Archive for the 'Art cinema' Category

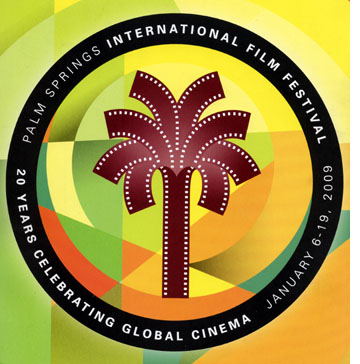

Sitting under a palm tree made of film

Jerusalema.

Kristin here–

The Palm Springs International Film Festival has a logo calculated to appeal to those of us who travel from snowy northern climes to attend: a palm tree composed of strips of film. As each film began and a short prologue listed the sponsors, I studied that logo and felt grateful that I was missing the frigid weather that descended upon Madison during our absence. It’s a clever design, also managing to suggest movies springing forth in abundance, which was certainly true of the festival’s offerings.

The Palm Springs International Film Festival has a logo calculated to appeal to those of us who travel from snowy northern climes to attend: a palm tree composed of strips of film. As each film began and a short prologue listed the sponsors, I studied that logo and felt grateful that I was missing the frigid weather that descended upon Madison during our absence. It’s a clever design, also managing to suggest movies springing forth in abundance, which was certainly true of the festival’s offerings.

Two from the Antipodes

Most New Zealand films are set in their home country, taking advantage of its magnificent landscapes and local culture. Dean Spanley (Toa Fraser) strikes me as quite different. Based on a Lord Dunsany fantasy novella, My Talks with Dean Spanley (1936), it was mostly filmed in England and is a costume piece set in the Edwardian era. Five years ago co-productions were rare things in New Zealand, but this is a Kiwi-U.K. film with an impressive international cast. There are Englishman Jeremy Northam as the narrator and protagonist, New Zealander Sam Neill in the title role, Australian Bryan Brown (perhaps most widely known as Breaker Morant) in a supporting part, and Peter O’Toole. The latter is spoken of as a possible best supporting actor Oscar nominee, though I fear that the film is too low profile for that.

[Correction, January 26. Bryan Brown appears in Breaker Morant as Lt. Peter Handcock, not in the title role.]

Dean Spanley is a feather-light but well-told tale of Fisk, a middle-aged man who pays a tense visit to his  curmudgeon of a father (played by O’Toole) once a week. For something to do, Fisk takes the old man to a lecture on reincarnation, also attended incongruously by the local preacher, Dean Spanley. A friendship develops between Fisk and Spanley as it gradually comes out that Spanley seems to be the reincarnation of the father’s beloved childhood dog. The premise is made plausible by a gradual revelation of the premise, by Neill’s performance, and by some lyrical flashbacks. The whole thing is a surprising film to have come from Fraser, whose first feature, No. 2, was set in Auckland and concerned a family of Fijian descent. Yet it seems a sign of the New Zealand cinema’s health that he could take such an unexpected turn and tackle an English literary adaptation.

curmudgeon of a father (played by O’Toole) once a week. For something to do, Fisk takes the old man to a lecture on reincarnation, also attended incongruously by the local preacher, Dean Spanley. A friendship develops between Fisk and Spanley as it gradually comes out that Spanley seems to be the reincarnation of the father’s beloved childhood dog. The premise is made plausible by a gradual revelation of the premise, by Neill’s performance, and by some lyrical flashbacks. The whole thing is a surprising film to have come from Fraser, whose first feature, No. 2, was set in Auckland and concerned a family of Fijian descent. Yet it seems a sign of the New Zealand cinema’s health that he could take such an unexpected turn and tackle an English literary adaptation.

Australian movieThe Black Balloon (Elissa Down) is a contemporary story set in a Sydney suburb. It’s a social-problem film, dealing with a teenage boy, Thomas, torn between his love for his severely autistic brother (a truly remarkable performance by Luke Ford) and his frustration at the effect the brother’s antics have on his own ability to fit in at his new school. The film is apparently aimed primarily at a teen audience (it won the Crystal Bear for “Generation 14plus – Best Feature Film” at the Berlin Film Festival), but the almost exclusively adult audience at Palm Springs seemed entertained and touched by it. Australian stars who have made careers abroad often return to support their native industry by acting in local films, and Toni Collette is impressive as the mother. I found it a bit of a stretch that the one sympathetic, understanding fellow student Thomas finds happens to be a gorgeous girl who also seems to have no friends among their classmates. Apart from that, it’s an entertaining and informative film.

It does have one intriguing device in the pre-credits and credits scenes: several objects in each shot contain superimposed words identifying a number of the objects visible. The idea presumably is to suggest the fact that autistic people have excellent object recognition but difficulty understanding others’ emotions. I would have liked for the labeling to continue through the film, but I suspect most other viewers wouldn’t. Admittedly that would have distracted viewers from the narrative–unless we soon got used to it, which I suspect would have happened. At any rate, it’s a catchy way to introduce the story.

