Archive for the 'Animation' Category

That reminds me …

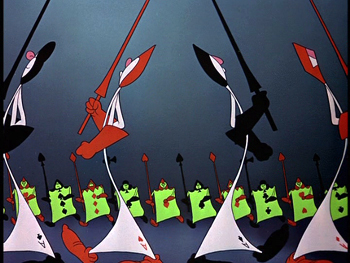

Enter the Frog Footman in Alice

Kristin here:

One film I can’t work up much enthusiasm about is everywhere, and another I very much want to see doesn’t seem to have a North American distributor. Luckily each reminds me of an older film that isn’t widely enough known. This seems like the perfect chance to point them out.

Recently the latest Screen International, in its new monthly format, arrived, with literally back-to-back reviews of the two films: Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland and Sylvain Chomet’s The Illusionist.

Let me say first off that Johnny Depp looks great in eyeliner, as in Pirates of the Caribbean. He looks positively grotesque with pink lips and raccoon eyes. Of course, grotesque could work well for Alice, especially as adapted by Burton. Yet the reviews suggest that the film is actually tamer than one would expect. Screen International’s Brent Simon calls Burton’s film: “A gorgeously mounted but fundamentally humdrum telling of Lewis Carroll’s fantasy novels” (March 2010 issue, p. 61). Variety’s Todd McCarthy makes a similar remark: “But for all its clever design, beguiling creatures and witty actors, the picture feels far more conventional than it should; it’s a Disney film illustrated by Burton, rather than a Burton film that happens to be released by Disney.”

Back in 1951 Disney did a fine version of Alice in Wonderland, one which does capture something of the lunacy of the original. It also benefited from the talent of some of the studios’ best artists, including Mary Blair. Always worth going back to.

But if one wants a truly surrealist, unconventional adaptation, I doubt if anything can top Jan Švankmajer’s feature Něco z Alenky, aka Alice. David and I saw it in a theater when it was released in the U.S. in 1988. It was my first exposure to the great Czech surrealist animator, and we gradually caught up with his earlier films. At the time it had a considerable success on the art-cinema circuit, though I’m not sure how well known it is among younger film fans.

Švankmajer had used both live-action, as in his morbid documentary The Ossuary (1970), and stop-motion animation of objects, as in his brilliant, dark look at human relations, Dimensions of Dialogue (1982). DVD anthologies of his shorts are available. Kino Video’s “The Collected Shorts” volume isn’t as complete as its name may imply. It’s missing several films including The Last Trick, his first but far from least film, and what may be his very best, Jabberwocky (1971), a non-narrative short incorporating Carroll themes. If you’ve got a Region 2 or multi-standard player, opt instead for “Jan Švankmajer: The Complete Short Films,” from the British Film Institute. It has a third disc with extras.

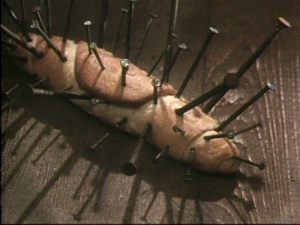

Alice is suffused with a marvelous imagination. Many of the characters are museum specimens. The White Rabbit begins as a stuffed creature in a Victorian glass case, freeing himself by pulling up the nails that keep him rigidly posed. Breadrolls sprout quills made of nails, and unnatural skeletons of creatures straight out of a Bosch painting creep about.

Švankmajer takes advantage of the mingling of two-dimensional figures based on playing cards and three-dimensional figures in ways that few adapters of Alice in Wonderland have managed, as when the White Rabbit passes the Queen of Hearts in a stage setting built of painted flats:

The Mad Hatter in Švankmajer’s film is definitely not Johnny Depp. He’s an antique wooden puppet of the sort that often crops up in the filmmaker’s work. He’s also not as loquacious as the chap in the book. The March Hare, who is definitely mad, steals the scene from him. Buttering a watch’s innards is a pure Švankmajerian gesture.

Alice was Švankmajer’s first feature film. In it he mixed live-action in with the stop-action more than in most of his shorts, presumably in part as a way to save money in making a much longer film. When Alice is full-size, she is played by a real girl, but when she shrinks she becomes a pixilated doll. It works well in this case, but the filmmaker depended more and more on live-action in his later features, like Faust (1994), with animated interludes becoming rarer and rarer. I found these features less entertaining and original and more heavy-handed in their social commentary. (The shorts contained vicious satire, but it was often rendered in bizarre, striking ways that made it palatable.) After thoroughly disliking Conspirators of Pleasure (1996), I gave up on his new films and stuck with the old ones. He’s making one now, called Surviving Life, which he apparently has said will be his last.

A final word on Alice. As should be obvious, this isn’t your charming adaptation for children, at least small ones. Alice points that out during the credits, “Now you will see a film made for children. Perhaps.” Most kids these days seem to be more hard-boiled than in my youth, but seeing this film at age 10 would have left me with nightmares. The White Rabbit, scarier than any fuzzy little bunny I’ve ever seen (including the one in Monty Python and the Holy Grail), runs around with scissors, quite willing to obey the Queen of Hearts’s order, “Off with her head!”; the little skeleton creatures crawl over Alice; and creepy glass eyes give staring life to inanimate objects like the Frog Footman or the sock that turns into the Caterpillar:

They tend to stare right out at us, too.

