Archive for the 'Asian cinema' Category

Party time in Hong Kong

Today, pix from two get-togethers during the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

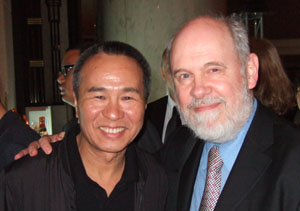

Johnnie’s dinner

Johnnie To gave another of his legendary dinners, this time to a crowd of filmmakers, distributors, festival directors and programmers, and hangers-on like me. The meal was old-school HK fusion, mixing Brit colonial food (boiled tongue, boiled potatoes, boiled veggies) with unique local variations (pigeon, a puffy vanilla soufflé). I think it’s akin to what Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung scarf down so elegantly in In the Mood for Love. Very tasty.

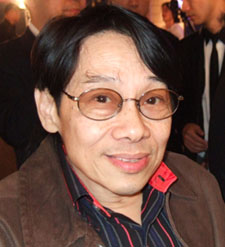

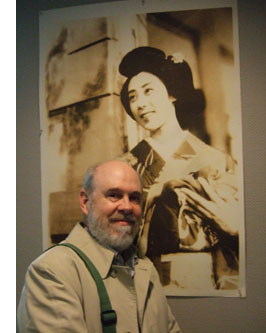

Among those present: Director Kirk Wong.

Kirk made The Club (1981), Health Warning (1982), Gunmen (1988), and other classics, including the 1994 double-header Organized Crime and Triad Bureau and Rock ‘n’ Roll Cop. These are terrific movies, admired by every fan of action cinema.

Festival consultants consult: Mike Walsh (Melbourne, Adelaide); Stephen Cremin (Far East Film Festival of Udine, Screen International); and Todd Brown (S x S W, FantAsia, Twitchfilm).

Cameron Bailey, Co-Director of the Toronto International Film Festival, lets me try an Ozu-style composition.

A small bolt of lightning

One of the most appealing things about Hong Kong film is that character actors, as we call them in America, go on and on, becoming not only stars but directors and producers. As Leslie Cheung pointed out, the local audience is loyal to its favorites and encourages them to try many things.

Eric Tsang, the short, cherubic guy with the perpetually hoarse voice and blinding smile, began, surprisingly, as a soccer player. In 1974 he became a bit player and stuntman in Shaws’ martial-arts releases. He directed two of the movies in the top-grossing Aces Go Places cycle (1982, 1983), and rose to become a screen personality. He’s so familiar to Hong Kong movie lovers that we couldn’t call him Tsang; he’s just Eric, and he’s irreplaceable.

He worked steadily and hard, appearing in nine films in 1985 and an astounding seventeen in 1988. Several of his performances are superb: playing a small-time loser in Final Victory (1987), a flamboyantly gay music coach in He’s a Woman, She’s a Man (1994), a philandering policeman in the exhilarating and little-known Task Force (1997), a wistful romantic in Metade Fumaca (1999), and of course an implacable triad boss in the Infernal Affairs trilogy (2002-2003). He perks up every movie he graces, rescuing routine projects with his beaming ordinariness. In a fairly ordinary policier like Cop on a Mission (2001), he starts out as a thuggish menace and becomes not only sympathetic but heroic in his devotion to his errant wife.

Cop on a Mission is one of several of Eric’s films screened in the HKIFF tribute. The event also emphasizes his role as a producer. Thanks to him, we have The Outlaw Brothers (1990), Dr. Mack (1995), Men Suddenly in Black (2003), Jiang Hu (2004), and several films he coproduced with Peter Chan Ho-sum. Most recently, Eric has launched a project to support young directors. He launched Winds of September, a feature trilogy about coming of age in the “three Chinas”—the mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

For the premiere of Tom Lin Shu-yu‘s Taiwan entry on Friday night, the festival held a little party for several hundred of Eric’s closest friends. For once, that last phrase is no joke; everybody feels close to him.

Glamor to spare: Cheng Pei-pei, of Shaws’ glory days and since, with her daughter Marsha Yuan Zi-hui.

Peter Chan, fresh from the success of The Warlords, chats with Tony Rayns.

