Archive for the 'Asian cinema' Category

A many-splendored thing 9: On, and over, the edge

Films from the Fragrant Harbor

Sorry to be late with this posting from the Hong Kong International Film Festival. The last three days have been mighty busy, including a morning of roundtables with journalists and local critics, a supper with Mr and Mrs Johnnie To, an encounter with Ringo Lam, and other escapades. Plus heavy viewings of classics by Li Han-hsiang. I hope to blog about all this before I leave on Thursday. In the meantime, I’ll catch up on what any good festival is about…the films. Or rather, the ones I’ve liked most in the last few days.

Paolo Gioli has been making experimental films since the 1960s. From one angle, his approach converges with the work of filmmakers like Ken Jacobs and Ernie Gehr. Gioli employs optical printing and other techniques to halt, fragment, and superimpose images, many of them from found footage. Perforations flutter across the screen and framelines dance; single-frame montage imparts hallucinatory movement to a static picture; negative and positive images bounce off one another. The very concept of a shot or of a film frame dissolves in this lovely work.

But Gioli’s originality goes beyond the tradition of recasting found footage. Anticipating recent gallery artists who rig up their own movie machines, he films with pinhole cameras made of buttons or seashells, or uses leaves to create an extra shutter. The results can be aggressive or lyrical, and I found them completely fascinating. The first of four programs of his work was my first sight of Gioli’s work. How could I have missed it?

All the five films in the set, mostly from the late 1960s and early 1970s, were very impressive. In Traces of traces (1969), the abstract whorls and speckles are made from filmstock pressed upon his skin and fingertips. According to My Glass Eye (1971) assaults us with a flurry of Muybridge-like postures and fluttering close-ups, all to a threatening drumbeat.

My favorite was the gentler Anonimatograph (1972), recomposed from a 35mm home movie from the 1910s and 1920s. The shots settle into layers, and as they peel off we see people in different phases of their lives, sometimes studying each other across the years. Family portraits become eerie silhouettes and cameos. Even gouges on the emulsion serve as testimony to time gone.

Mark McElhatten, an expert on experimental film, provided the catalogue essay and an enlightening introduction to the screening, as well as an after-film discussion. He pointed out Gioli’s fascination with the textures of the human body as they are shaped by time and space, and then captured on the skin of film itself. Film as a tactile medium: No surprise that Gioli is also a sculptor.

You can read more about his work in Mark’s detailed essay for a Lincoln Center retrospective. This is Gioli’s suitably sparse website, and here is a site offering a DVD collection (unhappily not including Anonimatograph).

Cold Blade (1970) is a very different affair. This swordplay classic directed by the versatile Chor Yuen for Cathay has been fairly hard to see. (My first viewing came in 1997, at a Brussels retrospective.) The print screened by the HK Film Archive was restored from a Cathay negative, supplemented by sound from a copy held by Marie-Claire Quiquemelle of Paris. The result was a stunning print with vibrant color. The story of the restoration can be found here.

Cold Blade (1970) is a very different affair. This swordplay classic directed by the versatile Chor Yuen for Cathay has been fairly hard to see. (My first viewing came in 1997, at a Brussels retrospective.) The print screened by the HK Film Archive was restored from a Cathay negative, supplemented by sound from a copy held by Marie-Claire Quiquemelle of Paris. The result was a stunning print with vibrant color. The story of the restoration can be found here.

Cold Blade begins with a graceful title sequence showing our two heroes practicing their signature moves in slow motion and floating aerobatics. These maneuvers will of course prove important at the climax. The story was written for the screen, but it’s as full of twists and double-dealing as a martial-arts novel. The cutting is frantically fast (average shot length of 4.4 seconds!) but always intelligible. Chor Yuen provides his characteristically crammed fight scenes. His long lenses create layers of pulsing foreground movement that yield intermittent views of his protagonists. All in all, a satisfying reminder of the first golden era of Hong Kong action film.

Then there was Baba Yasuo’s Bubble Fiction: Boom or Bust (2007), an international premiere that drew huge crowds and big laughs. Here’s one Asian film that won’t be remade in Hollywood; it’s already an unembarrassed riff on Back to the Future. Mayumi, a ditzy bar hostess, tries to prevent Japan’s financial collapse by returning to 1990 and blocking corrupt legislation. Her vehicle: a lemon-yellow Hyundai washing machine.

