Archive for the 'Asian cinema' Category

Updates: Len Lye, Frodo Franchise, blockbusters, and news from/about Hong Kong

Kristin here—

More on Len Lye

After my recent post on Len Lye, I heard from both Roger Horrocks, Lye’s biographer, and Tyler Cann, Curator of the Len Lye Collecton of the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth, New Zealand. (Neither with corrections, I am happy to say!) They have filled me in on some activities that should make Lye’s film work more accessible.

First, a DVD of Lye’s films is being prepared. Unfortunately factors like the process of assembling the best surviving prints means that the finished product will not be available in the near future.

Second, the near future will bring a touring program of Lye’s films to North America. Called “Free Radical: The Films of Len Lye,” it has been organized by The New Zealand Film Archive, the Len Lye Foundation, and Anthology Film Archives. (The name was inspired by Lye’s scratched-on-film animated short, Free Radicals, 1958.) Here are the venues and dates:

Oct 12 Anthology Film Archives, New York

Oct 12 Anthology Film Archives, New York

Oct 18 NASCAD (Nova Scotia College of Art and Design) Halifax, Nova Scotia

Oct 23 Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley

Oct. 28 Film Forum, Los Angeles

Oct 30th CALARTS, Los Angeles

Nov 2nd University of Notre Dame, Indiana

Nov. 7th George Eastman House, Rochester

Nov. 26th Harvard Film Archive, Cambridge

Dec 8th Chicago Filmmakers, Chicago

Dec. 15th International House, Philadelphia

Roger tells me that he intends to write a book on Lye’s theory and practice of what he called “the art of motion.” This reminds me that I forgot to mention that there is a collection of Lye’s writings, Figures of Motion: Len Lye Selected Writings, co-published in 1984 by Auckland University Press and Oxford University Press. It was co-edited by Roger and Wystan Curnow and is, alas, long out of print. Another thing to look for in your local library.

The Frodo Franchise

I am happy to report that The Frodo Franchise is now in the process of being rolled out. The University of California Press has been shipping copies for weeks, and it should soon appear on bookstore shelves—and may have already in some places. The copy we pre-ordered from Amazon back in April arrived on July 30.

I have bowed to the inevitable and am in the process of constructing a separate website, “Frodo Franchise,” to deal with matters relating to the book and the films. (That is, Meg, our web czarina, is constructing it.) I don’t want information about the book, comments on the Hobbit film situation, and similar items to overbalance our blog, which they threaten to do. I’ll post a notice when the site is up and running.

In the meantime, Pieter Collins of the Tolkien Library, an excellent reference and news site dedicated to the novels, has interviewed me about my book. You can read the result here. Henry Jenkins has done the same, through his site, Confessions of an Aca-Fan, is more oriented toward popular media and fandom. The interview is in three parts here, here, and here.

Hollywood Blockbusters Doing Pretty Well

On February 28 I posted an entry, “World rejects Hollywood blockbusters?” There I argued against claims in an article by Nathan Gardels, editor of NPQ and Global Viewpoint, and Michael Medavoy, CEO of Phoenix Pictures and producer of, among many others, Miss Potter. They claimed that there were many signs that Hollywood’s big-budget films are being rejected at the box office: “Audience trends for American blockbusters are beginning to show a decline as well, both at home and abroad.”

Since then, of course, Hollywood blockbusters have been cleaning up at home and abroad. We’re all familiar by now with the series of huge international openings, with many blockbusters being released day and date in most major markets. As one example, take Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, which so far has grossed $774,070,000 worldwide. The US and Canada claimed only about one-third ($264 million) of that total (Box Office Mojo, August 4). Overseas, Phoenix has scored $510 million, for 65.9% of its global haul. The Three Threes, Shrek, Pirates, and Spider-man, all cleaned up internationally, as did Transformers. (The fourth Three film, The Bourne Ultimatum, looks set to do the same.) The Simpsons Movie has recently begun its climb to box-office glory.

