Archive for the 'Books' Category

The postman has rung more than twice

Optical Vacuum.

DB here:

While I try to whip up seven lectures for the Bruges Summer Film College and a couple more for the University of Copenhagen and our June Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image confab, I offer some quick notes on notable DVDs and books lugged to our door by our mailman.

When machines film better than they know

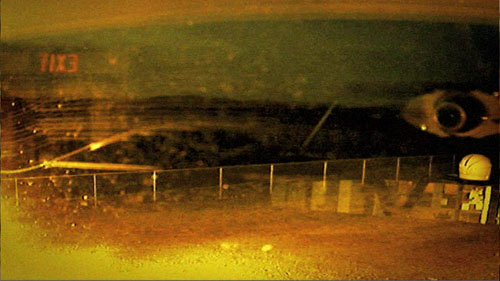

Snow blankets a terrace and the furniture on it. A bottle jerks back and forth on a pavement. Christmas lights blink on and off. Everything looks desolate. What people we see scuttle across washed-out landscapes, play mahjongg in stammering gestures, and toil in computer labs under glaring fluorescent lights. What planet are we on?

These images are available to any of us. For two years Dariusz Kowalski trawled through sites like www.opentopia.com for surveillance-camera footage. He chose only material from hidden cameras. He added nothing except some slow motion (“otherwise it would be too fast”) and a voice-over commentary from artist Stephen Mathewson reading passages from a year’s diary. The result was a fifty-five minute assemblage film called Optical Vacuum (2008), which I saw and admired in Hong Kong back in April.

Sometimes the diary account intersects with what we see: Mathewson talks of washing his laundry/ shots of a Laundromat. More often, the voice drifts off on its own. Optical Vacuum isn’t an effort to make a film essay or to create a complex audiovisual dynamic. Mathewson’s diary provides an intimacy that the footage lacks, but I think the film would stand up strongly without it.

As a flow of impersonal views, usually from a distant perch, the footage creates a bleak beauty.

Occasionally a human operator has commanded the camera to focus on something, usually a woman.

But most often the camera is just mindlessly recording.

In the process, the surveillance camera reinvents avant-garde film—not just the barely inflected fields of Structural cinema, but also the time compression and melting glimpses, the reflections and superimpositions, the transient ghosts and brutal geometry we find in silent experimental work by Richter, Vertov, and others. These stupid cameras can’t help turning reality into something else. They don’t know any better.

Optical Vacuum, along with other pieces by Kowalski, can be found on a PAL uncoded DVD from the extraordinary Austrian collective sixpack. The handsomely mounted Index release is available here, and elsewhere on the Net.

Dragons and tigers in the Udine sun

Italian festivals of specialized cinema are mounted with incomparable flair–lots of screenings, panels, interviews, book sales, and of course outstanding food. Most famous are Pordenone’s festival of silent cinema and Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato. But for admirers of Asian cinema, just as important is the Udine Far East Film event, which completed its eleventh installment on 2 May.

Italian festivals of specialized cinema are mounted with incomparable flair–lots of screenings, panels, interviews, book sales, and of course outstanding food. Most famous are Pordenone’s festival of silent cinema and Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato. But for admirers of Asian cinema, just as important is the Udine Far East Film event, which completed its eleventh installment on 2 May.

Alas, I’ve never been. In its earliest years it overlapped with the Hong Kong film festival; more recently, my commitments elsewhere, such as Ebertfest, have kept me away. But I have followed this celebration of Asian cinema at a distance through its remarkable publications.

The Udine event concentrates on popular cinema, mostly recent releases that are unlikely to come to US theatres or video stores. You can see films from Japan, Korea, and China but also from Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines. This year’s highlights include regional hits like Cape no. 7, Beast Stalker, Departures, and Ip Man as well as obscure and delirious items like Love Exposure and The Forbidden Legend: Sex and Chopsticks. Many screenings are European premieres.

The programmers also mount adventurous retrospectives of rare items. One year it was a survey of the work of Patrick Tam, still too little known among Asian aficionados. This year the retrospective was devoted to Ann Hui’s TV films, which are among her best work. These films, shot in 16mm and broadcast in the 1970s, were strong meat for a culture unused to social criticism in its popular media. Hui’s dramas showed police corruption, the sex trade, abandoned children, and drug addiction. The episodes were researched and scripted under great time pressure, and Hui was allotted two weeks for shooting and post-production. “We were experts at shooting in the streets on the sly.” The stories’ concern for ordinary people and their problems has resurfaced again in The Way We Are (2008) and Night and Fog (2009).

The Hui volume is a model of the profuse documentation the Far East festival provides. Several concise essays, all in both English and Italian, enhance appreciation of the films. Contributors Law Kar, Shu Kei, and editor Tim Youngs do a fine job of situating Hui’s TV work in its context, and a lengthy interview with the director explores her working methods and intentions. There’s also valuable filmographic information about the episodes (four of them available on DVD).

The Hui volume is a model of the profuse documentation the Far East festival provides. Several concise essays, all in both English and Italian, enhance appreciation of the films. Contributors Law Kar, Shu Kei, and editor Tim Youngs do a fine job of situating Hui’s TV work in its context, and a lengthy interview with the director explores her working methods and intentions. There’s also valuable filmographic information about the episodes (four of them available on DVD).

As if this weren’t enough, the Udine event publishes a mammoth catalogue called Nickelodeon. Each year it’s a treasure chest of enthusiastically presented information. This time around, surveys of 2008 developments in all the major countries are accompanied by Roger Garcia‘s special section on the history of Thai action cinema. A vast section of reviews of the films to be shown rounds out this gift to the Asian cinephile. (A little of this material is available at the Udine site.) There is no coordinated effort to sell the books to the public, but if you want to purchase them, try writing to the festival directors at cec@cecudine.org.

So a tip of the hat to the dedicated Udine team, headed by Sabrina Baracetti, and a signal to you that if you have the time and the money to go, you would surely have a hell of a week. (Note that professors and students are offered lodging for some nights.) Who knows? A director might show up to put the audience in a movie, as Johnnie To once did. Even if you can’t make the trip, the quality of the publications makes them indispensible for research and enjoyable reading.