Then there was Baba Yasuo’s Bubble Fiction: Boom or Bust (2007), an international premiere that drew huge crowds and big laughs. Here’s one Asian film that won’t be remade in Hollywood; it’s already an unembarrassed riff on Back to the Future. Mayumi, a ditzy bar hostess, tries to prevent Japan’s financial collapse by returning to 1990 and blocking corrupt legislation. Her vehicle: a lemon-yellow Hyundai washing machine.

Naturally, Bubble Fiction is filled with retro music, dances, fashions, and hair styles, with plenty of in-jokes about J-pop culture and references to its Hollywood source. “Don’t tell me you came in a DeLorean?” a skeptic asks our heroine. Bubble-era Japan is tellingly satirized, with profligate salarymen in loose suits lined up and waving banknotes to flag down cabs. The director painstakingly reconstructed the Tokyo of the time, including elaborate desserts and hand-punched train tickets.

Of course catastrophe is thwarted, and Mayumi comes back to a sunnier future, having gained a father and a new place in the community. Lighter than air, full of ingratiating gags, and cleverly crafted on Hollywood’s script model, Bubble Fiction proved just the sort of good-natured movie that I needed after 3 ¼ films earlier that day. Fragrant Harbor filmmaker Tsui Hark once wisely remarked: “Sometimes it’s fun to be stupid.”

For credits and further info, check out the Pony Canyon site and Russell Edwards’ Variety review.

In the wake of Infernal Affairs, Hong Kong movies have been filled with undercover cops turning confused, bitter, and suicidal. On the Edge (2006) from the Herman Yau retrospective here at the festival, is one of the very best. Like Yau’s From the Queen to the Chief Executive, this starts from a social fact: Most moles returning to duty don’t last more than a few years. Why? On the Edge explores the possibility that the friendships forged in the underworld are more authentic and durable than the stern bureaucracy of law and order.

The film begins with mole Nick Cheung betraying his father-figure Francis Ng. When he tries to readjust to life in the force, other cops keep away, Internal Affairs bureaucrats trail him, and he’s kept out of the loop. His new partner Anthony Wong goads him and flagrantly pounds up suspects, as if to prod Nick into defending the lowlife he once moved among. He sinks into alcoholism and tries to win back his girlfriend. A finely judged scene shows him revisiting a nightclub at which he’d once won the Triads’ trust. He shifts awkwardly between the bravado of a gang member and the panic of an outgunned policeman.

The film begins with mole Nick Cheung betraying his father-figure Francis Ng. When he tries to readjust to life in the force, other cops keep away, Internal Affairs bureaucrats trail him, and he’s kept out of the loop. His new partner Anthony Wong goads him and flagrantly pounds up suspects, as if to prod Nick into defending the lowlife he once moved among. He sinks into alcoholism and tries to win back his girlfriend. A finely judged scene shows him revisiting a nightclub at which he’d once won the Triads’ trust. He shifts awkwardly between the bravado of a gang member and the panic of an outgunned policeman.

Thanks to a flashback structure, we see Nick’s rise in the gang juxtaposed to his slump once he’s back in uniform. Without being heavy-handed, the film juxtaposes a scene of Nick trying to return to civilian life with a parallel moment in his Triad days. It isn’t easy to advance two stories at once, but Yau manages it easily. There are also many sharp character bits, expressed—as customary in Hong Kong films—through confrontations and combats. A scene in nightclub builds tension as Ng and Wong, crook and cop, seize karaoke microphones to bark challenges to one another.

Without recourse to the flourishes of a certain Hollywood film on a similar theme, On the Edge exposes the anguish of a man cut adrift from the world that gave him his identity. Simple and modest, but with subtle touches (watch out for the disabled man on the handcart), Yau’s B-film aesthetic deals straightforwardly with plot, character, pungent locations, and a fine cast. You don’t need portentous symbols like a rat skittering along a condo railing. Just tell the story of one man who lost himself.

A many-splendored thing 8: The spice of life

Two more days at the Hong Kong film festival include…..