Leonard Klady, an excellent writer on the international film industry, summed up the situation for 2007 in the 22 June print edition of Screen International: “Worldwide predictions that 2007 would break recent box-office records look to be well founded. The international box office generated $4.5bn in the first four months of 2007. Combined with revenues from the domestic North American marketplace, the global gross for the period was $7.2bn. International theatrical [i.e., markets outside the U.S. and Canada] accounted for 61.6% of the worldwide box office on gross figures that exceeded domestic ticket sales by 60.6%. Based on current viewing trends, global box office could finish the year at a record-breaking $24.6bn.”

Klady points out that much of the rise comes from the factor I discussed in my earlier entry: the expansion of the international market. According to him, “The international market has become increasingly significant in the past decade.” A decade ago, foreign income averaged 45% of Hollywood films’ takings. By 2006 it was around two-thirds.

These facts also bear on Neil Gabler’s February article, “The movie magic is gone,” where he lamented the purported decline in theatrical films’ importance. That there was such a decline, he claimed, was evidenced by the fact that box-office revenues are down, both domestically and abroad. I refuted Gabler’s claims at some length in this March 11 post, and the successful summer that Hollywood is now enjoying adds further evidence to show that his argument was based on false assumptions.

DB here–

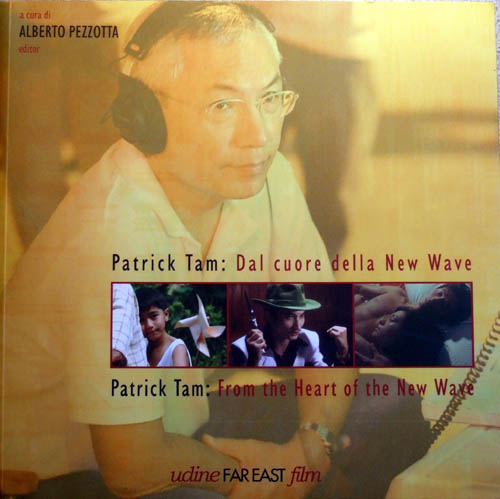

The Udine Far East Film Festival had a tremendous program this year, and just the YouTube promo made you want to book a ticket. But I couldn’t go! Still, the organizers kindly sent me their excellent catalogue Nickelodeon and the real topper, the festival’s thick volume dedicated to Patrick Tam Kar-ming. Editor Alberto Pezzotta, indefatigable researcher into Hong Kong film, organized a vast retrospective of Tam’s key New Wave films, such as Nomad and The Sword, as well as his less-known television work. The book includes critical essays, a detailed filmography, and a long, informative interview. Tam brought a cosmopolitan sensibility to Hong Kong film, thanks to his sensitivity to European directors like Godard and Antonioni. His latest film, the widely acclaimed After This, Our Exile, signals a new phase in his career.

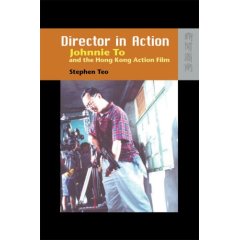

When I was writing Planet Hong Kong between 1997 and 1999, I was often frustrated by a lack of solid information and in-depth critical writing. Tony Rayns’ superb essays and the annual catalogues published by the Hong Kong International Film Festival were about all I could rely on. That situation has improved in recent years, with many well-researched books on Hong Kong film appearing. Outstanding here is Stephen Teo, who has given us two books this year alone: King Hu’s A Touch of Zen and the just-out Director in Action: Johnnie To and the Hong Kong Action Film. This efflorescence of writing comes just when local cinema is in its deepest slump. You won’t find me quoting Hegel often, but in this instance it does seem that the owl of Minerva is flying at dusk.

When I was writing Planet Hong Kong between 1997 and 1999, I was often frustrated by a lack of solid information and in-depth critical writing. Tony Rayns’ superb essays and the annual catalogues published by the Hong Kong International Film Festival were about all I could rely on. That situation has improved in recent years, with many well-researched books on Hong Kong film appearing. Outstanding here is Stephen Teo, who has given us two books this year alone: King Hu’s A Touch of Zen and the just-out Director in Action: Johnnie To and the Hong Kong Action Film. This efflorescence of writing comes just when local cinema is in its deepest slump. You won’t find me quoting Hegel often, but in this instance it does seem that the owl of Minerva is flying at dusk.