Rabbits from a hat

It’s tiresome to hear novelists kvetching that film adaptations mangle their work. So it’s a pleasure to read Christopher Priest’s brisk account of how his novel The Prestige became a film. In The Magic: The Story of a Film Priest takes us through the whole process, but this isn’t the usual behind-the-scenes tour. He never visited the set or met the principals. Instead we get the viewpoint of a writer living in East Sussex, following the production through agents’ correspondence and the gossip frothing up on Google Alerts.

It’s tiresome to hear novelists kvetching that film adaptations mangle their work. So it’s a pleasure to read Christopher Priest’s brisk account of how his novel The Prestige became a film. In The Magic: The Story of a Film Priest takes us through the whole process, but this isn’t the usual behind-the-scenes tour. He never visited the set or met the principals. Instead we get the viewpoint of a writer living in East Sussex, following the production through agents’ correspondence and the gossip frothing up on Google Alerts.

Priest is a lively writer, and he is frank about the ups and downs of the process. Initially he is happy that Nolan acquired the rights because the novel, a cunningly designed piece of misdirection, seems ideal for the director of Memento. But he confesses disappointment when the Prestige project is sidetracked by Batman Begins (“overlong, simplistic, and dull”). When the production gets under way, there are more swerves in the road. Given an early script, Priest admires the craftsmanship of Jonathan Nolan. But then he’s baffled that Christopher Nolan is saying two inconsistent things: that the film is completely different from the book, and that reading the book will spoil the film. Then again, during a press preview in Leicester Square, Priest succumbs to the film’s intricacies. “It has one of the most complicated and sophisticated narrative structures ever seen in an entertainment film.”

The story of the production ends here, but Priest goes on for about fifty pages to analyze the film in considerable detail. He dwells on the opening, which has no equivalent in his novel, and praises it for its fluent shifts among different points in story time. He appraises various aspects of the film, and he doesn’t stint criticisms. He notes that the Nolans stripped off his contemporary story, crucially altered the roles of the women, and turned his elusive mysteries into plot-driven secrets. Yet he concludes:

There is hardly a line of dialogue or moment of action in the film that can be traced back word-for-word, yet the whole thing is faithful to the novel in spirit, in story and in effect. I have differences with the screenplay in places, but none of those detracts from my general impression that it is a classic film adaptation of an existing novel, one which intending screenwriters would do well to study alongside the novel. (157).

Priest is a former movie critic (for the sturdy old British Film Institute publication Film) and an astute observer of what happens in a shot and on a soundtrack. He contacted me after my March blog entry discussing micro-repetitions in The Prestige and told me of The Magic. I ordered a copy pronto, and I’m glad I did. If you want to give your mail carrier a bit more job security, go to this page and click on GrimGrin Studio.

Books, an essential part of any stimulus plan

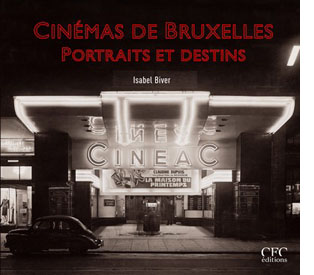

The Pathé Palace theatre, Brussels, designed by Paul Hamesse.

DB here:

Some shamefully brief notes on new publications. Disclaimer: All are by friends. Modified disclaimer: I have excellent taste in friends.

You call me reductive like that’s a bad thing

It’s easy to see why we might tell each other factual stories. We have an appetite for information, and knowing more stuff helps us cope with the social and natural world. We can also imagine why people tell fictitious stories that we think are true. Liars want to gain power by creating false beliefs in others. But now comes the puzzle. Why do we spend so much of our time telling one another stories that neither side believes?

Brian Boyd’s On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction (Harvard University Press) is the first comprehensive study of how the evolution of humans as a social, adaptively flexible species has shaped our propensity for fictional narrative. The book is a real blockbuster, making use of a huge range of findings in the social and biological sciences. Brian paints a plausible picture, I believe, of the sources of storytelling. Along the way he shows how two specimens of fiction, The Odyssey and Horton Hears a Who, exemplify the richness and value of make-believe stories.

Brian Boyd’s On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction (Harvard University Press) is the first comprehensive study of how the evolution of humans as a social, adaptively flexible species has shaped our propensity for fictional narrative. The book is a real blockbuster, making use of a huge range of findings in the social and biological sciences. Brian paints a plausible picture, I believe, of the sources of storytelling. Along the way he shows how two specimens of fiction, The Odyssey and Horton Hears a Who, exemplify the richness and value of make-believe stories.

The standard objection to an evolutionary approach to art is that it’s reductive. It supposedly robs an individual artwork of its unique flavor, or it boils art-making down to something it isn’t, something blindly biological. Art is supposed to be really, really special. We want it to be far removed from primate hierarchies, mating behavior, or gossip. For a typical criticism along these lines, see this review of Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct. Brian has already adroitly responded to this sort of complaint here. See also Joseph Carroll’s examination of reductivism on his site.

It seems to me that all worthwhile explanations are reductive in some way. They simplify and idealize the phenomenon (usually known as “messy reality”) by highlighting certain causes and functions. This doesn’t make such explanations inherently wrong, since some questions can be plausibly answered in such terms. For example, often the literary theorist is asking questions about regularities, those patterns that emerge across a variety of texts. That question already indicates that the researcher isn’t trying to capture reality in all its cacophony. (For me, it’s all about the questions.)

Literary humanists sometimes talk as if they want explanations to be as complex as the thing being explained. But that would be like asking for the map to be as detailed as the territory. In fact, however, humanists tacitly recognize that explanations can’t capture every twitch and bump of the phenomenon. Consider some types of explanations that are common in the humanities: Culture made this happen. Race/ class/ gender / all the above caused that. Whatever the usefulness of these constructs, it’s hard to claim that they’re not “reductive”—that is to say, selective, idealized, and more abstract than the movie or novel being examined. Likewise, when people decry evolutionary aesthetics for its “universalist” impulse, I want to ask: Don’t many academics take culture or the social construction of gender to be universals?

I want to write more about Brian’s remarkable book when I talk about our annual convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. For now, I’ll just quote Steven Pinker’s praise for On the Origin of Stories: “This is an insightful, erudite, and thoroughly original work. Aside from illuminating the human love of fiction, it proves that consilience between the humanities and sciences can enrich both fields of knowledge.”

