Archive for the 'Actors: Fairbanks' Category

Despoiling the movies

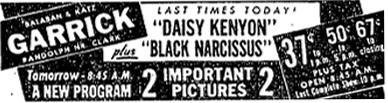

The Denton Record-Chronicle (28 December 1947).

DB here:

The last line of Otto Preminger’s Daisy Kenyon is “When it comes to modern combat tactics, you’re both babies compared to me.” If you haven’t seen the film, does knowing that ruin it for you? Suppose I went further and identified the character who spoke the line, or the immediate circumstances, or the action leading up to it? Would knowing these things ruin your pleasure? Or would it give you a different sort of pleasure?

Who doesn’t come to Casablanca knowing about “Here’s looking at you, kid,” or “Play it, Sam,” or “Round up the usual suspects”? You likely saw the ending of King Kong in compilation films before you saw the whole movie, yet you probably still watch it with enjoyment. I saw Potemkin’s Odessa Steps sequence many times, on an 8mm reel I bought as a kid, before I saw the whole movie. I still enjoy Potemkin, possibly more than many who see it for the first time. Yet people complain about trailers that tell too much, and critics who give plot twists away. Accordingly, it’s been a convention of fan and Net writing that if you’re going to give away major story information, you alert readers with the word “spoiler.”

Surely people want to know something about a film’s story. Viewers clamored for the most basic information about Super 8. And evidently many moviegoers would feel less disgruntled about The Tree of Life if they had known in advance a little bit more about what they would encounter. It seems we want to know about the story’s basic situation, but not too much about how things develop. Say: bits from the first half-hour or so, up to the beginning of the Second Act (or what Kristin calls the Complicating Action). Beyond that, we want things kept quiet. Above all: Don’t tell the how things turn out in the end.

I’ve been driven to think again about spoilers after Jonah Lehrer reported on an experiment with literary texts. On the whole, readers in the study reported enjoying a short story somewhat more if they knew the ending in advance. Jim Emerson has provided his characteristically stimulating commentary on this finding, and his readers, surely among the most reflective in the online film community, have supplemented his thoughts.

This discussion overlaps with a question I raised a while back on this site. How can we feel suspense if we know a story’s outcome? One standard answer, which would apply to spoilers too, is that even with foreknowledge, we’re interested in how that turn of events comes about. This possibility is invoked by some of Jim’s readers, and it seems plausible, especially if one is a connoisseur of storytelling. How, we ask, does the narrative engineer this or that twist?

My further proposal in the blog entry was that our mind’s intake of narratives is modular in some respects. Part of us reacts as if we were encountering the events fresh, without knowledge of what is coming up. The analogy was to standing on a balcony overhanging a precipice. You know that you cannot fall, but when you imagine yourself falling, you feel a twinge of fear all the same.

The same might be true of consuming a narrative. One of our mental systems, fast but fairly dumb, reacts to things as they come, while secure knowledge hovers more distantly in the background. I suggested as well that the way that something is presented–say, with fast cutting or sweeping music–can override our knowledge and kindle a basic, more visceral response.

Today’s entry tackles the matter of foreknowledge from a different angle. It’s worth remembering that many people who went to the movies in the 1920s through the 1950s willingly subjected themselves to spoilers.

This is where we came in?

Chicago Daily Tribune (4 January 1948).

While the American studios developed their storytelling strategies in the 1920s and 1930s, movie exhibition became a big business. In 1935, eighty million Americans went to the movies every week. The historical high point was 1946-1948, when annual attendance hit 4.7 billion. But how did all those people see the movies? More specifically, did they watch them from start to finish?

We’re so used to showing up at a definite time for a screening that it’s hard to imagine a period when many viewers would simply drop in to what were called “continuous admissions” or “continuous performances.” In major cities, the film programs, complete with newsreels, cartoons, trailers, other shorts, and even a second feature, would run steadily with only brief intermissions. You could drop in any time.

When the houses filled up, prospective viewers would have to wait in line outside or in the lobby until someone left. Then an usher would show the next patron to the empty seat. Meyer Levin’s novel The Old Bunch describes a group of friends waiting forty-five minutes before just getting into the lobby of a Chicago theatre in the 1920s.

Some of the viewers would depart during the main or second feature. Naturally, the patrons admitted in medias res would see the end of a movie before they caught up with the beginning, perhaps some hours later. Hence the phrase, “This is where we came in,” meaning, “Now we’ve seen the whole picture and can leave.”

After Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema, a few readers asked why we hadn’t talked about continuous admissions. The practice would seem to explain a lot about the redundancy of Hollywood storytelling. Hyperexplicit exposition, the Rule of Three (say everything important thrice), and the habit characters have of reminding us of their relations to each other (“Gee! You’re the swellest sister a guy ever had!”)—all this would seem to be aimed at a viewer who might well have come in halfway through and need orienting to basic plot premises.

We knew about continuous performances, of course, but we didn’t discuss them because we could find no evidence that filmmakers took these conditions into account when designing their stories. In reading Hollywood screenplay manuals, technical journals, and the like, I didn’t find anyone commenting on the exhibition practice. My colleague Lea Jacobs, who has scanned Variety very comprehensively for the 1920s and 1930s, can recall no mentions of it affecting production policies.

When you think about it, screenwriters and directors couldn’t really do much to bring a latecomer up to date. You can’t keep reiterating story premises and recapitulating all that went before, and still move the plot forward. Better to tell the story straightforwardly and assume, as a default, that under ideal circumstances people would see the whole film from scene one onward. The same assumption governs TV writing, despite viewers’ channel surfing and foreplay with the remote.

Still, during the Golden Age of Hollywood a significant population consumed movies knowing how the story turned out before they saw the beginning. Ask people of my generation or older, and you’ll usually hear: “Oh, we went whenever we wanted. We never tried to find the showtimes.” My childhood moviegoing memories are dim, but I recall being dropped off at the Elmwood Theatre by my parents when they went to town. I’d go in during the movie (I do recall The Sad Sack, 1957) and watch until my mother or father fetched me out. It’s very likely that adults drifted in at odd times as well.

There’s harder evidence that some people preferred convenience to coherence. In 1950 Twentieth Century-Fox announced that All About Eve (1950) would be screened only in “scheduled performances.” No one would be seated after the film began. Premiering at Manhattan’s Roxy Theatre, Eve ran for a week under the new policy. It failed. People hadn’t heard about the new rules, showed up late, and weren’t admitted. The results were angry lines outside and empty seats within. The practice was halted and Eve screened in continuous performance. The Hollywood Reporter attributed the failure to “the public’s deeply ingrained habit of going to a movie show at any desired hour, when most convenient or on impulse.”

In other words, many people were encountering what we call spoilers all the time, and it didn’t seem to bother them. So you wonder: Is watching a movie straight through, as we mostly do today, a newer, more “disciplined” mode of consumption?

It’s showtime

Daisy Kenyon.

It’s obvious that the custom of just dropping in didn’t guarantee a nonlinear movie experience. With a double-bill house, even if you dropped in arbitrarily, you would see one feature or the other in a single gulp. And assuming a three-hour program and a 90- or 95-minute A picture, your odds of walking in during the shorts or the B film were about fifty-fifty.

But were people obliged to drop in willy-nilly? Could they have seen the movie straight through if they wanted to?

There’s considerable evidence that parts of the audience did want to see the movies in linear fashion.Consider the early attenders. And many cinemas filled up quickly just before the show started. Coming in when the theatre opened seems a fairly clear indication of wanting a linear experience. True, early attenders would probably have to sit through a newsreel, trailers, and other shorts, but many people enjoyed those too. Further, since double-bill houses screened the A picture first, knowing that custom could guide your decision about when to come in.

Could patrons have gained specific information about when the movies were screening? There’s a widespread belief that theatres didn’t publicize showtimes. But that’s not the case.

First, the box office almost always posted a schedule breaking down the program. Sometimes cardboard clocks with movable hands indicated showtimes. Patrons might see the schedule when they arrived, or while passing the theatre during the day. Knowing the schedule, you didn’t have to go straight in. If you bought your ticket while the feature was running, you could linger in the lobby. Probably some viewers were reluctant to enter if the feature they wanted to see was just ending.

