Archive for the 'Animation' Category

Pesky brats, adventurous ducks, and jiving swamp critters

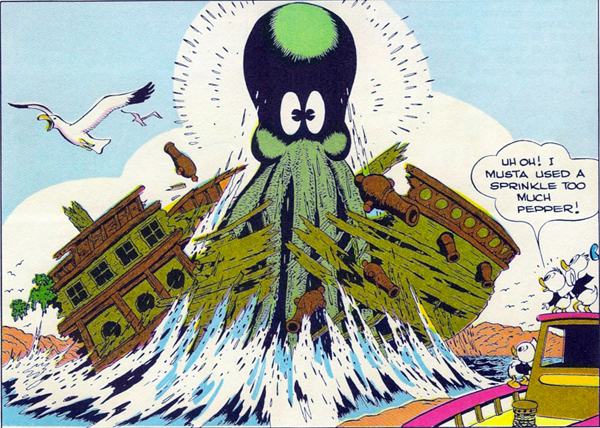

Carl Barks, Ghost of the Grotto (1947).

DB here:

We never need an excuse to write about comic strips or comic books. We’re fans and, just as important, we think of them as having important connections to film. We’re particularly fond of classic funny-animal comics, from Krazy Kat (the greatest) onward. So I got a double dose of pleasure reading Mike Barrier’s Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books. It taught me a lot about the history of some favorites, and it set me thinking about some overlaps and divergences between film and graphic art.

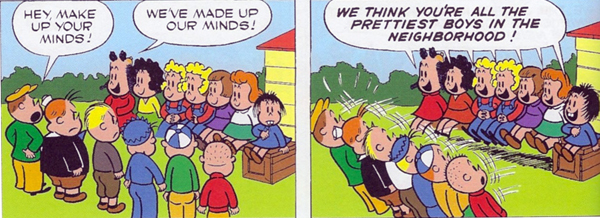

No Girls Allowed

Like Mike’s Disney book The Animated Man, Funnybooks is at one level a scrupulously researched business history. It explains how publisher Western Printing and Lithography (of Racine, WI) became the center of a thriving industry. Before the mid-1930s the company’s juvenile line came out chiefly under the Whitman imprint. Its illustrated storybooks licensed characters from Disney and comic strips like Dick Tracy and Little Orphan Annie. But Hal Horne and Oskar Lebeck pushed toward creating comic books proper, those inviting items that could compete with the superhero titles that were emerging. Their instincts were sound: Western’s comics, distributed by the Dell company, sold hundreds of thousands of copies.

After several tries at compiling daily comic strips into a single volume, Lebeck turned to original content. In the early 1940s he hired Walt Kelly, Carl Barks, and John Stanley. All had worked in film animation (Kelly and Barks for Disney, Stanley for Max Fleischer), but they adjusted to the demands of more static cartoon art. Into the rise and fall of Western and Dell, Barrier weaves the personal stories of the three creators and their less famous peers. Funnybooks is at once industrial history and a collective biography.

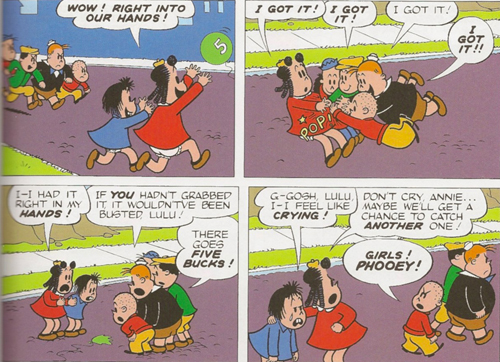

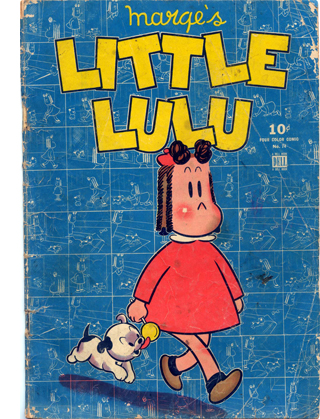

John Stanley, the least known of the trio, was brought on to do stories of Little Lulu, the stolid, crisply-curled girl created by Marjorie Buell. Stanley wrote and drew the entirety of the first book in 1945. The cover presents a heroine as blank as Hello Kitty and a background grid as febrile as a Chris Ware design. Afterward, Stanley chiefly served as writer on the Lulu stories, providing other artists with detailed scenarios and sketches. The panels might be somewhat stiff, but the plots were admirable. Often turning on mean childhood pranks, they were steeped in spite and petty revenge.

I remember enjoying Lulu’s stories, especially their verbal comedy. When Tubby (I think it was) hits Lulu with a pie, he says, “I’ve thrown a custard to her face.” Lulu replies: “I liked breathing out and breathing in.” This was probably a post-Stanley passage, but the fact that I’ve remembered it for sixty years indicates the ways grown-up jokes can stick in the unformed brain. (I knew Boris Badenov before I knew Boris Godunov.)

Mike is very good on the bitter humor that Stanley puts on display as Lulu and her girl pals skirmish with Tubby and his gang of sexist bullies.

His characters were never vulnerable to the suggestion so often made about the children in Charles Schulz’s comic strip Peanuts—that they were adults masquerading as children. They were instead children whose quarrels and schemes echoed adult life.

Lulu evolved, Mike shows, into a trickster who constantly showed up the boys, even as she herself was sometimes slapped down. In one story a rich boy, seeing Lulu longing for pastries in a shop window, doesn’t consider buying her one. Instead, he buys the shop and drops the shade on the window. Walking away on his golden stilts, “he felt very happy because now the poor little girl wouldn’t have to look at things she couldn’t buy.” Another compassionate conservative.

Stanley drew many other characters, including Bushmiller’s Nancy and the ingratiating Melvin Monster. His career fizzled out when comic-book publishing hit hard times in the 1950s. He wound up working in a factory that made aluminum rulers.

