Archive for the 'Animation' Category

Oscars by the numbers

Director Chris Butler: “Well, I’m flabbergasted!” with producer Arianne Sutner.

Kristin here:

The Oscars are looming large, with the presentation ceremony coming up February 9. But did they ever really go away? As I’ve pointed out before, Oscar prediction has become a year-round obsession for amateurs and profession for pundits. I expect on February 10 there will be journalists who start speculating about the 2020 Oscar-worthy films. The BAFTAs (to be given out a week before the Oscars, on February 7) and Golden Globes have also become more popular, though to some extent as bellwethers of possible Oscar winners. The PGA, DGA, SAG, and even obscure critics groups’ awards have come onto people’s radar as predictors.

How many people who follow the Oscar and other awards races do so because they expect the results to reveal to them what the truly best films of the year were? How many dutifully add the winners and nominees to their streaming lists if they haven’t already seen them? Probably quite a few, but there’s also a considerable amount of skepticism about the quality of the award-winners. In recent years there has arise the “will win/should win” genre of Oscar prediction columns in the entertainment press. It’s an acknowledgement that the truly best films, directors, performers, and so on don’t always win. In fact, sometimes it seems as if they seldom do, given the absurd win of Green Book over Roma and BlacKkKlansman. This year it looks as if we are facing another good-not-great film, 2017, winning over a strong lineup including Once upon a Time in … Hollywood, Parasite, and Little Women.

Still, even with a cynical view of the Oscars and other awards, it’s fun to follow the prognostications. It’s fun to have the chance to see or re-see the most-nominated films on the big screen when they’re brought back to theaters in the weeks before the Oscar ceremony. It’s fun to see excellence rewarded in the cases where the best film/person/team actually does win. It was great to witness Laika finally get rewarded (and flabbergasted, above) with a Golden Globe for Missing Link as best animated feature. True, Missing Link isn’t the best film Laika has made, but maybe this was a consolation prize for the studio having missed out on awards for the wonderful Kubo and the Two Strings and other earlier films.

It’s fun to attend Oscar parties and fill out one’s ballot in competition with one’s friends and colleagues. On one such occasion it was great to see Mark Rylance win best supporting actor for Bridge of Spies, partly because he deserved it and partly because I was the only one in our Oscar pool who voted for him. (After all, I knew that for years he had been winning Tonys and Oliviers right and left and is not a nominee you want to be up against.) Sylvester Stallone was the odds-on favorite to win, and I think everyone else in the room voted for him.

Oscarmetrics

Pundits have all sorts of methods for coming up with predictions about the Oscars. There’s the “He is very popular in Hollywood” angle. There’s the “It’s her turn after all those nominations” claim. There are the tallies of other Oscar nominations a given title has and in which categories. And there is the perpetually optimistic “They deserve it” plea.

Pundits have all sorts of methods for coming up with predictions about the Oscars. There’s the “He is very popular in Hollywood” angle. There’s the “It’s her turn after all those nominations” claim. There are the tallies of other Oscar nominations a given title has and in which categories. And there is the perpetually optimistic “They deserve it” plea.

For those interested in seeing someone dive deep into the records and come up with solid mathematical ways of predicting winners in every category of Oscars, Ben Zauzmer has published Oscarmetrics. Having studied applied math at Harvard, he decided to combine that with one of his passions, movies. Building up a huge database of facts from the obvious online sources–Wikipedia, IMDb, Rotten Tomatoes, the Academy’s own website, and so on–he could then crunch numbers in all sorts of categories (e.g., for supporting actresses, he checks how far down their names were in the credits).

An early test of the viability of the method came in the 2011 Oscar race, while Zauzmer was still in school. That year Viola Davis (The Help) was up for best actress against Meryl Streep (The Iron Lady). Davis was taken to be the front-runner, but Zauzmer’s math gave Streep a slight edge. Her win reassured Zauzmer that there was something to his approach. His day job is currently doing sports analytics for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Those like me who are rather intimidated by math need not fear that Oscarmetrics is a book of jargon-laden prose and incomprehensible charts. It’s aimed at a general public. There are numerous anecdotes of Oscar lore. Zauzmer starts with Juliet Binoche’s (The English Patient) 1996 surprise win over Lauren Bacall (The Mirror Has Two Faces) in the supporting actress category. Bacall was universally favored to win, but going back over the evidence using his method, Zauzmer discovered that even beforehand there were clear indications that Binoche might well win.