Tati on Parade

Most readers of this blog will be familiar with the great Jacques Tati. But it was news to me that he had left an unproduced screenplay, finished in the 1950s and now adapted by French animator Sylvain Chomet. Those who saw Chomet’s first feature, the 2D animated film The Triplets of Belleville (2003), probably noticed the occasional Tati homage lurking in the backgrounds and on the walls. Now Chomet’s admiration for Tati has emerged front and center in his second animated feature. The Illusionist‘s protagonist is modeled directly on Tati; he’s a old-fashioned magician eking out a living in the fading world of music-halls. (The Russian trailer has been posted here; apparently that’s the only footage on the internet so far.)

The Illusionist premiered at the Berlin Film Festival this year and met with a warm reception from critics. Writing in Screen International, Lisa Nesselson calls it “a delightfully bittersweet valentine to the music-hall tradition” and says that its animation “simply could not be better” (March, 2010 issue, p. 62). Leslie Felperin’s Variety reviews dubs it “a very happy marriage of Tati’s and Chomet’s distinctive artistic sensibilities.”

While we are waiting for an American distributor to pick up the film (ahem!), let me recommend Tati’s least-known feature. After his financial difficulties in the wake of Play Time‘s high budget and tepid box-office performance, the director set out to make Traffic, his last film featuring his M. Hulot character. Funding on this film collapsed midway through shooting, but Swedish TV stepped in and bailed the production out. Traffic came out in 1971, and in exchange for the assistance Tati made the 85-minute telefilm Parade (1974).

It has been available on French DVD (now out of print), but now the British Film Institute has released its own edition. The transfer isn’t the greatest, though it seems to be the same or similar to the French version. It smooths over the peculiarities of the original film. David and I saw it in 35mm in Brussels (where we also saw The Triplets of Belleville). It was obvious that while most of the film had been shot on somewhat fuzzy video in front of a live audience, some acts had been staged in a studio on crystal-clear 35mm. It was an oddly mixed format for an odd film. The BFI version also features optional English subtitles. Given the paucity of audible speech, they don’t seem vital.

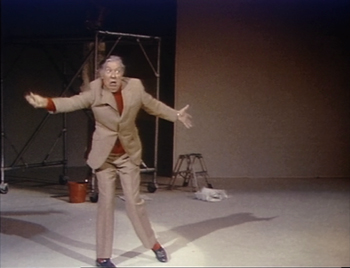

After the audience files in and takes their seats and an opening parade introduces the main acts, Tati steps forward as emcee and informs the spectators that they will be as much a part of the show as the performers onstage. Sure enough, the audience has been staged by Tati, accoutered in outrageous, colorful outfits and instructed to turn their heads back and forth rhythmically during his tennis routine or to bounce balloons around. Occasionally “ordinary” people from the stands step forward to challenge the acts onstage, trying and sometimes succeeding in out-doing them in magic or musical performances. The black-and-white life-size cutout people that had been used as extras in the backgrounds of scenes in Play Time return here as prominent members of the audience and even the stage acts. In the scene of Tati’s mime of a goalie (see below), the cutouts provide an unmoving backdrop to the action.

After the audience files in and takes their seats and an opening parade introduces the main acts, Tati steps forward as emcee and informs the spectators that they will be as much a part of the show as the performers onstage. Sure enough, the audience has been staged by Tati, accoutered in outrageous, colorful outfits and instructed to turn their heads back and forth rhythmically during his tennis routine or to bounce balloons around. Occasionally “ordinary” people from the stands step forward to challenge the acts onstage, trying and sometimes succeeding in out-doing them in magic or musical performances. The black-and-white life-size cutout people that had been used as extras in the backgrounds of scenes in Play Time return here as prominent members of the audience and even the stage acts. In the scene of Tati’s mime of a goalie (see below), the cutouts provide an unmoving backdrop to the action.

The BFI DVD includes a brief but informative booklet with essays by Philip Kemp and Jonathan Rosenbaum. As Kemp  points out, the acts out of which Tati built his film are, apart from himself, not much to boast about: “His colleagues’ juggling, acrobatics, and, literally, horseplay (much use is made of an upright piano that doubles as a vaulting-horse) are diverting but nothing special.” Yet that, I suspect, is part of the underlying strategy. The film is quite Tatiesque, despite its lack of M. Hulot or a real plot. The juxtaposition of the three separate spaces of the audience, the stage, and the carpenters’ shop directly abutting the performance space, allows the creation of the sort of visual jokes that Tati loves. It also permits a flow between roles, as when the “carpenters” emerge briefly to juggle with their brushes or to play their tools like xylophones before returning to work. All these performers are quite good, but really great acts would distract from the best act of all: Tati’s overflowing visual imagination.

points out, the acts out of which Tati built his film are, apart from himself, not much to boast about: “His colleagues’ juggling, acrobatics, and, literally, horseplay (much use is made of an upright piano that doubles as a vaulting-horse) are diverting but nothing special.” Yet that, I suspect, is part of the underlying strategy. The film is quite Tatiesque, despite its lack of M. Hulot or a real plot. The juxtaposition of the three separate spaces of the audience, the stage, and the carpenters’ shop directly abutting the performance space, allows the creation of the sort of visual jokes that Tati loves. It also permits a flow between roles, as when the “carpenters” emerge briefly to juggle with their brushes or to play their tools like xylophones before returning to work. All these performers are quite good, but really great acts would distract from the best act of all: Tati’s overflowing visual imagination.