Rowrbazzle

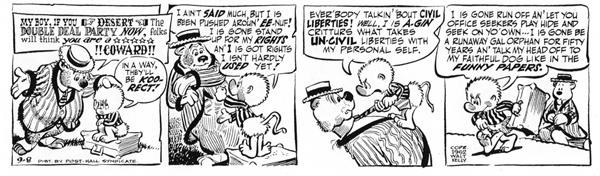

Walt Kelly fared better. In the beginning he he worked on many series but he gained fame with his own creation, the enduring swampland of Pogo Possum and his friends. “Ensemble comedy,” Mike calls the remarkable menagerie Kelly assembled.

At first speaking in mangled Southern accents, Pogo, Albert the Alligator, Porkypine, Howland Owl, Churchy la Femme (another joke passing over kids’ heads), and a host of other creatures developed a patois as bizarre as the rodomontade you hear in Coconino County. Characters sang nonsense songs, recited garbled poetry, and engaged in pun-filled miscommunication. The wordplay was enhanced by lettering adjusted to different characters, notably the Gothic script associated with Deacon Mushrat and the circus-ballyhoo font employed by con artist P. T. Bridgeport.

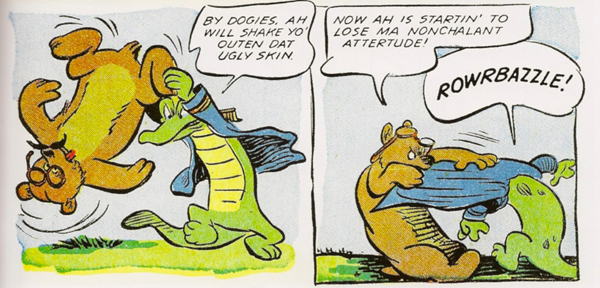

Slapstick went along with the verbal pyrotechnics. Kelly’s fluid line created complex equivalents of movie pratfalls, each one enlivened by fussy details (check the bear’s glasses below) and punctuated by unique sound effects. Barrier reports that in one Kelly comic, a cannon explodes with the sound “FRED.”

In all, eccentricity was the watchword, usually accompanied by food, or characters trying to get it. Albert had a disconcerting habit of accidentally eating his friends. Any of the crew might launch into retelling a classic children’s story featuring the entire cast. These were fairy tales not so much fractured as splintered. In all, it’s astonishing how many pictorial and verbal gags Kelly could cram into four daily panels.

Kelly, a superb draftsman, learned the secret of round forms in his Disney days, and Mike traces how this tendency toward cuteness helped make Pogo a success. But Kelly also had a nutty sense of humor that set him apart from other Western/Dell artists. Mike surveys Kelly’s range, from liberal political cartoons to Our Gang comics, and he treats with care how Kelly’s work included both racial caricatures and more affirmative images of African Americans.

Mike shows how Kelly’s talents outgrew the Dell family. As Pogo and his pals became more popular with intellectuals, the comic-book format proved a rickety vehicle for the artist’s ambitions. Kelly shifted his energies toward daily and Sunday strips that attracted nation-wide attention, not least for satirizing Joseph McCarthy and the Jack Acid (aka John Birch) Society. Pogo’s swamps, I thought at the time, became the liberal counterweight to Al Capp’s reactionary Dogpatch. Like Doonesbury and Calvin & Hobbes later, the dailies became incorporated into best-selling books published by Simon & Schuster. Those collections, to be found on every college kid’s bookshelf in the 1960s and 1970s, made Pogo as much a part of the official counterculture as Frodo Baggins. “We have met the enemy and he is us” became the slogan of a generation.

A peculiar affinity with those damn Ducks

If Funnybooks has a protagonist, it is Carl Barks. No wonder. Unlike Stanley, he both wrote and drew his books. Unlike Kelly, he was anonymous. A modest worker prized by all who knew him, he simply spent year after year turning out the beautifully crafted adventures of Donald Duck, Uncle Scrooge, and their associates. He was, it seems, born to make funny-animal comic books.

Mike Barrier is a long-time Barksian. His 1981 Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book is at once a biography, an appreciation, and a catalogue raisonné of this master of precision artwork. The new book fits some of Mike’s earlier arguments into the wider tale of Western and Dell, but he has also deepened his ideas about the nature of Barks’ achievement. He is able to expand his recognition of Barks’ gift for characterization, mood, and emotional expression.

Mike Barrier is a long-time Barksian. His 1981 Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book is at once a biography, an appreciation, and a catalogue raisonné of this master of precision artwork. The new book fits some of Mike’s earlier arguments into the wider tale of Western and Dell, but he has also deepened his ideas about the nature of Barks’ achievement. He is able to expand his recognition of Barks’ gift for characterization, mood, and emotional expression.

Instead of merely recycling an iconic character from the Disney animated shorts, Barks gave Donald his own town, Duckburg, populated by a new cast of characters—Gyro Gearloose, Gladstone Gander, the Beagle Boys, and others. Barks, it seems, gained this creative freedom because everyone at Western admired him. Mike quotes one old timer who calls Barks “the genius of the group. . . . He had a particular affinity with those damn Ducks.” Barks once thought he could support himself raising chickens. Fortunately for us, he turned his poultry fascination to comic books displaying elegant storytelling.

Here’s where Mike set me thinking about some relations between film and comics. He points out that a panel often needs to convey the passage of time—not through movement, as in film, but through devices for suggesting interplay among characters and their environment. The staging of the action, the composition, and the placement of dialogue balloons all create a rhythm of reading. Whereas Japanese manga can split an instant into many single, striking images (and thus create very long books), American comics developed ways to suggest the ripening of the story, moment by moment, within each panel.

