Archive for the '3D' Category

As the summer winds down, is 3D doing the same?

Something to do with 2D to 3D conversion for Conan the Barbarian. (See 3DLiveFlix)

Kristin here:

Just over a month ago I posted “Do not forget to return your 3D glasses,” an entry suggesting that on average theatres were making less money from 3D versions of films than 2D versions. I made two basic points. First, claims that films were making, say, 60% or 45% of their box-office gross from 3D showings were inaccurate. Only the extra fee charged at 3D screenings was for 3D; the rest was for the film as such. By that logic, something closer to around 10% was actually being earned by 3D (assuming people who went to see a film in 3D would probably see it in 2D if necessary.)

Second, my point was that if a film’s box-office percentage from 3D screenings was lower than the percentage of theaters in which it was being shown in 3D, then the exhibitors in those theaters were making less money than exhibitors showing the film in 2D. For most films that have come out this summer, starting in May, the percentage has been distinctly lower.

Wasn’t this supposed to be the summer of 3D?

With the summer movie season drawing to a close, I thought I would summarize some recent developments. These tend to suggest that the decline in the popularity of 3D in the U.S. market has continued. Indeed, a recognition of that decline has started to have an impact on the effort within the industry to pressure theaters into showing films in 3D.

During August I noticed for the first time that trade-paper and online sources are becoming more explicit about saying that 3D is no longer as big a draw as it used to be. Reporting on August 13, the day after the release of Final Destination 5, Variety stated, “Though roughly 89% of its screens are in 3D, and 217 are in Imax, ‘Destination’ isn’t expected to see much of a boost from the format given waning interest in 3D. Optimistic B.O. pundits have the film topping out at $21 million through Sunday.”

In fact, Final Destination 5 grossed over $24 million. That was, however, the lowest opening-weekend gross of the franchise. It made about 75% of its gross from 3D screenings, which occupied 80% of locations. That’s better than most 3D films of the summer in proportion of income to screens, but still not great. Its comparatively good performance in 3D suggests that genres like horror still tend to draw the spectators most interested in 3D. Final Destination 5 came in third after two non-3D films, Rise of the Planet of the Apes and The Help, both of which did much better than expected.

The weekend’s other 3D film, Glee the 3D Concert Movie, did so badly that the trades didn’t bother to report its percentages of 3D screens in proportion to income. Its box-office gross put it at #11 on the chart, earning less than $3000 per screen.

The following weekend, August 19-21, saw Rise of the Planet of the Apes and The Help switch slots on the chart, with The Help becoming the first film since January to rise from a #2 opening to the #1 rank—a position it held this past weekend as well, experiencing a low 28% drop despite East Coast theatre closings due to the hurricane.

That same weekend saw three 3D films do lackluster business. Of those, Spy Kids: All the Time in the World did the best, coming in at number 3. About 44% of its income came from 3D, which fits into the 45% level typical of 3D films this summer. Interestingly, though, only 41% of the locations where the film was shown had it in 3D. Variety’s report on Saturday remarked, “The summer’s new norm is to make about 45% of grosses off 3D screens, though that figure could be even lower this weekend with so many pics vying for 3D play and so many of ‘Spy Kids’ engagements opting for 2D.”

There are two implications here. First, if fewer theaters show a film in 3D, the ones that do will make more money, since those moviegoers interested in seeing a film in 3D will converge on that smaller number of theaters. There apparently are not enough such moviegoers to justify having 60% or more of theaters showing 3D. Second, given that four 3D films were debuting that same weekend, theater owners opted to show the film aimed at young children in 2D. We know that there have been complaints that children don’t like wearing the glasses and that parents don’t like shelling out extra fees to take a whole family to a 3D screening. The strategy worked, which again suggests that genres aimed at teenagers might provide the home for 3D, if it survives long-term.

Don’t worry, that includes the whole family. (Just kidding! It’s actually a ticket to last year’s “OnHollywood” trade summit, where 3D was discussed.)

But the teenage-targeting assumption didn’t work out well for the two other 3D debuts of that weekend. Conan the Barbarian showed in 3D in 71% of its locations, but only 61% of its gross came from those locations. The figures were almost identical for Fright Night. Perhaps the two films split the teenage audience, to the detriment of both. Glee fell off 69.4% in its second weekend, to an average of less than $1000 per screen.

The weekend of August 19-21 saw six 3D films in the top 11. (I list 11 rather than 10 because the 11th was the summer’s most successful film and a 3D item, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2.) The 11 were, in order (3D films in bold): The Help; The Rise of the Planet of the Apes; Spy Kids: All the Time in the World; Conan the Barbarian; The Smurfs; Fright Night; Final Destination 5; 30 Minutes or Less; One Day; Crazy, Stupid, Love; and Harry Potter. Of those six films, only two, Harry Potter and The Smurfs, made it to number one—for only one week each, remarkably.

Still doing well abroad

The big Hollywood studios continue to defend 3D as a financial strategy, since films made with the process continue to clean up in most foreign territories. Even though the percentage of 3D box-office income has fallen to a fairly consistent 45% (apart from the occasional genre film), it still provides about 60-70% of the international gross. (Unfortunately percentages of theaters showing 3D films aren’t given in such reports.)

Variety’s Andrew Stewart helps explain how some foreign markets encourage 3D viewing:

To some degree, the divergence can be chalked up to a matter of preference — some cultures just like 3D more than others for reasons that can’t be quantified, and big-budget f/x spectacles continue to draw big auds overseas — but there are also some subtle differences in local pricing models that provide insight to studios and exhibitors eager to see 3D pay off on its promise of enhanced B.O. takings.

Some notable factors: Many international markets temper 3D upcharges with discount play periods. China has half-price Tuesdays. In Germany, “Cinema Day” brings a steep midweek price drop to matinees. And some territories even charge less for 3D pics that have shorter running times. In many countries, premium ticket prices for 3D are further mitigated because moviegoers are encouraged to buy their own reusable glasses.

[…]

Some Japanese exhibs ease 3D ticket prices by charging less to those who bring their own glasses. Dolby controls most of the Japanese 3D market, and in March, the company started offering reusable 3D glasses for $12 per pair. In Europe, RealD sells its reusable glasses at concession stands or the ticket window for about E1, saving auds the repeated expense.

But if theaters attract customers by giving discounts or waiving fees for those who bring their own glasses, how long can the high proportionate income from 3D hold up? Sales of glasses benefit the technology companies, not the theater or studios, and eventually the market will be largely saturated.

So far 3D is holding up well in most foreign markets, but there is one exception. In Spain, where the 3D premium averages a whopping 37%, Transformers earned 49% of its national gross from 3D, Pirates of the Caribbean 41%, and The Smurfs 39%. Variety blames the sag on 22% unemployment and “rampant piracy.” But unemployment and piracy aren’t unique to Spain by any means.

And foreign markets got into 3D exhibition a bit later than North America did. There’s nothing to say that ticket premiums and the decline in the novelty value of 3D won’t start affecting international exhibition eventually.

A certain lack of confidence

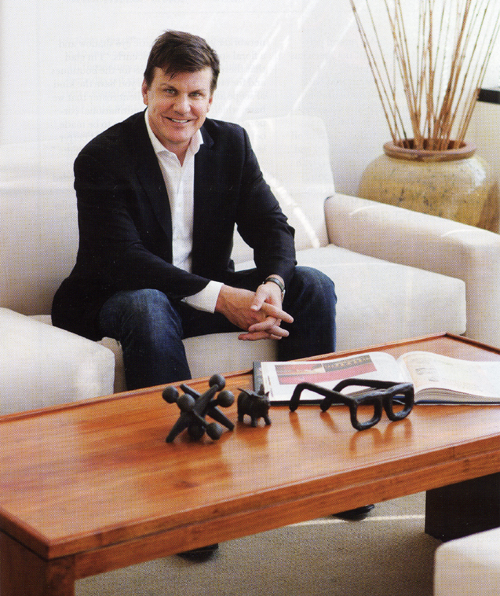

The August 12 edition of The Hollywood Reporter revealed that RealD’s “stock has plunged 60 percent since reaching a 52-week high in June as U.S. audiences seem to tire of the format.” Now that’s serious. Two weeks later, in the August 26 edition, a smiling Michael Lewis, the firm’s CEO (below), was given a two-page spread with an interview where he explained why he thought Wall Street was overreacting. (These references are to the print edition; online they’re behind a pay wall.)

Clearly, it was an overreaction. We had record earnings. We’re a relatively new company, and as time goes on we’ll prove the model. It doesn’t really matter if a film does 40 percent or 50 percent; we just believe this is a transformative event like the Internet and the personal computer. All visual displays are going to get better, and we’re really well positioned. Over time, Wall Street will figure that out.

