Archive for the 'Animation' Category

The magic number 30, give or take 4

David here–

When I was teaching, students often came to my office hours with variants of this question. “I want to direct Hollywood movies. When should I start trying to get into the industry?”

My answer usually ran this way:

Your prospects are almost nil. It’s tremendously unlikely that you will become a professional director. You may wind up in some other branch of the industry, though. In any case, start now. Aim for summer internships while you’re in school, and try to get a job in LA immediately after graduation—preferably through a friend, a relative, a relative of a friend, or a friend of a relative.

My answer still seems reasonable, but recently I’ve begun to wonder if it holds up across history. Suppose we refocus our goggles on the macro scale. At what ages do most Hollywood directors make their first feature? If we can come up with a solid answer, it would be one instance in which studying film history can have very practical consequences.

No country for old men

In any field, most people would expect to have their careers moving along by the time they hit their early thirties. But aspiring filmmakers may think that there’s a long period of preparation–working in a mailroom, sweating over screenplays–before they finally get to direct. Directing films is a top-of-the-heap role. Who would trust a young first-timer with a multimillion-dollar investment and authority over far more experienced performers and technicians?

Nearly everybody, actually.

Executives tend to be oldish and not fully aware of what the target movie audience likes. A few years ago a friend of mine, consulting for the studios, went to a meeting of suits and was told that all the new digital sampling and mixing software was purely an effort to steal music. He replied that there were legitimate creative uses of that technology. “For example?” one exec asked. My friend said, “Well, there’s Moby.” Nobody at the table knew who Moby was.

So hiring young people in touch with their peers’ tastes makes sense. Indeed, many of today’s top filmmakers started making features quite young. I haven’t made an exhaustive survey, but picking directors more or less at random yields some pretty interesting results.

Note: It’s hard to know how long a movie took to make, so I’ll use the release date as my benchmark. With the exceptions noted at the end, I haven’t checked people’s birthdays against day and month release dates. As a result, the ages of directors that I’ll be giving fall within a year of the releases. That works well enough to establish an approximate age range for a general tendency. And since it takes at least a year to get a project finished and released, we have to remember that most of these people started work on their first feature quite a bit earlier than is indicated by the age I give.

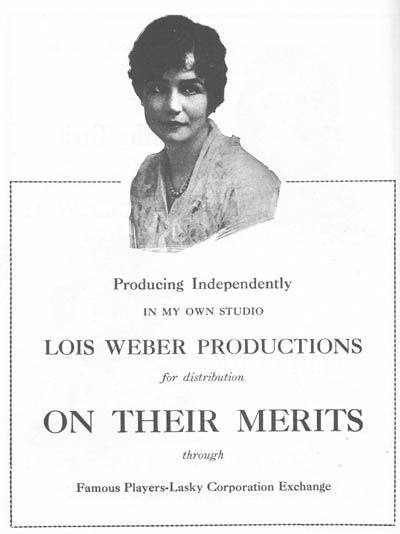

Start with directors who broke through in the 1990s and 2000s. Many were about 30 when their first features came out: Keenen Ivory Wyans (above; I’m Gonna Get You Sucka), Michael Bay (Bad Boys), David Fincher (Alien 3), and Spike Jonze (Being John Malkovich). A tad older at their debuts were Alex Proyas at 31 (The Crow), Cameron Crowe at 32 (Say Anything), James Mangold at 32 (Heavy), Karyn Kusuma at 32 (Girlfight), McG at 32 (Charlie’s Angels), David Koepp at 33 (The Trigger Effect), Allison Anders at 33 (Border Radio), and Mark Neveldine at 33 (Crank).

Actually these are the older entrants. A great many current directors completed their first feature in their twenties. Quentin Tarantino, Reginald Hudlin, Roger Avary, and Joe Carnahan debuted at 29, Sofia Coppola and Brett Ratner at 28, Peter Jackson and F. Gary Gray at 26.

Go a little further past 33 and you’ll find a few big names like Alexander Payne (35), Nicole Holofcenter (36), Simon West (36), and Ang Lee (38). Almost no contemporary directors broke into the game past 40. The most striking case I found is Mimi Leder, who signed The Peacemaker when she was 45.

On the whole, the directors who start old have found fame and power playing other roles. When you’re David Mamet, you can tackle your first feature at 40. (He’s my age; don’t think this doesn’t make me depressed.) If you’re a producer like Bob Shaye or Jon Avnet, you can start directing in your fifties. Actors, especially stars, get a pass at any age. Mel Gibson made his first feature at 37, Steve Buscemi at 39, Barbra Streisand at 41, Anthony Hopkins at 59.

Putting aside such heavyweights, the lesson seems to be this. In today’s Hollywood, a novice director is likely to start making features between ages 26 and 34. It’s also very likely that he or she will have already done professional directing in commercials, music videos, or episodic TV, as many of my samples did.

But what about the Movie Brats?

Is today’s youth boom a new development? The Baby Boomers will yelp, “No! Everybody knows that we invented the director-prodigy.” Look:

*Dementia 13: Francis Ford Coppola, 24. If you don’t want to count that, You’re a Big Boy Now was released when Coppola was 27.

*Who’s That Knocking at My Door?: Martin Scorsese, 25.

*Dark Star: John Carpenter (above), 26.

*THX 1138: George Lucas, 27.

*Night of the Living Dead: George Romero, 28.

*The Sugarland Express: Steven Spielberg, 28. If you count the TV feature Duel, subtract 2 years.

*Targets: Peter Bogdanovich, 29.

*Dillinger: John Milius, 29.

*Blue Collar: Paul Schrader, 32.

*Good Times (with Sonny and Cher): William Friedkin, 32.

*Easy Rider: Dennis Hopper, 33.