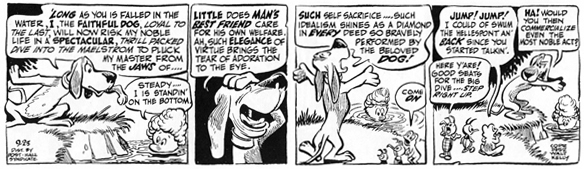

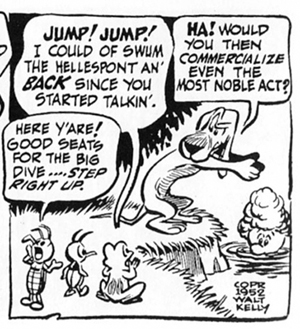

My last Pogo panel featuring the self-aggrandizing hound Beauregard is a good example.

Without the balloons, the image would be a snapshot, but the balloons produce a temporal flow. The most prominent balloon, filling about a quarter of the frame, reports the frog urging Beauregard to jump. The next balloon that we notice, snuggled against the first, shows the bug trying to exploit the rescue (“Step right up”). Farthest right, Beauregard replies to the bug, talking diagonally past the frog. The speeches are the usual Kelly demotic, incorporating low slang, literary references, and pompous rhetoric, and the order in which we read them and attach them to action accentuates the differences in diction.

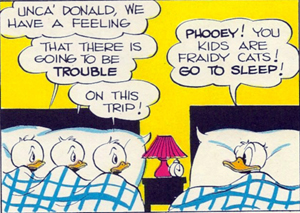

Barks could create this sense of rhythmic duration with his ready-made chorus of Huey, Dewey, and Louie. In this panel from “Frozen Gold” (1944), the cascade of balloons assumes a left-to-right reading and creates a pulse capped by Donald’s brusque reply.

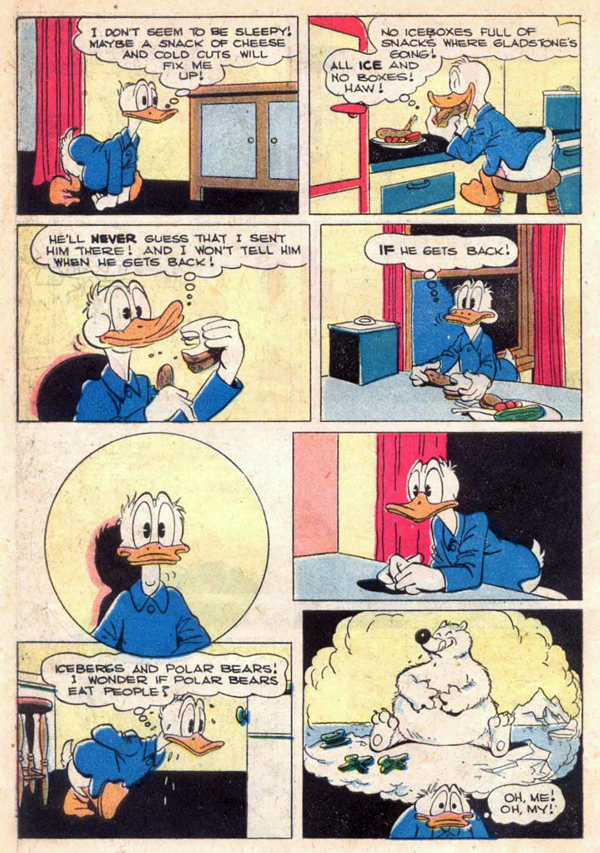

Most panels don’t create such a dense sense of time unfolding. That is more commonly achieved through several panels depicting a stretch of action. Or sometimes inaction. In a wonderful passage, Mike discusses how Barks uses a pause to suggest Donald’s growing guilt feelings after sending the odious Gladstone to the North Pole. At first he gloats, but then in a series of panels he starts to question what he’s done.

Barrier takes this page as a turning point in Barks’s evolution as an artist. Eight panels, some without action, convey a deepening psychological state, capped with an image of Donald crushed by his imagination of what could happen to Gladstone. The sense of food stuck in Donald’s craw is nicely hinted at by two motion lines near his neck.

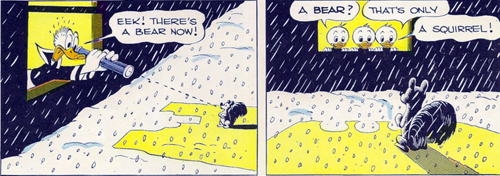

Instead of stretching action by a pause, the artist can accelerate it through ellipsis. Here’s a lovely Barks passage from “Christmas on Bear Mountain” (1947) that’s somewhat filmlike, and yet not. Huey, Dewey, and Louie are checking out a snowstorm and Donald approaches with his telescope. The suggestion is that he approaches their window from off right, with only a few steps until he gets there.

Now comes the first ellipsis: The boys have left the window, and Donald is already spotting what he thinks is a bear. This is very concise storytelling. A sharp change of angle shows another ellipsis: the boys are back at the window identifying the squirrel.

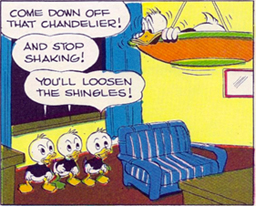

In the “cut” between panels 3 and 4, Donald has disappeared. Where’d he go? The next panel shows us.

The jumps in time are covered by the smoothly varied compositions: 1 and 2, sitting side by side, flow neatly, while 3 and 4, overlapping pictorially, actually cover a time gap. The gap is filled by panel 5, a nice variant on what we saw in 1 and 2. You’d seldom find cuts like these in a film, though I’d welcome somebody trying.

I don’t want to give the impression that Funnybooks is a theoretical study. Mike Barrier, who has thought seriously about the aesthetics and history of comics for fifty years, has given us another precious historical account of this extraordinary popular art and three of its masters. It’s up to us to recognize how his discoveries can shed light on pictorial storytelling generally.

