Archive for the 'Asian cinema' Category

Angles and perceptions; with a note on Thai censorship

Hide your face

“Angles alter perceptions,” notes a recent Newsweek story. You bet, as we say in Wisconsin. But intriguing evidence emerges from new research into videotaped confessions.

Over 500 jurisdictions now record confessions on video, we’re told. In virtually all instances, there’s only one camera, and it shows only the accused. That means, in movie terms, there are no reverse shots of the questioner.

What difference does it make? Quite a lot, it seems.

In Newsweek‘s words, “When a camera shows only a suspect’s face, studies show, potential jurors are more likely to believe the confession was voluntary and the suspect guilty than when it shows the faces of both suspect and interrogator.” The problem may also infect judges. Experiments conducted by G. Daniel Lassiter at Ohio University found that a sample of 21 judges appraised the confessions as more voluntary when the camera framed only the confessor and didn’t show the police officer.

The obvious worry is that we can’t be sure that the confession is voluntary if we don’t get any sight of the questioner. To take an extreme, but not fanciful, possibility, maybe the person offscreen is holding a weapon. But even if the questioner isn’t threatening the confessor, his or her facial expression will help us appraise the whole situation more fully. Is s/he reacting with sympathy, anger, or neutrality? Do the questioner’s facial expressions set a context for the questions asked? We can’t know, and this absence of knowledge may encourage us, by default, to side with authority and presume that the confession is genuine.

In fiction films, sometimes the camera doesn’t give us the reverse angle. It may simply dwell on one character, often when she or he is delivering a monologue. A close analog to the videotaped confession occurs in Truffaut’s 400 Blows when an offscreen therapist questions the boy Antoine about his life.

Several effects flow from Truffaut’s choice of this technique. The handling suggests a quasi-documentary objectivity in recording Antoine’s replies. Making the questioner unseen suggests that she won’t become a significant character, rather a voice that typifies the impersonal authority of the detention facility. The fact that the questioner is a woman reminds us of Antoine’s relation to his mother, an important topic in the interview. In all, this strategy concentrates on Antoine, letting us see new sides of his past and his mind.

In other scenes, I’ve noticed that suppressing the reverse angle not only showcased the character we see but also rendered the scene’s action more suspenseful or ambiguous. Recall the famous first shot of The Godfather, which concentrates on the mortician and refuses to supply the reactions of Don Vito.

The shot gives full sway to Bonasera’s monologue. At the same time, by slowly zooming back, the shot creates a growing suspense. To whom is he speaking? What is the listener’s reaction? Only at the end of Bonasera’s plea, when he rises to whisper in Vito’s ear, does Coppola supply the view of Don Vito—a big theatrical entrance for this character and the actor playing him.

Less operatic is an early scene in Sauvage Innocence (2001), by Philippe Garrel. The filmmaker François is going over his dead wife’s belongings, which his friend has preserved. Garrel gives us an establishing shot of the action, then, as the friend continues to talk, the camera concentrates on Francois’s reaction to the letters, poems, and photographs. Although his expressions are somewhat ambivalent, at least we can see them.

But in the next scene, a single shot lasting about seventy-five seconds, Garrel withholds the reverse angles that we’d normally get when his protagonist speaks. The camera favors the friend, a minor character, who asks questions about François’s new film while feeding a baby. François replies that he’s having trouble finding a producer, and if this last opportunity fails, the project will be over.

Garrel doesn’t choose to reveal François’s expression as he reports this critical state of affairs: no reverse shots. We must infer his emotional state from his voice, his pauses and sighs, and his postures as he replies, rises, and sits down.

At most we can assume that he’s dispirited, perhaps because of his film’s slim prospects and the reminder of his dead wife.

In the scene, there’s one glimpse of his face, as he turns slightly, and—Tim Smith might be able to confirm this—I’d bet that most viewers zero in on him at that moment. (The movement is centered in the frame as well.) But that view is pretty brief and uninformative.

Overall, we have to infer François’s attitude from other cues than his expressions, and the results aren’t clear-cut. It seems to me that Garrel’s choices here are typical of one strain of “art cinema.” This storytelling tradition aims to make scenes somewhat indefinite in their meaning and to leave considerable room for spectators to play with various implications of the action.

Cutting and Social Intelligence

Some years ago I developed some ideas about the importance of shot/ reverse shot cutting in an essay called “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision.” (1)

One school of thought in film studies holds that cinematic conventions are wholly arbitrary social constructions. This implies that we have to learn to watch movies, just as we have to learn any arbitrary sign system, like Morse code or written languages. My essay argued that cinema, like painting, offers a continuum of conventions: some require a lot of exposure to learn, while others require much less. The easiest ones rely on regularities of everyday experience. I tried to show that shot/ reverse shot is a fairly easy convention to learn because it mimics the alternation between speaker and listener that we find in the turn-taking of ordinary conversation.