That’s a remarkable claim. Many of us might say, “I don’t know how I got along before computers” or “before the Internet.” How many people would really say “I can’t imagine what we did before 3D came along”? This is hardly a transformative event on a scale even vaguely close to those two technologies. I can easily get along without seeing a film in 3D, but I would never go back to an era when endnotes didn’t rearrange themselves automatically  when you moved or added a reference in your text. Think, too, how profoundly computers and Internet have affected the world financially, and then compare that with the impact of 3D.

when you moved or added a reference in your text. Think, too, how profoundly computers and Internet have affected the world financially, and then compare that with the impact of 3D.

Lewis also seems disingenuous when he claims that whether a film does 40% or 50% of its business in 3D “doesn’t really matter.” It certainly matters to the local multiplex owner who sees more people going into an auditorium showing a movie in 2D than another auditorium showing it in 3D. It matters to the distributor who gets a cut of the take and to the studio that gets the remainder–and had to pay extra to begin with to make the film in 3D.

He may be right, though, that Wall Street overreacted. The interview includes some impressive figures. RealD controls roughly 85% market share of the domestic 3D box office. (Apart from selling its projection systems, special screens, and glasses to theaters, RealD gets a licensing fee averaging fifty cents for every ticket sold.) Within the U.S., it has 10,300 screens in 2,500 locations; abroad, the number is 7,200 screens in 2,300 locations. The firm’s 2011 fiscal-year revenue was $246.1 million, up 64% from the previous year. Its fiscal-year 2011 gross profit was $67.7 million, up 633%. This is flashy–though such growth came during the post-Avatar era when theaters which had missed out on the film’s bonanza were buying 3D equipment at a good clip, and more 3D films were in the pipeline. (Lewis says 2011 will see forty 3D films released.) If theater conversion is nearing saturation point and 2D screenings are outdrawing 3D ones, though, this summer may mark the end of the expansion for companies like RealD.

Lewis doesn’t exactly win me over either with his notions of what to do with 3D. He’d like to convert Singin’ in the Rain into 3D. That and The Love Bug. You know, the great classics. Plus he has a rather peculiar idea of Avatar‘s place in film history. Asked what Cameron’s film did for the business of 3D, Lewis responded: “It legitimized it. It was the Citizen Kane of our medium. After Avatar, I finally didn’t have to go into a meeting and explain why this was going to be important for our industry. The numbers spoke for themselves.” No doubt Avatar‘s phenomenal box-office success made exhibitors who had not yet installed 3D equipment keen to do so. But Kane was in fact not a financially successful film. No one could say of it, “After Kane, I didn’t have to go into a meeting and explain why deep focus was going to be important for our industry. The numbers spoke for themselves.” Both films are undoubtedly historically important, but there’s really very little comparable about them.

Auteurs to the rescue?

Speaking of legitimacy, Lewis is looking forward to the releases of Martin Scorsese’s Hugo in November and Ridley Scott’s Prometheus next year. On August 12, the Wall Street Journal ran a long story by Michelle Kung on how a trio of Movie Brats are about to reveal their first 3D films. Hugo is scheduled for November 23, Steven Spielberg’s The Adventures of Tintin for December 23, and Francis Ford Coppola’s Twixt premieres in September at the Toronto Film Festival.

Spielberg’s popularity among a broad range of audiences remains intact, though whether Belgian import Tintin can win American spectators’ hearts remains to be seen. Whether Scorsese and Coppola, beloved of audiences of my generation, will prove the final boost that 3D needs is up for grabs. Coppola seems a particularly unlikely auteur to pin one’s hopes on. Twixt, a low-budget horror film, has only five minutes of 3D footage, and it has yet to find an American distributor. According to Anne Thompson’s blog, the director “first showed the film to distributors in Los Angeles Wednesday night [i.e., August 24]. Unless he gets a rich offer, Coppola will likely four-wall the film himself; he’s looking to sell video rights.” Today’s Variety reports that Pathé has picked up Twixt for “international sales and distribution in France.” That doesn’t seem to settle the question of a U.S. release.

A more likely shot in the arm for 3D would seem to be Peter Jackson’s Hobbit film, being shot even as I type. It should appeal to teenage 3D buffs and just about everyone else. But the first part is not due out until December, 2012. I suspect that the degree to which 3D will penetrate the theatrical market will be known by then.

The article quotes Jeffrey Katzenberg, who years ago claimed that every screen would eventually be converted to 3D, as saying “You now have some of the greatest filmmakers in the world stepping into the format to tell their stories.” Scorsese has gamely stepped up to the plate, commenting that if 3D had been around when he made Mean Streets or Taxi Driver or Raging Bull, “those stories would have fit in perfectly in 3-D.” It’s a bizarre thought, but maybe he’s serious.

Kung provides some interesting figures. It’s difficult to get a sense of how many people are opting to see 3D films in their 2D versions. Usually the comparison is made in terms of box-office gross rather than number of tickets. But the author says that 57% of people who saw the final Harry Potter film this summer opted for 2D, which seems a pretty significant figure. She also notes the falling stocks of RealD and other 3D firms:

“Consumers are pushing back,” says Richard Greenfield, an analyst at brokerage firm BTIG. “They’re tired of 3-D, both from a price perspective and from a physical-comfort perspective.” He adds that consumers have come to a key realization: A bad film in 3-D is still a bad film.”

Kung says that about 30 new 3D films are due for release next year. If Lewis’ figure of 40 for 2011 is accurate, that means a notable drop in planned 3D productions for the short term. Possibly it’s a temporary one, but perhaps studios are beginning to think that the extra returns from their share of those ticket premiums aren’t worth the cost and effort. If 57% of Harry Potter‘s audience opted for 2D, then perhaps an increasing number of theater owners are refusing to book 3D films from the distributors.

That figure of 30 releases doesn’t include the announced 3D conversions of Titanic and the Star Wars series, which may or may not be ready for release next year. The rumors of such conversions for these and other popular items like the Lord of the Rings film have been circulating, but precious little information on how, when, and where these will eventually reach theaters has been forthcoming.

As I’ve said in my previous posts on 3D, I don’t see any reason why the format would necessarily disappear. Once the match of number of 3D screens and number of moviegoers who want to see 3D movies reaches a reasonable balance–which at this point seems to mean a significant number of current 3D screens reverting to 2D–both formats will make money and 3D will continue, especially for blockbusters and teenage-oriented genre films. But the idea that studio and company executives can simply dictate that the entire public should embrace what is, after all, a relatively superficial technology added onto an already stable and successful product seems overweening and implausible. This summer’s movies have seemingly reflected the public’s more realistic attitude.

And now, enough of 3D. Unless something dramatic happens between now and when Hugo comes out, I shall hold off writing on the subject until we see what happens during the holiday season, when the format faces its next big test.

P.S. August 31: The Fandor blog has a post by Alejandro Adams, a filmmaker who manages a multiplex in northern California. He reports that until recently, studios demanded that all 3D films be shown only in 3D, no matter how many screens were available. Adams reports that this summer: “We’d just opened Captain America ‘over/under,’ meaning that we were offering two 2D shows and three 3D shows in a single auditorium. This was the first time any studio had allowed us to restrict the number of 3D shows. When I checked the grosses after opening day, I was alarmed. We sold twice as many tickets for 2D as 3D. As we’d never booked a 2D engagement of any film available in 3D, I’d never seen this disparity up close. The fact that we were permitted to over/under Captain America in 3D and 2D is itself a distressing development—are the studios suddenly willing to admit they didn’t hit the jackpot with the 3D craze? Are they going to start phasing out 3D so soon after we went to the trouble and expense of making our projectors and screens compliant with their demands?”

Adams calls this a “distressing development,” being a fan of 3D, both for his own and his children’s enjoyment. If my hunch turns out to be correct, they will still have the 3D option, but others will have access to 2D screenings.

RealD’s Michael Lewis. Hmm, those glasses do look a bit clunky. (Photo by Peden + Munk)

Do not forget to return your 3D glasses

(Yours for $11 in theaters equipped with RealD systems, but you don’t get the pouch they came in at the opening midnight screenings)

Kristin here:

As 3D really took hold in the wake of the release of Avatar in December 2009, we got used to hearing that roughly 60% of a blockbuster’s income came from 3D. This summer the figure has hovered around 40%. Both figures are highly misleading. How much does 3D really bring in?

