Archive for the 'Art cinema' Category

Screenplaying

Design by Christina King.

DB and Kristin here:

Two years ago DB reported on the gathering in Brussels of the Screenwriting Research Network (here and here). This year, thanks to our colleagues J. J. Murphy and Kelley Conway, our department hosted the conference. Again, it was chock-a-block with stimulating papers. We also introduced our visitors to the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, which houses thousands of screenplays. It wasn’t all work, either. Participants were spotted lingering at our lakeside terrace or making their way through the cafes and saloons lining State Street. We believe it’s fair to say that a hell of a time was had by all.

Since there were simultaneous sessions, nobody could attend everything, and we can’t run through all the papers we heard. (So do consult the program for more information.) Herewith, some highlights that set us thinking.

In the key of keynote

Larry Gross and Jon Raymond.

The four keynoters encapsulated the conference’s very wide range. In a workshop keynote Jill Nelmes, Editor of the Journal of Screenwriting, offered a historical survey of screenwriting research in all media, with special emphasis on television. The Big Hollywood Movie was covered by Kristin, whose paper, “Extended How?” examined the ways in which directors’ cuts and extended editions handle the multi-part structure she posits as a foundation of contemporary Hollywood. We won’t say more here, since she may turn it into a blog for this site.

Larry Gross had already started off the conference with a bang by taking us to Japan. Larry has written 48 HRS, Streets of Fire, Geronimo, True Crime, and other mainstream studio pictures, as well as television episodes, TV mini-series, and independent films like Prozac Nation and We Don’t Live Here Anymore. He also writes outstanding film criticism for Sight and Sound, Film Comment, and other journals, and he teaches screenwriting at New York University. Scott Macauley’s informative March interview with Larry is at Filmmaker Magazine.

Larry’s keynote, “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting,” tackled the question of how filmmakers decide to share story information with the audience. What do the characters know and when do they know it? What does the audience know, and when? Storytelling, Larry suggested, develops out of the interplay of these two sets of questions. He added, perhaps hoping to provoke purists who consider film to be sheer self-expression: “Thinking about the audience is not always reactionary.”

Larry’s keynote, “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting,” tackled the question of how filmmakers decide to share story information with the audience. What do the characters know and when do they know it? What does the audience know, and when? Storytelling, Larry suggested, develops out of the interplay of these two sets of questions. He added, perhaps hoping to provoke purists who consider film to be sheer self-expression: “Thinking about the audience is not always reactionary.”

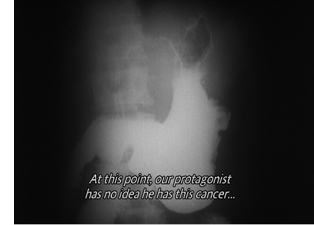

He illustrated his ideas with an in-depth examination of Kurosawa’s Ikiru. He had long thought the film “an official liberal-humanist classic,” until a course with Annette Michelson at NYU showed him that there was a lot to ponder there. Specifically, Kurosawa starts by telling the audience the end of the story: Watanabe will die of cancer. But he doesn’t know that, and neither do all the people he encounters. The strategy denies us a lot of suspense, so to hold our interest Kurosawa must engross us by delineating his relations with his colleagues, with the mothers petitioning for the neighborhood sump to be drained, and with the stray people he meets casually on his night out.

Larry showed how carefully Kurosawa played off the characters’ indifference, misunderstanding, and lack of awareness. In particular, the neighborhood wives display to Watanabe what Maurice Blanchot called “the ignorance and spontaneity of true affection.” Ikiru’s refusal to explain what it means typifies a kind of cinema that asks the audience to share the burden of understanding. “Ikiru understands how a screenplay can be composed with the audience.”

Jon Raymond’s keynote carried things to independent US film. Jon has become famous for a novel (The Half-Life) and short stories (Livability), as well as for his screenplays for Kelly Reichardt’s features. The most recent, the forthcoming Night Moves, is currently in competition at Venice. The teaser title of Jon’s address, “Screenwriting as Earth Art,” turned out to be a reference to the fact that most of his stories take place in the vicinity of his home. He has found satisfaction by composing on familiar ground.

In younger days Jon tried painting and filmmaking; a Public Access feature based on the comic strip Crock turned out to be “a movie best experienced in fast forward.” But he found that writing offered the most creative satisfaction. At the same time, while assisting Todd Haynes on Far from Heaven, he met Kelly Reichardt, who was looking for a property to adapt on a small budget. The result was Old Joy, “a New Age western,” in which two men display the violence latent in the new passive-aggressive masculinity flourishing on the Coast. Jon believes that Reichardt’s handling created a cinematic parallel to the dense intricacy of a short story.

In later collaborations, Jon mapped his patch of Portland in other ways. Seeing the annual migration of workers to Alaskan canneries, and hearing the train whistles wafting through his neighborhood, he created the story that became Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy (above). Reichardt began adapting the story to film before he had finished writing it. Similarly, Jon merged the booming housing market of the 2000s and the history of the Oregon Trail into a project that paralleled today’s gentrification with nineteenth-century colonization. Reichardt turned his screenplay into Meek’s Cutoff, a “desert poem” that completed what some have called their Oregon Trilogy. For Jon, the trilogy constitutes an alternative regional history, one that traces the process of “sowing the land with failure, betrayal, and humiliation.”

Plots and no plots

The Adventures of André and Wally B (1984).

More than most areas of filmmaking, screenwriting reminds us of the institutional framework surrounding most creative work cinema. Scholars studying the screenplay are naturally often pursuing the endless revisions, refusals, and rethinks that a film goes through in the preparation phase. It’s easy to see this as a one-versus-one struggle, but in many cases the process takes place within a social environment possessing its own roles and rules.

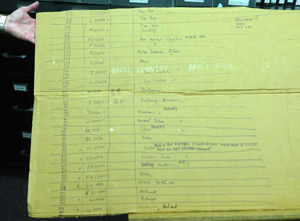

Ian MacDonald offered an excellent example in his study of the work processes behind the UK television soap opera Emmerdale. He proposed that we replace model of industrial film production as an auto factory with that of a carpet factory. Instead of the TV episode being seen as a discrete unit, like a car, it should be conceived as an ongoing fabric woven of many threads. In Emmerdale and other series, the unit of production isn’t the episode but rather the story line. Each episode is sliced out of a much bigger stretch of ongoing patterns. Ian illustrated this with the writers’ planning chart that was mounted on the wall.

The vertical column represents scenes, marked off as episodes. The characters are color-coded cards connected by solid liness that weave their way through the scenes. These waves are the melodies; the scenes are the bar-lines. In each episode, two or three characters are given prominence, while the subordinate ones contribute their harmonies. Ian’s discussion reminded me of how Hong Kong filmmakers did much the same thing in the 1980s: plotting films reel by reel and color-coding certain elements—gags, fights, and chases—to make sure that each reel had its share of attractions. This is the sort of insight into structure that institutional research can yield: Structure is these people’s business.

Other Hollywood studios envy Pixar for to its appealing, carefully structured stories. Richard Neupert showed how that tradition goes back to the earliest years at Pixar. Even in demo films which were made to show off technological innovations, the makers tried to reveal how computer animation, even in its early, simple form, could create engaging tales. At a period when computer animation could only render smooth, simple shapes, the Pixar team found appropriate subject matter, with highly stylized characters in The Adventures of André and Wally B and Luxo, Jr.

Remarkably, these tiny films have balanced “acts.” Each is 80 seconds long and has a key action at exactly 40 seconds in: the entrance of Wally B and the moment when the little Luxo lamp jumps on a ball. Similarly, Red’s Dream‘s parts run 50-100-50 seconds. This care in timing continued with the features: Toy Story’s midpoint comes when Woody finally shifts strategies, realizing he has to work with Buzz. And what about Pixar’s perceived slump in recent years? someone asked during the question session. Neupert pointed out that Pixar’s founders have aged, and there may no longer be quite the sense of excitement and discovery pushing the team to surpass others and themselves.

Sometimes institutional traditions come into conflict. Petr Szczepanik’s talk traced in meticulous detail how screenplay development in Czechoslovakia was altered in the years from 1930 to the 1950s. Czech filmmakers developed their own system of moving from theme and story germ to final screenplay. But with the Communist takeover there came the demand to add the Soviet model of the “literary screenplay,” a detailed specification of scenes, dialogue, and the like. Filmmakers resisted this, preferring the customary and more flexible “technical screenplay” that was largely the province of the director. Petr mentioned new screenwriting trends pioneered by Frank Daniel that gave directors the authority to modify the literary format. By the late 1950s, filmmakers had found ways to make the literary screenplay a less rigid blueprint for filming.

