Archive for the 'Asian cinema' Category

Spring songs

DB here, still in HK:

One director is about as conservative, artistically speaking, as you can get. The other is the long-established wild man of Hong Kong cinema. Both are showcased in retrospectives at this year’s Hong Kong International Film Festival. In a later post, I’ll talk about the outlier; today it’s the Organization Man.

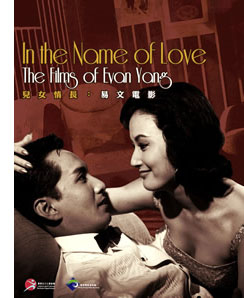

The Hong Kong Film Archive is running a series of works of Evan Yang (Yang Yi Wen). He wrote novels, scripts, song lyrics, and passionate letters to his wife and mistresses, but he’s mostly remembered as a director. Laboring for M. P. & G. I., the Hong Kong studio owned by the Cathay company, Yang established his reputation as a reliable craftsman.

Yang is best remembered for a string of 1950s Mandarin-language movies set in modern Hong Kong; many sequences offer a virtual travelogue of the energetic, sun-drenched colony. Probably Yang’s most famous film is Mambo Girl (1957), starring the effervescent Grace Chang Ge Lan, but local audiences have a fierce sentimental attachment to his two-part historical romance Sun, Moon, and Star (1961). I’ve seen some of these in other thematic retrospectives, but this series is quite thorough. It includes films Yang wrote as well as ones he directed, and it will run through mid-May.

Yang is best remembered for a string of 1950s Mandarin-language movies set in modern Hong Kong; many sequences offer a virtual travelogue of the energetic, sun-drenched colony. Probably Yang’s most famous film is Mambo Girl (1957), starring the effervescent Grace Chang Ge Lan, but local audiences have a fierce sentimental attachment to his two-part historical romance Sun, Moon, and Star (1961). I’ve seen some of these in other thematic retrospectives, but this series is quite thorough. It includes films Yang wrote as well as ones he directed, and it will run through mid-May.

It’s hard to disagree with the severity of the program notes. “His films often suffer from loose structure and sloppy direction. . . Always professional but never a perfectionist. . . . Evan Yang is not a master, nor is he a great film artist. . . .” The impression, not wrongheaded, is of a Hong Kong Charles Walters. But Yang worked hard. In the Archive’s exhibition of his personal papers, you can see his tidy, artisanal dedication. The script pages on display include elaborate notations of shots (ls, cu, diss to…) and markings for repeated setups. It’s evident that Yang took pains to create his smooth, barely noticeable style.

His effort shows on screen. His staging is clean and functional, though he is probably too fond of lining people up in rows. There’s seldom a self-consciously flashy shot or unstable composition. The emphasis is always on straightforward rendering of the melodramatic situations that drive his plots. A doctor falls in love with a patient who’s married (A Little Girl Named Cabbage, 1955). A clerk’s daughter is beautiful but mute, and the family needs money for her operation (The Beauty and the Dumb, 1954). A cat burglar trying to go straight runs afoul of his mercenary wife, who abandons their daughter and then returns to blackmail the family raising her (Blood Will Tell, 1954). Despite the all the adversity, however, things usually turn out well. In Madame Butterfly (1955), Yang updates the opera, making Pinkerton a Hong Kong businessman, and the string of pathetic coincidences swerves into a happy ending.

His effort shows on screen. His staging is clean and functional, though he is probably too fond of lining people up in rows. There’s seldom a self-consciously flashy shot or unstable composition. The emphasis is always on straightforward rendering of the melodramatic situations that drive his plots. A doctor falls in love with a patient who’s married (A Little Girl Named Cabbage, 1955). A clerk’s daughter is beautiful but mute, and the family needs money for her operation (The Beauty and the Dumb, 1954). A cat burglar trying to go straight runs afoul of his mercenary wife, who abandons their daughter and then returns to blackmail the family raising her (Blood Will Tell, 1954). Despite the all the adversity, however, things usually turn out well. In Madame Butterfly (1955), Yang updates the opera, making Pinkerton a Hong Kong businessman, and the string of pathetic coincidences swerves into a happy ending.

