Archive for the 'Books' Category

The 50-50-50 split

Independencia (Raya Martin, 2009); set photo by Alexis Tioseco. Our comment here.

DB here:

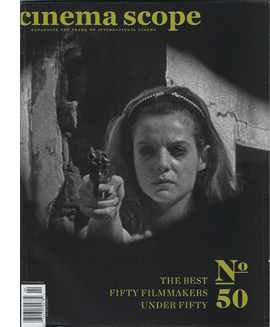

I received the newest Cinema Scope after we had posted our book roundup last week. Awkward timing, but I can still alert you to this splendid effort. In the tradition of Cahiers du cinema (every film magazine wants to be Cahiers), this enterprising Canadian journal has celebrated a benchmark issue with a compendium–issue 50 devoted to 50 filmmakers (all under 50).

It’s a gimmick, but a good one, and of ancient lineage. Cahiers and other French journals established an admirable tradition of obsessively gathering brief entries on filmmakers under a thematic rubric. (The organizing principle: alphabetical order.) In this contribution to the tradition, Mark Peranson, Andrew Tracy, and the rest of the Cinema Scope équipe have outdone themselves.

We get, of course, critics aplenty, and they offer short, sharp takes: Kent Jones on Maren Ade, Scott Foundas on Wes Anderson, Andrea Picard on Liu Jiayin, Shelly Kraicer on Pema Tseden, Chuck Stephens on Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and many more admirable matchups.

This sort of thumbnail catalogue works best when encapsulation is kept to the scale of American menu squibs, or even fortune-cookie apothegms. The phrases don’t have time to turn gently, so they careen. Tony Rayns on Jia Zhangke:

This sort of thumbnail catalogue works best when encapsulation is kept to the scale of American menu squibs, or even fortune-cookie apothegms. The phrases don’t have time to turn gently, so they careen. Tony Rayns on Jia Zhangke:

With a sensibility pitched at the exact mid-point between Robert Bresson and Arthur Freed….

Christoph Huber on Paul W. S. Anderson:

Brit-born Paul W. S. is the elder, least pretentious, and most consistently amusing Anderson of the current director trifecta: its termite artisan.

Michael Koresky on Kore-eda Hirokazu:

He’s at his best when there’s the least mess.

It’s not all praise, either. Adam Nayman contributes a vinegar-doused write-up of Paul Thomas Anderson, although he likes one cut in There Will Be Blood. Alex Ross Perry finds that Fincher’s latest work is uninspiring, but at least now “he can screw around all he wants.”

As if this weren’t enough, filmmakers (another Cahiers tradition) add their voices, and images, to the chorus. So there are Weerasethakul on Lucrecia Martel, Ben Rivers on Bertrand Bonello, James Benning on Sharon Lockhart, and Albert Serra on Zhao Liang, among others.

One purpose of such a Baedeker’s is to alert you to new work. I counted a dozen directors I hadn’t heard of, and another four or five whose films I hadn’t seen. But this kind of enterprise has long-range impact too, especially right now. Cinema Scope 50-50-50 is a bracing psychic antidote to the usual complaints about today’s empty, worthless cinema, and its inferiority to the dazzlement on view on HBO and AMC. For a recent example of this litany, see Wolcott, who yearns for the days of An Unmarried Woman. Projects like the Cinema Scope celebration lift your eyes to the horizon. You can start to believe in cinema’s future.

Are these directors marginal? Not really. The fretful, wayward margins can, when they hit critical mass, become a mighty phalanx. That’s what happened with auteurs in studio Hollywood, art-house movies in the 50s and 60s, new and young cinemas thereafter, etc. The future often lies on the periphery.

We get all this, along with the usual provocative columns by Cinema Scope regulars Peranson, Picard, Rosenbaum, Möller, and Stephens; a sort of storyboard for a new Benning project; Denis Côté musing on his Bestiaire; Hubler’s encyclopedic tribute to Sherlock Holmes movies; an interview with Hoberman (“The decline of the Voice has been going on longer than the death of cinephilia”), and much more. Even the ads are intriguing.

Sooner or later, you know you will obtain this. Why not now? A mere $5.95 Canadian, almost exactly the US price, at least today. This issue is so new that it apparently hasn’t been registered on the website yet, but go there anyway. You might as well subscribe.

Alps (Yorgos Lanthimos, 2011).

Bringing to book

Artists and Models.

Blushing from Bryce Renninger’s generous article about us and the new edition of Film Art can’t keep us from offering another of our occasional entries devoted to new books we like. Get ready for lots of peekaboo links.