Michelle Carey, Festival Editor of the encyclopedic online journal Senses of Cinema and scout for several film festivals. Alongside, Cheung Tat-ming, idiosyncratic young actor; check out his laid-back performance in Once Upon a Time in Triad Society 2 (1996).

Also there were Teddy Robin Kwan, a wonderful actor and pop singer who first made his mark with movies from Cinema City, and Albert Lee, this year’s Executive Director of the festival.

And Eric was as entertaining from the back as from the front.

Next time, I promise more on the movies. I close with two items:

Strangest line of the last twenty-four hours: From inside a hotel room I was passing: “Mom, I haven’t mentioned a threesome until now.”

Johnnie To shows himself a man of outstanding taste.

And I show myself a man of no shame. But you knew that already.

THE place

“For us, Hong Kong will always be the place.”

Chuck Norris, The Octagon (1980)

DB here:

Hong Kong’s Entertainment Expo, including the Hong Kong International Film Festival, the Asian Film Finance Forum, and the Hong Kong Filmart, runs for nearly a month, and it has drawn me back to the fragrant harbor. For refreshers, you can visit last year’s posts here.

Biz

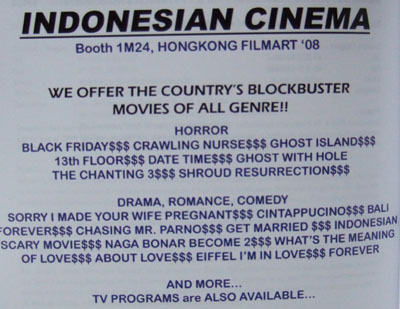

The Filmart has become Asia’s biggest spring media event, with hundreds of companies crowding into a pavilion of the Convention Centre. Here people traffic in movies and TV shows, buying and selling distribution rights, seeking funds for production and partners in movie ventures. I wandered through it last year, and you can track this year’s activities at Variety’s site here.

The last figures I saw indicate that the world pumps out about 4800 features each year. Coming to a market like Filmart, you get to peek below the waterline and see the iceberg that’s underneath.

There are, for instance, the bulk genre items from secondary, or tertiary, producing countries.

There are the films that seem somewhat derivative.

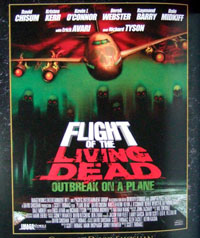

Then there’s the vehicle with the midrange star that just might make it to late-night cable.

Finally, there are the films that acknowledge themselves to be identical. These descriptions come from Imagination Worldwide’s catalogue ad.

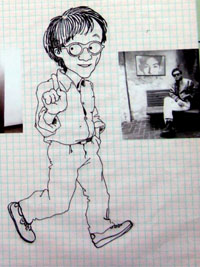

By contrast Filmart mounted a respectful display devoted to Edward Yang, who died last summer. Edward made idiosyncratic, powerful films that would, even today, be very hard to sell at a market. He was a skilled cartoonist, and the display includes some of his perky storyboards and a self-portrait.

The Asian Film Awards, which I covered last year, started things off with a midsize bang Monday night.

The full results can be found here. I was pleased that Secret Sunshine, quite a good film, won three top awards (film, director, actress). Milkyway, a favorite company of mine, garnered a couple of prizes, and The Sun Also Rises, one of my favorites from last year, did pick up the Production Design prize.

Some Big Stars were visible at both the show and the after-party. Heartthrob Tadanabu Asano arrives.

Lee Kang-sheng and Tsai Ming-liang mingle before the awards.

Marco Muller, Director of the Venice Film Festival, at the after-party.

I got to talk briefly with one of my heroes, Hou Hsiao-hsien.

And of course Tony Leung Chiu-wai, emblem of the Entertainment Expo and winner of the Best Actor Award (Lust, Caution), was everywhere, and always looking good.

Within 36 or so hours, I saw quite a lot of movies. With friends Paisley Livingston and Mette Hjort and their kids I caught Enchanted, which pleased me with its schmaltzy cleverness. As part of the Festival, I re-watched on 35mm two movies I’d seen and commented upon last year: Jiang Wen’s The Sun Also Rises and the Tsui/ Lam/ To Triangle. These were shown at the shock-and-awe auditorium of a new cinema in a spanking new mall, Elements. The seats vibrate at the lowest frequencies, creating what is marketed as “4-D.”

