Archive for the '3D' Category

Has 3D Already Failed? The sequel, part one: RealDlighted

Kristin here–

On August 28, 2009, I posted an entry called “Has 3-D Already Failed?” As I wrote then, my title was deliberately provocative. It depended on which of two yardsticks you measured success by:

1. If you’re Jeffrey Katzenberg and want every theater in the world now showing 35mm films to convert to digital 3-D, then the answer is probably yes. That goal is unlikely to be met within the next few decades, by which time the equipment now being installed will almost certainly have been replaced by something else.

2. It also seems possible that the powers that be will decide that 3-D has reached a saturation point, or nearly so. 3-D films are now a regular but very minority product in Hollywood. They justify their existence by bringing in more at the box-office than do 2-D versions of the same films. Maybe the films that wouldn’t really benefit from 3-D, like Julie & Julia, will continue to be made in 2-D. 3-D is an add-on to a digital projector, so theaters can remove it to show 2-D films. Or a multiplex might reserve two or three of its theaters for 3-D and use the rest for traditional screenings.

If the second, more modest goal is the one many Hollywood studios are aiming at, then no, 3-D hasn’t failed. But as for 3-D being the one technology that will “save” the movies from competition from games, iTunes, and TV, I remain skeptical.

So, nearly 17 months later, where do we stand? There has been a considerable increase in the number of screens with 3D projection systems, from 4,400 in May 2010 to 8,770 in early December. That’s out of roughly 38,000. This growth presumably came in response to the huge success of Avatar and Alice in Wonderland. Anne Thompson’s “Year-End Box Office Wrap 2010” quotes Don Harris, Paramount’s executive vice-president of distribution: “There are more screens, so a theater can now handle anywhere from two to three 3-D films at one time.” By year’s end, there were roughly 13,000 3D-equipped screens outside the North American market. The number of 3D films per year has grown from 2 in 2008 to 11 in 2009 to 22 in 2010 to an announced 30+ for this year.

Thompson also points out two other important strengths of 3D films: they sell a lot of tickets abroad, often earning three times as much as in the North American market, and they have led to theatrical income is “again the leading film revenue stream.” Of course, that’s partly due to the drop in DVD sales.

Yet for some the bloom seems to be off the rose. Low-budget exploitation films in 3D, films shot in 2D and converted for 3D release, filmgoer impatience with ticket surcharges and clunky glasses, and a general decline in the novelty value of 3D have all combined to leave its future still in doubt.

Before going more deeply into those problems, though, let’s look at the box-office successes, or apparent successes, of 3D films in 2010.

3D props up the box office

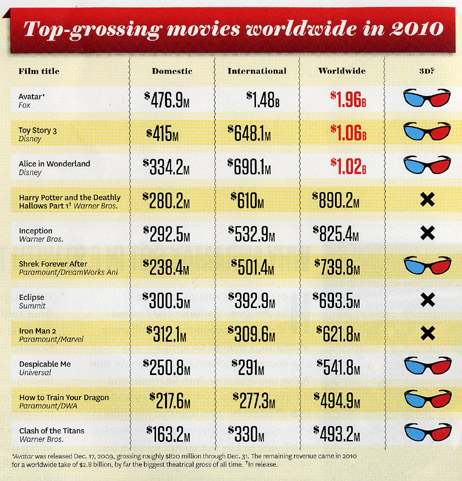

This week’s print version of The Hollywood Reporter heralds 2010 as “The year that was saved by 3D.” (For subscribers, the article is online, though it lacks the charts.) As Pamela McClintock, author of this excellent article, points out, “Of the top 20 films at the domestic box office, 11 were 3D titles (out of a total of 22 major 3D releases). Why the fat grosses? On average, a 3D title can expect to make 30 percent more because of the 30 percent upcharge for a 3D ticket.” (The accompanying chart, below, covers only the top 11 titles.)

(I will step in here and point out something that never seems to get mentioned in coverage of 3D, which is that part of that fee goes to pay for the glasses.)

Moreover, overseas markets, which have been making up an increasing portion of most big films’ worldwide grosses, are adding 3D screens like crazy. “The U.K., China, Russia, Japan, France, Germany, China and Russia in particular have seen a surge in digital-theater installations.” Given that the U.S. is still making more 3D films than most of these countries, Hollywood is getting a generous slice of that box-office income. Some films thought to be disappointments in the States did well worldwide, such as Clash of the Titans, with $493.2 million, and The Last Airbender, with $318.9 million.

Of course, there have been underperformers: Cats and Dogs: the Revenge of Kitty Galore, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, and Gulliver’s Travels, most notably. McClintock points out, “It’s almost certain that Deathly Hallows would have jumped the $1 billion mark worldwide had it been released in 3D, but Warners didn’t want to tarnish the franchise.” As it is, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1 has grossed $937,257,461 worldwide and is still in distribution.

Another thing that McClintock points out that most commentators ignore is that making a film in 3D adds to its budget, on average about $20 million for a two-hour feature. The alternative practice of shooting a film in 2D and then converting it to 3D is common. That costs about $100,000 or more a minute, or about $12 million for a two-hour film. (James Cameron, who ought to know, says a quality job would be $15 million or more.) For a movie that grosses in the hundreds of millions, that’s pretty small, but it’s not insignificant for a more modest film.

Let’s think about that for a moment. Jeffrey Katzenberg and James Cameron may still expect that all films will someday be made in 3D. But, to take one example I’ve seen people use in recent months, do we really think The Kids Are All Right would be enhanced by 3D? Even if some people do, the film cost only around $4 million to make and grossed a little under $30 million worldwide. Would $20 million spent on 3D cause it to gross over $50 million to make up the difference?*

Or does it?