Second, there were newspaper advertisements. This evidence is varied and intriguing, full of unexpected quirks. First, I took a look at late 1940s ads for the Elmwood, my hometown venue. These ads are mostly bare-bones. They list the movies, all double features, with three changes a week (films played Friday-Saturday, Sunday-Monday, and Tuesday-Thursday). The theatre doesn’t supply its phone number, probably because many families in our area didn’t have phones until the late 1950s. Showtimes are seldom mentioned. Doubtless townfolks knew by local custom what the showtimes were, and there was no need to advertise it in newspapers or handbills (which were still around in the 1950s). One September 1949 item specifies opening and closing hours:

Matinees Daily 2:00

Evenings 7:00 to 11:30

Sundays and Holidays Continuous 2:00 to 11:30

Knowing these hours of operation, people who wanted to see the movies straight through could show up at 2:00 or 7:00.

Knowing these hours of operation, people who wanted to see the movies straight through could show up at 2:00 or 7:00.

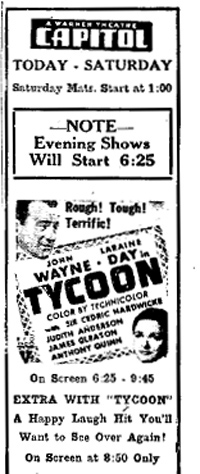

But some ads in other towns get a little more specific. “2 COMPLETE SHOWS 9:30 & 12 MIDNITE,” blares the Colonia of Norwich, New York in 1947. This indicates the starting times for the newsreel, cartoon, and ads, which all preceded the main feature. But since many theatres began their screening at 6:00, the accompanying ad from the Capitol, of Dunkirk, New York in 1948 seems to be saying that after all the shorts and ads, Tycoon hits the screen at 6:25. That movie ran a little over two hours, so there was time for filler leading up to the Happy Laugh Hit (presumably a revival). More unequivocal is the ad for Daisy Kenyon at the very top of this entry, which specifies when the feature starts. Again, the theatre probably opened at 1:00 and brought in the evening crowd at 7:00. That left fifteen minutes or so for pre-show material, including the color cartoon and “Global News”.

In short, some newspaper ads tell us only the theatre’s operating hours, while others specify showtimes. This sort of variation goes far back. The Olean (New York) Evening Herald advertised the Strand Theatre as “showing continuously 1 to 11 daily,” with no showtimes mentioned. On the same page we find specific starting times listed for a rival theatre’s showings of Fairbanks’Mark of Zorro (1921).

For special occasions, the scheduling could be quite exact. If you happened to be in Middletown, New York, on New Year’s Eve of 1947, you could welcome in “Kid 1948” at a gala show starting at 7:00 and ending “some time in 1948.” But not just “some time”: The State’s plan has a military precision.

Daisy Kenyon at 7:00 – 9:29 – 12:01

Comedy “Skooper Dooper” at 8:38 – 11:08

Terrytoon Cartoon “Silver Streak” at 9:12 – 11:42

Community Sing at 9:19 – 11:49

Latest Pathe News at 8:56 – 11:26

The ad goes on:

No seats reserved – No waiting in line. Come any time from 6:30 until 11:20 and see a complete show—Stay as long as you like! Come in one year—Leave the next!

The rival Goshen Theatre likewise provided a detailed schedule of its New Year’s Eve attractions, an astonishing four features plus cartoons. The show, broken into 9 “units,” started at 7:00 and ended at 1:00 in the morning, concluding with an “Exit March.” Why don’t movie theatres have exit marches any more?

Apart from ads specifying showtimes, we can glean other hints that at least some viewers preferred to know when to arrive to catch a film from the beginning. Some newspapers published lists of starting times. The New York Evening Post printed an extensive “Movie Clock” covering over eighty theatres. A Schenectady paper did the same thing under the rubric “Showing Today. What the Theatres Are Advertising.” You can find a similar feature in papers from Portland and Council Bluffs. Movie houses were often a small-town newspaper’s biggest and most reliable advertising source, so many editors were ready to oblige theatre managers.

Movie ads also sometimes included the theatre’s phone number, so people could call to check showtimes. Access to telephones was still spotty then; recall that the infamous Gallup Poll of 1948 misjudged Dewey’s chance for victory, partly by relying on phone surveys. But by 1945 there were about 16 million residential phones for a population of 140 million, so the middle-class people sought by exhibitors, then as now, might well be able to call up the movie house.

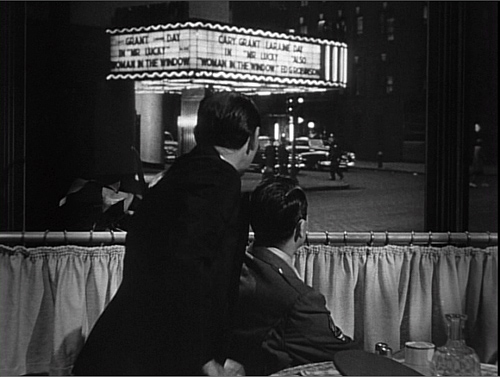

That is, in fact, what Daisy Kenyon does at one point in her movie. Having decided to go out with her girlfriend, she checks the phone number of the theatre she wants to visit and starts to call to check on showtimes. (She’s interrupted by a call from the mysterious Peter Lapham.) The scene seems to model one set of urban filmgoing habits.

Historian Douglas Gomery reminds us that there were many different sorts of theatres–first-run and subsequent-run, big downtown houses and neighborhood venues, rural ones, art houses, and so on. I’ve tried to capture some of this variety in my exploratory sample, but there are many fine-grained differences. Moreover, roadshow pictures often played to strict schedules, selling tickets for specific performances, and people adjusted their schedules to that regime for Gone with the Wind and other blockbusters. Perhaps the All About Eve fiasco came from people thinking this new film, in black-and-white and offered at regular admission prices, was not an event film like the usual roadshow attraction.

In all, it’s hard to generalize about viewing patterns. But it seems fair to say that in many circumstances viewers could, if they wanted, avoid seeing a movie’s ending before the beginning.

Which means that, then as now, we find different viewing styles. Today we have the Planners, who Tivo their cable television offerings, and the Grazers, who hop from channel to channel and watch in medias res. (We also have the Gleaners, who sample items at their leisure via the net. But there doesn’t seem to be an equivalent option in classic theatrical film viewing.) Several of Jim Emerson’s cinephile readers point out that they appreciate spoiler alerts in a web review because they want the choice between knowing and not knowing. It seems that in many circumstances movie houses offered 1940s viewers that same option.

Exhibition history is far from my specialty, so I’d welcome information from researchers who’ve studied this question more systematically. In the meantime, I’m grateful to Kristin, Ben Brewster, Lea Jacobs, Vance Kepley, Betty Kepley, John Huntington, and Virginia Wright Wexman for discussion with me. A special thanks to Douglas Gomery, who shared detailed information in emails and phone conversations.

For a comprehensive history, see Douglas Gomery, Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States (University of Wisconsin Press, 1992). See also Gregory A. Waller, Moviegoing in America: A Sourcebook in the History of Film Exhibition (Wiley-Blackwell, 2001) and Going to the Movies: Hollywood and the Social Experience of Cinema (University of Exeter Press, 2007), ed. Richard Maltby, Melvyn Stokes, and Robert C. Allen. Allen has mounted a beautiful online archive devoted to moviegoing in North Carolina.

A useful older source, though not focused on the 1940s, is Frank H. Ricketson, Jr., The Management of Motion Picture Theatres (McGraw-Hill, 1938). Ricketson advocates three hours as a maximum program time.

The motion picture theatre has a constant drop-in trade, and the patron who catches the feature after it has started does not want to sit through a seemingly endless program to see the part that he has missed. The tendency today is to present shows that are too long (p. 121).

It’s possible that as an employee of Fox Theatres, Ricketson was pushing the then-common industry view that double features were undesirable. Fewer films on the bill allowed more turnover during the day and favored the higher-profit A pictures.

Information about All About Eve‘s “scheduled performance” policy comes from the American Film Institute Catalog. See also “Business on ‘Eve’ at Roxy Jumps After Scheduled Showings Cut,” Boxoffice (28 October 1950), 50, available here. Linda Williams argues that Psycho‘s exhibition policy helped create the custom of consuming a movie straight through. See her “Discipline and Distraction: Psycho, Visual Culture, and Postmodern Cinema,” in “Culture” and the Problem of Disciplines, ed. John Carlos Rowe (Columbia University Press, 1998).

My analogy to standing on a precipice comes from Noël Carroll’s The Philosophy of Horror.

Two final points I couldn’t squeeze in elsewhere. First, to a large extent, spoilers are a function of different sorts of movie talk. In daily conversation, we’re reluctant to tell too much to friends who haven’t yet seen the film. Journalistic film reviewers seek not to reveal the ending, of course, but they’re also obliged to write about many scenes in an oblique way. (“After a string of preposterous coincidences…”) Net writers seem to model their comments on conversation and professional reviews, although some rascals delight in telling innocent readers everything that happens. We might call them spoilersports.

