Archive for the 'Asian cinema' Category

A glance at blows

DB here:

Perhaps it came from watching the Odessa Steps sequence, projected in hazy 8mm, on the bedroom wall during my teenage years. Or maybe it was seeing my first Bruce Lee movie in the early 1970s. In any case, at some point I became a connoisseur of action sequences. Eventually I was able to indulge this tendency by writing about Eisenstein, but also by studying Asian action film.

I became convinced that martial arts movies from Japan and Hong Kong constituted as important a contribution to film aesthetics as did the Soviet Montage movement. Through shot-by-shot and even frame-by-frame analysis, I tried to show that these movies were exploring ways that cinema could arouse us kinesthetically. Their use of composition, cutting, color, music, and physical motion was not only beautiful but also engaging on levels that we didn’t fully understand. (Perhaps now that we know about mirror neurons we’re in a better position.) Certain turns in the action make us laugh, but not in derision. We laugh in jubilation, and sometimes out of admiration for sheer audacity. At their most ambitious, these films achieved the physical-emotional ecstasy that Eisenstein found in sharply executed “expressive movement.”

A jolting blur

So it was with a definite sadness that I watched, from the 1980s onward, the tendency of American filmmakers to give up on rendering physical movement with full force. Action sequences became jumbled arrays of short shots and bumpy framings. The clarity and grace of motion seen in classic Westerns and comedies, in the work of Keaton and Lloyd and Ford and Don Siegel and Anthony Mann, gave way to spasmodic fights and geographically challenged chases. At first, the chief perpetrators were Roger Spottiswoode and Michael Bay. Now it’s nearly everybody, and journalistic critics have recognized that this lumpy style has become the norm, even in the generally admired Bourne entries.

Classic Hong Kong and Japanese action scenes were “expressionistic” in the sense that their larger-than-life balletics and aerobatics amplified recognizable (if extreme) possibilities of the human body. The result was a carnal cinema, in which shooting and cutting aimed to enlarge and prolong graceful movement. By contrast, Hollywood action scenes became “impressionistic,” rendering a combat or pursuit as a blurred confusion. We got a flurry of cuts calibrated not in relation to each other or to the action, but instead suggesting a vast busyness. Here camerawork and editing didn’t serve the specificity of the action but overwhelmed, even buried it.

Why is the filmmaker reluctant to face the concrete, moment-by-moment facts of the fight? Maybe it’s fear of censorship, or maybe it’s just lack of interest in physical processes. By contrast, most of the great Hong Kong action directors have been themselves martial artists. To them a fight is a suite of tangible actions and micro-actions. Or maybe the new muddier approach seeks to hide the fact that the action is preposterous. Western audiences don’t like far-fetched action that isn’t comic, but the new action picture is touted as a return to realism. Bond is tough and Jason Bourne’s adventures are “gritty.” Yet realism comes at a price, in this case the loss of bodily movements elegant in their efficiency.

Defenders of the impressionistic approach say that it renders “what the action feels like.” But that would entail that the action feels fast and confusing. To whom? Maybe to a duffer like me, if I were dropped into the melee, but not to trained fighters. Bourne isn’t confused: his senses are alert, and his gestures are economical and smooth. So why render the scene as chaotic and show his gestures in jerky cuts? Any fighter overcome by the sensory overload handed to us would lose big.

The classic Asian approach also tries to make us experience how the action feels, but it starts by taking pains to show how it looks. Hong Kong filmmakers constructed a sequence on a firm foundation, and that meant making each shot impossible to misunderstand. They then built those crisp images into what I called the pause/ burst/ pause structure. This simple pattern, capable of great variation. creates a staccato exhilaration.

How? Here’s a first approximation. The stylistic orchestration of the fight trips off optical, auditory, and muscular responses in our bodies, while the pauses give the movement a chance to echo. Instead of a vague busyness, a sense that something really frantic but imprecise is happening, we get a marked rhythm alternating an exact visceral impact with tingling aftereffects. Eisenstein believed that when we see an expressive movement, we reflexively repeat that movement, albeit in weakened form. After one of these sequences you feel tired, but in a good way. We’ve been given a taste of what physical mastery feels like.

Transport

Compare the action scenes of the first Transporter film (2002) with those of Transporter 3 of this year. The first, directed by Hong Kong veteran Yuen Kwai (aka Corey Yuen), isn’t a patch on his best home-ground work (Ninja in the Dragon’s Den, Righting Wrongs, Yes, Madam!, Saviour of the Soul), but the bigger budget provided by Luc Besson gave him a chance to put Jason Statham through some energetic paces, particularly on the oil-slicked floor of a bus garage.

Yuen, a director who sacrifices even dialogue to pictorial rhythm, is fond of percussive insert shots (e.g., the garage scene’s crackling close-ups of Statham snapping bike pedals onto his shoes) and steep, tight angles that spread all of a fight’s players into a diagrammatic composition.

But Transporter 3, choreographed but not directed by Yuen, has buried precise, bone-whacking action under freeze-frames, superimpositions, ramping, color shifts, and other Tony Scott doodling.

Something more sober but just as nerveless is at work in Quantum of Solace. Here the jabbing handheld work of the Bourne pictures has been replaced by steadier framing and smoother traveling shots, but the hyperkinetic, what-did-I-just-see cutting is still there. Again, I think that the filmmakers are worried about the implausibility of the action scenes and so muffles them by a haphazard handling.

Back to basics

Most discouraging has been the way that many Asian filmmakers have taken up the Hollywood approach. Today’s standard Hong Kong action picture is likely to be as visually and kinetically disorganized as the Hollywood product. That’s why I can recommend, as a palate-cleanser if nothing else, Ryoo Sung-wan’s City of Violence (2006), a Korean film recently made available on DVD from Dragon Dynasty.

It is unapologetically formulaic. Pals in a teenage gang grow up to be gangsters and cops. Our protagonist, a big-city cop, returns to the hometown to discover that the weakest of the old crew has become a sadistic overlord. Fights ensue, culminating in a twenty-minute battle in which the hero and another schoolmate penetrate a restaurant where the villain is celebrating his new status. Thrashing their way through a crowded courtyard, then through a narrow tunnel of dining rooms, and finally into a two-story banquet hall, our heroes confront increasingly skilful fighters and eventually face off against their boyhood friend.

Ryoo keeps the action scenes fairly brisk and inventive. The most impressive early one shows the hero surrounded by a battalion of young thugs in a nighttime boulevard. The teens, in an obvious bow to The Warriors, come dressed in ingenious uniforms and display alarming skills with hockey sticks and baseball bats. As in Hong Kong films, judicious long shots keep us oriented to phases of the action.

Borrowing unashamedly from John Woo’s Better Tomorrow series and countless Japanese swordplay films, City of Violence shows flashes of pictorial wit. The cop and his pal realize they’re confronting a platoon of bodyguards at supper when doors slide open to reveal a tunnel-vision perspective of fighters, blobs of black broken rhythmically by women’s pastel outfits.

The film flaunts vivid color and icy focus in a way that much more expensive Hollywood genre movies, with their brackish palettes and soft edges, mostly avoid. (The realism alibi, again.) Even Ryoo’s use of CGI is playfully pretty, in a way that Casino Royale could be only in its credits sequence. Here the gang lord realizes his old pals are approaching.