P.S. 28 April 2015: Funnybooks has been nominated for an Eisner Award. Congratulations to Mike! Another fine nominee is Thierry Smolderen’s The Origins of Comics: From William Hogarth to Winsor McCay (University Press of Mississippi), translated by Bart Beaty & Nick Nguyen.

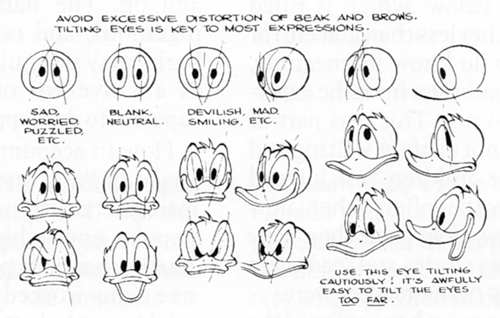

My illustrations are drawn from The Best of Walt Disney Comics 1944 and The Best of Walt Disney Comics 1947 (Western Publishing, n.d.); Walt Kelly, Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics, vol. 2 (Hermes, 2014); Walt Kelly, Pogo: The Complete Syndicated Comic Strips, vol. 2: Bona Fide Balderdash (Fantagraphics, 2012); and Little Lulu Color Special (Dark Horse, 2006). The model sheet of Donald heads comes from Mike Barrier, Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book (M. Lilien, 1981), 43.

Thanks to Hank Luttrell of Twentieth Century Books for helping me find some rare items. And be sure to check Mike Barrier’s encyclopedic website. His 23 April entry rounds up several reviews of Funnybooks.

If anyone reading this doesn’t know Scott McCloud’s superb surveys of the art and craft of comics, I should mention Understanding Comics (Morrow, 1993) and Making Comics (Morrow, 2004). Both books contain many observations on how comics manipulate time.

Looking back at my blog entry on Tintin, I think that the sense of time unfolding within the frame is what Hergé was getting at when he picked a certain image of Captain Haddock as the essence of his method. In the same entry, I suggest that Hergé was creating continuity and ellipses in ways similar to Barks’s Bear Mountain story. Still, Hergé offers more tightly constrained choices of angle and less drastically changing compositions.

The Getting of rhythm: Room at the bottom

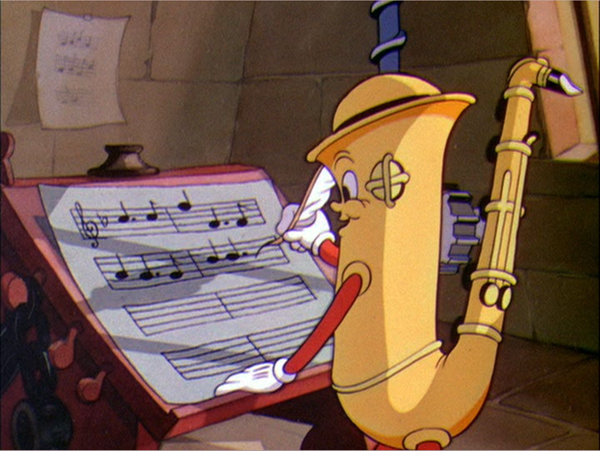

Music Land (Disney, 1935).

DB here:

“The great directors, I’ve learned, have a great sense of rhythm.” So says Alexandre Desplat, who’s again earned two Oscar nominations in the same year (for The Imitation Game and The Grand Budapest Hotel). The statement sounds true but vague. Musicians and musicologists have a firm sense of what the term rhythm means, but how can we understand it in relation to movies?

Well, surely it refers, at least, to the rhythm of the music we hear in the film. But we usually think there’s more involved. There’s rhythm in the movement on the screen. The people and things we see can be infused with a beat and tempo and pace. (Critics of the 1920s considered Chaplin a dancer, like Nijinsky.) There’s a rhythm to the combination of images too, as everybody who’s tried film editing knows. And we think that the story can be told in a way that has a distinctive pace–narrative rhythm, we sometimes call it. But how do these components work together to create an overall rhythm for the film?

When synchronized sound recording entered movies, critics and filmmakers worried a lot about this problem. Filmmakers who had mastered visual storytelling in the silent era had to figure out how to merge spoken language, music, and sound effects with the flow of images. The lazy solution was simply to shoot plays, filling the scenes with dialogue. But both audiences and critics missed the dynamism of silent films. Talkies were too talky.

The opposite solution, to eliminate words as much as possible and simply use music and sound effects, was of limited value. After all, silent film needed the written language of intertitles to make the story clear; why give up the advantages of spoken language? But how then to integrate image and sound into something that engaged the audience–not only through the film’s story but also, perhaps more deeply, through that elusive quality called rhythm?

Today this debate may seem sterile. We think filmmakers have solved the problem. Maybe they have, collectively, but each one faces it at every moment. How do you blend movement, music, pictorial composition, sound effects, and dialogue to create an overall pace that will benefit your movie? No single recipe will work. The rhythm of the Coen brothers’ Raising Arizona is very different from that of No Country for Old Men. Both Gone Girl and Non-Stop are thrillers, but Fincher’s pacing is far more deliberate and understated than Collet-Serra’s; yet both take hold of us.

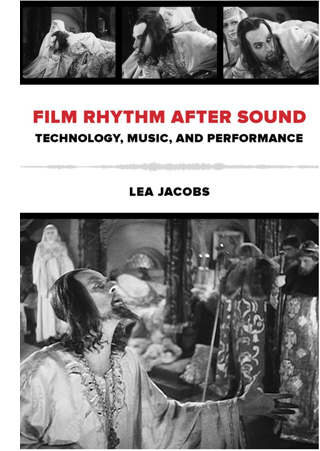

Filmmakers solve the problem of rhythm in practice, often brilliantly. Those of us who want to understand how films work, and work upon us, want to get specific and explicit. What is this thing called cinematic rhythm? What contributes to it? Can we analyze it and explain its grip? Very few scholars have tackled these questions; they’re hard. In her new book, Film Rhythm after Sound: Technology, Music, and Performance, our friend and colleague Lea Jacobs takes us quite a ways toward some answers.

