Archive for the 'Asian cinema' Category

Updates and outtakes (in which we try, perhaps in vain, to catch up with ourselves)

Exiled

Kristin writes:

“The Hobbit Film: New Developments” (January 13, 2007)

In this entry I discussed Bob Shaye’s recent claim that Peter Jackson would never get a chance to direct The Hobbit for New Line. I mentioned that one of the factors involved in the negotiations about who would direct is that the production rights will eventually revert to producer Saul Zaentz. I didn’t know the length of the option on those rights, which New Line currently holds. The January issue of the fantasy/sci fic magazine Locus says that the rights will revert to Zaentz in 2009.

Zaentz had owned the rights since the mid-1970s and sold them to Miramax in early 1997. Miramax had the two-film version of The Lord of the Rings in pre-production for about 18 months and then sold the rights to New Line in August of 1998. I don’t know what the source of Locus’ information is, but a twelve-month option would seem pretty plausible.

If that information is correct, New Line only has about two years to get the actual making of the film underway. It takes years for any big film to lumber into production in Hollywood these days, so the studio doesn’t have a lot of room to wiggle.

“By Annie Standards” (December 14, 2006)

Here I talked about methods for publicizing animated features. One way, I suggested, would be to foster audience interest in the various animation awards other than the Oscars. I remarked, “Under Academy rules, only three animated features can be nominated in any year unless sixteen or more such features are released that year. Then the number of nominations jumps to five, but so far that hasn’t happened. It may finally happen this year, if all sixteen features currently under consideration qualify under Academy rules.”

Close, but not close enough. On January 11, Variety announced that one film, Luc Besson’s Arthur and the Invisibles, had been disqualified as an animated feature. To qualify, a film must have at least 75% animated footage, and Arthur has too much live action.

With the number of qualifying features down to fifteen, only three can be nominated. Probably Cars will win, as I predicted in the original entry. It just won the Golden Globe in the newly established Animated Film category.

“Snakes, No, Borat, Yes: Not All Internet Publicity Is the Same” (January 7, 2007)

Here I suggested some reasons why Snakes on a Plane failed at the box office and Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan succeeded, despite the fact that both garnered considerable fan-generated publicity on the internet. I mentioned that Sacha Baren Cohen had appeared on talk shows in character as Borat rather than in persona proper: “Each appearance by “Borat,” supposedly there to talk about the film, ended up being a hilarious performance by Cohen, ad-libbing on everything around him—the chairs, the coffee mugs, the cameras, the audience. Spectators ended up with one impression about the film: it was about this incredibly funny guy doing incredibly funny things.”

Trying to correct the widespread assumption that Borat was an improvised film, the January 8-14 issue of Variety ran a story about how Cohen worked with three scriptwriters, Peter Baynham, Dan Mazer, and Anthony “Ant” Hines: “The scribes even concoct Cohen’s dialogue for his promo appearances on ‘The Tonight Show’ and ‘Live With Regis and Kelly.’” Although Cohen presumably ad-libs to meet specific circumstances of each talk show, the publicity appearances are even more controlled by Cohen than I had assumed.

I also remarked that it is difficult to judge the degree to which the film manipulated the scenes of Borat’s encounters with real people. Especially in terms of editing and sound techniques, there was clearly much opportunity for this manipulation. The same Variety story goes on to say, “Much of the script had to be altered depending on how situations unravel. This means the writers ultimately end up producing the equivalent of multiple scripts, much of which ends up on the cutting room floor.” I’m not sure how chunks of scripts can end up on the cutting-room floor, but the point is that the filmmakers were carefully stitching the “documentary” scenes together on the script level and presumably would do so through stylistic means as well.

David writes:

Back to the Hotel

The Uchoten Hotel (aka Suite Dreams, blogged here) has acquired yet another English-language title: Hotel Avanti. It made it to #93 on Variety‘s list of the world’s 100 top-grossing films, with $51 million box office in Japan and none yet recorded overseas.

Speaking of Variety‘s list, the highest-grossing non-English language item turns out to be Bong Joon-ho’s Korean hit The Host (#59 at $84 million), due out in the US any month now. Only ten non-English-speaking films made the top 100, and of those, three were European (including Volver) but all the rest were Asian: Chinese (Fearless), Korean (The Host and King and Clown), and Japanese (Tales from Earthsea, Umizaru 2 Limit of Love, Hotel Avanti, and Japan Sinks–no rude remarks, please).

