Archive for the 'Books' Category

Time for a quick one: A miscellany from friends

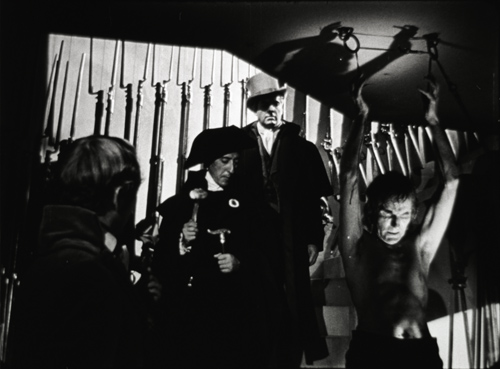

The Black Book (aka Reign of Terror).

DB here, catching up with books, videos, and events:

David Cairns has written a lively appreciation of William Cameron Menzies for the March/ April issue of The Believer. The essay bristles with rapid-fire aperçus, such as the suggestion that the great, demented Kings Row is something like the Twin Peaks of its day. David is particularly good at plotting the extent to which Menzies dominated the work of his directors. Directors without a visual style of their own, he points out, were easy for Menzies to overwhelm, but those with an already-developed signature could assimilate his contributions, as Hitchcock did in Foreign Correspondent.

David Cairns has written a lively appreciation of William Cameron Menzies for the March/ April issue of The Believer. The essay bristles with rapid-fire aperçus, such as the suggestion that the great, demented Kings Row is something like the Twin Peaks of its day. David is particularly good at plotting the extent to which Menzies dominated the work of his directors. Directors without a visual style of their own, he points out, were easy for Menzies to overwhelm, but those with an already-developed signature could assimilate his contributions, as Hitchcock did in Foreign Correspondent.

In The Black Book (aka Reign of Terror) Menzies found soul mates in two other aggressive pictorialists, Anthony Mann and John Alton, the team becoming “a crazy triangle,” eager to indulge in “thrusting gargoyle faces in fish-eye distortion, clutching shadows, and funky, teetering compositons.” Bob Cummings never looked so bizarre, before or since. I didn’t talk about this wild movie in my online Menzies material here and here because I had such poor illustrations from it. Now things have changed, and a decent, or perhaps rather indecent, sample of the film’s delirium (above) can serve to back David’s point.

David’s “Dreams of a Creative Begetter” is one of several film-related pieces in this issue of The Believer. The issue includes a DVD of the seminal People on Sunday (Menschen am Sonntag, 1930), which gathered the talents of Billy Wilder, Curt Siodmak, Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, Fred Zinnemann, and Rochus Gliese. A helpful introductory essay is at the Believer site.

Speaking of David’s writing, don’t miss his superb shot-by-shot analysis of a key scene in Gilda at his Shadowplay site, an obligatory stop for all cinephiles.

Seldom does a monograph on a single film probe so deeply as Mette Hjort’s new book on Lone Scherfig’s Italian for Beginners. It’s easy to take this movie as Dogme Lite, since compared to the earliest, rather harrowing Dogme efforts, it’s an ingratiating romantic comedy-drama. Mette does justice to this side of Scherfig’s film, but she also shows that it’s an exercise in moral seriousness. Reconstructing the production process, she conducts in-depth analysis of performance and technique. She is sensitive to actors’ moments, such as simply laying down a knife and fork; aware that these gestures are developed through improvisation, she is able to trace how each character is built up through details.

In her books and articles on the Dogme school Mette has shown that its innovations go beyond the vaunted technical “rules.” She always addresses them, of course; here she provides an illuminating typology of ways the rules have been followed or dodged. But she also stresses, as most writers don’t, that Dogme films engage with matters of political importance. For example, she has shown that The Idiots’ controversial display of “spazzing” triggered an important debate about Danish attitudes toward the disabled. In her new book Mette indicates that Scherfig’s efforts to endow her characters with the dignity to be found in everyday life offers viewers a chance “to re-connect with one of their culture’s most powerful moral commitments.” Mette talks about the project in this video.

David Gordon Green directs Your Highness; Justin Lin signs his third Fast & Furious movie. With indie filmmakers eagerly joining the tentpole and franchise business, the whole phenomenon seems due for a rethink. This makes Michael Z. Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture all the more necessary. Although I can’t be unbiased, because I served as Michael’s advisor on the dissertation that became the book, I think that any reader would find the result a fresh and vigorous exploration of the achievements of the Sundance/ Miramax generation.

David Gordon Green directs Your Highness; Justin Lin signs his third Fast & Furious movie. With indie filmmakers eagerly joining the tentpole and franchise business, the whole phenomenon seems due for a rethink. This makes Michael Z. Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture all the more necessary. Although I can’t be unbiased, because I served as Michael’s advisor on the dissertation that became the book, I think that any reader would find the result a fresh and vigorous exploration of the achievements of the Sundance/ Miramax generation.