Mickey-mousing redux

Lea starts from the assumption that the debates of the early 1930s are still relevant. So she looks at some much-praised examples of sound/image integration: the musicals of Mamoulian and Lubitsch and the cartoons from the Disney studio. She studies these paradigm cases more closely than anyone has before. She also goes beyond them to consider the theory and practice of Eisenstein (a big admirer of Disney) and the handling of dialogue in Howard Hawks’ work from The Dawn Patrol (1930) to Twentieth Century (1934).

Central to Lea’s inquiry is the notion of synchronization. How can distinct moments in the image flow, the sound flow, and the narrative action be pinched together, like the toothpick pinning the ingredients in a sandwich? One answer is to rehabilitate the old idea of mickey-mousing. Mickey-mousing makes the patterning of the sound match, in some way, the pattern of onscreen action. Mickey-mousing has had a bad press, but Lea shows that if we look at it afresh, it offer a solid point of departure for thinking about rhythm.

Eisenstein develops the idea of sync, in a fresh but still general way, in his notion of “brickwork” structure–the non-coincidence of image and sound, like the staggered array of bricks in a wall. That is, your cut shouldn’t come on the beat (are you listening, music-video directors?). Save your sync until it can have maximum impact, ideally through accenting some action in the image and maybe a high point in your drama. This is a step beyond the duality synchronous/asynchronous sound that was floated in the early 1930s. Eisenstein shows how all the different lines of pictorial and auditory movement can be woven in a flow that will create various degrees of emphasis. In this “wickerwork” pattern (another of his metaphors), actor movement might coincide with a melodic run rather than a beat, and the cut might accentuate a line of dialogue while the music subsides. Or instead of Hollywood’s underscoring, the music might be abnormally loud, doubling and clashing with dialogue in a “Godardian” manner. At certain moments, several accents in these lines could hit simultaneously. Just as important are the moments when the imagery and the mix get thinned out so that a single element–a word, a chord, a gesture–is isolated.

The key example comes from Ivan the Terrible, Part I, in which the ailing tsar asks the Boyars to kiss the cross in allegiance to his baby son Dmitri. In unprecedented detail, Lea tracks how the melody, meter, motifs, orchestration, and dynamics of the music fluctuate in relation to staging, line readings, and narrative developments. In a passage lasting only six minutes, she shows how–as so often happens–Eisenstein’s practice outruns his theory and creates a rich audiovisual texture at an almost microscopic level.

The key example comes from Ivan the Terrible, Part I, in which the ailing tsar asks the Boyars to kiss the cross in allegiance to his baby son Dmitri. In unprecedented detail, Lea tracks how the melody, meter, motifs, orchestration, and dynamics of the music fluctuate in relation to staging, line readings, and narrative developments. In a passage lasting only six minutes, she shows how–as so often happens–Eisenstein’s practice outruns his theory and creates a rich audiovisual texture at an almost microscopic level.

Rhythm is constructed frame to frame, sync point to sync point, and involves very small durations of a half second or a quarter second. This proposition may seem obvious to anyone who has been involved in editing or scoring film music. Classical Hollywood click tracks measured tempi to fractions of a frame, as defined by the sprocket holes, and there are clear indications that composers and editors haggled over durations of five or six frames.

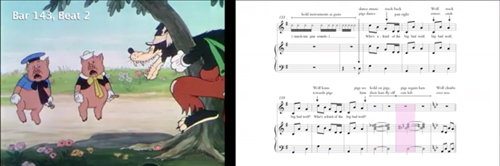

This urge to “think small” and study the finest grain of image and sound carries through Lea’s analysis of rhythm in Disney cartoons. Some have accused Eisenstein’s Ivan of being a live-action cartoon, and there’s no hiding either the old man’s admiration for Disney or his belief that cinema was capable of highly “engineered” effects. Still, music and its mickey-mousing possibilities determine animated films even more strongly than live-action ones. Lea takes Disney’s early sound films as experiments in synchronization.

Early sound cartoons are sometimes characterized as “prisoners of the beat” because they create cycles of motion that are lined up with the musical meter. Lea traces how Disney animation became more fluid and flexible, syncing more around sound events than around rigid beats. She illustrates her case with analyses of Hell’s Bells (1929), The Three Little Pigs (1933), and Playful Pluto (1934). The last two are widely regarded as classic Silly Symphonies, and she sheds fresh light on them through the sort of micro-analysis brought to bear on Ivan.

She shows how sections gain a fast or slow tempo through the interaction of many factors, of which shot length is only one. In particular, Disney directors could change pace through a tool that Eisenstein didn’t have: altering the frame rate of animation. Normal animation is “on twos”; each drawn frame is photographed twice, to last for two film frames. Many stretches of the Disney cartoons are on twos, but sometimes, to create vivid sync points, the filmmakers go “on ones,” allotting one frame for each drawing. This is more expensive and time-consuming, but it allows for the sort of fine control of pace that we find in The Three Little Pigs. There the Wolf launches into “a jazzy, up-tempo gallop” that accelerates the danger bearing down on the pigs. In a similar way, Playful Pluto creates variety by “matching movement to different fractions of the beat and establishing differential rates of movement within the shot.” Imagineering, for sure.

