Archive for the 'Asian cinema' Category

Dispatch from sunny Vancouver

Ballast.

After six days, plenty to report from the Vancouver International Film Festival. It has been unusually warm and sunny during our first week, but we have diligently spent most of our time in darkened theaters.

Kristin here:

Another country heard from

It’s a rare day when one gets to see a Haitian film. It’s an equally rare day when one gets to see a Jordanian film. On Monday I saw both, and the contrast between them could hardly have been greater.

Eat, for This Is My Body (Mange, ceci est mon corps, 2007), a Haitian/French co-production is Michelange Quay’s first feature. A Haitian-American, Quay received his MFA in directing at New York University.

The film’s opening is extraordinary, with a series of low-altitude helicopter shots beginning over the ocean and then moving rapidly across huge shanty-towns and finally into bleak mountain canyons in the country’s interior. After this passage of flight over bright landscapes, the bulk of the story takes place in and around a quiet, dark, nearly deserted colonial mansion somewhere in the countryside.

I’ve noticed that there seems to be a mini-revival of 1970s-style art cinema conventions. After many years in which art cinema tended to mean intricate psychological studies, a more challenging, formalist avant-garde seems to surface now and then. While watching Eat, for This Is My Body, it occurred to me that it could almost have been called Haiti Song, so strongly did it remind me of Marguerite Duras’s India Song. There enigmatic actions, often dancing, were staged in a colonial house. Eat, for This Is My Body’s action is, if anything, more enigmatic, though in this case the native population is present in the house in the person of a dignified manservant and a group of nine boys brought at intervals into the house, apparently as a treat.

The story is so minimal as to be non-existent. Apart from the nine boys, there are only three characters: an  old woman, a young woman, and the black servant. Not until about 70 minutes into a 105-minute film are these characters identified, though only to the extent that the younger woman is revealed to be the daughter of “Madame.” There are hints of an erotic attraction between the daughter and the servant, though this comes to nothing. The daughter’s wandering through the local town, among the teaming population engaged in washing, selling, and other everyday activities suggests that she may be gaining some insight into native Haitian culture—but this, too, remains a mere hint. Ultimately, the film creates not a narrative, but an evocative narrative situation full of mystery. The film was shot on 35mm and creates a lovely, austere style for the scenes shot within the mansion.

old woman, a young woman, and the black servant. Not until about 70 minutes into a 105-minute film are these characters identified, though only to the extent that the younger woman is revealed to be the daughter of “Madame.” There are hints of an erotic attraction between the daughter and the servant, though this comes to nothing. The daughter’s wandering through the local town, among the teaming population engaged in washing, selling, and other everyday activities suggests that she may be gaining some insight into native Haitian culture—but this, too, remains a mere hint. Ultimately, the film creates not a narrative, but an evocative narrative situation full of mystery. The film was shot on 35mm and creates a lovely, austere style for the scenes shot within the mansion.

The Jordanian film, Captain Abu Raed (2007), takes a more familiar approach, centering around a likable, heartwarming protagonist. Raed, an airport janitor, finds an old pilot’s hat, and the children in his working-class neighborhood assume he really is a pilot. He plays along, less to feed his own ego than to inspire their imaginations through false tales of his adventures abroad. Gradually he becomes more involved in the lives of some of his listeners, and the film progresses from the sugar-coated tone of the opening scenes into a darker situation as Raed seeks a way to save the family of a violent neighbor.

Director Amin Matalqa was raised principally in the U.S., but he returned to his native country for this, his first feature. It is also the first feature film to come from Jordan in decades, and it reflects a slow but distinct movement into movie production in some of the Middle-Eastern countries where conservative religious views have long suppressed it. Captain Abu Raed is technically polished and makes considerable use of Amman cityscapes and ancient ruins as backdrops for the action. It’s also definitely a crowd-pleaser, judging by the sold-out audience I saw it with.

Another rarity is Australian director Benjamin Gilmore’s first fiction feature, Son of a Lion (2007), which he filmed entirely in the Peshawar region of Pakistan. That’s an area adjacent to the northwest border of the country with Afghanistan, notorious as a refuge for Taliban fighters and probably Osama bin Laden. The program lists Son of a Lion as an Australian/Pakistan production. I doubt any Pakistani funding went into it, but Gilmour wrote the script with the advice of the local people, and non-professionals play all the characters. The credits also contain quite a few Pakistanis performing tasks behind the camera.

The story seems inspired in part by the “child’s quest” narratives of the Iranian classics of Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. A strict, traditionalist widower who makes guns wants his 11-year-old son to follow in the family business, while the boy longs to attend school. Apart from his father’s determined opposition, Niaz’s desires fly in the face of the local culture. Gun shops are everywhere, and every male adult seems to be armed. Shopkeeper casually step into the street to fire off weapons to test or demonstrate them. At one point the falling bullet from such random shooting kills a bystander. Between the personal scenes Gilmour intersperses occasional scenes of men sitting around and discussing the situation, debating whether they would shelter Bin-Laden if asked to or turn him in for the reward; they also speculate on America’s image of their part of the world.

and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. A strict, traditionalist widower who makes guns wants his 11-year-old son to follow in the family business, while the boy longs to attend school. Apart from his father’s determined opposition, Niaz’s desires fly in the face of the local culture. Gun shops are everywhere, and every male adult seems to be armed. Shopkeeper casually step into the street to fire off weapons to test or demonstrate them. At one point the falling bullet from such random shooting kills a bystander. Between the personal scenes Gilmour intersperses occasional scenes of men sitting around and discussing the situation, debating whether they would shelter Bin-Laden if asked to or turn him in for the reward; they also speculate on America’s image of their part of the world.

Son of a Lion was shot under difficult and dangerous circumstances on digital video (with post-production handled, amazingly enough, by Peter Jackson’s Park Road Post facility in New Zealand). The shots of the beautiful desert landscapes are not up to those we are used to from Iranian films, but they manage to suggest the grandeur of the area and to give a fascinating and humanizing insight into a region which the American government and media portray as merely a hotbed of terrorism.

Moroccan films are not quite as rare as these, but they’re certainly not common. As Burned Hearts (Morocco/France, 2007) was being introduced, I realized that the only other Moroccan film I had previously seen was by the same director, Ahmed El Maanouni. That had been Trances, a semi-documentary1982 film about a touring pop-music group. It was shown last year at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, having been the first film restored by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Founda tion.

Burned Hearts was another film that seemed to transport me back to the 1970s art cinema. A young man returns to his childhood home after being educated as an architect in Paris. His tyrannical uncle is dying, and flashbacks present the painful memories evoked by the familiar sights and sounds of the city, this exploration of the character’s mental paralysis, along with the black-and-white cinematography of the locations, evokes both Duras and Antonioni. But El Maanouni refuses to concentrate solely on the hero’s concerns, bringing in several intriguing characters from the neighborhood and having groups spontaneously break into song and dance in the streets and shops.

Melodramas from Mexico

These films all come from regions seldom represented in international film festivals, but Mexican cinema  has had a growing presence in such venues in recent years. Two I’ve seen so far are very different from each other. The Desert Within (Desierto adentro, 2008), Rodrigo Plá’s second feature, already has a reputation after winning a cluster of prizes at the Guadalajara Film Festival. A period piece beginning in the late period of the Mexican revolution and extending into the 1930s, it tells the story of a peasant who inadvertently brings destruction on his village and decides that the only way to expiate his guilt is to drag his family far into the desert to build a church. The film takes a bitter view of Catholic guilt, with the protagonist forcing suffering, sexual frustration and death upon his children as his obsession grows.

has had a growing presence in such venues in recent years. Two I’ve seen so far are very different from each other. The Desert Within (Desierto adentro, 2008), Rodrigo Plá’s second feature, already has a reputation after winning a cluster of prizes at the Guadalajara Film Festival. A period piece beginning in the late period of the Mexican revolution and extending into the 1930s, it tells the story of a peasant who inadvertently brings destruction on his village and decides that the only way to expiate his guilt is to drag his family far into the desert to build a church. The film takes a bitter view of Catholic guilt, with the protagonist forcing suffering, sexual frustration and death upon his children as his obsession grows.

