Archive for the '3D' Category

GRAVITY, Part 1: Two characters adrift in an experimental film

There was no way to rely on anything we knew before this film. No character was like Stone, no film set was ever like these sets, not one member of this crew had ever done this before. We all were doing something that had never been done before.

Kristin here:

Back in mid-September, on the verge of leaving Madison to attend the Vancouver International Film Festival, I mentioned that I had watched one of the trailers for Gravity and thought it looked like “the most exciting new piece of filmmaking this year.” I added that the trailer “called ‘Drifting’ reminded me of Michael Snow’s brilliant Central Region, but with narrative, with the earth and stars spinning past a close-up of Sandra Bullock as the marooned, panicky astronaut protagonist.”

At that point, I wondered whether the film as a whole could keep up that experimental feeling, with vertiginously wheeling actors combined with an untethered camera swooping around them. Or would the narrative gradually lead us into a more conventional style later in the film? It turns out that, to a remarkable extent, the highly unconventional treatment of unanchored space, where up, down, and sideways characters and background change with a breathless rapidity, extends through much of Gravity‘s length. For brief intervals Ryan enters space capsules and sits, right-side up, and the action calms down briefly. Yet these lead to further scenes in space with the same swooping camera. In short, the film turned out to be as remarkable a formal and stylistic achievement as I had hoped.

SPOILER ALERT. This is not a review but an analysis of the film. Gravity does depend crucially upon suspense and surprise, and I would suggest not reading further without having seen the film.

An experimental blockbuster

I am not the only one who was struck by Gravity‘s resemblance to an experimental film. After the film’s opening weekend in the USA, Variety‘s Scott Foundas published an article on the subject: “Why ‘Gravity’ Could Be the World’s Biggest Avant-Garde Movie.” He references the influence of Jordan Belson’s work on 2001: A Space Odyssey and speculates that the final shot of The Shining echoes the ending of Michael Snow’s Wavelength. More specifically he links Gravity to Central Region, shot in 1971 at in a Canadian mountain range; Foundas describes the robotic arm used to shoot the film and how it was controlled by instructions on magnetic tape. (I’ll have an illustration of the robotic arm in Part 2.) To Foundas, the avant-garde aspects of Gravity outweigh its narrative: “‘Gravity’ has more of a plot than ‘La Region Centrale,’ but only barely, and surely no one is telling their friends to see Cuaron’s film because of its great story. Rather, it’s the very absence of a dense narrative line that gives ‘Gravity’ its majesty.”

I think that to say Gravity has “only barely” more narrative than Snow’s purely abstract film is a considerable exaggeration. The film’s story is certainly simpler and more unconventional than other mainstream Hollywood films, but as we shall see, it contains goals, motifs, character traits, careful setups of upcoming action, and other traits of classical narratives.

In an October 11 blog entry, J. Hoberman also stresses the film’s modernism:

Depth and volume are illusory. Mass has no weight. In this 3-D spectacle, best seen on the outsized IMAX screen, Cuarón promotes sensory disorientation–or better, reorientation. […] Gravity is something quite rare–a truly popular big-budget Hollywood movie with a rich aesthetic pay-off. Genuinely experimental, blatantly predicated on the formal possibilities of film, Gravity is a movie in a tradition that includes D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance, Abel Gance’s Napoleon, Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia, and Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, as well as its most obvious precursor, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001. Call it blockbuster modernism.

(Actually I’d say Gravity is better than some of these, notably Napoléon and 2001.)

Hoberman sees more of a balance between style and narrative than does Foundas. In fact, he considers that the film contains “a distracting surplus of backstory.” Presumably he would prefer to do without the references to the death of Stone’s daughter and her subsequent aimless car rides after work, listening to the radio. The space voyage does become an overly obvious extension of that drifting and listening, coming close to turning the film into a maternal melodrama. Presumably the filmmakers felt that simply sending Stone on a mission and having her struggle to return to earth was not enough. In interviews, the co-scriptwriters, Alfonso and his son Jonás Cuarón, emphasized that their basic idea was to create a character arc of her “rebirth” after despair. To some, this arc, with its religious overtones, will seem a bit, as Hoberman says, distracting and even contrived. To others it may be inspiring. At least it is not allowed to come forward very often.

Hoberman stresses the balance of plot and radical style. The film, “premised on the absence of up or down, is naturally abstract although it also has a streamlined and suspenseful narrative that, save for one or two ellipses, might almost be happening in real time.” In Variety, Justin Chang’s review highlights the same balance: “at once a nervy experiment in blockbuster minimalism and a film of robust movie-movie thrills, restoring a sense of wonder, terror and possibility to the bigscreen that should inspire awe among critics and audiences worldwide.”

David and I have often claimed that Hollywood cinema has a certain tolerance for novelty, innovation, and even experiment, but that such departures from convention are usually accompanied by a strong classical story to motivate the strangeness for popular audiences. (This assumption is central to our e-book on Christopher Nolan.) Gravity has such a story, though Cuarón is remarkably successful at minimizing its prominence. The film’s construction privileges excitement, suspense, rapid action, and the universally remarked-upon sense of immersion alongside the character in a situation of disorienting weightlessness and constant change.

That construction derives partly from techniques unique to this project. The weightless dance of characters and camera almost entirely does away with such widely applied spatial premises as the axis of action, eyeline directions, and the establishing of stable spatial relationships. And, as Cuarón pointed out in an interview for Wired, “After all, you learn how to draw based on two main elements: horizons and weight.” Those two factors are virtually gone as well.

The weightlessness and the long takes in the film have been given much attention in the press. Reports refer less often to the “Light Box, one of the film’s most extraordinary innovations. It is a giant inside-out LED monitor that allows the film’s own previs special effects to light the faces and bodies of the actors inside the box, making it possible for those shots to be integrated seamless into the effects shots. Basically, apart from the scenes inside space vehicles, traditional three-point lighting is jettisoned along with spatial relations.

Other technical aspects of the film are innovative. A bold new camera mount, the Isis, was devised to allow the camera to twist and whirl around the actors. The silence of space was respected by the filmmaker, leading them to substitute a eerie musical score to replace sound effects and convey emotions. The blocking and acting, of course, had to be vastly different from methods used in conventional films where the actors have the luxury of walking on a ground plane.

In short, it is hard to think of another mass-audience film in recent years that has so thoroughly departed from the current technological and stylistic conventions of mainstream filmmaking. Jurassic Park and The Lord of the Rings, to be sure; perhaps Avatar. Publications devoted to the techniques of cinema have recognized this. The Cinefex issue dealing with Gravity is not yet out, but on the journal’s blog, Don Shay’s remark is quoted: “Every once in a while, a film comes along that is a game-changer. This is one of those films.” Debra Kaufman, writing about the film’s 3D for Creative Cow, agrees: “Anyone who’s seen Gravity 3D will agree that the 3D was a game changer.” And unlike those earlier game-changers, Gravity has a strong experimental component to it that audiences gladly accept, since it is so well motivated by the story and situation.

In the next blog entry, I’ll survey the innovative aspects of Gravity‘s style and technique. Today, though, I’ll concentrate on the plot–in some ways conventional and in some ways quite strange–that holds it all together.

Who needs psychological depth in a crisis?

Arguably Cuarón had constructed nearly the most sparse narrative that can sustain the experimental style and motivate that style enough to hold the attention of a popular audience. Three characters, then two, then one, all with minimal backstories and simple goals.

Most Hollywood films have two parallel plotlines, usually one involving a romance. Here there is only one, and it primarily concerns an immediate situation, a cycle of deadly threats alternating with stages of Ryan’s progress toward safety. On balance, the focus is more on the suspense and terror of the situation than on the characters. Although there is a little mild flirtation between Stone and Kowalski, it’s more to generate humor and defuse the tension than to suggest any real possibility of mutual attraction.

One indication of the film’s minimal characterization is that fact that we never learn the nature of Stone’s experiment. That would be a logical initial goal for her character. Why has she set herself this particular task, which obviously involved not only scientific expertise in a complex field but also elaborate training to become an astronaut? Where does she work? What might her test achieve? Some reviews have referred to her as a medical expert. As far as I can tell, this is based on one line when she and Kowalski are working together to activate the communications device that is her focus of attention in the opening scene. During the calm before the debris collision, she remarks, “I’m used to a basement lab in a hospital where trays fall to the floor.” She also says that “It’s designed for hospital use.” That’s it. Normally a Hollywood film would redundantly give us information about her job. Here we don’t even get a sketch of it. And why is a medical experiment attached to the Hubble Space Telescope?

