Archive for the 'Books' Category

Summer show and tell

DB here:

I came back from a month in Europe to find a stack of magazines, books, and DVDs waiting. There was Before the Rain, much Cecil B. DeMille, and a mass of Anthony Manns (some discussed on Jonathan Rosenbaum’s blog). How will I ever catch up? I was reconciled to the idea that I’d die before reading every book I owned, but now I have to face the same conclusion about movies on discs.

Herewith some items from my trip to Amsterdam, Bologna, and Brussels that I couldn’t squeeze into earlier blogs. I end with the movie I watched upon my return.

DaViD’s DVD depredations

In Bologna, I learned that Oksana Bulgakowa is at work studying how cinema captured everyday human gestures at earlier points in history. Visit her site, where a DVD is available on her research.

Speaking of DVDs, travel inevitably brings them into your baggage, despite the high prices and the abysmal exchange rate.

*At Bologna our Copenhagen pals gave us the new Danish Film Institute DVD, Danish Experimental Classics 1942-1958. Not quite yet available for sale, it should show up here—as has a third collection of Jørgen Leth movies. While you’re sniffing around the site, eyeball the archive’s new state-of-the-art storage facility.

*Hubert Niogret, indefatigable director of documentaries on Asian cinema, has also produced an excellent collection of interviews, Mémoires du cinéma francais: De la libération à nos jours. Together we sampled an outstanding Bologna specialty, gramigna con salsiccia.

*Isabel Biver passed along the latest installment of Imagination in Context, a series of books and discs about early cinema and Antwerp. Animalomania includes English-language text and some nice films, including a hand-colored fantasy about butterfly collectors who wind up with pretty girls dressed as butterflies.

*Isabel Biver passed along the latest installment of Imagination in Context, a series of books and discs about early cinema and Antwerp. Animalomania includes English-language text and some nice films, including a hand-colored fantasy about butterfly collectors who wind up with pretty girls dressed as butterflies.

*At a sale table I found the Index DVD of Ivan Ladislav Galeta’s works, which includes the remarkable Two Times in One Space (1976/1984). I caught up, finally, with the Austrian Film Museum’s reconstruction of Frank Borzage’s The River.

*In Brussels I picked up the StudioCanal collection of Méliès films, which complements the recent Flicker Alley collection. Of course then I had to splurge on Laurent Mannoni’s gorgeous book, L’oeuvre de Georges Méliès.

*Also snagged a batch of Gosha and Uchida swordplay movies, but in the Japanese line my real finds were a French edition of Night and Fog in Japan, one of Oshima’s finest (also just out in the UK) and the Carlotta set of three 1930s Mizoguchi films: The Downfall of Osen, Oyuki the Virgin, and Poppies. All drawn from 16mm copies, these items vary drastically in quality. Osen is superb, but Oyuki is iffy, and Poppies is a rain of scratches, the worst copy I’ve ever seen.

*Also snagged a batch of Gosha and Uchida swordplay movies, but in the Japanese line my real finds were a French edition of Night and Fog in Japan, one of Oshima’s finest (also just out in the UK) and the Carlotta set of three 1930s Mizoguchi films: The Downfall of Osen, Oyuki the Virgin, and Poppies. All drawn from 16mm copies, these items vary drastically in quality. Osen is superb, but Oyuki is iffy, and Poppies is a rain of scratches, the worst copy I’ve ever seen.

*To top things off, Tom Paulus of the University of Antwerp, bestowed upon me his extra copy of Edgar G. Ulmer’s Hannibal (1960) in SuperCineScope. This is what friends are for.

Interlude: Some Europix, arty and otherwise

My last sigh x 3

Every summer the Arenberg cinema holds a retrospective season, Ecran total, and it helps make Brussels a great film city. This time there were cycles dedicated to Delphine Seyrig, Al Pacino, the Japanese New Wave, and children, as well as a batch of classics. Prints are usually fresh, and the programming is very eclectic. So Saturday, the day before I flew home, I saw three movies at the Arenberg. I liked the West Anderson better than I expected to, though the clash between the overall feyness and a child’s death left me a little stranded emotionally. I had forgotten the Lumet since the initial release; not up to Prince of the City methinks, but a sturdy, earnest piece of work. The Duras proved as mesmeric as ever, and still unthinkable on DVD (even though I have two DVDs of it). All in excellent prints and pinpoint-sharp projection. Cinephilia satisfied: No need to watch anything on the plane home the next day.

No need to eat much either, because of a delicious late meal with our old friend Geneviève van Cauwenberge, head of the film and media program at the University of Liège.

Trafficking

For my avant-birthday, Kristin (a) bought me a beautiful Krazy Kat page; (b) took me out for sushi; and (c) settled in with me to watch the new Criterion disc of Jacques Tati’s Trafic. It’s been one of our favorites for a long time; I saw it on initial release in Paris while researching my dissertation. It’s not as densely loaded as Play Time, nor as structurally rigorous as M. Hulot’s Holiday. (Kristin wrote about both these films in her book Breaking the Glass Armor; my bias aside, her analyses are really illuminating.) Trafic has its own charms, though, and Gary Giddins gets at several of them here. We’ve collected versions on tape and even a Finnish DVD, which calls him Tatin, but the Criterion looks to be the best version yet. (Still, why not anamorphic?)