Faded beauties of Belgium

In its day, Brussels played host to some fabulous picture palaces. Now after years of research Isabel Biver has given us a deluxe book, Cinémas de Bruxelles: Portraits et destins. It’s the most comprehensive volume I know on any city’s cinemas.

Isabel glides backward from contemporary multiplexes and tiny repertory houses to the grandeur of the picture palaces. The Eldorado was a blend of Art Deco style and quasi-African motifs sculpted in stucco. King Albert graced the opening in 1933. There was the Variétés, a multi-purpose house built in 1937. It had rotating stages, air conditioning, and space for nearly 2000 souls (cut back to a thousand when Cinerama was installed). It was, Isabel claims, the first movie house in the world to be lit entirely by neon.

Isabel glides backward from contemporary multiplexes and tiny repertory houses to the grandeur of the picture palaces. The Eldorado was a blend of Art Deco style and quasi-African motifs sculpted in stucco. King Albert graced the opening in 1933. There was the Variétés, a multi-purpose house built in 1937. It had rotating stages, air conditioning, and space for nearly 2000 souls (cut back to a thousand when Cinerama was installed). It was, Isabel claims, the first movie house in the world to be lit entirely by neon.

Then there was the Pathé Palace, shown at the top of this entry. Dating back to 1913, it boasted 2500 places and included cafes and even a garden. This imposing Art Nouveau building was designed by Paul Hamesse, probably the city’s most inspired theatre architect. Hamesse also created the Agora Palace, which opened in 1922. Huge (nearly 3000 seats), the Agora was one of the most luxurious film theatres in Europe.

And we can’t forget the Métropole, the very incarnation of the modern style. Sinuous in its Art Deco lines, it packed in 3000 viewers. When it opened in 1932, it attracted nearly 53,000 spectators during its first week. The neon on the Métropole’s façade lit up the night, and its two-tiered glassed-in mezzanine became as much a spectacle as the films inside. See the still at the bottom of this earlier entry of mine. A ghost of its former self still sits on the Rue Neuve. Local historians consider the failure to preserve the Métropole a scandal in the city’s architectural history.

Cinémas de Bruxelles is a model presentation of local theatres. Not only does it trace the history of the major houses, but it includes a glossary of terms, a large bibliography, and an index of all theatres, both central and suburban. Needless to say, it is gorgeously illustrated. Whether or not you read French, I think you would enjoy this book, for it evokes an age we’re all nostalgic for, even if we didn’t live through it.

A TV interview with Isabel in French is here, with glimpses of what remains of the Métropole. She also gives guided tours of the remaining cinemas in the city center and in the neighborhoods. More information here.

A guy named Joe

Tropical Malady.

It’s seldom that a young filmmaker gets a hefty book devoted to him. Apichatpong Weerasethakul (aka Joe) will turn forty next year. He comes from Thailand, not a country adept at negotiating world film culture, and he is known chiefly for only four features. Yet he has become one of the most admired filmmakers on the festival circuit. His films are apparently very simple, usually built on parallel narratives. They have a relaxed tempo, exploiting long takes, often shot from a fixed vantage point, and scenes whose story points emerge very gradually. Joe’s movies tease your imagination while captivating your eyes. Each one could earn the title of his first feature: Mysterious Object at Noon.

It’s appropriate, then, that the tireless Austrian Film Museum has published a lavish collection of critical studies. Edited by James Quandt, the anthology arrives along with a massive retrospective of the director’s work, which includes many short documentaries and occasional pieces.

It’s appropriate, then, that the tireless Austrian Film Museum has published a lavish collection of critical studies. Edited by James Quandt, the anthology arrives along with a massive retrospective of the director’s work, which includes many short documentaries and occasional pieces.

James’ introductory essay, as evocative and eloquent as usual, is virtually a monograph, discussing all the features in depth. Alongside it are discerning essays by other old hands. Tony Rayns offers his usual incisive observations, focusing largely on Joe’s short films and the recurring imagery of hospitals, while Benedict Anderson surveys the Thai reception of Tropical Malady. Karen Newman offers precious information and judgments about Joe’s installations. The director himself signs several essays and participates in interviews and exchanges. Even Tilda Swinton has something to say.

I remember when Mysterious Object at Noon played the Brussels festival Cinédécouvertes in 2000. I was baffled. Joe’s movies taught me to watch them, and finally with Syndromes and a Century I got in sync. Its austere lyricism, off-center humor, and patiently unfolding echoes win me over every time I see it. (You can search this blogsite for several mentions, but JJ Murphy has a fuller appreciation of Syndromes here.) Thanks to Alexander Horwath and his colleagues for making this wonderful anthology, decked out with color stills and rich bibliography and filmography, available to us—and in English.

Zap goes the Chazen

Zap, Snarf, Subvert, Young Lust, Tits & Clits, Air Pirates Funnies, Slow Death Funnies, Feds ‘n’ Heads, Corn Fed Comics, Dope Comix, Cocaine Comix, Corporate Crime Comics: The names define the era. The sixties didn’t end until the mid-1970s, and these outrageous cartoon books really came into their own after the election of Nixon in 1968.

On 2 May, the Chazen Museum on our campus launches its exhibition, Underground Classics: The Transformation of Comics into Comix, 1963-1990. A whirlwind of events, including films and lectures, will revolve around galleries full of imagery from the demented pens of Kim Deitch, Aline Kominsky Crumb, Trina Robbins, Gilbert Shelton, Robert Crumb, Bill Griffith, and many other cartoonists.

The show was originated by Jim Danky, a scholar of public media from our State Historical Society, and Denis Kitchen, comic artist and the publisher of Kitchen Sink Press here in Wisconsin. Jim has long argued for the archival value of minority and subcultural publications. He started our Center for Print Culture and has been an advocate for gathering print materials by and for children, women, and ethnic minorities. He virtually created the area of “alternative library journalism”—collecting obscure publications from all zones of the political spectrum. I recall his satisfaction in telling me that he had managed to acquire a collection of The War Is Now!, the radical Catholic newsletter published by Hutton Gibson, father of Mel.