Seeing a lion dance auspiciously opening a new restaurant. I’d just eaten there last week, soon after it opened, with local filmmaker, critic, and educator Shu Kei. The meal included pig-lung soup; good!

Watching the unexpectedly solid Wo Hu (2006). Wong Jing is widely known as the great vulgarian of Hong Kong cinema; nothing is too lowbrow to be tossed into his movies. I like some of his work, but I worried when the opening credits of a serious picture like this listed Wong as producer. Despite my concerns, this turned out to be a strong cops-and-triads pic. The presence of Eric Tsang, Francis Ng, and Jordan Chan helps a great deal, and Marco Mak’s direction is efficient enough. The real strength is the script, with a plot that is unusually taut for a Hong Kong movie.

The cops have declared a mission to infiltrate the triads with 100, 500, 1000 moles—whatever it takes. The references to Infernal Affairs are evident (characters even mention the movie), but in some ways this is a subtler effort. The film follows three triads’ personal lives and interweaves the fate of a cop with his own secret. There are touches of humor, but mostly the mood is somber, accentuated by the dank, bleached-out look that’s so common today. There are sharp suspense passages and some genuine surprises.

The cops have declared a mission to infiltrate the triads with 100, 500, 1000 moles—whatever it takes. The references to Infernal Affairs are evident (characters even mention the movie), but in some ways this is a subtler effort. The film follows three triads’ personal lives and interweaves the fate of a cop with his own secret. There are touches of humor, but mostly the mood is somber, accentuated by the dank, bleached-out look that’s so common today. There are sharp suspense passages and some genuine surprises.

Wo Hu was much praised by local critics, and it seems to me the best of the recent crime films I’ve seen so far in the festival (Protégé, Undercover, Dog Bite Dog, and the surprisingly weak Confession of Pain). This is the one that could yield an interesting US remake. The title—get ready—translates as “Crouching Tiger.” The sequel, already announced, will be called Jia Lung: “Chasing Dragon.” The shamelessness of Hong Kong cinema isn’t dead quite yet.

Going on a rainy-day shopping circuit with Athena Tsui. Many of the old places supplying unusual and bootlegged DVDs have closed. Why? The government stepped up anti-piracy enforcement, and consumers can now get digital content online more easily. We did re-visit one place selling graymarket mainland versions of US, European, and Russian films, all for low prices (about US$3). Legit, I picked up mostly Japanese titles: Sabu’s Dead Run, the otaku hit Train Man, the Suo boxed set (didn’t have a DVD of Fancy Dance), and an unmissable item, The World Sinks, Except Japan. Go here for Twitchfilm’s coverage of the last-named.

The highlight was a trip to Comix Box in Sino Centre. It’s run by Neco Lo Che Ying, one of Hong Kong’s first independent animators, who started out in the 1970s. Neco was also the first to offer American superhero mags. Here he’s surrounded by some of his toys.

Thanks to Athena for the trip, the cocoanut-mango drink, and all the information about the HK film scene, including the factoids about Wo Hu.

Having dinner with Raymond Phathanavirangoon, who works for the energetic distribution company Fortissimo. Probably best known for handling Wong Kar-wai’s films, Fortissimo has established itself as one of the top distributors/ producers of ambitious international cinema (East Palace, West Palace, U-Carmen eKhayelitsha, Shortbus).

Among his other duties, Raymond makes presskits. This is seldom a creative endeavor, but Raymond’s results go far beyond the usual leaflet. He produces virtually museum-quality artifacts. His most flagrant kit promotes the Hungarian film Taxidermia, offering a marbled booklet in a shrink-wrapped styrofoam package.

Seeing James Yuen’s curious Heavenly Mission (2006). After several years in a Thai jail, young triad Ekin Chan wants to go straight. He asks an arms merchant to stake him to US$30 million, and he returns to Hong Kong to set up a vast charity. The cops don’t trust him, and neither do some of his old triad buddies. Problems ensue.

One of many crime movies screened in the Panorama section of the festival, this is neither the worst nor the best. The plot proceeds spasmodically, and our mysterious protagonist seems a little too passive. Nice to see Ti Lung again, though, playing an aging and pacific triad boss. Nice also to see for once Thailand treated not as hell but rather as purgatory, the place in which Ekin discovers spirituality and kindness. And, proving once more that there’s some little stab of pleasure in nearly every movie, we do get a nifty final shot.