By contrast, academic writing assumes that the reader has seen the film, or is willing to let details be divulged for the sake of some larger point. Occasionally bloggers adhere to this standard. Readers of J. J. Murphy’s blog know that he doesn’t refrain from synposizing a plot to give depth to an analysis. I’ve done the same thing here on many occasions, but sometimes I feel the need to signal spoilers, particularly for current releases or films that depend on big twists. For some reason, I think that older films are fair game for full-blown discussion, even though many of our readers are less likely to have seen Enchantment than Source Code.

Second point, pure digression: In 1947, Richard Hull published Last First, a mystery novel dedicated “to those who habitually read the last chapter first.” The opening chapter does provide the story’s ending, but as you’d expect there’s a trick. The chapter is written so obliquely that you can’t really tell who is doing what to whom. At least I can’t.

P. S. 18 May 2012: Two more items that I’ve run across relevant to the this-is-where-we-came-in problem. First, this dialogue exchange from Ellery Queen’s serial-killer novel of 1949, Cat of Many Tails. The murder victim, one investigator says, “left for a neighborhood movie. Around nine o’clock.” The other asks, “Pretty late?” The reply: “She went just for the main feature.” This suggests that in Manhattan, it wouldn’t be impossible to know when the main feature played for the last time–either from the newspaper, from a phone call, or just from custom.

It seems that indeed late shows of the A picture were common. A 1939 Variety article, “‘Bad’ Scheduling Squawk” (27 December 1939, 5, 47) indicates that often the “No. 1 film” was put on at awkward hours, and viewers objected. “Too often, it is declared, a customer will call the theatre, only to learn the film he or she wants to see goes on at a time that interferes with dinner, or it’s on the last show, so late that getting out would be around midnight or thereabouts. Result, under theory, is that the customer doesn’t go at all.” Again, we find some evidence that the public could find out when a movie played by phoning, and that at least some patrons cared enough to see the picture through from the start. This piece from 1939 suggests that these options were available at least in some towns throughout the 1940s. Presumably, this practice was prominent in theatres not controlled by the studios, since the B picture was a flat-rate rental but the No. 1 feature was a percentage booking. The more tickets you could sell for the B, the bigger the exhibitor’s share of receipts.

P.S. 21 May 2012: The Wisconsin Project never sleeps. Alert Ph. D. researcher Andrea Comiskey sends me 1939 ads from the Olympia in Portsmouth, New Hampshire and the Fox in Billings, Montana. Both lists start times for both features, A and B, with the Fox including the start times for cartoons and newsreels too. The heading is, bluntly, “When to Come Today.” As per the above addendum, the Fox runs the A picture last, and quite late (around 10 PM).

P.P.S. 1 February 2021: Ran across this in John O’Hara’s novel Butterfield 8 (1935):

“What are we up to this afternoon?”

“Oh, whatever you like,” she said.

“I want to see ‘The Public Enemy.'”

“Oh, divine. James Cagney.”

“Oh, you like James Cagney?”

“Adore him.”

“Why?” he said.

“Oh, he’s so attractive. So tough. Why–I just thought of something.”

“What?”

“He’s–I hope you don’t mind this–but he’s a little like you.”

“Uh. Well, I’ll phone and see what time the main picture goes on.”

“Why?”

“Well, I’ve seen it and you haven’t, and I don’t want you to see the ending first.”

“Oh, I don’t mind.”

“I’ll remind you of that after you’ve seen the picture.”

Daisy Kenyon. Daisy and her friend, tracked by Peter and watched by a waiter, have apparently gone to a revival house–and one not playing pictures from Fox, the studio behind Daisy.

The Cross

The Puffy Chair (2005).

Mark: [The actors] need to improvise. They need to find the moments, and we don’t let them lean on the script too much. We want them to try to reinvent some of the dialogue and make it fresh.

Jay: We don’t do any blocking. Our whole goal is just to set up a room and basically foster an interaction that we feel is interesting and real.

Mark: And spontaneous.

Jay: And spontaneous.

Jay and Mark Duplass, talking of their new film Cyrus.

DB here:

We don’t do any blocking. Dude, we noticed. In The Puffy Chair, the Duplass brothers typically settle the actors into one spot and pan or cut between them.

Seldom do the characters move around the setting. When they do, it’s usually by means of a walk-and-talk traveling shot that transitions to the next static layout of actors.

We are talking about filmmakers who refuse the challenge of staging.

At the other extreme of budget and commercial clout, consider another film by two brothers. In The Matrix Reloaded, Neo meets the Oracle in the virtual courtyard and sits on a bench with her.

The whole scene, which runs nearly seven minutes, contains 94 remarkably static shots. After Neo settles on the bench beside her, we get simple reverse shots—lots of them, mostly one per line of dialogue. The setups are maniacally repeated. There are thirty-one iterations of the first framing below and eighteen of the second.

The only variation is a slightly tighter framing on each character, creating another brace of single setups during Neo’s acknowledgement of his dream of Trinity’s death. Each of these gets nine iterations.

Sustained two-shots would have let the actors do more with their upper bodies, but in this string of singles, faces and dialogue have to present Neo’s reactions to his new mission to save Zion. Granted, there are seven shots showing both Neo and the Oracle in the same frame, but these are very brief and seem to be there simply to provide beats and add some variety to the load of exposition the scene must carry.

Breaking the scene up so much has interesting rhythmic implications. Paradoxically, our movies are cut very fast but they feel rather slow (and run very long). When we need a cut to see a character’s reaction, a scene plays out more slowly than if the characters were held in the same frame for a significant period. Then we might see Neo’s reactions while the Oracle is speaking, rather than having to wait for them afterward.

But my main point is that the actors are planted in one spot. Like the Duplasses, the Wachowski brothers have felt no need to imagine the characters’ interaction through blocking. Indeed, when shooting a conversation, most of today’s filmmakers seem happiest if the actors stay riveted in place—standing, seated, riding in a car, typing at a computer terminal. Improvised cinema or storyboard cinema: Both camps are refusing the challenge of staging.

In some books and some web entries (most recently, here and here and here and here), I’ve tried to trace the rich tradition of ensemble staging. From almost the start of cinema, filmmakers have explored creative ways of moving actors around the set, aiming at both engaging storytelling and pictorial impact. Since the 1960s, on the whole, this tradition has been waning. Now, I fear, it has nearly disappeared.

I’m not going to reiterate those earlier arguments. Instead I want to talk about one simple staging tactic that directors almost never employ today. I offer it at no cost to young directors. Try it! You might get a taste for a range of cinematic expression that is nowadays neglected.

Cross and double cross

Assume you have two characters in a set. At a crucial moment, you invent some business that lets them exchange places, so that the one on the left winds up on the right, and vice-versa. At a minimum, this gives you visual variety; it keeps the viewer’s attention engaged by refreshing the composition. It can of course also heighten dramatic impact.

Naturally, we expect to find the Cross in the first golden age of cinematic staging, the 1910s. Here’s a case that combines the cross with depth staging, from the Doug Fairbanks picture The Matrimaniac (1916).

Marna and the Court officer have switched places in the frame. Note especially that her movement to the right, clearing our view of the officer at the door, is motivated by her hesitation at following him. Actually such moments probably don’t need much motivation; the flow of the action is so quick that no viewer will ask why she moved to the right, since our attention is on what her action reveals.

One way to motivate the Cross is to have A turn sharply away from B but keep talking. This is a bit of actor’s business that seems far more common in the classical era of moviemaking. Here is an excerpt from a single-shot scene in Budd Boetticher’s The Tall T (1957). Brennan tries to console Mrs. Mrs. Mims, who has realized that her husband betrayed her. He enters the shack and then walks past her, as if considering exactly how to calm her.

This has been the prelude to a more intense confrontation. She comes closer to the camera, and Brennan joins her, forcing her to look at him as he says they must concentrate on staying alive.

In Demy’s Lola (1961) the Cross is motivated by the urge to offer another emphatic view of the protagonist. Roland has been talking to the two mother-figures who run the café he frequents. He’s dragging himself off to work as Jeanne fetches her radio from the bar and goes into the back room. We get two Crosses.

The shot’s climax comes when Roland pauses in the foreground and says: “One day I’ll go away too.” Again, a key character is turned from the other but continues to speak.

No need to cut in to a close-up because Roland’s face is perfectly visible. Just as important, while his face shows a certain reverie, his nervousness is conveyed by the way he waggles the novel in his hand. The actor is given a chance to act, not just with line reading and facial expression but with his slumped posture and his arms—one casual, the other in anxious motion. Taken together, the body and the face present Roland’s confusion.