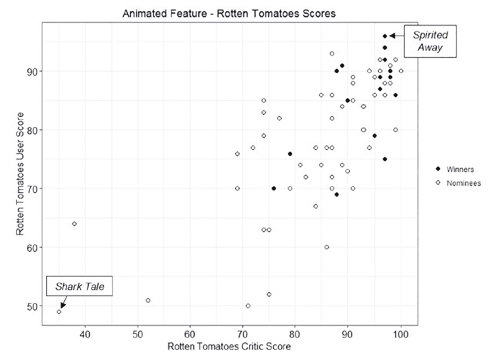

Zauzmer asks a different interesting question in each chapter and answers it with a variety of types of evidence. The questions are not all of the “why did this person unexpectedly win” variety. For the chapter on the best-animated-feature category, the question is “Do the Oscars have a Pixar bias?” It’s a logical thing to wonder, especially if we throw in the Pixar shorts that have won Oscars. Zauzmer’s method is not what one might predict. He posits that the combined critics’ and fans’ scores on Rotten Tomatoes genuinely tend to reflect the perceived quality of the films involved, and he charts the nominated animated features and winners in relation to their scores.

The results are pretty clear, in that Spirited Away is arguably the best animated feature made in the time since the Oscar category was instituted in 2001. In fact, I’ve seen it on some of the lists of the best films made since 2000, and it’s not an implausible choice either way. Shark Tale? I haven’t seen it, but I suspect it deserves its status as the least well-reviewed nominee in this category.

The results are pretty clear, in that Spirited Away is arguably the best animated feature made in the time since the Oscar category was instituted in 2001. In fact, I’ve seen it on some of the lists of the best films made since 2000, and it’s not an implausible choice either way. Shark Tale? I haven’t seen it, but I suspect it deserves its status as the least well-reviewed nominee in this category.

Using this evidence, Zauzmer zeroes in on Pixar, which has won the animated feature Oscar nine times out of its eleven nominations. In six cases, the Pixar film was the highest rated among that year’s nominees: Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, WALL-E, Up, Inside Out, and Coco.

In two cases, Pixar was rated highest but lost to a lower-rated film: Shrek over Monsters, Inc., and Happy Feet over Cars. I personally agree that neither Shrek nor Happy Feet should have won over Pixar. (Sorry, George Miller!)

Zauzmer finds three cases where Pixar did not have the highest rating but won over others that did: Ratatouille beat the slightly higher-rated Persepolis, Toy Story 3 should have lost to the similarly slightly higher-rated How to Train Your Dragon, and Wreck-It Ralph was way ahead on RT but lost to Brave. Wreck-It Ralph definitely should have won, and the sequel probably would have, had it not been unfortunate enough to be up against the highly original, widely adored Spider-Man: Into the Spiderverse.

The conclusion from this is that the Academy “wrongly” gave the Oscar to Pixar films three times and “wrongly” withheld it twice. As Zauzmer points out, this is “certainly not a large enough gap to suggest that the Academy has a bias towards Pixar.” This is pleasantly counterintuitive, given how often we’ve seen Oscars go to Pixar films.

Oscarmetrics offers interesting material presented in an engaging prose style, more journalistic than academic, but thoroughly researched nonetheless.

In his introduction, Zauzmer points out that the book only covers up to the March, 2018 ceremony. It obviously can’t make predictions about future Oscars, though it might suggest some tactics you could use for making your own if so inclined. Zauzmer has been successful enough in the film arena that he writes for The Hollywood Reporter and other more general outlets. You can track down his work, including pieces on this years Oscar nominees, here.

Reporting from the Wisconsin Film Festival 2019

Hotel by the River (2018).

Kristin here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival is all too rapidly approaching its end, so it’s time for a summary of some of the highlights so far.

New films from around the world

We have not quite managed to catch up with all the recent films by Korean director Hong Sang-soo, but we took a step closer with Hotel by the River. It’s an impressive film, in part by virtue of its setting. The Hotel Heimat stands beside a river which is covered in ice and snow. Even the further shore with its mountains, is reduced to shades of light gray in the misty, cold light. All of this is enhanced by the black-and-white cinematography that creates a background against which the characters and the small trees create simple, austere compositions.

The story involves an aging poet who somehow senses that he is going to die soon and settles in at the hotel to wait for death. His two sons, one a well-known art-film director with a creative block and the other secretly divorced, come to visit. A young woman who has recently broken up with her married lover is visited by a sympathetic character who may be her sister, cousin, or friend. They encounter the poet by the river, and he compliments them effusively for adding to the beauty of the scene. Conversations about life ensue. The women take naps, the men bicker. Sang-soo’s typical parallels and repetitions unfold. It’s a lovely film.

Yomeddine, an Egyptian film, created something of a stir last year when it was shown in competition at Cannes. It was a surprising choice, given that it is writer-director A. B. Shawky’s first feature.

It’s also a modest, low-budget film, and like so many such films made in countries with limited production, it’s a road movie. No need to build sets or use complex lighting. The two central characters are Beshay, dropped off as a small child at a leper colony by his father, and Obama, a young orphan who knows nothing of his birth parents. Coincidentally, they both come from Qena, a city north of Luxor on the great Qena Bend of the Nile. Longing for links to their origins, the two set out there. At first they ride in the donkey cart that Beshay uses in his work as a garbage-picker, but later, when the donkey dies, they travel on foot and occasionally by train, riding without benefit of tickets.