The show was originated by Jim Danky, a scholar of public media from our State Historical Society, and Denis Kitchen, comic artist and the publisher of Kitchen Sink Press here in Wisconsin. Jim has long argued for the archival value of minority and subcultural publications. He started our Center for Print Culture and has been an advocate for gathering print materials by and for children, women, and ethnic minorities. He virtually created the area of “alternative library journalism”—collecting obscure publications from all zones of the political spectrum. I recall his satisfaction in telling me that he had managed to acquire a collection of The War Is Now!, the radical Catholic newsletter published by Hutton Gibson, father of Mel.

For some years Jim has been telling me about his efforts to mount the comix show. It’s no small matter to collect this elusive material and then persuade a museum to show it. Not too many galleries feature talking penises, Jesus visiting a faculty party, or Mickey and Minnie robbed at gunpoint by a dope dealer. Maybe we forget, in the age of the Web and The Onion, just how scabrous these things looked forty years ago. Actually, they still look scabrous. They also look pretty funny, and they’re often well-drawn. As a historical codicil, the exhibition includes 1980s images from artists extending the tradition, such as Drew Friedman and Charles Burns.

The show runs until 12 July 2009. If you can’t get to town, there’s the splendid catalogue. It includes essays by Jim and Denis, Jay Lynch, Patrick Rosenkranz, Trina Robbins, and Paul Buhle. There are free screenings of Fritz the Cat and Crumb at our Cinematheque. And you can read an interview with Jim about the show here.

Remember our motto: Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun.

Up next: Days and nights at Ebertfest.

The Eldorado Cinema, Brussels, designed by Marcel Chabot.

Around the world in 750 pages

The Double Life of Véronique (1992).

DB here:

Just over twenty years ago Kristin and I embarked on a perilous task. We decided to write a synoptic history of world cinema.

The task wasn’t perilous because it was innovative. Since the 1930s, there has been no shortage of historical surveys of international filmmaking, and such items continue to be published. But when we decided on this project in 1987, we wanted something different.

Soon that book will appear in a third edition. We take this occasion to explain the whys and wherefores.

Just start over

Daisies (1966).

For a very long time, and sometimes still, film histories written by Americans took a very partial look at the phenomenon of cinema. For one thing, they tended to focus on a series of masterpieces, films that had been deemed important within a narrow canon. The earliest lineup went pretty much this way: Lumière films, Méliès’ Trip to the Moon, Porter’s Great Train Robbery, Griffith’s Birth of a Nation and/ or Intolerance. Then came national schools, such as German Expressionism (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), Soviet Montage (Battleship Potemkin), and Continental Dada and Surrealism (Entr’acte, The Andalusian Dog). Early sound was M and Sous les toits de Paris and maybe Love Me Tonight. The 1940s was Grapes of Wrath and Citizen Kane and Enfants du Paradis and Italian Neorealism. And so on.

But in the 1970s archivists began opening their doors to researchers. Thanks to wider and deeper viewing, new film historians, young and old, were questioning the canon. André Gaudreault and Charles Musser showed that Porter’s Life of an American Fireman, which supposedly gave birth to crosscutting, did not do so; in fact the version people had used for years was a re-cut print! In Jay Leyda’s seminars at NYU, young scholars like Roberta Pearson were tracing what Griffith actually did and didn’t do, a task taken up by Joyce Jesionowski as well. At the same time, Eileen Bowser, Tom Gunning, Noël Burch, and others began questioning the idea that “our cinema” developed step by step from “primitive” beginnings. In England, Ben Brewster, Barry Salt, and others were minutely analyzing changes in film technique in the earliest years. Here at Madison, Tino Balio and Doug Gomery were revising the study of Hollywood as a business enterprise. Specialists working on national cinemas, from Russia, Italy, and the Nordic countries, were showing that there was far more diversity in world cinema than was dreamt of in orthodox histories.

We were part of this generation of revisionists. In the 1970s and 1980s Kristin concentrated on European and American silent film, studying both stylistic movements and film distribution, as well as particular filmmakers like Eisenstein, Godard, and Tati. I did work on European and Japanese cinema. We spent years working on a reconsideration of the history of American studio film in collaboration with Janet Staiger. Writing The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 we realized that asking fresh questions was both necessary and exciting.

We were part of this generation of revisionists. In the 1970s and 1980s Kristin concentrated on European and American silent film, studying both stylistic movements and film distribution, as well as particular filmmakers like Eisenstein, Godard, and Tati. I did work on European and Japanese cinema. We spent years working on a reconsideration of the history of American studio film in collaboration with Janet Staiger. Writing The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 we realized that asking fresh questions was both necessary and exciting.

That’s what made our task perilous. Everything, it seemed, needed to be rethought.

Most obviously, countries outside Europe and North America had been neglected. One of my favorite film statistics is this, to quote from our book:

In the mid-1950s, the world was producing about 2800 feature films per year. About 35 percent of these came from the United States and western Europe. Another 5 percent were made in the USSR and the Eastern European countries under its control. . . . Sixty percent of feature films were made outside the western world and the Soviet bloc. Japan accounted for about 20 percent of the world total. The rest came from India, Hong Kong, Mexico, and other less industrialized nations. Such a stunning growth in film production in the developing countries is one of the major events in film history.

Traditional histories, and film history textbooks, had virtually ignored the bulk of film-producing nations. Only one or two major directors would step in from the shadows. Kurosawa summed up Japan, Satayajit Ray stood in for India. And the books’ layout of chapters indicated this second-class status. The history of film was Euro-American, with East Asia, Southeast Asia, South America, and Africa, appearing, if at all, in periods when westerners first got glimpses of their film culture. So Japan was typically first mentioned after World War II, when Rashomon won a prize at the Venice Film Festival. One would hardly know that there were many, and many great, Japanese filmmakers working in a long-standing tradition.

As if this weren’t enough, we were determined to include other varieties of artistic filmmaking. Documentary cinema, animation, and experimental film had attracted subtle historians like Bill Nichols, Mike Barrier, and P. Adams Sitney. We weren’t experts in these areas, but we were keenly interested in the debates in that domain, and so, guided by these and other scholars, we sought to integrate the histories of documentary, avant-garde, and animated cinema into our survey.

Kristin and David’s excellent adventure

Straight Shooting (1917).

In sum, we decided that we could write a plausible international history of cinema—not a be-all and end-all, but a new draft that reflected the rich variety of new findings and fresh perspectives. Like all historians, we had to be selective. We couldn’t, for instance, track every nuance of the “false starts and detours” in early film technique. More globally, we decided to concentrate on three lines of inquiry.