Catching up with Soma films: Jouni Hokkanen, a regular at the HKIFF, gave me a sampler of several films he has made with another Finn, Simoujukka Ruippo. Their company is called Soma. You’ve probably heard of Soma’s most famous film, Pyongyang Robogirl (2001), which puts a traffic warden’s rigid moves to a techno beat.

Soma has made other films about North Korea, most ambitiously a survey of the nation’s cinema called The Dictator’s Cut (2005).

These entertaining and informative babies won’t be on YouTube. The Soma website is under construction, but it does give a list of the films, all of which would seem natural film festival choices.

Enjoying in an old-fashioned way Herman Yau’s Give Them a Chance (2003): The notion of a movie about how HK teenagers become breakdancing stars didn’t seem promising, but it turns out to be a sweet piece of work. Yau has always had sympathy for grassroots life here, and he makes his ensemble plausible and ingratiating.

The kids, including a mute boy who apparently can spin on his head all night, are at once clumsy and sensitive, like most adolescents. They live in high-rises, struggling with broken families, but they retain honor and idealism. They look out for each other and try to take everybody’s feelings into account, thereby creating even more awkward complications. It’s a pleasure to see movie youths who aren’t bullies or triad wannabes, just good-hearted kids who want to make something of themselves (with a little help from Andy Lau).

The kids, including a mute boy who apparently can spin on his head all night, are at once clumsy and sensitive, like most adolescents. They live in high-rises, struggling with broken families, but they retain honor and idealism. They look out for each other and try to take everybody’s feelings into account, thereby creating even more awkward complications. It’s a pleasure to see movie youths who aren’t bullies or triad wannabes, just good-hearted kids who want to make something of themselves (with a little help from Andy Lau).

Yau, a rocker himself, treats the clichés of the musical film with casual zest. Romantic rivalries flare up, health problems keep a promising dancer offstage, youthful energy collides with old-fashioned tastes, and corrupt promoters try to discourage naïve hopefuls. Of course there are lively dance numbers. In the process, alienated brothers come together and the kids’ efforts are crowned by their appeal to—who else?—the ordinary people of Hong Kong.

At a time when most HK directors seem wall-eyed for the Mainland box-office, here is a movie that is utterly local. It even has two English titles, Give Them a Chance and Give Me a Chance, just going to show that it wasn’t made for us Anglos. Actually, though, it speaks to anybody.

I’ll be blogging more about Yau’s work soon, since the festival is giving him a retrospective and a seminar. In the meantime, you can check his website.

A many-splendored thing 7: Li Han-hsiang

Enchanting Shadow.

A classic storyteller, in suitable surroundings

Film director Li Han-hsiang didn’t benefit from the 1980s-1990s explosion of interest in Hong Kong cinema. For one thing, most of his films were for Shaw Brothers, and those were hard to find on video. For another, Li worked in genres that didn’t attract many fanboys and fangirls. As a result, he’s not as well known as his Shaws compadres Chang Cheh, King Hu, and Lau Kar-leung.

Although opinions about his directorial skills vary, there’s no denying his historical importance. Besides making over 100 films, Li both shaped and reflected several trends in local cinema. A massive retrospective of his work has begun at the Hong Kong Film Archive during the festival, and it will continue well into May.

While several of Li’s films are now available on DVD through the Celestial library, the retrospective features many titles that are hard to see, and it samples the range of this important director’s career.

Li’s breakthrough came in the huangmei diao genre, the “yellow plum” opera. These operetta-like films tended to center on romantic tales of court life, often involving ill-fated lovers. Li’s Diau Charn (1958), The Kingdom and the Beauty (1959), and The Love Eterne (1963) helped define the huangmei picture. The films became flagship Shaws vehicles, showcasing vast sets, eye-searing color, and sweet music, and they won praise at Asian film festivals. Spurred by his success, Li went independent. He relocated to Taiwan and continued to make lavish costume dramas, most notably the two-part Beauty of Beauties (1966).

