Archive for the 'Asian cinema' Category

A many-splendored thing 1: Academics and premieres

This year’s Hong Kong International Film Festival is mammoth—at 23 days, perhaps the world’s longest. It’s smoothly meshed with the HK Filmart, a trade gathering for buyers and sellers, the Asian Film Awards, and a slew of other events, all under the umbrella of Entertainment Expo. The goal, Timothy Gray points out in a communique in Variety, is to confirm Hong Kong as a regional media hub.

So many things have happened to me since my arrival, and so many impressions pile up, the diary form is for now the best way I can recount my doings. In the course of my stay, I’ll try for less fragmentary reportage.

Saturday 17 March

Back in my favorite city. Plane arrived two hours late around midnight Saturday, and the Internets connection in my room didn’t work. Went to bed, got a surprising 8 hours’ sleep.

Sunday 18 March

Joined my friends Mette Hjort and Paisley Livingston for a shopping expedition with their kids Erik and Siri to Sha Tin, a megamall in the New Territories. That night I stayed with them in their newly renovated home in Sai Kung, with calming views of a park and a bay. Slept 4 ½ hours; read about Alien Autopsy, prepping for a future blog.

Monday 18 March

A busy day. Most of it was spent at cozy Lingnan University (one area shown above), where Paisley and Mette teach. I got a little tour and met artist-in-residence Jane Dyer, who’s working on some lovely pieces involving books. She finds ’em, shreds ’em, paints ’em black…and turns them into disquieting sculptures.

Had an informal sandwich lunch with the students in the Visual Culture program, then a more extended attack on dim sum with Mette (center), Jane (right), and Meaghan Morris, head of Cultural Studies at Lingnan and another fan of HK action cinema.

Late afternoon, I gave my CinemaScope talk, with an addendum on HK cinema’s use of Scope. Good questions afterward.

With Meaghan I rushed off to Wanchai, where she lives and where I was slated to see the new Milkyway film, Eye in the Sky, at the Convention Center. After a comical mishap involving changing taxis, I made it to the Center just as the crowd was gathering. I hovered on the edge, uncertain of what to do next, when Yuin Shan Ding, Johnnie To’s right-hand man, saw me and gestured me in.

So I walked the red carpet, waiting for somebody to stop me. I should have remembered: This is HK, where such events are unbelievably informal.

Inside I caught up with Shan and got my ticket. At that moment I met another old friend, Athena Tsui, who was coordinating things in the foyer. Behind her Simon Yam, Lau Ching-wan (above left), Johnnie To, and Yau Nai-hoi were giving press interviews in the glare of TV lights. After snapping some pix, I went in and took my favorite seat, down front and center—where I also found another old Hong Kong friend, Li Cheuk-to, bustling about seeing to a dozen matters. Soon the major players came in too. Above, it’s Yau Nai-hoi, director of Eye in the Sky, on the left and producer Johnnie To on the right.

Then the ceremony started. The principals (To, Yau, Yam, Kate Tsui, Maggie Siu, and Lam Suet) got up on stage and said a few words of introduction. Simon claimed that he gained twenty pounds for his role, while Lam Suet proudly said that he had not.

Compared to To’s own directorial efforts, Eye in the Sky is more conventional genre fare. It’s very linear, giving us essentially a ninety-minute pursuit sequence. As a result, we get almost no backstory about the plainclothes cops (Yam and Kate Tsui) who are tailing heistmeister Tony Leung Kar-fai. It does recall other Milkyway films, which are often built around games of chase and disguise. It’s also very much a street film; you see a lot of the Hollywood Road area, and there are nice images of passersby caught unawares.

Here forward momentum is everything, with virtually no pauses for reflection or just catching your breath. Each scene seems caught on the fly, with aggressive smash-and-grab camerawork. Eye contrasts intriguingly with To’s Expect the Unexpected, which exhibits more control of the run-and-gun look and immerses us more thoroughly in the lives of its police protagonists. Still, Yau’s career will be worth watching, not least because Hong Kong needs to replenish its cadre of young directors.

Audience response to Eye was enthusiastic. Darcy Paquet has some quick first thoughts here.

I Am a Cyborg followed, but I have several other chances to catch it, and sleep beckons. Back to the hotel. Tomorrow, Tuesday, is the biggest day of my trip.

