Archive for the 'Asian cinema' Category

Goodbye to Hong Kong for another year

My Heart Is That Eternal Rose.

DB here, yet again:

Back nearly a week from Hong Kong, I’ve been swamped by backlog and made logy by jetlag. But I wanted to offer last-minute notes from this year’s film festival. I won’t comment on the films that disappointed me or that weren’t in finished form. Instead, upbeat reports, some pictures, and a trio of DVD delights.

On the big screen

Little Cop (1989) starring and directed by Eric Tsang, was part of the festival’s tribute to him. It’s a silly but ingratiating item that anticipates Stephen Chiau’s mo lei tau nonsense comedy. The opening credits are burned onto Tsang’s pudgy body, and thereafter a series of episodes takes him to the anti-prostitution squad (cue the condom jokes) and then the drugs detail. There are engaging gags around a funeral, with a song in praise of death set to the Colonel Bogey march, and lots of intrigue with a master criminal who can steal other people’s faces. Needless to say, since this is Hong Kong, we get many food gags too. Eric called in his bets and got a flurry of walk-ons from top stars like Andy Lau and Maggie Cheung. The only tedious stretch is the last scene, an uninspired clone of Steve Martin’s Absent-Minded Waiter routine. Otherwise, good dirty fun.

Paranoid Park (2007) seemed to me Gus van Sant’s best film in a long time, after the somewhat arid exercises of Gerry and Last Days. Here he’s got a genuine, gripping story that he can render in his detached but lyrical style. The shot of Alex in the shower is particularly gorgeous, and the tracking shot of his tormented walk through town is enhanced by swarms of subvocal recriminations that spurt out from all three channels. My friend J. J. Murphy has provided further commentary on his blog here and here.

If movies about moviemaking risk narcissism, movies about film school must be narcissism squared. The Early Years: Erik Nietzsche Part 1 (2007) centers on a young filmmaker who is transparently Lars von Trier. In-jokes about Danish film culture pile up, and the plot takes almost every easy way out, but Jakob Thuesen keeps the proceedings moving briskly enough. The caricatures are fun, although I think the all-night frenzy of film school life is better captured in Yanagimachi Mitsuo’s Who’s Camus Anyway?

A real revelation: And the Spring Comes (2007, above), by Gu Changwei. A somewhat homely woman with a crystalline singing voice imagines herself headed straight for the Beijing opera. Instead, broken love affairs and unwillingness to lower her ambitions keep her sequestered teaching music in a small town. A tough but touching melodrama rendered in a tactful style, with female lead Jiang Wenlei willing to be unsympathetic.

Many art movies can seem inert in their storytelling—over-under-dramatized, we might say. Carlos Reygados’s Silent Light (2007) escapes this trap. Slow and static, it is suffused with a stark calm that gives gravity to a love affair between a stolid farmer and a woman who runs a café. Planimetric compositions are used imaginatively, and the soundtrack makes daring use of offscreen noises. As an old Dreyer fan, however, I have to worry about the film’s relation to Ordet. Dreyer’s film isn’t exactly ripped off or cited, but it floats behind this one like a spectre before materializing at the climax, perhaps in overbearing fashion. Ordet, suffused with religious debate, earns its miraculous finale, while Silent Light, for all its austerity, is a film of the flesh, and its spiritual coda seems to me somewhat forced. But I’m willing to be convinced otherwise.

Because another guest didn’t appear, I was asked to introduce programs of films by or related to Maya Deren. I enjoyed the chance to see them again, and to reread her writings in the excellent collection Essential Deren. Her work remains stimulating—especially Meshes of the Afternoon and Ritual in Transfigured Time. Her writings blend a stringent formalism, echoing Rudolf Arnheim‘s views of cinematic specificity, and a fascination with myth and non-Western cultures. The boys’ Trance movies (Fragment of Seeking, The Cage, The Potted Psalm) are of historical interest, but hers remain lively. I was happy to see how many young people stayed after the screenings to discuss films that are sixty years old.

On the small screen

In my shopping, I discovered three fine movies on DVD.

*Do Over, a Taiwanese network narrative I liked in Vancouver back in 2006, now available with English subtitles in a so-so transfer (good color and contrast, blurry frame-by-frame pickup). A strong debut film from Cheng Yu-chieh.