Ultimately, though, the main boon of Parade was to preserve for posterity Tati’s famous series of sport-based pantomimes that he had developed in the 1930s, when he was a successful stage performer. He started off on the same music-hall stage that he celebrates in Parade and now, posthumously, in The Illusionist. Some of these mimes, such as the man-and-horse trick rider, the over-confident goalie, the over-the-hill boxer, or the disappointed fisherman (bottom) may have remained unchanged across Tati’s career. (After he became famous as a filmmaker and actor, he often had the chance to perform these brief skits on TV variety and talk shows.)

Horse-man

Goalie

Boxer between rounds

Tennis in slow motion

There’s one magic moment in these mimes, however, that Tati presumably updated. During the tennis match, he lapses briefly into slow motion. Not a slow motion achieved in the camera, which keeps running at normal speed. No, he mimes a player as seen in slow motion, quite convincingly and yet moving in ways that one wouldn’t consider possible for the human body. It’s hard to describe, but believe me, it’s amazing to watch.

Tati’s performances as the postman in Jour de fête or as Hulot in the four films featuring that character are usually not flashy. They’re designed to merge into the story and make the hero one of many amusing characters in an ensemble. But in Parade, with the pantomimes performed outside a narrative context and primarily against dark or blank white backgrounds, we can savor the man’s dazzling skill. His utter control of every gesture echoes his directorial mastery of every stylistic component of his films. In Parade, the moments when he tries to subdue a flapping fish before it escapes or when his head snaps back in reaction to an imaginary opponents’ blows are mindboggling in their precision. He was a great actor before he was a great filmmaker, and fortunately that early skill lingered long enough to be recorded.

Gone fishing

Motion-capturing an Oscar

Kristin here:

Six years ago, when The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King was nominated for eleven Oscars, there was considerable grumbling over the fact that Andy Serkis was absent from the acting categories. Many argued that his pivotal role in creating Gollum, the first convincing human-like computer-generated character, should have qualified him for a nomination.

Now we’re seeing a similar debate over the lack of actor nominations for Avatar, with Zoe Saldana’s performance as Neytiri especially mentioned as unfairly overlooked. An intriguing article on the subject appeared in the Los Angeles Times a few days ago. In it, James Cameron expresses annoyance with both the Screen Actors Guild and the Academy for the lack of nominations for his actors:

I’m not interested in being an animator. . . . That’s what Pixar does. What I do is talk to actors. ‘Here’s a scene. Let’s see what you can come up with,’ and when I walk away at the end of the day, it’s done in my mind. In the actor’s mind, it’s done. There may be a whole team of animators to make sure what we’ve done is preserved, but that’s their problem. Their job is to use the actor’s performance as an absolute template without variance for what comes out the other end.

Because of innovations in the motion-capture process, including a tiny camera hung in front of an actor’s face to capture its every nuance, Cameron insists on calling the new technology “performance capture.” In some sense it may be true that the performance is preserved, but once the film runs through the theater projector, can the audience really tell what that “template” was like? I think not, and that’s why there is a reluctance to nominate these actors.

Where is the elusive boundary?

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying that Zoe Saldana and Andy Serkis aren’t fine performers or that their acting did not contribute enormously to the characters they played. Indeed, Serkis’ mo-cap contribution to the creation of Gollum was originally intended to be far more limited than it turned out to be. His facial expressions and gestures were so useful to the special-effects people that he was involved for a much longer period, and techniques to allow him to perform onset with the other actors were developed.

But however fine the original acting and however great the aid it provides to the special-effects team are, the process doesn’t stop there. To a notable degree other factors intervene between the actors’ original performances and the characters’ final appearance on the screen. Let’s do some comparisons, using the publicity images that the studios themselves considered good indications of how close the expressions of original actors were to those of their characters.

Take the widely circulated image of Saldana juxtaposed with Neytiri shown above. There are numerous differences. For a start, the filmmakers obviously needed to make the Na’vi look like an alien species. They didn’t just give them tails and make them blue and really tall. Human as the creatures seem in many ways, their faces have a subtle suggestion of large felines.

The effectiveness of Neytiri’s snarl has a lot to do with the fact that she has been given exaggeratedly long canine teeth. Moreover, given the changes in the shape of the face, the mouth is not as large proportionately to the entire head as Saldana’s is; the tongue is not nearly as prominent or noticeable. Both tongue and lips are blue as well. All of these features allow the teeth stand out more by contrast.