True, the 70s also revved up veterans like Altman and Ashby, but it was the new generation, we’re always told, who made the difference. Hollywood was run by old men who had brought the studio system to the brink of ruin. The twentysomethings smashed the barricades and made a place for young filmmakers.

It might have seemed that way at the time, but the belief was probably due to a quirk of history. The 1960s and early 1970s were in one respect a unique period in the history of American cinema. During those years, the studios had the widest range of age and experience ever assembled. For the first time in history, it looked like a retirement home.

Look at it this way. In the 1960s, films were being made by directors who had started in the 1950s (e.g., Arthur Penn, Sidney Lumet), as you’d expect. But at the same time there were films by directors who had started in the 1940s: Fred Zinneman, Sam Fuller, Robert Aldrich, Anthony Mann, Nicholas Ray, Vincente Minnelli, Robert Rossen, Robert Wise, Mark Robson, and many others. Furthermore, some of the biggest names of the 1960s were directors who had started in the 1930s, like George Cukor, Carol Reed, George Stevens, Otto Preminger, and Joseph Mankiewicz. More remarkably, the 1960s saw the release of films by masters who had begun in the 1920s, notably Hitchcock, Hawks, Capra, and Wyler.

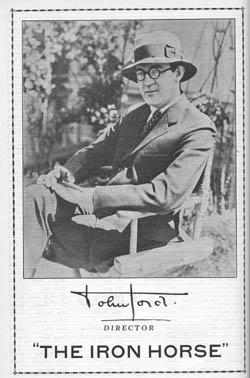

And believe it or not, several directors who had begun in the 1910s were still active nearly fifty years later. John Ford is the most obvious case, but Chaplin, Alan Dwan, Henry King, Fritz Lang, George Marshall, and Raoul Walsh signed films in the 1960s. When Sidney Lumet celebrates a half-century of directing with the upcoming release of Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, he will be considered a rare bird in today’s cinema; but in a broader historical context he doesn’t stand alone.

Interestingly, the arrival of the Movie Brats and the blockbuster brought nearly all the veterans’ careers to a halt. No matter what decade an old-timer started, by the mid-1970s he was most likely dead, retired, or making flops. Perhaps the Movie Brats’ sense of Hollywood as a haunted house was created in part by the felt presence of six decades of history.

The studio years

But what about those codgers? At what age did they get started? A look at the evidence suggests that the rise of the twentysomething Movie Brats has plenty of precedents.

The Hollywood studios ran a sort of apprentice system. In the 1920s and 1930s, short comedies and dramas were the era’s equivalent of music videos and commercials—ephemeral material that allowed youngsters to learn their craft. For example, George Stevens started as a cameraman, and at age 26 graduated to directing short comedies. Three years later he made his first feature (The Cohens and Kellys in Trouble, 1933).

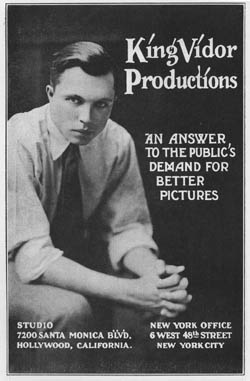

Stevens wasn’t atypical. In the 1920s and 1930s, major directors seem to have started as young as they do now. King Vidor began in features at 25, Rouben Mamoulian at 26. Mervyn LeRoy’s first feature was released when he was 27, the same age that Keaton, Capra, and Sam Taylor entered the field. Byron Haskin and W. S. Van Dyke made their debuts at 28. Hawks started at 30, as did Victor Fleming, Lewis Milestone, and Joseph H. Lewis. Clarence Brown signed his first solo feature at 31, the same age as Jules Dassin and George Cukor at their debuts.

Even more remarkable is what went on during the 1910s. As Hollywood was becoming a film capital, it became a playground for twentysomethings. Lois Weber, Alan Dwan (who may have directed 400 movies), James Cruze, Reginald Barker, George Marshall, George Fitzmaurice, Raoul Walsh, and many others directed their first features before they were thirty. (At this point, a feature film could be around an hour. Kristin explains here.) Cecil B. DeMille was on the senior side, having directed The Squaw Man (1914) at age 33. Griffith was then even older of course, but having started in 1908, somewhat earlier than this generation, his authority waned as theirs rose. And he had started directing within my golden zone, at age 33.

Why so many youngsters? In the 1910s, the industry was growing rapidly and it needed a lot of labor. Few people went to college, so teenagers could take low-level jobs at the studios straight out of high school, or even without a secondary education. Moreover, Kristin reminds me that at this time life expectancy was much lower than today; in 1915 a white male on average would live only 53 years. Beginners hurried to get started, and bosses probably found comparatively few oldsters around.

At the other extreme, the World War II years seem to have been a tough time to break in. Anthony Mann, Nicholas Ray, Don Siegel, Richard Brooks, Robert Aldrich, Robert Rossen, and other gifted directors had to wait until their mid- to late thirties before taking the director’s chair in the second half of the 1940s. The 1950s somewhat put the premium on youth again with fresh blood, especially from the East Coast. The most famous instances are Stanley Kubrick (Hollywood feature debut at 28), John Frankenheimer (debut at 30), and John Cassavetes (Hollywood debut at 32).

In short, Hollywood has always favored fresh-faced novices. It’s not surprising. Young people will work exceptionally hard for little pay. They have reserves of energy to cope with a milieu dominated by deadlines, delays, long hours, and rough justice. They are more or less idealistic, which allows them to be exploited but which also infuses the creative process with some imagination and daring. The executives need wisdom, but the talent needs, as they say, a vision.