First, we studied changes in modes of film production and distribution. This inquiry committed us to a version of industrial history. How filmmaking was embedded in particular times and places, how it connected to local culture and national politics: these factors affected the ways films were made and circulated. For example, the early distribution of films followed the trade routes of late nineteenth-century imperialism. That global system started to crack with the start of World War I. A new world power, the United States, became the major film exporting country—a position it has enjoyed for most years since then.

Secondly, we studied changes in film form, style, and genre. We treated these artistic matters as not wholly the products of individual innovators but also as more widely-developed practices and norms. This emphasis on norms allowed us to link, in some degree, the development of technique to opportunities and constraints presented by film industries.

This angle of approach also meant looking at older works with a fresh eye, informed by others’ research but also by our own interests in film as an art. We were obliged to seek out films lying outside the orthodox story. Birth and Caligari and M feature in our account, but so do The Cheat and Assunta Spina and Liebelei. In those pre-DVD days, few of the titles we sought could be found on video, but we preferred to watch film on film anyway. So it was off to the archives. Fortunately, many collections were wide-ranging. We saw Egyptian and Swedish films in Rochester, French and Italian films in London, Indian and Japanese films in Washington, D. C., Polish and African films in Brussels. Committed to documenting our claims with frame enlargements, not production stills, we were lucky to be able to take photos from many of the movies we saw.

In looking at national film industries and artistic change, we wanted to go beyond local observations. So a third question pressed upon us. What international trends emerged that knit together developments in different countries? We could not claim expertise in all the relevant national traditions, but we could, by drawing on films and other scholars’ writings, create a comparative study that gave a sense of the broad shape of film history.

In looking at national film industries and artistic change, we wanted to go beyond local observations. So a third question pressed upon us. What international trends emerged that knit together developments in different countries? We could not claim expertise in all the relevant national traditions, but we could, by drawing on films and other scholars’ writings, create a comparative study that gave a sense of the broad shape of film history.

For example, we could point to the emergence of tableau cinema in many countries in the 1910s. We could consider various models of state-controlled cinema in the 1930s and discover the “New Waves” that emerged not only in France but around the world in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Citizen Kane popularized a “deep-focus” look, but comparative study showed us that its principles were prefigured in Soviet cinema of the 1930s and spread to most major filmmaking nations in the 1940s. Not all trends march in lockstep, but there was enough synchronization to let us plot broad waves of change across the 100 years of film. Our aim was a truly comparative film history.

As a kind of overarching commitment, we wanted readers to think about what historical processes had shaped earlier historical frames of reference. How, for instance, did the “standard story” and the mainline canon get established in the first place? Part of the answer lies in the growth of film journalism and film archives. Why did Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa, and other directors get so much fame in the 1950s and 1960s? True, they made exceptional films, but so did many other directors who remained unknown to a wider public. We suggested that the “golden age of auteurs” owed a good deal to developments in film criticism and to the postwar growth of film festivals. What led Japanese anime to a period of international popularity in the 1980s? Not only worldwide television distribution, but also devoted fans who spread their gospel through fanzines, videocassettes, and the youthful Internet. The “institutional turn” in film research of the 1970s and 1980s pushed us to consider how film industries and international film culture governed the way films were made and circulated.

The research programs that were launched in the 1970s were characterized by a greater self-consciousness than we had seen before. Historians questioned their assumptions and explanations. Why attribute originality only to “great men” without also examining their circumstances? Why presuppose that film technique grows and progresses in a linear way? To capture this new self-consciousness about purposes and methods, we incorporated something that had never been seen in a film history before: an introduction to historiography. In its latest incarnation it can be found elsewhere on this site. We also appended to each chapter short “Notes and Queries” discussing intriguing side issues, debates in the field, and topics for further research.

Up-to-date, and beyond

10 Canoes (2006).

The result of our efforts was first published by McGraw-Hill in 1994 as Film History: An Introduction. A second edition appeared in late 2002. More recently, we’ve spent about twenty months preparing a third edition, which will be published on 20 February this year.

We thought that writing the first edition was bloody hard, and it didn’t get any easier on the second or third pass. As usual, however, visiting new material broadens your compass. Writing my portions of the first edition had a profound impact on my research, but also on my personal tastes. The activity awakened my interest in Hindi cinema of the 1950s, Latin American cinema of the 1960s, experimental work of the 1980s, and African film of the 1990s. On this third round, I was caught up in the innovations of contemporary Korean film and of avant-gardists like Sharon Lockhart. Overall, our urge to trace cinematic creativity around the world led us to a greater appreciation of the wonders of film.

Film History‘s third edition consists of six parts. The first looks at early cinema, from the 1880s to the end of the 1910s. The second considers the late silent era through the 1920s and slightly beyond. Part Three surveys the international development of sound film, up to 1945. The postwar era, from 1945 to the end of the 1960s, constitutes Part Four. We next consider the contemporary period, generously conceived as running from the 1970s to the present. The last section, Cinema in the Age of Electronic Media, makes up for the broad compass of Part Five by reconsidering trends that took shape during the 1980s.

Film History‘s third edition consists of six parts. The first looks at early cinema, from the 1880s to the end of the 1910s. The second considers the late silent era through the 1920s and slightly beyond. Part Three surveys the international development of sound film, up to 1945. The postwar era, from 1945 to the end of the 1960s, constitutes Part Four. We next consider the contemporary period, generously conceived as running from the 1970s to the present. The last section, Cinema in the Age of Electronic Media, makes up for the broad compass of Part Five by reconsidering trends that took shape during the 1980s.

What’s new in this edition? Several small changes have been made in the early portions to reflect newly available films and filmmakers now recognized as important. We have updated coverage of documentary with discussions of the rise of the theatrical doc and its two most striking practitioners, Errol Morris and Michael Moore. We have likewise expanded our section on avant-garde filmmaking by considering “paracinema,” which should have been in earlier editions, and the increase in cinema presented as installations and gallery works.

As for national cinema developments, we have extended our survey of western Europe and the USSR (Chapter 25), continental and subcontinental cinemas such as Latin America, Africa, and India (Chapter 26), and East Asia and Oceania (Chapter 27). New coverage is given to the recovery of the Russian and Chinese industries, the increasing world presence of Bollywood, and fresh talent from the Middle East and South Korea.