*My Heart Is That Eternal Rose, an important 1989 Hong Kong film by New-Wave talent Patrick Tam. This mix of romance and crime stars Kenny Bee, Joey Wang, and a shockingly young Tony Leung Chiu-wai, and Christopher Doyle is listed as one of two cinematographers. The film’s daring stylization marks it as belonging to Hong Kong’s late-80s burst of creativity, and many moments look forward to the luxuriant melancholy of Wong Kar-wai. Clearly Tam (who edited Days of Being Wild and Ashes of Time) was an important influence on Wong. For a long time, I had access to My Heart only on an ugly pan-and-scan laserdisc, but now a widescreen transfer of a worn but bright print offers a considerable improvement. It’s far from perfect, with somewhat slurred movement, but better than nothing.

*Play while You Play, usually known as Cheerful Wind (1981), is Hou Hsiao-hsien’s second film, a romantic drama about a blind man and a somewhat self-indulgent television producer. It’s one of his three commercial “musicals,” and seldom seen, let alone discussed. I think that stylistically these films lay the groundwork for his Taiwanese New Wave films from The Sandwich Man onward. (Go here for more.)

I don’t enjoy this quite as much as his first film, Cute Girl, or his third, The Green, Green Grass of Home, which seems to me nearly a masterpiece. Still, there are lovely moments in Cheerful Wind, including the music montages and a surprisingly offhand ending. Hou films almost casually in the open air, letting passersby drift in and out of the frame (above). The disc, from something called Hoker Records, claims on its package to be 4:3, but it actually preserves the 2.35 format. Unfortunately, it does so through letterboxing, yielding only so-so resolution. No English subtitles. Rumor has it that the irresistable Cute Girl is available in a similar package.

In the point-and-shoot LCD

Four of the brains behind the festival: Ivy Ho, Bede Chang, Li Cheuk-to, and Albert Lee.

Shan Ding, man of all work at Milkyway Image, and the magisterial Peter Greenaway.

Mrs. Johnnie To, Johnnie To, Amy Lau, and Lau Ching-wan, who normally eats nicely.

Joanna Lee, translator extraordinaire and music facilitator to the world.

Jupiter Wong, ace photographer, and Bela Tarr after the enthusiastic reception of The Man from London. My takes on Tarr are here and here and here.

Peter Chan, whose Warlords just won a slew of prizes at the Hong Kong Film Awards.

Jacob Wong, Festival programmer, and Raymond Phathanavirangoon, lately of Fortissimo. I praised Raymond’s presskits last year.

Shu Kei and Michael Campi, just before the premiere of Coffee or Tea, which Shu Kei directed with Kwan Man-hin.

Tourist snap no. 1: Wherever you turn in Wanchai, there’s something interesting to see. Even air conditioners start to look like public sculpture.

Tourist snaps 2 and 3: I often took the Wanchai ferry to screenings on Kowloon.

Tourist snap 4: Coming back late from a screening on the Kowloon side, I would walk past the old clock tower.

. . . A walk fortified by a late-night sample of the Sweet Dynasty’s almond and walnut soup.

In all, as I said at the start of my 3 1/2 weeks here: This will always be the place.

Truly madly cinematically

DB here, still in Hong Kong:

You are a film director. How do you convey to an audience that a character mysteriously sees hidden personalities in other characters?

Filmmakers are problem-solvers, at least sometimes, and I’ve argued elsewhere that we can often explain their creative choices as efforts to pose and solve problems. I ran across an intriguing example during my stay here in Hong Kong. I interviewed Tina Baz, the editor for Johnnie To’s film Mad Detective (2007), which I blogged about from Vancouver in October.

Tina has a fascinating history. Lebanese and French-educated, she attended art school in Beirut and film school in Paris. Armed with a maitrise from the Sorbonne, she began editing. Over a dozen years, she has built up an impressive career. She was editor on The Mourning Forest (2007), A Perfect Day (2005), and several other high-profile projects.

Tina has a fascinating history. Lebanese and French-educated, she attended art school in Beirut and film school in Paris. Armed with a maitrise from the Sorbonne, she began editing. Over a dozen years, she has built up an impressive career. She was editor on The Mourning Forest (2007), A Perfect Day (2005), and several other high-profile projects.

Mad Detective was Tina’s first film for Johnnie To, as well as her first experience with the Hong Kong crime genre. She was accustomed, she says, to the more psychologically-driven narratives of French cinema, and she had to work in a new way during the seven weeks it took to edit the film. This is an unusually long editing time for Hong Kong filmmaking, and it reflects the complicated tasks this film set her.