Some last questions

Of course in every era a few older hands start directing features comparatively late. Lloyd Bacon, auteur of the masterpiece Footlight Parade, didn’t make a feature (Broken Hearts of Hollywood, 1926) until he was thirty-seven, after dozens of shorts. Daniel Petrie was forty when his 1960 feature The Bramble Bush was released, and Julie Dash was forty when Daughters of the Dust came out. But you have to look hard to find careers starting this late. Most of the evidence I’ve seen indicates that first features skew young.

First question, then: Is the tendency to seize talent young unique to Hollywood, or is it a characteristic of other popular film industries? My hunch is that it has been a worldwide phenomenon. Eisenstein, who was 27 when he made Potemkin, was treated the oldest of his cohort of Soviet directors; at the other end of that scale were Gregori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg, who collaborated on their first film when they were 19! In Japan, Ozu, Mizoguchi, and Kurosawa started directing in their twenties. Michael Curtiz was 30 when he made his first feature, which happened to be Hungary’s first as well. The very name of the French New Wave was borrowed from a sociologist’s catchphrase for postwar twentysomethings. Today, in Europe or Asia, most beginning directors are in their mid-to-late twenties or early thirties. I suspect that everywhere the film industry gobbles up youth, both in front of and behind the camera.

Second, a question for further research. Hollywood hires a lot of first-timers, but how many of them build long-lasting careers? It’s sometimes said that it’s easier to get a first feature than a second.

Third, who’s the youngest director to make a Hollywood feature? The most famous candidate for the Early Admissions program is Orson Welles, who was 25 when Citizen Kane premiered. But on this score at least his old rival William Wyler had him beat. Wyler was 24 when he released his first feature. The fact that his mother was a cousin of Carl Laemmle, boss of Universal, doubtless helped him start near the top.

So is Wyler, at 24, the winner? No. John Ford, Ron Howard, and Harmony Korine were 23 when their first features opened. But wait: Leo McCarey was only 22 when his first feature (Society Secrets) was released in 1921. M. Knight Shyamalan’s first first feature, Praying with Anger, achieved a limited release in 1993, when he was 22.

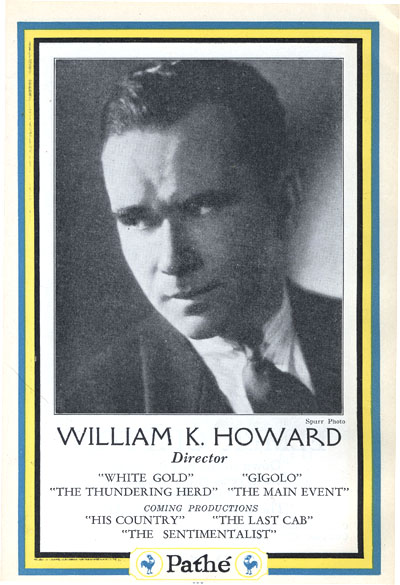

Yet I think that William K. Howard has the edge. Born on 16 June 1899, he signed two features in late 1921, when he was 22, putting him abreast of McCarey and Shyamalan. But Howard also co-directed a feature that was released on 22 May 1921—about three weeks before his twenty-second birthday. Brett and Sofia and PJ, you are so over the hill.

(Once we move out of the US, the clear winner would seem to be Hana Makhmalbaf. When she was ten, she served as AD for her sister Samira on The Apple, and she signed a documentary feature when she was fifteen. “I used to get excited over the words sound, camera, action. There was a strange power in these three words. That’s why I quit elementary school after second grade at age eight.”)

Finally, how does a little knowledge of film history help us steer hopefuls on the road to Hollywood? It gives us a sharper sense of timing and opportunity. My best revised answer would be this.

Start as young as you can, in any capacity. For directing music videos and commercials, the window opens around age 23. For features, the best you can hope for is to start in your late twenties. But the window closes too. If you haven’t directed a feature-length Hollywood picture by the time you’re 35, you probably never will.

Unless your last name is Bruckheimer, Bullock, Kidman, Cruise, or Bale.

PS 16 Sept 2007: Some corrections and updates: I’m not surprised that my more or less random sampling missed some things. So I’m happy to say that we have new contenders in the youth category.

Charles Coleman, Film Program Director at Facets in Chicago, pointed out that Matty Rich was only 19 when Straight Out of Brooklyn was released in 1991. So my candidate, William K. Howard, is second-best at best.

As for Hana Makhmalbaf, she’s been beaten too. Alert reader Ben Dooley wrote to tell me of Kishan Shrikanth, who was evidently ten years old at the release of his feature, Care of Footpath, a Kannada film featuring several Indian stars. Kishan, a movie actor from the age of four, has been dubbed the world’s youngest feature film director by the Guinness Book of World Records. You can read about him here, and this is an interview.

As for Hana Makhmalbaf, she’s been beaten too. Alert reader Ben Dooley wrote to tell me of Kishan Shrikanth, who was evidently ten years old at the release of his feature, Care of Footpath, a Kannada film featuring several Indian stars. Kishan, a movie actor from the age of four, has been dubbed the world’s youngest feature film director by the Guinness Book of World Records. You can read about him here, and this is an interview.

From Australia, critic Adrian Martin writes to point out that Alex Proyas made features before The Crow. “A clear case of Hollywood/ Americanist bias!! (Just kidding.) Proyas had an extensive career in Australia before the USA, and that includes his first, intriguing feature, Spirits of the Air, Gremlins of the Clouds, in 1989. Which puts him around 27 at the time!”

Finally (but what is final in a discussion like this?) over at Mark Mayerson’s informative animation blog, there’s a discussion about animation directors, who tend to be quite a bit older when they sign their first full-length effort. Mark’s reflections and the comments point up some differences between career opportunities in live-action and animated features.

PPS 27 December 2007: Malcolm Mays, currently 17 years old, is shooting a feature under studio auspices. Read the inspiring story here.