Michael starts by looking closely at the audiences and marketing. He suggests that viewers engage with the films through particular viewing habits (e.g., “Characters are emblems”). He then shows how these habits were nourished and refined by distributors, promotion, and film festivals. The next two sections of the book consider what we might take to be the two poles of indie difference from Hollywood: greater realism, and more self-conscious artifice. The central chapters analyze realism in relation to “character-centered” filmmaking in the Indie trend. Michael turns a critical eye on characterization in films as different as Walking and Talking, Lost in Translation, and Welcome to the Dollhouse. The third batch of chapters considers the trend’s other major appeal, the sort of play with style and form we get in the Coens, Tarantino, Nolan, and others.

Michael shows how character-driven realism and gamelike artifice mesh well with the mandates of distribution and reception—how, in effect, “originality” becomes something that can be calculated and branded. The book concludes with thoughts on the evolution of the trend, comparing Happiness with Juno and raising the inevitable question: How artistically independent is independent film? Newman leaves us pondering: “Indie cinema has become Hollywood’s most prominent alternative to itself.”

One of the hallmarks of the Wisconsin program in film studies is its nuanced refusal of the art/ commerce duality that supposedly rules filmmaking. From many angles, researchers here have shown that creative impulses and business mandates mix in complicated ways, and the results are often fascinating. Indie is one example of this sort of research project, and so is another dissertation-become-book, Christopher Sieving’s Soul Searching: Black-Themed Cinema from the March on Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation. (Again, I was involved, serving on the committee chaired by Tino Balio.)

One of the hallmarks of the Wisconsin program in film studies is its nuanced refusal of the art/ commerce duality that supposedly rules filmmaking. From many angles, researchers here have shown that creative impulses and business mandates mix in complicated ways, and the results are often fascinating. Indie is one example of this sort of research project, and so is another dissertation-become-book, Christopher Sieving’s Soul Searching: Black-Themed Cinema from the March on Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation. (Again, I was involved, serving on the committee chaired by Tino Balio.)

Chris concentrates on 1960s black-themed films from A Raisin in the Sun onward, because he wants to trace how filmmakers tried out a variety of ways to represent and comment on black life. It was a transitional era, but as he puts it “because of the insights they reveal about the periods that bracket them, transitional periods are among the most fascinating and significant in all of film history.”

For Chris, Gone Are the Days (1963), The Cool World (1964), Uptight (1968), The Landlord (1970), and the unproduced Confessions of Nat Turner provide case studies of alternatives to what became the crime-and-comedy product of blaxploitation. Why did decision-makers believe that black-themed films would sell broadly enough to repay investment? What choices and compromises were necessary to “universalize” material (for white viewers) while also retaining “authentic” blackness? Or was it better simply aim the films at white liberals?

Chris tackles such questions through a painstaking study of the film industry’s efforts to find, or create, an audience for films that took great risks. Written with verve (on the screen handling of the Black Panthers, Chris talks about Hollywood’s “Black Power outage”), Soul Searching revives films that are all but forgotten and shows how their efforts to create one variety of independent cinema failed for particular social and industrial reasons.

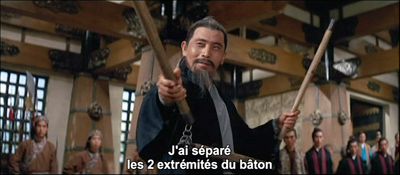

Someone I’ve been meaning to spotlight for a while: Frédéric Ambroisine is a multitalented critic, filmmaker, stuntman, and collector based in Paris. One of his careers is making supplements for French DVD releases of Hong Kong films, both classic and current. If you have even a smattering of French, you can follow his supplements with ease. He gets precious interviews with screen legends like Kara Hui Ying-hung and Ku Feng (below), master villain of the great New One-Armed Swordsman.

The videos from Wild Side often include Fred’s featurettes. You can follow Fred’s activities at actionqueens.com and alivenotdead. Much of the material in both places is in English.

Finally, if you’re in Los Angeles this week, why not visit the celebration of Orphan Films playing at UCLA 13 and 14 May? While I was in New York in February, I met NYU’s Dan Streible, moving spirit of the Orphan Films movement. Dan and his colleagues work with archives, collectors, and filmmakers to save films that fall through the cracks, digging up everything from home movies to news clips and experimental cinema. Dan curated a program of orphans at our local festival earlier this spring. At UCLA he will be a guest for screenings and discussions of many orphan titles, including the mysterious Madison Newsreel (Madison, Maine alas, not Wisconsin). Go here for Sean Savage’s discussion of the orphan oddity that has become a cult movie, and here for background on Northeast Historic Film, which found the footage.