Crossfire

Don Siegel’s The Big Steal (1949) yields many offhand instances of the Cross, indicating how taken for granted the technique was in studio films. When the slippery Fiske invites Joan in, she comes to the left foreground and he moves to the right side of the frame to shut the door.

Approaching her by stepping into medium shot, he tries to warm her up, but she slaps him. Cut in to underscore her reaction. “What did you expect—kisses?”

In a return to the earlier setup, she turns away and executes another Cross, settling on the sofa.

Simple and concise; some would say banal. But compared to The Puffy Chair and The Matrix Reloaded, it looks brisk. The characters move easily through the frame without camera arabesques, and the medium shot is saved for the slap. The single of Joan adds another spike to the drama. Close-ups no longer rule but are used for momentary emphasis.

So the Cross can be sustained by cutting and camera movement. In The Lady Is Willing, Liza has found a baby and called a pediatrician. Director Mitchell Leisen gives us an over-the-shoulder shot of her and at the close of it she walks around Dr. McBain’s arm, with her feathery hat brushing his face.

If the shot were sustained with a pan, we’d have a Cross, but instead there’s a cut to Liza continuing the movement. McBain turns to watch her.

He starts to follow her diagonally. When she pauses to face him, the Cross is completed.

They leave the room. After a cutaway shot showing Liza’s secretary, the camera pans to follow McBain into depth washing his hands. When he comes through the door past Liza, we get another Cross.

With positions switched, the camera travels with her as she catches up with him in a medium shot. He is opening his medical bag.

This pause enables Leisen to underscore a key line of dialogue. “I detest children of all ages. I detest infants particularly.”

One more Cross and the shot is done. The camera pans again to follow McBain bending over the child, and Liza slips into the shot behind him, remonstrating with him. “A man who dislikes children simply can’t be a baby specialist.”

As so often, the Cross is used to present one character turning from another, or one trying to catch up with another who for dramatic reasons plows ahead. And the Cross favors a moderate depth, not the eye-smiting foregrounds of Welles but something less aggressive. In these ways, the simple device can participate in a broader pattern of fluid craftsmanship. The action can unfold in a clean rhythm, consistent with what Charles Barr calls “gradation of emphasis.” Story points arise smoothly out of the flow of behavior. Actors get a chance to use their whole bodies, to create character through posture or stance, or even the angle of the elbows. Imagine if Dietrich, in the left shot just above, had sauntered to McBain with her hand on her hip as she does in so many other movies; the scene would take on a different tint.

When thinking about staging, we usually invoke Renoir or Ophuls or Jancsó, directors who integrate complex choreography with complicated tracking shots. (They also use the Cross a lot.) My examples try to show that even simple camerawork can enhance the performers’ grace. Nor do they have to execute the calisthenics on display in the office scenes of His Girl Friday. The modest moves we see in The Big Steal and The Lady Is Willing are within the grasp of eager filmmakers and game actors.

Cross purposes

I don’t have a good explanation for why such simple staging tactics have gone out of fashion. It’s too easy to cite laziness or lack of imagination, though they may play a role. I wonder as well if complicated staging is much taught in film schools. More specifically, improvisational methods may actually inhibit creative blocking. An actor who’s winging it may be reluctant to shift around the set, for fear that this creates new problems for framing or lighting or the other performances. Better, the actor may think, to concentrate on line readings, expressions, and other things that she can control while staying rooted to the spot. And maybe our directors don’t want to work their actors too hard, especially when the actors are beginners or nonprofessionals, as we find in indie filmmaking. Yet some masters of supple, intricate staging, such as Hou Hsiao-hsien, employ untrained performers.

Contemporary directors may have a more principled objection to the older staging style: It’s too artificial. In real life, people mostly chat with each other when they’re sitting down, or walking, or riding in a car. Static staging, some might say, captures the passive nature of everyday interactions.

But dramatic narrative typically doesn’t consist of ordinary life. A film offers heightened, focused, pointed encounters, shot through with meaning and feeling. The actors and the filmmaker have a chance to sharpen the viewer’s perception of the situation and pass along the moment-by-moment play of thought, emotion, and action. There are both loud and quiet ways of doing this. Antonioni’s famously “dedramatized” scenes are staged as dynamically as the more florid moments of Visconti or Fellini. Emotionally subdued action can be shaped just as precisely as passionate outbursts, and it can carry its own impact.

I should make it clear that I’m not asking anybody to embrace a single style. Sometimes stand-and-deliver and intensified continuity editing work very well. Directors will always seek specific solutions to the problems of a scene. But I don’t see much variety in the solutions many people now pursue. I don’t see evidence that most young filmmakers around the world are aware that traditions furnish lots of alternatives.

In earlier periods, some directors were as editing-oriented as today’s mainstream ones, while other directors adopted more staging-driven approaches. But either sort had a broader palette than what we see today. Any accomplished director could stage a conversation in a variety of ways. Just to take Demy, some scenes in Lola are handled in full shots like the one highlighting Roland in the café. Other scenes are broken up into tight singles, and still others are treated in two-shots.

All the classical films I’ve mentioned are pluralistic in their technical choices. Today, though, we see more uniformity, or rather conformity.

Cinephile conversation on the internet is currently rippling around a controversy about “slow cinema.” Whatever that rough category covers, it surely includes those festival films that put the camera in one spot per scene and simply observe. I’d argue that many of these minimalist movies are also AWOL when it comes to staging. After watching a long-take, flatly shot film with me, a Hong Kong filmmaker friend remarked, “This sort of thing is just too easy.” One difference between a solid “slow film” and an empty one, I suspect, lies in the extent to which the filmmakers explore the resources of staging. How do we know? We have to analyze the films. (More on this matter here.) Absent that analysis, critics’ appeals to realism or meditative restfulness or “time flowing through the shot” risk becoming alibis for inert moviemaking.

Many young directors want to be innovative. They want to shake things up. This is a good impulse. The way things are going, the ambitious way forward is obvious: Go backward. Avoid stand-and-deliver. Avoid walk-and-talk. Get your actors on their feet and move them around the setting. Invent bits of business that let them crisscross the frame, laterally and in depth. Dynamize all areas of the shot. In the process you may discover new dimensions of creativity.

The Cross is only one tactic, but I think it’s useful as a way to sensitize ourselves to staging. The best way to understand staging is to watch, really watch, a lot of classic cinema from Hollywood and elsewhere. When you’re ready for the hard stuff, Mizoguchi is waiting.

I expect disagreements with my criticisms of contemporary film technique, so I hope skeptics will consider my more extensive arguments in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and The Way Hollywood Tells It.

I haven’t found references to what I call the Cross in manuals of direction. The closest technique, and the one that called my attention to the possibilities of the technique, is what Mike Crisp in his valuable book The Practical Director (first ed., 1993) calls the “rise and cross.” This refers to actors getting up from sit-down conversations in one spot and moving to another sit-down area, while switching position in the frame. I’ve expanded the idea to cover a broader variety of situations.

As far as I can tell, my term doesn’t have much in common with the stage direction “Cross,” which you’ll find in play scripts. Janie Jones provides definitions here. While staging in film is in many respects different from that in theatre, I think that moviemakers can find intriguing practical ideas in Terry John Converse, Directing for the Stage.

Alicia Van Couvering’s interview with the Duplass brothers, “Don’t you want me?”, is published in Filmmaker 18, 3 (Spring 2010; not yet available online); my quotation is from p. 43. In his essay Slow Cinema Backlash, Vadim Rizov argues that lesser attempts at “slow cinema” have led to a somewhat predictable style.

Raining in the Mountain (King Hu, 1979).

The ten best films of . . . 1918

Kristin here–

We ended 2007 with a salute to the 90th anniversary of the solidification of the classical Hollywood filmmaking system. 1917 was not only the year when all the guidelines—continuity editing, three-point lighting, and unified story structure—gelled in American cinema. It was also one of those years (like 1913, 1927, and 1939) when a burst of creativity took place internationally. For those years, it’s hard to keep one’s greats list to ten.

Enough of you enjoyed that entry that we thought we would come up with another list to end 2008. For some reason, 1918 doesn’t yield the plethora of great films that obviously should go on such a list. Maybe it’s the sheer accident of preservation. After a string of masterpieces from Douglas Fairbanks in 1917, there seems to be a dearth of his films extant from the following year. Some filmmakers, like Cecil B. De Mille, simply released fewer films in 1918. And of course, some masterpieces may still lie gathering dust on archive shelves, waiting to be discovered.

Still, great films were made that year, some familiar—some that should be better known. Some are available on DVD, and some are excellent candidates for release by some of the enterprising companies like Kino International, Image Entertainment, and Flicker Alley.