There’s no indication where the orphanage and leper colony are and thus how long a trek the two face. I’m pretty familiar with the Nile, but they follow the large canals and train tracks that run parallel to the river on both banks. The villages along their route look pretty much alike. Shortly into the trip, however, Shawky suddenly confronts us with the Meidum pyramid (above), which acts as a handy landmark to reveal that the pair have a long way to go. It’s Shawky’s only display of an ancient site. Beshay and Obama have no idea what it is, but they explore it and spend the night in its small chapel.

Yomeddine is a likeable film blending humor, pathos, and a little suspense as it follows the pair on their quest. It’s also a plea for tolerance. Beshay’s deformities scare off those who wrongly think that leprosy is contagious (with treatment it is not), and Obama is denigrated by his classmates as “the Nubian,” for his relatively dark skin. Their sometimes prickly odd-couple friendship is a demonstration of how people of various backgrounds, including those on the margins of society, can get along. That, I suspect, is what led Cannes programmers to include it in the competition.

Overall it’s a well-made, entertaining film, perhaps an indication that we shall see more from Beshay on the festival circuit in the future.

[April 19: Yomeddine won the Audience Favorite Narrative Feature at the Wisconsin Film Festival.]

Ralph and Venellope Back in 3D

Phil Johnston with Ben Reiser, Senior Programmer, Wisconsin Film Festival.

UW–Madison grad Phil Johnston was a key participant in the festival. Not only did he program one of his favorites, Ozu’s Good Morning (1959), but he also visited a class and ran a public event around Wreck-It Ralph 2: Ralph Breaks the Internet. Phil was a writer on both entries and co-director on the second, while also providing screenplays for Zootopia (2016) and Cedar Rapids (2011). We’re very proud of him, and we were happy to welcome him back home.

I love both the Wreck-It Ralph films, but I don’t like to go to hit movies early in their runs. We usually wait a few weeks till the crowds die down. As I recently pointed out, though, that means risking no longer having the option of seeing a 3D film in that format. So it happened with both Ralph Breaks the Internet and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

Fortunately for us, the UW Cinematheque added permanent 3D capacity to its projection options, so Ralph 2 was shown in that format. The 3D much enhances the sense of being surrounded by the myriad “websites” in the scenes showing general views of “the internet,” as well as by the vehicles and netizens that flash past in their travels.

Both Ralph films display a non-stop inventiveness, and I agree with Peter Debruge’s comment that Wreck-It-Ralph “ranks among the studio’s very best toons.” The sequel is, if anything, even better. The scene in which Venellope von Schweetz confronts the full panoply of Disney princesses and tries to prove herself one of them became a classic before the film was even released.

The notion of Venellope moving from the sickly sweet “Sugar Rush” arcade game to the wildly dangerous online “Slaughter Race” (see bottom) is a great concept to begin with, and her rendition of her “Disney princess” song, “A Place Called Slaughter Race” is hilarious. The film was robbed, in my opinion, when her song didn’t get nominated for a Oscar.

The film has jokes to burn, as in the clever puns on the signs that flash in the internet and game scenes. I look forward to being able to freeze-frame the images to catch the many I missed. Unfortunately the Blu-ray release will not be in 3D. Disney has been phasing out releasing its 3D films in that format ever since Frozen, but you could for a time order such discs from abroad. (Other studios are following suit, and our 3D copy of Into the Spider-Verse is wending its way from Italy as I type.) I am told that the only 3D Ralph will be the Japanese version, at something like $80. Fortunately, it looks great in 2D as well, but I’m glad to have seen it on the big screen in 3D once.

So old they’re new again

Jivaro (1954).

Recent restorations have become a increasingly important component of our festival’s wide variety of offerings. Selections from the previous year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna are now regularly programmed, and we had visiting curators presenting their new projects. (For a brief rundown of the Bologna offerings this year, see here.)

Another film taking advantage of the Cinematheque’s new 3D capacity was Jivaro, a jungle-adventure film of the type more popular in the 1950s and 1960s than it is now. Having seen a such films when growing up, I can say that Jivaro is better than many of its type.

It was made late in the brief early 1950s vogue for 3D, so late in fact that the studio decided to release it only in 2D. One attraction of its screening at the WFF was the fact that it was screening publicly for the first time ever in its intended format. Bob Furmanek, 3D devotee and expert, introduced the film and took questions afterward; he has been a driving force in the restoration of this and many other 3D films. (His immensely valuable site is here.) Below Bob shows one of the polarizing filters used in projection booths.

The film was highly enjoyable, partly for the 3D (shrunken heads thrust into the lens and spears coming at us!) and partly for the comfortable familiarity of its genre tropes. There’s the genial South American trader who has gained the respect of the locals, the seemingly deluded adventurer with a map to a lost treasure who turns out to be right, the gorgeous woman who shows up dressed in tight blouse, skirt, and high heels, the beautiful local girl in hopeless love with a white man, and so on. (The beautiful girl was an early role for Rita Moreno, who labored as an all-purpose-ethnic bit player for years before West Side Story made her a star.) Leads Fernando Lamas and Rhonda Fleming supply beefcake and cheesecake, respectively, at regular intervals. Lamas (as you can see above) barely buttoned his shirt across the whole film. It’s hot in jungles.