The book’s last part continues to host a chapter (28) on American cinema’s development in the light of home video and the rise of independent filmmaking; the blockbuster and Mumblecore are among the subjects we tackle. As in the second edition, we devote a chapter to globalization, which lets us trace the struggle between Hollywood’s global blockbusters and countervailing trends in other regions. This chapter allows us to study other globalizing processes, such as multiplexing, the Internet, fan culture, piracy, and diasporic populations.

Chapter 30 is new to this edition. It examines the effects of the digital revolution on all aspects of film production, as well as on new means of distribution and exhibition. The subjects covered include 3-D animation, DIY independents, and online distribution. We end by recognizing film as no less international an art form than it was in the earliest decades, when silent films slipped freely across national borders.

As in the early editions, we’ve tried to synthesize contemporary contributions but also add our own research and our own interpretations. Here, for example, is our very cine-centric conclusion about “the death of film.”

Will this barrage of new media ultimately overwhelm the cinema? Will the Internet, video games, and personal music players take over as the preferred forms of entertainment? Possibly, but there is evidence against that notion.

Each time that a digital platform appeared, it initially lacked the capacity to show films. Yet each platform adapted itself in order to add that capacity. In the 1990s, computers acquired the power to display movies. The Internet originally did not show films, but now it has Quicktime and downloads. Cell phones started out as communication devices, but later models included a camera and screen so that users could shoot and view films. The first game consoles could not show movies, but after the advent of DVDs, the next generation of machines became combination players. The original iPod and other personal music devices were strictly for audio, but Apple added the capacity to download digital video from computers, DVDs, and the Internet. The iPod enlarged its screen to better display films, even though that meant abandoning the signature click-wheel in favor of touch-screen controls.

Far from killing movies, digital media have allowed them to leave the theater and our living rooms. Now they can travel with us almost anywhere. In effect, film has reshaped the new media to accommodate it. As new digital devices emerge, we suspect that they, too, will adjust themselves to the cinematic traditions that have developed over 110 years.

No book can be definitive, partly because things change astonishingly fast. When we wrote the revision, DreamWorks was firmly within the Paramount family, and our chart of media conglomerates on p. 683 left it there. In page proofs, we shifted it when it seemed all but certain to move to Universal. Now comes the news that DreamWorks has signed with Disney. Likewise, the flow of important research hasn’t abated, and valuable books, like Jay Beck and Tony Grajeda’s Lowering the Boom: Critical Studies in Film Sound, were published after we went to press. Another peril of writing contemporary history, then: Keeping up.

To squeeze in our new material, we’ve had to excise the historiography essay mentioned above, as well as our Notes and Queries and our plump bibliographies. Those, all updated, have appeared at the McGraw-Hill site. Even if you’re not reading the book, feel free to go to the Student Edition tab and browse through the Notes and Queries for each chapter. Some of these brief, bloggish items may pique your interest.

Without exactly planning to do it, we seem to have come up with the most wide-ranging, extensively illustrated survey of world cinema history available in English. The third edition of Film History: An Introduction runs to 750 large-format pages, not counting the index. It contains hundreds of black-and-white frame enlargements and thirty pages of color illustrations.

We hope that if you’re interested in film history you’ll take a look. Feel free to write to us with your thoughts, especially if you find misprints (we’ve been chasing them for months) and factual errors. We’d also appreciate comments about our larger arguments and interpretations. We improve only by constantly rechecking what we say and how we say it.

The quotation about 1950s world film output comes from Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell, Film History: An Introduction, third ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009), 373.

Tokyo Drifter (1966).

It’s the 80s, stupid

Choose Me.

DB here:

In an earlier post, I proposed that film historians can’t safely assume that decades mark off meaningful periods. Yet I can’t help succumbing to the temptation myself. It happens every time I hear about how the 1970s were the last great decade in American film.

We’re often told that back then, countercultural forces gave us movies of restless auteur ambition like Five Easy Pieces and Nashville and Mean Streets and Shampoo. Meanwhile, The Godfather, Jaws, American Graffiti, and even Star Wars not only rejuvenated the studio system but also reflected something of their directors’ temperaments, providing Hollywood with an enduring new mythology. So far, so plausible.

Then, the story goes, came the age of the blockbuster. Thereafter, moviemaking was simply selling out, winning the weekend, building franchises, and catering to disposable teenage income. Like big hair and padded shoulders and Wham!, the films of the 1980s are apparently something to be ashamed of.

The glorious burnout

This judgment is spelled out most fully in Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders and Raging Bulls, a celebration of and postmortem on the Movie Brats era of the 1960s-1970s. Biskind doesn’t try to make a critical case for the films of the period; he assumes that everyone counts these movies as edgy masterpieces. He’s more interested in the sensational lifestyle of the filmmakers. Filling his pages with gossip about alcohol, cocaine, backbiting, squabbles, and the horizontal mambo, he could hardly deny that his favorite directors were somewhat self-destructive. He justifies their escapades by treating them as driven artists fighting a corrupt system—mavericks, in fact. (Yes, he uses the word.) This idealization occasionally leads to mawkishness that Biskind would castigate if he saw it on the screen:

Hal Ashby did die just after Christmas, on a raw, rainy Tuesday. . . .The papers said it was liver and colon cancer, but it could just as well have been a broken heart. (1)

Forgiving the flaws of these all-too-human directors, Biskind spares no sympathy for the producers who focused on the bottom line. With rising budgets and distribution costs, the studios’ cynical leaders chose to play safe with megapictures that purveyed “smarmy, feel-good pap.” (2)

It’s a good, simple story, and the problem is the simplicity. The top-grossing movies of the 1970s include Love Story, Fiddler on the Roof, The Sting, The Towering Inferno, Rocky, Grease, Smoky and the Bandit, and Star Trek: The Motion Picture. These aren’t exactly testaments to personal expression. The megapicture mentality we associate with the 1980s was already present in some of these, as well as in The Poseidon Adventure, Earthquake, and Superman. The four-quadrant movie was taking shape well before Heaven’s Gate brought auteur ambitions crashing to earth.