At Filmart I saw the Luc Besson production Taken, another satisfying dose of formulaic filmmaking. Altogether different was Manuel de Oliveira’s Christopher Columbus, The Enigma. The title suits this apparently slight film about a historian’s earnest pursuit of Portugal’s influence on North American history. Haunting images of 1940s Manhattan swathed in fog, along with touching scenes of Mr. and Mrs. Oliveira visiting historic sites, linger.

Two films struck me as excellent. Gao Qunshun’s Old Fish (2008) centers on a simple idea. Somebody is planting bombs throughout Harbin, and an aging police officer is the only person remotely qualified to dismantle them. Over a leisurely half hour, we’re introduced to Old Fish, his wife, and his colleagues. Then the first bomb is found, and the suspense kicks in. The apparently clumsy codger, who in an early scene fumbles a World War II grenade, summons up wiliness and delicacy when he has to defuse the mysterious packages.

Two films struck me as excellent. Gao Qunshun’s Old Fish (2008) centers on a simple idea. Somebody is planting bombs throughout Harbin, and an aging police officer is the only person remotely qualified to dismantle them. Over a leisurely half hour, we’re introduced to Old Fish, his wife, and his colleagues. Then the first bomb is found, and the suspense kicks in. The apparently clumsy codger, who in an early scene fumbles a World War II grenade, summons up wiliness and delicacy when he has to defuse the mysterious packages.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen more tension-filled sequences of this sort. The film made me realize that in any bomb-disposal scene, when close-ups of a sweating face and a knifeblade hovering over a wire are followed by an extreme long-shot of the scene—that’s when we expect an explosion. Conventionally, the long shot announces the bang. But here, Gao gives us the long shot, and we have to wait, and wait some more. When the explosion does come, it is genuinely surprising.

Shot by shot and sound by sound, this is a very well-crafted, humane film. If anybody tells you that “foreign films” are digressive and boring, show them Old Fish.

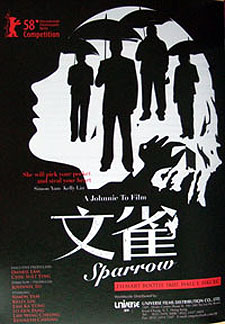

Just as fine, but more unclassifiable, was Johnnie To Kei-fung’s The Sparrow (2008), premiered at Berlin. A gang of pickpockets led by Simon Yam is beguiled by a mysterious lady on the run (Kelly Lin), and their schemes start to fall apart. As often with To, the conception of the film is slim, but the execution is rich. There are the games and competitions, the symmetries and repetitions, the offhand motifs (here, cigarettes, cigars, and pipes), the geometrical and arithmetical plot mechanics. Johnnie To has become perhaps the world’s most unpretentiously, unapologetically formalist director.

It’s a procession of twists and set-pieces. There are the funny one-off shots, like the two grifters with symmetrically broken legs and the gang flashing the razor blades they hide in their mouths. Some sequences are unpredictable miniatures, like the scenes that show how many camera angles you can find in an elevator car, even with a fishtank squeezed in. There’s also a delirious bit with a lipstick-stained cigarette.

Other set-pieces unfold more majestically. There’s a sweeping crane shot of the gang vacuuming up wallets of passersby, and an elaborate theft of a pendant during massage therapy. The climax is an exuberant pocket-picking competition with all contestants stalking through a downpour, their umbrellas forcing them to work with only one hand.

The Sparrow is at once a loving tribute to old Hong Kong island (Simon’s hobby is black-and-white photography), an unpredictable genre piece, and an exercise in light-fingered filmmaking. Like Old Fish, it offers lessons to Hollywood directors, if they have the wit to learn them.

Bits

At Filmart, Fred Ambroisine multitasks, taking cellphone calls and shooting docu footage at the same time.

Deng said “To get rich is glorious,” and now Mao agrees.

And in the spanking new, gargantuan mall known simply as Elements, an entire room is devoted to one essential Element.

More to come, soon I hope, from The Place.

Japan journey, part 2

DB here:

A seesaw trip in my last few days in Japan, with notes on watching some rare movies, visiting some superheroes, and watching some children cut down swaggering samurai.