His gamble failed, and Li returned to Shaws to make The Warlord (1972), with Michael Hui. As Shaws began to pursue more sensational fare, Li proved surprisingly adept at erotic films and films about gambling. He returned to the costume drama too, as in The Dream of the Red Chamber (1977), with Brigitte Lin playing a male role (heard that before?). Li’s biopic of Emperor Puyi, titled The Last Emperor (1986), beat Bertolucci’s project to the screen.

Li also made small-scale films about local neighborhood life, like Rear Entrance (1960), and during his Taiwan stay he explored understated melodrama too. Clearly, a retrospective is overdue, and the Archive has done it up right.

The screenings run until 25 May. Along with the films, there’s a handsome book, Li Han-hsiang, Storyteller. It features in-depth essays, many interviews, and an annotated filmography. (I don’t find the book listed for sale on the Archive’s website, but its price is HK$128, and general ordering information is here.) The archive is presenting an exhibition of costumes and props from the films, including lingerie worn by one female star.

The Dream of the Red Chamber (1977).

I had little to say about Li in Planet Hong Kong because in the late 1990s the Shaws collection was inaccessible and I was able to see only a few of Li’s works properly. The titles shown at earlier editions of the HKIFF were certainly impressive, notably Enchanting Shadow (1960), based on the same story that is the source for A Chinese Ghost Story (1987), and the costume extravaganza Beauty of Beauties. Still, I thought that Li lacked the filmmaking élan of his friend King Hu.

I’ve now seen several more Li titles, and though I see no reason to revise my first impression, I’ve come to appreciate his distinctive virtues more. He’s by and large a woman-centered filmmaker, and his female protagonists tend to be energetic and enterprising. The Love Eterne is particularly interesting in its endorsement of women’s ambitions. I haven’t seen evidence that Li has a distinctive approach to staging or cutting, as some other Shaws directors do. His emphasis falls upon settings and costumes, presented in vivid color schemes and captured in graceful widescreen compositions.

Here are some thoughts on what I’ve watched in the series here.

Flower Drums of Fung Yang (1967): One of Li’s Taiwan pictures, this centers a young woman who, after being raped by bandits, takes up street performing. Trouble comes in the form of her husband, who resents her ability to support the two of them, and a rival singing troupe. The musical score consists of a single song played in a variety of moods. The standard conceit of a woman pretending to be a man enhances a sad tale of the hopelessness of women’s lot—a common Li theme.

The Winter (1969): The best of the Li’s I’ve seen in this go-round. Our hero is a shy restaurant-owner who can’t bring himself to admit he loves the girl next door. Simple and poignant, shot largely on location in a teeming street market, the film is unusually quiet for Li, and he displays resourceful use of the anamorphic ratio. The film has become a classic of Taiwanese cinema, and Tony Rayns tells me that its understated realism influenced Hong Kong’s New Wave generation of the 1970s.

Four Moods (1970): An episode film. I had seen the King Hu contribution, Anger, several times before, and it’s still the best in the quartet. Li’s own contribution, Happiness, is a story about a miller and the ghost he meets while fishing. Amiable, somewhat confusing in its attitude toward the miller’s daughter, this wouldn’t convince you that Li was a good director.

The Burning of the Imperial Palace (1982): Li was given the rare opportunity to film in Beijing’s Forbidden City, and he took full advantage of it: The pageantry of his splendid long shots makes today’s greenscreen vistas look insubstantial. But as Wallace Kwong explains in his essay in the Archive anthology, Li’s mainland collaborators demnded many changes in the storyline.

The film traces the rise to power of the girl Cixi, recruited to the young emperor’s harem and eventually becoming a rival to his wife. In elaborate, rapidly edited sequences, Li tells a captivating story of a weak ruler (played by a very young Tony Leung Ka-fai) and the strong women behind him, who are ready to strike deals with Western imperialists.

Reign behind the Curtain (1983): A continuation of Burning, and another engaging palace intrigue. The emperor fritters his kingdom away while Cixi produces a male heir and enters into a tactical alliance with the empress. After his death, the two women struggle with the eight-man advisory council, and eventually with each other. Cixi has turned from an innocent girl into a Machiavellian power-broker, all adding to the woes of China. Like its prequel, a gripping story and skilful performances.

Five rather different films! I look forward to more.

