, who usually, if not always, would prefer standard screenings. The 3D fans presumably are inclined to come to the film when it first opens, and this event caters to that habit–and ideally generates favorable word-of-mouth for the 3D version.

The film has had a mixed reception from critics, with a 60% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Nearly all the reviews I have read, even favorable ones, fault the script but praise the visual effects (by Weta Digital). Most do not mention the 3D. One enthusiastic reviewer, Molly Freeman on Screen Rant, did mention and laud the 3D, writing, “However, the true star of the movie isn’t the writing or any of the performances, it’s the visuals. To the filmmakers’ credit, the visuals are absolutely stunning and if moviegoers have to choose only one 2019 release to see in IMAX 3D, Alita: Battle Angel is it.” This is a good news/bad news comment. On the one hand, Cameron would be glad to see the 3D in this film recommended so highly. On the other, it does suggest what is happening in reality: that many moviegoers are avoiding 3D unless it has the sort of event cachet that has been created around this particular film. And only time will tell whether audiences will take this advice, at least after the first week or two. Initial reports are not sanguine.

Early on in the run, the Alita will be showing on many screens, PFLs or not. The opening weekend, February 15-17, has this set of offerings in Madison:

Setting aside the IMAX screenings, New Vision has opted for one fewer 3D showings than standard ones. The two Marcus multiplexes have no 3D screenings apart from on their Ultrascreens. The same pattern carries into the following weekdays, except that New Vision has no morning matinees. (The Marcus cinemas, as we’ve seen, starts some screenings as early as 8 am every day.) Marcus management seems to assume that 3D is less appealing on a regular screen than a PLF one, despite the double upcharge. This upcharge, by the way, is significant, especially for a family. An adult ticket for a 2D screening at New Vision costs $11.40, a 3D ticket $15.10, and a 3D IMAX ticket $17.21. That’s just about 50% more for the highest ticket than the lowest.

A news item about Alita reveals one more reason why theater managers might not be overly keen on showing 3D. We all know that 3D glasses are notorious for cutting down the brightness of the projected image. It turns out, however, that there’s much more to it than that. Projecting 3D is not simply a matter of slapping a different lens onto the projector and ingesting a DCP file into the projector, as a fascinating article on Rerelease News reveals. Theaters receive several DCP files, and which one they use depends on the sort of projection set-up they have. Given that projection is now done by people with minimal training, the wrong file sometimes is used. Cameron, Rodriguez, and Jon Landau (who also was a producer on the film) were clearly concerned about this and included a message to theaters playing Alita:

IMPORTANT 3D NOTE: The key to the 3D experience is the light. You have been provided with both a general release 4.5 FL 3D DCP and a premium 6 FL-XBrite 3D DCP. Projecting an XBrite 3D DCP at the standard 4.5 Foot Lamberts of light will result in a dark, hard-to-see presentation. It was especially color graded at 6 foot lamberts and must be run at 6 FL. Projected in this way, it will look amazing!

Conversely, if a general release 3D DCP is shown at 6 FL it will look overly bright. It must be run at 4.5 Foot Lamberts, and it will look terrific at that light level. Since you may have some auditoriums capable of running at 6 FL 3D with others that can only hit 4.5 FL 3D, please confirm that the correct DCP file is loaded in the appropriate theater and that each is run at its proper light level.

This will make a huge difference in the presentation and to audience enjoyment. Thanks so much from Robert Rodriguez, Jon Landau, and Jim Cameron.

I’m sure this is excellent advice, and I hope it is followed, especially at the Marcus Point multiplex near us. Still, I suspect not all theater managers enjoy being confronted with this sort of complexity.

The takeaway from all this is that I and I’m sure many others, were right in predicting that 3D would remain a niche within popular cinema as a whole, confined largely to animation and to fantasy and sci-fi films. More interesting, though, is the fact that PLF auditoriums have proven more popular as a reason to get off the couch and go to a theater, even if the comfort, spaciousness, mega-multi-track sound, and huge screens come at a higher ticket price.