For my avant-birthday, Kristin (a) bought me a beautiful Krazy Kat page; (b) took me out for sushi; and (c) settled in with me to watch the new Criterion disc of Jacques Tati’s Trafic. It’s been one of our favorites for a long time; I saw it on initial release in Paris while researching my dissertation. It’s not as densely loaded as Play Time, nor as structurally rigorous as M. Hulot’s Holiday. (Kristin wrote about both these films in her book Breaking the Glass Armor; my bias aside, her analyses are really illuminating.) Trafic has its own charms, though, and Gary Giddins gets at several of them here. We’ve collected versions on tape and even a Finnish DVD, which calls him Tatin, but the Criterion looks to be the best version yet. (Still, why not anamorphic?)

Trafic is definitely odd, with a choppy opening and quickly-cut extreme long shots. This time around I was struck by how much a landscape artist Tati was. Sometimes he built his own massive milieu, as in Play Time, and sometimes he merged his constructed spaces with the real world, as in the houses of Mon Oncle. In Hulot and Trafic he exploited the vastness of real spaces, usually the backdrop for human foibles made minuscule. Trafic gives us a un-picturesque European countryside. Sliced by superhighways, the bland vistas are dotted with rusted cars, empty fields, and forlorn gas stations. Drivers hiking off for fuel or trying to patch up their vehicles dwindle to pathetic dots in the image. Cities are no better, choked with pale cars that advance fitfully. Then there’s the huge convention center housing the auto show. The opening gag of men stepping carefully over stretched strings that we can’t see etches tiny gestures into a monumental frame. Masters of ambivalent vastness: Antonioni, Angelopoulos, Tarr….and Tati?

The setpiece of Trafic is of course the car crash, and it, like Tati’s characteristic running gags (e.g., cheap busts of historical figures as bonuses for gas fillups), reminds us of the follies of the car culture. In a sense, the entirety of Trafic seems an outgrowth of Play Time‘s final sequence, which turns a traffic roundabout into a carousel. But here there’s little sense of a mundane world transformed into a playground. Instead, modern misery remains the norm, as pedestrians zigzag their way through infinite gridlock.

Beyond the satire, which can get fairly caustic, I have always loved Tati for juxtapositions so weird and remote that you wonder if they could count as gags. Then you wonder if you’re the only person to notice them. In Play Time, everybody gets the running gag about the drunk at the bar of the Royal Garden tipping over on his stool. Far less evident is a moment I always find disconcerting. When the air-conditioning at the restaurant is finally switched on, the air vents make the loose skin on one woman’s back ripple. The denunciation of flabby bourgeois comfort comes and goes in a flash, and when I first noticed it in the 1970s I thought: Is it accidental? Did Tati mean for me to see it? Does anybody else notice? And does this count as a gag, or just, well, peculiar?

Likewise, in Trafic, Tati can cut from a bisected car on display to a quasi-abstract angle on traffic, with one fender sliding past an identical one.

We’re supposed to notice the purely sculptural analogy of split cars. And we’re supposed to find it at least a little funny. Right? Right?

Whether you agree or not, Tati’s vacant long-shots and unpredictable cutting leave space for such musings. Comedy with a question mark, from one of the dozen or so greatest directors who ever lived.

Kristin is now at Comic-Con, armed with fan-friendly T-shirts and a carrier bag from Lambiek. Her mission: to sell a copy of The Frodo Franchise to each of 125,000 attenders. Expect dispatches from her in the days to come.

P. S. My thanks to the staff of the vaults at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, who were extremely helpful during my visit. I didn’t manage to photograph everybody, but I owe special gratitude to the supervisor Marianne Winderickx, pictured below.

PPS 24 July: Olli Sulopuisto clears up my Tatin puzzlement: “In Finnish the trailing n is the mark of a possessive, similar to ‘Jacques Tati’s…'” Thanks to Olli.

Minding movies

DB here:

When we watch films, our bodies and minds are engaged at a great many levels. Nobody doubts this claim. The interesting questions are: What forms does this engagement take? What gives movies the ability to seize our senses, prod our minds, and trigger emotions? How have filmmakers constructed films so as to tease us into such activities? What, to use a phrase from the philosopher Noël Carroll, creates the power of movies?

On this blogsite, I’ve touched on such questions in concrete cases—how eye movements shape our uptake of story information (here and here), how suspense can be created and sustained (here). Those are just small-scale samples of what is, to me, an exciting and promising way of studying certain aspects of cinema. That research trend is growing substantially, and an upcoming event on our home turf marks a new phase.

In June, the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image will hold a conference here in Madison. This organization was officially created in 2006. Its membership grew out of an informal group of scholars who had been meeting every couple of years since 1997. The meetings have been stimulating affairs, bringing together film historians and theorists, filmmakers, philosophers, and social scientists. Now we’re a full-fledged, incorporated association. We have annual membership dues (cheap at $25), a slate of officers, and a set of bylaws. The Society’s conferences will become annual next year, when we convene at the University of Copenhagen.

You can learn details about the organization here, and you can scan the conference schedule here. There’s also information about getting to Madison and visiting local attractions. (I recommend The House on the Rock.) The earlier incarnation of our group, The Center for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, has a rather full archive here.

As president of SCSMI, I’ve had my say about the organization’s remit on the webpage. I’m using today’s blog entry to gesticulate toward some ways that the organization tries to advance our understanding of films, filmmaking, and film viewing. I’ll also shamelessly promote our event.

What is this fascinating new film theory known as cognitivism?

There are, roughly, two ways to think about doing film theory. One way is to look at a body of research or reflection in some established area (history, philosophy, psychology, etc.) and ask: What can it tell me about movies? So you might look at Freudian psychoanalysis or Gestalt perceptual psychology as a whole and then home in on ideas that seem to have relevance to cinema.