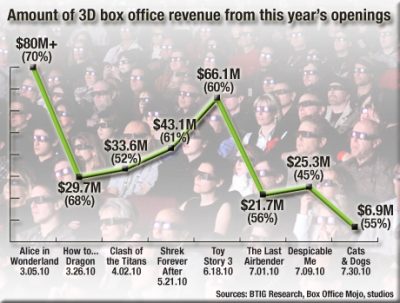

Despite the fact that 3D brought in higher grosses for the more successful films in that format last year, some experts are pointing to a decline in revenues over the year. In July of last year, Daniel Frankel published a widely cited chart called “The Rise & Fall of 3D” on The Wrap showing that since the release of Avatar the previous December, the proportion of the opening weekend box-office for major films coming from 3D screenings had declined:

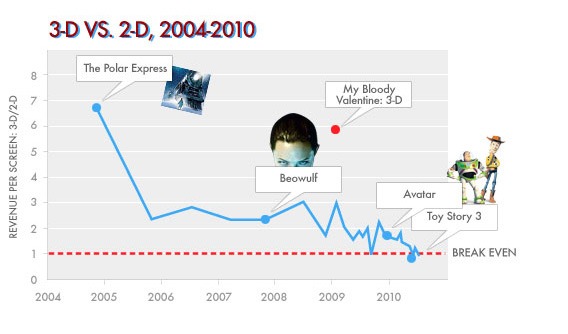

Then in August Slate posted a more detailed study by Daniel Engber bluntly entitled “Is 3-D Dead in the Water?” Engber took issue with Frankel’s chart saying that it did not reflect problems with a shortage of 3D screens available during the release of these films. But Engber didn’t disagree that 3D’s share of a film’s income has been falling. Quite the contrary, he thought it the decline was even greater. Taking a different approach that basically compares per-screen averages for 3D and 2D screening of the same film, he came up with a new chart:

The chart below—created with enormous help from Slate designer Holly Allen—shows the ratio of 3-D revenue to 2-D revenue, on a per-screen basis, for almost every major three-dimensional release going back to the beginning of the current revival.

Here’s the simplest way to interpret this graph: 3-D has been getting less and less profitable, relative to 2-D, over the past five years. It’s an ominous, downward trend that started long before Avatar and Alice in Wonderland and continued after. (The red dotted line represents a break-even point, where screenings in 3-D and 2-D theaters make exactly the same amount of money.)

(I can’t go into the details here, but Engber presents additional charts and information; it’s a must-read for anyone interested in 3D, pro or con.)

Last year the big complaint from Katzenberg and other 3D purveyors was that there weren’t enough theaters to screen all the films that were coming out in that format. Katzenberg is still not satisfied with the rate at which theaters are converting screens to 3D, but maybe exhibitors have realized that there is not as much future in it as they had been led to believe. Given that most multiplexes have two, three, or even four screens capable of showing 3D films, the rate of conversion is likely to slow, if it hasn’t already.

Toy Story 3‘s release seems to have marked the point where some industry analysts began to notice the downward trend in 3D revenues in comparison to 2D. Its opening offers an insight into whether the drop is real or just an apparent effect of too many 3D films vying for too few screens, as is so often claimed. Media financial analyst Richard Greenfield pointed out that the film’s percentage of revenue from 3D screens was 1% less than with Shrek Forever After (released May 21). Toy Story 3 had made 60% of its opening weekend box office on 3D screens, while Shrek Forever After (released May 21) had made 61% and Alice in Wonderland (March 5) had made 70%.

1% may not sound like a lot, but Toy Story 3 was released on the largest number of 3D screens of any film to that date. In that case, it could not be claimed that the drop resulted from too many 3D films jostling for screens. On the contrary, one would expect a rise.

Not only that, but Engber points out that the 2D versions of Toy Story 3 actually outperformed the 3D ones:

Then we come to the weekend of June 18, 2010, when Toy Story 3 opened in more than 4,000 theaters around the country. It was a huge weekend for the Pixar film—one of the biggest of all time, in fact, with more than $110 million in total revenue, and $66 million from 3-D. Yet a close look at the numbers shows something else: On average, Toy Story 3 pulled in $27,000 for every theater showing the movie in 3-D, and $28,000 for every one that showed it flat. In other words, the net effect of showing Woody, Buzz, and friends in full stereo depth was negative 5 percent. The format was losing money.

One could posit, of course, that the 2D screenings simply benefited from the overflow from sold-out 3D screenings. People who wanted to see the film in 3D had to settle. But that still doesn’t explain the drop in comparison to earlier films given the fact that Toy Story 3 opened on the largest number of 3D screens. At least two tickets to the film in 2D were sold to people who had the option of going to a 3D screening: David and me.

Engber goes on to consider some explanations for the decline, some of the same basic ones I’ll discuss here. He concludes that the situation is dire for 3D: “For mainstream movies that can be viewed in either format, the added benefit of screening in three dimensions is trending toward zero.”

Is 3D TV competing with theatrical or hurting it?

There seems to be an assumption that pop culture is headed toward a time when new media in general are delivered in 3D. The assumption is that 3D television will help boost sales of movies on DVD and Blu-ray. Maybe, but the sales of 3D TVs have been reported as lower than expected. According to a revealing article in Variety, Samsung projected that it would sell 3 million units in 2010 and sold less than 2 million: “According to several electronics makers, the biz will be concerned if the negativity continues six months from now.” Screen Digest’s year-end summary of 3D TV’s prospects (“After one year of 3D in the home,” December 2010 issue) points out that not only do 3D sets cost half again as much as 2D ones, but they are also mostly 44” or over, larger than most people can afford even in 2D sets.

That’s not the only cost holding back sales of sets. According to Variety: “The main reasons for holding out have been the pricey pairs of active-shutter glasses (sold for around $150 or more) that can be cumbersome to wear, easy to break and require batteries that run out. At the same time, there hasn’t been much 3D content to watch on the new sets.”

Sets with these active-shutter glasses come with one pair included. The things are bulky and require batteries. New 3D TV models are in the pipeline, some that work with lighter polarized glasses costing more like $20, with  four pairs included. As Bob Mayson president of consumer electronics for RealD (a major 3D theatrical supplier) told Variety, “You won’t have a Super Bowl party with active eyewear. With passive eyewear [i.e, those polarized glasses] you can buy a bag of glasses from Costco and be in business.”

four pairs included. As Bob Mayson president of consumer electronics for RealD (a major 3D theatrical supplier) told Variety, “You won’t have a Super Bowl party with active eyewear. With passive eyewear [i.e, those polarized glasses] you can buy a bag of glasses from Costco and be in business.”

Maybe guys who sit around drinking beer and watching the Super Bowl will get used to seeing each other wearing plastic glasses. Still, I have long been of the opinion that until 3D technology reaches a point where the glasses are unnecessary, the format can’t be universally viable. Toshiba and Sony have prototypes of such sets at technology fairs, but they reportedly won’t reach consumers for three to five years. I’m curious to know what the 3D effect will look like if you’re not sitting at exactly the right spot in front of the screen. From what I’ve read, you have to be positioned not only in front but also close. An excellent article in Wired summing up the obstacles to watching 3D on TV says the depth effect is limited to about four feet. In fact, there already are monitors for 3D without glasses (mainly available in Japan); they’re used mainly to display ads in stores. But in October Toshiba showed off two models intended for the home (left). The monitors are 12″ and 20″ and the optimum viewing distance is 90 cm for the larger monitor; that’s about three feet. They can project 3D to nine points in the room, but it sounds downright impossible for that many people to perch at precise points, all about a yard from the screen. Bigger versions will no doubt follow.