PS: Speaking of friends, I should thank the solicitous people who wrote me during my recent illness. I appreciate your get-well notes, and I’m happy to report that I’m on the mend.

“World’s Youngest Acrobat” (Hearst Metrotone/ Fox Movietone 1929). From Orphans 7: A Film Symposium.

A new book, more or less accidental

DB here:

It’s a pleasure to announce that our book, Minding Movies: Observations on the Art, Craft, and Business of Film, has just been published by the University of Chicago Press. In some ways, it’s a conventional academic item, since it collects revised versions of published essays with postscripts updating the contents. But it’s also unusual, because those essays were published not in journals or magazines, but on the internet, on this very site. And they remain available online even as the book comes out.

Why do this? After consultation with our editor at Chicago, Rodney Powell, we thought it would be worth trying. Rodney and John Tryneski were kind enough to suggest the possibility of such a book, and the Press has been something of a pioneer in this new genre. For one thing, a collection allows us to single out and recast pieces that typify what we try to do—to explore films and filmmaking in more depth and breadth than most websites do. Moreover, the site has become vast; at the end of February we posted our 400th entry. We surmise that many readers would prefer a selection of pieces that give the flavor of our ways of thinking. Just as important, publishing a batch of web essays in book form is an experiment we agreed was worth trying. Perhaps this way our sallies would find a new audience.

Minding Movies is one more step in our exploration of the ramifications of web publishing. In less than five years, two net novices have published at least half a million words online. To my surprise, this experience has changed how I think about research, publishing, and intellectual work in general.

From the beginning, this site was something of an experiment. I wondered certain things. Was our research of interest to people outside the realm of college film studies? Could we attract that wraith, the Intelligent General Reader? Could we adapt our methods of working and writing to the medium of the Internet? Do you write differently for scrolling rather than page-flipping? Can you master an informal style after forty years of academic harrumphs?

Back at the turn of the millennium, I started a modest website consisting simply of my vitae and a programmatic statement about studying film. Later I mounted essays that supplemented my books as they were being published. The site expanded slowly, adding two or three online essays a year. In late September of 2006, in response to a suggestion by an anonymous user of our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction, we launched a blog, which we added to my original website. At first we posted every few days, but in later years we typically have written one entry every week. When we visit film festivals, the pace picks up.

We haven’t neglected the website, though. There we have republished published essays and items from out-of-print editions of Film Art. Eventually we put up the entirety of Kristin’s 1985, long-out-of-print book Exporting Entertainment. The combination of the original site and the blog gradually became a fairly monumental thing.

In part, the blog was an effort to amplify and extend the work of our textbooks, particularly Film Art. Hence the site was originally called “Observations on film art and Film Art.” But rather quickly the blog took on a life of its own. For me, as a recent retiree, it has become something of a substitute for my teaching, a way for me to try to communicate my ideas, old and new, to a receptive audience. The site, blog plus essays, functions rather like a self-published magazine, in which we can write about whatever we find curious or compelling in the world of cinema.

We found that our research has proven of interest to a surprisingly large audience. Last week, the site’s total lifetime pageloads surpassed three million. We have had nearly two million unique visitors and almost half a million returning visitors. So far this year, we’ve been very encouraged by the attention given to Kristin’s two entries on the prospects for 3-D (here and here), my entry on eye behavior in The Social Network, and above all Tim Smith’s guest blog on his eye-scanning experiments. Tim’s striking videos were downloaded, from our site and others that picked them up, over 720,000 times in ten days.

What about our working and writing methods? Could we adjust to the constraints and opportunities of the Net? Here the main arena was the blog. It began with festival communiqués from our ever-popular destination, Vancouver, but shortly it turned into something else. The occasion of a screening or lecture spiraled into a consideration of more general issues. A philosophers’ conference teased me into trying to explain some aesthetic questions that had relevance to film. The release of The Departed led me to reflect on some broader aspects of Scorsese’s career, with results that some readers took issue with.

Rather soon, however, we no longer needed the nudge of an occasion to provoke an entry. Kristin took the initiative by writing an essay about how to understand box-office figures—something that students should know but that would also be of interest to any filmgoer. Shortly occasion-based entries mingled with long-form essays on topics as varied as contemporary Danish films and first shots in movies. Sometimes the essays developed ideas we’d argued for in published work (such as my endless invocations of the idea of “intensified continuity” style), but no less often the blog encouraged me to try out new ideas. The format now seemed to me a perfectly reasonable outlet for fresh research, as with my studies of William S. Hart and a long piece on flashbacks.