The other way to do film theory is to look closely at some filmic phenomenon and ask: What’s the best way to understand this aspect of movies? Your reading and thinking might then lead you to adjacent fields of inquiry for help. In the first instance, you start broad and move to particular cases. In the second, you start with particular cases and explore what broader ideas or information can shed light on them.

On the whole, academic film studies of the 1970s and 1980s started from the big-picture end. Several scholars decided, on various grounds, that psychoanalysis (a mixture of Freudian and Lacanian versions), provided a powerful explanatory system for virtually all human activity. The ideas of that system were then mapped onto many humanities disciplines, and then applied to particular instances of literature, the visual arts, and cinema. Many times, the big system became a doctrinal whole, a Theory of Everything, that was unquestioningly accepted.

In a 1989 essay called “A Case for Cognitivism” (available online here), I suggested that Freud did not intend his theories to become this sort of all-encompassing doctrine. And whatever Freud thought, in that essay and a later one for Post-Theory I argued that it’s more fruitful to develop film theories in a middle-level fashion, shifting from concrete problems to broader explanatory frameworks. My collaborator Noël Carroll called this focus on particular problems “piecemeal” theorizing.

It was through middle-level, piecemeal thinking that I first became interested in the cognitive sciences. During the early 1980s, I was concerned to understand how films told their stories. This process was usually called narration. From the start it seemed clear to me that filmic storytelling doesn’t work unless the spectator does certain things. We make assumptions, frame expectations, notice certain things, draw inferences, and pass judgments on what’s happening on the screen.

Film narratives are designed for just this sort of active pickup. I was interested, then, in how certain traditions of filmmaking shaped that pickup—by parceling out story information, composing shots, structuring scenes, and so on. Going beyond those particular traditions, what general capacities of spectators enabled us to understand the twists and turns of a film’s action, as presented by the movie?

During the 1960s Christian Metz had posed my question in a precise and provocative way—“We must understand how films are understood”—and had used it to found his initial version of a semiotics of cinema. But by the early 1980s, it wasn’t a question that much exercised people working in the dominant paradigm of the moment, psychoanalysis. Moreover, I was and remain skeptical of the psychoanalytic framework; I don’t think it has very solid scientific support.

So I began reading in other domains of psychology. At this point, the “cognitive sciences” were coming into their own as a result of work in linguistics, psychology, and anthropology. I didn’t have the benefit of Howard Gardner’s masterful state-of-play survey The Mind’s New Science (1985), but I saw some of the convergences he was pointing out. Perceptual psychology, social psychology, the shortcuts and shortcomings of informal reasoning, studies in classification and story comprehension–all these illuminated my central questions.

Characterizing, quick and dirty

The answers I proposed to those questions showed up in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985). Nowadays we’d call it an attempt at reverse engineering. In many instances, that book argued, features of narratives in film seemed designed to solicit activities that research in the cognitive sciences has studied. Here’s one example.

The first time we encounter a character in a narrative, we tend to form an immediate, fairly fixed judgment about what sort of person she or he is. Why is this? Why don’t we suspend judgment and wait until we have more information? At least two reasons.

First is what psychologists call the primacy effect, the likelihood that the first item or few items in a series tend to form a benchmark for what will follow. Here are two multiplication exercises:

8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = ?

1 x 2 x 3 x 4 x 5 x 6 x 7 x 8 = ?

Give a person just one of the problems and ask him or her not to do the math but to quickly offer a rough estimate of the size of the result. What happens? People given the first problem tend to give bigger estimates than those given by people who see the second problem. Even though the product is exactly the same, the order of presentation—starting with large or small numbers—seems to have biased people toward different results. The initial items become a rangefinding device for later judgments.

A second reason for our snap judgments about characters stems from a well-supported finding of social psychology. We tend to size up other people using a rule of thumb, or heuristic, that attributes their actions to personality rather than to circumstances. If someone acts bossy in a meeting, we’re inclined to say that the person has an aggressive nature. But if you ask the person why he or she came on so strong, the answer is likely to be “I was having a bad day,” “The responses I was getting were just so lame,” “The pressures of those meetings are intolerable,” and so on. This is called the fundamental attribution error. We tend to assign behavior to character traits rather than take into account contextual factors. We are biased toward believing that others’ misbehavior is due to their temperament while ours was forced by circumstances beyond our control.

In real life, the primacy effect and the fundamental attribution error can be quite unfair ways of coming to conclusions, and they can lead us astray. But filmmakers and other storytellers, being intuitive psychologists like the rest of us, realize how strong these heuristics are, so they design their stories so as to make use of them. Usually, when a character walks into the story world, he or she is characterized by signaling key traits right off the bat.

Consider Back to the Future (released the same year as NiFF was published). It might have begun with Marty McFly skating down the street for several minutes on the way to Doc’s laboratory. Instead, the narration introduces Marty by showing him cranking up the lab’s amplifier to overdrive. He strikes a star pose, hits a guitar chord, and is blasted off his feet. He’s shaken up but awestruck: “Whoa. . . Rock and roll.” We now assume that Marty likes to take risks, that he’s committed to his music, that he’s a bit preening, and that he can bounce back. Likewise, before Marty comes in, during the opening shots exploring the lab, we get information about Doc as well, though more indirectly. For both characters, the narration encourages us to leap to conclusions that will be confirmed again and again in the story that follows.