Back in the USSR, the screenwriting institution found even the literary screenplay a difficult basis for mass output. Maria Belodubrovskaya’s talk focused on “plotlessness” as a rallying cry and term of abuse in the 1930s-1940s Soviet film. There were long debates about whether “themes” sufficed to make a film or whether you needed strong plots in the Hollywood vein. Film-policy supervisor Boris Shumyatsky urged the latter course, and the popular success of Chapayev (1934) seemed to support his case. By the late 1930s, though, Shumyatsky was purged and the tide turned against strong plots. Film executives found a concern with plot too “Western” and “cosmopolitan,” and annual film production became based on themes rather than stories. Most provocatively, Masha suggested a lingering influence of Soviet Montage storytelling, which based films on vivid but loosely linked episodes. She illustrated her case with an analysis of Pudovkin’s In the Name of the Motherland (1943), with its diffuse lines of action and sudden reversals and omissions.

Back we go

Scarface (1932).

Naturally, Madison wouldn’t be Madison without strong papers on the history of cinema, and many conference presentations suited the tenor of the joint.

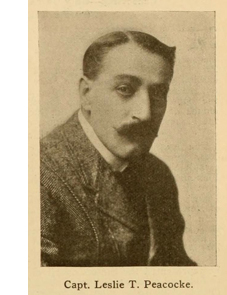

Stephen Curran offered an enlightening study of one of the least-known but most colorful figures in early American screenwriting, a man with the dashing name of Captain Leslie T. Peacocke. He was credited with over 300 screenplays, including Neptune’s Daughter (1914). He acted, directed, and wrote novels too. He was one of the first script gurus, writing magazine columns on the craft and eventually the early manual Hints on Photoplay Writing (1916).

Stephen Curran offered an enlightening study of one of the least-known but most colorful figures in early American screenwriting, a man with the dashing name of Captain Leslie T. Peacocke. He was credited with over 300 screenplays, including Neptune’s Daughter (1914). He acted, directed, and wrote novels too. He was one of the first script gurus, writing magazine columns on the craft and eventually the early manual Hints on Photoplay Writing (1916).

Stephen surveyed Peacocke’s contribution to the emerging scenario market. Peacocke believed that successful screenwriting couldn’t be taught, but he could give hints about developing original stories, thinking in visual terms, and practical craft maneuvers like snappy names for characters. During the Q & A, Stephen added that a great deal of Peacocke’s rhetoric was aiming to raise his own profile in the industry. In conversation afterward, Stephen praised the Media History Digital Library and Lantern (flagged in an earlier blog) for immensely helping research into early film. Here, for example, is Peacocke’s 216-item dossier on Lantern.

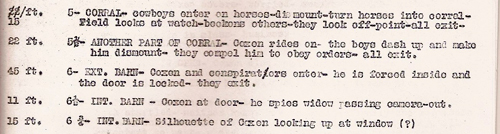

Andrea Comiskey argued that for the same period, we can study scripts and extrapolate craft practices that otherwise go undocumented. Her focus was the disparity between what manuals like Peacocke’s said and what actually got jotted down in working scenarios. Studying several screenplays from the American Film Company of Santa Barbara, she found that the manuals’ recommended stylistic approach was revised in the course of shooting.

The manuals proposed that each scene would be built out of a lengthy single shot (called, confusingly, a “scene”) which could at judicious moments be interrupted by an “insert.” An insert was usually a letter or piece of printed matter read by the characters, but it might also be a detail shot of a prop, hands, or an actor’s face.

In preparing scenarios, the writers assigned numbers to each “scene,” as the manuals recommended. But Andrea found that in the filming, the director and cameraman added shots, breaking down the action into more bits. This was, in effect, a move away from the strict scene/insert method and a shift toward what would become the classical continuity system. To maintain a paper record for the editor, the interpolated shots would be recorded and labeled in fractions. Instead of a straight cut from 6 to 7, the filmmakers might wedge in 6 ½, 6 ¾, and so on. Here’s an extract from Armed Intervention (1913), courtesy Andrea.

Strange as this sounds to us today, it was preferable to renumbering the shots, which could cause confusion. (Is shot 17 the original 17 or the later one?) The fractions kept the footage consistent with the scenario across the production process. So it turns out that (as usual?) filmmakers were a bit ahead of the screenplay gurus, even back in the 1910s.

Lea Jacobs asked a question about the transition from silent to sound film: How did filmmakers manage the pacing of dialogue? Silent movies had great freedom of pacing, while the shift to talkies seemed to many filmmakers to slow things down. Lea’s research indicated that two strategies for speeding things up emerged: creating shorter scenes and shortening dialogue passages within them. She reviewed how these ideas emerged in Hollywood’s own discourse in the 1930s and in certain films. In the first years of sound, scenes were rather long (often because they were derived from stage plays) and speeches were similarly extended. But in the 1931-1932 season, she argued, short scenes and quicker repartee became more common.

She traced the process in three films of Howard Hawks, from the stagy Dawn Patrol (1930) through The Criminal Code (1931), which opens in the new style but then turns to longer sequences, and then to Scarface (1932). The gangster film shifted toward shorter scenes and more laconic dialogue than did other genres, and Scarface displays this in full flower. Tony Camonte’s takeover of the South Side beer trade is presented in six harsh, violent scenes that add up to little more than three minutes. Workers in the sound cinema, it seems, were soon pushing toward that rapid tempo we identify with the 1930s.

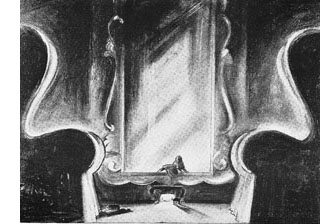

Storyboards have now entered academic studies. Chris Pallant and Steven Price offered some historical insights by comparing some early storyboards by William Cameron Menzie with those of early Spielberg films. When Menzies was storyboarding Gone with the Wind, he called it “a complete script in sketch form” and “a pre-cut picture.” Selznick’s publicity director characterized it: “The process might be called the ‘blue-printing’ in advance of a motion picture.” The striking revelation was that the storyboarding was not done after the script was finished. Menzies worked from the book, and the storyboard and script were created in parallel. Menzies’ storyboard for the 1933 Alice in Wonderland revealed a similarly elaborate process. It was 624 pages long, with one page per intended shot. Each page contained a sketch at the top, a paragraph describing the planned technological traits of the shot (such as lens length), and the traditional screenplay dialogue at the bottom. It’s hard to imagine many people other than a genius like Menzies being able to provide such a comprehensive plan for a film. (A sketch for Alice is on the right here. DB has written about Menzies here and here.)

Storyboards have now entered academic studies. Chris Pallant and Steven Price offered some historical insights by comparing some early storyboards by William Cameron Menzie with those of early Spielberg films. When Menzies was storyboarding Gone with the Wind, he called it “a complete script in sketch form” and “a pre-cut picture.” Selznick’s publicity director characterized it: “The process might be called the ‘blue-printing’ in advance of a motion picture.” The striking revelation was that the storyboarding was not done after the script was finished. Menzies worked from the book, and the storyboard and script were created in parallel. Menzies’ storyboard for the 1933 Alice in Wonderland revealed a similarly elaborate process. It was 624 pages long, with one page per intended shot. Each page contained a sketch at the top, a paragraph describing the planned technological traits of the shot (such as lens length), and the traditional screenplay dialogue at the bottom. It’s hard to imagine many people other than a genius like Menzies being able to provide such a comprehensive plan for a film. (A sketch for Alice is on the right here. DB has written about Menzies here and here.)

Spielberg used sketches in addition to a screenplay from the start. Duel, surprisingly enough, was supposed to be shot in a studio, but the director insisted on working on location. The sketches he made for it do not resemble a traditional storyboard but instead are like pictorial maps framed from an extremely high angle. He also plotted out the paths of the vehicles with overhead views of the roads. The storyboards for Jaws were done from the novel at the same time that the script was being written, just as Menzies had done with Gone with the Wind. (The same thing happened with Jurassic Park.) Storyboards were vital, among other things, for telling the crew which of the four versions of the shark would be used. One fake shark had only a right side, another a left, and which one was needed depended on the direction the shark was crossing the screen. The speakers distinguished between the “working” storyboard and the “public” one. The public one is what sometimes get published, but it usually has each image cropped to remove the information about the shot (e.g., who will work on it) noted underneath.

Brad Schauer contributed to a roundtable on the American B film back when The Blog was in its infancy. He has been researching the role of B’s in the industry for many years, and he brought to our event some new ideas about them in the postwar period. His paper, “First-Run and Cut-Rate” showed that there were still plenty of theatres showing double bills in the 1950s and 1960s (DB can confirm it), and the market needed solid, 70-90 minute fillers. One answer was the “programmer,” or the “shaky A” that featured somewhat well-known talent, color, location shooting, and familiar genres (Westerns, swashbucklers, horror, crime, comedy, and science fiction). Shot in half the time of an A, with budgets in the $500,000-$750,000 range, programmers fleshed out double bills and sometimes broke into the A market.