Another Exodus

Watching the Moroccan film Goodbye Mothers (Mohamed Ismail) was a disconcerting experience. At first it struck me as simply old-fashioned filmmaking, with multiple plotlines concerning three Jewish families living in Morocco at a time of increasing racial tensions. The stories are the stuff of melodrama, with a beautiful Jewish girl in love with a Moroccan man, a man debating whether to abandon his long-time friend and business partner to move his family to Israel, and the partner’s childless wife, who would be devastated by the departure of the family’s children, to whom she has been a second mother. In this age of short scenes, the film bases its action largely on extended shot/reverse-shot conversations, without much moving camera or many tight close-ups.

Eventually I realized that the film looks very much as if it had been made around 1960, which is the period of the story’s action.

The similarity can’t be coincidental. As with other Moroccan films I have seen, there is considerable emphasis on the music track, and here two or three scenes use the sweeping theme from Preminger’s Exodus. Indeed, the style is occasionally reminiscent of Preminger’s work of that era, as in shots that position characters precisely across the wide screen.

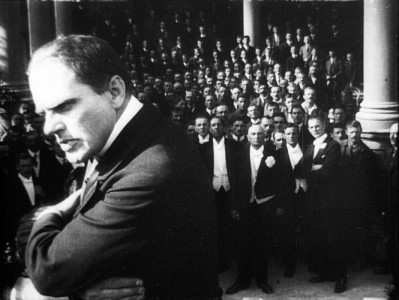

There’s also the sort of depth composition with a head prominent in the foreground that one associates with widescreen 1960s films by Nicholas Ray:

There’s more cutting than Preminger would typically use, but it’s an interesting pastiche that lends some subtle overtones to the film’s action. Despite a wide range of performance styles and a somewhat schematic set of plotlines, the film is an intriguing attempt to use a throwback style to convey the period when the peaceful co-existence of Jews and Muslims in Morocco was breaking down.

The quest film grows up

A few films do not necessarily a pattern make, but I’ve been struck by some echoes among the Middle Eastern films I’ve seen at this and other festivals. When the New Iranian Cinema came to international notice in the 1980s and 1990s, one narrative premise that several films shared led them to be labeled “child quest” movies. These tended to be simple searches or journeys: a boy trying to return his friend’s school notebook (Kiarostami’s Where Is My Friend’s Home?, 1987) or a girl trying to make her way through traffic to get home after school (Panahi’s The Mirror, 1997).

Gradually disasters, natural and manmade, caused the quests to become more serious. They often still involved children, but the just as often the seekers have been adults. Kiarostami’s And Life Goes On (1991) dealt with a film director’s journey into an earthquake-devastated area to find the child actor of Where Is My Friend’s Home?, who happened to live in the worst-hit area.

More recently, though, the disasters that create quests are wars in the region. My Marlon and Brando, the first feature of Turkish director Huseyin Karabey, deals with a actress in Istanbul. She has fallen in love  with an Iraqi Kurd, and when the U.S. launches its invasion of Iraq, the two are cut off from each other. Increasingly frustrated and desperate, the heroine sets out to join her lover in his home in northern Iraq, even though the convoluted set of border closings forces her to go by bus via Iran.

with an Iraqi Kurd, and when the U.S. launches its invasion of Iraq, the two are cut off from each other. Increasingly frustrated and desperate, the heroine sets out to join her lover in his home in northern Iraq, even though the convoluted set of border closings forces her to go by bus via Iran.

As she meets obstacle after obstacle and finds herself isolated in small villages where she cannot speak the local language, the film risks becoming monotonous. But audience attention is carried in part by a remarkable performance by Ayca Damgaci, who must carry every scene. At intervals we see videotaped messages sent to her by her lover. His effusive professions of love are juxtaposed with clips from the film where they had acted together, and these messages lead one to wonder just how sincere he is. Might he be leading her on through her grueling trek just to find disappointment?

My Marlon and Brando reminded me of Under the Bombs, which I wrote about from the Vancouver Film Festival. (It was also shown at Palm Springs.) There a distraught Lebanese woman travels by cab into the southern area bombed by Israel in 2006, seeking her son. Both films stress the difficulties of ordinary people’s making their way through combat areas or having to detour around them.