Thanks to David Hancock of IHS Markit for his assistance over the years. Also, thanks to Steve Guttag and Russ Collins for information about 3D. For the story of how 3D became the Trojan Horse in the digital conversion of theatres, see Pandora’s Digital Box.

Thanks also to Jim Healy for some expert opinions and for pointing me to the Rerelease News piece.

PS [Added February 18, 2019] More evidence, for the opening weekend of How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World here in Madison:

[PPS March 6: Tomorrow will be the last 3D showing in Madison, at 5 pm at Marcus Point. After that it will shown only in standard or PLF.]

Vertov, sound technology, and 3D: Recent Blu-ray releases

The Man with a Movie Camera.

Kristin here:

Every now and then we accumulate a few new DVDs and Blu-ray discs and write up a summary of each. This entry is the first time when all the discs discussed are Blu-ray. In fact, none of these releases is available in the DVD format.

Vertov and more Vertov

Soviet director Dziga Vertov is known primarily for The Man with a Movie Camera (1929), one of the most revered silent films. It is a documentary, an experimental film, a city symphony, and a witness to Soviet society in the late 1920s, all in one. Flicker Alley has done great service to silent Soviet cinema with its Landmarks of Early Soviet Cinema and the serial Miss Mend by Boris Barnet and Fedor Ozep. Now it has brought out a Blu-ray disc of a remarkable 2014 restoration of The Man with the Movie Camera.

This version is based largely on a print struck from the original negative and left by Vertov with the Filmliga of Amsterdam, an early cine-club. It subsequently passed to the Nederlands Filmmuseum. The restoration added clips culled from other archival prints to fill in gaps in this copy, producing an edition that will be a revelation to many who are used to the scratchy, contrasty, and cropped prints that have circulated for decades.

For one thing, seeing that missing left side of the frame makes a big difference. A booklet included with the disc points out that modern versions are usually taken from sound prints of the film, which required that the left portion of the frame be reserved for the sound track. As a result, that area of the image was cropped out. This new release restores the full-frame original, and the result is dramatically different from earlier versions. Its visual quality is also impressive (see top).

with the disc points out that modern versions are usually taken from sound prints of the film, which required that the left portion of the frame be reserved for the sound track. As a result, that area of the image was cropped out. This new release restores the full-frame original, and the result is dramatically different from earlier versions. Its visual quality is also impressive (see top).

Yet Flicker Alley has been too modest in emphasizing this as a release simply of The Man with a Movie Camera. The full title of the release is “Dziga Vertov: The Man with the Movie Camera and other Newly-Restored Works.” Yet the “Other Newly-Restored Works,” featured in very small print on the cover, are hardly incidental. They include features that many researchers and cinephiles have long wished that they could view in good prints–or any prints at all.

These other works include most of Vertov’s famous features of the 1920s and early 1930s: Kino-Eye (1924), his first feature; Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass (1931), his first sound feature; and Three Songs about Lenin (1934), a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the death of Lenin.

I don’t think any of these films is as important as The Man with the Movie Camera. For me, Kino-Eye is the most charming, with candid depictions of peasant festivals and the like. It was Vertov’s first opportunity to stretch his ambitions after years of work in newsreels and documentaries. It has a spontaneity that perhaps disappeared in the later features.

The disc includes an informative booklet that discusses both the films and their restorations. As an extra, there is the 1925 Kino-Pravda newsreel episode that Vertov made to commemorate the first anniversary of Lenin’s death. It incorporates rare newsreel footage of Lenin, cutting it together in ways that look like modern gifs.

The visual quality is inevitably variable, with the earlier films looking contrasty, but these are no doubt the best versions that we are likely ever to have. This Man with a Movie Camera supersedes the one from the BFI (in the UK) and from Kino (in the USA), though many will want to have the latter for its lovely score by Michael Nyman. The Flicker Alley version has a very different, but highly appropriate, score by the Alloy Orchestra.