1. The list isn’t in rank order, but for me the outstanding film of 1918 is Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru, better known to most as The Outlaw and His Wife, by Victor Sjöström. This tale of an enduring love between a man  hunted by the police and a rich landowner who falls in love with him, and, as one title says, “Hearth and home and every man’s respect—she gave it all up for his sake.” The result is one of the cinema’s great romances as the pair flees to the mountains and spend the rest of their lives amidst the natural landscapes that create spectacular backdrops for the action.

hunted by the police and a rich landowner who falls in love with him, and, as one title says, “Hearth and home and every man’s respect—she gave it all up for his sake.” The result is one of the cinema’s great romances as the pair flees to the mountains and spend the rest of their lives amidst the natural landscapes that create spectacular backdrops for the action.

This year Kino also brought out a disc with the dynamite double bill of two tragedies Ingeborg Holm (1913) and Terje Vigen (1916). David and I have both written about the staging in Ingeborg Holm, and David has had much to say on tableau staging in 1910s cinema. Watch these three films, and you will understand why we consider Sjöström perhaps the great director of the decade. It’s a shame that more of his films are not available yet in the U.S. Buy copies of these, and maybe Kino will bring more of them out.

2. Another master of this era, Louis Feuillade, made a sequel to his Judex (1916): La Nouvelle Mission de Judex. David discusses both in the second chapter of his Figures Traced in Light. Although Judex is available on DVD, so far the second serial is not.

3. I suspect that Hearts of the World is one of those D. W. Griffith features that a lot of film enthusiasts have heard of but not seen. Remarkably, it’s not available on DVD. (Keep your old laserdisc if you’ve got one!) I have to admit, it’s not one of my favorite Griffiths, though it does have a charming performance by Dorothy Gish and contains scenes that were actually shot near the front lines in France.

4. Ernst Lubitsch was making the transition from shorts to features in 1917 and 1918. While Carmen is historically important for his development toward his mature style, most audiences these days would probably find Ich möchte kein Mann sein (“I don’t want to be a man”) more entertaining. It’s a comedy about an independent young lady who escapes her strict governess and guardian by going out on the town disguised as a man—in the process joining her guardian without his recognizing her (see the frame at the bottom). Its star, Ossi Oswalda, was an outgoing blonde dynamo, quite different from Pola Negri, whom Lubitsch turned to for his later historical epics.

Kino has made several of Lubitsch’s films from the late 1910s and early 1920s available. Ich möchte kein Mann sein can be bought on a single disc with Die Austerinprinzessin (“The Oyster Princess,” 1919), another Oswalda comedy. I’d recommend getting it as part of the larger “Lubitsch in Berlin” set, which also includes the hilariously imaginative Die Puppe (“The Doll,” 1919), the Expressionist satire Die Bergkatze (“The Wildcat,” with Negri in her one comic role for Lubitsch, 1921), an Arabian-nights epic Sumurun (1920), and the historical epic Anna Boleyn (1921), as well as a documentary on Lubitsch.

5. In 1918 Cecil B. De Mille made a film that would change his career’s trajectory: Old Wives for New. At the  time, this romantic drama that seemed risqué in its casual depiction of adultery, golddiggers, and especially divorce as creating a happy outcome. Up to that point De Mille had been working in a whole range of genres, creating imaginative films that helped define the classical style. The success of Old Wives for New led him to specialize in spicy romances known for their haute couture costumes. The film is available on a disc from Image that includes De Mille’s other major film of 1918, The Whispering Chorus.

time, this romantic drama that seemed risqué in its casual depiction of adultery, golddiggers, and especially divorce as creating a happy outcome. Up to that point De Mille had been working in a whole range of genres, creating imaginative films that helped define the classical style. The success of Old Wives for New led him to specialize in spicy romances known for their haute couture costumes. The film is available on a disc from Image that includes De Mille’s other major film of 1918, The Whispering Chorus.

6. Hell Bent, by John Ford, was long thought to be among his many lost westerns from the early years of his career. It was rediscovered in the Czechoslovakian archive and shown years ago in Pordenone at the Il Giornate del Cinema Muto festival. I must confess that I don’t remember it very well, apart from one spectacular tilt downwards as a stagecoach (?) races down a winding mountain road. Not as good as Straight Shooting, and Hell Bent survives in rocky shape (perhaps too much so for DVD release), but Ford films of this era are so rare that I’ve listed this one.

7. Like Lubitsch, in the late 1910s Charlie Chaplin was making a gradual transition from shorts to features. In 1916 and 1917 he released a remarkable string of Mutual two-reelers, from The Rink (December 1916) to The Adventurer (October 1917). In 1918, with A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms, he increased the films’ length to three reels, or roughly 45 minutes, and started releasing through First National. He also cut back on the number of titles released each year. Apart from a brief promotional film for war bonds, A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms were his only 1918 releases. Which is better? I suppose most people would say Shoulder Arms. To me it’s a toss-up.

8. David and I started attending Il Giornate del Cinema Muto in 1986, when the festival was launching its great series of national retrospectives. In quick succession, these retrospectives revealed three hitherto virtually unknown but major auteurs of the 1910s: the Swede, Georg af Klercker, in 1986; the Russian, Evgeni Bauer, in 1989; and the German Franz Hofer, in 1990. Bauer’s career ended with his death in 1917. Hofer remained active until the early 1930s. The Giornate’s German program contained only six of his films, however, and those from the 1913-1915 period. I suspect that means the later teens titles are lost.

In contrast, nearly all of af Klercker’s films survive, mostly in the original negatives. The prints shown at Pordenone were stunning. The director had a great eye for settings, using beaded curtains, mirrors, and other elements to considerable effect. He made three films in 1918: Fyrvaktarens dotter, Nobelpristagaren,Nattliga toner, the first two of which were shown in the 1986 retrospective.

Unfortunately since then the films have not been made widely available, either in prints or on DVD. Having not seen the two titles just mentioned since 1986, I can’t say that I remember them well enough to judge between them. So I’ll just leave all three films here, along with the advice to seize any chance you may get to see those or af Klercker’s other films.

(Given how little known af Klercker’s work is outside Sweden, I should point out a major English-language piece on the director’s style, Astrid Söderbergh Widding’s “Towards Classical Narration? Georg af Klercker in Context,” in editors John Fullerton and Jan Olsson’s Nordic Explorations: Film Before 1930 [Sydney: John Libbey, 1999].)

9. Stella Maris, directed by Marshall Neilan, was the first of five features Mary Pickford starred in in 1918. Its reputation lies mainly in the fact that Pickford played a double role, the bed-bound but lovely title character, and an ugly, slightly deformed orphan. In its outline, the story sounds abstract and overly symmetrical. Stella Maris’s relatives shut her off from all ugliness in the world, keeping her in happy innocence well into her teens. Unity, the orphan, has known nothing but deprivation. As Stella comes to glimpse the grim side of life, Unity is adopted and has glimpses of the beauties enjoyed by the rich. Both become miserable as a result.

The overall implication is pretty grim. Stella’s world is initially wonderful only because everyone lies to her. She becomes embittered when she finally discovers this. At the heart of the tale is the deception that life is beautiful. Unity, who has not been deceived, knows better from the start. Even one brief reference to the war, as a troupe of soldiers passes by the estate where Stella lives, makes it seem tragic—this in a film that came out about two months after the U.S. had entered World War I.

The balance between the two characters is made less artificial than it might sound by Pickford’s extraordinary performance—not so much as Stella, who is a rather passive version of the typical Pickford persona, but as Unity. The waif’s frequent disappointments and outright suffering create a strong effect that shadows even the quasi-happy ending. It’s a beautifully made film as well, with the use of glamorous backlight (as in the image at the top of this entry). Stella Maris is available on DVD from Image.

10. I have been hard put to find a feature to round out the list, so I’m substituting a group of shorts. They’re not masterpieces by any means, but each displays the talents of a great silent comic well on the way toward his most fruitful period.

There’s no single great film to mark Harold Lloyd’s transition, but during 1918 he was developing his “glasses” character. He had had a modest success with his “Lonesome Luke” series from 1915 to 1917, where he essentially created a variant of Chaplin. In September, 1917, Lloyd first wore his famous black, lens-less glasses in Over the Fence. His early one-reelers wearing those glasses were still sheer slapstick, with little of the characterization that he would later develop to go with his new look. Arguably it was 1919 or even 1920 before he had fully nailed that persona. Still, during 1918 one can see him groping toward the formula.