Rat rapture

Recently we went to see Ratatouille and both loved it. We thought it was the best Hollywood movie we’ve seen this summer.

KT: Last October, in the infancy of this blog, I posted an entry on Cars. There I said, “For me, part of the fun of watching a Pixar film is to try and figure out what technical challenge the filmmakers have set themselves this time. Every film pushes the limits of computer animation in one major area, so that the studio has been perpetually on the cutting edge.” For Cars it was the dazzling displays of light and reflections in the shiny surfaces of the characters.

Figuring out the main self-imposed challenge in a new Pixar film is like a game, and I avoid reading any statements about the films by their makers ahead of time.

At first glance Ratatouille might seem to be “about” fur. True, there are lots of rats with impressively rendered fur—but fur was the big challenge way back in Monsters, Inc. Surely Pixar wasn’t repeating itself. To be sure, Monsters, Inc. contained only one major furry character, Sulley, and his fur was the long wispy type that some stuffed animals have. Difficult to render, no doubt, but different from the rats’ fur, which is dense, short, and has to ripple with the movements of the animals.

Not only that, but in Ratatouille, we see furry rats in all sorts of situations: just running round, crawling out of water and various other liquids, and in one virtuoso throwaway shot, emerging all fluffed up from a dishwasher. It’s all very impressive, but I didn’t think that was the main technical feat that the filmmakers were aiming at.

I quickly became aware that there was something different about the settings. Pixar films always have eye-catching settings: the beautiful and convincing underwater seascapes of Finding Nemo, the huge vistas of the factory in Monsters, Inc., the stylized domestic settings in the The Incredibles.

The Incredibles, the first film that Brad Bird directed for Pixar, was deliberately cartoony-looking, evoking the streamlined Populuxe look of 1950s cartoons. Ratatouille, his second effort, takes a very different approach. Here the settings are far more realistic and three-dimensional, approaching photo-realism in some of the Parisian street scenes. Often our vantage-point moves rapidly through these settings, twisting, turning, and plunging from high angle to low angle framings in a second. In the scene where the protagonist Remy is swept away from his family through the sewers until he emerges in Paris, the twists and turns of the pipes sweep by. Likewise, the camera explores the crevices of the restaurant’s crowded pantry.

The settings have a tangible and immediate presence beyond what we have seen in previous Pixar films, partly because so many objects in the surroundings are pulled into the action. Ingredients sit in bowls and jars that take up considerable portions of the kitchen set, and the rat dashes among them, sniffing to find the ones he needs for a new concoction. The lessons learned in Cars return here to make the shiny copper cooking utensils reflect their surroundings. The brick arch and floor tiles of the restaurant kitchen were individually tweaked, so that they don’t have the uniformity that CGI tends to give repetitive patterns. Dense combinations of bricks, tiles, wood panels, carpets, patterned wallpaper, glass, and Venetian blinds make every shot too busy for the eye to fully take in.

A delightful demonstration of all these features and more is given in the “Ratatouille QuickTime Virtual Tour.” 360-degree spherical space allows you to look up at the ceiling and down at the floor as well as scan the walls. (The download time is reasonably quick; you need to move your cursor into the window that opens and use it to scroll in any direction and at variable speeds. Use the shift key to zoom in and the control key to zoom out.)

DB: Two things, one general and one specific to Ratatouille:

(1) The idea of explaining artists’ works in terms of problems and solutions is common in art history and musicology, but not so common in film studies. It can be fruitful to consider that sometimes filmmakers face common problems and that they compete to solve them, or to find different problems they can solve.

I sometimes try to imagine what animators for other Hollywood studios thought when they walked out of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Did the talents at Warners, Fleischer et al. just throw up their hands in despair? Disney must have been the Pixar of its day, challenging its rivals with a dazzling series of achievements along many dimensions. Disney had solved so many problems—of rendering color and depth, of catching detail and voluminous movement, of blending pathos with comedy—that the others could hardly compete in the same race. So it seems that they carved out other niches. Fleischer, though trying its hand at feature cartoons as well, concentrated on the familiar and presold comic-strip world of Popeye. Warners avoided child-oriented sentimentality and offered more insolent and whacked-out entertainment, personified in Bugs and Daffy. In today’s CGI realm, Pixar seems to set the pace, staking its claim before anybody else has realized the territory has opened up–though Aardman consistently offers something different.

(2) Along with the problems that you’ve mentioned, I was struck by what we might call a general task facing all animators: the need to display a sophisticated cinematic intelligence that fit contemporary tastes in live-action movies. So the pacing has to be fast (here, an average shot length of about 3.5 seconds), but it isn’t frantic. Today’s movies are overstuffed with details, so this is too; but here many stand out sharply. Central are all the minutiae of food and its preparation, which you mention below. Our friend Leslie Midkiff Debauche reports that her son, a chef, noticed the burn mark on Colette’s right forearm—a combat wound of the professional cook. Instead of the heavy satire and flatulence of the Shrek cycle, Pixar always gives us something that would engage us even if it weren’t animated.

Every director, I think, should study this film for lessons in making movement expressive. The velocity of our rats’ scampering depends on the surface they cross, and the differences in acceleration and braking are vivid. The vertigo-inducing river turbulence that carries Remy away from his clan displays the old Disney genius in rendering the behavior of water. There’s a caricatural difference in body language among all the characters, from the cadaverous Ego to the heaving movements of pudgy Emile and the spasmodic twirling of Linguini when Remy is at the controls. Shot scale is always well-judged. When there’s a moment of uncertainty about whether the kitchen team will support Linguini, the pause is accentuated by the fierce Horst taking a step forward toward the boy, in big close-up. Will this be the signal for the others to join him? The close-up conceals the key piece of information: Horst has stripped off his apron, and only when he lifts it into the frame do we realize that he’s walking out. Perhaps the visual expressiveness of silent filmmaking survives best today in animation.