As my examples suggest, even if person A is doing all the talking, we don’t fully understand the scene if we can’t also monitor the reactions of B. By contrast, the shot/ reverse-shot patern keeps a running tab of the dynamics of the conversation. When a director wants to suppress information about B’s response, deleting the reaction shot can create uncertainty or suspense.

Confessions aren’t fictional films; we don’t assume that they use much staging. I’d argue that in videotaped interrogations any uncertainty about the listener’s reactions is quelled by our assumption that the officer is neutral or that any emotion she expresses has no effect on the confession. In other words, during a videotaped confession, any reaction on the part of B is presumed, perhaps wrongly, to be irrelevant. But in watching a fiction film, we tacitly assume that the director has suppressed B’s reaction in order to shape our experience in a particular way. The use of shot/ reverse shot, then, has a narrational function, governing the flow of story information.

We might posit this maxim of social intelligence: We understand an interchange more fully when we can see both participants’ responses to it, moment by moment. This notion underpins our old friend shot/ reverse shot, a convention that requires no specialized learning beyond watching and participating in conversations in real life. The absence of the reverse shot in videotaped confessions forces us to fill in one side of the conversation, and what we fill in may not be warranted.

Lassiter suggests a subtler effect of single-shot confessions. He has specialized in what psychologists call “illusory causation,” as explained in a 2002 press piece.

Criminal interrogations are customarily videotaped with the camera lens zeroed in on the suspect. Psychological research has shown that objects that are the focus of attention, are “more likely than less conspicuous objects to be judged the originators of a physical event, even when there is no objective basis for such a conclusion,” said G. Daniel Lassiter, author of the study. This phenomenon is referred to as “illusory causation.”

So by concentrating wholly on the suspect, the framing attributes a greater causal power to him or her than would a shot/ reverse-shot sequence.

I can’t at the moment see how this might come into play in a fiction film. In both of my major examples here, Bonasera and the baby-feeding friend have less causal power than the character whose response is suppressed. I suspect that the story context of film scenes provides our main sense of who has the causal power, which film style can reiterate or undercut.

Censoring Syndromes

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Syndromes and a Century was one of the best new films I saw last year. It has played at Venice, Vancouver (my quick remarks are here), Hong Kong, and other major festivals. It also won the best editing award at the Asian Film Awards. You can read the Variety review here. Jeff Reichert’s exhilarating appreciation appears, in keeping with the theme of the above entry, at Reverse Shot.

But now Apichatpong has withdrawn the film from theatres because local censors have demanded cuts. The objectionable portions include shots of monks playing with toys and a doctor kissing his girlfriend in a hospital. Details are available at Variety and Limitless Cinema. According to Screen Daily (not available free online):

Apichatpong questions why many other Thai and foreign films which contain excessive violence, nudity, coarse language, crude jokes on other ethnic groups, and monks doing stupid things did not suffer the same fate.

Below I reprint Apichatpong’s most recent statement and information about a petition that’s available online.

Free Thai Cinema Movement Petition

Statement by Apichatpong Weerasethakul with Bioscope, the Thai Film Foundation, Thai Film Director’s

Association, and Alliances.

I am saddened by what has happened to my film. However, this is not the venue to try to make SYNDROMES AND A CENTURY shown in Thai theaters. It is not my intention to use this opportunity to promote my work.

But, it is time to seriously think about what is going on with our censorship laws, so that the next generation of filmmakers will not face the same problems as us, and so that the Thai audiences can truly achieve a freedom of choice.

It is time we discuss whether all films, before being released, should be seen by the Buddhist council, doctors council, teachers council, labor council, the army, pet lovers group, taxi union, representatives from other foreign countries etc? Or, is it easier to turn our nation into a Fascist state so that we can live in harmony and don¹t have to waste time talking about democracy?

The system of the Thai Board of Censors needs to be evaluated. Their members’ relevancy and efficiency needs to be questioned, and we should decide whether the laws should be changed.

I would like to ask you to reflect on the censorship practices in our country and to provide us with advice at

http://www.petitiononline.com/nocut/petition.html

Later on, this Petition will be submitted to the Thai government. Your support will be a great contribution to our fight for one of our most basic rights – that of freedom.

I am grateful for your time and your participation. Thank you very much.

Warmest Regards,

Apichatpong Weerasethakul

KICK THE MACHINE FILMS Co., Ltd.

(1) It’s not available online; it was published in Post-Theory and will be reprinted in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema collection.