I don’t want to oversell this film, but it does show that the classic Asian tradition has not expired. Running under ninety minutes without credits, City of Violence aims at nothing more than telling a familiar story with vigor—along the way making us gape and flinch. In a good way.

For arguments about Eisenstein and expressive movement, see my Cinema of Eisenstein, new ed. (Routledge, 2005). The case for Japanese and Hong Kong action films is made in Chapters 12-15 of Poetics of Cinema, and the pause/ burst/ pause pattern is analyzed in Chapter 8 of Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. There, among other things, I try to give Yuen Kwai his due.

Ashes to Ashes (Redux)

DB here:

Hong Kong films constantly shift their shapes. Both film prints and video versions circulate in a bewildering variety of forms. A movie shot in Cantonese (the vernacular of the locals) may be dubbed into Mandarin, the language of the Mainland and of Taiwan. But it may also be dubbed into English, French, or other Western languages; such was the fate of many kung-fu films of the 1970s, as well as later productions like The Killer (1989). I have seen Happy Together in Italian and In the Mood for Love in Spanish. When a movie is exported, it may also be recut to suit the local market. Typically Hong Kong producers have sold films under terms that allowed foreign distributors to do pretty much what they liked with both theatrical and video releases.

Alternatively, the filmmaker may cooperate and remake the film to fit foreign tastes. During the boom years of the 1980s and early 1990s, when many films were funded through presales to Taiwan, it was common to have both a Taiwanese version (usually longer) and a Hong Kong one. Jackie Chan’s Police Story (1985) included extra scenes of Jackie’s antics to satisfy Japanese audiences, and the directors of Infernal Affairs (2002) provided a less desolate ending to satisfy Chinese censors. In addition, filmmakers began circulating “international versions” that would play film festivals, and these might not accord with what was released locally. I’ve discussed one instance earlier on this blog: a version of Days of Being Wild that includes opening material not visible in the international print. My current supposition is that this is a local release print that may have circulated in Western Chinatowns too.

To complicate things further there was the institution of the midnight show. Instead of holding test screenings, Hong Kong producers would preview their films at a few theatres late on weekend nights. Audiences knew that they were acting as guinea pigs and weren’t shy about expressing their displeasure. While filmmakers cringed in the back, viewers might shout insults at the screen. The producers and the director would meet to settle on what changes should be made. Then they would hustle to prepare new versions for the official release in the next week or two.

On top of this, add the next layer of revision: the post-festival rethink. Western directors have redone their movies after discouraging festival response. Probably the most famous instance is the death and resurrection of Vincent Gallo’s The Brown Bunny (2003).Now that Hong Kong and Taiwanese directors circulate on the fest scene, they too have tinkered with their work after premieres, notably Hou Hsiao-hsien, who has reworked films following less than enthusiastic Cannes screenings.

A director’s job is never done?

Like many Hong Kong movies, nearly every one of Wong Kar-wai’s films went through multiple versions. But unlike many directors he seems to enjoy tweaking and rethinking his work. In production he shoots scenes, watches them, reshoots them, recuts them, and reshoots again. Editing and mixing involve the same play with variants. He adds different shots, juggles the order, adds or subtracts music at will.

The process may seem to betray an uncertainty about what he wants his movie to be. For In the Mood for Love, he shot scenes of the central couple making love but didn’t use them, playing with the possibility that the affair is chaste. 2046 began as a high-concept project, based on the fifty-year expiration of the 1997 handover accords, and it went through many different incarnations. At one point it was to be a tale of the intertwining lives of different Hong Kong citizens whose addresses were 2046 on their streets. Even the actors may not know what’s up. At the Cannes premiere of 2046, Maggie Cheung was startled to learn that she was barely in the movie.

Of course most filmmakers rediscover their films at each stage of production, but for Wong the idea of a “locked” version is fairly indeterminate. Virtually everyone now acknowledges that a Wong festival premiere is a first approximation. Delivered in the nick of time (sometimes embarrassingly late), the film is likely to be reworked after initial screenings. Venice and Cannes, Tony Rayns points out, have served as counterparts to the local midnight shows.

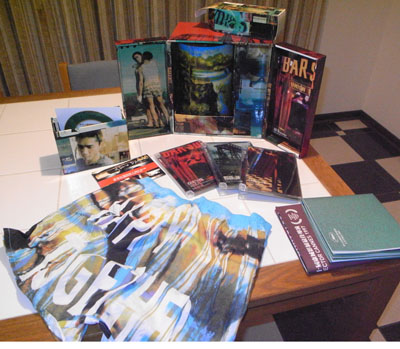

In Planet Hong Kong I suggested that Wong became a shrewd guardian of his brand. He has created high-end ancillary products, not only CD soundtracks but posters, T-shirts, glossy photo books, and limited-edition DVD sets. The Happy Together anniversary box (limited to 2046 units) includes a model of the spinning Iguazu Falls lamp and a pair of men’s briefs. The spinoffs are issued with fancy packaging, and they have usually sold briskly in upscale Asian shops, particularly in Japan. It’s characteristic that Wong’s aborted project Summer in Beijing could serve as a corporate travel logo. At once cult filmmaker and luxury franchise, Wong has every reason to refresh, and re-market, his content at intervals.

In Planet Hong Kong I suggested that Wong became a shrewd guardian of his brand. He has created high-end ancillary products, not only CD soundtracks but posters, T-shirts, glossy photo books, and limited-edition DVD sets. The Happy Together anniversary box (limited to 2046 units) includes a model of the spinning Iguazu Falls lamp and a pair of men’s briefs. The spinoffs are issued with fancy packaging, and they have usually sold briskly in upscale Asian shops, particularly in Japan. It’s characteristic that Wong’s aborted project Summer in Beijing could serve as a corporate travel logo. At once cult filmmaker and luxury franchise, Wong has every reason to refresh, and re-market, his content at intervals.

Yet I don’t maintain that he’s insincere. His drive to redo his films seems to go beyond indecision or commercial calculation. Wong seems to have taken to heart his central theme of the transient moment, the fact that love can be extinguished at any instant. So why not change your films to match your mood today? Further, like Warhol, he seems to enjoy prodigality for its own sake. He enjoys conjuring up one variation after another, multiplying just barely different avatars, and draping in mist the notion of any original text. His films’ basic constructive principle—the constant repetitions that create parallels and slight differences, loops of vaguely familiar images and sounds and situations—gets enacted in his very mode of production.

So he rebuilds even after release. The DVD release lets him tack on unused materials, extra scenes and different endings. That’s enough for most directors, but Wong has long harbored the dream of compiling vast swatches of unused footage in a sort of variorum DVD set of all his films. But why should he have all the fun? He once announced plans to put his footage for Happy Together on the Internet and let anyone make a personal version of it. That didn’t happen, but he did allow his assistants to make Buenos Aires Zero Degree (1999): not only an essayistic making-of but also a handsome reliquary of discarded material, including a gorgeous sequence of two taxis arcing away from each other.

Evil East, Malicious West, and their posse

Now we have Ashes of Time Redux, premiered at Cannes and showing in the US. The most apparent analogies, the oft-revised Blade Runner and the other redux, Apocalypse Now, don’t do justice to Wong’s fussbudget impulses.

