Archive for the 'Actors' Category

Good Actors spell Good Acting, 2: Oscar bait

Kristin here–

David and I seem to be swimming against the stream of end-of-year blog entries. No ten-best lists, no predictions about Oscar nominations.

Instead, I’ll develop on the theme I introduced in my entry concerning the over-emphasis on star turns in reviews of films that contain an obviously outstanding performance. It’s interesting that quotes from such reviews are now routinely used in the “For Your Consideration” ads in show-business trade journals like Variety and The Hollywood Reporter when a studio is pushing a performance for award nominations.

There are a lot of good performances in any given year. We’ve all seen reviews that call a performance “Oscar-worthy” without the actor ending up getting nominated or even mentioned by pundits at year’s end predicting those nominations. Some types of performances just seem more like Oscar bait than others. What makes them that way?

Some of the reasons are apparent to almost anyone who pays any attention during the awards season. Notoriously, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences members prefer to honor dramatic roles rather than comic or musical ones. In 1985, a good deal of outrage was expressed—and rightly so–over the fact that Steve Martin was not nominated for his hilarious turn in All of Me. Conversely, the nomination of Johnny Depp for a comic role in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl created a stir, though few probably thought that he would actually win. (Remember, just being nominated is an honor, as nominees—and who would know better?—often point out.)

So, actors tend to be nominated for serious roles. Not just any kind of serious roles, though. History teaches us that playing a real person gives one’s chances for a “nod” (as nominations are for some reason now called). From Paul Muni in The Story of Louis Pasteur to George C. Scott in Patton to Ben Kingsley in Gandhi to Phillip Seymour Hoffman in Capote, it’s a familiar pattern. In the television age, when famous people’s appearances and behaviors are often familiar to the public, performances can become in part a matter of impersonation, and a skill at mimicry becomes a strong signal of “good acting.” Undoubtedly a performance like Helen Mirren’s as Elizabeth II in The Queen adds subtleties that go beyond the imitation of appearance and speech patterns and other obvious characteristics, but it’s the impersonation that gets talked about more.

Even when we’re not familiar with the person a character represents, for some reason it helps to have “based on a true story” attached to a title. Publicity often stresses that the actor met and spent time with the real person in order to craft an authentic performance.

Obviously making oneself less attractive to play a role gets Brownie points in a big way: Robert DeNiro gaining 60 pounds to play boxer Jake La Motta in Raging Bull, Charlize Theron sacrificing glamor in Monster, Nicole Kidman sporting an unflattering fake nose as Virginia Woolf in The Hours.

Characters with disabilities can definitely put an actor into the Oscar-bait realm: Cliff Robertson in Charly, John Mills in Ryan’s Daughter, Daniel Day Lewis in My Left Foot, or Jack Nicholson in One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Presumably the implication of playing a real person or gaining weight for a role or simulating a disability all imply work, harder work than “just” playing a healthy, good-looking fictional person.

There are other indicators for nomination likelihood.

It helps to be old. Think Helen Hayes in Airport or Art Carney in Harry and Tonto. Their best performances? This year Peter O’Toole may finally get a non-honorary acting statuette.

It helps to be English and to have done Shakespeare.

For that matter, it helps to speak English. We’ll see if Penélope Cruz ends up being one of the very few to succeed without doing so. She did get nominated for a Golden Globe for Volver, but foreign-language films are definitely an afterthought when it comes to Academy Awards.

It helps to be Meryl Streep, whose performances don’t even have to fit any of these tendencies.

Oddly enough, most of these generalizations don’t seem to apply as much to the supporting-actor categories. Presumably “supporting” implies a less bravura turn that doesn’t compete with the stars.

Of course there are all sorts of reasons why actors get Oscars. A lot of people were surprised in 1997 when Juliette Binoche (The English Patient) beat out Lauren Bacall (The Mirror Has Two Faces) as Best Supporting Actress. It helps to recall that three years earlier, through a technicality, Binoche had been judged ineligible to be nominated for Best Actress in Three Colors: Blue. The injustice of that clearly rankled Academy members (the majority of whom are actors), and the first time they had a chance to make it up to Binoche, they did. Both Jimmy Stewart and Denzel Washington supposedly won their Best Actor awards because voters felt they had deserved them for previous roles.