More content is coming for 3D TV, but again according to Variety, many content-providers are

focused on high-profile fare like sports and concerts, because as long as 3D TV requires glasses, it will only be used for event programming, not casual viewing. It may be tough to broadcast the Super Bowl in full 3D, outside of relying on a conversion, however, given that too many seats in the stadium would have to be removed for the 3D cameras. Networks could use robotic and remote-controlled 3D cameras but those are still too new of technologies to rely on yet.

Screen Digest ‘s year-end summary of 3D TV focuses on other obstacles, primarily the lack of content:

As recently as early September 2010 two thirds of the 21 3D BD [Blu-ray Disc] titles confirmed for US release in 2010 were tired to exclusive bundling deals with 3D hardware, leaving only seven available for purchase in store. By November, the total 3D BD slate had increased to 37 titles, 25 of which had been confirmed for retail sale by the year end. Furthermore, many of the biggest titles (including Avatar, the Shrek franchise, Monsters v Aliens, Ice Age 3) were still tied into exclusive bundles. By comparison, at the end of Blu-ray’s first year of availability (2006) 135 titles had been released on the format in the U.S.

I’m sure the brand partnerships between the TV makers and the studios have saved a lot in advertising, but it’s hard to imagine investing in a new technology when every time you want a popular film title, you have to buy a TV set to go with it. No doubt the availability of films to buy will increase, but the introductory approach seems a strange way to go about fostering interest in 3D movies on TV.

The Screen Digest article makes another interesting point. Initially, “3D in the home was conceived first and foremost as an attempt to mirror the revenues proven in the cinema—a 20 per cent premium over 2D features.” But much 3D TV content is also surprisingly like 2D TV content: “Ten percent of the cinema features have been dance or music, with a further four per cent including live sports and opera. This suggests an appetite for content that has traditionally been better suited to live television transmission than physical or cinematic tradition.” That further suggests that in the long run, people may be keener on 3D TV than on theatrical films in 3D—just the opposite of the studios’ hopes as they went in for 3D.

Beyond film and TV content, there is also the likelihood that 3D video-game playing through the large monitor will take up some of the time spent in front of the appliance. There’s also the fact that streaming or downloading 3D films requires far more bandwidth than 2D movies, though methods of compression are being developed.

The Screen Digest author predicts that by the end of 2014, 25% of American homes will have 3D TV. The question remains: What will people be watching?

Next week: Part two: RealDsgusted

*No doubt some cost-cutting is possible. Still, Tsui Hark’s Flying Swords of Dragon Inn (announced for a 2011 release), shot with the relatively inexpensive Red 3D digital camera, is budgeted at approximately $35 million. The difference between that and his usual cost per film could easily include $15-20 million for 3D. See Filmsmash for information and numerous photos derived from Chinese sites; the latter include images of the camera and of shooting in front of a green screen.

By Sam Spratt at Gizmodo

Motion-capturing an Oscar

Kristin here:

Six years ago, when The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King was nominated for eleven Oscars, there was considerable grumbling over the fact that Andy Serkis was absent from the acting categories. Many argued that his pivotal role in creating Gollum, the first convincing human-like computer-generated character, should have qualified him for a nomination.

Now we’re seeing a similar debate over the lack of actor nominations for Avatar, with Zoe Saldana’s performance as Neytiri especially mentioned as unfairly overlooked. An intriguing article on the subject appeared in the Los Angeles Times a few days ago. In it, James Cameron expresses annoyance with both the Screen Actors Guild and the Academy for the lack of nominations for his actors:

I’m not interested in being an animator. . . . That’s what Pixar does. What I do is talk to actors. ‘Here’s a scene. Let’s see what you can come up with,’ and when I walk away at the end of the day, it’s done in my mind. In the actor’s mind, it’s done. There may be a whole team of animators to make sure what we’ve done is preserved, but that’s their problem. Their job is to use the actor’s performance as an absolute template without variance for what comes out the other end.

Because of innovations in the motion-capture process, including a tiny camera hung in front of an actor’s face to capture its every nuance, Cameron insists on calling the new technology “performance capture.” In some sense it may be true that the performance is preserved, but once the film runs through the theater projector, can the audience really tell what that “template” was like? I think not, and that’s why there is a reluctance to nominate these actors.

Where is the elusive boundary?

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying that Zoe Saldana and Andy Serkis aren’t fine performers or that their acting did not contribute enormously to the characters they played. Indeed, Serkis’ mo-cap contribution to the creation of Gollum was originally intended to be far more limited than it turned out to be. His facial expressions and gestures were so useful to the special-effects people that he was involved for a much longer period, and techniques to allow him to perform onset with the other actors were developed.

But however fine the original acting and however great the aid it provides to the special-effects team are, the process doesn’t stop there. To a notable degree other factors intervene between the actors’ original performances and the characters’ final appearance on the screen. Let’s do some comparisons, using the publicity images that the studios themselves considered good indications of how close the expressions of original actors were to those of their characters.

Take the widely circulated image of Saldana juxtaposed with Neytiri shown above. There are numerous differences. For a start, the filmmakers obviously needed to make the Na’vi look like an alien species. They didn’t just give them tails and make them blue and really tall. Human as the creatures seem in many ways, their faces have a subtle suggestion of large felines.

The effectiveness of Neytiri’s snarl has a lot to do with the fact that she has been given exaggeratedly long canine teeth. Moreover, given the changes in the shape of the face, the mouth is not as large proportionately to the entire head as Saldana’s is; the tongue is not nearly as prominent or noticeable. Both tongue and lips are blue as well. All of these features allow the teeth stand out more by contrast.

Na’vi ears are pointed, and some of the lobes are apparently pierced with a small dark disk in the hole. Saldana’s ears played no role in her performance, but the laid-back ears in the Neytiri image, mimicking those of an enraged animal, contribute considerably to the shot’s impact. I remember noticing them while watching the film.

The nose and the wrinkles on and above it have been considerably changed. Unlike human noses, those of the Na’vi are smaller at the bottom than at the top, somewhat resembling lions’ noses. The wrinkles seem to be derived from canine or feline faces as well, extending from the inner end of the eye and arcing down toward the tip of the nose. The human frown lines at the lower center of Saldana’s forehead are transformed into larger, longer, curved wrinkles at either side; these start between the eyebrows and move up and to the sides. There they get extended by the curved areas of darker blue that radiate across the upper forehead, so that the lines of anger seem to cover more of the face. I suspect that relatively little of what the actors did with their noses has survived the special-effects processing. (In the image below, even the shape of Saldana’s naso-labial folds has been slightly altered.)