Kansai wanderer

On Friday I traveled to Nagoya University with Yamanouchi Etsuko. She was my translator for a talk on Japanese film for my student, now professor, Fujiki Hideaki (above). Hideaki oversaw the translation of Film Art into Japanese and is the author of a new book on the growth of movie culture in Japan during the first decades of the century.

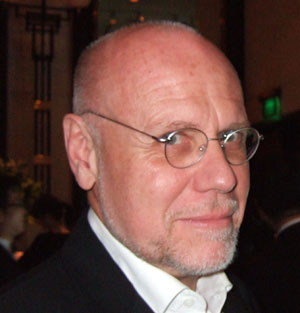

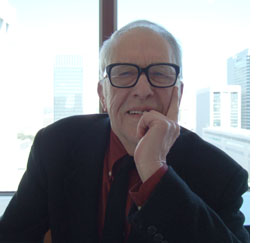

The talk seemed to go well, though my customary rapid-fire yammer sometimes left the fluent Etsuko breathless. Hideaki’s students and colleagues kept me on my toes with sharp questions. Then we all went out to a sumptuous dinner, where I had a chance to talk to many Nagoyans, including senior Japan expert Peter High, author of The Imperial Screen. Peter is now about to retire, as you can perhaps tell from his expression.

The talk seemed to go well, though my customary rapid-fire yammer sometimes left the fluent Etsuko breathless. Hideaki’s students and colleagues kept me on my toes with sharp questions. Then we all went out to a sumptuous dinner, where I had a chance to talk to many Nagoyans, including senior Japan expert Peter High, author of The Imperial Screen. Peter is now about to retire, as you can perhaps tell from his expression.

Because I lectured on what I call the “game of vision” in Japanese films, we had fun at dinner with composing shots that mimicked the peekaboo framings. Even relaxing, film wonks never turn off the movies running in our heads.

Next day I took a fairly impulsive trip to Kyoto. I tried to visit Mizoguchi’s grave, but had no luck finding it. After visiting it ten years ago, I shouldn’t have trusted my memory. Instead, I found Toei’s movie theme park, which provided me three hours of diversion.

Shochiku studios failed with its own theme park (go here for my reminiscence of it), partly because it had only Ozu and Tora-san as main attractions. But Toei has a bevy of swordplay heroes and….Power Rangers. An entire wing of the facility is dedicated to superheroes, life-size and some much larger.

I had no idea who these hardfaced bipeds were, but they sure looked pretty, with their nice snowmobiles and vaguely obscene gestures.

Elsewhere in the Toei park are streets evoking old Edo and Kyoto, as well as a kabuki theatre.

Mechanical ninja crawl around overhead, and samurai stroll the alleyways. You can watch a director pretending to shoot a TV show of swordplay in a studio set.

The most enjoyable moments came with a display of swordfight stunts carried out by three good-humored young samurai. They summoned from the audience a tiny boy, a somewhat older boy, and a tall little girl, and they gave them some elementary fighting skills. These skills consisted of stomping forward, crouching, and swinging the sword while letting out a blood-freezing shriek. The teachers made it look easy.

Then each kid was planted in front of the crowd and a swordsman rushed forward, with howling abandon. Miraculously, the kids’ fairly minimal defense tactics always defeated the men, who died in agony.

When one winner got obeisance from his enemies, he acted like the constantly scratching Mifune in Seven Samurai.

A new old Mizoguchi

Back to Tokyo and a round of shopping, eating, and moviegoing. I was staying with Komatsu Hiroshi, a friend of almost thirty years whom I first met at a conference on Dreyer in Verona. Hiroshi is a monumental figure in silent-cinema circles, and I’m planning a later blog entry profiling him.

With Hiroshi I saw two silent Makino Masahiro films at the national Film Center. For more on this series, see an earlier entry. Chronicle of 3 Generations (Gakkusei san daki, 1930) consisted of two installments of a short-comedy series produced by Makino. In the first, a modern girl throws over her boyfriend because he’s a bad baseball player. The second was reminiscent of Ozu’s Days of Youth in showing a college student trying to hide his slacker ways from his visiting father.