If you haven’t seen Mad Detective, you will probably want to stop reading. The scenes I’m discussing come fairly early in the film, but they do contain some surprises you might not want to know about in advance.

Headquarters

The rough cut of the film, adhering closely to Wai Ka-fai’s script, displayed a complicated flashback structure. The plot began fairly far into the action and then jumped back to establish the exposition. Central to that exposition is the film’s premise: Detective Bun, played by Lau Ching-wan, solves cases by extraordinary telepathic/ intuitive/ visionary insights. But the original cut blurred that concept, mixing it with an early revelation of the identity of the villain, a corrupt cop named Ko Chi-wai, and background on Bun’s young partner Ho. How to cut through the clutter?

The first step to a solution was to straighten out the chronology and to focus tightly on Bun from the start. The audience needed to understand the film’s eccentric psychological premise—specifically, that Bun’s gift allows him to detect multiple personalities buried within another person.

In talking with me, Tina went over three scenes that establish Bun’s peculiar abilities. (1) The sequences furnish striking examples of how filmmakers find precise technical solutions to storytelling problems. This trio of scenes also follow Hollywood’s Rule of Three. According to this, a key piece of information should be presented three times, preferably in different ways. (2) (Once for the smart people, once for the average people, and once for slow Joe in the back row.) Tina smiled. “This is not something that French directors would say.” The Rule of Three can be seen as another aid to solving the broad problem of clarity—making sure that the audience understands the story.

Discussing all three scenes adequately would take a lot of space and require dozens of stills, so I’ll concentrate on the first two. These should suffice to show how the filmmakers solved a tricky narrational problem.

The first scene takes place in police headquarters and it’s the simplest. It starts with Bun absorbing details of Ho’s investigation. We hear, offscreen, a whining woman complaining that a maniac can’t solve a case. We think at first that it’s the voice of another cop, but after a second complaint from offscreen, Bun looks up. Cut to the whining woman, who stands among the cops.

Bun rises and walks to a pudgy cop who grins ingratiatingly. Now cut from the cop to the whining woman, in a similar composition against the same background.

An over-the-shoulder shot presents Bun staring as we hear the fat cop asking, “Do you recognize me?”

After the fat cop flatters him, Bun head-butts him. Bending over the fallen cop, Bun says, “Shut up. I see and hear you, bitch!” Cut from the bloody-nosed cop to Bun to the bloody-nosed woman.

After Ho dismisses the team, Bun slowly approaches and confides: “I can see the inner personalities of a person” (below). This line of dialogue crystallizes what we’ve seen–the bitchy woman inside the ingratiating man–and prepares for the next few scenes.

On the street

The second vision scene is more complicated, and Tina had several discussions with To and Wai about whether to include it. The new problem, based on the key line above, is to establish that Bun can see not one but several hidden personalities in Ko, the crooked cop. How can this premise be shown?

The major scene coming up shows the two partners confronting Ko at a restaurant. There Bun will envision some of Ko’s inner people manifesting themselves. But there’s also dramatic conflict to be conveyed in the scene, which culminates in a beating in the men’s room. Again, too much information! Tina, To, and their colleagues decided to include an intermediate scene, one that had little dramatic consequence but got audiences more comfortable with the premise.

Ho and Bun trail the suspect along the street, first in a car and then on foot. The results have the kind of precision I’ve pointed to in another Milkyway film, PTU.

In the car, Tina’s cutting establishes the differences between the two cops’ points of view. A two-shot of Ho and Bun yields to a straightforward POV shot of Ko striding along the sidewalk.

But a cut to Bun watching is followed by a shot of seven people in Ko’s place. In a nice instant of uncertainty, a few heads emerge from behind a parked van and are only partially visible. At first glance we might take them for passersby walking ahead of Ko.

Before we can fully identify this band of spirits, and as the car draws abreast, a cut to Ho watching leads to a shot of Ko, whistling.

Another cut to Bun, and now we see, as he apparently does, a full view of the platoon of Ko-personalities striding along whistling.

This mildly wacko variant is consistent with the narration’s mixed attitude toward Bun’s visions: are they supernatural insights or hallucinations?

Bun leaps from the car and pursues Ko’s band of personalities, and a new variation shows him and them in the same frame. But this is re-framed by Ho’s POV, which reasserts that to anyone but Bun, Ko is all by himself.

Abruptly, the visions halt and turn, staring at Bun. By now we are trained to understand what’s happening without a corresponding objective shot of Ko. Ko, we infer, has turned around to check on who’s following him.

