Archive for the 'Art cinema' Category

Vancouver envoi: What happens in movies happens between your ears

Summer 85 (2020).

DB here:

One of the nicest things anybody ever said to me came from Jacques Aumont, the distinguished French film scholar. He was visiting us in the early 1980s and I showed him a book manuscript I had just sent to the publisher. He read the first three chapters and said, “You remind us of something important. The spectator is thinking.” The book eventually came out as Narration in the Fiction Film.

In emphasizing that the spectator thinks, at least a little, I was driven to pay special attention to openings. The opening is where a film sets up information about its story world, about the action that will take place in it. We usually call this exposition. But a film also attunes us to the how as well as the what: how the story will be told. Exposition, in other words, includes introducing us to the characters and their situation but also to the ways we’ll learn about them. In the book I called the latter the “intrinsic norms” of narration.

But exposition isn’t simply a part of the plot, a chunk of opening material we need to digest. Exposition, the narrative theorist Meir Sternberg shows, is a process. In revealing what we call “backstory,” circumstances that predate the first scenes we see, exposition can go on throughout a film. (Kristin talks about this in her entry on Inception, and in revised form in our Nolan book.) So it turns out that the spectator has to keep thinking, keep reevaluating what’s being told about the story world and the way the story is told.

Three films showcased at the Vancouver International Film Festival set me thinking about these matters. Two depended on surprises, and these stemmed from the way exposition was handled. The third had very sparse exposition, asking us to gradually fill in story background through drifts and whiffs of information. In all cases, our enjoyment depends on thinking.

Surprise!

Bettina Oberli’s My Wonderful Wanda updates the ingredients of classic bourgeois comedy for the modern world of migratory caregivers. Josef and Elsa Wegmeister-Gloor oversee their pampered and confused son and daughter. Into the household comes a servant who is exploited for sexual favors by the old man. Wanda, the nurse brought in from Poland, is today’s equivalent of the chambermaid lusted after by both father and son.

As in most domestic comedies of class relations, Wanda the worker is no fool. Her duties help support her father, mother, and sons back home, and she proves herself a shrewd negotiator from the start. When Elsa asks her to perform extra chores, she demands more money. And when Elsa’s stroke-felled husband is willing to pay for sex, she agrees. Their secret bargain will, in good farce fashion, come to light in the most embarrassing way possible.

I went into the film knowing much less of the plot than I’ve just told you, so I want to keep back the rest. (Alas, the trailer overshares.) I was able to appreciate the way that Oberli’s tight script kept the surprises coming. Her script finds an admirable balance between clear structure and unpredictable turns.

Here the exposition is, in Sternberg’s terms, mostly concentrated and preliminary. The early scenes fill us in on the basic situation. Wanda is among several women met at the bus by Elsa. This is a compact way to suggest how much this class depends on the arrival of emigrant labor. Wanda is then taken to the family’s sumptuous villa. We learn about the situation as she does, and this introductory stretch culminates in Wanda’s introduction to her cramped basement room. In good traditional fashion, the exposition quickly encourages us to sympathize with the protagonist by showing her treated unfairly. On the basis of the information we get, the film’s first “act” becomes a tensely rising action in which Wanda becomes victimized by the petty conflicts that wrack the family.

A second long section begins in a lighter key, with the dismissed Wanda returning after some months, in a scene parallel to the opening. This chunk provides another concentrated dose of information, bringing us up to date on the family’s situation. Comic complications emerge when the family has to cope with a new, more pressing set of demands.

In good Renoirian fashion, Oberli gives everyone a dose of sympathy. The frailties of the son and daughter get nuanced and softened, and we see this coddled pair as less selfish than self-destructive. The action tapers into cringe comedy (drunken embarrassment) and farce (an errant cow), but it’s steered by carefully modulated character revelation, particularly on the part of Elsa, who is played by an indominatable Marthe Keller.

My Wonderful Wanda keeps surprising you to the very end; it trains us not to take everything for granted. There’s even a classic theatrical denouement, itself twisty, which is undercut by a final shot of GOFAC (Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema) uncertainty. Yet after each reversal, you think it had to be that way. What happens later is consistent with the exposition we’ve built up.

Surprise, postponed

Concentrated exposition, gathered in an opening or elsewhere, sets our expectations, so new story information can modify or revise them. For instance, when Wanda is summoned late at night to Gunther’s bedside, I assumed he needed meds or some help going to the toilet. The expository scenes had set her up as a traditional caregiver. So I was surprised when she mechanically slipped into what became clear was a sexual routine. That prompted me to recalibrate my sense of their relationship, and it made me aware of the limits of what I’d assumed.

Which is to say that exposition as a process is usually partial. We don’t get everything in the backstory at once, and sometimes what’s suppressed is central (as in My Wonderful Wanda). A more extreme example is François Ozon’s Summer 85 (Été 85). Here the expository information is distributed much more widely across the film. We get the backstory only gradually and piecemeal. Because some important information is withheld, the film nudges us toward certain expectations that need to be adjusted.

Again, I have to be careful about spoilers, so let me talk generally. In the book that I mentioned and for many years since, I’ve written a lot about flashbacks. One common schema for flashbacks is the crisis structure. The plot starts near a story’s climax and then suspends the outcome in order to shift back into the past and show how the crisis came about. The crisis structure can provide a film’s overall intrinsic norm of narration, so we expect that this pattern will carry through from scene to scene.

Ozon, another elegant storyteller, knows we have learned the crisis structure. When the opening of Summer 85 shows the teenager Alex dragged into a corridor and then interviewed by police authorities, we’re encouraged to summon up our experience of other movies. A crime has been committed, and he’s either a witness or a suspect. Ozon sets up a familiar to-and-fro pattern between past and present, an investigation and the mysterious crime leading up to it.