On Thursday the Golden Globes nominations were announced. Reporting on the Globes tends to center around their predictive powers for the later Academy Awards. (See “And … They’re Off!” in the new Entertainment Weekly.) The Globes are just as interesting, though, for the fact that they divide the main film-acting awards into two categories: “Drama” and “Musical or Comedy.” (Two parallel best-picture awards are given in these categories as well, but for some reason the supporting-actor awards aren’t divided by genre.) So Sacha Baron Cohen and Johnny Depp can get nominated for comedies and not have to compete against Will Smith and Forest Whitaker in dramas.

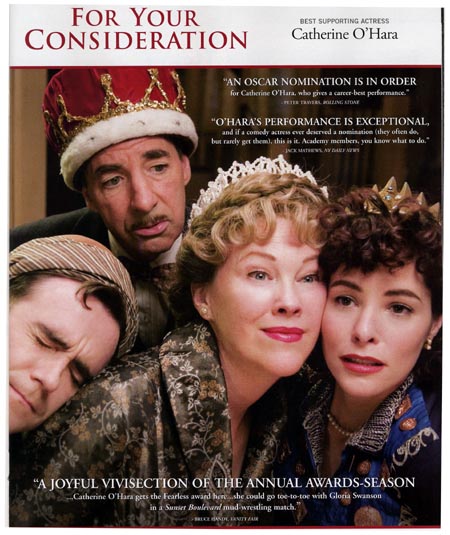

If you like endless speculation on nominees-to-be, check out the December 2006 Hollywood Reporter issue “The Actor.” In it Stephen Galloway talks about actors playing real people: “Whether a story surrounding a character is biographical or fictionalized, actors are determined to find the truth behind their real-life role models” (“As a Matter of Fact”). Part of the reason that the trade press devotes so much space to awards speculation is because these special issues sell lots of “For Your Consideration” ads. This year my favorite one touts Catherine O’Hara as best supporting actress. They don’t even have to tell us the title.

Good Actors spell Good Acting

Kristin here–

I suppose all movie-lovers have favorite quotations that become part of their everyday conversation. Norman Bates’s “One by one you drop the formalities” fits a surprising number of situations. The film-studies professors here in Madison often communicate with each other using lines from Howard Hawks films, especially Rio Bravo. “Let’s take a turn around the town,” “We’ll remember you said that,” and, of course, “It’s nice to see a smart kid for a change.” Any time David or I get a particularly small royalty check, we echo Hildie Johnson’s sour “Buy yourself an annuity.”

One of our favorite everyday-life quotations comes not from a movie but from the endlessly hilarious SCTV series. It’s a skit in which Steve Roman (played by John Candy) promotes his new TV show, Juan Cortez, Courtroom Judge. He explains part of its appeal: “It’s got good actors, and that spells good acting.” (Fifth season, episode 110, for you SCTV buffs.)

Almost invariably we use this line when we come across one of those films that receive highly positive reviews largely because of one great performance. You know the kind: Charlize Theron in Monster, Halle Berry in Monster’s Ball, Hillary Swank in Boys Don’t Cry, and more recently Forest Whitaker in The Last King of Scotland and Helen Mirren in The Queen.

Usually I avoid such films, because the reviews tend to plant the idea that they are primarily actors’ vehicles. I enjoy good acting as much as the next person, but I want the rest of the film to be interesting as well.

Are there any film classics that are truly great solely for the acting? It’s hard to think of any. Maybe The Gold Rush, which is stylistically fairly pedestrian but which is redeemed by Chaplin’s inspired performance. Maybe Duck Soup, also quite undistinguished for much of anything other than the Marx Brothers cutting loose without being saddled with the sort of plots involving young, singing lovers that MGM would soon foist upon them. Maybe a few others. Usually, though, we tend not to think of a performance, however dazzling, as adding up to a great film.

Still, when I think of some of the finest performances ever put on film, I think of Falconetti in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc by Carl Dreyer. There her luminous portrayal of determination and religious devotion is embedded in an equally extraordinary film, with its minimalist sets by Herman Warm, its insistently tight framings on faces, and its vertiginous camera movements. Similarly, Nicolai Cherkasov as Ivan the Terrible in Eisenstein’s film poses against the shapes of the settings, moves to the music of Prokofiev, and casts great shadows on the walls. Buster Keaton, though not as popular in his day as Chaplin, had an instinctive feel for both the flat space of the screen and the depth of the represented image, and his films are exciting in themselves and not simply as backgrounds to his clowning.