Likewise, we can grasp the image of Bun passing through the group of figures as simply Bun walking past Ko.

At this point, we have no need to see the objective action. To and Tina have stressed the absence of an objective view by showing Ho, in the background, looking in another direction and missing this byplay (above). After Bun has passed, the troupe of avatars walks in their new direction, and then we get the objective shot of them “as” Ko.

This effect is anchored when Ho turns and notices Ko going into the restaurant.

As a meticulous touch, Ko’s departure from the frame reveals Bun still walking away in the distance. The geography is simple and impeccable.

The idea of seeing “inner personalities” has been made concrete while undergoing a lot of variation. Sometimes shots of the spirits are sandwiched between shots of Bun looking; sometimes not. Sometimes we have Ho to verify what’s really happening, but sometimes not. And sometimes Bun can be in the same frame as the avatars. Otherwise, Tina points out, the scenes would become boring.

Once the street scene has laid out how Bun sees Ko Chi-wai, the next scene, unfolding in the restaurant and a men’s toilet, can play with the premise still more. Tina explains that the creative team constantly asked, “How far can we go with Bun’s point of view, his vision?” Quite far, it turns out. The premise gets varied further across the whole movie, in imaginative ways. Which is to say that a solution to a problem can pose new problems, which the filmmakers go on to grapple with.

In our discussion, Tina noted that the street scene goes beyond simply giving us information. There’s a disquieting emotional effect when the spirits turn and confront Bun, their expressions ominously blank. Finding a solution to a creative problem often yields an unexpected payoff like this.

Bonus features

As I indicated, I can’t pursue the felicities of the restaurant scene here. Instead, here are some quick final thoughts.

*Mad Detective shows once more the power of basic techniques of performance (e.g., the act of looking), framing, and editing. To and Wai have no need for fancy CGI effects to evoke the “inner personalities” of Ko or the other cop. Our minds make the necessary connections. Lev Kuleshov would have admired the engineering economy of this sequence.

*In passing Tina and I talked about actors’ eyes, a special interest of mine. (3) Tina had noticed that actors try not to blink. She agreed that blinks pose problems for editors: “Blinking is very hard on cutting.” She remarked that Elia Suleiman would strain to keep from blinking until tears flowed from his eyes.

*Mad Detective was signed by both Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai, but their joint projects are usually filmed by To, with Wai supplying the script and consulting as production proceeds. Tina confirms To’s habit of shooting with the whole scene’s layout in his head, using very few takes per shot and not a lot of coverage. The film is “very pre-cut,” she says. You can see this, I think, in the way To relies on matches on action and ends one shot with something that prepares you for the next one.

*To follows Hong Kong tradition of adding all the sound in postproduction. This makes for economy and efficiency in shooting, but it also gives HK films the fluency of silent cinema. The filmmaker gains a freedom of camera placement and is encouraged to think about how to tell the story visually. Tina and Shan Ding, To’s all-around assistant, pointed out that sync sound might make the director depend more on dialogue and static conversation scenes. Still, I think that sometimes they wish for a scene shot with direct sound.

*As with many Milkyway films, several scenes were filmed at the company headquarters. An earlier blog here discussed the ambitious rooftop set for Exiled. For Mad Detective, the fistfight in the restaurant toilet was filmed in the main men’s room of the Milkyway building, with a fake urinal added. Shan Ding provides documentation in the snapshot below, using a double for Lam Suet.

To come: Another Milkyway interview, this one with ace sound designer Martin Chappell. And a final batch of impressions from the Hong Kong International Film Festival, which ends on Sunday.

(1) If you know Mad Detective, you’re aware that Bun’s ability to discern hidden personalities is displayed in an earlier scene. But given the way in which that story action is presented, we can’t say that that his powers are established there. This scene is one of many clever narrational stratagems in a film that benefits from being rewatched.

(2) See Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 31.

(3) Laugh if you must, but I wrote an essay about this. “Who Blinked First?” is available in Poetics of Cinema.

Modest doesn’t mean unambitious

DB still in Hong Kong:

There are plenty of big attractions at this year’s festival. After seeing Om Shanti Om (wildly enjoyed by the audience), I was standing outside the theatre at the Cultural Centre and intersected with hordes of teenagers running to get seats for Candy Rain, a Taiwanese movie starring pop songstress Karena Lam. The result was the Wong Kar-wai homage above.