A many-splendored thing 12: The long goodbye

Two sides of the Triangle: Ringo Lam and Johnnie To.

My last day in Hong Kong, and still so much to say.

A few days ago I saw the new print of Patrick Tam’s Love Massacre (1981). It’s one of the stranger contributions to the Hong Kong New Wave of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The early stretches play as Antonioniesque scenes of alienation and loss, with a dash of Godard in the red/white/blue color design. About halfway through it becomes a movie about a stalker with a knife. Tam has great visual flair and devises some remarkable compositions and cuts, but I think that the film’s descent into gore comes too abruptly. We never understand the killer’s dementia, or his relation to his suicidal sister. Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia is as usual restrained and subtle in her performance, but such can’t be said for most of the other participants.

A few days ago I saw the new print of Patrick Tam’s Love Massacre (1981). It’s one of the stranger contributions to the Hong Kong New Wave of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The early stretches play as Antonioniesque scenes of alienation and loss, with a dash of Godard in the red/white/blue color design. About halfway through it becomes a movie about a stalker with a knife. Tam has great visual flair and devises some remarkable compositions and cuts, but I think that the film’s descent into gore comes too abruptly. We never understand the killer’s dementia, or his relation to his suicidal sister. Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia is as usual restrained and subtle in her performance, but such can’t be said for most of the other participants.

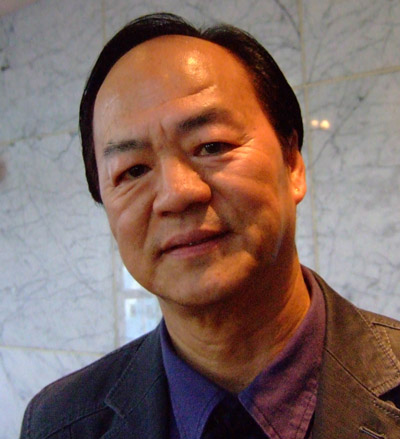

The seminar on Herman Yau’s films, “Herman’s Hermitage,” offered valuable critical commentary and a dialogue with Mr. Yau (right). A major cinematographer, Yau gained fame with two remarkably aggressive films, The Untold Story (1993) and Ebola Syndrome (1996). He has worked in many genres, lending a distinct local tang to cop dramas and even musicals. He’s a unique and energizing presence on the Hong Kong scene.

The seminar on Herman Yau’s films, “Herman’s Hermitage,” offered valuable critical commentary and a dialogue with Mr. Yau (right). A major cinematographer, Yau gained fame with two remarkably aggressive films, The Untold Story (1993) and Ebola Syndrome (1996). He has worked in many genres, lending a distinct local tang to cop dramas and even musicals. He’s a unique and energizing presence on the Hong Kong scene.

Two docus of note to fans of Asian film: In Development Hell (2007), Fukazawa Hiroshi chronicles the efforts of Teddy Chen to make Dark October, a film about Sun Yat-sen. As we follow Chen’s efforts, we learn of an earlier project undertaken by Chan Tung-man, father of prominent director Peter Chan Ho-sun. Tidbits about HK filmmaking emerge from comments by producers and directors.

Two docus of note to fans of Asian film: In Development Hell (2007), Fukazawa Hiroshi chronicles the efforts of Teddy Chen to make Dark October, a film about Sun Yat-sen. As we follow Chen’s efforts, we learn of an earlier project undertaken by Chan Tung-man, father of prominent director Peter Chan Ho-sun. Tidbits about HK filmmaking emerge from comments by producers and directors.

Yves Montmayeur’s In the Mood for Doyle (2006) follows Chris Doyle across a year of projects and interviews his collaborators, including Wong Kar-wai and Fruit Chan. Doyle appears somewhat calmer than I’ve seen him before (and certainly calmer than his reputation would indicate), and he shares some of his working methods.

Some points, such as the importance of place in determining a film’s style, Doyle has emphasized fairly often. But I’d never heard him say this before: “The choices you make push you in a certain direction, and that becomes what people call style.” Exactly right, methinks. Making a film is what technological historians call “path dependent”; one choice creates a limited but coherent set of future choices. The cascade of choices can precipitate into an overall stylistic pattern.

In a film with many good quotes, Peter Chan contributes another: “Working under the banner of a genre can give you more creative freedom.” In the Mood for Doyle and Development Hell would both be fine for festivals.

I have been written up a little in the Chinese-language press here and here. The loyal Golden Rock blogspot has pointed out that the stories misunderstood what I said in my blog about Johnnie To’s style.