The distributed exposition provides flashbacks that take us chronologically through the events leading up to the night of the arrest. Alex is drawn into a love affair with David, a charismatic older boy. With his mother David runs a shop on the beach. She is slightly scatterbrained and seems unaware of their passions, while Alex’s parents are likewise in the dark (and surely disapproving). When the English au pair Kate shows up on the beach, Alex fears David will abandon him, and we expect that a classic romantic triangle will drive the film forward.

Except that’s not quite what happens. As Alex’s jealousy deepens, we might expect a sort of Patricia Highsmith crime to ensue. Instead, Ozon dares to go with a less brutal but more plausible turn of events–one that makes us reevaluate why Alex is being investigated, and what his actual crime is. By distributing exposition slowly across the whole film, Ozon not only creates a lot of curiosity about what has actually happened, he’s able to arouse expectations that will get challenged by new revelations. He exploits the how of narration to modify our understanding of what has occurred–and, it turns out, why.

I’m sorry to be so cryptic, but I face the reviewer’s dilemma of not giving away plot twists that should take you by surprise. Here, though, the surprises aren’t short and sharp, as in My Wonderful Wanda. They unfold more gradually and allow you time to think–about the characters and their motivations, and about what you took for granted might have happened. You might even feel a bit ashamed for misjudging Alex, who turns out to be loyal and forgiving in ways we might call unexpected. Yes, dancing is involved.

Surprise?

My Wonderful Wanda has a straightforward arc of conflict and resolution. Summer 85 is more nonlinear, skipping to and fro through time, but it too can be plotted as a drama of tension and release. What then to say about Kala Azar? It’s another film that teaches us how to watch it, and how to think through it. But it seems to lack those traditional patterns of coherence.

Or rather, it has other patterns. Instead of a drama of conflict and change, it explores a situation built out of routines, gradually revealed and eventually varied. This is another plot strategy, one familiar from “art cinema.” It builds a mystery into not only the story action but into the way the story is told. What is going on? And why am I told about it in this way?

Start with the title. It refers to a severe infectious disease spread to animals and humans by sandflies. It’s currently raging as a pandemic in over seventy countries. But the film Kala Azar is less about the disease (although we spot some lesions on characters who might be infected) than about the relations of humans and animals–specifically, some marginal Greeks scrounging a living on the outskirts of a city, along with the dogs, cats, and other creatures that wander into their lives.

There are three strands of action, each with its own routines. Most prominent are the couple, a young man and woman working for a service that cremates household pets. The couple live mostly on the road in their van, gathering pet remains from households and bringing them back to a central facility. They then return the ashes (not always scrupulously preserved, it seems) to the waiting owners. Another couple, the woman’s father and mother, keep stray dogs in their house. A third line of action involves Orguz, a migrant worker glimpsed from time to time at a chicken farm nearby.

The central couple have started adding roadkill to their cargo, as if believing that these creatures too deserve a serious farewell to life. And at certain points the story strands meet, although glancingly. In something close to a traditional climax, the young man, provoked by seeing a shooting party, takes a decisive action.

All of what I’ve told you is built up through dozens of short scenes, usually without dialogue. There’s probably more going on here than I’ve been able to grasp on one viewing. But the sparse, widely distributed exposition, and the apparent looseness of the plot challenge us to fill in things as best we can. Just as important, by not providing a traditional dramatic arc, director Janis Rafa encourages us to shift our attention to other aspects of her film.

We’re invited, for instance, to examine shot composition, to explore the landscapes on which the camera dwells, to scrutinize textures and gestures. These items are sometimes seen at one remove, through dirty panes of glass or layers of focus or in slim apertures.

Entire scenes often chop off faces in order to emphasize the contact that the bodies make with their surroundings, or to turn bodies into pure pattern, as when two grieving pet lovers are shown dressed identically.

These visual strategies may seem a bit arty, but I think they build up a tactile sense of the environment of these routines. Rafa has said that she wanted to evoke the “animalistic” quality of the imagery, which isn’t only a matter of a low camera position. The sensuous quality of the vegetation, streams, and roaming dogs comes across strongly. Kala Azar earns its severe gravity through its patient attention to details of a world in which humans and animals interact in very tangible ways. Stray animals meet stray humans, and the visual style registers the encounter with quiet nuance.

From concentrated preliminary exposition, to distributed and elliptical exposition, to what we might call minimal exposition: This continuum shows some creative options available to filmmakers in telling their stories. Each one invites us to build up expectations, to reconsider new information in the light of what we knew (or thought we knew), and to assemble a coherent line of action. In other words, we think. That’s not all we do, but it’s a big part of how we watch movies.

As usual, special thanks to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during this reliably exciting festival. This is usually the time of the year when Kristin and I wish we lived in Vancouver, and that feeling is sharpened by the health crisis now engulfing so many countries. Cinema helps keep us civilized.

These and other films we’ve reviewed should be making their way to other festivals, so we hope you have a chance to catch up with them.

For more on the narrative strategies I’ve discussed here, see Meir Sternberg’s magisterial Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction (1978). This is in my view one of the great books in narrative theory.

For more on narratives built on threads of routines, see this earlier entry on Chop Shop and other films at Ebertfest. An entry on editing pursues the between-your-ears theme.

Kala Azar (2020).

Venice, virtually

Careless Crime (2020)

Every September over the last three years, we’ve immensely enjoyed visiting the Venice International Film Festival. There David has participated in the Biennale College Cinema discussions with stimulating colleagues.

This year, alas, the coronavirus kept us home. But the festival did make available a selection of fourteen films online. Each could be viewed for five days at the very fair price of $6 per film. (Here is the array of choices. A few are still available, so hurry.)

We took advantage of this opportunity and watched several titles. Here are our thoughts about three of them. (The first section is by David, the second by Kristin.) We hope that if you get a chance to see them on the big screen or at home you’ll investigate.

GOFAC is back! Actually, it never went away

The Art of Return (2020).

Back in the late ’70s and early ’80s, I tried to analyze the conventions governing a certain approach to moviemaking, the one that’s come to be called “art cinema.” My examples were films by Fellini, Antonioni, Bergman, the French New Wave, and many of their contemporaries.