Two Chinese men of the cinema

A Brighter Summer Day.

DB here:

This summer two major figures in Chinese filmmaking died. One was Edward Yang (Yang Dechang), one of Taiwan’s finest directors, who died on 29 June. But before I pay tribute to him, I want to acknowledge another figure who had a great impact on Asian cinema.

Charles Wang died on 6 July. Along with his brother Fred, Dr. Wang ran Salon Films, the major supplier of film equipment for Hong Kong and a principal one for East Asia and the Pacific Rim. Charles graduated with a degree in chemistry before inheriting the business from his father. As Hong Kong filmmaking grew in sophistication, Salon grew along with it. Most Hong Kong films bear the firm’s brand in their end credits.

Since 1969 Salon has provided top-flight cameras, lenses, lighting gear and other technical support for both local and visiting productions, such as Mission: Impossible III‘s Shanghai shoot. An early triumph was winning the Panavision franchise for the region. The company even supplies trampolines and landing cushions for martial acrobatics, as this glimpse inside a Salon van shows.

Since 1969 Salon has provided top-flight cameras, lenses, lighting gear and other technical support for both local and visiting productions, such as Mission: Impossible III‘s Shanghai shoot. An early triumph was winning the Panavision franchise for the region. The company even supplies trampolines and landing cushions for martial acrobatics, as this glimpse inside a Salon van shows.

When I interviewed Dr. Wang in 2003 he kindly gave me information about the company and the development of film technology in Hong Kong. He showed me his many awards and talked enthusiastically about Salon’s new efforts to assist mainland moviemaking. In recent years, Salon was investing in films such as Zhang Yimou’s Hero. Like most Hong Kong film people, he was very accessible and generous; he even gave me a lift back to my hotel. Charles Wang was a major force in the Hong Kong industry and will certainly be missed.

Laconic cuts and long takes

I met Edward Yang twice. First, at a Hong Kong Film Festival reception, we chatted about his film Mahjong (1996), which had screened. I got to know him a little better in fall of 1997, when we were both invited to the Kyoto Film Festival. We ate and watched films together, and we shared baby-boomer nostalgia; it turns out that he and I (and Hou Hsiao-hsien) were all born in the same year.

I found him friendly, thoughtful, and open to appreciating all film traditions. He spoke of enjoying Japanese swordplay movies in his youth, and he admired American films for their gripping stories. Still, his preference for ellipsis and understatement came through. When we met Kitano Takeshi for dinner, Edward praised a crisp transition in Sonatine: to show the gang going from Tokyo to Okinawa, Kitano simply gives us a quick pan of the sky accompanied by the sound of a jet plane.

Yang was an accomplished cartoonist, and I thought that this background partly explained his early style, on display in the short film Desires (1982) and in the features That Day, on the Beach (1983), Taipei Story (1985), and The Terrorizers (1986). In these films Yang often breaks his scenes into simple but striking fragments. After the police shootout in The Terrorizers—one of the most enigmatic and elliptical opening sequences in modern cinema—the Eurasian girl staggers out to the street. Yang gives us her collapse in quite abstract, percussive images. Her foot hits the pavement. Cut. She takes a step and falls out of frame; the camera holds on the empty frame. Cut. She’s lying on the crosswalk. I imagine these as forceful, laconic comic-book panels.

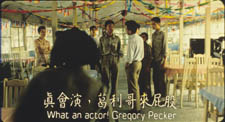

With A Brighter Summer Day (1991), my favorite of his works, Yang tells another gap-filled story but treats the scenes in long, distant, often decentered takes reminiscent of Hou. Now his frames are more dense with figures and furniture, and layers of action extend quite far back. In Figures Traced in Light, I devote a little—too little—analysis to one admirably staged passage. Another of my favorite scenes in A Brighter Summer Day shows the hero Xiao S’ir developing a romantic attachment to Ming, the girlfriend of the absent gang leader Honey. They sit in a brightly decorated café.