Na’vi ears are pointed, and some of the lobes are apparently pierced with a small dark disk in the hole. Saldana’s ears played no role in her performance, but the laid-back ears in the Neytiri image, mimicking those of an enraged animal, contribute considerably to the shot’s impact. I remember noticing them while watching the film.

The nose and the wrinkles on and above it have been considerably changed. Unlike human noses, those of the Na’vi are smaller at the bottom than at the top, somewhat resembling lions’ noses. The wrinkles seem to be derived from canine or feline faces as well, extending from the inner end of the eye and arcing down toward the tip of the nose. The human frown lines at the lower center of Saldana’s forehead are transformed into larger, longer, curved wrinkles at either side; these start between the eyebrows and move up and to the sides. There they get extended by the curved areas of darker blue that radiate across the upper forehead, so that the lines of anger seem to cover more of the face. I suspect that relatively little of what the actors did with their noses has survived the special-effects processing. (In the image below, even the shape of Saldana’s naso-labial folds has been slightly altered.)

The change in the eyes is particularly important. Saldana’s eyes have dark irises within which the pupil is barely, if at all, visible. Na’vi eyes are much larger, to begin with, and the irises are light in color, a sort of yellowish tan. The irises fill more of the visible part of the eye, so that the whites of Na’vi eyes are minimized. As a result, the black pupil stands out dramatically. In terms of color, the model seems to be cats’ eyes, though the pupils remain round rather than slits, to avoid making the Na’vi too alien looking. Since the nose has been widened at the top, the eyes are also further apart than on human faces. (The norm with humans is for the eyes to be separated by a distance roughly equal to the width of one eye.)

Even in a less dramatic scene, when Neytiri is relaxed and smiling, some of these differences remain. The pointed ear is not laid back, but it sticks out from the side of the head at an angle that draws the spectator’s attention and makes the human-shaped face seem exotic–especially given that the Na’vis’ ears are placed higher on the skull than human ears are: while the human ear canal is about even with the cheekbone, in the Na’vi it opens at mid-temple level. Although the points of the canine teeth are not visible in this image, the teeth remain prominent because of their bright whiteness against the blue skin. Though partially masked by the headgear, the vaguely feline nose still differs considerably from Saldana’s. In keeping with the extraordinary height of these beings, Saldana’s neck has also been lengthened.

Again, I’m not saying that Saldana and the other actors in Avatar did not contribute enormously to the believability of their characters or that they did not aid us to empathize with them. On the contrary, although the big blue creatures did seem very odd in the trailers and posters, I have to admit that they quickly came to seem like real characters. Their design’s balance of human and alien is remarkable. I did not continually think of them as walking combinations of numerous elaborate special effects. The new facial-capture system renders expressions very well, as the frame at the bottom shows.

What I’ve pointed out here with relation to Saldana’s contributions to the creation of Neytiri applies as well to Serkis’ earlier contributions to Gollum. In the comparison images below, similar changes were made.

While Serkis’ ears were covered, Gollum’s are pointed and prominent. Here, too, the eyes have been enlarged and made a light blue so that the pupils stand out. Where the actor’s teeth are straight and even, Gollum’s are pointed, crooked, and separated by gaps. The cheeks have been hollowed and the eyebrows arched nearly to a point near their outer ends. Crucially, the body has been made inhumanly skinny, with long bony legs and arms that are not apparent in this image. I suspect that some naive audience members believed that a real actor had played Gollum, but to most the scrawny figure was a guarantee that no human could have performed the role. (The very thin waists of the extraterrestrials in District 9 served as a similar guarantee that these were not just guys in monster suits à la Invaders from Mars.)

With all the kinds of changes that I’ve pointed out, how would Academy members be supposed to judge these performances were they to be nominated in the traditional acting categories? Where is the boundary between acting and special effects? Despite actors’ and directors’ claims to the contrary, the movements and expressions caught by performance capture are changed in many obvious and not so obvious ways. A close inspection of the comparison photos reveals the details of the transformation, but in watching the film, the viewer cannot necessarily gauge what sorts of changes were made. I can well imagine that actors like Meryl Streep or Jeff Bridges would be justified if they objected to competing in the same Oscar category as what are essentially hybrid performances seamlessly combining the original acting and the digital transformation.

Possible new categories

One way I can imagine actors competing for awards would be for the Academy to create a separate category for motion-capture performances. To judge such performances fairly, the members would have to see videos running the original performance side-by-side with the finished film. This method might allow them to make a reasonable assessment of what the actor truly contributed.

At this stage in the history of film technology, such a category seems unlikely. So far, not that many people have been spoken of as deserving an Oscar nomination for a mo-cap performance. Even Bill Nighy, who was widely praised for his turn as Davy Jones in the second Pirates of the Caribbean film, was not touted as a possible nominee—probably because his face was so thickly covered with tentacles and partly because comic fantasy films tend not to be Oscar bait. So far the argument has primarily been made for Serkis and Saldana. Plus if the Academy did take the approach of requiring the sort of comparison film I’ve suggested, it would be a difficult and expensive thing to produce. Who knows whether Academy voters would watch five such films?