Not all of Vertov’s early features are included. For those who want more, Edition Filmmuseum’s release of A Sixth Part of the World (1926), The Eleventh Year (1928), both with a Michael Nyman score, and one shorter film plus a documentary on Vertov, remains a necessity.

3D curiosities

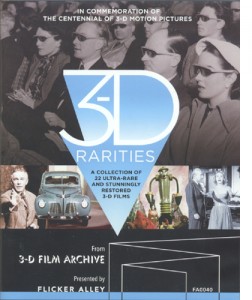

Flicker Alley has also developed a specialty in releasing DVDs and Blu-rays exploring film formats. The company has paid particular attention to Cinerama (This Is Cinerama, Cinerama Holiday, South Seas Adventure, Windjammer, Seven Wonders of the World, and Search for Paradise). Now, in celebration of the centennial of 3D exhibition , it branches out into 3D with 3-D Rarities, described as “A Collection of 22  Ultra-rare and Stunningly Restored 3-D Films.” (Since we cannot reproduce 3D frame enlargements, the images below are taken from the Flicker Alley webpage just linked.)

Ultra-rare and Stunningly Restored 3-D Films.” (Since we cannot reproduce 3D frame enlargements, the images below are taken from the Flicker Alley webpage just linked.)

This BD brings together a thoroughly heterogeneous collection of short items, assembled into two programs. The first, “The Dawn of Stereoscopic Cinematography,” covers the years from 1922 to 1952, with short films made outside mainstream Hollywood. Some test footage by Edwin S. Porter and William E. Waddell shown in 1915 no longer survives, so the earliest films on the program are “Kelley’s Plasticon Pictures” (1922-23), including Thru’ the Trees, a travelogue of Washington, D. C. featuring shots of famous buildings framed primarily by foreground tree branches to create planes in depth.

The items that follow range from promotional films to animated shorts to a burlesque comedy featuring two fairly tame striptease segments and two fairly unfunny comedians. A  promotional film for Chrysler shown at the New York World’s Fair (New Dimensions, 1940) traces the assembly of a new Plymouth in great detail and with impressive animation, with the parts hopping around and sliding into place on their own.

promotional film for Chrysler shown at the New York World’s Fair (New Dimensions, 1940) traces the assembly of a new Plymouth in great detail and with impressive animation, with the parts hopping around and sliding into place on their own.

For many the highlights of this first program will be four shorts from the National Film Board of Canada, two of them by Norman McLaren. The first, Now Is the Time (1951), uses the filmmaker’s familiar drawn-on-film style (right), while the second, Around Is Around (1951), employs an oscilloscope to create more abstract patterns.

Films by two of McLaren’s colleagues are also included: O Canada (1952) by Evelyn Lambart and Twirligig (1952) by Gretta Ekman. These films are among the only ones on the whole program where objects are not thrust or thrown “out” at the audience.

The first program ends with an advertisement, Bolex Stereo (1952), a camera which supposedly was going to bring 16mm 3D home-movies into people’s living rooms. The complicated technology demonstrated shows why the idea did not catch on.

The second program, “Hollywood Enters the Third-Dimension,” consists mainly of trailers interspersed with a few shorts. The trailers include It Came from Outer Space and Miss Sadie Thompson (both 1953). One fascinating film is Rocky Marciano vs. Jersey Joe Walcott (1953), and I say this as one who has no interest in boxing. This 16-minute black-and-white film starts at the training camps of the two opponents and moves on to the match itself, in which Marciano famously knocked out Walcott in less than two minutes. The in-ring controversy over the call occupies the last part of the film, giving the whole thing a distinct dramatic shape. Multiple-camera filming and 3D add visual interest.

Stardust in Your Eyes (1953), a comedy short starring comic and impersonator Slick Slavin (aka Slaven in the credits), is said in the program notes to have been “a big hit at 3-D festivals. Judge for yourselves, but I advise keeping a finger on the next-chapter button for this one.