Suddenly Ming darts out of the shot, leaving Xiao S’ir and the other boys staring. From their point of view we see that Honey, dressed in a sailor suit, has returned and Ming has gone to meet him.

Yang cuts back to the boys as Honey’s gang starts to threaten Xiao S’ir. Abruptly, Ming runs into the shot, past the boys, down the long central aisle, and out of the café. (In a 35mm print you can see her pausing and lingering outdoors.)

The group closes around Xiao S’ir; only Honey’s entry breaks the tension. He leads the boy into the depth of the shot, the camera following them.

Honey warns Xiao S’ir off, and our hero goes outside, mimicking the path Ming had followed.

As Honey turns his attention to his gang and an upcoming skirmish with their rivals, he moves back down the aisle, the camera backing up. Once his business is done, Honey drifts back to the rear door.

Honey pauses far from us, at the window. Yang cuts to show what he sees: Xiao S’ir, in flagrant violation of the warning, talking to Ming outside.

First we got Xiao S’ir’s point of view on Honey and Ming; now, in a reversal, we get Honey’s point of view on Ming and Xiao S’ir. In scenes like this, Yang merges his developing skills in long-take staging with cuts that develop not only the action but story parallels. Very distant framings, characters moving to the rear of the shot and turning their backs: Yang “dedramatizes” the scene. Further, by shifting point of view, he leaves us guessing about story information: What led to Ming’s running away from Honey? What are Xiao S’ir and Ming talking about now? Yang created a laconic visual approach that, I’d argue, invests fairly standard dramatic situations with a tantalizing uncertainty.

Yang’s best-known film is, of course, Yi Yi (2000), and it won him the wide appreciation that he had long deserved. It’s a warm and gentle work, less innovative than his earlier efforts but utterly typical of his vision of lives pervaded by melancholy routine and abrupt disappointment. People often remarked that the adolescent hero of A Brighter Summer Day resembled Edward himself. Perhaps too in Yi Yi Yang’s enigmatic pictorialism is echoed in the idea of a little boy who makes photographs of people’s heads seen from the rear. Like the director, the boy (named Yang-yang) displays a reticence that respects the mysteries of people’s private lives.

We already have a very useful guide to Yang’s work in one chapter of Emilie Yueh-Yu Yeh and Darrell William Davis’ book, Taiwan Film Directors. And Criterion’s Curtis Tsui has done a wonderful edition of Yi Yi, as Brian Hu shows here. We must hope that Criterion, Eureka, or another gilt-edged DVD publisher will soon bring us Yang’s other works in the pristine editions they deserve.

A Brighter Summer Day (1991)

In 1998, when we screened A Brighter Summer Day at our Cinémathèque, I wrote a program note. I reproduce it, lightly revised, as a quick pointer to one of the great films of the 1990s.

With Taipei Story (1985) and The Terrorizers (1986) Edward Yang established himself as one of the two leaders of the Taiwanese New Wave generation. At first it seemed that he and Hou Hsiao-hsien had agreed to a division of labor in their subjects and styles. Hou tended to concentrate on life in the countryside, or on rural characters transplanted, bewilderingly, to the modern city. Hou was also deeply interested in the history of Taiwan; his most acclaimed film, City of Sadness (1989), is a panoramic survey of Taiwanese society immediately after World War II. Hou’s tranquil style favored a contemplative mood and muted emotion.

Yang, by contrast, tended to focus on the lives of well-to-do urbanites in a contemporary setting, Taiwanese yuppies plagued by anomie and the desperation of love and work. His elliptical editing technique, reminiscent of Resnais, fractured time and space, while his compositions had a painterly starkness. The Terrorizers shuttles kaleidoscopically among characters at its beginning; their relations only gradually settle into intelligible patterns. Whereas Hou tended toward nuance and quiet drama, Yang was unafraid of shocking, inexplicable bursts of bloodshed.