What does this have to do with screenwriting? Brad decided to test whether Kristin’s ideas about four-part structure (here and here) held good with programmers. Looking at several, he came up with a plausible account that films like Battle at Apache Pass and Against All Flags simply compressed the four parts into short chunks, typically running fifteen to twenty minutes. In The Golden Blade, Rock Hudson formulates his goal (revenge) two and a half minutes into the movie.

Too few things happen?

La Pointe Courte (1955).

In most films, Agnes Varda said, “I find that too many things happen.” How can screenplay studies move beyond Hollywood’s jammed dramaturgy to consider the more spacious sort of storytelling we find in “art cinema”?

Colin Burnett offered a general overview of art-cinema norms that is somewhat parallel to our and Janet Staiger’s The Classical Hollywood Cinema. To a great extent, of course, “art films” differ from classically constructed films. They can be more ambiguous, more reflexive, more stylized and at the same time more naturalistic. They often replace a tight causal chain with episodic construction and nuances of characterization. The protagonists may have complex mental states; they may have inconsistent goals, or no goals at all; they may be passive; they may have shifting identities.

Yet Colin argued against claims that art films lack narrative altogether. “Art films offer reduced scene dramaturgy, rarely its complete absence.” They possess structuring devices comparable to Hollywood acts. A film’s large-scale parts may be based on a character’s development, on changes in space or time, or on variations of action and/or reaction. A question was raised as to whether such a broad category as art cinema could be characterized in such ways. Given the enormous range of types of films made in the Hollywood tradition, however, it seems possible that the art cinema could be described in a similar fashion. (For our thoughts on the matter, go here and here.)

A great many art-film strategies can be seen as stemming from modernism in literature and the other arts. As if offering a case study illustrating Colin’s argument, Kelley Conway focused on La Pointe Courte. Varda’s first film is now coming to be considered the earliest New Wave feature. But Varda wasn’t the prototypical New Waver. She wasn’t a man, she wasn’t a cinephile, and she took her inspiration from high art, not popular culture. A professional photographer who loved painting and literature, she brought to this film (made at age 26) a bold awareness of twentieth-century modernism. The result was a striking juxtaposition of stylization and realism, personal drama and community routine. In La Pointe Courte, we might say, neorealism meets the second half of Hiroshima mon amour.

Inspired by Faulkner’s Wild Palms, Varda braided together two stories. While families in a fishing village live their everyday lives, an educated couple work through their marriage problems in a long walk. Remarkably, Varda had not seen Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy. After supplying background on the production process, Kelley focused on matters of performance. She explained how Varda, well aware of Brechtian “distanciation,” made the couple’s dialogue deliberately flat. By contrast, the villagers’ lines, through scripted, were treated more naturalistically. La Pointe Courte emerges as an anomie-drenched demonstration of how little you need to make an engrossing movie.

To script or not to script (or to pretend not to script)

Maidstone (1970).

The SRN embraces research into the absence of a script as well. At one limit is the work of avant-gardists like Stan Brakhage. John Powers’ “A Pony, Not to Be Ridden” discussed how non-narrative filmmakers used paper and pencil to organize their work, much as a poet might make notes on a draft. John’s examples were three films by Brakhage, each developed out of sketches and jottings assembled after shooting but before editing. Unconstrained by any script format, Brakhage had to invent his own version of storyboarding and screenplay notes.

Compilation filmmakers also discover their structure in the process of collecting and sifting material. Documentarist Emile de Antonio, whose collection resides in our WCFTR, had to build his screenplay up after he had assembled some material. “A script won’t be ready,” he remarked, “until the film is finished.” Vance Kepley’s paper showed that In the Year of the Pig was the result of a massive effort of “information management.” De Antonio sought out press clippings, sound recordings, and news footage and then had to create an archive with its own system of labeling, cross-references, and easy access.

De Antonio started with the soundtrack, which was itself a montage of found material, and then created a “paper film,” cutting and pasting vocal passages and descriptions of images. At the limit, he charted his film’s structure with magic-marker notations on large strips of corrugated cardboard, as Vance illustrated.

One panel session took a close look at improvisation in fiction features. Line Langebek and Spencer Parsons gave a lively paper with the innocuous title “Cassavetes’ Screenwriting Practice.” Explaining that Cassavetes did use scripts (“sometimes overwritten”), and he relied on actors to help create them in workshop sessions, they proposed thinking of his work as exemplifying the “spacious screenplay.” Their ten principles characterizing this sort of construction include:

Write with specific actors in mind. Use a “situational” dramaturgy rather than a rise-and-fall one. The work is modeled on free jazz, with moments set aside for specific actors. Even minor actors get their solos. Shoot in sequence, so that emotional development can be modulated across the performances.

Line and Spencer’s precise discussions cast a lot of light on the specific nature of Cassavetes’ creative process and pointed paths for other directors. They added that the spacious screenplay is really for the actors and the director; the financiers should be given something more traditional.

Norman Mailer called Cassavetes’ films “semi-improvised.” He tried to go further, J. J. Murphy explained in “Cinema as Provocation.” Mailer wanted his three films Wild 90, Beyond the Law, and Maidstone to be completely improvised, utterly in the moment. “The moment,” he proclaimed, “is a mystery.” Mailer opposed the “femininity” he claimed to find in Warhol’s films, so he encouraged his male players to indulge their machismo playing gangsters, cops, and aggressive entrepreneurs. J. J., whose book on Warhol stressed the psychodrama component of the films, finds Mailer no less devoted to having his players work out their problems through unrestrained behavior. The climax of Maidstone, in which an enraged Rip Torn begins to strangle Mailer, becomes the logical outcome of Mailer’s needling provocation of his actors. How ya like the mystery of this moment, Norman?

Within the Hollywood industry, improvisation is identified strongly with Robert Altman’s films, but Mark Minnett‘s “Altman Unscripted?” shows another side to his work. Focusing on The Long Goodbye, Mark finds that the film doesn’t vary wildly from the script. The principle plot arcs aren’t changed, although Altman decorates them by letting minor characters inject some novelty. He encouraged the guard who does impressions of Hollywood stars, and he gave latitude to Elliott Gould, whose improvisation elaborates on the issues of trust and bonding that are embedded in the script. Some scenes are condensed or altered, as often happens on any production, but the Altman mystique of freewheeling, anything-goes creativity isn’t borne out by the film. Altman’s characteristic touches are built around what’s “narratively essential,” as laid out in the screenplay.

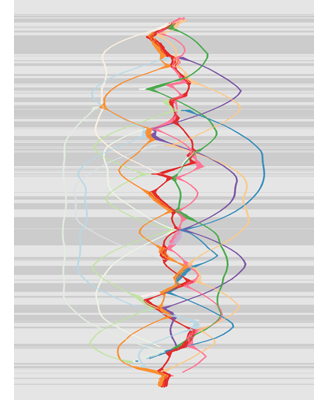

We learned a lot more at the conference than we can cover here. For example, Jule Selbo brought to our attention Sakane Tazuko, a woman screenwriter-director in 1930s Japan. Rosamund Davies explored the ways in which transmedia storytelling could enhance historical dramas. Carmen Sofia Brenes traced out how different senses of verisimilitude in Aristotle’s Poetics might apply to screenwriting. We learned of a planned encyclopedia of screenwriting edited by Paolo Russo and a book on the history of American screenwriting edited by Andy Horton. Not least, there was Eric Hoyt, whose “From Narrative to Nodes” showed how digitized screenplays could be used to graph character action and interaction over time. (A nice moment: When asked if his analytic could be rendered in real time, he clicked a button, and the thing moved.) Once more we’re in the x-y axes of Emmerdale and In the Year of the Pig, but now in cyberspace. Eric’s results on Kasdan’s Grand Canyon appears here on the right, but only as an enigmatic tease; he will be contributing a guest blog here later this fall.

In other words, you should have been here. Next time: October in Potsdam, under the auspices of Kerstin Stutterheim at the Hochshule für Film und Fernsehen “Konrad Wolf.” DB was at this magnificent facility last year for another event, and we’re sure–to coin a phrase–a hell of a time will be had by all.

Thanks very much to J. J. and Kelley, as well as to Vance Kepley, Mary Huelsbeck, and Maxine Fleckner Ducey of the WCFTR. Special thanks to Erik Gunneson, Mike King, Linda Lucey, Jason Quist, Janice Richard, Peter Sengstock, Michael Trevis, and all the other departmental staff that helped make this conference a big success.