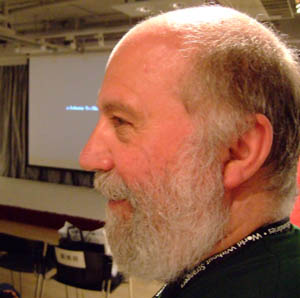

Speaking of Johnnie To, as I frequently am: Last week he invited critics Lorenzo Codelli (below) and Shelly Kraicer and your obedient servant to dinner at his brother’s restaurant in Sai Kung. It was a wonderful meal, from the French sausages to the Kobe beef, prepared by the estimable Dracula Kwong. I never thought anybody would ever say this sentence to me: “And now meet Dracula.”

Soon Mr. and Mrs. To were singing American pop hits of the 1960s, including Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Boxer.”

Ringo Lam, one of Hong Kong’s most celebrated filmmakers, dropped by.

Mr. Lam is the director of the middle section of Triangle, which I commented on in an earlier blog. In our conversation, he pointed out that the idea of taking off from another director’s story was something already present when he and Mr. To worked at TVB. The station would commission a 100-episode series (!), and either he or Mr. To would be responsible for the first five episodes. Then the next director would pick up the series and contribute another five installments, possibly taking the plots in entirely new directions. So this sort of serial production, a bit like Japanese linked verse, was already at work in Hong Kong popular culture.

Mr. Lam is known as bringing a level of harsh realism to the action pictures of the 1990s. In our conversation, he talked a lot about censorship troubles with the hard-edged School on Fire (1988). He also explained how he shot the jarring vehicle chase in Full Alert (1997) with virtually no retakes. “No problem! If other drivers see a crash or gunfire, they just drive around it.” Remarkably, Mr. Lam recalled reading our book Film Art when he was studying film in Canada.

Shu Kei has made a brief, gentle film called Ten Years, centered on a pair of dancers at the Academy for Performing Arts, where he is head of the School for Film and TV. Without words, accompanied solely by a Keith Jarrett piece, it tells its story through abstract compositions and carefully selected details.

A plush new local magazine, Muse, has published Vivienne Chow’s discussion of attitudes toward the festival. The story, not available online, discusses the festival’s efforts to broaden its public and seek commercial sponsorship. For many years after its launch in 1977 HKIFF ran as a municipal venture, but recently it went private. Now several high-profile companies like Giordano, Diesel, Starbucks, Shui On Land, and others support it. The festival has filled the central city with banners and billboards and created many red-carpet events, which generate press coverage and sizable local turnout.

Some long-time supporters feel that HKIFF has been pandering to the mass audience. They suggest that the festival’s principal mission was once to bring to Hong Kong the rare films, usually European, that wouldn’t be shown theatrically. Others resent the influx of viewers who aren’t strict cinephiles. One loyal festival attender is quoted in Chow’s piece: “The gimmicks and publicity brought in a lot of non-regulars who do not have much theater etiquette.” Long-timers complain of cellphone chatter and rude patrons.

As an outsider, I offer my $.02.

There are now a huge number of festivals, chasing the same films, lusting for red-carpet events. In Asia alone, Pusan, Tokyo, and Shanghai have become strong contenders, all more or less imitating Hong Kong. Moreover, the western world has finally recognized that Asia is a source of tremendous cinematic innovation, and now the big European and American festivals are cherry-picking films and filmmakers. If Wong Kar-wai can premiere his film at Cannes, why should he offer it to Hong Kong a month before? The HKIFF is hurt by its years of success: many of the filmmakers it introduced to the world are now snapped up by other festivals.

Just as important, the festival has offered comprehensive documentation of local cinema. Recognizing that Hong Kong film was largely unknown, the festival set about creating retrospectives and publications that brought to light the entire history of a great tradition. (On right, the festival’s book on the 1970s.) Without the precious catalogues published by the festival, both Chinese and westerners would know much less about Hong Kong cinema. The festival’s mission of education and scholarship has continued unabated, matched by the programs and publications of the Hong Kong Film Archive.

Just as important, the festival has offered comprehensive documentation of local cinema. Recognizing that Hong Kong film was largely unknown, the festival set about creating retrospectives and publications that brought to light the entire history of a great tradition. (On right, the festival’s book on the 1970s.) Without the precious catalogues published by the festival, both Chinese and westerners would know much less about Hong Kong cinema. The festival’s mission of education and scholarship has continued unabated, matched by the programs and publications of the Hong Kong Film Archive.

The festival shrewdly merged with a broader event, the Entertainment Expo, which included Filmart, the Asian Film Financing Forum, and the Asian Film Awards. Variety reports that a lot of business was done at Filmart, and the Awards were broadcast and rerun on Chinese television. In all, the festival seems to have created a unique identity for itself as a regional gathering place for both industry types and film fans.