In the years afterward, I revisited the ideas and asked: Are these conventions still in force? My conclusion in an updated version of the essay in Poetics of Cinema (2008) was: yes. From Fassbinder to Wong Kar-wai, from Distant Voice, Still Lives (1988) to Maborosi (1995) and beyond, we can find art-cinema principles of storytelling and style. In that book, the extended example was Varda’s Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi, 1985), while other chapters traced how this tradition mobilized new options like forking-path narratives (e.g., Run Lola Run, 1998) and network narratives (e.g., Les Passagers, 1999). There’s a pirated pdf of the updated essay here.

Since then, it’s been fascinating to watch a younger generation of filmmakers take up this tradition. Every festival I visit furnishes examples, as you can see from our entries on this site. I had the same sense when watching Pedro Collantes’ The Art of Return (El Arte de Volver) and Christos Nikous’ Apples (Mila). Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema is still with us.

The Art of Return is centered on Noemi, who returns to Madrid after six years in New York. She has come home to audition for a role in a telenovela, and in the course of twenty-four hours she encounters several people from her past. The film consists of a series of duologues, as Noemi visits her dying grandfather, quarrels mildly with her sister, reconnects with her actor friend Carlos, and learns through another friend what became of Alberto, her ex.

What makes The Art of Return a prototypical art film is the way sheer chronology replaces a strongly causal plot. Apart from attending her audition, Noemi doesn’t have a strong goal; she drifts from one encounter to another. Most of these long scenes are devoted to discussions of her past, with hints about why she left Spain, as well as reactions of others to her personality. The task for a filmmaker using this episodic structure is to create patterns of revelation for us and for the character.

We need backstory about Noemi, and Collantes shrewdly avoids supplying flashbacks that would supply that. Instead, her past is refracted through the reactions of characters who are reconnecting with her, after much that has happened in their own lives. Gradually we assemble a fragmentary sense of what impelled her to go to New York. This revelation of the past is in effect the “under-plot” of the action.

Along with this pattern of revelation for us there are revelations for Noemi herself. She learns about her friend Ana’s floundering artistic ambitions, about her ex Alberto, about Carlos’ judgments of her. In an art film, the keenest revelation for the protagonist comes through an epiphany, a moment in which the character–sometimes mysteriously–gains self-awareness.

The crucial epiphany in The Art of Return, I think, occurs in a quiet scene in the park, among the trees that Noemi feels have been sculpted by a mystical force. By chance–again–she sees something that gives her the strength to make a decision. Yet in a typical art-cinema move, the outcome of that decision is withheld from us, suspended in a shot reminiscent of The 400 Blows (1959).

Collantes skillfully creates a firm pattern, with the opening scene symmetrically balanced by the final audition. In between, as in La Dolce Vita (1960) and Angela Schanelec’s Passing Summer (2000), the protagonist’s encounters provide a sampling and survey of life in the city, from the bohemian artists to the Romanian migrant community. A College selection, The Art of Return has already been acquired for theatrical distribution in Spain and other territories.

Apples (2020).

Because the art-cinema tradition minimizes a goal-directed plot, it often creates patterning through routine actions that are modified across the film. The changes in the routines reveal changes in a character or a situation. A vivid example is given in the Greek film Apples. After we’ve seen our protagonist regularly buy and eat apples (lots of ’em), he learns from a grocer that apples sharpen memory. He immediately switches to oranges. What psychology can justify this strange piece of behavior?

We understand it completely, because what has gone before has created a compelling context. The era is vaguely pre-digital, though there are some anachronisms. In the midst of an epidemic of amnesia, the poker-faced Aris is taken to a clinic for memory recovery. His doctors have created an experimental technique to give him a new life by reenacting routines of childhood, adolescence, and young manhood. As he rides a bike, fishes in a stream, visits a costume party, and goes to a dance club, he records his actions on Polaroids. These will fill an album and serve as replacement memories.

So Aris has a goal, albeit a diffuse one. We haven’t been told his overall program, so we are left to slowly figure out the rationale behind his dressing up as an astronaut or getting a lap dance. The film’s narration is almost as laconic as its protagonist, although a couple of scenes with his doctors show some sardonic humor. They eat his cooking and ignore the pathos of his situation while also, probably, misdiagnosing him.

Crucially, his retraining regimen intersects with that of another amnesiac, a woman further along in the program. Their relationship gives the film a romantic subplot, as well as its two most exuberant scenes: a dance to “Let’s Twist Again,” in which Siri seems to suddenly recover muscle memory, and a drive that spurs him to sing along with “Sealed with a Kiss.” (Hints about the under-plot give these scenes a dose of mystery and ambiguity–two more appeals of art-cinema storytelling.) All of this takes place before the apples-to-oranges shift, which in this context becomes as dramatic a twist as one would find in a thriller.

Shot and paced with extraordinary rigor in the 4:3 format, Apples is a perfect example of how GOFAC can create a distinct blend of curiosity, surprise, humor, and suspense. The film’s revelations in the final stretch are carried out as unemphatically as everything else, lending the character’s secrets an austere dignity. Apples has been eagerly acquired for many territories, and the director, who worked with Yorgos Lanthimos on Dogtooth, is preparing an English-language project. It will be, he hopes, “more accessible/mainstream.” Not entirely, I hope.

A carefully artful Iranian film

Careless Crime (2020).

Back in 2014, we were introduced to the strange world of Iranian director Shahram Mokri with his second feature, Fish and Cat. It’s a 139-minute single-take movie with a twisty plot in which the camera runs into separate groups of people in a rural lake area, with events starting to repeat from different points of view as the camera circles back on its route. We saw it in Vancouver, but it had premiered in the Orrizonti program at the Venice International Film Festival in 2013; it won a special prize “For Innovative Content.”