Thanks also to Noah Ollendick, age 12, who asked a smart question.

P.S. 4 Sept: Thanks to Ben Brewster for a correction!

J.J. Murphy and Kelley Conway, conference coordinators.

Silent films, old and new

Blancanieves

Kristin here:

February and March have been good to silent cinema. Time for a round-up of some highlights as we impatiently anticipate Il Cinema Ritrovato, coming up in a little over two months.

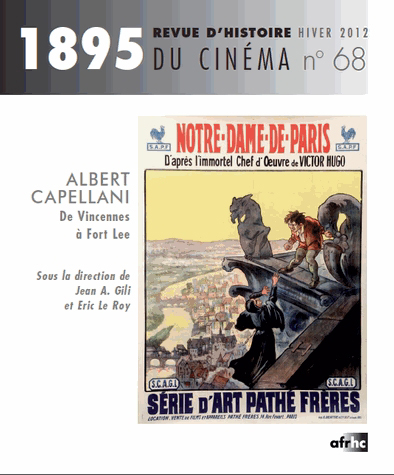

Publications on Albert Capellani

In reporting on the 2010 and 2011 programs of Il Cinema Ritrovato, I highlighted one of the festival’s major revelations, that of the silent films of Albert Capellani. These generous doses of Capellani’s splendid films were put together by Mariann Lewinsky, who realized his importance after she included some of his shorts in her annual “Cento Anni Fa” programs. In my entries I argued that Capellani was revealed as one of the early cinema’s great masters. (The 2010 entry is here, and the 2011 one here.)

Not surprisingly, during the intervening years, scholars have been busy researching Capellani’s films and career. March 6 to 24 saw a major retrospective at the Cinémathèque Française. (Information on the program is still available online, as is a detailed press release.) Shortly before it began, the first biography appeared: Christine Leteux’s Albert Capellani: Cineaste du Romanesque, with a foreword by Kevin Brownlow.

Leteux discovered Capellani in May of 2012, thanks to seeing Notre-Dame de Paris and Les Misérables at the Forum des Images in Paris. Setting out to learn more about the filmmaker, she realized how thoroughly his memory had nearly vanished from film history. She sought out and received the cooperation of his grandson, Bernard Basset-Capellani, whom she describes as “intarissable” (inexhaustible) on the subject.

The result is a solid, traditional biography, with chapters mostly organized around the companies for which Capellani worked (Pathe, SCAGL, World, Mutual, and so on) and some of his key films (Les Misérables, The Red Lantern). The prose style is easily readable French, at least to someone like me with an average knowledge of the language. For an interview with Leteux concerning the book, see here.

The book is on sale at the Cinémathèque’s shop, which unfortunately does not sell online. It was supposed to be available on Amazon.fr, but so far is not. The easiest way for those outside France to order it is through three third-party book-sellers on amazon.fr, all offering it at the cover price of 14.90 €. Leteux’s book is a vital source for anyone interested in early cinema.

I was pleased to see that the last chapter ends with some quotations from my second entry on Capellani, ending with “With the end of the main retrospective, however, it is safe to say that from now on anyone who claims to know early film history will need to be familiar with Capellani’s work.”

The book includes a filmography and list of films available on DVD. These include a new one, a restoration of The Red Lantern by our friends at the Cinematek in Brussels, available on Amazon.fr or directly from the Cinematek’s shop.

The French-language historical journal on cinema, 1895, timed its March, 2013 issue to coincide with the Cinémathèque’s retrospective. It is entirely devoted to Capellani. I have not had a chance to see it yet, but the table of contents is available here. The only online purchasing source for individual issues I have found is here; the page gives a lengthy summary of the contents.

Mariann continues to search for more surviving prints for restoration and eventual inclusion in future editions of Il Cinema Ritrovato. She has sent me some tantalizing news about recent discoveries and restorations. There will be a third Capellani season in 2014. This will probably include some of the director’s American films: Social Hypocrites (now restored), Flash of the Emerald (the one surviving reel), Inside of the Cup (surviving but so far with no projection print), Eye for Eye (two surviving reals), Sisters, and the French film Le Nabab. Other possible restorations include House of Mirth, La belle limonadiere, and Oh Boy!

A description of the 2013 Ritrovato festival is available here.

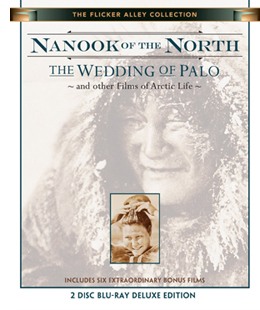

Nanook and friends

Early this year we posted our annual list of the ten best films of ninety years ago. It featured the classic early documentary, Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North. In March our friends at Flicker Alley released a two-disc Blu-ray edition of Nanook paired with the 1934 Danish feature, The Wedding of Palo (Palos Brudefærd). The latter is one of those titles that one occasionally encounters on the fringes of older historical surveys, but it has been difficult indeed to see. This new print is a 2012 restoration from a George Eastman House original 35mm nitrate copy.

Nanook is familiar enough, but The Wedding of Palo is not. It was made by the Danish explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen, who appears in a brief introductory passage. Clearly he was influenced by Flaherty’s work. He combines a simple fictional narrative with documentary scenes of traditional Inuit life in eastern Greenland. The basic story involves the heroine Navarona, whose brothers are reluctant to lose their housekeeper by allowing her to marry. Two men of the tribe court her and come into violent jealous conflict. Interjected are sequences of a salmon hunt, a festival, a traditional song duel between the two rivals, and a polar-bear hunt. The staged dialogue scenes involve sound recording, with no subtitles but the occasional brief intertitle to translate.

Nanook is familiar enough, but The Wedding of Palo is not. It was made by the Danish explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen, who appears in a brief introductory passage. Clearly he was influenced by Flaherty’s work. He combines a simple fictional narrative with documentary scenes of traditional Inuit life in eastern Greenland. The basic story involves the heroine Navarona, whose brothers are reluctant to lose their housekeeper by allowing her to marry. Two men of the tribe court her and come into violent jealous conflict. Interjected are sequences of a salmon hunt, a festival, a traditional song duel between the two rivals, and a polar-bear hunt. The staged dialogue scenes involve sound recording, with no subtitles but the occasional brief intertitle to translate.

As in Nanook, the non-professional actors are remarkably natural, especially the “actress” portraying the heroine. There is a cute young boy brought in at intervals for comic appeal, and the members of the village seem always to be laughing and enjoying a suspiciously carefree life. The film has the advantage of more spectacular scenery than that in Flaherty’s film, with huge mountains and glaciers in place of the vast ice-covered vistas (see bottom image).

As usual, the Flicker Alley team has gone beyond the call of duty with this release. It includes not only the two features, but six bonus films, as described in the press release:

Nanook Revisited (Saumialuk) by Claude Massot was made in the same locations used by Flaherty. It shows how Inuit life changed in the intervening decades, how Flaherty consciously depicted a culture which was then already vanishing, and how Nanook is used today to teach the Inuit their heritage. Nanook Revisited was produced in 1988 on standard definition video for French television. Dwellings of the Far North (1928) is the igloo-building sequence of Nanook re-edited and re-titled as an educational film; Arctic Hunt (1913) and extended excerpts from Primitive Love (1927) are by Arctic explorer Frank E. Kleinschmidt; Eskimo Hunters of Northwest Alaska (1949) by Louis deRochemont shows many activities seen in Nanook thirty years after, and Face of the High Arctic (1959) depicts the ecology of the region, produced by the National Film Board of Canada.

Altogether, the films run an impressive 281 minutes. There’s also a booklet with excerpts from Flaherty’s book, My Eskimo Friends, an essay by Lawrence Millman, “Knud Rasmussen and The Wedding of Palo,” and notes on the films.

Snow White and the Seven (?) Bullfighting Dwarves

In 2011, a French film, The Artist, gained huge attention in the infotainment media as a modern version of silent cinema, winning yet another Best Picture Oscar for the Weinstein brothers. It was a reasonably successful imitation of mid- to late 1920s cinema during the transition to sound. Now a much better modern silent film has arrived, Pablo Berger’s Blancanieves, a loose version of the Snow White story transposed to 1920s Spain. A famous bullfighter is paralyzed after being gored in the ring. His wife dies in childbirth and his scheming nurse marries him. She keeps his daughter, Carmen, away from her father by setting her to work as a downtrodden servant in his country estate. Upon her father’s death, the evil wife schemes to have her killed, and she escapes to the protection of a troupe of six bullfighting dwarves who, possessing uncertain arithmetic skills, bill themselves as seven bullfighting dwarves.