The experiments continued. Most of our books rely on arguments developed through frame enlargements from particular scenes. So we learned how to illustrate our online essays with frame grabs, which yielded the bonus of color. The next step was obvious: books. The University of Michigan had already made my Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema available as a pdf. After Planet Hong Kong went out of print, I had the chance to create a wholly digital second edition. I look forward to publishing my next books as electronic editions.

In 2006 I could never have predicted the complementary developments in our online work this year. A book originally printed gets new life in digital form. Essays originally online are now available in book form. Where it all leads, we don’t know. But it looks like more fun is ahead.

KT and DB learn about kiwis in Rotorua, New Zealand, 2007.

Kristin here:

We had never created a book so quickly. Our neighbor Jim Cortada, a professional writer, calls Minding Movies a “free book” because it consists of material already published.

Of course, we had taken a lot of trouble over the entries during the preceding few years, but not with the intention of ever seeing them printed. Some we turned out quickly in response to something intriguing or silly or downright wrong that we saw on the internet. Those usually involved little more than looking up a few dates or names and coming to some conclusions about the issues involved. Others required days of research, with stacks of clippings and print-outs and piles of books with Post-its sticking out of their pages. Some entries involved the kind of intensive research that we would formerly have put into an article destined for an academic journal or anthology.

We wound up writing many entries that we didn’t think of as being as ephemeral as most web publications. The effort involved in keeping the blog going, though it happens in short bursts, does add up to a lot after four and a half years. (Collecting the many illustrations needed for some entries takes more time than the writing.)

David wants to explore the possibilities of online publishing, and I must say that having Exporting Entertainment, which was in print for a very short time, available again is satisfying. Still, if I believe something will be worth reading in years to come, I prefer hard print. So the opportunity offered by the University of Chicago Press to publish a selection from the blog was most welcome.

Choosing the entries to include wasn’t easy. Some of our most popular and substantive essays were the close film analyses. Yet those were precisely the ones which, as David says, web publication enabled us to use many illustrations. For print publication, we were more constrained, and for the most part we avoided those essays rather than publish them with only a few of their images. We selected a small number of the more heavily illustrated items: “Grandmaster Flashback,” “Unsteadicam Chronicles,” “Pausing and Chortling: A Tribute to Bob Clampett,” “Slumdogged by the Past,” and “A Welcome Basterdization.” To make up for such profligacy, we balanced those with entries that needed one or two or no illustrations.

We hope the result reflects some of the variety and range that the blog as a whole contains. One thing we discovered is that when you’re blogging, the kinds of things you’re inspired to write about far outrun the academic topics one chooses for formal articles in print. There’s also the chance to be topical in a way that the slow process of academic publishing doesn’t permit. And quite often writing for the blog can indeed be fun.

In a way we are following in the model of our friend Roger Ebert, who took to internet writing like the proverbial fish to water. Especially after the loss of his voice, he has reached an even greater and more devoted audience with his reviews and his reflective, often moving essays posted as Roger Ebert’s Journal. Roger has supported our blog enormously by linking to and/or tweeting about some of our entries. He now has supported the book by providing a more than kind blurb for the cover. The book is dedicated to him and his wife Chaz. A month from now, we look forward to blogging from the thirteenth annual Ebertfest.

For the blog goes on. Even if Minding Movies attracts favorable notice and sequels become possible, we’ll never catch up in print to what we’ve done on the internet. After all, no book is really free.

Overbooked

Reading Habits, ©Joost Swarte 1990.

DB here:

Are blog readers book readers, let alone book buyers?

I sometimes wonder. There are only so many hours in a day, and the Net is, among other things, the Celestial Magazine Rack. Day or night you can find something funny, informative, or provocative. Thanks to sites like Arts and Letters Daily, Boing Boing, and their mates, you need never run short of reading material. And if you need a full-length read, there are always e-books. Who needs print?

So I thought when we took off for NYC for the month of February. My grand experiment: To bring along no printed book that I wouldn’t discard en route or in the city. I don’t have an e-book reader of any sort. Instead, I would read only what was loaded on my laptop, including Joseph Warren Beach’s Method of Henry James. If I purchased a codex for bedtime reading (there I read on my stomach or side, so a laptop wasn’t practicable), the unlucky item would be abandoned in our rental apartment for the next occupant. Dave would travel light.

The experiment succeeded only partly. I convinced myself that I had to lug along books I needed for the blog entry on eye-scanning. So my no-book mandate was limited to recreational reading. While I was in New York, though, a visit to the Strand put too many tempting items in reach. Most of those I ransacked and left behind, except for Stanislas Dehaene’s Reading in the Brain, far too stimulating to part with, and a mystery novel to be named later. But as our departure day approached, the itch returned and I ventured to Barnes & Noble for three of the new Harper editions of Agatha Christie classics (The ABC Murders, Five Little Pigs, and Crooked House, all sturdy items). These I toted back to Madison, reading the first two on the plane.