Incidentally, the Hubble is detached from the shuttle just before the debris cluster reaches it. We never learn whether it, too, is destroyed in the disaster. Might it have survived, with Stone’s experiment, perhaps activated during her brief delay before obeying the mission-abort command? Might she return to earth to find her experiment a success, with her initial goal miraculously achieved despite the tragic events in space. So little is the narrative concerned with the experiment as a significant goal that such questions are unlikely to occur to a spectator. They came to me only after three viewings.

Stone’s casual reference to working in a hospital lab typifies the limited sort of backstory we’ll get for the most part. Aside from Stone’s recollections of her daughter’s death and her aimless evenings of driving as her form of mourning, the moments of backstory are mere hints. In the opening we learn that Matt’s wife left him when he was in space on a mission. Might he be so obsessed with the beauties of space travel because he, too, is seeking to escape loneliness? We can’t know, since he treats the mention humorously, as if he has managed to shrug off his wife’s betrayal. Of the third character present on the spacewalk, Shariff, we learn that he has a wife and son, something revealed by a photo only after his death. This knowledge serves less to characterize him than to contrast this cheerful fellow with the wifeless Kowalski and childless, unattached Stone.

Stone’s mention of her home in Lake Zurich, Illinois and of her daughter’s death is the last piece of backstory that we get, and it comes slightly under half an hour into the film, during the calm interlude when she and Kowalski are slowly traveling toward the International Space Station (ISS). After this, I believe the only scrap of information from her past that we get is that Stone’s daughter had worried about a lost red shoe.

This lack of information about the characters is probably what led Foundas to say that the film has “barely” more of a plot than Central Region. In the same piece, he speculates, did the executives at Warner Bros. “wonder if they’d just gambled away $100 million on the most expensive avant-garde art movie ever made?”

Kevin Jagernauth reports on indiewire that the studio pushed for a more conventionally constructed film. Cuarón told him about some of the feedback he got from WB:

But at first, the studio suggested that [the Mission Control] team in Houston should get more face time. “…there area lot of ideas. People start suggesting other stuff. ‘You need to cut to House and see how the rescue mission goes.'”

And that’s not all. Part of the emotional journey of “Gravity” rests on Stone’s backstory, which includes a daughter she lost, but this is all effectively communicated without breaking the single location concept. However, Cuarón was advised to perhaps include some flashbacks in the film and even more. “A whole thing with … a romantic relationship with the Mission Control Commander, who is in love with her. All that kind of stuff. What else? To finish with a whole rescue helicopter, that would come and rescue her. Stuff like that,” he explained of some of the ideas that were floated his way.

There’s that conventional second romantic plotline, which in the wake of the film’s success seems such a ludicrous suggestion. The studio’s attitude demonstrates how very much Cuarón was able to get away with and how much of a struggle it must have been. Audience and critical enthusiasm suggests that he and his team managed to include just enough classical storytelling to make spectators identify with the characters even while knowing very little about them.

Why would a film need to establish psychological depth for characters when most of what they’re going to be doing is struggling frantically for their lives, cast adrift in space and bombarded by hurtling space debris? They must summon what skills and psychological strength they have and get on with it. Thoughtful conversations and subtle complexities are irrelevant for the most part. We need to care about these people to be engaged by the film, but that is part of the point of having Sandra Bullock and George Clooney as the leads, playing to the likeable personal qualities that we already associate with these stars.

Challenges and goals

There’s no question that the characters do have goals, but these are largely based on circumstances thrust upon them rather than on character traits. Before disaster strikes, the characters have short-term goals: Stone to solve the glitch with her equipment (and to avoid allowing nausea to cut short her attempt) and Kowalski to enjoy his final space walk and ideally break the record for duration of space walks. Both goals are cut short by the news of approaching debris and the mission-abort order. As we’ve seen, whether Stone achieves her original goal concerning her experiment is never revealed, nor are we encouraged to wonder even briefly as to whether the Hubble might carry it away from the destruction of the shuttle. Kowalski achieves his goal of breaking the record, in a sense, as he comments ironically while detached and drifting in space and awaiting his death. His space walk will last forever, but records are hardly intended to include corpses.

Once Stone spins off into space, alone, her goal is to re-establish contact with Mission Control and Kowalski. His is to rescue her. Once he finds her and tethers them together, their mutual goal is to get to the shuttle, with Kowalski adding the goal of retrieving Shariff’s body. Very quickly these goals are shattered, since the shuttle has been extensively damaged and its other crew members killed. A new short-term goal arises: reaching the relatively nearby ISS.

Kowalski fails to achieve this goal, since the fuel in his jetpack and his inability to grab anything on the ISS’s exterior send him floating off into space. Stone’s goal is now to get inside before she passes out from lack of oxygen. Once inside, her goal is to detach the remaining semi-functional Suyuz landing vehicle and use it to get as far as the Chinese space station, in turn using its landing pod to return to earth.

Discovering that the deployed parachute has become tangled in the ISS, she takes another space walk to detach it from the Soyuz. Another short-term goal that is soon accomplished. As she starts to remove the bolts anchoring the parachute, she states the short-term and long-term goals: “OK, we detach this, and we go home.”

Her purpose, however, seems to be thwarted when the fuel tank of the Soyuz vehicle proves to be empty. Here Stone loses hope, drifting into despair. She decides to turn off the oxygen supply and allow herself to die. Suddenly Kowalski appears and enters the pod, giving her a pep talk and telling her to use the soft-landing function of the Soyuz rather than its take-off capabilities. He disappears, and Stone, reinvigorated and determined, follows the instructions for landing the craft.

In traditional classical films, shifting goals often mark the turning point between large-scale sections of the plot, generally referred to as acts. Despite its unconventional aspects, Gravity’s plot does stick fairly closely to the well-balanced four-part structure that I have claimed is typical of Hollywood narrative conventions. Not counting titles or credits, the story runs approximately 83 minutes. Thus on average the acts would run about twenty-one minutes each.

At about 22 minutes in, Stone and Kowalski achieve their goal by reaching the shuttle, only to discover that it has been destroyed. At 23 minutes, Kowalski declares them the last survivors of the mission. I take this to be the first turning point, ending the setup and beginning the complicating action. Essential premises are reversed as the pair realize that they are stranded in space and they shift their goal, striving next to reach the ISS. Stone’s failed attempt to contact Kowalski by radio once she enters the ISS–she initially hopes to rescue him–and declaration of herself as the mission’s sole survivor happens at roughly 43 minutes. The third act, the development, begins, with Stone meeting numerous obstacles that threaten her new goal of getting back to earth in the Chinese landing vehicle. The last turning point, launching the climax, comes when Stone awakens from her dream about Kowalski and turns the oxygen flow back on, signaling her return to hope and determination to reach earth. That happens at about 66 minutes in, leaving seventeen minutes for her landing, including the brief epilogue of her floating, swimming ashore, and shakily standing up.

Motifs and causal motivation

As I mentioned, strongly innovative films in the Hollywood tradition need the support of classical conventions to keep the narrative clear and appealing. Two of Gravity‘s most traditional techniques are its motifs and its motivations. Motifs can quickly make the characters more vivid, even if they are not particularly rounded or complex. Motivations often involve planting an object or event in advance. In this film, several motifs trace the relationship between Stone and Kowalski.

In the opening, the motif of Kowalski’s wanting to break the space-walking record is introduced early on, stressing that this is his last mission and hinting that he loves his time in space. Similarly, his anecdotes, introduced with the “I’ve got a bad feeling about this mission” running gag, create irony but also suggest how Kowalski inspires Stone. Before setting out on her re-entry flight in the Chinese landing pod, she repeats this line with the same good humor that Kowalski had displayed. Another parallel is set up between the two when Stone detaches the clasp tethering her to the wildly spinning support in the opening scene, and later Kowalski does the same to separate himself from Stone when they are precariously suspended from the ISS (below). She comes back; he doesn’t.