The change in the eyes is particularly important. Saldana’s eyes have dark irises within which the pupil is barely, if at all, visible. Na’vi eyes are much larger, to begin with, and the irises are light in color, a sort of yellowish tan. The irises fill more of the visible part of the eye, so that the whites of Na’vi eyes are minimized. As a result, the black pupil stands out dramatically. In terms of color, the model seems to be cats’ eyes, though the pupils remain round rather than slits, to avoid making the Na’vi too alien looking. Since the nose has been widened at the top, the eyes are also further apart than on human faces. (The norm with humans is for the eyes to be separated by a distance roughly equal to the width of one eye.)

Even in a less dramatic scene, when Neytiri is relaxed and smiling, some of these differences remain. The pointed ear is not laid back, but it sticks out from the side of the head at an angle that draws the spectator’s attention and makes the human-shaped face seem exotic–especially given that the Na’vis’ ears are placed higher on the skull than human ears are: while the human ear canal is about even with the cheekbone, in the Na’vi it opens at mid-temple level. Although the points of the canine teeth are not visible in this image, the teeth remain prominent because of their bright whiteness against the blue skin. Though partially masked by the headgear, the vaguely feline nose still differs considerably from Saldana’s. In keeping with the extraordinary height of these beings, Saldana’s neck has also been lengthened.

Again, I’m not saying that Saldana and the other actors in Avatar did not contribute enormously to the believability of their characters or that they did not aid us to empathize with them. On the contrary, although the big blue creatures did seem very odd in the trailers and posters, I have to admit that they quickly came to seem like real characters. Their design’s balance of human and alien is remarkable. I did not continually think of them as walking combinations of numerous elaborate special effects. The new facial-capture system renders expressions very well, as the frame at the bottom shows.

What I’ve pointed out here with relation to Saldana’s contributions to the creation of Neytiri applies as well to Serkis’ earlier contributions to Gollum. In the comparison images below, similar changes were made.

While Serkis’ ears were covered, Gollum’s are pointed and prominent. Here, too, the eyes have been enlarged and made a light blue so that the pupils stand out. Where the actor’s teeth are straight and even, Gollum’s are pointed, crooked, and separated by gaps. The cheeks have been hollowed and the eyebrows arched nearly to a point near their outer ends. Crucially, the body has been made inhumanly skinny, with long bony legs and arms that are not apparent in this image. I suspect that some naive audience members believed that a real actor had played Gollum, but to most the scrawny figure was a guarantee that no human could have performed the role. (The very thin waists of the extraterrestrials in District 9 served as a similar guarantee that these were not just guys in monster suits à la Invaders from Mars.)

With all the kinds of changes that I’ve pointed out, how would Academy members be supposed to judge these performances were they to be nominated in the traditional acting categories? Where is the boundary between acting and special effects? Despite actors’ and directors’ claims to the contrary, the movements and expressions caught by performance capture are changed in many obvious and not so obvious ways. A close inspection of the comparison photos reveals the details of the transformation, but in watching the film, the viewer cannot necessarily gauge what sorts of changes were made. I can well imagine that actors like Meryl Streep or Jeff Bridges would be justified if they objected to competing in the same Oscar category as what are essentially hybrid performances seamlessly combining the original acting and the digital transformation.

Possible new categories

One way I can imagine actors competing for awards would be for the Academy to create a separate category for motion-capture performances. To judge such performances fairly, the members would have to see videos running the original performance side-by-side with the finished film. This method might allow them to make a reasonable assessment of what the actor truly contributed.

At this stage in the history of film technology, such a category seems unlikely. So far, not that many people have been spoken of as deserving an Oscar nomination for a mo-cap performance. Even Bill Nighy, who was widely praised for his turn as Davy Jones in the second Pirates of the Caribbean film, was not touted as a possible nominee—probably because his face was so thickly covered with tentacles and partly because comic fantasy films tend not to be Oscar bait. So far the argument has primarily been made for Serkis and Saldana. Plus if the Academy did take the approach of requiring the sort of comparison film I’ve suggested, it would be a difficult and expensive thing to produce. Who knows whether Academy voters would watch five such films?

Maybe, though, as performance capture becomes less expensive and more widely used, there will be enough actors to make up a separate category. We’ve seen the animated-feature category grow from three to five nominees this year, and the number of such films being made suggests that five will become the norm. Animated films and live-action ones heavily dependent on motion-capture are somewhat similar technically, so a new category makes some sense.

A simpler and more logical alternative might be to create a category specifically for vocal performances. As has been pointed out in relation to animated films, an actor who is heard but never seen onscreen could in principle be nominated. Such a thing has never happened, but it’s not against the rules. (It’s easy to imagine that it could have happened for a performance like Celeste Holm’s unseen narrating character in Letter to Three Wives.) But with animated-feature and motion-captured performances becoming more common, a best-vocals category seems to make sense. After all, Serkis and Saldana and others like them do speak their characters’ lines, and their voices are typically not altered or enhanced very much. The digital manipulation of sound still lags considerably behind that of images.

The idea is not exactly a new one. The Annies, the awards given out each year by the International Animated Film Society, has two “Vocal Acting” categories, one each for film and television.

Very similar motion-capture technology can be used to create films that most people would agree are animated (The Polar Express, A Christmas Carol) and others that embed animated characters in a live-action setting (The Lord of the Rings, Avatar). Creating an Oscar category for vocal acting in animation or motion-captured, effects-based performances would make sense.

If actors are not yet being recognized for motion-captured performances, the Academy has been quick to honor the top scientific and technological innovators of the area of motion capture. In 2004, when The Return of the King won its golden statuettes, the less celebrated Academy technical awards included one to the Weta Digital team for its new approach to the creation of Gollum. (The award was shared with ILM for its similar use of the technique in creating Jar Jar Binks.) This year, on February 20, the Academy honored a team that included one Weta Digital member for “the design and engineering of the Light Stage capture devices and the image-based facial rendering system developed for character relighting in motion pictures” which was used on Avatar and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.

Despite fears that motion-capture may someday make directly photographed actors obsolete, there seems little chance of that happening. These techniques are fantastically expensive and are likely to remain that way for some time to come. There seems little point to using such elaborate technology to make an actor look like a real person when traditional cameras can do it so much more easily, so motion-capture performances seem suitable primarily for fantasy beings who cannot be as believably created in any other way.