This year Mokri was back in the Horizonti thread with his third feature, Careless Crime. This time Mokri didn’t win a Festival prize, but the film received a FIPRESCI award for Best Screenplay.

Careless Crime is even trickier than Fish and Cat. It’s one of those puzzling films that requires the spectator to figure out the time frames of the different plot threads–and indeed how many times frames there are–and keep track of many characters. It’s a bit like Lazlo Nemes’ Sunset in the way it demands that the viewer constantly keep on the alert for the most fleeting or oblique clues as to what’s going on. (It’s interesting that Nemes and Mokri both have a penchant for lengthy tracking shots following a character closely from behind, as in the frame above.) Apples is another film that provides only a few subtle clues abut a major plot premise that eventually provides a twist at the end

There are two major plotlines. A group of four scruffy men plan to set fire to a crowded cinema as a political protest. Their actions recall an actual event that was the inspiration for the story. In 1978 a group of four arsonists set fire to the Cinema Rex in Abadan, causing the deaths of over 400 people because the exits were blocked.The event is credited with having launched the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

We follow the four men as they carry out inept preparations for their attack on the cinema. The group includes Faraj, a sad-sack who spends much of the early part of the film trying to get the nerve pills to which he is addicted. He tracks down a dealer who happens to be an employee at the local cinema museum and who is dressed in a large puppet costume, from the depths of which he digs out the precious bottle for Faraj.

The second plot involves a small, equally inept group of soldiers who have been sent to deal with an apparently unexploded missile deep in the countryside (see top). Contradictory information suggests that the missile landed some time ago and has been defused or that it landed the day before and needs urgent attention. Instead the men wander up into a local tourist area where two college girls are setting up an outdoor screening of the classic 1974 Iranian film, The Deer. This happens to be the film that had been screening at the Cinema Rex when the 1978 arson attack occurred. But the soldiers neglect their duty to solve the missile problem and spend their time waiting to see the young women’s film to find out if they are up to something nefarious. Thus two “careless crimes” may be involved. The the relationship between the two plotlines only becomes apparent late in the film.

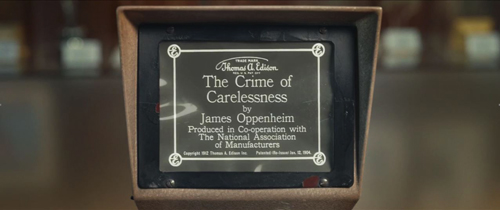

An obsession with cinema runs through both plots. The cinema targeted by the terrorists is apparently attached to the nearby museum and shows mostly art films, as is suggested by the posters for classic films that decorate the lobby. Young patrons and supporters of the cinema who hang around waiting for the show to start mention repeatedly that a friend has written an essay on The Deer, and we glimpse a poster for Kiarostami’s Close-Up. At one point Faraj, seeking the drug-dealer at the museum, sees a vintage film playing on an editing table.

It’s a 1912 Edison film, The Crime of Carelessness, in which poor safety conditions and a carelessly dropped cigarette led to a disastrous mill fire. At the end, a title in Farsi comes up, describing not the action of the silent film just shown but the 1978 Cinema Rex fire.

As all this suggests, there’s a good deal of magical realism in Careless Crime. At one point a single long take meanders around the open-air setting for the girls’ screening, picking up the same actions and dialogue repeated from different angles. During Faraj’s search for the drug-dealer, a museum employee guides him through the museum and its basement, again all in a single moving take. The seemingly endless basement is shot entirely against a black background, though at one point images of the two seemingly accompany them in the background.

Despite the grim subject matter, as in Fish and Cat, there is a good deal of self-conscious humor in Careless Crime. Little jokes are made about movies, and especially arty ones, as when a minor couple in the targeted cinema waits for the film to start. The woman looks at the screen (perhaps at a trailer?) and remarks, “I hate any film that has this laurel sign on it.” The reference is to one of the primary institutions of the international art cinema:

Is Mokri twitting the festival for not having chosen to show his films? As is now clear, his film’s repeat presence at Venice turned out to be an advantage in the long run. Although Careless Crime did not win a prize in the Horizonti competition, outside the official festival it received the FIPRESCI award for the best screenplay. Perhaps, when it finally becomes possible to return to the VIFF in person, we will see the next Mokri film and struggle not to be puzzled.

Thanks, as ever, to Alberto Barbera, Paolo Lughi, Savina Neirotti, Peter Cowie, and Michela Lazzarin for their assistance this year and in the past.

You can watch an extract of the Biennale press conference for Apples. The director discusses it in this Variety interview.

Our earlier entries on the Venice festival are here.

Apples (2020).

Venice 2018: A dazzling second feature

Kristin here:

In my first report from the Venice International Film Festival, I described the excitement of seeing three excellent and quite varied films right in a row, at consecutive early-morning press screenings: First Man, Roma, and The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. We had to wait a whole two days before seeing what may be the masterpiece of this year’s festival–this year’s Zama, as it were.

I’m sure virtually everyone who attended the press/industry screening of László Nemes’s Sunset was wondering whether it would live up to his first feature, Son of Saul (2015), which won, among other prizes, the Oscar for Best Foreign Language film. It’s one of the more deserving winners of that prize in recent memory.

The narration famously concentrates fiercely on the central character, a Hungarian Jew forced to work in a death camp helping to kill and dispose of fellow Jews. The camera follows him from behind or circles to show his face, and keeps most of the horrors occurring around him dimly visible, in the background and on the periphery of the shots, usually out of focus. Mark Kermode praised the technique as a brilliant solution to the problem of not showing those horrors but seeing them reflected in one man’s attention and expressions. We so much admired this rigorous technique that we incorporated Son of Saul into the new fourth edition of Film History: An Introduction.

My suspicion is that many present at that first screening of Sunset in Venice were wondering if Nemes could do anything beyond similarly following a single character around, restricting our point of view in a dazzling exhibition of camera choreography centered on a single intense performance. Well, Sunset is based almost entirely on the camera following (below and top) or weaving around the central character, Írisz Leiter, or framing her face in medium close-ups and close-ups.