But many of the best films at this year’s festival don’t come on strong. They simply trust that you will pick up on their quiet virtues. One example is In the City of Sylvia, which I saw at Vancouver and wrote about here. There are others too.

The way we live now

In my previous entry, I mentioned three main sorts of HK films being made these days: programmers, auteur films, and epic coproductions. I neglected a fourth category, that of the small-scale film commenting on local life and history in a heart-warming, nostalgic vein.

Every year a few of these are made, usually attracting a small public. Examples would be Herman Yau’s From the Queen to the Chief Executive (2000) and Give Them a Chance (2006), Samson Chiu’s Golden Chicken (2002) and its sequel (2003), and last year’s Mr. Cinema, a gentle history of Hong Kong from the standpoint of an idealistic movie projectionist. An older example is the sweet-natured Umbrella Story (1995), which integrates CGI footage of Bruce Lee and other stars. Golden Chicken found box-office success, but mostly these projects attract a small public at home and an even smaller one abroad. They don’t, as the saying goes, travel well.

An ambitious example of the grassroots Hong Kong movie had its premiere last week. Ann Hui’s The Way We Are is remarkably bereft of ordinary plotting and dramatic conflict. A widow raises her teenage son in a high-rise apartment in Tin Shui Wa, a district in the New Territories. She works in the fruit section of a supermarket, while he waits for the results of his high school examinations. They meet an old woman living in the same building and they get somewhat involved with her personal problems, the chief one being a hostile son-in-law.

The widow’s mother takes sick. A distant relative dies. An uncle promises to pay for the son’s overseas education. The film refuses to exploit the traditional dramatic potential of any of these situations. There is no tragedy, no sudden burst of violence, no slaps or wails or shattering confrontations. This is a movie in which, by the standards of traditional dramaturgy, nothing happens.

The widow works hard, but she isn’t made saintly; she’s just a kind, devoted person, wearing a perpetually alert half-smile. The son seems at first to be wasting his summer by lounging about, but he dutifully runs errands and takes responsibility for helping his hospitalized granny. The Way We Are makes Edward Yang’s Yi Yi look melodramatic.

The bulk of the film consists of people simply passing their time—working, meeting family and friends, and above all eating. The Way We Are must have more food scenes than any other movie in history. We watch food wrapped, chopped (durians especially), cooked, and consumed. There aren’t many Hong Kong movies that don’t feature food scenes, but this movie puts eating front and center. Again, though, feeding your face doesn’t get the comic or dramatic charge it has in classics like Michael Hui’s Chicken and Duck Talk or Tsui Hark’s Chinese Feast. Eating is just another routine.

Ann Hui has created perhaps Hong Kong’s closest equivalent to Ozu: a film in which daily life, unemphatically presented, is sufficient to engage our sympathies. Granted, The Way We Are lacks Ozu’s formal rigor, his habit of mirroring situations through composition and color design and auditory motifs. Shot on HD in longish, straightforward takes, Hui’s film risks seeming as mundane as its subject. Still, her impulse seems akin to his: a delicate search for human kindness in the commonplace. A title of another of Ann Hui’s films would do for this one: Ordinary Heroes.

Ann Hui has created perhaps Hong Kong’s closest equivalent to Ozu: a film in which daily life, unemphatically presented, is sufficient to engage our sympathies. Granted, The Way We Are lacks Ozu’s formal rigor, his habit of mirroring situations through composition and color design and auditory motifs. Shot on HD in longish, straightforward takes, Hui’s film risks seeming as mundane as its subject. Still, her impulse seems akin to his: a delicate search for human kindness in the commonplace. A title of another of Ann Hui’s films would do for this one: Ordinary Heroes.

The project began as a much grimmer story based on a brutal murder in the neighborhood. But Ann couldn’t bring herself to shoot the script. Investigating Tin Shui Wa, she realized that it was “similar to the squatter huts of the 1950s or the resettlement areas of the 1970s. It is very Hong Kong.” Like the other grassroots films, it recalls earlier periods, using a few judicious montages of stills of people at work and play. It is nonetheless a film about today, showing local life with quiet optimism and good humor. Ann still hopes to shoot the original script as a dark companion piece, creating “a complete statement” on contemporary ways of living. (1)

Two other low-key titles

The Pope’s Toilet (Enrique Fernández, César Charlone). The Pope is visiting Uruguay, and a smuggler decides to build a pay toilet for the hordes who will be swarming into his little town. The intrinsic comedy of the situation is nuanced by the serious portrayal of Beto’s failings, his wife’s patience with his intransigence, and his daughter’s hope of escaping her cramped life. How can you not like a film with a man frantically cycling home, a commode lashed to his bike? A touching surprise that would brighten up any festival’s roster.