Thanks to Cathy Root for calling my attention to the Los Angeles Times article.

February 25: See also Mark Harris’ essay in Entertainment Weekly. He argues that the ineffable qualities of an actor’s performance simply cannot be conveyed through motion-capture.

December 14, 2011: A member of the special-effects team at Weta Digital who worked on Avatar has sent me a comment on this entry: “Your Avatar article nails it–there were so many daily discussions about secondary ear and tail animation!”

May 18, 2014: Thanks to David Cairns for alerting me to two recent items on Cartoon Brew: Amid Amidi’s “Andy Serkis Does Everything, Animators Do Nothing, Says Andy Serkis,” which comments on an interview with Serkis on io9, and Amidi’s follow-up interview with Lord of the Rings animation supervisor Randall William Cook, which quite convincingly argues that the animators changed and extended Serkis’ performance.

Paris fun, in at least three dimensions

What he saves films from: Serge Bromberg faces down the flames.

We’re ending the first week of three in Paris. At the invitation of Jean-Loup Bourget and Françoise Zamour, David is giving three weekly lectures at the École Normale Superieure. He’s introducing some ideas about the development of film style in the 1910s and early 1920s, updated with new material from his summer research in Denmark and Brussels. Jean-Loup and Françoise have proven excellent hosts, and the first lecture seemed to go well.

We thought that Paris in January might be chilly and rainy, but we figured it had to be warmer than Madison. It turned out that Paris is experiencing unusually cold weather—about what would be normal in Wisconsin. There was light snow yesterday and last night, and the wind-chill factor was enough to turn our fingers numb if we stayed out long enough. The fountain in the center of the intersection at the northeast corner of the Jardin de Luxembourg has gradually become an iceberg.

We thought that Paris in January might be chilly and rainy, but we figured it had to be warmer than Madison. It turned out that Paris is experiencing unusually cold weather—about what would be normal in Wisconsin. There was light snow yesterday and last night, and the wind-chill factor was enough to turn our fingers numb if we stayed out long enough. The fountain in the center of the intersection at the northeast corner of the Jardin de Luxembourg has gradually become an iceberg.

Turns out, though, that it is still warmer than Madison, which is having highs in the single digits, as the weather forecasters say, and lows below zero. We’re better off here, though we wish we had brought our parkas.

It’s like Avatar, but much shorter

KT here:

The cold has driven us indoors, to museums and movies. As always seems to be the case, the Cinémathèque Française is hosting retrospectives of American films—in this case works by Laurel and Hardy and Gordon Douglas. There’s also a 3D series, which caught our attention right away. It’s not just your standard Kiss Me Kate and Dial M for Murder programming. In addition to such classics, there are many obscure films. We happened to arrive in time for the final two programs of the series, which ran from December 16 to January 3.

Our first full day in Paris ended with an evening of shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who in 1985 founded Lobster Films. Lobster has put out many DVDs by now, some of which we have reported on previously, here and here. In July, one of our entries on Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna mentioned that Serge presented a program of Georges Méliès films, in conjunction with the French release of Lobster’s huge DVD set of the great magician’s films.

Serge is quite a showman and obviously a popular figure, since there was a large crowd, including many families with children. On Saturday he chose and introduced a set of short 3D films in his series of programs usually titled “Retour de Flamme,” or “Saved from the Flames.” To begin the evening’s entertainment, he explained how, unlike modern celluloid 35mm film, the nitrate variety used up until the early 1950s ignites and burns easily. With the help of a rightly apprehensive volunteer holding up a film-can lid, Serge showed how modern celluloid catches fire only briefly and then dies out. The few inches of nitrate, however, flared up quickly.

Serge introduced each film thereafter, playing the piano to accompany the silents. The audience had been given both anaglyph (red-green) and polarized glasses, and Serge’s introductions to the films gave us time to switch between systems.

Many of the shorts shown on the program are available on DVD or YouTube, but the 3D effect plays best on the big screen. The evening began with an unannounced item, Three Dimensional Murder, a “Metroskopics” comedy short from 1942. A nervous detective visits a mysterious house and encounters Frankenstein, creeping hands, skeletons, and other ghouls and beasties, all of which find some occasion to throw things or hurl themselves toward the camera. The humor is, as a contemporary audience member might have said, pure corn and the 3D effects repetitive, but it was certainly a rare item.

Next came one of the Fleischer brothers’ cartoon shorts, Musical Memories. It was made with a patented system that used three-dimensional models as settings against which 2D cartoon figures drawn on cels moved about. (Such models can be seen fairly often in Popeye and other Fleischer cartoons of the 1930s.) There is some sense of depth. Still, the effect is strange, since the models have shading and the flat-looking figures do not. The cartoons are not 3D in the sense we typically think of, since there are no glasses involved.

More cartoons followed, from the two main competing animation studios. Disney’s contribution was Working for Peanuts, a story set in a zoo with Chip and Dale stealing peanuts from an elephant and Donald Duck trying to foil them. Many a peanut seemed to fly out toward the spectator. Chuck Jones directed Lumber Jack-Rabbit (1954), a film that mixed size gags and spatial ones, with Bugs wandering into the domain of the gigantic Paul Bunyan. Perhaps not one of Jones’s best, but distinctly more interesting in 3D.

As Serge pointed out, most 3D technology was pioneered in the U.S. He included some exceptions, however, with a series of Soviet “Parade of Attractions” shorts shown at intervals during the evening. Experiments with underwater 3D photography and a garden of plants lacked soundtracks, but the final item, a vaudeville act with jugglers, had music and lots of bowling pins flying at the camera.

Unbelievably, there were efforts toward 3D as early as 1900. Serge showed some 3D experiments from that period by inventor Rene Bunzli. These were only about 10 seconds long and included a mildly risqué scene of a man arriving to visit his mistress and another discovering his wife in bed with her lover. The first color 3D film was shown: Motor Rhythm, made by Charley Bowers in 1940 for the Chicago Exposition and distributed by RKO. Using a combination of pixilation and 3D, the film shows a car jauntily assembling itself to a musical accompaniment, with many of the parts moving out toward the camera before attaching themselves in their proper places.

The National Film Board of Canada contributed Munro Ferguson’s Falling in Love Again, with characters wafted into the sky by road accidents and, while falling, falling in love. To watch it in high-quality 3D, go here. Pixar was represented by John Lasseter and Eben Ostby’s early digital experiment in 3D, Knick Knack, as a snowman trapped in a snow globe tries to break free to join a bathing beauty.