The musicals and comedies, although more light-hearted, still bear streaks of melodrama. What I had remembered about Mambo Girl is its fascination with that dance craze, but the plot actually has a serious basis: Grace learns that she’s adopted and sets out to find her birth mother, who turns out to be a nightclub singer. The breezier college romance Spring Song (1959) takes itself not at all seriously, but there is a persistent class antagonism between Grace and her rich rival.

Stylistically, Spring Song shows us Yang in a playful mood. There’s a visual gag during a scene in a coffee shop when our two male leads, Peter Chen Ho and Roy Chiao, wait for their girlfriends. Yang makes them mirror images, even timing the waiters’ arrival to create a funny framing.

Of course when the women arrive and see each other, comic misunderstandings ensue, also played out symmetrically.

Somewhat more subtly, Yang stages the opposition between Grace and Jeanette Lin Tsui during a meeting of classmates by putting the antagonists at extreme ends of a crowded frame.

The archive has produced a handsome book of Yang’s memoirs, in Chinese only, as well as an informative bilingual pamphlet on the retrospective. I hope to sample other items in the series before I leave next week; you know I won’t miss Yang’s take on spaghetti Westerns, Magnificent Gunfighter (1970).

Even if he weren’t such a solid craftsman, I’d respect his films’ sheer documentary value. When Hong Kong movies of the 1950s venture outside their rather creaky interior sets, they often yield up radiant images of a city on the rise. The scene in The Beauty and the Dumb showing Peter Chen Ho crossing the harbor, sitting happily in his sportscar on the Star Ferry, is enough to brighten your evening.

Spring Song, Mambo Girl, Sun, Moon, and Star, and other Yang films are available on DVD and VCD in English-subtitled, not-so-great transfers from Cathay.

Mambo Girl.

A masterpiece, and others not to be neglected

About Elly.

DB still in Hong Kong:

I haven’t been slack, honest; I’ve caught several items at the archive and during the first weekend of the Film Festival. I even saw Watchmen, accompanied by rump-shaking Shaw Active Sound. But today let me get caught up with some films I saw in Filmart last week.

I was unimpressed by the picture that launched Filmart, Derek Yee’s Shinjuku Incident. Billed as Jackie Chan’s emergence as a real actor, it features him as a confused illegal immigrant thrown into the Tokyo underworld. His character never made sense to me, and the direction was formulaic: basically pan around a group of actors until somebody says something. Daniel Wu gets to play another maniac.

Less heralded Filmart screenings were much more satisfying. The best, and my favorite film I’ve seen so far this year, was About Elly. It is directed by Asghar Farhadi, and it won the Silver Bear at Berlin. I can’t say much about it without giving a lot away; like many Iranian films, it relies heavily on suspense. That suspense is at once situational (what has happened to this character?) and psychological (what are characters withholding from each other?). Starting somewhat in the key of Eric Rohmer, it moves toward something more anguished, even a little sinister in a Patricia Highsmith vein.

Gripping as sheer storytelling, the plot smoothly raises some unusual moral questions. It touches on masculine honor, on the way a thoughtless laugh can wound someone’s feelings, on the extent to which we try to take charge of others’ fates. I can’t recall another film that so deeply examines the risks of telling lies to spare someone grief. But no more talk: The less you know in advance, the better. About Elly deserves worldwide distribution pronto.

Also worth seeing was A Place of One’s Own, a Taiwanese film that uses imagery of living spaces to explore generational differences. As a young rock singer’s career fades, his pop-star girlfriend’s career takes off. Their fates are intertwined with those of a family who live near a cemetery. The father makes exquisite paper dwellings that are burned during funeral ceremonies, the mother maintains gravesites (and talks to ghosts), while the son launches himself on a real-estate career with the help of a dodgy rich kid. Director Ian Lou (God Man Dog) enhances this network narrative with some clever flashback constructions as well.

My Dear Enemy.

Two films I saw in the market display different ways of using past incidents to explain a story’s present-time crises.

My Dear Enemy, by Lee Yoon-ki, exhibits a striking concentration and dramatic focus. Hee-soo’s boyfriend Cho borrowed $3500 from her before they broke up. Today she has tracked him down and demands it back. She drives him around as he visits various associates—his biker cousin, a high-class prostitute, a rich older woman who seems to be using his sexual services, an unmarried mother—scrounging for money to pay Hee-soo back. Across a day of setbacks both comic and frustrating, we come to learn of their romance and their deeper personalities.