Another variant comes in Ramchandi Pakistani (2008), made by Mehreen Jabbar, one of several female  directors who have emerged in the Middle East. The mischievous Pakistani child Ramchandi wanders away from his village in Pakistan. He accidentally crosses the border into India—a border marks only by rows of painted white stones, giving the child no indication of the danger he faces. His father follows in an attempt to find him, and both are thrown into an Indian prison for years, their unregistered status making release highly unlikely. The film then alternates between the plight of the pair and their fellow prisoners and the frantic efforts of Ramchandi’s mother to find out what has happened to them and to eke out a living while hoping for their return.

directors who have emerged in the Middle East. The mischievous Pakistani child Ramchandi wanders away from his village in Pakistan. He accidentally crosses the border into India—a border marks only by rows of painted white stones, giving the child no indication of the danger he faces. His father follows in an attempt to find him, and both are thrown into an Indian prison for years, their unregistered status making release highly unlikely. The film then alternates between the plight of the pair and their fellow prisoners and the frantic efforts of Ramchandi’s mother to find out what has happened to them and to eke out a living while hoping for their return.

The three films deal with different conflicts: U.S.-Iraqi, Israeli-Lebanese, and Indian-Pakistani. All three stress the separations of families and lovers by hostilities and the barriers they arbitrarily create for ordinary people.

A small drama far away

In contrast, the Kazak film Tulpan (Sergei Dvortsevoy) presents flat, limitless, arid plains of southern Kazakstan, where borders and conflicts seem so far away as to be irrelevant. Asa, a veteran of the Russian navy, does not go on a quest but has a pair of local goals. He seeks to marry the elusive Tulpan and to establish his own flock of sheep. As he struggles to achieve  these goals, Asa remains an assistant to his brother-in-law Ondas, a tough, seasoned herdsman who keeps finding his ewes’ newborn lambs mysteriously dead.

these goals, Asa remains an assistant to his brother-in-law Ondas, a tough, seasoned herdsman who keeps finding his ewes’ newborn lambs mysteriously dead.

The film is director Dvortsevoy’s first fiction feature after a career as a documentarist, and he skillfully details the lives of Ondas and his family. There are two remarkable, squirm-inducing scenes of the births of lambs, handled in long takes that seem to make trickery impossible. Despite the hardships and disappointments, there are touches of humor, as when the local vet stops by to investigate the dead-lamb problem, accompanied by a bandaged baby camel in the side-car of his motorcycle and followed by its persistent, annoyed mother. A charming film and a crowd-pleaser.

See the film, avoid the city

During the Q&A after the screening of Jerusalema that I attended, queries from the audience tended to center around how accurate its depictions of rampant crime and violence are. Director Ralph Ziman assured us that they are quite accurate, and indeed the film is loosely based on a combination of true cases. Johannesburg, he claimed, is the world’s most violent city. Whether that’s strictly true, I don’t know, but Ziman’s film is a polished, gripping depiction of one brilliant young student’s rise and fall (and rise?) as a criminal. The script, with its complex flashback structure, is tight and fast-paced. The cinematography is consistently imaginative and beautiful. (See images at top and bottom.) I can best describe it as Michael Mann shooting a gritty Hong Kong action film, but setting it among Johannesburg gangs. The Mann influence is palpable. At one point the characters watch a scene from Heat to learn how to ambush an armored car, and Mann is among those thanked in the credits.

Jerusalema was South Africa’s submission for a nomination as the Best Foreign Film for the Oscars. Not surprisingly, it didn’t make the shortlist, being an action pic rather than the art-house fare that the Academy members favor. Its language is also a disconcerting melange of the tongues and dialects spoken in South Africa, including English. At times characters switch among languages in mid-sentence. According to Ziman, the script was written in English, and then the cast helped work out how their individual characters would speak the lines.

The basic story is familiar, with a teenager, Lucky, from Soweto accepted into a university but unable to pay his fees and intending to turn to crime temporarily to raise the requisite money. Naturally he tries to quit, only to be lured back. But Lucky uses his intelligence to work out a novel way to twist the law to his advantage, commandeering crime-ridden apartment blocks that have been allowed to slip below legal standards and buying them at bargain prices. It’s the dynamic style, though, that makes this so entertaining. It was one of my favorite films of the festival. Ziman announced that it had recently been sold for American distribution, but he would not reveal the name of the company before an official announcement. I’m not sure whether it would fit better into multiplexes or art theaters. Like so many recent films it seems to fall in between. (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Slumdog Millionaire are only the most recent examples that come to mind.) Its subtitles make it unlikely to find a really wide audience, but its violence might be off-putting to the art-house crowd. Wherever it ends up, it’s worth looking out for.

A final thought

During the festival, I was struck a number of times by how well-made films were that came from countries where production has previously been minimal. From South Africa, Kazakstan, Morocco, and Pakistan we see films that give the impression of having been made within a well-established industry. They adeptly use conventions familiar from festival-aimed art films or from classical Hollywood-style cinema. Clearly filmmakers in such countries have been seeing a lot of movies, even if they haven’t been making very many yet. The cliché about the cinema as an international language, almost as old as the medium itself, apparently remains as true as ever.

Note: Variety‘s wrap-up of the Palm Springs International Film Festival, including the prizes awarded, can be found here.