The entire list is in the 15-21 January hard copy of Variety, p. 15, but evidently it isn’t yet available on the paper’s site.

More on Johnnie To

In an earlier blog I praised Johnnie To as a director who shot and cut PTU smoothly and crisply. I waited through the fall, hoping somehow to see To’s latest, Exiled, on the big screen at one festival or another. No such luck. So last night I broke down and watched the DVD. Making full use of the widescreen format, To shows that classic technique can be at once rigorous and imaginative.

Exiled was more visually engaging than any US film I can recall last year, including Miami Vice. It immediately became my Best Film of 2006 That I Saw in 2007. (Runner-up: Children of Men.) I visited Milkyway while the film was being shot, and I hope to blog about the result in a future entry.

At Large on the Internets

On this very site, I’ve posted a new essay on action movies.

Annie Frisbie interviewed me for the Zoom-In podcast here. Annie is also blogging/reviewing Sundance films here.

Fox Independent visited Madison and posted videos on its site. The setup and the interview with filmmaker and teacher Erik Gunneson are here. An interview with me is here.

Shot-consciousness

Most professional critics seem uninterested in the film shot as a shot. They might notice when the images call flagrant attention to themselves, as in Zhang Yimou’s recent films, or in those protracted walk-and-talk Steadicam takes. On the whole, though, reviewers prefer to talk about plot and acting.

Granted, it’s hard to be aware of shots, especially if you get engrossed in the story. But if we want to be fully alert to how movies work on us, we should keep our eyes open. Back in 1968, I read The Moving Image by Robert Gessner, one of the first teachers of cinema studies in the US. There Gessner offered a sturdy piece of advice: Be shot-conscious.

About twenty years later, trying to be shot-conscious and all, I started to notice a certain type of image becoming more common, especially in European and Asian films. Then it started to appear in US films as well, especially indie items. Now it’s very common everywhere, though it’s still not the predominant sort of shot.

Here’s a fairly early example, from R. W. Fassbinder’s Katzelmacher (1969).

How to characterize it? The camera stands perpendicular to a rear surface, usually a wall. The characters are strung across the frame like clothes on a line. Sometimes they’re facing us, so the image looks like people in a police lineup. Sometimes the figures are in profile, usually for the sake of conversation, but just as often they talk while facing front.

Sometimes the shots are taken from fairly close, at other times the characters are dwarfed by the surroundings. In either case, this sort of framing avoids lining them up along receding diagonals. When there is a vanishing point, it tends to be in the center. If the characters are set up in depth, they tend to occupy parallel rows.

Linda Linda Linda (2005)

No one to my knowledge had noticed this sort of shot, let alone named it. I started to call it mug-shot framing, but I found that art historian Heinrich Wölfflin had called it planar or planimetric composition. I went with “planimetric” because that term suggests the rectangular geometry so often seen in these shots.

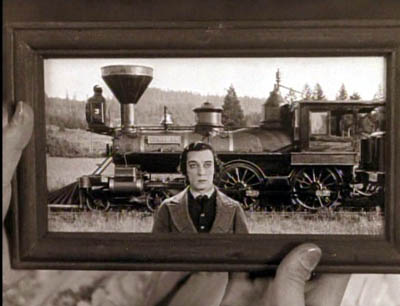

What’s striking is that such imagery is quite rare before, say, 1960. We can find some examples, principally in silent comedy and especially the films of Buster Keaton (himself a pretty geometrical director). But in the 1960s, we find Antonioni and Godard using planimetric shots fairly often.

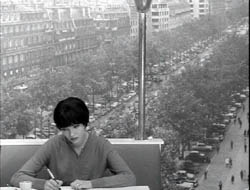

Vivre sa vie (1962)

This image design became more popular from the 1970s onward. Why? In On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light, I tried to trace out some sources and functions of it. Briefly, I think that the planimetric shot emerged from filmmakers’ growing reliance on long lenses, which tend to create a flatter-looking, more cardboardy space than wide-angle lenses do. A telephoto shot makes an image seem less voluminous. It seems to be made of slices of space lined up one behind another.

Filmmakers began using long lenses for many purposes, often because of the demands of filming on location. And some directors realized that long-lens optics offered fresh resources for staging and composition.