KT: A secondary but still important challenge seemed to be the effort to find ways of rendering the textures of surfaces that are difficult to capture in animation. Most obviously the food—slices of carrots and tomatoes, stalks of celery—must look realistic and attractive if we are to believe that the dishes Remy devises are truly as scrumptious as the characters find them. (The film wisely sticks to soups, desserts, and, yes, ratatouille, sidestepping the problematic notion of an animal cooking other animals.)

Once you decide what you think the Pixar crew was working on extra hard in their newest film, it’s usually easy to find supporting evidence in interviews with the top people involved. For some reason Bird was reluctant to talk much about the big technical challenges for Ratatouille, but he gave a good summary in the interview on Collider.com:

I think our goal is to get the impression of something rather than perfect photographic reality. It’s to get the feeling of something so I think that our challenge was the computer basically wants to do things that are clean and perfect and don’t have any history to them. If you want to do something that’s different than that you have to put that information in there and the computer kind of fights you. It really doesn’t want to do that and Paris is a very rich city that has a lot of history to it and it’s lived in. Everything’s beautiful but it’s lived in. It has history to it, so it has imperfections and it’s part of why it’s beautiful is you can feel the history in every little nook and cranny. For us every single bit of that has to be put in there. We can’t go somewhere and film something. If there’s a crack in there, we have to design the crack and if you noticed the tiles on the floor of the restaurant, they’re not perfectly flat, they’re like slightly angled differently, and they catch light differently. Somebody has to sit there and angle them all separately so we had to focus on that a lot.

DB: This relates back to the idea that an animated film has to offer its own equivalent of what live-action has led viewers to expect. Since at least Alien and Blade Runner, we’ve come to equate realism with a worn-out world. No more spanking-clean spaceships, but rather creaky Gothic ones; no more shiny futures, only dilapidated ones. Bird acknowledges that once his team opts for more detailed settings, they have to look lived-in, rather than the rather generic ones we find in Toy Story and even The Incredibles. But then the food contrasts with this air of casual imperfection; it looks pristine.

KT: Speaking of food, in another interview, Bird expands on the difficulties of rendering it:

There was quite a bit of effort expended to make the food look delicious. Because if one of the things your movie is about is gourmet food, then you can’t have it not look delicious. And computers aren’t really very interested in making things look delicious. They’re interested in things looking clean and things looking geometrically precise, and usually hard not squishy – not tactile. Computers are great for perfection. They’re not great at organic things. We had to work really hard to get the food to look like you could taste it and smell it and enjoy it.

The interviews I’ve read don’t mention it, but the film also takes a small but impressive step toward solving the ever-difficult problem of rendering human skin. Most of the characters are given the usual smooth skin that we have come to expect in computer-animated films.

DB: Agreed! One of the things that put me off CGI animation years ago was the overpolished look of CGI surfaces. Volume without texture always looked plastic to me. But in Ratatouille, the Pixar team has made great progress in dirtying up the surfaces. That kitchen is full of spills and stains, but the faces are still pretty balloon-like, except for that villainous chef Skinner. He’s the most cartoony character, I suppose, and the range of expressions he passes through just in delivering a single line had me in stitches. The Termite Terrace legacy lives on in him.

KT: Yes, Skinner must have inspired the filmmakers. His face gets very sophisticated treatment. In most character animation, eyes and eyebrows are the main means of creating expressions in the upper half of the face. Several times, however, Skinner comes into extreme close-up, so that his expressions of rage and shock are complete with elaborate forehead wrinkles. There’s even a patch of pores on his nose. That degree of detail is used sparingly in this film, but perhaps we see a sign of things to come as the Pixar animators set up new hurdles to jump.

PS 25 August: For an interesting, more thematically oriented discussion of Ratatouille, see Michael J. Anderson and Lisa K. Broad’s entry on the Tativille blog.

PPS 31 August: Bill Desowitz has a lively and informative feature on the film, including behind-the-scenes interview material, at Animation World.

Len Lye, Renaissance Kiwi

Kristin here–

David and I have many pleasant memories from our May visit to New Zealand, where as Hood Fellows we were resident at Auckland University for a month. Among these memories is meeting Roger and Shirley Horrocks. Roger has been a major figure in the development of film studies and culture in New Zealand. He founded the Department of Film, Television and Media Studies at Auckland University and was its head until his retirement in 2004. He co-founded the Auckland International Film Festival and has written on television and film in New Zealand.

Shirley is a producer and director of documentary films, many of them about Kiwi art and culture, made primarily for TVNZ and NZ On Air. In 1984 she founded her own production company, Point of View Films.

Retrieving Len Lye

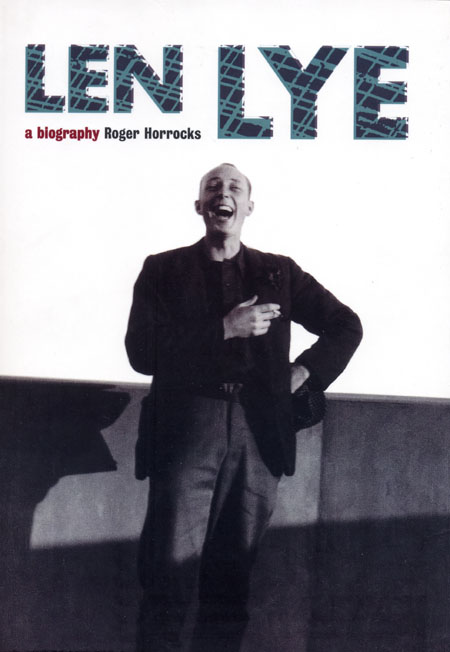

Among the Horrocks’ accomplishments has been to aid in the preservation of the work of filmmaker/ sculptor/ painter/ poet/ theorist Len Lye (1901-1980) and to disseminate information about this undeservedly overlooked figure. Roger generously gave us a copy of his impressive book, Len Lye: A Biography, and Shirley presented us with a DVD of her documentary on Lye, Flip & Two Twisters, named for one of the artist’s sculptures.