In the early scene where the pair work to activate Stone’s equipment, he refers to her “beautiful blue eyes,” though she points out that hers are brown. Later, when Kowalski has set himself adrift in space, their radio conversation mentions his “beautiful blue eyes,” which are also brown. Though we see nothing of their earlier relationship, such motifs lend it depth, because we sense that the two have already developed a customary way of bantering with each other.

Similarly, in the opening scene, Kowalski tells an anecdote about how, during a previous mission, he had imagined his wife looking up into space and thinking about him, when in fact she had run off with another man. Later, as Kowalski moves toward the ISS dragging Stone tethered behind him, he asks her if anyone is looking up and thinking about her. This elicits her most intimate revelation, that she had had a daughter who died in a freak accident. There is also no Mr. Stone waiting at home for her. Thus although the two characters have different personalities, both are escaping loneliness by a retreat to the beauty and peace of space.

Finally, there is the last shot, with Stone seen from behind against the sky, covered by light clouds. It reverses the opening, when we were in the opposite position, looking down at the earth from space, with the clouds of a huge hurricane prominently visible. There Stone drifted in space, held in place by a large mechanical arm; here she struggles to regain her sense of balance after prolonged weightlessness and succeeds in walking a few steps, thanks to gravity.

Like motifs, careful motivation of action helps us navigate through the plot. Given the rapidity with which new information is thrown at us as the narrative progresses, the screenwriters are careful to set up major premises in advance so that we will quickly understand them when they arrive. In the opening scene, as Kowalski swoops cheerfully around the shuttle, Houston asks about the supply of fuel in his jetpack. He reports that it’s 30% down. Not a lot, but enough that we are prepared for the moment after the disaster when he says he’s running “on the fumes.”

During the opening, the messages from Mission Control thoroughly forewarn us of the rapidly approaching hail of space debris. After it passes, Kowalski has Stone set her watch for 90 minutes, since that is when they can expect the same debris to return–as it does at regular intervals to destroy the ISS and the Chinese station. Stone reminds us of this danger when she exits the Soyuz vehicle to detach its parachute, muttering, “Clear skies with a chance of satellite debris.” The presence of the deployed parachute also sets up the moment when the chutes of the Chinese pod deploy as it nears its splashdown in the final sequence.

As Stone struggles to get aboard the ISS, Kowalski converses with her via radio. They mention her training with landing vehicles. Her only experience has been with simulators, and in every case she crashed them. Still, as Kowalski points out, she knows something about them–a point which proves vital in the dream scene discussed above, where Stone’s mind summons up a memory about how launching and landing space vehicles are not all that different.

Apart from creating a brief scene of suspense, the fire in the ISS introduces the fire extinguisher and demonstrates how, in a situation of weightlessness, the extinguisher propels Stone through space. This prepares us for the crucial scene in which she uses it as Kowalski had used the jetpack, allowing her to reach the Chinese station despite being untethered in space.

Character motivation, fortuitous events, and religion

Throughout the film the cause-effect chain remains fairly straightforward, with one major exception that I’ll get to shortly. But because the characters are reacting to rapidly changing circumstances almost entirely beyond their control, the outcomes are often fortuitous rather than the result of character traits. This is not to say the film uses numerous coincidences. It is not coincidence that Stone manages time and again at the last possible moment to grab a pipe or handle on the outside of a space vehicle. She’s aiming to do that, so she manages it not by coincidence but by luck.

Some of the most crucial events in the film are partly a matter of character motivation, but the outcomes of Stone’s and Kowalski’s actions are fortuitous. Stone apologizes to Kowalski for not having immediately obeyed his order to stop trying to repair her equipment and head for the space shuttle. She presumably continued with the rebooting because she is a dedicated researcher, reluctant to abandon her important work even when in physical danger. Yet as it turns out, reaching the space shuttle interior would have been fatal. When Kowalski and Stone do reach the shuttle, they find it split open, its crew dead–just as the pair would be had they retreated inside immediately. Stone’s delay actually saved the pair, though neither character could know this at the time.

Less obviously, Kowalski accidentally dooms himself. We see him in the opening minutes, cheerfully circling the shuttle and Hubble, playing music, telling anecdotes, and apparently hoping to stay outside the shuttle long enough to set a record. Presumably he has already accomplished his task in the space walk, or perhaps as the most experienced member of the team, he is watching over the other two. He is also, however, wasting fuel–fuel that he doesn’t realize he may need. Later, when forced to travel through space to rescue Stone and then to make it from the shuttle to the ISS, his tank becomes empty just before they reach it. His inability to maneuver without endangering Stone leads to him detaching his tether and stranding himself in space forever.

There are other fortuitous events. Stone is lucky that her Chinese pod lands in a body of water but close enough to shore that she can survive the impact and get onto land easily. It is probably by chance that in entering the Soyuz craft, the weightless fire extinguisher blocks the door and that she pulls it into the craft rather than pushing it out. Later the extinguisher enables her to propel herself to the Chinese station. There are also obstacles fortuitously created, as when Stone discovers that the Soyuz vehicle has no fuel–presumably because its supply tank has been ruptured by flying debris.

There may be one major exception to this dependence on accidental causes and effects: the religious motif. This is a strange motif, since it doesn’t become significant to the plot until fairly late. Early in the complicating action, as Kowalski and Stone journey toward the ISS and he asks her about her life on earth, he’s playing a country song, “Angels Are Hard to Find.” It’s playing when Stone mentions her daughter’s death; Kowalski soon turns it off to pay more serious attention to her story. At the time, the song doesn’t seem relevant. About seventy-two minutes in, the religious motif returns and becomes more prominent. Stone discovers that the Soyuz fuel tank is empty. The vehicle drifts as sunset settles on the earth below. We see vast snow fields and fjords below, and frost forms on the window. (The cut to the frosty window is one of the film’s few apparent ellipses.) There is a brief shot of a Russian icon inside the Soyuz (Christ as a child carried by John the Baptist, I think).

Immediately after this, Stone makes contact with someone on earth. She tries to communicate her mayday call. Gradually she loses hope and begins woofing in echo of dogs she hears on the radio. She says she’s going to die. During this scene she talks of how there is no one on earth who will mourn or pray for her soul. She asks the man to “Say a prayer for me.” She adds, “I’ve never prayed in my life. Nobody ever taught me how. Nobody ever taught me how.” A baby is heard on the radio, and the man apparently sings a lullaby to it. Stone sadly comments, “I used to sing to my baby. I hope I see her soon.” At that point she dials down the oxygen inflow and says, “Sing me to sleep, and I’ll sleep.”

As she falls asleep, a knock on the door is heard off, and Kowalski enters the Soyuz. He drinks some of the hidden vodka, chats, and tells her to use the soft-landing device. Although he sympathizes with her desire to surrender to the eternal peace of space, he encourages her to save herself rather than giving up: “Ryan, it’s time to go home.” After his disappearance, Stone once again strives to save herself.

Once she has reached the Chinese landing pod, she struggles to cope with its instrument control-panel. As the countdown clock starts running, there is a tilt up to a little Budda figure, roughly in the spot where the icon had been on the Soyuz. As Stone works, she talks to Kowalski, asking him to find her daughter: “Tell her that she is my angel.”

Finally, back on earth, in the final shot Stone struggles to rise, muttering “Thank you,” before walking away from the camera, which tilts up to a low angle of her against the sky.

Though this motif appears late in the film, the narrative stresses it. Something is going on here, but what?

Most obviously, Stone seems to become somewhat religious, despite never having prayed before. Perhaps this is simply an emotional change that allows her to reconcile somewhat to her daughter’s death, to feel hope and enthusiasm for carrying on with her attempts to reach earth, and to accept her survival as a gift to her from some sort of deity.

Given that the startling visit of Kowalski, whom we assume to be dead, to the Soyuz and also his providing Stone with the one bit of information she needs in order to carry on, we might assume that this scene presents a sort of miracle. Kowalski’s visit makes him a quasi-angelic figure bringing divine intervention to Stone, perhaps, or simply a vision inspired by a divine power.