At first Cho seems the classic annoying charming rogue, chattering about the music he likes, pausing to buy flowers and oversweet coffee, flattering every woman he meets, and on the verge of ducking Hee-soo’s demands. Every time he gets out of the car, you think he might bolt. These first impressions, however, get nuanced as we see how he moves easily and even gracefully through his milieu. He seems a loser, but we learn that he is resilient and resourceful. Meanwhile Hee-soo’s righteous determination to get her money back comes to seem something of a desperate effort to close the book on painful episodes from her past.

Lee Yon-ki, who earlier gave us This Charming Girl, is very good at structuring scenes so that we understand every character’s changing attitudes. To get the money, Cho lets his target think that he’s helping out Hee-soo, and at one point he implies that she’s pregnant. As Hee-soo realizes that he’s making her play a part in his drama of self-aggrandizement, she is hurt and ashamed. And Cho’s happy-go-lucky facility in his milieu makes her feel more of an outsider. One scene, in which Cho’s hooker friend calmly insults Hee-soo, is a subtle study in casual humiliation.

Yet Hee-soo’s tenacity wins Cho’s respect. At the same time, while as the day passes into night, Cho emerges as a figure with his own code of honor (he eventually provides a meticulous account of what he’s cost her in the day’s expenses) and even a dream of success that might, the last shot suggests, be fulfilled. Bits of business around coffee, cellphones, flowers, and a broken windshield wiper chart the fluctuations in their relationship concisely. My Dear Enemy is a model of how to make a tight, intimate movie focused on simple incidents that carry almost Hitchcockian tension: Will Cho pay Hee-soo off? Will he slip away and abandon her again? What will we learn next about each one’s past? Like About Elly, this is a character study with an engrossing plot.

More diffuse, I thought, was Ann Hui’s unfortunately titled Night and Fog. It’s a companion piece to The Way We Are, her 2008 study of life in the Tin Shui Wai area of Hong Kong. I offered an admiring account here.

This is the “darker story” Ann promised us at last year’s festival, and it’s based on an actual case. Lee Sum has married a Mainland woman, Ling, and has fathered two daughters with her. He’s on social security and Ling works as a waitress. But Lee is considerably older, and he suspects her of flirting with other men. He becomes insanely jealous, beating her and throwing her and their daughters out. Ling finds happiness in a woman’s shelter, but social services fail her and Lee brutally murders her and the children.

No harm in telling you the ending because the murder is the first thing we see. The film consists of a series of flashbacks, some nested within others, that trace what led up to Lee’s horrendous crime.The plot is presented in the framework of a police investigation, with witnesses to Ling’s life answering questions that pass into scenes from the past. The early flashbacks are quite linear, treating the buildup to Ling’s stay in the shelter and a moment in which she sings a song about a mushroom maiden. Then we plunge further into the past, showing her leaving her provincial home as an adolescent on the way to work in the city. Soon we’re given early moments in Lee’s courtship of her.

One effect of introducing the early stages of their marriage late is to mitigate the harsh portrayal of Lee that has dominated the first half of the film. He seems genuinely in love with Ling, and he rebuilds her parents’ home. Already, however, we glimpse his drunkenness, his sadism, and his aggressive sexual appetites.

On the whole, I’m not sure that this complicated flashback structure serves the film well. At times it is strikingly symmetrical, as when a scene of Lee returning from Shenzhen on the train is followed by a distant flashback of the marriage, and this is closed off by a shot of Ling and her daughters traveling on the same train. At other points, though, the relation between the witness’s testimony and the flashback episodes is arbitrary, with the flashbacks showing scenes unrelated to that witness’s knowledge of the family drama.

It seems to me as well that the power of the events leading up to Lee’s murder of his family is vitiated by the protracted Mainland visits, widening the film’s field of view to life in Sichuan and Ling’s family. Where My Dear Enemy lets its backstory emerge in piecemeal fashion through hinting dialogue, dramatizing every relevant moment in Ling’s past seems to lose some focus.