Now it seems evident that this impression of a division of labor was somewhat schematic. Hou’s range of interests has widened, with new emphasis on the violent world of urban crime (Goodbye South Goodbye, 1996), and he has come to rely on quite disorienting transitions between past and present (Good Men, Good Women, 1995). Likewise, with A Brighter Summer Day Yang turned to history and cultivated a more sober style of filming, with lengthier shots and a fixed or barely moving camera. This approach throws down a challenge to the razzle-dazzle of contemporary popular cinema—from Hollywood, Hong Kong, and even the American “independents”—and invites us to scrutinize, moment by moment, the details of action unfolding on the screen.

Three years in the making, A Brighter Summer Day was a triumph of independent production. At a period when the Taiwanese film industry was virtually dead, Yang found money (mostly Japanese) to mount a project of remarkable ambition. Over half the cast and crew had never worked on a film before. At first released in a three-hour version, the film was re-released in a four-hour director’s cut, and this has become the standard version.

The historical event examined in A Brighter Summer Day took place in Taipei in the 1960s, when an adolescent boy about Yang’s age stabbed a young woman. At epic length Yang creates a web of circumstances around the event. He shows the interplay of traditional culture—filial duty, education as an ideal of social advancement—with popular culture, especially the rock n’ roll songs that recur throughout. Yang has said that Americans might not realize the shattering force of rock in other cultures: “These songs made us think of freedom.”

The film has over eighty speaking parts, most filled by nonactors, and it intertwines several characters’ destinies. On first viewing, the film can be somewhat bewildering to a non-Taiwanese audience, so a plot sketch may help. (Skip to the next paragraph if you don’t want to know the action in advance.) At the center is fourteen-year-old Xiao Si’r. He tries to be a dutiful student, but with his friends Cat and Airplane, he lives on the fringes of the Little Park gang of teenage thugs. When Xiao Si’r reports seeing a gang member with another boy’s girlfriend, he triggers a power struggle in the gang. As his friends fall by the wayside and rival gangs fight for control of local turf, Xiao S’ir becomes involved with Ming, a girl who’s attached to Honey, exiled leader of the Little Park gang. A major climax occurs during a gang rumble at a rock n’ roll concert. Interwoven with the juvenile intrigues are political matters; the police pursue and question Xiao S’ir’s father about his Communist friends. Xiao S’ir becomes friendly with Ma, a general’s son, before they start to compete for Ming’s favor. The rivalries build to a tense schoolroom confrontation and a tragic finale in the park. In the final scene and over the credits, a radio transmission broadcasts the names of the students who have passed their school entrance exams.

The plot is even more intricate than my bare-bones summary can indicate; I haven’t discussed the boys’ adventures in a film studio or Cat’s singing career or the slender line of action involving Xiao S’ir’s sister. The breadth of action is extraordinary, and a sense of the contradictory pulls of daily life emerges steadily. No less demanding is Yang’s style—scenes played in darkness, few close-ups, with medium-shots and long-shots keeping us at a distance from the characters. But the result is a dispassionate look at teenaged passions, a deromanticized treatment of young people growing up in a repressive milieu. A Brighter Summer Day (the English title comes from Elvis Presley’s “Are You Lonesome Tonight?”) is an elegy to the ideals and mistakes of youth, an analysis of the vanities of the male ego, and a view of a generation painfully facing the limitations of tradition, the constraints of political oppression, and the demands of the modern world.

Yi Yi.

Another Bologna briefing

More notes and notions from Cinema Ritrovato, all from DB:

Could you make a movie today about a farm girl who becomes a concert pianist under the sway of a womanizing egomaniac? The slightly nutty I’ve Always Loved You (1946) displays Frank Borzage’s usual faith in the way lovers communicate by spiritual ESP, this time aided by Rachmaninoff. Borzage talked the low-end Republic studio into this expensive project, and the result, though marred by strained performances, looks great in a glowing restoration by UCLA. A teenage André Previn darts through, and for once someone playing the piano onscreen (in this case Catherine McCloud) looks skillful. (The playback renditions were those of Arthur Rubinstein, credited as “the world’s greatest pianist.”) The title is perfectly ambiguous, since it could refer to any character’s attitude toward almost any other.