Homage to Mme. Edelhaus

Why are Americans polarized between francophobia and francophilia? Some people mock the French for liking Jerry Lewis, when most French people probably don’t even know who he is. Others think that France is the repository of world culture and represents the finest in writing about the arts, even though the Parisian intelligentsia can be pretentious and hermetic.

But we must face facts. When it comes to cinephilia, the French have no equals. They grant film a respect that it wins nowhere else. Spend a year, or even a month, in Paris, and you will feel like a Renaissance prince. This is a city where one lonely screen can run tattered prints of One from the Heart and Hellzapoppin!, once a week, indefinitely.

My first trip was too brief, only a week in 1970, but my second one—four weeks of dissertation research in 1973—left me exhausted. Reading Pariscope on the way in from the airport, I learned about a Tex Avery festival. I checked into my hotel and Métro’d to the theatre, where I and a bunch of moms and kids gazed in rapture upon King-Size Canary. Another time, also coming in from the airport, Kristin and I passed a marquee for King Hu’s Raining in the Mountain. Next stop, Raining in the Mountain. My memories of The Naked Spur, Ministry of Fear, Liebelei, Tati’s Traffic, and Vertov’s Stride Soviet! are inextricable from the Parisian venues in which I saw them.

Sound like a lament for days gone by? Nope. You can find the same variety on offer today. Of course the two monthlies, Cahiers du cinéma and Positif, have to take a lot of credit for this. Add Traffic, Cinéma, and several other ambitious journals, and you get a film culture unrivalled in the world.

Critics from Louis Delluc onward have led thousands of readers toward appreciating the seventh art. Historians like Georges Sadoul, Jean Mitry, Laurent Mannoni, Francis Lacassin, and others have enlightened us for decades. Academic film analysis would not be what it is without Raymond Bellour, Noel Burch, Marie-Claire Ropars, Jacques Aumont, and a host of other scholars. Above all stands André Bazin, the greatest theorist-critic we have had.

And the books! Arts-and-sciences publishing receives government subsidies; the French understand that books contribute to the public good. There are plenty of worse ways to spend tax dollars (e.g., trumped-up military invasions). The French, like the Italians, have created an ardent translation culture too. If you can’t read something in Russian or German, there’s a good chance it’s available in French.

I was reminded of the glories of Gallic film publishing when the mailman tottered to my door this week with twenty-two pounds worth of recent items I’d ordered. I haven’t even read them yet; otherwise, they’d be filed with Book Reports. Instead I want to spend today’s blog celebrating them as fruits of an ambition that has no counterpart in English-language publishing. All are grand and gorgeous and informative to boot.

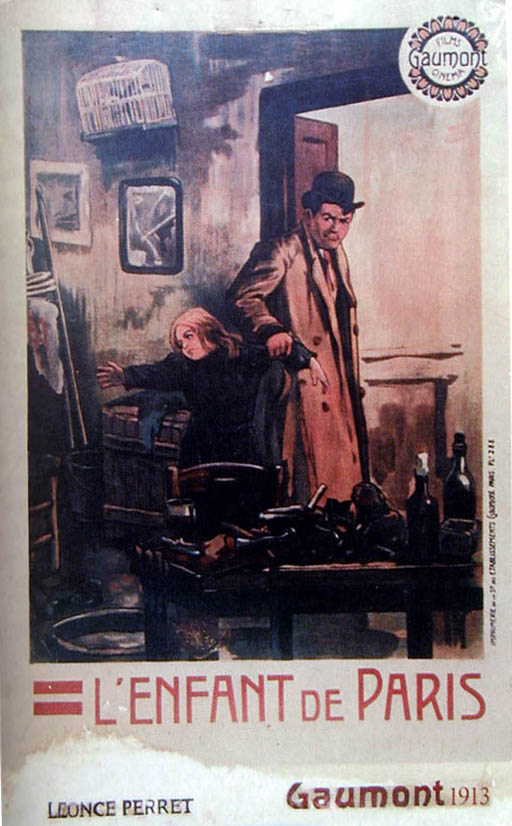

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret Cinématographiste. Association Cinémathèque en Deux-Sèvres, 2006. 2.5 lbs.

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret Cinématographiste. Association Cinémathèque en Deux-Sèvres, 2006. 2.5 lbs.