Like all great festivals, this is really many festivals in one. Confronted by nearly 300 programs in 23 days, you’re in a vast cafeteria. You could, as I did, stick close to the Hong Kong retrospectives and archival shows. But you could also attend a rich array of avant-garde screenings, highlighted by the Paolo Gioli work. Or a documentary thread, including Enemies of Happiness and Nanking. Or a sampling of contemporary Asian film, showcasing dozens of works from South Korea, Japan, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, India, and on and on. Viewers craving contemporary European items had a chance to see eight films from Romania, eight from Germany, eight from the Nordic countries, and assorted titles from France, Italy, Portugal, and elsewhere; not to mention retrospectives of Visconti and Pedro Costa.

Add to this the enormous friendliness of everyone you encounter and the sheer exhilaration of being in this city. It would be ungrateful to ask for more. For the chance to see all these movies and wander through Hong Kong, I’d let Starbucks stamp its logo in my tooth fillings.

Will I see you here next year?

A many-splendored thing 11: Portraits

DB here:

Some miscellaneous glimpses of people I’ve run into at the Hong Kong International Film Festival. If the notion of six degrees of separation holds good, chances are you know some of them, or someone you know does.

Up top, the great actor Ti Lung, remembered from Chang Cheh films and perhaps most famous for his role as the honor-bound brother in John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow.

Below, Russell Edwards, Variety critic and reporter, with Bérénice Reynaud, programmer (San Sebastian festival, RedCat), professor (Cal Arts), and critic (author of books on Chinese film and on Hou’s City of Sadness).

Li Cheuk-to, one of Hong Kong’s most distinguished film critics and Artistic Director of the festival. Ah-to is at the center of HK film culture, having founded the Critics Society and played a central role in the festival for decades. This shot on the Star Ferry catches him in an unusual moment of calm; normally he’s doing nine things at once.

Ivy Shiau, Operations Manager of the festival, starting to set up the room for press and guests.

Subway Cinema boys on the go: at Kubrick, Grady Hendrix deals while Goran Topalovic buys books.

On the set of Triangle: Simon Yam chats with Twitchfilm‘s correspondent Todd Brown.

Also on the Triangle shoot: Kelly Lin and Antoine Thirion (Cahiers).

At the reception for the Asian Film Awards: Ho Yuhang (Rain Dogs) and Bong Joon-ho, who would win big with The Host.

Killing time between screenings at an outdoor cafe: Grace Mak, Hong Kong critic doing graduate work at the University of Singapore, and Nat Olsen, film and music maestro. A graduate of UW, he’s dj-ing all over Asia and hosting the site Hong Kong Hustle.

Here’s Sam Ho, Head Programmer at the Hong Kong Film Archive, keeping cool as we wait in line for a screening.

Here’s Yvonne Teh of Penang, huge fan of Asian film and proprietor of the Webs of Significance blog.

Note how my background skilfully keeps the cellphone motif going. Actually, if you photograph anything here but marine life, somebody with a mobile will be in the shot.

Jupiter Wong is the HK film industry’s top still photographer and the wildest man I’ve ever met. Upon meeting me this year, he said, “Why do you look so old?” He has gotten a haircut, but otherwise there’s no sign of domestication.

I met Athena Tsui when I first came to Hong Kong twelve years ago. A graduate of U Toronto, she has worked in many phases of film production, distribution, and exhibition. She routinely helps out the festivals with translation, guest wrangling, and planning. She’s been my supreme guide to HK film insiders’ gossip and to Mongkok shopping.

I couldn’t attend the talk given by Jean-Michel Frodon, editor of Cahiers du cinema, but I did see him outside another event. We first met in Shanghai and keep running into each other at various festivals.

Another old friend, Virginia Wright Wexman of Chicago, was leading a group of visitors to the festival. The smile is doubtless the result of her recent retirement from the University of Illinois–Chicago.

Peter Tsi is the boss of it all, the Executive Director of the Festival. You can usually find him multitasking.

Shu Kei, another friend from my first visit, is head of Film at the Academy for the Performing Arts. He has done everything–made films (see especially A Queer Story), distributed them, programmed the festival, and taught film aesthetics and production. His knowledge of cinema is encyclopedic.

Akiko Tetsuya is a perennial HKIFF presence. She has done a wonderful book on Brigitte Lin.

Shelly Kraicer founded one of the first Chinese cinema websites. He’s a prolific writer and an active consultant on Chinese film for Venice, Vancouver, and other festivals.

The very first person I came to know when visiting the festival in ’95 was the warm and generous Michael Campi. Michael is a pharmacist by trade and a devoted cinephile and festival consultant in his native Australia.