Yes, 40% of the total amount for almost all big 3D films this summer was for tickets sold for 3D screenings. But looked at another, more realistic way, 3D films as such made far less than that for their makers and the theaters that showed them.

That’s because a lot of the people buying tickets to see a film in 3D probably would have gone to see it if it had been strictly 2D. That, is, 3D itself is probably not luring in many new viewers. If every person buying a 3D ticket would refuse to see the film in 2D, then, yes, the figure would be 40%. I’m sure a small percentage of people are lured to see a given title only because it is in 3D. There’s no way to know how many, however, so let’s stick to the facts we do know.

The basic fact is that the money brought in by a film made in 3D only amounts to the supplement paid by the spectator beyond what he or she would have paid if the film were in 2D. Let’s assume that the supplement is $3 and that a 3D admission costs $12 and a 2D one $9. Let’s also assume for the sake of argument that everyone who saw the film in 3D for $12 would pay $9 to see the same film if it were only available in 2D. (In reality, there’s also evidence that 3D keeps some people away from a film altogether if they don’t have access to 2D screenings. I’ll assume these two groups, the 3D enthusiasts and the 2D hold-outs, cancel each other out.) Removing the $3 supplement takes away 25% of the ticket price. So what the 3D process as such really adds to the box-office total is 10% (that’s 25% of 40%). To put it another way, $9 of the $12 for the ticket is just for the film qua film, the rest is for its being in 3D.

In addition, the costs for the glasses and any extra labor they entail have to come out of that $3. I don’t know what such costs are, so I’ll leave those expenses out of the calculations.

Consider the opening weekend of Captain America, which grossed $65.7 million, 40% of which came from theaters equipped with 3D. But it’s really 10% by my reasoning, so it’s not $26.3 million that 3D generated, but $6.57 million. Assuming further that it costs about $30 million to make a film in 3D or convert it to 3D in post-production, Captain America would have to run in the U.S. market for around four weeks with no decline in attendance to break even on 3D. But most films decline on their second weekend, unless they open in more theaters or have terrific word of mouth. Even The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, which had lots of repeat business, declined 19% on its second weekend.

Of course, the popularity of 3D films is holding up better abroad than in the domestic market–so far. Still, we have to remember that only about half of the worldwide box-office receipts make their way back to the studios. That seems to imply that a film would have to gross $600 million internationally to break even on the addition of costs for 3D. ($300 million going to the studios, roughly 10% of which is paid for by 3D supplements=$30 million.) Some films do gross that much. Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, Transformers: Dark of the Moon, the final Harry Potter installment have passed that mark this year. It’s not common, though.

Naturally if a film takes in as much as 60% of its box-office from 3D screens, as Transformers: Dark of the Moon did, 15% of the costs of 3D will be paid for by the process.

How consistent is the trend?

Let’s look at the major 3D films out so far this year in terms of percentages of gross vs. percentages of theaters:

Film: Release Date (% of BO from 3D / % of locations showing 3D)

Green Hornet: January 14 (69% / 75%)

Gnomeo and Juliet: February 11 (58% / 60%)

Rio: April 15 ( 58% / 68%)

Thor: May 6 (60% / 69%)

Pirates of the Caribbean: 4: May 20 (46% / 66%)

Kung Fu Panda: 2 May 26 (45% / 69%)

Green Lantern: June 17 (45% / 71%)

Cars 2: June 24 (37% / 61%)

Transformers: Dark of the Moon: 3 July (60% / 70%)

Captain America: July 22 (40% / 68%)

Opening weekend only : Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2: July 15 (68% / 71%)

[Added July 31: The opening weekend for The Smurfs followed a similar pattern. The July 29 release made 45% of its gross from 3D engagements; 60% of its venues showed 3D. As Box Office Mojo points out, on the same weekend in 2009, G-Force made 56% of its opening-weekend gross in 3D, which showed in only 43% of theaters.]

(Granted, there is a problem with such figures. The percentage of locations showing 3D is based on theaters, not screens. Any multiplex showing 3D counts as 1, even though it may have 3 screens showing 3D and 2 showing 2D. Whether those two 2D screens would be credited to the venues showing 3D or 2D is not stated. Unfortunately, the way box-office figures are reported, there is no way to calculate by numbers of screens. We’ll do what we can with what we’ve got. In addition, venues without 3D tend to be one- or two-screen theaters in small towns. That 2D now brings in more than half the gross income for most 3D films is all the more impressive.)

Now for the list of films. There are interesting patterns here. First, the drop in 3D percentages came at about the time when the summer-movie season began, and with one exception is has proven surprisingly consistent, hovering in the 40-45% range. Second, the greater the gap between the percentage of income and the percentage of theaters, the less well 3D would presumably be performing for each release. Thus although Transformers: Dark of the Moon brought in a higher percentage of 3D income, it performed proportionately no better than, say, Rio. Third, as long as the percentage of income is less than the percentage of theaters, it should be the case that the average per theater for 2D showings should be higher than those for 3D—which is true for every film.

More theaters, fewer tickets

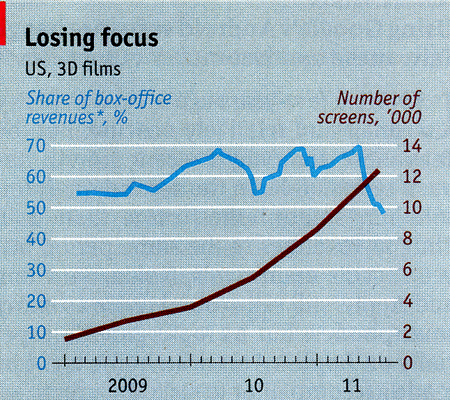

The decline in 3D’s contribution to film grosses has come despite the fact that the number of screens in the U.S. equipped to show 3D has gone up roughly six-fold since the beginning of 2009: from under 2,000 to over 12,000. Take a look at this graph from The Economist (derived from information supplied by BTIG Research and Screen Digest). The point where the lines cross is May, 2011:

Kvetching about 3D as a process and as a method of purse-gouging has declined somewhat, or at least that’s my impression. It’s not gone, though. Take a look at Mark Harris’ smart piece, “Honk If You’re Sick of 3-D!” in the June 24 Entertainment Weekly. Justin Chang’s Variety review of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2, while generally very favorable, concludes: “D[irector of].p.[hotography] Eduardo Serra’s brooding, beautiful work gains little, however, from the underwhelming stereoscopic conversion; this is the first Potter film to be released entirely in 3D as well as 2D, and on this count, at least, one can be grateful that it will be the last.” “The “entirely in 3D” phrase refers to earlier episodes which have had a few scenes in 3D.)

Kvetching about 3D as a process and as a method of purse-gouging has declined somewhat, or at least that’s my impression. It’s not gone, though. Take a look at Mark Harris’ smart piece, “Honk If You’re Sick of 3-D!” in the June 24 Entertainment Weekly. Justin Chang’s Variety review of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2, while generally very favorable, concludes: “D[irector of].p.[hotography] Eduardo Serra’s brooding, beautiful work gains little, however, from the underwhelming stereoscopic conversion; this is the first Potter film to be released entirely in 3D as well as 2D, and on this count, at least, one can be grateful that it will be the last.” “The “entirely in 3D” phrase refers to earlier episodes which have had a few scenes in 3D.)

There was also the controversy back in late May over whether 3D lenses, which notoriously cast dim images of 3D films, were being left on movie projectors for 2D screenings, thereby dimming the light getting to the screen for them as well. I don’t have the space to trace that discussion, but you can read about it in the original Boston Globe article, Roger Ebert’s indignant follow-up, and an expert projectionist’s assessment of the situation. Here the problems were being discussed largely in relation to 2D screenings.

But for quite some time now the larger 3D-equals-dim-images notion got wide coverage, and the topic had featured in many articles and postings critical of 3D. All that must have had some impact. In June Variety announced that for Transformers: Dark of the Moon Paramount would take “the unprecedented step of releasing a special digital print aimed at delivering almost twice the brightness of standard 3D projection.” These special prints, however, only went to about 2,000 theaters, those with RealD systems. But would prospective ticket purchasers know which cinemas had these prints? As Variety pointed out, “Exhibs may want to avoid planting the notion that some 3D screens are better than others when there’s no price distinction between the screens.” Given that it’s almost impossible these days to call a movie theater and ask a question, I doubt whether many moviegoers who attended Transformers knew which version they saw. Paramount’s move was obviously a desirable one, but it can’t account for the relatively high percentage of the film’s 3D income. (The New York Times also covered Michael Bay’s and Paramount’s efforts to promote screen brightness for the film.)