The other Mexican film, All Inclusive (2008), deals with another family crisis, but one which takes place over a few days in a luxurious resort on the “Mayan Riviera.” The story is slickly told by director Rodrigo Ortúzar Lynch and beautifully shot by Juan Carlos Bustamante, but I found the story forumulaic. A man who has just been told that he has only a short time to live, goes on vacation with his family, whom he has not informed of his condition. As he struggles with his secret, his wife and three children undergo their own crises. One daughter faces up to the fact that she is a lesbian, the son becomes entangled in an online “affair” with another man’s girlfriend, and the wife, assuming that her husband is being unfaithful, allows a young scuba instructor to seduce her—all this observed by the sardonic goth daughter.

As the tensions grow, a hurricane approaches, and the climactic set of revelations and reconciliations come just as it hits. During the narrative, each of the troubled family members manages to find someone gorgeous willing to bed them and/or hear their tales of woe. The idea that the bearish husband, seeking escape in a local bar, would run across a stunning 23-year-old Cuban woman who would take him into her home, listen at length to him, and finally, of course, teaching him to enjoy life. This gives him the courage to return to his family and tell them the truth. Once the family members have bared their soles, they become a jolly, well-adjusted bunch. It’s an entertaining story with likeable characters and touches of humor—but it’s a bit too much to believe.

Americans in Canada

Apart from Craig Baldwin’s Mock Up on Mu, which David will cover, I’ve seen two American indies so far. Momma’s Man (2008) is directed by Azazel Jacobs. It deals with Mikey, a man traveling on business who has problems with his flights and ends up staying with his parents in their New York loft. Finding excuses not to return to his wife and baby in California, he fritters away his time by reverting to his childhood pursuits. The film takes the daring step of being centered on an unsympathetic character who is the point-of-view figure for all but a few scenes. It manages to convey his gradual move from indecision to obsession and eventually a full-blown breakdown in a believable fashion.

Part of the appeal of Momma’s Man comes from the fact that Mikey’s parents are played by Ken Jacobs, the great experimental filmmaker, and his artist wife Flo Jacobs. It is set in their actual New York loft, a maze of odd filmmaking devices, accumulated pop-culture artifacts, and artworks. The two give extraordinary performances, managing to seem wise and caring and at the same time obsessive and eccentric to a degree that might have contributed to Mikey’s breakdown. Although Jacobs cast an actor as Mikey, one has to suspect that the film is at least somewhat autobiographical, and the casting of his parents has created a uniquely convincing portrait of a family.

David and I were delighted to see RR (2007) on the program. It’s the latest feature by American avant-gardist James Benning. Jim is an old friend, having been a graduate student in our department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison during our early years there. He has concentrated largely on landscape films, usually consisting of lengthy, static shots. This one consists wholly of distant views of trains in what appear mostly to be western and Midwestern locations. In virtually every case the shot holds until the entire train has moved through the shot or out of sight—or stopped, in a few cases.

As so often happens with structural films, small variations become evident to the alert viewer. A shot of a  car stopped for a train passing through a small town contains tiny reflections in the windows of a nearby house that may draw the eye. Some trains are covered with spray-painted graffiti, while others are pristine. One is led to speculate about what the cars may be carrying, and there is a hint of social comment in that activity. A considerable portion of most of the trains consists of tankers, presumably carrying the gasoline or other petroleum products that are currently causing so much trouble in our economy. Others contain numerous livestock cars, and one lengthy train contains nothing else. Among the views of many freight trains, we are treated to a glimpse of a single very short passenger train zipping through the briefest shot in the film.

car stopped for a train passing through a small town contains tiny reflections in the windows of a nearby house that may draw the eye. Some trains are covered with spray-painted graffiti, while others are pristine. One is led to speculate about what the cars may be carrying, and there is a hint of social comment in that activity. A considerable portion of most of the trains consists of tankers, presumably carrying the gasoline or other petroleum products that are currently causing so much trouble in our economy. Others contain numerous livestock cars, and one lengthy train contains nothing else. Among the views of many freight trains, we are treated to a glimpse of a single very short passenger train zipping through the briefest shot in the film.

RR draws us to enter into perceptual play, often with a distinct touch of humor. Few of Jim’s films have contained the measure of their shot length in their mise-en-scene so decisively. The length and speeds of the trains determine the duration of the shots, and one learns to watch for the number of engines pulling or pushing a train as an indicator of how long the train is likely to be. A few shots show trains moving slowly and decelerating at an almost imperceptible rate, teasing us as to whether they will stop altogether and whether the shot will end if they do. At times a train may move through the shot, only to reveal another on a parallel track. One shot plays a very clever game with us. I won’t reveal what it is, but the shot comes perhaps a third of the way through: an oblique view along a track with bushes prominently in the foreground and a short, arched underpass in the middle distance.

Jim has continued to shoot in 16mm in an increasingly digital age, and he consistently manages to make gorgeous images that look more like 35mm. The last one of RR, involving a vast wind farm, is a stunner.

Captain Abu Raed.

David here:

An unusually good VIFF, with many films to get your eyes open.

Enter the Dragons, with Tigers

As usual, the venerable Dragons and Tigers thread is offering some remarkable new films from Asia. The Good the Bad the Weird lived up to its reputation, not to mention its title, offering frenetic action and comic-book (in the good sense) bravura. Sell Out!, a Malaysian satire of corporate maneuvering and media brainwashing, doesn’t get points for subtlety—the goliath is called the FONY corporation—and sometimes it tries too hard. Still, it’s likeable enough, and the fact that it’s a musical adds a welcome bit of froth. The funniest bit, for me, was the opening parody of an art movie, which does actually get integrated into the main action.

Two late works by long-time Japanese directors offered a study in contrast. Kitano Takeshi’s Achilles and the Tortoise starts out sweet and ends very sour, not to say bitter. In telling the story of a boy whose spontaneous love of drawing is forced into narrow commercial channels, Kitano suggests that art is a racket. Across the decades, schools and galleries push the pliant, nearly comatose young artist to create a signature style. He is told to be original, but also he must harmonize with fashion and tradition. With a grim obstinacy he tries to fulfill what the business demands, and to the end he is still trying.

Achilles is less willful than Takeshis’ and Glory to the Filmmaker!, and it tells a more coherent tale, but their glum narcissism is still in evidence. The film cries out for an autobiographical interpretation: is the naïve filmmaker corrupted by exposure to international art cinema? Pictorially, there’s some confirmation of this: Kitano seems to have abandoned his early films’ ingenious use offscreen spaces and planimetric compositions. Like his hero, who can’t achieve artistic singularity, Kitano has become a surprisingly academic and anonymous stylist.

One can’t claim high originality for the style of Wakamatsu Koji either, but at least United Red Army has a gripping premise. The 1960s student movement was driven by opposition to the war in Vietnam and Japan’s cooperation with US policy, but in the following decade some factions emerged that were committed to violent revolution. Small cadres sequestered themselves in mountain cabins. Their exercises in “criticism and self-criticism” devolved into games of increasingly murderous aggression.

One can’t claim high originality for the style of Wakamatsu Koji either, but at least United Red Army has a gripping premise. The 1960s student movement was driven by opposition to the war in Vietnam and Japan’s cooperation with US policy, but in the following decade some factions emerged that were committed to violent revolution. Small cadres sequestered themselves in mountain cabins. Their exercises in “criticism and self-criticism” devolved into games of increasingly murderous aggression.

Wakamatsu’s technique is unstressed: No fancy angles, neverending tracking shots, or virtuoso compositions, just a businesslike application of today’s wobbly handheld look. The cunning lies in the film’s structure. After a half-hour montage summarizing the formation of the group, we are carried into the hideouts and watch the punishment grow more feverish and self-destructive under the domination of two leaders who seem parallel to Mao and Madam Mao.

By the end of the second hour, the remains of the army are on the run, struggling through vast snowy landscapes. Soon four survivors straggle into a ski lodge, hold the owner’s wife hostage, and face their final challenge: wave after wave of police assaults. Waiting for the inevitable outcome, the survivors spare time for grim humor: On 28 February one remarks, “I’m glad the all-out war won’t be tomorrow. Then my death anniversary could come only every four years.” And they can pause for an exercise in political discipline. After a lad takes an extra cookie, he criticizes himself. Stern reprimand follows: “That very cookie you ate is an anti-revolutionary symbol.” Unsentimental and unsparing, United Red Army is over three hours long, with not a longueur in sight.