A biographical study of a Gaumont director still too little known. Perret was second only to Feuillade at Gaumont, and he performed as a fine comedian as well. His shorts are charming, and his longer works, like L’enfant de Paris (1913), remain remarkable for their complex staging and cutting. After a thriving career in France, Perret came to make films in America, including Twin Pawns (1919), a lively Wilkie Collins adaptation. He returned to France and was directing up to his death in 1935.

Although the text seems a bit cut-and-paste, Taillé has included many lovely posters and letters, along with a detailed filmography, full endnotes, and a vast bibliography. It compares only to that deluxe career survey of the silent films of Raoul Walsh, published by Knopf. . . .Oh, wait, there’s no such book. . . .Think there ever will be?

Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l’art des studios Disney. Galéries nationales du Grand Palais, 2006. 4 lbs.

Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l’art des studios Disney. Galéries nationales du Grand Palais, 2006. 4 lbs.

A luscious catalogue of an exposition tracing visual sources of Disney’s animation. Illustrated with sketches, concept paintings, and character designs from the Disney archives, this volume shows how much the cartoon studio owed to painting traditions from the Middle Ages onward. It includes articles on the training schools that shaped the studio’s look, on European sources of Disney’s style and iconography, on architecture, on relations with Dalí, and on appropriations by Pop Artists. There’s also a filmography and a valuable biographical dictionary of studio animators.

Some of the affinities seem far-fetched, but after Neil Gabler’s unadventurous biography, a little stretching is welcome. This exhibition (headed to Montreal next month) answers my hopes for serious treatment of the pictorial ambitions of the world’s most powerful cartoon factory. The catalogue is about to appear in English–from a German publisher.

Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. Orson Welles au travail. Cahiers du cinéma, 2006. 4 lbs.

Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. Orson Welles au travail. Cahiers du cinéma, 2006. 4 lbs.

The authors of a lengthy study of Citizen Kane now take us through the production process of each of Welles’ works. They have stuffed their book with script excerpts, storyboards, charts, timelines, and uncommon production stills.

The text, on my cursory sampling, will seem largely familiar to Welles aficionados; the frames from the actual films betray their DVD origins; and I would like to have seen more depth on certain stylistic matters. (The authors’ account of the pre-Kane Hollywood style, for instance, is oversimplified.) Yet the sheer luxury of the presentation overwhelms my reservations. A colossal filmmaker, in several senses, deserves a colossal book like this.

Alain Bergala. Godard au travail: Les années 60. Cahiers du cinéma. 2006. 5 lbs.

Alain Bergala. Godard au travail: Les années 60. Cahiers du cinéma. 2006. 5 lbs.

In the same series as the Welles volume, even more imposing. If you want to know the shooting schedule for Alphaville or check the retake report for La Chinoise (these are eminently reasonable desires), here is the place to look. Detailed background on the production of every 1960s Godard movie, with many discussions of the creative choices at each stage. Once more, stunningly mounted, with lots of color to show off posters and production stills.

Anybody who thinks that Godard just made it up as he went along will be surprised to find a great degree of detailed planning. (After all, the guy is Swiss.) Yet the scripts leave plenty of room to wiggle. “The first shot of this sequence,” begins one scene of the Contempt screenplay, “is also the last shot of the previous sequence.” Soon we learn that “This sequence will last around 20-30 minutes. It’s difficult to recount what happens exactly and chronologically.”

Emrik Gouneau and Léonard Amara. Encyclopédie du cinéma du Hong Kong. Les Belles Lettres, 2006. 6.5 lbs.

Emrik Gouneau and Léonard Amara. Encyclopédie du cinéma du Hong Kong. Les Belles Lettres, 2006. 6.5 lbs.

The avoirdupois champ of my batch. The French were early admirers of modern Hong Kong cinema, but their reference works lagged behind those of Italy, Germany, and the US. (Most notable of the last is John Charles’ Hong Kong Filmography, 1977-1997.) More recently the French have weighed in, literally. 2005 gave us Christophe Genet’s Encyclopédie du cinéma d’arts martiaux, a substantial (2 lbs.) list of films and personalities, with plots, credits, and French release dates.

Newer and niftier, the Gouneau/ Amara volume covers much more than martial arts, and so it strikes my tabletop like a Shaolin monk’s fist. There are lovely posters in color and plenty of photos of actors that help you identify recurring bit players. Yet this is more than a pretty coffee-table book. It offers genre analysis, history, critical commentary, biographical entries, surveys of music, comments on television production, and much more. It has abbreviated lists of terms and top box-office titles, as well as a surprisingly detailed chronology.