The second film, also part of a series, was directed by Makino. Street of Ronin (Roningai, 1929) was a bustling tale of a neighborhood of ne’er do wells. The benshi commentator must have been busy; there are over 260 intertitles in a film of about 72 minutes. I can’t tell you what happened in the plot, but the movie shows yet again that by the end of the 1920s Hollywood continuity style was in full vigor here. Makino uses a remarkable number of different setups in each scene.

At Hiroshi’s house he screened many rare items from his collection, mostly silent European, American, and Japanese films. One of the most striking Japanese titles was Magic in the Dark (Kurayami no Tejina, 1927), an experimental short with some of the stylization one finds in Kinugasa Teisuke’s Page of Madness (1926). The rain-drenched night scenes are like something out of Murnau.

The plot is didactic and uplifting, showing how a boy tempted by money pursues a righteous path. Magic in the Dark was directed by Suzuki Shigeoshi, whose most famous film is What Made Her Do It? (1930). That famous but currently incomplete feature, along with Magic in the Dark, will be released on the Kinokinuya DVD series that Hiroshi directs. Alas, no English subtitles. (See the PS below.)

The killer item was a newly discovered Mizoguchi film, one that doesn’t appear on official filmographies! Miss Okichi (Ojo Okichi, 1935) was residing in the Shochiku vaults, and a copy, in beautiful condition, was recently screened on Japanese television. Mizo codirected it with Takashima Tatsunosuke, a director whose work I don’t know, for Dai Ichi Eiga, the production company he formed with Nagata Masaichi. Dai Ichi Eiga, which later became Daiei, financed Mizo’s masterpieces Naniwa Elegy (1936) and Sisters of Gion (1936).

A bit like The Downfall of Osen (Orizuru Osen, 1935), this film centers on a woman who’s a cat’s paw for a gang involved in shady dealings. Okichi, played by Yamada Isuzu (whose bosom I nestle against in my earlier entry), is pulling scams for the sake of her lover. But she falls out with the gang and takes pity on one of the young men whom she victimizes.

I can’t comment on the film after only one viewing, and the fact that Mizoguchi is credited after Takashima suggests that he may have had little input. Still, it’s another tale of a woman who sacrifices herself for more or less unworthy men. Miss Okichi also has some typically Mizoguchian scenes that dwell on chiaroscuro melancholy. Much of the film takes place at night, and this strategy reinforces the somber atmosphere. There are some remarkably opaque long shots and one moment that includes Okichi turning toward the camera in a sort of plaintive challenge.

Given my admiration for Mizo, this capped a terrific ten days in Japan. Now on to Hong Kong, where I’ll blog at intervals on what happens at the Hong Kong Filmart market, the Asian Film Awards on Monday night, and the HK International Film Festival. I’ll be there, like Bernstein in Citizen Kane, before the beginning and after the end.

PS 24 July 2008: The Kinokuniya DVD of What Made Her Do It? has come out, and Joanne Bernardi reports that at least one version does have English subtitles…by her! Magic in the Dark is included on that disc. And despite information to the contrary, the DVD Joanne has is not Region 2 but all-region. Oddly, online listings of the DVD make no mention of these facts. Joanne does not yet know whether the subtitled all-region disc is the same as the one offered on amazon.jp and the Kinokuniya site, but it seems likely. More information as I get it, from Joanne or others.

Tokyo choruses

DB here:

I’ve had a terrific time since I arrived late last Saturday. The only thing that could have improved it would be the discovery that there was a Japanese town named Bordwell. If it could happen to Barack, why not me?

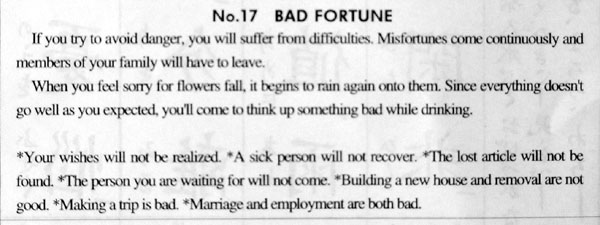

Actually, I know why not. On Sunday, a trip to a temple yielded a promise that nothing good would come on any front.

Pretty dire. Yet I press on, foolishly trusting that meals will be tasty, the city will shake me up, and three fine sorts of things will grace the first phase of my stay: the symposium, the movies, and my companions. Still, I vow to avoid thinking up something bad while drinking.