For those with 3D TVs, Jivaro is already out on Blu-ray.

The Museum of Modern Art has followed up its restoration of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) with one of Forbidden Paradise (1924). Both were shown at this year’s festival. We saw Rosita at the 2017 Venice International Film Festival and wrote about it then. In preparing my book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (2005; available free as a PDF here), I saw an incomplete copy of one preserved in the Czech film archive–a key element in constructing this new version. Naturally I was eager to see the new scenes and much-improved visual quality of the MOMA restoration. Archivist Katie Trainor was present to explain the process, which yielded a version that is about 90% the length of the original.

Of all Lubitsch’s Hollywood films, this is the one that most looks back to his German features of the late 1910s and early 1920s. For one thing, his frequent star of that period, Pola Negri, was by now in Hollywood and worked here with him again here, their sole Hollywood collaboration. She stars in a highly fanciful tale of Catherine the Great, and the quasi-Expressionistic sets present an appropriate version of historical style. The set in the frame above (taken from a 35mm print, not the restored version) is my favorite, with its lugubrious creatures crouched atop the wall. Grotesque sphinxes? (The designer might have been thinking of the the two beautiful granite sphinxes of Amenhotep III that sit to this day by the Neva River in front of the Academy of Arts, though they were brought to Russia decades after Catherine’s reign.) Or just elaborate gargoyles?

The plot centers around a brief affair between a young officer (Rod La Rocque) and the licentious Catherine. A brief attempt at revolution flares up. All this is deftly dealt with by the Lord Chamberlain, played by Adolf Menjou, hamming it up with eye-rolls and knowing chuckles.

It’s not first-rate Lubitsch, largely lacking the lightness that one associates with the director, and which he had already achieved in his second Hollywood film, The Marriage Circle (1924). But it’s a pleasant entertainment, and the set and costume designs are visually engaging–especially in this excellent new restoration.

David watched None Shall Escape (1944) for his book on 1940s Hollywood, but I was unfamiliar with it until its restored version was shown here as one of the Il Cinema Ritrovato contributions. The film was originally made by Columbia and was presented at our fest in a 4K restoration from Sony Pictures Entertainment, the parent company of Columbia. Rita Belda, SPE’s Vice President of asset management, was here to explain the complicated process. She summarizes it here as well.

The film had been carefully preserved, probably because of its historical importance as a unique fictional depiction of Nazi atrocities. The original negative and three preservation positives survived. These had the usual scratches and tears, as evidenced in the first comparison image above. A significant challenge, however, was that the prints had all been lacquered in a misguided attempt to preserve them. The result was staining throughout, evident in both comparison images. Digital removal allowed for a stunningly clear image throughout the finished version.

None Shall Escape is notable as the only Hollywood film made during the war to depict major aspects of the Holocaust. It begins with a frame story set in the future. This postwar trial of Nazi criminals remarkably prefigures the Nuremberg trials. Testimony is given against a single officer, who stands in for all the accused officers and collaborators. Wilhelm Grimm begins as a schoolteacher in a small Polish city but proves so devoted to the Nazi cause that he rapidly rises through the ranks. After the city is seized during the German invasion, Grimm comes to rule the city. At the trial, townsfolk who had resisted and suffered under his domination testify, and their stories unfold as a series of lengthy flashbacks.

The film is an effective and moving drama, not least because it demonstrates the explicitness with which it was possible to depict Naziism in this period. It shows, as Hitler’s Children (1943) did, the insidious indoctrination of young people by the Nazi party. But no other film depicted the rounding up of Jews and their dispatch to concentrations camps–named as such.

Director André De Toth, though not a top auteur, again proves the value of sheer skill and artistry in filmmaking, a value that David recently discussed in relation to Michael Curtiz. None Shall Escape is an impressive example of the power of the classical Hollywood system–and a beautiful film, as one might expect from cinematographer Lee Garmes. Marsha Hunt gives a moving performance as Marja, another schoolteacher who fearlessly persists in opposing Grimm and his oppression of the townspeople; it is a pity that she never achieved the stardom that she merited.

Perhaps most notably, De Toth stages a powerful scene in which Jews rebel against being packed into trains and are ruthlessly mowed down by their captors. It must have given many Americans a first glimpse of what would soon be revealed by newsreels and personal testimony.

Now, back to the movies. More festival coverage to come, when we get time to write!

For more on early 3D, see David’s entry on Dial M for Murder.

Ralph Breaks the Internet (2018).

Vancouver 2018: Panorama of the Rest of the World, the sequel

Seder-Masochism (2018)

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival is over, but we still have films to talk about. Here are four, and David and I will probably post another blog apiece. Between Venice and Vancouver, we have seen a lot of great and very good films recently. Once again, the claims of the death of cinema are robustly refuted.