When I got home, finding several parcels awaiting my touch, I faced facts. I had deluded myself. I am both a book person and a Net person. I like text in both formats.

I love storing webpages and pdfs for searching, but books let me savage them with markups. Yes, I know you can annotate e-books, but it’s not the same. I think highlighting is ugly. I like to draw marginal asterisks, make solid lines under key points and wiggly lines under weak or silly ones, and add faces with frowns or rolled eyes. (Though I’m not as obsessive as this guy.) So in NYC my pencil traced tattoos over Dehaene’s information and arguments. In my whodunits I more discreetly inserted question marks, exclamation points, and curses as I reacted to the plots’ feints and jabs. Now I’m stuck. Once marked up, the books can’t be abandoned; some day I might need to consult them, or at least those pages I dog-eared and defaced.

Worse, as the Joost Swarte illustration up top shows, one book leads you to an epidemic of others. That realization dawned on me back in high school, when I learned that Coleridge would go on to read every book that was mentioned in the one he’d just finished. Hypertext isn’t new; reading done right is a combinatorial explosion.

Booked for murder

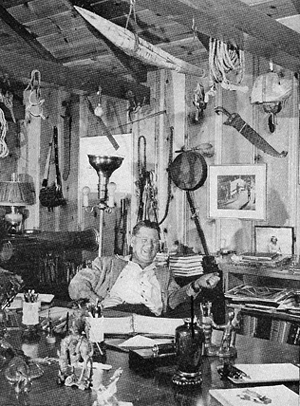

Erle Stanley Gardner.

So the Christies took me back to Robert Barnard’s A Talent to Deceive, a magnificent analysis of how Dame Agatha’s technical innovations changed the detective genre. (Creating a clue out of an apparent misprint—now that’s a tactic I can get behind.) Barnard’s book reminded me of another fine study in genre storytelling, Secrets of the World’s Best-Selling Writer by Francis L. and Roberta B. Fugate. I passed frrom The Method of Henry James to the method of Erle Stanley Gardner.

Now that we live in Harry Potter’s world, I suppose Gardner is no longer the sovereign of the best sellers. Does anyone still read Perry Mason or Doug Selby or Bertha Cool/ Donald Lam novels? But in his day, from the 1930s through the 1960s, Gardner was a central figure in US middlebrow literary culture. The Fugates’ book traces Gardner’s career, surveys the publishing scene he worked within, and compiles a great many notes on fiction techniques.

Now that we live in Harry Potter’s world, I suppose Gardner is no longer the sovereign of the best sellers. Does anyone still read Perry Mason or Doug Selby or Bertha Cool/ Donald Lam novels? But in his day, from the 1930s through the 1960s, Gardner was a central figure in US middlebrow literary culture. The Fugates’ book traces Gardner’s career, surveys the publishing scene he worked within, and compiles a great many notes on fiction techniques.

Gardner was probably the most fanatically productive and anally retentive of all mystery writers. In any month he could write a novel while turning out a hundred thousand words for the pulp magazines. He typed until his fingers bled, then he patched them with adhesive tape, and as he put it, “kept hammering.”

Typing was eventually replaced by dictation, putting Gardner in the same oral tradition as Edgar Wallace, Barbara Cartland, and Homer. By the time his first novel, the Perry Mason mystery The Case of the Velvet Claws (1933), was published he had already put his business on a rational basis. What he called his Fiction Factory employing up to seven full-time staff members. He composed all his stories himself, but his secretaries typed from his Dictaphone cylinders and kept track of characters, situations, and titles that he had used in published work, so that he could avoid repeating himself. (Shades of the bibles used for Star Wars and other sagas.) His success allowed him to buy a vast working ranch and build a compound where he and his staff could live together and maximize output.

Not that he withdrew completely from the world. The first Cool/Lam novel revealed that a California law could allow someone to get away with murder. After Gardner pointed out the loophole, the law was changed. Gardner also founded what he called the Court of Last Resort, a group of lawyers and criminologists who sought to overturn unjust convictions.

Along with pumping out fiction and crusading on legal matters, Gardner jotted copious notes to himself on story ideas, career goals, and general precepts of fiction writing. He tinkered with a “plot wheel” that would generate unexpected situations. The results do get you thinking: Locale: Wagon train. Character: Statesman. Predicament: Madness. . . Surely there’s a story there.

Dissatisfied with the wheels and gimmicks like Plot Genie and Plotto, Gardner decided to create his own machine for generating stories. The Fugates generously publish his outlines for “The Fluid or Unstatic Theory of Plots,” “Page of Actors and Victims,” “Character Components,” and so on. Some of these were synopses of discussions he would conduct with writers who were scripting the Perry Mason TV shows. They cut to the quick.