Sometimes, though, filmmakers thwart our propensities by either neutralizing the initial cues (we don’t know how to read the character) or offering strong ones that are later countermanded (we’ve been led to misread the character). Preminger offers wonderful examples of both possibilities in Anatomy of a Murder. Either way, the filmmaker is still exploiting the primacy effect and the fundamental attribution error, but in order to yield different experiences. Meir Sternberg’s superb book, Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction (1978), points out such strategies and explores in detail what he called, “the rhetoric of anticipatory caution”—the ways that novelists trigger the primacy effect only to force us to reevaluate our snap judgments. Sternberg was, I think, one of the first narrative theorists to bring cognitive research to bear on storytelling strategies.

I found, in short, that experimental results in the cognitive sciences could explain, in a fairly direct way, many of the tactics that stories use to engage us. Contrary to what my Wikipedia entry implies, I’m not a cognitivist 24 hours a day; many of the research questions I tackle don’t depend on such assumptions. Still, since NiFF, I’ve revisited them a few times. Making Meaning (1988), for example, tried to show that a lot of cinematic interpretation is explainable in cognitive terms.

Most recently, some essays in Poetics of Cinema (2007) draw on psychological and anthropological research to clarify why films use certain formal strategies. For instance, what aspects of Mildred Pierce mislead us about what is happening, and how are we led to misremember those aspects? Why do actors stare at each other in a way we seldom see in life? And why don’t they blink the way we do? Another essay in the collection, “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision,” moves to broader terrain. It argues that a great deal of our understanding of films relies not on codes particular to cinema (contra the semiotic tradition) but rather on our everyday inference-making habits and skills.

The cognitive turn

Written in 1982-83, Narration in the Fiction Film leaned heavily on what was then called “New Look” psychology, the first wave of cognitive research in psychology. The pioneers of that program, such as Jerome Bruner, R. L. Gregory, Ulrich Neisser, and others, emphasized the mind’s role in actively building up structures of meaning on the basis of incomplete or ambiguous information. So my claims that films cue us to flesh out their action, invoke schemas (knowledge structures), ask us to reorganize story order, and to fill in missing bits—all stem from that research program. The art historian E. H. Gombrich, another big influence on me, was perhaps the first person to see how New Look psychology could inform theorizing in the humanities.

In the late 1990s, cognitively inflected film theory really took off, and in directions that shaped the growth of SCSMI. The first avatar of the SCSMI was founded by Joseph and Barbara Anderson. Joe and I were graduate students together at Iowa in the early 1970s, where he wrote a dissertation on binocularity in the cinema, and later we worked together here at Madison, where Barb was a grad student. Joe taught a course in film perception that I sat in on occasionally, and it was a revelation. When NiFF came out, Joe (by then a film producer) felt encouraged to go on with his own work, and the result was The Reality of Illusion (1998). It proposed an alternative to the New Look orientation, grounded in J. J. Gibson’s theories of ecological perception. Since then, Joe and Barb have published two anthologies, with contributions from SCSMI members.

At the same period, Torben Grodal published Moving Pictures (1997) a comprehensive theory of cinema grounded in the cognitive sciences, with particular focus on brain functions. Torben was also a founding member of the SCSMI group.

Since 2000, publications in the area have increased markedly, parallel to the growth of cognitive studies in literature and other areas. I hope to discuss some of these books and articles in a later blog.

Broadly, cognitive film theory has tracked the development of the cognitive sciences. After the New Look and ecological frameworks, we’re seeing more emphasis on evolutionary psychology and neuroscience as explanatory forces. Film scholars who talk about adaptive fitness and mirror neurons are still, for the most part, doing middle-level, piecemeal theorizing—trying to explain particular processes by appeal to what scientific research has brought to light. None, I think, expects cognitivism to provide a Big Theory of Everything.

Early on, Noël, I, and others sought to show that the cognitive perspective offered better explanations for some aspects of cinema than the dominant psychoanalytic approach. We were sometimes chastised for being pugilistic and polemical. Yet interestingly, nobody responded to our arguments, let alone replied at the same level of detail. The situation reminded me of Godard’s response to people who complained that Letter to Jane (1972) mistreated Jane Fonda. His reply was: “I merely wrote her a letter, but she never answered.”

In the years since, I have yet to see a substantive critique of the cognitive research tradition in film studies. The only extended argument I know of isn’t really focused on cognitivism and is surprisingly flimsy. (My response to it is here.)

Advocates for Poststructuralist or Cultural Studies perspectives sometimes dismiss the cognitive framework as “common sense.” But common sense is in the eye of the beholder, and there’s no reason to assume that flagrantly uncommensical claims are any more likely to be accurate than those which seem intuitively right. In doing research, we just try to ascertain the evidence for any belief, commonsensical or not. The primacy effect might seem simply to rely on the old saw, “First impressions matter,” but it’s good to know that at least one commonplace is well supported. By contrast, the fundamental attribution error doesn’t on the face of it seem either common sense or not. It’s something that our folk psychology doesn’t guide us toward or away from. It’s actually a fresh discovery about some habits of our minds.

Moreover, a great deal of cognitivism flouts what some might take as common sense. Before Chomsky, most intellectuals thought that language was social through and through. He was able to show that certain features of it, including syntax, are likely to be part of our biological endowment. A lot of cognitive social psychology has been dedicated to showing how common-sense inferences are often illogical. These findings are now being popularized in books like Cordelia Fine’s A Mind of Its Own: How Your Brain Distorts and Deceives, and Thomas Kida’s Don’t Believe Everything You Think (from which my multiplication example comes). As for humanists’ suspicion of science, I address that unfounded fear in the introduction to Poetics of Cinema. If you prefer big-picture arguments about the issue, try Edward Slingerland’s new book.

Movies on the brain

The real debate on cognitivism in film studies has yet to take place. Meanwhile, the cognitivists keep plugging away. Over the years, the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image has attracted, broadly, three sorts of persons. All are represented in our upcoming conference.