While The Artist was a fairly good imitation of 1920s Hollywood filmmaking, Blancanieves is a pastiche of the 1928-29 era of European silent cinema. It draws on what I have termed the International Style of filmmaking, a late 1920s blend of influences from the French Impressionism, German Expressionism, and Soviet Montage movements. One could almost pass it off as a genuine film of the era.

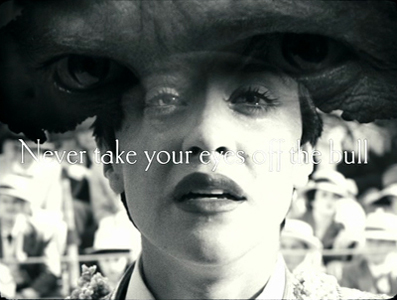

At times there are subjective effects à la Impressionism. A superimposition conveys Carmen’s memories of her father’s crucial instructions to her, and superimposed images of hands waving handkerchiefs present the enthusiam of the crowd’s plea for the bull to be pardoned.

This was also the period in which the power of the wide angle lens, particularly in close-ups and in low-angle shots, was exploited, initially in Soviet cinema and then all over Europe. Blancanieves is full of such shots, as in the frame at the top of this entry and in these two shots from the opening scene:

There are also montage sequences, building up to flurries of very short shots. This accelerated-editing technique is typical of both Soviet and French filmmaking of the era.

The too-frequent use of handheld camera in Blancanieves detracts somewhat from the feeling of authenticity. In the late 1920s, cameras were too heavy to be handheld. They could be strapped to the body of the cinematographer with harnesses, but that creates a subtly different look. And during the late 1920s, shots with the camera holding on a character while the background spins around behind him or her would have been achieved by placing both camera and actor on a large turntable. (This effect apparently was pioneered in Germany in the mid-1920s). But the occasional dramatic lighting effects, particularly in the climactic scene, are distinctly reminiscent of German cinema.

In general, the narrative is charming and amusing. The heroine’s pet rooster provides exactly the sort of comic relief that is common in films of the 1920s, and the story has an effective fairy-tale quality. I found the ending a bit disappointing and certainly not typical of the films of the 1920s. Still, Berger has clearly watched an enormous number of 1920s European films and absorbed their styles. He can imitate the International Style remarkably well, telling a tale that is appropriate to the 1920s and yet has a touch of humor that doesn’t belittle the silent era.

Blancanieves was released in the US on March 29 and is currently making the rounds of art-houses and festivals.

Other entries discussing the International Style and wide-angle filming at the end of the silent era can be found here and here.

The Wedding of Palo

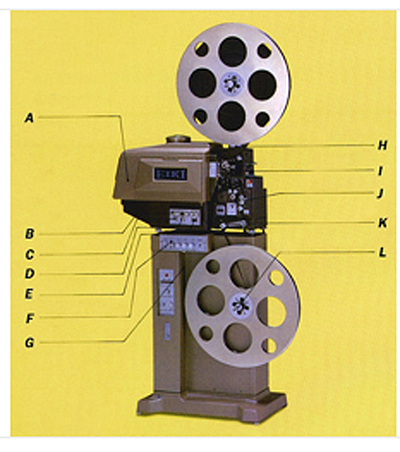

16, still super

From Lost & Found Film Club.

DB back:

While I was semi-snowbound in Evanston, IL, messages kept rolling in. Many of them were responding to my account of surrendering my 16mm movies and gear. That post’s whiff of nostalgia was caught by Gary Meyer, co-director of the Telluride Film Festival.

Don’t get me started on 16mm memories. I started showing movies in 8mm at about ten years old and by thirteen I had two for changeovers on silent classics rented from Cooper Films in Chicago. For about $2 I got a full feature and short including postage. Using my parents’ record collection I could score the films. . . .

Graduated to 16mm in high school when a local church and the library each offered use of their projectors and I started collecting prints seriously. In college I got a job in the media center showing films, cleaning prints and projectors. When the department decided to buy Bell & Howell Auto-Shreds, they sold off the old projectors for $50. I knew each machine intimately and selected the quietest, gentlest RCA 400 which I still have in a booth in my basement. One of my favorite projectors.

With 16mm projectors I have shown movies on garage doors from my apartment, in a barn, an orchard or two, and most famously on clouds, which resulted in the police department getting many phone calls about aliens.

Gary reports that his former venue, the Balboa Theatre, has given its theatrical Eiki projector to the San Francisco State University film department, but it can be borrowed back if ever needed. A more acute sense of the passing of an era was reported by program curator and Czech arts consultant Irena Kovarova:

One of the sad moments in my film history was being invited to the Czech Embassy in Washington, DC to visit a room of 16mm film piles. I was asked to pick and choose which ones should be saved and which would be chucked away (the majority). It was a collection of films that the Embassy inherited from the Communist-era offices when the staff was shipped films for their entertainment (Czech popular comedies) and of course tons of “travel” and “propaganda” stuff. It was impossible to know what was really there and a lot was mediocre, but still such a sad thing that no one could really dig in and explore.

Secrets of the Incas, and non-Incas

Projection booth, Cleveland Cinematheque.

But there was good news too. In the course of that entry, I said that 16 was “nearly dead” as an exhibition format. Trust this blog’s alert readers to give a more upbeat emphasis and offer some weighty counterexamples. Don’t hesitate to use the hyperlinks!

I was confirmed in my belief that archives will keep the format going. I hear from our old friend Antti Alanen of the National Audiovisual Archive of Finland, that 16 flourishes in Helsinki.

We still keep screening 16mm regularly at Cinema Orion, and for the moment print access is still good. We recently showed three programs of Stan Brakhage movies (from Canyon Cinema) and one programme of Rose Lowder movies (from Light Cone of Paris), all in the original format of 16mm, all prints and colours perfect.

I haven’t seen Brakhage on DVD, but those who have remarked that it is not the same thing. There is something about the special sensuality of 16mm which is essential to the Stan Brakhage experience. All of those films fill up the senses.

Besides Canyon Cinema and Light Cone, LUX in London still seems to be well-stocked with good 16mm prints in commercial distribution.

Bracing news. Antti mentions as well that he used to be able to access 16mm films made for the Finnish Broadcasting Corporation, but now the agency has realized that the prints are irreplaceable and provide digibeta copies instead. The loss for showing is a gain for preservation.

I indicated as well that colleges, universities, and museums will probably maintain 16mm prints and showings. My correspondents have confirmed it, and offer some ripe local detail. Tracy Stephenson of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, tells me that they have shown films since the 1930s and may be the only venue in Houston that still screens 16. They have a program of jazz shorts coming up in June.

Here’s John Ewing of Cleveland:

I still show 16mm on occasion (and two-projector 16mm at that) at both of my venues: the Cleveland Cinematheque and the Cleveland Museum of Art. In fact, I just ran the 16mm program from the 50th Ann arbor Film Festival tour last Thursday night at the Cinematheque. Last time I showed 16 at the art museum was in December when we screened an IB Tech print of Secret of the Incas, from the Academy Film Archive.

From the Oklahoma City Museum of Art, Brian Hearn writes:

We are pretty serious about 16mm and maintain a modest collection of about 500 prints, ranging from Lumiere Brothers shorts to studio features to avant-garde to educational films to 70s exploitation trailers. As the film medium dematerializes it makes me appreciate our collection even more, vinegar and pink fading prints included!

Calling a collection of 500 titles modest makes me grin (in envy). On the university side, Jon Vickers supplies other breathtaking information:

Indiana University Cinema programs from the University’s 16mm collection on a regular basis, with 16mm screenings at least once each month. In the IU Libraries Film Archives, there are over 80,000 items, the majority being 16mm. Within that collection is Lilly Library’s David Bradley Collection, spanning the history of cinema in the US and Europe, including classic, obscure, and some unique titles. We dedicate a series each semester to the holdings within the Bradley Collection (programmed by Film and Media Studies grad students), as well as program from the educational/non-theatrical collections and holdings.

We can’t imagine a day when we will stop screening 16mm.

With that treasure house, I can see why! Pablo Kjolseth of the University of Colorado at Boulder also defends the format resolutely. Pablo has written one of the most fiery and persuasive polemics on digital cinema. Not only does his program have an extensive library, but they are still actively collecting in 16. Moreover, as home to the annual Brakhage Center for Media Arts symposium on experimental film (coming up next week), Boulder’s campus relies constantly on 16.

Hipsters, nostalgics, and toddlers

Eiki EX-9100 Professional 16mm Sound Optical/Magnetic projector with 2000-watt lamp. Currently available on eBay for $8,500.