A man parks his car to pick up some cake at a bakery. He has been away from home all night; now he’s rude to the lady behind the counter. Having bought a couple of cakes, he finds that a sinister black car has double-parked and hemmed him in. His efforts to find the owner lead to a spiral of comic and pathetic confrontations with an orphan child, burly Triads armed with whitewash, and a pimp with a distinctly bad haircut.

Creating something of a network narrative, Chung Mong-hong’s Parking in its modest way offers a cross-section of Taiwanese society, from the prostitute brought over from China to a jaunty barber who more or less controls the switch-points of the story. The ending will strike some as dovetailing all the cards a little too smoothly, but I found it satisfying, if only because it lets our haughty hero show unexpected resilience and compassion. This is only Chung’s second feature, but his work bears watching.

For once, it really is rocket science.

If you’ve already figured out the deep connections among Scientology, the aerospace industry, ritual sex magic, New Age spirituality, and the migration of Los Angeles hipsters to San Francisco in the 1950s, Mock Up on Mu won’t come as news. If, like me, you haven’t the faintest idea about the cat’s-cradle ties among these cultural phenomena, Craig Baldwin’s latest collage-essay-epic-lyric-narrative (all terms he applies to it) is the very thing you need. It’s as exuberantly peculiar as his earlier work like Tribulation 99 and Spectres of the Spectrum, flooding us with a relentless voice-over that splits off from and reconnects with the torrent of images grabbed from all manner of movies.

These earlier films had stories of a sort, swollen conspiracies and ominous coincidences that make Baldwin the eccentric cousin to Fritz Lang. But Baldwin says that these stories couldn’t really engage people, couldn’t get them to identify. Mu tells a more personalized tale. L. Ron Hubbard, founder of Scientology, has colonized the moon and sends Agent C to earth to arrange for people to be shipped up. Agent C runs afoul of Lockheed Martin, corrupt aerospace executive, and becomes attached to Jack Parsons, an early rocketeer who in the 1950s assumed the secret identity of Richard Carlson, so-so Hollywood actor. Meanwhile, Aleister Crowley rules a secret society at the center of the earth….

Or maybe not.

Actually, I won’t swear to much of what I just said. Baldwin’s phantasmagoria tests my memory, as well as plausibility. The story line is swallowed up by what he calls footnotes—swarming digressions, tangents, and flashbacks which are conjured up in imagery that shoots off in a dozen different directions. A few frames from a kiddie science movie or a grade-Z space opera, juxtaposed to Parsons’ rapid-fire account of the history of rocket testing, whiz by almost subliminally.

In any case, there are characters and a more or less linear story. But Baldwin is Baldwin, so things can’t be so simple. He has for the first time staged and shot footage of actors, and their scenes form a sort of string that you can follow. But just as crystals grow in fantastic array along a string, alien footage exfoliates out from the staged scenes. Baldwin aims, he says, at “a dialectical density.”

The result is a narrative experiment I’ve never seen before. With a simple cut, our characters are replaced by figures from other films, who become, in some spectral fashion, both alien inserts and our characters.

Confused? Here’s an example. Agent C (who will turn out to be Marjorie Cameron, muse of many West Coast artists) is riding with rocket scientist Jack Parsons. A series of shots shows them in the car’s front seat.

As the scene goes on, one character gets replaced by another.

Eventually both of our originals have been replaced.

The stand-ins can even change position as the dialogue continues uninterrupted (but always mis-synchronized).

The cuts make the inserted characters surrogates or avatars for our people, but they retain wisps of their original, enigmatic existence. They also remind us that situations like driving in a car are genre stereotypes, schemas so common that individual instances can serve as place-holders for one another. Yet the shots always return to the original actors, anchoring the associations and keeping at least one plane of the narrative moving forward.

These phantasmagoric shifts make the identity transformations in I’m Not There look labored. In Mock Up on Mu Baldwin may have found a new method of cinematic storytelling. Don’t expect Hollywood to pick it up soon.

Pulling half away

How do you tell your audience what it needs to know to understand what it’s seeing, and what it will see? A film can handle exposition (aka backstory) in several ways. Most films favor concentrated and preliminary exposition: Most information is given in one spot and quite early on. This is when you get the opening dialogue when characters say to one another: “Look, you’re my sister. You can tell me.” (Ohh…They’re sisters.) Concentrated, preliminary exposition is usually clunky, but it can be done with finesse, as in the opening soliloquy of Jerry Maguire.

The major alternative is distributed exposition, where information about the backstory is spread out, evenly or unevenly, across the film. This is common in mystery films (as when, under pressure, characters start to confess their relation to the murder victim) and in “puzzle films” like Memento, where we only gradually understand the relations among the characters. Delayed and distributed exposition in straight dramas is common in European art cinema, but it’s rare in the US, although independent films like Claire Dolan and Man Push Cart have made good use of the technique. Kristin already mentioned a similar strategy at work in Eat, for This Is My Body.

Lance Hammer’s Ballast comes garlanded with praise from festivals and major news outlets like the New York Times. For once the advance word is justified. I thought that Ballast was an exceptional intimate drama, focused almost entirely on three people and their layered relationships in a country town in the Mississippi Delta.

At this point I should mention how the three principals are connected, but part of the daring of Hammer’s film is to postpone, for almost an hour, telling you such things. He says he wanted a film that is, like the Delta, “spacious and quiet and slow.” Here the very issue of what we need to know is put into question. By blocking our knowledge of characters’ relationships, Hammer forces us to confront moments of action in a pure state. Each instant, each shot even, gains an integrity and gravity it wouldn’t have if we knew the full dramatic context.

Take the opening. After a brief, wordless prologue showing a boy in a field of crows, we’re in a vehicle pulling up at a bungalow.

The indistinct figure of a man goes to the door. Inside, a brief shot shows a black man’s face in silhouette.

Soon, the first man, who is white and weatherbeaten, is seen at the door, expressing concern for the man inside.

The white man enters, wrinkles his nose at a smell, and proceeds to another room, where a figure, turned from us, lies on a bed.

The black man continues to sit impassively before his TV, though now we can see his face more clearly.

Who are these men? What connects them? Who has died? An ordinary film would tease us with these questions but answer them fairly soon (say, in the next three or four scenes). Here, we will have to wait a considerable time to find out the answers. In the meantime, what we have registered in place of an action arc is the atmosphere of shock, sorrow, grieving, and lowering skies. And almost immediately a rather dramatic event will occur, nearly offscreen, and its causes will remain equally opaque for quite some time.

Ballast’s delay in spelling out its story premises is sustained by two unusually quiet main characters. Lawrence, the man sitting in the darkness, leads a solitary life and speaks reluctantly and briefly. Likewise, the boy James is often silent or alone. These two don’t soliloquize, and they live one day at a time. We must simply observe their behavior, try reading their minds, and more generally absorb the emotional tenor of their lives.

The sparseness of the exposition also puts us on the alert for any scrap of information that will fill in the blanks. For instance, references to “the store” flash out as clues to possible connections among the characters. Hammer’s strategy demands that the audience exercise a degree of patient concentration that most films never ask for.

For roughly the first half of the film, then, Hammer’s narrational technique creatively impedes our full understanding of the basic givens of the story. Once the relationships have coalesced (though there are still some revelations to come), the dialogue becomes more explicit and, some would say, the drama more traditional. But the visual narration continues to mute and elide dramatic moments. At some points pieces of action are rendered opaque by the bobbing, jump-cut camerawork. Most memorably, a clumsy embrace is hidden by a “wrong” camera setup, all the better to make us wonder about the impulses behind the gesture. Hammer matches his oblique plotting with an oblique visual style.

Hammer has cited Bresson as an inspiration, and in conversation he also mentioned late Godard, who has become willing to avoid exposition for nearly an entire film. Unlike Godard, who seems to revel in the pure artifice of withholding information, Hammer appeals to realism: The gradual piecing together of the narrative, he remarked to me, is like our coming to know people in life, bit by bit.

Correspondingly, by the end of Ballast we come to feel more empathy for Hammer’s characters than for Godard’s, and possibly even for most of Bresson’s enigmatic souls. But the empathy doesn’t come cheap, and it isn’t wallowed in. The climax is brushed past in one sideswiping shot; blink and you’ll miss it. In another interview, Hammer speaks of “putting something out and pulling half away.” By leaving us to fill in that half, Hammer exhibits his respect for his characters, and for his audience.