Yet his return is cued as a dream, with Stone falling into a sleep that she assumes will end in death. We all have had some sort of experience with a dream providing inspiration or the solution to a nagging problem. As Kowalski points out, Stone should know that taking off and landing are essentially the same thing; it was part of her training. The dream does not give her the knowledge but rather reminds her of it. Indeed, after she wakes up, she still has to struggle to remember what she learned about soft landings and also consults the manual.

Everything in the dream reflects things we already know about the two characters. Kowalski mentioned knowing where the vodka is kept. Earlier he had reminded her of things she knows about landing from her training with simulators. His words to her about the sorrow of losing her daughter and the temptation to surrender to the eternal peace of space recall her own line from the beginning when he asked her what she likes about space: “The silence. I could get used to it.” (Cuarón, in an interview with Anne Thompson, refers to Kowalski’s return as “a projection of herself in a dream.”)

Seemingly Stone gains some sort of religious belief or spiritual consolation. While working on the Chinese pod’s controls, she talks animatedly to the absent Kowalski, whom she apparently envisions meeting her daughter in an unspecified afterlife. The “Thank you” at the end I take to be the conclusion of this monologue in the pod, thanking Kowalski. In a truly classical film, a character mentioning never having learned to pray would surely say a prayer later in the film. Stone never does. I interpret the religious motif as signaling a transformation of her attitudes rather than implying some sort of divine intervention to rescue her. Either way, some viewers might take this motif to be heavy-handed or saccharine, but its ambiguities could prevent others from having such reactions.

It all worked

The combination of narrative techniques that I have just analyzed obviously appealed to many of the the people who have seen the film.

On November 1, Box Office Mojo summed up the film’s career since its October 4 release:

Through four weeks in theaters, Gravity earned $206.1 million, which accounted for just under a third of total domestic box office earnings in October. It’s already the highest-grossing movie ever to be released during the Fall (September or October) and will earn at least another $50 million before the end of its run.

Gravity‘s remarkable success can be attributed in part to Warner Bros.’s great marketing campaign, which helped the movie set an October opening weekend record ($55.8 million). From there, the movie had an unprecedented second weekend hold thanks to world-of-mouth that asserted the movie needed to be seen on the biggest screen possible (and preferably in 3D). Speaking of 3D–Gravity‘s box office has been pumped up by the fact that most people (around 80 percent) are choosing to pay an extra few bucks to see the movie in that premium-priced format.

According to Variety, “Imax contributed 21% of the opening-weekend domestic cume for the film.”

(Even I, no fan of 3D, have seen it in that format at two of my three viewings so far and would do so again.)

Abroad, the film has also done well. As of November 6, its foreign box-office gross is about $207 million, with the film still to open in several major markets, and its domestic take has risen to almost $220 million, expected to top out at $260 million.

[Nov. 10: Box Office Mojo is now estimating that Gravity will ultimately gross about $660 million worldwide. It opened this weekend in the United Kingdom, where 89% of its ticket sales were for 3D screenings.]

This is also one of those rare films people see in theaters repeatedly within a short period. By the end of its opening weekend, three percent of audience members said they had already seen it more than once. On October 21, the film’s official FaceBook page asked fans, “How many times have you seen the film in theaters?” One, two, or three times were common, but even by that date, two and a half weeks into its run, there were a few who had seen it four or five times. Many single and repeat viewers mentioned plans to see it again. Quite a few also specified which formats they saw it in at the different screenings. Dan Fellman, head of Warner Bros.’s domestic distribution, remarked, “This is a phenomenon where people are asking friends and family not only if they’ve seen the film, but where.”

Some moviegoers (and critics) have found the film boring. But those who love it really love it.

Our next entry will deal with the film’s style and how it was achieved.

Coincidences can play many roles in a film’s plot, as we discuss in this entry. You could take Gravity’s ambivalent gestures toward Stone’s spiritual redemption as another example of Hollywood’s strategic ambiguity about controversial themes.

Jason Mittell has written an essay, “Gravity and the Power of Narrative Limits,” which nicely complements my analysis. He concentrates on the film’s relation to traditional genres, discussing how it departs from familiar conventions of science-fiction and survival narratives.

P. S. 9 November: After I linked to this entry on my Facebook page, Meraj Dhir commented that the song Shariff sings as he does his little weightless dance is from a famous number in Raj Kapoor’s 1955 musical Shree 420. Not exactly relevant to my analysis, but fun to know, so thanks, Meraj! You can see the number here.

NOTE: On November 8, after watching the film a fourth time, I revised this post, correcting a few errors and quoting some brief passages of dialogue that I was able to record on this go-through. I have not noted the changes with the usual strike-through lines, since it seemed too complicated and distracting to do so in this case.

Side by side by side: Quick catchups

David Lynch in the documentary Side by Side.

DB here:

Some developments related to recent posts we’ve done!

On digital cinema: Cineaste magazine has published a wide-ranging “Critical Symposium on the Changing Face of Motion Picture Exhibition” in its most recent issue. It gathers in-depth reflections from Grover Crisp, the Ferroni Brigade, Scott Foundas, Bruce Goldstein, Haden Guest, Ned Hinkle, J. Hoberman, James Quandt, D. N. Rodowick, and Jonathan Rosenbaum. I add some comments too. A preview is here, but the responses are available only in the print edition. That edition also includes two signature Cineaste interviews, this time with Kirby Dick and Eyal Sivan, along with another symposium of great interest, devoted to film editors’ response to the rise of digital postproduction. As regular readers know, the series I composed on digital projection, Pandora’s Digital Box, has been revised and turned into an e-book.

On digital cinema: Cineaste magazine has published a wide-ranging “Critical Symposium on the Changing Face of Motion Picture Exhibition” in its most recent issue. It gathers in-depth reflections from Grover Crisp, the Ferroni Brigade, Scott Foundas, Bruce Goldstein, Haden Guest, Ned Hinkle, J. Hoberman, James Quandt, D. N. Rodowick, and Jonathan Rosenbaum. I add some comments too. A preview is here, but the responses are available only in the print edition. That edition also includes two signature Cineaste interviews, this time with Kirby Dick and Eyal Sivan, along with another symposium of great interest, devoted to film editors’ response to the rise of digital postproduction. As regular readers know, the series I composed on digital projection, Pandora’s Digital Box, has been revised and turned into an e-book.

As for digital production, that’s the center of the new documentary film by Christopher Kinneally called Side by Side. It has played several festivals and is now available on Pay Per View via Tribeca. I think it’s a balanced, lucid introduction to the pros and cons of shooting digitally, as well as a helpful historical overview of the development of cameras and capture systems. It includes interviews with Scorsese, Lynch, Cameron, Fincher, and many other directors, along with a wide selection of editors and cinematographers. (DP Geoff Boyle adds some especially salty comments.) Side by Side is especially strong on post-production; how often do you get comments from Digital Colorists? There’s a little bit about exhibition too. Keanu Reeves makes a well-informed and unobtrusive interviewer. In all, the film would be a very good teaching tool in introductory courses. Kinneally discusses the project at Filmmaker.

I was a little surprised by the popularity of my entry on Cinerama, written in response to Flicker Alley’s magnificent release of This Is Cinerama on Blu-ray. Now there’s a podcast by David Strohmaier, the moving force behind reviving interest in the format. See The Commentary Track. Speaking of Cinerama, Kristin and I enjoyed our visit to Seattle’s Cinerama Theatre, where we saw The Master in 70mm. The theatre has been magnificently restored to its 1960s glory, Populuxe decor and all. Occasionally three-panel Cinerama films are screened there. And I should mention that while I was yearning from afar, the Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles held a festival earlier in the fall.

LIke Cinerama, classic 3-D holds perennial fascination, especially for baby boomers like me. I was lucky enough to see the digital restoration of the stereoscopic version of Dial M for Murder at the Toronto International Film Festival, and I wrote about it here. Bob Furmanek, expert in the format, provided an in-depth discussion of it on his site, 3-D Film Archive. Now Bob and Greg Kintz have added an equally intense backgrounder on The Creature from the Black Lagoon. As Bob writes to me: “Only 48 more Golden Age titles to go!”