For instance, the planimetric scheme is well-suited to a “painterly” or strongly pictorial approach to cinema. In Figures, I discuss two directors who made planimetric shots central to their style. Hou Hsiao-hsien saw very deeply into the possibilities of these shots; I think he learned it from his early skill at shooting on the street with long lenses. You can find more about that here. By contrast, Angelopoulos used the planimetric image in conjunction with architecture and landscape to create a sort of de-dramatized spectacle, a spare grandeur reminiscent of icon painting.

The Suspended Step of the Stork (1991)

The functions of the planimetric image can vary a lot. Often it’s used to suggest stasis and passivity, as in the Katzelmacher instance. Kitano Takeshi picks up on this sense of torpor in certain shots of Sonatine, which suggests that being a gangster means having a lot of time to kill just hanging out.

Kitano’s use of the image also suggests a kind of childish simplicity or naïve cinema. Unlike Hou and Angelopoulos, Kitano uses the planimetric schema as if it were just the most basic way to film anything. Line up your characters and shoot ’em, as if they were figures in South Park or Cathy.

Kitano has compared himself to the kamishibai man, the street performer who narrates stories for children by flipping through illustrated cards, and Kitano’s paintings are more sophisticated, often planimetric versions of those drawings.

The planimetric schema can suggest something more oppressive too. That’s one purpose, I think, of certain shots in Terence Davies’ remarkable Distant Voices, Still Lives. The film’s stylistic system is quite rigorous in its use of straight-on compositions, and it’s worth more attention than I can give it here. For now I’ll just mention that the first part presents tableaux of unhappiness that suggest bleak family portraits.

Here and more generally, the planimetric image often carries the connotations of a posed photograph. Possibly the dry, rectilinear imagery of Walker Evans and the wide-eyed attitudes of Diane Arbus’s portraits have contributed to the sense of stiff ceremony such shots sometimes have.

Walker Evans, Roadside Stand Near Birmingham (1936)

Asian filmmakers combined the planimetric image with very long takes. In Kore-eda Hirokazu’s Maborosi, Yumiko’s husband comes home drunk, a slip from his usual reliable habits. She has just been remembering her previous husband, dead in a bike accident. The rocklike stability of the shot, aided by the grid backing the characters, throws every gesture into relief, particularly when Yumiko’s face lifts slightly into and out of shadow in the course of the action.

In the 1990s US indie filmmakers adapted this staging strategy. In Safe, Todd Haynes uses it to suggest the hard-edged sterility of the wife’s suburban life, which surrounds her with cubical furniture.

Wes Anderson used the image schema occasionally in Bottle Rocket but came to rely on it more and more. (He tended to use wide-angle rather than longer lenses, though; note the bulging effect in the Life Aquatic shot below.)

For Anderson, as for Keaton and Kitano, the static, geometrical frame can evoke a deadpan comic quality. This comes out as well in Jared Hess’s Napoleon Dynamite.

Initially, this scheme also helped filmmakers distinguish their work from Hollywood. Mainstream American films tend to film players in 3/4 views, except for certain situations, such as a theatrical performance or a scene showing a mammoth image display.

V for Vendetta (2005)

Some American directors seem to have used the planimetric shot decoratively, as a nifty one-off touch, as here in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang.

Many overseas directors who rely on this schema adjust their cutting accordingly. In Figures I called it compass-point editing. The usual tactic is to follow one planimetric shot with a reverse shot that’s also planimetric. In the first four shots of Kitano’s A Scene at the Sea, the camera angle switches either 180 degrees or zero degrees.

When I asked Kitano why he cut this way, he gestured toward me, then at himself. “When we are speaking, this is the way we look toward each other. It’s the most natural way to show a conversation.” Apparently this is why over-the-shoulder shots are pretty rare in Kitano’s films.

Planimetric shot/ reverse shot is seldom used in Hollywood films, and it seems to be reserved for certain confrontational situations, or institutional scenes (e.g., doctor/ patient conversations). It can sometimes suggest an unnerving or unnatural encounter, as in I, Robot. The detective Spooner is calling on his old friend Dr. Lanning, and their dialogue is shot in to-camera medium-shots.

At the climax of the conversation, the camera takes up a 3/4 position and arcs around Lanning, revealing him to be only a hologram, presenting his dying message to Spooner. The planimetric image is motivated as suitable for a flat, virtual presence.

Proyas has cleverly prepared us for this subterfuge by ending the previous scene with an unremarkable planimetric framing on Spooner as elevator doors close on him.