Few of these shorts can be said to be important classics of the 3D repertoire, but overall one gains a sense of the surprising range of films made with the process. One also learns that thrusting guns, spears, swords, and even sling-shots toward the audience, as well as throwing stones and other missiles at them, never grow old as far as the makers of these films are concerned. We have a pistol aimed at us in one of the “Kelley’s Plasticon Pictures” from 1922 (below left) and a rifle in the trailer for Hannah Lee (1953, right).

At least we now have the 3D version of Mad Max: Fury Road to recharge this particular visual trope in highly original ways.

Sound marches on

Way back in 2008, when this blog was a mere two years old, I reported on the first volume of a two-disc set of DVDs inaugurating the highly ambitious project, A Century of Sound: The History of Sound in Motion Pictures. That first volume covered the period to 1932. This one is entitled “The Sound of Movies: 1933-1975.” There was of course a lot more recorded sound in that period, and the new set stretches to four Blu-ray discs, for a total of over twelve hours of running time.

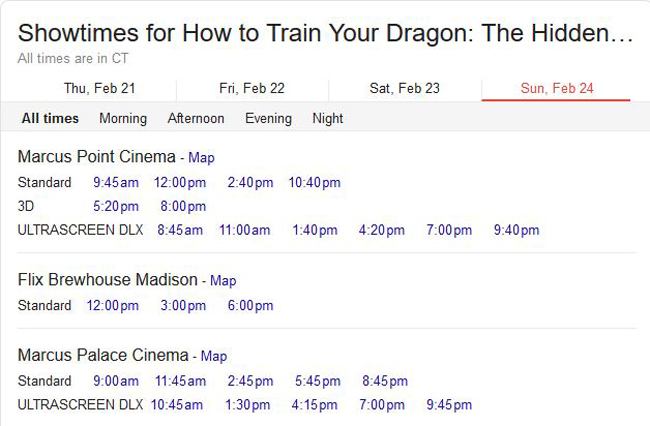

I can’t claim to have watched all those hours, but every section I sampled boasted extraordinary amounts of information. Robert Gitt, who originated the project with a 1992 lecture, again narrates. The coverage includes a huge number of rare diagrams, photographs, documents, and demo reels. In addition, many of the chapters add clips from films that contained the most innovative sound techniques of their day. The Garden of Allah, Okhlahoma!, Medium Cool, and many other titles are excerpted in superb copies.

The set as a whole is a gold mine for specialist researchers and technology buffs. The discs include long and detailed passages on such topics as push-pull recording and noise reduction, the latter a crucial challenge to the sound-recording industry for decades. Teachers who searched assiduously could find many clips suitable for classroom use.

A fair amount of the material ought to be interesting to nonspecialists too. For example, the third disc includes a history of early multi-channel and directional sound. The section on early stereophonic systems is fascinating, with its coverage of Leopold Stokowski’s participation in the two most important early films to introduce this new technology to a popular audience: 100 Men and a Girl (1937) and Fantasia (1940). We get generous clips from each. From 100 Men and a Girl, we see most of the famous scene in which an orchestra plays on different levels of Stokowski’s house and multiple channels allow sonic “close-ups” of each type of instrument over close views of that section of the orchestra:

A thorough history of Fantasia includes the image below, typical of the sorts of material The Century of Sound presents: the Fantasound optical printer invented in order to print the multiple optical tracks used for the film’s stereo.

And someone obviously could not resist including a goodly dose of the short dances from the Nutcracker Suite section of the film (see bottom).

The Century of Sound is not for sale commercially. It “is available free of charge to educational, archival and research institutions and to qualified individual educators, researchers and scholars as a not-for-profit educational resource.” There is a modest fee for shipping. For information on ordering, write to CenturyofSound@cinema.ucla.edu.

Flicker Alley’s release of This Is Cinerama provoked David to a survey of Cinerama aesthetics in an earlier entry.

Fantasia.