The evening ended with a surprise, two films that had never been meant to appear in 3D.

Méliès’s early shorts were often pirated abroad, and a lot of money was being lost in the American market in particular. After the Lubin company flooded that market with bootleg copies of a 1902 film, Méliès struck back by opening his own American distribution office. Separate negatives for the domestic and foreign markets were made by the simple expedient of placing two cameras side by side. The folks at Lobster realized that those cameras’ lenses happened to be about the same distance apart as 3D camera lenses. By taking prints from the two separate versions of a film, today’s restorers could create a simulated 3D copy!

Two 1903 titles–I think that they were The Infernal Cauldron and The Oracle of Delphi–triumphantly showed that the experiment worked. Oracle survived in both French and American copies, and the effect of 3D was delightful. For Cauldron only the second half of the American print has been preserved. Watching the film through red-and-green glasses, you initially saw nothing in your right eye, while the left one saw the image in 2D. Abruptly, though, the second print materialized, and the depth effect kicked in. The films as synchronized by Lobster looked exactly as if Méliès had designed them for 3D.

Film scholars gone wild

DB here:

William Cameron Menzies is most famous as an art director on films like The Thief of Baghdad (1924) and Gone with the Wind. He was one of the most visually daring artists to work in classic Hollywood; his eccentric framings and looming foregrounds may have influenced Orson Welles. (The Gothic distortions of Our Town and Kings Row are unlikely to be the creation of director Sam Wood.) Menzies also directed a few films, most notably the slightly nutty anti-Commie film The Whip Hand (1951).

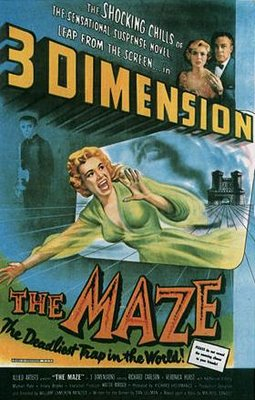

So Kristin and I had to go back to the Cinémathèque for Menzies’ rarely-seen 3D feature The Maze (1953). Alas, it was a washout. The feeble story concerns an heir returning to a castle to confront a giant frog, who may be his relative. I’d expected bravura deep-focus, with planes jutting out at me, but the film was dramatically and visually flat–no wordplay intended. The trailer, complete with fake bats on strings, is here.

We have other incidents to chronicle, but this dispatch can end with a quick list of some of the film friends we’ve encountered. We’ve already mentioned Professor Bourget, whose book on Fritz Lang came out recently (below left). We also ran into Cindi Rowell, an old friend from Pordenone and The Griffith Project, who had the excellent idea that we go to Chinatown–here hidden behind the facades of tower blocks. Cindi has vast experience in many aspects of film culture–preservation, programming, publication, web design, and the like–and is currently affiliated with the Middle East International Film Festival in Abu Dhabi.

Another old friend, Yuri Tsivian, is in Paris teaching during our visit, so we had a chance for a good dinner and lots of talk about editing in the 1910s. Below, he and Kristin pay homage to one of the shrines of Parisian cinephilia, the Studio des Ursulines movie theatre.

Left: Jean-Loup Bourget and his new book on Lang. Right: Yuri and Kristin at the Urselines.

Last night, with Kristin away in Berlin, I went to a dinner hosted by Jacques Aumont and Lyang Kim. Jacques is a major film theorist, whose many books and essays probe into the artistic qualities of cinema. His book on Eisenstein is available in English translation, as is his far-ranging study of the history and functions of images. Lyang is an outstanding photographer, whose book of haunting Christmas images Dans l’ombre de noël was just published in December. Among her pictures here are some gorgeous “fusion” images that recall our recent 3D experiences.

Then who should turn up but Marc Vernet and Rick Altman? It was an Iowa-Wisconsin reunion in the 10th. Marc is an expert on film noir, on cinematic images of absence, and on the American film company Triangle–associated with both Griffith and Ince. (Again, the 1910s.) Marc has set up a beautiful webpage full of information about early American cinema, and he blogs there frequently. Rick is known for his in-depth studies of film genre (especially the musical), film sound, and narrative theory. His most recent books, Silent Film Sound and A Theory of Narrative, are splendid contributions. Below, all four toast what turned out to be Rick’s birthday.

Today: More preparations for my lecture tomorrow, and of course at least one movie. Agora? Wiseman’s La Danse? Kinatay? The new Eugène Green, La religieuse portugaise? Or a rerelease (new print) of Minnelli’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse? Or….? The usual Parisian problem, but a good problem to have.

P. S. March 2010: After this Paris trip, I wrote an essay on William Cameron Menzies for this site.

Jacques Aumont, Lyang Kim, Rick Altman, and Marc Vernet, 9 January 2010.

Has 3-D already failed?

Kristin here–

Years ago, James Cameron announced that his upcoming film, Avatar, would only be released to theaters capable of showing it in 3-D. Since then, he has proselytized fervently at trade shows and fan cons, hoping that Avatar would be such a blockbuster that exhibitors would finally decide to make that expensive leap and invest to convert their auditoriums to add 3-D.

Many commentators seemed to assume that Cameron’s saying such a thing would make it so. Here’s what Popular Mechanics opined only a little over a year ago:

Cameron’s insistence on 3-D projection will likely force the industry to ramp up the installation of 3-D technology dramatically. “Cameron is going to be able to bully theaters into compliance,” says former Premiere magazine critic Glenn Kenny. “He’s got the clout, and he’s got the mojo to do it. Everybody is going to want his next film.”

Avatar will need about 4,000 screens for a 3-D-only release, estimates Doug Darrow, manager of DLP brand and marketing at Texas Instruments, which makes the chips that power theatrical 3-D projectors. Of course, once the Avatar-inspired infrastructure is in place, other 3-D-only releases will follow.

The problems with conversion are manifest. Number one is the expense. 3-D systems are digital, so first the theater owner must convert from 35mm projectors to digital. 3-D is an add-on system that entails additional expenditure. A digital conversion alone costs over $100,000, about five times the cost of a 35mm platter projector. Right now most “D” theaters have 2K projection, but 4K is gradually being introduced for both shooting and showing. (Che and District 9 were shot mostly on 4K.) What theater owner wants to buy an expensive projector that will be obsolete within a few years? And what was supposed to be the breakthrough year for 3-D sees us at what may be the bottom of a huge financial crisis. It has slowed down an already laggardly process.