The conference

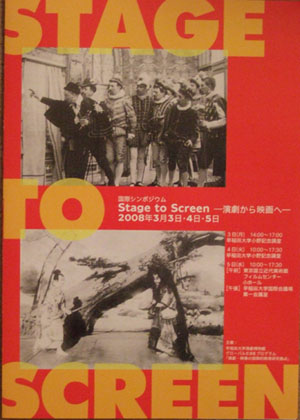

I came for a symposium at Waseda University, Stage to Screen. For three days local scholars delivered papers and comments about how cinema related to theatre.

Young researchers have done thorough work on the relation of Japanese cinema to the culture’s lively theatrical traditions. Usai Michika explored a topic that’s always fascinating–the benshi, the person who accompanied silent film with commentary and dialogue. She found a remarkable poster from the Waseda Theatre Museum collection illustrating many short films, and through diligent archive work she was able to identify most of the films. Although the poster came from 1899, the films were all pre-1896. Ogawa Sawako gave a thorough examination of how films were influenced by kodan, a sort of novelistic oral recitation. It turns out that kodan stories were at least as important as kabuki plays as sources of Japanese film, well into the 1920s. Shimura Miyoko studied later forms of rensa-geki, the mix of live performance and film that was fairly common in the silent era. She showed that there was a resurgence of it in the early 1930s, with sound cinema.

Western cinema attracted attention as well. Kataoka Noburo analyzed the relationship between Samuel Beckett’s Play and his Film, directed by Alan Schneider and starring Buster Keaton. Our host Professor Komatsu Hiroshi gave a talk called “Actors without Bodies,” suggesting the quasi-supernatural qualities of early film. He surveyed cinema’s links to the phantasmagoria shows of the French magician Robertson. He also explored how sound recordings synchronized with early films evoked theatre but didn’t exactly correspond to stage performance techniques–another form of bodiless acting.

There were two keynote addresses as well, one from Yuri Tsivian and one from me. Yuri was, as usual, energetic and infectious. Our talks naturally overlapped when we touched on the 1910s, and we had some good conversation about films of that era offstage as well as on. Above you see Yuri analyzing, with his usual body English, a scene that he has made famous–a play with mirrors in Bauer’s King of Paris (1917).

The films

The last day of the symposium was devoted to two films that show how world film language changed between the mid-1910s and the early 1920s. Goro Masamune (1915) is a complicated tale about a swordsmith and the dramatic results of his mysterious parentage. It offered a stringent version of the sort of tableau staging we find in Europe and the US at the same period. As with those films, Goro Masamune used lateral staging and some striking depth effects, as well as long takes: I counted 58 shots and 24 intertitles across its 58 minutes.

With 356 shots and 25 intertitles, Roben-sugi exemplified a more cutting-based approach to cinematic storytelling. Scenes were broken down into many shots, often with a great variety of setups; the 180-degree system is in force; and many expressive effects were based on intercut close-ups. In the lengthy final scene, Roben, a temple bishop, discovers his long-lost mother and she prostrates herself before him. The action is played out in high-angle shots of the mother and low-angle shots of Roben. You couldn’t ask for better proof that filmmakers around the world were adopting the US continuity approach than this 1922 film.

These two movies were powerful treats, and the day was embellished with a visit behind the scenes to the Film Center’s staff area, where I got Yuri to shoot me with one of my favorites, Yamada Isuzu.

These two movies were powerful treats, and the day was embellished with a visit behind the scenes to the Film Center’s staff area, where I got Yuri to shoot me with one of my favorites, Yamada Isuzu.

Earlier in the week, with Kyoko Hirano, I’d visited the Film Center to catch an item in its massive Makino Masahiro retrospective. Makino, son of Japan’s pioneering director Makino Shozo, directed films from the late 1920s to the early 1970s. For his centenary, the Center has mounted 100 programs of his work. No, that’s not a typo. The screenings include 110 titles directed or produced by Makino—and of course several others are lost. Japanese filmmakers are nothing if not prolific.