A home for Hong Kong films

When I first came to Hong Kong in 1995, the Archive was housed in a trailer. Now it has a lovely building in the tranquil neighborhood of Sai Wan Ho. The light, airy lobby boasts posters and an exhibition hall, currently illustrating the Li retrospective.

Law Kar has been a key player in preserving and interpreting the local film heritage. He went to school with John Woo and founded some of the first local university film societies. An important critic, he oversaw many of the festival publications that provided gweilos like me precious information. He has also written a fine book with Frank Bren on early HK film history. Recently retired as the archive’s Head Programmer, he still turns out for events, and I’m always happy to see him.

There’s a hiatus in the Li screenings for a couple of days, so I’ll post this now and catch up with other films in a later entry.

Betty Lo Tih in Enchanting Shadow.

A many-splendored thing 6: Tourist interlude

Hong Kong island, seen from the harbor.

Tourist images, plus a tribute to Gor-Gor

I thought I’d use one blog to squeeze together some tourist views that I snapped since my arrival for the Hong Kong International Film Festival on 17 March. I never get tired of looking at, and photographing, this amazing city. For you film geeks, I’ve added a coda on a sad movie topic.

Hong Kong consists of Hong Kong island, some other outlying islands, and the Kowloon peninsula, plus the New Territories north of Kowloon. You can shuttle between the main island and the peninsula by taxi, by subway, or by ferry. Like many locals and most tourists, I prefer the ferry because it yields gorgeous views like the one above.

But the ferry to the Central area of Hong Kong island has been redirected. The old terminal has been closed so that more land can be reclaimed from the harbor for highways and skyscrapers. A new, Disneyfied terminal has been erected in its place further down the shore. It looks like cardboard in daylight but can be pretty at night.

Still, the old terminal wasn’t given up without protest.

In front of the old terminal, where City Hall stands, there used to be lots of people hanging out. Now the place is largely empty because of all the construction. What remains are the metal silhouettes sitting, mobilephoning, and practicing tai chi.

A city devoted to shopping, Hong Kong has its own equivalent of the medieval cathedral: the shopping mall. Festival Walk, one of the biggest, has a large ice rink. Here’s one of my favorites, some of the twelve floors of the Times Square mall. But why is Lane Crawford everywhere here? What is Lane Crawford?

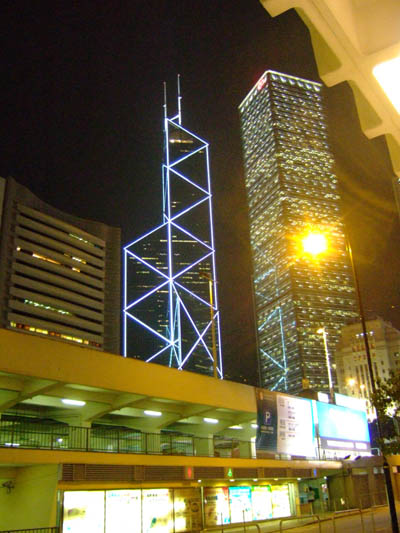

Grandiosity doesn’t afflict only mall architecture. The Bank of China, designed by I. M. Pei, was the biggest thing going when I first came in 1995. Now it’s dwarfed by Two International Finance Centre (in the right foreground at top of entry), which looks like the box the Bank came in. Pei’s zigzag symmetries and asymmetries are still mighty impressive, though.

In my neighborhood, Yau Ma Tei in Kowloon, the new construction thrusts ever higher. This is a view from the twelfth floor of my hotel.

Later this year west Kowloon will house a building 60 meters higher than the International Finance Centre. It will be, at least for a time, the tallest building in the world. Even multi-bean snacks start to look monumental here.

On the bus, things shrink to a more human scale. This is from my daily ride down Nathan Road to the Cultural Centre and the ferry. Two International Finance Centre is dimly visible in the left distance.

One movie note: Today was the fourth anniversary of the death of Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing, who committed suicide at the Mandarin Hotel in Central. He was one of Hong Kong’s most popular stars, seen in Days of Being Wild, Happy Together, A Chinese Ghost Story, He’s a Woman She’s a Man, and many other classics. Every year fans erect floral tributes along the sidewalk.

Thanks to Akiko Tetsuya and Yvonne Teh for guiding me to this moving display.

So much for tourism. Next time, back to the festival.