Among commentators, there’s apparently a lot of support for Cameron’s position. This year, coverage of Avatar has been considerable and has mostly echoed his prediction that this is the future of cinema. Geeks who tend to love special-effects-heavy sci fi and fantasy films also tend to long for all of those films to be 3-D. Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings cannot be converted into 3-D fast enough for them. They run websites to express their fervor and to report every new technical innovation and every rumor about a future film perhaps being made in 3-D.

I’ll admit that the signs that 3-D is finally going to become a routine and frequent method for making and exhibiting films are clearer than ever this year. More theater chains are announcing conversion to digital projection after years of resistance. More films in 3-D, and good films, are appearing, like Coraline and Up. And I have to admit that I enjoyed Monsters vs. Aliens more than its tepid reviews had suggested I might.

But there are negative signs as well. Perhaps most notably, the major proponents of 3-D, after years of berating the exhibition wing of the industry for its slow adoption of digital and 3-D technology, are still berating it. Jeffrey Katzenberg, who had announced that all Dreamworks Animation features would henceforth be made in 3-D, is one such complainer. Cameron is another. As of now, roughly 320 of the U.K.’s 3600 screen are digital—which doesn’t entail that all have 3-D capacity. In the U.S. it’s 2500 out of 38,000.

These days, a major blockbuster may open on 4000 screens or more. Given Avatar’s massive budget, rumored at $237 million (not counting prints and advertising), Twentieth Century Fox couldn’t settle for showing only in 3-D, even if every properly equipped screen in the country showed it.

The recent theatrical free previews of scenes from Avatar in 3-D have renewed the claims that this approach is the future. Yet some commentators are cautious about that claim. The Guardian quotes Louise Tutt, deputy editor of Screen International: “It seems a little overambitious,” she says. “A little over-enthusiastic. I mean, take a film like 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days – who needs to see that in 3-D? So no, I don’t believe it will happen.” She sighs. “But then who am I to contradict James Cameron?”

Cameron is a mighty force for change, no doubt. The Abyss and Terminator 2 introduced the sort of morphing technology that made digital effects a reality. But oddly, there aren’t a lot of other directors quite that gung-ho about 3-D. They’re willing to praise it and suggest that they may make films in 3-D, but they don’t go around to trade shows pressuring exhibitors to convert their theaters.

Peter Jackson, for example, keeps hinting at such a possibility. Apparently his team is testing the new Red camera’s 3-D model with an eye to using it in the remake of The Dambusters. That’s slated to be produced by Jackson and directed by Christian Rivers. But if Jackson were as enthusiastic about the process as Cameron, wouldn’t The Lovely Bones be in 3-D? Steven Spielberg hasn’t been pushing 3-D, although there are rumors about the Tintin films being 3-D. But rumors and expressed interest don’t influence exhibitors reluctant to invest in upgrading theaters on the basis of the still-limited 3-D product that’s out there so far. Where’s Ridley Scott in this debate? Well, to be fair, he called the Avatar footage “phenomenal,” but I don’t see him making 3-D movies and demanding that they play only in properly equipped theaters. Where’s Tim Burton? Even George Lucas, Mr. Digital Technology, who keeps saying that Star Wars will be converted to 3-D, doesn’t have Cameron’s zeal.

Retro-fitting movies is hugely expensive, by the way. One of the few retro-fitted titles, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare before Christmas, has taken to returning annually, as if to remind us of that fact.

Even Pixar, which has said it will henceforth make all its films in 3-D, has been strangely low-key about its current project of re-doing the first two Toy Story films in 3-D and re-releasing them as a lead-up to the premiere of the third film, planned in 3D from the start. (This year the first two will be shown at the Venice film festival, which has added a 3-D prize.) Presumably they are content to provide both 3-D and 2-D prints.

We’re also not seeing a lot of directors in other countries clamoring for the option of making their movies in 3-D. Hollywood may dominate world cinema in terms of screen time occupied and tickets sold, but there are still thousands of movies made elsewhere each year.

There are still few enough theaters in the U.S. capable of showing 3-D movies that films end up with truncated runs. Coraline perhaps suffered most from being taken off screens while it still had commercial potential and before word of mouth had time to help it gain the audiences it deserved. The release of the partially 3-D Imax version of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince was delayed by the fact that Transformers 2 was still occupying Imax theaters. I can’t help but wonder if there are some studio executives who look at this situation and, without announcing it to the world, decide that the films they’re about to greenlight will be made in 2-D. Plenty of those theaters to go around. (Well, not for all the independent films jostling each other in the market, but that’s another blog topic.)

Cameron has bowed to the inevitable and is allowing Avatar to play in both 3-D and 2-D theaters. It seems obvious that it will still take years before a film can go out into the world without 2-D 35mm prints being included in its distribution.

During those years, there’s the potential that 3-D will lose its luster for audiences. One of the main arguments always rolled out in favor of conversion is that theaters can charge more for 3-D screenings. Proportionately, theaters that show a film in 3-D will take in more at the box-office because they charge in the range of $3 more per ticket than do theaters offering the same title in a flat version.

But what happens when, say, half the films playing at any given time in a city are in 3-D? Will moviegoers decide that the $3 isn’t really worth it? Even now, would they pay $3 extra to see The Proposal or Julie & Julia in 3-D? The kinds of films that seem as if they call out for 3-D are far from being the only kinds people want to see. Films like these already make money on their own, unassisted by fancy technology.

Then there’s the fact that the extra $3 is not simply profit. There has to be an employee handing out the glasses, though sometimes the ticketseller does that. And those glasses in themselves cost money. Some will get damaged. When David and I saw Monsters vs. Aliens, there was a woman with a child, perhaps four years old, in front of us in the concession line. She handed both pairs of glasses to the kid while she dealt with paying for the refreshments. He had his fingers all over the lenses, of course.

If a theater is using the RealD 3-D system, it’s no big deal if kids with sticky fingers get hold of the glasses. They are so cheap as to be disposable, if the theater doesn’t want to bother collecting and re-using them. Problem is, the theater has to buy or rent a special silver screen to project on. The Dolby 3D system doesn’t require a special screen, but its glasses cost a whopping $50 apiece as of 2007. In Dolby theaters, you’ll find tense ushers waiting outside, making absolutely sure everyone returns theirs for washing and re-use.

[September 9: A Dolby representative informs me that the cost of the company’s glasses is currently $27.50, well as this information:

- The Dolby 3D glasses are high-performance, eco-friendly passive glasses that require no batteries or charging and can be reused hundreds of times without sacrificing image quality.

- The environmentally friendly and reusable glasses can be used repeatedly, significantly reducing the cost down to cents per pair per screening for exhibitors.

Thanks, Erin.]