Likewise, there’s a certain fuzziness about the film’s main thrust. Is it a character study, trying to explain why Lee is violently jealous and why Ling stays with him? The only clear answer I could determine was her sense of indebtedness for his help to her parents. Is Night and Fog then best taken as a critique of the Hong Kong bureaucracy? The social workers are portrayed as indifferent or unable to understand domestic violence. But in that case we need to see more of the mechanisms of decision-making than we do, and then many of the intimate relations of the couple would be extraneous. The battered women’s shelter, while not unblemished, becomes the opposite pole to Ling’s dangerous household, and Huipresents it as a safe space where women can express their feelings spontaneously. But again, this angle on the material seems vitiated by bringing in a public protest against real-estate development of the harbor area—an important issue, but in the context a bit distracting.

The film seems to me to excel in areas that Hong Kong cinema has made its own: extreme emotion and sheer physicality. The violence of Lee’s assaults on his family are terrifying, and Simon Yam’s performance is tremblingly ferocious. Smoking furiously, swigging cans of beer, Yam gives us Lee Sum as a figure on the edge of destruction. He makes even fishing seem an act of aggression. Lee’s incessantly jiggling leg is like the timer on a pressure cooker, and when he sits down with his son from a previous marriage—a sleepy-eyed young pimp—the two of them share the same foot-jiggling tic. In this shot, Hui gives us a diagram of male aggression ready to burst.

If My Dear Enemy trades on suspense, Night and Fog creates dread. One is roundabout, the other more direct; one suggests much, the other shows everything. Two ways, we might say, of making modern cinema.

More, including another Iranian masterpiece, in my next communiqué.

Night and Fog.

Jackhammers, parties, and markets

DB here:

No matter how often you see this Ur-touristic view, it’s still spellbinding. Yes, I’m back at the Fragrant Harbor for the annual festival, front-loaded with Filmart, the film market. My 2008 report starts here, and the 2007 one starts here. Plenty of entries for those years; I’m not sure I’ll be able to roll out so many this time, but we’ll see.

Start with the first impressions. Massive building projects and new traffic-flow strategies have made the tip of the Kowloon peninsula even more pedestrian-unfriendly than last year. Grim underground passages take you in loops away from your destination. No more direct routes anywhere, it seems, and construction projects I’ve watched for years continue to be unfinished. From the twenty-first story of my hotel I can hear a jackhammer at street level.

A striking case: My hotel is rather close to a multiplex in West Kowloon, located in an upscale mall called Elements. (More on Elements in a later communiqué.) But around this trendy spot stretches a vast vacant lot.

Again, there’s a lot of pedestrian control, including barriers to keep you from crossing the street. Still, it’s not hard to find places where enterprising passersby, perhaps armed with blades, have broken on through to the other side.

Moreover, the Star Ferry to Wanchai still offers a pleasantly sustained ride and the usual spectacular views, even in the rain and mist that have enveloped my first days here.

Wanchai is the location of Filmart, set up in the Convention Centre, the mammoth swooping building seen at the top and bottom of this entry. As usual, Filmart was stuffed with seminars, screenings, and dealmaking, as well as the Asian Film Awards.

The opening of Filmart included a party, where you could find Chris Doyle, accompanied by a beer, rubbing shoulders with Stefan Borsos, editor of the German magazine CineAsia.

The party got stranger. This year’s festival logo is a dude in black tie with a black starburst head and a hollow look around the eyes. I thought he was only a graphic design until Karen Mok brought him onstage.

He seems a saucy fellow, at least judging from his hand gesture here.

Filmart opened with a screening of Derek Yee‘s new film Shinjuku Incident. Before the show, Yee, on left, lined up with his cast. You can recognize at least one of the ensemble, grinning as usual.

In the following days, I saw several good movies: More on them in the next post in a day or so. I also attended some sessions devoted to technology and marketing. The effects company Digital Magic sponsored a demonstration of various digital formats, of which the Red system seemed to me the best. Digital Magic also gave out cute Viewmaster-like toys promoting their work.