Milky Way. I admire Benedek Fliegauf’s Dealer (2004), a nightmarish chronicle of a drug dealer’s hectic final hours, and especially the imaginative network narrative The Forest (2003). This last is a must-see for its careful construction and its moment-by-moment eeriness.

So I was eager to catch Fliegauf’s latest, Milky Way. It consists of ten shots, each one a distant tableau showing a landscape punctuated by human presence. The action develops through minuscule changes, often in a comic direction. Fliegauf compares his compositional strategy to the online game Samorost. To me it recalled Structural narratives like Jim Benning’s 11 x 14 and perhaps owes something to Kiarostami’s 5. On the whole it seemed to me not as original as his earlier works. Still, without words, presenting gorgeous imagery and evocative noises, the film tries for nothing more than a series of calmly unfolding visual conundrums. As Fliegauf remarks, “I think that this film quiets the mind.” (2) That’s something worthwhile in these days of all-out cinematic assaults on your brainstem. Yes, I am thinking of Transformers.

More to come this week–many more films, plus at least one interview with a filmmaker.

(1) Quoted in “The Way We Are,” program notes in catalogue for The 32nd Hong Kong Film Festival (Hong Kong, 2008), p. 94.

(2) Quoted in “Milky Way,” festival catalogue, 189.

Ann Hui before the premiere of The Way We Are.

PS 6 April 2008: Thanks to Mike Walsh for a correction on an earlier version of this entry.

News from the fragrant harbor

DB here:

For those of you who have had problems connecting with this site: Sorry! Our server was down for a couple of days. Ironically, I was one of the last to climb on. Hence the slight delay in this posting from the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Whither Hong Kong film?

The Warlords.

Local cinema is still in the doldrums. As in most countries, Hollywood rules the box office. Production has dropped to about 50 releases last year, and the quality of what I’ve seen over the last week isn’t on the whole strong.

I’m told by a film professional who follows things closely that critics feel that 12-15 local films from 2007 are worth seeing and about 5 are actually good. Those five are Ann Hui’s The Postmodern Life of My Aunt, Derek Yee’s Protégé, Johnnie To’s Mad Detective, Yau Na-hoi’s Eye in the Sky, and Peter Chan’s The Warlords. It’s significant, my friend indicates, that almost never before has the same clutch of films been nominated for best picture, best screenplay, and best director at the Hong Kong Film Awards. (The awards will be given on 13 April.) “The falling industry has reached a plateau,” she remarks.

My sense is that Hong Kong cinema is sustained, however minimally, on three levels. As usual, there are the program pictures, chiefly urban action films and romantic comedies and dramas. These come and go, using local singers and TV stars, and allow theatres to keep their doors open. More creative are the films from local auteurs, principally Johnnie To Kei-fung. (Should I count Wong Kar-wai as a local filmmaker any more?) To’s Milkyway company turns out several worthy items per year, most directed by To. As I indicate in an earlier post, The Sparrow is their upcoming release; it’s also the best Hong Kong movie I’ve seen so far on my trip.

A third category includes the increasingly important China coproductions, nearly always military costume dramas. The emblematic shot: Mighty warriors on mighty steeds galloping toward the camera in a telephoto framing. Add spears, swords, shields, and slow-motion to taste.

The Warlords is the prime instance from last year, but it was preceded by The Myth (2005) and A Battle of Wits (2006). The genre was made popular by Mainland movies like Zhang Yimou’s overdecorated epics, and it has already furnished us two spring releases, An Empress and the Warriors (yes, you read that right) and The Three Kingdoms: Resurrection of the Dragon. Both are straightforward tales of military struggle, centering on loyalty and honor, with relatively little of the palace intrigue that usually furnishes plot motivation.

An Empress, starring Donnie Yen, Leon Lai, and Kelly Chen, is pretty thin going, with overhasty fight scenes and Bumpicam coverage. The only engaging element, apart from the porcupine armor on display in the ads, is the fact that Leon plays a warrior who has retired from the world. He has for obscure reasons turned his patch of the forest into a launching pad for a hot-air balloon. Still, when ninja-like invaders assault his rickety scaffolding, we get a fairly effective action scene that carries a little of the impact of director Ching Siu-tung’s best movies.