Dogman (Matteo Garrone, 2018)

Garrone is best known outside Italy for his 2008 film Gomorrah. While that film was about gangs and organized crime in Naples, Dogman centers around a shifting relationship between a meek-mannered dog/boarder/groomer who has fallen in with a volatile, enormous local thug.

The title emphasizes the honest side of Marcello’s life, and we see some comic scenes of him with dogs. Soon, however, it is revealed that he sells cocaine on the side and sometimes acts as a getaway driver for thefts committed by the monstrous ex-boxer, Simoncino. Eventually he even takes the fall for a robbery and spends a year in jail in Simoncino’s place.

We’re clearly intended to side with this sad sack. After one house robbery, Simoncino’s partner reveals that he put a dog in the freezer to keep it quiet. Marcello sneaks back in and, a suspenseful and remarkable scene, attempts to revive the frost-covered animal. He also dotes on his daughter and seemingly pursues his criminal activities in order to be able to take her on “adventures,” including scuba-diving.

Despite this sympathetic side, however, Marcello never seems to consider giving up crime; he’s mainly interested in getting his fair share of Simoncino’s ill-gotten gains. Although the film is continually entertaining and suspenseful, its ending is somewhat disappointing. We are left knowing what Marcello’s probably fate will be, but we have little sense of his attitude toward what has happened.

Marcello Fonte, looking like a rather emaciated version of the comic Toto, won the Best Actor prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

Magnolia has the US rights and plans to release Dogman in 2019.

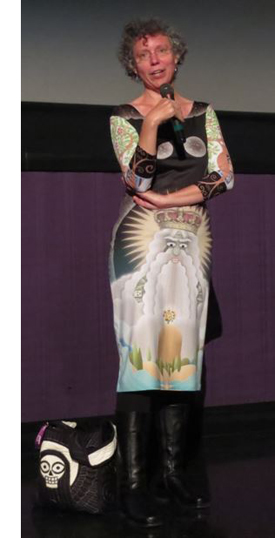

Seder-Masochism (Nina Paley, 2018)

Seder-Masochism is the only US film I’ll be writing about from Vancouver. (We tend to skip US films here, since we assume we can see them in the US.) Paley’s not part of the Hollywood establishment or even the mainstream indie scene. It’s not easy to see her wonderful animated films on the big screen, but their bright colors and imaginative graphics deserve to be shown that way.

Seder-Masochism is Paley’s second feature, after Sita Sings the Blues (2008). She does all the animation herself, holed up, as she puts it, like a hermit with her computer. She also avoids the standard distribution methods for indie films, because she’s an opponent of copyright for artworks. She provides open access to her films, initially at festivals and then online. (For more on this, see my transcript of a Q&A I helped run when Sita played at Ebertfest in 2008.)

Seder-Masochism is Paley’s second feature, after Sita Sings the Blues (2008). She does all the animation herself, holed up, as she puts it, like a hermit with her computer. She also avoids the standard distribution methods for indie films, because she’s an opponent of copyright for artworks. She provides open access to her films, initially at festivals and then online. (For more on this, see my transcript of a Q&A I helped run when Sita played at Ebertfest in 2008.)

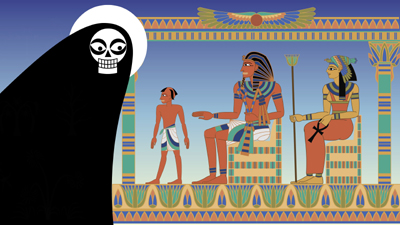

I should say that no one should assume from the title that this film is grim and/or anti-Jewish. On the contrary, it’s a witty exploration of the Exodus myth and its historical links to the decline of early goddess worship in favor of all-powerful male gods in monothesism. The framing situation is a conversation between Paley and her father conducted shortly before his death, with Paley as a small goat and her father as God (see top).

I should say that no one should assume from the title that this film is grim and/or anti-Jewish. On the contrary, it’s a witty exploration of the Exodus myth and its historical links to the decline of early goddess worship in favor of all-powerful male gods in monothesism. The framing situation is a conversation between Paley and her father conducted shortly before his death, with Paley as a small goat and her father as God (see top).

This conversation is a mix of humor and serious points about Judaic traditions and particularly the celebration of Passover. The story of Moses and the Exodus is rendered in much the same way she treated the tale of Sita and Rama from the Hindu epic, the Ramayana–with musical numbers. Moses is introduced with “Moses Supposes,” from Singin’ in the Rain, and, inevitably, there is a “Go Down, Moses” episode. Unlike Sita, where blues songs were used throughout, the musical pieces in Seder are wide-ranging, culminating in a brilliant three-minute summary of the history of the territory which is now Israel, done to “This Land is Mine,” the song written to the theme of Otto Preminger’s Exodus. (The sequence, as well as several other excerpts from Seder are available on YouTube.)