There are a many of these “nape-of-the-neck” framings, as we might call them, with only Írisz in focus–and not always her. Again, the point of view is highly restricted to what she sees, hears, and knows. She is present in virtually every shot, or revealed to be nearby. The apparent point of view shot into which the character steps is occasionally used in Hollywood and elsewhere, but here it becomes an insistent technique.

I suspect further that, seeing virtually the same device being used again, reviewers dismissed Sunset as a far less original work than Son of Saul. It helped that the latter was a tale of the holocaust and fairly simple to follow.

In my opinion, Nemes has done something extraordinary. He has taken the same basic approach but turned it to an entirely different use. Now the restricted point of view functions to slowly dole out clues in a complicated double mystery plot. The result is complex, tantalizing, and absorbing.

Sunset is difficult to compare with other films or artworks, since it so very original. It is thoroughly modern art cinema. (Nemes worked as an assistant director to Béla Tarr, though neither of his features reflects any direct influence of Tarr.) It also, however, has something of the air of Feuillade serials. Fantômas was made in 1913, the same year in which Sunset‘s action takes place. Sunset deals with an anarchist gang, and at one point Írisz disguises herself as a man and escapes captivity through an upper-story window. There’s also a considerable streak of Grand Guignol (the theatre that was then building to its height of popularity between the two world wars), with actual and attempted rapes, rumors of a grisly murder, and torch-lit attacks by the anarchist gang.

At least two reviewers have mentioned Mullholland Drive as a comparison point. I don’t think the two films have much in common, apart from their pleasantly puzzling aspects. It’s interesting, though, that reviewers grasped at such a comparison as a way of trying to convey the nature of a very unusual film.

In fact, Nemes has said that Blue Velvet was one of his inspirations. That actually makes far more sense to me, with an innocent gradually witnessing unimaginable cruelties.

What just happened?

The film depends heavily on our gradually getting clues and information as Írisz does, and to avoid spoilers I’m going to be vague describing the plot.

The heroine is the daughter of two founders and owners of Leiter’s, a high-fashion hat shop in Budapest. Orphaned, she has learned hat-making in Trieste and returns to Budapest, aspiring to work in the shop and regain what little connection she can with her parents’ heritage. Her application for a job there opens the film, but she is turned down by the current owner of Leiter’s, Mr Brill.

She soon learns that she apparently has a brother, hitherto unknown to her, who has committed a heinous murder five years earlier. While trying to track down the truth about him, she begins to suspect that Brill may be involved in equally hideous crimes. She spends most of the film wandering about looking for clues and trying to make sense of them.

Sunset is not as puzzling or opaque or illogical as reviewers seem to think. One reviewer refers to it as “befuddling,” which it certainly is not, if one pays careful attention. Lee Marshall, one of those who evoked Mullholland Drive, complains that:

Sunset begins to crumble, to offer itself up to scorn and absurdity, once we start asking questions like “Doesn’t Irisz have regular work hours?” or “How come she always manages to get a lift in a coach just when she needs one?”

In fact there is nothing mysterious about either point. The film makes it quite clear that Írisz is not hired by Brill, even though she offers to work for free. She has no “regular work hours” because she has no job. Brill offers to let her sleep in the Leiters’ rundown house where the store’s milliners live, but he clearly is trying to control her attempts at investigating the dual mysteries. He assigns her tasks to keep her busy, but Zelma, the store’s manager and possibly Brill’s mistress, pointedly tells her when giving her a little task to do, “It doesn’t mean you’re hired.” Another task that he assigns her ends up having to be executed by the other milliners, as Írisz constantly defies Brill by leaving the store and dorm at every opportunity. When Leiter and Zelma tells her not to leave without permission, she inevitably and defiantly departs on another investigative foray. Brill’s description of her as stubborn is a considerable understatement.

As for coaches, Írisz’s brother seems to control an anarchist gang consisting largely of coachmen, some of them with motives to drive Írisz to various destinations. Brill uses his coach to fetch her back to the store and as a setting for lecturing her about not defying him by trying to find her crazed, violent brother. Coaches become another way to try and control her movements.

Such mechanics of the plot are consistently motivated, whether we catch the motivation or not. The script is extraordinarily unified and tight, despite its complexity.

After two viewings, I was glad to discover that I had understood the basic plot on my initial one, although many subtle points were filled in.

Clues–but to what?

The narrative is structured through a chain of clues, which we learn only as Írisz does. Írisz is told something–initially, that she has a brother Kálmán. She tries to follow up that clue but is thwarted for a time. Eventually, wandering about or while accompanying the milliners of the shop to various celebrations of the store’s 30th anniversary, she bumps into people who provide her with new clues. Coincidental meetings and overheard conversations are rife here, but as David has pointed out, that’s how narratives work. If there’s one tradition that Sunset doesn’t belong to, it’s realism.

The other tradition it doesn’t belong to, of course, is classical filmmaking. In a Hollywood film, one clue would lead the protagonist to another and that to another, building the chain that resolves the mystery. The action would move steadily, even when obstacles that thwart the protagonist must be overcome, creating suspense. In Sunset, a clue may intrigue the heroine, but she finds no way to follow up on it. There is a frustrating pause another clue crops up. The sense of progression is thus sporadic and somewhat random, rather than linear and strictly causal.

The overarching ambiguities of the plot arise from the fact that Írisz frequently receives contradictory clues and is unable to decide whether Kálmán and Brill are heroes or villains. At one stage Írisz thinks her brother is a sadistic murderer, but later she begins to suspect he is a hero–and still later she again believes him to be a monster. A similar series of reversals happens with Brill. Thus we may conclude that we understand where the narrative development is headed, only to have our expectations reversed. It also takes quite a long time before we realize that the Kálmán Leiter mystery and the Brill mystery are connected, at which point we must rethink them both.