How to convey this fine-grained analysis on the page? Lea uses the familiar tactics of presentation: verbal description, musical scores, and frame enlargements. But she goes farther. At great effort and expense, she has constructed analyses of key passages as video clips, with the film scene running in interlock with a highlighting bar that shifts across the score. Annotations on the score mark actions and sync points. These analyses are designed to be watched as you read along in the book. You’ll see some frame grabs in this entry, but to watch them simply go here, select the Audio/Video tab, and choose what you want to see from the menu. This is a real step forward for film scholarship, and the University of California Press should be congratulated for helping her take it. Why shouldn’t every film book hereafter come garlanded with clips?

No age for rhythm

Monte Carlo (1930).

Okay, you might say. Rhythm is of concern to top-down audiovisual masters like Eisenstein and Disney. But there are other notions of film as art–for instance, that performance is central to its storytelling. Lea shows that, again, early sound film explored a more open and porous integration of music and image. Ernst Lubitsch, as Kristin has shown, was one of the masters of image-based cinema in the silent era. Yet as soon as sound came in, he was exploring how to blend music with the mercurial repartee and attitudes of his sophisticated characters. Rouben Mamoulian, who had indulged in sync experiments in the theatre, contributed as well to a broader trend that gave music a central role in structuring scenes.

The result wasn’t exactly “musicals” as we usually understand them, although there might be song numbers; instead, the music worked its way into the crannies of the scenes–pauses in the dialogue, moments when characters cross a courtyard or boudoir. Thanks to post-synchronization (music performed after the film was shot and cut) and sync-to-playback (prerecorded music played on the set during performance), early sound films could boast a tight rhythmic bond of performance style and musical accompaniment. That created a sort of cinematic operetta, one no longer bound to a theatrical space. In “Isn’t It Romantic?” in Mamoulian’s Love Me Tonight (1932), a song begun in a tailor’s shop is passed along through Paris, onto a train, to the open road (soldiers march to it), and eventually to a gypsy campfire, where the heroine hears it from her balcony.

Most historians find strong similarities between such passages in Love Me Tonight and scenes in Lubitsch’s Monte Carlo (1930), but Lea contrasts them. She argues that Mamoulian’s film is more like early Disney in syncing music one-to-one with figure movement and camera movement. Lubitsch (although working earlier than Mamoulian) is interested in synchronization at another level, linking musical segments to dramatically coherent parts and wholes. She shows how one sequence in Monte Carlo accelerates its techniques to culminate in a patter song, creating a curve of rhythmic interest that sculpts the scene’s overall shape. Significantly, as in the famous choo-choo “Beyond the Blue Horizon” number, the song uses noises rather than music to launch its rhythmic arc.

The case-study method leads Lea to some generalizations too, as in her survey of manners of dialogue underscoring. This section of the books seems to me especially rich, because it shows how tactics of underscoring associated with the 1930s “symphonic” scores were already available, at least sketchily, in the early years of sound. At the same time, she’s able to distinguish some creative options, such as the conversion of patter songs to a more conversational tempo, that seem very distinctive of these early sound films and not their successors. She and other scholars can now build upon her survey to track a variety of styles of dialogue underscoring.

Okay, again, but these early musicals are still very pre-structured, you might say. What about movies that don’t rely on music so much and that give the actors more freedom during shooting?

Okay, again, but these early musicals are still very pre-structured, you might say. What about movies that don’t rely on music so much and that give the actors more freedom during shooting?

Enter Howard Hawks.

The book’s last in-depth analysis is devoted to probably the trickiest aspect of the whole problem: rhythm in speech, performance, and narrative. Lea points out that sound film acting required quite exact timing of pauses, glances, gestures, movement around the set, and deployment of hand props–probably tighter timing than in the silent era, with its shorter takes and greater scene dissection. (Consider how often a silent film gives us a close-up of a hand picking up something; in talkies, picking up something seldom gets that emphasis, so that the actor has to integrate the action into the flow of the full shot.) In sound filming, the shooting of the scene and the actor’s performance choices limited what an editor could do to slow it down or speed it up.

Hawks is a notoriously difficult director to analyze because he doesn’t have an obvious signature style at the visual level. His conception of cinematic art relied upon his players. He famously developed his scenes slowly, letting actors improvise, asking screenwriters to recast the scene, and working out the blocking gradually. In this actor-centered cinema, we’re often told, a lot of the Hawksian tang comes from overlapping dialogue. Lea points out, though, that overlapping dialogue was already in wide use on the theatre stage and Hawks was comparatively late in importing it to film. His earliest 1930s experiments don’t owe much to it, largely because early sound technology couldn’t discriminate voices very well. Lea breaks new ground in showing other ways in which speech patterns, regulated through rhythm as well as pitch and timbre, not only contribute to characterization but supply that zesty bounce we associate with the Hawksian world.

His tactics include shifting actors around the set, letting background and foreground sound alternate in clarity, and shortening scenes. Lea goes on to show how these and other options led Hawks to create the “tough talk delivered in a tough way” that became one of his hallmarks. By measuring the length of actors’ lines in seconds and fractions of a second, she’s able to track a subtle orchestration of voices–long speeches delivered fast (or slow), short speeches delivered slow (or fast), and many varieties in between, all interwoven. Overlapping comes in occasionally, as icing on the cake. When it does, especially in Twentieth Century, Lea is ready to specify it, showing how syllables and phonemes are stepped on or cut off.

Now the control freaks aren’t the directors, the Eisensteins and Lubitsches, but the actors. Working together, they plan their lines, expressions, and gestures down to the word. They make their own music. Hawks, says Lea, gives us rhythm “without benefit of a beat.”

Film Rhythm after Sound is a breakthrough in showing how narrative cinema masters time in its finest grain. We’re used to talking about scenes, shots, and lines of dialogue. Lea has taken us into the nano-worlds of a film: frames and parts of frames, fractions of seconds, phonemes. As Richard Feynman once said of atomic particles, “There’s plenty of room at the bottom.” Of course Lea doesn’t overlook characterization, plot dynamics, themes, and other familiar furniture of criticism. But she shows how our moment-by-moment experience depends on the sensuous particulars that escape our notice as the movie whisks past us. We can’t detect these micro-stylistics on the fly. Yet they are there, working on us, powerfully engaging our senses. Film criticism, informed by historical research, seldom attains this book’s level of delicacy. Analyzing a movie’s soundtrack will not be the same again.