For the original Ashes Wong assembled a high-wattage cast that included two of the Heavenly Kings of Cantopop and three glamorous female stars. He spreads out their duties by means of an ensemble plot. At the center stands Ouyang Feng (Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing), a swordsman who has set up a way station on the edge of the desert. He acts as a broker for people who want to hire killers. Another swordsman, Huang Yaoshi (Tony Leung Kar-fai) visits him every year. Ouyang nurses unrequited love for his brother’s wife (usually known as the Woman, played by Maggie Cheung Man-yuk), who lives far away. Huang is also subject to the Woman’s charms, but he is more deeply in love with Peach Blossom (Carina Lau Kar-ling), a woman he saw bathing her horse in a river. Peach Blossom is the wife of yet another wandering swordsman, who is gradually growing blind (Tony Leung Chiu-wai). He too fetches up at Ouyang’s outpost. Huang also runs afoul of the Murongs, a brother and sister who may be the same person (Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia). Meanwhile, a young girl (Charlie Yeung Choi-nei), fortified only with a mule and a basket of eggs, waits at Ouyang’s cabin to hire someone to avenge her brother’s death. Finally, there is Hong Qi (Jacky Cheung Hok-lau), a down-at-heel young killer for hire, who is followed across the desert by his wife.

The interlocking love triangles around a narcissistic man recall Wong’s breakthrough film, Days of Being Wild (1990), although here the parallels and connections are fleshed out through kinship too. The basic relations are at first hard to parse, though a Western viewer who didn’t recognize these stars will have more trouble than a Chinese one. Wong complicates the exposition by fragmenting his scenes and inserting flashbacks, though most of the latter are easy to follow.

He also helps the audience by following a common Hong Kong storytelling principle: reel-by-reel plotting. This breaks the movie into fairly discrete chunks of ten minutes (about a reel) or twenty minutes (about two reels). The first reel sets up the central relation of Ouyang Feng and Huang Yaoshi. Then two reels are devoted to the Murongs and their efforts to trap Huang. The next two reels are spent on the Blind Swordsman, followed by two reels devoted to Hong Qi and the Egg Girl. The last two reels unearth the long-simmering relationship among Ouyang, the Woman, and the despairing Huang. So the plot is actually a bit tidier than it seems at first, although each of these chunks is marbeled with references to other story lines. In Redux, Wong has also divided the plot into seasons, a strategy that accentuates the multipart structure.

Now about all those versions. Preliminary confession: These comments are based on one 35mm screening, and my analytical points are based on a DVD screener.

Keeping it unreal

Before Redux, there were at least two versions of Ashes of Time. One premiered at the Venice festival of 1994, the other became the international standard version. The differences are striking.

The international version has several hyperactive swordfights quite early. In a prologue before the title credit, Ouyang Feng and Huang Yaoshi fight a duel. After that, each is given a combat sequence in which he takes on hordes of assailants. These sequences are rapidly cut, with exaggerated angles, accelerated or slowed motion, and pulsing freeze frames. At the end of the international version comes a brief, parallel epilogue showing the surviving warriors (Ouyang, Huang, Hong Qi, and Murong) in the midst of combat. This epilogue includes a tableau of Yin, the female Murong, writhing ecstatically on a bed of red blossoms.

It’s widely believed among Hong Kong film people that this international version was initially created for the regional market and overseas Chinatowns. Wong added swordplay sequences at the beginning and end in order to satisfy his Taiwanese producers, who wanted more action in this otherwise talky and moody movie. How this version, running about ninety-five minutes without credits, became the standard one I don’t know, but evidently Wong did not control the international rights on the film. In any case, we have the evidence of Derek Elley’s Variety review that these passages were not in the Venice copy.

I’ve seen Ashes in 35mm in several countries, and it’s always been the international version. That is the version available on Hong Kong laserdisc and video, as well as on Japanese DVD (as near as I can tell from my imperfect disc). But the French DVD, released by TF1, is quite different. It runs 87:30 without credits (and assuming 24 fps). This version lacks several scenes, including the opening brawls, and ends with a close-up of the pale face of the Woman looking out to sea. It may be that this French version, billed on the packaging as the “original” one, is close to the Venice print.

Wong reports that he rescued original material, both positive and negative, from various sources. Since some of it was in poor condition, digital versions were made. In the final result, a few shots have been replaced with alternate takes. Yet the film is not simply restored but “reimagined,” as the title Redux indicates.

By and large, the sequence of story events, the shot-by-shot progression, and the monologues and dialogues are the same in both the international version and this new one. What, then, has Wong changed? He has kept nearly all of the brief prologue showing a rapid-fire combat between Ouyang and Huang. He has eliminated the approximately three minutes of the two fights that establish the solo prowess of the fighters. He has also cut the epilogue’s burst of action, retaining only a shot of Ouyang slashing in slow-motion and swiveling in a freeze frame that gradually fades out. In other fight scenes, he has trimmed some elaborate action and at least one gory bit, showing Murong impaling a cat.

Which is to say that he has deleted several conventional displays of the wuxia pian, or “heroic chivalry” film, of the 1990s. In Planet Hong Kong, I argued that Wong’s films often play off the mainstream conventions of his moment. He embraces pop music, pop stars, and pop genres: the triad movie (As Tears Go By, 1988), the melodrama (Days of Being Wild, Happy Together), and the romantic comedy/ cop movie (Chungking Express). But the films rework those conventions too. Wong subtracts a bit of glossiness by emphasizing the grubbiness of location shooting and by mussing up his stars, but then he re-beautifies things through his lustrous images and his unashamed interest in romantic longing. His men alternate between impulsive action and moody withdrawal, and his women mostly lounge about waiting for their men to make a move. (You could do a whole essay on the figure of the Waiting Woman in his work.) The sheer conviction of his style and sentiment can redeem quite hoary clichés, such as the woman’s inevitable complaint that her man never told her he loved her (a crucial turning point in Ashes of Time).

By the early 1990s, the wuxia pian had become a fantasy extravaganza, packed with flying swordsmen, magic potions, special effects, dynamic visuals, pounding music, and play with gender identity. The second and third installments of Tsui Hark’s Swordsman trilogy, a phantasmagoric treatment of the genre, present Brigitte Lin as the bi-gendered Invincible Asia, a vessel of both martial and erotic fantasies.

In part Ashes cites these current formulas in order to rework them. Conventional props like magic wine become tied to themes of memory and regret for missed chances. Discussions of combat strategy are replaced by monologues musing on lost loves. The male/ female masquerade of The East Is Red becomes, in Ashes, a hallucinatory shift of identity (are the Murongs two people or one person?) and forms one point of a thematic continuum centering on men’s desire to possess other men’s women.

Visually as well, Wong borrows and reworks fantasy wuxia conventions. One of the women warriors in The East Is Red (1993) unleashes her volcanic sword skills while standing on the surface of the sea.

Something quite similar happens in Ashes. But once Wong has turned Murong’s ambidextrous gender into a question of identity, you could argue that the geysers of water she unleashes make a broad thematic point: the primal force of a character named both Yin and Yang.

So the original Ashes reworks motifs to be found in Tsui’s extravaganzas, and for all I know in others as well. But apart from the Murong waterworks, these moments of dialogue with the fantasy wuxia pian entries are muffled in Redux.