Mock Up on Mu

P. S. For dispatches from 2006 and 2007 editions of the VIFF, type Vancouver into our search box.

They’re looking for us

DB again:

Perhaps you consider Music and Lyrics (2007) a bit of fluff. Bear with me. Apart from offering an ingratiating parody of 1980s music videos, which at the end gets replayed as a parody of 1990s Pop-Up Video, this movie provides a nice example of a technique that film viewers tend to enjoy.

Alex Fletcher, a has-been pop singer, gets a chance to revive his career by writing a love song for Cora Corman, current goddess of teenyboppers. Alex can dash off a melody but he needs a lyricist. His agent has advised him to try to collaborate with the “very hip, very edgy” Greg Antonsky. Their first meeting doesn’t go well. Greg’s lyrics, rhyming witch and bitch, don’t suit Alex’s more romantic style, and Sophie, Alex’s plant-tender, keeps interjecting sweeter lines. After first eyeing Sophie lecherously, Greg decides she’s a simpleton. He dashes out, condemning Sophie and Alex as sentimental fools: “You people disgust me!”

As written, the character of Greg the lyricist is only mildly funny, but the insert shots of actor Jason Antoon raise the comedy thermostat. With his lowered brow and glaring, slightly unfocused eyes, Greg tries to play the badass, but his aggressiveness comes off as egotistical pettiness.

The cutting relies on single shots of each character, in keeping with today’s style of intensified continuity editing. This ensures that we track every character’s facial expression. When Sophie first interrupts, Greg glares, then lolls his head backward; his time is too important to spend with these losers.

In all, Greg is onscreen for about three minutes, and the plot continues without him.

Eventually, Alex and Sophie break up because Alex is prepared to let Cora turn their song into a sleazy number. The climax comes at Cora’s concert, when Alex appears onstage and sings a tune he composed for Sophie: “Don’t Write Me Off.” At the song’s close, we get a shot of him at the piano followed by several reaction shots in the audience, with Sophie’s close-up favored.

After a backstage reconciliation between Alex and Sophie, the film’s second plotline is resolved. Cora performs the number she asked the team to compose, but it’s played the way Sophie had wanted. The up-tempo melody brings Alex and Cora onstage together and then, as the third verse begins, ties together the secondary characters in a series of reaction shots. We first see an African-American backstage handler, whose vigorous swipe of his arm launches a string of smiling responses.

We get shots of Alex’s agent and his daughter, then Sophie’s brother-in-law and his son, and Sophie’s sister and their kids.

Their responses celebrate both the romantic couple’s success and the sincere emotion that the song elicits. This aura of good feeling is confirmed negatively by one more reaction shot.

It is the sort of satisfying surprise that Hollywood often trades on. After being offscreen and out of mind for eighty minutes, arrogant Greg returns. We didn’t see him come to the concert; we didn’t know he was there; we had likely forgotten he existed.

This shot is agreeable because it keeps Greg’s sourness consistent. A more kindly film would show him smiling begrudgingly, won over by the authentic sweetness of the music. But instead he mimics blowing his brains out and lolls his head back as he did before.

Greg’s appalled reaction to the song confirms our initial judgment of his character and our sense of the song’s unpretentious sincerity.

If you’re like me, this unexpected four-second shot makes you laugh. The director, Marc Lawrence, has followed tradition by including humor in a scene of high sentiment, not diluting the happy tone but reinforcing it. Call it corn, hokum, or tosh; claim that it hits below the belt. I won’t disagree. But the mixture of laughter and sentiment works on us like a reflex. And Greg’s response inoculates the movie against seeming wholly naive or cloying. As so often, Hollywood lets us have things, emotionally speaking, both ways.

This response is accomplished through one of the most powerful weapons in the filmmaker’s arsenal. A director can disarm our emotions through a single reaction shot.

Recoil and reaction

The same sort of dynamic is at work in a less lightweight scene. Everybody remembers the moment in Jaws when Sheriff Brody, scooping chum over the side of the Orca, is taken unawares by the arrival of Bruce the shark, bursting out from the background.

But Spielberg, who understands audience response, follows this nifty shot with a topper. In a reverse-angle framing, Brody’s head snaps into the shot with the abruptness of Wile E. Coyote reacting to the Road Runner.

The sudden thrust and halt of Brody’s head sells his stunned facial expression. Our shock at Bruce’s entrance is joined by our uncontrollable urge to giggle at Brody’s cartoonish trajectory and the sheer stupefaction on his face—not fear yet, but rather a recognition of the sheer enormity of the adversary. From here on, his refrain, “We’re gonna need a bigger boat,” will remind us that unlike his shipmates, he has been very nearly head to head with the Great White.

The reaction shot seems like a simple technique. Doesn’t it just spell out or repeat what’s happening? Sometimes, but not always. As we’ve just noticed, it can let the director layer the effect of a scene. Once an action has gained a particular emotional coloring, the reaction shot can add a different tint. The romantic exhilaration of the song in Music and Lyrics is heightened by Greg’s bad-natured gaping. Bruce’s fearsome movement forward is balanced by Brody’s recoil and his comically fixed stare into space.

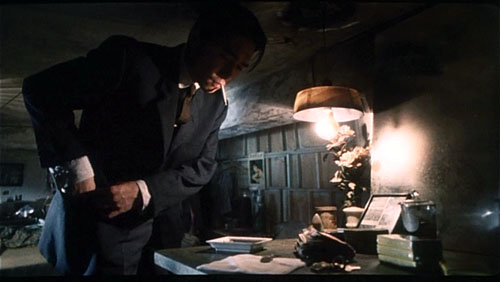

And sometimes the layering and balancing can take place within the reaction itself. In John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow, Mark Lee enters a restaurant and pretends to be playfully feeling up a woman in the corridor. But he’s actually planning to kill a gangland leader, who’s partying in a room off right. First shot: Mark looks winsomely off after the retreating woman. Cut to the leader celebrating.

We might expect that the return to Mark will show his fake expression fade into a sincere one. Instead, Woo simply shows a new expression on Mark’s face as he listens to the party offscreen right.

Eisenstein admired Asian theatre for its “acting without transitions”; here the brief shot of the gangster eliminates the emotional transition taking place on Chow Yun-fat’s face. Mark’s determination is all the more forceful for being so abruptly presented, as if a mask has simply fallen away.

Mirrors like big faces

Prototypically, the reaction shot shows a face expressing emotion. The technique trades on our ability to grasp expressions, often very quickly. We’ve perfected this skill since birth, and there’s evidence that newborns are pre-wired to detect and respond to certain expressions, especially from mom. Exposure to actual expressions in their daily lives allows children to refine and tune this proclivity. So one part of the reaction-shot technique is a very well-practiced skill that cinema has exploited.

Some recent findings in neuroscience suggest that reactions portrayed onscreen can arouse us deeply. Back in 1995, researchers observed that one sort of nerve cell was activated in a macaque monkey’s brain when the monkey reached for a peanut. No surprise there, since that cortical area is known to be a region involved in planning and initiating bodily movements. But researchers noticed that the same cells fired when the macaque watched another monkey reach for a peanut. Soon researchers were finding clusters of these “mirror neurons” in human beings, strongly suggesting that when we see someone do something, our brain responds as if we were doing it ourselves.

Since facial expressions involve stretching and relaxing facial muscles, it’s possible that mirror neurons play a role in arousing empathy. The mere sight of someone smiling or frowning can trigger some of the same neural events as when we smile or frown ourselves. We’ve all experienced a sort of “motor mimicry” when a radiant smile makes us involuntarily smile too. In one set of experiments, neuroscientists found that people’s mirror neurons responded the same way to film shots of disgusted faces as they did to disgusting smells in real life. Reaction shots may gain their strength from not merely our ability to understand facial expressions but the power of facial expressions to trigger in us an echo of the emotion displayed. With a string of shots of smiling faces, as in the Music and Lyrics concert, our own impulse to smile would have to be put down by force of will.