Maybe, though, as performance capture becomes less expensive and more widely used, there will be enough actors to make up a separate category. We’ve seen the animated-feature category grow from three to five nominees this year, and the number of such films being made suggests that five will become the norm. Animated films and live-action ones heavily dependent on motion-capture are somewhat similar technically, so a new category makes some sense.

A simpler and more logical alternative might be to create a category specifically for vocal performances. As has been pointed out in relation to animated films, an actor who is heard but never seen onscreen could in principle be nominated. Such a thing has never happened, but it’s not against the rules. (It’s easy to imagine that it could have happened for a performance like Celeste Holm’s unseen narrating character in Letter to Three Wives.) But with animated-feature and motion-captured performances becoming more common, a best-vocals category seems to make sense. After all, Serkis and Saldana and others like them do speak their characters’ lines, and their voices are typically not altered or enhanced very much. The digital manipulation of sound still lags considerably behind that of images.

The idea is not exactly a new one. The Annies, the awards given out each year by the International Animated Film Society, has two “Vocal Acting” categories, one each for film and television.

Very similar motion-capture technology can be used to create films that most people would agree are animated (The Polar Express, A Christmas Carol) and others that embed animated characters in a live-action setting (The Lord of the Rings, Avatar). Creating an Oscar category for vocal acting in animation or motion-captured, effects-based performances would make sense.

If actors are not yet being recognized for motion-captured performances, the Academy has been quick to honor the top scientific and technological innovators of the area of motion capture. In 2004, when The Return of the King won its golden statuettes, the less celebrated Academy technical awards included one to the Weta Digital team for its new approach to the creation of Gollum. (The award was shared with ILM for its similar use of the technique in creating Jar Jar Binks.) This year, on February 20, the Academy honored a team that included one Weta Digital member for “the design and engineering of the Light Stage capture devices and the image-based facial rendering system developed for character relighting in motion pictures” which was used on Avatar and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.

Despite fears that motion-capture may someday make directly photographed actors obsolete, there seems little chance of that happening. These techniques are fantastically expensive and are likely to remain that way for some time to come. There seems little point to using such elaborate technology to make an actor look like a real person when traditional cameras can do it so much more easily, so motion-capture performances seem suitable primarily for fantasy beings who cannot be as believably created in any other way.

Thanks to Cathy Root for calling my attention to the Los Angeles Times article.

February 25: See also Mark Harris’ essay in Entertainment Weekly. He argues that the ineffable qualities of an actor’s performance simply cannot be conveyed through motion-capture.

December 14, 2011: A member of the special-effects team at Weta Digital who worked on Avatar has sent me a comment on this entry: “Your Avatar article nails it–there were so many daily discussions about secondary ear and tail animation!”

May 18, 2014: Thanks to David Cairns for alerting me to two recent items on Cartoon Brew: Amid Amidi’s “Andy Serkis Does Everything, Animators Do Nothing, Says Andy Serkis,” which comments on an interview with Serkis on io9, and Amidi’s follow-up interview with Lord of the Rings animation supervisor Randall William Cook, which quite convincingly argues that the animators changed and extended Serkis’ performance.

Paris fun, in at least three dimensions

What he saves films from: Serge Bromberg faces down the flames.

We’re ending the first week of three in Paris. At the invitation of Jean-Loup Bourget and Françoise Zamour, David is giving three weekly lectures at the École Normale Superieure. He’s introducing some ideas about the development of film style in the 1910s and early 1920s, updated with new material from his summer research in Denmark and Brussels. Jean-Loup and Françoise have proven excellent hosts, and the first lecture seemed to go well.

We thought that Paris in January might be chilly and rainy, but we figured it had to be warmer than Madison. It turned out that Paris is experiencing unusually cold weather—about what would be normal in Wisconsin. There was light snow yesterday and last night, and the wind-chill factor was enough to turn our fingers numb if we stayed out long enough. The fountain in the center of the intersection at the northeast corner of the Jardin de Luxembourg has gradually become an iceberg.

We thought that Paris in January might be chilly and rainy, but we figured it had to be warmer than Madison. It turned out that Paris is experiencing unusually cold weather—about what would be normal in Wisconsin. There was light snow yesterday and last night, and the wind-chill factor was enough to turn our fingers numb if we stayed out long enough. The fountain in the center of the intersection at the northeast corner of the Jardin de Luxembourg has gradually become an iceberg.

Turns out, though, that it is still warmer than Madison, which is having highs in the single digits, as the weather forecasters say, and lows below zero. We’re better off here, though we wish we had brought our parkas.

It’s like Avatar, but much shorter

KT here:

The cold has driven us indoors, to museums and movies. As always seems to be the case, the Cinémathèque Française is hosting retrospectives of American films—in this case works by Laurel and Hardy and Gordon Douglas. There’s also a 3D series, which caught our attention right away. It’s not just your standard Kiss Me Kate and Dial M for Murder programming. In addition to such classics, there are many obscure films. We happened to arrive in time for the final two programs of the series, which ran from December 16 to January 3.