From the original action scenes Wong has trimmed the turbocharged leaps and swoops, the blasts of “palm power,” and the possibility that a slashing blade can make a hillside explode. Perhaps Wong wanted to leave behind the overwrought world of wuxia fantasy—popular in 1994 but likely to seem cartoonish to Western audiences now. I wonder, though, why he has retained the opening clash between Ouyang and Huang, since the rest of the film presents them as friends. The answer may lie in the original Louis Cha novel, The Eagle-Shooting Heroes, a multi-volume saga that inspired both Ashes and the 1993 Jeff Lau film (co-produced by Wong) called by the novel’s title.

Other changes serve to create greater nuance or lyricism. The synthesizer score has been replaced by a spacious orchestral one, enhanced by stereo. Other stretches of music have been dropped altogether. There is a little less of the Morricone flavor now; the music coaxes rather than hammers. We get more shots of the moon, some fresh landscape vistas, a few more pools of water. Sometimes blood splashes out at us, but at one point an out-of-focus spray of blood is replaced by an optical effect showing wafting dark red billows.

The most pervasive change has involved the color tonalities. The 35mm prints of Ashes I’ve seen have favored a vivid orange-brown palette, with strong blues (sky and water), red accents, and very little green. The video copies vary, but the most commonly available DVD version is notably more russet and lower contrast than the 35mm. Redux, though, is a total rethink. Interiors have lost most of their hard-edged chiaroscuro and become softer and paler. Exteriors, and some interiors, have been keyed toward a hard yellow. The vivid browns and oranges have gone a bit gray, and the blacks verge on green. In addition, some highlights have burned out.

Consider these three frames. The first is a scanned Fujichrome slide that was photographed from a 35mm print. The second frame is from the Hong Kong DVD release. The third is from the Redux screener DVD. None has been photographically adjusted for reproduction here.

All of these are some distance from their sources; for instance, the 35mm slide can’t really capture the range of tonalities of the original, especially in the dark areas. Still, I think the relationship is a fair reflection of the differences. In 35mm, Redux looks a lot more crisp, rich, and detailed than in this DVD frame-grab, but the lemon yellows and pale greens are fairly faithful to my memory of the print.

Wong has taken advantage of ways to improve the film. Seeing the international version in 35mm, I was struck by problems in color matching. Shots apparently taken on different days didn’t always cut smoothly together, and sometimes shot/ reverse-shot passages displayed varying color grades and levels of graininess. By adding fairly consistent tints and by softening certain sequences, Wong has given the film greater tonal consistency. Further, he has upped the artificiality of the film’s look, creating a neutral ground against which certain colors, such as the wan face and ruby lips of the Woman, stand out even more vividly. With its softening and tinting, the film now looks more like a recent release–portions of Soderbergh’s Traffic, say, or some of the tamer stretches of a Tony Scott movie.

Once Redux appears on DVD, admirers will be kept busy plotting some minute differences in shot order and alternate takes. They will marvel at the way that Wong has inserted a few more images (e.g., during the fantasy caressing of Ouyang) but has kept the overall sequence the same length. There will also be intriguing questions. Why the choice of yellow as a key tone? Why the occasional and blatantly video-derived image, such as the pan shots that enframe the central story, and perversely run the opposite direction of their counterparts in the other versions? And why the digitized banks and foliage—maybe just because they look wonderful?

In case you wonder, this frame is not inverted.

I’m still getting accustomed to the film’s new look, and I need to see a print again to verify these general impressions. Still, I like to think that by recasting his film so markedly, Wong has brought his masterpiece back under his control. In this sense, his changes remind me of Stravinsky’s reorchestration of Petrushka and other early ballets. Stravinsky rewrote the scores in order to win performance rights, but he also brought his latest thinking to the task. In the same way, Wong has made Ashes of Time new all over again—available to many more viewers now and hereafter. This daring, fourteen-year-old exercise in avant-pop moviemaking is miles ahead of nearly everything on view right now.

For more on Wong Kar-wai product lines, go here. Wong talks about the restoration of Ashes here and here and in a video interview at the New York Film Festival. For more on reel-by-reel plotting in Hong Kong film, and a broader discussion of Wong’s films, see my Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, 180-182, 271-281. For other critical discussions of Ashes of Time, see Stephen Teo, Wong Kar-wai (London: British Film Institute, 2005) and Peter Brunette, Wong Kar-wai (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005). Unless otherwise noted, the frame enlargements in this entry are taken from a 35mm print of the 1994 international version of Ashes.

Thanks to Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics and Sarah Simonds and Jacob Rust of Sundance 608, Madison, Wisconsin, where Ashes of Time Redux is scheduled to open on 30 January.

Top: WKW and the Hong Kong Film Critics Society, which awarded its Best Film honor to Ashes of Time, spring 1995. Below: DB presents WKW with the award.

Fast forward, now pause

DB here:

Since Kristin got back from Petra (glimpses of her trip are here), we’ve been busy checking the page proofs of the third edition of Film History: An Introduction. It’s due out in February and we have to go over the whole enormous thing, since we’ve made adjustments to almost every chapter. There will be updates of several chapters, as well as two new chapters taking into account developments since our last edition (written in the fall of 2001). We’re also expanding our Notes and Queries supplements, which will appear online. Already our new introduction, discussing some approaches to historical research, is available elsewhere on this site.

This task hasn’t given us much time for blogging. Now, though, we are in a small hiatus before the final push, so each of us hopes to finish a blog entry this week. Kristin will write about a recent visit to Madison of Stefan Droessler, head of the Munich Film Archive. He gave lectures and screened a reconstructed Lubitsch film, The Wife of the Pharaoh (1922). My entry will focus on Wong Kar-wai’s Ashes of Time Redux. I hope to point out some interesting differences among the versions of this remarkable movie.

But to keep your eyes warm, three quick items of note.

I probably don’t have to urge you to see the new Criterion edition of Chungking Express, out in both standard and Blu-ray editions. It’s the Miramax/ Rolling Thunder version, in a crisp transfer with a nice range of color and detail. (I don’t have Blu-ray and so can’t report on that disc.) There’s also a precious 1996 British TV episode in which WKW and a beer-guzzling Chris Doyle tour some Hong Kong locales we see in the movie, tossing out technical information along the way. The show also supplies a more or less documentary record of the Midnight Express fast-food counter a couple of years after the film. Still later, the success of Wong’s film led the owner to upgrade it, with results you can see at the end of this entry.

In the supplementary short, Chris Doyle catches himself talking like a critic and says it’s because “I’ve been reading Tony Rayns.” Not by chance, the Criterion set includes a superb commentary track by Tony, who has worked closely with Wong and Doyle for years. Tony’s fluent discussion anticipates practically every question you might ask about the movie, including why Faye Wong wears a United Airlines uniform.

Chungking Express is my favorite of Wong’s work, but that’s not the main reason I devoted a chapter to it in Planet Hong Kong. I think it’s an important film historically. In the context of Hong Kong cinema, it was as much a breakthrough as was Days of Being Wild, but its offhandedness made it seem more innocuous. Wong makes daring use of plot structure: two stories, barely linked, that connect thematically rather than causally. (We also examine this aspect in one section of Film Art.) Further, Chungking Express is an exhilarating instance of a type of storytelling that fascinates me, what I call “network narrative” and that I analyze in one essay in Poetics of Cinema. Finally, because this film was more widely seen than Wong’s earlier work, it identified him with a particular style: dazzlingly composed shots alternating with smeared and rushed ones, pulsations of saturated color, precise matching of image to music, and a tone of wistful romanticism. Who else could make such an engaging movie about two guys whose girlfriends have left them?