Of course, characters can display their reactions onscreen without being shown in reaction shots in the modern sense. Many films of the earliest years portray the actors in a long-shot framing of the entire action. Realizing that our eyes will turn to areas of high information content like hands and faces, directors often staged and lit the action for easier pickup of the faces. You can see examples of that in this and this earlier entry.

But the reaction shot as such implies cutting, either breaking down the scene through analytical editing or building up a scene from details (so-called constructive editing). In the 1910s, directors began systematically creating a scene from separate shots. (For more on this development, go here and here.) In this approach, particularly as practiced in Hollywood, a person’s facial expression could become part of an ongoing suite of shots, each concentrating on one item of information. Thanks to cutting, the facial reaction could be underscored, sharpened, and timed for best effect. The suddenness of the cuts to reactions in Music and Lyrics and Jaws is central to their effect.

A reaction shot need not be a close-up, and it need not show only one person. One of the funniest reaction shots in cinema, I think, occurs in The Producers, when Brooks cuts from the “Springtime for Hitler” number to the audience’s frozen, slack-jawed response. This long-shot framing suggests that we should think of the reaction shot as a functional category; it’s a role that various types of shots can fulfill.

Still, the development of the close-up as a technique is tied its function of showing responses. In silent cinema the people’s faces, reacting to the flow of story action, are providing a continual measure of the characters’ states of knowledge and feeling. Entire scenes could be played out as a string of intercut reaction shots, as Kuleshov proved in theory and the Americans showed in practice. In Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, as above, the reaction shot is virtually the dominant technique. And point-of-view cutting patterns integrated the isolated close-up reaction shot with images showing what the character was seeing.

With the emergence of sound cinema, you could argue, the reaction shot was briefly demoted. In early talkies, scenes were played in wider shots, and cut-in reactions could, in the hands of inept directors, seem brusque interruptions. But fairly quickly the reaction shot returned, usually as a stressed moment in a scene built out of more distant and neutral framings. Nowadays, with directors using fewer ensemble shots and disinclined to frame actors in prolonged, balanced two-shots, the reaction shot has retained its place in popular moviemaking.

Apart from registering a character’s response, the reaction shot also offers a broader take on the action. Noël Carroll has suggested that the reaction shot can steer us toward the proper way we should construe the whole fictional world we’re witnessing.

For instance, both fantasy fictions and horror stories feature monstrous beings. But in fantasy a troll or griffin might be benevolent. In large part, the way we construe the monster will depend on how the other characters respond. If the hero or heroine looks kindly upon the creature, as in The Golden Compass or Pan’s Labyrinth, then we know we’re not supposed to be horrified. Carroll explains:

A creature like Chewbacca in the space opera Star Wars is just one of the guys, though a creature gotten up in the same wolf outfit, in a film like The Howling, would be regarded with utter revulsion by the human characters.

Reaction shots instruct us in how to respond to the fictional world as a whole.

So robust is the reaction shot that it can stand on its own, if it gets a bit of help from context. In The Third Man, Holly Martins has been trying to defend his old pal Harry Lime from accusations of crooked dealing. When Holly visits a hospital ward, however, he sees what Harry’s bogus penicillin has done to babies. But we don’t; director Carol Reed shows us only Holly’s dispirited reaction.

As Clive James puts it:

The movie’s whole moral structure pivots on that one point. Unless we are convinced that the two men are seeing horrors, there would be no justification for Holly Martins’ delivering the coup de grace to his erstwhile friend.

A chase through feral eyes

Reaction shots can modulate across a scene, as the characters’ feelings change. But I’m also impressed by the way a scene can build emotion by developing from flat, affectless reaction shots to more intense ones. A good example is the long climactic highway chase in Road Warrior.

The outlaw gang is pursuing a tanker truck they think is full of gasoline, while Max, the Feral Kid, and a few warriors ride the monster truck. The scene’s stunts, acrobatics, and vehicular mayhem are impressive, but these qualities have been replicated in a lot of movies. What gives the Road Warrior scene a special pungency are the many reaction shots of the characters mounted on the truck. For the most part we’re aligned with them both physically and emotionally, and we are allowed to share their moment-by-moment reactions to each turn of events.

Early in the sequence, when the tanker team knocks out some pursuers, we get unequivocal reactions of jubilation.

But as the marauding gang gains control of the tanker, the reactions of the team turn to glum, nervously comic dismay.

The scene’s emotional graph is traced most thoroughly in the reactions of the Feral Kid. Throughout most of the film he has two expressions—neutral and fierce. Clinging to the side of the truck, he watches the steady progress of the pursuers with mild apprehension. If he started to shriek with fear now, the scene would have nowhere to build to. I think that we’re inclined to read his expressions as signs of his characteristic stoicism.

But when Max starts to dispatch gang members with his shotgun, the Kid lets out a hoot of pleasure. At one point a thug sends an arrow into the cab. No emotional response from Max or the Kid.

Max blows the thug off the roof of the cab. The kid crows.

The Kid’s laugh licenses us to laugh too—at the businesslike crispness of Max’s response and at the sheer infectiousness of the Kid’s admiration. (Our mirror neurons are presumably working overtime.)

The next phase in the arc comes when Max orders the Kid to crawl out onto the truck hood to retrieve the shells. Now the boy’s expression becomes cautious and a little fearful.

He sprawls on the hood and grabs the shells. At that moment Wez pops up, clinging to the front grille, and we get two lunging reaction shots.

If the Feral Kid had shrieked earlier in the scene, these cuts would have less impact. The high point of the drama is matched by the fact that finally, something has happened to scare the bejesus out of this boy. Even Max has lost his cool, wrenching the wheel ferociously.

Soon, in another laugh-inducing reaction, Wez realizes that he is point man in the crash that is soon to come.

You couldn’t ask for a better example of how reaction shots can be more than a one-off tactic. In Music and Lyrics, the quick insert of Greg gave a little jab to the scene. In Road Warrior, the Feral Kid’s changing reactions add an emotional curve to the progression of the chase. Without him, the scene would lack a whole layer of feeling.

There’s much more to say about the reaction shot. We’d want as well to talk about films that withhold information about characters’ reactions—by using enigmatic or ambiguous reaction shots, or by eliminating reaction shots altogether. (Think Antonioni, Hou, Angelopoulos, Tarr, and others.) Maybe I’ll take those matters up in another entry. For now, let’s salute one of the most enjoyable and arousing dimensions of cinematic storytelling. It only seems simple.

My quotation from Noël Carroll comes from The Philosophy of Horror; or, Paradoxes of the Heart (New York: Routledge, 1990), 16.

Years of being obscure

DB here:

The Cannes screening of Ashes of Time Redux reminds us that Wong Kar-wai has been an incessant reviser of his work. Versions proliferate in different markets—one for Hong Kong, one for Taiwan, one for the international market—and he has sometimes promised online versions, or bonus DVD features. Buenos Aires Zero Degree (1999) by Kwan Pung-leung, provides tantalizing bits of scenes between Tony Leung Chiu-wai and Shirley Kwan. Yet it makes us wonder about the film we might have had if Wong had not decided to cut the whole plot strand out (after keeping Shirley in Argentina for several weeks).

We can add to the list Days of Being Wild (1990), Wong’s breakthrough movie. It’s been circulated for years in an international version, which is currently available on DVD. But some people people have recalled seeing a fugitive, somewhat hallucinatory cut of the film. Some time ago I examined that alternative, and I figured it’s worth showing what I saw. This rareversion prefigures some aspects of Wong’s later style, particularly as seen in In the Mood for Love (2000). I don’t have solutions to all the puzzles it poses, but I’ve gathered some information. If you know something about this “obscure” version, feel free to write to me and I’ll append your comments to this entry.

I need hardly add that there are spoilers galore here. In the images, differences in tonality and aspect ratio spring from my two sources, DVD and 35mm film (which itself fluctuates a little in aspect ratio from shot to shot).

Last things first

Days of Being Wild begins in 1960 Hong Kong. It follows the wanderings of Yuddy (Leslie Cheung), a preening young man who casually seduces women, notably the brassy Lulu (Carina Lau) and the subdued, naïve Lai-chen (Maggie Cheung). Living with his aunt, Yuddy wonders why his mother abandoned him. He finds her living in the Philippines but doesn’t confront her.