All in all, evidence seems to show that many theater owners are losing business by showing 3D films. Of Captain America’s total gross income, 40% came from the theaters showing 3D, which amounted to 68% of all venues (2511 locations out of 3715). Flip the figures, and the 32% of the theaters showing the film in 2D brought in 60% of the gross. On average, if you were an exhibitor playing the film, you made more money if you showed it in 2D. A lot more. Even not being able to charge $3 extra.

Box Office Mojo’s report on Captain America‘s first weekend confirmed that attendance was not dropping for the film as a whole, but that a greater proportion of people were opting for 2D: “While the gross difference was a sliver, Captain had eight percent greater estimated attendance than Thor, which received more bolstering from 3D (and had IMAX): Captain‘s 3D share was 40 percent at 2,511 3D locations, compared to Thor‘s 60 percent at 2,737.

Industry spokespeople are putting a good face on all this. Rob Moore, vice-chairman of Paramount, seized upon Transformers: Dark of the Moon’s 60% 3D opening-weekend share to boost the format to Variety: “‘There are so many 3D releases, audiences now are going to pick and choose which films to see in 3D,’ Moore said, before adding that the format has become a tool more for event filmmaking. ‘If the 3D is good, audiences are going to pay for it.'” But of course, most theater-goers don’t know whether the 3D is good until they have already paid for it. They go for other reasons, whether star, director, or genre. Or maybe it’s what their date or friends or family want to see. If it has those factors and it’s in 3D, it might seem worth the extra $3.

The opening weekend for Deathly Hallows might tend to confirm Moore’s claim, but the 3D share of the gross was still slightly below the percentage of 3D theaters, if not by much, and included an unusually large number of Imax locations (274)–which charge an even larger fee for 3D. Given the fans’ frenzy to see Deathly Hallows on its first weekend, they probably bought tickets for whichever screening they could, not much swayed by whether they would be seeing it in 3D or 2D.

Another point before I move on. Consider The Hangover Part II: $80 million dollars announced budget, $562.9 million worldwide gross and still in distribution. No 3D.

Anti-3D sentiment

Some people just don’t like 3D, supplement or no supplement. I went to some of the early releases to keep up with developments in the industry. It’s part of my job, after all. But after I got a sense of what it was like, I gave it up. I think the last 3D film I saw, apart from Werner Herzog’s wonderful Cave of Forgotten Dreams in February, was Avatar in December, 2009, and the one before that Up, in the summer of that year. I just saw Cars 2 the other day, 2D and on 35mm film, a treat that we must savor before release prints on film disappear over the next few years. By the way, Cave of Forgotten Dreams is the only exception to my new avoid-3D rule, and it also happens, proportionate to its budget, to be the most successful 3D film so far this year.

I’ve seen the two Pixar films made since Up only in 2D, and I don’t miss the 3D at all—despite the fact that Pixar’s films are probably the best that have been made during the latest vogue for 3D. Cars 2 naturally had quite a few shots with depth in the set design and staging. It occurred to me when I saw them that I actually might be getting a stronger sense of depth watching them in 2D than in 3D. The human mind has all sorts of ways of reading depth cues in a flat image. 3D tends to exploit only one of them, binocularity, which I suspect minimizes the others. I have no scientific evidence for that, just my own impression formed while watching the film.

I’m far from alone in avoiding 3D. The other day I participated in an online exchange on the subject. Sean Axmaker, contributor to the Parallax View website, wrote on his Facebook page that he had just seen Deathly Hallows 2 on film, in 2D and added, “I’d see “Captain America” here too, but it’s only in 3D and I just don’t see the need to see it with an extra pair of glasses on.”

The issue of studios and theaters switching entirely from 35mm release prints to digital projection would require a whole additional entry. But in late May Variety ran a long story, “Studios must revisit d-cinema,” with people from within the industry recounting dismal experience viewing both 3D and 2D films with digital projection. One 3D system cuts fully half the light from the projector. Cinematographer Roger Bailey is quoted: “It’s unbelievable that in an age when we think we have unbelievable technology, and the studios are talking about eliminating 35mm film prints in the next 18 months, that they haven’t begun to sort out the problems that have been caused by digital projection.”

The Economist ended its recent article, the one that contained the above graph, on a sour note:

Richard Gelfond, the boss of IMAX, reckons customers have become picky. “People used to see something just because it was in 3D,” he says. Now they ask how much pleasure the glasses will add. The explosive “Transformers 3” did well in 3D; perhaps the 2D version was not sufficiently headache-inducing. The key to three-dimensional projects, then, is to put out hugely popular films with extraordinary special effects. Easy.

Speaking of headaches, a small study conducted at the University of California-Berkeley seems to indicate that 3D glasses can cause eyestrain and discomfort. For those who want the full scientific text, it’s here. For a brief summary, go here. The main point is that the eyes naturally try to focus on the screen (the focal distance). The vergence point is where the imaginary lines going out from the 2 slightly separated 3D lenses come together. If it’s in front of or “behind” the screen, eyestrain can occur, since one is trying to focus on two different planes in depth simultaneously. The problem turns out to be worse the further you sit from the screen.

I myself have not noticed eyestrain or headaches caused by watching 3D movies with the current generation of glasses. I could imagine that since eyestrain is cumulative, those who watch large doses of television or spend hours at a 3D gaming console would have greater problems with the glasses.

Whether we want it or not

Business types seem to think people want 3D inserted into their lives. Note the 3D Webcam, pictured at the bottom. The accompanying text says, “The Minoru 3D Dual lens web camera is still at proof of concept stage atm but it can create stereoscopic 3D video which needs those cool blue and red 3D glasses to view.” (Note: “atm” means “at the moment,” not “go withdraw some money to buy one.”) I also ran across the 3D drawing pad pictured below left. It is available from the Perpetual Kid website, which explains: “Each page is a stereographic background for your writing or drawing. Put on these ultra cool (come on…you know you look good in them!) 3D specs and see your lines float above the page!” Why do people promoting such things seem to think that we can be convinced these glasses are cool?

Right now there’s a big push to sell 3D mobile phones and other handheld gadgets. On July 25, Roger Cheng posted a skeptical article on the subject of the Thrill 4G model, by LG:

Right now there’s a big push to sell 3D mobile phones and other handheld gadgets. On July 25, Roger Cheng posted a skeptical article on the subject of the Thrill 4G model, by LG:

But it’s unclear if consumers are ready to grab hold of it yet.

3D is the latest feature to be crammed in the increasingly Swiss Army-knife-like smartphone. Like with televisions, the feature is getting aggressive marketing support. But despite the marketing campaigns, the feature has been little more than a gimmick. And like 3D televisions, there’s been tepid interest.

“3D is just one of an onslaught of features that end up on a phone even if people don’t ask for it,” said Maribel Lopez, an analyst at Lopez Research.

Sam Biddell over on Gizmodo, did not hold back in commenting on the HTC Evo 3D phone:

The EVO 3D is the first phone to ever literally hurt my face. The 4.3-inch 3D screen’s glasses-free, of course, which means it uses the same auto-stereoscopic method as the Nintendo 3DS. Well, not the same—the 3DS is a joy to use and view, while looking at 3D stuff on the Evo felt like I was having my eyes gouged out, Oedipus-style. It gave me a headache. I wanted to look away. And for what? A 3D effect that just isn’t very good. To pull off a 3D picture of video that has any ‘pop’ whatsoever, you need to use framing so contrived as to render the whole thing pointless.

This, mind you, despite the fact that you don’t need glasses to see a 3D image on phones.

What’s next for theatrical 3d?

In my original “Has 3D already failed?” I wrote that it

depends on how one defines success. If you’re Jeffrey Katzenberg and want every theater in the world now showing 35mm films to convert to digital 3-D, then the answer is probably yes. That goal is unlikely to be met within the next few decades, by which time the equipment now being installed will almost certainly have been replaced by something else […] But it also seems possible that the powers that be will decide that 3-D has reached a saturation point, or nearly so. 3-D films are now a regular but very minority product in Hollywood. They justify their existence by bringing in more at the box-office than do 2-D versions of the same films. Maybe the films that wouldn’t really benefit from 3-D, like Julie & Julia, will continue to be made in 2-D. 3-D is an add-on to a digital projector, so theaters can remove it to show 2-D films. Or a multiplex might reserve two or three of its theaters for 3-D and use the rest for traditional screenings.