*There are the film-trained academics like me, who have branched out into cognitive film theory to illuminate particular research projects. Our June gathering includes a great many such scholars, many of them pioneers in the cognitive perspective like the Andersons, Carroll, Grodal, Murray Smith, Carl Plantinga, Patrick Colm Hogan, et al.

*There are the psychologists, who are interested in explaining the psychological mechanisms of cinema. They tend to focus on particular phenomena, like eye movements, cutting, or other triggering processes, and they study the effects at various levels, from perceptual response to brain-scanning. Their great predecessor is Julian Hochberg, who studied cinema as a sort of stage show that displayed psychological processes with particular clarity. A magisterial collection of Hochberg’s work, In the Mind’s Eye, has recently been published. At our June gathering, an entire thread is largely devoted to psychological research into cinematic uptake. Our two plenary speakers, Uri Hasson of NYU and Dan Levin of Vanderbilt, also represent this tradition.

*Then there are the philosophers. Most are concerned with art and literature, and most incline to an Anglo-American form of conceptual analysis. These scholars come to SCSMI because they are of a cognitivist bent, or because they want to argue with cognitivist work, or because this is a useful forum for the sort of film-based questions they want to pursue. The June event includes many of the most prominent philosophers of film, and a panel session is devoted to critiques of Noël Carroll’s recent book The Philosophy of Motion Pictures.

Visit our schedule page, and you’ll get a sense of how varied this work is. Speakers are talking about everything from editing patterns to the effects of digital technology on filmic perception. The participants consider propaganda, melodrama, TV series, and videogames. There are presentations on the emotional dimensions of horror and on the ways that color works in particular movies. How do viewers who have never seen films before understand cutting? In what sense is film content fictional? How does the language of film theory affect the way we theorize? Is there something inherently filmic that sets cinema apart from other media?

Cognitivism isn’t a Big Theory of Everything; nobody has a clue about how these diverse research programs would fit together. The variety is what makes it fun. I think that anybody who wants to know more about movies would find something worthwhile at the Madison event, not least the opportunity to shmooz. And there’s The House on the Rock.

The evidence is mounting. Cognitivism is cool.

PS 17 April: This line of thought strikes a chord in Lee Marshall, who offers encouragement at Screen International here.

Things to like about looking

13 Lakes.

“What I like about looking is how many ways there are to see the same thing.”

Sadie Benning

DB here. Today no extended essay, just some jottings.

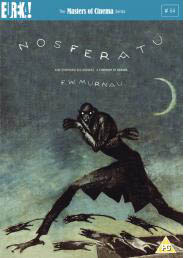

Some day I really must do an extended tribute to the Eureka/ Masters of Cinema DVD line. To call it the UK Criterion is partly right, given the painstaking transfers and the ample supplementary material. But Eureka ventures into some very fresh territory. A company that puts out the terminally peculiar Funeral Parade of Roses (Toshio Matsumoto, 1969) as well as a double-disc set of Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff and Gion Bayashi deserves points for audacity.

Some day I really must do an extended tribute to the Eureka/ Masters of Cinema DVD line. To call it the UK Criterion is partly right, given the painstaking transfers and the ample supplementary material. But Eureka ventures into some very fresh territory. A company that puts out the terminally peculiar Funeral Parade of Roses (Toshio Matsumoto, 1969) as well as a double-disc set of Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff and Gion Bayashi deserves points for audacity.

A recent batch of Eureka releases:

*Two cult animation items by René Laloux, Gandahar and Les maitres du temps. Fans of Fantastic Planet and the bande dessinée artist Moebius will snap these up, as much for the large booklets as for the discs.

*Then there’s Nosferatu. You say we’ve already got enough? Nope. First, we can never have too many of this, one of the greatest of silent films. Second, this version looks scarily definitive: a two-DVD set with the Murnau-Stifung restoration and the original score, plus a documentary, plus a book including some primary material along with essays by Enno Patalas, Gil Perez, Thomas Elsaesser, and Craig Keller.

*Sticking with Murnau (who directed, some say, in a white lab coat), Eureka offers a double-disc set of Tabu, also from the Murnau-Stiftung and with previously unseen scenes and title cards.

*Finally, there’s Peter Watkins’ Edvard Munch in its long version, with a booklet including a Watkins “self-interview.”

Unbelievably, many more great movies are on the way. Check the catalogue and preview lineup here.

Also from overseas, the Austrian Filmmuseum adds a new title to its Synema book series, alongside Alexander Horwath’s remarkable dossier on Sternberg’s Case of Lena Smith (discussed in an earlier entry here) and many other books on experimental cinema. It’s the first book devoted to James Benning.

Also from overseas, the Austrian Filmmuseum adds a new title to its Synema book series, alongside Alexander Horwath’s remarkable dossier on Sternberg’s Case of Lena Smith (discussed in an earlier entry here) and many other books on experimental cinema. It’s the first book devoted to James Benning.

I have a personal interest. I met Jim when I came to Madison in 1973. He was working on his MFA in film and art, and he was one of four teaching assistants assigned to me. There was Doug Gomery, already an impressive film historian, soon to go on to fame for his work on the US film industry. There was Brian Rose, one of the most alert cinephiles I ever met, and one of the funniest. There was Frank Scheide, already an expert on Chaplin, Keaton, and their peers. And there was Jim, a master mathematician (helpful for computing grade curves) and the only filmmaker in the bunch. Jim and Frank, both serene, had a calming influence on the rather hyper Rose, Gomery, and Bordwell. It was a great team, my Dirty 1/3 Dozen, and I remember our collective grading sessions fondly.