An Empress, starring Donnie Yen, Leon Lai, and Kelly Chen, is pretty thin going, with overhasty fight scenes and Bumpicam coverage. The only engaging element, apart from the porcupine armor on display in the ads, is the fact that Leon plays a warrior who has retired from the world. He has for obscure reasons turned his patch of the forest into a launching pad for a hot-air balloon. Still, when ninja-like invaders assault his rickety scaffolding, we get a fairly effective action scene that carries a little of the impact of director Ching Siu-tung’s best movies.

The Three Kingdoms, a Korean-China coproduction directed by Hong Kong’s Daniel Lee, is a somewhat more impressive item. The plot traces the rise of a general (Andy Lau), aided by his mentor (Sammo Hung), and their confrontation with a rival general, whose cause is taken over by his daughter (Maggie Q). There is little characterization; everything hinges on honor, retribution, and service to one’s superior. A tranquil interlude with Andy’s love interest, a shadow puppeteer, is quickly forgotten in the rush to combat. The musical score channels Morricone, and as in Empress, it employs thunderous drumbeats, chanting male choruses, and a keening soprano. Inevitably, we also sense the influence of Wong Kar-wai in the meditative voice-over and the fight scenes (choreographed by Sammo) that recall Ashes of Time in their slurring and spasmodic rhythms.

Are such films really desired by Asian audiences, let alone Western ones? The jury is still out. Thanks to shooting in China and the diffusion of CGI technology, such genre pieces can be made for much less than Hollywood would spend. Three Kingdoms came in at less than US$20 million, which is twice the budget purportedly spent on Empress. But international sales of the genre are spotty, and audience uptake isn’t overwhelming. Somebody will have to tweak the formula creatively. Will it be John Woo, with Red Cliff? Odds are against it, but I’d like to be surprised.

Incorrigibly optimistic, I’m still looking forward to Ann Hui’s newest film, The Way We Are, premiering tonight, and Coffee or Tea, the collaboration of veteran director Shu Kei and his student Mandrew Kwan Man-hin. That’s the closing film of the festival.

Films briefly noted

Kabei–Our Mother.

Other festival highlights for me:

Please Vote for Me! A primary school in Wuhan is introduced to democracy when the teacher decides that the monitor will be elected by the class. There ensues a struggle all too reminiscent of U.S. political campaigns. We have sound bites, applause lines, political operatives (here, overzealous parents), scurrilous charges, personal attacks, and outright bribery. The collision of human nature and democratic ideals make this a charming and thoughtful movie. I can’t imagine anyone not enjoying it, if only for its reminder of how humiliation feels when you’re nine years old.

Observando al cielo. Jeanne Liotta’s ode to astronomical phenomena, at once scientific demonstration and lyrical tribute to the swiveling of the heavens. Visit her website here.

Observando al cielo. Jeanne Liotta’s ode to astronomical phenomena, at once scientific demonstration and lyrical tribute to the swiveling of the heavens. Visit her website here.

Mauerpark. From the Austrian collective Stadtmusik, Tati-goes-Betacam. A long shot of a snow-covered park is at first puzzling, then amusing, then engrossing.

Alexandra. I nearly always like Sokurov. Yes, the films can be a little overbearing, but they have a certain weirdness that keeps them from pretentiousness. Here he gives us another story of family love. An old lady visits her grandson, who’s soldiering in the Caucasus. She rides in a tank, watches men clean their weapons, and putters doggedly about the bivouac. No big emotional climaxes, unless you count her encounters with other old ladies, who have set up a market selling shoes and cigarettes, and the moment when her soldier tenderly braids her hair.

Alexandra. I nearly always like Sokurov. Yes, the films can be a little overbearing, but they have a certain weirdness that keeps them from pretentiousness. Here he gives us another story of family love. An old lady visits her grandson, who’s soldiering in the Caucasus. She rides in a tank, watches men clean their weapons, and putters doggedly about the bivouac. No big emotional climaxes, unless you count her encounters with other old ladies, who have set up a market selling shoes and cigarettes, and the moment when her soldier tenderly braids her hair.

The weirdness comes in the color values–sometimes blinding orange, sometimes bilious green reminiscent of Sovcolor—and in a murmuring soundtrack that blends machine whirs and conversation with barely discernible swoops of orchestral and vocal music. (Since Galina Vishnevskaya plays the old lady, are these fragments from her performances?) Nobody makes soundtracks quite like Sokurov; even an unadorned shot can take on urgency through the drifting whispers our ears struggle to make out.