This shot leads directly to the initial shot of Dr. Lanning above, apparently addressing us, in a sort of shot/ reverse shot cut across two scenes.

As we might expect, Godard, who helped disseminate the schema, is all up for upsetting it, in Vivre sa vie and Made in USA. The first shot below teases us to read the flat background as a high-angle vista; the second carries the idea of a conversation in a planimetric frame to a beautiful absurdity.

My quick survey doesn’t exhaust the various forms and uses of this strategy. I just wanted to show how shot-consciousness can lead us to notice when filmmakers take up new pictorial tools and modify them for particular purposes.

An appetite for artifice

Offscreen (Christoffer Boe)

DB here (no, not above):

Catching up with several of the fall’s films, I was struck by how often they played quite self-consciously with the overall shape of their plots. Here are some examples.

Network narratives. This is the label I applied in The Way Hollywood Tells It to those films highlighting several protagonists inhabiting distinct, but intermingling, story lines. In Poetics of Cinema, I have an essay examining the conventions of this format. Several films I saw this fall continued this tradition.

*Bobby used the familiar device of gathering everyone in a single spot–a hotel–within a short time frame and interweaving personal stories with a fateful climax. I thought the film was fairly clumsy, but I was still moved. In 1964 I filmed RFK when he stumped our town for the presidential nomination, and in college, though leaning toward Gene McCarthy I thought Bobby was the only candidate who could beat the Republicans. “Dump the Hump!” (Hubert Humphrey) was the rallying cry.) His assassination, during the same year Martin Luther King was killed, was very traumatic to young idealists. Estevez’s film becomes most powerful, I think, by simply replaying footage and speeches, reminding us that there was once a rich politician who talked incessantly about helping the poor. Just as Stone’s JFK positioned Jack as the man who could have averted the Vietnam War, Bobby makes RFK the anti-Bush.

*Fast Food Nation was for me a more satisfying use of the network narrative format. Here the time scheme is more diffuse because Linklater is tracing a large-scale process, the burger from the hoof to the Happy Meal. By starting with the middle-management character (Greg Kinnear) and then easing us into the harsh working life facing Mexican illegals, the film builds sympathy for the immigrants. Gradually, the illegals’ stories take over, and the social conscience of one of the burger chain’s teenage workers is ignited.

The plotting makes some thoughtful moves. A more literal approach would have shown us the meat-processing plant’s killing floor early, as part of the step-by-step process. But here the shocking material isn’t presented until the very climax of the film, as the fate to which the immigrant working woman must submit. Likewise, the film drops the Kinnear character about halfway through, a ploy that conceals from us how he’ll act on his new knowledge. Will he blow the whistle on the plant, and endanger his job? A European film might have left his whole line of action open, but Linklater adheres to the tendency of American films to resolve a plotline one way or another. He does it, however, in an epilogue which leaves us with a sharpened sense of the acute problems of the system.

*The Uchoten Hotel (aka Suite Dreams, Japan, 2006). In the vein of Tampopo and Shall We Dance?, Mitani Koki offers gentle humor mixed with satiric social observation. Confusion reigns at the Avanti Hotel on New Year’s Eve, as a philandering professor, a corrupt Senator, low-end showbiz types, and the hotel staff become embroiled in one another’s lives. Lively long takes display subtle staging, and there’s a ventriloquist’s duck. A tribute to Grand Hotel, Billy Wilder, and Jacques Tati, this good-hearted survey of human aspirations was the most uncynical movie I saw all year.

Many critics seem to feel that the network format is tired out. At indieWire, Nick Schager calls for “a moratorium on second-rate Nashville-style ensemble pieces that seem increasingly to be the province of every Tom, Dick, and Emilio.” The key words are “second-rate”: Like any storytelling pattern, the network option can be used well or badly. Linklater and Mitani use it with flair.

The point I’d stress is that although the network model can claim to be a realistic device (in our world, our projects commingle), it’s almost always presented through a series of conventions–traffic accidents, people brushing past each other, narration that holds back information about the characters’ relationships, and so on. We recognize these as part of the artifice in this tradition of storytelling.

Broken Timelines. During his DVD commentary for Basic, John McTiernan uses this phrase to explain the film’s flashbacks and replays. In the terms we use in Film Art, the linear story action is scrambled or rearranged in the plot that that the film presents to us.