Every character in a story can and should have: 1. Point of strength; 2. Likeable or humorous weakness; 3. Prejudices; 4. Common characteristics. . . ; 5. Father, mother, other relatives dependent or wealthy; 6. Emotions—Love, hate, dislike, etc. for other characters; 7. Problems—And this is where you sell the character to the reader.

Gardner’s search for formulas led him to spell out, with unusual explicitness, the conventions of the form he worked with. (In this he intersects with those of us interested in poetics of media.) I would think that aspiring writers of fiction or movies could learn a lot from Gardner’s thoughts on craft.

If you’re interested in mystery plots, his ideas about the “murderer’s ladder” and “clue sequences” might provoke some ideas. He emphasized plotting a mystery from the criminal’s point of view, not from the investigator’s: It made for less contrivance. Consider as well Gardner’s notion of the “three-ring circus” plot. Take three conventional situations, he suggested, then hook them together in ingenious ways. The film example that occurred to me was the network narrative, which weaves several protagonists’ stories together. Pulp Fiction folds together a hitman story, a prizefighter story, a robbery story, and a few others to create something that felt fresh.

Gardner was a pack rat. The Fugates’ book could be very inclusive because his collection, donated to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, ran to over 36 million items. Among the memorabilia were Gardner’s notes on a book to which I often refer in lectures, J. Berg Esenwein and Arthur Leeds’ 1913 manual Writing the Photoplay. From Secrets I learned as well of two other books on popular plotting I needed to read, if not buy. I’m not saying what they are; you might beat me to them. Book information sometimes wants not to be free.

Crime on the set

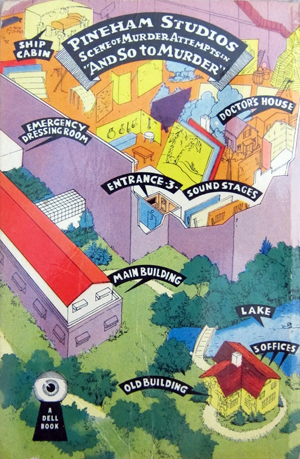

Why the old books? Why not Franzen’s Freedom? When it comes to fiction, more and more I’d rather read books I’ve read before instead of trying new things. Reader’s comfort food, I suppose; or at least the adolescent window. So at the Strand a 1947 mapback edition of Carter Dickson’s And So to Murder (1940) practically wriggled its way into my hand, like a cat begging to be stroked.

Carter Dickson was a pseudonym of the endlessly inventive John Dickson Carr, who throughout the 1930s and 1940s reliably turned out many detective novels and short stories. The Dickson ones feature Sir Henry Merrivale, a short, balding, profane doctor-barrister-baronet who is usually at the center of confusion. He once “sorta hit a cow with a train.”

The Old Man, as H.M. is known, enters And So to Murder rather late. The bulk of the action is occupied with a string of attempted killings during the preparation of a movie. It had been axiomatic in Golden Age detective stories that only homicide could justify a book-length tale, but here a tumble of conspiracies and Nazi espionage fill out the plot. There are as well the usual Carr chapter-endings, which unashamedly break off at points of high tension.

Experts rate And So to Murder not as highly as other Carr/ Dickson classics, although I find that several of my favorites, including gems like The Reader Is Warned (1939) and the short story “The House in Goblin Wood,” don’t score high numbers either. Of course all agree on the excellence of The Judas Window (1938), a virtuoso performance.

A cinephile can hardly resist the premise of my mapback. Monica Stanton, an unworldly provincial, writes a steamy novel called Desire. When it becomes a bestseller, Albion Films hires her as a screenwriter, but not in order to adapt her novel. Instead, she has to adapt And So to Murder, the novel by a handsome but deplorably bearded mystery writer, Bill Cartwright. Bill, of course, is assigned to adapt Desire. As flirtation and squabbling develop and a tough Hollywood screenwriter arrives to punch up the projects, Monica is threatened with poisoned cigarettes and sulfuric acid.

Carr novels like The Burning Court (1937) and The Crooked Hinge (1938, a masterpiece) carry a whiff of horror and brimstone, but the Dickson efforts are largely comedies. Like many Golden Age authors, Carr yoked his mystery to a developing romance, and his Dickson plots often treat the couple disrespectfully, showing how male vanity and female obstinacy create perpetual misunderstandings. His women, who typically wear no make-up, are smart and impertinent, and his men are clumsily chivalrous in their efforts to woo them.

And So to Murder is a good example of the sexual rivalry. Monica, barred from joining Bill at the War Office, decides to pay him back by plunging into the sordid side of London (short of visiting Soho) and picking up the first man she meets.