In a few cases we must even infer a clue that Írisz has been given in the interval between scenes. I must admit that on first viewing I was puzzled as to how Írisz finds where a key player in past action, Fanni, lives. Seeing it again, I realized that the scene where Írisz asks Andor, a young servant at Leiter’s, where she can find Fanni ends with Andor asking eagerly, “Can you make him come back?” He’s referring to Kálmán, whom Andor secretly idolizes. A cut begins a new scene with Írisz approaching the building where she finds Fanni. When she again sees Andor in the following scene, he asks, “Did you find the girl?” Thus it is clear that Írisz told Andor she would try to bring Kálmán back, as she may intend to at this point, and that he gave her the address. It’s not easy to grasp moments like this on the fly, but it’s far from impossible.

The decision to restrict our state of knowledge so thoroughly to that of Írisz, pushing the story to the edge of comprehensibility, was deliberate. In an interview Nemes, he says, “We had an overall strategy: the viewer should go into the labyrinth of the story with the protagonist, in order fo feel the disorientation and defencelessness the protagonist experiences. This subjective aspect is what connects ‘Sunset’ with ‘Son of Saul.'”

Rory O’Connor, writing on The Film Stage, caught the labyrinthine spirit of the film better than have the other reviewers I have read. He realized and accepted that one must re-watch the film in order to appreciate its complexities:

Sunset is a film awash with such delicious ambiguities, almost to the point of damaging its basic cogency at times (not least in simple geographical terms). That said, however disorientated I became while watching Sunset, I never grew frustrated. I did, however, begin to backtrack and second-guess myself just a little, which somewhat diminished the experience (and from speaking to other critics, I was not the only one). Yet the ambiguous will always face such early criticisms–just look at Mullholand Dr.–and I not only plan on seeing Sunset again; I will relish the challenge.

This is exactly what great art films can do: make us relish the challenge.

Seeing and yet not seeing

The film is easy to relish, given its original, systematic stylistic elements.

The cinematography has been widely admired, even by those who otherwise dislike the film. The long takes with the camera moving smoothly along with Írisz through crowded streets or circuitous interiors are virtuoso shots, justifying the use of consistently handheld camera as few films have done.

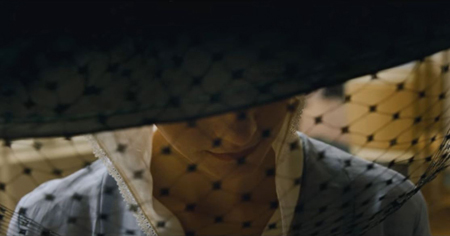

Beyond that, though, the tactic of throwing most planes of the scene out of focus is used in nearly every shot, so that we are forced intensely to concentrate on Írisz. This way we actually see even less than Irisz does, but we are not distracted from the dogged obstinacy and reckless courage of her quest.

The minute control of planes of action is masterly (above and below).

Throwing certain planes out of focus can become a motif (if one watches closely enough). Zelma is often seen out of focus in the backgrounds of scenes. In the frame at the top of this entry, she escorts Írisz to meet with Brill in the opening scene, when Írisz is applying for a job at Leiter’s. Zelma hovers in the middle ground in the frame at the top of the this section; in the frame just above, she’s in the distance, greeting the royalty from Vienna. She is seen for the last time disappearing into a soft, distorting view (bottom of the entry), going to either a posh job attending royalty or a grim fate. As usual, we have no way of knowing which, though we may suspect. The composition hauntingly recalls the early shot of her escorting Írisz, at the top.

I spotted only one shot where Írisz is wholly absent, late in the film, and that is a single tracking movement in the street inserted between two scenes. Nothing is in focus. By following Írisz we may not see everything, but without her we see even less.

Interestingly, Nemes and the cinematographer, Mátyás Erdély, originally intended to try and find an approach quite different from that of Son of Saul:

When we finished ‘Son of Saul’ and began to talk about ‘Sunset,’ we definitely wanted to do something that was very different. For example, if the aspect ratio was 1:1.37 in ‘Son of Saul,’ then it should be anamorphic 1:2.39 in ‘Sunset’; if ‘Son of Saul’ was to be photographed with a handheld camera, then let’s use the dolly for ‘Sunset.’ We made a mood test film, but the camera was in my hands already for the second shot. We realised that the kind of approach that László likes and that matches ‘Sunset’ requires that the camera be hand-held. We decided in advance that there would be dolly and anamorphic, however, in vain–in the end, it was 1:1.85 and a hand-held camera.

The film was shot in 35mm, with the final shot that constitutes the epilogue being set apart by filming on 65mm. Some release prints are available on film, and that’s what we saw in Venice. It was one of only two films shown on 35mm (the other being Vox Lux). See it on film if you possibly can. It’s gorgeous.

I unfortunately haven’t seen Son of Saul on the big screen, but Sunset is clearly a very different sort of film, much more epic in scale. It had a considerably bigger budget and is an historical piece about a beautiful, crowded city. The central set, Leiter’s Hat Store, depicts the luxurious goods that the upper classes and even royalty purchase. The filmmakers built Leiter’s in a vacant lot in a small street in Budapest’s Palace District, behind the National Museum. That way characters could exit the store and be followed by the camera into the bustling street lined with buildings that existed in 1913. As László Rajk, the production designer, says,

The space of ‘Son of Saul’ is an enclosed universe, the strict but also intimate world of the concentration camp. ‘Sunset,’ on the other hand, takes place in an open world, with all the sounds and noises of a big city. This means that in this film we–sound designer and production designer alike–had to create a completely different, open and noisy universe which reflects much less intimacy.

The amazing thing is that the designer took all this trouble and expense even though the lack of focus meant that most of the surroundings, both the built hat store and the real streets, would usually be only dimly visible to the audience. As Rajk adds, however, “those who played–and practically lived–their parts within [the store’s] walls had to believe every single second that they were in the year 1913, in Budapest, at its most elegant hat store full of secrets.”