Screenwriters used to urge novices to avoid breaking up the timeline, but in the 1940s through the mid-1950s, films began to play around with story order. Citizen Kane (1941) probably encouraged the flashback form, as did film noir’s emphasis on mystery and crime detection. Siodmak’s fine The Killers offers a prototype. (I discuss its plot maneuvers in Narration in the Fiction Film.)

We don’t lack for flashbacks in contemporary films, but things are getting complicated. Today a film may open with a quite mystifying sequence, before backtracking to acquaint us with the situation. In itself, this isn’t very unusual, since flashback-based films have often opened at a point of crisis and then taken us back to the beginning of the action. The Big Clock and Written on the Wind are instances. The new wrinkle is to actually replay the opening situation or just the images from it in a new context.

*The Fountain by Darren Aronofsky offers one example. Using three time layers, it can keep replaying the opening portions in ways that recontextualize the material we saw at first. In its out-of-this-world realm, as well as its suggestion that the story is in some sense being written as we see it, it reminded me of Slaughterhouse-Five (1972)–another indication that these innovations aren’t brand new.

*Another instance: The opening image of Christoffer Boe’s Offscreen (2006), with a bloody Nicolas Bro in close-up advancing to the camera, gets explained only at the grisly climax.

*The recontextualizing replay isn’t an avant-garde device. Tony Scott’s well-done thriller Déjà Vu uses it in the context of a time-travel plot. It replays the opening sequence in a way that suggests both a branching or alternative future and a deeper understanding of what we saw initially. A similar pattern is found in Flags of Our Fathers, in which we reinterpret the opening differently now that we know the characters more fully. I suppose that Pulp Fiction‘s opening became a powerful influence on this formal choice.

When an action is replayed, it can be shown from different characters’ perspectives. Again, this was explored a lot in the 1940s, as in Mildred Pierce (a replay of the opening) and Crossfire (a replay of the crucial incident). The device is on display in The Killing and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance as well. Kurosawa’s Rashomon made the technique more ambiguous, by not confirming which version of events is accurate. The same idea guides the money exchange in Tarantino’s Jackie Brown, which we discuss in the new edition of Film Art.

*The broken timeline of Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada uses multiple points of attachment mildly, in the murder scene. The replays are more significant and fragmentary in The Prestige. More films in this vein are in preparation, including Vantage Point, which shows an assassination attempt on a US president as seen from five characters’ points of view, “unfolding in 15-minute increments.”

Companion films. Back in the 1960s, Fox announced that it wanted to make Tora! Tora! Tora! with two directors, one Japanese and one American. My friends and I indulged in a game: Whom should they pick? (I favored Ozu and Samuel Fuller.) As you probably know, Kurosawa’s collaboration came to naught (though he did shoot some footage, discussed by Richard Fleischer in his book and his DVD commentary on the film). Fukasaku Kinji and evidently some other directors contributed to the Japan-based footage.

Now, instead of one film with two directors, Clint Eastwood gave us two complementary films from a single hand. I haven’t yet seen Letters from Iwo Jima, but the very idea of showing the same battle from opposite sides in two movies acknowledges a level of artifice.

The French got here first, I think. Marguerite Duras made a companion film to her mesmerizing India Song (on right) called Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta desert. Son nom had exactly the same soundtrack as India Song but a wholly different image track–only landscapes around the site of action, empty (as I recall) of all human presence. A comparable instance is the alternate-worlds pairing by Alain Resnais, Smoking/ No Smoking, adapted from a cylce of Alan Ayckbourn plays.

The French got here first, I think. Marguerite Duras made a companion film to her mesmerizing India Song (on right) called Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta desert. Son nom had exactly the same soundtrack as India Song but a wholly different image track–only landscapes around the site of action, empty (as I recall) of all human presence. A comparable instance is the alternate-worlds pairing by Alain Resnais, Smoking/ No Smoking, adapted from a cylce of Alan Ayckbourn plays.

The companion-film concept seems to be expanding. Red Road, directed by Andrea Arnold, is launching a series of films to based in Scotland and all featuring the same group of characters, but filmed by different directors. The characters are conceived by filmmakers Lone Scherfig (Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself) and Anders Thomas Jensen (Brothers). In a way, a sort of episodic-television idea applied to feature films.

What’s behind this? Why are today’s movies using such self-conscious artifice in their plotting? Is form the new content, the way gray is the new black?