Bill Cartwright had done that deliberately, of course, to humiliate her. He had known all along that she would never be allowed into the War Office.

Her mind dwelt with hatred on the picture of Bill as he probably was now. He would be sitting in a spacious office, all mahogany and deep carpets, with bronze busts on bookcases, and an Adam fireplace. He would be drinking whiskey-and-soda—Monica herself, when she reached the Café Royal, was going to have absinthe—and listening to some thrilling anecdote of the Secret Service, told by a tall gray man with a deep voice, who sat at a desk with his back to the Adam fireplace.

Every film-goer knows that this is a true picture of the Military Intelligence Department, and Monica decorated it until pukka sahibs abounded.

It is, of course, a setting straight out of a 1930s film. Carr cleverly gives his heroine a fantasy suitable for her movie-struck imagination. Here’s one screenwriter who really believes the myths the studios spawn.

It is, of course, a setting straight out of a 1930s film. Carr cleverly gives his heroine a fantasy suitable for her movie-struck imagination. Here’s one screenwriter who really believes the myths the studios spawn.

The romance fulfills another purpose: it is a decoy. Carr fills out Bill’s and Monica’s embroglios with lively action, crisp descriptions, flashbacks, and fancies like the one just mentioned. Only later do you find that the smooth surface cunningly glides us toward quick reading, so that we’ll pass over hints that are ultimately of great importance. Carr was a connoisseur of magic, and although he could sometimes dwell on his clues, demanding that we puzzle them out, he was also skilled in the conjuror’s art of misdirection.

Carr’s affectionate mockery of stars, directors, producers, scenarists, and the down-at-heel British film industry holds up well. The plot centers on missing footage, and there are clues involving props and practical sets, along with a running gag about a coarse American mogul who keeps demanding big battle scenes filled with historical anachronisms.

There is no snobbery in this satire of moviemakers, only the zesty teasing that Carr aimed at aristocracy, pomposity, and pretension (especially when displayed by characters from the Continent). Although he was a deep-dyed Anglophile, Carr retained a vigorous American impatience with ceremony and circumlocution. At the same time, he could be serious about the gathering threat to his beloved Britain.

This was on Wednesday, the 23rd of August. Before a fortnight had elapsed there was a new noise in the earth. The dozenth pledge was broken; the gray mass burst loose; over London the sirens roared as the Prime Minister finished speaking; the great concrete hats of the Maginot Line revolved, and looked toward the West; Poland died, with all her guns still ablaze; the nights of the blackout came; and at Pineham, a small spot in England, a patient murderer struck again at Monica Stanton.

The passage ends with a typical Carr dodge (there will be no murder, so no murderer), but the lead-up has that rumble of thunder and kettledrums he could summon as occasion demanded. Still, the comic tone eventually wins out. The last line of the book is “It’s just one of the things that happen in the film business.”

The standard biography of Christie is Janet Morgan’s Agatha Christie. The recent Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks is not to my mind as illuminating as it might be. On Gardner, the unabashed puff piece by Alva Johnston, The Case of Erle Stanley Gardner, offers some insights. The only biography of Carr is Douglas Greene’s John Dickson Carr: The Man Who Explained Miracles. See also S. T. Joshi’s John Dickson Carr: A Critical Study. Old as it is, Howard Haycraft’s anthology, The Art of the Mystery Story, remains an excellent general source.

Thanks to Stef Franck and Gabrielle Claes for help with a Dutch translation.

To read the Readers’ Bill of Rights for Digital Books, go here. Image by Nina Paley, whom Kristin and Richard Leskovsky interviewed here.

PS 14 March: Jon Jermey kindly alerted me to the lively website he moderates on Golden Age Detective Fiction. It’s full of information and expert opinion, including Mike Grost’s overviews of John Dickson Carr’s works and Erle Stanley Gardner’s plotting tactics. Thanks to Jon for letting me know.

From books to blogs to books

Kristin here:

This is a follow-up to David’s latest entry on the supposed death of film criticism.

![]() As academics rather than reviewers, we’ve tried to take advantage of the benefits offered by the Internet. In our pre-blogging days, David used his website to post articles. They came out faster than they would if submitted to a print journal, and they would reach a larger audience, at least in the short run. When we added a blog to the site, it became, as David wrote, “our own magazine.”

As academics rather than reviewers, we’ve tried to take advantage of the benefits offered by the Internet. In our pre-blogging days, David used his website to post articles. They came out faster than they would if submitted to a print journal, and they would reach a larger audience, at least in the short run. When we added a blog to the site, it became, as David wrote, “our own magazine.”