LIke Cinerama, classic 3-D holds perennial fascination, especially for baby boomers like me. I was lucky enough to see the digital restoration of the stereoscopic version of Dial M for Murder at the Toronto International Film Festival, and I wrote about it here. Bob Furmanek, expert in the format, provided an in-depth discussion of it on his site, 3-D Film Archive. Now Bob and Greg Kintz have added an equally intense backgrounder on The Creature from the Black Lagoon. As Bob writes to me: “Only 48 more Golden Age titles to go!”

Now that Dial M is available in a 3-D Blu-ray disc, I think it’s worth mentioning that this is something of a milestone for film analysis. When I was first studying 3-D in the early 1980s, it was almost impossible to see vintage films in the format. Although archives held copies, those were typically flat versions. Even if the archive had both the A and B films, they would have been very difficult to screen. Worse, it would have been impossible to study 3-D shooting using the major tool at my disposal, the 35mm flatbed viewer. Now, viewers with 3-D TVs and 3-D players, can study Dial M and Creature shot by shot, even freezing frames to examine exactly how the shots are designed. This isn’t usually mentioned as a benefit of the new technology, but digital restoration and displays let us examine movies in 3-D in unprecedented detail.

In July I reviewed the local fracas over our old picture palace, the Orpheum. Things were quiet over the summer, but now it’s all up for grabs again. The promised foreclosure is in the offing, followed by interim management from the team that handles Lollapalooza and Austin City Limits. The Wisconsin State Journal‘s Steve Elbow brings us the news here and here.

Finally, the video essay on constructive editing in our previous entry has attracted some compliments, for which we’re grateful. Its discussion of the Kuleshov effect has led some to ask us whether the several videos on YouTube are authentic footage of Kuleshov’s experiments. Alas, they are not, but Kristin and I don’t know their provenance. However, in Oksana Bulgakowa’s documentary on the Kuleshov effect, available on YouTube, there are some fragments of the surviving footage, starting at 4:28. Oksana has also helped complete the experiment by inserting a substitute for a missing shot. In addition, I’m reminded by Joe McBride and Katharine Spring of Hitchcock’s famous explanation of the Kuleshov effect, available on the DVD, A Talk with Hitchcock. An excerpt from that is posted on YouTube, probably illegally.

P.S. 11 November 2012: Jay Rath of Isthmus presents another, more optimistic account of the past and future of the Orpheum.

Inside Seattle’s Cinerama Theatre.

DIAL M FOR MURDER: Hitchcock frets not at his narrow room

Dial M for Murder (1954).

DB here:

This cut makes you say: Huh? Margo’s hand is shamelessly out of proportion and, judging by the men’s stares, we’re somehow looking through her torso.

Yet does anybody notice it? The cut reminds us that Hitchcock can get away with murder, cinematically speaking. Probably you didn’t need reminding, but even an inveterate Hitchcock watcher (I saw Dial M for Murder when I was about seven years old) can still be shocked by the old guy’s sheer bravado.

In 1979, Dial M was revived, and a restored version began a tour as a re-release, playing in 3D around the US and Europe. It ran in New York’s 8th Street Playhouse in 1981, and Kristin and I caught it in London at about that time. Most relevant to today’s entry, in September of 1981, it screened in a 3D retrospective at what was then called the Festival of Festivals, the earlier incarnation of the Toronto International Film Festival. According to Variety, the late-night show turned away a thousand people.

It’s good to report, then, that about thirty years later it returns to what has become one of the most important festivals in the world. Last night Dial M, muscled up in a digital restoration, screened to a sold-out house at TIFF. Preparing some remarks to introduce it, I found myself captivated once again by this curious project. Overshadowed by Rear Window, which was released later the same year, it now seems quite a daring movie, and not just because of this brazen cut. This newest restoration is very welcome, for it gives us an occasion to see what Sir Alfred can sneak past us.

Naturally, there are spoilers ahead, so if you haven’t seen the film you probably shouldn’t read past the next couple of sections.

3D: Device, demand, decline

During the 3D boom of early 1953, Warner Bros. was an enthusiastic participant. House of Wax, released in April, had proven a huge success; ultimately it would earn $9.5 million and become the top 3D release of the period. Jack Warner halted production from April through early July in order to retool the studio for the new process. Jack announced several pictures going into stereoscopic production, including Lucky Me, Helen of Troy, Them, and A Star Is Born. None of these wound up in the new format, but two others, Hondo and Dial M for Murder, did.

At summer’s end, 3D was starting to flag, largely, it seems, because screening the films posed so many problems. No system had been standardized, and different studios embraced various formats. Late in 1953, some interest perked up, chiefly because of Hondo and MGM’s Kiss Me Kate, but very soon the fad was over. In early 1954 most 3D releases played in their flat forms, and some were released only that way. In April, a month before Dial M opened, Variety ran a story headlined “3-D Looks Dead In United States.”

Dial M had been shot in summer of 1953. According to Bill Krohn, Warners was obliged by contract to wait until the original play had concluded its run, so the release was delayed until May 1954. By then even Jack had lost faith in the format. Dial M was the first Warners 3D picture that the studio permitted to be shown flat in first run, and most exhibitors took that option. 3D, Hitchcock reflected, was a nine-day wonder, “and I came in on the ninth day.” The picture still did reasonably well, earning $3.5 million–but Rear Window returned nearly three times that to Hitchcock’s new home, Paramount.

Wider, deeper, in color

Dial M for Murder confronted Hitchcock with three new technical challenges. Most obviously, the demand that the film be shot in 3D created problems with the bulky camera (“the size of a room,” Grace Kelly remembered, with some exaggeration). It couldn’t focus some shots as closely as Hitchcock would have preferred. The extreme close-up of Tony Wendice dialing, like the shot that starts the opening credits, had to be made with a giant telephone and a big fake finger, a piece of effects work that Hitchcock happily publicized.

Dial M for Murder confronted Hitchcock with three new technical challenges. Most obviously, the demand that the film be shot in 3D created problems with the bulky camera (“the size of a room,” Grace Kelly remembered, with some exaggeration). It couldn’t focus some shots as closely as Hitchcock would have preferred. The extreme close-up of Tony Wendice dialing, like the shot that starts the opening credits, had to be made with a giant telephone and a big fake finger, a piece of effects work that Hitchcock happily publicized.

Moreover, cinematographers were still figuring out how to judge each shot’s best convergence point (roughly, the way the two lenses defined the location of the screen’s surface) and interocular distance (the distance between the two lenses, mimicking the spacing of our eyes). Misjudging these factors could lead to distortions, such as making actors look closer together or farther apart than intended. Hitchcock worried about the “waste space” around his players in the initial footage the crew shot. In addition, directors had to be careful when the convergence point was set beyond foreground figures. If the figure was cut off by the frameline, a partial torso could be floating out at the audience. (The same threat can arise in today’s 3D films.) Interestingly, there are very few shots in the film’s first half that use a vertical frameline to bisect a character, and almost no over-the-shoulder reverse angles, which were, according to one cinematographer, risky.

Hitchcock’s concern for too much empty space might have been aggravated by the studio’s demand that the film be in widescreen. With the rise of CinemaScope, most studios had decided to release films in wide formats, and Warners was no exception. Dial M was released in 1.85:1.

Finally, although Hitchcock had shot in color before, this was his first outing with Eastman Color, a single-strip emulsion that eliminated the need for three-strip Technicolor. (Indeed, Eastman Color made several new processes, like 3D and CinemaScope, feasible.) But the new stock was somewhat less sensitive to light than Technicolor, and one advantage of shooting single-strip—the fact that you no longer needed the big Technicolor camera—was lost because of the 3D apparatus.

Faced with these obstacles, Dial M can look like a step backward. In Hitchcock’s interview with Truffaut, he agreed, claiming to have been “coasting, playing it safe. . . . I was running for cover again.” He had been planning a more personal project that fell through, and it was Warners that suggested he do Dial M, a property they’d acquired. After seeing the play, he agreed, but even while shooting, Grace Kelly recalled, he was already planning Rear Window.

At first glance, Dial M for Murder seems like the epitome of photographed theatre. Nearly all the action unfolds in the apartment of Tony and Margot Wendice, mainly in their living room. We get brief views of the bedroom, the terrace, and the hallway outside. Only about five minutes, or about 6 %, of the film take place on the street or in Tony’s club.