I remember seeing a few Len Lye films long ago and thinking they were delightful and innovative. In working on our textbooks, I had the privilege of sitting in one of the British Film Institute’s refrigerated viewing rooms and seeing a gorgeous nitrate copy of his 1936 film Rainbow Dance. Color frames from it appear in Film Art (8th edition, p. 164) and Film History (2nd edition, p. 321). I had also seen Lye’s strange and evocative first film, Tusalava (1929), an animated film with abstract shapes much influenced by Maori and Australian Aboriginal art (illustrated on p. 176 of Film History).

Lye was born and grew up in New Zealand, lived for stretches in Samoa and Sydney, moved to London as a young man, and moved permanently to New York in 1944. He was extraordinarily attuned to sensory perception and rhythm and was drawn to the indigenous art of the southwest Pacific area. From an early age he studied modern art and especially abstraction.

Lye belonged to a generation of innovative animators who began working in the 1920s and 1930s: Oskar Fischinger in Germany and later the U.S., and Alexandre Alexeïeff and Claire Parker in France and later Canada. Although their styles differed considerably, all sought to find alternatives to Hollywood cel animation and to explore the relationship between music and cinema.

Roger and Shirley’s gifts inspired me to renew my acquaintance with Lye’s work and take a closer look at his career. “I’ll just order a DVD of Lye’s films,” I thought to myself. Back in the late 1980s Pioneer had issued a marvelous though brief series called “Visual Pioneers.” David and I had bought “The World of Oskar Fischinger” and “The World of Alexandre Alexeïeff.” I figured that these had probably been re-issued on DVD, along with the rest of this short-lived series. It turns out, no. Lucky we held onto those laserdiscs!

Unfortunately, there was never a “Visual Pioneers” disc devoted to Lye.

The age of DVDs has not served these filmmakers well, either. One has to be doggedly determined in finding and acquiring their work. The bountiful “Unseen Cinema” set from Image contains Oskar Fischinger’s An Optical Poem (1938), an abstract short film made for MGM (!) after the filmmaker moved from Germany to the U.S. It’s on the disc titled “Viva la Dance: The Beginnings of Ciné-Dance.” Although the set claims to deal with the American avant-garde up to 1941, Alexeïeff and Parker’s 1934 masterpiece Une nuit sur le Mont Chauve (Night on Bald Mountain) is included. I suppose the logic there is that Parker was an American, though she and Alexeïeff (born in Russia) made the film in Paris and worked thereafter in Europe and Canada. (A few other émigré directors’ European works are in the set, though I can’t see why Anémic cinéma by Marcel Duchamp [aka Rrose Sélavy] should be there.)

There is a French region 2 DVD of the pair’s work available. I found it for sale online at fnac and Cinedoc. A DVD of ten Fischinger films is available from the Center for Visual Music’s shop; it actually sells the disc through Amazon, which might make it relatively easy for some to acquire.

The Center’s shop carries a variety of experimental cinema, and there I found a collection of Lye’s films—on VHS. “Rhythms” contains twelve of Lye’s major works, including A Colour Box (1935) and Rainbow Dance. It was brought out by Re: Voir, a major distributor of avant-garde cinema. One can buy it from that company, though in the U.S. the Center is a convenient source. My copy from the latter came quite quickly.

The cassette does not include Tusalava. The only place that seems to be available is on YouTube, and I hesitate to recommend it, given the fuzziness of the image. (Poor copies of some other Lye films are there as well, but since the tape contains far better versions there is no good reason to link to them.) Tusalava survives in beautiful condition, and I hope it eventually could be added to an expanded Lye collection on DVD.

Don’t be misled by the collection “The Experimental Avant-garde Series Number 19–The Serious, the Silly, and the Absurd.” There the short Lambeth Walk Nazi Style is wrongly attributed to Lye–a fairly common mistake. Lye’s short, Swinging the Lambeth Walk (1939), is an abstract film using the same pop song as a soundtrack; it’s on the “Rhythms” tape.

The Filmmaker

Perhaps one reason why Lye’s films command less attention today than they should is simply because they are so short. All twelve films on the “Rhythms” tape add up to a mere 47 minutes, and even the seven-minute Tusalava would fail to bring the total to one hour.

This paucity of footage results in part from the painstaking labor involved in making them. Some of Lye’s films depended on elaborate painting and scratching directly on 35mm film stock. This kind of animation was Lye’s innovation and not, as is widely assumed, that of Norman McLaren. A Colour Box looks remarkably like a McLaren film. The resemblance is not coincidental. One of the few periods during which Lye had institutional support was when he worked for the GPO Film Unit in London. McLaren was freshly out of art school and working at the same unit. He freely acknowledges his amazement at seeing and hearing A Colour Box and its influence on him: “Apart from the sheer exhilaration of the film, which intrigued me was that it was a kinetic abstraction of the spirit of the music, and that it was painted directly onto the film. On both these counts it was for me like a dream come true.” (pages 144-45 of Len Lye: A Biography.)

An equally revolutionary technique Lye used was no less time-consuming. The new color film stocks of the 1930s fascinated him, especially the three-strip processes. These recorded each of the three primary colors on a separate strip of black-and-white film, with the color of the final film being achieved by adding color dyes to the matrices and combining them. Technicolor is the most famous of these systems, though Lye drew upon European processes, including Gasparcolor. Lye seems to have been alone in his realization that one could use the three-strip technique on film shot originally in black-and-white.