Kino’s “The Harold Lloyd Collection” volumes contain four films from that year, all co-starring Lloyd’s  regular co-stars, Snub Pollard and Bebe Daniels. The Non Stop Kid (the title on the film; filmographies mistakenly give it as The Non-Stop Kid; May 21), Two-Gun Gussie (May 19), The City Slicker (June 2, all three on volume 2), and Are Crooks Dishonest? (June 23, on volume 1). The development clearly came in fits and starts. Two-Gun Gussie and Are Crooks Dishonest? are both slapstick affairs involving tricks and mistaken identify. The Non Stop Kid, though, has Lloyd in a more familiar situation, using his wits to foil a crowd of suitors and win the heroine’s hand. The City Slicker has a similar feel to it, though unfortunately the end is missing. The Non Stop Kid also has Lloyd donning a disguise in the form of a false moustache that somewhat resembles the one he had worn as Luke. This scene has a startling effect, blending the glasses character and the Luke character.

regular co-stars, Snub Pollard and Bebe Daniels. The Non Stop Kid (the title on the film; filmographies mistakenly give it as The Non-Stop Kid; May 21), Two-Gun Gussie (May 19), The City Slicker (June 2, all three on volume 2), and Are Crooks Dishonest? (June 23, on volume 1). The development clearly came in fits and starts. Two-Gun Gussie and Are Crooks Dishonest? are both slapstick affairs involving tricks and mistaken identify. The Non Stop Kid, though, has Lloyd in a more familiar situation, using his wits to foil a crowd of suitors and win the heroine’s hand. The City Slicker has a similar feel to it, though unfortunately the end is missing. The Non Stop Kid also has Lloyd donning a disguise in the form of a false moustache that somewhat resembles the one he had worn as Luke. This scene has a startling effect, blending the glasses character and the Luke character.

1917 and 1918 formed the high point of the string of comic shorts directed by Fatty Arbuckle, in which he also co-starred with Buster Keaton and Al St. John. When Keaton went solo, he proved to be a far better director than Arbuckle. Arbuckle tended to simply face his camera perpendicularly toward the back of the set for every shot, just cutting to whatever scale of framing would best display a gag. Here it’s the perfectly timed and executed gags that dazzle, and the films are often hilarious. In 1918, the team made The Bell Boy, Moonshine, Out West, Good Night Nurse, and The Cook. The latter shows off Arbuckle and Keaton’s dexterity at juggling props and Fatty’s surprising grace, as when he improvises a Salome dance with a head of lettuce standing in for that of John the Baptist!

The 13 surviving Arbuckle-Keaton films (some with missing bits) are available on Eureka’s definitive boxed set, “Buster Keaton: The Complete Short Films.” (That’s Region 2 format only, and available from Amazon UK.) Image’s “The Best Arbuckle Keaton Collection” has 12 films, missing only the more recently rediscovered The Cook. Image brought out The Cook on a disc with Arbuckle’s A Reckless Romeo (1917, sans Keaton). Kino’s two separately available volumes of “Arbuckle & Keaton” (here and here) contain 10 shorts total, again missing The Cook.

Apart from all these films, it’s worth noting that in the world of animation, 1918 saw the release of Winsor McCay’s fourth cartoon, The Sinking of the Lusitania, and Dave Fleischer’s first, Out of the Inkwell, which launched the enduring series.

Next year, 1919. Happy 2009 to all our readers!

His majesty the American, leaping for the moon

DB here:

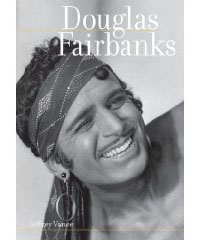

Douglas Fairbanks is remembered today as the nimble, insouciant hero of a string of swashbuckling films: The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), Robin Hood (1922), The Thief of Baghdad (1924), Don Q Son of Zorro (1925), and The Black Pirate (1926). He is the primary subject of a gorgeously illustrated, solidly researched new biography by Jeffrey Vance with Tony Maietta. Proceeding film by film, the authors interweave his life story with production data and summaries of critical reception. While tracing his career, they make an intriguing case that Fairbanks’ 1920s features more or less founded the modern film of action and adventure.

Douglas Fairbanks is remembered today as the nimble, insouciant hero of a string of swashbuckling films: The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), Robin Hood (1922), The Thief of Baghdad (1924), Don Q Son of Zorro (1925), and The Black Pirate (1926). He is the primary subject of a gorgeously illustrated, solidly researched new biography by Jeffrey Vance with Tony Maietta. Proceeding film by film, the authors interweave his life story with production data and summaries of critical reception. While tracing his career, they make an intriguing case that Fairbanks’ 1920s features more or less founded the modern film of action and adventure.

In the five years before The Mark of Zorro, Fairbanks made twenty-nine features and shorts. Vance and Maietta are enlightening on this period, but they treat it as prologue to the more spectacular work. Now, as if to counterbalance their book, comes a new Flicker Alley DVD collection, Douglas Fairbanks: A Modern Musketeer, gathering ten of the early films along with a very pretty copy of The Mark of Zorro and Fairbanks’ last modern-day movie, The Nut (1921), made because he wasn’t sure that Zorro would be a hit. (It was.) To the DVD package Vance and Maietta have contributed an informative booklet and they offer enlightening conversation in a commentary track for A Modern Musketeer (1917).

Kristin and I have long been fans of the pre-Zorro titles. Kristin wrote an appreciation of the early films for a Pordenone catalogue, and I studied Wild and Woolly (1917) as an early prototype of Hollywood narration. (1) There’s no denying that the 1920s costume pictures offer dashing spectacle and derring-do. But the 1915-1920 films are something special—lively, lilting, and unexpectedly peculiar. (2)

Kristin and I have long been fans of the pre-Zorro titles. Kristin wrote an appreciation of the early films for a Pordenone catalogue, and I studied Wild and Woolly (1917) as an early prototype of Hollywood narration. (1) There’s no denying that the 1920s costume pictures offer dashing spectacle and derring-do. But the 1915-1920 films are something special—lively, lilting, and unexpectedly peculiar. (2)

Before he became Fairbanks, he was Doug, the relentlessly cheerful American optimist. This star image was created very quickly, in films and in public events that made him seem the nicest guy in the country. His manic energy came to incarnate the new pace of American cinema, and his films helped shape the emerging precepts of Hollywood storytelling.

Doug

Consider his contemporaries. William S. Hart keeps his distance; perhaps his severe remoteness comes from secret pain. The result is a man you respect and admire but can hardly love. Mary Pickford, though, is lovable, and so is Chapin, although his cruel streak complicates things. But Doug is quintessentially likable. His early films present us with a brash youth who is all pep and pluck, bouncing with barely contained energy, unselfconscious in his engulfing enthusiasm for life. Today he could be elected President, the ultimate guy to have a beer with. (In real life Fairbanks was a teetotaler.)

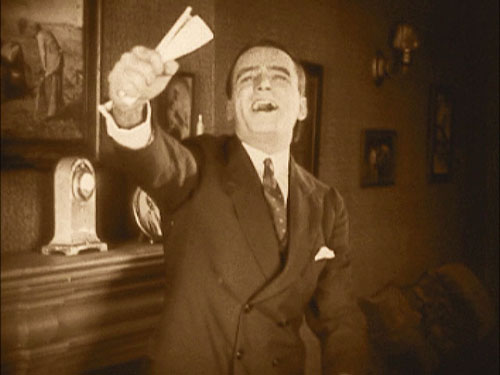

There is no guile in him, no hidden agenda. When he’s brimming with delight, as he often is, he flings his arms out wide. In another actor this would be hamminess, but for Doug it’s simply an effort to embrace the world. Any social embarrassments he commits—and they are plenty—he acknowledges with a puzzled frown before flicking on an incandescent grin. Who else makes movies with titles like The Habit of Happiness (1916) and He Comes Up Smiling (1918)?

There is no guile in him, no hidden agenda. When he’s brimming with delight, as he often is, he flings his arms out wide. In another actor this would be hamminess, but for Doug it’s simply an effort to embrace the world. Any social embarrassments he commits—and they are plenty—he acknowledges with a puzzled frown before flicking on an incandescent grin. Who else makes movies with titles like The Habit of Happiness (1916) and He Comes Up Smiling (1918)?