Three from Palm Springs

Four Nights with Anna.

DB here:

Three high points from the Palm Springs International Film Festival. Soon Kristin will offer some entries.

Four Nights with Anna is a GOFAM—a Good Old-Fashioned Art Movie. Set in a muddy Polish town, it follows a loner as he stalks a zaftig nurse. Leon watches her from around corners, studies her through her apartment window, and eventually sneaks sleeping powder into her sugar jar. This puts her out soundly enough to allow him to break into her apartment and watch her at close quarters.

My synopsis, like most retellings of this spare movie, not only spoils the experience but fundamentally changes it. Instead of laying out the premises explicitly, the film’s narration supplies them in tantalizing, equivocal doses. Skolimowski follows the great tradition of distributed exposition, so that we get context only after seeing something that can cut many ways. Early we see Leon buying an axe; soon he fishes a severed hand out of a sack and tosses it into a furnace. Is he a serial killer? No. After a while we learn that he’s the disposal officer for the hospital crematorium. Retrospectively fitting together these data provides a classic art-film pleasure, the equivalent of the curiosity-arousing clue sequences in a mainstream mystery.

The same goes for the ambiguous inserts that suggest a police interrogation. Only halfway through the film do these snippets become lengthy and explicit enough for us to place them in the story’s time sequence. Just as the Nouveau Roman of Robbe-Grillet owed a great deal to the classic detective story, the European art cinema tradition has drawn heavily on the investigation plot, from Les mauvais rencontres (1955) to The Spider’s Stratagem (1970). The premises of the thriller surface as well. The central conceit of Four Nights and of Kim Ki-duk’s 3-Iron, of a stranger who quietly and obsessively prowls around homes, was also explored in Patricia Highsmith’s 1962 novel Cry of the Owl, but not with Skolimowski’s playful indeterminacy about who and what and why.

The trick, then, is in the telling. By accreting details that cohere gradually, Skolimowski’s film not only engages curiosity and suspense, but also allows room for wayward, if dark humor. Leon’s quaking abasement leads to embarrassment, pratfalls, and comically strenuous efforts to melt into his surroundings. Objects take on a precise life, as Leon crushes his grandmother’s sleeping pills to powder and uses plastic silverware to fish a fallen ring from cracks in the floor. We never see Anna apart from Leon; she’s either in the same locale or glimpsed in precisely composed shots of her at her window. The exact, constrained handling of optical point-of-view owes a lot to Rear Window, but Jimmy Stewart never went so far as to install a new window to enhance his peeping.

In its diffuse exposition, its teasing inserts, and its gradually unfolding implications, a GOFAM also asks us to appreciate unresolved uncertainties. During the Q & A, Skolimowski remarked that he liked “to play with a little ambiguity . . . to leave it for the audience to interpret.” The locale? Indefinite, he says. The time period? Deliberately left vague. The mysterious final shot? “A third ambiguity.” For the man who made the kinetic Identification Marks: None (1964), Walkover (1965), Barrier (1966), and Le Départ (1967), film is something of a sporting proposition. It’s good to see him back in the game.

By contrast, The Shaft by Zhang Chi is a NFAAM, a Newfangled Asian Art Movie. That means minimalism. Single-shot scenes are captured by a distant, stable camera. Characters mutely go about their business, or just stand there. Pivotal plot moments take place outside the frame or between two static scenes. Any dramatic climaxes and grand passions are muffled or simply sufffocated.

The proximate sources of this Asian minimalism are probably the late 1980s films of Hou Hsiao-hsien. A European predecessor of the style, I think, is Fassbinder’s Katzelmacher (1969), but its most famous early instance would be Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman (1975).

Such a quiet style poses a problem: How to show plot changes and character development without lengthy dialogue? A common solution is to repeat setups in ways that diagram changes in character relationships. Have a young man pedal his bike up to his girlfriend and offer her a ride. Later as their relationship cools, show him in a similar framing riding callously past her.

Or show the couple wordlessly visiting a lake, but after they break up, show the girl standing there alone.

Tableaus can be used to parallel couples. Each pair meet near the village railroad trestle, but the compositions distinguish the couples.

Likewise, the shots showing the central family eating in front of the TV can be recalled through variation. The number of people at the table and their identities can change over the course of time.

The Shaft puts such conventions to solid use. In a rural Chinese town, young people face the choice of going to work in the mine or moving to Beijing. The film is built out of three stories, centering on a daughter, then her brother, and finally their father. At the end, the eventual revelation of what happened to the family’s mother throws the preceding love stories into sharper relief.