Jim Hoberman has a discerning review here.

Elegy of Life. Rostropovich. Vishnevskaya. Also a pleasure to listen to, but much more straightforward. A documentary tribute to the great cellist/ conductor and the singer. Since I’m interested in Russian music and cultural politics, this was an unadorned pleasure. To hear Rostropovich compare Prokofiev the classicist with Shostakovich the Mahlerian was especially worthwhile.

Kabei—Our Mother. Yamada Yoji received a lifetime tribute at the Asian Film Awards. Having directed over seventy movies, including the long-running Tora-san series, he’s usually discussed in terms of sheer productivity. But his calm, grave period films Twilight Samurai (2002), Hidden Blade (2004), and Love and Honor (2006) have reminded people that he’s a fine director too. A man of restraint, he never shoots handheld, he seldom moves the camera, and he uses close-ups as high points, not default values. His sobriety makes the 1.85 ratio look as cleanly fitted to the human body as the 1.33 one is. “The last classical director,” Mike Walsh called Yamada after the screening, and it’s hard to disagree.

Kabei was for me the high point of the festival so far. It’s 1940, and a Tokyo intellectual is arrested for “thought crimes.” As he endures prison, his wife and two daughters struggle to make ends meet, with the help of Yamazaki, a loyal student. An epilogue reminds us of the now-elderly mother’s devotion to her husband.

That’s about it, but the poise of the performances and the simplicity of the presentation make this like a film from the era it portrays. I wish I had a DVD to illustrate the craftsmanship that Yamada brings to the very first shot, which unhurriedly introduces the family while the mother simply hangs out wash on the line. I wish I could show you how the moment that a badminton birdie lands on a rooftop pivots from comedy to sadness. I wish I could replicate the composition that hides a weeping Yamazaki from us—a shot that actually makes the audience burst into laughter. Who else would have the film’s biggest star, Tadanobu Asano, keep his back to us for an entire scene?

But maybe it’s better I don’t give such things away. Best to say: Despite all the other movies you see, Kabei shows one way that cinema can still be.

Finally, as antidote to my somewhat depressing diagnosis of the state of HK film, two items. First, the reception for Sylvia Chang‘s Run, Papa, Run showed off her lively charm. Here Sylvia, in black, is flanked by her stars, Yuhan Liu, Rene Liu, Lewis Koo, and Nora Miao, who played in Bruce Lee pictures.

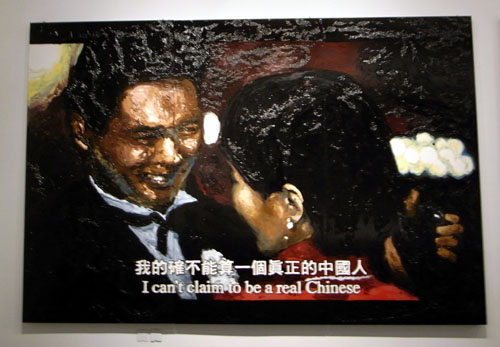

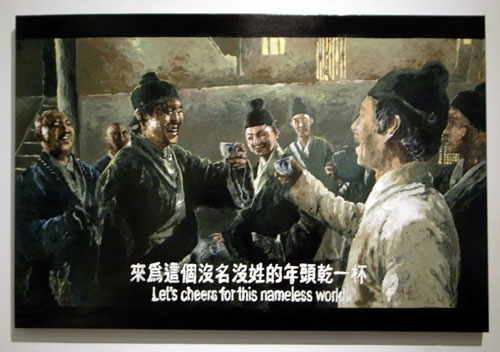

Second, in the entertaining exhibit Made in Hong Kong at the art museum, you will find the work of Chow Chun-fai, whose output includes large, glossy enamel images taken from movies, complete with letterboxing and subtitles (typically about Chinese/ Hong Kong identity). The blocky figures seem both chunkily monumental and somewhat decaying. One of Chow’s huge pictures, derived from Love in a Fallen City, surmounts this blog entry. Below is another, based on King Hu’s Dragon Inn.

More to come in a few days, including, I hope, thoughts on Maya Deren and an interview about sound design in Milkyway movies.

PS later on 27 March: I’ve just discovered a remarkable array of comments on Alexandra in this Criterion thread. John Cope‘s discussion is particularly admirable.