But how can such a genial fellow yield any drama? Give him an idée fixe, a cockeyed hobby or life philosophy into which he can pour his adrenaline. Now add a goal, something that his obsession blocks or unexpectedly helps him attain. Toss in the staples of romantic comedy: a good-humored maiden uncertain how to tame this creature of nature, a few old fogeys, some unscrupulous rivals. Hardened crooks may make an appearance as well. Be sure to include some tables, chairs, sofas, or horses for him to vault over, as well as some perches near the ceiling or on the roof; Doug feels most comfortable lounging high up. Add windows, for his inevitable defenestration. (In a poem about him, Jean Epstein wrote, “Windows are the only doors.”) There should also be chases. Other comedy stars run because they must. Doug’s joy in flat-out sprinting suggests that he welcomes the chance to flush a little hyperactivity out of his system. At the story’s climax he must save the day, taming his obsession and achieving his purpose while acceding to the claims of the practical world.

An early example is His Picture in the Papers (1916). In this satire on vegetarianism and the American lust for publicity, Doug works for his father’s health-food firm, even though he prefers thick steaks. But he’s full of ideas for promoting the product. Doug needs money to marry his equally carnivorous girlfriend, but his father will give him the dough only if Doug can pitch their line of dietary supplements. Doug vows to get his picture in every newspaper in town. While he launches a series of high-profile stunts—wrecking his car, entering a prizefight, brawling on an Atlantic City beach—his sweetheart’s father is pursued by a gang called the Weazels, who try to extort money from him.

The two plotlines converge, with Doug stopping a train wreck and winning a place on the front pages. (In a sly dig at the press, each news story contradicts the others.) The movie is a little disjointed, but several scenes are remarkable, not least a boxing match in an actual athletic club before an audience of cheering Fairbanks pals. And there is more than one funny framing, notably a nice planimetric one showing all our principals lined up and reading different newspapers celebrating Doug’s triumph.

As the title indicates, in The Matrimaniac (1916) Doug’s goal is elopement, which he pursues obsessively. He evades a rival suitor, his girlfriend’s father, a sheriff, and a posse of city officials in order to tie the knot in a gag that must have looked radically up-to-date. Reaching for the Moon gives us a more philosophical Doug, a naive disciple of self-help books that urge him to strive, to concentrate, and above all to keep his eye on the most supreme goal he can imagine. He ends up in New Jersey.

Wild and Woolly (1917) casts Doug as the son of a railroad tycoon. Although he lives in Manhattan, he dreams of being a cowboy. His bedroom boasts a teepee, and he practices his roping skills on the butler. Sent out to Bitter Creek to investigate a deal, he encounters the rugged frontier of his dreams, complete with shootouts, town dances, and hard-drinking cowpokes. But all of this is a show, staged by the locals to make him look favorably on a railroad spur. In another twist, a crooked Indian agent uses the charade to rob the bank and stir up an Indian settlement. Now Doug’s obsessions prove really useful, as his cowboy skills rescue the town.

Wild and Woolly is among the very best of the surviving early Fairbanks titles, and its adroit storytelling is still admirable today. The best-known version was a very poor print, salvaged from the Czech archives and still circulating on barely visible VHS and public-domain DVD copies. Forget those. On the Flicker Alley collection the image quality, while not perfect, allows this trim little masterpiece to be appreciated. (3)

“Always chivalrous, always misunderstood,” reads one intertitle in another gem, A Modern Musketeer. Here Doug is possessed by the spirit of D’Artagnan, simply because while he was in the womb his mother was reading The Three Musketeers. He manages to live up to his heritage as he overcomes a philandering rival and a bloodthirsty Indian. The climactic chase takes place at the Grand Canyon, affording Doug a chance to shinny up and down cliffs and do handstands along a precipice.

Doug never does things by halves. In Flirting with Fate, he is a starving artist, out of money and apparently unloved by his girl. The logical solution is to hire a killer to end his misery. Of course Doug’s fortunes instantly change, and life becomes worth living, but then he must somehow find his assassin and call off the hit.

Many of the early films show the protagonist fully formed as a cross between a cheerleader and a track star. But Fairbanks made a big success on stage playing a sissy. The task in such a plot is to turn him into a red-blooded man. His first film, The Lamb replayed this lamb-into-lion plot, which also served as the basis for Buster Keaton’s first feature, The Saphead (1920).

In the Flicker Alley collection, this strain of Doug’s work is represented by The Mollycoddle (1920). Doug is the descendant of hard-bitten westerners, but growing up in England has made him a fop. Coming to America with a batch of wealthy Yanks, he is a continual figure of fun, waving his monocle and cigarette holder. Once in Arizona, however, he’s confronted with a diamond-smuggling racket. He starts to channel his ancestors and turns into a hell-for-leather hero. He allies with a tribe of exploited Indians to capture the gang, in the process indulging in leaps, falls, canyon-scaling, and fistfights in raging rapids.

The titles often invoke craziness, vide the Matrimaniac, The Nut, and Manhattan Madness (1916). But this motif is carried to an extreme in one of the strangest pictures of the still-emerging Hollywood cinema. When the Clouds Roll By (1919) crams in enough gimmicks for three Doug stories. First, our hero is neurotically superstitious. He will climb over a building to avoid letting a black cat cross his path. He meets a girl who is as superstitious as he is, so after a session at the Ouija board, they seem a good match.

At the same time, however, a psychiatrist is making Doug the subject of a demonic experiment: Can one drive a person to madness and suicide? Through bribes and surveillance, Dr. Metz turns Doug’s life into hell—botching his romance, getting him disowned by his father, and even inducing nightmares. As if all this weren’t enough, the last reel jams in a train crash, a bursting dam, and a flood. Before this overwhelming climax, When the Clouds Roll By isn’t so much funny as eerily paranoiac. The way Dr. Metz’s Mabuse-like scheme enfolds everyone is as anxiety-provoking as anything in a film noir. This dreamlike movie ends on a surrealist note: Doug and his sweetheart get married when flood waters carry a church past them.

At the same time, however, a psychiatrist is making Doug the subject of a demonic experiment: Can one drive a person to madness and suicide? Through bribes and surveillance, Dr. Metz turns Doug’s life into hell—botching his romance, getting him disowned by his father, and even inducing nightmares. As if all this weren’t enough, the last reel jams in a train crash, a bursting dam, and a flood. Before this overwhelming climax, When the Clouds Roll By isn’t so much funny as eerily paranoiac. The way Dr. Metz’s Mabuse-like scheme enfolds everyone is as anxiety-provoking as anything in a film noir. This dreamlike movie ends on a surrealist note: Doug and his sweetheart get married when flood waters carry a church past them.

Across these films, in fact, the Fairbanks persona starts to disintegrate. Somewhat like those naïve Capra heroes of the 1930s (Mr. Deeds, Mr. Smith) who turn into melancholy victims in Meet John Doe and It’s a Wonderful Life, Doug becomes more brooding and helpless. In Reaching for the Moon, his absurd dream of glory is revealed as just that, a dream. When the Clouds Roll By saves itself from despair through splashy last-minute rescues.

Fairbanks was evidently becoming uncomfortable in cosmopolitan comedy. His taste for large-scale stunts and tests of prowess led him to the costume sagas of the 1920s. In the process, as Vance and Maietta point out, he cleared the way for Keaton and Harold Lloyd. Both comics would sometimes play obtuse idlers in the Lamb mode, and both would take thrill comedy to new heights. But avoiding Fairbanks’ ebullient optimism, Keaton brought a perplexity to every situation, along with an angular athleticism and a geometrical conception of plotting and shot composition. Lloyd frankly presented a hero lacking social intelligence, afflicted with a stammer or shyness or even cowardice, always desperate to fit in. Both men deepened the possibilities of modern-day comedy, thriving in the niche vacated by Fairbanks.

Bug and Mr. E

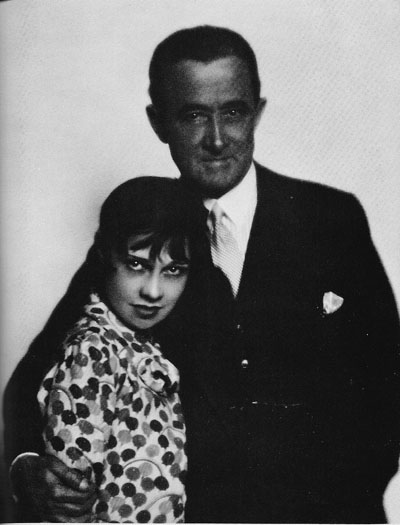

For nine of the early films, Fairbanks had the help of John Emerson and Anita Loos. All three worked on the stories, with Emerson usually directing and Loos writing the scripts and intertitles. The collaboration lasted only about two years, but it yielded some definitive moments in the creation of the Doug mystique.