I learned things from this session and the one sponsored by Salon Films, but the main live event I hit was the Hong Kong Film New Action Forum, a day-long series of sessions about the future of Chinese film. The first item was a brief discussion moderated by director Gordon Chan (Beast Cop, Painted Skin; left). Two experts discussed the current status of CEPA, the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement that allows Hong Kong productions to count as mainland ones for purposes of financing and distribution. Across the last few years, half or more of the top-grossing pictures, such as the Zhang Yimou costume epics and Peter Chan’s Warlords, have been CEPA-enabled coproductions. Other countries, such as Singapore, Japan, and Korea, are investing in such projects.

I learned things from this session and the one sponsored by Salon Films, but the main live event I hit was the Hong Kong Film New Action Forum, a day-long series of sessions about the future of Chinese film. The first item was a brief discussion moderated by director Gordon Chan (Beast Cop, Painted Skin; left). Two experts discussed the current status of CEPA, the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement that allows Hong Kong productions to count as mainland ones for purposes of financing and distribution. Across the last few years, half or more of the top-grossing pictures, such as the Zhang Yimou costume epics and Peter Chan’s Warlords, have been CEPA-enabled coproductions. Other countries, such as Singapore, Japan, and Korea, are investing in such projects.

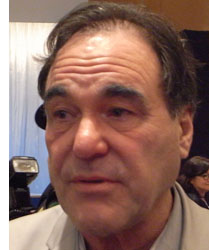

The other session I attended was more high-profile. Philip Chan, screenwriter and former cop, moderated a discussion among John Woo, Oliver Stone, Andrew Lau Wai-keung, and Feng Xiaogang. The Chinese directors talked about the market. Stone talked about creativity. This division of labor reminded me of what Bernard Shaw supposedly told a Hollywood producer: “The problem is that you are only interested in art, and I am only interested in money.”

Woo took the floor with a long discussion of making Red Cliff. He made the usual point about wanting to wed Chinese stories to Hollywood production values. Some other items:

Woo took the floor with a long discussion of making Red Cliff. He made the usual point about wanting to wed Chinese stories to Hollywood production values. Some other items:

*He built the project to have marketing appeal, designed both for Asian and western consumption. For instance, strong women appeal to female viewers in all countries. He claimed that one reason that Red Cliff broke attendance records in Japan was the support of women audiences.

*Woo also wanted to bring audiences in Hong Kong and China back to local films, away from Hollywood imports. Viewers, he claims, are bored with Hollywood’s formulas and want something fresh and authentic. But local audiences are getting tired of Chinese blockbusters too, so in Red Cliff Woo introduced humor along with Hollywood-level production values.

*He suggested that before making Red Cliff he had considered retiring. Now he’s planning more projects.

Lau and Feng likewise took up practical considerations. Lau said that filmmakers must go where the market leads. He suggested there was a period when Hong Kong filmmakers went to Hollywood, but now that route is risky. At the moment, the market is the Mainland, not the West. He was not rueful about his own experience in Hollywood (with The Flock), but he treated it as a chance to learn “a different set of rules. Every place has its own rules.” He also spoke of the unexpected success of Infernal Affairs, a “back-to-the-wall” effort that seemed risky in the market decline of the 2000s. No one expected the film to be so successful; the actors cut their asking prices to be in it.

Feng Xiaogang, Mainland director of Cell Phone and A World without Thieves, lived up to his reputation for stirring things up. Announcing that Hong Kong people “consider the Mainland a four-letter word,” he rattled off an account of the current PRC market. Feng indicated that a $20 million film can presently break even in the domestic market. This prospect interested me, because such benefits are rare in the history of movies. As film students know, the US used its big domestic market as a base to launch vast overseas distribution.

Box-office income is growing fast, but there aren’t enough screens. He claimed that there were about 4000 in the country, an absurdly small number for such a populous country. (Probably this figure counts only modern screens, not old or temporary ones.) The key, Feng suggested, was capitalizing the building of still more screens, especially in the 350 “small” cities. The government will subsidize theatre construction to some extent.

If 1000 more screens are added, Feng speculated that in five years the annual box-office receipts could hit 30 billion RMB. That’s about $4.5 billion, somewhat less than half of the 2007 US box-office take—but twice as much as the income in Japan for the same year. China is developing into a prepossessing market.