Above all—and worth the 62-euro price tag in itself—the volume provides a chronological list of all domestically made films released in the colony from 1913 to 2006! Running to over 200 big-format pages, the list enters films by their English titles and it indicates language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or other), release date, director, genre, and major stars. Until the Hong Kong Film Archive completes its vast filmography of local productions, this will remain indispensable for all researchers.

Above all—and worth the 62-euro price tag in itself—the volume provides a chronological list of all domestically made films released in the colony from 1913 to 2006! Running to over 200 big-format pages, the list enters films by their English titles and it indicates language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or other), release date, director, genre, and major stars. Until the Hong Kong Film Archive completes its vast filmography of local productions, this will remain indispensable for all researchers.

Mme. Edelhaus was my high school French teacher. A stout lady always in a black dress, she looked like the dowager at the piano during the danse macabre of Rules of the Game. She was mysterious. She occasionally let slip what it was like to live under Nazi occupation, telling us how German soldiers seeded parks and playgrounds with explosives before they left Paris. When I asked her what avant-garde meant, she replied that it was the artistic force that led into unknown regions and invited others to follow–pause–“in the unlikely event that they will choose to do so.”

For three years Mme. Edelhaus suffered my execrable pronunciation. When I tried to make light of my bungling, she would ask, “Dah-veed, why must you always play the fool?”

I suppose I’m still at it. But thanks largely to her I’m able to read these books as well as look at them. She opened a path that’s still providing me vistas onto the splendors of cinema.

Welcome back, Suo-san

Suo Masayuki, one of Japan’s most ingratiating directors, found an international triumph with Shall We Dance? (1996). He had started his career with an odd little softcore porn film, Abnormal Family (1983), shot as an admiring pastiche of Ozu’s style. His Fancy Dance (1989) was also fun, but he really hit his stride with Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t (1992), which remains a sure-fire crowd pleaser.

Suo worked comic variations on an ingenious theme: How Japanese youth fail to appreciate the beauty of their traditional culture. The garage-band ska singer in Fancy Dance is obliged to retreat to a monastery, where he discovers that Zen is really, really cool. Sumo Do converts sullen college kids to the virtues of ritualized wrestling. Shall We Dance? works in reverse, obliging an uptight salaryman to rekindle his marriage by learning ballroom dance. Suo’s films celebrate pleasurable fusions between Asian and Western cultures.

Suo’s meticulous, understated style is a kind of modern revision of Ozu’s. Fancy Dance and Sumo Do pay homage to the master’s college comedies, and in Shall We Dance? the first tracking shot occurs when the hero takes his first tentative dance steps. In Figures Traced in Light, I mention Suo as part of that trend toward planimetric shooting and compass-point cutting I discussed in an earlier blog. As you see from the opening images, he tries out the precise sort of graphic matching between shots that was a hallmark of Ozu’s style.

Suo has been very quiet for the last decade, but now he’s back. I Just Didn’t Do It is arousing keen local interest, partly because of its controversial subject matter. Japan is known as a low-crime society, but gradually questions of police brutality have emerged. Suspects can be kept in custody for up to 23 days, and unique among industrial nations, 95% of all people arrested confess!

Suo has been very quiet for the last decade, but now he’s back. I Just Didn’t Do It is arousing keen local interest, partly because of its controversial subject matter. Japan is known as a low-crime society, but gradually questions of police brutality have emerged. Suspects can be kept in custody for up to 23 days, and unique among industrial nations, 95% of all people arrested confess!

In Suo’s new film, a young man is accused of groping a schoolgirl in the subway. It’s a daring move for a director known for light comedies. The film stars Kase Ryo, from Letters from Iwo Jima, and veteran Yakusho Koji, seen most recently in Babel. Read more about it here, noting that the Economist’s contents tend to evaporate into the pay-only archive. The film’s official website, in English, is here.

I Just Didn’t Do It, Suo says, is a film “I simply had to make.”

My name is David and I’m a frame-counter

DB here:

Elsewhere on this site and in Figures Traced in Light (Chapter 1) and The Way Hollywood Tells It (second essay), I sometimes say rude things about the rapid editing in today’s films. But I’m actually a fan of fast cutting–when it’s precise, functional, and thoughtful. Most directors today don’t think about their cuts. Godard: “The only great problem of cinema seems to be more and more, with each film, when and why to start a shot and when and why to end it.”