Once the innovators have mastered a style through dint of effort, others can glide down the learning curve and pick it up quickly. But then they should try to add something new. Today the rudiments of the minimalist style are comparatively easy to acquire. To go beyond those, you need something else—a more elaborate play with pictorial variations, or more ingenious staging (the Hou solution), or a gift for adjusting to the contours of landscape (the Jia Zhang-ke alternative). The Shaft is well-carpentered. It is measured and poignant (especially in its final story), and it concludes with a stunning trio of shots. Its very modesty, though, suggests the conventions of NFAAM need some renewal, even some shaking up.

Shaking things up is what Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s Tokyo Sonata is all about. A salaryman is downsized, but he can’t bear to tell his family. He pretends to go off to work while he actually tries to find a new job, any job. In the meantime, his sons display more ambition and courage in their limited worlds, than he does, while the mother tries to defuse the emerging tensions.

For an hour or so, this story is engrossing on naturalistic terms, alternating comedy and pathos. It might continue in a vein of gentle realism characteristic of that perennial Japanese genre, the shomin-geki, ending with everyone’s stoic reconciliation to the vagaries of life. But the director of Cure and Charisma will go along with this formula only up to a point. Why not break the form? You can argue that the simple purity of The Shaft plays too cautiously; once you’ve figured out how things will probably unfold, who cares to see the rest? A smooth cup is lovely, but a cracked one possesses its own enigmatic appeal.

So Kurosawa careens his homely tale into grotesque territory. The tone and plot logic that he’s cultivated so carefully are fractured by some violent emotions, implausible coincidences, and unexpected twists. Granted, his technique remains unruffled.Kurosawa follows Japanese traditions of enclosing faces in apertures and arranging people in gridwork patterns that still leave room for natural movement. The beginning of the story’s wild detour is discreetly signaled by a variant of the film’s first shot. But the composure of the handling makes the challenge to our expectations all the more disruptive.

I shouldn’t say much more, except to note that I meant the word fracture to suggest that the film mends its bones eventually. The final moments are taken up with a delicate performance of Debussy’s Clair de lune. Neither GOFAM nor NFAAM, risk-taking and in the end quite moving, Tokyo Sonata attests to the unpredictable innovativeness of Japanese filmmaking.

I may add other thoughts to Kristin’s upcoming dispatch, but for now I just note that Palm Springs is the only festival I know that uses Béla Tarr soundtrack cuts for pre-show music.

Tokyo Sonata.

Coming attractions, plus a retrospect

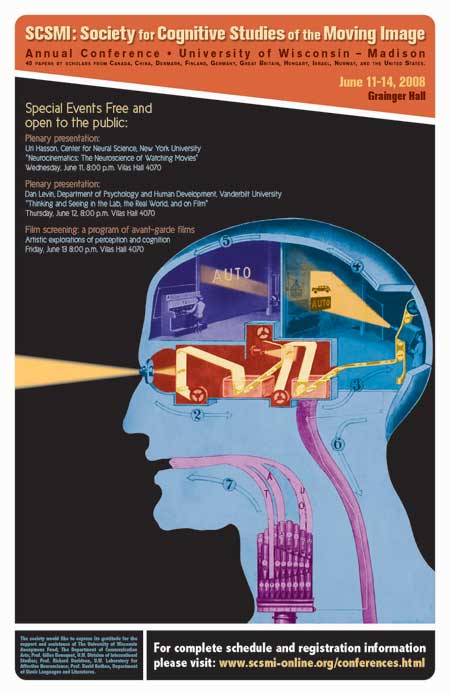

Invasion of the Brainiacs

First, the event that will occupy us through next week: the annual conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, a group founded in 1997. This year’s gathering brings researchers from Britain, Germany, Hungary, Israel, Turkey, Canada, China, and the Nordic countries, as well as many from the U. S. The meeting is here in Madison, from 11 to 14 June.

In over forty sessions, researchers will be talking about how we respond to movies, TV shows, and videogames. How has digital imagery changed our experience of cinema? How does film music enhance our emotional response to the story? How do films guide our visual attention to one part of the screen, and how much do viewers differ in this? How do we respond when movie characters behave inconsistently?

I’ve already blogged and bragged about our event here, but now I want to highlight four attractions. If you’re in or near Madison, you might want to stop by; and in any case, you might want to check the links mentioned below.

For some years Professor Uri Hasson of New York University’s Center for Neural Science has studied how the human brain responds during film viewing. Using fMRI techniques, he has discovered that Hollywood films, such as those by Hitchcock, have created remarkably similar responses across a variety of viewers. Art films, he says, may require just as much concentration, but they will elicit less convergent reactions. He’ll present the fruits of his research on June 11. You can learn more about Uri’s research here.

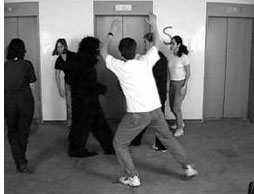

On June 12, Professor Dan Levin will lecture on “Thinking and Seeing in the Lab, the Real World, and on Film.” Levin has been actively studying how viewers’ concentration, watching a film or in real life, encourages them to overlook actions or changes taking place in front of them. He showed the power of “inattentional blindness” in his famous “gorilla-suit” experiments. Filmmaker Errol Morris recently interviewed Levin for The New York Times about continuity errors in films. You can read more of Dan’s fairly mind-bending work here.