Finally, Oliver Stone confessed his love of Asian films, singling out their “iconic imagery” (Crouching Tiger, even Woo’s Face/Off) and lyricism (Ozu, Wong Kar-wai). His advice: Don’t withdraw from engagement with the West and “Make films that pop their eyeballs out.”

Finally, Oliver Stone confessed his love of Asian films, singling out their “iconic imagery” (Crouching Tiger, even Woo’s Face/Off) and lyricism (Ozu, Wong Kar-wai). His advice: Don’t withdraw from engagement with the West and “Make films that pop their eyeballs out.”

One theme I took away was the way in which regionalism continues to rule the Asian industries, a topic I raised in Planet Hong Kong and in late chapters of Film History: An Introduction. Who needs Western markets if the PRC market continues to swell and if other territories in the area hold up their end of financing, distribution, and the occasional regional hit? As far as mass-market cinema is concerned, we may be moving toward a bipolar world, with North America at one pole and Asia at the other. For an excellent, fact-filled analysis of the implications of this trend toward regionalism, see Darrell William Davis and Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh’s brand-new study, East Asian Screen Industries.

Soon, very soon, we go to the movies.

Screen Digest offers some slightly older statistics on the Mainland market here. For more recent information on Chinese exhibition in a worldwide context, see “Exhibition Breaks Revenue Record,” Screen Digest (September 2008), 274. The number of screens cited here is far greater, perhaps because it counts all the rural, unmodernized, or temporary venues. Karen Chu of the Hollywood Reporter sums up the New Action Forum event here.

Hong Kong Convention Centre.

Three from Palm Springs

Four Nights with Anna.

DB here:

Three high points from the Palm Springs International Film Festival. Soon Kristin will offer some entries.

Four Nights with Anna is a GOFAM—a Good Old-Fashioned Art Movie. Set in a muddy Polish town, it follows a loner as he stalks a zaftig nurse. Leon watches her from around corners, studies her through her apartment window, and eventually sneaks sleeping powder into her sugar jar. This puts her out soundly enough to allow him to break into her apartment and watch her at close quarters.

My synopsis, like most retellings of this spare movie, not only spoils the experience but fundamentally changes it. Instead of laying out the premises explicitly, the film’s narration supplies them in tantalizing, equivocal doses. Skolimowski follows the great tradition of distributed exposition, so that we get context only after seeing something that can cut many ways. Early we see Leon buying an axe; soon he fishes a severed hand out of a sack and tosses it into a furnace. Is he a serial killer? No. After a while we learn that he’s the disposal officer for the hospital crematorium. Retrospectively fitting together these data provides a classic art-film pleasure, the equivalent of the curiosity-arousing clue sequences in a mainstream mystery.

The same goes for the ambiguous inserts that suggest a police interrogation. Only halfway through the film do these snippets become lengthy and explicit enough for us to place them in the story’s time sequence. Just as the Nouveau Roman of Robbe-Grillet owed a great deal to the classic detective story, the European art cinema tradition has drawn heavily on the investigation plot, from Les mauvais rencontres (1955) to The Spider’s Stratagem (1970). The premises of the thriller surface as well. The central conceit of Four Nights and of Kim Ki-duk’s 3-Iron, of a stranger who quietly and obsessively prowls around homes, was also explored in Patricia Highsmith’s 1962 novel Cry of the Owl, but not with Skolimowski’s playful indeterminacy about who and what and why.

The trick, then, is in the telling. By accreting details that cohere gradually, Skolimowski’s film not only engages curiosity and suspense, but also allows room for wayward, if dark humor. Leon’s quaking abasement leads to embarrassment, pratfalls, and comically strenuous efforts to melt into his surroundings. Objects take on a precise life, as Leon crushes his grandmother’s sleeping pills to powder and uses plastic silverware to fish a fallen ring from cracks in the floor. We never see Anna apart from Leon; she’s either in the same locale or glimpsed in precisely composed shots of her at her window. The exact, constrained handling of optical point-of-view owes a lot to Rear Window, but Jimmy Stewart never went so far as to install a new window to enhance his peeping.