Both Frederick Knott, author of the play and screenplay, and Hitchcock failed “to take full advantage of the screen’s expansive powers,” opined Brog. of Variety. “As a result, ‘Dial M’ is more of a filmed play than a motion picture.” In talking with Truffaut, Hitchcock seemed to agree. “I just did my job, using cinematic means to narrate a story taken from a stage play.” In another interview he elaborated:

I think that’s the job of any craftsman, setting the camera up and photographing people acting. That’s what I call most films today: photographs of people talking. It’s no effort to me to make a film like Dial M for Murder because there’s nothing there to do.

Actually, I think there was a lot there to do, and Hitch did it.

Acknowledging the source

We could counter Hitchcock’s just-a-job-of-work argument easily by citing what he did with the famous attempted strangulation. Swann, alias Lesgate, has slipped out from behind the curtain. After waiting tensely for Margot to lower the phone, he wraps the scarf tightly around her neck and thrusts her onto the desk. She squirms, frantically grabs a pair of scissors, and stabs him in the back. Next, according to Knott’s stage directions:

Lesgate slumps over her and then very slowly rolls over the left side of the desk, landing on his back with a strangled grunt.

No viewer will ever forget the far more hideous death that the would-be killer suffers onscreen. After flopping over Margot, apparently dead, he snaps back to life spasmodically, as if jolted by bursts of electricity. His body yanks itself erect, his arms twisting helplessly as he tries to withdraw the blades, before he turns over and hits the floor . The impact drives the scissor blades further into his back. Hitchcock celebrates the moment with an Eisensteinian overlapping cut to a close-up of the scissors. He had a special pit dug, he proudly told a reporter, to make the lens flush with the floor.

So much for just setting up the camera and photographing the people acting. We could point to other alterations from the play, such as the strained drawing-room courtesies that frame the whole story. “Let me get you another drink,” is the film’s first line, as Margot and Mark pull out of a passionate clinch. At the end, nabbed, Tony offers to pour his wife and her lover a drink, and then asks the detective: “I suppose you’re still on duty, Inspector?” There’s also the peculiar mustache motif. The play text and the film dialogue mock Lesgate/ Swann slightly for growing one, but the film adds the mini-gag of self-satisfied Inspector Hubbard calmly combing his own mustache.

Fine as these isolated moments are, Hitchcock’s treatment is more thoroughgoing. He does, as he tells us, use cinematic means “to narrate a story taken from a stage play.” But those means are unusual and instructive.

Hitchcock had already experimented with plots confined to tight quarters–a lifeboat (Lifeboat, 1944) or a parlor and hallway (Rope, 1948). It’s plausible, as many critics have noted, that he tried the same thing with Dial M. But those earlier films seem more technically radical. You couldn’t ask for a much more cramped space than a lifeboat, unless you wanted a phone booth (which Hitchcock did consider for a film). Similarly, Rope‘s experiment with very long takes (it has only 11 shots) made it extraordinary for its day. From this perspective, Dial M can look like a retreat. It expands its range of action in modest ways, and it doesn’t try for a consistent long-take look. There are nearly seven hundred shots, and the average runs a little under ten seconds, quite normal for the period.

Yet limiting the action largely to the apartment wasn’t exactly taking the line of least resistance. In adapting a play, there’s always a temptation to open things up. Most plays include a great deal of action that takes place before the play’s opening scene, or in other locales offstage. In other words, the plot of the piece is highly selective and concentrated in both space and time, while the broader story—the sum of all the incidents that contribute to the action—is recounted or suggested on stage. Most film adaptations “ventilate” the original by dramatizing these scenes, as Brog. apparently would have preferred.

Hitchcock resisted the temptation to open out the play. Showing scenes that take place before the stage action (perhaps the theft of Margot’s handbag, or Tony’s stalking of the shady Swann/ Lesgate) would have lost the tight focus of the original. Moreover, we can gain an extra layer of interest when action is recounted rather than dramatized: we get both past events and present attitudes toward them. (In other words, sometimes we should tell rather than show.) Most intriguing, though, is Hitchcock’s comment to Truffaut that opening up a play “overlooks the fact that the basic quality of any play is precisely its confinement within the proscenium.” Hitchcock wanted “to emphasize the theatrical aspects.”

Hitchcock wasn’t alone. In the 1940s, several filmmakers were rethinking the problem of filming theatre, and they were exploring ways to bring out the “theatrical aspects” of the material. In a brilliant 1951 essay, André Bazin pointed out that filmmakers were now confident enough in their creative choices to adapt plays while acknowledging the pleasure of purely theatrical conventions. These films, he suggests, engage us by acknowledging the theatricality of theatre.

Bazin pointed to Olivier’s Henry V (1944), which begins in an Elizabethan playhouse and gradually moves its scenes to realistic settings. He mentioned as well Cocteau’s Les Parents terribles (1948), which, somewhat in the manner of Dial M, finds an equivalent for the play’s single-room set by expanding the film’s locale just slightly to take in an entire apartment. Other examples would include Welles’ Macbeth (1948), Melville’s Les Enfants Terribles (1950), and H. C. Potter’s The Time of Your Life (1948). Earlier in the decade, the obviously artificial sets and to-camera addresses of Our Town (1940) and Wyler’s handling of the parlor and staircase in The Little Foxes (1941) suggest a sort of para-theatre, cinema that supplements or amplifies stage conventions rather than trying to escape them.

That Hitchcock should join this trend toward new forms of filmed theatre is surprising. Earlier in his career, as a director nurtured by the silent movies and particularly American and German films, he had been an advocate of “pure cinema.” That meant, above all, editing and pictorial storytelling. Talky scenes were anathema. He wrote in 1937:

If I have to shoot a long scene continuously I always feel I am losing grip on it, from a cinematic point of view. . . . What I like to do always is to photograph just the little bits of a scene that I really need for building up a visual sequence. I want to put my film together on the screen, not simply to photograph something that has been put together already in the form of a long piece of stage acting.

Yet in 1948, he explained that he had yearned to film scenes in long takes.

Until Rope came along, I had been unable to give full rein to my notion that a camera could photograph one complete reel at a time, gobbling up 11 pages of dialogue on each shot, devouring action like a giant steam shovel. As I see it, there’s nothing like a continuous action to sustain the mood of actors, particularly in a suspense story.

He took much the same approach in Under Capricorn (1949).

Why does the montage-oriented director ten years later make two of the showiest long-take films in Hollywood history? I’ve suggested in an essay in Poetics of Cinema that there was something of a long-take contest among American directors in the decade after Citizen Kane. The competition was propelled partly by new equipment that permitted long, flowing camera movements. This “fluid camera” trend, as it was called in American Cinematographer, pushed ambitious directors toward shots that might run several minutes. Welles, Preminger, Minnelli, Cukor, Ophuls, Siodmak, Joseph H. Lewis, and several other directors tried their hands at virtuoso long takes, and in some cases those were applied to stage adaptations. Welles stretched one shot in Macbeth to the length of a whole camera reel.

With Dial M, Hitchcock largely gave up the long take (though a few shots run a minute or so), but he tried something else. He offered a form of filmed theatre that has its roots in silent moviemaking, and he explored ways to transpose it to 3D cinema.

A chamber play

Sylvester (1924).

In fall of 1924 Hitchcock went to Germany, where he toured the magnificent Ufa facility and became acquainted with the work of the industry’s outstanding creators, especially Lang and Murnau. Most writers have emphasized his acquaintance with the Expressionist films of the early 1920s, and he sometimes mentioned his admiration for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. But he also praised Lubitsch, who was no Expressionist, and when asked about his major influences, he answered, “The Germans. The Germans.” It’s not farfetched to assume he was aware of another trend in local production, the one known as Kammerspiel.

The Kammerspiel, or “chamber play,” emerged in German theatre, and the film equivalents appeared in the early 1920s. The Kammerspiel film typically confined itself to a few settings and emphasized psychological conflicts among a small cast of characters. Surprisingly, the major instances, such as Shattered (Scherben, 1921), Backstairs (Hintertreppe, 1921), and Sylvester (aka New Year’s Eve, 1924), weren’t adapted from plays but were original scripts by Carl Mayer. The most famous Kammerspiel film, which Hitchcock would likely have seen during his visit, was Der letze mann (aka The Last Laugh, released December 1924), directed by F. W. Murnau. Extensive tracking shots were rare in most silent movies, but Murnau built his film around them. He and Mayer, who had scripted Der letzte Mann, came to America and there made Sunrise (1927), famous for its elaborate camera movements.