On June 12, Professor Dan Levin will lecture on “Thinking and Seeing in the Lab, the Real World, and on Film.” Levin has been actively studying how viewers’ concentration, watching a film or in real life, encourages them to overlook actions or changes taking place in front of them. He showed the power of “inattentional blindness” in his famous “gorilla-suit” experiments. Filmmaker Errol Morris recently interviewed Levin for The New York Times about continuity errors in films. You can read more of Dan’s fairly mind-bending work here.

NB: 12 June 2008: In fact, the gorilla-suit experiment was conducted by Dan Simons, not Dan Levin. The last link takes you to Simons’ article. Both Dans work in the area of attention and “change blindness,” and they have collaborated on several projects. I apologize for the error.

There is a registration fee for the conference’s day events, but these evening lectures are free and open to the public. Each begins at 8:00 PM and will be held in 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Avenue.

The final night of the conference is devoted to a screening of experimental and avant-garde films that provoke questions about how we respond to cinema. There will be a discussion of them afterward, which will include two of the filmmakers, Joseph Anderson and J. J. Murphy. This screening, open to the public, starts at 8:00 PM in 4070 Vilas.

During the conference, one event is devoted to a discussion of Noël Carroll’s The Philosophy of Motion Pictures. This book is a remarkable effort to mount a systematic philosophy of film, TV, and related media. It’s full of provocative claims (e.g., that cinematic movement isn’t an illusion) and nifty examples. Noël is a polymath, with two Ph. D.s and more books and articles than anybody, including he, can count. Four other scholars will criticize some aspect of the book’s arguments, and Noël will respond. (One of those critics, Lester Hunt, is a philosophy prof here who maintains a wide-ranging website and a blog that often touches on film.) There should be some fireworks.

There are other brainiacs coming, many of them pioneers in this area: Joe and Barb Anderson, Murray Smith, Torben Grodal, Patrick Colm Hogan, Carl Plantinga, Paisley Livingston, Sheena Rogers, Dan Barratt, and Tim Smith (aka Continuity Boy), and too many others to include here. In all, I’m proud of what our local team, with the energetic Jeff Smith as point man, has accomplished in setting up this jamboree.

As regular readers know, I think that cognitive research into cinema holds great promise. It brings together a group of scholars from different disciplines who want to understand, in an empirical way, how movies work. The field is very young, and it’s not the only way to go; but it has a lot to contribute to our understanding of media, and maybe our understanding of the mind too.

Up to now SCSMI has been quite an informal group, but now we have a more systematic organization. We have officers, bylaws, and a sense that our research is coalescing around key ideas, about which there is lively and congenial disagreement. And, because there are more people who want to get involved, we’ll start meeting every year. The 2009 gathering is slated for Copenhagen.

I hope to dash off a blog entry in medias res. We’ll also do our best to introduce our colleagues from overseas and from the Coasts to the glories of brats, cheese, beer, and of course The House on the Rock.

By the way, you might want to check on this cognitive scientist, who claims that every one of us can see into the future (but only a little bit).

Kristin and the Comic-Book Guys (100,000 or so)

Speaking of gatherings of like-minded individuals, TheOneRing.net people have invited Kristin to take part in their panel on the upcoming Hobbit project at Comic-Con in San Diego, on Friday, July 25 at 10 am. She hopes to blog from among the multitudes.

A new website and a nervous DVD

There’s a new and attractive website up and running. Sponsored by the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, NYC, Moving Image Source is a vast project packed with links, research data, and essays about films both classic and contemporary. The first posse of writers includes Michael Atkinson, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Ed Sikov, Melissa Anderson, and other luminaries. The topics range from Andy Warhol and Howard Hawks to Werner Herzog (an interview). Steered by Dennis Lim, this is bound to be an essential watering hole for everybody interested in film history and criticism.

Speaking of film history, an important film is coming to DVD. Robert Reinert’s 1919 Nerven, which I wrote about in Poetics of Cinema, has been restored by Stefan Drössler and his crew at the Munich Filmmuseum. This is one of the strangest movies of the silent era. The plot, as Chris Horak points out in his accompanying essay, is steeped in Spenglerian melancholy, reminding us that Expressionism could be politically conservative as well as revolutionary. The visuals are at once monumental and unstable, like boulders teetering over a precipice. I try to analyze them in another contribution to the DVD booklet. Drössler has contributed an essay on the process of restoration.