Across his career, Wong’s technique has been more varied than the flash-and-grab breeziness of Chungking Express, Fallen Angels, and Happy Together suggests. The blurred imagery and stuttering slow motion proved easy to mimic and even parody (in Wong Jing’s Whatever You Want, 1994). In the Mood for Love and 2046 returned to the more precise and controlled staging, the nearly abstract use of setting, and the tight close-ups of Wong’s earliest films. For all their virtues, though, these late movies lack the sheer ingratiating zest of Chungking Express. If My Blueberry Nights disappointed you (as it did me), revisit the original and watch it jump off the screen. Keep an eye peeled for those reflections.

Speaking of new DVDs, today the UPS man lugged a Fox Murnau/ Borzage box to our door. This cost more than my first car (and weighs about the same), but it’s a better bargain. My oil-leaking ‘62 Impala did not come fully loaded with Sunrise and City Girl and Seventh Heaven. Dedicated Fox archivist Schawn Belston has labored hard to create this remarkable collection, as robust a contribution to our understanding of film history as his Ford at Fox box a year ago. Tucked inside the chocolate-colored case are twelve films and two handsome books with texts by Janet Bergstrom. An entire book is devoted to the lost Four Devils, and one disc houses a lengthy documentary on the two directors.

Many of the early thirties Borzages are new to me, and I can’t wait to see them. But Kristin and I are very happy to have two lesser-known titles that we love, Lucky Star (1929) and Lazybones (1925). The latter is a striking example of the trend toward the “soft style” of cinematography that swept Hollywood in the 1920s (and that Kristin analyzes in The Classical Hollywood Cinema). Even men were shot with filters, gauzes, and selective focus, creating lyrical images like the one of our hero above. The soft style was about as popular then as the dark, earth-and-steel tonalities we find in so many films today. When our travails with Film History are ended, we look forward to digging into this new Fox treasure chest.

Finally, why not try to identify a mystery movie like the one above? In an email Joe Lindner, archivist at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, writes:

The Nitrate Film Interest Group of the Association of Moving Image Archivists has put together a page on flickr where archivists can post images of unidentified films. The submissions have tended towards silent films and nitrate prints, but sound films and safety elements are welcome as well. The page is also set up for short video clips, and the first video post has just been uploaded from a new scan of a 28mm print in the Academy Film Archive’s collection. This is also a good resource for anyone out there seeking help in identifying film elements, and you do not have to be a member of AMIA to submit images.

This is a remarkable site, and the images are tantalizing. As of this writing, several films have already been identified.

So, three snacks to tide us all over. Check in later this week for some new stuff, when our eyes will focus again.

Vancouver wrapup (long-play version)

Our final post from this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival. Plenty to talk about, so today you get your money’s worth. Oh, wait….it’s free. So you definitely get your money’s worth.

Kristin here—

East

If Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf have been the most prestigious Iranian directors, with their features prominent at film festivals, Majid Majidi has been among the most popular. His Children of Heaven (1997) and The Color of Paradise (1999) both had international success, perhaps largely due to their focus on children and their sentimental, heartwarming stories. The Song of Sparrows (above, 2008) represents a pleasant development and is the best Majidi film I’ve seen. It’s still sentimental and heartwarming, but there’s also a great deal of humor and some highly imaginative situations that give the film more originality than the director’s earlier work.

For a start, the film puts children into supporting roles and sticks continuously with Karim, a hard-working father who strives to make extra money to replace his daughter’s hearing aid. Initially Karim works at an ostrich farm, a completely unexpected locale that generates considerable humor—until one ostrich escapes and Karim loses his job. His one asset is his motorcycle, which he turns into a cab in nearby Tehran, thereby earning good money. Meanwhile his mischievous son and his friends dream of dredging a covered pond near their village and making money by filling it with goldfish to sell.

The triumphs and obstacles that Karim and his son meet make up the bulk of the story, though the life of the tiny cluster of houses in which the main family and their neighbors dwell is charmingly depicted.

The plot of Under the Bombs involves a Lebanese divorcée returning from abroad to search for her sister  and son just after the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel. Only one taxi driver is willing to drive her into the southern region, where bombing could re-erupt at any time; he’s from that area himself, and he’s also attracted to Zeina. This simple story, however, is not half as compelling as the environment in which it takes place.

and son just after the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel. Only one taxi driver is willing to drive her into the southern region, where bombing could re-erupt at any time; he’s from that area himself, and he’s also attracted to Zeina. This simple story, however, is not half as compelling as the environment in which it takes place.

The film opens abruptly with extreme long shots of bombs going off among residential blocks, and as the two main characters travel through scenes of devastation, there is a vivid sense of the action being staged as the events depicted were actually unfolding. One scene depicts French NATO troops landing with the first relief supplies; another shows coffins being dug out of a mass grave and handed over to grieving family members.

Director Philippe Aractingi manages to convey something of the sense of outrage that news coverage of the Hurricane Katrina disaster did in the U.S. As Zeina questions shelter inhabitants about her lost relatives, they tell their tales of losing their entire families and of being separated from loved ones. We can’t tell whether these people may be actors or actual people who have suffered the losses they describe, but a cumulative sense of outrage emerges at the Israelis’ willingness to attack residential areas in their fight against terrorists.

West

Last time I wrote about films from Haiti and Jordan. The festival continued to offer films from countries that have had little or no regular production. El Camino (2007) hails from Costa Rica, though its director, Ishtar Yasin, is Chilean-Iraqi. The narrative is spare, though not in the enigmatic art-cinema fashion of Eat, for This Is My Body. We are introduced to 12-year-old Saslaya and her younger, mute brother Dario. They live with their grandfather in a shack and scavenge in the local dump. The grandfather sexually abuses Saslaya, and the children set out to find their mother. We watch their journey progress in typical picaresque fashion as they meet people, witness a puppet show put on by a vaguely sinister old man, and wander the streets of the local town. Yet we don’t learn where their mother is, why and when she left. The exposition is minimal, as is the dialogue. Watching El Camino, one becomes aware of how much talk most films contain, since the siblings don’t talk to each other or anyone else.

Finally, nearly 70 minutes into a 91-minute film, the children take a ferry. There the other passengers exchange stories about why they are traveling. Gradually we learn that the early part of the film was set in poverty-stricken Nicaragua, and these people are trying to enter Costa Rica illegally to find work. Saslaya reveals that her mother had left with that goal eight years earlier, after their father died. At last we get some sense of the situation, but the pair’s progress is interrupted once the group goes ashore and are shot at by local authorities. Losing Dario, Saslaya wanders into a town and perhaps an unhappy future—one that may echo what had happened to her mother.

This simple story is enhanced by poetic, even at times vaguely surrealist images, such as the two men struggling to move a wooden table who keep crossing the children’s path. With so little narrative to follow, we are encouraged to focus on the hardships and occasional pleasures of a culture which seldom figures in world cinema.