Rainbow Dance was made by shooting, in black-and-white, a human figure leaping, playing tennis, and executing other actions against a white screen and then using the result as a silhouette filled with vivid, saturated colors. Abstract and semi-abstract shapes surrounding the figure, constantly moving and changing, create a dazzling effect. The film ends abruptly with the message, “The Post Office Savings Bank puts a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.” As advertisements, some of Lye’s films of the 1930s played in theaters, though viewers often perceived them as experimental shorts.

Another reason for the lack of attention paid to Lye is that he was always very much an eccentric loner, working on the periphery of Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, and kinetic art. Works by him were included in exhibitions devoted to these trends, but Lye always refused the prominence that allegiance with fashionable movements might have given him. He was also highly impractical about money and not adept at explaining his projects to potential grant-bestowing foundations.

The Legacy

Roger Horrocks met Lye late in the artist’s life and worked as his assistant in his final months. Roger and Shirley were involved in setting up the Len Lye Foudation, housed at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth, New Zealand. (Its website is the best online source of information on Lye.) The foundation’s collection include extensive unpublished writings by Lye, to which Roger had complete access. He also interviewed a wide range of people who had known Lye in various capacities. The result is not only thorough, but it also gives a lively sense of a profoundly eccentric artist.

As part of Lye’s fascination with the senses, he deliberately cultivated a sort of stream-of-consciousness language, both for speech and writing. The result often suggests someone communicating in poetry rather than prose, and the quotations are not always easy to understand. One note scribbled after Lye had seen a film reads, “The knobbly cast of the star Elliott Gould, bemused, his mouth full of marbles, finally flapping his foot-flippers enrout insouciantly to some horizon or other” (p. 294). Roger, however, has waded through a large, difficult set of notes and journals. As he puts it, “It took my years to find my way round this chaotic collection of fragments and drafts, but ultimately it proved a goldmine.” One early reader of the biography remarked that “the book felt at times more like an autobiography than a biography” (p. 3). This is an astute observation, for Roger has woven many quotations into his own prose and thus given a structure to the chaos. By the end one feels that one understands not just the facts of Lye’s life but also his personality.

(Unfortunately the biography, published by Auckland University Press in 2001, is already out of print. With luck there’s a copy in your local library.)

The Sculptor

For film fans and scholars with at least a passing knowledge of Lye’s shorts, the real news here will be his versatility as an artist. Before he started making films, he was already an accomplished painter. Because painting was a relatively inexpensive activity, Lye often did not promote his own work and simply gave the paintings to friends. He sought buyers and patrons for his kinetic sculpture, though, because he needed funding to build these ambitious projects.

A few museums, like the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney, own Lye pieces, but on the whole his kinetic sculptures, many of which are large and difficult to maintain in working order, are not widely or continuously displayed. Indeed, much of Lye’s later life was devoted to designing huge pieces, only some of which have been realized even now. The Len Lye Foundation is committed to realizing posthumously the plans he left behind, though no doubt some of his more grandiose schemes will remain too impractical to render.

Shirley’s documentary Flip and Two Twisters (1995) helps fill in that side of the artist’s career for those who cannot travel to New Plymouth. Although she sketches Lye’s career and shows clips from some of the films, the real revelation is footage of Lye at work on some of the main pieces, like “Blade” (1954) and “Flip and Two Twisters” (1965). The dates, by the way, are a little misleading, as Lye continued to modify his sculptures after their initial versions were finished—usually making them larger.

“Flip and Two Twisters” is a casual name for a formidable piece, though Lye eventually took to calling it “Trilogy.” The sculpture consists of a large looped ribbon of flexible steel suspended from the ceiling, flanked by two vertical strips of similar steel. Once set in motion, the thrashing and twisting movements of these three elements gradually become quite loud and violent. Onlookers declare that it is frightening to be in the same room with the sculpture, as even just watching it on video makes plausible.

This documentary would be a terrific teaching supplement for a course on avant-garde cinema. Copies are available direct from Point of View Films.

Shirley gave us three of her other documentaries. Kiwiana (1996), as its name suggests, explores some of the icons of New Zealand’s popular culture. Kiwis were beginning to appreciate these neglected everyday objects, which were becoming collectibles in the 1990s: the buzzy-bee, the gumboot, and, yes, the kiwi fruit. Peter Jackson even makes a brief appearance as a talking head. Marti: The passionate eye (2004) chronicles the extraordinary life of Marti Friedlander, who was raised in a Jewish orphanage during the 1930s and 1940s in London. She was trained as a photography laboratory technician but also became a photographer. Emigrating to New Zealand, she worked on a series of Maori portraits and documented such moments of political ferment as the Women’s Movement. Finally, The New Oceania (2005) is a portrait of the Samoan-born writer Albert Wendt and his fostering of a new Pacific culture based on local traditions but embracing modernism. All of these films are available from Point of View.

We are grateful to Roger and Shirley for being among the many who made us feel so welcome in Auckland. I’m particularly grateful for being led to revisit and explore a director who deserves to be far better known.

Frodo Franchise pre-orders and other updates and tidbits

Kristin here–

The Frodo Franchise

The Frodo Franchise, my book on the Lord of the Rings film phenomenon, is now available for pre-order from Amazon or directly from the University of California Press. It should be in bookstores in August. The cover illustration above is by the wonderful caricaturist Victor Juhasz. Check out another example of his work here; I especially like the image of Jack Nicholson.

(In New Zealand, The Frodo Franchise will be published by Penguin New Zealand, also in August. I’ll add a link to their website when pre-orders become available.)