If for the rest of this year blockbuster films continue to bring in 40% of their gross revenues in 3D-equipped venues and those venues continue to be around 70% of the total locales, then I would think that the saturation point I mentioned has been exceeded. Some theater owners might decide that they could make more money with less hassle by showing 2D. That would drive 3D devotees to the reduced number of 3D houses, making their revenue go up. Which in turn would presumably make some of the exhibitors who had given up 3D go back to it, and the balancing act would continue until the precise saturation point is finally attained. But at this point, adding more 3D screens to a multiplex or converting a mom-and-pop theater in a small town would probably just worsen the problem. I think what I predicted is coming true, that multiplexes will reserve a small number of their screens for 3D and keep the rest flat. Maybe the studios will decide that $30 million is not a great investment.

The more important news is that digital projection will continue to spread. Some theaters have installed it already to save costs. Wanting to play 3D films (which mostly can only be shown digitally) has undoubtedly been a factor in exhibitors’ purchases of digital projectors, but it will probably become less so now. The studios, however, want to give up 35mm release prints, which cost a lot for both lab work and shipping. They’ll pressure the theaters until it finally happens.

Stifel Nicolaus analyst Ben Mogil downgraded box-office projections for the second half of the year and lowered his target for the company’s stock price to $27, from $32. His report came a week after similar predictions were made by Merriman Capital. The stock was trading at $25.33 late Monday.

“We believe that estimates for IMAX for [second half 2011] are too optimistic given that the [fourth quarter 2011] slate has three kids’ films, a genre which this year has seen considerably lower 3D share this year compared to last,” Mogil wrote.

Most, but not all, Imax movies play in 3-D, a technology that has been dropping in popularity among domestic movie audiences.

These downgrades came partly as a result of the fact that IMAX has had three straight quarters where income fell short of its own predictions.

This story was updated later the same day: “Imax Chief Executive Richard Gelfond said, ‘We have a diversified slate based on blockbuster films in 2D and 3D, for families and fanboys. We think it’s way too premature to predict how the slate will perform for the year.'”

As I read this, Gelfond is assuring investors that there are quite a few 2D films mixed in among the 3D films, so that the latter’s decline will not hurt the firm’s overall income.

On July 26, Variety ran a long story with Jeffrey Katzenberg giving an elaborate explanation of how Kung Fu Panda 2 underperformed in the U.S. because it opened the same weekend as The Hangover: Part 2. There’s no indication as to how a raunchy, R-rated film could run roughshod over a kid-oriented animated movie. All those older brothers refusing to take their younger siblings to the movies? Usually it’s called “counter-programming” and often it works.

According to Variety:

Katzenberg is also still high on 3D, at least overseas, where “the marketplace couldn’t be stronger,” he said. “Outside of North America, the performance of 3D continues to be very strong across many different films. We see continued interest in it and appeal for it and growth over these next 12 to 24 months. There’s still a pretty decent way for it to expand meaningfully internationally.”

Domestically, the exec admitted to being partly to blame for some of the extremely optimistic views of 3D’s revenue potential. At the same time, the pessimism of its longevity is also on an extreme level, he said.

For DWA [Dreamworks Animation], at least, 3D remains one of the best returns on investment for the company, after it was able to shave off the costs to produce its pics in the format.

Two years ago, DWA spent $15 million per pic to deliver a 3D version. Today, the cost is half that, Katzenberg said. The studio now has nine 3D films in production.

If executives keep offering rationalizations and suggestions that we look to the future instead of the past, maybe we can conclude that 3D is officially in a slump.

As seen on Gadgettastic.com

Venues and visions

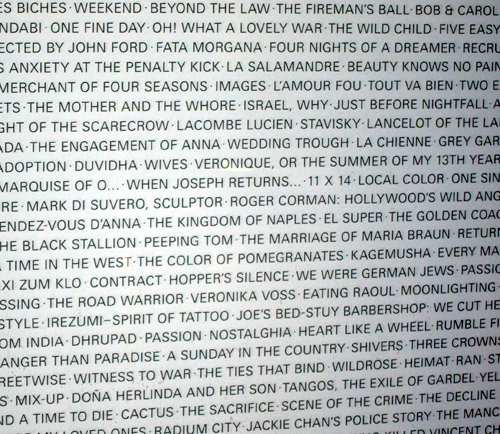

Vitrine outside future quarters of the Film Society of Lincoln Center (detail).

DB here:

During our month in NYC, we didn’t visit only art museums (although KT was at the Met a great deal). We also, no surprise, hit some of the city’s premiere movie spots. The places were often as impressive as the films, and all deserve the support of cinephiles both local and visiting. Herewith, a recap of our visits.

Fun things happen on your way through the Forum

Mike Maggiore, in the lobby of Film Forum.

Film Forum, running since 1970, has established itself as an outstanding venue for new releases and classics. It has done heroic work over the years. I stopped by to see my old Wisconsin friend Mike Maggiore, one of FF’s programmers, and met his colleagues, including Karen Cooper, a legend in US film culture. They had just recently had a remarkable triple-night string of visitors: Scorsese introducing his new documentary Public Speaking, Jerry Schatzberg with Scarecrow, and Paul Schrader with a fresh print of Diary of a Country Priest. The current FF program, running on three screens, is here and it’s very rich.

Uncle Boonmee will have hit FF by the time you read this. Chris Ware’s gorgeous poster decorates the Forum lobby.

The gem of Astoria

Under MoMI projection, Rachael Rakes (Assistant Film Curator), David Schwartz (Chief Curator), KT, Ethan de Seife (Professor, Hofstra).

The refurbished Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria is a thing of great beauty. Family-friendly, with lots of hands-on kid activities, it also offers a bounty to the cinephile.

For one thing, it has a superb screening theatre. We sampled it when MoMI screened a pretty print of King Hu’s The Valiant Ones (1975). Kristin and I were happy to see our old favorite again.

The same hall gave us a restoration of Manoel de Oliveira’s Doomed Love (1978). The movie, 4 ½ hours long, was shot in 16mm for television. It frankly acknowledges its novelistic source by including stretches of letters and florid declamation (“I will be dead to all men, except you, Father!”), as well as a plot turning on forbidden love and oppressive social relations. This is a world of parlors, convents, trusty servants, candlelit rooms, barred windows, and lovers who actually waste away. The title could apply to virtually every character, down to the maidservant who adores our protagonist and vows, “When I see I am not needed, I will end my life.” The affair draws others into its downward spiral, leaving the hero plenty of time to reflect on his misery and the pain he has inflicted on others.

The plot is quite engrossing in the manner of a triple-decker novel. That makes it all the more surprising that we get no Viscontian spectacle or even the plush upholstery of a Masterpiece Theatre episode. The presentation is rather dry and detached. I wondered if Ruiz’s recent Mysteries of Lisbon, drawn from another novel by Camilo Castelo Branco, was in effect a reply to Oliveira’s film. By comparison with Ruiz’s sparkling compositions and glissando flashbacks, Doomed Love looks reticent and austere.

The austerity is heightened by a self-conscious stylization. The music is aggressively modern, and the lengthy takes (the average shot runs about a minute) are often shot with the low, straight-on camera reminiscent of early cinema.The film begins with a partial view of a door opening, inviting us into the story world, but obliquely. The film closes with a hand lifting a bundle of love letters from the sea and a voice-over (Oliveira’s) explaining how the novel came to be written. The images provide as overt a marking of a narrative’s beginning and its end as you could ask for, and one completely in keeping with the film’s balance between respect for artifice and its concern to let compromised passions leak through.

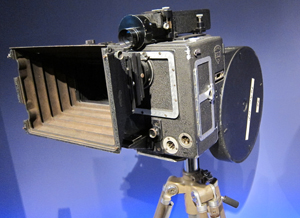

MoMI also hosts a splendid exhibition of media technology. One floor is a wonderland of cameras, sound rigs, printers, and projectors of all sorts, from film to TV and beyond. One favorite among many: A Mitchell VistaVision camera from 1954. It’s a funny-looking thing, but it took very crisp pictures. The horizontal film transport allowed larger and sharper images than the vertically-run formats that were normal for 35mm.

There are also displays devoted to screenplays, make-up, hairdressing, and special effects. I was especially taken with the finely detailed miniature for the Tyrell corporation building in Blade Runner.

In all, MoMI deserves all the praise it has gotten after its reopening. Rochelle Slovin, the founding director of the museum, started in 1981 and is retiring this week. She can be proud of what she and her colleagues have accomplished.

Jaywalking down Broadway

Wundkanal (Thomas Harlan, 1984).

Then there’s Lincoln Center, another long-time shrine of cinephilia. Like MoMI, the Film Society is in the process of building. The new complex will house theatres, a café, and a flexible lobby space. It’s scheduled to open in late spring.