The rise of the Soviet Montage film movement of the 1920s and western countries’ knowledge of those films came about largely because of Germany. After pre-revolutionary film companies fled the Soviet Union, taking much of the country’s film equipment with

them, the re-equipment of studios with lighting equipment, cameras, and raw stock was made possible largely through imports from Germany. Once Eisenstein and other directors began making films, they were exported to Germany, where their theatrical success led to further circulation in France, the United Kingdom, the USA, and elsewhere.

them, the re-equipment of studios with lighting equipment, cameras, and raw stock was made possible largely through imports from Germany. Once Eisenstein and other directors began making films, they were exported to Germany, where their theatrical success led to further circulation in France, the United Kingdom, the USA, and elsewhere.

There was a direct link between Soviet and German socialist film production and distribution that is too little-known today. In 1921, Willi Münzenberg forms the Internationalen Arbeiterhilfe (the IAH, known in Russia as Meschrabpom), based in Berlin. In 1924, the organization founded a film studio in Moscow, Rus. A year later, a sister company, Prometheus, was formed in Berlin. Both produced films, and they cooperated in distributing each other’s output.

Meschrabpom-Russ produced many of the familair Soviet classics: early on, Polikuschka and Aelita, and later the films of Pudovkin (including Mother and The End of St. Petersburg) and Boris Barnet (including Miss Mend and House on Trubnoya). Prometheus produced films highly influenced by the Soviet exports, both in terms of style and subject matter. These included Leo Mittler and Albrech V. Blum’s Jenseits der Strasse, Phil Jutzi’s Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Glück, and, mostly famously, Bertolt Brecht and Ernst Ottwald’s Kuhle Wampe oder wem gehört die Welt.

Prometheus, not surprisingly, disappeared in 1933. Meschrabpom-Russ continued until 1936.

A retrospective at the Internationale Filmfestspiele in Berlin in 2012 has occasioned a comprehensive, beautifully designed catalogue, Die rote Traumfabrik: Meschrabpom-Film und Promethueus 1921-1936. With numerous expert essays and beautifully reproduced illustrations, both in color and black and white, of posters, production photos, film frames, and documents, this is the definitive publication on the subject. Even those who don’t read German will be able to use the extensive filmography and the biographical entries on the directors and other people involved in the making of the films. The illustrations make this the perfect combination of academic study and coffee-table art book. (KT)

Closer to home, our friends have been very busy. From Leger Grindon, a deeply knowledgeable specialist in American film, comes Knockout: The Boxer and Boxing in American Cinema. The prizefight movie isn’t usually discussed as a distinct genre, but after reading this comprehensive and subtle study, you’ll likely be convinced that it’s been remarkably important. While discussing movies as famous as Raging Bull and as little-known as Iron Man (no, not that one; this one comes from 1931), Leger also introduces you to the finer points of genre criticism. The way he traces basic plot structures, key iconography, and historical patterns of change is a model of how thinking in genre terms can illuminate individual films.

Then there’s Tashlinesque: The Hollywood Comedies of Frank Tashlin. Ethan de Seife goes beyond the usual recounting of peculiar, often lewd gag moments to treat Tashlin as not only a gifted director but a representative figure in 1940s-1950s American cinema. Ethan traces how Tashlin became a program-picture director who never acquired the status of auteur, at least in the eyes of the studio system. The book situates Tashlin in the context of the Hollywood industry, both the cartoon shops (Tashlin did animation work for both Disney and Warners, among others) and the live-action production units. There’s as well a fascinating chapter on Tashlin’s influence on directors as different as Joe Dante and Jean-Luc Godard, who coined the adjective “Tashlinesque.” A blend of critical analysis, cultural commentary, and industry history, Tashlinesque is surely the definitive book on this cheerfully dirty-minded moviemaker. Ethan maintains a lively blog here.

Not strictly about cinema, but a book that’s indispensible for film researchers, is James Cortada’s History Hunting: A Guide for Fellow Adventurers. A founding member of the Irvington Way Institute, Jim is at once an IT guru, a historian of computer technology, and a scholar of Spanish history, particularly of the Civil War. History Hunting, the fruit of forty years of spelunking in archives, museums, and the world at large, is an enjoyable handbook on doing historical research. It ranges from help with genealogy (case study: the colorful Cortadas, from Spain to the US) to suggestions about how to frame a doctoral thesis. Jim reminds us that the historian must turn into an archivist: the materials you collect are documents for future historians to use. You are, to use the new buzzword, a curator. Jim provides a welter of practical suggestions along with his own tales of the hunt. Jim devotes part of a chapter to Kristin and me, which just goes to show his impeccable taste in neighbors.