The sequences set in ancient Egypt are generally accurate. I was amused by the fact that the animal and bird hieroglyphs in the background inscriptions moved rhythmically during the musical numbers, and the Hathor heads on the sistrums sang along. Using Hathor, the cow goddess, as the golden calf was an inspiration.

Seder-Masochism got the most enthusiastic applause I heard at the festival, partly because the filmmaker was present (in her custom Seder dress). There were Sita fans in the audience, and one Jewish lady asked how she could get a copy to show her 12-year-old daughter. Paley replied that the film will continue to play festivals and probably be available on the fim’s website for download in the spring.

In the meantime, watch for it at festivals–or let the organizers know that you want to see it on their schedule. We were happily surprised to see a full-page ad for the Los Angeles Animation Is Film Festival (October 19-21) in the current Variety (above left) and illustrated by an image derived from the film. You may find others.

Styx (Wolfgang Fischer, 2018)

I was surprised to discover that so far Austrian director Wolfgang Fischer’s Styx has not been picked up by a North American distributor. It seems like the sort of film to appeal strongly to audiences. It’s protagonist is a strong, ultra-competent woman, it has a riveting plot full of suspenseful situations, and it deals with the immigrant crisis facing Europe.

A long portion of the film contains no real dialogue. The opening sequence occurs at the scene of a traffic accident where the heroine, Rike, is established as a doctor as she heads the team treating the victim. Cut to her provisioning her yacht for a solo trip. A lovely shot of a compass “walking” its way down a map establishes her route and distant goal: Ascension Island (see bottom). Her departure reveals that her starting point is Gibraltar (above). From that point, we watch Rike expertly dealing with her vessel, enjoying the solitude of the ocean, and reading about Darwin’s activities on Ascension.

Apart from a few overheard commands during the initial emergency scene, there is no dialogue until Rike makes radio contact with a nearby commercial vessel which warns of a serious storm approaching. A tense scene of her struggle to deal with the storm at night creates the first major suspense of the film. From her arrival in an ambulance in the opening sequence, actress Susanne Wolff is present in every scene, and as an experienced sailor she was able to handle the yacht and do without a stunt double.

Rike comes through the storm without difficulty, but a leaky vessel crowded with African immigrants striving to get to Europe is visible in the distance. Ordered by a coast-guard official not to interfere, she uneasily waits for a sign of a rescue vehicle that still has not shown up after hours of waiting. One teen-aged boy manages to swim from the derelict ship, and he complicates her situation considerably. The dilemma remains: try and take the rest of the refugees on board her small yacht or wait for the promised rescue.

The remainder of the film generates unrelieved suspense as Rike debates what to do and Kingsley begs her to rescue his sister, still abroad the sinking boat. A non-actor discovered in a school in Nairobi, Gedion Oduor Weseka is convincing and touching as the desperate boy.

Nearly all of Styx was shot at sea, with Fischer’s small crew mounting their camera hanging off the sides of the boat and scrambling to keep out of sight during filming. No special effects were used for the storm and other ocean scenes. At intervals some impressive extreme long shots from overhead, presumably taken by drones, emphasize the yacht’s isolation in the vastness of the sea.

The film is riveting from beginning to end. I recommend it, though at least for North America, festival screenings are probably the main places where it can be seen. Perhaps it will eventually be available on streaming services. In some European countries, it will probably be released theatrically.

Transit (Christian Petzold, 2018)

The central premise of Transit resembles that of Casablanca. A group of émigrés are desperately awaiting the letters of transit that will allow them to flee fascist Europe for North America. In this case they’re in Marseille rather than Casablanca, and the plot focuses on one rather ordinary, non-heroic man–or so he seems. Our protagonist is Georg, a Jew lingering in Paris as the authorities arrest fugitives. The authorities are working for a fascist regime, though Nazis are never mentioned specifically.

Moreover, the settings and costumes are mainly modern. Early on Georg flees a round-up through allies covered with spray-painted graffiti (below), and the vehicles in the streets are all contemporary models. Petzold’s avoidance of period mise-en-scene sets up a strange, somewhat surrealist world, but it also invites us to consider the parallel with current social problems.

By chance Georg gains possession of the manuscripts and papers of Weidel, a well-known author who has met a bloody end in a cheap hotel room. Fleeing to Marseilles with a wounded fellow Jew who dies along the way, Georg visits the Mexican consulate and is mistaken for Weidel, whose transit papers for him and his estranged wife have been approved. Naturally Georg accepts the error. While waiting for the papers to come through, he befriends his dead friend’s widow and her son, immigrants to Europe from the Maghreb, and by chance encounters and falls in love with Weidel’s wife (who does not realize her husband is dead), hoping to use the two letters of transit to escape to a new life with her.

Between the inexplicable modern settings and costumes and the extraordinary coincidence of this meeting, the film is far from being realistic. It reminded me of the late films of Manoel de Oliveira (see our earlier reports on Doomed Love, Eccentricities of a Blonde-Haired Girl, The Strange Case of Angelica, and Gebo and the Shadow), with touches of Bresson in the situation and the acting, particularly of Franz Rogowski as Georg. But Petzold is not simply imitating these and other directors. Transit is a remarkable, original film, one of the best we saw at Vancouver.