Our first full day in Paris ended with an evening of shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who in 1985 founded Lobster Films. Lobster has put out many DVDs by now, some of which we have reported on previously, here and here. In July, one of our entries on Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna mentioned that Serge presented a program of Georges Méliès films, in conjunction with the French release of Lobster’s huge DVD set of the great magician’s films.

Serge is quite a showman and obviously a popular figure, since there was a large crowd, including many families with children. On Saturday he chose and introduced a set of short 3D films in his series of programs usually titled “Retour de Flamme,” or “Saved from the Flames.” To begin the evening’s entertainment, he explained how, unlike modern celluloid 35mm film, the nitrate variety used up until the early 1950s ignites and burns easily. With the help of a rightly apprehensive volunteer holding up a film-can lid, Serge showed how modern celluloid catches fire only briefly and then dies out. The few inches of nitrate, however, flared up quickly.

Serge introduced each film thereafter, playing the piano to accompany the silents. The audience had been given both anaglyph (red-green) and polarized glasses, and Serge’s introductions to the films gave us time to switch between systems.

Many of the shorts shown on the program are available on DVD or YouTube, but the 3D effect plays best on the big screen. The evening began with an unannounced item, Three Dimensional Murder, a “Metroskopics” comedy short from 1942. A nervous detective visits a mysterious house and encounters Frankenstein, creeping hands, skeletons, and other ghouls and beasties, all of which find some occasion to throw things or hurl themselves toward the camera. The humor is, as a contemporary audience member might have said, pure corn and the 3D effects repetitive, but it was certainly a rare item.

Next came one of the Fleischer brothers’ cartoon shorts, Musical Memories. It was made with a patented system that used three-dimensional models as settings against which 2D cartoon figures drawn on cels moved about. (Such models can be seen fairly often in Popeye and other Fleischer cartoons of the 1930s.) There is some sense of depth. Still, the effect is strange, since the models have shading and the flat-looking figures do not. The cartoons are not 3D in the sense we typically think of, since there are no glasses involved.

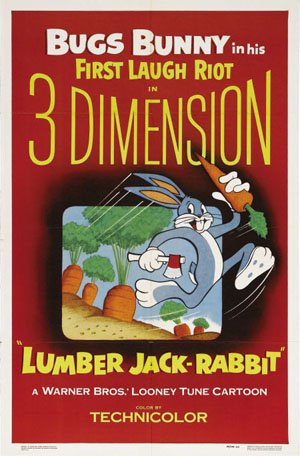

More cartoons followed, from the two main competing animation studios. Disney’s contribution was Working for Peanuts, a story set in a zoo with Chip and Dale stealing peanuts from an elephant and Donald Duck trying to foil them. Many a peanut seemed to fly out toward the spectator. Chuck Jones directed Lumber Jack-Rabbit (1954), a film that mixed size gags and spatial ones, with Bugs wandering into the domain of the gigantic Paul Bunyan. Perhaps not one of Jones’s best, but distinctly more interesting in 3D.

As Serge pointed out, most 3D technology was pioneered in the U.S. He included some exceptions, however, with a series of Soviet “Parade of Attractions” shorts shown at intervals during the evening. Experiments with underwater 3D photography and a garden of plants lacked soundtracks, but the final item, a vaudeville act with jugglers, had music and lots of bowling pins flying at the camera.

Unbelievably, there were efforts toward 3D as early as 1900. Serge showed some 3D experiments from that period by inventor Rene Bunzli. These were only about 10 seconds long and included a mildly risqué scene of a man arriving to visit his mistress and another discovering his wife in bed with her lover. The first color 3D film was shown: Motor Rhythm, made by Charley Bowers in 1940 for the Chicago Exposition and distributed by RKO. Using a combination of pixilation and 3D, the film shows a car jauntily assembling itself to a musical accompaniment, with many of the parts moving out toward the camera before attaching themselves in their proper places.

The National Film Board of Canada contributed Munro Ferguson’s Falling in Love Again, with characters wafted into the sky by road accidents and, while falling, falling in love. To watch it in high-quality 3D, go here. Pixar was represented by John Lasseter and Eben Ostby’s early digital experiment in 3D, Knick Knack, as a snowman trapped in a snow globe tries to break free to join a bathing beauty.

The evening ended with a surprise, two films that had never been meant to appear in 3D.

Méliès’s early shorts were often pirated abroad, and a lot of money was being lost in the American market in particular. After the Lubin company flooded that market with bootleg copies of a 1902 film, Méliès struck back by opening his own American distribution office. Separate negatives for the domestic and foreign markets were made by the simple expedient of placing two cameras side by side. The folks at Lobster realized that those cameras’ lenses happened to be about the same distance apart as 3D camera lenses. By taking prints from the two separate versions of a film, today’s restorers could create a simulated 3D copy!