Nerven was a box-office fiasco and never achieved the fame of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. In a way, it is more disturbing than that official classic because Reinert’s alternation of frenzy and somnambulism takes place in a more or less solid world, like ours. Frantic scenes of street fighting mix with brooding images of a bourgeoisie sliding into religious possession or straight-up lunacy. It is not every day that you see a movie that begins with a man throttling his wife and then lovingly refilling their parakeet’s water cup. If you’re a fan of wild deep-space imagery way before Citizen Kane (as above), this one’s for you. And yes, it will have English subtitles.

Nerven will be available later this summer from the Filmmuseum’s shop. It joins an abundance of other fine DVD titles, such as Borzage’s The River and a collection of Walter Ruttmann’s works.

Retrospect: In Europe they do things differently?

Because we see a very thin slice of foreign-language cinema, audiences underestimate the extent to which European films often imitate Hollywood. Surely the cultures of the great continent would never stoop to the crassness of our movies? A trip to any multiplex in Paris or Berlin would probably disabuse people of this notion. The current instance is the reigning French hit Bienvenue chez les ch’tis (Welcome to the Sticks), apparently a fish-out-of-water tale that would induce groans from our intelligentsia.

Kristin has already written about this phenomenon here. I found some supporting evidence last week while scrabbling through an old folder for our Film History revision. It was a 2002 pamphlet from the Filmboard of Berlin Brandenburgh GmbH, a publicly limited company coordinating German state funding. The text laid out a set of guidelines, in English, for productions that the Filmboard would support. After explaining that the judges must consider financial return as well as cultural factors, the guidelines insist that the quality of the screenplay is of paramount importance. What makes a good screenplay?

The success of a film decisively depends upon whether the audience can engage enthusiastically with the actors on the screen. An audience looks for strong central characters whose fates it can identify with. The hero or heroine should have goals and needs and should have an emotional effect on an audience. Further dramaturgical criteria:

There must be a concrete goal, which at the end of the story is either reached—or not.

There should be a risk involved for the central character in not reaching his/her goal.

The goal is perhaps difficult to reach, and the struggle to do so should bring the central character into conflict. The audience sympathizes with the story when, for example, the hero or heroine follows the wrong goal, makes mistakes, or experiences a crisis.

This sounds easy to understand. But writing screenplays is more complex.

*The central character should have subconscious needs. He/ she should lack an important human quality and only gradually experience this for him/herself.

*At the end of the story the central character should come to know his/her unconscious needs and gain a satisfactory recognition about him/herself and life in general, which can be formulated in the emotional subject matter of the film.

*The central character should undergo a process of development, as characters that do not develop are boring. Moments of decision in stories are the key for good character development.

The passage lays out a lot of what U. S. screenplay manuals have been asserting for decades (notions that Kristin and I have analyzed in various books). This is still more evidence that the Hollywood model, with its goal-oriented chain of causes and effects and its protagonist who improves through a “character arc,” holds sway far beyond our own shores. Whether it should be so widespread is another question, but for Kristin and me, this template or formula is a bit like the sonnet or the well-made play: a form that can yield results good, bad, and indifferent. The point is to take the form seriously enough to understand what makes it work.

From Comic Book Guy’s Book of Pop Culture (New York: HarperCollins, 2005), n.p.

Modest doesn’t mean unambitious

DB still in Hong Kong:

There are plenty of big attractions at this year’s festival. After seeing Om Shanti Om (wildly enjoyed by the audience), I was standing outside the theatre at the Cultural Centre and intersected with hordes of teenagers running to get seats for Candy Rain, a Taiwanese movie starring pop songstress Karena Lam. The result was the Wong Kar-wai homage above.

But many of the best films at this year’s festival don’t come on strong. They simply trust that you will pick up on their quiet virtues. One example is In the City of Sylvia, which I saw at Vancouver and wrote about here. There are others too.

The way we live now

In my previous entry, I mentioned three main sorts of HK films being made these days: programmers, auteur films, and epic coproductions. I neglected a fourth category, that of the small-scale film commenting on local life and history in a heart-warming, nostalgic vein.

Every year a few of these are made, usually attracting a small public. Examples would be Herman Yau’s From the Queen to the Chief Executive (2000) and Give Them a Chance (2006), Samson Chiu’s Golden Chicken (2002) and its sequel (2003), and last year’s Mr. Cinema, a gentle history of Hong Kong from the standpoint of an idealistic movie projectionist. An older example is the sweet-natured Umbrella Story (1995), which integrates CGI footage of Bruce Lee and other stars. Golden Chicken found box-office success, but mostly these projects attract a small public at home and an even smaller one abroad. They don’t, as the saying goes, travel well.

An ambitious example of the grassroots Hong Kong movie had its premiere last week. Ann Hui’s The Way We Are is remarkably bereft of ordinary plotting and dramatic conflict. A widow raises her teenage son in a high-rise apartment in Tin Shui Wa, a district in the New Territories. She works in the fruit section of a supermarket, while he waits for the results of his high school examinations. They meet an old woman living in the same building and they get somewhat involved with her personal problems, the chief one being a hostile son-in-law.