Transit has been acquired for US distribution by Music Box for an early 2019 release. Definitely keep an eye open for a screening near you, most likely in festivals and large-city art houses and perhaps eventually on streaming..

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Styx (2018).

THE LOST WORLD refound, piece by piece

Kristin here:

Like just about all kids, I was fascinated by dinosaurs for a while. That’s probably why my mother bought a copy of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 fantasy-adventure novel, The Lost World, at a yard sale and gave it to me to read while I was sick in bed. I must have been about nine. It was a battered photoplay edition, complete with photos of scenes from the 1925 movie. I read other Victorian-Edwardian fantasy-adventure books, mostly Verne and Haggard, at around the same time. I suppose they prepared me for reading The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings at age 15 and developing a life-long attachment to them. This doesn’t mean that I consider The Lost World a masterpiece, but having come to it so young, I retain a fondness for it. I was interested to find out what the new Flicker Alley release of a new restoration of the film is like.

Doyle’s novel deals with a scholar and explorer, Professor Challenger, who has recently visited a remote site in South America and is ridiculed by all for his claims that dinosaurs survive on an inaccessible plateau there. The hero, Edward Malone, a lovelorn reporter courting a woman who insists she wants a daring, heroic husband, enlists on an expedition to test Challenger’s stories. So does a skeptical rival of Challenger’s, Professor Summerlee, and a hunter-adventurer, Sir John Roxton, who wants to add a stuffed dinosaur to his other trophies. Many adventures follow, including vengeful Spanish guides marooning the expedition atop the plateau, where they encounter dinosaurs, ape-men, and Indians. The team escapes and manages to take a pterodactyl back to London. Challenger’s reputation is restored.

Following on the novel, I saw the 1960 Irwin Allen version of The Lost World. At the age of perhaps ten or eleven I enjoyed it, though I did recognize that Jill St. John’s character was a total and unnecessary fabrication and the “dinosaurs” were lizards with prostheses.

The 1925 version

Naturally when I was a grad student in film studies, I took my first opportunity to see the 1925 version. It was produced by the important studio and distributor First National Pictures three years before it was absorbed by the upstart Warner Bros. In those days the only version available was a 50-minute abridgement made by Kodascope, and it was not, to say the least, impressive.

I cannot say that I paid much attention to the subsequent restorations: the 1998 George Eastman House version, which, while still incomplete, was a distinct improvement, and the the 2000 David Shepard version, which was basically the same but with digital improvements to sound and image.

The 2016 restoration by Serge Bromberg’s Lobster Films as presented now on Blu-ray by Flicker Alley, has added considerable footage. This extends the film to 103 minutes, close to its original running time. The main thing missing is a scene of cannibals attacking the expedition members as they travel upriver to the controversial plateau, as well as a few other brief moments.

As an adaptation, it’s a distinct improvement on the 1960 version. After all, the novel was only 13 years old when it was made. Doyle was still alive; he would not publish his final Sherlock Holmes story until 1927 and his final works of fiction until 1929. Conventions and tastes in popular fiction, whether filmic or literary, had not changed nearly as much as they had by Irwin Allen’s day.

The main casting was impeccable, with Wallace Beery the perfect choice for the powerful, pugnacious Challenger (above) and Lewis Stone for the epitome of British stalwart rectitude. The film even managed to do a good job of concocting a love interest by introducing Paula White (Bessie Love), the daughter of the original discoverer of the lost-in-time plateau and eager to participate in an expedition to rescue her marooned father. Then it gave her little to do. Bessie Love just has to look terrified at intervals, in a series of close-ups surrounded by an iris and with a blank background–clearly shot later with someone telling Love just to glance in all directions and register fear. These moments add up to something a realization of a Kuleshov experiment.

Her presence does, however, allow Stone to give perhaps the most subtle and sympathetic performance in the film. He’s in love with White but nobly gives her up to Malone. As Malone, Lloyd Hughes manages to look suitably handsome and impetuous. Arthur Hoyt, older brother of director Harry O. Hoyt), plays Professor Summerlee. His many “little man” roles later included the hotel owner in It Happened One Night, and he was one of Preston Sturges’ regular actors. (“Looking perpetually befuddled was Hoyt’s stock-in-trade,” as I. S. Mowis puts it in his IMDb biography of Hoyt.) Unfortunately the film exaggerates Summerlee’s somewhat amusing traits, thereby making him a strictly comic character. (One wonders how Claude Rains, so very dissimilar from Beery, could be chosen for the same role in the 1960 version. Casting against type, presumably.)

By the way, although the film seems basically to be set in the Edwardian era of the novel’s original publication, the introduction to the final London portion of the story shows Piccadilly Circus at night, including a movie palace show The Sea Hawk (1924), another First National release that included Wallace Beery and Lloyd Hughes (Malone) its cast.