Perhaps the most cheering news comes from those enterprising programmers of films for public venues, both for-profit and not-. Barak Epstein of the Texas Theater uses Kodak Pageants (of my fond memory) with manual changeovers and a manual audio fader. Pittsburgh Filmmmakers, writes Gary Kaboly, uses its Kinoton and Eiki machines every couple of months. He adds:

Throwing around the idea of a “classic 16mm experimental” series in the fall. Young Hipsters see attending a 16mm show as an “event.” Old Hipsters always describe what an Art House was “back in the day.”

The Cinefamily venue of LA has established itself as home to what the local paper called “pathologically idiosyncratic programming,” and 16 adds sharp spice to the mix. Here’s Hadrian Belove, the Head Programmer, on his personal quest and the formation of the Lost & Found Film Club:

I’m definitely of an age that would be post-16mm collecting, but still got hooked. One of the great appeals of 16mm for me is it feels like the final frontier for discovering true rarities. . . . It’s kind of the ultimate format for a “digger.” Finding Christian experimental films, industrial films, student films, and copies of TV movies, episodes, and even theatrical features that simply never made it to any form of video is de rigueur.

Nothing gives me more pleasure as an explorer than trolling eBay for 16mm.

I began showing things I would buy after hours to the staff here at Cinefamily, and hadn’t even considered it as a public show. Over time, some of the “kids” on the staff started buying their own 16mm ephemera, and finally proposed taking our private show public. I thought what the hell, cost is low, and we were doing it anyway. I gave them a terrible time slot I wasn’t using (10:30 on a Wednesday).

They launched this:

https://www.facebook.com/LostFoundFilmClub

Anyway, the first show had 100 people, even at 10:30 on a Wed night. Maybe it’s those grilled cheese sandwiches!

Finally, I had noted that FOOFs (Fans of Old Films) had a noble tradition of gathering in annual conventions. Jessica Rosner, film scout extraordinaire, writes of screenings at the upcoming Syracuse Cinefest: “The majority of films will STILL be in 16mm and they will be films that are rarely available to be seen any other way.”

A further note from Pablo Kjolseth brings things back to Gary Meyer’s childhood and the FOOF in us all. Pablo hosts summer screenings in his back yard.

My Eiki Xenon projector shoots through a guest-room window to the screen in the backyard – transforming the guest room into a “projection booth” of sorts. The next [picture] is a nice ominous shot of Darth under stormy skies. . . . Although I’ve played around with some digital screenings, everyone prefers the 16mm shows. And this even though I don’t do reel-changes or employ a take-up tower – thus having small intermissions between each reel change. These intermissions are quite popular, as it allows folks time to refill their drinks, go to the bathroom, and comment on what they’ve seen so far.

As many as 60 people might show up for any screening. As the children in the neighborhood are always entranced by the projector, I try to make sure to have a couple family-friendly screenings every summer. My neighbors are great: they’ve even tolerated backyard screenings of such titles as DAWN OF THE DEAD and THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE – admittedly poor choices, given that in the summer heat most people sleep with their windows open and late at night they might not appreciate all the screaming and, well, chainsaws. But, so far, no complaints!

None from my end, either. Is it just me, or does Darth look more menacing here than in any other setting?

After reading these communiqués, two thoughts. First, a great many programmers are working very hard to track down and screen unusual items for their audiences. These folks and their peers are committed to exploring cinema along routes that bypass the multiplex. Who wouldn’t rather watch Secret of the Incas than, say, The Last Exorcism Part II?

My second thought comes with a pang. Was I wise to clear out my 16 collection? Our department and other collectors benefit, but still… A basement will dry out, but films that are gone are gone.

Thanks to all who wrote me, and to the Art House Convergence list serve for its stimulating conversations.

Tony and Theo

Man on Fire (Tony Scott, 2004); The Suspended Step of the Stork (Theo Angelopoulos, 1991).

DB here:

In January of 2012, while shooting The Other Sea, Theo Angelopoulos was struck by a motorcyclist and died soon afterward. In August, Tony Scott committed suicide by jumping off Los Angeles’ Vincent Thomas Bridge.

Both men mattered to cinema. But which cinema?

From 1970 onward, Angelopoulos produced solemn films about Greek history, world war, emigration, and the collapse of struggles for political change. His hallmark was the extended—some said excruciating—long take. He presented his work as that of a thoughtful and passionate intellectual, a witness to history (or as he sometimes said, History) who was telling us hard, melancholy truths. His work received little mainstream distribution outside Europe and Japan, and some of his best films weren’t circulated nontheatrically or on video. Severe and abrasive, he alienated powerful members of film culture and was reported to have responded sourly when he did not win Cannes’ top prize.

By contrast, after Top Gun (1986), Tony Scott came to be the prototype of the ADD Hollywood director, a master of the blockbuster action picture. He gleefully marshaled visceral technique to jolt the eye and hammer the ear. His movies were unabashed booty calls, spotlighting female pulchritude in a tone of laddish camaraderie in an all-male milieu (sports, the military, the workplace). Not lacking intelligence, he avoided the sweeping pronouncements that made Angelopoulos look pretentious, but his early partnering with Simpson and Bruckheimer stamped him as raucously vulgar. He even dated Brigitte Nielsen.

Extremes meet

Déja vu (2008); Eternity and a Day (1995).

The statuesque versus the kinetic, the monumental versus the ephemeral, ponderousness versus cheap flash: To all appearances, these men lived in different cinematic worlds. Their careers were oddly counterpointed too. Angelopoulos, a festival darling in the 1970s and 1980s, became more unfashionable. By the time of his last release, The Dust of Time (2009), some critics were openly scornful. Scott faced gibes from the start but won some critical respect in the 2000s. After his death, critics were calling him a master. To many, Angelopoulos’s stubborn allegiance to 1970s modernism looked old hat, while Scott’s bodaciousness and eye candy seemed to have finally seduced audiences and critics alike.

I confess that both give me qualms. When Angelopoulos strains for significance, as he does at many moments throughout his oeuvre and almost constantly in The Dust of Time, he arouses all my impatience with pretentious Eurocinema. When Scott builds a scene out of Fuck-you-motherfucker dialogue and lingering views of pole dancers he reminds me of just how low contemporary American cinema can sink. And the style of each one can become predictable–an angled shot down a street portends a pan in Angelopoulos, while once somebody sits down in a Scott movie the camera is likely to start to twirl.

Despite these misgivings, I find that I can admire and enjoy both men’s films quite a lot. Their most venturesome work offers us powerful experiences, and they can teach us things about cinema—not least, how creative filmmakers can rework the medium and its historical traditions.

And their worlds overlap at least a little. Both men treat cinema as an art of scale. To see Man on Fire (2004) or Alexander the Great (1981) on home video, no matter how big your monitor, is to shrink the films fatally. Correspondingly both men relied on spectacle, stuffing the screen with sweeping, startling effects. True, Scott’s spectacle is maximalist, while Angelopoulos’s is austere. Yet once you’ve calibrated your bandwidth, the train that rumbles through the migrant camp in The Weeping Meadow (2004) becomes no less rattling than the rogue locomotive in Unstoppable (2010). “Go big or go home” might be each man’s motto.

Both play games with narrative as well. As early as The Hunger (1983) Scott’s incessant crosscutting uses the soundtrack of one line of action to comment on another. The time looping of Domino (2005) and Déja Vu (2008) creates flashbacks, replays, revised outcomes, and jumping viewpoints. More sedately, Angelopoulos perfected the time-shifting long take. The camera movements of The Traveling Players (1975) glide among different eras. From scene to scene, Angelopoulos will provide few marks of tense. Scene B may follow A, or precede it by several years, and no Hollywoodish superimposed title will help us out. It may be several minutes before we realize that decades have passed.

Yet the time-scrambling both directors enjoy isn’t wholly at the service of drama. Storytelling takes on a curiously subsidiary role in their work. Neither filmmaker, it seems to me, is centrally interested in probing what many of us take to be the core of narrative—character psychology. This isn’t to say there aren’t poignant moments and glimpses of inner lives. But each director also leaps beyond them.

I think in fact that Tony and Theo explore what happens when narrative slips away, when cinematic textures and patterning are allowed to override drama—to inflate it, deflate it, thrust it to one side, take it as a pretext for something more tangibly enthralling. Both filmmakers seek to shape our perception and emotion, letting the fluctuations of images and sounds engender a kind of mesmeric attention in themselves.

They accomplish this within two different traditions, that of modern Hollywood and that of “art cinema.” Yet they share a commitment to going beyond the given: Each director pushes his tradition to a limit.

Pulp fictions

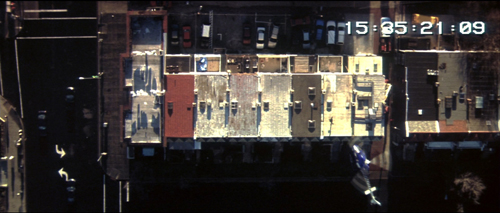

Déja vu (2008).