Frederic Ambroisine is an editor of the Paris magazine Kumite and is a busy producer of documentaries on Chinese cinema. If you own French editions of the Shaolin Monastery or One-Armed Swordsman series, you have bonus materials prepared by Fred. Below he’s rejoicing in his purchase of Cutie Honey action figures.

Other folks’ pix can be found if you trawl back through my previous entries. To all those whom I failed to snap, or whose shots didn’t come out well, I apologize. But all the more reason for you to return next year. Fame awaits you!

Speaking of other years….Two regular guests and old friends couldn’t attend this spring, so I can’t resist slipping in shots of them from the 2006 festival. First, Mike Walsh of Flinders University, Australia (and a UW grad).

And here’s Peter Rist of Montreal’s Concordia University, at last year’s launch of the book on Milkyway Image.

Finally, a shot of the wonderful Lisa Lu, star of many Shaws productions and other major pictures, such as Bertolucci’s Last Emperor. You can see her in a Li Han-hsiang frame I posted earlier.

I can hardly believe that the festival is coming to an end. I leave for home on Thursday, but I hope to tack on one more entry before I go.

A many-splendored thing 10: Li Han-hsiang, cont’d

Li and his legend

The Li Han-hsiang retrospective rolls on here at the Hong Kong International Film Fest. For my initial blog on the subject, along with relevant links, go here.

Li is chiefly known for his costume pictures, though he reveals a talent for more intimate fare, as seen in The Winter (1969), which I commented on earlier. His early HK films, like Lady in Distress (1957) and A Mellow Spring (1957), are fairly typical Mandarin-language melodramas, with comparatively high production values and centering on suffering heroines (played in both of these by Linda Lin Dai). The first is a rural romance, with some attractive landscape locations and night-for-night shooting. A Mellow Spring, an instance of the “tenement film” characteristic of 1940s-1950s Hong Kong cinema, takes place over a single day and moves among several families in an apartment bulding.

Li’s direction here is simple and traditional. He uses fairly distant staging, presenting shot/ reverse-shot breakdown of dialogues and camera movements that adjust to the characters’ movements. A moment of tension will be underscored by rapid cutting. There are occasional depth shots, but nothing that would be considered unusual for the 1950s in other national cinemas.

Perhaps the most unusual aspect to western eyes is a habit that Li relies on throughout his career. After a cut, a character may pop into the frame from left, right, or below, usually in close-up. Directors of martial arts films use this tactic in the 1960s and thereafter, but I was surprised to see it in the context of straight drama. It will recur in the Taiwanese films Li directed or supervised. I can’t say if it’s original with him or if he and his subordinate directors took it from another source, but it certainly tends to accentuate the reaction shot. In other directors’ action pictures these abrupt frame entrances becomes part of a captivating overall rhythm of cutting and figure movement.

In 1963 Li moved to Taiwan and founded the Grand studio. As he attests in the archive’s indispensable book, he was a poor businessman and Grand folded in a few years. His most acclaimed achievement there was Beauty of Beauties (1965), a spectacular historical saga. I’d seen it before, but the archive screening offered an opportunity to look more closely. Unfortunately, the original two-part release is unavailable, so a 155-minute version was shown.

It’s certainly an awesome achievement. Two or three exterior sets are enormous and crowded with soldiers, chariots, and masses of commoners. Clearly Beauty of Beauties was an effort to rival the behemoth pageants of Hollywood. The central plot, however, isn’t very visible in the shorter version. King Fu Chai has conquered the kingdom of Yueh, so Yueh’s king sends Hsih Shi, a beautiful village girl, to Fu’s court to seduce him. She succeeds in weakening the influence of his counselors, and after seventeen years (!) Yueh’s king gains the strength to rebel against the oppressors. The problem is that in making the short release version, the editors played up the scenes of crowd spectacle and took out most of the palace intrigue. The result is choppy, with some scenes interrupted midway and little effort to trace Hsih Shi’s growing sway over Fu.

More satisfying, in a lowbrow way, were Grand items like Storm over the Yangtse River (1971), a thriller in which Chinese guerrillas fight the Japanese occupation in the 1930s. Lots of spy-vs.-spy trailing, double-dealing, and bluffing are at the center here. The most Wellesian of the Li films I saw, this is full of steep angles and shock cuts. A good visual idea was the towering inn set, which allows Li to show action on different staircase landings simultaneously. Clearly he could direct unpretentious entertainment when he wanted to.

More satisfying, in a lowbrow way, were Grand items like Storm over the Yangtse River (1971), a thriller in which Chinese guerrillas fight the Japanese occupation in the 1930s. Lots of spy-vs.-spy trailing, double-dealing, and bluffing are at the center here. The most Wellesian of the Li films I saw, this is full of steep angles and shock cuts. A good visual idea was the towering inn set, which allows Li to show action on different staircase landings simultaneously. Clearly he could direct unpretentious entertainment when he wanted to.