I referred to the two Mexican films that I described in our first Vancouver report as melodramas. Add another  to the list with Francisco Franco’s Burn the Bridges. Two teenagers care for their dying mother in a setting that seems to attract many Latin American filmmakers: a large, decaying mansion. The sister refuses to leave the house, determined to build an isolated world for herself and her brother, to whom she feels an incestuous attraction. He, however, wants nothing more to escape, especially when a tough new kid at school awakens his dawning homosexuality. The action seems a bit overblown at times; I wasn’t always sure whether apparent humor was deliberate or not. But the film and its settings are visually compelling, especially a scene in which the brother and his new friend sneak into a forbidden part of their Catholic school, passing a series of large religious paintings and finally emerging on the roof.

to the list with Francisco Franco’s Burn the Bridges. Two teenagers care for their dying mother in a setting that seems to attract many Latin American filmmakers: a large, decaying mansion. The sister refuses to leave the house, determined to build an isolated world for herself and her brother, to whom she feels an incestuous attraction. He, however, wants nothing more to escape, especially when a tough new kid at school awakens his dawning homosexuality. The action seems a bit overblown at times; I wasn’t always sure whether apparent humor was deliberate or not. But the film and its settings are visually compelling, especially a scene in which the brother and his new friend sneak into a forbidden part of their Catholic school, passing a series of large religious paintings and finally emerging on the roof.

O’Horten is a Norwegian film from Bent Hamer, who has emerged as a film festival favorite with his  previous Kitchen Stories (2003) and Factotum (2005). It’s a character study of a fastidious train engineer striving to cope with retirement; the film plays out in an episodic series of encounters that eventually lead to Horten’s acceptance of his new life. The comedy of eccentricity proceeds in leisurely, continually entertaining scenes. Apart from its mainly quiet tone and somewhat slow pace, it presents no art-cinema challenges to the audience. Norway has chosen it as its candidate for this year’s foreign-language Oscar, and Sony Classic Pictures has announced that it will release the film in the U.S. in early 2009.

previous Kitchen Stories (2003) and Factotum (2005). It’s a character study of a fastidious train engineer striving to cope with retirement; the film plays out in an episodic series of encounters that eventually lead to Horten’s acceptance of his new life. The comedy of eccentricity proceeds in leisurely, continually entertaining scenes. Apart from its mainly quiet tone and somewhat slow pace, it presents no art-cinema challenges to the audience. Norway has chosen it as its candidate for this year’s foreign-language Oscar, and Sony Classic Pictures has announced that it will release the film in the U.S. in early 2009.

Many critics have treated Terence Davies’ Of Time and the City as if it were a sort of elegiac cinematic salute to his native city of Liverpool. Despite the fact that, following the undeserved commercial failure of his excellent adaptation of The House of Mirth (2000), Davies has not made any films, he clearly retains his popularity among aficionados. In fact, however, there is plenty of criticism interspersed with the new film’s lyrical passages. Davies deplores what has become of Liverpool since his childhood there and doesn’t hesitate to assess blame, and he includes harsh comments on religion and on British royalty. He has said that he modeled his documentary on those of Humphrey Jennings, and in particular Listen to Britain (1942), though Jennings’ films had none of the bitterness on display here. Given, however, that Davies was bullied in his school, grew up gay in a more intolerant era, and has had a stunted filmmaking career, such bitterness is hardly surprising.

During Davies’s youth, brick row-houses encouraged communities among the working-class families  necessary to Liverpool’s industries. Using moving and still footage from the era set to classical music, the director manages to create a poignant sense of the grim conditions these people endured. Modern footage shows these old row-houses in ruins—yet shows the council apartment blocks that replaced them to be in almost equally ramshackle shape. Davies contrasts these with some of the few remaining glorious buildings of Liverpool, mainly columned government spaces through which he cranes his camera. He also filmed candid footage of children, perhaps hinting at the one hope for the future, perhaps displaying those whose youthful memories of Liverpool are now being formed in a far less attractive city.

necessary to Liverpool’s industries. Using moving and still footage from the era set to classical music, the director manages to create a poignant sense of the grim conditions these people endured. Modern footage shows these old row-houses in ruins—yet shows the council apartment blocks that replaced them to be in almost equally ramshackle shape. Davies contrasts these with some of the few remaining glorious buildings of Liverpool, mainly columned government spaces through which he cranes his camera. He also filmed candid footage of children, perhaps hinting at the one hope for the future, perhaps displaying those whose youthful memories of Liverpool are now being formed in a far less attractive city.

Of Time and the City marks a welcome comeback, one which I hope will lead to more films by Davies.

DB here:

A miscellany

The Dragons and Tigers programs continued to bring forth very impressive items. Jia Zhang-ke’s 24 City offered a meditation on newly industrializing China, in the vein of last year’s Useless. Aditya Assarat’s Wonderful Town was a prototypical “art movie” that handled a doomed love affair with sensitivity and suspense.

Especially engaging was the new offering from Brillante Mendoza, whose Slingshot I admired at Vancouver last year. In Serbis (“Service”), the Family film theatre lives up to its name only with respect to its management. For here, in the sweltering Philippines town of Angeles, the Pineda family screens porn. The movies attract mostly gay men, who service one another in the auditorium, the toilets, and the stairways. While the matriarch Nanay Flor fights a legal battle, she runs the lives of her employees and kinfolk in a milieu teetering on the edge of confusion. The Pinedas live in the theatre, so that the youngest boy must thread his way to school through a maze of transvestite hookers.

Mendoza confines the action almost entirely to the movie house. That premise recalls Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye Dragon Inn, but Serbis has none of that film’s nostalgia for classic cinema. Here movie exhibition is an extension of the sex trade, exuberant in its tawdriness, steeped in heat and sweat, prey to randy projectionists and stray goats. Almodovar might make something more elegant out of the situation, but Mendoza’s careening camera yanks us from vignette to vignette, from the complaints of the operatic Nanay Flor to her loafing husband to the lusty projectionist with a boil on his buttock. Crowded with vitality, the film can spare its last moments for a burst of reaction shots that imply a whole new layer of comic-melodramatic turpitude.

In other strands of the festival, I enjoyed Nik Sheehan’s lively documentary FlicKeR, which tells the tale of Brion Gyson, friend to the Beats and especially Burroughs. But the real star is Gyson’s Dream Machine. A turntable that spins a slotted cylinder around a lightbulb, the gadget—reminiscent of the Zootrope and other precinematic toys—proved mesmerizing to artists and countercultural fellow travelers. Marianne Faithful, Iggy Pop, and other worthies attest to the hypnotic power of the Machine, which triggered a drug-free high. Sheehan fills in a patch of important cultural history and may inspire others to tickle their alpha waves with a homemade Dreamer.

Almost exactly halfway through Steve McQueen’s Hunger lies a long dialogue scene in which IRA prisoner Bobby Sands explains to a priest why he has to launch a hunger strike. Over cigarettes the two men debate the cost of pushing tactics to this extreme. Running nearly twenty minutes and relying almost entirely on a protracted profile shot, it’s the first extended conversation in what is largely a film of bits of behavior and glimpses of a harrowing place.

Hunger starts by showing the morning routine of a guard at Maze Prison. He washes up. Stiff along a wall, he smokes a cigarette. He painstakingly folds up the tinfoil that wraps his lunch. McQueen’s oblique approach to the subject is maintained when we see a new prisoner brought in. Through him we learn of the cell walls whorled with excrement, the unannounced beatings, and the charade of providing tidy clothes for the prisoners to wear on visitors’ day.