Two 1903 titles–I think that they were The Infernal Cauldron and The Oracle of Delphi–triumphantly showed that the experiment worked. Oracle survived in both French and American copies, and the effect of 3D was delightful. For Cauldron only the second half of the American print has been preserved. Watching the film through red-and-green glasses, you initially saw nothing in your right eye, while the left one saw the image in 2D. Abruptly, though, the second print materialized, and the depth effect kicked in. The films as synchronized by Lobster looked exactly as if Méliès had designed them for 3D.

Film scholars gone wild

DB here:

William Cameron Menzies is most famous as an art director on films like The Thief of Baghdad (1924) and Gone with the Wind. He was one of the most visually daring artists to work in classic Hollywood; his eccentric framings and looming foregrounds may have influenced Orson Welles. (The Gothic distortions of Our Town and Kings Row are unlikely to be the creation of director Sam Wood.) Menzies also directed a few films, most notably the slightly nutty anti-Commie film The Whip Hand (1951).

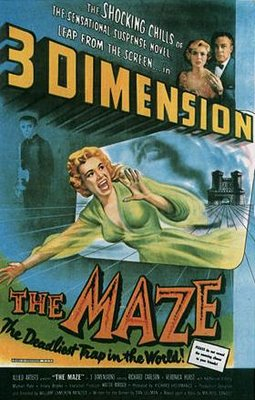

So Kristin and I had to go back to the Cinémathèque for Menzies’ rarely-seen 3D feature The Maze (1953). Alas, it was a washout. The feeble story concerns an heir returning to a castle to confront a giant frog, who may be his relative. I’d expected bravura deep-focus, with planes jutting out at me, but the film was dramatically and visually flat–no wordplay intended. The trailer, complete with fake bats on strings, is here.

We have other incidents to chronicle, but this dispatch can end with a quick list of some of the film friends we’ve encountered. We’ve already mentioned Professor Bourget, whose book on Fritz Lang came out recently (below left). We also ran into Cindi Rowell, an old friend from Pordenone and The Griffith Project, who had the excellent idea that we go to Chinatown–here hidden behind the facades of tower blocks. Cindi has vast experience in many aspects of film culture–preservation, programming, publication, web design, and the like–and is currently affiliated with the Middle East International Film Festival in Abu Dhabi.

Another old friend, Yuri Tsivian, is in Paris teaching during our visit, so we had a chance for a good dinner and lots of talk about editing in the 1910s. Below, he and Kristin pay homage to one of the shrines of Parisian cinephilia, the Studio des Ursulines movie theatre.

Left: Jean-Loup Bourget and his new book on Lang. Right: Yuri and Kristin at the Urselines.

Last night, with Kristin away in Berlin, I went to a dinner hosted by Jacques Aumont and Lyang Kim. Jacques is a major film theorist, whose many books and essays probe into the artistic qualities of cinema. His book on Eisenstein is available in English translation, as is his far-ranging study of the history and functions of images. Lyang is an outstanding photographer, whose book of haunting Christmas images Dans l’ombre de noël was just published in December. Among her pictures here are some gorgeous “fusion” images that recall our recent 3D experiences.

Then who should turn up but Marc Vernet and Rick Altman? It was an Iowa-Wisconsin reunion in the 10th. Marc is an expert on film noir, on cinematic images of absence, and on the American film company Triangle–associated with both Griffith and Ince. (Again, the 1910s.) Marc has set up a beautiful webpage full of information about early American cinema, and he blogs there frequently. Rick is known for his in-depth studies of film genre (especially the musical), film sound, and narrative theory. His most recent books, Silent Film Sound and A Theory of Narrative, are splendid contributions. Below, all four toast what turned out to be Rick’s birthday.

Today: More preparations for my lecture tomorrow, and of course at least one movie. Agora? Wiseman’s La Danse? Kinatay? The new Eugène Green, La religieuse portugaise? Or a rerelease (new print) of Minnelli’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse? Or….? The usual Parisian problem, but a good problem to have.

P. S. March 2010: After this Paris trip, I wrote an essay on William Cameron Menzies for this site.

Jacques Aumont, Lyang Kim, Rick Altman, and Marc Vernet, 9 January 2010.

The other expanded Oscar category

Two Jell-o lovers share a romantic interlude in Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs

Kristin here:

Back in early 2007, I posted an entry about the supposed over-supply of animated films due for release that year. I realize that journalists have to find topics to fill pages. That year one topic making the rounds was speculation about whether audiences would tire of so many cartoons.

Now that worry has gone, and writers rejoice over the fact that there are enough animated features from 2009 qualifying for Oscar nominations to create a field of five rather than three. There are no fewer than twenty qualifiers: Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Squeakquel, Astro Boy, Battle for Terra, Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs, Coraline, Disney’s A Christmas Carol, The Dolphin – Story of a Dreamer, Fantastic Mr. Fox, Ice Age: Dawn of the Dinosaurs, Mary and Max, The Missing Lynx, Monsters vs. Aliens, 9, Planet 51, Ponyo, The Princess and the Frog, The Secret of Kells, Tinker Bell and the Lost Treasure, A Town Called Panic, and Up.