I’ll be writing more about the book and the Lord of the Rings film between now and August, including, I hope, reporting from Wellington during David’s and my visit to New Zealand in May.

The Hobbit: Faint signs of movement

The April issue of Wired (I can’t find this on their website as of now) has a brief interview with Bob Shaye (p. 88), whose second feature film as a director, The Last Mimzy, was released on March 23. Naturally the subject of the Hobbit film gets mentioned.

On October 2, in the infancy of this blog, I discussed Peter Jackson’s other projects and whether they allowed him enough leeway to take on directing The Hobbit. I suggested that he had built considerable flexibility into his apparently crowded schedule. At that point it looked as though he might well get the offer.

Then, on January 13 I reported on Shaye’s recent declaration that because Jackson was suing New Line concerning money possibly owed him from Fellowship of the Ring and its related products, the director would not be making The Hobbit for New Line (and MGM, which is co-producing the film).

Since the flutter of anger expressed over that decision, there has been virtually no news on the subject. Now, asked by Wired about his January statement, Shaye replied, “You know, we’re being sued right now, so I can’t comment on ongoing litigation. But I said some things publicly, and I’m sorry that I’ve lost a colleague and a friend.”

Wired then asked, “Is The Hobbit still a viable project?” Shaye responded, “I can only say we’re going to do the best we can with it. I respect the fans a lot.”

Given that a large majority of the fans consider Jackson’s direction key to the film being the best New Line could do, perhaps we’re getting a hint that Shaye is relenting.

Matt Zoller Seitz and friends in Newsweek!

Matt’s site The House Next Door sends us business every now and then, and it was a treat to see it mentioned in “Blog Watch” in the April 9 issue of Newsweek (also online): “‘The Sopranos’ returns to HBO on April 8, and mob fans can’t wait to get deep inside the remaining episodes. For insightful commentary, check out mattzollerseitz.blogspot.com.”

A variety of commentators contributed to the “Sopranos Week” daily postings: April 2, April 3, April 4, April 5, April 6, April 7, and April 8.

Congratulations, Matt and company!

David’s film-viewing activities do not go unnoticed

Lester Hunt, who teaches philosophy here at the University of Wisconsin, has been blogging about students who don’t take notes in class. He considers, not unreasonably, that they should take notes. Not everyone agrees with him, however.

Lester defends his position staunchly in a new post, “Why you should take notes,” citing David’s note-taking and shot-counting during movies as evidence to bolster his case. As the one who often sits beside David during his very active viewings, I can testify that Lester’s description is quite accurate.

Ebertfest coming up

Jim Emerson’s Scanners blog provides information about the upcoming Roger Ebert’s Overlooked Film Festival (next year to be officially renamed what many of us call it anyway, “Ebertfest”), April 25-28. As Jim mentions, David and I are among the guests, and you can read the opening of my program notes for this year’s silent-film-with-live-musical-accompaniment presentation, Raoul Walsh’s Sadie Thompson. Along with others, we’ll be pitching in to try and fill in for Roger as he continues to recover from his health problem of last summer.

Fortunately Roger will be able to attend. As he writes in his recent description of his progress, “I think of the festival as the first step on my return to action.” The first of many such steps, I hope. We all look forward to 2008, when he will move once more to center stage as the heart and soul of Ebertfest.

Aardman’s new home

Finally, I have groused about how DreamWorks failed to exploit the potential of British animation company Aardman’s product. (See here and here.) Distributing films like Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-rabbit and Flushed Away, Dreamworks showed little inclination to try and turn Aardman into a brand comparable to Pixar.

Now, after the January split between DreamWorks and Aardman, Variety announces that the latter has signed a three-year, first-look arrangement with Sony Pictures Entertainment. The deal sounds promising, with Aardman expanding its Bristol facilities and stepping up the rate of production. The plan is to release a film every 18 months.

[Added April 11:

The print version of the Variety article (April 9-15 issue) is distinctly longer than the online one linked above. Author Adam Dawtrey’s description of DreamWorks tends to confirm my belief that the company handled its Aardman deal badly: “If you knew nothing about British toon studio Aardman except what DreamWorks saw fit to tell Wall Street every quarter, you might wonder why Sony was so eager to pick up where Jeffrey Katzenburg left off … Yet the multi-Oscar-winning claymation specialist had no shortage of suitors before settling on a new three-year deal last week with Sony Pictures Entertainment.”

Dawtrey points out that Chicken Run grossed $225 million worldwide, the Wallace & Gromit feature took $192 million, “and even the maligned ‘Flushed Away’ managed $176 million. The fact that Aardman’s pics … do the majority of their business outside the U.S. clearly bothers Sony much less than it did DreamWorks.”

The first two films cost less than $50 million apiece to make, while Flushed Away cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $140 million. Dawtrey adds, “The fact that Aardman execs don’t even know the precise cost of ‘Flushed Away’ betrays just how much control they ceded to DreamWorks by moving production to Los Angeles. It was a doomed attempt to find a transatlantic compromise that would salvage the relationship, but the result left both sides frustrated.”]

DreamWorks Animation decided to “concentrate on just two major releases a year.” That means just blockbusters, with no need for the more eccentric Englishness of Aardman.

Sony, on the other hand, wants to expand its animation and family-oriented product. The CEO and chairman of SPE, Michael Lynton is quoted as saying, “Aardman Features is enormously popular around the world. We believe that their strength is their unique storytelling humor, sensibility and style and we plan to bring their distinctive animated voice to theaters for a long time to come.”

Of course, intentions are always good at the beginning. Whether Sony can let Aardman be Aardman and help the company’s films achieve the success they deserve remains to be seen. I certainly hope so.

Plus it’s good to hear that one of the four features Aardman has in development is another Wallace and Grommit project. Break out the Wensleydale!