No doubt 3-D enthusiasts would object that someday the system will be so routine that we’ll all have our own glasses and bring them along. That would cut the expenses to the theater, to be sure. But remember, different 3-D systems require different kinds of glasses. Are audiences willing to collect one of each and keep track of which they need to take along when they head for the theater—especially those $50 ones? (“Check the theaters listings, honey. Is it RealD or Dolby tonight?”) And there are more competitors entering the market, with their own glasses.

Is current audience enthusiasm permanent?

As usual, the studios take box-office figures to equal enthusiasm on the part of fans. In public, at least, they don’t speculate as to whether 3-D might again be, as it was in the 1950s, a mere fad or a specialized taste. But because spectators are willing to pay extra now because 3-D is still a novelty, does that mean they’ll maintain that attitude once 3-D is common?

Maybe not. And maybe even now not all filmgoers care. Some even dislike 3-D.

One vocal critic is Roger Ebert. His “D-Minus for 3-D” blog entry is an eloquent takedown of the technique on aesthetic grounds. He just doesn’t like watching movies in 3-D:

One vocal critic is Roger Ebert. His “D-Minus for 3-D” blog entry is an eloquent takedown of the technique on aesthetic grounds. He just doesn’t like watching movies in 3-D:

In my review of the 3-D “Journey to the Center of the Earth,” I wrote that I wished I had seen it in 2-D: “Since there’s that part of me with a certain weakness for movies like this, it’s possible I would have liked it more. It would have looked brighter and clearer, and the photography wouldn’t have been cluttered up with all the leaping and gnashing of teeth.” “Journey” will be released on 2-D on DVD, and I am actually planning to watch it that way, to see the movie inside the distracting technique. I expect to feel considerably more affection for it.

Ask yourself this question: Have you ever watched a 2-D movie and wished it were in 3-D? Remember that boulder rolling behind Indiana Jones in “Raiders of the Lost Ark?” Better in 3-D? No, it would have been worse. Would have been a tragedy.

He refutes the widespread argument in favor of realism:

There is a mistaken belief that 3-D is “realistic.” Not at all. In real life we perceive in three dimensions, yes, but we do not perceive parts of our vision dislodging themselves from the rest and leaping at us. Nor do such things, such as arrows, cannonballs or fists, move so slowly that we can perceive them actually in motion. If a cannonball approached that slowly, it would be rolling on the ground.

It’s true that the “coming at you!” effects in 3-D movies are disruptive. I remember the 3-D in Bwana Beowulf, excuse me, Beowulf primarily for those weapons thrusting out of the screen or the gratuitous overhead tracks past beams looking down toward the distant floor. More interesting, though, is that fact that although I saw Coraline and Up in 3-D, I remember them in 2-D. Those films didn’t throw spears at the spectator or otherwise seek to pierce that fourth wall with their props. Of course as I was watching, I noticed that the mise-en-scene had layers of depth and the figures a rounded look, but apparently my life-long movie habits filtered those aspects out as the films entered my memory. I look forward to seeing both films again on DVD, and given the fact that home-theater 3-D is still in its very early stages, I’ll probably see them flat. Fine with me.

Yes, Coraline was carefully designed with 3-D effects in mind, playing with skewed perspective to characterize the two worlds the heroine moves between. But as David showed by reproducing a frame here on our merely 2-D blog, the same motifs worked without the glasses. They’re quite similar, in fact, to the forced or distorted perspective used in German films of the 1920s.

We saw District 9 this week. No 3-D, and I for one am glad about that.

On August 26, TheOneRing.net, the premiere Tolkien site on the internet (for both novels and films), pointed to the current results of its ongoing poll. They asked, “Should the Hobbit films be in 3-D?” Many of the fans who frequent TORN do so because of the films. They have heard rumors over the years, mainly hints dropped by Peter Jackson, that The Hobbit might be made in 3-D. So what is their reaction as reflected by the poll? As of August 26, 55% say no, 13% say emphatically no (“Ugh … 3-D?”), 13% are sitting on the fence, and 13% say yes.

[Aug. 29: For some reason the poll “Should the Hobbit films be in 3-D?” has disappeared from TORN. It has been replaced by a discussion of the poll results on a discussion thread in the Message Boards.]

TORN subsequently checked with director Guillermo del Toro, who reassured them, “I can safely say that, as of this moment, there are absolutely NO conversations about doing the HOBBIT films in 3D.”

Of course, my title, “Has 3-D already failed?” was meant to be provocative. Its answer depends on how one defines success. If you’re Jeffrey Katzenberg and want every theater in the world now showing 35mm films to convert to digital 3-D, then the answer is probably yes. That goal is unlikely to be met within the next few decades, by which time the equipment now being installed will almost certainly have been replaced by something else.

Right now, the big proliferation is in tiny personal screens, iPod Touches, cell phones, portable gaming devices. Will teenagers allow themselves to look dorky by sitting with 3-D glasses staring at their phones? 3-D has the effect of making films that won’t play well on the very devices that studio heads would love to see playing their movies. So far, it is a remarkably inadaptable technology to try and force on people whose movie-playing gadgets change every few years. The big break-through, home-video 3-D, is aimed at a machine that people are supposedly abandoning in favor of other screens. 3-D movies on your computer? So much for inviting pals over for a sociable evening of popcorn and a movie in your impressive home theater.

Maybe Hollywood will forge ahead, despite all the obstacles I’ve mentioned. But it also seems possible that the powers that be will decide that 3-D has reached a saturation point, or nearly so. 3-D films are now a regular but very minority product in Hollywood. They justify their existence by bringing in more at the box-office than do 2-D versions of the same films. Maybe the films that wouldn’t really benefit from 3-D, like Julie & Julia, will continue to be made in 2-D. 3-D is an add-on to a digital projector, so theaters can remove it to show 2-D films. Or a multiplex might reserve two or three of its theaters for 3-D and use the rest for traditional screenings.

If that more modest goal is the one many Hollywood studios are aiming at, then no, 3-D hasn’t failed. But as for 3-D being the one technology that will “save” the movies from competition from games, iTunes, and TV, I remain skeptical. Given the banner year that Hollywood is having, I echo Daffy Duck in The Scarlet Pumpernickel when after his lover picks him up and, crying “Save me,” races from her forced marriage, he says,“So what’s to save?”

[September 17: On the occasion of the 3D Entertainment Summit, Variety has posted an article on the subject. It deals mainly with the losses of revenue from the fact that there are too many 3-D films jostling for too few equipped screens, saying that the format “is in danger of becoming a victim of its own success.”]