We do occasionally see the store’s interior in focus, as in this, one of the two true point-of-view shots I spotted in the film:

Still, I would be hard put to figure out that layout of Leiter’s Hat Store or guess where the house where Írisz and the other milliners live is in relation to it.

If there’s one thing that reveals the vast difference between Son of Saul and Sunset, it’s that in the former we dread to see the offscreen, out-of-focus, peripheral things that are happening. In the latter, we yearn for a view of the crowded streets of Budapest and the splendid decor of Leiter’s Hat Shop. We are frustrated, channeled into watching Írisz but having a constant sense of the city which we glimpse occasionally in focus and more frequently in an evocative haze.

I look forward to relishing a third viewing.

As always, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome to this year’s Biennale.

Many thanks also to Michael Barker and Allison Mackie of Sony Pictures Classics for their help in preparation of this entry.

My quotations come from the interviews with the filmmakers in Hungarian Film Magazine (Autumn 2018), pp. 10, 11, 16, 17, 21. Nearly all of this issue is devoted to revealing interviews with the director, star, cinematographer, set designer, costume designers, and sound designer. In Venice, this issue was provided to the press, and it is available in its entirety online here.

Some photos from our Venice jaunt are on our Instagram page.

Weaponized VOD, at $50 a pop

Ant-Man 2: This time it’s personal. Not that it wasn’t before. But now it’s personal and expensive.

DB here:

Sean Parker, the Napster founder who taught everybody that digital piracy means never having to say you’re sorry, has come up with a new killer app. Called The Screening Room, the pitch is catching the eye of an industry that thrives on finding new niches for its product.

Stuff you probably already know

Recall, as background, that Hollywood’s economic model depends on two conditions.

(1) Strong Intellectual Property measures, both technological and legal. (Intellectual is to be taken in a broad sense here. It includes Paul Blart movies.) Encryption is designed to protect DVDs, streaming, and the Digital Cinema Package that plays in your local multiplex. Law enforcement, under the auspices of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, backs up anti-piracy with fines and jail time.

(2) Price discrimination. The premise of the classic vertically-integrated studio system was that people will pay more to see a movie sooner than other people. Why this is true still mystifies me, but facts are facts. Hence the old system of “runs.” First-run movies demanded top dollar, then second runs were at lower prices, and subsequent runs were still cheaper. When the studios surrendered their theatre ownership, the runs system remained roughly in place, chiefly because most films were platform released, playing the big cities before gradually expanding to the provinces. And network TV was basically the only ancillary market. But wide releases–hundreds or even thousands of copies playing everywhere–became the industry norm as cable, home video, and other technologies came along. The run system was reborn, and price discrimination became much more fine-grained.

Known, confusingly, as “windows,” phases of the film’s life are assigned to various platforms. After the theatrical window, typically 90 days after release, there are windows for airline/hotel access, disc (DVD, Blu-ray), Pay-per-View, streaming, cable, and on down the line. The order of these windows for any one title can vary somewhat, depending on negotiations. Most of them are designed to define price points scaled along a curve: how much it’s worth to somebody to see the movie at intervals after the initial theatrical release. By the time a movie comes to free cable, you’ve pretty much squeezed everything out of it, though the industry relies very extensively on worldwide cable purchases.

The studios depend on the theatrical release, but not because it’s the biggest source of revenue. (For the top films it can yield a lot, of course, but most films don’t recoup their costs in that window.) The theatrical release builds awareness, making it stand out downstream in the ancillaries. Without theatrical release, a film needs a lot of publicity to draw notice. Witness all those films on your Netflix or Hulu menu, all those John Cusack movies you didn’t know existed.

Independent films are increasingly relying on day-and-date release between a mild theatrical run and some form of Video on Demand. Other indie titles, along with foreign ones, are going wholly VOD, and the big players–Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon–are vigorously buying titles and backing new projects against the looming day when the studios will license fewer blockbusters to them.

The studios need the theatre chains as a shop window for their top-tier product. The theatre chains obviously need the studios to keep crowds flowing in. But some parties have flirted with day-and-date theatrical/VOD. Most famously Ted Sarandos of Netflix argued for it in 2013, then had to backtrack a few days later. On the studio end, Universal in 2011 proposed softening the theatrical window by offering Tower Heist on “premium VOD.” The plan was to drastically cut into the theatrical window by making the film available after three weeks of release, for the hefty price of $59.95. Theatre owners threatened to boycott the film, and filmmakers howled in protest. Many feared that it was the thin edge of a wedge that would eventually, through price wars, shorten windows and lower prices–not to mention wreck theatre attendance. The idea was quickly dropped.

No bad idea ever goes away, as we learn from claims that tax cuts create jobs and that we’re just one intervention away from creating peace in the world. Thanks to Parker, we now have Premium VOD in a new guise. That means a new window, with corresponding price discrimination.

Premium VOD, steroidal

Last week, The Screening Room project, sponsored by Parker and entrepreneur Prem Akkaraju, was made public. Brent Lang of Variety outlined the plan circulating among the major players.

Individuals briefed on the plan said Screening Room would charge about $150 for access to the set-top box that transmits the movies and charge $50 per view. Consumers have a 48-hour window to view the film.

To get exhibitors on board, the company proposes cutting them in on a significant percentage of the revenue, as much as $20 of the fee. As an added incentive to theater owners, Screening Room is also offering customers who pay the $50 two free tickets to see the movie at a cinema of their choice. That way, exhibitors would get the added benefit of profiting from concession sales to those moviegoers.

Participating distributors would also get a cut of the $50-per-view proceeds, also believed to be 20%, before Screening Room took its own fee of 10%.

Parker assures all stakeholders that the magic box would assure maximum antipiracy controls.