At the climax in Manila, Yuddy meets a sailor (Andy Lau) and picks a fight with local thugs. The two men flee by hopping aboard a train. By chance, the sailor was formerly a Hong Kong cop, who was attracted to Lai-chen. On the train, Yuddy is shot by a vengeful thug. The film concludes with a series of shots of Lulu, Lai-chen, and—the big mystery—a slick young man in a seedy apartment who files his nails, combs his hair, equips himself with handkerchief and cigarettes, and sets out for a night on the town. He doesn’t speak, and he has never appeared in the film before. It’s one of the boldest narrative maneuvers in contemporary cinema, and it has occasioned a lot of comment.

The differences in the final sequences begin on the train. In the international version, a shot of the landscape seen from between the cars is followed by a high-angle medium shot of the cop.

This constitutes a mini-flashback, since Yuddy has already died from the gunshot. The cop’s voice-over initiates the exchange: “The last time I saw him, I asked him a question.” (As usual in Wong’s work, we have no way of knowing whom is being addressed; this could be an inner monologue, a report to an unseen character, or simply a self-conscious address to the audience.) For a little more than two minutes, the camera shows only the cop. He asks if Yuddy remembers what he was doing at a certain time. Yuddy understands immediately that the cop has met Lai-chen, and he replies from offscreen, asking about the cop’s relation to her and asking him to tell her that he, Yuddy, has no memory of her. The cop worries that Lai-chen may not even recognize him.

The exchange ends with a wordless shot of Yuddy sitting against the seat, eyes barely open, as an orchestral version of “Perfidia” rises up. The scene ends with an extreme long-shot of the train. The tune was heard earlier when the cop walked away from a nighttime encounter with Lai-chen, so this refrain reminds us of the cop’s yearning for her.

The alternate version doesn’t alter the overall situation much, but it presents different emphases. After the shot between the train cars, we have an off-center long shot of the cop; it’s then that we get the voice-over: “The last time I saw him, I asked him a question.” Cut to a medium close-up of Yuddy, which replaces the shot of the cop. Now for about two minutes he speaks and the cop’s reactions are kept offscreen.

As far as I can tell at this point, the dialogue is identical. In effect, we have a virtual shot/ reverse-shot exchange between the two films! And instead of holding on the framing of Yuddy, or cutting to the cop’s reaction, Wong simply gives us a shot of the two men in facing seats. This is followed by a very different shot of the train, winding through the sort of greenish-blue foliage seen in a famous earlier shot, and there is no music.

The international version puts the emphasis on the cop, who is both challenging Yuddy and obliquely reflecting on his own situation.; hence perhaps the “Perfidia” theme, which is associated with him. The alternate version keeps us focused on Yuddy throughout, our final stare at him, as it were, before a two-shot reasserts an equivalent weight between the two men, and perhaps their memories as well.

The very end

The variations continue in the final shots. Both versions begin with the shot of Lulu striding to the camera in a telephoto framing, above. Now she’s in the Philippines.

In the international version, this shot is followed by Lulu swanning into a bedroom, hanging up her dress, and saying to the landlady, “There’s someone I want to ask you about.”

In the other version, we see her passing through a somewhat sleazy hotel lobby and asking for a spare room. As a result, it’s somewhat less clear that she’s pursuing Yuddy.

The scene shifts to the stadium where Lai-chen works as a ticket seller. (Stephen Teo’s stimulating book on Wong specifies that it’s the South China Athletic Association.) Customers are swarming in for a football match. The obscure version gives us two quick tracking shots of the crowd, with the second ending on a profile shot of Lai-chen in her booth.

The standard version offers only one of the tracking shots and ends with a static framing of the profile composition. But this version adds a shot, beginning the scene with a head-on composition of her at her window.

At this point the alternate version omits two shots that have attracted a lot of critical commentary. Before the shot of Lai-chen shutting up shop, we see a high-angle view of tramway tracks and a shot of a clock outside the stadium.

The clock shot recalls Lai-chen’s meeting with Yuddy, while the tramcar lines recalls her rainy-night encounter with the cop. Instead of these empty shots, the alternate version cuts from Lai-chen in her booth to a shot of a soccer match, evidently seen through a slot in her cabin.

The rest of what follows corresponds in both versions. Lai-chen is seen reading a newspaper before closing the booth.

Both versions likewise wind down with a shot of the phone booth, the one that Lai-chen and the cop had lingered beside, followed by a closer view of the interior. The phone is ringing.

The first shot of the pair recalls, in its high-angle composition, the rainy night that the two met. (Wong’s characters are haunted by memory, but he forces us to use ours too.)

The cop had asked Lai-chen to call him, and the previous scene showed her closing her window, so we might infer that now she’s trying to get in touch with him—not knowing, as we do, that he’s quit the force, become a sailor, and watched her boyfriend die. But we can’t be sure that she’s the one making the call.

The very last shot, showing Tony grooming, is also the same in both versions. (One stage of it is at the very top of this entry.) It is a real crux. Why is Wong showing us this down-at-heel gambler for two and a half minutes? He has no evident connection to any of the characters we’ve followed, and we will never see him again.

Most critics have also accepted Wong’s explanation that he had planned a sequel, one showing how Yuddy’s influence over others lingered long after his death. Patrick Tam told Stephen Teo that the shot was his idea, a setup or trailer for the next film, turning everything we had seen up till now into a lengthy prologue. (1) But Days of Being Wild was a fiasco at the box office, taking in HK$9.7 million, or about $1.25 million US (in a year in which Stephen Chow’s All for the Winner earned over four times that). So the sequel was never made.

Yet these intriguing circumstances don’t really justify the epilogue’s purposes and effects. A causal explanation doesn’t necessarily yield a functional explanation. What role does this disruptive shot play in the film’s overall dynamic? If Wong had made the sequel, it might have been seen as a brilliant stroke; without the followup film, how can we justify its presence?

It’s reasonable to argue, as Teo does, that this vision of Tony’s primping generalizes Yuddy’s case, suggesting that his rootless narcissism is a condition of many young men of the day. You might also suggest that he provides a sort of male equivalent of the playgirl Lulu; just as the cop played by Andy Lau is a good, though unachieved, match for Lai-chen, Tony would pair up better with Lulu than Yuddy’s pal (Jacky Cheung), who pines for her.

Actually, the alternate version sheds a little light on the problem. It doesn’t provide a definitive answer to what Tony is doing there, but it does offer some tantalizing possibilities. In the alternate version, Tony is not only the last character we see, but the first one. And he’s embedded in a sequence that looks ahead to the style for which Wong has been both admired and castigated.

Languor and ellipsis

After the credits, the international version opens with Yuddy striding forcefully into the soccer stadium and mesmerically flirting with Lai-chen. But the print I examined of the obscure version interrupts the credits and shows us none other than the nameless young spark played by Tony Leung Chiu-wai, buffing his nails. (It seems to be an earlier stretch of the final shot, which continues this action.)

Over his image, we hear this in a male voice (no subtitles on the print):

I saw him one more time. He had just returned from the Philippines. He was much thinner than before. I asked him what happened to him. He replied that he just recovered from his sickness. He didn’t want to chat anyway, so I asked him what his sickness was.

Afterwards, we didn’t see each other any more.

This is very mysterious. Whose voice is speaking—Tony’s, Yuddy’s, Andy Lau’s? I can’t identify it. And who is the he referred to? The most plausible candidate is Andy, who may have returned to Hong Kong; and he is looking fairly ill in the film’s final scenes. But it might be the Tony character, as described by one of the other men, or even at a stretch Yuddy himself, who has somehow survived the shooting and returned to Hong Kong.

These ruminations assume that this opening shot frames a flashback by rhyming with the final image of Tony rising from the bed and dressing for his night out. It provides a sheerly formal justification for the final shot, which now completes the action begun at the start. But substantively, we’re still left with a variant of the original question. Instead of asking why end the movie with this remote character, we now ask why he’s used to frame the movie.

The questions have just begun, however. After this eighteen-second shot of the dapper Tony, we get a music montage lasting about eighty-three seconds. It’s quite perplexing. We’re in a warren of corridors, a bit reminiscent of the byways of Chungking Mansions in Chungking Express, and everything is in slow motion. We follow Andy Lau, in a yellow pullover, striding through the darkness and sweating profusely. Then we find him playing cards with some unidentified men. At one point, we see a woman climb the stairs, at other points we glimpse a man with an enormous snake coiled around him. The sequence ends with shots of a hand seizing a cleaver and shots of Andy, back in the corridor, striding away from us. The whole sequence is accompanied by the song “Jungle Drums,” which continues from the shot in Tony’s apartment but is now sung by a female voice (Anita Mui’s).