Li and his league

Just as interesting as Li’s own Taiwanese pictures are those he supervised. Of the ones I saw, three were directed by Yeung So, and they offered instructive early examples of the contemporary melodrama called chiungyao films.

Chiung Yiao (Qiong Yao) was a popular writer of romance novels, and she gave her name to an entire genre of fiction and film. Probably the most famous chiungyao movie is Outside the Window (1973), starring Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia and centering on the forbidden love between a teacher and his student. Other chiungyao films I’ve seen center on cross-class romances or the miseries of the well-to-do. The rich young people listen to rock and roll and drive Vespas, and they live in modernistic houses with well-stocked bars and doily-covered armchairs. Chiung Yao’s work helped Taiwanese cinema attracted a new generation of viewers while showcasing a self-consciously modern Taipei culture.

Yeung So’s Many Enchanting Nights (1966), for Grand, was an early Chiung Yao adaptation. At first it seems to be about a high-school girl from a struggling family who falls in love with a rich man’s nephew. Gradually the narration shifts toward her parents and their domestic tensions, which revolve around the wife’s youthful love affair with the wealthy man. A long flashback fills us in on the backstory, and the weight of the film falls on the mother, who suffers not only abandonment by her lover (through a misunderstanding) but merciless attack by her self-destructive husband. Released in two parts, Many Enchanting Nights is a deliberately paced but always enjoyable exercise in suffering, miscommunication, flashes of lurid teen sexuality, impotent male rage, and female fortitude. There are many accessory pleasures as well. When our young lovers visit a bar, the theme from Johnny Guitar is rendered on electric guitar.

Yeung So’s Many Enchanting Nights (1966), for Grand, was an early Chiung Yao adaptation. At first it seems to be about a high-school girl from a struggling family who falls in love with a rich man’s nephew. Gradually the narration shifts toward her parents and their domestic tensions, which revolve around the wife’s youthful love affair with the wealthy man. A long flashback fills us in on the backstory, and the weight of the film falls on the mother, who suffers not only abandonment by her lover (through a misunderstanding) but merciless attack by her self-destructive husband. Released in two parts, Many Enchanting Nights is a deliberately paced but always enjoyable exercise in suffering, miscommunication, flashes of lurid teen sexuality, impotent male rage, and female fortitude. There are many accessory pleasures as well. When our young lovers visit a bar, the theme from Johnny Guitar is rendered on electric guitar.

The flirtation with incest in Many Enchanting Nights comes out with force in another Chiung Yao adaptation, Yeung So’s The Stranger (1969). A college girl is shadowed by a mysterious older man, and after he introduces himself she starts to fall in something like love with him. But flashbacks reveal to us that this attraction is, to say the least, misplaced. One odd aspect of this movie is the fact that until the climax we never see the face of the girl’s mother; her back is to us, she’s in shadow, or she doesn’t get a reverse-shot. Did Wong Kar-wai borrow this for his oblique portrayal of the spouses in In the Mood for Love? Like Many Enchanting Nights, The Stranger shows a flair for striking ‘scope compositions and saturated color design. And again we get those pop-in and pop-up frame entrances.

The flirtation with incest in Many Enchanting Nights comes out with force in another Chiung Yao adaptation, Yeung So’s The Stranger (1969). A college girl is shadowed by a mysterious older man, and after he introduces himself she starts to fall in something like love with him. But flashbacks reveal to us that this attraction is, to say the least, misplaced. One odd aspect of this movie is the fact that until the climax we never see the face of the girl’s mother; her back is to us, she’s in shadow, or she doesn’t get a reverse-shot. Did Wong Kar-wai borrow this for his oblique portrayal of the spouses in In the Mood for Love? Like Many Enchanting Nights, The Stranger shows a flair for striking ‘scope compositions and saturated color design. And again we get those pop-in and pop-up frame entrances.

The most renowned Grand film that Li Han-hsiang supervised is At Dawn (1968), by Song Cunshou. It’s a restrained but shocking attack on Chinese trial procedures. A young man goes off to his first day as a bailiff and is appalled by the fact that torture is used to extract confessions. Will he accept this for the sake of keeping a job, or will he quit? Unusually subdued, set mostly at night and in darkened interiors, At Dawn is a remarkable study of weakness and bad faith, and it deserves its fame as a Taiwanese classic.