Further, not every 1980s movie aimed to be a blockbuster. I tried to argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It that just as in the classic studio era, we have to look for creativity beyond the titles that dominate the best-10 and top-grosser list. In addition, there are always filmmakers whose sensibilities naturally match the demands of big-budget projects: David Lean and Anthony Mann managed it in the 1960s, Spielberg and Lucas in the 1970s. In the 1980s several directors were able to make strong, original megapictures.

So you can make a good case that the 1980s gave America a burst of first-rate films and remarkable new talent. At all levels, from ambitious prestige items to dazzling genre pictures, the decade is nothing to be sneezed at. The maw of home video had to be fed, so the demand was for product of all sorts. Videotape rental expanded specialty niches and cult markets. Filmmakers could finance projects through video and foreign presales, and investors took chances at many levels. The era saw a revival of ambitious independent films, which played alongside program pictures, Oscar bait, and summer blockbusters. Romantic comedy, action movies, and science fiction enjoyed a strong run. And many of the people we still consider genuine movie stars—Tom Hanks, Julia Roberts, Glenn Close, Harrison Ford, Mel Gibson, and Tom Cruise—are ineluctably creatures of the 80’s.

My defense doesn’t spring from generational bias. I don’t have the excuse of adolescent nostalgia that makes Tom Shone write:

What a grand piece of historical luck it was to be in your early teens when Raiders of the Lost Ark came out—when Spielberg and Lucas were in their prime and the very act of going to the movies seemed to come with its own brassily rousing John Williams score. Later on, we would learn to cuss and curse the infantilization of the American film industry, just like everyone else, but back then we were too busy infantilizing it to notice. (2)

So here are some assorted, more or less objective reasons to consider this decade as making a remarkable contribution to U. S. film history.

New talents, old genres

Near Dark.

Put aside two highly influential 1980s films, E. T.—The Extraterrestrial and Raiders of the Lost Ark, since Biskind would consider them feel-good pap. Put aside Raging Bull, which he grants canonical status as the capstone masterwork of the 1970s generation. Even granting all this, most major 1970s directors didn’t vanish in the megapicture decade.

Scorsese’s underrated King of Comedy was a portrait of a social type, the obstinate, delusional nerd; we all knew one, but we hadn’t seen him on the screen before. Altman moved from Popeye, a sort of anti-musical and anti-comic-book movie, to intimate theatre pieces like Streamers and Secret Honor and Fool for Love.

From Jonathan Demme we had Melvin and Howard and Something Wild; from Clint Eastwood, Pale Rider and Bird; from Paul Schrader, American Gigolo, Cat People, Mishima, and the Bressonian Patty Hearst. Coppola, supposedly a marked man after Apocalypse Now, gave us another anti-musical (One from the Heart) and a robust biopic (Tucker: The Man and His Dream). De Palma outraged his audience with Dressed to Kill, Blow Out, and Scarface. John Carpenter’s B-movie sensibility was given full throttle in Escape from New York, The Thing, and Big Trouble in Little China. And arguably David Cronenberg hit his stride with Scanners, Videodrome, The Dead Zone, The Fly, and Dead Ringers. Maybe we should just call the 80’s the Cronenberg Years.

Veteran directors also got in their licks. Sidney Lumet had a remarkable run; if you bet on Serpico, I see you The Verdict and raise you Prince of the City. Sergio Leone offered Once Upon a Time in America, a film that looks more ambitious on each viewing. John Huston checked in with Prizzi’s Honor and The Dead, Sam Fuller with The Big Red One.

Biskind castigates the 1980s for parvenu producers like Don Simpson and Michael Eisner, but he doesn’t mention all the new directors who emerged. Some allied themselves with independent companies or mini-majors, others worked through the studios, but in any case it’s strange to overlook Michael Mann, Oliver Stone, Tim Burton, the Coens, Spike Lee, Robert Zemeckis, James Cameron, George Miller, Barry Levinson, John Sayles, Gus Van Sant, Jim Jarmusch, Katherine Bigelow, David Mamet, Steven Soderbergh, et al. Just cherry-picking their films yields up Thief, Manhunter, Salvador, Platoon, Wall Street, Born on the Fourth of July, Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure, Beetlejuice, Batman, Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, She’s Gotta Have It, School Daze, Do The Right Thing, Used Cars, Diner, Tin Men, The Abyss, Return of the Secaucus Seven, Matewan, Mala Noche, Drugstore Cowboy, Stranger than Paradise, Down by Law, Mystery Train, Near Dark, House of Games, Things Change, sex, lies and videotape. Not many dribs of feel-good pap in this bunch.

There was a lot of bloated Oscar bait, I grant you. Is anybody, anywhere on the globe watching Gandhi or Chariots of Fire or Driving Miss Daisy at the moment? But we had Amadeus, an intelligent biopic, as well as Tender Mercies and Coal Miner’s Daughter and Rain Man.

The 1980s kept genres firmly at the center of Hollywood. Instead of working against genre conventions, as many Movie Brats had done (not all; remember Bogdanovich), many of the most talented Eighties directors found ways to do what they wanted in and through genres. In this sense, they were more like Hawks and Ford and other classical filmmakers. The “personal” mainstream film wasn’t a contradiction in terms.

Take science fiction. Blade Runner, which became as influential as Metropolis and 2001, pushed to an extreme the premise of Alien: The future will be rusty, drippy, and stygian. Blade Runner also expanded teenage vocabularies by at least one word (can you say dystopian?). Handed another cult science-fiction story, David Lynch turned Dune into a pageant of hallucinatory grotesques. Voices float unbidden in the air, and boils never looked so glistening. Today, these overstuffed genre pieces repay viewing more than Out of Africa does.

Granted, the 80s gave us plenty of earnest clunkers in the drama department, perhaps most notably The Color Purple. But we also have Body Heat, Never Cry Wolf, Fatal Attraction, Witness, Kiss of the Spider Woman, The Accused, Terms of Endearment, The Right Stuff, Field of Dreams, River’s Edge, Places in the Heart, The Big Chill, and other sturdy efforts.

If you admire Ishtar, then add it to this list. Ditto the parboiled stylings of Alan Parker: Pink Floyd The Wall, Birdy, Angel Heart, and Mississippi Burning. And if you grew up on John Hughes movies, there’s no more to be said by me. You probably still love Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club, and the rest. Okay, maybe we should consider it the Hughes decade.