I was able to take stills of these shots, so I’ll go through them one by one, despite their iffy quality. (The images are very dark, and the print was worn and a little speckled.) After the opening shot of Tony, we get eighteen shots, all in slow-motion, many out of focus, and nearly all using camera movement. Often the cuts are matched in the normal fashion, but sometimes the connection is purely kinetic. As often in Wong’s work, the timing of the cuts synchronizes with beats or melodic lines in the music.

The first shot shows a woman ascending a staircase (pre-echo of the cheongsams in In the Mood for Love), and we pan quickly to Andy looking up after her before setting out down the corridor, where he passes a man with a snake.

Track left with Andy in medium close-up, wiping sweat from his face, then cut to an out-of-focus shot of him still walking.

Andy rounds a corner and proceeds down the hall, extending his hand to the wall. In one of those pseudo-matches, another hand slides open a door, as if completing his gesture. We see a card game inside. The framing suggests Andy’s point of view, but the camera glides back.

In close-up, a hand holds a cigarette. A slight tilt and rack-focus reveals that the card player is Andy.

Suddenly, there’s an out-of-focus shot of the snake sliding along the man’s arm; the shot lasts only 16 frames, or two-thirds of a second. (Here I go again, frame-counting.) This is followed by a blurry shot, only 19 frames, of Andy turning his head. It’s almost as if the snake-shot had attracted Andy’s peripheral vision.

The man with the snake, still out of focus, rises and goes behind a curtain. Cut to a shot of a light bulb shielded by a scrap of paper, with cigarette smoke wafting up.

A classic misterioso shot: A powerfully built man in a suit, seen from the rear, dominates the composition, and the camera tracks back from him. But instead of revealing his identity, the narration cuts back to Andy, who, out of focus, turns back to the game.

A new phase of the sequence starts. The camera pans up a rock wall, showing water trickling down it. Confirming that we’re back in the corridor, we see a hand seizing a chopper from a wall rack. There’s an odd effect of matching movement, with the pan upward picked up by the upward-lifting movement of the cleaver.

From another angle, the hand draws the cleaver across the frame.

Now we get opposing lines of movement—up and to the right in the first chopper shot, horizontally to the left in this shot. The rhythmic bump is accented by the brevity of the shots (30 frames, 21 frames). At the end of this second shot, we can glimpse someone walking away in the dark background.

The cleaver shots are followed by a close-up of Andy walking along the corridor, much like those at the start of the sequence. The final shot shows him walking far away from us. This take seems to be a continuation of the earlier one, when he put out his hand against the left wall. It fades out as the song does.

After the fade-out of Andy walking down the corridor, the credits resume and the scene introducing Yuddy and Lai-chen begins the main plot.

Wong had used a music montage in As Tears Go By (the remarkable “Take My Breath Away” sequence, which I analyzed in Planet Hong Kong). But there it functioned as a lyrical commentary on a sharply delineated, somewhat conventional narrative situation: Wah visits Ngor in Lantau Island and awkwardly communicates his affection for her. This sequence in Days is puzzling because it doesn’t have very clear narrative import. It does set the mood of languor that dominates the film, but it also hints at a situation of criminal danger (gamblers, the hand with the chopper) that is never actualized in the story that follows.

Coming after the fairly opaque opening shot of Tony, this sequence poses other questions. We’ll later learn that Andy is a diligent patrolman; what’s he doing in this den of thieves? Local audiences would recognize the location as the Kowloon Walled City, a sort of island of sheer criminality in the middle of Kowloon. Was Andy an undercover cop before taking up the uniform?

And who is seizing the cleaver? At first I thought it was Andy, but closer inspection shows that’s not likely; there’s nothing in his hands in the final extreme long-shot. Is someone stalking him? We never find out.

Wong is fond of giving us mere impressions of events, sometimes linked to characters’ consciousness, sometimes soaring cadenzas of images blended with music. But unlike the music montage of As Tears Go By and those in later films, this one is almost indecipherable in story terms. Nothing else in Days of Being Wild is as free-form as this stretch of footage. It can stand as an emblem and limit-case of Wong’s interest in using genre conventions poetically, and his reluctance to pay them off in plot terms.

Partial solutions, more mysteries

Back in 2001, Shelly Kraicer, impresario of the Chinese Cinema List, wrote about having seen this version, and several people chimed in with their recollections and opinions. In 2004, I asked several Hong Kong friends about it. Filmmaker, critic, and educator Shu Kei, who has a long memory for Hong Kong film, replied:

I remember the footage you describe. If I’m right, this was the version WKW re-edited after the disastrous midnight premiere of the film, and it was the “official released version” for the regular shows in the following week.

Days was released on 15 December 1990 and played until 27 December, so perhaps this was indeed the version that was seen in its Hong Kong run. In 2001 correspondence on Shelly’s list, Bérénice Reynaud, who saw the “pre-premiere version” of a print straight from the lab, was “positive” that the prologue material was not in that print.

Shu Kei offers some further information about the gambling sequence:

The shots with Andy Lau in a card game and fighting afterwards [sic] were done in a very early stage of the film’s lengthy shoot, in which Lau was playing a gangster-like character in the Kowloon Walled City. (The role, and much of the original concept of Days of Being Wild, were reprised in Jeff Lau’s Days of Tomorrow, 1993.) Andy’s character was later changed to that of a cop.

Two other Hong Kong observers told me that the revised version was designed to make sure that the big stars Tony Leung and Andy Lau had early and prominent entrances, since without the prologue, they play minor roles. Michael Campi reported in the 2001 correspondence: “I was told that in a frantic attempt to retrieve some revenue from the film, it was decided crassly to include Leung Chiu-wai in the opening as well as the closing.”

If this was the strategy, it’s reminiscent of the changes made to the international (originally, Taiwanese) version of Ashes of Time, with the prologue and epilogue showing explosive fighting scenes. Those passages were designed, explains Hong Kong Film Festival programmer Li Cheuk-to, to assure viewers that there would be swordplay in this rather talky movie.

Things are far from settled, though. The prologue is a major crux, but assuming that the last reel I saw was that of the 1990 retooled version, how do the circumstances outlined above explain the disparities in the endings? Why would audience dissatisfaction or producers’ demands force Wong to eliminate the empty shots of the stadium and the clock? Or substitute a different (and more opaque) scene of Lulu in the Philippines? Or change the découpage of the train dialogue between Yuddy and the cop? Or supply a different long shot of the train? Or eliminate the haunting “Perfidia” theme?

Moreover, we still don’t know what the premiere version screened at midnight shows was like. Was it congruent with today’s international version, or was it yet a third variant? In other words, did Wong un-revise the original, or re-revise it? At what point did he or his distributors replace the obscure version with the one in general circulation?

Earlier in June our blog discussed Grover Crisp’s visit to Madison, in which he argued that in an important sense every film exists in alternative versions. We simply have to accept that. It’s especially true of Hong Kong films, which are recut for circulation in many markets. And I like knowing that there’s an especially puzzling variant of Days of Being Wild—one that lets us imagine virtual narrative possibilities and adds to the appeal of this enigmatic movie. Nonetheless, I’d welcome more information about all this, especially from Wong Kar-wai himself.

(1) Stephen Teo, Wong Kar-wai (London: BFI, 2005), 45.

Thanks to Alex Wong for translating the prologue’s voice-over narration for me.

The boy in the Black Hole

PTU.

DB here:

Films from Hong Kong’s Milkyway company earn a lot of praise for their visual qualities. Shooting in Technovision, Johnnie To Kei-fung and other directors have created some of the most vivid and fluid imagery in contemporary cinema. But the movies have soundtracks too. What about them?

When I saw Tsui Hark’s Time and Tide (2000), I staggered out exhausted. I was overwhelmed not only by the delirious plot and its cascade of feverish imagery—who else puts the camera inside a dryer at a laundromat?—but also by what seemed to me the most elaborate soundtrack I’d ever heard in a Hong Kong film.