My interest in fast cutting goes back to the 1960s, when I was first reading Eisenstein and seeing fims by Godard, Truffaut, Hitchcock, and, yes, Richard Lester. At first I would wind sequences backward and forward on a 16mm projector, stopping to pull the film off the reels to hold up to the light. For my dissertation on French cinema of the 1920s, I had a chance to examine films by Abel Gance, Jean Epstein, Germaine Dulac, et cie on editing tables or rewinds. In quickly-cut passages, the patterns of shot-length showed how a director could control the visual pace.

Over the years, when I studied 35mm film prints regularly, I periodically returned to my love of rhythmically cut passages. I studied Dreyer’s Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, the work of the Soviet Montage directors, and Asian action movies, from 1920s Japanese swordplay items to 1990s Hong Kong martial-arts sagas. Somewhat surprisingly, I found that Ozu, as in everything else, was there too; a lot of his intermediate spaces (landscapes, objects in rooms) are cut arithmetically.

By examining 16mm and 35mm prints, I could measure shot lengths in frames. In a sound film, a 24-frame shot would last a second on the screen. Things were trickier in gauging the cutting of silent films, since they were shown at rates between 16 and 24 frames per second. But at least the number of frames per shot gave me a sense of rhythmic relationships. A sequence in Jean Epstein’s Chute de la Maison Usher (1928) displays an arithmetical unfolding that would yield a distinct tempo at any projection speed of the era.

Directors have been counting frames for a long time. Experimental filmmakers like Brakhage did. Ozu had a special stopwatch built to register feet and frames during filming. Hitchcock cared about frame counting too. In Film Art‘s chapter on editing (pp. 224-225 of the new edition), we show how the gas station fire in The Birds gains impact from its steadily shorter shot lengths. The first shot lasts 20 frames, the second 18, the third 16, and so on down to 8 frames.

In sum, frame counting is one valuable way to find how a director can govern the pace of our pickup. When shots come this fast, our involvement can quicken as well.

When 35mm plays us false

For silent films, counting frames can be a problem if you have a “stretch-printed” copy. Since silent films often ran at something less than 24 frames per second (sound speed), some later film versions have been printed to repeat frames at certain intervals, to stretch out the print to 24 fps. That makes it easier to add a synchronized score to the print.

In the 1970s the Soviets were big fans of this procedure, rereleasing many classics by Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and others in stretch-printed 35mm and 16mm copies. The Soviet Montage filmmakers definitely counted frames, calculating the shots to play off each other rhythmically, so adding extra frames spoiled things. Worse, the stretch-printed versions often played sluggishly at sound speed, making the action spasmodic and blurring the figures. The result completely wrecked the rhythmic effects the directors were after. Even today, stretch-printed copies of Eisenstein’s Strike are in circulation.

Videotape and the 3:2 pulldown

Videotape arrived. The first Betavision players measured something–a little tally counter clicked away–but you couldn’t be sure what was being counted. Then came digital displays that measured hours, minutes, and seconds. But what about frames? When I tried to count frames on videotape, I found that the figures didn’t match those I got from film frames.

To see why, we have to remember that television developed its own frame rates. The technical details can get pretty daunting; see here for one account. I also recommend Jim Taylor’s DVD Demystified and Kallenberger and Cvjetnicanin’s Film into Video. Still, we non-engineers can get a general sense of what’s at stake.

There are two primary television standards, NTSC and PAL. NTSC (for National Television System Committee) is used primarily in North America and Japan. PAL (Phase Alternating Line) is common throughout Europe and Asia. Because NTSC video operates at a 60-Hertz refresh rate, the rate for individual frames is close to 30 per second. (Actually, it’s 29.97 fps.) The problem is this: Do you run 24-frame movies at 30 frames per second on television? This would make them look speeded up. Or do you pad out a second of film to fit a second of TV? American engineers took the second solution and created the so-called 3:2 pulldown.