Jim had already made Time and a Half, but his most famous works, starting with 81/2 x 11 (1974), were yet to come. He left Madison and went on to teach filmmaking at several places, settling finally at Cal Arts. I kept in occasional touch with him and his work. He visited our Wisconsin Film Festival with his remarkable, politically charged Four Corners, El Valley Central, and Los. I’ve seen him more frequently in the last few years because turn up at the same film festivals—me as an observer, him showing gorgeous and provocative films like 13 Lakes, 10 Skies, and One Way Boogie Woogie/ 27 Years Later.

So the book, edited by Claudia Slanar and Barbara Pichler, is very welcome. It just arrived, so I haven’t had a chance to read it through, but I signal it to all those interested in a filmmaker who has been enthralling and surprising us for thirty-five years. Apart from a career chronology and a complete filmography, it features essays by Julie Ault, Sharon Lockhart, Volker Pantenburg, Dick Hebdige, Amanda Yates, Scott MacDonald, Allan Sekula, Michael Pisaro, Nils Plath, and of course Sadie Benning, a mean hand with Pixelvision. Lockhart supplies lustrous shots of some Wisconsin beer bottles in Jim’s collection.

Speaking of books, not beer, the Korean Film Council has just published a series of trim books on major directors, both classic and contemporary. Each volume includes a detailed filmography and a lengthy interview. Some volumes are through-written by a single author, others consist of analyses and appreciations by various hands, including major Korean critics and Asian cinema expert Chris Berry.

Speaking of books, not beer, the Korean Film Council has just published a series of trim books on major directors, both classic and contemporary. Each volume includes a detailed filmography and a lengthy interview. Some volumes are through-written by a single author, others consist of analyses and appreciations by various hands, including major Korean critics and Asian cinema expert Chris Berry.

The directors honored are Kim Dong-on, Im Kwon-taek, Lee Chang-dong, Kim Ki-young, Park Chan-wook, and Hong Sang-soo. This last volume, edited by Huh Moonyung, includes an homage by Claire Denis and a small essay by me, “Beyond Asian Minimalism: Hong Sang-soo’s Geometry Lesson.”

Books in the series may be ordered here.

Speaking, again, of books. . . The paper edition of Phillip Lopate‘s American Movie Critics: An Anthology from the Silents until Now (The Library of America) has just come out. I found reading the first edition addictive, like eating peanuts and M & Ms. Now we need a second volume including Frank Woods (a critic close to Griffith), Welford Beaton, and other less-known early writers.

In the meantime, the new edition has grown to include an essay on Fincher’s fine Zodiac by Nathan Lee and internet pieces from Stephanie Zacharek (Salon.com) and your obedient servant. I’ve never imagined an essay of mine in a collection that includes my teenage idols Mencken, Macdonald, Sontag, and Sarris, so this volume amounts to a swell early Christmas present. Thanks to Mr. Lopate and Geoffrey O’Brien for all their help.

Speaking, yet again, of books. . . A plug is in order for Scott Higgins’ meticulous, engagingly written Harnessing the Technicolor Rainbow: Color Design in the 1930s, just out from Texas. I sat on Scott’s dissertation committee, and I was impressed by his imaginative research methods (e.g., using Pantone swatches as an objective measure of color hues in movies) and his sensitive attention to the way the movies look. Nobody before Scott has analyzed color in film so carefully. Scott is also attentive to production practices, so filmmakers interested in the history of technology should find a lot to chew on here. Several pages of original Technicolor frames support Scott’s case in graceful detail. No beer bottles, however.

More books from Wisconsin scholars: The above-mentioned Doug Gomery has a new book due out early next year, A History of Broadcasting in the United States. Lea Jacobs’ The Decline of Sentiment: American Film in the 1920s should follow soon. I’ve read the latter already, but both are without doubt worthy of your attention. If you like your American film history at once informationally solid and intellectually daring, you will like these items. Neither Doug nor Lea is a fan of conventional wisdom.

Finally, for fans of Hong Kong cinema: Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai‘s Mad Detective (I filed a note on it from Vancouver) has been a hit in Hong Kong, beating Beowulf. An analog Lau Ching-wan can thrash a digital Ray Winstone any day of the week. Milkyway Image’s boundlessly energetic Shan Ding has set up a Facebook page as a place to chat about movies and, one hopes, to keep us apprised of developments in Mr T’s upcoming remake of Melville’s Cercle Rouge.

Mad Detective.

PS: Just learned about an informative interview with Jim Benning here, with more ravishing shots from 13 Lakes. This entry also includes several other links to web discussions of Jim’s films.

Bob Shaye is the most reckless man in Hollywood. True or false?

|

=

? |

|

Kristin here–

As a writer and even more as a reader, I am frequently baffled when an author with a fascinating, innately dramatic story to tell feels it necessary to ratchet up its appeal with hype. I’m an amateur Egyptologist and sometimes watch the documentaries made by the Discovery Channel, National Geographic, and the other educational TV outlets. Now, a great many people are fascinated by ancient Egypt in a way that they aren’t by virtually any other period of history. So many events and aspects of that society are at least intriguing, at most amazing. The building of the pyramids, the process of mummification, the distinctive artworks–all of these could sustain straightforward presentation.

Instead, the filmmakers responsible for these documentaries feel it necessary to beef up their ancient subject matter. The factual scenes are interspersed with shots of actors dressed in pharaonic costumes driving chariots across the desert, accompanied by overblown music. Archaeologists hover outside supposedly sealed tombs or chambers, speculating breathlessly as to what might be inside. Artificial mysteries are overly prolonged, when all along the filmmakers know the answers. Since the channels producing these documentaries are often subsidizing the archaeologists’ work, there is pressure for these scholars to make more glorious claims for their findings than the facts warrant.