Shortly after seeing the movie, I visited the Milkyway headquarters and met Martin Chappell, the sound designer of Time and Tide. (For his credits and his company information, go here.) I figured that he could help me hear more in all movies, not just his own.

Years later, during my spring visit to Hong Kong, I got my wish. Martin gave me an interview and sent me several information-packed emails. As I’d hoped, he taught me to listen better.

At the console

Martin Chappell is a concussive burst of enthusiastic energy, an impression aided by the fact that he looks about sixteen. He loves moviemaking and sound design. Growing up in England, he started as a bass guitarist and audio fan, and he studied music and acoustics. When he graduated he worked in sound studios and became a roadie. After a year in Australia, he moved to Hong Kong and got a job in a radio station.

Soon he was working at TNT, creating sound effects for cartoons and dubbing American movies into Mandarin. Hired briefly away by MGM, Martin then shifted to Milkyway. His first effort there was helping on the mix for The Intruder (1996).

Now, with over fourteen years of audio engineering experience, he is sovereign of sound at Milkyway. Ensconced at the heart of Milkyway’s facility, Martin presides over what he calls the Black Hole. The company’s sound studio consists of several rooms, including a Foley studio that is a black hole within the Black Hole.

By Hollywood standards, these studios are minuscule. (Compare the mixing theatre I visited last year for 3:10 to Yuma.) As usual in Hong Kong cinema, work must be fast and tight. Martin typically has a sound crew of three, sometimes including Foley artists. Postproduction sound is usually allotted three weeks, sometimes a little longer. Often he has to prepare a mix on short notice so that visiting critics, festival programmers, or backers can preview a work in progress. As a result, Martin can be found in the Black Hole far into the night, blasting through reel after reel.

Waiting for no man

Most Hong Kong films have a bare-bones approach to sound: dialogue, music, and minimal effects. The sort of detailing that Hollywood offers, especially in Foley techniques, has not been common. There simply isn’t the time and money for a densely mixed track. A lot of time has to be allotted for dubbing the film twice, once in Cantonese and once in Mandarin for the mainland and overseas Chinese market. As a result, even the best Hong Kong films often have a dry, vacant ambiance, which is commonly masked by music. (Perhaps the wall-to-wall music in Wong Kar-wai’s films is an effort to supply a rich sound texture in the absence of other options.)

But Time and Tide had more resources. As part of a Sony initiative to expand into Asian production, which also yielded Crouching Tiger and Kitano’s Brother, it had a large budget by Hong Kong standards. Martin had three months for sound postproduction, “the longest schedule I’ve had in my life,” and a sound crew of eight.

Martin found Time and Tide “a beautiful learning experience.” Working around the clock under the tutelage of veteran postproduction supervisor Hui Koan (The Blade, The Legend of Zu), Martin was encouraged to take chances. He could create rich Foley tracks—remember the tinny ricochet of the little boy’s abandoned skateboard?—and he borrowed ideas from Fight Club, Gladiator, and The Matrix. He was layering sound in the Hollywood manner, albeit on a smaller scale. And he pushed toward wilder possibilities. He recalls the pleasure of putting jungle bird calls under early shots of clubbers wandering through nighttime traffic.

Out and about

Hong Kong looks lovely, but Martin thinks that it’s just as breathtaking in its noise—“a rich sonic soup.” Virtually every chance he gets, he heads out to record in the field.

I pretty much never leave home without my Edirol R-09, and I have a Zoom HR for portable hard disc recording.

It’s important to have a recorder with you all the time. You never know when some drunk is going to burst into song whilst lying in the gutter. In Sparrow, Simon Yam challenges Ka Dung to steal the cop’s handcuffs when they’re outside a bar late at night. So I just pulled the recording I’d made earlier of some drunk guys singing karaoke. It was late one night, I was walking back from the pub, and I heard it echoing out an alleyway.

I feel I’m incredibly lucky. I went out one night to get fresh recordings of a minibus for Linger. I’d scouted the spot, but when I got there the heavens opened and I didn’t have an umbrella. I ran to a nearby bridge—serendipity. I realize it’s next to a tram road, so I recorded buses and trams in the rain, and these sounds feature prominently in Sparrow.

Martin’s wife Marisha often comes with him, either operating or providing effects herself. Recording on the fly freshens up his library, and keeps him alert to new possibilities.

I’m always hoping for a gift from the Ear in the Sky. I’m actually trying to type quietly now, but there’s a band playing downstairs and it’s coming through the walls. They sound terrible, but I think it could be used for a bar scene—late night outside somewhere? . . .

You can see Martin on location in a two-part TV show here.

Back in the studio, Martin revels in software like his Digital Performer and Propellerhead Reason programs. His setup isn’t a Mercedes, like ProTools, he says, more of a Lexus—but in some ways it’s more flexible than the more famous option. Johnnie To wants rich tracks, so “Now I spend almost all my time on Foley and ambience.” Martin “finds the flavor” of the sound through his synthesizer.

I load a recording into Reason and I can play with it in real time on my keyboard—pitching it up or down, sweeping the filters, tweaking the equalization. I do so much with ambiance like this. Sometimes I tie it to the picture, other times I just play on a whim. . . . It’s almost fun.

Alongside his high-tech equipment, Martin employs some home-made items, such as his gobo panel, an upright mesh of stones that is virtually a sculpture (above). The gobo can muffle or redirect sound. Placed between two sources, it can allow clean recording of each track.

Every gun makes its own music

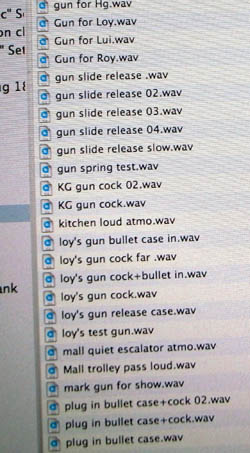

In The Mission, each of the five bodyguards gets a different pistol. Martin gave each one a different sound, labeled in his files by the actor’s name. Here “Roy’s gun” is sometimes coded as “loy’s gun,” and there are plenty of other discrete sound bits on file.

I asked Martin about the mall shootout, which has become a classic in the genre.

There seemed to be so much space in there, and we were adding artificial reverbs, but none of them seemed to work real well. That’s when we decided to experiment a bit, developing things we’d tried in A Hero Never Dies. We just put in the tail of a cannon firing. So that phrase “Bring out the big guns” is literally true here.

There was also a really long gap between some gunshots. We tried adding more, but it felt too busy. So we tried lengthening each gunshot, with the cannon tail reverberating. But that still wasn’t long enough, so we started playing with it, almost jamming with the music. We time-stretched the cannon tails, not just a bit like you’re supposed to. It gave a very artificial but tense sound. If you think it’s music, it might well be.

But even then it wasn’t long enough. So before the next pistol shot, we actually reversed the cannon sound. We get the reversed echo first, then we hear the shot itself! It feels like time has slowed down, then speeded up.

Martin might also have mentioned that these wavering gun reports swoop across left and right channels, creating a dynamic acoustic space for cinema’s most static static gunfight.

Martin also shared his thoughts on the role of sound in fleshing out characterization. After reading Walter Murch’s book In the Blink of an Eye he began to think about how to use sound subjectively. The result was the PTU scene in which Lam Suet, head bandaged, smoking in his car, suffers auditory hallucinations.

Martin acknowledges that there are plenty of conventions that audiences would miss if they weren’t present. When a character hangs up the phone on another character, the disconnected line is signaled through a beep or hum, even though this seldom happens in real life. Martin would also like to hear mobile phone calls in that “headphone bleed-through” effect. He’d also like to handle dialogue like that, “half-overheard, not fully comprehended.”

Still, he finds ways to bypass conventions. In PTU, when the officer played by Simon Yam is abusing the suspect in the video arcade, Martin avoided the library whacking sound, what he calls “the Foley kung-fu cloth flap.” Simon’s slaps are synched to explosions, whizzing missiles, and other arcade sounds. (I offer a visual analysis of one scene in PTU here.)

Ear in the sky

Martin believes that in most films, there’s an immediate need to establish the setting, the placement of the characters, and the scene’s mood. This is done through images, of course, but sound plays an important role. Often a wide shot orients us generally, while sound focuses on one zone of action in that space. “I would guess if you watch TV with no sound, it would be very difficult to really focus. Sound can bring out the visual and guide the eye.”