Travel delays prevented Ben Gazzara from introducing the fine print of Anatomy of a Murder. Too bad. It would be fascinating to hear how he developed his disturbing portrayal of an accused killer under Preminger’s notoriously dictatorial direction. But Gazzara did participate in an interview with Peter von Bagh that led into a screening of a beautiful restoration of Jack Garfein’s The Strange One (aka End as a Man).

Gazzara talked of coming out of the Actors Studio after the success of Marlon Brando, a tremendous influence on Gazzara’s generation. He recalled that he was in the same Studio class as James Dean, Steve McQueen, and Paul Newman. What was the Method? “It’s a word I never use. I don’t know what it means. . . It gave you things to fall back on” if you couldn’t come to grips with the script material.

Gazzara talked of coming out of the Actors Studio after the success of Marlon Brando, a tremendous influence on Gazzara’s generation. He recalled that he was in the same Studio class as James Dean, Steve McQueen, and Paul Newman. What was the Method? “It’s a word I never use. I don’t know what it means. . . It gave you things to fall back on” if you couldn’t come to grips with the script material.

He said that he loved Hollywood acting of the studio era: Gable, Grant, Tracy, and Stewart remain fresh and modern. When he saw Meet John Doe, he realized that Gary Cooper used his own version of the Method: “He did very little, but he did everything.”

Gazzara said that seeing Faces (1968) drew him to Cassavetes. “I was mesmerized. I was so jealous. I thought, I’ve gotta work with this man.” A year later he made Husbands. Cassavetes was very supportive, always “waiting for surprises.” He was laughing in enjoyment behind the camera, encouraging his players. “All you did was safe, and you could do no wrong.”

The Strange One, set in a Southern military academy, was Gazzara’s first film. He was offered the part of the cadet who eventually leads a revolt against the Machiavellian cadet Jocko De Paris. But Gazzara said that he wanted to play DeParis because “he got all the laughs.” George Peppard wound up with the good guy role. Though the film seems to me confused on several dimensions, Gazzara revels in the showy part of a soft-spoken, eminently reasonable sociopath. As in Anatomy of a Murder, he makes gently menacing use of a cigarette holder.

In the early 1930s, Japanese companies explored the possibility of exporting their films to Europe and the US. One result of these initiatives was Nippon: Liebe und Leidenschaft in Japan, a 1932 German compilation created by Carl Koch. It originally consisted of three films from the Shochiku studio, condensed and supplied with German intertitles. The original films were silent, so, oddly enough, synced Japanese dialogue was added.

In the version screened here, only two episodes were presented. What beauties they were! Since many of the 1920s and 1930s Japanese films that survive look quite weatherbeaten, it was wonderful to see, in the print from the Cinémathèque Suisse, how gorgeous quite ordinary movies from this era could be.

The first story, Kaito samimaro (orig. 1928), deals with a young samurai rescuing his beloved from the clutches of a corrupt priest. Brisk and beautifully shot, it came to the sort of frothing swordplay climax typical of the period—rapid cutting, dynamic tracking, and slashing assaults aimed at the camera. Kagaribi (1928), about a young vassal betrayed by his corrupt lord, likewise ended with a protracted action scene capped by a jolting climax. A prolonged tracking shot follows the young man’s former lover as she backs away from him, but then we cut to a full shot. With a single stroke he kills her, jaggedly ripping a paper door in his follow-through. Both stand motionless for a moment before she falls. A conventional finish, but no less eye-smiting for that. For more on the power of this action-cinema tradition, see an earlier entry on this site.

There are no fewer than ten flashbacks in the 1950 Swedish film Flicka och Hyacinter (Girl with the Hyacinths, above). Peter von Bagh’s Bologna programming has often highlighted Nordic work that’s little known outside the region, such as this engrossing post-Kane exercise in probing a dead person’s life. Teasingly directed by Hasse Ekman, the interlocking flashbacks would be savored by today’s puzzle-film aficionados, and the movie’s equivalent of Rosebud is genuinely surprising. The twist would never have been permitted in Hollywood of that era.