In its diffuse exposition, its teasing inserts, and its gradually unfolding implications, a GOFAM also asks us to appreciate unresolved uncertainties. During the Q & A, Skolimowski remarked that he liked “to play with a little ambiguity . . . to leave it for the audience to interpret.” The locale? Indefinite, he says. The time period? Deliberately left vague. The mysterious final shot? “A third ambiguity.” For the man who made the kinetic Identification Marks: None (1964), Walkover (1965), Barrier (1966), and Le Départ (1967), film is something of a sporting proposition. It’s good to see him back in the game.

By contrast, The Shaft by Zhang Chi is a NFAAM, a Newfangled Asian Art Movie. That means minimalism. Single-shot scenes are captured by a distant, stable camera. Characters mutely go about their business, or just stand there. Pivotal plot moments take place outside the frame or between two static scenes. Any dramatic climaxes and grand passions are muffled or simply sufffocated.

The proximate sources of this Asian minimalism are probably the late 1980s films of Hou Hsiao-hsien. A European predecessor of the style, I think, is Fassbinder’s Katzelmacher (1969), but its most famous early instance would be Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman (1975).

Such a quiet style poses a problem: How to show plot changes and character development without lengthy dialogue? A common solution is to repeat setups in ways that diagram changes in character relationships. Have a young man pedal his bike up to his girlfriend and offer her a ride. Later as their relationship cools, show him in a similar framing riding callously past her.

Or show the couple wordlessly visiting a lake, but after they break up, show the girl standing there alone.

Tableaus can be used to parallel couples. Each pair meet near the village railroad trestle, but the compositions distinguish the couples.

Likewise, the shots showing the central family eating in front of the TV can be recalled through variation. The number of people at the table and their identities can change over the course of time.

The Shaft puts such conventions to solid use. In a rural Chinese town, young people face the choice of going to work in the mine or moving to Beijing. The film is built out of three stories, centering on a daughter, then her brother, and finally their father. At the end, the eventual revelation of what happened to the family’s mother throws the preceding love stories into sharper relief.

Once the innovators have mastered a style through dint of effort, others can glide down the learning curve and pick it up quickly. But then they should try to add something new. Today the rudiments of the minimalist style are comparatively easy to acquire. To go beyond those, you need something else—a more elaborate play with pictorial variations, or more ingenious staging (the Hou solution), or a gift for adjusting to the contours of landscape (the Jia Zhang-ke alternative). The Shaft is well-carpentered. It is measured and poignant (especially in its final story), and it concludes with a stunning trio of shots. Its very modesty, though, suggests the conventions of NFAAM need some renewal, even some shaking up.

Shaking things up is what Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s Tokyo Sonata is all about. A salaryman is downsized, but he can’t bear to tell his family. He pretends to go off to work while he actually tries to find a new job, any job. In the meantime, his sons display more ambition and courage in their limited worlds, than he does, while the mother tries to defuse the emerging tensions.

For an hour or so, this story is engrossing on naturalistic terms, alternating comedy and pathos. It might continue in a vein of gentle realism characteristic of that perennial Japanese genre, the shomin-geki, ending with everyone’s stoic reconciliation to the vagaries of life. But the director of Cure and Charisma will go along with this formula only up to a point. Why not break the form? You can argue that the simple purity of The Shaft plays too cautiously; once you’ve figured out how things will probably unfold, who cares to see the rest? A smooth cup is lovely, but a cracked one possesses its own enigmatic appeal.

So Kurosawa careens his homely tale into grotesque territory. The tone and plot logic that he’s cultivated so carefully are fractured by some violent emotions, implausible coincidences, and unexpected twists. Granted, his technique remains unruffled.Kurosawa follows Japanese traditions of enclosing faces in apertures and arranging people in gridwork patterns that still leave room for natural movement. The beginning of the story’s wild detour is discreetly signaled by a variant of the film’s first shot. But the composure of the handling makes the challenge to our expectations all the more disruptive.

I shouldn’t say much more, except to note that I meant the word fracture to suggest that the film mends its bones eventually. The final moments are taken up with a delicate performance of Debussy’s Clair de lune. Neither GOFAM nor NFAAM, risk-taking and in the end quite moving, Tokyo Sonata attests to the unpredictable innovativeness of Japanese filmmaking.

I may add other thoughts to Kristin’s upcoming dispatch, but for now I just note that Palm Springs is the only festival I know that uses Béla Tarr soundtrack cuts for pre-show music.

Tokyo Sonata.