Joseph McBride is known as a film historian—his biographical books on Ford, Welles, and Spielberg are scrupulous and insightful—but he also teaches screenwriting. Why not? He wrote the cult classic Rock and Roll High School. Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless is a unique manual in that it minimizes how-to instructions. Joe acknowledges the centrality of the three-act structure, but he takes a step back and asks what engages us about stories to begin with. His advice is clear-sighted. Don’t follow trends; don’t worry about “high-concept” ideas or “character arcs” or “plot points.” Closely study the masters of storytelling in fiction and drama and film, and absorb not formulas but a feeling for the flexibility of narrative technique.

Joseph McBride is known as a film historian—his biographical books on Ford, Welles, and Spielberg are scrupulous and insightful—but he also teaches screenwriting. Why not? He wrote the cult classic Rock and Roll High School. Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless is a unique manual in that it minimizes how-to instructions. Joe acknowledges the centrality of the three-act structure, but he takes a step back and asks what engages us about stories to begin with. His advice is clear-sighted. Don’t follow trends; don’t worry about “high-concept” ideas or “character arcs” or “plot points.” Closely study the masters of storytelling in fiction and drama and film, and absorb not formulas but a feeling for the flexibility of narrative technique.

One of the most original aspects of Writing in Pictures is Joe’s emphasis on adaptation. This is sensible because (a) a great many films are adapted from other sources (today, even comic books); (b) a professional screenwriter is often called upon to reshape an earlier script draft by another writer; and (c) adapting a preexisting source swiftly gets the novice screenwriter thinking about the relative strengths of verbal and visual storytelling. Joe takes us through the script-building process step by step, each time reworking London’s story “To Build a Fire.” Somewhat like the European “conservatory” approach to film education, McBride’s emphasis on organic interaction with classic traditions is something new, even radical, in the world of American screenplay education.

Then there’s Film and Risk, edited by the boundlessly prolific and enthusiastic Mette Hjort. Probably the most conceptually bold cinema book of the year, it assembles several scholars and filmmakers to assess how films and filmmakers deal with risk. The subject is of course broad. There’s risk in performance; risk in breaking stylistic boundaries; risk within film institutions (such as producing); risk in social and political contexts such as facing censorship; environmental risks, as in the costs that filmmaking exacts from the natural world; and even the risks of viewing movies—exposing yourself to horrifying or depressing stories and images. Film scholars like Hjort, Paisley Livingston, and Jinhee Choi mingle with film producers and industry observers to reflect on how cinema takes chances.

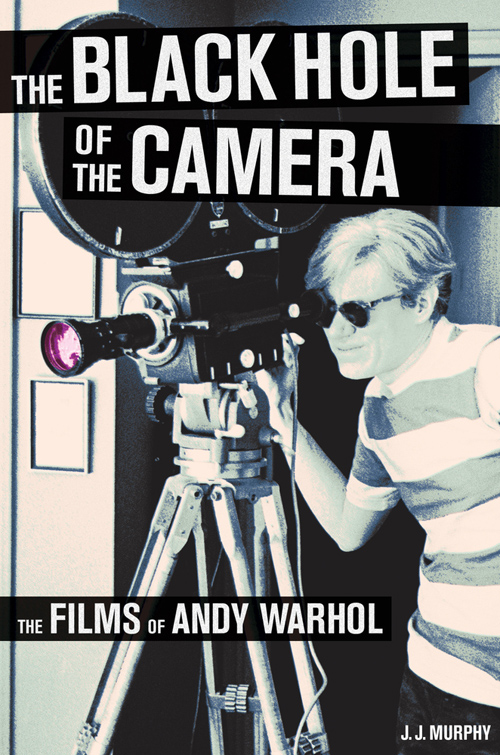

Our colleague J. J. Murphy has been researching and teaching the films of Andy Warhol for years, and today–literally, today–his monograph The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol comes out from the University of California Press. This is the most comprehensive, in-depth study of Warhol’s filmmaking that has ever been published, and of course a must-have for anyone interested in experimental film or the American art scene.

The ideas are fresh, especially the explorations of Warhol’s debt to psychodrama. At the same time, The Black Hole of the Camera clears away many misconceptions about Warhol (no, Sleep and Empire are not single-shot films) while also offering detailed information about and analysis of little-known stunners like Outer and Inner Space. There are several pages of color frames, which remind you that Warhol was as good at color as Tashlin was. JJ maintains a remarkable blog on independent cinema and is a leading figure in the Screenwriting Research Network.