Kristin and I hope to post one more entry, probably soon after Ritrovato’s final session on Saturday. Lots more to report–Lubitsch, Borzage, Chaplin (of course), etc. For now, a glimpse of the official names of the Cineteca’s two screening rooms…

Bando on the run

Sakamoto Ryoma (1928).

The Matsuda Eigasha company of Tokyo deserves enormous credit for restoring and making available classic Japanese films. My first visit to the firm twenty years ago was a revelation. Matsuda Shinsui was a former benshi, or spoken-word film accompanist, and he and his sons were collecting old films so that he could accompany them in screenings. A great many of the films were chambara, or swordfight movies. Most survived only in fragments, but what tantalizing fragments they were! (1)

The company made several of the films available on VHS tape, accompanied by benshi commentary prepared by Mr. Matsuda. I came away with several of these treasures. On later visits I was able to watch some films that hadn’t been transferred to video, and several of those deserve to be more widely seen.

When Mr. Matsuda’s son kindly drove me to my train station, I noticed that his car had a VHS player and video monitor installed in the dashboard. So much for my Tokyo-ga experience.

In 1979 Matsuda Eigasha compiled a documentary on the swordplay star Bando Tomasaburo. Now Digital Meme has made it available on DVD, complete with English subtitles. Bantsuma: The Life of Tomasaburo Bando is obligatory viewing for everyone interested in Japanese cinema. Not only does it handily trace Bando’s remarkable career through stills, interviews, and surviving footage. It also supports something I’ve tried to show for some time: that the Japanese action cinema of the 1920s and 1930s was one of the most powerful and creative trends in world filmmaking.

In 1979 Matsuda Eigasha compiled a documentary on the swordplay star Bando Tomasaburo. Now Digital Meme has made it available on DVD, complete with English subtitles. Bantsuma: The Life of Tomasaburo Bando is obligatory viewing for everyone interested in Japanese cinema. Not only does it handily trace Bando’s remarkable career through stills, interviews, and surviving footage. It also supports something I’ve tried to show for some time: that the Japanese action cinema of the 1920s and 1930s was one of the most powerful and creative trends in world filmmaking.

Action and innovation

Some writers have thought that Japanese filmmakers were developing a culturally anchored approach to filmic storytelling independent of Western influences. But in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema and two essays in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema, I argue something different. By the early 1920s Japanese filmmakers had mastered Hollywood’s norms of visual storytelling. In the Matsuda documentary, this is evident from the clips from early Bando films like Gyakuryu (1924) and Kageboshi (1924). Long shots are broken up into closer views, and conversations are treated in reverse-angle shots of speaker and listener. Camera movements follow the characters as they walk or run.

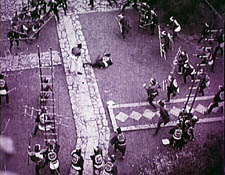

So far, so conventional. But many Japanese filmmakers revised the American approach, turning it into something more expressive and experimental. So, for example, a very steep high angle in Kirarazaka (1925) serves at first to show us that Bando is surrounded by fighters who use ladders to try to trap him. As the scene returns to this framing again and again, it becomes more abstract, with the fallen ladders becoming vectors of a geometrical shot design targeting the hero.

An even more remarkable example is Orochi (1925), a Bando film that survives intact and in fine shape. (Matsuda released it on VHS; I don’t think it’s on DVD yet.) The clip in the 1979 documentary shows one of Orochi‘s most dazzling passages. The hero, played by Bando, fights his way through a town, and, backed up against a wall, he’s trapped on all sides by his opponents. An extreme long-shot (below) shows us the situation, with Bando in the distant center. Many shots break this space down into opposing forces, Bando versus his adversaries, and quite fast cutting shows the men on either side of him.

The stretch that interests me most begins with a shot of Bando looking left.

The director Futagawa Buntaro then breaks the confrontation into separate shots of the other swordsmen. Nothing unusual about that. But most directors would have handled the next few shots of the standoff this way:

Shot of Bando looking left.

Shot of a combatant looking right (implicitly, back at him).

Shot of Bando looking right.

Shot of a combatant looking left (implicitly, back at him).