Similarly, film history contains innumerable stories that are both educational and entertaining, if told in a straightforward, factual way. Any major film’s making yields many facts and anecdotes that are in themselves interesting. Yet here, too, many authors—especially journalistic ones—seem to feel the need to inject an artificial drama into their tale. This can be harmless, but if an author tries too hard, the facts get obscured or distorted.

In the case of big box-office successes, journalists tend to find one over-arching claim that can seem to explain a film while giving it an extra dose of drama. There was one such concerning The Lord of the Rings that I encountered over and over when I was researching The Frodo Franchise. Despite all the twists and turns that the progress of the film took—the unlikely move from Miramax to New Line, the last-minute casting of Viggo Mortensen, the struggles to reach remote filming locations, the third part’s winning eleven Oscars, and many, many more—somehow there wasn’t enough drama. In this case, the big claim was that Rings was an immense gamble on the part of New Line’s founder and co-president, Bob Shaye. Some have believed, both before and after the trilogy’s release, that its failure would have meant the end of New Line. The independent firm would have been absorbed into parent company Time Warner, and Shaye would have been stripped of power.

My book was written after all three parts of Rings had gone into the box-office record books. New Line had grown considerably and was in no danger. During my research I questioned people involved in the film’s production and people in the industry who would have reason to know whether New Line really stood in such a precarious position in 2001. Opinions were divided, but few thought that New Line would have disappeared had the trilogy flopped. A gamble, yes, but ones where the stakes were lower and the odds more in New Line’s favor than most accounts would suggest.

Boffo! by Bart

I can see why journalists, even in trade papers like Variety and Hollywood Reporter, would find it convenient to fall back on this gamble motif when writing copy on a short deadline. Now, however, the familiar claim has reappeared in Peter Bart’s book, Boffo! How I Learned to Love the Blockbuster and Fear the Bomb (Miramax Books, 2006). Bart deals with extremely successful films, plays, and TV shows. The Lord of the Rings occupies one chapter.

When the first anniversary of this blog rolled around, David wrote about some of our goals as film scholars and bloggers. One of them was this:

We’ve tried to deflate some clichés of mainstream film journalism. Writers of feature articles are pressed to hit deadlines and fill column inches, so they sometimes reiterate ideas that don’t rest on much evidence. Again and again we hear that sequels are crowding out quality films, action movies are terrible, people are no longer going to the movies, the industry is falling on hard times, audiences want escape, New Media are killing traditional media, indie films are worthwhile because they’re edgy, some day all movies will be available on the Internet, and so on. Too many writers fall back on received wisdom. If the coverage of film in the popular press is ever to be as solid as, say, science journalism or even the best arts journalism, writers have to be pushed to think more originally and skeptically.

The same goes, only more so, for books written in the same spirit. Journalistic writing is at least somewhat ephemeral. Books, though, stay on the shelf, and they automatically command a certain respect.

As I said, the story of Rings, told straightforwardly, is immensely dramatic. What better story could a film historian possibly have to tell? All through the researching and writing processes, I tried simply to discover, convey, and interpret that story without adding hype.

Bart adds the hype. His chapter on Rings not only revives the old gamble angle but goes further, asking, “What was the bravest gamble in the history of filmmaking?” Arguably, he answers, the trilogy.

Why? First, it was risky to make all three films at once. Granted, though as Bart acknowledges, there were enormous cost benefits from doing so. Second, the initial budget of $130 million, according to Bart, ballooned to $330 million. Now the problems start. $130 million was the budget when Rings was still a two-part project at Miramax. Taking over the film, New Line provisionally kept the existing budget until a three-part script could be written and the costs estimated on a firm basis. The estimate then grew to $270 million, which we should count as the budget the studio was really working from. The success of Fellowship of the Ring led New Line to agree to requests for more money in making the second and third parts. Costs did not run wildly over expectations.

What else was so risky? According to Bart, New Line earmarked “virtually its entire production budget to support the effort.” If Bart has evidence for this claim, he doesn’t share it. Without access to New Line’s accounts, we can’t be absolutely certain. Still, there is considerable evidence to the contrary. New Line executives have consistently pointed out that, spread over the three years of the trilogy’s release, their own annual investment was relatively small. Co-president Michael Lynne has said in a number of interviews that most of the budget was covered by other companies. In a recent issue of Screen International, he declared, “The foreign distribution rights alone were responsible for close to 70%” (Mike Goodridge, “The Ringleaders,” October 26, 2007, p. 23).

There were 26 foreign distributors, several of whom paid visits to the Wellington facilities during the production. I have talked with some of the filmmakers who took those distributors on tours. My book includes a case study of the Danish distribution company based on a two-hour interview with one of its executives (Chapter 9). During the years of the trilogy’s release, the trade journals, including Variety, ran stories about these distributors. The 70% figure, by the way, doesn’t count the merchandising licenses, many of which had been sold in 2000, helping to finance the trilogy. New Line was gambling, but largely with other people’s money.