Hunger starts by showing the morning routine of a guard at Maze Prison. He washes up. Stiff along a wall, he smokes a cigarette. He painstakingly folds up the tinfoil that wraps his lunch. McQueen’s oblique approach to the subject is maintained when we see a new prisoner brought in. Through him we learn of the cell walls whorled with excrement, the unannounced beatings, and the charade of providing tidy clothes for the prisoners to wear on visitors’ day.

Comparisons with Bresson’s A Man Escaped are inevitable. McQueen is less rigorous and original pictorially, assembling shots based on current image schemas (planimetric framings, selective focus, extreme close-ups, artily off-center compositions, handheld shots for scenes of violence). And he can underscore points a bit too much, as with the repeated shots of the guard’s scabbed knuckles. Still, compared with Schnabel’s conventionally daring Diving Bell and the Butterfly, the film is willing to be unusually hard on us. Through his nameless prisoners, McQueen treats both brutality and fortitude matter-of-factly. His experience with gallery-installation video seems to have encouraged him to let sheer duration do its job. A patient shot stationed at the end of the corridor waits while a guard, proceeding steadily toward us, clears puddles of urine with a push-broom.

Once Sands passes through his revolutionary catechism, the stakes are clear. The rest of the film returns to the dry, nearly dialogue-free atmosphere of the opening as Sands’ strike ravages his body. The objectivity of the opening yields to Sands’ hallucinatory recollections of his childhood as a long-distance runner. Some may see these images, including birds in flight, as clichéd sympathy-getters, but McQueen’s handling is pretty unsensational. Hunger’s quasi-geometrical structure, the sidelong introduction of horrific material, and the almost clinical treatment of Sands’ deterioration invite us to feel, but they also urge us to think about the price of sacrifice to a cause.

Genre crossovers

Some people consider the “festival movie” a genre in itself–the somber psychological drama with little external action, shot at a slow pace. The stereotype is all too often accurate, but festivals play genre pictures too. Usually these are impure genre pictures, more self-consciously artful or ambitious than multiplex crowd-pleasers. Vancouver had its share of such crossover items.

Hansel and Gretel, a South Korean horror film, played with a classic premise: the happenstance that brings someone from the normal world into a peculiar, isolated household. In this case, a superficial young man lost in a forest stumbles into the House of Happy Children. Here three kids seem to rule their passive, saccharine parents. The situation recalls Joe Dante’s episode of the Twilight Zone film, and during the Q & A director Yim Phil-sung acknowledged the influence of that movie, as well as Night of the Hunter. Brisk, fast-paced, and boasting remarkable sets—dazzlingly lit, jammed with toys and sweets, and ineradicably sinister—Hansel and Gretel could earn cult following in America. Rob Nelson has more here.

Artier, and scarier, was Let the Right One In, a Swedish film by Tomas Alfredson. Adapting Chekhov’s precept that the gun on the mantle in Act 1 has to go off in Act 3, the film begins with the boy Oskar playing with a knife at his window. Later we’ll learn that his stabbing is a fantasy rehearsal for dealing with the bullies who torment him at school. He meets Eli, a girl who comes out only at night, and their adolescent friendship/ love affair on the jungle gym of a housing block is intertwined with a series of vampire attacks on a small town. The tautly constructed script develops in gory directions that I found both unexpected and inevitable. The wintry widescreen cinematography is handsome and precise, and may well look better on 35mm than on the somewhat contrasty digital version available for the festival. It will have a limited opening in the U. S. later this month.

After School, by Uchida Kenji, is an agreeable thriller—somewhat overbusy and implausible in its plotting, but offered with a modesty and assurance that make it worth a watch. The basic situation, of a missing salaryman who may be having an affair, gains suspense by initially restricting our viewpoint to a shabby private detective. Uchida has fun with one of those misleading openings so common nowadays: you think you understand it from the get-go, but when it’s replayed it takes on a new meaning (and explains the title). The final shot, from a surveillance camera trained on an elevator, is a nicely oblique reminder of what seemed at the time a throwaway moment.

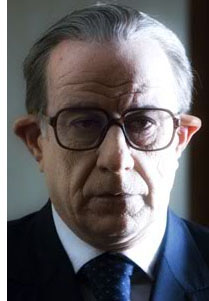

Variety characterizes Il Divo’s genre as “Biopic, Foreign, Political, Drama,” which covers all the bases. Giulio Andreotti, long-time Italian politico, is the subject of the movie, described by an ironic friend as “one-half of the current Italian film renaissance.” The movie surveys Andreotti’s career after the Red Brigades’ murder of Aldo Moro, which triggered a wave of investigations, tribunals, and assassinations, and it concentrates on years after 1995, when Andreotti was accused of links to the Mafia. The first half-hour feels like a single montage sequence, with murders and huddled meetings whisked past us thanks to rapid cutting, swooping camera movements, and pulsating music. (The eclectic score ranges from Sibelius to Gammelpop.) Imagine the sinuous opening of Magnolia, with machine guns.

Variety characterizes Il Divo’s genre as “Biopic, Foreign, Political, Drama,” which covers all the bases. Giulio Andreotti, long-time Italian politico, is the subject of the movie, described by an ironic friend as “one-half of the current Italian film renaissance.” The movie surveys Andreotti’s career after the Red Brigades’ murder of Aldo Moro, which triggered a wave of investigations, tribunals, and assassinations, and it concentrates on years after 1995, when Andreotti was accused of links to the Mafia. The first half-hour feels like a single montage sequence, with murders and huddled meetings whisked past us thanks to rapid cutting, swooping camera movements, and pulsating music. (The eclectic score ranges from Sibelius to Gammelpop.) Imagine the sinuous opening of Magnolia, with machine guns.

When director Paolo Sorrentino settles down to to presenting straightforward scenes, his florid technique persists (he never met a crane shot he didn’t like), but the action is dominated by Toni Servillo’s lead performance, which is weirdly showoffish in its own way. Servillo’s Andreotti is a rigid, buttoned-up fussbudget, an impassive mole of a man; only his epigrams (“Trees need manure to grow”) suggest a mind inside. The maniacally contained performance is as stylized as a turn by Lon Chaney, and as hard to keep your eyes off. Then again, given the glimpses of Andreotti in this report on the Italian response to Il Divo, the portrayal seems only a little exaggerated.

Of course there can be a straightforward genre picture here and there at the festival. The most disappointing instance I saw was The Girl at the Lake, an Italian whodunit that is only a notch or so above a TV movie. More entertaining was Welcome to the Sticks, the fish-out-of-water comedy that has become the top-grossing French film of recent years. A postal supervisor is assigned to a remote village where, he’s convinced, the hicks and the freezing cold will make him miserable. Instead he finds warm-hearted people and plenty of fun. The problem is to keep his wife from finding out how much he’s enjoying himself.

The item is hammered and planed to the Hollywood template. Plot lines: love affairs, both primary and secondary, complicated by work. Structure: four parts, with a neat epilogue that wraps everything up. Motifs: traffic cops, carillon bells, and food, often treated as running gags. Style: overall, less cutting than we might find in Hollywood (8.7 seconds average shot length), but still huge close-ups for extended passages of dialogue. In all, Wecome to the Sticks is sitcom fare that provided, I have to admit, a nice break from a lot of misery on display in the more orthodox festival offerings.