The six nominees for the Annie Award for best feature have already been announced: Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs, Coraline, Fantastic Mr. Fox, The Princess and the Frog, The Secret of Kells, and Up (below).

The Annies are no guaranteed predictor of Oscars. Far from it, given the famous, even notorious top award to Kung Fu Panda rather than WALL-E last year. But I’m not trying to predict awards here. I just want to comment on what seems something of a watershed year for animation.

I’ve seen only six of the above films. Some of them haven’t been released yet, and others are being platformed before going wide. The Princess and the Frog is being showcased in only two theaters so far before going wide on December 11. The Secret of Kells, which seems to be the one of the more lauded of the unknown films, won’t open in the U.S. until March 6. Judging from the trailer, it’s made in a simple, somewhat abstract style that recalls the UPA alternative to Disney and Warner animation that appeared in the 1950s. (The Incredibles pays homage to that style.)

Some of these films haven’t played in Madison or, like Astro Boy, came and went quickly. I passed up other the eligible films deliberately. The first Ice Age movie struck me as mildly pleasant but one of those small-kids’ movies with little entertainment aimed at the parents. After Beowulf, I wasn’t about to see A Christmas Carol. The fifth animated item I saw was Monsters vs. Aliens, which was more entertaining than the reviews would suggest, but it’s not Oscar bait.

Ponyo on a Cliff by the Sea

In the past, any Pixar film was automatically the obvious choice as best animated feature. I think that Monsters, Inc. was better than Shrek and Cars better than Happy Feet, but perhaps Academy members felt a little guilty not sharing the wealth. It’s lucky that there was no Pixar film in 2002, so that Hayao Miyazaki could get the Oscar for his masterpiece, Spirited Away, and in 2005, when Nick Park could take home his fourth for Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. (The only Nick Park film that didn’t win an Oscar was the first Wallace and Gromit film, A Grand Day Out, which lost out to . . . Nick Park’s Creature Comforts.)

Now there are more companies producing animated films, not only in the U.S., which once used to dominate this form, but internationally as well. The Secret of Kells, for example, is a French-Belgian-Irish co-production (originally called Brendan and the Secret of Kells). Up to now, foreign animated films have had a better chance in the shorts category, but representation of films from abroad among the features will no doubt increase.

Wonderful though it is, Up is less the obvious choice than previous Pixar films have been. Coraline has earned great respect from critics and industry insiders. Witness its receipt of the largest number of Annie nominations, ten, with Up right behind it at nine. Add in Ponyo (original title, Ponyo on a Cliff by the Sea) and Fantastic Mr. Fox (below), and you have at least four credible contenders for top honors. I suspect Ponyo will be hampered by its English dubbing, including the substitution of another song for the charming final-credits one. Plus Ponyo is aimed at much smaller children than most of Miyazaki’s recent films. It does have the director’s typical focus on the environment, this time humanity’s pollution of the oceans; but it has less of the gravitas that has endeared the filmmaker’s last few films to arthouse audiences.

For what it’s worth, Fantastic Mr. Fox has a very rare 100% fresh rating at Rotten Tomatoes among the “Top Critics,” with Up at 95%, Ponyo 91%, The Princess and the Frog at 83%, and Coraline, surprisingly, at a mere 78%. The critics’ opinions don’t correlate with those of Academy voters, so those figures are probably not a good guide when it comes to your office Oscar pool.

I’d like to put in a good word for Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. It’s not likely to beat out the four powerhouses mentioned above, but it would be nice to see it nominated. It has a fast-paced, extraordinarily well-constructed script and makes for a thoroughly entertaining 90 minutes. It’s a pleasure to see a whole group of motifs, some in pretty funny but throwaway moments, coming back again and again, and just when you think they’ve been wrung for all they’re worth, they return one last time with a twist. Like Up, Meatballs‘ 3D version has some strong moments without the special effects seeming gratuitous, as when the hero has to slither down a long rope that seems to go on forever into the distance. Cloudy seems currently to be transitioning from first to second run. If you’ve got a cheap-seats theater near you, it’s worth seeing on the big screen, whether in 2D or 3.

Speaking of which, I should point out that Up, Coraline, and Cloudy were all conceived and executed in 3D (as opposed to the early digital features that retooled in-progress films for 3D). So far it’s still easier to make animated 3D films than life-action ones. All three use the technology well, though I’m sure they all look good in 2D.

Ever since the creation of the best-animated feature Oscar category in 2001, there have been complaints that it prevents outstanding animated work from being nominated for the best film of the year. Now people writing about the Oscars are complaining that there aren’t a lot of obvious live-action candidates for best film—in the very year that the Academy has to find ten of them. Maybe this year the best animated features will provide more excitement than the main event. Maybe they will also make it more evident that at this point in the history of mainstream filmmaking, the best animated films are better than any but the very best live-action films. I doubt that the animated-features category will drop back to only three nominees very often in future years.

Coraline