Further, Bart declares, Shaye’s decision was a gamble because the narrative of Tolkien’s novel was so complex that it had previously scared off Spielberg, Kubrick, Harvey Weinstein, Saul Zaentz, and the Beatles (p. 51). Again, my research points in other directions. I have never heard that Spielberg was in the running to make Rings at any point. Stanley Kubrick was approached by Apple, the Beatles’ company, back in the late 1960s, when the Fab Four were interested in starring in a film adaptation of Rings. I suspect that it wasn’t the novel’s complexity that made Kubrick decline. (The Beatles got interested in transcendental meditation and went off to the Far East.) Bart says that Saul Zaentz “did little” with the production rights once he acquired them (p. 54). But in 1978 Zaentz produced an unsuccessful animated version of the first half of the book and decided not to make the sequel. Harvey Weinstein very much wanted to keep the Rings project at Miramax, but he was forced by parent company Disney’s head, Michael Eisner, to scale it back to a single two-hour feature. Peter Jackson refused to accept that condition and took the project to New Line.

Finally, Bart points out that Jackson was then a little-known director with not a hit to his name. True, but as I point out in my book, for the short time the Rings was in turnaround from Miramax, Jackson alone had the power to bring the project to New Line. Shaye undoubtedly wanted the rights to Rings, believing that it would make a successful franchise. Jackson came along with those rights.

Late in the chapter, Bart offers another reason why taking on the trilogy flew in the face of conventional wisdom: New Zealand is very remote from Hollywood (p. 63). Perhaps the distance caused some troubles, but it saved a huge amount of money—enough to make the difference between the trilogy getting made or not. In The Frodo Franchise I calculate (based on costs for a comparable effects-heavy epic, Titanic) that Rings might have cost roughly $544 million if made in North America (or $700 million if one includes the 120 minutes of extended-edition footage). Jackson undertook a similar estimate based on Pearl Harbor and came up with a figure of $180 million for Fellowship—and three times that is $540 million. The difference between those figures and $330 million pays for a lot of airline tickets.

Shaye’s “Gambler” Reputation

One of Bart’s conclusions is, “For those who, like Bob Shaye and Michael Lynne, believed that big returns emanate from big risks, Lord of the Rings provided a unique and generous validation” (pp. 63-64). This is peculiar indeed. I don’t think either Shaye or Lynne would agree with that assessment of their approach to production. Shaye was known for running a tight fiscal ship at New Line. His company became famous for turning miniscule investments into massive hits and franchises: most notably, Nightmare on Elm Street and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Shaye has a sign on his office wall that reads “Prudent Aggression.” That, I would say, is the attitude with which he approached the Rings decision.

Neither Shaye nor Lynne has generally encouraged the notion of the Rings deal as a gamble. (See my first chapter for more on this.) In the Screen International piece cited above, the interviewer asks that very question: “Do you agree that the trilogy was the riskiest venture that any film company has tried to date?” Shaye responds, “We had hedged somewhere between 70%-80% of our investment.” Lynne adds, “If it had broken even, nobody would have been happy. The company wouldn’t have gone out of business, but it definitely would have been a problematic issue for people who had invested with us, and for Time Warner itself.” (The investors were the international distributors who had pre-bought the entire trilogy.)

In an interview on The Charlie Rose Show earlier this year, Lynne said something similar: “The problem was, if the first film didn’t work, the next two were certainly not going to work, that these films would at best break even. Well, no one at Time Warner was going to be thrilled that we invested the three hundred million dollars and just got our money back! So although we weren’t betting the ranch, we certainly were betting our credibility.”

The gambler image no doubt redounds to Shaye’s advantage in some ways. He was the only one in Hollywood willing to take on the immense project when Jackson was shopping it around the studios. He was famously the one who told the director that he should make three films, not two. Despite occasional tensions between the filmmakers and studio executives, Shaye and Lynne not only stuck with the project but acceded to requests for tens of millions in additional spending. Shaye’s resulting image is that of a savvy maverick who outguessed the heads of the other studios.

On the other hand, it can’t be to his advantage to be perceived as reckless. If people think that Rings really was the biggest gamble in the history of Hollywood and that Shaye risked $330 million of his own firm’s money, blithely taking a chance on a director of splatter films, then he risks coming across as irresponsible. Hence, I suspect, his and Lynne’s care in informing interviewers that they had found investors and licensees to cover the bulk of the trilogy’s budget. Shaye has also pointed out that the trilogy stretched over three fiscal years, as I mentioned, making the annual investment in Jackson’s film modest relative to its epic qualities.

Of course the trilogy was a gamble. As Shaye said in the Charlie Rose interview, “But every film commitment is a gamble to some extent.” The size of this particular gamble, however, has been considerably exaggerated. Shaye and Lynne knew what they were doing. They saw the savings to be had by filming in New Zealand and by committing the cast members up front to all three films—hence obviating the possibility of ballooning salary demands if the first part was successful.

I’m sure there were many moments of worry and doubt in the years between New Line’s official announcement of the project on August 24, 1998 and the triumphant preview screenings at Cannes in May, 2001—when journalists and foreign distributors alike realized that the studio had, as Harvey Weinstein put it at the time, “another ‘Star Wars’ on their hands.” Still, I would place a small bet that during those same years the disastrous Town & Country (filmed in 1998 and released in late April, 2001) was giving Shaye and Lynne at least as much anxiety. That long-delayed film cost $90 million, with a publicity budget of $15 million. It grossed $10 million worldwide.

Above all, Shaye saw the likelihood of the trilogy’s success in a way that no one else did. My favorite statement of his was quoted in a Time article in late 2002, shortly before the release of The Two Towers. Asked why he had wanted three films instead of two, Shaye replied: “It was so wonderfully presold. It was like Superman or Batman.” Juxtaposing Tolkien’s novel with those comic-book superheroes might bring a smile—but he was right. If we can just set aside the persistent notion that Rings was a huge gamble, we can see that Shaye was remarkable for his foresight, not his recklessness.