Laughs and bullets

Fantasy comedy flourished in the period, from a masterpiece of dark humor like Beetlejuice to amiable fare like Ghostbusters, Big, Splash, and All of Me. Add to this list Gremlins, sort of the down-and-dirty E. T.; I dare you to watch this or the 1990 sequel without laughing. Farce was also on the agenda, with the output of Mel Brooks (Spaceballs) and the Zucker-Abrams team (Airplane! Top Secret!), and one-offs like A Fish Called Wanda. Saturday Night Live continued to breed new stars. Bill Murray, today an axiom of the independent cinema, made his debut in the period. And after The Adventures of Pluto Nash (2002) and Meet Dave (2008), it’s heartening to remember Eddie Murphy’s appeal in 48 HRS, Beverly Hills Cop, Trading Places, and Coming to America.

On the romantic comedy front, we had Victor/ Victoria, Mystic Pizza, Desperately Seeking Susan, Broadcast News, Moonstruck, Bull Durham, and one of the supreme achievements in the genre, Tootsie. I never met anybody who didn’t like Tootsie.

Speaking of romantic comedy, every era has its favorite perky blonde. Long ago it was Doris Day; today it’s Reese Witherspoon. In between came Goldie Hawn, who gave us Private Benjamin and, mixing it up with Chevy Chase, two trim comedies Foul Play (okay, 1978) and my own favorite, Seems Like Old Times, a frothy revival of the screwball tradition. Her mantle was picked up by Meg Ryan in When Harry Met Sally, and she continued to deliver pert-and-lovable through the 1990s.

Movies centering on kids, like WarGames and The Karate Kid and Stand by Me, proved unexpectedly enjoyable to grownups too. Back to the Future was an intricate Oedipal fable, coarsened but also complicated in the second installment and sweetened in the third. Coppola’s flirtation with teenage art movies gave us The Outsiders and Rumble Fish. Fame is probably a part of every Gen-Xer’s childhood too, as are other musicals like Flashdance, Dirty Dancing, Hairspray, and the 1989 resurrection of Disney animation, The Little Mermaid.

With the new attractiveness of the global market, the demands of home video, and increasingly sophisticated special effects, the 1980s brought the really violent action movie into its own. I’m not ready to defend Rambo and its clones, not even the indifferently directed Lethal Weapon. But I will stick up for Fort Apache—The Bronx, The Terminator, Robocop, Aliens, Predator, and The Untouchables, the last of which has given us many lines appropriate to President-elect Obama’s Chicago-based campaign. (“Brings a knife to a gunfight.” “They send one of yours to the hospital, you send one of theirs to the morgue.”) Road Warrior probably counts as an import, but we ought to treat Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome as a Hollywood release. This sequel transposes the earlier film’s grimly amusing chases and stunts into full-out slapstick, while giving us one of the most touching finales of any film of its day.

I save for last the obligatory mention of Die Hard, the Jaws of the 1980s: a perfectly engineered entertainment.

Middlebrow, semi-highbrow

I don’t automatically despise middlebrow culture (a subject, I hope, for a future blog). But many cinephiles do, so I’m probably in the minority in my esteem for another prototypical 80s director, Ron Howard. Like Zemeckis, he started his climb with a something a little naughty, the mortuary comedy Night Shift. Thereafter he tried to update Hollywood genres in ingeniously middlebrow fashion, from Cocoon and Gung Ho to Parenthood, probably his best film of the decade.

Hollywood films have long blended art-cinema experimentation and genre conventions; it’s what a lot of people found exciting about The Conversation and The Godfather Part II and the seventies work of Altman. That sort of blending continued in the 1980s. The most obvious examples came from David Lynch, with The Elephant Man (surreal visions plus disfigured hero) and Blue Velvet (the Hardy Boys meet sadomasochism). Another merger of art movie and genre movie was The Stunt Man, a three-card-monte affair about moviemaking. Want a postmodern musical? David Byrne’s True Stories treated avant-garde art as of a piece with down-home kitsch. The music track is infectious, with the lip-sync sequence on “Wild, Wild Life” capturing the sense that everyone can be famous for, well, not fifteen minutes but about ten seconds.

I’m venturing onto disputed terrain here, but I vote for Alan Rudolph’s Choose Me as an intelligent blend of Euroart neuroticism and off-kilter romantic comedy. The first shot, a long take craning down the side of a bar sign and along a street filled with hustlers sometimes dancing and sometimes not, accompanied by Teddy Pendergrass’s music, remains a tingling moment of bravado. The interruptive flashbacks (or are they visions?) and some tricky pan shots play daringly with character motivations. I also admire Trouble in Mind and The Moderns, but I realize that making a case for them would probably be pushing my luck.

When was the last time Woody Allen made a really good movie? Hard to say, but recall three 1980s titles: Hannah and Her Sisters, Zelig, and Crimes and Misdemeanors. They show that Allen could take chances with adventurous narrative strategies, while mixing in mordant dialogue, social satire, surprisingly bitter comedy, and earned pathos. Consider Radio Days the cherry on top.

There are plenty of other worthwhile items: My Favorite Year, The Dream Team, Valley Girl, Adventures in Babysitting, Excalibur, Earth Girls Are Easy, The Abyss, This Is Spinal Tap, D. C. Cab, The Princess Bride, Total Recall, Day of the Dead, Monkey Shines, Streets of Fire, Housekeeping, Purple Rain, Koyaanisqatsi, The Thin Blue Line, and on and on. Few are perfect, but most offer genuine pleasures, and some are as imaginative and bold as the canonized films of the 1970s, albeit in different registers.

Not every film on my list will convince everybody, but I think there are enough solid achievements to show that the blockbuster era didn’t suffocate creative filmmaking in the U.S. In some cases it enhanced it.

Come to think of it, the American cinema always renews itself. Take the 90s. There’s My Cousin Vinny and . . . .

(1) Biskind, Easy Riders and Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock’n’Roll Generation Saved Hollywood (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998), 438.

(2) Biskind, Easy Riders, 404.

(3) Tom Shone, Blockbuster: How Hollywood Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Summer (New York: Free Press, 2004), 11. Shone’s book is the best antidote I’ve found to the overreaching attacks on 1980s cinema. For a dauntingly comprehensive filmography, see Robert A. Nowlan and Gwendolyn Wright Nowlan, The Films of the Eighties (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1991).

One from the Heart.