A little synergy that brings the story up to date.

Puppets and people

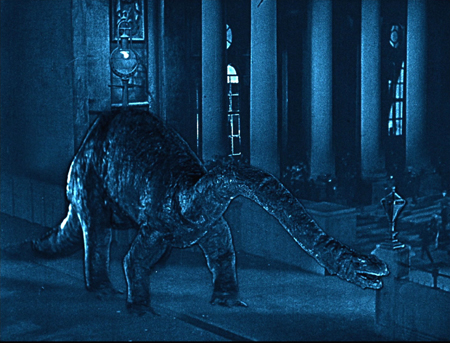

The main attraction of the film, of course, is its technology. Some of it was quite innovative. It is thought to be the first time when the special effects of a feature film were largely accomplished through puppet animation.

There had been earlier puppet films, including Ladislas Starevich‘s realistic creation of artificial insects apparently acting out conventional melodramas. Accomplished though they were, these did not mix live-action with real actors in the same shots, as do the miniature landscapes with the moving dinosaurs.

In The Lost World, combinations usually involve the actors placed in the lower foreground, observing the dinosaurs from varying distances. Atop this section, for example, in a very skillfully done shot, an allosaurus approaches the campsite of the expedition members. The place where the live-action at the lower right joins the miniature set at the upper left is difficult to discern, and the careful lighting of both areas aids in the illusion.

The late scenes of the film, where a brontosaurus escapes into London’s streets and causes panic resorted to a new and complex technology, moving mattes. This device involved using stencils cut for each frame and doubly exposing prints from two negatives. Moving mattes allowed figures filmed separately to be inserted into scenes without the use of superimpositions. The result usually was fairly obvious, betrayed by an evident join line around the added figure. Differences in texture and lighting also caused problems. Still, given the technical limitations of the day, the results are impressive. (The most famous use of moving mattes in this era was probably the reunited couple’s oblivious stroll through traffic in Sunrise.)

The Lost World drew more heavily on stationary mattes, and for the most part, the technology is pretty convincing. The scene of the allosaurus-triceratops-pterodactyl fight (at the top) contains a stationery matte. The lower part of the frame is a river with plants on the banks swaying in the breeze. About a third of the way up the composition, there is a join to the miniature set in which the action was animated. There the plants are completely stationery, but the movement of the real plants in the lower area gives a degree of verisimilitude to the whole scene. The shot of the team confronting the allosaurus at the top of this section also uses this technique.

Digital copies let us pause and figure out some of O’Brien’s secrets. After the allosaurus has dispatched the unfortunate triceratops seen in the image at the top of this entry, a dramatic moment occurs in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it flurry of motion as it suddenly snatches a pterodactyl in mid-flight and kills it. Pausing on the action, we can see that O’Brien used wires to support the allosaurus during its leap, as well as nearly invisible wires along which to slide the pterodactyl. I didn’t notice any other scenes in which O’Brien had to resort to visible props.

And at least the dinosaurs, unlike King Kong, didn’t have fur that ruffles almost continually, betraying the movements of the animators’ fingers in between exposures of the frames. As a result, the animation in The Lost World almost looks more sophisticated than that of Kong.

Moreover, O’Brien’s puppets, constructions of rubber and foam over metal skeletons, included balloons inside that could have air pumped in and out to simulate breathing. It’s a measure of the man’s inspiration that he realized how much this technique would contribute to the lifelike quality of the dinosaurs.

One of the supplements gives another insight. It is listed as “Deleted scenes,” or outtakes, but occasionally O’Brien or perhaps one of his assistants (the footage is too indistinct to tell which) pops into the image for a few frames, incongruously appearing submerged to his waist in a primordial landscape.

Such images give a sense of the considerable scale of the miniature landscapes and the puppets, as well as the labor involved in this novel endeavor.

The new print

This newest restoration, having been cobbled together from many disparate elements, inevitably is variable in its visual quality. Much of it is splendid, as indicated in most of the images reproduced in this entry, especially the one at the top. Others are clearly worn, with light lines, as in the shot above of Challenger and Summerlee watching a brontosaurus pass in the background. Again a matte shot has been used, its joint probably running along the top of the little sandy ridge behind which the men hide.

The rather poignant scene of the dinosaurs fleeing from a volcanic eruption is unfortunately worn as well. Such stretches, however, are in the minority.

The new version also includes tinting and toning based on recently discovered footage, as well as a brief scene combining red and blue colors when Malone throws a torch into the mouth of an allosaurus to drive it away.

The disc comes with a booklet by Bromberg outlining the extensive restoration work on the versions of The Lost World, as well as the disc’s two musical-track options, one by Robert Israel and one by the Alloy Orchestra. Supplements include a commentary track by Nicolas Ciccone and some short films and clips by O’Brien. The Silent Era website offers a detailed rundown on the many video releases of The Lost World. Once more Lobster Films and Flicker Alley are to be congratulated on another contribution to the retrieval of cinema’s history.