Emerson found his first success acting and directing on the New York stage. Under Griffith’s supervision he started filmmaking in 1914, with an adaptation of his own successful play, The Conspiracy. I haven’t seen this or most of his other early work, but his 1915 Ibsen adaptation Ghosts, codirected with George Nichols, betrays little of the dynamism that would run through his Fairbanks projects (although The Social Secretary of 1916, without Doug, is lively enough). Emerson continued to direct films and New York stage productions until his death in 1936, at the age of fifty-eight.

Loos was a tiny prodigy. She sold her first scripts at age nineteen, with the third, The New York Hat (1913), directed by Griffith, earning her twenty-five dollars. (Her punctilious account book is reprinted in her 1974 autobiography Kiss Hollywood Goodbye.) After writing scores of shorts, she moved into features in 1916, when, she claims, Emerson discovered her script for His Picture in the Papers. Clearing the project with Griffith and casting Doug Fairbanks, the team proceeded. This, Fairbanks’ third feature, proved a great success and solidified important aspects of his star persona.

Loos married Emerson, whom she recalled as having “perfected that charisma, which even a bad actor has, of being able to charm his off-stage public.” (4) He called her Bug, she called him Mr. E., and they became a Hollywood couple. They kept themselves before the public eye with interviews and books like How to Write Photo Plays (1920) and Breaking into the Movies (1921). These are full of information about the filmmaking practices of the day.

Loos married Emerson, whom she recalled as having “perfected that charisma, which even a bad actor has, of being able to charm his off-stage public.” (4) He called her Bug, she called him Mr. E., and they became a Hollywood couple. They kept themselves before the public eye with interviews and books like How to Write Photo Plays (1920) and Breaking into the Movies (1921). These are full of information about the filmmaking practices of the day.

Why did Emerson and Loos split from Fairbanks? Loos says that that Doug had become somewhat jealous of her notoriety. (5) Further, the couple yearned to return to New York. There Loos would hobnob with the Algonquin club crowd and write Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, a successful serial, book, play, and silent film. Eventually she would write plays and return to Hollywood as an MGM screenwriter.

Although they remained married and collaborated on plays and films, the pair eventually lived apart, the better to ease Emerson’s philandering. “Mr. E.’s devotion was largely affected by the amount of money I earned,” Loos recalled. (6) By her own testimony, she earned plenty. She writes in 1921:

The highest paid workers in the movies today are the continuity writers, who put the stories into scenario form and write the “titles” or written inserts. The income of some of these writers runs into hundreds of thousands of dollars a year . . . . Scenario writing does not require great genius. (7)

Loos is largely credited with bringing the witty intertitle into its own. Expository “inserts” were often neutral descriptions of the action or pseudo-literary ruminations. Loos created intertitles that were amusing in themselves. When Jeff, the hero of Wild and Woolly, comes to Bitter Creek he’s delighted to find a rugged life matching the one he mimicked in his East Coast mansion. So naturally Loos’ title reads, “All the discomforts of home.”

She wedged in puns, satiric jabs, and asides to the audience. The vegetarianism portrayed in His Picture in the Papers makes for anemic romance. Loos’ title prepares us:

The young suitor and Christine kiss by tapping each other’s cheek with their fingertips.

Later the intertitle stresses the more robust wooing program launched by Doug.

By the time Loos and Emerson left Fairbanks, the look and feel of their contributions had been mastered by others, notably director Allan Dwan, and smart-alec intertitles continued to grace Fairbanks’ modern comedies. Throughout the 1920s, most comedies would strive, not always successfully, for the cleverness Loos brought to the task. My own favorite in her vein comes in the Lloyd vehicle For Heaven’s Sake (1926). Harold is a millionaire courting a girl working in her father’s mission house in the slums, and one of the titles refers to “The man with a mansion and the miss with a mission.” Such niceties largely vanished when movies started to talk.

Cutting edge

We can learn a lot about the history of Hollywood from these films too. In the 1910s, narrative techniques were being put in place: the goal-oriented hero, the multiple lines of action, the need to prepare what will happen later, the use of motifs as running gags. At the start of The Matrimaniac, we see Doug sneaking into a garage and letting the air out of a car’s tires. Only later, after he has eloped with the daughter of the household, do we realize that this was a way to keep her father from pursuing them. In the course of the same film, the elopement is aided by passersby, and Doug keeps scribbling IOUs to pay them. At the end, the parson who has helped the couple the most is rewarded by the biggest payoff, with Doug shoveling bills at him.

The same years saw the consolidation of the “American style” of staging, shooting, and cutting scenes. (For more on this trend, see our earlier entries here and here.) Fairbanks’ films from 1916 to 1920 display a growing mastery of continuity techniques; the style coalesces under our eyes.

The system depended on breaking up master shots into many closer views. This practice was less common among European directors of the time, who might supply inserts of printed matter like letters but did not usually dissect the scene into shots of different scales. In His Picture in the Papers, for instance, we get a master shot (nearer than it would be in a European picture) of Melville paying court to Christine, followed immediately by closer views that show their expressions.

This is a minimal case. Not only are the shots all taken from the same side of the line of action (the famous 180-system) but they are taken from approximately the same angle. Filmmakers sometimes varied the angle more, usually to indicate a character’s point of view but sometimes to bring out different aspects of the action. (See here for examples from William S. Hart.)

Very quickly directors realized that you didn’t need a master shot if you planned your shots carefully. In Flirting with Fate, the artist Augy is chatting with Gladys, while her mother and her rich suitor watch from another part of the room. No long shot presents both pairs.

The mother summons Gladys, and when she and Augy rise, director Christy Cabanne cuts to another shot of them, moving into the frame.

This is a very rare option in most national cinemas of the period, which would simply frame the couple in a way that allowed them to rise into the top of the same shot. Now Gladys hurries out, crossing the frame line. This exit matches her entrance on frame left, meeting her mother.

Such a scene is obvious by today’s standards, but a revelation at the time—a way of lending even static dialogue scenes a throbbing rhythm that absorbed viewers. Around the world, notably in the Soviet Union, young directors saw this as the cutting-edge approach to visual storytelling. The new style was as probably as exciting to them as the powers of the Internet are in our time.

Because of analytical editing, the cutting pace of American films of the late 1910s is remarkable, and the Fairbanks films, with their strenuous tempo, are fair examples; the average shot length in these films ranges between 4 seconds and 6.6 seconds. With so many shots, production procedures emerged to keep track of them. To a certain extent shots were written into the scenarios Loos refers to, but directors also broke the action up spontaneously during filming. The cameraman, and later a “script girl,” would log the shots during shooting so that they could be assembled correctly in the editing phase.

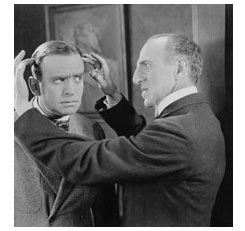

Directors were still refining the system, though, as we can see from an awkward passage of shot/ reverse shot in A Modern Musketeer.

The eyelines are a bit out of whack, but odder still are the identical backgrounds of the two shots. Evidently director Allan Dwan made these shots quickly and closer to the canyon rim, in the expectation that nobody would notice the disparity.

Point-of-view shots were easier to manage, and they could intensify the drama. Later in A Modern Musketeer, the rapacious Chin-de-dah tells the white tourists he’s getting married. To whom? asks Elsie. Instead of answering, “You,” he holds up his knife.

Sometimes you suspect that filmmakers were multiplying shots just for the fun of it. The early Fairbanks films are vigorous to the point of choppiness; action scenes spray out a hail of images, some offering merely glimpses of what’s happening. Wild and Woolly is especially frantic, with the final sequences of kidnapping, gunplay, and a ride to the rescue breathless in their pace. In the course of it, Emerson realizes that fast action needs some overlapping cuts to assure clarity. Doug bursts through a locked door in one shot, and from another angle, we see the door start to open again.

Only a few frames are repeated, but the movement gains a percussive force. Doubtless the Russians studied cuts like this; Eisenstein made the overlapping cut part of his signature style.

By contrast, The Mark of Zorro and its successors have calmer pacing. Doug’s acting got more restrained too, with his bounciness largely confined to the action scenes. Already in 1920, high-end pictures were finding a more academic look, a polished and measured style. Dialogue titles became more numerous, and big sets and other production values were highlighted.

I’ve been able to sample only a few points of interest in the early Fairbanks output. I haven’t talked about Fairbanks’ foray into Sennett-style farce, the cocaine-fueled Mystery of the Leaping Fish (1916), or the bold experimentation of the cinematography in the dream sequence of When the Clouds Roll By. My point is just to note that these films radiate exuberance—not only in their hero but in their very texture. Scene by scene, shot by shot, Doug’s energy is caught by an efficient, pulsating style that was an engaging variant of what would soon become the lingua franca of cinematic storytelling.