Not a book, but a publication of great value: Three major researchers have collaborated on a cogent, nontechnical review of experimental investigations into film perception. All of the authors have had face time on this site. Dan Levin has executed breakthrough experiments on “change blindness”–how we miss discontinuities and anomalies in everyday life. (On another dimension, Dan’s film Filthy Theatre is coming up at our Wisconsin Film Festival.) James Cutting, a venerable figure in visual perception research, has ranged across many key areas in his consideration of cinema. He also wrote a wonderful book, available free here, on Impressionist painting. And Tim Smith, virtuoso eye-tracker, is author of one of our all-time most popular blog entries, “Watching you watch There Will Be Blood.”

With three top talents, you’d expect the collaborative paper to be a triumph of synthesis, and so it is. It supplies the best case I know for why we cinephiles should welcome psychologists who test the ways we watch movies. It should be required reading in every film theory course in the land. Access to the published paper requires a purchase or a library subscription, but you can read the preprint version here. Check in at Tim’s blog Continuity Boy for plenty of videos exploring his research (DB).

Finally, we’re sometimes asked why we don’t allow comments on our blog. The simple answer is that we’re not nearly as good at responding to comments as John Cleese is.

The cover of Joe McBride’s book pictured above is from the Faber & Faber edition, which makes a better still than the US edition from Vintage. Same good stuff inside, though.

PLANET HONG KONG 2.0 goes analog

Metade Fumaca (1999).

DB here:

In the Web age, physical books become e-books, and virtual books, often self-published, can mutate into tangible things of paper and glue. That’s what has happened to Planet Hong Kong 2.0.

The story so far: In 2011 I revised the old version. I updated the existing chapters and added four new ones. Our web tsarina Meg Hamel designed a very nice pdf version of it, with over 400 color pictures and an ingratiating layout. That is still available for $15 elsewhere this site.

I had pretty good luck with selling the e-book online, having earned enough to pay the costs of designing it. It would be nice to sell more and pay myself a little for my work. Did I mention that it’s still available for purchase here?

In the meantime, last spring I had Park Printing of Verona (Wisconsin) make some physical copies. We used high-grade paper, and the result is a very fine-looking book, measuring 11 x 8 ½ inches. I prepared them as presentation copies to the many people, particularly in Hong Kong, who had helped me in writing the 2000 edition and this one.

I’ve presented those copies to those people. I have a few copies left.

I could just hang on to them, but some people have told me they would a prefer print copy to the pdf. A few libraries have likewise expressed interest in a physical book.

So I’m making Planet Hong Kong 2nd ed. available for $60 plus postage Amazon and at Biblio. The vendor is 20th Century Books, an outstanding shop here in Madison specializing in comics, fantasy, s-f, and mysteries. (Thanks, Hank and Deb.)

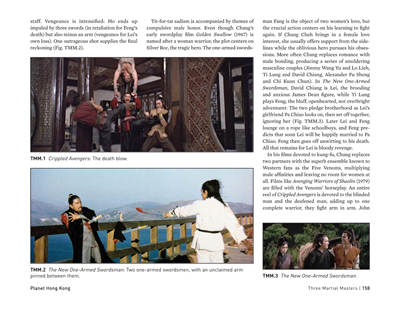

The list price of PHK 2.0 analog reflects the costs of making a small print run of a heavily illustrated book. Here are a couple of sample pages. Illustrations were scanned from 35mm frames.

If I’d had my wits about me, I’d have done this before the holidays so I could advertise it as the perfect gift for that hard-to-please film fan on your list. In any case, if you’re a reader, collector, or librarian, you can acquire a hard copy of the book from Amazon or Biblio. And the e-edition remains available on this very site. . . .

Coming up later this week: Another entry in our series, Pandora’s digital box. This one is about how digital formats have affected film festivals. It’s not a pretty tale.

The Mission (1999).

A memory palace

Roger Ebert in a moment of seriousness at Ebertfest 2006.

DB here:

Life Itself is not an ordinary memoir. True, it’s roughly chronological, taking you from Roger’s childhood through college to journalist days and then to the career we all more or less know. But from the start, we may find several moments, decades apart, squeezed into a single paragraph, even a single line. An incident in the past triggers a flashforward, an account of what became of this person, why this place became one to revisit. Later in the book, layers of flashbacks stack up. And usually the passage slips still further outward to the enveloping narrative, recounted by a man who now finds pleasure in the very act of recollection.