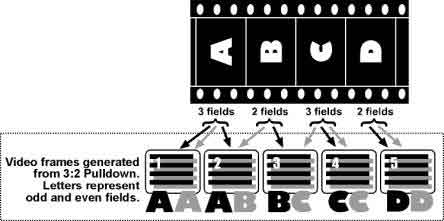

In interlaced video, each “frame” is really two venetian-blind image fields presented as one image on your screen.(1) In the 3:2 pulldown, some film frames are selectively repeated to fill out the video playback format. The film is converted to video by making two fields from one film frame and then three from the next frame. Here is a useful diagram from a site on video transfer.

The 3:2 pulldown preserves three of the original four film frames (video frames AA, CC, and DD above).

But you don’t see this exactly this result when you jog/shuttle through a videotape frame by frame because the VCR has been engineered to display the 3:2 pulldown slightly differently. Stepping through a videotape, we find that some frames will show phases of movement and some repeat a phase. Depending on your playback machine and the tape itself, you may get varying patterns. Usually I see four video freeze-frames decomposing a movement, then they’re followed by an extra frame in which nothing changes.(2) That process turns 4 film frames into 5 display frames. Adding 6 repeated frames to the original 24 frames yields 30 video frames a second. I find that you can get a rough sense of the number of frames in the original shot by ignoring the repeated frames in the video display, but the video frames showing decomposed movement may or may not correspond to the actual film frames.

Laserdiscs and the frame count

Those heavy, rainbow-flashing 12″ discs: Cinephiles loved ’em. They gave us a sharper picture, properly letterboxed, along with terrific sound. Aficionados today still prefer the rich digital sound of laserdiscs to the compression of many DVDs.

Most laserdiscs used the CLV (Constant Linear Velocity) format, which preserved and even exaggerated the effects of the 3:2 pulldown. Counting frames meant stepping through the stills and ignoring the repeated ones, as with videotape, but often the coupled frames (AB and BC above) shivered wildly. But in the high-end CAV (Constant Angular Velocity) format, laserdiscs were able to make each stored frame pristine. This is why people thought that laserdiscs would be used archivally, for storing paintings, photographs, manuscript pages.

A bonus of the CAV format was that in transferring motion pictures to disc, one film frame could be matched to a single video frame. In fact, each film frame was assigned its own number, so the counter display spit out digits with blinding speed. During normal playback, the 3:2 repeated frames were added in, but in STEP mode, CAV laserdiscs gave you the original film frames one by one–steady, crisp, and bright. Frame-counting gained a new piece of hardware.

DVD and frame counting

Laserdiscs used optical analog technology for the image track. But consumers wanted something easier to handle, on the model of the music CD, so in came digital image technology via MPEG-2 and the DVD.

Despite all the differences between digital video and film (color, resolution, artifacts, etc.), DVDs in the NTSC format gained one advantage over tape. Like CAV laserdiscs, they could preserve the 24-frames-per-second rate of film. Essentially MPEG-2 technology encodes the film frame by frame. Flags on the DVD instruct the player to regenerate extra frames during playback. For a more detailed explanation, go to Dan Ramer’s article here.

The result is that during freeze-frame viewing, a DVD can yield the original film frames. Watch the Universal DVD of The Birds, and the frame-counts correspond to the 20-18-etc. layout we discovered on a 16mm print. Your remote’s STEP button moves through the original frames, hiding the repeated ones that were shown during normal playback.

But not always. DVDs can sometimes play us false.

Before the DVD was a gleam in Warren Lieberfarb‘s eye, I studied King Hu’s wonderful A Touch of Zen on an editing table. There is a lot of frame arithmetic in the editing. During one swordfight, the mysterious stranger leaps away from the blows of Miss Yang and lands in a medium shot. He steps back, tipping up his face to reveal that she’s bloodied his head. He stares in astonishment. The shot lasts only 20 frames.

Yang stands still, holding her sword at the ready. The shot lasts a mere 9 frames, which dynamizes her stillness.

The stranger turns and runs out of frame in another twenty-frame shot. The static shot of Miss Yang now becomes an abrupt punctuation, and the stranger’s panic registers on us more sharply by being caught up in a repetitive rhythmic pattern.

Yang plunges after him, in a twelve-frame shot.

All four shots add up to less than three seconds of screen time, but they’re completely legible. It seems to me that the shots accentuate a pause in the fight by inserting a striking micro-rhythm, and then they dissolve that by letting the fighters continue the combat. Would that today’s filmmakers thought out their cuts so precisely! (If you want to learn more about King Hu’s editing style, see my Planet Hong Kong and the essay on him in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema.)