The Film Society’s František Vlácil retrospective early in our stay brought this little-known filmmaker to my attention. I had seen only his best-known item, Marketa Lazarova (1967), and that quite a while back. So I was happy to catch his charming early short, Glass Skies (1958), and three features.

Vlácil mastered both filmic poetry and prose. The White Dove (1960) is a simple, lyrical story of two young people who never meet: a girl living in a beachside town and a wheelchair-bound boy in the city. Alternating sequences show them brought together by the homing pigeon that the girl sends out. The boy in a moment of thoughtless cruelty shoots the pigeon with his air rifle. Soon, with the help of an artist living in the same apartment house, he nurses the bird back to health. The film is richly shot in crisp, wide-angle black-and-white, and Vlácil exploits eyeballish imagery to create links between the girl’s seaside milieu and the artist’s Chagall-like paintings.

Like most filmmakers moving from the 1960s to the 1970s and from black and white to color, Vlácil recalibrated his visual design. Smoke in the Potato Fields (1976) gets your attention from the start with its disconcerting cutting during an airport departure. Laconic and elliptical, shot with long lenses and long takes, it tells an understated story of a middle-aged doctor moving to a small-town clinic. We get a cross-section of the townsfolk, from ambulance driver and gravedigger to censorious nurse and an unhappy married couple. The central drama concerns the doctor’s care for a tomboyish girl who gets pregnant and considers an abortion.

Shadows of a Hot Summer (1977), set in 1947 and shortly before the Communist takeover of the Ukraine, is more conventionally gripping. A farm family is held prisoner by rapacious resistance fighters. The taciturn father has no allies among the locals, who seem to resent his prosperity, and he dares not call attention to his plight. As in a Boetticher film, the hero plays his hand judiciously, mostly passive but carefully picking the battles he can win. The final sequence, precipitated when the marauders find him hoarding shotgun shells, is a taut, suspenseful exercise in action cinema. Shadows of a Hot Summer has daring stretches of silence and an unsettling score, along with discreet zoom shots typical of the period worldwide. These installments in the Vlácil retrospective show that we nonspecialists still probably underestimate the range of artistry that could be achieved in the apparently inhospitable atmosphere of Communist Eastern Europe.

Film Comment Selects brought us a host of strong items, of which I caught four. I had missed Jia Zhangke’s I Wish I Knew (2010) at Vancouver, so I was happy to catch up with it. It seems to me a moving but minor effort in his career, lacking the bolder organization of the comparable Useless (2007; the latter in our blog here) and 24 City (2008). I didn’t think that the figure of the wandering woman Zhao Tao, punctuating people’s recollections of life in Shanghai, developed very much. Still, I was struck by how much Jia’s interviewees were able to say about the effects of the Cultural Revolution on their lives, and there is an unforgettable account by a woman of her father’s execution at the hands of the KMT.

Film Comment Selects brought us a host of strong items, of which I caught four. I had missed Jia Zhangke’s I Wish I Knew (2010) at Vancouver, so I was happy to catch up with it. It seems to me a moving but minor effort in his career, lacking the bolder organization of the comparable Useless (2007; the latter in our blog here) and 24 City (2008). I didn’t think that the figure of the wandering woman Zhao Tao, punctuating people’s recollections of life in Shanghai, developed very much. Still, I was struck by how much Jia’s interviewees were able to say about the effects of the Cultural Revolution on their lives, and there is an unforgettable account by a woman of her father’s execution at the hands of the KMT.

I’m a big fan (at a distance) of the Chauvet caves and their Ice Age imagery, so Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), a 3D tour of the site, was right up my alley. The film turned out to be a strong argument for 3D (as Kristin anticipated), since it lacked that sense of cardboard-cutout planes you usually get and really brought out volumes. The tigers, bison, and other wondrous creatures seemed to bulge and ripple across the walls.

The biggest revelation the Film Comment program held for me was the double bill of Thomas Harlan’s Wundkanal (Gunwound, 1984) and Robert Kramer’s Notre Nazii (Our Nazi, 1984). Wundkanal was made by Thomas Harlan as part of his crusade to expose the bad faith of postwar Germany, where many former Nazis held positions of power. Harlan’s father was the Nazi filmmaker Veit Harlan, and as Kent Jones pointed out in his illuminating introduction, the son seems to have taken upon himself the burden of guilt that his father should have felt.

Wundkanal proposes that a terrorist gang has kidnapped the respectable citizen Dr. Seibert, interrogated him about his murderous past, recorded the sessions on videotape, and eventually staged some of their own suicides as part of the exercise. Dr. S. is played by Alfred Filbert–himself a Nazi let out of prison for medical reasons. The whole production, then, becomes both a vision of Germany’s blindness to history and a trap for a man whom Thomas Harlan suggests has gotten off far too easily. “A new idea: to use the real criminal, to deceive him and convince him it was a film about him.”

Filmed by the great Henri Alekan, it is a phantasmagoria. We are in a sunless bunker jammed with old photos, thermos jugs, automatic pistols, video clips from a Harlan film, and other detritus: a sort of chamber-play version of a Syberberg no-man’s land. Questioned by offscreen interrogators, Dr. S. admits to his crimes plaintively. The hallucinatory quality of the exercise is enhanced by sound cuts that split a sentence into bits (sometimes clear and close, sometimes filtered through speakers) and a drifting camera that may start on Dr. S. but then wanders across the litter to end on a video image of Dr. S. testifying in another session, at which point the sound of that session may take over. In one passage, the camera tours the room and picks up several bits of Dr. S.’s testimony, in the real space and in several video monitors crowding the area.

Kramer’s Our Nazi is in a way a making-of for Wundkanal, but it’s also a powerful film in its own right. Acting as his own cameraman for the first time, Kramer (director of the classic militant films The Edge, Ice, and Milestones) takes us behind the scenes to show Thomas Harlan’s obsessions and to expose Filbert more directly than Wundkanal does. Harlan talks of the fatal love he had for his father, reflecting that the old man’s charm finally withered in the face of his inhuman complicity with the Reich. Intercut with this soliloquy are shots of Filbert being made up for his video scenes, as he talks of his dueling scars and his youth: “All the ambitious men became Nazis.”

Our Nazi gives us two disturbing confrontations, one with Kramer sitting Filbert down and charging him with crimes against humanity, the other more prolonged and painful. Harlan and the crew encircle their star and hurl accusations at him. This scene, glimpsed and abstracted in Wundkanal, pulls the viewer in different directions as the feeble old man tries to escape Harlan’s relentless recitation of Filbert’s war crimes. In the discussion with Kent Jones after the screenings, Paul McIsaac rightly called the Kramer film a demonstration of the concreteness that direct cinema can yield. Shot in Hi-8, Our Nazi counterbalances the abstract, somewhat detached artifice on display in Wundkanal. Kramer dwells on unexpected details, such as Alekan hesitating to autograph a souvenir production photo for old Filbert. The two movies need to be seen together because they engage in a crosstalk that yields provocatively different information, emotions, and cinematic resources.

Our month in New York went by all too fast. We seldom visit the city these days; I’m in Hong Kong more often than Manhattan. Our trip brought back memories of my undergrad visits from Albany in the 1960s (packing four films into a day-trip) and, during the 1970s, doing dissertation research and visiting friends and teaching for a semester at NYU. It also allowed me to get back in touch with some of my oldest friends, like Rich Acceta-Evans from junior-high days. And the trip reminded me of what a cosmopolitan film culture is like, with institutions like these and still others (Anthology Film Archives, MoMA, etc.) braving tough times to bring the right movies to lucky audiences.

Apart from those named above, I want to thank the friends we met with during our stay. Scott Foundas was particularly helpful on this entry. I gave talks at various venues, so I’m grateful to Malcolm Turvey of Sarah Lawrence College, to the NYU Film Studies faculty, and to Patrick Hogan at the University of Connecticut–Storrs. Special thanks to Ken Smith and Joanna Lee for arranging a visit to the Museum of Chinese in America for a discussion of Planet Hong Kong.

Speaking of Planet Hong Kong, I discuss The Valiant Ones in Chapter 8 there, as well as in the essay “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” in Poetics of Cinema. For a sensitive examination of Doomed Love, go to Tativille.

Some films in the Film Society’s Vlácil retrospective are available on DVD from Facets Multimedia. Wundkanal and Our Nazi have been issued on a single DVD edition with English subtitles, and it can be found on the Edition Filmmuseum site. Every film studies and filmmaking department should order it, I believe. See also “Truth or Consequences,” Kent Jones’ essay in Film Comment 46, 2 (May/ June 2010), 48-53, from which I’ve taken the Harlan quotation. Jones discusses other films, including Christoph Hübner’s 2007 study of Thomas Harlan, Wandersplitter, which is also available on a Filmmuseum disc. Thomas Harlan is one of the main interviewees in the documentary Kristin recently wrote about, Harlan: Im Schatten von Jud Süss.