Scott’s tradition is, most broadly, Hollywood narrative cinema, and up to a point he plays along. The plots are propelled by goal-directed characters who clash with others, and the results are contests (Top Gun, Days of Thunder, 1990), investigations (Beverly Hills Cop II, 1987; Man on Fire, Deja Vu), pursuits and conspiracies (Revenge, 1990; The Last Boy Scout, 1991; True Romance, 1993; The Fan, 1996; Enemy of the State, 1998; Spy Game, 2001; Domino), and ticking-clock suspense situations (Crimson Tide, 1995; The Taking of Pelham 123, 2009; Unstoppable).

At the center there usually stands one man, or a duo, who must undergo a test of courage and resourcefulness. In The Fan, an example of what Kristin has called the parallel-protagonist movie, a normal guy finds himself pursued by an obsessed admirer. A woman might serve as a gutsy partner, as in True Romance, or the object of the quest (Revenge, Spy Game), or the reward for success (The Last Boy Scout, Unstoppable). Only Domino has a female protagonist who survives through being as abrasive, dirty-minded, and foul-mouthed as her male partners and adversaries. Yet by her own admission, she has daddy issues and a longing to return to cozy wealth.

At bottom, then, Scott worked with straightforward pulp stories, and for about a decade he played them in the proper spirit. But with Enemy of the State (1998) he began to use the slipperier narrational strategies spreading through Hollywood of his time. Like Tarantino, who supplied the script of True Romance, Scott became willing—inspired, he suggests, by rock’n’roll and the films of Nicholas Roeg—to go a little wild.

His scripts started playing with what we usually call point of view. Some films become markedly, not to say traumatically, subjective. Spy Game splits the protagonist figure into two and gives us each one’s standpoint on the action. The Fan, from Peter Abraham’s fine novel, tracks a man’s obsession as it turns deadly. Man on Fire plunges into John Creasy’s mental world as he distills pain, guilt, piety, and alcoholism into a merciless sadism.

By the time we get to Domino, story presentation is pitilessly disjunctive. The main action is bracketed by a conventional frame showing the heroine telling her story to a police officer. A good thing, too; we couldn’t follow the action without her commentary. The tale fractures into quickfire AV displays, with pauses, backing-and-filling, alternative outcomes, and even written titles, as if we were getting the most juice-jangled PowerPoint talk in history.

Another multiplication of perspective takes place via spy games. Most directors situate modern surveillance techniques within their story world; Paul Greengrass seems happiest shooting people bent over workstations. When your average director gives you a swooping helicopter shot, you don’t take it as the POV of a sinister government agency or a sensationalistic TV livecam. In Scott’s late films you’re likely to. He realized that all today’s security cameras, cellphones, and hostile eyes in the sky can do two useful things. They can chop story space and time into teasing fragments, and they can refresh the shot’s visual texture.

For quite some time Hollywood movies have used television for exposition. Characters tap into the flow of story events via TV broadcasts, and sometimes, as in The Siege (1998), the film simply cuts in news clips presented directly to us, without any mediating character. Passages like these, a contemporary equivalent of the newspaper headlines and radio broadcasts of classic studio cinema, usually smooth out the plot, linking things concisely.

But Scott takes pleasure in playing up the disparities among the footage, cutting from “direct” presentation of material to mediated images and sounds. In the conspiracy films, the video images seem to be coming from a vast image bank or database that the film is sampling on the fly. Moreover, the constant interruption of one shot by another, seen on computer or news broadcast or spycam, creates a nervous visual narration. In effect, Scott imports the mixed-format collages of Stone’s JFK (1991) into the action film (with more skill than Stone summoned up for Natural Born Killers of 1994 and U-Turn of 1997).

At the level of presentation, though, a narrower tradition shapes Scott’s style. In interviews and director commentaries he ceaselessly reminds us that he started out as a painter, and he has, I think, brought a fresh pictorial intelligence to the action film.

Too much is not enough

Days of Thunder (1990).

Like Michael Mann, Scott seems to have felt the need to give the action picture a dose of self-conscious artistry. The problem was the competition. The gold standard of the genre emerged in 1988 with the poised, tightly-woven classicism of John McTiernan’s Die Hard. How was an ambitious director to match that? Most directors were embracing variants of a style I’ve dubbed “intensified continuity”—fast cutting, simple staging, polar extremes of lens lengths, almost constant camera movement. The efficient but routine Richard Donner and Renny Harlin worked along these lines, while Michael Bay represented the style in almost pristine form. But what if a director who had trained as a painter at the Royal College of Art could take intensified continuity into new territory?

So yes, go along with the trend toward fast cutting; but make it even faster. In an era in the average shot in the average film runs between 3 and 5 seconds, why not make them 2 seconds? Or less? This was Scott’s choice from The Fan (1996) on. He seldom repeats a setup, largely because he has so many cameras stationed on the perimeter of the scene. Man on Fire contains at least 4100 shots, Domino over 5000, but perhaps we will never know just how many. Long passages are built out of multiple exposures, superimpositions, stop-and-go motion, and color shifts within a “shot.” The cut ceases to be a firm boundary as layers float up and slip away.

At times Scott, like Vertov in Man with a Movie Camera and Pat O’Neill in Power and Water, simply abandons the concept of a discrete shot, letting images seep through his frame.

And yes, move the camera; but move it in arabesques quite different from McTiernan’s unfussy following shots and tense track-ins. In particular, take the swirling camera as a given but then pivot your subject a bit as well. Cutting from one rotation to another can yield a little ballet of sculptural solidity, with barriers gliding by in the foreground and bursts of tonal values throughout. Here’s an example from Unstoppable.

In the 1980s and early 1990s films, Scott mixed haze and sharpness. Some scenes would be shot in metallic or earth tones and swathed in those smoky layers brother Ridley had popularized in Blade Runner. Other scenes would boast silhouettes, crisp edges, and blocks of bright color. Consider these images from Revenge, The Last Boy Scout (2 frames) and True Romance.

All framings–long-shot, medium-shot, close-up–tend to be covered by several cameras with very long lenses, which flatten and abstract the image. Later, having discovered the power of cross-processing reversal stock, Scott mostly gave up haze for what he called hyperrealism: high contrasts, along with Hockneyish color ripeness and thick but still transparent shadow regions.

Scott adds to the canons of intensified continuity the punch of the axial cut, that shot change that yanks figures toward or away from us (an effect that his last films mimicked by snap-zooms). Combined with long lenses set at various distances, this option creates a sense of constantly losing and refinding the point of the shot. As Connie swivels during a later stretch of the Unstoppable scene, the axial cut with different backgrounds pins her against varied blocks of color.

Critics complained that Scott’s style reminded them of MTV videos and commercials, a great number of which the Scott brothers produced. But there’s nothing inherently wrong with filmmakers drawing inspiration from advertising (as painters like Warhol and Stuart Davis did) or from video clips (as Wong Kar-wai seems to have done). What matters is what you do with your sources. It seems clear that Scott subjected these techniques to a new pressure, using them to thrust current norms to new extremes.

Intensified continuity, as I argued in The Way Hollywood Tells It, offers a mannerist version of classic continuity. If that’s accurate, then we might say that Scott provides a Rococo variant of intensified continuity itself. Michael Mann, another pictorialist, is more of a purist, seeking a sober gravity, while Scott doodles and scrawls across the surface of his scenes. Not only does he interpose reflections, rain, dust, and other particles between his subjects and us, but he reiterates lines of dialogue via supered titles.

Mann lets us soak up his images, but Scott tosses out one gorgeous composition after another in bewildering profusion. In the accelerated late films, they barely have time to register. The film seems to whisk away under our eyes. Shots lack an organic arc; they’re lopped off. Partial impressions pile up, defeating our urge to dwell on a composition. Sometimes you can’t trust your eyes. During the kidnap scene of Man on Fire, a thug prepares to shoot back at Creasy as a burst of flame is reflected in his car.

Problem is, nothing has caught fire in the scene; for once, no explosions. It’s purely a crazy jolt, literalizing the idea of a “firefight” without any realistic motivation.

These techniques are motivated to some degree by story demands: the need to suggest a mental state, to portray a heroic posture, or to amp up a fight or chase. But Scott’s visual and auditory handling exceeds the demands of clear storytelling. He wraps the most perfunctory dialogue scene in a dazzling embroidery that arrests attention in its own right. Mere decoration? I’d agree. Still, decorative art isn’t an unworthy calling, and decoration pursued with conviction and inventiveness demands our notice.