Another major director pursued the chamber aesthetic well beyond the silent cinema. Carl Dreyer had made a Kammerspiel film, Michael (released September 1924), and he carried the lesson of the trend back to his native Denmark with The Master of the House (1925), an adaptation of a popular play. Like Dial M, the film concentrates on one locale—a family’s apartment, built out of hundreds of detailed shots of the actors and sets, with almost no camera movements. Later, Dreyer would apply the Kammerspiel aesthetic to other play adaptations, Ordet (1955) and Gertrud (1964), but presented in long, gradually unfolding tracking shots.

With a Kammerspiel aesthetic, you get something fairly distinct from what we think of as filmed theatre. The baseline prototype of filmed theatre is the PBS/ Metropolitan Opera model: a live performance captured by several cameras. The cameras don’t really penetrate the space; they give us different angles and shot scales (usually thanks to different lens lengths), but we don’t have a sense that the camera is in the thick of things. A more flexible form of filmed theatre occasionally inserts the camera among the performers, as with certain shots of Wenders’ Pina. But for Hitchcock, Dreyer, and the chamber-film aesthetic, the space of the “stage” becomes completely permeable. The actors are stuck in the set, but the camera can go anywhere there. The camera can scan the space, jump below or above it, even rotate. The result feels both theatrical and cinematic—a concentrated stage piece heightened by the tools of cinema.

Locked inside these four walls

Films in the Kammerspiel mode find drama in intimacy and routine. Sometimes called “doorknob cinema,” these films draw suspense out of prosaic activities: crossing a room or simply waiting for someone to come through a doorway can become major turning points. Dial M is doorknob cinema par excellence; a latch comes close to being a character. But the director’s problem is to dynamize this enclosed space, to make furniture and entryways and trips back and forth across a parlor engrossing. So it’s a question of how to film it all.

The proscenium tradition of Western theatre pretends that the setting’s fourth wall has been removed. We look through it to the action. PBS-style canned performances preserve this convention, keeping us on the auditorium side. But Kammerspiel-style filming doesn’t adhere to this. Not only does the camera shoot from angles that would be unavailable to a spectator in a playhouse, but it may show all four walls of the set. Dreyer’s Master of the House does this, freely cutting from one side of the action to another, so rigorously that we could sketch a complete floorplan of the rooms.

Dial M does much the same. Consider that bar table against one wall. It’s shown straight on in many shots, but at least once the drinks are shown in the foreground (with striking 3D saliency) and behind Margot and Mark we see the other wall behind them, the one “through which” we’ve seen action before.

Why go to the trouble of showing the fourth wall? It supplies visual variety while expanding the play in a way that is at once “theatrical” (the space is still enclosed) and “cinematic” (the camera can go anywhere). Allowing a fourth wall also permits more complex staging effects. Characters can now make a circuit around the entire set. This is notable in Dreyer’s late films, when the character’s walk is covered in a single tracking shot, as if the set’s four walls have been ironed out on the screen.

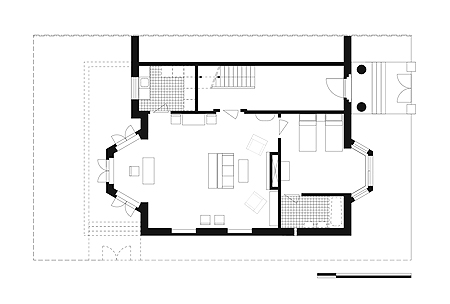

Hitchcock does the same sort of thing through cuts. In one scene, we follow Tony as he finally takes control over Swann, convincing him to kill Margot. Here the showing of the fourth wall can mark off a privileged portion of the scene. To get a sense of how this happens, we can look at a plan of the apartment provided by Steven Jacobs in his stimulating book The Wrong House.

The living room is the biggest space, with the kitchen (never shown) and hallway above it. To the right of the living room are the bathroom (never shown) and the bedroom. The street is at the far right of the diagram, the terrace and garden at the far left.

The living room is the main arena of action. In the left area are the French windows, with Tony’s desk and desk chair in the alcove. The drinks bar, flanked by two chairs, stands along the uppermost wall. Adjacent to the right chair is the crucial main doorway. In the center of the room, facing the fireplace at the right, is the sofa and coffee table, with a narrow table running behind the sofa. Two wingback armchairs are angled alongside the fireplace. On the long bottom wall are bookshelves, hanging pictures, two chairs, and a china cabinet (not pictured).

During most of the film, we are oriented to the apartment from camera positions facing the wall with the drinks bar and the doorway (the top area of the floor plan). At a crucial passage, however, Hitchcock takes us around the entire living room, clockwise.

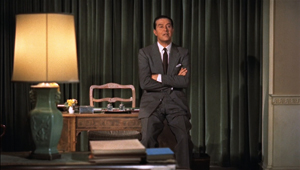

Tony has been unveiling how much he knows about Swann’s crimes. In this movie, the desk is the place of power, where both the phone and Tony’s account book are. Starting at the desk, Tony builds up the pressure. He moves along the familiar side of the room to confront Swann as he wipes the glasses.

He controls their conversation, even when he pauses to sit down and face a looming Swann.

These shots get Tony to a midway resting point. He explains that he’s already framed Swann as the man blackmailing Margot. This pushes Swann into an angry sulk. Hitchcock uses Swann’s static profile as a pivot, in order to switch camera positions 180 degrees. As Tony continues to squeeze Swann, we see a corner of the fourth wall we just more or less occupied.

Call this the “stick” part of the sequence. When Tony proposes a carrot—a thousand pounds in exchange for killing Margot—we follow him from the new side we’re on. Swann turns uneasily away, and a slight change of angle accentuates his shift.

As Swann edges to the fireplace, Tony strolls rightward, passing a bookcase and the china cabinet. When he gets to his desk, he reaches into a drawer.

“You can take this hundred pounds on account.” He tosses the money across the room, and the camera pans with it across the fourth wall. The sheaf of bills lands in the wingback chair Tony had relaxed in earlier.

Swann doesn’t touch the money but advances to the desk to check Tony’s claim that the bills can’t be traced. So we make another half-circuit of the room.

Now we’re back in the zone in which the shot started. When Tony says that the murder will take place “approximately where you’re standing now,” Hitchcock cuts to a low-angle shot of Swann, starting. (This is one of many examples gainsaying the idea that a low angle confers power on an individual.)

This entire passage, the culmination of Tony’s efforts to recruit Swann to his cause, is rendered in a series of fairly short shots, not long tracking movements. And indeed the “wild wall” with the bookcase would have been much more difficult to manage in a single take. Probably that’s one reason Rope doesn’t show us its fourth wall.

After this patient, quietly bravura passage, Hitchcock starts a new one, this time from a high angle.

The orientation, one we haven’t seen before in the film, marks a fresh phase of the action: it’s the first of many rehearsals and replays of the killing. This section of the scene gains force by its contrast with earlier low-angle shots and the steady circuit we’ve made of the living room.

Echoing frames

Naturally, Hitchcock dynamizes Knott’s play by means that we’ve seen in other of his films. There are passages of subjective cutting, in which we’re given the optical point-of-view of a character. Early in the film POV shots are assigned to Tony, but as Margot gets drawn into his trap, Hitchcock gives her subjective shots too. The pivot comes when during Hubbard’s questioning. Tony steps out from behind the Inspector and her glance flicks to check his expression. She’s telling the lie he coached her to tell. Our alliance starts to shift to her–and to Hubbard, through whose eyes we’ll see what happens in front of the house at the climax.

At the climax, when Inspector Hubbard brings Margot out of prison to solve the case, a comparable peekaboo dance takes place through her vision, with Tony replaced by Mark.