Complex storytelling can be found in a lot of other media today. It’s common to point to Hill Street Blues and later TV shows as reinforcing tendencies toward network narratives in film. Jason Mittell discusses the tendency in Velvet Light Trap no. 58. His article “Narrative Complexity in Contemporary American Television” (available here), makes the case that shows like 24, Arrested Development, Buffy, Malcolm in the Middle, and so on have offered viewers ways “to be actively engaged in the story and successfully surprised through the storytelling’s manipulations”–a good way to describe some of the strategies I’ve been sketching.

In graphic novels and comic art we’re seeing the same tendencies. Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware manipulate time and space in virtuoso ways, as does the highly formalized movement known as OuBaPo. You can check out an American version of OuBaPo in Matt Madden’s 99 Ways to Tell a Story.

In graphic novels and comic art we’re seeing the same tendencies. Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware manipulate time and space in virtuoso ways, as does the highly formalized movement known as OuBaPo. You can check out an American version of OuBaPo in Matt Madden’s 99 Ways to Tell a Story.

In Everything Bad Is Good for You, Steven Johnson argues that people are just getting smarter, and so popular culture is pitched at a more sophisticated level. But quite complex artifice can be found in mass media of earlier eras. As I mention in The Way, we can find backward-told stories in popular fiction long before Memento, and Grand Hotel is an early prototype of the network narrative. Our ancestors weren’t necessarily dumber than we are, and popular art has long harbored experimental impulses.

I’d hypothesize some other causes. Regardless of IQ, more members of the audience have been to college today than in early eras. More of the creators have studied modern art and literature and are ready to borrow experimental devices they’ve encountered in other media. This process has a familiar ring. American filmmaking has often renewed itself by absorbing all manner of experiment, from German Expressionism (for 1930s horror films) to serial music (for 1950s psychological dramas). Usually, I feel compelled to add, the experimental devices are absorbed into existing forms, like classical script structure, genres, or stylistic principles.

I suspect as well that the new genre hierarchy that emerged in the last couple of decades cranked up the artifice level. The rise of science fiction, mystery, fantasy, horror, and comic-book movies probably encouraged clever juggling with story order, point of view, and states of knowledge. So did the rise of indie cinema, which needs narrative innovation to set itself apart from the mainstream. Again, Pulp Fiction fuses the two strands: an indie neo-noir that attracted attention through its bold manipulation of story/ plot relations.

At the same time, filmmakers in other countries have been eager to push the boundaries. Many of the broken-timeline devices have their sources in art cinema of the 1950s and 1960s. Younger European directors like Boe and Tom Tykwer (Run Lola Run) have revived this adventurous attitude toward storytelling, putting them somewhat in sync with American directors. Asian experimentalists like Wong Kar-wai and Hou Hsiao-hsien continue to exercise a comparable influence.

We need to think more about where this impulse toward innovation comes from and how it shows itself, but it seems likely that the flourishing trade in self-conscious storytelling will be with us for some time yet. Hollywood cinema has long been self-consciously, almost fussily formal, and it has a vast appetite for artifice.

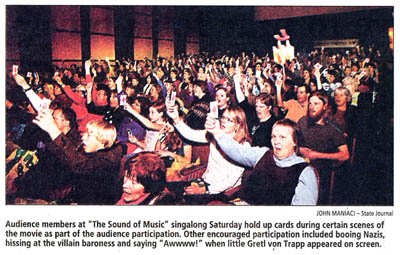

Mad City’s movie mania

The Hilldale Theatre of Madison, Wisconsin opened its doors in spring of 1966 roadshowing The Sound of Music, and last weekend the theatre closed. To celebrate its passing, the management held a Sound of Music Sing Along, complete with subtitles to help with the lyrics. (No, not “How do you hold a moonbeam in your hand?” but the really tough ones.)

People came dressed as Maria, nuns, and the frog that was slipped into Maria’s pocket. There were cues for audience interaction, including saying “Awwww!” when Gretl appears on screen. This brought back memories of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, which ran at midnight shows at the now departed Majestic Theatre from 1976 through the mid-1990s. For a report on that, and the connubial bliss it brought, have a look here.

Kristin and I came to Madison in fall of 1973, prime time. The campus boasted 22 film societies: Wisconsin Film Society, Fertile Valley, Green Lantern, Hal-9000, and all the rest. Members of the Union Film Committee, overseeing the only campus 35mm venue, were passionately debating whether to show Godard, or Jancso, or a John Ford retrospective. I convinced them to show The Young Girls of Rochefort, which hurt my reputation,and Play Time, which I think helped it.

The Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research had just acquired several thousand Warners and RKO films. The Majestic Theatre ran double and triple bills (kung-fu, Leone’s Dollars trilogy). The Velvet Light Trap magazine was going strong, run wholly by students and semi-students.

In those days, before home video, it was glorious to be in Mad City. We had 6-10 movies to see every night, apart from course screenings. We didn’t even own a TV. Who needed one?

Not to mention the cast of characters, all colorful. In the late 1960s-early 1970s the film community included:

Not to mention the cast of characters, all colorful. In the late 1960s-early 1970s the film community included:

The late Mark Bergman, premiere projectionist, fan of Phil Karlson, and gentle soul.

Joe McBride, critic (Variety), screenwriter (Rock and Roll High School), actor (The Other Side of the Wind), and excellent biographer (Spielberg, Capra, Ford, now Welles; What Ever Happened to OW? is very engaging).

Mike Wilmington, one of America’s top film critics, a mainstay of the Chicago Tribune.

Tim Onosko, author of Wasn’t the Future Wonderful?, industry consultant, and documentary filmmaker.

Gerry Peary, enterprising critic, screenwriter, and film professor.

Danny Peary, most famous for his series of Cult Movies books.

John Davis, co-founder of the Light Trap and creator of Capital City Comics.

Susan Dalton, another co-founder of the Light Trap and archivist at the American Film Institute.

Pat McGilligan, prolific critic, interviewer, and biographer.

Tom Flinn, the other co-founder of the Light Trap, pop-culture encyclopedist, and expert on Germans in Hollywood.

Bill Banning, founder of Roxie Releasing and operator of San Francisco’s Roxie Cinema.

Reid Rosefelt, publicist, producer’s rep, and filmmaker.

Many of these worthies ran film societies, so their ideas and passions showed through the films they screened. For more on the Madison Movie Mafia, go here.

Also present and active in late 1960s-early 1970s:

Filmmakers Erroll Morris, Stewart Gordon, Jim Benning, Bette Gordon, Michelle Citron, Karyn Kay.

Scholars-in-training James Naremore, Doug Gomery, Maureen Turim, Fina Bathrick, Marilyn Campbell, Diane Waldman, Ed Branigan, Vance Kepley, Peter Lehman, Brian Rose, Peter Brunette, Frank Scheide, and many more.

Great days, and nights…Mike Wilmington has written a fond appreciation of the whole scene here.

But this isn’t just an exercise in baby-boomer nostalgia. The Madison Cinema Juggernaut rolls on. The Light Trap just published its 58th issue. The Onion, founded by Madison students, continues to be America’s finest news source. Dan Fuller makes silent films with his students, using cameras from the 1920s, and the results have played at Pordenone. And not least, the Cinematheque, founded by faculty and students in the Communication Arts Department, carries on the spirit of the old film societies.

In sync with the closing of Hilldale, our Cinematheque ended the semester last weekend. (Crowd starting to gather above.) An outstanding schedule (S. Ray, Tarr, Godard, Sjostrom.) wound up with Lau Kar-leung’s Dirty Ho, the last of our string of Shaw Brothers classics. It was, of course, a delight, full of flamboyant, good-humored, and downright weird kung-fu.

A lot of it was close-quarter work, as warriors examining pottery or sampling wine disguise their deadly thrusts as elaborate courtesy. Lau is arguably Hong Kong’s top martial arts choreographer, but he’s a fine moviemaker as well, and Dirty Ho is one of his best. Even the shabby state of the print, an original from 1979 complete with curious purple splotches, seemed to pay tribute to three decades of campus film fanaticism. It could have played the Majestic.

Even with the loss of the two Hilldale screens, Madison has five commercial screens dedicated to foreign and independent films, not counting the Cinematheque and the Play Circle in the Student Union. Come spring with Sundance, we’ll get six more. And our Wisconsin Film Festival (April 12-15) comes hard on the heels of the Sundance complex. Wisconsin Movie Madness lives on.

DB

PS: Thanks to Ivo Blom for the Swarte illustration up top.

PPS 21 December: Today’s Isthmus has a nice story on Dan Fuller and the Wisconsin Bioscope company. I played a small role in their last film of the semester, and despite the need to wear eye shadow, this gave me an even greater appreciation of their efforts. They’ll have a screening of recent work some time next term.