The World comes to Vancouver

The Golden Era.

Kristin here:

One of the great pleasures of the Vancouver International Film Festival is the ability it provides for a quick trip around the world, especially to countries whose films are seldom seen in a non-festival setting.

In one day I was able to see an Algerian film and one from the Ivory Coast. It struck me that both of them reflected how far digital filmmaking has come in small producing countries. When digital cameras came on the scene, they were hailed as a way for people in nations with little or no filmmaking infrastructure to create movies. The results, fascinating though they might be, often betrayed visually the fact that they were made with non-professional cameras.

Perhaps we have reached a new stage in digital filmmaking in such countries. Both the Algerian film, The Rooftops (Merzak Allouache, 2013), and the Ivory Coast one, Run (Philippe Lacôte, 2014), have a polish and complexity of form and style that put them on a level with those made in larger, more established national cinemas.

The Rooftops provides a model of how to make a film with a limited budget and avoid conventionality. Allouache chose to set the film entirely on the rooftops of five districts of Algiers. It’s a gimmick of sorts, and yet it carries practical advantages. No sets had to be built, and few, if any scenes required artificial light. Presumably no streets had to be cleared, since no action is staged at ground-level.

Beyond that, each scene could be played out with the city of Algiers providing a backdrop, as when a group of young musicians practice on one of the rooftops:

With backgrounds like that, who needs sets?

The film has a strict formal logic, both spatially and temporally. It begins by introducing five rooftops, each with its own set of characters. There’s no crossover among the groups. None of them ever meet, so this isn’t what David has termed a network narrative. But the look of each rooftop is different, and simply by keeping the characters in one limited area, the filmmakers help us keep track of them fairly easily as the narrative moves among storylines.

The film starts with the first call to prayer in the darkness before dawn, and at intervals the four other calls follow (with a subtitle providing information on the name of each call and the time period within which the respective prayers are supposed to be performed.) These essentially act as chapter breaks, giving a sense of time passing. The five prayers also echo the five rooftops.

There’s no shortage of drama in each group’s story. On a lower floor of an unfinished building a mob boss has a man tortured, trying to force him to sign something. This disturbs a group of filmmakers taking shots from the roof above, with dire consequences. A landlord is murdered on another rooftop, and a suicide occurs on yet another. One gets a cumulative impression of crime and conflict being rife across these various districts of Algiers.

Allouache is considered the preeminent Algierian director, and the violence and strife depicted rather melodramatically are part of his ongoing critique of his nation’s social problems.

In contrast, Lacôte sets Run apart by adopting a classic flashback structure. The film opens with the crisis of the story: the hero, nicknamed “Run,” shoots the prime minister in a crowded auditorium and flees.

From then on, we see him in hiding as he reflects on how he became an assassin. The alternation of scenes from his youth and his current-day attempts to avoid capture are easily comprehensible. Lacôste finds ways to create visual interest and avoid conventional stagings of scenes, as in the low angle above that juxtaposes the hero with a looming, crisscrossing ceiling.

Another example comes when his friend gives him shelter and food. Rather than a simple shot/reverse-shot conversation across a table, we see a depth scene, with Run sitting on the floor to eat and his friend in the foreground twisting to talk with him:

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, the notion was that people in underdeveloped countries could gain small cameras and discover their own ways of making films, free of Hollywood conventions. To some extent that happened. But with the globilization of mass media, few people, however isolated, can remain unaware of Western culture.

Presumably some filmmakers have aspired to match the technical standards of Western offerings in international film festivals. These two films show them succeeding, having thoroughly grasped the conventions of both art films and popular genres. We ‘ll discuss an example of the latter in an upcoming entry on Middle-eastern films at VIFF, and in particular the Iranian vampire film, Girl Walks Home Alone at Night.

Ann Hui’s quiet epic

Ann Hui’s career is usually associated with intimate films, mostly studies of character. We saw her at Ebertfest earlier this year, where she presented A Simple Life, the epitome of such films.

Now she has surprised audiences with another character study, but one set in a tumultuous period of Chinese history, the late 1930s and early 1940s. The Golden Era (2014) tells the story of female writer Xiao Hong, who died young in 1942. Not all the facts of Xiao Hong’s life are known, and the narrative sketches scenes derived from the author’s own writings. Interspersed are “documentary” shots of interviews with people (played by actors) who knew and worked with Xiao Hong.

Much of the tale consists of small-scale scenes, conversations among a few people set indoors or in the streets. Yet as the Japanese invasion begins and spreads, occasional big scenes occur, and Hui proves herself perfectly capable of suggesting creating a sense of epic events.

The war is only fleetingly present, however. We see it mainly from the viewpoint of the main characters, as when a quiet indoor conversation scenes are abruptly and startlingly cut short by bombs going off outside and shattering windows.

The film’s settings and costumes create a vivid sense of the era. There are street scenes in Hong Kong shortly before its fall to the Japanese that appear almost documentary in their realism. Throughout the images are beautiful, as the frame at the top of the entry demonstrates.

The film’s three-hour running length adds to the epic feel, tracing the heroine’s changing fortunes across momentous historical events. It makes a striking contrast with A Simple Life, and yet Hui’s concern with precision and detail in delineating characters remains constant. The pair might bring her back to the sort of prominence outside Hong Kong that she enjoyed in the 1980s and early 1990s. Indeed, The Golden Era was just presented as the gala film at the Busan Film Festival.

Another farewell from a Ghibli master

Just over a year ago Miyazaki Hayao announced that he would retire, having completed and released his final film, The Wind Rises (2013). Speculation over the fate of Studio Ghibli, the animation studio that he co-founded, followed.