Since then, developments have been swift. Peter Jackson, Ron Howard, and J.J. Abrams are supporting the plan, while James Cameron is opposing it. The Cinemark and Regal chains, at this point the biggest theatre chains in the country, are against it, but there are hints that AMC, soon to be the biggest chain in the world if it’s allowed to purchase Carmike, might be interested. As for studios, Universal, Sony, and Fox are rumored to be considering the prospect. Once the give-and-take of dealmaking gets under way, there’s no telling what a final arrangement might look like.

What’s transparently clear is the opposition of the art-house sector. Tim League of Alamo Drafthouse issued the first warning on Monday, calling The Screening Room a “half-baked” idea. Today the Art House Convergence, an association of 600 theatres, issued a severe criticism of Parker’s plan. The open letter has been summarized in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter. Indiewire has published it in its entirety, and I do the same, as follows.

The Art House Convergence, a specialty cinema organization representing 600 theaters and allied cinema exhibition businesses, strongly opposes Screening Room, the start-up backed by Napster co-founder Sean Parker and Prem Akkaraju. The proposed model is incongruous with the movie exhibition sector by devaluing the in-theater experience and enabling increased piracy. Furthermore, we seriously question the economics of the proposed revenue-sharing model.

We are not debating the day-and-date aspect of this model, nor are we arguing for the decrease in home entertainment availability for customers – most independent theaters already play alongside VOD and Premium VOD, and as exhibitors, we are acutely aware of patrons who stay home to watch films instead of coming out to our theaters.

Rather, we are focused on the impact this particular model will have on the cinema market as a whole. We strongly believe if the studios, distributors, and major chains adopt this model, we will see a wildfire spread of pirated content, and consequently, a decline in overall film profitability through the cannibalization of theatrical revenue. The theatrical experience is unique and beneficial to maximizing profit for films. A theatrical release contributes to healthy ancillary revenue generation and thus cinema grosses must be protected from the potential erosion effect of piracy.

The exhibition community was required to subscribe to DCI-compliance in a very material way – either by financing through VPF integrators (and those contracts have not yet expired) or by turning to other models which necessitated substantial time and commitment. Those exhibitors who were unable to make the transition were punished by a loss of product. The digital conversion had a substantial cost per theater, upwards of $100,000 per screen, all in the name of piracy eradication and lowering print, storage and delivery costs to benefit the distributors. How will Screening Room prevent piracy? If studios are concerned enough with projectionists and patrons videotaping a film in theaters that they provide security with night-vision goggles for premieres and opening weekends, how do they reason that an at-home viewer won’t set up a $40 HD camera and capture a near-pristine version of the film for immediate upload to torrent sites?

This proposed model would negate DCI-compliance by making first-run titles available to anyone with the set-top device for an incredibly low fee – how will Screening Room prevent the sale of these devices to an apartment complex, a bar owner, or any other individual or company interested in creating their own pop-up exhibition space? We must consider how the existing structures for exhibition will be affected or enforced, including rights fees, VPFs and box office percentages.

A model like this will also have a local economic impact by encouraging traditional moviegoers to stay home, reducing in-theater revenue and making high-quality pirated content readily available. This loss of revenue through box office decline and piracy will result in a loss of jobs, both entry level and long-term, from part time concessions and ticket-takers to full time projectionists and programmers, and will negatively impact local establishments in the restaurant industry and other nearby businesses. How many of today’s filmmakers started their careers at their local moviehouse?

There are many unanswered questions as to how this business model will actually work. The proposed model, as we have read in countless articles, suggests exhibitors will receive $20 for each film purchased. At first glance, an exhibitor may think it represents a small, but potentially steady, additional revenue stream. But how will this actually be divided among the number of theaters playing the purchased title; will exhibitors who open the title receive more than an exhibitor who does not get the title until several weeks later (based on a distributor’s decision); who will audit the revenue to ensure exhibitors are being paid fairly; does this revenue come from Screening Room or from the distributor… these are just a few of the issues yet to be explained.

Similarly, Screening Room promises to give each subscriber two free cinema tickets with each film purchase. Yet to be disclosed is how an exhibitor will recoup the value of those tickets from Screening Room so they can then pay the percentage of box office revenue owed to the distributor of the film. Yet to be explained is who will manage the ticket program details such as location choice, method of purchase, and so on. Will all exhibitors be expected to honor Screening Room free tickets, or will some exhibitors receive preferential treatment over others?

We strongly urge the studios, filmmakers, and exhibitors to truly consider the impact this model could have on the exhibition industry. We as the Art House and independent community have serious concerns regarding the security of an at-home set-top box system as well as the transparency and effectiveness of the revenue-sharing model. Our exhibition sector has always welcomed innovation, disruption and forward-thinking ideas, most especially onscreen through independent film; however, we do not see Screening Room as innovative or forward-thinking in our favor, rather we see it as inviting piracy and significantly decreasing the overall profitability of film releases.

At this time and with the information available to us we strongly encourage all studios to deny all content to this service.

One point of clarification. Some reports have interpreted the paragraph beginning “We are not debating the day-and-date aspect of this model…” as meaning that art-house programmers, managers, and owners are okay with day-and-date VOD. But many Art Housers wish that day-and-date VOD had been strangled in its cradle. For those people, “not debating” doesn’t mean “accepting” or “not disputing.” It means that this is not the occasion for taking issue with that feature of the concept, as the Parker proposal introduces serious problems of its own.

The churn around this proposal is turbulent; stories kept popping up as I was writing the entry. A useful update is here. To keep up to speed, you may want to visit these two summative links, one for Variety and the other for The Hollywood Reporter.

There were, and are, still second-run movie houses. To my joy, Ant-Man, released last summer, has been playing for at least seven months at our second-run house here in Madison. And in 35! Is this a record in modern times? Also, too: My Ant-Man image up top comes from the first film, not the sequel, which doesn’t yet exist. I was just fooling and pretending.

What’s the Art House Convergence? Visit their site here. My visit to their annual confab is recorded here. An updated version is available in Pandora’s Digital Box.