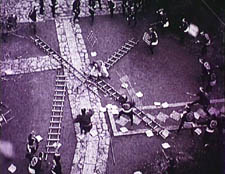

This way we’d get a clear, simple sense of the fact that he’s surrounded on all sides. Instead, Futagawa follows the shot of Bando looking left with no fewer than twelve very close shots of fighters, all looking rightward. For example:

Then we get six shots of their arms outthrust, as here:

We then get a shot of several men looking straight to the camera, as if they represent the group directly in front of Bando, no longer at the left. Next there appear another ten shots of fighters looking leftward at Bando, all of them quite close to the camera. For example:

In both sets of shots, many images are composed to match each other graphically: the first group of faces tends to place each man on the left frame edge, while the second set puts most men at the far right. The first set of shots develops a pattern, moving from tight facial close-ups to shots of arms and swords thrusting toward Bando. The second set develops toward showing faces that are ever more cut off by the right frame edge.

Add in the fact that all these shots are cut very quickly, ranging from four frames down to one! This is extraordinarily rare in 1925 cinema. (I talk more about how to study such passages in an earlier blog.) Words can’t really convey the way these images clatter against one another. Their percussive speed makes them graspable only as a tense thrust in one direction countered by an equally tense one opposite. Faces pile frantically up against Bando first one one side, then the other. The sense of linear force is strengthened by the shift from the cluster of face shots to that of the arms, with the transition handled in a pair of weird jump cuts along different men’s arms.

The transition from the first shot above to the second creates the impression that the man has jabbed with his spear, while the cut from the second to the third shot eases us to the forearm shots shown earlier.

This bravura passage is triggered by the initial shot of Bando, haggard and shaky. Perhaps the cascade of shots is motivated as subjective, reflecting his exhaustion in the face of entrapment. Just as likely, I’d say, is the fact that Futagawa took a stereotyped situation, the hero surrounded by his adversaries, and looked for a way to make it fresh, to use energetic stylistic innovation to amplify the story point emotionally and perceptually.

Nothing in the sequence violates continuity editing’s basic principles. The shots keep screen direction constant and character position clear. Indeed, the director has understood spatial continuity very deeply: the men to the left of Bando are pushed far to the left side of the frame, the men to the right are squeezed rightward, so that Bando is always implicitly filling the area they’re recoiling from. But what American director would have risked such a bold piece of cutting?

Orochi, let’s remember, was released the same year as Strike and Potemkin. If this passage had been known to the earliest generation of film historians, Japan might well have been greeted as another birthplace of daringly dynamic montage. (2)

There are several other intriguing flourishes in the footage on display in Bantsuma, particularly a scene of Bando dying in a swirl of steam (this entry’s top image). But two points should be clear: this is innovative filmmaking of a high order, and it took place in a shamelessly commercial film industry. Mainstream filmmaking in Japan has been open to stylistic experiment to a degree rare in other popular cinemas. You can trace a line from the 1920s to the present, from the chambara directors through Ozu and Mizoguchi and Kinoshita and Suzuki Seijin right up to Kitano and Miike. Along a parallel path, Hong Kong action cinema pressed filmmakers toward creative renovation of film technique. (3) In this tradition, the action films of Bantsuma and his peers hold an honored place.

The lessons are familiar ones from this blog. Mass-market cinema harbors experimental impulses; creative directors working in well-known genres are often striving to push the limits. By attending to technique, we can discover a dazzling variety in areas of film history not usually considered “artistic.”

PS: Through Digital Meme, Matsuda has also made available a treasury of 55 animated films from the earliest years. The are at work on a DVD of early Mizoguchi films, including a fragment I’m keen to see from Tojin Okichi (Okichi, Mistress of a Foreigner, 1930).

(1) A large set of them has been available for some years on a DVD-ROM, also available from Digital Meme. For useful reviews, go to Midnight Eye and hors champ.

(2) ) I offer several other examples in the essays “Japanese Film Style, 1925-1945” and “A Cinema of Flourishes” in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema.

(3) I make this argument in Planet Hong Kong and the essays “Aesthetics in Action” and “Richness through Imperfection” in Poetics of Cinema.