The widow’s mother takes sick. A distant relative dies. An uncle promises to pay for the son’s overseas education. The film refuses to exploit the traditional dramatic potential of any of these situations. There is no tragedy, no sudden burst of violence, no slaps or wails or shattering confrontations. This is a movie in which, by the standards of traditional dramaturgy, nothing happens.

The widow works hard, but she isn’t made saintly; she’s just a kind, devoted person, wearing a perpetually alert half-smile. The son seems at first to be wasting his summer by lounging about, but he dutifully runs errands and takes responsibility for helping his hospitalized granny. The Way We Are makes Edward Yang’s Yi Yi look melodramatic.

The bulk of the film consists of people simply passing their time—working, meeting family and friends, and above all eating. The Way We Are must have more food scenes than any other movie in history. We watch food wrapped, chopped (durians especially), cooked, and consumed. There aren’t many Hong Kong movies that don’t feature food scenes, but this movie puts eating front and center. Again, though, feeding your face doesn’t get the comic or dramatic charge it has in classics like Michael Hui’s Chicken and Duck Talk or Tsui Hark’s Chinese Feast. Eating is just another routine.

Ann Hui has created perhaps Hong Kong’s closest equivalent to Ozu: a film in which daily life, unemphatically presented, is sufficient to engage our sympathies. Granted, The Way We Are lacks Ozu’s formal rigor, his habit of mirroring situations through composition and color design and auditory motifs. Shot on HD in longish, straightforward takes, Hui’s film risks seeming as mundane as its subject. Still, her impulse seems akin to his: a delicate search for human kindness in the commonplace. A title of another of Ann Hui’s films would do for this one: Ordinary Heroes.

Ann Hui has created perhaps Hong Kong’s closest equivalent to Ozu: a film in which daily life, unemphatically presented, is sufficient to engage our sympathies. Granted, The Way We Are lacks Ozu’s formal rigor, his habit of mirroring situations through composition and color design and auditory motifs. Shot on HD in longish, straightforward takes, Hui’s film risks seeming as mundane as its subject. Still, her impulse seems akin to his: a delicate search for human kindness in the commonplace. A title of another of Ann Hui’s films would do for this one: Ordinary Heroes.

The project began as a much grimmer story based on a brutal murder in the neighborhood. But Ann couldn’t bring herself to shoot the script. Investigating Tin Shui Wa, she realized that it was “similar to the squatter huts of the 1950s or the resettlement areas of the 1970s. It is very Hong Kong.” Like the other grassroots films, it recalls earlier periods, using a few judicious montages of stills of people at work and play. It is nonetheless a film about today, showing local life with quiet optimism and good humor. Ann still hopes to shoot the original script as a dark companion piece, creating “a complete statement” on contemporary ways of living. (1)

Two other low-key titles

The Pope’s Toilet (Enrique Fernández, César Charlone). The Pope is visiting Uruguay, and a smuggler decides to build a pay toilet for the hordes who will be swarming into his little town. The intrinsic comedy of the situation is nuanced by the serious portrayal of Beto’s failings, his wife’s patience with his intransigence, and his daughter’s hope of escaping her cramped life. How can you not like a film with a man frantically cycling home, a commode lashed to his bike? A touching surprise that would brighten up any festival’s roster.

Milky Way. I admire Benedek Fliegauf’s Dealer (2004), a nightmarish chronicle of a drug dealer’s hectic final hours, and especially the imaginative network narrative The Forest (2003). This last is a must-see for its careful construction and its moment-by-moment eeriness.

So I was eager to catch Fliegauf’s latest, Milky Way. It consists of ten shots, each one a distant tableau showing a landscape punctuated by human presence. The action develops through minuscule changes, often in a comic direction. Fliegauf compares his compositional strategy to the online game Samorost. To me it recalled Structural narratives like Jim Benning’s 11 x 14 and perhaps owes something to Kiarostami’s 5. On the whole it seemed to me not as original as his earlier works. Still, without words, presenting gorgeous imagery and evocative noises, the film tries for nothing more than a series of calmly unfolding visual conundrums. As Fliegauf remarks, “I think that this film quiets the mind.” (2) That’s something worthwhile in these days of all-out cinematic assaults on your brainstem. Yes, I am thinking of Transformers.

More to come this week–many more films, plus at least one interview with a filmmaker.

(1) Quoted in “The Way We Are,” program notes in catalogue for The 32nd Hong Kong Film Festival (Hong Kong, 2008), p. 94.

(2) Quoted in “Milky Way,” festival catalogue, 189.

Ann Hui before the premiere of The Way We Are.

PS 6 April 2008: Thanks to Mike Walsh for a correction on an earlier version of this entry.