And this decoration isn’t dainty. Domino, Unstoppable, and the second half of Man on Fire have a grunge dimension, with shots that make our world look at once harsh and dazzling. Scott could be our Sam Fuller (complete with cigar), and Domino could be his Naked Kiss. Fuller might echo Scott’s gaffer, who said of Domino: It isn’t pretty, but it is beautiful.

Threnody

Ulysses’ Gaze (1995).

From The Birth of a Nation to Lincoln, American studio cinema tends to show grand historical events intertwining with the private dramas of great leaders or common folk. But there were other options. Eisenstein’s first three films—Strike, Battleship Potemkin, and October—floated the possibility of the “mass protagonist.” In these films, history is made by groups, and individuals are given largely symbolic roles. During the politicized 1960s, this model was taken up by filmmakers on the left.

The filmmaker who explored this option most fully was the Hungarian Miklós Jancsó. Although his films seem to be little-known today, he was a major force in reviving the idea of presenting history through group dynamics. Individuals play a role in The Round-Up (1965), Silence and Cry (1968), and The Confrontation (aka Bright Winds, 1969), but they are usually bereft of personal psychology. These figures are defined by their roles in a struggle—a civil war, a revolution, a clash with a domineering regime—and they are often pawns in a game of shifting power.

The Red and the White (1967), available on DVD, is a good example. This saga of the Russian Civil War that followed the 1917 revolution takes us through skirmishes between clashing armies, the tactics pursued by a squadron of Hungarian volunteers, and episodes in a Red Cross station. Individuals come to the fore briefly but are likely to vanish from later scenes, or simply die on the spot. One young Hungarian threads his way through the action, but he can hardly be said to be a point-of-view character, and we learn nothing of his background or motives. A great deal of the film is taken up with rituals of questioning prisoners, torturing and shooting captives, and ravaging innocents caught in the crossfire. At the climax, a tattered Red unit marches defiantly toward a superior White force, the entire confrontation played out in a stupendous landscape.

The Red and the White could defend itself from charges of formalism through its affinity with Soviet-style war dramas, but as Jancsó went on to examine episodes in Hungarian history, he soon gave up realism. He staged historical events in symbolic forms, on a bare plain or as obscure rituals in festivals rippling with music and dance. Examples are Agnus Dei (1972), and Red Psalm (1969; available on DVD). These films relied on endlessly tracking, craning, and zooming; the camera floats, and space stretches and squashes. The result was long-take extravaganzas. The Red and the White has fewer than two hundred shots; The Confrontation (1969) only thirty-five; Sirocco (1969) and Elektra, My Love (1974; on DVD) fewer than a dozen.

It seems to me that after Angelopoulos’s first film, he picked up and expanded Jancsó’s idea of investigating a nation’s history through mass dynamics and stripped-down spectacle. He proceeded more or less chronologically through modern Greek history. Days of ‘36 (1972) examines the dictatorial rule of General Metaxas (1937-1941) while The Traveling Players of 1975 covers the Nazi occupation and postwar civil strife. The Hunters (1977) revives the years from the civil war (1944-1949) to the mid-1960s through an arresting narrative device: present-day hunters find the corpse of a civil war partisan, as fresh as if killed yesterday. Alexander the Great (1980) doubles back to a period from the turn of the century until the 1930s, showing a bandit taking power over a remote village.

This tetralogy did pick out individuals, but it made them symbols of larger forces, often through names drawn from history or mythology. The travelling players are named Electra, Orestes, and the like; Alexander the bandit is a brutish version of his legendary namesake. Nevertheless, Angelopoulos’ presentation did little to acquaint us with them from the inside. He drew on none of Scott’s subjective tricks to convey instant impressions or fragments of memory; even his quasi-subjective flashbacks were likely to include the protagonist as he is today in the scene from the past.

Popular filmmaking depends on our accessing characters’ thoughts and feelings, but Angelopoulos largely gave that up. He made his plots depend on large-scale political forces. Sometimes, as in Days of ’36 and The Hunters, we are taken behind the scenes and shown the machinations of power, but usually history unfolds through impersonal forces—often outside the frame. When the apparatus of power is made visible, it’s through visions of police, soldiers, or other authorities. And those are often presented as rigid and impersonal.

Below, in Ulysses’ Gaze, a candlelight march is confronted by row upon row of police. The calm, mechanical way the officers fill up the middle ground makes the impending conflict quite suspenseful. When you think the composition, and the confrontation, have exhausted the shot’s duration and space, a crowd of citizens appears in the foreground to bear witness. All three groups are made into homogeneous blocks through the distant framing and the consistency of texture (flickering candles, uniforms, umbrellas).

The drama comes when our characters are forced to respond to the forces of oppression. They flee, they hide, or they’re captured and sent to prison or execution or exile. It’s an inglorious version of history, filtered through a Brechtian belief that distancing us from charged situations, presenting emotions dryly rather than melodramatically, can bring lucidity and a grasp of macro-dynamics. But Angelopoulos also traced his the origins of his oblique, sometimes opaque style to the pressures of censorship. Under the Greek junta, it was impossible to speak about history directly.

So I sought a secret language. Tacit understanding of the story. The temps morts in plotting a conspiracy. The unsaid. Elliptical discourse as an aesthetic principle. A film in which everything that is important takes place outside the frame.

Even after censorship ceased, Angelopoulos continued in this taciturn vein, making his films thoroughly decentered and dedramatized.

Yet in the 1980s, he tried to offer audiences more. He began to put distinct and individualized characters at the center of his films, and he achieved his survey of political change by sending them on modern Odysseys. In Voyage to Cythera (1983) a film director is conceiving a new project, and he visualizes the story of an elderly Communist let out of prison and returning to his village. In The Beekeeper (1985), a schoolteacher abandons his family and embarks on a trip across a bleak modern Greece. Landscape in the Mist (1988) follows two children convinced that their emigrant father is waiting for them just across the border. In The Suspended Step of the Stork (1991) a television journalist tracks down a prominent politician who seems to be hiding in a refugee village.

Two 1990s films plumb the characters’ pasts in more detail. Ulysses’ Gaze (1995) follows an archivist (called simply A) searching for a lost film and his own family history in the Balkans. In Eternity and a Day (1998), a poet in the last days of his life reflects on his life while accompanying a boy trying to return to Albania.

In the 2000s Angelopoulos began again thinking on an epic scale. Trilogy: The Weeping Meadow (2004) announced itself as the first installment in nothing less than a history of the twentieth century told through the experience of a single family. Concentrating on a refugee couple—one Russian, one Greek—it sets their fugitive romance against the events of World War I, the rise of Fascism, and the Greek Civil War, while also hinting at parallels to Attic tragedy. The second installment, The Dust of Time (2009) runs parallel to Voyage to Cythera and Ulysses’ Gaze in centering on a filmmaker, but he becomes less central to the plot than his father, his mother, and his mother’s lover–all victims of 1950s Soviet Communism who survive to see the fall of the Berlin wall.

Over these years, Angelopoulos collaborated with the Italian screenwriter Tonino Guerra (who died about two months after the director). Guerra, who worked with Antonioni, Fellini, the Tavianis, and many other directors, may have helped turn Angelopoulos toward less forbidding storytelling. The more vividly drawn protagonists of the late work were often played by well-established actors (Mastrioanni, Moreau, Ganz, Keitel, Dafoe, Piccoli), and two of the films center on children, one common way to kindle emotion. Eleni Karaindrou’s scores, full of threnodies rising up from massed strings, by also gave the films after Cythera a plangent warmth reminiscent of doleful musical pieces by Henryk Górecki and Arvo Pärt.

Still, these late films are only comparatively more accessible. Their stories come across as downbeat, episodic, relatively empty of conventional drama, full of “dead time” and unmarked time shifts, and deeply somber. Which is to say that they belong to the broader tradition of postwar European art cinema, its norms given fresh realization through echoes of Greek mythology and a signature style of exceptional rigor.

Stasis and sublimity

Alexander the Great (1981).

At the level of technique Angelopoulos again emerges as a synthesizer. An admirer of Mizoguchi and Antonioni, and again probably influenced by Jancsó, he became identified with the long take. From The Traveling Players on, scenes are presented in very few shots, often only a single one. Three films of the tetralogy contain between 125 and 150 shots, while The Hunters makes do with 49. And most of the films are very long (two nearly four hours), so the average shot length runs from 72 seconds (Days of ’36) to 206 seconds (The Hunters). As the later films became more accessible, the editing paced quickened only a little: no film has more than a hundred shots, and in all the average shot runs between fifty seconds and two minutes. Add together all the shots in Angelopoulos’ thirteen features and you have less than a third of the shots in, say, Scott’s Enemy of the State.