For a while putting a lot of entries no place but on the blog seemed fine. Our stat-counter tells us that a lot of the older entries get read. Either a teacher assigns them or someone finds an old link or discovers the blog for the first time through a new entry and then clicks around on a lot of the older pages. So it’s not as though the pieces disappear a few weeks or so after they’re written. The blog has become a large resource by now.

But what about the really long run? I tend to want to see my prose in print. It’s unlikely that the blog will completely crash, but what if it did happen? And what becomes of all the material on the blog in the distant (I hope) future when we’re not around to keep an eye on it?

Ironically, the internet has proved to be a good way of extending the life of our print books. David’s Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema went out of print, and now it’s online, improved with better pictures, many in color. My Exporting Entertainment was in print for such a short time that few knew I had written it; now it has found a home on the website. Now Planet Hong Kong is out of print as well. David plans to update it and post the new version on the website as well.

Ironically, just as we were contemplating the migration of our books from print to pixels, Rodney Powell, of the University of Chicago Press, inquired as to whether we would be interested in turning a selection of our blog entries into a book. It wouldn’t be necessary to take down the original entries, he assured us. We couldn’t have done that anyway, since our textbook Film Art has just added a feature that alerts teachers and students to relevant essays via URLs in the margins. But we agreed to such a collection, and we’ve just sent in the manuscript for copy-editing. The result, called Minding Movies, should be out next spring.

There hasn’t exactly been a stampede to collect blog entries as books, but some presses, including Chicago, are trying out this new genre. Profile Books has just published classicist Mary Beard’s It’s a Don’s Life, based on her blog of the same name. (I highly recommend her book, The Fires of Vesuvius.) Economists Gary S. Becker and Richard A. Posner’s Uncommon Sense (also the University of Chicago Press) culls items from The Becker-Posner Blog.

Apart from blog-based books, the University of Chicago Press has some more traditional books of film criticism in press. One is a collection of Dave Kehr’s reviews from his days with the Chicago Reader (1974-1986). In September it will also publish a book gathering writings by Jonathan Rosenbaum (some of which have also been posted on his website) called Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition. Chicago has announced a third volume of Roger Ebert’s Great Movies for October of this year. Although some of these pieces have been posted on the authors’ websites after their initial print publication, Minding Movies is unusual in that its entire contents, like those of the Becker-Posner book, were written designedly for the Internet.

Will people want books of blog material that’s available for free online? From our standpoint it seems odd. True, some people just don’t like reading anything longer than a few paragraphs on a computer screen. But choosing the entries to put into the book made us realize how big the blog has become over three and a half years. It’s not easy to just browse through.

This entry marks post number 320 on Observations on Film Art. We were able to include 31 of that total in the book, which will be around 96,000 words. The inescapable conclusion is that we have posted ten volumes’ worth of stuff on the blog. Whew!

Not that we would want to put everything on Observations on Film Art into print. There are a lot of relatively topical items like festival coverage and reports on lectures and conferences and DVD supplements. My piece on the “I Drink Your Milkshake” phenomenon brought us our single busiest day ever (over 20,000 page loads), but it dealt with a fad and certainly doesn’t deserve to go between the covers of a book. Still, quite a few of the entries do reflect research and analysis of the sort that we would ordinarily put into our articles.

Even before it ever occurred to us that we could put together a blog collection, colleagues had said, “Your stuff deserves to be published as a book.” Maybe that’s a sign of the lingering sense that print publication is still more serious than blogging. Another implication seems to be that, while pieces written to be posted online may be excellent and worthy of publication in any format, they also need to be rescued from the vastness that is the Internet. Yes, Google can help people find David’s entry on staging in There Will Be Blood in a flash. But if the reader doesn’t have any particular film or other specific topic in mind and just wants to see our best pieces, it’s not that easy.

Incidentally, “Hands (and faces) across the Table,” the There Will Be Blood piece, won’t be in the book. It contains too many pictures, which becomes more of a concern in print. There will be a few of the heavily illustrated entries in the book, but we had to balance those with others that don’t depend on images.

Whether books based on film and other media-related blogs will become a lasting genre has yet to be seen. Perhaps after a period of adjustment to the Internet as a venue for film criticism, we will return to the practice of the 1960s and 1970s, when Andrew Sarris, Pauline Kael, and other critics routinely saw their material collected as books. We might end up concluding that the Internet has not harmed books in the way that it has some newspapers and magazines.

If blog-based books do catch on, they will provide further counter-evidence to the notion that film criticism is dying out. If they don’t, the failure won’t prove that film criticism is dead, only that now it probably flourishes best online.

[March 22: Coincidentally, TV historian and critic Jason Mittell posted a related entry on his blog today. It’s entitled “Why a Book?” and ponders the pros and cons of publishing a scholarly book or putting the same material online. The piece doesn’t deal with the idea of a book collecting blog entries, but it touches on factors like long-range availability.]