Now we have the reported final film of a second of the three original founders, Takahata Isao, whose most famous film is Grave of the Fireflies (1988). Like The Wind Rises, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2014) lets its director go out on a high note.

Based on a tenth-century fairy tale, Princess Kaguya has a distinctive style, with most scenes done in translucent watercolors in pastel shades, quite different from the solid, vivid colors of much of Miyazaki’s work. It tells its story in a leisurely fashion, running 137 minutes, which may be a bit challenging for younger children, but it is never boring.

Kaguya is not necessarily a princess. We’re not sure what she is. She appears miraculously one day as a tiny baby in a glowing bamboo shoot. She is iscovered by a bamboo-cutter who assumes she is a princess and insists on calling her that. The bamboo-cutter and his wife raise her in a forest cottage (seen below). The opening section is idyllic, with the tiny girl growing unnaturally fast, in spurts. She is befriended by neighboring children, and the group explores the surrounding countryside, reveling in the beauty of the plants and animals they observe there.

Spurred by another miraculous discovery, this time of gold nuggets inside a bamboo stalk, the bamboo-cutter decides to build a mansion in a nearby city and make Naguya into a real princess by marrying her off to royalty. There ensues the classic competition among suitors to find the most fabulous object and present it to Naguya.

Naturally Naguya longs for the countryside and finally rebels. In a remarkably stylized, exciting scene that contrasts with the rest of the film, she races toward her forest home, and the pastel settings disappear. She becomes a blur of black, white, and red flashing through a gloomy landscape with sketchily drawn trees and plants that flicker wildly past:

The Tale of Princess Taguya has been announced for an October 17 release in the USA, distributed by GKids. Unfortunately it will only be available in a dubbed version. Even dubbed, it’s worth seeing on the big screen, but with luck there will be an option for the original Japanese-language version with subtitles on the DVD/BD release.

Studio Ghibli has released another film, The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, a documentary about the studio by Sunada Mami. (It played at Toronto but is not here at VIFF.) Its appearance seems to hint that Ghibli really is going to cease feature production, though the official story is that it is only pausing. It has been a prolific producer of short animated films, and perhaps that side of its activities will continue. For a good summary of the situation and a description of the documentary, see here.

The Tale of Princess Taguya

Prague summer

The Ascension of Christ, panel from the Vyšši Brod Altarpiece, ca. 1350. Convent of St. Agnes, Prague.

DB here:

Kristin and I are in Prague for about a week, in connection with two lectures I’m giving Wednesday and Thursday.

In the meantime, we’ve met with friends. After we arrived we had a lively dinner with Radomir Kokes, specialist in Czech silent film. Last night we met with Petra Dominková and Vaclav Kofron, translators of the Czech editions of Film Art and Film History, and Michal Bregant, head of the National Film Archive (and who also contributed to the translation of Film History). During that enjoyable evening we learned, among other things,that film lovers of Michal’s generation took the train to Hungary to see American films that didn’t make their way into their country.

Later, meeting with Radomir and our principal host Lucie Česálková , we learned of their robust, long-lived journal Iluminace, which publishes film research in both Czech and English. The most recent issue is devoted to studies of film festivals.

So far we’ve spent the rest of our time visiting museums. Prague is bursting with rich collections of European art from all eras. Today (Tuesday) we went to one of the major venues, the Convent of St. Agnes, which houses a vast array of Bohemian medieval and early Renaissance painting and sculpture.

There were plenty of images to give us pleasure. One of the most spectacular set of items was a series of fourteenth-century altar panels representing the life of Jesus. Each one gave what seemed to me a fresh interpretation of the major episodes–annunciation, nativity, etc.–but especially striking was the one devoted to the Ascension. After being resurrected, Jesus is lifted to heaven; but contrary to what we usually see, the action is represented “offscreen.” All we see are Jesus’ feet, as above. A nice touch Kristin noticed: He left his footprints in the earth.

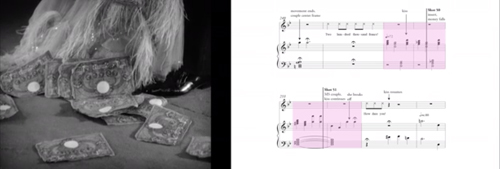

I’m drawn to such peculiar treatments of conventional material. There were some other instances in other Prague galleries. Take this piercing image of the mockery of Jesus, in an unidentified Netherlandish painting from the first half of the sixteenth century. The torturers are blowing a cowhorn at Christ, banging a pot, pressing a stool against his head, thrusting a rod into his mouth, and spraying him with a flit gun.

Most remarkably, at the bottom of the composition one man fills a basin with what seems to be shit, while another man dips a cloth in it, as if preparing to apply it to Christ’s face. The suggestion is reinforced by the wizened man on the far right holding his nose.

Such visceral images remind you that holy pictures can be pretty ornery. They also remind you of Jan Švankmajer, that great Czech animator. So far, there’s no museum dedicated to him, but following Petra’s suggestion we did visit the Karel Zeman Museum, just off the Charles Bridge. It offers enjoyable attractions tracing Zeman’s career, with emphasis on Journey to the Beginning of Time (1955) and The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958). Kristin hopes to write at greater length about the museum and Zeman later this summer.

Tomorrow: Off to the world-renowned archive to watch Czech silent films. Who knows what we’ll find?

Thanks to Lucie Česálková and all her colleagues for making our visit possible. Thanks also to Michal Bregant for a correction in the original posting of this entry.

Kristin and I wrote about Švankmajer’s remarkable Dimensions of Dialogue (1982) in the latest edition of Film Art. At the Zeman Museum we discovered a beautiful 2013 book on the filmmaker, available here.

DB at the porthole of Nemo’s Nautilus in the Zeman Museum.