But if you examine these shots on the US DVD of A Touch of Zen, you’ll find that the number of frames is way off from the film. The first and third shots run 25 frames each, not 20 frames; the second shot runs 11 frames (instead of 9), and the fourth 15 (instead of 12). Why? Inspection reveals our old friend, the 3:2 pulldown, at work. Improper authoring has left in the frames that should be jettisoned in step playback.

An even more severe instance: The sequence from Epstein’s Fall of the House of Usher that I admired in my dissertation days. It has become hash on the US DVD. When I try to count frames, I find that apparently the silent original has been stretch-printed and subjected to the 3:2 pulldown. When I click through the frames on a DVD player, I find that many frames are repeated, and some shots have doubled in length.

The lesson: Not all DVDs are created equal, or equally accurate in their correspondence with the original film.

What about PAL?

NTSC interlaced video has a 60-Hertz refresh rate. But PAL has a 50-Hertz one. That means not 30 video frames per second but 25. What do you do in transferring a film? The obvious answer: You speed it up.

Films shot at 24 frames per second tend to run at 25 in PAL videos, both tapes and DVDs. As a result, many films on European video run shorter than they did in the theatre, or on American DVDs. For example, Preminger’s Where the Sidewalk Ends runs 94:41 on the Fox DVD, but the same film, known as Mark Dixon Detective, runs 90:49 on the French DVD release. That’s a difference of nearly four minutes. PAL video playback of a 24 fps movie runs about 4% shorter than the original. For this reason, some European films are shot at 25 frames per second, to facilitate transfer to PAL.

So counting frames on a PAL videotape or DVD won’t necessarily mislead you on the number of frames, since none is repeated. That’s the case with our Touch of Zen example. Both the UK and the French DVDs of King Hu’s film yield the correct frame-counts for the shots in question. We just need to remember that each frame is onscreen for a tiny bit less time. In other words, each shot will contain the right number of frames, but that shot will be briefer in screen duration .

Note to Sátántangó fans: Yes, that means a much shorter movie. The PAL DVD available from England’s Artificial Eye claims to run 419 minutes; if you disregard opening and closing credits, the film runs a shade under 400 minutes. But the 35mm version I clocked here runs 434 minutes sans credits. So if you want to add 34 minutes to your life, watch the import DVD.

Note to Asian cinema fans: For reasons I don’t understand, many Hong Kong DVDs yield very blurred and vibrating still-frame images, not corresponding to the frames of the original film. These discs may be using a downmarket authoring process, or there may be problems converting to and fro between PAL and NTSC.

Progressive scan

This all applies to interlaced video, the original television broadcast format. Now we have progressive-scan video, for plasma and LCD displays and computer monitors. A progressive display, still adhering to the 60-Herz standard, is rigged to preserve the right number of film frames without repeating any.

But it does so by in effect combining two film frames together, and the step function may skip over several frames, or create a blurred composite that isn’t there on any frame. This is especially apparent on media-player computer software.

When I run my Touch of Zen shots on my computer, I get wildly abbreviated frame-counts in Step mode. In WinDVD, for instance, the first shot of the UK DVD registers as 8 frames, not 20; the second as 3 frames, not 9; the third as 9 frames, not 20; and the fourth as 6, not 12. Same thing for Epstein’s Fall of the House of Usher. On a tabletop DVD player there are more frames than in the original film; on my player’s software, there are fewer.

For this reason, I’d avoid trying to count frames on a computer’s media player.

So…..

Frame-counting is a nifty tool for discovering some secrets of filmmaking, but when we work from a video copy, we need to keep in mind the constraints of the various formats. And whenever possible, check the film!

(1) To complicate things, the scanning of alternate raster lines never yields a single complete frame. Before the image is fully completed at the bottom, it’s being refreshed at the top! To this extent, the video frame doesn’t have the stable, singular identity of a film frame. It can be encoded to correspond to a film frame, but as an image display, even a frozen frame is always in the process of being filled in. It’s just that our eyes, not designed to track such small-scale processes, are fooled.

(2) A quick sampling of my old VHS tapes shows that occasionally a tape doesn’t exhibit effects of the 3:2 pulldown. My Facets VHS copy of Where Is the Friend’s Home? plays back on two machines without any repeated frames. Perhaps this comes from making the transfer from a PAL master tape?