For more coverage of the “Film Comment Selects” series, see R. Emmett Sweeney’s review on the Movie Morlocks site, with particularly discerning remarks on I Wish I Knew. Jesse Cataldo provides sharp commentary on Wundkanal at The House Next Door.

Alfred Filbert, confronted with the tattooed arm of an Auschwitz survivor (Our Nazi).

Has 3D already failed? The sequel, part 2: RealDsgusted

Kristin here–

For part 1, see here.

Darn those quickie conversions!

In past years, 3D proselytizer Jeffrey Katzenberg, head of Dreamworks Animation, has complained about the slow progress of the conversation of theaters to digital and 3D projection. By September, 2010, faced with a growing backlash against the technology, he was more concerned about the conversion of films shot in 2D to 3D. The 3D Hollywood in Hi Def site reported:

Jeffrey Katzenberg opened the 3D Entertainment Summit with his usual provocative verbal flare [sic], defending 3D successes against the recent growing tide of critics claiming it is already dying — “It seems there are some in Hollywood who are determined to seize defeat from the jaws of victory. Six of the top 10 movies this year are 3D; I guess we have to have 10 of 10.” — and lambasting filmmakers and studios who convert movies to 3D after they are produced in 2D, calling them “downright ugly” and claiming they are endangering the technology that is single-handedly responsible for the industry’s growth in the past year.

On the whole the media were hardly sympathetic, perhaps because Katzenberg has been largely responsible for making 3D–including those 3D-ized films–so profitable. Patrick Goldstein of the Los Angeles Times called his speech a “desperation plea” and gleefully linked to several anti-3D articles, including some of the ones I’ve linked to in this and last week’s entries.

What Katzenberg didn’t point out was that some of the six films in the top ten were the same retrofitted ones that he was attacking: Clash of the Titans and The Last Airbender. Alice in Wonderland was shot in 2D, but planned with the knowledge that it would be converted to 3D. (Gulliver’s Travels had not yet demonstrated that retrofitted 3D doesn’t always make for big domestic BO.)

Yet about a month later, in an interview with the New York Times, the other most influential figure in the push toward 3D, James Cameron, was discussing converting a film released in 1997 and not planned with 3D in mind: Titanic. (He plans to release it for the 100th anniversary of the ship’s 1912 sinking.) For Cameron, conversion is a problem when it is done hastily and carelessly. Of the retrofitting of Clash of the Titans he remarked, “It was just being applied like a layer, purely for profit motive.”

One problem with converting a 2D film to 3D comes from the fact that the process is far from an exact science (or art). Cameron commented on his search for a company to handle Titanic:

These conversions are so painstaking to complete correctly, Mr. Cameron said, because “there’s no magic-wand software solution for this.”

He added: “It really boils down to a human, in the loop, sitting and watching a screen, saying, ‘O.K., this guy is closer than that guy, this table is in front of that chair.’ ”

For his 3-D “Titanic” rerelease, Mr. Cameron said he had approached seven companies about working on the film, testing each by asking it to convert about a minute of movie footage before he chose the best two or three efforts.

“All seven of the vendors came back with a different idea of where they thought things were, spatially,” he said. “So it’s very subjective.”

He also points out that studios will inevitably search their vaults for films to convert.

How does 3D conversion work? An invaluable issue of Screen International, “European 3D Special 2010,” explains in terms reasonably comprehensible to the lay person:

While each company goes about it slightly differently, the requirements are broadly the same: the creation of a second identical version (to obtain a second eye view) and the isolation of foreground from background elements by rotoscoping, adding depth and then painting or animating in the gaps. “When you move an image in this way to create two views, the biggest problem is filling in and cleaning up the area left behind,” says Vision3 post-production supervisor Angus Cameron. (From “Conversion: 2D to 3D,” p. 9)

(This issue, by the way, shows that studios doing conversion are popping up in Europe as well as in the U.S.)

As Cameron’s statements and this description suggest, the process is a painstaking, lengthy one. Many in the industry praised Warner Bros.’ decision not to release Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part l in a 3D conversion. The studio cited insufficient time before the release date as its reason. Cameron remarked, “You can’t do conversion as part of a postproduction process on a big movie, because no one is willing to insert the two or three or four months necessary to do it well.” (Of course, some foes of 3D may have suspected that the real reason for Deathly Hallows I being released only in 2D may have been that WB saw the declining share of the box office going to 3D and decided it just wasn’t worth it.)

Graham Clark, the head of stereography for the Stereo D company, claims that the conversion process can be done well as long as enough time is allotted for it:

“The main thing is this is an artistic process,” he said of conversion. “Composing things in 3D space is every bit as artistic as composing things in 2D space.” […]

“Because there are so many factors that go into deciding how to compose a shot, you need interaction with the producer, director, cinematographer—so you are not, at the eleventh hour changing things,” he said. “Also, visual effects studios are used to handing off [VFX elements] at the eleventh hour. Conversion is new in the film pipeline, and people aren’t used to having to hand stuff off earlier.”

Clark points out some of the ways that conversion could be used to enhance a film. If a 3D camera can’t be fitted into a certain space, a shot can be done in 2D and converted. If after a scene is shot the filmmakers want to shift the spatial relations of elements within it, they can do so—eventually, at any rate, since the techniques for doing that are still being developed. As Clark points out, films shot in 3D usually have some shots that are converted. Even Avatar included some. (See Carolyn Giardina’s “The art of the 3D conversion,” The Hollywood Reporter, October 29, 2010, pp. 6, 87. The same article, retitled “Expert: The Biggest Challenge in 3D Conversion,” is available here for subscribers.)

Given that most effects-heavy films these days face a major crunch to make their release dates and have to employ multiple effects houses to do the job, a quality 3D conversion can only add to the headache. Not to mention more work for the conscientious director and cinematographer who have to sit in on the decision-making to prevent the quality of their work from being diminished.

All in all, it looks as though 3D will not die out completely. But will there come a time when every screen in the world’s major markets will have the capacity to show 3D films? That was Katzenberg and Cameron’s original ideal, or so they said. Others had the same vision. Katzenberg has committed Dreamworks Animation to making only 3D films. Does he plan eventually to eliminate 2D prints altogether? Cameron claimed he would do that with Avatar, but he had to give in on that one.

Maybe Katzenberg and Cameron would object that they didn’t mean that literally every screen would be 3D. Yet advocates for 3D often compare it to sound or color or widescreen, all processes which did fully penetrate theatrical exhibition. In major markets sound took about three years (though places like Japan and Russia still made a few silent films into the mid-1930s). Widescreen took about six years. The most apt comparison is perhaps color, which didn’t become really viable until the mid-1930s; it remained somewhat rare into the 1940s and didn’t really become dominant until the late 1960s. But in our era of fast-moving technology, perhaps three decades from now 3D, at least in its current form, requiring glasses, will be a dead technology.

In my first entry on 3D, I mentioned that not very many producers or directors have been proselytizing for the process nearly as much as Katzenberg and Cameron have. Lucas is converting the Star Wars series, but he doesn’t promote the process with the fervor he once devoted to digital cinematography and projection and Dolby sound. Spielberg’s first 3D film, The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn, is coming out in December, but he’s not making the round of the trade fairs singing the praises of the process. The same is true of Scorsese and his 3D debut, Hugo Cabret, also coming in December.

Peter Jackson and Guillermo del Toro had originally stated that The Hobbit would be 2D, so as to keep a unified look alongside the Lord of the Rings trilogy. But when Warner Bros. finally greenlit the film in October of last year, the press release included the news that the two parts will be shot in 3D. Peter Jackson is a big booster of the Red brand digital cameras (used on The Lovely Bones and District 9), and he enthused briefly in the Red press release about using the new Epic 3D model for The Hobbit. His Weta Digital facility did most of the effects for Avatar. Still, he’s not out on the stump, urging theaters to convert and warning filmmakers not to retrofit their films, and many fans wonder whether Warner Bros. left him any choice in the matter of using 3D. (Vague statements have been made about the trilogy being released in 3D eventually, but there’s no firm news about that.)