Li and his lens

At the beginning of the 1970s, when he returned to Hong Kong, Li Han-hsiang was apparently settling into the style that would characterize his work for many more years. He was cutting faster. Lady in Distress and A Mellow Spring are shot in leisurely fashion, averaging, respectively, 10.4 seconds and 16.1 seconds per shot. In the late 1960s, The Winter comes in at 6.5 seconds, Storm over the Yangtse River runs 4.7 seconds average, and Li’s episode of Four Moods (1970) averages 4.6 seconds per shot. Of the late films I’ve seen in the retrospective, the averages run from about five seconds down to less than three (in Passing Flickers, 1982). These shot lengths are comparable to the quick cutting in the kung-fu films of the period.

As often happens with accelerated cutting, close-ups of the actors now predominate. Li likes to treat conversations in enormous facial views (not always in focus), quickly intercut on lines of dialogue. We still get the sudden frame-entrance cuts. And he really, really likes zooms.

Li’s reliance on zooms has often been condemned as laziness or opportunism, and there’s some evidence for this judgment. He astonished everyone by the speed with which he worked, churning out erotic tales, gambling comedies, and costume pictures. He recruited Lam Chiu-ha as cinematographer because Lam could finish 100 shots in a day. The zoom facilitated quick work, and Li evidently didn’t see it as looking tackier than a tracking movement. On one shot he asked Lam, “Why did you use a dolly? Wouldn’t a zoom-in be sufficient?” (1)

Nowadays the zoom is flourishing, serving to provide pastiche (Tarantino in Kill Bill) (2) or add “energy” to a scene. But in the 1970s it was associated with cheap and/or incompetent filmmaking. That wasn’t entirely fair: Truffaut and Rossellini had made good use of it in the 1960s, and Visconti, Fellini, Bergman, Satayajit Ray, and other major directors were relying on the zoom at about the time that Li was. So were most Shaw directors, notably Chang Cheh. I argued in Planet Hong Kong that martial arts directors like Chang integrated the zoom into the staccato rhythm of combat scenes. No technique is inherently cheesy or superb; everything depends on how it’s used. Does Li do creative things with his zoom?

Not as far as I can see. Sometimes he just zooms in to capture his beloved close-ups, or to create an explosive punctuation (as in kung-fu films). At other times, he uses the zoom, along with panning movements, to break down or reestablish the dramatic space, in the manner of Rossellini’s Rise to Power of Louis XIV (1966). In The Empress Dowager (1975), the young eunuch Kuo (David Chiang) acknowledges that he’s been sent to spy on the emperor (Ti Lung). As the emperor dismisses him, we zoom back.

Kuo leaves, and the emperor looks after him as the camera zooms to an even fuller framing.

The emperor turns away and walks to the right, the camera panning to follow.

Once the characters are settled into a new arrangement, Li zooms in on one advisor as he talks with the emperor.

Played out in a single shot, the passage uses the zoom to substitute for cut-in close-ups. To get fresh angles on his players Li doesn’t change the camera setup but rather makes them shift position. The pan-and-zoom combination can be found in many 1970s films, from Hong Kong and elsewhere.

Most commentators have considered Li’s erotic comedies of the 1970s and 1980s an embarrassment, but the Archive retrospective has unabashedly included several of them. It has also run the peculiar Passing Flickers (1982), a collection of comic and erotic scenes set in a film studio. Based on a column Li wrote for local newspapers, the film can’t be called good, but it does have fun revealing the bumbling and egotism of mass movie production.

Most commentators have considered Li’s erotic comedies of the 1970s and 1980s an embarrassment, but the Archive retrospective has unabashedly included several of them. It has also run the peculiar Passing Flickers (1982), a collection of comic and erotic scenes set in a film studio. Based on a column Li wrote for local newspapers, the film can’t be called good, but it does have fun revealing the bumbling and egotism of mass movie production.

For Hong Kong fans, it offers rare glimpses of the Shaw film factory’s work routines. We see Mitchell cameras, and we learn that the staff stored each actor’s period makeup and whiskers in a labeled box for quick access. We see the Hair Man fix coiffures, glue on beards, and occasionally manicure pubic regions. There’s also satire of local movie celebs, including a portrait of the sneaky independent producer Zhao (= Golden Harvest chief Raymond Chow?).

Tedious and mostly unfunny, Passing Flickers suggests that Li relaxed into an attitude of simply enjoying what he could get away with. Of his quickies, he remarked: “I made those film with my heart and soul. They may look like crap to you, but they’re gems to me.” Even in his hack days, Li remained a central figure in Hong Kong film.

(1) I take this information from Wong Ain-ling, ed. Li Han-hsiang, Storyteller (HK Film Archive, 2007), p. 214. My final Li quotation is from p. 166.

(2) The script for Kill Bill includes the instruction, “We do a quick Shaw Brothers zoom into her eyes.”

Lisa Lu in The Empress Dowager.