We’re now well into the time of year when the studios bring out the films they hope will garner Oscar nominations and even wins. Journalists covering film, reviewers and feature writers alike, can get some copy out of speculating about the Oscars. That speculation seems to start earlier and earlier each year, like Christmas shopping. Given that the public is a lot more interested in acting than cinematography or screenwriting, perhaps it’s not surprising that reviewers focus so much on star turns. But in doing so, do they slight other aspects of those films? Do they unfairly scare off those of us who are wary of Oscar bait?

I decided to do my part for the good of the blog and see The Queen. I’m not a huge fan of Stephen Frears, but My Beautiful Launderette is a good film, with an early sympathetic, non-sensationalized view of homosexuality in London. Mary Reilly is not exactly a masterpiece, but it’s worth watching and has been underrated. Its failure may have been due in part to the fact that most reviewers focused in on whether Julia Roberts could handle a dramatic role in a thriller and then found her wanting.

Anyway, The Queen turned out to be an entertaining, well-made film. Yes, Helen Mirren is remarkable as Queen Elizabeth II, and she may well win an Oscar for her performance. Yet equally interesting is the fact that Frears almost entirely avoids the “intensified continuity” style that David has analysed in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

The film is basically pretty simple, moving back and forth between the royal family and the newly elected Tony Blair surrounded by his wife and staff. The royals notoriously reacted to the death of ex-Princess Diana with stony silence despite the huge outpouring of public grief. It’s clear from the indifference and even hostility toward Diana that the members of family’s older generations voice in private, they do not feel a comparable grief. But Blair strives to maneuver the Queen into going public and expressing a sense of loss.

Frears set out to contrast the two worlds stylistically. The scenes with the royals are shot in a classical, non-intensified style. Distant shots to establish space, two shots for face-to-face conversations, over-the-shoulder shot/reverse shots as the dialogue unfolds. The framing seldom goes in for the tight close-up but stays in medium shot or medium close-up. The cutting is slow relative to the current norm, as befits both the subject and the style. One reason people are so impressed with Mirren’s performance may be that it is not made up of a bunch of different shots stitched together. She has shots that allow her to develop a reaction or attitude slowly.

And best of all, the camera doesn’t glide toward or around the characters. It stays put unless it needs to perform one of its traditional roles: reframing to keep characters balanced, and following the characters as they move from one room to another or walk along a country track. The lighting is suitably subdued and directional, another reversion to a more classical age.

A great deal is currently being made of Steven Soderbergh’s reversion to 1940s Hollywood style in The Good German. Frears isn’t quite as systematic, perhaps, but the royal-family scenes in The Queen look very 1950s to me.

In contrast, the Tony Blair scenes were shot with a handheld camera, to convey the bustle of his staff and the more casual situation. Even so, the camera movement is not obtrusive, and Frears still doesn’t constantly cut in for the tight close-up. Here, too, he keeps his camera back a bit, framing groups as they talk. The lighting tends to be brighter and more diffuse. The contrast works well, and yet Frears never pushes it in our faces and asks us to be impressed.

The narrative seems a little thin, mostly because, unlike most classical films, The Queen has only one plot line. There’s no subsidiary crisis, no romance, no other conflict. It’s just the royals versus the liberal prime minister’s team until one side cracks. Even the potential conflict that could have easily arisen from Blair’s wife’s anti-royalty position never goes anywhere. She’s mainly there as a sounding-board for him. And if the plot is thin, it is also refreshingly elegant in its simplicity.

One remarkable aspect of the plot is that none of the characters is treated as a villain. Blair’s position is held up as the wise one, yet the film goes to great lengths to suggest that the Queen and her family have reasons for behaving the way they do. Not excuses, but reasons. Fittingly, the film concludes with the Queen and her new prime minister walking out into the palace gardens for a stroll and a chat.

At the end, I didn’t feel that I had sat through a great performance. I had seen a good, entertaining, somewhat unusual, and skillfully made film that had a great performance in it. Indeed, it has a second from Michael Sheen as Blair, and the supporting players are fine as well.

But good directors spell good directing, and good cinematographers spell … You get the idea. Variety’s reviewers, it must be said, seem to have a mandate to mention style, since ever review comments at least briefly on the film’s techniques. But most critics give you no sense of the film as a whole—its narrative construction (apart from a plot synopsis) or its stylistic texture. It would be nice to see more rounded reviews.