A trip to London in the mid-1960s, during which Roger and his old friend Dan Curley discover The Perfect London Walk, summons up an episode, years later, in which their guidebook of the same name is clutched in the hands of tourists whose paths cross with Roger and Chaz’s. Then we’re with Roger in a hospital bed years later as he revisits London in his mind, with details rising unbidden. He sees a nursery school and the shadow of a wooden palm tree in a window. And then we glide outward to another frame, the very moment of writing that conjures up all the others. “I believe that I could pause right now and remember something I saw on a walk that I have never thought of again since that time.” That moment yields another cascade of memories, ending in the 1970s with Roger crawling through a hotel window in order to look down on Pembridge Square.

Gifted with a preternatural memory, Roger shames most memoirists. Not for him the procession of big names and picturesque places that makes the usual autobiography little more than a prosed-up agenda book. The book crackles with sensory impressions: the taste of a ploughman’s lunch in a pub, the whiff of a Steak and Shake cheeseburger. The world is there to be known, in all its teeming variety. I remember talking with him after George W. Bush got elected, and he was appalled that our new President had not held a passport before being elected governor. “Can you imagine a young man being that incurious?”

Gifted with a preternatural memory, Roger shames most memoirists. Not for him the procession of big names and picturesque places that makes the usual autobiography little more than a prosed-up agenda book. The book crackles with sensory impressions: the taste of a ploughman’s lunch in a pub, the whiff of a Steak and Shake cheeseburger. The world is there to be known, in all its teeming variety. I remember talking with him after George W. Bush got elected, and he was appalled that our new President had not held a passport before being elected governor. “Can you imagine a young man being that incurious?”

Above all, Roger’s curiosity turns toward people. Vast though his appetites and energies are, and frank as he is about his faults and failures, the writer is most fascinated by a picaresque procession of extraordinary individuals, most not famous. Yes, there are portraits of Mitchum and Scorsese and Royko and other larger-than-life celebs, but they’re brought down to earth. He favors the unknowns. He has, like his beloved Dickens, a genuine interest in everybody. After telling a bit about Letterman and Leno, he really gets going on the civilians whom he and Siskel met doing man-on-the-street gags. Studs Terkel becomes a fatherly exemplar of this worldly curiosity about the absolute uniqueness of everybody. “Two people meeting with Studs standing between them would hear from him how extraordinary they both were.”

Roger’s cast consists of everyone who has provided him laughter, sober self-analysis, affection, passion, and a long-running, tuition-free course in being a good person. For Sartre’s character, Hell is other people. Ebert, I’d say, thinks that other people are a decent, secular definition of Heaven. Life Itself radiates respect for the stubborn, sometimes maddening uniqueness of human beings.

“I was born inside the movie of my life,” the book begins. Okay, but what kind of movie? As a bona fide film brat, Roger has given us the autobiographical equivalent of a 1960s off-Hollywood art picture. It recalls those exercises in broken chronology like Petulia, but it’s gentler: not grating cuts, but quick dissolves. The time frames keep shifting and flipping over. Far along, at something like the climax of the book, love affairs and alcoholism set off a spiral of associations around his mother. And each era is quickened by the observer’s awareness of the preciousness of the sensuous moment. Roger is writing and watching teenage Roger dancing with Marty McCloy to the Everly Brothers in the Tigers’ Den:

Under our armpits, sweat formed dark circles, and our cheeks were moist as they touched.

Cinematic though it is, Life Itself is a literary exercise too. Roger, perhaps our most bookish living film critic, provides a montage of styles and genres. The childhood scenes, echoing Portrait of the Artist and A Death in the Family and perhaps The Sound and the Fury, are bursts of bright, disconnected impressions. Things coalesce into anecdotes as the boy’s mind matures. (Is it just me who hears echoes of another Midwestern yarn-spinner, Jean Shepherd?) In the young man who yearns to travel, to explore every city, to read every book he can lay his hands on, to shyly move toward girls, we see Thomas Wolfe, teenage Roger’s guiding star. Soon enough, though, we’re in a Ben Hecht Chicago newsroom:

Once Paul was talking on a telephone headset, tilted back in his chair, and fell to the floor and kept on talking. Eppie [Ann Landers] reached in a file drawer and handed down her pamphlet Drinking Problem? Take This Test of Twenty Questions.

(Aspiring writers: Compose a 50-word paragraph explaining why “handed down” is a better choice than “handed him.”)

Every memoir needs a credo, and this we get in concluding chapters entitled, “How I Believe in God” and “Go Gently.” They give you much to chew over, including laconic bon mots like “I was perfectly content before I was born, and I think of death as the same state.” The lesson of this life? Expect no spoilers from a fellow critic, but I can provide a teaser. It has to do with joy.

Graven image and original: Ebertfest 2006.