There’s also the remarkable passage of mental subjectivity reminiscent of 1940s montage sequences, in which Margot’s trial and condemnation are compressed into abstract shots showing her as if facing the judge (above). These images again at once open up the play a bit and keep faith with the tightly circumscribed premises of the film. As Hitchcock explained to Truffaut, he handled the court proceedings in such a stylized fashion because shifting the action to another concretely defined space would have destroyed what he’d built up. “People would have started to cough restlessly, thinking, ‘Now they’re starting a second picture.'” The passage also reinforces our emotional attachment to Margo that was initiated during Swann’s attack.

Keeping the action within one set also allows Hitchcock to exploit a tactic that’s common to Hollywood films but that seldom gets such a workout—the repeated setup that carries echoes of earlier actions. I’ve supplied examples in an earlier entry, on Nolan’s The Prestige, but needless to say Hitchcock gives us a master class in reiterated or rhyming setups. The several tours of the apartment activate different props and zones while also highlighting key areas, such as the desk and the door that will come back later. When you have only a few sets, you can layer the audience’s sense of the scene’s progress by calibrating your camera positions to evoke earlier shots of the same bit of space.

For example, when the police are investigating Swann’s death, a high angle ironically echoes Tony’s rehearsal of the murder plot (above). Another straightforward instance is seen in the low angle on Tony in the wingback chair. We first see it when Tony offers his purring explanation of how he’ll frame Swann (above). That shot is recalled quite precisely when, after having adjusted to Swann’s death, he relaxes in the chair after setting up the framing of Margot.

The hallway area receives more prolonged development, with the carpeted stairs becoming more prominent as the film proceeds.

In the second shot above, Hitchcock denies us what any other director would show: a closer view of Tony slipping the key under the carpet as he’s talking casually to Margot. It’s a token of respect for our intelligence, I think. He knows we’re watching Tony’s hand, even in long shot.

Not until Swann arrives do we get the variant of the framing that will be modified at the climax, when Tony comes back from the police station.

Both of these shots play out as parallels and variants, as each man reaches for the key under the stair carpet.

A similar framing presents the grisly aftermath of the murder attempt, contradicting Tony’s confident patter about the plan.

Later, the key framing shows Inspector Hubbard setting the trap for Tony, in a shot recalling the trap Tony set for Margot. When Tony is caught and tries to escape, Hitchcock cuts to the prime orientation to show his path barred.

Of course, filming several shots from the same general setups can save time during production, but shrewd directors turn those repetitions to narrative advantage. In this case, they let Hitchcock have his cake and eat it too: he can stay concentrated on a single set, but he can create a web of associations among different phases of the action. The narrow rooms of Knott’s play are transformed by cinema.

Superflat?

The widescreen format forced upon Hitchcock may have been another source of his worry about “waste space.” He used lampshades and other items of furniture to balance the 1.85 compositions. More important, his use of 3D has long seemed rather conservative. Is it?

There are almost no instances of objects popping out from the screen surface; the famous example is Margot’s hand plunged out and toward the scissors on the desk during Swann’s attack. The space is discreetly layered, as when the bottles on the bar table or the bedstead moved to the living room command the foreground of shots. On the whole, Hitchcock follows both advice and custom in using the frame as a window: the depth is on the other side of the screen, tapering toward the distance. This was recommended practice at the time, and still is today.

More important, 3D Westerns like Fort Ti and Hondo and 3D musicals like Kiss Me Kate have settings stretching into the far distance, so you can show an extreme range of depth behind the screen/window. But if you’re shooting an apartment set, you don’t have much distance to play with. The result is a “shallow depth” that is at odds with a central trend of 1940s cinema and many 3D productions of the day.

Like other directors working in the 1940s and early 1950s, Hitchcock sometimes embraced tight depth compositions with big foreground heads or objects. Here are shots from The Paradine Case (1947) and I Confess (1953).

Color filming made shots like these more difficult, as the film speed didn’t allow the lenses to be stopped down so far. Accordingly, for Rope and Under Capricorn, Hitchcock either spread his actors out clothesline-fashion or kept the foreground far enough from the lens so that the depth of field could be managed.

3D added more constraints. Fox cinematographer Charles G. Clarke recommending putting nothing very close to the camera and relying on 50mm lenses for medium shots (rather than the wider 35mm ones common in 2D black-and-white filming). Hitchcock’s cinematographer Robert Burks had shot Hondo and is said to have worked uncredited on House of Wax, so he was aware of the emerging 3D conventions. But the relatively flat spaces of Dial M yielded depth shots that don’t spread its faces across great distances. In many of the shots shown above, you can see that when figures are arrayed in some depth, the foreground is fairly far away from the lens. We have a convenient comparison in the opening of Shadow of a Doubt (1942) and a late scene in Dial M.

In the later film, Milland in the foreground is further from the lens, and Cummings is closer to him than the landlady is to Joseph Cotten. In most shots in Dial M, the space of the set is shallower, and the characters are typically packed closer together, than in the deep-focus films of the 1940s.

Paradoxically, then, it was harder to get aggressive depth compositions in 3D films than in 2D ones. But Hitchcock seems to have taken advantage of the shallow space of the Wendice apartment to concentrate on his actors, often isolated in single shots rather than the jammed frames of the 1940s. Given the wider frame, his compositions may seem bland, and sometimes they display the waste space he deplored. Still, his approach throws nearly all the emphasis onto the “theatrical” features of line readings, postures, gestures, and facial expressions.

Moreover, seeing the 3D screening at Toronto right after seeing digital 2D copies, I was struck by how many planes are out of focus in the 3D version. Presumably the 2D transfers have always been taken from one or the other of the dual-camera negatives. The result is a harder-edged image than what 3D creates with its staggered overlap of images.

Focus is extremely selective in the 3D version, with often only a face or even a cheek crisp and everything else significantly softer. For example, it’s not easy to discern in the 2D versions that in 3D, Margo’s face is the only plane in focus in the first shot below; both the bouquet and Mark, as well as everything else, is not as sharp. Later, Hitchcock makes the bedside clock salient by letting it be the only item fully in focus, but I don’t think you’d know that from the harder-edged image on display on the DVD and the download version.

Unlike the 1940s deep-focus style, then, Dial M‘s color 3D puts very few planes in focus, accentuating the shallowness of the space of the scene. The foreground furniture and lamps would be distracting if they were in focus (as, say, they tend to be in The Ipcress File). Like a silent-film director practicing the “soft style” of the 1920s, Hitchcock uses 3D to surround his characters with cushiony, vaguely defined planes.

I’m tempted to see Hitchcock flaunting shallow space in one of the more remarkable moments in Tony’s murder rehearsal. As we’ve seen, high angles trace Tony’s path around the parlor. They also highlight the suitcase that hasn’t been visible in earlier shots, what with all the low angles. But when it’s necessary for Tony to show Swann where he’ll hide the key, we get something quite unlike the rest of the film.

Most directors would either shoot the scene from inside the apartment, framing it in the doorway (as the set is filmed when Hubbard reveals the lost key), or from some vantage point in the hall, probably from rather close to the carpet. Instead we get a cut from the master-shot high angle straight in to another high angle, but taken with a much longer lens.

Peering through the chandelier at Tony’s ploy, riveting our attention on the key, this shot emphasizes depth in a way that few other shots in the film do. Yet the long lens has the effect of squeezing the planes together, negating the effect of 3D and relying on monocular depth cues like distance and the out-of-focus chandelier. It might as well be an axial cut out of Kurosawa.

This image, like the two shots I started with, the implausible and underhanded cut showing Margot displaying her key to the three men, reminds us that Hitchcock is always ready to tell stories of the unexpected, in unexpected ways. And these ways celebrate the ability of film to transform whatever it touches.

Years after Dial M, Hitchcock may have soured on the theatre-driven phase of his career. Yet Wordsworth’s sonnet in praise of sonnets celebrates what you can accomplish within a “scanty plot of ground.” By embracing the theatrical trappings of Dial M for Murder, Sir Alfred does more than tell a suspenseful tale. He fastidiously demonstrates that cinema’s power is unpredictable.

At Toronto, the digital version of Dial M was shown in the original 1.85:1 aspect ratio. The 2004 DVD employs a 4:3 ratio. The version circulating on iTunes HD rental and the 3D Blu-ray disc announced for October, are in 1.77. I’m drawing my frames from the 1.77 version, the closest I can get to the original release.