Of course, assuming 3D is here to stay, there will always be bad conversions because there are bad instances of anything. There are shoddy-looking 2D movies and always have been. Still, the studios didn’t charge extra for them. There are and will be movies originally shot in 3D that are bad. People will have to pay extra for them, too, at least in the near future. Somehow, paying that premium 3D price seems to make people more indignant about bad movies than paying the regular price does. Studios are not likely to heed Katzenberg’s plea that they not crank out cheap 3D-izations. If such sloppy jobs as Clash of the Titans continue to come out and sour people on paying premiums, the studios may have to lower those premiums until they just cover the extra costs of production and of the glasses. If 3D ceases to generate any significant extra profit, will the studios bother with it?

Or will they take the more sensible approach that I mentioned at the beginning of the first part of this entry, settling for multiplexes converting two or three screens for 3D capacity and showing either special-event films like Avatar or cheap genre films like Piranha 3D? Part of that approach would include continuing to make 2D prints of films. There are quite a few viewers who would prefer that option.

At least one studio chief agrees. Last summer Home Media Magazine‘s article on Toy Story 3 reported: “Disney CEO Bob Iger, in a recent financial call, cautioned flooding the market in 3D releases, opting instead that earmarked titles in the format should be done strategically, and not as an afterthought.”

Before moving on to vociferous 3D opponents, I’ll mention a couple of intriguing, possibly significant things that I’ve noticed that may indicate a short life (or possibly a marginalized long life) for 3D.

First, on January 10, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced its scientific and technical awards. (Those are the ones that are given out at a separate ceremony and are given a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it acknowledgment during the Oscar ceremony.) These awards are often given for developments that occurred years earlier. On the other hand, major innovations tend to get honored fairly soon. The two technical awards given for special-effects programs for The Lord of the Rings were given in 2004, the same year that The Return of the King swept the Oscars.

This year’s awards include none relating to 3D. (For Variety subscribers, the complete list is here; so far they don’t seem to be listed on the Academy’s website.) Instead, they relate to such inventions as a new winch for flying heavy props like cars, a new suspended-camera mount, systems for queuing special effects for rendering, a method for facial-expression capture, and an innovative way of using bounce lighting in computer animation. Maybe it’s not significant, but it may give a clue as to the professional motion-picture technicians’ view of 3D.

Second, this past summer David and I were able to attend a trade demonstration at a local theater. The Technicolor firm had innovated a 3D add-on lens for 35mm projectors. Technicolor had seven Hollywood studios signed on, agreeing to provide analog 3D prints formatted in the system. (13 of the 19 films released in 3D in 2010, beginning with How to Train Your Dragon, were available on 35mm 3D prints.) The main appeal of the system was that distributors don’t buy it; they rent it by the year. The special silver screen needed for the technology would cost around $4000 to $6000 to install (and could be used for some digital 3D systems, including RealD), and the lens would be rented at $2000 per 3D film exhibited, with a maximum of $12,000 per year. In contrast, a digital 3D conversion costs at least $75,000 per house.

Some small-town exhibitors from the surrounding area were obviously intrigued. They couldn’t afford to convert to digital/3D, but this offered a cheaper option. Nobody mentioned it during the demo, but the other obvious implication seemed to be, if you just rent your equipment, you won’t lose out if the 3D craze fizzles out. The firm anticipated having over 500 systems installed in the U.S. by the end of 2010. (For a case of a theater in Decatur, Illinois that canceled its deal with Technicolor, see here; the management failed to understand that one has to charge higher admission for 3D tickets because the print rental fees and 3D system cost more, and the projectionist keeps referring to the 3D lens as a “camera.” On the whole, one can’t feel that in this case the Technicolor system itself was to blame. The 25 equipped screens out of the 150 in the Bow Tie Cinemas chain in California presumably have fared better.)

[Added later the same day: Skip Huston, who run Huston’s Avon Theater 3 in Decatur, tells me that the reporter was the one who called the lens a “camera.” (Knowing what it is to be misquoted by a reporter, I can well believe it.) The owners tried to avoid raising ticket prices for their customers, but that just doesn’t work with 3D. Mr. Huston’s theater is a mom-and-pop establishment competing with two Carmike multiplexes. Those wishing to avoid 3D have the option of 100% 2D at the Avon.]

Naysayers galore

The more I see of the process, the more I think of it as a way to charge extra for a dim picture.

Roger’s remark sums up the two beefs people have with 3D. Not surprisingly, when 3D was a novelty and only major films had it, people were willing to pay extra. Now that any multiplex will be likely to have one or two screens devoted to 3D movies at any given time, the premium has begun to seem onerous. And yes, the glasses do cut out a noticeable part of the light coming from the screen.

According to a report by PricewaterhouseCoopers (quoted in The Hollywood Reporter), “a $5 premium per ticket is too much to expect audiences to pay for 3D. That survey indicated that 77% of Americans will not pay a premium of more than $4.” In terms of the industry’s attitude, the report adds, “Many people are over-excited by it. The danger is that industry players risk killing a golden goose by overselling and, in some cases,  overpricing the 3D experience—and by providing too much mediocre content that doesn’t do justice to the technology.”

overpricing the 3D experience—and by providing too much mediocre content that doesn’t do justice to the technology.”

Putting aside the high price, there are those who actively dislike the process. Others admit that there are a few films that justify the use of 3D but that most films using the process released so far have been attempts on the parts of the studio to jack up the ticket prices. If these people are entertainment journalists, they use the forum of their reviews or columns to air their complaints. If they are ticket-buying audience members, they search out the 2D screens or stay home. Some of them blog about their complaints, others write letters to the editor, and others carp about 3D around the water cooler.

Roger Ebert probably has the highest profile of the anti-3D naysayers, as least among the general public. In an article in Newsweek (May 10), he laid out his objections:

3-D is a waste of a perfectly good dimension. Hollywood’s current crazy stampede toward it is suicidal. It adds nothing essential to the moviegoing experience. For some, it is an annoying distraction. For others, it creates nausea and headaches. It is driven largely to sell expensive projection equipment and add a $5 to $7.50 surcharge on already expensive movie tickets. Its image is noticeably darker than standard 2-D. It is unsuitable for grown-up films of any seriousness. It limits the freedom of directors to make films as they choose. For moviegoers in the PG-13 and R ranges, it only rarely provides an experience worth paying a premium for.

Roger goes through each of these reasons in more detail. He writes with conviction, and the studios would be wrong to think that he stands alone. I wonder how many other websites have linked to the online version of the essay. I see it quoted and linked a lot, even eight months after it appeared.

Movie City News critic David Poland, also far from being a fan of 3-D, recently posted an entry called “Will 2011 Be A 3D Car Wreck?” He assesses many of the roughly 30 3D films announced for this year. As he points out, similar films will be competing with each other during the key release seasons, as with Scorsese’s Hugo Cabret, the third in the “Chipmunks” franchise, and Spielberg’s Tintin movie, which are coming out within a short period. He concludes:

But the problem remains… 3D is a tool, not an answer. The problem that I expect next December, for instance, will be a parade of high quality films of a similar tone all piled up in on month. Same with the load of animation in November. And whichever films pay the price – and some films will – it won’t be 3D’s fault, but rather, overloading the marketplace. The franchises are franchises and the product that isn’t franchise will need to be sold smartly and heavily… just as in a world without any 3D at all.

This is an interesting variant on the view of 3D as a symptom of the film industry’s problems. Often popular commentaries link 3D mainly to the loss of audiences to TV, video games, and other new media sources of entertainment. But Poland sees the problem as more related to the increasing dependence on franchises and big event films. When other methods of luring patrons into theaters fails (Johnny Depp and Angelina Jolie together for the first time!), 3D remains a lure–except when it doesn’t, as with Gulliver’s Travels.

These days Entertainment Weekly seems to be mounting a campaign against 3D. Lisa Schwarzbaum makes no bones about her increasing disenchantment with the format. About a quarter of the prose in her December 15 review of The Chronicles of Narnia:Voyage of the Dawn Treader (C rating) is devoted to it:

And that includes the option of watching The Voyage of the Dawn Treader in undistinguished, unnecessary 3-D. I’m more and more frustrated these days by movies that sell the 3-D movie experience as a kind of turbo-charged event, yet the greatest extra we see through plastic movie-theater goggles is the ”dimensionality” of a sword or a boot or the imaginary fur on a CGI  mouse. I’m confounded by the fact that, aside from the Pevensie siblings and their nicely obnoxious cousin, absolutely everything and everyone aboard the Dawn Treader looks one-dimensional, no matter how closely I peer through special specs.

mouse. I’m confounded by the fact that, aside from the Pevensie siblings and their nicely obnoxious cousin, absolutely everything and everyone aboard the Dawn Treader looks one-dimensional, no matter how closely I peer through special specs.