Turning Japanese

In our first communiqué, I talked about films by Kitano and Wakamatsu. I want to add comments on two more Japanese movies I saw, both of exceptional quality.

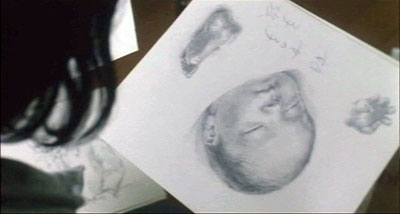

In All Around Us, Hashigushi Ryosuke (Like Grains of Sand, 1995) tells the story of a fraught marriage. The happy-go-lucky Kanao settles into a job as a courtroom artist for TV news, while Shozo, who works in publishing, is a believer in strict rules for their relationship. Their efforts to have a child end unhappily, and Shozo finds her life unraveling. Domestic troubles, amplified by tumult in Shozo’s extended family, play out while every day Kanao covers soul-destroying criminal cases, many involving assaults on children.

The mix of tender sentiments and extreme violence (offscreen, but evoked through chilling testimony) give the film a typically Japanese flavor. Hashigushi filters much of the courtroom horrors through Kanao’s point of view, so that while a defendant berates himself for not killing more people, Kanao watches a mother, and the close-up of her bandaged wrist concentrates all her grief.

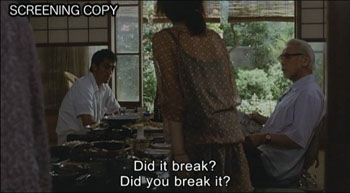

The tact of Hashigushi’s handling is on display in a late sequence. As Shozo struggles out of her depression, her family gathers for what apparently will be her grandfather’s final moments. The adults assemble to discuss the situation while children play in a room behind them. Kanao shows them sketches that they take to be of the father in his final moments.

During their discussion, the adults are distracted by the children shattering an urn in the background.

Here Hashigushi uses staging techniques I’ve discussed in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. Kanao’s display of his sketch favors us; it is centered and frontal. Then, after blocking the children’s play for some time, Hashigushi reveals it—centered and exposed as the adults in the foreground turn to look.

Then most of the family leaves. Hashigushi tracks in slowly to the mother’s confession of her misdeeds, and he ends the shot with a close-up of Shoko.

In a film in which the camera moves seldom and without much fanfare, this creates a simple, powerful impact and refocuses the drama on the psychologically fragile Shoko.

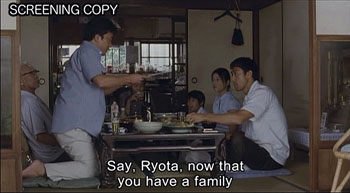

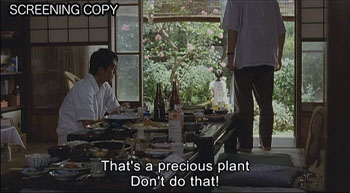

The film I’ve admired most across the festival is, predictably, Still Walking by Kore-eda Hirokazu. It relies on a simple situation. Grandpa and grandma celebrate a son’s death anniversary by a visit from the families of their son and daughter. Across a little more than a day, memories resurface and old tensions are replayed.

Everything unfolds quietly, and the pace is steady: none of the histrionics, both dramaturgical and stylistic, of the Danish Celebration and other psychodramas of dysfunctional families. Still Walking is a classic Japanese “home drama” in the Ozu mold. The conflicts will be muffled and nothing is likely to break the placid surface.

In a stream of vignettes Kore-eda brings each family member to life, displaying an easy mastery in shifting attention from one to another. Gradually he assembles a group portrait of a domineering father, a good-humored mother, a slightly daffy daughter, a son always compared unfavorably to his elder brother, and in-laws striving to be well-received by the grandparents without alienating their spouses. The spirit of Ozu, particularly Tokyo Story and Early Summer, hovers over specifics: a dead brother is invoked, the family poses for a picture, and the patriarch, a retired doctor, has a clinic in his home.

Kore-eda doesn’t get as much credit as he deserves; he’s often overshadowed by extroverts like Miike Takeshi. That’s partly because his is an art of quietness, shown perhaps in its most extreme form in his first feature, Maborosi (1995). At the time I thought it was only one, albeit exquisitely wrought, version of the “Asian minimalism” that sprang up in Taiwan, Japan, China, and even a bit in Hong Kong. I suspect that this trend was largely due to Hou Hsiao-hsien’s masterpieces like Summer with Grandfather, Dust in the Wind, and City of Sadness. A Japanese critic told me that indeed Maborosi was criticized as being too Hou-like.

Now, after After Life, Distance, Nobody Knows, and Hana, Kore-eda has moved to the forefront of Japanese cinema. It seems to me that he maintains the classic shomin-geki tradition of showing the quiet joys and sadness of middle-class life while also plumbing the resources of “minimalist” mise-en-scene.

In Still Walking he works in an engaging, unfussy way. He lets us get to know and like his characters, feeling neither superior nor inferior to them. He builds up his plot more through motifs than dramatic action; a good example is the pop song that the mother loved and that gives the movie its title. The technique, spare but not austere, enforces the relaxed pacing. The film has only around 375 shots in its 111 minutes. While there are plenty of reaction shots and close-ups (the first shot shows women’s hands scraping radishes), some scenes play out in long takes rich in detail.

For example, in a three-minute shot early in the film, most of the family is gathered around a table.

The brother-in-law, a used-car salesman, goes out to the garden to play with the children.

Now the family members discuss the dead brother’s widow, who doesn’t come to family gatherings.

When the father declares that a widow with a child is harder to marry off, he is obtusely insulting his son Ryota’s new wife. Kore-eda marks the disruption with a cut to a reverse angle.

This generates another long take, in which Ryo’s wife Yukari deflates the tension by saying she was lucky to get him. The women then rise and clear the foreground, somewhat as the brother-in-law had by going into the garden. As the family talks, we can see him in the distance helping the kids break open a melon.

Ryo talks about his job restoring paintings. It’s clear that the father disapproves of it, wishing that Ryo, like the deceased brother, had taken up medicine. Kore-eda keeps the garden action as a secondary point of interest by having Ryo glance off occasionally.

But Ryo’s explanation of his job is cut off by the father’s abrupt rise and walk to the doorway, ordering the kids to stay away from one plant.

When the father returns to the table, the nearly two-minute long shot is replaced by a series of singles as Ryo tries to explain his work.

These shots employ one of Ozu’s staging tactics, settling two characters not directly opposite one another but one space apart. The camera seats us across from each one. As a result, the men can be posed frontally, while now we can watch where their glances go—most often, downward. The new setups let us see that the father and son don’t look at each other much.

Instead of moving to these singles right away, as most directors today would, Kore-eda has saved them as a way to articulate the next, more intense phase of the drama. It is arguably a less ostentatious way to raise the tension than the prolonged track inward that Hashigushi uses in All Around Us. (Then again, Hashigushi employs that technique at a climactic moment, while this scene we are still rather early in Kore-eda’s film.) The point is the simplicity and delicacy with which Kore-eda deploys traditional elements of craft.

It wouldn’t be fair to offer a more intensive analysis of this trim work, since it has yet to be widely seen. In the best of all worlds, it will get an American theatrical release.

In all, another wonderful Vancouver festival. See you there next year?

FlicKeR.