The film that Kyoko and I saw was Japanese Gangster Story 6: Sake Cup of the White Sword (1967), starring Takakura Ken. The plot consisted of intrigues crisscrossing rival gangs during the 1920s, capped by two bloody fights at the end. Ken doesn’t say much, but the camera loves him; early in the film he seemed to me to get the biggest close-ups. In the finale, of course he sacrifices himself for his gang boss. Is any genre cinema more standardized than the 1960s-1970s yakuza yarn? After a lunch of the Asakusa version of big Hiroshima-style omelettes, Makino’s buoyant retake on the classic tropes was a filling dessert.

The people

The third factor that has made this trip so pleasant has been the people. Hanging out with Yuri was great fun, and as luck would have it, Wisconsin film guy Michael Pogorzelski was visiting Tokyo at the same time. Mike is the archivist for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and he restores classic films for the AMPAS collection. (It isn’t all Hollywood, either: the archive is handling Satayajit Ray and Stan Brakhage.) Darkness and rain turned our trip through Shibuya into a scene out of Blade Runner.

Then there was Komatsu Hiroshi, who invited me to the symposium. Hiroshi is one of Japan’s top film historians, a man tirelessly committed to finding Japanese films and explaining their significance. He has made his appearance on this blog before. There was also Fujiwara Toshi, an exuberant young filmmaker I first met in Kyoto about ten years ago. Toshi has directed docs about Amos Gitai and other filmmakers, and his latest fiction film, We Can’t Go Home Again, played at the Berlin festival.

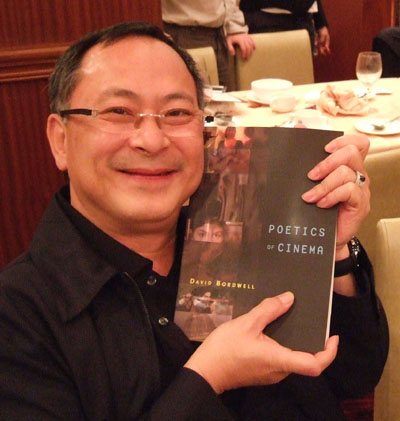

I’ve mentioned Kyoko Hirano, another former student and a best-selling author. Then there was my lunch with Donald Richie, hearty at 82 and planning more books, film screenings, and festival trips. His classic, The Inland Sea, is now being translated into Romanian. He gave me a copy of his newest, A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics and I reciprocated with a copy of Poetics of Cinema. Donald’s book is as delicate and sharp as a Basho lyric; beside it, my book looks like an andiron.

I’ve mentioned Kyoko Hirano, another former student and a best-selling author. Then there was my lunch with Donald Richie, hearty at 82 and planning more books, film screenings, and festival trips. His classic, The Inland Sea, is now being translated into Romanian. He gave me a copy of his newest, A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics and I reciprocated with a copy of Poetics of Cinema. Donald’s book is as delicate and sharp as a Basho lyric; beside it, my book looks like an andiron.

At the symposium I learned a great deal from Prof. Takemoto Mikio, director of the Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum at Waseda University, and the vice-director Prof. Akiba Hirokazu; Prof. Takeda Kiyoshi, who studied with Christian Metz; Prof. Nagata Yasushi of Theatre Studies; and many others who contributed talks and comments.

Finally, one more person, the one who spurred me to study Japanese cinema.

Ozu Yasujiro‘s gravesite is in Kita-Kamakura, about an hour southwest of Tokyo by train. In the summer of 1988, Kristin and I were led there by Donald, and so I was due for another pilgrimage. The day was cool and sunny, perfect for a brisk walk through the grounds of Engaku-Ji Temple.

At the end of my trip was the gravestone, which famously bears a single character: Mu, or nothing. Twenty years ago, two beer cans sat reverently on the stone, but today there was an opened bottle of sake. A cigarette lighter was tucked into a hole in the surrounding stone fence. Ozu, fierce smoker and professional drinker, was in his element.

On the platform and then on the train, I let my eyes drift among the schoolkids and the teenyboppers and the salarimen and the grave elders with hygiene masks. I began to imagine how Ozu, the poet of the transience of city life and the comic poignancy of human ties, would turn us all into cinema. He might put the camera over there, squatting on the floor of the traincar. That boy with the backpack might give a sassy reply to his father. Those two stylish office ladies sharing an iPod while a middle-aged man snores beside them–surely that’s a setup for a gag. Playing with the possibilities, one gaijin felt a pang of rapture at the blending of life and art.